Abstract

Current catalytic materials and processes designed for water treatment face a significant challenge in balancing reactivity and stability. Catalysts with initially high reactivity often lack long-term stability under environmentally relevant conditions, limiting their advancement toward practical application. In this study, we demonstrate that spatial confinement of catalysts at angstrom scale can significantly enhance the stability of iron oxyfluoride (FeOF), a highly efficient catalyst for advanced oxidation. We fabricate a catalytic membrane by intercalating FeOF catalysts between layers of graphene oxides. In flow-through operation, the catalytic membrane maintains near-complete removal of model pollutants, neonicotinoids, for over two weeks by effectively activating H2O2 to generate •OH. Catalyst deactivation is significantly mitigated by spatially confining fluoride ions leached from the catalyst, which is identified as the primary cause of catalytic activity loss. The angstrom-scale membrane channels effectively reject the majority of natural organic matter via size exclusion, thereby preserving radical availability and sustaining pollutant degradation under practical conditions. This innovative strategy for enhancing catalyst stability can be potentially applied to other existing catalysts developed for water treatment applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

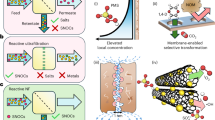

The presence of anthropogenic organic pollutants in water resources has become a global concern, posing significant threats to the natural environment and human health1,2. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) are considered a viable water treatment option, as they target transforming organic pollutants to benign products by employing highly oxidative radicals such as hydroxyl radical (•OH)3,4,5. Among various catalytic schemes to achieve AOPs, membranes loaded with catalysts that activate AOP precursor such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) have been extensively pursued as a practical approach at the device level. These catalytic membranes are designed to function both as a membrane–rejecting larger organics and colloids via size exclusion–and as a catalyst–catalytically destroying smaller pollutants that pass through membrane pores6.

Catalysts with various morphologies, such as single-atom, metal-organic framework, and covalent organic framework, have been explored as active components of catalytic membranes7,8. While some catalytic membranes show great promise for high-efficiency water treatment, one widely acknowledged limitation is the challenge of balancing initial high catalytic activity with long-term catalyst stability. Catalyst deactivation becomes more pronounced when the catalytic scheme primarily targets producing a large amount of •OH for rapid pollutant oxidation. In addition to reaching target micropollutants, which typically occur at ppt-ppb levels9,10,11, •OH ( < 10 μs) can react adversely with the catalysts themseleves12,13, compromising system longevity and producing unintended byproducts.

Developing AOP catalysts that are both highly reactive and stable over long period presents a dilemma. Constructing protective composite structures by introducing additional chemically robust materials14,15,16 (e.g., Fe@Fe2O3 with a stable Fe2O3 outer layer17) would inevitably lower the catalysis kinetics. The same challenge emerges when milder reactive oxygen species (ROS) substitutes3, such as singlet oxygen (1O2), are pursued as the main oxidant. Circumventing the problem related to oxidants and employing a completely different mechanism, such as non-radical pathway18 (e.g., phenol polymerization on FeOCl19), can be applied to niche applications, but deviates from the original objective of AOP in non-selectively removing a wide range of pollutants20.

In this study, we propose spatial confinement as an innovative strategy to enhance the long-term efficacy of AOP catalysts in catalytic membranes. We employ single-layer graphene oxide as a flexible matrix to confine iron oxyfluoride (FeOF)—one of the most efficient heterogeneous Fenton catalysts reported to date—and form a catalytic membrane with an aligned layer structure. We demonstrate the catalytic reaction in angstrom-scale confined spaces ( < 1 nm) within the membrane channels significantly improve both the durability and activity of the confined FeOF. We discuss the key reasons for FeOF deactivation during AOP and the mechanism by which spatial confinement enhances the catalyst stability while preserving catalytic efficiency.

Results

Synthesis of representative iron oxyhalides

The selection of catalysts plays a critical role in the performance of catalytic membranes. Among readily available options of AOP catalysts, iron oxyhalides have gathered significant attention due to their exceptional catalytic efficacy. Studies have shown that FeOCl and FeOF outperform the other conventional catalysts in both powder suspensions and catalytic membranes for pollutant degradation21,22. However, they have been criticized for offering remarkable activation efficiency only in the short term but suffering from relatively poor material durability21,23,24,25,26.

To verify the (in)stability of iron oxyhalides, we fabricated FeOCl by pyrolyzing FeCl3·6H2O at 220 °C for 2 h in a muffle furnace21, and FeOF by heating FeF3·3H2O in methanol medium at 220 °C for 24 h in an autoclave (Supplementary Fig. 1). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns confirmed alignments of both FeOCl and FeOF with their PDF cards retrieved from JCPDS database (Fig. 1a). The inverse Fourier transformation of the selected transmission electron microscopy (TEM) region revealed that the primary exposed crystalline plane of the synthesized FeOF was assigned to its (110) plane (Fig. 1b), consistent with the result reported in previous report27. Apart from the primary (010) plane obtained from XRD pattern, the fabricated FeOCl exhibited hybrid crystalline planes on the surface (Supplementary Fig. 2), including (110), (120), (121), etc. Both materials displayed a layered morphology which was corroborated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and TEM images (Supplementary Figs. 3-4). The original FeOCl and FeOF were fully digested (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Text 1) to determine their accurate chemical compositions using inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) for Fe and ion chromatography (IC) for halogens, which were Fe1.14OCl1.17 and Fe1.75OF3.45, respectively. It is important to determine whether additional ions were adsorbed on the material surface during synthesis, as these could potentially influence the subsequent catalytic processes. To unravel this, we also performed an acid-washing treatment to the freshly synthesized materials (Supplementary Table 1). The close elemental ratios before and after acid treatment indicate that the discrepancy between the theoretical atomic ratios and the measured values (from total digestion) is primarily attributable to the intrinsic material defects, rather than the surface-adsorbed species.

a XRD patterns of iron oxyhalides. b SEM, SEM-EDS mapping, TEM, HAADF-TEM images, and inverse Fourier transformation of the selected region (6.252 nm2) in TEM for the FeOF. c Comparison of H2O2 activation efficiency for different catalysts from EPR ([catalyst] = 1 g L–1, [H2O2] = 50 mM, [DMPO] = 200 mM, pH = 6.2 ± 0.1). d DMPO–OH signal generated by different catalysts ([catalyst] = 1 g L–1, [H2O2] = 50 mM, [DMPO] = 200 mM, pH = 6.2 ± 0.1). e Removal efficiency for representative neonicotinoid ([catalyst] = 1 g L–1, [H2O2] = 10 mM, [THI] = 10 μM, pH = 6.2 ± 0.1, reaction time = 60 min, standard deviations (n = 3) were presented). f F 1 s XPS spectra of FeOF before and after H2O2 activation. g H2O2 activation efficiency of spent FeOF after reacting with H2O2 for a certain period ([catalyst] = 1 g L–1, [H2O2] = 10 mM, contact time = 1, 2, 3 or 4 h, [DMPO] = 200 mM, pH = 6.2 ± 0.1, reaction time = 1 min). h Element leaching over time in suspension systems ([catalyst] = 1 g L–1, [H2O2] = 10 mM, pH = 6.2 ± 0.1).

The H2O2 activation efficiency of the catalysts was evaluated using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy with 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) as the spin trapping agent (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Text 2). The synthesized layered FeOF demonstrated the highest radical generation efficiency compared to benchmark iron-based catalysts, as well as FeOCl (Fig. 1c). The activation efficiency can be quantitatively compared by spin concentration of the generated DMPO–OH28. In accordance with the results in the literature22,29, both FeOCl and FeOF showed significantly superior catalytic performance over the benchmark catalysts, with FeOF surpassing FeOCl by 4.7 times in DMPO–OH signal intensity (Fig. 1d).

However, after recovering the catalysts by filtration and vacuum drying, the catalytic performance of second-run FeOCl and FeOF weakened markedly. The signal intensity of spent FeOCl and FeOF decreased by 67.1% and 70.7%, respectively, compared to their fresh forms. This trend was also observed in the removal rate of thiamethoxam (THI), one of neonicotinoids which are the most common insecticide pollution in the global groundwater30,31,32. The potency of FeOCl and FeOF showed a severe reduction of 77.2% and 75.3%, respectively, in the second run (Fig. 1e). The results imply that the powder-form iron oxyhalides would undergo deactivation during the catalytic oxidation in bulk suspension23. Although the FeOF led in •OH generation efficiency, its THI degradation did not transcend that of the FeOCl with a same level, possibly ascribed to the rapid quenching of •OH in bulk reaction.

