Abstract

Integrated photonic devices made of silicon nitride, which can be integrated with silicon-on-insulator and III-V platforms, are expected to drive the expansion of silicon photonics technology. However, the relatively low refractive index contrast of silicon nitride is often considered a limitation for creating compact and efficient devices. Here, we present three freeform silicon nitride devices—a coarse wavelength-division multiplexer, a five-mode mode division multiplexer, and a polarization beam splitter—while systematically benchmarking both the design capability and the fabrication repeatability and robustness of inverse-designed components. We demonstrate up to a 1200× reduction in footprint while maintaining relatively large minimum feature sizes of up to 160 nm, showing that inverse-designed silicon nitride devices can be as compact as their silicon counterparts. These results enable high-density integration in silicon nitride photonics and pave the way for multidimensional data transmission and quantum applications, as the inverse design technique can be applied to different silicon nitride thicknesses and is potentially extendable to other low- and mid-index contrast platforms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Silicon nitride (SiN) has enabled a wide range of applications, including sensing1,2,3, optical communications4, interconnects5,6, spectroscopy7,8, light detection and ranging9,10, and quantum information processing11,12, due to its broad transparency window and accessibility. Its impact also results from the ultra-low waveguide propagation losses it can provide13, with losses below 0.1 dB m−1, facilitating the management of high optical power and enabling nonlinear applications such as optical frequency comb generation14,15. The small thermo-optic coefficient of SiN and silicon dioxide (SiO2) results in a low wavelength dependence on temperature16. This property benefits passive devices but presents challenges for tunable components. Additionally, the relatively low refractive index contrast between SiN and SiO2 minimizes phase errors in devices such as interferometers, enhancing robustness against fabrication imperfections17. However, this advantage comes at the expense of larger device footprints, which limits the number of components that can be integrated per chip. For instance, in a platform where the SiN is 400 nm thick, a 850 nm wide waveguide should be routed with a minimum bend radius of 50 μm to achieve negligible losses18.

Silicon photonics is transitioning from the era of medium-scale integration (MSI; 10-500 components) to that of large-scale integration (LSI; 500–10000 components), driven in part by the demands of photonic quantum computing19. The rise of co-packaged optics (CPO) demands LSI photonics—and eventually very-large-scale integration (VLSI) chips with more than 10,000 components—offering high bandwidth and connectivity20, alongside high-performance electronic chips within the same package. This level of integration is essential for enabling the next generation of high-performance computing systems, including those driving artificial intelligence21. For SiN to play a key role in co-packaged optics (CPO) and VLSI photonic circuits, substantial reductions in component sizes, waveguide routing bends, and input/output coupler dimensions are required.

Spatial and mode multiplexers, along with polarization management devices, are essential components in many applications22,23,24, especially in optical communications25. Recently, various low-loss multiplexers and polarization splitters implemented on a silicon nitride platform have been reported26,27,28,29,30,31. However, most demonstrations require a substantial footprint, and attempts to miniaturize these devices often introduce additional fabrication complexity, such as deep etch steps or the integration of additional material layers32,33. SiN multiplexers can be implemented using gratings34,35, cascaded Mach-Zehnder interferometers (MZI)36, ring resonators37, and directional couplers26. Gao et al. demonstrated a coarse wavelength division multiplexer (CWDM) for the O-band with a footprint of 1 × 0.6 mm2, achieving a minimum loss of 1.55 dB38. More recently, a three-mode mode division multiplexer (MDM) with a length of over 1.4 mm operating at visible wavelengths was demonstrated, achieving an insertion loss of 3.5 dB for the highest-order mode23. Kudalippalliyalil et al. presented a compact polarization beam splitter (PBS) measuring 80 × 13 μm2 on a 400 nm thick SiN platform, achieving an efficiency of up to −0.7 dB and a crosstalk level below −18.0 dB24.

