Abstract

Calcineurin, the Ca2+/calmodulin-activated protein phosphatase, recognizes substrates and regulators via short linear motifs, PxIxIT and LxVP, which dock to distinct sites on calcineurin to determine enzyme distribution and catalysis, respectively. Calcimembrin/C16orf74 (CLMB), an intrinsically disordered microprotein whose expression correlates with poor cancer outcomes, targets calcineurin to membranes where it may promote oncogenesis by shaping calcineurin signaling. We show that CLMB associates with membranes via lipidation, i.e., N-myristoylation and reversible S-acylation. Furthermore, CLMB contains an unusual composite ‘LxVPxIxIT’ motif, that binds the PxIxIT-docking site on calcineurin with extraordinarily high affinity when phosphorylated, 33LDVPDIIITPP(p)T44. Calcineurin dephosphorylates CLMB to decrease this affinity, but Thr44 is protected from dephosphorylation when PxIxIT-bound. We propose that CLMB is dephosphorylated in multimeric complexes, where one PxIxIT-bound CLMB recruits calcineurin to membranes, allowing a second CLMB to engage via its LxVP motif to be dephosphorylated. In vivo and in vitro data, including nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analyses of CLMB-calcineurin complexes, support this model. Thus, CLMB with its composite motif imposes distinct properties to calcineurin signaling at membranes including sensitivity to CLMB:calcineurin ratios, CLMB phosphorylation and dynamic S-acylation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Calcium (Ca2+) ions are spatially and temporally controlled in cells to regulate a wide array of biological processes1. Ca2+ signaling frequently occurs within membrane-associated microdomains that contain both effector proteins and their substrates. Thus, subcellular localization of calcineurin, the only Ca2+-calmodulin (CaM) regulated serine/threonine protein phosphatase, dictates its signaling specificity2. Calcineurin (CNA/B) is an obligate heterodimer composed of catalytic (CNA) and regulatory (CNB) subunits that is activated when Ca2+/calmodulin binding relieves autoinhibition mediated by the CNA C-terminal domain3. Calcineurin interacts with partners via two short linear motifs (SLiMs), LxVP and PxIxIT, which cooperate to promote dephosphorylation. PxIxIT binds to CNA independent of Ca2+and anchors calcineurin to substrates and regulators. In contrast, LxVP binds to a site composed of residues in both CNA and CNB and orients substrates for dephosphorylation at a separate catalytic site, marked by Zn2+ and Fe2+ ions2,3. LxVP binding occurs only after activation by Ca2+/CaM and is blocked by autoinhibitory sequences in CNA as well as the immunosuppressant drugs, Cyclosporin A and FK5064,5.

Systematic discovery of PxIxIT and LxVP SLiMs has significantly expanded our knowledge of calcineurin signaling6,7,8,9 and surprisingly identified at least 31 human proteins that harbor composite calcineurin-binding motifs containing contiguous LxVP and PxIxIT sequences that share a proline (LxVPxIxIT)9. Although each SLiM in this composite motif can bind to its cognate site, they are unlikely to do so simultaneously, as their docking surfaces are ~60 Å apart on calcineurin4,9. Thus, how or if these motifs promote dephosphorylation is unclear.

Here we elucidate how C16orf74, a short unstructured microprotein associated with poor outcomes in melanoma, pancreatic and head and neck cancer, is regulated by calcineurin via a composite LxVPxIxIT motif9,10. We name C16orf74 calcimembrin (CLMB), because it associates with membranes via lipidation (N-myristoylation and S-acylation) and recruits calcineurin to these sites. CLMB is phosphorylated at Thr44 (pThr44) and binds calcineurin with exceptionally high affinity because the flanking LxVP and pThr44 features (LxVPxIxITxx(p)T) enhance PxIxT-mediated binding to CNA. Calcineurin also dephosphorylates pThr44, but this residue is protected when CLMB is bound to the PxIxT-docking surface. Thus, we propose that dephosphorylation occurs in multimers, with one CNA/B bound to two CLMB molecules at the PxIxIT and LxVP-docking sites, respectively. NMR confirms formation of these complexes in vitro. Furthermore, this multimeric model predicts that CLMB dephosphorylation varies depending on the amount of CLMB relative to calcineurin, which we demonstrate via in-cell analyses and kinetic modeling of dephosphorylation in vitro. In summary, this work reveals how CLMB can dynamically shape calcineurin signaling through a mechanism dictated by its composite motif and reversible association with membranes.

Results

Calcimembrin is myristoylated and S-acylated

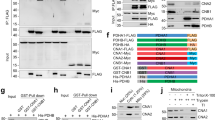

CLMB lacks predicted transmembrane domains but may associate with membranes via lipidation (Fig. 1a)10. CLMB contains a glycine at position 2 (Gly2), a site frequently modified by myristate, a 14-carbon lipid whose co-translational addition can promote protein association with membranes11. CLMB also has two cysteines near its N-terminus, Cys7 and Cys14, one of which, Cys7, is predicted to be modified by S-acylation, the reversible addition of a fatty acid, usually a 16-carbon palmitate, that regulates membrane localization12. To determine if CLMB is lipidated, we metabolically labeled HEK293 Flp-In T-REx cells inducibly expressing wild-type CLMB-FLAG (CLMBWT) with YnMyr and 17-ODYA, alkyne-containing analogs of myristate and palmitate, respectively13. Following immunoprecipitation, analog incorporation was detected via the addition of biotin using CLICK-chemistry, followed by visualization with streptavidin (Fig. 1b). CLMBWT incorporated YnMyr and 17-ODYA, indicating that the protein is both myristoylated and palmitoylated. To identify which residues were lipidated, we mutated proposed sites of S-acylation (CLMBC7,14S) and myristoylation (CLMBG2A) (Fig. 1b). The mutants were expressed at low levels, suggesting instability, which we countered by including a proteasome inhibitor (MG132) in the analyses. CLMBC7,14S showed no 17-ODYA incorporation but maintained YnMyr, suggesting that Cys7 and/or Cys14 are S-acylated. By contrast, neither lipid modification was detected for CLMBG2A, which confirms that Gly2 is myristoylated. Because myristoylation can promote S-acylation by anchoring a protein to the membrane14, we then examined CLMBG2A for S-acylation with increased sensitivity by including palmostatin B (PalmB), a pan-inhibitor of thioesterases that remove S-acylation15. In the presence of this inhibitor, 17-ODYA incorporation into both CLMBWT and CLMBG2A was observed (Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating that CLMBG2A is S-acylated, but with reduced efficiency.

a CLMB schematic showing N-myristoylation (red); S-acylation (yellow), phosphorylation (green), calcineurin-binding motifs LxVP (pink) and PxIxIT (purple). Sequences of wild-type and mutated regions are shown. b Representative immunoblot showing metabolic labeling of CLMB-Flag (wild-type or indicated mutants) with palmitate (17-ODYA) or myristate (YnMyr) analogs, analyzed via CLICK chemistry with biotin-azide and detection with IRdye 800CW streptavidin (“Biotin”). Inputs and immunoprecipitated (IP) samples are shown. Asterisks indicate CLMB dimers. (n = 3 independent experiments). c Representative immunoblot showing S-acylation of CLMB-FLAG (wild-type or indicated mutants) and endogenous calnexin (positive control) detected via Acyl-PEG exchange. Asterisks show PEGylation events. Input, cleaved (NH2OH) and PEGylated (mPEG), and non-cleaved PEGylated conditions are indicated (n = 3 independent experiments). d Representative in-gel fluorescence scan showing pulse-chase analysis of CLMB-FLAG using palmitate (17-ODYA) or methionine (L-AHA) analogs detected via CLICK chemistry with Cy5 or AZDye 488, respectively. Incorporation into CLMB-FLAG with no analog (Neg Ctrl), at 0 or 30 min after unlabeled chase with DMSO (control) or PalmB shown (n = 3 independent experiments). e Data from (d) showing mean ± SEM of 17-ODYA signal normalized to L-AHA; *p < 0.05, T0 vs PalmB p = 0.0103, **p < 0.01, DMSO vs PalmB p = 0.007. f Representative immunoblot showing subcellular fractionation of CLMB-FLAG (wild-type or indicated mutants) with input, cytoplasmic (cyto), and membrane (mem) fractions. GM130 and α-tubulin mark mem and cyto fractions, respectively (n = 3 independent experiments). g Data from (f) showing mean ± SEM cyto or mem signals normalized to total (cyto + mem); n.s. not significant, ****p < 0.0001. CLMBC7,14S vs CLMBG2A: cytoplasm, p = 0.238, membrane p = 0.238. For (e, g), p-values were calculated by two-way ANOVA corrected by Tukey’s multiple comparison. Source data are provided as a Source Data file and at Mendeley Data [https://doi.org/10.17632/6kp379tsv4.1]60.

To determine if CLMB-FLAG is dually S-acylated at Cys7 and Cys14, we used acyl-PEG exchange (APE) in which S-acylated groups are cleaved using hydroxylamine (NH2OH) and exchanged for a PEGylated molecule that increases protein mass by 5 kDa for each S-acylated residue16 (Fig. 1c). Endogenous calnexin, a dually acylated protein, served as a positive control for each sample. For CLMBWT, two slower migrating bands were observed. CLMBC7S lacked the upper band, while CLMBC7,14S was unmodified, indicating that Cys7 and Cys14 are S-acylated in CLMBWT (Fig. 1c). CLMBG2A displayed two sites of S-acylation, but with reduced intensity relative to CLMBWT, consistent with results from metabolic labeling (Fig. 1b). Together, these findings establish that CLMB is myristoylated at Gly2 and S-acylated at Cys7 and Cys14.

