Abstract

Drug-associated stimuli (cues) can usurp potent control of behavior in individuals with substance use disorders; and these effects are often attributed to altered dopamine transmission. However, there is much debate over the way in which dopamine signaling changes over the course of chronic drug use. Here, we carried out longitudinal recording and manipulation of cue-evoked dopamine release in the core of the nucleus accumbens across phases of substance use in male rats. We show that, in a subset of individuals that exhibit increased cue reactivity and escalated drug consumption, this signaling undergoes diametrically opposed changes in amplitude, determined by the context in which the cue was presented. Dopamine evoked by non-contingent cue presentation (independent of the animal’s actions) increases over drug use, producing greater cue reactivity; whereas dopamine evoked by contingent cue presentation (dependent on the animal’s actions) decreases over drug use, producing escalation of drug consumption. Therefore, despite being in opposite directions, these dopamine trajectories each promote cardinal features of substance use disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Drug addiction is a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by cycles of irrepressible drug use, compulsive drug seeking, and high propensity to relapse following periods of abstinence1. Drug-associated stimuli (cues) are central to this condition as they can elicit behavioral, physiological and/or psychological states which are highly predictive of relapse and other clinical outcomes in substance use disorders2,3. Drug cues are learned through classical (Pavlovian) conditioning if they are reliable paired with drug receipt following successful drug-seeking actions4,5,6,7. Importantly, these cues acquire the ability to modify behavior when they are encountered outside the usual pairing context–a process known as Pavlovian-to-instrumental transfer8,9. For example, following chronic drug use in some individuals, a drug cue that was previously received as a result of drug-seeking actions (contingent presentation) can, in and of itself, initiate drug seeking when experienced in other situations (non-contingent presentation). This drug seeking may be driven by cue-induced craving5,10,11, or may be an automatized behavior elicited directly by the cue12.

Many contemporary theories of substance use disorders propose that enduring changes in mesolimbic dopamine transmission underlie aberrant behaviors13,14,15,16. However, there is no agreement on the manner or even the direction of these changes17. Dopamine in the nucleus accumbens core (NAcc) is proposed to play a role in producing drug “satiety”, thereby regulating drug intake18,19. Indeed, phasic dopamine release in the NAcc attenuates in animals that escalate their daily drug intake over time, but is maintained in animals with stable drug consumption20. In contrast, Incentive Sensitization Theory posits that dopamine release evoked by drug-associated environmental stimuli increases over the course of drug use to precipitate drug craving13,21. While, on the surface, these theories appear to be incompatible, it is important to recognize that they relate to different contingencies of stimulus presentation: Incentive sensitization pertains to reactivity to non-contingent stimulus presentation, whereas the role of satiety relates to stimuli when they are experienced following drug-taking actions. Importantly, drug-paired stimuli can serve different purposes depending upon their contingencies. When a drug-paired stimulus is presented in response to a drug-taking action (behavior contingent), it acts as a feedback signal indicating that drug delivery is imminent and no further action is required, whereas the same stimulus, presented independently of the subject’s actions (non-contingently) outside the active drug-taking context, acts as a cue (eliciting stimulus) to promote drug seeking. Moreover, differences in NAcc dopamine levels following contingent versus non-contingent presentation of drug-related stimuli have previously been reported22.

Here, we examined how dopamine release in the NAcc, evoked by non-contingent presentation of cues, evolves over the course of chronic drug use and withdrawal in male rats. We compare this trajectory to that for dopamine release to contingent cue presentation during active drug taking, and test the causal role of phasic dopamine signals in these contexts of cue presentation. Dopamine release elicited by non-contingent cue presentation increased over the course of chronic cocaine use. This trajectory is diametrically opposed to changes in dopamine evoked by the same stimulus when presented in response to a drug-taking action (contingent presentation). These opposing dopamine trajectories were observed concurrently in individual subjects, specifically those that escalated their cocaine consumption over this period. Furthermore, brief stimulation of NAcc dopamine terminals during non-contingent cue presentation augmented conditioned approach behavior, whereas stimulation during contingent presentation reduced drug intake. Therefore, these data indicate that dopamine mediates distinct hallmark features of addiction, with decreased NAcc dopamine to behavior-contingent stimuli producing increased drug consumption, and increased NAcc dopamine to non-contingent cues producing increased drug seeking.

Results

Drug-use history impacts non-contingent CS-elicited phasic dopamine transmission

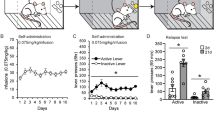

Male Wistar rats, implanted bilaterally with carbon-fiber microelectrodes in the NAcc (Supplementary Fig. 1) and a jugular catheter, were trained to receive intravenous cocaine in daily one-hour sessions. Behavioral chambers (Fig. 1A) were outfitted with two nose-poke ports, of which one was designated for drug-taking (side counterbalanced across animals); a house light and white noise signaled when the drug-taking port was active. A cocaine infusion (0.5 mg/kg) paired with a separate audiovisual conditioned stimulus (CS, nose-poke light and tone) was delivered following a nose-poke response in the active drug-taking port (Fig. 1B). Responses in the other port had no programmed consequences. Once animals reached the acquisition criterion (>10 responses in three consecutive sessions), they received an additional five baseline one-hour sessions (short-access, ShA; Fig. 1C). Immediately prior to the last of these sessions, non-contingent CS probe sessions were conducted in the drug-taking chamber, but outside the usual drug-taking context (nose-poke ports were visible but inaccessible, and house light and white noise were off). During these probe sessions, the CS was presented twice, separated by three minutes, independent of the animal’s behavior (non-contingently), and without drug delivery. A control group of animals, naïve to cocaine self-administration, also received probe sessions. Dopamine transients evoked by the non-contingent CS were measured with fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) in both groups. As previously shown following comparable self-administration training23, CS presentation produced significantly greater dopamine release in animals with self-administration experience than in naïve animals (Mann-Whitney, U = 26, p = 0.008; Fig. 1D). These data indicate that the capacity for the CS to elicit dopamine is dependent upon experience, rather than being an innate response. This finding is consistent with previous work demonstrating selectivity of dopamine release in the NAcc for a drug-paired cue compared to a neutral cue in cocaine experienced animals22.

A Operant chamber and (B) cue configuration for cocaine self-administration (SA) studies. A nose poke into the active port (red triangle) triggered presentation of a 20 s audiovisual conditioned stimulus (CS; duration shaded in yellow) and concurrent intravenous cocaine delivery (0.5 mg/kg). C Left: Experimental timeline for comparison of non-contingent CS-evoked dopamine in SA naïve vs. experienced subjects. Naïve subjects had no training, whereas experienced subjects received one week of short-access SA (ShA; 1-hr daily) after meeting the initial SA acquisition criteria (> 10 active pokes in 3 sessions). Non-Contingent CS elicited dopamine release was measured in probe sessions using fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV). Right: Detailed probe session timeline. Non-contingent CS presentations were delivered three minutes apart, independently of animal behavior and without drug delivery. Non-contingent CS audiovisual properties were identical to those of CS presentations during SA. D Average non-contingent CS-evoked dopamine responses in naïve and experienced subjects. FSCV dopamine signal time series (mean + SEM) with CS duration shaded in green, and quantification of average background-subtracted signals in the 7 s post-CS window (diamonds: individual subject means; bars: mean across subjects). Dopamine responses were larger in subjects with SA experience (n = 16, blue) compared to naïve subjects (n = 9, gray; two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test: U = 26, **p = 0.008). Where noted on figures and within legend, n indicates the number of biological replicates (subjects).

