Abstract

Continuous time crystals (CTCs) are a phase of matter characterized by spontaneous breaking of continuous time-translation symmetry. Recently, CTCs have garnered interest due to breakthroughs in experimental implementation. Here we report the experimental observation of CTCs in noble-gas nuclear spins and uncover previously unexplored dynamical phenomena. We observe that the CTCs manifest as persistent limit cycle oscillations of nuclear spins, with coherence times exceeding hours. Notably, these oscillations are robust against noise perturbations and exhibit random time phases upon repetitive realization, epitomizing continuous time-translation symmetry-breaking intrinsic to CTCs. Additionally, we observe a dynamical phase featuring quasi-periodic oscillations and random time phases, indicating the emergence of the continuous time quasi-crystals proposed by recent theories. By varying the feedback strength and magnetic gradient, we observe complex dynamical phase transitions between time crystal phases and chaotic regimes. This work broadens the catalog of phases of spin gases and unlocks opportunities in precision measurements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Time crystals, which exhibit broken time-translation symmetry analogous to the broken space-translation symmetry in ordinary crystals, have captured interest from the physics community since their initial proposal. The original concept of time crystals involved closed systems and demonstrated continuous time-translation symmetry breaking through oscillatory dynamics1,2. However, a no-go theorem soon revealed that such time crystals are prohibited by nature3,4,5, prompting scientists to explore new possibilities. It has been theoretically argued that long-range interacting models in closed quantum systems could circumvent the no-go theorem6, and this model requires further exploration. One promising direction extends the concept of time crystals into periodically driven systems, known as discrete time crystals (DTCs)7,8,9,10,11. They break the discrete time-translation symmetry imposed by periodic external driving and are characterized by subharmonic oscillations. Numerous experimental realizations of DTCs have emerged12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Recently, another approach using open systems to circumvent the no-go theorem has gained attention22,23,24,25. This approach allows for continuous time crystals (CTCs) that continuously break time-translation symmetry, closely aligning with the spirit of the original proposal. To date, CTCs have been realized on several platforms, including atomic Bose-Einstein condensate26, metamaterial nanostructure27, semiconductor28, polariton condensate29, and Rydberg gas30. Currently, exploring time crystals across a diverse range of physical systems and uncovering their complex properties is at the forefront of scientific research.

Here we report the experimental observation of a CTC in noble-gas nuclear spins. Our experiments use 129Xe noble gas as a testbed, which interacts with overlapping 87Rb gas. The 87Rb gas measures the 129Xe spin signal and feeds this signal back to 129Xe through feedback coils. This feedback mechanism induces nonlinear interactions between 129Xe atoms, which are essential for the generation of CTCs. In such a noble gas, we observe limit cycle oscillations as signatures of a CTC and demonstrate their spontaneous breaking of continuous time-translation symmetry through random time phase distribution in repetitive measurements26. Interestingly, while magnetic field inhomogeneities are typically seen as detrimental due to their dephasing effects on spin relaxation, we introduce a gradient magnetic field in experiments, which enriches the dynamics of the noble gas. In this situation, we observe a dynamical phase featured by quasi-periodic oscillations and random time phases, indicating the emergence of the continuous time quasi-crystals (CTQCs). We investigate phase transitions of the time crystal across system parameters such as feedback strength and magnetic gradient. The phase diagram shows that the time crystal phase spans a wide range of parameters. Additionally, our time crystal can persist its oscillation pattern against temporal perturbations, verifying the robustness. Our work paves paths for realizing and exploring time crystals, offering opportunities for applications in fields such as quantum metrology.