Dynamic S-acylation of CLMB mediates membrane association

To examine whether S-acylation of CLMB is dynamic17, we carried out a pair of pulse-chase analyses with two metabolic labels (Fig. 1d, e). L-AHA, an azide-containing methionine analog, detected CLMB-FLAG protein levels, while in parallel, 17-ODYA detected S-acylation. CLMB-FLAG was immunopurified (IP) after labeling for 1 h, followed by a 30-min chase with DMSO or PalmB. Quantifying the 17-ODYA to L-AHA ratio revealed that palmitate incorporation into CLMB increased ~3-fold when thioesterases were inhibited (Fig. 1e, PalmB vs DMSO). This indicates that S-acylation of CLMB turns over rapidly relative to its rate of degradation.

To determine if lipidation mediates CLMB membrane recruitment, we analyzed the localization of CLMBWT and lipidation-defective mutants, CLMBG2A and CLMBC7,14S. Detergent-assisted subcellular fractionation showed that CLMBWT was primarily membrane-associated, appearing in fractions marked by GM130, a Golgi protein. By contrast, both mutants were predominantly cytosolic, appearing in fractions marked by α-tubulin (Fig. 1f, g). Together, these analyses indicate that N-myristoylation, in combination with dynamic dual S-acylation, promotes the stable association of CLMB with membranes.

The composite SLiM in CLMB mediates binding to and dephosphorylation by calcineurin

Next, we examined how each part of CLMB’s composite motif, LDVPDIIIT, contributes to calcineurin binding by generating mutants, CLMBIxITMut (LDVPDAIAA) and CLMBLxVMut (ADAPDIIIT) (Fig. 1a) that disrupt each motif independently without altering the shared proline. To examine binding of these mutants to calcineurin, the association of CLMB-FLAG with GFP-tagged calcineurin (CNA-GFP complexed with endogenous CNB) was assessed following purification of calcineurin from lysates of HEK293 cells co-transfected with these constructs (Fig. 2a, b). CLMBWT but not CLMBIxITMut co-purified with calcineurin, showing that this interaction was PxIxIT-dependent. Less calcineurin co-purified with CLMBLxVMut vs. CLMBWT, showing that the LxVP also makes a modest contribution to calcineurin binding. Furthermore, when expressed and analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), both mutants displayed two electrophoretic forms, with a slower migrating band also faintly observed for CLMBWT (Fig. 2a, input). Phosphorylation, which often reduces electrophoretic mobility, has been reported for CLMB at Thr44 (pThr44) and less frequently at Thr4618. We confirmed that the slower migrating forms of CLMB contained pThr44, as they were absent in mutants lacking this residue (CLMBT44A, CLMBT44A+LxVMut, CLMBT44A,T46A), but not in CLMBT46A (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 2a). These observations indicate that calcineurin binds to CLMB and dephosphorylates pThr44, which is disrupted when either the LxVP or PxIxIT portion of the composite motif is compromised.

a Representative immunoblot showing co-purification of CLMB-FLAG (wild-type and indicated mutants) with CNA-GFP. Inputs and purified (IP) samples shown (n = 3 independent experiments). Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control. b Data from (a) showing mean ± SEM of co-purified CLMB-FLAG normalized to CLMB-FLAG input levels and precipitated CNA-GFP. Indicated p-values calculated by two-way ANOVA corrected by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05; CLMBWT vs CLMBLxVmut p = 0.0325, CLMBWT vs CLMBT44A p = 0.0002. c Representative images of MCF7 cells co-transfected with CLMB-FLAG (wild-type or indicated mutants) and CNA-GFP. Fixed cells immunostained with anti-FLAG (magenta), anti-GFP (yellow), and nuclei (DNA) with Hoechst 33342. Scale bar = 50 μm. Arrows indicate some examples of CLMB and CNA colocalization to the plasma membrane. d Data from (c) showing median with 95% CI for Pearson’s correlation coefficient of CLMB-calcineurin colocalization. Each point represents a single cell. CLMBWT n = 525, CLMBIxITMut n = 641, CLMBLxVMut n = 500, CLMBT44A n = 517. p-values calculated by Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons correction. *p < 0.05 (p = 0.0116), **p < 0.01 (p = 0.0092), ****p < 0.0001. e Dephosphorylation of pCLMBWT (blue) or pCLMBLxVMut (pink) phosphopeptides with 20 nM CNA/B and 1 μM CaM. Mean ± SEM of phosphate released displayed for n = 6 replicates at each timepoint with reaction rate as shown. Source data are provided as a Source Data file and at Mendeley Data [https://doi.org/10.17632/6kp379tsv4.1]60.

Finally, we confirmed that pThr44 enhances binding to calcineurin, as the slower migrating (phosphorylated) forms of CLMBWT and CLMBLxVMut predominantly co-purified with calcineurin (Fig. 2a, IP)10. Indeed, CLMBT44A displayed reduced binding to calcineurin, which was further reduced by mutating LxV (CLMBT44A+LxVMut) (Fig. 2a, b).

The contributions of PxIxIT, LxVP, and pThr44 to calcineurin binding were also examined by measuring the extent of CLMB colocalization with calcineurin (CNA-GFP complexed with endogenous CNB) via immunofluorescence (IF) (Fig. 2c, d). When co-transfected into MCF7 cells, CLMBWT-FLAG and calcineurin colocalize at membranes (see regions marked by arrows in Fig. 2c). In contrast, when co-expressed with CLMBIxITMut, this colocalization was greatly reduced, and calcineurin was predominantly cytosolic. CLMBLxVMut and CLMBT44A also displayed reduced colocalization with calcineurin (Fig. 2c, d), mirroring the trends observed in co-purification analyses (Fig. 2a, b). Thus, CLMB recruits calcineurin to membranes primarily via PxIxT-mediated binding.

Finally, dephosphorylation of pThr44 in CLMB by calcineurin was demonstrated in vitro using phosphorylated peptide substrates that encode residues 21–50 (Fig. 1a). The peptide from pCLMBWT was robustly dephosphorylated compared to pCLMBLxVMut (Fig. 2e), showing that, as for other calcineurin substrates, the LxVP motif promotes catalysis19. Finally, the presence of a functional LxVP motif in the CLMBWT peptide was also confirmed by its ability to inhibit dephosphorylation of the RII peptide, an LxVP-containing calcineurin substrate derived from the regulatory subunit of protein kinase A (RII isoform)19 (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Together, these data show that both the LxVP and PxIxIT components of the composite motif are functional, that CLMB is a calcineurin substrate, and that pThr44 increases CLMB binding to calcineurin.

Phosphorylated Thr44 and the LxVP motif enhance CLMB binding to the PxIxIT docking site

To quantitatively assess CLMB-calcineurin interaction, we used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and fluorescence polarization anisotropy (FP) to measure binding of CLMB peptides containing the composite SLiM (residues 21–50) to purified, catalytically inactive CNA/B containing CNATrunc+H151Q. This mutant CNA lacks the C-terminal autoinhibitory region, which allows LxVP motifs to bind to CNA/B in the absence of Ca2+/CaM20. ITC revealed that the phosphorylated CLMBWT peptide (pCLMBWT) binds calcineurin at a one-to-one ratio with high affinity (KD = 37 nM) (Fig. 3a). FP using FITC-labeled peptides at pH 7.4 revealed that phosphorylation of Thr44 enhances CLMB binding to calcineurin ~20-fold (KD = 14 nM vs 291 nM) (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, the affinity of pCLMBWT for calcineurin was similar over a pH range (6.9–8.0), which should change the protonation state of histidine residues (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). This included the histidine immediately preceding the LxVP (H32), which is expected to engage with calcineurin during LxVP docking7. Measurements made with tag-free CLMB peptide via ITC vs. fluorescein isothiocyanate-tagged (FITC) peptide with FP indicated at most a modest difference in observed affinities, which is common when using orthogonal biophysical methods (37 vs 14 nM for pCLMBWT) (Fig. 3a, b). Thus, we concluded that the FITC tag had no major effect on calcineurin-binding and used FP for the remaining comparisons due to the high-throughput capability of this method. To test if the high-affinity pCLMBWT-calcineurin binding observed was PxIxIT-mediated, we used FP to assess the ability of CLMB peptides to compete with a well-characterized PxIxIT peptide, FITC-PVIVIT21,22, for calcineurin binding (Fig. 3c, e). pCLMBWT competed with PVIVIT most effectively, with peptides lacking the LxVP motif (pCLMBLxVMut), or pThr44 (CLMBWT) showing reduced competition (Fig. 3c, e). pCLMBIxITMut, lacking the PxIxIT motif, was unable to displace PVIVIT from CNA/B. When these experiments were repeated using FITC-pCLMBWT peptide in place of FITC-PVIVIT (Fig. 3d, e), a similar pattern was observed, although phosphorylation of T44 (pCLMBWT vs CLMBWT) caused a much greater reduction in Ki (30X vs 3X for PVIVIT competition). Importantly, CLMB peptides accurately mimic full-length CLMB binding to calcineurin as both caused equivalent displacement of FITC-pCLMBWT (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d). Altogether, these data show that, like PVIVIT, pCLMBWT peptides bind to the PxIxIT docking groove on CNA and that flanking residues, i.e., LxV and pThr44, enhance binding to form an extended LxVPxIxITxxT(p) sequence with exceptionally high affinity for calcineurin.