Significant halide leaching during catalytic oxidation

To further investigate this deactivation process, the changes in material surface before and after catalytic oxidation were examined using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Results indicate that FeOF lost a significant fraction of both F (40.2 at.%) and Fe (33.0 at.%) during H2O2 activation (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 6). SEM and TEM images revealed that the leaching of elements led to a corroded morphology (Supplementary Fig. 7). FeOCl showed even more pronounced leaching degree (Cl 76.1 at.%, Fe 43.2 at.%), possibly due to the lower electronegativity of Cl (3.16 on the Pauling scale), which decreased its coordination strength to the Fe core23 (Supplementary Fig. 8). After the reaction, XPS peaks assigned to halogens shifted to higher binding energies (FeOF +0.43 eV, FeOCl +0.18 eV), possibly indicating the crucial role of halogens as critical species in H2O2 activation. The efficiency of •OH generation also strongly correlated with the remaining surface halogen content in the iron oxyhalides (R² = 0.97–0.99), suggesting that halogen loss was probably the decisive factor in catalyst deactivation (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 9).

Heterogenous catalysts applied in catalytic oxidation are commonly reported to proceed through peroxide adsorption as the first reaction step3,33. However, there is limited research that comprehensively studied how the peroxide adsorption behaviors correlate with element leaching. Therefore, we monitored the elements leaching of Fe and halides over time using ICP-OES and IC. We calculated that the halide contents continuously leached into the solution over time, resulting in a loss of 93.5% Cl for FeOCl and 40.7% F for FeOF after a 12-hour reaction with H2O2 (Fig. 1h). Under the severe halogen loss, compositions of the spent FeOCl and FeOF changed to Fe0.47OCl0 and Fe0.85OF1.18, respectively. In contrast, the leached Fe amount for both iron oxyhalides increased in the initial 2 h but plateaued during the later phase of reaction. The overall Fe leaching amounts for both FeOF and FeOCl were not significant during reaction (Supplementary Table 1), and the leaching of both Fe and halides was negligible without the presence of H2O2. The results indicate the important role of halogens in catalytic reaction, and challenges the conventional understanding that the deactivation of catalysts is mainly due to leaching or overoxidation of metal elements34. The H2O2 consumption was also measured during leaching experiments (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Text 3), and the results indicate that the FeOF exhibited a 2.3 times higher H2O2 activation rate compared to FeOCl. A higher DMPO–OH generation in initial stage (1 min) and a faster reaction rate over the long run (6 h) both suggest the superior capability of FeOF in catalytic oxidation.

Irreversible halide loss during bulk catalysis

The leaching-to-performance correlation was different for FeOCl and FeOF during reaction, where FeOF showed a lower leaching but a better H2O2 activation capability than FeOCl. To verify whether halogen-rich environment would impact the catalytic process, 0.5 M F− or Cl− was added during the H2O2 activation to intentionally increase the chance of halogen recombination with the Fe core. In the second run, the F-treated spent FeOF exhibited significantly better catalytic performance in THI removal (76.9% in 1 h) compared to the untreated spent FeOF (18.6%), approaching the performance of the fresh FeOF (83.5%) (Fig. 2a). Similarly, the Cl-treated spent FeOCl was also improved with a higher catalytic performance (26.8%) than the untreated spent FeOCl (14.6%), although less close to the fresh FeOCl (64.1%) compared with its counterpart. Different types of halogens failed to recover the catalytic performance of iron oxyhalides. Furthermore, the spent FeOF was placed in different levels of F− ion (0.1–0.5 M F−) to activate H2O2, and the resultant EPR signals showed a positive correlation with the ambient F− concentration (Fig. 2b). Similarly, the performance of spent FeOF in THI degradation increased under high concentration of F− (68.2% with 0.5 M F−). These results suggest that either mitigating halide diffusion or ensuring timely recovery of halide to the catalyst surface is the key to maintaining the activity of iron oxyhalides. Probe sonication was performed to exfoliate the fresh FeOF, which artificially reduced its F−-holding capacity by disrupting the intrinsic F−-bridged layered structure and introducing additional structural defects. The markedly decreased catalytic performance ( < 10%) and the reduced fluorine content (from 55.6% to 12.5%, Supplementary Table 1) further supported the correlation between fluorine retention and catalytic efficacy.

a THI degradation by iron oxyhalides, their spent forms, and their halide-treated spent forms ([catalyst] = 1 g L–1, [H2O2] = 10 mM, reaction time = 1 h, [Cl– or F–] = 0.5 M, [THI] = 10 μM, pH = 6.2 ± 0.1, standard deviations (n = 3) were presented). b H2O2 activation efficiency and THI degradation of spent FeOF under F-rich environment ([catalyst] = 1 g L–1, [H2O2] = 10 mM, [F–] = 0.1, 0.2 or 0.5 M, [THI] = 10 μM for reaction time of 60 min, [DMPO] = 200 mM for reaction time of 1 min, pH = 6.2 ± 0.1, standard deviations (n = 3) were presented). c Theoretical bond length and Bader charge in iron oxyhalides, where the higher electronegativity of fluoride reflects its stronger nucleophilic nature to complete the redox cycle. d Fourier transform of k2-weighted EXAFS spectra of iron oxyhalides. The structures of iron oxyhalides match with that of Fe2O3, and the spectra of other reference materials could refer to Supplementary Fig. 14. e Schematic illustration of the reaction mechanism in FeOF-based Fenton system.

To evaluate the affinity of iron oxyhalides for uncoordinated halide ions, we pre-saturated fresh FeOCl and FeOF in a halide-rich solution (0.5 M) overnight to allow for potential adsorption of free halide species. The halide-saturated materials were then filtered and immediately subjected to catalytic testing. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 11, no significant change in catalytic performance was observed. This suggests a low adsorptive affinity of FeOCl and FeOF toward uncoordinated halide ions, likely due to their highly crystalline nature and limited surface area (15.46 m2 g–1 for FeOCl and 3.19 m2 g–1 for FeOF; Supplementary Table 2), which restricts the availability of physisorption sites capable of retaining free halide ions.

We employed density functional theory (DFT) calculations, based on the VASP package, to evaluate structures of the iron oxyhalides with the surfaces in lowest energy (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 12). Both materials exhibit an octahedral structure35,36, with an Fe core coordinated with halide and oxygen atoms. The structures were confirmed by X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS, Supplementary Table 3). Both X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES, Supplementary Fig. 13) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS, Supplementary Fig. 14) data also indicate that Fe sites in the FeOF and FeOCl resemble those in Fe2O3, which are octahedrally coordinated. Fourier transform of k2-weighted EXAFS spectra of iron oxyhalides clearly suggested a higher affinity of fluorine toward Fe core than chlorine due to a stronger signal intensity of Fe–F bond (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 15).

While both FeOF and FeOCl have bulk octahedral Fe cores coordinated with halide and oxygen atoms, the shorter Fe–F bonds in FeOF (2.1 Å) relative to the Fe–Cl bonds in FeOCl (2.4 Å) indicate that F atoms are more strongly held, and thus less susceptible to displacement under chemical action. Bader charge analysis (Supplementary Text 4) also reveals that the F atoms in FeOF have a higher charge (0.66 e−) at octahedral Fe sites than those in FeOCl (0.54 e−), corresponding to the greater electronegativity of fluorine than chlorine.

The high efficiency of iron oxyhalides in activating H2O2 originates, in theory, from the high electronegativity of halides to attract and deliver electrons from Fe cores. The catalytic process begins with the substitution of halides by H2O2, followed by a cascade of reactions that generate •OH, with the expectation that the detached halides reoccupy the active sites to complete the redox cycle22 (Fig. 2e). Fluorine, due to its highest electronegativity among all elements (3.98 on the Pauling scale), shows a stronger affinity to reclaim the occupied sites than chlorine. This strong electroactive nature has been applied in other fields, such as making high-performance electrodes or high-energy density batteries37,38.

To support our hypothesis, we conducted simulations involving H2O2 reacting with FeOCl or FeOF: (a) H2O2 substituting halogen atoms, (b) H2O2 filling halide vacancies, and (c) regeneration of halogen sites. The results showed that FeOF exhibits more negative reaction energies in both the halogen substitution (−1.59 eV) and vacancy filling (−1.04 eV) processes, indicating a stronger affinity toward H2O2 and a greater tendency to initiate catalytic reactions compared to FeOCl. Additionally, the lower energy barrier for halogen substitution than vacancy filling suggests that the F sites coordinated with Fe are the dominant active sites in the catalytic process. Moreover, the regeneration of halogen sites is essential for maintaining catalytic continuity and material stability. Our calculation revealed that the energy for F reoccupying a vacant site in FeOF is highly exergonic (−2.74 eV), further demonstrating that the released F ions have a strong tendency to return and restore the catalytic structure. This energetically favorable regeneration explains why the F atoms in FeOF are more preferably retained during reaction (Supplementary Fig. 16).

To validate the proposed reaction pathway involving fluorine release during the interaction of FeOF with H2O2, we calculated the reaction energies for three distinct mechanistic routes: (a) direct conversion of H2O2 to •OH on FeOF without fluorine release, (b) conversion of H2O2 to •OH on FeOF involving F− regeneration and formation of an intermediate •OOH species, and (c) conversion of H2O2 to •OH on FeOF involving F− regeneration without the formation of a •OOH intermediate. As shown in the reaction energy diagram (Supplementary Fig. 17), pathway b exhibits the most favorable energetics, with a significantly exothermic profile across all reaction steps. This result supports our hypothesis that the interim release of F− is critical for the catalysis.

While for catalytic reactions occurring in bulk solution with a high concentration of H2O2 (typically 1–10 mM) involved, the critical F species does not necessarily reclaim the Fe sites before diffusing away or participating in a side reaction. The above results collectively inspired us to implement a promising solution—leveraging the spatial confinement enabled by a membrane structure to facilitate the longevity of the catalytic system.

Spatial confinement with graphene oxide layers

Increasing the concentration of F− in real-world water treatment is impractical, particularly with respect to drinking water treatment39. Furthermore, the low affinity of pristine FeOF for uncoordinated fluorine ions limits its potential for functionalization. Alternatively, our approach focused on confining the two-dimensional FeOF within a suitable matrix to limit fluorine diffusion away from the Fe centers40,41,42,43. Graphene oxide layers, with a theoretical interlayer spacing less than 1 nm44, emerged as a suitable structure to spatially confine alien materials within their highly flexible matrix45,46. The graphene oxide sheets were expected to serve as a structurally flexible confinement matrix, effectively intercalating with the layered FeOF to form confined regions.

Single layer graphene oxide was produced by exfoliating commercial graphene oxide paste under high-energy sonication (Supplementary Text 5). SEM images showed a layered morphology of the exfoliated graphene oxide (Supplementary Fig. 18). The thickness of the exfoliated graphene oxide plus interlayer spacing was measured to be approximately 1.3 nm by atomic force microscopy (AFM), suggesting a typical single layer feature (Supplementary Fig. 19). The thickness of a single graphene oxide layer (excluding the space between graphene oxide and substrate during AFM test) ranges from 0.5 to 0.8 nm47,48, indicating that the interlayer spacing between our exfoliated graphene oxide layers would fall within angstrom-scale range ( < 1 nm) when forming a membrane.

By adjusting addition order and ratio of the FeOF and the single layer graphene oxide, we manufactured three different membranes via vacuum filtration, termed as GO (without FeOF), FeOF/GO (FeOF embedded within the substrate), and FeOF topping (FeOF deposited on top of the substrate) (Fig. 3a). The FeOF content in the FeOF/GO and the FeOF topping membranes was approximately 45.1 wt.% (or 2.5 g FeOF per m2 graphene oxide), as was calculated by weighing mass of the freeze-dried samples and material total digestion. The FeOF content was also determined to be 46.0 wt.% using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, Supplementary Fig. 20).

a Schematic illustration of the membrane synthetic protocol. b Cross-sectional FIB-SEM images of the membranes. After the ion beaming, the FeOF was exhausted to leave voids while graphene oxide layers were slightly melted to form a compact surface, featured as a clean cut. c Cross-sectional SEM and SEM-EDS mapping images of the membranes. After the liquid nitrogen cracking, the FeOF between graphene oxide layers could be preserved and the uneven surface favored the observation of layer-by-layer structure, featured as an uneven cracking. d XRD patterns of the membranes. e 2D/3D AFM images of the membranes, where mica was adopted as the substrate (inset: top-view SEM image showing confined FeOF within graphene oxide matrix).

The inclusion of FeOF resulted in an increased membrane roughness (Rmax = 1394–1420 nm compared to 719 nm, Supplementary Fig. 21). High-energy ion beam imaging via focused ion beam-scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM) was used to profile the space where the FeOF intercalated with the graphene oxide (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 22). The cross-section of the GO membrane showed a smooth and compact morphology, while the FeOF/GO membrane possessed a high density of horizontal voids. When the FeOF dosages were reduced gradually (0.8, 0.5, 0.2, and 0.1 of the original dosage, termed as 0.1FeOF/GO–0.8FeOF/GO), the resultant FeOF/GO membranes exhibited gradually reduced voids density (Supplementary Fig. 23). The results corroborated the horizontal laminate structure of the membrane formed by FeOF and graphene oxide layers. It was implied that water would flow through these horizontal channels in between layers, which promises good contact between reactants and catalysts. Given that the tilting angle was fixed at 52° in all FIB-SEM tests (Supplementary Text 6), the thickness of GO and FeOF/GO membranes could be accurately calculated at 2.597 and 2.662 μm (Supplementary Fig. 24), respectively.

The cross-sectional surface created by the ion beam in FIB-SEM would be a “clean cut” which could revealed the laminate channels. The intercalating morphology was further exposed through the “uneven cracking” in SEM imaging performed after liquid nitrogen-induced cracking of the membranes (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Text 7). The addition of FeOF did not significantly alter the structural integrity, and the two-dimensional FeOF with approximately 45 nm in average thickness was compatibly confined within the graphene oxide matrix.

XRD patterns revealed an angstrom-scale interlayer spacing of 7.89 Å from the GO membrane49 (Fig. 3d), based on Bragg’s law. The original exfoliated graphene oxide layers displayed a weak intensity at this position (zoomed in by 100 times in Supplementary Fig. 25), further corroborating the single layer nature of the exfoliated graphene oxide. After introducing the FeOF, a new characteristic peak at 9.04° emerged while the peak associated with interlayer spacing of graphene oxide weakened. This new peak probably corresponded to the interlayer spacing between the FeOF and graphene oxide layers, calculated to be 9.77 Å. The XRD patterns of the FeOF/GO membranes with reduced FeOF dosages (0.1FeOF/GO–0.8FeOF/GO) exhibited gradually reduced intensity of this peak (Supplementary Fig. 26). For the FeOF topping membrane, where the least contact between the FeOF and graphene oxide layers was involved, the peak at this position still existed but showed the weakest intensity. 3D AFM images further confirmed the angstrom-scale spacing between FeOF and graphene oxide (49.3 nm vs. 50.4 nm, Fig. 3e). In past research, 20 nm was identified as the critical threshold to trigger the spatial confinement effect in H2O2 activation6. The angstrom-scale interlayer spacing ( < 1 nm) between the FeOF and graphene oxide layers favorably meets this requirement, confirming the successful construction of an angstrom-scale reaction vessel for the following heterogeneous Fenton reactions.

Long-lasting catalytic oxidation under angstrom-scale confinement

A flow-through membrane cell was employed to evaluate the applicability of the catalytic membranes (Fig. 4a). The FeOF/GO membrane exhibited greater hydrophobicity compared to the GO membrane in sessile drop experiments, corresponding to an improved water permeability (Fig. 4b). This enhancement is attributed to the inclusion of hydrophobic FeOF surface, which offers less resistance to water molecules when passing through the channels (Supplementary Fig. 27). This effect has been previously reported that the water molecules incline to permeate through a tortuous path primarily along the introduced hydrophobic surfaces rather than the hydrophilic surfaces of graphene oxide50.

a Schematic diagram of the membrane setup. b Hydrophobicity test conducted via contact angle measurement. The first frame after the water droplet reached membranes was used for analysis. c Membrane specific surface area and porosity determined by BET. d Raman spectra for the membranes. e Permeability as a function of pressure. f THI purification and DMPO–OH generation in membrane systems during the first 8 h run ([H2O2] = 10 mM, [THI] = 10 μM, pH = 6.2 ± 0.1, pressure = 2 bar, standard deviations (n = 3) were presented). g Rate constants for THI purification in different membrane systems where standard deviations (n = 3) were presented.

To further understand the angstrom-scale reaction spaces, textural properties of the membranes were determined via N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 28). The inclusion of FeOF slightly influenced the specific surface area of membrane, which was reduced from 7.10 to 6.41 m2 g–1, while it generated a significantly higher density of micropores ( < 2 nm) which was 4.2 times greater than that of original GO membrane (Fig. 4c). The increased micropores were attributed to the higher density of defects generated by the introduced FeOF bending the graphene oxide layers. The defective levels were quantified by Raman spectroscopy, where the FeOF/GO membrane possessed a higher D band (1348 cm–1) to G band (1593 cm–1) ratio (ID/IG) at 1.71, compared with that of the GO membrane at 0.77 (Fig. 4d). The 0.1FeOF/GO–0.8FeOF/GO membranes also exhibited gradually reducing ID/IG values from 1.37 to 0.93, corroborating that the generation of micro-sized defects was caused by the FeOF intercalation (Supplementary Fig. 29). Notably, previous membrane studies often introduced alien materials into membrane substrates to generate defects as a convenient method to increase water flux51,52. This effect was also reflected in the increased water permeability of FeOF/GO membrane. The water flux could be increased to 5.8 LMH bar–1 (Fig. 4e), classifying it as a nanofiltration membrane which typically exhibits a water flux range of 4–10 LMH bar–1. In comparison, the GO membrane displayed a lower water flux of 2.3 LMH bar–1. The permeability decreased to 1.8 LMH bar–1 for FeOF topping membrane due to the blockage of surface channels.

The swelling of graphene oxide layers—primarily induced by water intercalation—can increase the interlayer spacing from approximately 0.8 nm in the dry state to ~1.2–1.4 nm when hydrated53. To investigate the swelling behavior of graphene oxide, we further measured the XRD patterns of pre-wetted GO and FeOF/GO membranes (Supplementary Fig. 30). The results confirm that the peak corresponding to the interlayer spacing of graphene oxide shifted to a lower 2θ angle upon wetting, indicating an increase in spacing from 7.98 Å to 12.1 Å. In contrast, the peak corresponding to the interlayer spacing between FeOF and graphene oxide exhibited only a slight shift, with the spacing increasing from 9.77 Å to 10.1 Å. This smaller change may be attributed to the hydrophobic nature of the FeOF surface, which likely retains fewer water molecules and thereby limits the extent of swelling in the confined channels. Additionally, the applied pressure ( > 2 bar in this study) can effectively mitigate this swelling to some extent54, helping to maintain narrower interlayer spacings and enhance membrane performance in long-term applications.

Volumes of water channels in the membranes were measured by water saturation test (Supplementary Text 8 and Supplementary Fig. 31). The results indicate that the water flow indeed preferentially passed through spaces or channels with lower resistance—those containing hydrophobic FeOF surfaces—despite a reduced volume. The less catalytically effective surfaces composed solely of graphene oxide with rich oxygen functional groups were likely bypassed due to their higher water resistance. This phenomenon promotes higher reactants contact efficiency with the catalytic FeOF surfaces. The retention time of reactants within the GO, FeOF/GO, and FeOF topping membranes at 2 bar was calculated to be 83.3, 18.3, and 106.6 s, respectively. The catalytic performance of membranes was then evaluated in the THI degradation. In contrast to the non-effective GO membrane and the rapidly deactivated FeOF topping membrane, the FeOF/GO membrane consistently achieved nearly 100% degradation efficiency of THI in initial stage (8 h run, Fig. 4f).

To better compare the differences in radical generation efficiency between angstrom-confined and unconfined systems, real-time EPR monitoring was used to measure the generated DMPO–OH concentration over time. It is observed that the generated DMPO–OH signal correlated closely to the THI degradation rate (Fig. 4f) and confirmed the higher radical availability under angstrom-scale confinement. Notably, we observed rapid decay of DMPO–OH signals shortly after its generation, highlighting the persistent challenge of long-term radical identification. We determined an accurate window for radical quantification ( < 3 minutes, Supplementary Fig. 32), which provides a useful reference for future studies. It was acknowledged that EPR is the most powerful technique for probing radical generation in environmental applications28, while more regulations are needed to validate the detection method in different environments.

The degradation data were fitted using a pseudo-first-order model, and the FeOF/GO membrane exhibited kinetics one magnitude faster than the unconfined membrane (0.15 s–1 vs. 0.01 s–1, Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 33). The addition of ethanol (EtOH, k•OH = (1.2–1.8) × 109 M–1 s–1) as •OH scavenger55 almost terminated the catalytic reaction, which aligns with the radical-dominated nature of iron oxyhalides triggered Fenton reaction21.

We further tested the longevity and elemental leaching of the FeOF/GO membrane system during long-term experiments (Fig. 5a). The results indicate that an excellent THI degradation rate over 90% could be maintained for more than 2 weeks. Especially in the first 13 days, a near complete removal of THI was reached. A decline in THI removal rate was observed following a minor leaching of F− ions, possibly indicating a disintegration of membrane structure at this point. The detection of the leached ions was delayed due to the detection limits of the equipment. No obvious leaching of Fe ions was detected ( < 10 ppb), suggesting that the contribution of homogenous Fenton reactions is negligible.

a Degradation of neonicotinoids in long-term continuous-flow experiments ([H₂O₂] = 10 mM, [THI] = 10 μM, pH = 6.2 ± 0.1, pressure = 2 bar, standard deviations (n = 3) were presented). b Comparison of H2O2 activation efficiency in different systems21,29,76,77,78,79. c Reaction mechanisms of the angstrom-confined and unconfined systems.

In particular, the FeOF/GO membrane outperformed all previously reported heterogeneous Fenton systems in H2O2 to •OH conversion rate, achieving 69.8% (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Table 4). Its unprecedented H2O2 to •OH conversion rate still maintained at ca. 65.0% even after 8 h run. Comparatively, the unconfined system lost its efficacy rapidly due to catalyst deactivation. The results suggest the prospect of angstrom-confined system to break through the reactivity-stability compromise, which is one of the greatest challenges encountered for the past reported systems. It was reported that spatial confinement in membrane systems significantly enhances H2O2 activation and pollutant degradation, featured by exceptional catalytic performance5,56. The superior performance of our FeOF/GO membrane further extends this concept by not only enabling efficient catalysis but also achieving remarkable long-term stability (Supplementary Table 5), owing to its ability to retain halogen species within confined catalytic environments.

The mechanisms for the elevated longevity of our angstrom-confined system were proposed as follows: (a) within angstrom-scale spaces ( < 1 nm), F− ions that were initially substituted by H2O2 molecules cannot diffuse away due to the spatial confinement, allowing them to re-coordinate with the Fe core more efficiently, thereby fulfilling a regenerative cycle for prolonged catalysis; (b) the angstrom-scale reaction vessels shield the incorporated FeOF from excessive exposure to reactants, minimizing the chance for H2O2—which is typically present in orders of magnitude higher concentrations than those of micropollutants and F−—to continually occupy the active sites (Fig. 5c).

To substantiate the proposed mechanism, we performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of hydrated fluoride ions interacting with graphene oxide layers. These simulations aimed to mimic the confinement behavior of F− ions released from FeOF within the graphene oxide framework. The results show that, after approximately 3 ps of simulation, the system reaches equilibrium, and the representative F− ion becomes stably confined on the graphene oxide surface. Notably, the F− ion, initially coordinated with four water molecules, undergoes partial dehydration during confinement and exhibits negligible displacement thereafter. This indicates that the graphene oxide layers significantly limit the mobility of F− ions, reducing their likelihood of being carried away by water flow. These findings support our hypothesis that graphene oxide serves as an effective confinement matrix, thereby enhancing the catalytic stability of FeOF (Supplementary Fig. 34).

An additional control group, the FeOF-CNT membrane, was also introduced in which single-walled carbon nanotubes (CNTs) were employed as the support matrix (Supplementary Fig. 35). Unlike graphene oxide, CNT-based membranes possess much larger pores on the micron scale (Supplementary Fig. 36), effectively eliminating the possibility of spatial confinement effects. However, CNT membranes offer an ultrahigh surface area (981.17 m2g–1 for CNT, 850.35 m2g–1 for FeOF/CNT, Supplementary Table 2), which is over 100 times greater than that of GO membranes. Despite this, the FeOF-CNT membrane exhibited poor catalytic durability, with less than 20% degradation efficiency at 2 h (Supplementary Fig. 37).

We also employed XAS to examine the Fe K-edge spectra of FeOF/GO and FeOF/CNT membranes before and after catalytic reactions (Supplementary Table 3). The FeOF/GO membrane exhibited minimal spectral changes after reaction, indicating strong retention of the Fe–F coordination environment (Supplementary Fig. 38). In contrast, the Fe–F bond signal in the FeOF/CNT membrane was significantly weakened following the reaction, suggesting substantial fluorine loss. To further validate this observation, we conducted F− rejection experiments using GO and CNT membranes, which yielded consistent results—GO membranes effectively retained F− ions, whereas CNT membranes failed to do so (Supplementary Fig. 39). Together, these results support the conclusion that the angstrom-scale channels within the graphene oxide membrane effectively preserve the fluorine content, thereby maintaining the structural integrity and catalytic activity of FeOF. In contrast, the non-confining carbon nanotube matrix was unable to prevent F loss, highlighting the superior ability of the GO-based confinement system to prolong the operational stability and longevity of FeOF catalysts.

Long-term performance and NOM rejection

Natural organic matter (NOM) in drinking water source can quench •OH (k•OH/NOM = 109–1010 s−1)57, which reduces or even nullifies the effectiveness of catalytic membranes targeting organic micropollutants58,59. In this context, employing size exclusion to physically reject NOM before it interacts with reactive sites and scavenges radicals presents a practical strategy to mitigate this issue. To evaluate the practical applicability of the FeOF/GO catalytic membrane, we artificially configured contaminated well water containing neonicotinoids (referring to the polluted regions in the US, e.g., Alabama), NOM, and other inorganic constituents (Supplementary Table 6). In addition to THI, two other common neonicotinoids, i.e., clothianidin (CLO) and imidacloprid (IMI), were also included as target pollutants.

The angstrom-scale channels in the membranes achieved exceptional NOM rejection, with over 80% total organic carbon (TOC) removal (Supplementary Fig. 40). The dynamic radius of NOM was measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS), and its effective diameter (n = 10) was determined to be 235.93 nm on average, much larger than those of the neonicotinoids ranged between 0.43–0.46 nm (Supplementary Text 9). Consequently, the FeOF embedded within the angstrom-confined channels could be shielded from the majority of the NOM, allowing exclusive and complete degradations of neonicotinoids. In contrast, unconfined FeOF system was significantly affected by the NOM, with its performance dropping to below 30% for all three pollutants (Supplementary Fig. 40). Notably, the Suwannee River NOM used in this study is inherently complex and polydisperse which might account for the partial rejection60.

During long-term experiments, the FeOF/GO membrane could also last for more than 2 weeks with a complete degradation of neonicotinoids (Fig. 6a). After the 2-week reaction, the spent FeOF in the FeOF/GO was digested, and its fluorine content could be largely preserved (53.8% vs. 55.6% of the fresh FeOF). The operational pressure was gradually elevated to overcome the increasing resistance induced by NOM fouling, corresponding to a deceasing water permeability over time (Supplementary Fig. 41). A significant reduction of membrane performance was observed when the pressure reached 5 bar, possibly ascribed to the membrane cracking. Accordingly, it is expected that the contaminated water entered the membrane through those micro-scale defects, which excluded most of the NOM. Then, the remaining molecules could primarily pass through the horizontal channels containing FeOF following tortuous pathways before transitioning to the next layer (Fig. 6b). Combined with the size exclusion effect, this flow pattern ensured effective contact between reactants and the catalytic FeOF surfaces, leading to a durable and selective removal of neonicotinoids that can be highly promising in practical groundwater treatment.

Discussion

This study addresses the challenge of balancing catalytic reactivity and stability in heterogeneous Fenton systems, particularly in the context of catalytic membranes. By leveraging the concept of spatial confinement, we demonstrated that the integration of FeOF within angstrom-scale graphene oxide channels (9.77 Å) could offer a practical and effective solution to this challenge. Our findings revealed that spatial confinement not only enhanced the catalytic efficiency of FeOF by improving reactant-catalyst interactions but also significantly mitigated catalyst deactivation by restricting the loss of critical species—F− ions. This dual benefit enabled the system to maintain high pollutant degradation efficiency ( ~ 100%) over extended periods in 2 weeks, even under complex water matrices containing NOM. The angstrom-confined catalytic membrane design could be adapted to other catalytic oxidation systems beyond neonicotinoid degradation, offering a scalable and cost-effective approach for water treatment. Nonetheless, challenges such as scalability of membrane fabrication, preservation of membrane from fouling and cracking, and optimization for diverse pollutants still afford space for further investigation. Future research is advised to explore the interplay between confinement dimensions and catalyst performance, as well as develop advanced characterization methods to further elucidate the mechanisms underlying spatially confined catalysis. The principles established here could pave the way for next-generation catalytic membranes achieving both efficiency and durability.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

Chemicals used for synthesizing materials included iron(III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O, reagent grade, ≥ 98.0%), methyl alcohol (MeOH, CH3OH, HPLC grade, ≥ 99.9%), graphene oxide (non-exfoliated paste, C ≥ 5.0%), carbon nanotubes ( ≥ 90% carbon basis, ≥ 80% as carbon nanotubes, 1–2 nm diameter) from Sigma-Aldrige (USA) and iron(III) fluoride trihydrate (FeF3·3H2O, reagent grade, 98.0%) from ThermoFisher Scientific (USA). Other critical chemicals involved in polluted water preparation and analytical experiments incorporated thiamethoxam (THI, C8H10ClN5O3S, PESTANAL®, analytical standard), imidacloprid (IMI, C9H10ClN5O2, PESTANAL®, analytical standard), clothianidin (CLO, C6H8ClN5O2S, PESTANAL®, analytical standard), ethyl alcohol (MeOH, CH3CH2OH, ACS grade, ≥ 99.5%), 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO, C6H11NO, GC grade, ≥ 98.0%), etc., from Sigma-Aldrige (USA). The Suwannee River NOM was purchased from the International Humic Substances Society (USA). Unless otherwise specified, all the chemicals were used as received without further purification.

Synthesis of iron oxyhalides

FeOCl was synthesized following a commonly reported method: 5 g of FeCl3·6H2O powder was placed in an aluminum oxide crucible and transferred into a tubular furnace. Then, it was heated to 220 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min–1 and annealing for 2 h to obtain the final product21. Synthesis of layer-structured FeOF was modified from a reported wet-chemical method61: 33.4 mg of FeF3·3H2O was added into 16 mL of methanol in a 20 mL Teflon reactor. The mixture was sonicated for 5 min before the vessel was sealed and transferred into a 200 °C mechanical convection oven (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). The reaction lasted for 24 h and then allowed to cool down under ambient conditions. The as-prepared orangish powder was washed with pure ethanol and milli-Q water for three times, respectively. Then, it was frozen in the lab fridge at −20 °C and freeze-dried in a 2.5 L benchtop freeze dryer (Labconco, USA) at −84 °C overnight. The obtained FeOCl and FeOF were stored in a desiccator before use. It is noted that the previously reported FeOF synthesized in 1-isopropanol medium would result in an irregular rod-like structure61 (Supplementary Fig. 42), which hindered its compatibility to be further assembled into the graphene oxide membrane (Supplementary Fig. 43).

Synthesis of catalytic membranes

FeOF suspension was obtained by dispersing a certain amount of FeOF powder in 50 mL Milli-Q water and probe-sonicating for 30 s under 30% amplitude. The mixture was put still to precipitate for a certain time to extract the supernatant. Then, 10 mL of the supernatant was taken to mix with 1 mL of the single-layered GO suspension (ca. 6 mg mL–1) and diluted to a final volume of 100 mL (Supplementary Fig. 44). FeOF supernatant (10 mL) was also frozen and then underwent freeze drying to measure the actual weight of the colloidal FeOF. The diluted mixture was sonicated for 5 min before it was transferred to a 250 mL vacuum filtration system (Glasscolabs, USA) powered by a water-circulating pump (Vevor, USA), and passed through a polyethersulfone membrane (PES, 0.45 μM, Sterlitech, USA). The separated membrane was air-dried and termed as FeOF/GO. Control membrane with the same amount of FeOF was fabricated by adding the FeOF suspension after the graphene oxide suspension had formed a membrane, termed as FeOF topping. Membrane consisting only of graphene oxide was also synthesized and named with GO. To further investigate the effect of spatial confinement on the catalytic reaction, single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) were also employed as a membrane matrix without confinement effect to fabricate catalytic membranes following the same procedure. The resulting membranes, with and without FeOF incorporation, were referred to as FeOF/CNT and CNT, respectively.

Characterizations and analyses

Morphologies of powders and membranes were examined with a scanning electron microscopy (SEM, SU8230 UHR Cold Field Emission, Hitachi) coupled with a BRUKER XFlash 5060FQ annular energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) detector. The high-resolution morphology of FeOF was obtained using transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Tecnai Osiris 200 kV, FEI) with a high-angle annular dark-field scanning mode (HAADF). X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku SmartLab, Japan) equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.542 Å) was employed to characterize crystalline phases and d-spacing of materials. The elemental information was investigated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) with a Versa Probe II scanning XPS microprobe (Physical Electronics, USA) using monochromatic Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV). X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) spectra were collected using a Beamline 8-ID (ISS) of the National Synchrotron Light Source II (Brookhaven National Laboratory, USA), with a Si (111) double crystal mono-chromator and a passivated implanted planar silicon detector. The data were collected at room temperature with energy calibrated by the Fe foil, and Demeter XAS analysis software was used to process the collected data. The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms at −196.15 °C were obtained by ASAP 2000 (Micromeritics, USA), from which specific surface area was obtained by a multipoint Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) model and porosity information was calculated based on Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method. Apart from the liquid nitrogen cracking for cross-sectional SEM analysis, Focused Ion Beam-Scanning Electron Microscopy (FIB-SEM, ThermoFisher Helios G4 UX DualBeam for Materials Science, USA) was also used to observe the profiles of channels to illustrate the water flow pattern. Water contact angle test was performed by the sessile drop method using a contact angle goniometer (OneAttension, Biolin Scientific, Finland). Total organic carbon (TOC) concentration was measured by a Shimadzu TOC analyzer using non-purgeable organic carbon (NPOC) mode in calculating the NOM exclusion. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) analyses were conducted with the ESR5000 spectrometer (Bruker, Germany) using DMPO as the spin-trapping agent for capturing •OH. The activation efficiency was quantified by processing the generated signals relative to the standard DMPO–OH signal using ESRStudio Version 1.90.0062 (Bruker, Germany). The batch extracts and membrane permeate samples were analyzed using an Agilent high-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC, Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity), equipped with a C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm) and a diode array detector (DAD). UV wavelength was set at 269 nm, while mobile phase was composed by of (a) 15%, 0.1% formic Acid and (b) 85%, acetonitrile with a flow rate of 1.0 mL L–1.

The d-spacing was calculated using Bragg’s law:

Where n is an integer, \({{{\rm{\lambda }}}}\) is the wavelength of the X-ray (nm), \({{{\rm{\theta }}}}\) is the incident angle (°), and d is the spacing between the diffraction planes (nm).

The water flux and NOM exclusion were calculated by:

Where V is the volume of permeated liquid (L), A is the membrane surface area (m2), t is the retention time (h), and C0 and Ci are the TOC values of NOM (mg L−1) in the feeding solution and effluent, respectively.

The retention time of reactants in membrane was calculated by:

Where porosity (Vp, μL) is the volume of the pores in the membrane and flow rate (Q, μL s–1) is the rate at which water flows through the membrane.

Determination of pseudo-first reaction rate constant in membrane study by:

Where Ct and C0 are indicative of the concentration of reactant at a certain time (t) or initial concentration, respectively. k is the first-order reaction rate (t–1).

Neonicotinoids degradation

Performance of powder catalysts in H2O2-based heterogenous catalysis for neonicotinoid removal was conducted in batch experiments. Specifically, a certain amount of powder sample was dispersed in 50 mL solution containing selected neonicotinoids at desired concentrations. Then, 10 mM of H2O2 was added to initiate the reaction, and an aliquot of samples was collected at a certain time interval. The performance of membranes for H2O2 activation and neonicotinoids degradation was tested in a dead-end continuous-flow system (transmembrane pressure: 2–5 bar; upper limit pressure: 5.5 bar). The feed solution was prepared by dissolving a certain amount of H2O2 and neonicotinoids and stored in a pressurized tank. The pressure was adjusted using ultrapure N2 gas to maintain a desired water flux. In both batch and flow-through experiments, initial pH of reaction solution was set at 6.2 ± 0.1 (circumneutral pH relevant to well waters in the US) and no buffer was added to avoid interference, if not otherwise specified.

XAS data analysis

Data reduction, data analysis, and EXAFS fitting were performed and analyzed with the Athena and Artemis programs of the Demeter data analysis packages63 that utilizes the FEFF6 program64 to fit the EXAFS data. The energy calibration of the sample was conducted through a standard Fe foil, which as a reference was simultaneously measured. A linear function was subtracted from the pre-edge region, then the edge jump was normalized using Athena software. The χ(k) data were isolated by subtracting a smooth, third-order polynomial approximating the absorption background of an isolated atom. The k3-weighted χ(k) data were Fourier transformed after applying a Hanning window function (Δk = 1.0). For EXAFS modeling. The global amplitude EXAFS (CN, R, σ2 and ΔE0) was obtained by nonlinear fitting, with least-squares refinement, of the EXAFS equation to the Fourier-transformed data in R-space, using Artemis software, EXAFS of the Fe foil is fitted and the obtained amplitude reduction factor S02 value (0.71) was set in the EXAFS analysis to determine the coordination numbers (CNs) in the Fe-O/F/Cl scattering paths in the sample. For Wavelet Transform analysis, the χ(k) exported from Athena was imported into the Hama Fortran code. The parameters were listed as follow: R range, 1.0–6.0 Å, k range, 0–12 Å−1; k weight, 3; and Morlet function with κ = 15, σ = 1 was used as the mother wavelet to provide the overall distribution. Data points in figures were presented with mean value plus its standard deviation.

Computational details

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP)65,66. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functional with a Hubbard correction (PBE + U) was employed because the GGA functional alone does not adequately describe the strong correlation between Fe-d electrons67,68. A U-value of 4.0 eV was used for Fe taken from previous studies and obtained by fitting to experimental iron oxide formation energies27,69. All calculations were conducted with spin polarization, and Fe ions were initialized in a high-spin ferromagnetic ordering per previous DFT studies on iron oxyfluorides27,70. Projector-augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials were used to eliminate the computational costs associated with calculating nonparticipating core electrons71,72. PAWs explicitly described the O 2 s and 2p, F 2 s and 2p, and for Fe, 4 s and 3 d electrons.

The FeOF surface was represented by slabs in a 2 × 2 × 1 supercell of repeated primitive cells with the (110) facet exposed, while the FeOCl surface was represented by slabs in a 3 × 3 × 1 supercell of repeated primitive cells with the (010) facet exposed. At least >20 Å vacuum space was used in the direction normal to the surface to separate surfaces and avoid interactions between periodic images. Only the minimum energy surfaces were analyzed. All structure relaxations and surface energy calculations utilized a 500 eV plane-wave cutoff energy. Calculations were conducted using a Γ-point centered 2 × 2 × 1 Monkhorst–Pack k-point mesh, as increasing beyond this size did not significantly improve surface energies (only 0.1 meV/A2 difference). Slab structures were relaxed until total energies between two ionic steps were less than 0.001 eV. Crystal structure representations were obtained using VESTA73.

Multiple multi-step reaction pathways for the conversion of H2O2 to •OH radicals on the FeOF surface were calculated using a 4-layered FeOF slab model to determine the minimum energy pathway using the same computational parameters as the surface relaxation. Several surface configurations of reactants and products for each reaction step were calculated, and only the lowest-energy structures were used for the calculation of reaction energetics as follows

Where \({\Delta {{{\rm{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{rxn}}}}}\) is the reaction energy for a given reaction step, \({{{{\rm{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{products}}}}}\) is the energy of the reaction products for that step, \({{{{\rm{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{reactants}}}}}\) is the total energy of the reactants for the given step. Additionally, the binding energy of a hydrated fluoride ion was also calculated by first performing molecular dynamics of a hexahydro fluoride ion to determine its first hydration shell (consisting of four water molecules). The tetrahydro fluoride was subsequently bound to a functionalized graphene oxide sheet, and the binding energy was calculated as follows

Where \({\Delta {{{\rm{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{bind}}}}}\) is the binding energy of the tetrahydro fluoride, \({{{{\rm{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{GO}}}}*{{{{\rm{F}}}}}^{-}\cdot 4{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{2}{{{\rm{O}}}}}\) is the total energy of the GO*F- · 4H2O complex, \({{{{\rm{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{GO}}}}}\) is the total energy of the graphene oxide sheet, and \({{{{\rm{E}}}}}_{{{{{\rm{F}}}}}^{-}\cdot 4{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{2}{{{\rm{O}}}}}\) is the total energy of the hydrated fluoride ion. The graphene oxide sheet was modeled as a finite molecular fragment with hydroxyl and epoxy groups, and the hydrated fluoride complex was initially positioned above the sheet. An orthorhombic simulation cell with dimensions a = 30 Å, b = 30 Å, and c = 35 Å, with > 36 Å vacuum spacing in all directions, was used to eliminate periodic image interactions.

Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations were performed to examine the thermal stability and interfacial dynamics of the GO*F- · 4H2O complex. The simulations were conducted in the canonical (NVT) ensemble using a Langevin thermostat with friction coefficients of 1 ps−1 for GO carbon and oxygen atoms, 2 ps−1 for GO hydrogen atoms, 2 ps−1 for water oxygen atoms, 5 ps−1 for water hydrogen atoms, and 0 ps−1 for the fluoride ion. A time step of 1 fs was used, and the trajectory was propagated for 3 ps following geometry optimization. The system was equilibrated at 300 K for 2.3 ps before ramping to 400 K. AIMD Calculations employed a plane-wave energy cutoff of 350 eV and Γ-point-only Brillouin zone sampling. Dispersion forces were included using DFT-D3 corrections to capture hydrogen bonding and long-range interactions. Trajectory analysis was performed using the Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE)74. Visualizations were generated with OVITO to assess hydration shell integrity, interfacial binding modes, and thermal fluctuations.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper (ref. 75).

References

Wei, H., Loeb, S. K., Halas, N. J. & Kim, J.-H. Plasmon-enabled degradation of organic micropollutants in water by visible-light illumination of Janus gold nanorods. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 15473–15481 (2020).

Schwarzenbach, R. P. et al. The Challenge of Micropollutants in Aquatic Systems. Science 313, 1072–1077 (2006).

Lee, J., von Gunten, U. & Kim, J.-H. Persulfate-based advanced oxidation: Critical assessment of opportunities and roadblocks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 3064–3081 (2020).

Hodges, B. C., Cates, E. L. & Kim, J.-H. Challenges and prospects of advanced oxidation water treatment processes using catalytic nanomaterials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 642–650 (2018).

Meng, C. et al. Angstrom-confined catalytic water purification within Co-TiOx laminar membrane nanochannels. Nat. Commun. 13, 4010 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Mechanism of Heterogeneous Fenton Reaction Kinetics Enhancement under Nanoscale Spatial Confinement. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 10868–10875 (2020).

Wu, X. et al. Single-Atom Cobalt Incorporated in a 2D Graphene Oxide Membrane for Catalytic Pollutant Degradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 1341–1351 (2022).

Ma, H. et al. MOF derivative functionalized titanium-based catalytic membrane for efficient sulfamethoxazole removal via peroxymonosulfate activation. J. Membr. Sci. 661, 120924 (2022).

Jiang, Y. et al. In situ turning defects of exfoliated Ti3C2 MXene into Fenton-like catalytic active sites. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 120, e2210211120 (2023).

Gupta, S. S. et al. Rapid Total Destruction of Chlorophenols by Activated Hydrogen Peroxide. Science 296, 326–328 (2002).

Lyu, L., Yan, D., Yu, G., Cao, W. & Hu, C. Efficient Destruction of Pollutants in Water by a Dual-Reaction-Center Fenton-like Process over Carbon Nitride Compounds-Complexed Cu(II)-CuAlO2. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 4294–4304 (2018).

Duan, X., Sun, H. & Wang, S. Metal-Free Carbocatalysis in Advanced Oxidation Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 678–687 (2018).

Duan, X., Sun, H., Shao, Z. & Wang, S. Nonradical reactions in environmental remediation processes: Uncertainty and challenges. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 224, 973–982 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. Core-shell catalysts for the elimination of organic contaminants in aqueous solution: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 455, 140604 (2023).

Wang, Y., Zhong, M., Ma, F., Wang, C. & Lu, X. Shell-induced enhancement of Fenton-like catalytic performance towards advanced oxidation processes: Concept, mechanism, and properties. Water Res. 268, 122655 (2025).

Zhang, Z.-Q. et al. Nano-island-encapsulated cobalt single-atom catalysts for breaking activity-stability trade-off in Fenton-like reactions. Nat. Commun. 16, 115 (2025).

Wang, L., Cao, M., Ai, Z. & Zhang, L. Dramatically Enhanced Aerobic Atrazine Degradation with Fe@Fe2O3 Core–Shell Nanowires by Tetrapolyphosphate. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 3354–3362 (2014).

Zhang, Y.-J. & Yu, H.-Q. Mineralization or Polymerization: That Is the Question. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 11205–11208 (2024).

Zhang, Y.-J. et al. Metal oxyhalide-based heterogeneous catalytic water purification with ultralow H2O2 consumption. Nat. Water 2, 770–781 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Which Micropollutants in Water Environments Deserve More Attention Globally?. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 13–29 (2022).

Sun, M. et al. Reinventing Fenton Chemistry: Iron Oxychloride Nanosheet for pH-Insensitive H2O2 Activation. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 5, 186–191 (2018).

Zhang, S. et al. Membrane-Confined Iron Oxychloride Nanocatalysts for Highly Efficient Heterogeneous Fenton Water Treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 9266–9275 (2021).

Chen, Y., Miller, C. J., Collins, R. N. & Waite, T. D. Key Considerations When Assessing Novel Fenton Catalysts: Iron Oxychloride (FeOCl) as a Case Study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 13317–13325 (2021).

Chen, H. et al. Real roles of FeOCl nanosheets in Fenton process. Environ. Sci.: Nano 10, 3414–3422 (2023).

Xu, X. et al. Identifying the Role of Surface Hydroxyl on FeOCl in Bridging Electron Transfer toward Efficient Persulfate Activation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 12922–12930 (2023).

Yang, X. -j, Xu, X. -m, Xu, J. & Han, Y. -f Iron Oxychloride (FeOCl): An Efficient Fenton-Like Catalyst for Producing Hydroxyl Radicals in Degradation of Organic Contaminants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16058–16061 (2013).

Chevrier, V. L., Hautier, G., Ong, S. P., Doe, R. E. & Ceder, G. First-principles study of iron oxyfluorides and lithiation of FeOF. Phys. Rev. B 87, 094118 (2013).

Wu, J.-H. & Yu, H.-Q. Confronting the Mysteries of Oxidative Reactive Species in Advanced Oxidation Processes: An Elephant in the Room. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 18496–18507 (2024).

Yu, D. et al. Electronic structure modulation of iron sites with fluorine coordination enables ultra-effective H2O2 activation. Nat. Commun. 15, 2241 (2024).

Schmidt, T. S. et al. Ecological consequences of neonicotinoid mixtures in streams. Sci. Adv. 8, eabj8182 (2022).

Hladik, M. L. et al. Year-round presence of neonicotinoid insecticides in tributaries to the Great Lakes, USA. Environ. Pollut. 235, 1022–1029 (2018).

Liu, S., Lazarcik, J. & Wei, H. Emerging investigator series: quantitative insights into the relationship between the concentrations and SERS intensities of neonicotinoids in water. Environ. Sci.: Nano 11, 3294–3300 (2024).

Ji, Q., Bi, L., Zhang, J., Cao, H. & Zhao, X. S. The role of oxygen vacancies of ABO3 perovskite oxides in the oxygen reduction reaction. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 1408–1428 (2020).

Duan, X., Sun, H., Tade, M. & Wang, S. Metal-free activation of persulfate by cubic mesoporous carbons for catalytic oxidation via radical and nonradical processes. Catal. Today 307, 140–146 (2018).

Chappert, J. & Portier, J. Effet Mössbauer Dans FeOF. Solid State Commun. 4, 185–188 (1966).

Zeng, Y. et al. 2D FeOCl: A Highly In-Plane Anisotropic Antiferromagnetic Semiconductor Synthesized via Temperature-Oscillation Chemical Vapor Transport. Adv. Mater. 34, 2108847 (2022).

Gocheva, I. D., Tanaka, I., Doi, T., Okada, S. & Yamaki, J. -i A new iron oxyfluoride cathode active material for Li-ion battery, Fe2OF4. Electrochem. Commun. 11, 1583–1585 (2009).

Liu, Y. et al. Reversible Iron Oxyfluoride (FeOF)-Graphene Composites as Sustainable Cathodes for High Energy Density Lithium Batteries. Small 19, 2206947 (2023).

Deshmukh, A., Wadaskar, P. & Malpe, D. Fluorine in environment: A review. Gondwana Geol. Mag. 9, 1–20 (1995).

Wu, Z. et al. Pivotal roles of N-doped carbon shell and hollow structure in nanoreactor with spatial confined Co species in peroxymonosulfate activation: Obstructing metal leaching and enhancing catalytic stability. J. Hazard. Mater. 427, 128204 (2022).

Zeng, T., Zhang, X., Wang, S., Niu, H. & Cai, Y. Spatial Confinement of a Co3O4 Catalyst in Hollow Metal–Organic Frameworks as a Nanoreactor for Improved Degradation of Organic Pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 2350–2357 (2015).

Su, P. et al. Nanoscale confinement in carbon nanotubes encapsulated zero-valent iron for phenolics degradation by heterogeneous Fenton: Spatial effect and structure–activity relationship. Sep. Purif. Technol. 276, 119232 (2021).

Liu, L. & Corma, A. Confining isolated atoms and clusters in crystalline porous materials for catalysis. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 244–263 (2021).

Zheng, S., Tu, Q., Urban, J. J., Li, S. & Mi, B. Swelling of Graphene Oxide Membranes in Aqueous Solution: Characterization of Interlayer Spacing and Insight into Water Transport Mechanisms. ACS Nano 11, 6440–6450 (2017).

Hu, M. & Mi, B. Enabling Graphene Oxide Nanosheets as Water Separation Membranes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 3715–3723 (2013).

Mi, B. Graphene Oxide Membranes for Ionic and Molecular Sieving. Science 343, 740–742 (2014).

Akhavan, O. The effect of heat treatment on formation of graphene thin films from graphene oxide nanosheets. Carbon 48, 509–519 (2010).

Schniepp, H. C. et al. Functionalized Single Graphene Sheets Derived from Splitting Graphite Oxide. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 8535–8539 (2006).

Li, Z. et al. Tuning the interlayer spacing of graphene laminate films for efficient pore utilization towards compact capacitive energy storage. Nat. Energy 5, 160–168 (2020).

Boukhvalov, D. W., Katsnelson, M. I. & Son, Y.-W. Origin of Anomalous Water Permeation through Graphene Oxide Membrane. Nano Lett. 13, 3930–3935 (2013).

Zhang, W.-H. et al. Graphene oxide membranes with stable porous structure for ultrafast water transport. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 337–343 (2021).

Ritt, C. L., Werber, J. R., Deshmukh, A. & Elimelech, M. Monte Carlo Simulations of Framework Defects in Layered Two-Dimensional Nanomaterial Desalination Membranes: Implications for Permeability and Selectivity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 6214–6224 (2019).

Nair, R. R., Wu, H. A., Jayaram, P. N., Grigorieva, I. V. & Geim, A. K. Unimpeded Permeation of Water Through Helium-Leak–Tight Graphene-Based Membranes. Science 335, 442–444 (2012).

Li, W., Wu, W. & Li, Z. Controlling Interlayer Spacing of Graphene Oxide Membranes by External Pressure Regulation. ACS Nano 12, 9309–9317 (2018).

Wan, Z. et al. Sustainable remediation with an electroactive biochar system: mechanisms and perspectives. Green. Chem. 22, 2688–2711 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Nanoconfinement-triggered oligomerization pathway for efficient removal of phenolic pollutants via a Fenton-like reaction. Nat. Commun. 15, 917 (2024).

Lindsey, M. E. & Tarr, M. A. Inhibition of Hydroxyl Radical Reaction with Aromatics by Dissolved Natural Organic Matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34, 444–449 (2000).

Brame, J., Long, M., Li, Q. & Alvarez, P. Inhibitory effect of natural organic matter or other background constituents on photocatalytic advanced oxidation processes: Mechanistic model development and validation. Water Res. 84, 362–371 (2015).

Long, M. et al. Phosphate Changes Effect of Humic Acids on TiO2 Photocatalysis: From Inhibition to Mitigation of Electron–Hole Recombination. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 514–521 (2017).

Nghiem, L. D., Schäfer, A. I. & Elimelech, M. Removal of Natural Hormones by Nanofiltration Membranes: Measurement, Modeling, and Mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38, 1888–1896 (2004).

Zhu, J. & Deng, D. Wet-Chemical Synthesis of Phase-Pure FeOF Nanorods as High-Capacity Cathodes for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 3079–3083 (2015).

Zimmermann, R. Quantitative spin determination by EPR spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. (1969) 49, 425–430 (1982).

Ravel, B. & Newville, M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537–541 (2005).

Zabinsky, S., Rehr, J., Ankudinov, A., Albers, R. & Eller, M. Multiple-scattering calculations of X-ray-absorption spectra. Phys. Rev. B 52, 2995 (1995).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Computational Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Hubbard, J. & Flowers, B. H. Electron correlations in narrow energy bands. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 276, 238–257 (1997).

Wang, L., Maxisch, T. & Ceder, G. Oxidation energies of transition metal oxides within the ${\mathrm{GGA}}+{\mathrm{U}}$ framework. Phys. Rev. B 73, 195107 (2006).

Doe, R. E., Persson, K. A., Meng, Y. S. & Ceder, G. First-Principles Investigation of the Li−Fe−F Phase Diagram and Equilibrium and Nonequilibrium Conversion Reactions of Iron Fluorides with Lithium. Chem. Mater. 20, 5274–5283 (2008).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Hjorth Larsen, A. The atomic simulation environment—a Python library for working with atoms. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 273002 (2017).

Wan, Z. et al. Overcoming the Reactivity-Stability Challenge in Water Treatment Catalyst through Spatial Confinement Data sets. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m6089.figshare.30017887 (2025).

Yin, Y., Lv, R., Li, X., Lv, L. & Zhang, W. Exploring the mechanism of ZrO2 structure features on H2O2 activation in Zr–Fe bimetallic catalyst. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 299, 120685 (2021).

Huang, Q.-Q., Liu, H.-Z., Huang, M., Wang, J. & Yu, H.-Q. Ligand-assisted heterogeneous catalytic H2O2 activation for pollutant degradation: The trade-off between coordination site passivation and adjacent site activation. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 330, 122592 (2023).

Sun, H., Xie, G., He, D. & Zhang, L. Ascorbic acid promoted magnetite Fenton degradation of alachlor: Mechanistic insights and kinetic modeling. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 267, 118383 (2020).

Ling, C. et al. Atomic-Layered Cu5 Nanoclusters on FeS2 with Dual Catalytic Sites for Efficient and Selective H2O2 Activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200670 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the EPA STAR project, Integrated Portable Raman and Electrochemical NanoSystem (I-PRENS) for Neonicotinoid Detection and Remediation in Rural Drinking Water Supplies (No. R840599). Support from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health (No. P42ES033815) is also acknowledged. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors made use of the electron microscopy facility of Aberration-Corrected Electron Microscopy (ACEM) Core with support from the Provost Office of Yale University. The authors thank Yale Institute for Nanoscience and Quantum Engineering (YINQE) and Yale Mechanical and Thermal Analysis Instrumentation Core (MTAIC) for the technical assistance. We also thank Monong Wang and Yuanzhe Liang for the advice on characterizing the swelling of hydrated graphene oxide membrane.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W., S.H.C., and J.-H.K. conceived of the idea. J.-H.K., supervised the project. H.W., and D.W. co-hosted the project. Z.W. fabricated the membranes and designed the experiments. Z.W. and S.H.C. performed the membrane tests and analyzed the results. C.M. provided the DFT simulation resource. A.F.M., O.N., L.A., K.L.Y., X.M., and S.L. contributed to XPS, DFT, XAS, BET, neonicotinoids analysis, etc. Z.W. and J.-H.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Fu Liu, Piao Xu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wan, Z., Chae, S.H., Meese, A.F. et al. Overcoming the reactivity-stability challenge in water treatment catalyst through spatial confinement. Nat Commun 16, 9672 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64684-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64684-5