Results

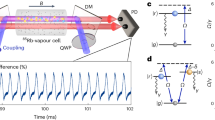

Our system, exemplified by the Rb-Xe configuration, integrates overlapping noble gas and alkali-metal gas. In the setup depicted in Fig. 1, the 129Xe nuclear spins are continuously optically pumped through spin exchange with embedded 87Rb31,32. These 87Rb atoms are polarized by a circularly polarized laser beam tuned to the Rb D1 transition at 795 nm. A linear gradient magnetic field is applied along the same direction as the Rb pump beam (z-axis), resulting in a continuous Larmor frequency distribution ρ(ω). The 129Xe nuclear spin component is measured via interactions with the 87Rb spins using a linearly polarized probe beam oriented along the x-axis33 (see Supplementary Fig. 1). The intensity change of the probe beam, which is proportional to the average 129Xe spin polarization \({\bar{P}}_{x}=\int\,\rho (\omega ){P}_{x}(\omega ){{{{\rm{d}}}}}\omega\), is recorded by a photodiode. The corresponding 129Xe signal is fed back to the nuclear spins as a magnetic field along y, expressed as \({B}_{{{{{\rm{f}}}}}}=-\alpha {\bar{P}}_{x}/\gamma\) where α represents the feedback strength and γ is the gyromagnetic ratio of 129Xe. More details about our feedback scheme can be found in the Supplementary Information.

The 129Xe atoms are polarized and detected through spin exchange collisions with optically pumped 87Rb, where 87Rb atoms are optically polarized by a circularly polarized pump beam and detected via a rotation of the polarization of a linearly polarized probe beam. The detected information of 129Xe spins is magnetically coupled to a feedback circuit, which feeds back real-time By through coils along y and induces nonlinear dynamics in 129Xe spins. The coils along z generate an inhomogeneous bias field Bz, resulting in a continuous Larmor frequency distribution. LP linear polarizer, λ/4 quarter-wave plate, PD photodiode, PEM photoelastic modulator.

When the feedback strength α is weak, the noble-gas nuclear spins exhibit a normal phase, with the spins polarized along the bias field. When the nonlinear interaction is sufficiently strong, three distinct dynamical phases emerge: limit cycle, quasi-periodic, and chaos. The limit cycle phase, which corresponds to the synchronization across different frequencies, is characterized by long-lived periodic oscillations, each with a singular, steady frequency. The quasi-periodic oscillations are superimposed by oscillators of two incommensurate frequencies ωs and ωτ, where the value of ωτ depends on the feedback strength and gradient field34. When the ratio of ωs/ωτ is irrational, these spin oscillations are ordered but not apparently periodic, different from the limit cycle phase. The application of a gradient magnetic field is crucial for the emergence of this spin phase. To illustrate the different dynamical behaviors of these phases, three representative experimental examples are presented below. In order to gain deeper insights into the spin dynamics, we numerically investigate the stable dynamics of the three corresponding phases.

We numerically simulate the phase portraits of the average spin polarization \(\{{\bar{P}}_{x},{\bar{P}}_{y},{\bar{P}}_{z}\}\) in three phases using the equations described in the Methods section. Additionally, Poincaré sections, defined by the intersections at Py = 0, are accentuated in the phase portrait figures to offer a more clear perspective. The phase portrait of the limit cycle is a closed loop, and its Poincaré section consists of two discrete points (Fig. 2a). They both represent a periodic oscillation in which the system revisits the same state after each period. The phase portrait of quasi-periodic phase traces a torus that never closes, implying the absence of a true period (Fig. 2b). Correspondingly, the Poincaré section forms closed curves, corroborating the quasi-periodic nature of the system by illustrating the regular yet non-repeating interplay of incommensurate frequencies. In the chaotic phase, the phase portrait reveals irregular surfaces formed by a dense, scattered distribution of points (Fig. 2c). The dense distribution of points reflects the underlying chaos, where minor perturbations in initial conditions induce substantial trajectory divergence. Additionally, the corresponding Poincaré section exhibits a self-similar pattern of densely scattered points, providing further evidence of the chaotic behavior. Next, we present the experimentally measured signal of the one-dimensional component \({\bar{P}}_{x}\).

a–c Phase portraits of the average spin polarization {Px, Py, Pz} and corresponding Poincaré sections (accentuated) at Py = 0 from numerical simulation. d–f Fourier spectrum (normalized) obtained through the fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the intensity signal recorded by PD in the stationary window (inset). g–i Relative time phase distribution. Each point represents the Fourier amplitude at the same peak frequency on the complex plane. Each experiment is performed at α ≈ 42.52 rad/s, g ≈ 50 nT/cm for the Limit cycle phase; α ≈ 159.62 rad/s, g ≈ 50 nT/cm for the Quasi-periodic phase; α ≈ 350.86 rad/s, g ≈ 50 nT/cm for the Chaotic phase.