a Determination of the affinity between CNA/B and unlabeled pCLMBWT peptide using isothermal calorimetry. Dissociation constant (KD) = 37 ± 1.2 nM, reaction stoichiometry (n value) = 1.00 ± 0.02, enthalpy (ΔH) = −4 ± 0.8, and entropy (TΔS) = 21 ± 3 are shown. Data are mean ± s.d. for n = 3 independent experiments. b Binding isotherm obtained by titration of unlabeled pCLMBWT peptide into CNA/B (40 μM). c Fluorescence polarization (FP) saturation binding curves of FITC-pCLMBWT and FITC-CLMBWT (5 nM) incubated with serial dilutions of CNA/B (0 to 5 μM). FP data (mean values from n = 2 independent experiments) were fitted to a one-site binding model. KD’s are as shown. d Competitive binding assay of unlabeled pCLMBWT, CLMBWT, pCLMBIxITMut, and pCLMBLxVMut peptides titrated against FITC-PVIVIT peptide (5 nM) in the presence of 2 μM CNA/B. Values are plotted for n = 2 independent experiments. e Competitive binding assay of unlabeled pCLMBWT, CLMBWT, pCLMBIxITMut, and pCLMBLxVMut peptides titrated against FITC-pCLMBWT peptide (5 nM) in the presence of 0.08 μM CNA/B. Values are plotted for n = 2 independent experiments. f Table displaying the experimentally obtained IC50 values and converted Ki values from data in (d, e). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

NMR analysis shows CLMB binding to two sites on calcineurin

Next, to investigate the structure of CLMB in the presence and absence of calcineurin, we used solution-state NMR. 88% of non-proline backbone resonances were assigned using a standard set of triple-resonance experiments, utilizing full-length dually 13C- and 15N-labeled CLMB (76 residues) that was expressed in E.coli (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 4a). To assess CLMB secondary structure, we employed TALOS-N, a computational method that predicts backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts23. This revealed that CLMB is disordered overall, but contains two regions with a tendency to form a β-strand (Supplementary Fig. 4b): Residues I38-I40 include the PxIxIT, consistent with binding of this motif-type to CNA as a β-strand22. N-terminal residues, Q12-V15, were also predisposed to localized folding, suggesting possible involvement in other binding interactions. Similar analyses carried out for CLMB using chemical shift secondary structure population interference (CheSPI)24 confirmed the absence of secondary structure (Supplementary Fig. 4c). We were unable to examine CLMB containing pThr44 in NMR experiments due to technical limitations in generating the mono-phosphorylated protein in vitro. Substituting glutamate for threonine at position 44 (CLMBT44E) failed to show increased affinity for CNA/B (data not shown).

a 15N HSQC spectra of free CLMB with the resonance assignment. b NMR spectral analysis of CLMB interaction with CNA at 2:1 (CLMB: CNA); c with CNA at 1:1 (CLMB: CNA); d with CNA/B at 2:1 (CLMB: CNA/B); e with CNA/B at 1:1 (CLMB: CNA/B). b–e Graphs display the intensity ratios of CLMB resonances with and without the titrant (CNA or CNA/B) at different molar ratios. The ratios corresponding to the LxV motif (pink) and IxIT (purple) are highlighted. Residues with no access to the intensity ratio are represented with negative numbers, and peaks resulting in complete broadening are shown in green (I/I0 = −0.4). Unassigned residues in apo CLMB are blue (I/I0 = −0.2), prolines (which are not represented in 15N-HSQC are gray (I/I0 = −0.2), and residues for which the bound resonance cannot be unambiguously assigned are red (I/I0 = −0.2). *Residues with I/I0 higher than 1 due to overlapping resonances. NMR chemical shift data have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB) under accession code [52641].

To map the interaction interface of calcineurin on CLMB, we focused first on PxIxIT-mediated interactions by titrating 15N-labeled CLMB with varying molar ratios of monomeric recombinant CNA in the absence of CNB and monitoring the interaction through 15N-1H SOFAST-HMQC experiments (Fig. 4). No additional insights were gained from BEST-TROSY experiments25. CNA can bind to PxIxIT motifs but lacks the LxVP-binding surface found at the interface of CNA and CNB4. Due to the size of the CLMB-CNA complex, we anticipated significant broadening of NMR signals at the interaction interface. This broadening can also arise from exchange kinetics between the observable CLMB and the titrant, CNA, making it challenging to distinguish the two effects. As expected, at a molar ratio of 2:1 (CLMB: CNA), many of the CLMB signals undergo significant line broadening (Fig. 4b), which become more pronounced at a molar ratio to 1:1, due to the majority of CLMB being bound to CNA (Fig. 4c). This is particularly true for signals corresponding to the PxIxIT and LxVP motifs, indicating, as observed in FP experiments, that LxV residues participate in binding to the PxIxIT interface (Fig. 4b, c, Supplementary Fig. 2d). Line broadening across the majority of CLMB residues indicates that the interaction interface on CLMB extends beyond the PxIxIT and LxVP motifs (Fig. 4b, c). Interactions with the N- and C-terminal residues of CLMB may be an avidity-driven effect, anchored by PxIxIT binding, as has been reported for other calcineurin substrates26.

To investigate binding that may occur at the LxVP-docking site of calcineurin, we next titrated CLMB with the heterodimeric CNA/B complex (Fig. 4d, e). Signal broadening at the N-terminus of CLMB was more pronounced with CNA/B relative to CNA alone, suggesting possible interactions between CLMB and CNB (Fig. 4b, c vs 4d, e, and Supplementary Fig. 4d). These include the Q9-V12 region that displayed partial folding in the absence of calcineurin. At a molar ratio of 2:1 (CLMB: CNA/B), more broadening is observed in LxVP but not PxIxIT residues when compared to the interaction with CNA (Fig. 4d vs 4b, and Supplementary Fig. 4c). This includes not only L33 and V35, but also H32, another residue expected to participate in LxVP binding to CNA/B7. However, at a molar ratio of 1:1, where essentially all CLMB should be PxIxIT-bound (given the higher KD for PxIxIT vs LxVP and our working concentrations), the pattern of line broadening at the composite motif is similar when complexed with either CNA or CNA/B (Fig. 4c vs 4e). To better visualize LxVP-mediated binding of CLMB to CNA/B, NMR analyses were also performed in the presence of pCLMBLxVPmut peptide (which was not isotopically labeled) to saturate the PxIxIT binding site on CNA/B (Supplementary Fig. 5). While addition of this peptide on its own caused no change in the NMR spectrum for 15N-labeled CLMB (Supplementary Fig. 5a), in the presence of CNA/B (2:1 or 1:1 CLMB: CNA) residues in the LxVP motif, particularly H32 and L33, displayed shifting and broadening effects in addition to N-terminal residues, as previously observed (Supplementary Fig. 5b, c). Together, these findings show that when in excess (2 CLMB: 1 CNA/B), CLMB engages calcineurin (CNA/B) through both its LxVP and PxIxIT motifs.

To investigate the CLMB-calcineurin interaction further, we carried out structural predictions using AlphaFold 3 for 2 CLMB molecules and CNA/B containing truncated CNA lacking the C-terminal calmodulin binding and regulatory domains (Supplementary Fig. 6a–c)27. Consistent with our NMR analyses, the models show two copies of CLMB simultaneously bound to CNA/B, one each at the LxVP and PxIxIT docking sites. Predicted interactions of pCLMB containing pThr44 with CNA/B were nearly identical; however, with the LxVP-bound CLMB molecule showing an additional interaction of pThr44 with the active site, as would occur during catalysis (Supplementary Fig. 6a–c). Thus, these models suggest that the formation of multimeric complexes (2 CLMB: 1 CNA/B) will facilitate dephosphorylation of pCLMB.

Calcineurin dephosphorylates CLMB by forming multimers

Next, we sought to test the prediction that pThr44 dephosphorylation is promoted when CLMB is in excess (2 CLMB: 1 CNA/B) but inhibited at lower CLMB: CNA/B ratios, where PxIxIT-bound complexes are favored and protect pThr44 from dephosphorylation. To this end, we inducibly expressed CLMBWT-FLAG in HEK293 Flp-In T-REx cells and compared its phosphorylation status with endogenous vs overexpressed calcineurin (i.e., transfection of GFP-CNA, which complexes with endogenous CNB). In stark contrast to a typical substrate, CLMB-FLAG phosphorylation at T44 increased upon calcineurin overexpression (Fig. 5a, b, Supplementary Fig. 7a). Intact PxIxIT binding rather than catalytic activity was required for this effect, as overexpressing catalytically inactive calcineurin (containing GFP-CNAH151Q)28, but not calcineurin that is defective for PxIxIT binding (containing GFP-CNANIR)29, increased CLMB-FLAG phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 7b). We predicted that further increasing CLMB levels in these calcineurin overexpressing cells would promote dephosphorylation of CLMB-FLAG by increasing the CLMB:CNA/B ratio. Thus, we overexpressed V5-tagged CLMB in HEK293 Flp-In T-REx cells that inducibly expressed CLMB-FLAG and overexpressed calcineurin (GFP-CNA complexed with endogenous CNB) (Fig. 5a–c). As predicted, phosphorylation of CLMBWT-FLAG decreased upon expression of CLMBWT-V5. This effect was dependent on PxIxIT binding, as introducing CLMBIxITMut-V5 did not decrease CLMBWT-FLAG phosphorylation, but CLMBLxVMut-V5, which contains an intact PxIxIT motif, did (Fig. 5a–c). For CLMBWT, when CLMBLxVMut was expressed, its phosphorylation was enhanced by overexpression of calcineurin and rescued by co-expression of CLMBWT-V5 or CLMBLxVMut-V5 but not CLMBIxITMut-V5. However, because dephosphorylation is impaired by mutation of the LxV (Fig. 2e), CLMBLxV-FLAG displayed increased levels of phosphorylation relative to CLMBWT under all conditions (Fig. 5a, b). Finally, we repeated these analyses using CLMBIxITMut-FLAG, which displayed partial phosphorylation regardless of calcineurin levels. Surprisingly, CLMBIxITMut-FLAG was predominantly dephosphorylated when co-expressed with CLMBWT-V5 or CLMBLxVMut-V5 but not CLMBIxITMut-V5 (Fig. 5a, b). Thus, although the LxVP and PxIxIT components of the CLMB composite motif are both required for efficient dephosphorylation, they do not need to be on the same molecule. A single copy of CLMB must have an LxVP to mediate its own dephosphorylation but can utilize the PxIxIT of neighboring copies to recruit calcineurin, promote LxVP binding, and be dephosphorylated (Fig. 5c, bottom row).