In this work, we demonstrate the potential of the inverse design technique to improve component integration density on photonic platforms with moderate refractive index contrast by presenting three ultra-compact freeform devices—a four-channel CWDM, a five-mode MDM, and a PBS—fabricated on a single-etch SiN platform. The four-channel CWDM, with a footprint of 24 × 24 μm2, achieves a maximum measured efficiency of −0.8 dB at the central wavelength across all channels. The five-mode MDM, with a compact 16 μm length, achieves an average maximum efficiency of −1.0 dB for the TE00 mode and of −2.3 dB for the TE04 mode, with crosstalk below −11.0 dB. The polarization beam splitter, measuring 24 × 12 μm2, exhibits an average efficiency of −0.8 dB for the TE mode and of −0.9 dB for the TM mode across the entire C-band, with crosstalk as low as −18.0 dB. These devices feature the smallest reported footprints among similar demonstrated devices, significantly enhancing integration density while maintaining high performance.

Results

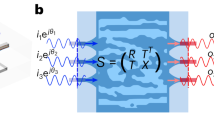

All the proposed devices were implemented using a fully etched SiN core (400 nm thick) surrounded by SiO2. The refractive indices used for the design were 1.997 for SiN and 1.441 for SiO2 at 1550 nm. For the inverse design process, we employed the Python-based wrapper LumOpt, which enables density-based topology optimization while incorporating fabrication constraints such as a minimum feature size and a smoothing filter with a radius of up to 160 nm. To further improve the performance of the four-channel CWDM, a deep machine learning model from PreFab Photonics39, optimized for the SiN fabrication process offered by Applied Nanotools (ANT), was used to refine the layout and anticipate fabrication deviations. The devices were fabricated using electron-beam lithography (EBL) and characterized with a wafer-level automated test station (see “Methods”).

Coarse wavelength division multiplexer

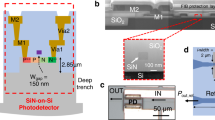

The compact CWDM was designed using the fundamental TE mode of the input waveguide as the input mode for the inverse design process, while the fundamental TE modes of the four output waveguides were used as the output modes. The waveguide width was set to 850 nm to ensure single-mode operation. The target central wavelengths were 1530 nm, 1550 nm, 1570 nm, and 1590 nm, and the optimization was carried out using five wavelengths within a 10 nm bandwidth around each central wavelength. Figure 1 presents the original device design, a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the fabricated original device with a footprint of 24 × 24 μm2, and the simulated electromagnetic energy density at the central wavelength of each channel. At 1530 nm, the light undergoes a directional change before propagating through the upper channel. In contrast, for the other channels, the light follows a relatively smooth path towards their respective output (see Supplementary Movie).

a Device design, where the black areas represent silicon nitride and the white ones represent silicon dioxide. b SEM image of the fabricated device without layout corrections, with a total footprint of 24 × 24 μm2. c Simulated electromagnetic energy density at the central operating wavelength of each channel.

The simulated and measured transmission results for the original and refined designs are shown in Fig. 2. Simulated transmission and crosstalk were −0.9 dB and −18.4 dB at 1530 nm, −0.7 dB and − 17.4 dB at 1550 nm, −0.5 dB and −14.7 dB at 1570 nm, and −0.7 dB and −20.1 dB at 1590 nm. Simulations also indicated that back-reflection into the input waveguide remained consistently below −16.9 dB at the central wavelengths. Measurements from three identically fabricated devices without layout refinement, shown in Fig. 2b, demonstrated highly repeatable performance. The average measured transmission was −1.7 dB at 1511.3 nm, −1.3 dB at 1531.3 nm, −1.0 dB at 1551.3 nm, and −1.0 dB at 1571.3 nm, with crosstalk remaining below −11.6 dB at these wavelengths. The discrepancies between simulated and measured results are mainly attributed to over-etching during fabrication (see Supplementary Fig. 4).

a Simulated transmission obtained using a 3D finite-difference time-domain algorithm. Measured transmission from fabricated devices: (b) original design and (c) layout corrected design. Solid lines represent average transmission, and gray shaded areas show the range between minimum and maximum values obtained during measurements.