We next tested how dopamine, evoked by non-contingent CS presentation, evolves over extended drug use. Following five ShA baseline sessions (week 1), animals were split into two groups, receiving either ShA or six-hour long access (LgA) for ten additional self-administration sessions (weeks 2 and 3), with probe sessions (in the self-administration chamber) interleaved at the end of weeks 1 and 3 prior to a self-administration session (Fig. 2A). Unlike for ShA rats, first-hour drug consumption significantly increased over the weeks of cocaine self-administration in the LgA group (access x session interaction: F(9, 740) = 3.41, p = 0.0004; Fig. 2B. For absolute active/inactive pokes, see Supplementary Fig. 2a) as previously reported24. Behavior was similar for the subset of animals from which voltammetric recordings were obtained (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Notably, self-administration acquisition did not differ between ShA and non-LgA cohorts (Supplementary Fig. 2c), and days off at the end of a week did not impact drug intake on the subsequent session (Supplementary Fig. 2d). When measuring dopamine during probe sessions, we observed an increase in CS-evoked dopamine between week 1 and week 3 (main effect of week: F(1,55) = 11.43, p = 0.0013), which was significant in the LgA cohort (Šidák post-hoc test: p = 0.0002; Fig. 2C), but not in the ShA cohort which had fewer subjects (n = 6 versus n = 15). These data demonstrate that non-contingent CS-evoked NAcc dopamine release increases over the progression of drug use in males.

A Timeline of experimental paradigm designed to assess the impact of drug access history on non-contingent CS-evoked dopamine release. After initial training and one week of short access (ShA, baseline), subjects were assigned to either continue with ShA or receive long-access SA (LgA; 6 h sessions) for two additional weeks. Non-contingent CS-evoked dopamine release was measured in probe sessions (green squares with expanded timeline) occurring prior to the SA session, when subjects were not intoxicated, at the end of the ShA baseline (week 1, W1) and the end of week 3 (W3). ShA subjects at the W1 timepoint are the same as those in Fig. 1D. B Average first-hour drug-intake expressed as % change from ShA baseline (mean ± SEM across subjects) from ShA (blue, n = 31) and LgA cohorts (magenta, n = 66). Drug intake significantly increased over weeks 2 − 3 in the LgA cohort. Mixed Effects REML- main effect of drug-access: F(1,95) = 12.26,*** p = 0.0007; access x session interaction: F(9, 740) = 3.41, §§§p = 0.0004). C Average non-contingent CS-evoked dopamine responses from the first hour of SA in ShA and LgA cohorts. Signals recorded at the end of weeks that animals received ShA sessions are plotted in blue, and LgA sessions in magenta. Light green background indicates non-contingent CS duration. FSCV dopamine signal time series (mean + SEM across subjects), and quantification of the average background-subtracted signals in the 7 s post-CS window (diamonds: individual subject means; bars: mean across subjects). Non-contingent CS-evoked dopamine increased with drug access (Mixed-Effects REML-main effect of week: F(1,55) = 11.43, **p = 0.0013; main effect of drug access: F(1,55) = 5.11, *p = 0.028), and this effect was robust in LgA subjects (multi-corrected, two-tailed post-hoc comparison Šidák test: LgA W1 versus W3 ***p = 0.0002). Where noted on figures and within legend, n indicates the number of biological replicates (subjects).

Increased cue-evoked dopamine elevates drug seeking

We next tested whether this increase in cue-evoked dopamine release is modulated by psychological states analogous to cue-induced craving. To manipulate the psychological state without extending drug-intake history, we used a behavioral procedure that models changes in drug seeking during periods of drug abstinence. The frequency that animals perform an action to earn presentation of a previously drug-paired cue increases as a function of time since they last received the drug, a phenomenon termed ‘incubation of craving’25. We replicated this phenomenon as assessed using a within-animal incubation test26 (Fig. 3A) where responding for the CS in the absence of cocaine delivery was significantly greater at one month compared to one day following the last drug access session (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test: W = 78, p = 0.0005; Fig. 3B). We then analyzed behavior from the probe sessions that followed withdrawal, to test whether behavioral cue reactivity also underwent incubation. That is, whether CS-elicited drug seeking (measured in the probe test) incubated like the CS-reinforced drug seeking (conditioned reinforcement, measured in the incubation test). We quantified conditioned approach behavior from video recordings during probe sessions the day before the incubation test, where the CS was presented five times at three-minute intervals (Fig. 3A). CS-elicited approach scores were greater at one month compared to one day after the last drug access (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test: W = 86, p = 0.001; Fig. 3C), demonstrating that cue reactivity also incubates during withdrawal. However, the degree of this incubation did not significantly correlate with the incubation of CS-reinforced responding across individuals (r2 = 0.24, p = 0.147, n = 11). Notably, the approach score declined across subsequent CS presentations within the probe test, but was consistently higher for each of the five presentations after one month of withdrawal (Supplementary Fig. 3). Concomitant to this behavioral incubation in probe sessions, there was a robust increase in CS-evoked dopamine release (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test: W = 34, p = 0.016; Fig. 3D). This result demonstrates that the NAcc dopamine signal is affected by the psychological state of the individual and not necessarily simply a correlate of cumulative drug intake.

A Experimental timeline to assess non-contingent CS-evoked drug-seeking behavior and dopamine release during abstinence. Non-contingent CS elicited approach behavior and dopamine release were measured in probe sessions conducted at 1-day and 1-month abstinence (after LgA self-administration). In each probe, the CS was presented non-contingently, five times at 3 min intervals (light green box and expanded timeline). Incubation tests (lavender box) were also carried out one day after each probe session to assess conditioned responding for the CS. For all barplots in (B–D), connected points represent within-subject repeated measures, and bars indicate the mean across subjects (1-day: pink, 1-month: green). Gray diamonds connected by magenta lines indicate the subset of subjects from which successful voltammetry recordings were obtained. B Incubation test responses made for presentation of the CS alone (30 min session). Responding in the incubation test significantly increased between 1-day and 1-month abstinence (Two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test: n = 12 pairs, W = 78, ***p = 0.0005). C Average CS-evoked approach scores (mean across 5 x CS presentations from each subject) after 1-day and 1-month abstinence. Conditioned approach to each CS presentation was scored on a 0–5 scale (0 = no response, and 5 = orient, approach and interact with active port) and the per-subject mean across presentations calculated. Approach scores significantly increased between 1-day and 1-month abstinence (Two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test: n = 13 pairs, W = 86, ***p = 0.001). D Average non-contingent CS-evoked dopamine responses after 1-day (magenta) and 1-month (green) abstinence. Non-contingent CS duration indicated by a light green background. FSCV dopamine signal time series (mean + SEM [Dopamine](nM) across subjects), and quantification of the average background-subtracted signals in the 7 s post-CS window (diamonds: individual subject mean signals; bars: mean across subjects). Non-contingent CS-evoked dopamine release significantly increased between 1-day and 1-month abstinence (Two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test: n = 8 pairs, W = 34, *p = 0.0156). Where noted on figures, n indicates the number of biological replicates (subjects).

To test causality between these changes in cue-induced phasic dopamine signaling and drug-seeking behavior, we augmented CS-elicited dopamine after one day of abstinence to mimic the neurochemical changes observed during incubation of craving. Rats received bilateral microinjections into the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of a viral vector containing Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) behind a CaMKIIα promoter (Fig. 4A). This promoter was chosen based upon its unique expression in dopamine-containing cells in the VTA (LSZ unpublished observation) and, accordingly, it conferred high selectivity for, and efficiency in cells that positively label for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH). Specifically, 89.6% of all neurons labeled with the fluorescent marker for ChR2 (mCherry) were co-labeled with TH (2148 out of 2396 cells), and 90.7% of all TH-labeled cells were co-labeled with mCherry (2148 of 2366 cells; Fig. 4A). ChR2 was also expressed in some cells outside the VTA that do not express TH, most notably in the interpeduncular nucleus (IPN). However, these neurons do not project to the NAc, where the optical stimulation was administered. This approach permitted manipulation of dopamine release with high temporal precision (Fig. 4B). Animals were equipped with bilateral optic fibers into the NAcc (Supplementary Fig. 4) and underwent cocaine self-administration training. During the final week of LgA, self-administration sessions were interleaved with two counterbalanced non-contingent CS probe sessions, one with CS presentation alone, and one with stimulation (6 pulses, 30 Hz, 10 mW) during CS presentation (Fig. 4C). Conditioned approach was significantly more robust in stimulated than unstimulated sessions in ChR2-expressing animals, but not in controls (virus x stimulation interaction: F(1,10) = 8.78, p = 0.014; Fig. 4D), establishing a causal role for dopamine. Together, these data indicate that the progressive elevation of cue-evoked NAcc dopamine, across phases of the addiction cycle, increases cue-induced drug seeking in male rats.