a Representative immunoblot showing phosphorylation-induced mobility shifts in CLMB-FLAG (wild-type or indicated mutants) when co-expressed with GFP-CNA and CLMB-V5 (wild-type or indicated mutants). GAPDH was used as a loading control. b Data from (a) showing mean ± SEM phospho-CLMB-FLAG normalized to total CLMB-FLAG. p-values calculated by two-way ANOVA corrected by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (n = 3 independent experiments). n.s., not significant; without vs with CLMBIxIxITmut-V5 expression: p = 0.995, 0.748, 0.999 from left to right. CLMBIxITmut without vs with CNA-GFP p = 0.626. ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, p = 0.0005. c Cartoon representation of calcineurin (turquoise)-CLMB complex formation and CLMB dephosphorylation (removal of pink “P”) under conditions in (a), i.e., CLMB-FLAG (blue with “F”) overexpression with or without co-expression of Calcineurin-GFP and CLMB-V5 (green with “V”) as indicated. Top row shows CLMBWT-FLAG, bottom row shows CLMBIXITMut-FLAG (labeled LDVPxxxx). d (Top) Experimental data showing phosphate released from 100 nM pCLMBWT (blue) or pCLMBIxITMut (purple) phosphopeptide dephosphorylated by 20 nM (left), 100 nM (middle) or 200 nM (right) CNA/B and 1 μM calmodulin. Each dephosphorylation rate is displayed, and data are mean ± SEM at each timepoint; n = 6 independent replicates for all conditions except pCLMBIxITMut with 200 nM CNA/B, where n = 5. (Bottom) Overlay of experimental data (circles) with results of kinetic simulations (solid lines) using the model shown in Fig. S5a, b for each calcineurin concentration. Source data are provided as a Source Data file and at Mendeley Data [https://doi.org/10.17632/6kp379tsv4.1]60.

To demonstrate more precisely how the ratio of CLMB to calcineurin affects dephosphorylation, we conducted a series of in vitro dephosphorylation assays using a fixed substrate concentration (100 nM pCLMBWT or pCLMBIxITMut peptides) with increasing concentrations of purified calcineurin (CNA/B) (20, 100 or 200 nM) (Fig. 5d, top row). Under these in vitro conditions, pCLMBIxITMut was efficiently dephosphorylated due to high enzyme and substrate concentrations and the absence of any competing PxIxIT-containing proteins. For pCLMBIxITMut, we observed that dephosphorylation rates increased significantly with the calcineurin concentration (Fig. 5d, top row). In contrast, dephosphorylation of pCLMBWT increased modestly as calcineurin increased from 20 vs 100 nM, and then decreased slightly at 200 nM calcineurin, where enzyme concentration exceeded that of substrate (100 nM) (Fig. 5d, top row). To better understand this unusual reaction behavior, we turned to kinetic modeling. First, we developed a model describing the complex series of reactions we expect to occur, based on our NMR and in-cell analyses of CLMB-calcineurin interactions (Supplementary Fig. 8). For pCLMBIxITMut, which contains only an LxVP motif (Supplementary Fig. 8b), the substrate binds to the LxVP-docking site of calcineurin (k2, k-2) and is dephosphorylated (k3), leading to product formation. Thus, dephosphorylation accelerates with increasing enzyme concentration (Fig. 5d, top row). However, for dephosphorylation of pCLMBWT (Supplementary Fig. 8a), we propose competition between two binding modes: high-affinity binding to the PxIxIT-docking site (k1, k-1), which prevents pT44 phosphorylation, or lower-affinity LxVP-mediated binding (k2, k-2), which leads to dephosphorylation (k3). Furthermore, the model allows one enzyme molecule to bind substrate at each of these sites simultaneously (ES1S2). For this complex reaction mechanism, increasing enzyme concentration drives formation of more LxVP-bound substrate and dephosphorylation, but this is offset by reduced substrate availability due to increased PxIxIT-mediated substrate binding and pThr44 protection. Thus, dephosphorylation rates decrease as enzyme concentration exceeds that of substrate (Fig. 5d, top row).

To further probe this proposed mechanism, we then used kinetic modeling software (KintekExploerTM), which fits experimental data directly through dynamic simulation and does not require simplifying assumptions30. After providing initial values for rate constants consistent with published reports6,31, our experimental data were fit to the proposed kinetic model (Fig. 5d bottom row and Supplementary Fig. 8). The resulting rate parameters were well within expected values, and the predicted KD for phosphorylated PxIxIT binding to calcineurin was 7 nM (Supplementary Fig. 8c), which agrees well with experimentally determined values (Fig. 3a, c). However, we noted that some parameters, particularly on and off rates for substrate binding, were poorly constrained by the model. Therefore, we manually manipulated different parameters to better understand how relationships between them influenced the fit to our data (Supplementary Fig. 9). This revealed that the equilibrium binding constant for phospho-PxIxIT binding was critical rather than specific on and off rates (k1 and k-1) (Supplementary Fig. 9a, b). Furthermore, the k1 and k-1 values predicted by kinetic simulations represented lower limits for these rates as decreasing them caused significant deviations from the data despite keeping the KD constant (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Similarly, koff for LxVP binding (k-2) and kcat (k3) could be increased proportionally without significantly affecting the overall fit (Supplementary Fig. 9c), suggesting that the catalytic efficiency of LxVP-mediated dephosphorylation is a key driver of the observed reaction kinetics. Confirming this, we found that maintaining the second-order rate constant was critical for good agreement between the data and the model (Supplementary Fig. 9d). Thus, overall, kinetic modeling of our in vitro dephosphorylation data supports the hypothesis that phosphorylated CLMB is dephosphorylated via multimer formation. This mechanism, which requires substrate levels to exceed those of calcineurin for efficient dephosphorylation, is dictated by the composite LxVPxIxIT motif.

Discussion

Here, we describe multivalent interactions between calcineurin and CLMB, an intrinsically disordered microprotein and calcineurin substrate that dynamically associates with membranes via protein lipidation. We elucidate roles for a composite motif in CLMB, LxVPxIxIT, that combines two SLiMs, PxIxIT and LxVP, with distinct binding modes and functions in calcineurin signaling.

Calcineurin, the conserved and ubiquitously expressed calcium/calmodulin-regulated protein phosphatase, has been categorized as a dynamic or date hub and specifically as a linear motif binding hub (LMB-hub) because it engages a diverse set of partners that bind competitively to the structurally plastic PxIxIT docking groove32. PxIxIT peptides from natural substrates bind to calcineurin as a β strand, vary greatly in sequence and typically have low affinities (~2.5 to 250 micomolar)26,33, while regulators and scaffolds, including PVIVIT, the selected inhibitor peptide, have KD’s of ~0.5 micromolar21,34,35. By contrast, we show that the 32HLDVPDIIITPP(p)TP45 sequence in CLMB binds calcineurin at the PxIxIT-docking groove with a KD of ~14 nM. This extraordinary affinity is mediated predominantly via binding of the core PxIxIT motif which is enhanced ~20-fold by phosphorylation at the +3 position (pThr44), and ~5 fold by the N-terminal LxV sequence (Fig. 3). Such high affinities have also been achieved by engineering the PVIVIT peptide to include a hydrophobic residue at the -1 position and a phosphothreonine at the +3 position, although phosphorylation does not universally enhance PxIxIT affinity35. A natural PxIxIT peptide derived from an endogenous inhibitor of calcineurin (CABIN1),2145PPEITVTPP(p)TP2156 also shows high affinity (~170 nM) due to phosphorylation of its C-terminal sequence, PPTP, which is identical to that found in CLMB34. This proline-rich sequence is predicted to form a polyproline helix that may function to extend the β-strand interaction with calcineurin36,37. Thus, the composite LxVPxIxIT motif in CLMB combines several features that consistently stabilize PxIxT-docking. Because calcineurin is an LMB-hub, such high-affinity PxIxIT peptides typically inhibit signaling by preventing its interaction with substrates35,38. It is surprising, therefore, that CLMB exhibits high affinity PxIxIT-mediated docking yet is also dephosphorylated by calcineurin. As we demonstrate, this is only possible due to the LxVP portion of the composite SLiM in CLMB, and dephosphorylation can only occur when excess CLMB levels allow lower-affinity LxVP-docking to occur on a molecule of calcineurin whose PxIxIT-docking site is saturated.

