Abstract

Grain boundaries (GBs) serve as fast diffusion paths for dopant atoms, and the segregated dopants can significantly alter the materials’ properties. However, the exact mechanism of fast dopant diffusion along the GBs, particularly at atomic scale, is still unclear. Here we show direct observation of preferential GB diffusion of Hf dopant atoms along the Σ31 symmetric tilt GB in α-Al2O3, using time-resolved atomic-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy and statistical tracking of Hf atom locations. Molecular dynamics simulations incorporating artificial neural network interatomic potentials reveal that Hf atoms preferentially diffuse along the GB by exchanging with co-segregated Al vacancies at the GB. Moreover, we demonstrate that GB interstitial diffusion can greatly enhance the diffusivity of Hf atoms along the GB, where shuffle motion plays a key role in lowering the activation energies for GB diffusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Impurity doping is a major strategy for controlling the physical and chemical properties in a wide variety of materials1,2,3. Metals and ceramics are often used in polycrystalline form, which contain numerous grain boundaries (GBs, the interface between crystallites), and the doped impurities typically enrich at the GBs as a result of preferential diffusion along the GBs. Such fast GB diffusion significantly impacts the polycrystalline materials’ properties, including grain growth, GB migration, recrystallization, sintering, and high-temperature plastic deformation3,4,5,6,7. So far, the GB diffusion has been characterized by macroscopic measurements of concentration profiles along the GBs using tracer atoms, or isotopes8. While these studies have demonstrated that GBs serve as fast diffusion paths for dopants, the precise atomistic origins and atomic-scale diffusion paths at GBs remain unclear due to the absence of direct observation of dopant dynamics. Moreover, atomic-scale theoretical calculations of dopant dynamics at GBs have been limited, because the calculations require large supercells and long timescale computations. Previous theoretical studies have used molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with empirical interatomic potentials, but they often fail to predict the atomic structures and energetics of GBs, compared to the density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Therefore, a new approach is needed to deeply understand the dopant dynamics at GBs. Here, we directly observe the diffusion dynamics of Hf dopant atoms at the α-Al2O3 Σ31 [0001]/\((47\bar{11}0)\) GB using time-resolved atomic-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM), and we successfully tracked single Hf atom diffusion along the GB. To track the Hf diffusion process at the atomic level, we used a 300 kV electron probe, which can provide sufficient energy to overcome the diffusion barrier without knocking out Hf atoms (maximum energy transfer is 4.8 eV, see Supplementary Note 1). Therefore, we can directly observe Hf diffusion dynamics even at room temperature without damaging the sample9. Furthermore, we performed large-scale MD simulations of Hf atom diffusion at the GB using an artificial neural network (ANN) interatomic potential trained on massive DFT calculations, which allows us to evaluate Hf atom diffusion dynamics and their energetics with DFT accuracy10,11,12. On the basis of our synergetic experimental and theoretical investigations, we elucidate that Hf atom diffusion along the GB is accelerated by two distinct mechanisms: vacancy exchange with co-segregated Al vacancies and GB interstitial diffusion, which has not been realized before. In the GB interstitial diffusion, the activation energy is significantly reduced to 0.5 eV with the aid of shuffle motion through the GB interstitial sites.