A ChR2 expression. Left: Schematic depicting AAV1-CAMKIIα-ChR2-mCherry injection into the VTA. Middle: Representative images of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, green) and mCherry expression (magenta) in VTA cell bodies (10 x magnification, top row) and NAcc axon terminals (60 x magnification, bottom row). Right: Selectivity of ChR2 expression in dopamine neurons estimated by counting overlap between TH + and mCherry + cells in the VTA (n = 3 subjects, 2 slices per subject). B ChR2 functionality. Left: Schematic of NAcc brain slice FSCV setup with both optical and electrical stimulation (n = 6 subjects, 13 brain slices, 18 recording sites). Right: Representative pseudo color plots and corresponding dopamine traces and cyclic voltammograms (inset) elicited by optical and electrical stimulation. Pseudo color plots show current changes across the range of applied voltages (Eapp, y-axis) over time (x-axis). C Experimental timeline for testing the causal influence of non-contingent CS-elicited dopamine release on conditioned approach behavior. CS-evoked conditioned approach was measured in both stimulated and unstimulated (control) probe sessions in a new cohort of animals. In stimulated probes (expanded view in cyan), non-contingent CS presentation was paired with brief optogenetic stimulation, and in unstimulated probes (expanded view in gray), animals were tethered but no stimulation was delivered. Each probe session consisted of five CS presentations, occurring at 3 min intervals. This procedure was carried out in both ChR2 (expressing AAV1-CAMKIIα-ChR2-mCherry) and mCherry controls (expressing AAV1-CAMKIIα-mCherry). D Average non-contingent CS-evoked approach behavior from stimulated (cyan hexagons) and unstimulated (gray circles) probe sessions from each subject (mean across five CS presentations, mCherry group n = 5, ChR2 group n = 7). Lines connect within-subject paired measures, and bars indicate the mean across subjects. Conditioned approach was significantly more robust in stimulated sessions in ChR2-expressing animals, but not in controls (Repeated Measures Two-Way ANOVA: virus x stimulation interaction: F(1,10) = 8.78, §p = 0.014; Two-tailed multi-corrected post-hoc comparison with Šidák test: ChR2- stimulated versus unstimulated, n = 7, **p = 0.004; mCherry- stimulated versus unstimulated, n = 5, n.s. p = 0.897). Where noted on figures and within legend, n indicates the number of biological replicates (subjects).

Cue reactivity co-varies with individual drug-consumption patterns

Thus far, we have treated drug-access groups homogeneously. However, individual differences in behaviors, such as drug consumption rates and craving27, are a hallmark of human substance use and can be observed in animal models. Therefore, we tested whether individual differences in the propensity to escalate drug consumption during LgA bore any relation to changes in cue reactivity. Following three to four weeks of LgA (Fig. 5A), we classified animals as ‘escalators’ or ‘non-escalators’ based upon linear regression of their (first-hour) daily cocaine intake over time, as previously described20. 40.9% (27/66) of animals fulfilled the criterion for escalator classification by progressively increasing their cocaine consumption across sessions, whereas the remaining animals (39/66) exhibited stable drug intake (Fig. 5B). Notably, when considering absolute intake (rather than percentage of baseline) escalators took less cocaine per session during ShA, caught up with non-escalators in the first week of LgA, and then surpassed them (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Similarly, in the subset of animals from which we obtained voltammetry data, intake was greater in escalators in weeks three and four (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Training histories did not differ between escalators and non-escalators (Supplementary Fig. 5C, D). When we analyzed CS-evoked approach behavior with respect to these groups, we found differential effects over drug-use history, with conditioned approach increasing over time in escalators but not in non-escalators (escalation group x week interaction: F(2,22) = 13.2, p = 0.0002; Fig. 5C). Indeed, there was a significant correlation between the change in approach score from the ShA baseline (LgA - ShA approach score) and the escalation slope across individual animals (r2 = 0.46, p = 0.003; Fig. 5D).

A Timeline of experimental paradigm designed to assess non-contingent CS-evoked dopamine release over the course of LgA. (same subjects as LgA cohort Fig. 1 plotted with respect to escalation group, with a subset of animals receiving an extra week of LgA). B Average first-hour drug intake in non-escalators (light magenta) and escalators (magenta) expressed as a percent change from the ShA baseline (mean ± SEM across subjects). The ShA baseline period (W1) is highlighted with a blue background. Mixed-Effects REML - session x escalation group interaction: F(14, 659) = 8.119, §§§§p < 0.0001. C Average non-contingent CS-elicited approach behavior from escalators and non-escalators. Connected points represent average approach responses from an individual subject, with color indicating escalation group (n = 11 non-escalators: light magenta, n = 8 escalators: magenta), and shape indicating whether voltammetry data was also obtained (diamonds: voltammetry subjects, circles: behavior-only). Bars indicate the mean across subjects at each time point (W1-ShA: light blue, W3-LgA: solid light magenta, W4-LgA: striped light magenta). Conditioned approach increased over weeks of LgA in escalators but not non-escalators (Mixed Effects REML - main effect of escalation group: F(1,19) = 6.47, *p = 0.0199; main effect of week: F (2, 22) = 7.56 **p = 0.0032; escalation group x week interaction: F(2,22) = 13.2, §§§p = 0.0002; Two-tailed multi-corrected post-hoc comparison with Šidák test: escalators W1 versus W3 ***p = 0.0006, and W1 versus W4 **p = 0.0012). D Correlation between escalation slope and change in CS evoked approach behavior (LgA Approach Score - ShA Approach Score) for each subject. Positive values indicate an increased approach response after LgA and negative values a decreased response (best-fit line for all subjects, n = 17, slope = 1.01, R² = 0.46; F(1,15) = 12.97;**p = 0.003). Individual points represent data from each subject, with color indicating escalation group (non-escalators: light magenta, escalators: magenta) and shape whether voltammetry data was also obtained (diamonds: voltammetry subjects, circles: behavior-only). Where noted on figures and within legend, n indicates the number of biological replicates (subjects).

Phasic dopamine release to non-contingent CS presentations also changed differentially over time between escalation groups, with dopamine release increasing in escalators but remaining stable in non-escalators (escalation group x week interaction: F(2,20) = 13.89, p = 0.0002, Fig. 6A, B), and correlating with the change in drug intake (Supplementary Fig. 5e). Notably, there was significantly greater dopamine release in escalators by week 3 (Fig. 6B), a time when the cumulative intake is no different between groups (all escalators: 1577 ± 51 total infusions, n = 24, all non-escalators: 1595 ± 59 total infusions, n = 35, p = 0.831, unpaired t test; voltammetry escalators: 1609 ± 63 total infusions, n = 8, voltammetry non-escalators: 1505 ± 62 total infusions, n = 11, p = 0.268, unpaired t test). These changes in CS-evoked dopamine significantly correlated with the concomitant change in CS-elicited approach (r2 = 0.70, p = 0.0003; Fig. 6C), consistent with the causal link between dopamine and conditioned approach that we demonstrated above. We sometimes observed a secondary peak at the CS offset, especially in weeks 3 and 4 (Figs. 2C, 6A). However, this signal did not correlate with the primary peak (r2 = 0.002, p = 0.785), approach score (r2 = 0.0007, p = 0.933), drug intake (r2 = 0.02, p = 0.463) or escalation (r2 = 0.05, p = 0.446). These data establish that male individuals who escalate their drug intake exhibit a corollary increase in NAcc dopamine release evoked by non-contingent cue presentation, producing consequent behavioral cue reactivity.