Based on our findings, we present two models for how CLMB may shape calcineurin activity in vivo (Fig. 6). First, dynamic S-acylation promotes CLMB association with membranes (Fig. 6a, Step 1), where, when phosphorylated, it recruits a localized pool of calcineurin via high-affinity PxIxIT-mediated binding (Fig. 6a, Step 2). This membrane sequestration may prevent calcineurin from dephosphorylating substrates in other cellular locations. In the presence of a Ca2+ signal, Ca2+ and CaM then activate calcineurin, which exposes the LxVP-docking site39. If CLMB is in excess relative to calcineurin and PxIxIT binding is fully saturated, a second CLMB molecule will bind via its LxVP motif, which positions pThr44 for dephosphorylation at the active site (Fig. 6a, Step 3). However, as the population of CLMB shifts to the dephosphorylated form, PxIxIT-binding affinity decreases (Fig. 3), which promotes calcineurin dissociation from CLMB, allowing the enzyme to engage and dephosphorylate other nearby LxVP- and PxIxIT-containing substrates (Fig. 6a, Step 4). This tuning of PxIxIT affinity is critical for signaling, as demonstrated for AKAP5, a scaffold that concentrates both calcineurin and NFAT near L-type Ca2+ channels in neurons to promote NFAT dephosphorylation40. In that case, increasing the AKAP5 PxIxIT affinity for calcineurin ~two-fold significantly impaired NFAT activation due to increased sequestering of calcineurin41.

a (1) CLMB localizes to membranes via dynamic acylation, where it (2) recruits calcineurin (turquoise). At low CLMB levels, calcineurin remains tightly bound to phosphorylated CLMB (purple) regardless of Ca2+ signals. (3) At higher CLMB levels, CLMB (purple and green) forms multimers with calcineurin and is dephosphorylated upon calcineurin activation by Ca2+ and CaM. (4) Calcineurin is then released and can engage and dephosphorylate membrane-associated substrates (red) that contain PxIxT and LxVP SLiMs. b (1) CLMB localizes to membranes via dynamic acylation, where it (2) recruits calcineurin (turquoise). At low CLMB levels, calcineurin remains tightly bound to phosphorylated CLMB (purple). (3) Ca2+ and CaM activate calcineurin, allowing it to engage and dephosphorylate LxVP-containing substrates (red). (4) At high CLMB levels (purple and green), calcineurin-CLMB multimers form. (5) This promotes CLMB dephosphorylation and triggers calcineurin release to terminate signaling.

In our second model (Fig. 6b), active calcineurin-pCLMB dimers (1 CLMB: 1 CNA/B) directly engage and dephosphorylate substrates at the membrane that contain an LxVP, but no PxIxIT motif (Fig. 6b, step 3). Such substrates are exemplified by PRKAR2A, the type II-alpha regulatory subunit of protein kinase A, which contains an LxVP but depends on the PxIxIT motif within its binding partner, AKAP5, to recruit calcineurin and promote dephosphorylation9,42. Proteome-wide predictions suggest that many proteins may similarly harbor an LxVP without an associated PxIxIT9. In our second model (Fig. 6b), active calcineurin-pCLMB dimers (1 CLMB: 1 CNA/B) directly engage and dephosphorylate such PxIxIT-less substrates at the membrane (Fig. 6b, step 3). Simply recruiting calcineurin to membranes, where association kinetics are 20–30 fold faster than in the cytosol of eukaryotic cells, may enhance LxVP binding, causing their efficient dephosphorylation in the absence of a PxIxIT motif43. Such division of the PxIxIT and LxVP motifs among two molecules may also allow for the high-affinity PxIxIT observed in CLMB. In substrates that contain both a LxVP and PxIxIT motif, stable PxIxIT binding would be expected to limit enzymatic efficiency by slowing product release. However, acting only as a scaffold, CLMB can remain tightly associated with calcineurin via PxIxIT-binding while other substrates cycle in and out of the LxVP-binding surface to be dephosphorylated. In this scenario (Fig. 6b), calcineurin remains at the membrane either until CLMB levels increase sufficiently to allow CLMB dephosphorylation and calcineurin dissociation (Fig. 6b step 4) or until CLMB is de-acylated. In both models, intracellular Ca2+ dynamics, CLMB protein levels, and S-acylation/de-acylation activities combine to modulate calcineurin signaling. Future studies aim to identify the palmitoyl acyltransferases (PATs) and acyl protein thioesterases (APTs) that dynamically regulate CLMB S-acylation to better understand how these critical regulators contribute to calcineurin-CLMB signaling in vivo.

Another missing player in our model is the kinase(s) that phosphorylates CLMB at Thr44. One candidate is the stress-activated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), which phosphorylates the identical PxIxIT-flanking sequence in Cabin1 (PP(p)TP)34,44. Because phosphorylation increases CLMB-calcineurin affinity, kinase activation is required to prime regulation of calcineurin signaling by CLMB. However, phosphorylation also establishes a negative feedback mechanism, with dephosphorylation decreasing calcineurin’s interaction with its substrate. Thus, regulators that modify kinase activity may also significantly affect CLMB-calcineurin signaling dynamics.

This study highlights the critical role that SLiMs play in conferring flexibility, tunability and dynamism to cell signaling at the molecular level. Further studies are needed to establish whether composite LxVPxIxT motifs always limit substrate dephosphorylation to occurring in a multimeric complex. Of at least 30 human proteins containing predicted LxVPxIxIT motifs, several are ion channels, such as TRPM6, that assemble into higher order complexes45, suggesting that these motifs could be a fidelity mechanism that limits dephosphorylation to substrates that are properly assembled into complexes. Similarly, multivalency is a characteristic exhibited by many SLiMs. Some composite SLiMs bind multiple partners in an exclusive manner, for example, requiring a kinase and a phosphatase to compete for access to a shared substrate46,47. For the intermediate chain of dynein, multivalency regulates assembly of the dynein complex and its interaction with distinct binding partners48. In the cell cycle regulator CDKN1A (p21), sequences that flank the PCNA-binding SLiM also encode an essential nuclear localization sequence49. Thus, ‘composite’ SLiMs that encode multiple interactions may be more common than currently appreciated. This complexity emphasizes how critical SLiM-based interactions are for integrating and coordinating the plethora of possible protein-protein interactions that dictate cellular responses.

A major challenge that lies ahead is to identify the molecular targets and physiological functions that are regulated by calcineurin-CLMB. While this manuscript was being revised for publication, another study showed that C16orf74/MICT1 is highly expressed in brown fat in mice and controls thermogenesis by regulating the dephosphorylation of PKA RIIβ by calcineurin50. In some pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) derived cell lines, CLMB increases proliferation and migration, suggesting that CLMB shapes calcineurin signaling to promote oncogenesis10. Indeed, high CLMB expression is associated with poor patient outcomes for PDAC, melanoma and head and neck cancer10,51. Mechanisms underlying these activities have not yet been identified, but these cancers may provide good starting points for examining how CLMB modifies calcineurin signaling in a clinically relevant context.

Methods

Cell culture and transfection

Cells were cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2. HEK293 Flp-In TReX and MCF7 cell lines were grown in standard media containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 4.5 mg/mL glucose, L-glutamine, and sodium pyruvate (Cytiva SH30243.FS) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Corning MT35010CV). Transfections were done according to the manufacturer’s instructions. HEK293 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific 11668019). MCF7 cells were transfected using Transfex ATCC transfection reagent (ATCC ACS−4005).

Plasmids

DNA encoding CLMB subcloned into pcDNA3 or pcDNA5/FRT/TO between HindIII and BamHI cut sites. C-terminal FLAG or V5 tags were introduced between BamHI and XhoI sites. pcDNA5/FRT/TO encoding GFP-tagged CNA has been used previously8. Variants of CLMB (CLMBC7S, CLMBC7,14S, CLMBG2A, CLMBIxITMut, CLMBLxVMut, CLMBLxVPMut+T44A, CLMBT44A, CLMBT46A, CLMBT44A+T46A) and CNA (CNAH151Q, CNANIR) were generated using the Quickchange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent). All plasmids and cloning primers used in the study can be found in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5.

Antibodies

All antibodies used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 6 along with their source and dilutions used.

Stable cell line generation

On day one, 9.6 × 105 HEK293 Flp-In TReX cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 with 1.5 µg pOG44 and 0.5 µg pcDNA5 FRT TO encoding proteins of interest in a 6-well dish (plasmid # 2801, 2852, 2860, 2861, 2862, 2863, 2864, and 2880) as described in Supplementary Table 5. Transfections were done according to the manufacturer’s instructions. On day two, transfected cells were passaged onto 10 cm plates. On day three, selection was started using media containing 3 µg blasticidin and 200 ng/mL hygromycin. The selection media was replaced every 2–3 days until distinct colonies appeared. Colonies were selected using cloning rings and expanded before being stored in liquid nitrogen.

Metabolic labeling to detect CLMB lipidation

HEK293 Flp-In TReX lines stably expressing CLMBWT, CLMBC7,14S, or CLMBG2A were induced with 10 ng/mL doxycycline for 24 h and split evenly among three 10 cm tissue culture dishes. The following day, cells were rinsed with PBS and incubated in DMEM containing 4.5 mg/mL glucose, L-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, 2% FBS, and either 20 µM YnMyr (Click Chemistry Tools 1164-5), 30 µM 17-ODYA (Cayman Chemical Company 34450-18-5), or vehicle (ethanol and DMSO) overnight. Cells were then co-incubated with 20 µM YnMyr, 30 µM 17-ODYA, or vehicle and 20 µM MG132 (EMD Millipore 474787-10MG) for 4 h before being washed twice in PBS and frozen at −80 °C. Cells were lysed in 400 µL TEA lysis buffer (50 mM TEA pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and 1 mM PMSF) by inverting for 15 min at 4 °C. Lysates were passed five times through a 27-gauge needle, centrifuged at 16,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C, and protein content was determined by Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific 23225). 25 µg total lysate was removed as input, and 0.5 mg total protein was incubated with pre-washed magnetic M2 anti-FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich M8823-5ML) beads at 4 °C for 1.5 h while inverting. Beads were washed 3X with modified RIPA (50 mM TEA pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and 1% sodium deoxycholate) and resuspended in 40 µL 1x PBS. 10 µL of 5x click reaction mix (1x PBS, 0.5 mM biotin azide, 5 mM TCEP, 0.5 mM TBTA, 5 mM CuSO4) was added and reactions incubated for 1 h at 24 °C, shaking at 550 RPM. Beads were washed 3X in modified RIPA and eluted 2X using 30 µL of 1 mg/mL FLAG peptide in modified RIPA buffer. 12 µL of non-reducing 6x SDS sample buffer was added to eluate before heating at 95 °C for 2 min and analysis by SDS-PAGE. Note that the addition of reducing agents to the SDS sample buffer results in a loss of 17-ODYA signal. Samples were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and lipidation was detected using fluorophore-tagged streptavidin and total CLMB with anti-FLAG. Immunoblots were imaged using a Licor Odyssey CLx and quantified with Image Studio software.