Results

Hf atom diffusion along the α-Al2O3 Σ31 GB

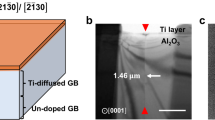

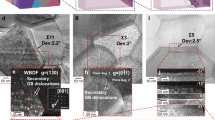

So far, time-resolved annular dark-field (ADF) STEM imaging have been used to directly observe dopant diffusion in the bulk, twin boundary, and on the surface7,9,13. Figure 1a shows an atomic-resolution ADF STEM image of the Hf-doped Σ31 α-Al2O3 GB viewed along the [0001] direction, where time-sequentially acquired 50 frames (total acquisition time: 85 sec.) were averaged (See Supplementary Movie 1). Owing to the Z-contrast nature of ADF STEM (Z is the atomic number)14, the Al atomic column is brighter than the O atomic column in the bulk region (ZO = 8, ZAl = 13), as indicated by the overlaid structural model in upper left of Fig. 1a. To compensate the mis-tilt between two grains, a periodic array of specific structure is formed along the GB, which is known as structural unit8. The structural unit comprises four white polygons: a seven-membered ring A7, an elongated seven-membered ring B7, and two six-membered rings C6 and D6. As indicated by the white arrowheads in Fig. 1a, we observed significant bright dot contrasts within the structural units, suggesting that Hf atoms segregate at the GB core (ZHf = 72). Figure 1a is the full-frame averaged ADF STEM image, so the brighter contrasts indicate that Hf atoms have remained longer at these sites. To track the Hf diffusions at the GB, we construct a maximum intensity map (Fig. 1b), where a maximum value is selected from all frames for each pixel (see Methods)13. Even if a single Hf atom remains at a specific site for only one frame, Hf locations should appear as bright contrasts in the maximum intensity map. The bright Z-contrasts are well localized in the GB, and the Hf atoms are mainly located at the Al atomic columns of the structural unit, suggesting that the Hf atoms are in the form of substituting Al atomic columns in the GB core. However, as marked by the white arrowheads in the two rectangle areas in Fig. 1b, the Hf atoms are also located between the Al atomic columns, and we will refer to these locations as the interstitial sites in the GB. The selected frames are shown in Fig. 1c–h, and we found two representative Hf diffusion processes: (i) Hf atomic jumps between Al sites at the GB (Fig. 1c–e) and (ii) Hf atomic jumps between or through interstitial sites at the GB (Fig. 1f – h, see Methods). The interstitial diffusion generally requires high activation energy in the bulk, making it an unusual process in α-Al2O3 bulk. Therefore, the observed interstitial diffusion could contribute to the diffusion only along the GB. We note that a 300 kV electron beam was used for atomic-scale observations, which can provide sufficient energy to promote dopant diffusion9. Figure 2a shows all the Hf locations projected in a structural unit (4963 red circles). We tracked all the Hf atoms frame by frame for five datasets of time-resolved ADF STEM images, and the total number of the tracked structural units is 3120 frames. Using Gibbsian excess, the Hf concentration at the GB is estimated to be 0.25 ± 0.02 atom nm–2 (See Methods). Most of the Hf atoms are observed at the Al atomic sites in the GB core, and the statistical counts for each atomic site are given in Fig. 2b. As expected from the maximum intensity map of Fig. 1b, 97% of Hf atoms are observed within the structural units, and the remaining 3% of Hf atoms are also in the first neighbors to the structural units. The most frequently observed GB site for Hf atoms is the center of the ring A7, which is consistent with the time-averaged image of Fig. 1a. The other sites of the ring A7 also have relatively high occupancy of Hf atoms. Although the rings C6 and D6 also have the center atomic sites, the occupancies of Hf atoms are much lower than that in the center of the ring A7. In addition to the Al atomic sites, we also found a small proportion of Hf atoms at the GB interstitial sites, as marked by diamond in Fig. 2b. These GB interstitial sites are confined in the ring B7 and the right side of the ring A7.

a Time-averaged atomic-resolution ADF STEM image of the Hf-doped Σ31 GB. The left black and white arrowheads indicate the location of the GB core and the segregated Hf dopants, respectively. The structural unit is overlaid by white polygons. b The maximum intensity map obtained from the time-resolved ADF STEM images, where the bright contrast corresponds to the temporal locations of the Hf dopants. The white arrowheads in the two rectangle regions indicate the locations of Hf dopants at the GB interstitial sites. c–e, f–h The selected two series of Hf diffusion processes in the structural unit, where the same Hf dopants are indicated by the numbered white arrowheads. The scale bar in (a) is 5 Å, and (b) share the same scale. The scale bar in (c) is 3 Å, and (d–h) share the same scale.

a All the Hf locations (red circles) projected in a structural unit obtained from time-resolved ADF STEM data sets. b The distribution of Hf occupation at Al sites (circles) and interstitial sites (squares) in the GB. c, d The counts of Hf atom jumps between Al columns (circles) or through GB interstitial sites (squares), respectively. The total acquisition time of images is 799 seconds (470 frames), corresponding to the total number of the tracked structural units of 3120. The scale bar in (a) is 3 Å. Source data are provided with this paper.

In this experiment, the temporal resolution is limited to 1.7 seconds, so we cannot directly observe the activation process of Hf atomic jumps, which may occur in the picosecond order. However, we can track atomic jumps by calculating the difference of Z-contrast intensity between two consecutive frames. When a Hf atom moves from site α to site β, site α appears darker, and site β appears brighter in the difference image (see Methods). Using a series of difference images, we counted the number of Hf atomic jumps, and the categorized Hf diffusion counts (i) between Al sites and (ii) between or through interstitial sites in the GB are summarized in Fig. 2c, d, respectively. Since most Hf atoms are localized in the center of ring A7, we observed numerous Hf jumps within A7 ring, particularly between Al sites in the GB (Fig. 2c). Similar Hf jumps between Al sites were also observed in C6 and D6 rings. In contrast, Hf jumps associated with interstitial sites (indicated by gray squares in Fig. 2d) are localized in the B7 ring and the right side of the A7 ring, suggesting that a specific interstitial mechanism governs GB diffusion in these regions.

Hf diffusion paths and their energetics

To understand the origin of the preferential Hf diffusion along the Σ31 GB, we performed theoretical calculations. First, we constructed the atomic structure of pristine Σ31 GB using the γ-surface method with DFT calculations. However, the obtained structure models are inconsistent with the experiment. This is because the relaxed GB structures are strongly dependent on the initial atomic configurations, which can easily be trapped in local minimum structures15,16,17,18,19. Moreover, DFT calculation requires massive computational resources, which limits the exploration of the large configuration space. To globally explore the configuration space for the Σ31 GB structure, we conducted a simulated annealing calculation11,18 using DFT-trained ANN interatomic potentials11, which can significantly reduce the computational cost but maintain computational accuracy. Figure 3a shows the most stable structure of the Σ31 pristine GB superimposed on the ADF STEM image of the Hf-doped Σ31 GB. The theoretical structural model is in excellent agreement with the experiment. The GB energy of the structure (2.04 J m–2) is significantly lower than that in the previous report3 (3.93 J m–2) and close to the recent result12 (2.07 J m–2) (see Methods and Supplementary Note 2). Although the Hf dopants segregate at the Σ31 GB, the structural unit remains unchanged from the pristine structure, and therefore the Hf dopants segregate in the form of Al substitutional defects3. Since the valence state of Hf4+ is different from Al3+, it is essential to theoretically investigate stable Hf defects and other charge compensating defects. Figure 3b shows the defect formation energies of the Hf dopants and native defects in the α-Al2O3 bulk as a function of the Fermi level in the oxygen-rich limit evaluated using density functional theory calculation20 (see Methods). The Fermi level in the thermal equilibrium is given by the vertical line (3.42 eV). To denote the point defects, we use the Kröger-Vink notation21. For example, when Hf4+ substitute Al3+, it is denoted as \({{{\rm{H}}}}{{{{\rm{f}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Al}}}}}^{1+}\) (or \({{{\rm{H}}}}{{{{\rm{f}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Al}}}}}^{\cdot }\)), where 1+ indicates the effective charged state of the point defect. We consider six types of point defects: Al substitutional (HfAl), O substitutional (HfO), Al vacancy (VAl), O vacancy (VO), the complex of residing HfAl and Al vacancy ([HfAl⋅VAl]), and the complex of residing HfAl and VO ([HfAl⋅VO])22. In the bulk, Hf is in the form of HfAl1+ (Hf4+) and the defect charge is compensated by VAl3– at the Fermi level (dashed line in Fig. 3b). However, the defect formation energies of the most stable HfAl1+ and VAl3– are considerably high (2.1 eV). Therefore, these defects could co-segregate to the GB core, and the charge neutrality can be achieved locally23. To evaluate the stability of point defects in the GB, we calculated the defect formation energies of HfAl1+ and VAl3– for all the Al sites in the GB core (395 sites). Figure 3c shows the defect formation energies of HfAl1+ and VAl3– as a function of the projected distance from the GB core. When the projected distance from the GB core is more than 5 Å, the formation energies of HfAl1+ and VAl3– are close to those in the bulk. While in the GB core, most of defect formation energies are much lower than those in the bulk, suggesting that HfAl1+ and VAl3– defects should preferentially segregate to the GB core. Figure 3d, e show the site dependence of the defect formation energies for HfAl1+ and VAl3–, respectively. The defect formation energy of HfAl1+ is significantly reduced in rings A7 and B7. According to the quantitative evaluation of coordination environment at each atomic site, the Al-Al coordination numbers in the rings A7 and B7 are reduced, and thus, the free volumes are consequently increased, which strongly contributes to the lowering of the defect formation energies in the GB core (See Supplementary Fig. 1). On the other hand, the coordination environment in the rings C6 and D6 is nearly identical to that in the bulk, and therefore the defect formation energies in the rings C6 and D6 are similar to those in the bulk. On the basis of thorough theoretical calculations, we elucidate that HfAl1+ and VAl3– defects simultaneously segregate to the GB core, and the charge compensation should be achieved in the GB core. The accumulated VAl3– are localized within the GB core, which significantly increases the encounter probability between Hf atoms and VAl. Therefore, the Hf atom could preferentially diffuse along the GB via vacancy-related mechanism.

a The energetically most stable atomic structure of pristine Σ31 GB overlaid on the ADF STEM image viewed along the [0001] axis. b The defect formation energies of Hf dopants in the bulk as a function of Fermi level under the oxygen-rich limit. The vertical black line indicates the Fermi level at thermal equilibrium at 300 K, where the numbers in (b) correspond to the charged states of point defects. c The defect formation energies of \({{{\rm{H}}}}{{{{\rm{f}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Al}}}}}^{1+}\) and \({V}_{{{{\rm{Al}}}}}^{3-}\) in Σ31 GB as a function of the projected distance from the GB core. d, e The site dependence of the defect formation energies of \({{{\rm{H}}}}{{{{\rm{f}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Al}}}}}^{1+}\) and \({V}_{{{{\rm{Al}}}}}^{3-}\), respectively. The scale bar in (a) is 3 Å. Source data are provided with this paper.

GB interstitial diffusion of Hf atoms

Time-resolved ADF STEM images in Fig. 1c–h show two different types of Hf diffusion processes in the GB: Hf atomic jumps (i) between Al sites and (ii) via GB interstitial sites. Our defect formation energy calculations reveal that \({{{\rm{H}}}}{{{{\rm{f}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Al}}}}}^{1+}\) and \({V}_{{{{\rm{Al}}}}}^{3-}\) charged defects co-segregate in the GB, which could induce vacancy-exchange diffusion between Al sites. To investigate the GB diffusion mechanism of Hf atoms, we performed nudged elastic band (NEB) calculations24, where we explored minimum energy paths and evaluated their activation energies for Hf diffusion in the GB. To thoroughly explore the Hf diffusion paths in the GB, we employed the following two approaches: (i) the brute-force search of the vacancy exchange diffusion between two adjacent Al sites, and (ii) the extraction of diffusion paths from high-temperature MD calculations (see Methods). Figure 4a shows the calculated Hf atom trajectories in Σ31 GB using the NEB method, and the stronger red and blue curves represent the more stable trajectories (smaller activation energies). Since the activation energy of Hf atom diffusion in the bulk is 2.0 eV (see Supplementary Fig. 2), we excluded the Hf trajectories with activation energies exceeding 2.0 eV in Fig. 4a. The red curves represent the Hf trajectories between Al sites, corresponding to the vacancy exchange diffusion. In the majority of the GB region, the activation energies of these red curves are significantly lower than those in the bulk (average: 1.37 eV), indicating vacancy exchange diffusion is preferential in the GB. However, in the ring B7, the activation energy via the vacancy exchange mechanism is relatively high, suggesting that the other diffusion mechanism is active. The blue curves in Fig. 4a represent the Hf trajectories through GB interstitial sites, which are localized in the ring B7 and the right half of ring A7, as marked by white triangles in Fig. 4a. In this diffusion process, multiple Al atoms and Al vacancies are involved in, and we discuss the diffusion behavior of two representative cases (see Supplementary Movie 2, 3): (i) Hf diffusion between Al sites via a GB interstitial site (Fig. 4d: a7 → i2 → a6), and (ii) Hf diffusion between interstitial sites via an Al site in the GB (Fig. 4e: b2 → a6 → i2). Figure 4b shows the energy surface of Hf diffusion as a function of Hf displacement, with snapshots of Al and Hf trajectories given in Fig. 4d. The Hf diffusion is achieved by the following four steps: (I) when the Al at a3 site is vacant, the Hf atom at a7 site moves into the GB interstitial site i2, and the a7 site becomes vacant (Hf: a7 → i2), (II) the Al atom at a1 site moves into the a7 site (Al: a1 → a7), and the Al atom at a2 site moves into i1 site (Al: a2 → i1), (III) the Hf neighbor Al atom at b2 site moves into the vacant a3 site (Al: b2→ a3), and the vacancy is formed at b2 site, and (IV) the Hf atom at i2 site move into a6 site (Hf: i2→ a6). Processes I and IV in Fig. 4b correspond to the Hf atom diffusion, and these activation energies are ~1 eV, which are much lower than those in the vacancy exchange mechanism. Figure 4c, e show the second case of the energy surface and diffusion path for the Hf GB interstitial diffusion, respectively: (I) initially, the Al atom is at i1 site, and the neighbor a1 site is vacant, and the Hf atom at b2 site moves into a6 site (Hf: b2 → a6), (II) the Al atom at a7 site moves into the vacant site a1, and the a7 site becomes vacant (Al: a7 → a1), (III) the Hf atom and the Al atom at a5 site show slight relaxation, and (IV) the Hf atom at a6 site moves into i2 site (Hf: a6 → i2). In this case, Hf atom diffusion corresponds to processes I and IV, and the activation energies have considerably low value of 0.5 eV. Unlike typical interstitial diffusion, the present Hf atom diffusion goes through the GB lattice sites in processes II and III, and then Hf atom moves into the other GB interstitial site.

a The red and blue curves represent the minimum energy paths for Hf dopants at the Σ31 GB, where red and blue curves correspond to the paths between Al sites and through GB interstitial sites, respectively. The white arrowheads indicate the GB interstitial sites. b, c Two selected activation energy surfaces of the Hf transitions as a function of Hf displacement, which are related to the GB interstitial diffusion process. The light-blue points correspond to the local minimum energies. d, e The corresponding Hf trajectories for (b, c) respectively, where the dark/light-blue, red, and green circles represent Al, O, and Hf atoms. The light-blue circles indicate Al atoms with large displacements. The dashed circles indicate the location of Al vacancies. Source data are provided with this paper.

Discussion

On the basis of the STEM observations and theoretical calculations, we elucidate that two distinct Hf diffusion mechanisms occurred at the GB: (i) the vacancy exchange mechanism, and (ii) the GB diffusion via interstitial sites. As shown in Fig. 4a, most of the GB diffusion is achieved by the vacancy exchange mechanism, where the local atomic structures are close to that of the bulk. However, at the C7 and the right half of A7 rings, the local structure is significantly distorted from the bulk, and the Hf atom diffusion becomes complex, i.e. the Hf atoms diffuse through the GB interstitial sites accompanied by multiple Al atom diffusion. Compared with the vacancy exchange mechanism, the GB interstitial diffusion can significantly reduce the activation energy, and we discuss why the specific GB interstitial sites are used for the Hf diffusion, as indicated by white arrowheads in Fig. 4a. Figure 5 shows the dichromatic pattern of the Σ31 GB orientation, which is useful for the geometric description of the general GB atomic structures8. The red and blue circles represent the lattices (Al atomic columns) in the perfect crystal of the upper and lower grains, respectively. The light red and blue circles represent the extended lattices to the other side of the grain, and the black circles represent the coincident site lattice, where the lattices of both grains coincide. Except for the minor structural reconstruction, the red and blue lattices agreed with the observed Al atomic columns in the Σ31 GB in Fig. 3a. Therefore, the majority of the observed GB diffusion between the GB lattices in the rings A7, C6 and D6 can be considered as bulk-like vacancy exchange mechanism. In the ring B7, however, Hf atoms often diffuse through the GB interstitial sites. The observed GB interstitial sites matched the extended lattices in the structural unit well, as indicated by the white arrowheads in Fig. 5. The distances between the lattices and extended lattices are much shorter than the nearest-neighbor lattice spacing, and the movement between the lattices and extend lattices is known as shuffle motion. As shown in Fig. 2b, the observed Hf atoms at the GB interstitial sites are in the rings A7 and B7, and the observed GB interstitial sites match the extended lattices in Fig. 5 well, suggesting that the shuffle motion is the key to GB interstitial diffusion. According to the theoretical calculations, the Al-Al and Al-O coordination numbers and their Voronoi volumes in the rings A7 (right half) and B7 are largely deviated from that of the bulk (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Therefore, the activation energy for Hf diffusion in the rings A7 (right half) and B7 becomes larger by vacancy exchange mechanism. However, using shuffle motion, Hf atoms can diffuse through the GB interstitial sites, and the activation energies are remarkably reduced, which makes the diffusion along the GBs faster.

The red and blue circles represent the lattices (Al sites) in the perfect crystals of upper and lower grains, respectively, and the black sites represent the CSL sites. The smaller circles with light colors represent the extended lattices to the other side of the grains. The white triangles indicate the GB interstitial sites, and the black arrows represent the displacements between the lattice and the interstitial sites, corresponding shuffle motion. The black arrowhead indicates the location of the GB core.

In summary, we demonstrated that Hf atoms preferentially diffuse along the α-Al2O3 Σ31 GB, using time-resolved atomic-resolution ADF STEM imaging. MD simulations with ANN interatomic potentials revealed that charged defects of HfAl1+ and VAl3– co-segregate to the GB to maintain charge neutrality. This co-segregation significantly increases the encounter rate between Hf atoms and Al vacancies, facilitating Hf diffusion along the GB via vacancy exchange mechanism, particularly at A7 (left half), C6 and D6 rings. While in the distorted A7 (right half) and B7 rings, Hf atoms diffuse through the GB interstitial sites via the shuffle motion, and the GB interstitial diffusion mechanism becomes dominant. Even in general GBs, there always exists the extended lattices at GBs, and therefore, the shuffle motion should assist GB interstitial diffusion, and the GBs act as fast diffusion paths. The present findings suggest that charged dopants at GBs tend to co-segregate with counter-balancing defects, such as vacancies, and that their diffusivity is enhanced through the GB interstitial diffusion mechanism. This behavior may be exploited to design novel materials exhibiting improved physical properties–such as fast ionic conductivity, electronic transport, and thermal conductivity–which are typically degraded by the presence of GBs.

Methods

Sample preparation and electron microscopy

The Hf-doped Σ31(\(47\bar{11}0\))/[0001] α-Al2O3 bicrystal was fabricated by thermal diffusion bonding of two single crystals (Shinkosha Co Ltd.) with Hf deposited on one surface using chemical vapor deposition. The sample was annealed at 1773 K for 10 h in air. The electron-transparent thin specimen for STEM observation was prepared by mechanical polishing and Ar ion milling (10–15 nm thick). Time-resolved ADF STEM images were acquired by ARM300CF (JEOL Ltd.) installed in the University of Tokyo, equipped with a cold field-emission gun and Delta-type corrector. The illumination semi-angle is 30 mrad, operated at 300 kV, and the probe current was typically less than 10 pA. The collection semi-angle for ADF detector was 64 to 200 mrad. The Hf atom diffusions were observed in 5 different regions of the specimen. The dwell time was 6 µs/pix for a wide field of view (256 × 1024 pix), and the total acquisition time ranges between 85 to 204 s (50–120 frames). We note that most of the impurity levels in the α-Al2O3 single crystals are less than 1 ppm, and the highest impurity of Si is less than 10 ppm. Although we performed energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis at the GB, we did not detect such impurities at the GB, which is compatible with our previous pristine Σ13 and Σ31 α-Al2O3 GBs23,25.