A Average non-contingent CS-evoked dopamine traces measured by FSCV (mean ± SEM across subjects) from escalators (top row) and non-escalators (bottom row). Signals recorded at the end of the ShA baseline period (W1) are represented in blue, and after LgA (W3 & W4) in magenta. The 20 s non-contingent CS duration is highlighted in light green. B Quantification of average background-subtracted non-contingent CS-evoked dopamine signals from escalators and non-escalators in 7 s post-CS window (number of subjects for each group/timepoint as labeled in A). Individual diamonds represent the mean CS-evoked dopamine signal from each subject (non-escalators: light magenta, escalators: magenta), and bars indicate the mean across subjects. Gray lines connect repeated measures from the same subject. (Mixed Effects REML - main effect of escalation group: F(1,20) = 6.211, *p = 0.02; main effect of week: F(2,20) = 20.60 where, ****p < 0.0001; escalation group x week interaction: F(2, 20) = 13.89, §§§p = 0.0002), with non-contingent CS-evoked dopamine increased following LgA in escalators but remained stable in non-escalators (two-tailed multi-corrected post-hoc Šidák test: escalators W1 versus W3, ****p < 0.0001, and W1 versus W4 **p = 0.005). C Correlation between LgA non-contingent CS evoked dopamine release and change in CS-evoked approach behavior from each subject (gray best-fit line, n = 13, slope = 5.79, R² = 0.71, ***p = 0.0003). LgA dopamine release was measured in the last week of LgA. Diamonds represent data from each subject, with color indicating the escalation group (non-escalators: light magenta, escalators: magenta). Where noted on figures and within legend n indicates the number of biological replicates (subjects).

Diametric dopamine trajectories underlie different aspects of substance use disorders

Previous work has demonstrated that NAcc dopamine signals to cocaine-related cues can be contingency dependent22. Indeed, the rising trajectory of phasic dopamine release to non-contingent CS presentation in escalators in the current work opposes the trajectory we previously observed for behavior-contingent CS-evoked dopamine20. Because these observations appear to be counterintuitive, we examined phasic dopamine release during the self-administration sessions that interleaved the CS probe sessions in the same animals (Fig. 7A). Replicating our previous work20, NAcc dopamine release to behavior-contingent CS presentation significantly declined in escalators but not in non-escalators (escalation group x week interaction: F(2,24) = 4.41, p = 0.023; Fig. 7B, C). Accordingly, we found significant inverse correlation between changes in NAcc dopamine and the extent of escalation (r2 = 0.37, p = 0.008; Fig. 7D).

A Left: Experimental timeline illustrating timepoints when behavior-contingent CS-elicited dopamine release were measured. Recordings were performed during the cocaine self-administration sessions, which immediately followed non-contingent CS probe sessions in LgA subjects (yellow boxes indicate behavior-contingent CS recording sessions, and light green boxes the non-contingent CS probe sessions). Right: Expanded view of recording day timeline. Self-administration sessions began three minutes after the end of the non-contingent CS probe sessions. Dopamine release elicited by the CS following each active nose-poke (red arrows, detailed schematic in Fig. 1B) was measured and average responses for each subject calculated. The behavior-contingent CS audiovisual properties were the same as those of non-contingent CS measured in probe sessions; they only differed in the contingency of delivery. B Average behavior-contingent CS-evoked dopamine signals (FSCV) from escalators (top) and non-escalators (bottom) during ShA baseline at week 1 (blue) and the first hour of LgA at weeks 3 and 4 (magenta). The yellow background indicates the 20 s behavior-contingent CS duration. C Quantification of the average background-subtracted signals presented in (B) in the 7 s post-CS window (number of subjects per group/timepoint as labeled in B). Diamonds represent the average dopamine signal from each subject (non-escalators: light magenta, escalators: magenta), and bars indicate the average across subjects. Connecting lines link repeated measures from the same subject. Dopamine release significantly declined in escalators, but not non-escalators (Mixed Effects REML- main effect of week: F(2,24) = 10.76, ***p = 0.0005; escalation group x week interaction: F(2,24) = 4.41, §p = 0.023; Two-tailed multi-corrected post-hoc Šidák test: escalators W1 versus W3 **p = 0.0022, and W1 versus W4 ***p = 0.0002). D Correlation between individual subject LgA behavior-contingent CS-evoked dopamine release and escalation slope. Non-escalators and escalators indicated by light magenta and magenta diamonds, respectively. There was a significant negative correlation between behavior-contingent CS-evoked dopamine and escalation slope (gray best fit line for all subjects, n = 18, r2 = 0.37, **p = 0.008). Where noted on figures and within legend, n indicates the number of biological replicates (subjects).

To test the causal relationship between these neurochemical and behavioral variables, we once again turned to optogenetic stimulation of dopamine release, time-locked to CS presentation. This approach allowed temporally precise stimulation (6 pulses, 30 Hz, 5 ms, 10 mW) of phasic dopamine at the time of behavior-contingent CS presentation during the first hour of a LgA session (Fig. 8A). Stimulation significantly reduced drug consumption in ChR2-expressing escalators, but not in controls, nor in non-escalators (virus x escalation group x stimulation interaction: F(1, 25) = 15.96, p = 0.0005; Post-hoc Šidák comparison of stimulated versus unstimulated sessions in ChR2 escalators: p < 0.0001; Fig. 8B). Interestingly, stimulation in ChR2 non-escalators produced a modest increase in consumption (p = 0.0007; Fig. 8B). However, this effect was not selective for animals who received the ChR2 virus as there was not a significant virus x stimulation interaction for the non-escalators (F(1,15) = 0.0011, p = 0.97; Fig. 8B). Therefore, augmenting phasic CS-evoked dopamine during drug taking reduces drug consumption in animals that exhibit diminished CS-evoked dopamine signals, demonstrating that the loss of phasic dopamine plays a causal role in escalation. This effect is in stark contrast to the exact same stimulation paired with the CS during non-contingent presentation, where augmentation of dopamine increased cue reactivity. Collectively, these data demonstrate that the context of cue presentation dictates the directionality of changes in cue-evoked NAcc dopamine amplitude over the course of drug use, and is subject to individual differences (escalation group x week x contingency interaction: F(2,44) = 9.27, p = 0.0004, 3-way ANOVA). These changes underlie different aspects of substance use disorders in males: Reduced NAcc dopamine to behavior-contingent drug-related stimuli produced escalation of drug consumption, whereas increased NAcc dopamine release to non-contingent cue presentation produced elevated drug seeking.

A Experimental design for assessing the causal relationship between behavior-contingent CS-evoked dopamine release and levels of drug intake. In the second week of LgA, a new cohort of animals, expressing either ChR2-mCherry or mCherry-only (controls), underwent counterbalanced optogenetic probe tests. In stimulated probes (expanded view in purple box), a 6 pulse-30hz optical stimulation (10 mW) was paired with the onset of each behavior-contingent CS during the first hour of self-administration, whereas during unstimulated probes, animals were tethered but no stimulation was delivered. B Left: Average cumulative cocaine intake (mean + SEM across subjects) during the first hour of self-administration during stimulated (purple) and unstimulated control (gray) probe sessions (top: ChR2, bottom: mCherry controls). Data from escalators and non-escalators plotted side by side. Right: Average Cocaine intake (expressed as % ShA Baseline intake) during stimulated (purple) and unstimulated control (gray) probe sessions (left panel: mCherry controls, right panel: ChR2) in escalators and non-escalators. Bars indicate the mean across subjects for each group, and connected points indicate repeated measures from individual subjects (circles represent unstimulated controls and triangles stimulated probes). Stimulation significantly decreased drug consumption in ChR2 escalators and produced a modest but significant increase in drug consumption in ChR2 non-escalators, while having no impact in mCherry controls. (Repeated Measures 3-Way ANOVA: virus x escalation group x stimulation interaction: F(1, 25) = 15.96, §§§p = 0.0005. Follow-up Repeated Measures 2-Way ANOVA in ChR2 subjects: escalation group x stimulation interaction: F(1,15) = 104.8, §§§§p < 0.0001; two-tailed multi-corrected post-hoc comparison with Šidák test:comparison between stimulated versus and unstimulated sessions in ChR2 escalators, ****p < 0.0001, and ChR2 non-escalators, ***p = <0.0007. Follow-up Repeated Measures 2-Way ANOVA in mCherry subjects: escalation group x stimulation interaction, F(1,10) = 0.623, n.s. p = 0.45; main effect of stimulation, F(1,10) = 3.06, n.s. p = 0.11; main effect of escalation group, F(1,10) = 3.92, n.s. p = 0.076).