Metabolic pulse-chase labeling assay to assess dynamic CLMB S-acylation

HEK293 Flp-In TReX cells stably expressing CLMBWT-FLAG were induced with 10 ng/mL doxycycline for 48 h. Cells were rinsed 2X in PBS and incubated in methionine-free DMEM supplemented with 5% charcoal-stripped FBS, 1 mM L-glutamate, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.4 mM cysteine and 10 ng/mL doxycycline along with vehicle (ethanol), 30 µM 17-ODYA, 50 µM L-AHA, or 17-ODYA and L-AHA together. After 2 h, cells were washed 2X in PBS and either harvested immediately or incubated in standard media supplemented with 10 µM palmitic acid and 10 ng/mL doxycycline, with or without 10 µM palmostatin B (EMD Millipore 178501-5MG). Cells were rinsed in PBS and frozen at −80 °C. Metabolic labeling was done as described in the previous section, with the exception that two rounds of labeling were done. First, Cy5-azide (Click Chemistry Tools AZ118-1) was linked to 17-ODYA. Then, cells were washed and L-AHA was linked to AF−488 (Click Chemistry Tools 1277-1) alkyne before being washed three additional times and eluted using FLAG peptide. Samples were resolved via SDS-PAGE, and in-gel fluorescence was read using the GE Amersham Typhoon imaging system. Images were quantified in Image Studio. The proportion of S-acylated CLMB is calculated as Cy5/A−488 normalized to the no chase control.

Acyl-PEG exchange

HEK293 Flp-In TReX lines stably expressing CLMBWT, CLMBC7S, CLMBC7,14S, or CLMBG2A were induced with 10 ng/mL doxycycline for 48 h. Cells were rinsed 2X in PBS and stored at −80 °C. Cells were lysed in 400 µL lysis buffer (50 mM TEA pH 7.3, 150 mM NaCl, 2.5% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, 100 units benzonase) at 37 °C for 20 min, shaking at 800 RPM. Lysates were passed 10X through a 27-gauge needle, centrifuged at 16,000×g for 5 min and protein quantified by BCA. Lysates were adjusted to 2 mg/mL and incubated with 10 mM TCEP for 30 min at room temperature. Cysteines were protected by incubating with 25 mM NEM for 2 h at 40 °C, shaking at 800 RPM. Protein was precipitated overnight with four volumes of acetone at −20 °C, centrifuged at 16,000×g for 20 min at 4 °C and washed 4X in 70% acetone. Acetone was removed, pellets air-dried to remove all traces of acetone and resuspended in 75 µL Buffer A (50 mM TEA pH 7.3, 150 mM NaCl, 4% SDS, 0.2% Triton X-100, 4 mM EDTA) for 1 h at 40 °C, shaking at 800 RPM. Samples were centrifuged at 16,000×g for 2 min, 7 µL removed as input, and the remainder split into +cleavage and -cleavage fractions. The +cleavage sample containing 1% SDS was treated with 750 µM hydroxylamine (final concentration) for 1 h at 30 °C, rotating end over end. Following methanol-chloroform precipitation (ice cold, final concentrations 42% methanol, 16% chloroform), samples were centrifuged at 16,000×g for 20 min at 4 °C, aqueous layer removed, washed 3X with 100% methanol and air-dried. Pellets were resuspended as described in Buffer A and incubated in 1 mM mPEG-Mal (Methoxypolyethylene glycol maleimide, 5 kDa, 63187 Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h at room temp, rotating end over end. Samples were methanol-chloroform precipitated as described, resuspended in Lysis buffer with 1X SDS-PAGE sample buffer, resolved using SDS-PAGE and visualized via immunoblotting with mouse anti-FLAG to detect CLMB-FLAG. Endogenous calnexin was detected using anti-calnexin antibodies. Immunoblots were imaged using a Licor Odyssey CLx and quantified with Image Studio software.

Detergent-assisted subcellular fractionation

HEK293 Flp-In TReX lines stably expressing CLMBWT, CLMBC7,14S, or CLMBG2A were induced with 10 ng/mL doxycycline for 48 h and 20 µM MG132 (EDM Millipore 474787-10MG) for 4 h prior to harvesting. Cells were washed 2X in PBS, harvested and immediately lysed in 600 µL of Cytoplasm Buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 6.8, 100 mM NaCl, 300 mM sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EDTA, 0.015% digitonin, 1x halt protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fischer scientific 78442)) at 4 °C for 15 min. 60 µL of total lysate was removed as input, and the remainder was centrifuged at 1000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed as cytoplasmic fraction, and the pellet was washed 2X in PBS and resuspended in 600 µL membrane buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 300 mM sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2, 3 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1x halt protease inhibitor cocktail) for 30 min at 4 °C turning end over end. Insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation at 5000×g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was removed as membrane fraction. Both fractions were centrifuged at 12,000×g at 4 °C for 10 min. Samples were heated in 1X SDS sample buffer at 95 °C for 5 min, resolved via SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted and CLMB-FLAG detected using anti-FLAG antibodies; anti-GM130 and anti-α-tubulin were used as membrane and cytosolic markers, respectively. Immunoblots were imaged using a Licor Odyssey CLx and quantified with Image Studio software. CLMB in cytosolic and membrane fractions was quantified as CLMBCyto/(CLMBCyto+ CLMBMem) and CLMBMem/(CLMBCyto + CLMBMem), respectively.

Immunofluorescence, microscopy, and image analysis

MCF7 cells were co-transfected (as described previously) with equal amounts of pcDNA5 encoding CLMBWT, CLMBIxITMut, CLMBLxVMut, CLMBT44A and pcDNA5 encoding CNA-GFP. The following day, cells were plated on poly-lysine-coated 12 mm, #1.5H glass coverslips (ThorLabs). On day three, cells were washed in PBS and fixed in 100% methanol for 10 min at −20 °C. Coverslips were washed 3 times in 1x PBS, blocked (1x PBS, 200 mM glycine, 2.5% FBS) for 30 min at room temperature, then incubated in primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer for 1 h before being washed 3 times in 1x PBS and incubated for 1 h in secondary antibody solution. Following three additional washes, coverslips were mounted using Prolong Glass mountant with NucBlue stain. After sitting overnight at room temperature, coverslips were imaged using a Lionheart FX automated widefield microscope with a 20X Plan Fluorite WD 6.6 NP 0.45 objective. For each coverslip, a 7 by 7 grid of non-overlapping images was automatically taken. All images were manually assessed, and those with defects (debris, bubbles, out-of-focus, etc.) were filtered out. Images were analyzed using an automated pipeline using CellProfiler52. Briefly, cells were identified by their nuclei, and all those lacking CLMB-FLAG staining were removed. CLMB-FLAG signal was used to define the cell body, and all cells containing one or more fully saturated pixels in the CLMB-FLAG or CNA-GFP channels were removed. Pearson’s correlation coefficient between CLMB-FLAG and CNA-GFP was determined for each individual cell. >500 cells per condition were analyzed.

GFP-Trap coimmunoprecipitation

HEK293 cells were co-transfected (as described previously) with pcDNA5 encoding CNA-GFP and pcDNA5 encoding CLMBWT, CLMBIxITMut, CLMBLxVMut, CLMBT44A, or CLMBLxVMut+T44A. 24 h post-transfection, cells were washed 2X in PBS and frozen at −80 °C. Cells were lysed in 500 µL lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP−40), aspirated 5X with a 27-gauge needle, centrifuged at 16,000×g for 20 min at 4 °C and protein quantified via BCA. 100 mg total protein was removed as input. Lysates were adjusted to 0.5% NP−40 and 500 µg of protein incubated with pre-washed magnetic GFP-TRAP beads (ChromoTek gtma-20) for 2 h at 4 °C, turning end over end. Beads were magnetized, washed 3 times and eluted with 50 µL of 2x SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Samples were resolved via SDS-PAGE and visualized via immunoblotting with anti-flag antibodies to detect CLMB-FLAG and anti-GFP to detect CNA-GFP. Anti-GAPDH was used as a loading control for inputs. Immunoblots were imaged using a Licor Odyssey CLx and CLMB-calcineurin binding was quantified with Image Studio software. Co-purified CLMB was normalized using the following: (CLMBIP/CLMBInput)/GFP-CNAIP. Additionally, all values are displayed relative to CLMBWT, which is set at 1.

Protein expression and purification

CNA catalytic dead mutant H151Q with an N-terminal His6-CNA (residues 1–391) and CNB (residues 1–170) subunits were expressed using E. coli BL21(DE3) cells in Lysogeny Broth (LB) supplemented with 50 μg/mL ampicillin. Protein expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 18 °C. Cells were lysed using a Fisherbrand™ Model 505 Sonic Dismembrator, and lysates were centrifuged at 46,000×g at 4 °C for 45 min. The protein was purified by incubation with nickel-nitriloacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose resin (Qiagen) for 3 h at 4 °C. The resin was washed with 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, and 1 mM TCEP. A buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole, and 1 mM TCEP was used for elution. Calcineurin was further purified by SEC (Superdex® 200 Increase 10/300 GL) using Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and CaCl2 1 mM as the final buffer.