The quantification of Hf concentration at the GB

We estimate the Gibbsian excess of Hf at the GB by counting the number of Hf atoms from experimental ADF STEM images with the aid of systematic image simulations. The Gibbsian excess of Hf is defined as ΓHf = (nHf – VGB\({\rho }_{{Hf}}^{{bulk}}\)) / S, where nHf is the total number of Hf atoms in the GB, VGB is the total volume of the GB, \({\rho }_{{Hf}}^{{bulk}}\) is the concentration of Hf in the α-Al2O3 bulk, and S is the GB area. Assuming that \({\rho }_{{Hf}}^{{bulk}}\) is zero, the Gibbsian excess can be simplified to ΓHf = nHf / S. The frame averaged number of Hf atoms (nHf) is experimentally measured to be 15.5 ± 1.8 atoms. The GB area S can be calculated as the product of the GB length and the depth. When a single Hf atom is located at the deep depth, it could be difficult to observe in ADF STEM image. Therefore, we performed multislice image simulations of a single Hf atom in α-Al2O3 Σ31 GB with different depth locations at the center of the ring A726. We used a 300 kV electron probe, an illumination semi-angle of 30 mrad and an ADF detector spanning from 64 to 200 mrad. The specimen thickness was set to 13.2 nm, comprising 40 Al atoms along the column. Supplementary Fig. 3a–c show the simulated ADF STEM images with a single Hf atom at the depth of 0 nm, 5.9 nm, and the pristine, respectively. As the depth location of the Hf atom increases, the maximum intensity decreases. Supplementary Fig. 3d shows the integrated intensity of the column with a single Hf as a function of the depth from the entrance surface. At 6 nm depth, the integrated intensity at the Hf containing atomic column is close to that of the pristine, suggesting that one cannot observe Hf atoms located deeper than 6 nm. Using 6 nm for the depth length, the Gibbsian excess of Hf is estimated to be 0.21 ± 0.02 atoms nm–2.

STEM image analysis

The specimen drifts in the time-resolved ADF STEM images were corrected by a cross-correlation algorithm27. To accurately track the Hf atom positions, we removed the quantum noise of the time-resolved ADF STEM images by total third-degree variation filter (see Supplementary Movie 1(a))28. Hereafter, the intensity of pixel (x, y) at frame i is denoted as I(x, y, i). The time-averaged map \({I}_{{{{\rm{ave}}}}}(x,{y})\) was constructed by averaging over all frames: \({I}_{{{{\rm{ave}}}}}\left(x,{y}\right)=1/{N}_{{frames}}{\sum }_{i}I(x,y,i)\), where Nframes is the total number of the frames. The maximum intensity map \({I}_{\max }(x,{y})\) was constructed by taking the maximum intensity over all frames: \({I}_{\max }\left(x,{y}\right)={ma}{x}_{i}I(x,y,i)\)13. To clearly visualize the Hf atom positions, the time-averaged map was subtracted from the original time-resolved ADF STEM images, by which the background Al/O intensities are removed and the Hf atom positions can be visualized as bright spots (see Supplementary Movie 1(b)). The number of Hf atom jumps was counted by taking the difference between two consecutive frames: Idiff (x, y, i) = I(x, y, i + 1) – I(x, y, i). In the difference image, when a Hf atom moves from site A to site B, the pair of bright and dark contrasts appear, which can be assigned as the Hf atom diffusion.

Hf interstitials at the GB

To determine the elemental type of the interstitial atom in Fig. 1f, we performed ADF STEM image simulations. Supplementary Fig. 5a shows the experimental ADF STEM image of α-Al2O3 Σ31 GB, where an interstitial atomic site is marked with the white arrowhead. Supplementary Fig. 5b–d show the simulated ADF STEM images of the pristine GB, Al interstitial, and Hf interstitial, respectively. Note that the depth location of the Al interstitial is set at the entrance surface to maximize the contrast, while the depth of the Hf interstitial is set at 25.0 Å beneath the entrance surface. While the intensity of the single Al interstitial (Z = 13) is considerably weak, the single Hf interstitial (Z = 72) exhibits a bright contrast comparable to the experimental image. Therefore, the interstitial atom in Fig. 1f should be a Hf atom.

Hf occupancy at the center and lower left sites of ring A7

To estimate the Hf occupancy at each Al column in the center and lower left of ring A7, we performed ADF STEM image simulations. Supplementary Fig. 6a (Fig. 1a) shows the time-averaged experimental ADF STEM image of the Hf-doped α-Al2O3 GB. There are six structural units (SUs), as indicated by the white heptagons. Note that the Hf occupancies of the other Al columns are significantly low, because the Hf dopants move around as single atoms. Since it is difficult to consider all the configuration of Hf locations along the depth, we used structure models with Hf partial occupations in the projection29. Supplementary Fig. 6b–d show the simulated ADF STEM images of the pristine GB, the GB with 35% Hf occupancy at the center of the ring A7, and the GB with 15% Hf occupancy at the lower left site of the ring A7, respectively. Owing to the Z-contrast nature of ADF STEM, even a small fraction of Hf shows much brighter contrast than the other columns, which are comparable to the experimental image. Supplementary Fig. 6e and f show the respective simulated and the experimental line profiles along the line AB in Supplementary Fig. 6c, where the intensities are normalized by the integrated intensity of the pure Al columns. Supplementary Fig. 6g and h show the simulated and experimental line profiles, respectively, along the line CD in Supplementary Fig. 6d. To estimate the Hf occupancy, we fitted the integrated intensities of the simulated Hf containing atomic column with a power function30 as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6i and j for the Hf at the center and at the lower left, respectively. The plots indicate the integrated intensities in the experiment, and the estimated Hf occupancies are summarized in the Supplementary Table 1.

The construction of ANN interatomic potential

We have used the ANN Al-O-Hf interatomic potential created by Yokoi et al.11. The potential has two hidden layers each with 78 nodes. The atomic environments are described by 36 two-body and 120 three-body symmetry functions with a cutoff radius of 5 Å. The training dataset includes 39715 structures consisting of single crystals and various GBs. The mean absolute errors in the total energies and atomic forces between the DFT and ANN calculations are 3.92 meV atom-1 and 79.8 meV Å–1, respectively. The mean difference in the energies of the pristine Σ31 GBs between DFT and ANN is <EDFT – EANN > = 0.038 ± 0.013 J m-2.

Theoretical calculation

The point defect formation energies in the bulk were calculated using the projector augmented wave method implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP 5.4.4)31,32. The defect formation energy of a point defect D with a charged state q is defined as20

where \({E}_{{tot}}\left[{D}^{q}\right]\) is the total energy of the supercell with a defect Dq, ni and μi are the number of the element i in the supercell and the chemical potential, respectively. q and \({\epsilon }_{f}\) are the charged state and the Fermi level of the system, respectively. In the bulk, we used the 2 × 2 × 2 supercell (80 atoms) with a cutoff energy of 500 eV and a k-point mesh of 2 × 2 × 2. For accurate evaluation of energies, hybrid functional HSE33 and supercell correction with extended FNV scheme were employed34,35. The Fermi level of the system is determined using the charge neutrality condition20: \({\sum }_{D,q}q{c}_{D,q}+{c}_{h}-{c}_{e}=0\), where cD,q is the concentration of a point defect D with a charged state q, ch is the concentration of holes, and ce is the concentration of electrons, respectively. GB energies, defect formation energies in GB, GB segregation energies, and activation energies were evaluated using the ANN interatomic potential11. Our GB models contain two identical GBs to compensate for the boundary condition. To remove the interaction between these GBs, the distance between GBs was set to 16.90 Å. In the simulated annealing calculations, 250 independent calculations were performed to thoroughly search for the configurational space. First, 250 initial random structures were generated by heating the GB core (7.0 Å width) at 20,000 K and the structure were extracted every 0.5 ps. Each structure was cooled from 3000 K to 0 K with the cooling rate of 10 K/ps. Since there are no symmetric constraints in our calculations, the two GBs can become inequivalent after annealing. Therefore, two GBs were extracted from the supercell and new supercells with identical two GBs were generated. Following the structural relaxation, GB energies of the relaxed structures were evaluated, which is defined as

where \({E}_{{tot}}^{{GB}}\) and A are the total energy of the supercell containing two GBs and the GB area, respectively. The defect formation energy of \({D}^{q}\) in the GB is evaluated by the sum of the defect formation energy in the bulk \({E}_{f}[{D}^{q}]\) and the segregation energy at site i \({E}_{{seg}}[i,\,{D}^{q}]\):

The segregation energy is defined as the difference of the defect formation energy between at GB site i and in bulk:

where it can be approximated as the difference in total energy of supercell with a defect at GB and in the bulk.

Estimation of the thickness of the surface-strained region

In thin TEM specimens, surface strain may affect the diffusivity mechanism. To estimate the width of the surface-strained region, we relaxed the structure of a 10.2 nm thick α-Al2O3 (0001) surface slab using the ANN potential11. Supplementary Fig. 9 shows the bond length between Al atoms and their nearest-neighbor O atoms as a function of the distance from the surface. Near the surface, the bond length deviates from the bulk value (1.86 Å) as indicated by the dashed line. As the distance from the surface increases, the deviation decreases and converges to the bulk value at a depth of more than 1 nm. Given the 10–15 nm thickness of our TEM specimen, most of the observed Hf jumps are unaffected by surface strain effect.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The codes used for the calculation using the artificial neural network interatomic potential are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Mishin, Y., Asta, M. & Li, J. Atomistic modeling of interfaces and their impact on microstructure and properties. Acta Mater. 58, 1117–1151 (2010).

Sato, Y. et al. Role of Pr segregation in acceptor-state formation at ZnO grain boundaries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 106802 (2006).

Buban, J. P. et al. Grain boundary strengthening in alumina by rare earth impurities. Science 311, 212–216 (2006).

He, C. et al. Nanocrystalline copper for direct copper-to-copper bonding with improved cross-interface formation at low thermal budget. Nat. Commun. 15, 7095 (2024).

Li, D. et al. Low-oxygen rare earth steels. Nat. Mater. 21, 1137–1143 (2022).

Alekseeva, S. et al. Grain-growth mediated hydrogen sorption kinetics and compensation effect in single Pd nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 12, 5427 (2021).

Schweizer, P. et al. Atomic scale volume and grain boundary diffusion elucidated by in situ STEM. Nat. Commun. 14, 7601 (2023).

Sutton, A. P. & Balluffi, R. W. Interfaces in Crystalline Materials. Oxford (Oxford, 1995).

Ishikawa, R. et al. Direct observation of dopant atom diffusion in a bulk semiconductor crystal enhanced by a large size mismatch. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 155501 (2014).

Behler, J. & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146401 (2007).

Yokoi, T., Hamajima, A., Ogura, Y. & Matsunaga, K. Grain boundary segregation of Y and Hf dopants in α-Al2O3: A Monte Carlo simulation with artificial-neural-network potential and density-functional-theory calculation. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 131, 751–761 (2023).

Yokoi, T. et al. Atomic and electronic structure of grain boundaries in α-Al2O3: A combination of machine learning, first-principles calculation and electron microscopy. Scr. Mater. 229, 115368 (2023).

Ishikawa, R. et al. Real-time tracking of three-dimensional atomic dynamics of Pt trimer on TiO2 (110). Sci. Adv. 10, eadk6501 (2024).

Pennycook, S. J. & Boatner, L. A. Chemically sensitive structure-imaging with a scanning transmission electron microscope. Nature 336, 565–567 (1988).

Meiners, T., Frolov, T., Rudd, R. E., Dehm, G. & Liebscher, C. H. Observations of grain-boundary phase transformations in an elemental metal. Nature 579, 375–378 (2020).

Seki, T. et al. Incommensurate grain-boundary atomic structure. Nat. Commun. 14, 7806 (2023).

Chen, E., Heo, T. W., Wood, B. C., Asta, M. & Frolov, T. Grand canonically optimized grain boundary phases in hexagonal close-packed titanium. Nat. Commun. 15, 7049 (2024).

Guhl, H. et al. Structural and electronic properties of Σ7 grain boundaries in α-Al2O3. Acta Mater. 99, 16–28 (2015).

Devulapalli, V., Chen, E., Brink, T., Frolov, T. & Liebscher, C. H. Topological grain boundary segregation transitions. Science 386, 420–424 (2024).

Freysoldt, C. et al. First-principles calculations for point defects in solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 253–305 (2014).

Kim, S., Hood, S. N., Park, J. S., Whalley, L. D. & Walsh, A. Quick-start guide for first-principles modelling of point defects in crystalline materials. J. Phys. Energy 2, 036001 (2020).

Futazuka, T., Ishikawa, R., Shibata, N. & Ikuhara, Y. First-principles calculations of group IIA and group IV impurities in α-Al2O3. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 073602 (2020).

Futazuka, T., Ishikawa, R., Shibata, N. & Ikuhara, Y. Grain boundary structural transformation induced by co-segregation of aliovalent dopants. Nat. Commun. 13, 5299 (2022).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Wei, J. et al. Direct measurement of electronic band structures at oxide grain boundaries. Nano Lett. 20, 2530–2536 (2020).

Madsen, J. & Susi, T. The abTEM code: transmission electron microscopy from first principles. Open Res. Eur. 1, 24 (2021).

Ishikawa, R., Lupini, A. R., Findlay, S. D. & Pennycook, S. J. Quantitative annular dark field electron microscopy using single electron signals. Microsc. Microanal. 20, 99–110 (2014).

Kawahara, K., Ishikawa, R., Sasano, S., Shibata, N. & Ikuhara, Y. Total third-degree variation for noise reduction in atomic-resolution STEM images. Microscopy 74, 1–9 (2024).

Kirkland, E. J. et al. Advanced Computing in Electron Microscopy. (Springer Cham, 2020).

Pennycook, S. J. & Jesson, D. E. High-resolution incoherent imaging of crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 938–941 (1990).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal-amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207–8215 (2003).

Freysoldt, C., Neugebauer, J. & Van de Walle, C. G. Fully Ab initio finite-size corrections for charged-defect supercell calculations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 016402 (2009).

Kumagai, Y. & Oba, F. Electrostatics-based finite-size corrections for first-principles point defect calculations. Phys. Rev. B 89, 195205 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by KAKENHI JSPS (Grant No. 19H05785 to K.M., JP19H05788 to N.S., JP22H04960 to Y.I., JP23K04381 to T.Y., JP24H00373 to R.I.), JST-ERATO (Grant No. JPMJER2202 to N.S.), and JST-FOREST (Grant No. JPMJFR2033 to R.I.). A part of this work was supported by the Advanced Research Infrastructure for Materials and Nanotechnology Japan (Grant No. JPMXP1222UT246) by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). T.F. was supported as a JSPS Research Fellow (Grant No. JP22J15213). T.Y. acknowledges the support from the Naito Science & Engineering Foundation. The calculations were performed using the computers at Information Technology Center, The University of Tokyo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.F. performed calculations, data analysis, and wrote the paper. R.I. designed and directed the study, performed electron microscopy experiments, and wrote the paper. T.Y and K.M. contributed to the construction of the ANN interatomic potential and discussions. N.S. and Y.I. directed the study and contributed to the discussions and suggestions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Futazuka, T., Ishikawa, R., Yokoi, T. et al. Direct observation of substitutional and interstitial dopant diffusion in oxide grain boundary. Nat Commun 16, 9043 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64798-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64798-w