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that phasic dopamine release in the NAcc, to non-contingent presentation of drug-related stimuli, increases following drug experience and has a causal role in producing drug-seeking behavior. These experience-dependent changes in dopamine differ between subjects. Concomitant increase in neurochemical and behavioral reactivity to drug cues is exhibited by individuals that escalate drug consumption, but not by those that maintain stable drug intake. Moreover, in those individuals that escalate their drug intake, the dopamine signal to behavior-contingent stimulus presentation during drug taking also changes with experience, but in the opposite direction (i.e., decreases), causing the escalation. Thus, NAcc dopamine release to drug-related stimuli is dynamic over the history of drug use in a subset of individuals, but the directionality of change depends on how the stimulus is encountered. This divergence of NAcc dopamine signaling is parsimonious with differences in dopamine levels following contingent versus non-contingent stimulus presentation previously observed following significant cocaine self-administration experience22. These studies highlight the importance of the stimulus-presentation context in determining and interpreting the neurobiological substrates underlying behavior elicited by drug-associated stimuli. Accordingly, the results shed light on why there is so much variability in mesolimbic dopamine in humans diagnosed with substance use disorders across experimental designs17—that is, dopamine increases in some contexts and decreases in others, with both effects contributing to the symptoms of substance use disorders.

This new insight into dopamine dynamics over different epochs of substance use and, in particular, the timing and longitudinal trajectories of these signals, provides clarity as to how seemingly incompatible theories of substance use disorders can co-exist. One conceptual framework on the regulation of drug consumption has linked dopamine in the NAcc to drug satiety, with elevated dopamine levels providing negative feedback on subsequent drug taking18,19. The current data advance this model by demonstrating a causal role for phasic dopamine in regulating drug consumption, where discrete bouts of activity consisting of just a few action potentials can have potent inhibition of subsequent drug intake. Moreover, these data identify how decreased NAcc dopamine release during drug intake, observed in a subset of animals, produces escalation of drug consumption in those individuals. However, this framework provides no obvious insight into neurochemical changes that take place in response to non-contingent stimulus presentation and their impact on drug craving. In contrast, the central tenet of the Incentive Sensitization Theory is that the release of dopamine following cue presentation attributes incentive value to that stimulus, and this signaling is augmented following chronic drug use13,21. The behavioral and neurochemical phenotypes we observed related to non-contingent cue presentation align well with this theory, providing concrete evidence for several of its critical predictions. Specifically, we demonstrate that cue-evoked dopamine in the NAcc increases over the history of substance use, it does so with the most robust changes in individuals that exhibit the strongest proxies of craving and in states that enhance craving, and it is sufficient to elevate craving-like behavior in and of itself. Nonetheless, we cannot conclude unequivocally that these empirical data are mechanistically explained by the theory, as it is still possible that dopamine is operating purely as a teaching signal rather than invigorating the psychomotor activation to the cue presentation per se. That is, our data are unable to discern whether NAcc dopamine maintains conditioned responding to multiple presentations of the stimulus by directly attributing incentive salience or by preventing extinction of the association. This distinction is subtle and is seldom tenable from empirical data, but is conceptually important for a full understanding of the role that dopamine plays in addiction. Collectively, the current data provide an important perspective into the multidimensional role of NAcc dopamine in drug use that is not explained by any single contemporary theory of substance use disorders.

Another theory on mesolimbic dopamine function is the signaling of reward prediction errors, evaluating environmental stimuli or actions that may provide prescience on future outcomes28. However, the overall pattern of dopamine signaling in the current study is somewhat confusing in the context of prediction errors. In particular, contingent stimulus presentation, following a successful action to obtain the drug, would intuitively be characterized as a fully expected outcome, and yet dopamine signals at this time persist well beyond the point when animals exhibit reliable discriminative behavior (Supplementary Figs. 2a, 5a). This effect has consistently been observed across all studies of phasic dopamine release during cocaine self-administration20,23,29,30,31. Whether this observation is specific to substance use is unclear, since the experimental design is sufficiently different from most investigations of phasic dopamine with natural reinforcers to be able to extrapolate. In the context of prediction errors, this persistent signal to the non-contingent stimulus presentation could potentially play a feed-forward effect on reinforcement akin to that described by Redish for responses to the drug itself32. To follow this line of reasoning further, one could question whether differences between escalators and non-escalators reflect differences in learning. The pattern of dopamine signaling in escalators–where dopamine decreases to contingent (expected) stimulus presentations, and increases to non-contingent (unexpected) stimulus presentations–seems, on the surface, to comport to a prediction-error model; but, again, these changes take place well after discriminative behavior has been established, a traditional proxy of the window of learning. One provocative observation relates to the differences between escalators and non-escalators. In the current work, we observed dynamic changes in dopamine signaling in escalators (up to contingent, down to non-contingent stimuli), but relatively stable dopamine signals in non-escalators. This pattern is reminiscent of mesolimbic dopamine signaling patterns in sign- and goal-tracker rats during Pavlovian conditioning, with dynamic changes in sign trackers but relatively stable signals in goal trackers33. Sign- and goal-tracking conditioned responses are thought to reflect different types of associative learning and underlying computational mechanisms34. Individual differences in the propensity to exhibit one conditioned response over the other have been linked to addiction liability34,35, and the expression of some36 but not all37 features of addiction following chronic drug use. Therefore, it is intriguing to speculate that escalators and non-escalators also adopt different cognitive processes.

The current research focused on the mesolimbic dopamine system or, more specifically, dopamine transmission in the core of the nucleus accumbens. However, there is also considerable evidence for a role in substance use for dopamine transmission in other parts of the brain, including the dorsolateral striatum, where it has been implicated in the development of aberrant habits15. While the current work did not address this region, we have previously observed an interesting relationship between phasic dopamine signals in the NAcc and those in the dorsolateral striatum in early substance use31. Further research on phasic dopamine release in the dorsolateral striatum across different substance-use-related behaviors will likely help to bridge theories on drug habits to provide a more integrative view on dopamine’s multimodal role in addiction.

The behavioral model used in this study permits a granular analysis of the neurochemical regulation of substance use, while maintaining relevance to clinical neuroscience. It employs voluntary drug intake where subjects exhibit escalation of consumption with repeated use25 which, like with human substance use27, is subject to individual differences20. Using this approach, we observed systematic changes in drug-cue reactivity, a process that significantly predicts human drug-use and relapse outcomes2,3. Importantly, it is well established in humans that drug-paired cues can elicit dopamine release38 and produce craving5,10,11. Our data replicate each of these findings, demonstrate how they evolve with substance use, and establish a causal link between them. We also observed a relationship between dopamine release to non-contingent cue presentation and ‘incubation of craving’. This behavioral phenomenon was first observed in humans39, formally characterized in rodents25 and subsequently revisited in clinical populations where physiological correlates have been successfully measured40.

A key clinical implication of the current results reinforces the importance of tailoring potential therapeutics for substance use disorders to the phase of drug use. Treatments that have direct or downstream effects on dopamine release should be better suited to combating either active drug use or relapse, depending on whether they increase or decrease dopamine transmission, respectively. Accordingly, clinical studies with levodopa (which increases dopamine) show that its efficacy depends on the baseline status of the patient, with promising effects only on those with active drug use at the start of treatment41. Therefore, the current findings dovetail with existing literature in human subjects and, through the benefits of a model system, are able to provide several unique insights into the neurobiological regulation of substance use.

A caveat of the current work is that it was exclusively performed in male subjects, as was standard practice of the field when the research began. While we have discussed concurrence between our work and the clinical literature, some of which was conducted in females, we would be remiss in assuming that the current findings generalize across sexes until the dopamine dynamics have been tested directly in females (see ref. 42 for discussion on discrepant mechanisms despite uniform behavior). Nevertheless, the nuanced clinical population to which this work is most directly applicable—males living with cocaine use disorder—is quite substantial, and resulted in 2% of all deaths in males aged between 15 and 49 years in the USA in 201943.

Overall, we have demonstrated that phasic dopamine release in the NAcc. evoked by drug-related stimuli, changes dynamically over the course of cocaine use in a subset of male subjects. These individuals exhibit consequential behaviors that model core symptoms of substance use disorders. Remarkably, the changes in dopamine signaling are diametrically opposed between substance-use contexts. Dopamine release in the NAcc to drug cues encountered non-contingently increases to produce elevated cue-evoked craving. Whereas dopamine release in the NAcc to stimuli presented as a result of drug-seeking behavior decreases, conferring increased drug consumption.

Methods

Subjects

All animal use was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and surgical procedures were performed under aseptic conditions. A total of 217 adult male Wistar rats (Charles River, Raleigh, NC) weighing 300–350 g were used in these studies. Rats were pair-housed prior to surgery and kept on a 12 h light/12-h dark cycle (lights on at 0700) with controlled temperature and humidity, and food and water available ad libitum. Following surgery, animals were housed individually.

Thirty-one rats completed behavioral training in the short-access (ShA cohort) and 66 in the long-access (LgA) cohort. Successful voltammetry recordings were obtained from at least one experimental timepoint in 17 ShA animals and 30 LgA animals. Thirteen subjects that completed LgA and maintained electrode functionality subsequently underwent incubation of craving behavioral studies during abstinence, and paired voltammetry recordings were obtained from seven of these animals. Thirty-four rats completed the optogenetics studies.

Approximately 20% of subject attrition was due to head cap loss or catheter failure during the post-surgery recovery period, prior to beginning experimentation. The remainder of subjects dropped out of the study after experimentation began due to head cap loss, electrode failure, catheter failure or rejection, lack of viral expression, or in rare instances, failure to acquire self-administration. In all cases, the number of subjects reported, n, equals the number of biological replicates (subjects) included in the dataset.

Surgery

For dopamine recording studies, chronically implantable carbon fiber microelectrodes, constructed as previously described44,45, were lowered unilaterally or bilaterally into the nucleus accumbens core (NAcc)46 (AP: + 1.3 mm, ML: ± 1.3 mm, DV:− 7.2 mm) using a stereotaxic frame and secured with dental acrylic (Ortho-Jet, Lang Dental, USA). After two weeks of post-operative recovery, rats underwent a second surgical procedure and were outfitted with indwelling intravenous jugular catheters, then allowed to recover for at least one week before initiating cocaine self-administration training. During this recovery period, and prior to days off from self-administration, catheters were backfilled with a viscous 60-% polyvinylpyrrolidone-40 (Sigma Aldrich, USA) solution, containing 20 mg/mL of gentamicin (40 mg/mL; Fresenius Kabi, USA), and 1000 IU/mL of heparin (20,000 IU/mL; Fresenius Kabi, USA) to prevent formation of blood clots. Otherwise, catheters were flushed daily with saline or 80 IU/mL of heparinized (1000 IU/mL; Fresenius Kabi, USA) saline as needed, to maintain catheter patency throughout experimentation.

For optogenetic studies, rats first underwent catheter implantation surgery (as described above), and following one week of recovery underwent intracranial surgery in which they were bilaterally injected with AAV1-CAMKIIα-ChR2-mCherry or AAV1-CAMKIIα-mCherry (1 µL, 1–3 × 1012 viral particles/mL; viral vectors were made and provided by Dr. Larry Zweifel, Univ. of Washington) into the VTA (AP: − 6.35 mm, ML: ± 0.5 mm, DV: − 8.5 mm; 32) and optical fiber stubs (1.25 mm stub diameter, 200 μm fiber diameter, Plexon Inc.) were implanted bilaterally into the NAcc (AP: + 1.3 mm, ML: ± 1.3 mm, DV: −7.0 mm; 32). After an additional week of recovery, rats began cocaine self-administration training. A minimum of three weeks elapsed between viral vector injections and optogenetic manipulation to allow for ample ChR2 expression.

Cocaine self-administration

Rats were trained to self-administer cocaine during daily one-hour (short-access, ShA) sessions in an operant chamber outfitted with a liquid swivel and containing two nose-poke ports, and a video camera (Honic HN-WD200ESL). During self-administration sessions, the illumination of a house light paired with white noise signaled the availability of the drug. A single nose poke into the active port elicited a 0.5 mg/kg cocaine infusion (fixed-ratio one schedule), accompanied by presentation of a 20-s audiovisual conditioned stimulus (CS, tone and nose-poke-port light), during which any additional nose-poke was without consequence (time out). Nose pokes into the inactive port at any time were without consequence. After meeting the acquisition criterion of performing three sequential sessions where 10 or more infusions were earned, animals received five additional daily ShA sessions to establish baseline intake. Animals were then divided into two drug access groups, each receiving the same number of sessions, but sessions differed with respect to the number of hours the animals had access to self-administer cocaine. The short-access (ShA) cohort received daily one-hour access for 10 additional sessions, while the long-access (LgA) group received six-hour access for 10 sessions. A subset of LgA animals received an additional five sessions (mirroring the duration of LgA used in our previous study)20. Between these periods (‘weeks’), animals received days off, which averaged 1.70 ± 0.08 (s.e.m.) days per week. Notably, relative drug intake compared to the previous session was not significantly impacted by these breaks (Supplementary Figs. 1c, 5d).

To assess individual differences in drug intake patterns observed in LgA animals, we used our previously validated method20 for separating escalators and non-escalators. Briefly, first-hour drug intake over sessions was analyzed using linear regression. When there was a significant, positive slope, the subject was classified as an escalator, and when this criterion was not reached, the subject was classified as a non-escalator. Escalators (n = 27) and non-escalators (n = 39) did not differ in their training histories (i.e., number of training days to reach criterion, number of days off; Supplementary Fig. 5c, d).

Assessment of drug-seeking behavior

Conditioned approach behavior was assessed in drug-free, probe sessions in the self-administration chamber at the end of weeks one, three and four, immediately prior to a self-administration session, or following a one-day or one-month period of abstinence. During probe sessions, the CS was presented non-contingently (experimenter-delivered) on two or five occasions, separated by three minutes, and dopamine was measured. Nose-pose ports were covered with clear self-adhesive tape to prevent entry, without obstructing perception of the cues. Therefore, animals were able to approach and make contact with the outside of the port and the covering tape but to mitigate extinction, were prevented from enacting a full operant response. Approach scores were assessed by video review by investigators that were blinded to dopamine response and escalator status at the time of the review. This assessment used a 0–5 scale. Scores were attributed as follows: 0 = no response; 1 = startled action to cue onset; 2 = head directed towards nose-poke port; 3 = body oriented towards nose-poke port; 4 = approach nose-poke port; 5 = interaction with the nose-poke port. The mean approach score across presentations in a session was calculated for each subject and used for subsequent analysis.

CS-reinforced drug-seeking was measured in separate, thirty-minute incubation tests occurring one day after non-contingent probe sessions during abstinence, where dopamine was not measured. These sessions were identical to self-administration sessions, except that nose-pokes into the active port elicited the CS alone, without the delivery of the drug (infusion pumps were off and infusion lines were backfilled with saline).

Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry

Behaviorally relevant stimuli elicit rapid changes in dopaminergic neuron firing, resulting in transient changes in dopamine release over the course of seconds, and requiring the use of a detection method with high temporal resolution. In this study, phasic dopamine release events were measured at carbon-fiber microelectrodes in the ventral striatum using FSCV44,45. Briefly, chronically implanted carbon-fiber microelectrodes were connected to a head-mounted voltammetric amplifier, interfaced with a PC-driven data-acquisition and analysis system (National Instruments, USA; TarHeel CV) through a commutator (Crist Instrument Co, Inc, USA; Dragonfly, Inc, USA) that was mounted above the test chamber. A potential was applied to the electrode as a triangular waveform such that it was linearly ramped from the initial holding potential (− 0.4 V vs Ag/AgCl) to a maximum voltage (1.3 V vs Ag/AgCl, anodic sweep), then returned to the holding potential (cathodic sweep). Each voltage scan lasted 8.5 ms, yielding a scan rate of 400 V/s. The holding potential was maintained between voltage scans. Scans were applied every 100 ms (10 Hz sampling). When dopamine was present at the surface of the electrode, it was oxidized during the anodic sweep to form dopamine-o-quinone (peak reaction detected at approximately + 0.7 V), which was reduced back to dopamine in the cathodic sweep (peak reaction detected at approximately − 0.3 V). The ensuing flux of electrons was measured as current and was directly proportional to the number of dopamine molecules that underwent electrolysis. Voltammetric data was band-pass filtered at 0.025–2000 Hz. The background-subtracted, time-resolved current obtained from each scan provided a chemical signature characteristic of the analyte, allowing resolution of dopamine from other substances47. Dopamine was isolated from the voltammetric signal by chemometric analysis using a standard training set44 based on electrically stimulated dopamine release detected by chronically implanted electrodes, and dopamine concentrations estimated on the basis of the average post-implantation sensitivity of electrodes.

Event-aligned dopamine signals were pre-processed by smoothing using a five-point sliding window average. Average background subtracted dopamine responses were obtained by subtracting the mean signal in the one second before CS onset from the mean signal in the seven seconds following CS onset20,31.

Optogenetics

To determine the causal influence of non-contingent CS-elicited dopamine release on conditioned approach behavior, we performed optogenetic manipulation of dopamine release during non-contingent probe sessions in the second week of LgA in subjects expressing AAV1-CAMKIIα-ChR2-mCherry (ChR2) or AAV1-CAMKIIα-mCherry (mCherry controls). During stimulation sessions, five non-contingent CS presentations were paired with a brief optogenetic stimulation (6 pulses, 30 Hz, 5 ms pulse width, 10 mW with a 465 nM LED; Plexbright Compact LED, Plexon Inc.) were delivered in 3 min intervals. In unstimulated control sessions, animals were tethered, and five non-contingent CS presentations were delivered without paired stimulation. Stimulated and unstimulated probe session order was counterbalanced across subjects and interleaved by at least two days of self-administration. Non-contingent CS-elicited approach behavior was scored for each non-contingent CS presentation as described above, and the average approach responses in stimulated and unstimulated sessions were compared.

To determine the influence of behavior-contingent CS-elicited dopamine release on drug intake, we carried out optogenetic stimulation during drug self-administration. This manipulation was limited to the first hour of the session to minimize carryover effects on drug-taking behavior. As in the previous experiment, both ChR2 and mCherry control subjects underwent counterbalanced test sessions (interleaved by at least two days of self-administration). In stimulated sessions, brief optogenetic stimulation (6 pulses, 30 Hz, 5 ms pulse width, 10 mW) was paired with behavior-contingent CS onset, and in unstimulated control sessions, animals were similarly tethered but no stimulation was delivered. The order of stimulated and unstimulated probe sessions was counterbalanced across subjects, and at least two days of self-administration interleaved the test sessions. The number of drug infusions earned in the one-hour manipulation period was recorded and compared within subjects between stimulated and unstimulated sessions.

Histology

Upon completion of experimentation, placements of electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 1), or optic fibers (Supplementary Fig. 4) and viral expression patterns were assessed. Animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (20 mg/kg) and transcardially perfused with saline, then 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed and postfixed in paraformaldehyde for at least 24 h, then serially transferred into 15-% and 30-% sucrose solutions before being frozen, and coronal sections were taken using a cryostat (Leica CM1850, Leica Inc.) held at −25 °C. In subjects with electrodes, recording sites were marked by electrolytic lesion prior to perfusion while under anesthesia. Brains from voltammetry studies were sectioned at 50 μm thickness and stained with cresyl violet to aid visualization of anatomical structures and electrolytic lesions. Brains from optogenetic studies were sectioned at 40 μm, and viral expression patterns and selectivity for dopamine neurons was assessed by immunohistochemistry. In some cases, placements of electrodes or optic fibers could not be obtained because lesions were not clearly visible, or animals lost head caps before perfusion.

Immunohistochemistry

Brain slices were treated with a blocking solution (phosphate-buffered saline containing 3-% normal donkey serum and 0.3-% Triton) for 1 h and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies to label cells containing tyrosine hydroxylase (anti-tyrosine hydroxylase monoclonal, 1:1000 Millipore, MAB318) and mCherry (anti-dsRed polyclonal, 1:1000; Clontech, 632496). Sections were then washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times for ten minutes each, and incubated for two hours at room temperature with fluorescent conjugated secondary antibodies (1:250 Alexa Fluor® 488 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Mouse IgG (H + L), 1:250 Cy™3 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L); Jackson Immunoresearch). Sections were washed in PBS three times for ten minutes each, slide-mounted, and cover-slipped with DAPI Fluoromount-G (SouthernBiotech). Fluorescent images of VTA cell bodies were taken using Keyence BZ-X710 (Keyence, Ltd., UK) under 10x magnification, and NAcc terminals under 60x magnification to assess virus and tyrosine hydroxylase expression, and optic fiber placement. Fluorescent cell counting was performed within the VTA using ImageJ on a total of six coronal, two slices each from three separate subjects.

Data exclusion criteria

In cases where the intravenous tubing, voltammetry cabling or optic fiber disconnected or became twisted enough to affect behavior, the issue was corrected, the session continued, but data from that session were excluded from analysis. During probe sessions, trials were excluded if the animal’s head was outside of the camera view. Voltammetric recordings were excluded if dopamine was undetectable at any point during the session, if electrical noise exceeded 0.2 nA, if recordings from multiple time points for a subject were not obtained, or when histology revealed that the electrode was misplaced. When two electrodes from the same subject met these criteria in a session, their signals were averaged for analysis. When voltammetry self-administration sessions were excluded, a second recording session was attempted two days later (i.e., following a regular self-administration session), when possible. For optogenetic experiments, subjects were excluded if histology did not confirm both optic fiber placement and bilateral viral expression in the nucleus accumbens core.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 10.0 for Mac OS (GraphPad Software, www.graphpad.com). For simple comparisons across separate groups or when some paired measures were missing at random, data were analyzed using two-tailed Mann–Whitney U tests. For simple comparisons between two conditions, fully paired datasets (i.e., all subjects had measurements in both conditions) were analyzed using two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank tests. Correlations were analyzed using linear regression across all subjects, with the significance of the slope assessed using a two-tailed test and goodness-of-fit reported as R².

For multi-factor repeated-measures designs, most datasets contained some missing values; in these cases, mixed-effects models were used. Mixed-effects models were fitted using Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) with subject as a random effect, and assuming a compound symmetry covariance matrix among all repeated measures within a subject and equal variance across time points48. Fully paired datasets with no missing values were analyzed using two-way or three-way repeated-measures ANOVAs, depending on the experimental design. For ANOVAs with repeated-measures factors containing more than two levels, the Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied to adjust for potential violations of sphericity, and epsilon (ε) values are reported where relevant.

For post hoc analyses, comparisons were organized into predefined logical families (e.g., all pairwise week-to-week comparisons within a drug-access group). Šidák correction was applied separately within each family to adjust p-values for multiple comparisons and control the family-wise error rate. All corrected post hoc p-values are reported as two-tailed.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Ed.): DSM-5. (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013).

Regier, P. S. et al. Sustained brain response to repeated drug cues is associated with poor drug use outcomes. Addict. Biol. 26, https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.13028 (2021).

Vafaie, N. & Kober, H. Association of drug cues and craving with drug use and relapse. JAMA Psychiat 79, 641–650 (2022).

Wikler, A. & Pescor, F. T. Classical conditioning of a morphine abstinence phenomenon, reinforcement of opioid-drinking behavior and “relapse” in morphine-addicted rats. Psychopharmacologia 10, 255–284 (1967).

Stewart, J., de Wit, H. & Eikelboom, R. Role of unconditioned and conditioned drug effects in the self-administration of opiates and stimulants. Psychol. Rev. 91, 251–268 (1984).

O’Brien, C. P., Childress, A. R., McLellan, A. T. & Ehrman, R. Classical conditioning in drug-dependent humans. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 654, 400–415 (1992).

Ehrman, R. N., Robbins, S. J., Childress, A. R. & O’Brien, C. P. Conditioned responses to cocaine-related stimuli in cocaine abuse patients. Psychopharmacology 107, 523–529 (1992).

LeBlanc, K. H., Maidment, N. T. & Ostlund, S. B. Repeated cocaine exposure facilitates the expression of incentive motivation and iduces habitual control in rats. Plos ONE 8, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061355 (2013).

Lamb, R. J., Schindler, C. W. & Pinkston, J. W. Conditioned stimuli’s role in relapse: preclinical research on Pavlovian- Instrumental-Transfer. J. Psychopharmacol. 233, 1933–1944 (2016).

Hodgson, R., Rankin, H. & Stockwell, T. Alcohol dependence and the priming effect. Behav. Res. Ther. 17, 379–387 (1979).

Meyer, R. E. & Mirin, S. M. The Heroin Stimulus, Implications for a Theory of Addiction. (Springer New York, NY, 1979).

Tiffany, S. T. & Carter, B. L. Is craving the source of compulsive drug use?. J. Psychopharmacol. 12, 23–30 (1998).

Robinson, T. E. & Berridge, K. C. The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain. Res. Rev. 18, 247–291 (1993).

Dackis, C. A. & O’Brien, C. P. Cocaine dependence: a disease of the brain’s reward centers. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 21, 111–117 (2001).

Everitt, B. J. & Robbins, T. W. Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1481–1489 (2005).

Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Fowler, J. S. & Tomasi, D. Addiction circuitry in the human brain. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 52, 321–336 (2012).

Leyton, M. What’s deficient in reward deficiency?. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 39, 291–293 (2014).

Suto, N., Ecke, L. E. & Wise, R. A. Control of within-binge cocaine-seeking by dopamine and glutamate in the core of nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology 205, 431–439 (2009).

Suto, N. & Wise, R. A. Satiating effects of cocaine are controlled by dopamine actions in the nucleus accumbens core. J. Neurosci. 31, 17917–17922 (2011).

Willuhn, I., Burgeno, L. M., Groblewski, P. A. & Phillips, P. E. M. Excessive cocaine use results from decreased phasic dopamine signaling in the striatum. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 704–709 (2014).

Robinson, T. E. & Berridge, K. C. The incentive-sensitization theory of addiction 30 years on. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 76, 29–58 (2025).

Ito, R., Dalley, J. W., Howes, S. R., Robbins, T. W. & Everitt, B. J. Dissociation in conditioned dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens core and shell in response to cocaine cues and during cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. J. Neurosci. 20, 7489–7495 (2000).

Phillips, P. E. M., Stuber, G. D., Heien, M. L. A. V., Wightman, R. M. & Carelli, R. M. Subsecond dopamine release promotes cocaine seeking. Nature 422, 614–618 (2003).

Ahmed, S. H. & Koob, G. F. Transition from moderate to excessive drug intake: change in hedonic set point. Science 282, 298–300 (1998).

Grimm, J. W., Hope, B. T., Wise, R. A. & Shaham, Y. Neuroadaptation. Incubation of cocaine craving after withdrawal. Nature 412, 141–142 (2001).

Theberge, F. R. et al. Effect of chronic delivery of the toll-like receptor 4 antagonist (+)-naltrexone on incubation of heroin craving. Biol. Psychiatry 73, 729–737 (2013).

George, O. & Koob, G. F. Individual differences in the neuropsychopathology of addiction. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 19, 217–229 (2017).

Dayan, P. and Abbott, L. F. Theoretical Neuroscience (2001).

Stuber, G. D., Wightman, R. M. & Carelli, R. M. Extinction of cocaine self-administration reveals functionally and temporally distinct dopaminergic signals in the nucleus accumbens. Neuron 46, 661–669 (2005).

Owesson-White, C. A. et al. Neural encoding of cocaine-seeking behavior is coincident with phasic dopamine release in the accumbens core and shell. Eur. J. Neurosci. 30, 1117–1127 (2009).

Willuhn, I., Burgeno, L. M., Everitt, B. J. & Phillips, P. E. M. Hierarchical recruitment of phasic dopamine signaling in the striatum during the progression of cocaine use. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 20703–20708 (2012).

Redish, A. D. Addiction as a computational process gone awry. Science 306, 1944–1947 (2004).

Flagel, S. B. et al. A selective role for dopamine in stimulus-reward learning. Nature 469, 53–57 (2011).

Clark, J. J., Hollon, N. G. & Phillips, P. E. M. Pavlovian valuation systems in learning and decision making. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 22, 1054–1061 (2012).

Saunders, B. T. & Robinson, T. E. Individual variation in resisting temptation: implications for addiction. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 1955–1975 (2013).

Flagel, S. B., Watson, S. J., Akil, H. & Robinson, T. E. Individual differences in the attribution of incentive salience to a reward-related cue: influence on cocaine sensitization. Behav. Brain Res. 186, 48–56 (2008).

Pohořalá, V., Enkel, T., Bartsch, D., Spanagel, R. & Bernardi, R. E. Sign- and goal-tracking score does not correlate with addiction-like behavior following prolonged cocaine self-administration. Psychopharmacology 238, 2335–2346 (2021).

Boileau, I. et al. Conditioned Dopamine Release in Humans: A Positron Emission Tomography [11C]Raclopride Study with Amphetamine. J. Neurosci. 27, 3998–4003 (2007).

Gawin, F. H. & Kleber, H. D. Abstinence symptomatology and psychiatric diagnosis in cocaine abusers. Clinical observations. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 43, 107–113 (1986).

Parvaz, M. A., Moeller, S. J. & Goldstein, R. Z. Incubation of cue-induced craving in adults addicted to cocaine measured by electroencephalography. JAMA Psychiat 73, 1127 (2016).

Schmitz, J. M. et al. A two-phased screening paradigm for evaluating candidate medications for cocaine cessation or relapse prevention: Modafinil, levodopa–carbidopa, naltrexone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 136, 100–107 (2014).

Nicolas, C. et al. Sex differences in opioid and psychostimulant craving and relapse: A critical review. Pharmacol. Rev. 74, 1190–140 (2022).

Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021). Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2024).

Clark, J. J. et al. Chronic microsensors for longitudinal, subsecond dopamine detection in behaving animals. Nat. Methods 7, 126–129 (2010).

Arnold, M. M., Burgeno, L. M. & Phillips, P. E. M. in Basic Electrophysiological Methods (eds. Covey, E. & Carter, M.) (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Paxinos, G. & Watson, C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates - The New Coronal Set. (Elsevier Academic, 2004).

Rodeberg, N. T., Sandberg, S. G., Johnson, J. A., Phillips, P. E. M. & Wightman, R. M. Hitchhiker’s guide to voltammetry: Acute and chronic electrodes for in vivo fast-scan cyclic voltammetry. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 8, 221–234 (2017).

Barr, D. J., Levy, R., Scheepers, C. & Tily, H. J. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. J. Mem. Lang. 68, 255–278 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Daniel Hadidi, Suhjung Janet Lee, and Hope C. Willis for technical support, and Andi Hart, Yavin Shaham, and Benjamin Saunders for feedback. This work was supported by awards from the US National Institutes of Health grant T32-DA007278 (L.M.B. & R.D.F.), F31-DA048562 (R.D.F.), R01-DA039687 (PEMP), R37-DA051686 (PEMP), R01-DA044315 (L.S.Z.), and the Balliol College-Dan Norman Fund Early Career Research Fellowship (LMB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: L.M.B., R.D.F., I.W., and P.E.M.P.; Methodology: L.M.B., M.E.S., S.B.E., S.G.S., I.W., L.S.Z., and P.E.M.P.; Investigation: L.M.B., R.D.F., N.L.M., and J.S.S.; Data analysis: L.M.B., R.D.F., and MCP; Funding acquisition: L.S.Z. and P.E.M.P.; Supervision: L.S.Z. and P.E.M.P.; Writing original draft: L.M.B., R.D.F., and P.E.M.P.; Writing review & editing: L.M.B., R.D.F., M.C.P., S.G.S., and P.E.M.P.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Marcello Solinas and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Burgeno, L.M., Farero, R.D., Murray, N.L. et al. Cocaine seeking and consumption are oppositely regulated by mesolimbic dopamine in male rats. Nat Commun 16, 9954 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64885-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64885-y