Fluorescence polarization binding assay

All FP measurements were performed on a multifunctional microplate reader (EnVision, Perkin Elmer) in black 384-well microplates (Corning, Cat No 3575) with 30 µL of the assay solution per well. 480-nm excitation and 535-nm emission filters were used for the FP measurements. In the FP saturation binding experiments, 5 nM FITC-labeled peptides were mixed with increasing concentrations of calcineurin in PBS buffer (pH 7.4) (commercially available tablets, Thermo Fisher #18912014) and 500 µM CaCl2 buffer (from 0 to 25 μM). Where indicated (Supplementary Fig. 3), these analyses were carried out at different pHs using a buffer with 20 mM Hepes pH 6.9, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM TCEP or a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, 500 μM CaCl2. FP values were plotted against the log of the protein concentrations, and the dissociation constant (apparent KD) was obtained from the resulting sigmoidal curve as analyzed in GraphPad Prism 10. Protein concentrations above 5 µM resulted in an upturn in fluorescence polarization signal, indicative of possible aggregation or artifacts; to maintain assay integrity, the considered concentrations were limited to ≤5 µM.

Fluorescence polarization competition assay

For the competitive binding assay, a mixture containing 5 nM FITC-labeled CLMB peptides and CNA/B (0.08 and 2 µM for CLMB vs PVIVIT experiments) was incubated with serial dilutions of unlabeled peptides for 30 min at room temperature. The FP values were determined, and the IC50 values, i.e., the concentrations required for 50% displacement of the FITC-labeled peptide, were calculated in GraphPad Prism 10. The Ki values of competitive inhibitors were calculated based on a previously reported method53, further adapted by ref. 54. Briefly, the relation of Ki and IC50 in competitive inhibition as applied to protein-ligand–inhibitor (P–L–I) interactions, can be summarized by the following equation:

Where L stands for the concentration of ligand, i.e., the FITC-labeled peptide used in the FP binding assay; and KD corresponds to the dissociation constant of the same FITC-labeled peptide resulting from the performed FP binding assay.

ITC measurements

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments were performed using an Affinity ITC from TA Instruments (New Castle, DE) equipped with an autosampler in a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, 500 µM CaCl2 at 25 °C. 40 μM protein solution in the calorimetric cell was titrated with 100 μM peptide solution using 0.5 µL injection in 200-sec intervals using stirring speed at 125 rpm. The resulting isotherm was fitted with a single-site model to yield thermodynamic parameters of ΔH, ΔS, stoichiometry, and KD using NanoAnalyze software (TA instruments). All results are representative of three independent experiments (n = 3).

NMR analyses

All NMR data were acquired using TopSpin3.4 (Bruker), processed with NMRPipe v.2020/2021 and analyzed with CCPNmr v355,56. Structural biology applications were compiled by the SBGrid consortium. Three-dimensional (3D) NMR experiments were conducted on a Bruker spectrometer operating at 600 MHz, equipped with TCI cryoprobes and z-shielded gradients. Samples of approximately180-μM 2H-, 13C- and 15N-calcimembrin in 20 mM Hepes pH 6.9, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM TCEP and 5% v/v 2H2O were used. The temperature was set to 25 °C. The NMR chemical shift data generated in this study have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB) under accession code [52641].

The NMR titration samples were prepared by adding unlabeled calcineurin A/B complex or unlabeled calcineurin subunit A into solutions of U-[15N]-labeled calcimembrin (50 μM) to reach a ratio of 0.5:1 (25 μM unlabeled calcineurin) or 1:1 (50 μM unlabeled calcineurin). Titration experiments featuring pCLMBLxVMut (40 µM) peptide with free CLMB (50 µM), and with calcineurin:CLMB at 1:1 and 0.5:1 stoichiometries were also performed. Two-dimensional (2D) spectra were acquired using SOFAST-HMQC on a Bruker 800 MHz Avance III spectrometer equipped with a TXO cryoprobe and z-shielded gradients57. Data was processed using NmrPipe and analyzed with CCPNmr. Secondary structure prediction was analyzed using TALOS-N58 and CheSPI24.

AlphaFold 3 modeling

Calcineurin-CLMB complex modeling was done using AlphaFold 3 on AlphaFold server27. Modeling was done using truncated CNA1-391, CNB, and two copies of CLMB, either unmodified or phosphorylated at Thr44. Zn2+ and Fe3+ (found in the calcineurin active site) and four Ca2+ ions (bound to CNB) were included in modeling. All images were generated in UCSF ChimeraX 1.859.

In vivo analysis of CLMB phosphorylation status

HEK293 FLIP-In TreX cells stably expressing CLMBWT-FLAG, CLMBIxITMut-FLAG, CLMBLxVMut-FLAG, or CLMBT44A-FLAG were transfected with empty vector or pcDNA5 FRT TO encoding CNA-GFP alongside empty vector or pcDNA5 FRT TO encoding CLMBWT-V5, CLMBIxITMut-V5, or CLMBLxVMut-V5. Protein expression was induced for 24 h with 10 ng/mL doxycycline, cells were washed 2X in PBS, and stored at −80 °C. Cells were lysed (50 mM Tris pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP−40, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1x Halt protease inhibitor cocktail) and resolved via SDS-PAGE and detected via immunoblotting.

In vitro CLMB phosphopeptide dephosphorylation

CLMBWT, CLMBIxITMut, and CLMBLxVMut phosphopeptides were synthesized by Vivitide, resuspended in 10 mM Tris pH 8.0 and dephosphorylated at 26 °C in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 µM MDCC-PBP (Thermo Scientific PV4406), 1 µM CaM (Millipore Sigma 208694-1MG)). Reactions were initiated by the addition of CLMB peptide to a final concentration of 100 nM. Reactions took place in a total of 50 µL in a Corning black 96-well vessel and were monitored continuously via fluorescence emitted by phosphate-bound MDCC-PBP (EX:425/ EM:460). Phosphate standards were used to convert fluorescence intensity to phosphate concentration. Data were analyzed using Prism software. Because the experimental design does not comply with the assumptions of standard kinetic models, reaction rates were obtained by fitting data to a single exponential model as an empirical description of the curves to facilitate comparison between experimental conditions.

In vitro RII phosphopeptide dephosphorylation

1 µM RII peptide was dephosphorylated at 26 °C in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 µM MDCC-PBP (Thermo Scientific PV4406), 100 nM calmodulin, 10 nM calcineurin, and CLMB peptide at the indicated concentrations (Millipore Sigma 208694-1MG)). Reactions were initiated by adding Ca2+ and CaM to their final concentrations. Reactions took place in a total of 50 µL in a Corning black 96-well vessel and were monitored continuously via fluorescence emitted by phosphate-bound MDCC-PBP (EX:400/EM:460). Phosphate standards were used to convert fluorescence intensity to phosphate concentration.

Kinetic modeling

Dephosphorylation data were fit by simulation and non-linear regression using Kintek Explorer™. Sigma values for each individual replicate were obtained using the double exponential afit function. All replicates were simultaneously fit to the models described in Supplementary Figs. 8a, b. Curve offsets were capped at a maximum offset of 50 nM. Substrate concentration was allowed to vary by 15% during fitting. Initial parameter values were chosen based on previously published rates, when available. The final offset and initial substrate concentration values for each curve, along with fitting information, are shown in Supplementary Tables 1–3. Final graphs display averaged (n ≥ 5) phosphate released at each timepoint with the corresponding fit. Simulated data were exported using 200 simulation steps and plotted using GraphPad Prism.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using Graphpad Prism version 10.2.2. All data is displayed as representative images or mean values with standard deviation error bars unless otherwise noted. All data represent three independent experiments unless otherwise indicated in the figure legends. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with corrections for multiple comparisons as indicated.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All original uncropped scans of immunoblots, immunofluorescence images, and AlphaFold predictions can be accessed at Mendeley Data [https://doi.org/10.17632/6kp379tsv4.1]60. Additional source data are provided with this paper. Plasmids and reagents will be shared upon request. The NMR chemical shift data generated in this study have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB) under accession code [52641]. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Bootman, M. D. & Bultynck, G. Fundamentals of cellular calcium signaling: a primer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 12, a038802 (2020).

Ulengin-Talkish, I. & Cyert, M. S. A cellular atlas of calcineurin signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 1870, 119366 (2023).

Aramburu, J., Rao, A. & Klee, C. B. Calcineurin: from structure to function. Curr. Top. Cell Regul. 36, 237–295 (2000).

Grigoriu, S. et al. The molecular mechanism of substrate engagement and immunosuppressant inhibition of calcineurin. PLoS Biol. 11, e1001492 (2013).

Roy, J. & Cyert, M. S. Identifying new substrates and functions for an old enzyme: calcineurin. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 12, a035436 (2020).

Brauer, B. L. et al. Leveraging new definitions of the LxVP SLiM to discover novel calcineurin regulators and substrates. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 2672–2682 (2019).

Sheftic, S. R., Page, R. & Peti, W. Investigating the human calcineurin interaction network using the piLxVP SLiM. Sci. Rep. 6, 38920 (2016).

Tsekitsidou, E. et al. Calcineurin associates with centrosomes and regulates cilia length maintenance. J. Cell Sci. 136, jcs260353 (2023).

Wigington, C. P. et al. Systematic discovery of short linear motifs decodes calcineurin phosphatase signaling. Mol. Cell 79, 342–358.e312 (2020).