In the experiment, after a transient build-up process, the system levels into stable oscillations and maintains stable dynamic behaviors (see Supplementary Fig. 4). For demonstration, we extract 1000-s segments from the steady states of the three distinct dynamical phases. Figure 2d shows a representative time trace of the probe intensity signal in the stationary window, along with the corresponding spectrum for the limit cycle phase. The time trace reveals impeccably periodic oscillations, showcasing both a stable amplitude and frequency. By performing a fast Fourier transformation on the data recorded during this interval, we unveil its Fourier spectrum, which is dominated by a single, narrow peak. The linewidth of this peak is constrained solely by the duration of the acquisition time, underscoring the precision and stability of the oscillatory behavior. The observed limit cycle phase emerges through spontaneous breaking of continuous time-translation symmetry (as discussed below), and is a distinctive signature of the CTC.

Figure 2e illustrates a quintessential example of the quasi-periodic phase observed in our experiment. In this phase, the Fourier spectrum reveals peaks that are equidistantly spaced. The time traces are ordered but non-periodic, which are characteristic of recently proposed time quasi-crystal35,36,37. As an example, ref. 35 revealed the emergence of a time quasi-crystal in the presence of a “staircaselike” on-site potential. It is worth noting that a similar quasi-periodic oscillation has recently been observed in an atom-cavity system38. In contrast to the recently demonstrated discrete time quasi-crystals39,40, our observation of the quasi-periodic phase suggests the emergence of CTQCs.

A typical example of a chaotic phase is shown in Fig. 2f. The temporal signal is composed of wave packets, but the period and amplitude of these wave packets vary randomly over time. The corresponding Fourier spectrum features broadened peaks and noisy wings. To confirm the chaotic nature of this phase, we employ the Chaos Decision Tree Algorithm (see Supplementary Information)41. The chaos criteria processes time series recordings and outputs a single value K, which approaches 1, signifying chaotic systems, whereas a value nearing 0 indicates periodic or quasi-periodic systems. The value of K is approximately 0.9819 for the chaotic phase shown as Fig. 2f. For comparison, the value of K is approximately 0.0016 for the limit cycle phase as depicted in Fig. 2d, and 0.0028 for the quasi-periodic phase as depicted in Fig. 2e. For our data, this method is consistent with the maximum Lyapunov exponent and correlation dimension in identifying chaotic behavior (see Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). The observed chaotic oscillations disrupt the ideal periodicity or quasi-periodicity over time and can be interpreted as the “melting” of the time-ordered phases, including the CTC and CTQC.

We investigate the spontaneous breaking of continuous time-translation symmetry in CTCs and CTQCs. To confirm that this symmetry breaking occurs spontaneously, the periodic oscillation of a noble gas should manifest at any arbitrary initial phase, leading to a random relative time phase across various repeated realizations26,27. To verify that the oscillations in our experimental system exhibit arbitrary time phases, we repeatedly measure the limit cycle and quasi-periodic phases under fixed experimental parameters. For comparison, the time phase in the chaotic phase is also repeatedly measured. The measured time phase of the limit cycle is shown in Fig. 2g, displaying a random distribution between [0, 2π], corresponding to complex Fourier amplitudes around a loop. This confirms the spontaneous breaking of continuous time-translation symmetry in the limit cycle phase. Accurate feedback activation is essential for determining the relative time phase. To achieve this, we design a high-precision feedback switch control circuit along with synchronized data acquisition (see Supplementary Information). The quasi-periodic phase exhibits similar properties, with the complex Fourier amplitude at each frequency randomly distributed on the respective loop, and their time phases covering [0, 2π] (Fig. 2h). Our numerical simulations show that the 2π random phase distribution could arise from initial fluctuations (see Supplementary Fig. 2). This distribution emerges due to the spontaneous breaking of continuous time-translation symmetry, and not all self-oscillations in nonlinear systems exhibit this characteristic 2π random phase behavior (see Supplementary Fig. 3).

In contrast, the chaotic phase displays distinctly different characteristics, lacking stable oscillation. In a chaotic noble-gas system, a Fourier peak may not consistently appear in other intervals of a single realization or across different realizations. As a result, when attempting to calculate the phase of the Fourier amplitude at the same frequency in repeated measurements of chaotic systems, it is often impossible to obtain the same peak’s phase for each measurement. The distribution of the calculated time phase in chaos is shown in Fig. 2i, where all points scatter across a circular surface. This scattering occurs because most points do not correspond to a peak but rather to the broadened baseline or noisy wings.

We now investigate the phase transition as feedback strength increases. Figure 3a presents the phase diagram derived from the Fourier spectra at various feedback strengths α, with a fixed magnetic gradient g ≈ 50 nT/cm. Initially, under weak feedback, the phase of the noble gas remains stable at a no-signal fixed point. Upon surpassing a critical feedback strength (in our experiment, this threshold is α ≈ 9.57 rad/s), the limit cycle phase emerges, although the oscillation amplitude diminishes as the feedback increases. As the feedback strength continues to rise, the quasi-periodic phase emerges, revealing an increasing number of harmonics. For example, at α ≈ 265.77 rad/s, around 17 peaks can be distinctly identified, each possessing nearly identical linewidths, below 1 mHz. The frequency comb gradually stretches with increasing feedback. With even stronger feedback, chaotic oscillations manifest, rendering the spectrum blurred. It is crucial to note that these observations are made in a gradient field; without this gradient field, neither quasi-periodic nor chaotic phases are observed.

a The phase diagram and K dependence on feedback strength α at a fixed magnetic gradient g ≈ 50 nT/cm. The frequency in the phase diagram represents the shift relative to the central frequency. b The phase diagram and K dependence on magnetic gradient g at a fixed feedback strength α ≈ 276.48 rad/s.

We observe an unusual phase transition from a chaotic phase back to CTC phases. Previous works only reported the melting of the time crystal into a chaotic phase without noting this reverse transition. In contrast, our investigation under various magnetic gradients uncovers this anomalous behavior. As depicted in Fig. 3b, the CTC phase undergoes a cycle of formation, “melting”, and re-formation with increasing magnetic gradient g. Initially, similar to the phase transition pattern observed with varying feedback strength, the periodic oscillation of the noble-gas spins emerges. As the magnetic gradient g increases, the oscillation amplitude slightly diminishes and the range extends. Then, chaos abruptly emerges at g ≈ 80 nT/cm, indicated by a sudden change in the K value. However, in a distinct deviation from previous observations, the chaotic phase disappears, followed by the re-emergence of a limit cycle phase above a critical value of g ≈ 92 nT/cm. These dynamical transitions can be understood as bifurcations or as the onset and breakdown of synchronization. For example, at large magnetic field gradients, the broader frequency distribution ρ(ω) decreases the number of spins contributing to each frequency mode, thereby facilitating resynchronization and enabling the re-emergence of a limit cycle from chaos. Similar transitions have been observed in other nonlinear systems—for instance, in the Lorenz system, increasing the Rayleigh parameter r beyond a critical threshold induces a transition from chaotic behavior back to a limit cycle42,43.

In order to more comprehensively demonstrate the dependence of the time crystal behavior on the feedback strength α and the field gradient g, a phase diagram spanning the two-dimensional parameter space (α, g) is provided in the Supplementary Fig. 5. It is worth noting that, while recent theoretical work (ref. 34) explores similar phase transitions between limit cycles, quasi-periodicity, and chaos, it based on simple models that differ from our experimental conditions, leading to qualitatively different outcomes.

Having demonstrated the spontaneous breaking of continuous time-translation symmetry, we further verify the time crystalline nature of our system by examining its robustness against noise—a distinctive and desirable feature of time crystals that stems from the feedback-induced nonlinearity. We demonstrate this robustness by showing the persistence of the oscillation pattern against temporal perturbations. In experiments, we introduce white noise of varying intensities into the transverse feedback field as a test. Figure 4 illustrates the intensity spectrum at different levels of magnetic noise. In the low noise regime, the intensity signal retains the fundamental oscillation pattern similar to the noise-free situation. As the noise strength increases, additional noisy peaks emerge, yet the fundamental oscillation pattern remains clearly recognizable. With further increases in noise strength, the noise gradually begins to dominate the ordered oscillation. The corresponding K value (see inset) shows how increasing noise strength “melts” the time crystal. These observations demonstrate that the observed time crystal can withstand a range of noise levels. This, combined with the persistence of the time crystal across a wide range of system parameters, confirms the robustness of the observed time crystal.

Fourier spectrum and corresponding K value (inset) of the probe beam intensity signal at increasing noise strength, performed at fixed α ≈ 42.52 rad/s, g ≈ 50 nT/cm. The light blue spectrum at the bottom is the noise-free case, and the deepening of blue corresponds to the increase in the noise strength. The frequency represents the shift relative to the central frequency.

Discussions

Time crystals can manifest within nonlinear dynamical systems. However, not all nonlinear auto-oscillation behaviors qualify as CTCs. While CTCs share certain properties with general nonlinear systems, such as robustness against noise, it is the spontaneous symmetry breaking of continuous time-translation symmetry that fundamentally distinguishes them. In this work, the criterion for CTCs associated with spontaneous breaking of continuous time-translation symmetry is defined following ref. 26, and is manifested as the random and uniform distribution of oscillation phases. Distinctively, in the DTC scenario, the phase distribution can become non-uniform or concentrated in particular sectors of the circle, as described in ref. 44. The rich spectrum of dynamical phases and the transitions observed in our system naturally arise from bifurcations within the nonlinear dynamics framework. Alternatively, these phenomena may be further interpreted with the synchronization theory, which offers a unifying perspective on complex collective behavior in coupled oscillator systems45,46. In our setup, the applied magnetic field gradient introduces a continuous distribution of Larmor frequencies ω, effectively treating each nuclear spin mode as an individual oscillator. These modes are globally coupled via the nonlinear feedback field (with strength α), while the gradient (characterized by g) imposes a frequency detuning across the ensemble—analogous to the mismatch of intrinsic frequencies in canonical synchronization models. The interplay between nonlinear coupling and detuning governs the emergence and breakdown of synchronization, giving rise to the observed dynamical phases. The limit cycle phase corresponds to a synchronized state with a dominant frequency, whereas quasi-periodic and chaotic dynamics emerge when synchronization is frustrated.

Our work expands the range of physical platforms for realizing time crystals and enriches the exploration of their properties. We introduce a key ingredient—a magnetic field gradient—that enriches the dynamical behavior of the noble-gas spin system, enabling the emergence of quasi-periodic and chaotic phenomena. While our demonstration focuses on an Rb-Xe hybrid gas system, we believe that integrating magnetic field gradients with feedback, as demonstrated in our work, is widely applicable across various platforms. This includes systems such as alkali-metal atomic gases, nuclear spin liquids47, and others. Furthermore, although we adopted the current feedback technique48,49, we believe our methodology is equally extensible to other feedback mechanisms. This implementation of time crystals would open up possibilities for exploring non-equilibrium phases of matter. Notably, due to experimental constraints such as limited lifetimes, chaos has rarely been observed in CTC research26,27,29,30, with a recent example documented only in an electron-nuclear spin system in semiconductors28.

Beyond its intrinsic conceptual interest, our work on time crystals holds practical value in quantum metrology. For example, the limit cycle phase and the corresponding precise control of feedback in our CTCs represent a crucial class of spin masers48,49. Spin masers, with their long-lived persistent oscillations and robustness, can be widely applied in various fields, such as high-precision magnetometry49, searches for electric dipole moments50, tests of fundamental symmetry51, and probes of new physics52. Our spin maser is particularly notable for oscillating at low frequencies (approximately 10 Hz) while maintaining high relative frequency accuracy. This makes it ideal for experimental investigations on fundamental questions in physics, where associated frequencies or frequency shifts are small51. Furthermore, existing masers lack diverse dynamic phases, which limits further exploration. In contrast, the quasi-periodic phase with split frequencies in our CTQCs exhibits richer dynamic behavior, successfully enabling the creation of a multimode maser.

Methods

Under the feedback scheme, the system dynamics are governed by a Hamiltonian that includes Zeeman interactions with the gradient and feedback magnetic field, spin exchange interactions with polarized 87Rb atoms, and relaxation mechanisms. Further details can be found in the Supplementary Information. Neglecting quantum fluctuations, the dynamics of 129Xe spins can be described by the evolution of spin operator expectation values. Here, the spin polarization is defined as the normalized expectation value of 129Xe spin operator, P = 2〈K〉. For our spin-1/2 system, the evolution of the polarization can be formally expressed as a set of nonlinear Bloch equations:

where T1(T2) is 129Xe longitudinal (transverse) relaxation time, RSE is the pumping rate through spin exchange collisions with 87Rb. The feedback-induced nonlinear terms, \(\alpha {P}_{z}(\omega )\int\,\rho ({\omega }^{{\prime} }){P}_{x}({\omega }^{{\prime} }){{{{\rm{d}}}}}{\omega }^{{\prime} }\) and \(\alpha {P}_{x}(\omega )\int\,\rho ({\omega }^{{\prime} }){P}_{x}({\omega }^{{\prime} }){{{{\rm{d}}}}}{\omega }^{{\prime} }\), can give rise to auto-oscillations that may exhibit collective synchronization, multi-frequency dynamics, or chaotic behavior. These phenomena can be understood within the general framework of the dynamics of nonlinear oscillating systems42,43,45,46. Using this set of equations, we investigate alternative feedback configurations, for instance by applying feedback along different magnetic field directions, in which the dynamical phases reported in this work are no longer observed (see Supplementary Fig. 8).

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Source data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Wilczek, F. Quantum time crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 160401 (2012).

Shapere, A. & Wilczek, F. Classical time crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 160402 (2012).

Nozières, P. Time crystals: Can diamagnetic currents drive a charge density wave into rotation? Europhys. Lett. 103, 57008 (2013).

Bruno, P. Impossibility of spontaneously rotating time crystals: a no-go theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 070402 (2013).

Watanabe, H. & Oshikawa, M. Absence of quantum time crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 251603 (2015).

Kozin, V. K. & Kyriienko, O. Quantum time crystals from hamiltonians with long-range interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 210602 (2019).

Sacha, K. & Zakrzewski, J. Time crystals: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 81, 016401 (2017).

Khemani, V., Moessner, R. & Sondhi, S. A brief history of time crystals. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1910.10745 (2019).

Sacha, K. Time Crystals Vol. 114 (Springer, 2020).

Else, D. V., Monroe, C., Nayak, C. & Yao, N. Y. Discrete time crystals. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 11, 467–499 (2020).

Zaletel, M. P. et al. Colloquium: quantum and classical discrete time crystals. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 031001 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Observation of a discrete time crystal. Nature 543, 217–220 (2017).

Choi, S. et al. Observation of discrete time-crystalline order in a disordered dipolar many-body system. Nature 543, 221–225 (2017).

Pal, S., Nishad, N., Mahesh, T. & Sreejith, G. Temporal order in periodically driven spins in star-shaped clusters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 180602 (2018).

Rovny, J., Blum, R. L. & Barrett, S. E. Observation of discrete-time-crystal signatures in an ordered dipolar many-body system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 180603 (2018).

Kyprianidis, A. et al. Observation of a prethermal discrete time crystal. Science 372, 1192–1196 (2021).

Randall, J. et al. Many-body–localized discrete time crystal with a programmable spin-based quantum simulator. Science 374, 1474–1478 (2021).

Mi, X. et al. Time-crystalline eigenstate order on a quantum processor. Nature 601, 531–536 (2022).

Taheri, H., Matsko, A. B., Maleki, L. & Sacha, K. All-optical dissipative discrete time crystals. Nat. Commun. 13, 848 (2022).

Wang, B. et al. Observation of photonic topological Floquet time crystals. Laser Photonics Rev. 16, 2100469 (2022).

Frey, P. & Rachel, S. Realization of a discrete time crystal on 57 qubits of a quantum computer. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm7652 (2022).

Iemini, F. et al. Boundary time crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 035301 (2018).

Buča, B., Tindall, J. & Jaksch, D. Non-stationary coherent quantum many-body dynamics through dissipation. Nat. Commun. 10, 1730 (2019).

Keßler, H., Cosme, J. G., Hemmerling, M., Mathey, L. & Hemmerich, A. Emergent limit cycles and time crystal dynamics in an atom-cavity system. Phys. Rev. A 99, 053605 (2019).

Keßler, H. et al. Observation of a dissipative time crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 043602 (2021).

Kongkhambut, P. et al. Observation of a continuous time crystal. Science 377, 670–673 (2022).

Liu, T., Ou, J.-Y., MacDonald, K. F. & Zheludev, N. I. Photonic metamaterial analogue of a continuous time crystal. Nat. Phys. 19, 986–991 (2023).

Greilich, A. et al. Robust continuous time crystal in an electron–nuclear spin system. Nat. Phys. 20, 631–636 (2024).

Carraro-Haddad, I. et al. Solid-state continuous time crystal in a polariton condensate with a built-in mechanical clock. Science 384, 995–1000 (2024).

Wu, X. et al. Dissipative time crystal in a strongly interacting Rydberg gas. Nat. Phys. 20, 1389–1394 (2024).

Walker, T. G. & Happer, W. Spin-exchange optical pumping of noble-gas nuclei. Rev. Mod. Phys. 69, 629 (1997).

Gentile, T. R., Nacher, P., Saam, B. & Walker, T. Optically polarized 3He. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 045004 (2017).

Wu, Z., Kitano, M., Happer, W., Hou, M. & Daniels, J. Optical determination of alkali metal vapor number density using Faraday rotation. Appl. Opt. 25, 4483–4492 (1986).

Wang, T., Luo, Z., Zhang, S. & Yu, Z. Feedback-induced nonlinear spin dynamics in an inhomogeneous magnetic field. Commun. Phys. 8, 41 (2025).

Pizzi, A., Knolle, J. & Nunnenkamp, A. Period-n discrete time crystals and quasicrystals with ultracold bosons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 150601 (2019).

Giergiel, K., Kuroś, A. & Sacha, K. Discrete time quasicrystals. Phys. Rev. B 99, 220303 (2019).

Solanki, P. & Minganti, F. Chaos in time: a dissipative continuous quasi time crystals. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.07297 (2024).

Cosme, J. G. et al. Torus bifurcation of a dissipative time crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 223601 (2025).

He, G. et al. Experimental realization of discrete time quasi-crystals. Phys. Rev. X 15, 011055 (2025).

Autti, S., Eltsov, V. & Volovik, G. Observation of a time quasicrystal and its transition to a superfluid time crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 215301 (2018).

Toker, D., Sommer, F. T. & D’Esposito, M. A simple method for detecting chaos in nature. Commun. Biol. 3, 11 (2020).

Strogatz, S. H. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2024).

Sparrow, C. The Lorenz Equations Vol. 109 (Springer New York, 1982).

Kongkhambut, P. et al. Observation of a phase transition from a continuous to a discrete time crystal. Rep. Prog. Phys. 87, 080502 (2024).

Pikovsky, A., Rosenblum, M. & Kurths, J. Synchronization: A Universal Concept in Nonlinear Sciences (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Greilich, A., Kopteva, N. E., Korenev, V. L., Haude, P. A. & Bayer, M. Exploring nonlinear dynamics in periodically driven time crystal from synchronization to chaotic motion. Nat. Commun. 16, 2936 (2025).

Suefke, M., Lehmkuhl, S., Liebisch, A., Blümich, B. & Appelt, S. Para-hydrogen raser delivers sub-millihertz resolution in nuclear magnetic resonance. Nat. Phys. 13, 568–572 (2017).

Yoshimi, A. et al. Nuclear spin maser with an artificial feedback mechanism. Phys. Lett. A 304, 13–20 (2002).

Jiang, M., Su, H., Wu, Z., Peng, X. & Budker, D. Floquet maser. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe0719 (2021).

Asahi, K. et al. Fundamental physics with polarized nuclear spins—spin maser for the neutron EDM measurement. Czechoslov. J. Phys. 50, 179–186 (2000).

Heil, W. et al. Spin clocks: probing fundamental symmetries in nature. Ann. Phys. 525, 539–549 (2013).

Safronova, M. et al. Search for new physics with atoms and molecules. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 025008 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology (Grant No. 2021ZD0303205), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants Nos. T2388102, 92476204, 12274395, 12261160569, and 12404341), Youth Innovation Promotion Association (Grant No. 2023474), the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDB1300000), and the New Cornerstone Science Foundation through the XPLORER PRIZE. Z.L. was supported by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2024A1515011406), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Sun Yat-sen University (Grant No. 23qnpy63), and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory (Grant No. 2019B121203005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H. and T.W. designed and performed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; H.Y. analyzed the data; M.J., Z.L., and X.P. proposed the experimental concept, devised the experimental protocols, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Alex Greilich, Chong Zu, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Y., Wang, T., Yin, H. et al. Observation of continuous time crystals and quasi-crystals in spin gases. Nat Commun 16, 9375 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64413-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64413-y