Figure 2 c shows the results for two identically fabricated devices with layout refinement. The deep machine learning model adds silicon nitride where material loss is predicted and removes it where excess SiN is expected after fabrication, thereby bringing the fabricated device response closer to the simulated design (see Supplementary Note 3). The average measured transmission was −1.2 dB at 1517 nm, −1.2 dB at 1537 nm, −1.5 dB at 1557 nm, and −0.8 dB at 1577 nm, with measured crosstalk values of −19.4 dB, −20.2 dB, −14.7 dB, and −25.2 dB, respectively. The refined design showed slight improvements in transmission efficiency for channels 1, 2, and 4, and a small drop for channel 3. The most notable enhancements were the correction of the wavelength shifts and a reduction in crosstalk. The wavelength shifts decreased by more than 5 nm for all central wavelengths, whereas crosstalk improved by more than 5 dB for channel 1, with improvements across all channels.

Mode division multiplexer

A compact five-mode MDM multiplexer was optimized using the fundamental TE mode of five 850 nm-wide input waveguides, spaced 1.2 μm apart, as the input modes, while the first five TE modes of a 4 μm-wide output waveguide served as the output modes in the inverse design process. Broadband optimization, spanning the entire C- and L-bands, was performed over a rectangular design region of 16 × 7 μm2, with a minimum feature size and a smoothing filter radius of 120 nm applied during the optimization process. Figure 3 presents the final device design, including the routing network, a SEM image of the fabricated structure (with an inset showing the region near the input waveguides), and the simulated electromagnetic energy density at 1550 nm for each mode. The five-mode MDM multiplexer routes the fundamental TE00 mode of the input single-mode waveguides to the TE00 (channel 2), TE01 (channel 3), TE02 (channel 4), TE03 (channel 1), and TE04 (channel 5) modes of the output multimode waveguide. Additionally, 16 μm radius freeform bends were used to route channels 1 and 518, minimizing crosstalk. Furthermore, the five-mode MDM can be used to implement an micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) inter-chip modal switch40 if instead of using five fixed input waveguides only one input, mounted on a MEMS actuator, is used to select which mode is excited.

a Device design and routing network, where the black areas represent silicon nitride and the white ones represent silicon dioxide. b SEM image of the fabricated device with a total footprint of 16 × 7 μm2, including an inset showing the input waveguides. c Simulated electromagnetic energy density for each channel at 1550 nm.

The simulated and measured transmission results are shown in Fig. 4. The average simulated transmission efficiency across the entire C-band is −0.9 dB for TE00, −0.9 dB for TE01, −1.2 dB for TE02, −1.3 dB for TE03, and −1.3 dB for the TE04 mode, respectively. The 3-dB bandwidth exceeds 120 nm, and the average crosstalk across these wavelengths remains below −12.3 dB for all channels. The measured average efficiency in the C-band is −1.0 dB for TE00, −1.1 dB for TE01, −1.3 dB for TE02, −1.9 dB for TE03, and −2.3 dB for TE04, with crosstalk values of −11.0 dB, −10.6 dB, −13.7 dB, −11.1 dB, and − 16.1 dB, respectively. Furthermore, the transmission spectra is flat across the entire C-band. The five-mode MDM multiplexer, including its routing network, maintains efficiencies comparable to those of its silicon counterparts while preserving its ultra-compact footprint41. Modal crosstalk can be reduced by increasing the channel spacing in the five-mode MDM multiplexer; however, this would also increase the switching time when used as part of a MEMS switch.

Polarization beam splitter

Figure 5 presents the ultra-compact PBS design, an SEM image of the fabricated device, and the simulated energy density at 1550 nm for both TE and TM polarizations. The PBS was designed using the fundamental TE and TM modes of the input waveguide as input modes for the inverse design process, with the TE and TM modes directed to output channels 1 and 2, respectively. The spacing between the output waveguides was set to 4.925 μm, and both the input and output waveguide widths were set to 850 nm. The optimization was performed within a 24 × 12 μm2 region, targeting broadband operation spanning from 1520 nm to 1630 nm, and incorporating a minimum feature size and a smoothing filter with a radius of 160 nm.

The simulated and measured transmission spectra of the compact PBS device for channels 1 and 2, corresponding to TE and TM polarizations, respectively, are shown in Fig. 6. The average simulated TE transmission efficiency to channel 1 is −0.3 dB, while the undesired TM transmission to the same channel averages −20.1 dB across the C-band. Similarly, the average simulated TM transmission efficiency to channel 2 is − 0.3 dB, with the undesired TE transmission averaging −25.8 dB. These values indicate a simulated polarization extinction ratio (PER) exceeding 19.8 dB. The measured average TE transmission efficiency to channel 1 is −0.8 dB, while the average TM transmission efficiency to channel 2 is −0.9 dB. The undesired TM transmission to channel 1 and the undesired TE transmission to channel 2 are −15.5 dB and −15.3 dB, respectively. Measurements were limited to the C-band due to constraints imposed by the TM grating coupler (see “Methods”). The reduction of the experimental PER to ~14.5 dB is attributed to fabrication variations, including over and under etching (see Supplementary Fig. 6).

Although it may be desirable, most inverse-designed photonic structures do not exhibit periodic, regular, or modular patterns and therefore cannot be easily interpreted or modeled using traditional physical models. However, the devices presented in this work—including the four-channel CWDM, the five-mode MDM, and the PBS—can be understood as systems that precisely engineer light-matter interactions at the subwavelength scale. Through their non-intuitive, freeform geometries, these devices spatially tailor the effective refractive index to produce highly specific patterns of constructive and destructive interferences, each optimized for particular wavelengths, spatial modes, or polarizations. Thus, the dispersion required to separate wavelengths, polarizations or to manipulate a wavefront to convert it into a different spatial mode is achieved by engineering the refractive index of the subwavelength pixels. Therefore, this approach provides capabilities that go far beyond conventional photonic components.

Discussion

The inverse design technique has been increasingly utilized in both academia and industry to enhance component density on silicon-on-insulator (SOI) platforms. Many passive and active devices have been successfully miniaturized using this technique on platforms with high refractive index contrast42. However, inverse design has been less explored for platforms with medium to low index contrast, such as silicon nitride, with only a few exceptions, including reflectors43, TM polarizers44, mode converters45, and beam splitters46. This is primarily due to the significantly higher computational effort required when working with large optimization regions.

It is important for inverse-designed devices to demonstrate good fabrication repeatability and to remain robust against fabrication variations while maintaining high performance. Our freeform four-channel 24 × 24 μm2 SiN CWDM achieves high transmission efficiency, ranging from −0.8 dB to −1.5 dB at the central wavelength of each channel. These results are comparable to those of a freeform four-channel 14 × 16 μm2 silicon CWDM device, which demonstrates efficiency levels between −2.0 dB and −3.3 dB47. Additionally, the unique five-mode freeform SiN MDM device has a remarkably small footprint of 16 × 7 μm2, compared to SiN phase-matching multiplexers, which typically occupy areas greater than 1 mm2, achieving transmission efficiencies from − 1.0 dB to − 2.3 dB. This footprint is comparable to the only freeform five-mode MDM in silicon presented so far in the literature, which has a footprint of 6 × 10 μm2 and achieves a transmission efficiency ranging from −2.4 dB to −3.9 dB41. Our inverse-designed SiN multiplexers have a compact footprint and achieve performance on par with, or better than, their silicon counterparts, despite the lower index contrast. While our CWDM design demonstrates high efficiency and good fabrication repeatability, the central wavelengths shifted toward lower values even after applying a layout refinement, primarily due to over-etching during fabrication. Fabrication variations also affect crosstalk more than transmission efficiency in broadband devices—including the MDM and PBS—with the effect particularly pronounced in the PBS. These issues can be mitigated using machine learning-based correction models48, which continue to improve, as demonstrated with the CWDM device, ensuring that miniaturization does not compromise performance.

In summary, we demonstrated experimentally three ultra-compact freeform silicon nitride devices—a four-channel CWDM, a five-mode MDM, and a PBS—using the inverse design technique. These devices achieve performance levels that have not been demonstrated before in such small SiN structures. For instance, the CWDM device demonstrates a size reduction of more than 1200× compared to traditional cascaded MZI silicon nitride designs38. Our results show that applying inverse design techniques to the silicon nitride platform can enable the development of highly compact devices while preserving superior passive performance, paving the way for large-scale integration.

Methods

Optimization

To design the devices, we use the Python-based wrapper LumOpt, which supports continuous density-based topology optimization and employs the Ansys Lumerical 3D finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) algorithm to solve the direct and adjoint problems for sensitivity analysis. The optimization is driven by gradient-based algorithms from SciPy.

The topology optimization workflow begins with an initialization step, in which the optimization volume and the initial core and cladding refractive indices are defined. LumOpt uses a rectilinear optimization grid that is fully aligned with the 3D FDTD simulation grid used for both the direct and adjoint solves. For each device, we evaluated three initial conditions: the design region was uniformly initialized with either silicon nitride, silicon dioxide, or a refractive index equal to the average of the two. For the CWDM and PBS devices, the best results were obtained with the average-index initialization, whereas for the MDM device, initializing with silicon nitride yielded superior performance.

The optimization consists of three stages. In the first phase (Greyscale optimization), the material distribution varies continuously between the core and cladding indices. In the second phase (Binarization), the design is forced to take on discrete values corresponding to either the core or cladding material. A convolution filter and a projection function are employed to smooth the design region. Specifically, a circular top-hat kernel with a radius of 120 or 160 nm is used to eliminate small holes, sharp corners, and other non-manufacturable features. Simultaneously, an approximation of the Heaviside function transforms the linear mapping of the design parameters into a near step-like function, controlled by the steepness parameter β. As β → ∞, the geometry becomes increasingly binary. This step may introduce sharp peaks in the figure of merit, which are mitigated through additional optimization iterations to stabilize the design. The final phase (Design for the manufacturing (DFM)) introduces explicit minimum length-scale geometric constraints to eliminate residual small features and ensure fabrication feasibility. An overview of the topology optimization process is provided in Supplementary Note 4.

The optimization process was performed on a single computer equipped with an Intel Core i9-12900 processor and 64 GB of RAM. The computational time per iteration varied for each device: for the CWDM, it ranged from 50 min to ~5 h; for the MDM, from 20 min to about 5.5 h; and for the PBS, from 15 min to ~2.5 h. The final optimization phase was typically the most time-consuming. Supplementary Figs. 1, 2, and 3 illustrate the complete optimization trajectory for each device, along with the material index distribution at representative iterations of each optimization stage.

Fabrication

The photonic integration platform used in this work is based on silicon nitride and consists of a 400 nm SiN core layer, a 4.5 μm buried oxide layer, a 3 μm top silicon dioxide cladding, and a 525 μm-thick silicon substrate. All devices were fabricated through multi-project wafer runs at ANT.

An hydrogen silsesquioxane (HSQ) hard mask was spin-coated onto the SiN layer, and the device patterns were written using 100 keV EBL. The exposed HSQ resist was developed using a tetramethylammonium hydroxide-based developer. Pattern transfer into the SiN layer was carried out via a single-step anisotropic reactive ion etching process using a CHF3/O2 chemistry. After etching, a 3 μm top cladding of silicon dioxide was deposited using plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition49. Although the EBL process enables feature sizes as small as 120 nm, a minimum feature size and spacing of 160 nm was enforced for the CWDM and PBS devices to improve fabrication robustness and ensure compatibility with large-scale complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) foundries using 193 nm deep ultraviolet lithography.

The fabricated waveguides exhibit an average sidewall angle of ~83. 5°, with measured propagation losses of about 1 dB cm−1 for the TE mode at 1550 nm under single-mode operation.

Measurement

The devices were characterized using an EXFO OPAL-EC wafer-level automated test station, which features a motorized high-resolution 4-axis motion system with thermal control, where the chips were placed during measurements. The station also includes a 30° polarization-maintaining 12-fiber array mounted on a hexapod, connected via polarization-maintaining fibers to an EXFO T100S-HP tunable laser and a CTP10 passive optical component testing platform for transmission efficiency measurements. For TM measurements, a polarization rotating fiber was inserted between the laser and the fiber array. A Z-profile scan was conducted on the chip surface to maintain a consistent coupling distance of ~20 μm throughout all TE measurements. To ensure accurate and repeatable device efficiency measurements, surface coupling optimization was performed using the same automated alignment sequence for all devices. Transmission measurements were then normalized against reference surface grating couplers connected in a loopback adjacent to each device, eliminating variations due to coupling and waveguide propagation losses and enabling a direct evaluation of device performance. In addition, to characterize the inverse-designed MDM, we used an auxiliary adiabatic directional coupler MDM placed back-to-back with the device under test. The two MDMs were connected via a 38 μm-long, 4 μm-wide multimode waveguide. To normalize the measurements and isolate the performance of the inverse-designed MDM, we fabricated a nearby reference structure consisting of two identical directional coupler MDMs connected by a multimode waveguide with the same length. By comparing the transmission spectra of the inverse-designed MDM structure and the reference structure, we extracted the loss and crosstalk attributable to the inverse-designed MDM alone. It is worth noting that the directional coupler MDM has a length of ~800 μm, highlighting the substantial footprint reduction achieved by the inverse-designed MDM.

The grating coupler used for the TE measurements was a non-uniform design optimized using SPINS-B50. With a minimum feature size of 400 nm, it achieved an experimental minimum coupling loss of 12.1 dB through a single-pitch loopback configuration. The coupling angle for TE measurements was maintained at 30°, aligning with the fiber array. For TM measurements, a regular grating with a period of 1.88 μm and a fill factor of 0.5 was used, resulting in an experimental minimum coupling loss of 19.7 dB. A 26° coupling angle was employed, increasing the coupling distance to over 100 μm. This distance was maintained consistently across all TM measurements to ensure repeatability. The bandwidth of the TM grating coupler was limited to the C-band, as TE crosstalk became significant in the L-band.

Data availability

All the data supporting this study are available in the article and Supplementary Information. Additional data related to this article are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Harame, D. L., Bousse, L. J., Shott, J. D. & Meindl, J. D. Ion-sensing devices with silicon nitride and borosilicate glass insulators. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 34, 1700–1707 (1987).

Woias, P., Meixner, L. & Fröstl, P. Slow pH response effects of silicon nitride ISFET sensors. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 48, 501–504 (1998).

Antonacci, G. et al. Ultra-sensitive refractive index gas sensor with functionalized silicon nitride photonic circuits. APL Photonics 5, 081301 (2020).

Butler, D. et al. Demonstration of intra-data center link based on 1 × 4 multicore fiber (mcf) edge-coupled to silicon photonics. 2021 european conference on optical communication (ECOC). 1–4 (2021).

He, A. et al. Broadband and low-loss metamaterial silicon nitride edge coupler. 2024 optical fiber communications conference and exhibition (OFC). 1–3 (2024).

Brunetti, G., Heuvink, R., Schreuder, E., Armenise, M. & Ciminelli, C. Silicon nitride spot size converter with very low-loss over the C-band. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 35, 1215–1218 (2023).

Dhakal, A. et al. Evanescent excitation and collection of spontaneous Raman spectra using silicon nitride nanophotonic waveguides. Opt. Lett. 39, 4025–4028 (2014).

Zhao, H., Clemmen, S., Raza, A. & Baets, R. Stimulated Raman spectroscopy of analytes evanescently probed by a silicon nitride photonic integrated waveguide. Opt. Lett. 43, 1403–1406 (2018).

Xu, W. et al. Fully integrated solid-state LiDAR transmitter on a multi-layer silicon-nitride-on-silicon photonic platform. J. Lightwave Technol. 41, 832–840 (2022).

Lukashchuk, A. et al. Photonic-electronic integrated circuit-based coherent LiDAR engine. Nat. Commun. 15, 3134 (2024).

Taballione, C. et al. 8×8 reconfigurable quantum photonic processor based on silicon nitride waveguides. Opt. express 27, 26842–26857 (2019).

Prokhodtsov, A. et al. Silicon nitride Mach-Zehnder interferometer for on-chip quantum random number generation. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1695, 012118.

Blumenthal, D. J., Heideman, R., Geuzebroek, D., Leinse, A. & Roeloffzen, C. Silicon nitride in silicon photonics. Proc. IEEE 106, 2209–2231 (2018).

Kim, S. et al. Dispersion engineering and frequency comb generation in thin silicon nitride concentric microresonators. Nat. Commun. 8, 372 (2017).

Guo, H. et al. Mid-infrared frequency comb via coherent dispersive wave generation in silicon nitride nanophotonic waveguides. Nat. Photonics 12, 330–335 (2018).

Xiang, C., Jin, W. & Bowers, J. E. Silicon nitride passive and active photonic integrated circuits: trends and prospects. Photonics Res. 10, A82–A96 (2022).

Baets, R. et al. Silicon photonics: silicon nitride versus silicon-on-insulator. Optical Fiber Commun. Conf. Th3J–1 (2016).

Ruiz, J. L. P., Dalvand, N., Ménard, M. Inverse-designed 90-degree silicon nitride bends for the C band. J. Light. Technol. 43, 5804–5810 (2025).

Shekhar, S. et al. Roadmapping the next generation of silicon photonics. Nat. Commun. 15, 751 (2024).

PsiQuantum team. A manufacturable platform for photonic quantum computing. Nature 641, 876–883 (2025).

Ahmed, S. R. et al. Universal photonic artificial intelligence acceleration. Nature 640, 368–374 (2025).

Caut, A., Girardi, M., Torres-Company, V., Larsson, A. & Karlsson, M. Channel Scalability of Silicon Nitride (De-) multiplexers for Optical Interconnects At 1 m. J. Lightwave Technol. 42, 276–286 (2023).

Shah, P., Ben Mellouk, E., Levine, J. & Mohanty, A. Mode-division multiplexing for visible photonic integrated circuits. Opt. Lett. 49, 5751–5754 (2024).

Kudalippalliyalil, R., Murphy, T. E. & Grutter, K. E. Low-loss and ultra-broadband silicon nitride angled MMI polarization splitter/combiner. Opt. Express 28, 34111–34122 (2020).

Tu, D. et al. 400 Gbps PAM4 and 280 Gbps NRZ silicon photonic transmissions with fabrication-tolerant silicon nitride CWDM4 filters. J. Lightwave Technol. 42, 302–308 (2023).

Yang, Y.-D., Li, Y., Huang, Y.-Z. & Poon, A. W. Silicon nitride three-mode division multiplexing and wavelength-division multiplexing using asymmetrical directional couplers and microring resonators. Opt. express 22, 22172–22183 (2014).

Zheng, X. et al. High performance on-chip polarization beam splitter at visible wavelengths based on a silicon nitride small-sized ridge waveguide. Opt. Express 31, 38419–38429 (2023).

Bhandari, B., Im, C.-S., Sapkota, O. R. & Lee, S.-S. Highly efficient broadband silicon nitride polarization beam splitter incorporating serially cascaded asymmetric directional couplers. Opt. Lett. 45, 5974–5977 (2020).

Guerber, S. et al. Broadband polarization beam splitter on a silicon nitride platform for O-band operation. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 30, 1679–1682 (2018).

Vanani, F. G., Fardoost, A., Li, G., & Doerr, C. Broadband polarization beam splitter rotator using only silicon nitride. Optical Fiber Commun. Conf. M1J–6. (2024).

Gallacher, K., Griffin, P. F., Riis, E., Sorel, M., & Paul, D. J. Silicon nitride waveguide polarization rotator and polarization beam splitter for chip-scale atomic systems. Apl. Photonics 7, 046101 (2022).

Feng, J. & Akimoto, R. A three-dimensional silicon nitride polarizing beam splitter. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 26, 706–709 (2014).

Sun, X., Aitchison, J. S. & Mojahedi, M. Realization of an ultra-compact polarization beam splitter using asymmetric MMI based on silicon nitride/silicon-on-insulator platform. Opt. Express 25, 8296–8305 (2017).

Sciancalepore, C. et al. O-band Echelle Grating Demultiplexers On Sinoi Featuring Low-loss And Reduced Thermal Sensitiveness. Integrated Optics: Devices, Materials, and Technologies XXII. 10–215. (2018).

Xie, S., Meng, Y., Bland-Hawthorn, J., Veilleux, S. & Dagenais, M. Silicon nitride/silicon dioxide echelle grating spectrometer for operation near 1.55 μm. IEEE Photonics J. 10, 1–7 (2018).

Cheung, S. S. & Tan, M. R. Silicon Nitride (Si_3N_4)(De-) Multiplexers for 1-μm CWDM Optical Interconnects. J. Lightwave Technol. 38, 3404–3413 (2020).

Sabri, L., Nabki, F. & Ménard, M. High-performance silicon nitride (de) multiplexer based on ring-assisted MZIs. Opt. Express 32, 10660–10668 (2024).

Gao, G. et al. Silicon nitride O-band (de) multiplexers with low thermal sensitivity. Opt. Express 25, 12260–12267 (2017).

Gostimirovic, D., Grinberg, Y., Xu, D.-X. & Liboiron-Ladouceur, O. Improving fabrication fidelity of integrated nanophotonic devices using deep learning. ACS Photonics 10, 1953–1961 (2023).

Ruiz, J. L. P., Rabih, A. A., Nabavi, S., Nabki, F., & Ménard, M. 1 x 5 MEMS Mode Selective Switch with an Inverse-Designed Silicon Nitride MDM. Optical Fiber Commun. Conf. Exhibition (OFC). 1–3 (2024).

Sun, A. et al. Edge-guided inverse design of digital metamaterial-based mode multiplexers for high-capacity multi-dimensional optical interconnect. Nat. Commun. 16, 1–12 (2025).

Molesky, S. et al. Inverse design in nanophotonics. Nat. Photonics 12, 659–670 (2018).

Pita, J., Nabki, F. & Ménard, M. Inverse-designed silicon nitride reflectors. Opt. Lett. 49, 786–789 (2024).

Pita Ruiz, J. L., Nabki, F. & Ménard, M. Silicon nitride TM-pass polarizer using inverse design. Opt. Express 31, 37892–37899 (2023).

Zhou, H. et al. Tunable on-chip mode converter enabled by inverse design. Nanophotonics 12, 1105–1114 (2023).

Song, C. et al. Ultracompact and broadband Si3N4 Y-branch splitter using an inverse design method. Opt. Express 32, 46080–46089 (2024).

Cheung, A. K. et al. Inverse-designed CWDM demultiplexer operated in O-band. Optical Fiber Commun. Conf. W1A–6 (2024).

Xu, D.-X., Gostimirovic, D., Grinberg, Y., Liboiron-Ladouceur, O. Advancing Silicon Photonics Through Machine Learning: From Device Design to Fabrication. 2024 IEEE 24th International Conference on Nanotechnology (NANO). 460–463 https://doi.org/10.1109/NANO61778.2024.10628655 (2024).

Naraine, C. M. et al. A moderate confinement O-, S-, C-, and L-band silicon nitride platform enabled by a rapid prototyping integrated photonics foundry process. IEEE Photonics J. 16, 1–15 (IEEE, 2024).

Su, L. et al. Nanophotonic inverse design with SPINS: software architecture and practical considerations. Appl. Phys. Rev. 7, 011407 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank CMC Microsystems for providing access to the ANT fabrication process. Furthermore, we are grateful to Mr. Cameron Horvath from ANT for his help with the description of the fabrication process. We would also like to thank Dr. Anna Wirth-Singh at Ansys Lumerical for the fruitful discussions on topology optimization. This research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the Center for Optics, Photonics and Lasers (COPL), and the Regroupement Stratégique en Microsystèmes du Québec (ReSMiQ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P. conducted the inverse design of the photonic components. J.P. and N.D. verified the designs and evaluated their robustness against fabrication variations. J.P. prepared the layouts, performed the layout refinement using the machine learning model, and submitted the designs for fabrication. J.P. and N.D. conceived and designed the experiments. Both developed and carried out all optical measurement sequences. J.P. and M.M. prepared the manuscript. M.M. supervised the project. All authors contributed to discussions and interpretation of the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Bert Offrein and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pita Ruiz, J.L., Dalvand, N. & Ménard, M. Integrated silicon nitride devices via inverse design. Nat Commun 16, 9307 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64359-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64359-1

This article is cited by

-

Breaking dense integration limits: inverse-designed lithium niobate multimode photonic circuits

Nature Communications (2025)