Nakamura, T. et al. Overexpression of C16orf74 is involved in aggressive pancreatic cancers. Oncotarget 8, 50460–50475 (2017).

Meinnel, T., Dian, C. & Giglione, C. Myristoylation, an ancient protein modification mirroring eukaryogenesis and evolution. Trends Biochem. Sci. 45, 619–632 (2020).

Blanc, M., David, F. P. A. & van der Goot, F. G. SwissPalm 2: protein S-palmitoylation database. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009, 203–214 (2019).

Yap, M. C. et al. Rapid and selective detection of fatty acylated proteins using omega-alkynyl-fatty acids and click chemistry. J. Lipid Res. 51, 1566–1580 (2010).

Wang, Y., Windh, R. T., Chen, C. A. & Manning, D. R. N-Myristoylation and betagamma play roles beyond anchorage in the palmitoylation of the G protein alpha(o) subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37435–37442 (1999).

Dekker, F. J. et al. Small-molecule inhibition of APT1 affects Ras localization and signaling. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 449–456 (2010).

Percher, A. et al. Mass-tag labeling reveals site-specific and endogenous levels of protein S-fatty acylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 4302–4307 (2016).

Mesquita, F. S. et al. Mechanisms and functions of protein S-acylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 488–509 (2024).

Hornbeck, P. V. et al. 15 years of PhosphoSitePlus®: integrating post-translationally modified sites, disease variants and isoforms. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D433–D441 (2019).

Blumenthal, D. K., Takio, K., Hansen, R. S. & Krebs, E. G. Dephosphorylation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulatory subunit (type II) by calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase. Determinants of substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 8140–8145 (1986).

Perrino, B. A., Ng, L. Y. & Soderling, T. R. Calcium regulation of calcineurin phosphatase activity by its B subunit and calmodulin. Role of the autoinhibitory domain. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 7012 (1995).

Aramburu, J., Yaffe, M. B., López-Rodríguez, C., Cantley, L. C., Hogan, P. G. & Rao, A. Affinity-driven peptide selection of an NFAT inhibitor more selective than cyclosporin A. Science 285, 2129–2133 (1999).

Li, H., Zhang, L., Rao, A., Harrison, S. C. & Hogan, P. G. Structure of calcineurin in complex with PVIVIT peptide: portrait of a low-affinity signalling interaction. J. Mol. Biol. 369, 1296–1306 (2007).

Shen, Y. & Bax, A. Protein backbone and sidechain torsion angles predicted from NMR chemical shifts using artificial neural networks. J. Biomol. NMR 56, 227–241 (2013).

Nielsen, J. T. & Mulder, F. A. A. CheSPI: chemical shift secondary structure population inference. J. Biomol. NMR 75, 273–291 (2021).

Solyom, Z. et al. BEST-TROSY experiments for time-efficient sequential resonance assignment of large disordered proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 55, 311–321 (2013).

Hendus-Altenburger, R. et al. Molecular basis for the binding and selective dephosphorylation of Na+/H+ exchanger 1 by calcineurin. Nat. Commun. 10, 3489 (2019).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Shibasaki, F., Price, E. R., Milan, D. & McKeon, F. Role of kinases and the phosphatase calcineurin in the nuclear shuttling of transcription factor NF-AT4. Nature 382, 370–373 (1996).

Li, H., Rao, A. & Hogan, P. G. Structural delineation of the calcineurin-NFAT interaction and its parallels to PP1 targeting interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 342, 1659–1674 (2004).

Johnson, K. A. Fitting enzyme kinetic data with KinTek Global Kinetic Explorer. Methods Enzymol. 467, 601–626 (2009).

Klee, C. B., Draetta, G. F. & Hubbard, M. J. Calcineurin. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 61, 149–200 (1988).

Jespersen, N. & Barbar, E. Emerging features of linear motif-binding hub proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 45, 375–384 (2020).

Li, H., Rao, A. & Hogan, P. G. Interaction of calcineurin with substrates and targeting proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 21, 91–103 (2011).

Lee, S. et al. The optimized core peptide derived from CABIN1 efficiently inhibits calcineurin-mediated T-cell activation. Exp. Mol. Med. 54, 613–625 (2022).

Nguyen, H. Q. et al. Quantitative mapping of protein-peptide affinity landscapes using spectrally encoded beads. Elife 8, e40499 (2019).

O’Brien, K. T., Mooney, C., Lopez, C., Pollastri, G. & Shields, D. C. Prediction of polyproline II secondary structure propensity in proteins. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 191239 (2020).

Tubiana, J. et al. Funneling modulatory peptide design with generative models: discovery and characterization of disruptors of calcineurin protein-protein interactions. PLoS Comput. Biol. 19, e1010874 (2023).

Aramburu, J. et al. Selective inhibition of NFAT activation by a peptide spanning the calcineurin targeting site of NFAT. Mol. Cell 1, 627–637 (1998).

Li, S. J. et al. Cooperative autoinhibition and multi-level activation mechanisms of calcineurin. Cell Res. 26, 336–349 (2016).

Oliveria, S. F., Dell’Acqua, M. L. & Sather, W. A. AKAP79/150 anchoring of calcineurin controls neuronal L-type Ca2+ channel activity and nuclear signaling. Neuron 55, 261–275 (2007).

Li, H. et al. Balanced interactions of calcineurin with AKAP79 regulate Ca2+-calcineurin-NFAT signaling. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 337–345 (2012).

Church, T. W. et al. AKAP79 enables calcineurin to directly suppress protein kinase A activity. Elife 10, e68164 (2021).

Huang, W. Y. C., Boxer, S. G. & Ferrell, J. E. Jr. Membrane localization accelerates association under conditions relevant to cellular signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2319491121 (2024).

Johnson, J. L. et al. An atlas of substrate specificities for the human serine/threonine kinome. Nature 613, 759–766 (2023).

Li, M., Jiang, J. & Yue, L. Functional characterization of homo- and heteromeric channel kinases TRPM6 and TRPM7. J. Gen. Physiol. 127, 525–537 (2006).

Goldman, A. et al. The calcineurin signaling network evolves via conserved kinase-phosphatase modules that transcend substrate identity. Mol. Cell 55, 422–435 (2014).

Hirschi, A. et al. An overlapping kinase and phosphatase docking site regulates activity of the retinoblastoma protein. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1051–1057 (2010).

Jara, K. A. et al. Multivalency, autoinhibition, and protein disorder in the regulation of interactions of dynein intermediate chain with dynactin and the nuclear distribution protein. Elife 11, e80217 (2022).

Simonsen, S. et al. Extreme multivalency and a composite short linear motif facilitate PCNA-binding, localisation and abundance of p21 (CDKN1A). FEBS J. 292, 4314–4332 (2025).

Dinh, J. et al. The microprotein C16orf74/MICT1 promotes thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. EMBO J. 44, 3381–3412 (2025).

Uhlen, M. et al. Towards a knowledge-based Human Protein Atlas. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 1248–1250 (2010).

Stirling, D. R. et al. CellProfiler 4: improvements in speed, utility and usability. BMC Bioinform. 22, 433 (2021).

Cheng, Y. & Prusoff, W. H. Relationship between the inhibition constant (KI) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 22, 3099–3108 (1973).

Cer, R. Z., Mudunuri, U., Stephens, R. & Lebeda, F. J. IC50-to-Ki: a web-based tool for converting IC50 to Ki values for inhibitors of enzyme activity and ligand binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W441–W445 (2009).

Delaglio, F. et al. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 (1995).

Vranken, W. F. et al. The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins 59, 687–696 (2005).

Schanda, P., Kupce, E. & Brutscher, B. SOFAST-HMQC experiments for recording two-dimensional heteronuclear correlation spectra of proteins within a few seconds. J. Biomol. NMR 33, 199–211 (2005).

Shen, Y. & Bax, A. Protein structural information derived from NMR chemical shift with the neural network program TALOS-N. Methods Mol. Biol. 1260, 17–32 (2015).

Meng, E. C. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci. 32, e4792 (2023).

Cyert, M. A composite motif in calcimembrin/C16orf74 dictates multimeric dephosphorylation by calcineurin. Mendeley Data. https://doi.org/10.17632/6kp379tsv4.1 (2025).

Acknowledgements

M.S.C., D.A.B. and R.Y.M. are supported by NIH grant R35 GM136243. D.A.B. also acknowledges support from NIH grant T32 GM007276. H.A., J.C.R., S.Q. and T.V. acknowledge grant R01 GM136859 from NIH. We thank Norman Davey (ICR), Mardo Kõivomägi (NIH) and members of the Cyert and Arthanari labs, in particular Angela Barth and Sneha Roy, for helpful discussion. We are especially grateful to Rick Russel (UT Austin) for feedback on the kinetic modeling and thank Callie Wigington and Makena Pule for their early contributions to the project. We thank Ilya Bezprozvanny (UTSW) for suggesting the name calcimembrin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S.C., D.A.B., H.A. and J.C.R. conceived the studies. S.Q. and T.V. provided early NMR analysis of CLMB-calcineurin complexes. D.A.B., supervised by M.S.C., carried out experiments and analyzed data for Figs. 1, 2, 5 and Supplementary Figs. 2b, 6–9, and prepared figures. R.Y.M., supervised by M.S.C., carried out experiments and analyzed data for Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2a. J.C.R., supervised by H.A., carried out experiments and analyzed data for Figs. 3, 4 and Supplementary Figs. 3–5. T.V. carried out secondary structure analyses. D.A.B. and M.S.C. wrote the manuscript in consultation with H.A. and J.C.R.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jing Luo and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions