Abstract

Emerging evidence suggests that classical psychedelics may offer therapeutic potential for opioid use disorder (OUD) by alleviating key hallmarks such as altered reward processing and dependence. However, the mechanisms behind these effects remain unclear. Our data demonstrate that a single administration of the psychedelic psilocybin (PSI) reduces conditioned behavior and withdrawal induced by the opioid oxycodone (OXY) in male mice but not in females, and this effect is mediated via the 5-HT2A receptor (5-HT2AR). We show that the sex-specific attenuation of OXY preference is driven by 5-HT2AR activation in frontal cortex pyramidal neurons projecting to the nucleus accumbens (NAc). Additionally, PSI modulates epigenomic regulation following repeated OXY exposure and induces sex-specific NAc dendritic structural plasticity independently of 5-HT2AR. Notably, female frontal cortex and NAc show fewer changes at gene enhancer regions in response to PSI, repeated OXY, or combined PSI-OXY treatment compared to males, with the frontal cortex exhibiting more pronounced sex differences than the NAc at the epigenomic level. Together, these results provide new insights into the neural and epigenetic mechanisms of psychedelic-induced plasticity in OUD, while also highlighting sex differences in PSI’s modulation of reward pathways and its therapeutic potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Abuse of prescription drugs, particularly pain-relieving opiates such as oxycodone (OXY), has increased greatly in recent years. Despite their effectiveness in treating acute and chronic pain1,2, long-term use can lead to the development of complications such as tolerance, physical dependence, and opioid use disorder (OUD) in some individuals3,4,5. In 2021, OUD affected over 2.5 million adults in the United States but less than 25% received pharmacological treatment6. Additionally, while current pharmacotherapies for treatment of OUD exist, they specifically target the μ-opioid receptor (MOR) to reduce or block the effects of higher efficacy MOR agonists, rather than the underlying mechanisms behind maladaptive behaviors7. Examples of these pharmacotherapies include full and partial agonists, such as methadone and buprenorphine, respectively, and antagonists such as naloxone. Whereas opioid-based pharmacotherapies are effective for many, they solely target the opioid receptor system and can also cause physical dependence. Therefore, in considering translational perspectives towards the treatment of OUD, it is imperative to identify the molecular targets, cell signaling processes, and neural circuits governing the impact of opioids within the reward pathway, as opposed to a direct targeting of the opioid receptor system.

Classical psychedelics, such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), psilocybin (PSI) and 1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)−2-aminopropane (DOI), are compounds that produce profound changes in perception, sensory processes and cognition8,9. In the past decade, psychedelics have been studied as potentially transformative therapeutics for a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression and substance use disorders (SUDs), including tobacco and alcohol10,11, and most recently, opioids12. In survey studies assessing data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), it was found that use of PSI was associated with a 30% decrease in odds of developing an OUD13,14. Further, a recent observational study based on self-reports of naturalistic use of psychedelics and other drugs found that psychedelics were associated with a significant reduction in the consumption of other substances15. Notably, 96% of respondents met criteria for a substance use disorder (SUD) prior to using psychedelics, whereas only 27% did so after their psychedelic experience. Some of the most substantial reductions were observed among those with severe OUD. Despite these striking effects, their acute symptoms and potentially uncontrolled recreational use preclude the routine use of classical psychedelics in daily clinical practice. Additionally, while these studies represent an important step towards a greater understanding of the efficacy of psychedelics in the treatment of OUDs, more direct and mechanistic preclinical studies are required to evaluate the extent to which this association is causal.

The pharmacological profiles of classical psychedelics are complex8. However, based largely on previous work in rodent models16 along with findings from studies in healthy volunteers17,18, it is now widely believed that the primary molecular target responsible for the hallucinogenic properties of psychedelics involves activation of the serotonin (or 5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) 2 A receptor (5-HT2AR), particularly in pyramidal neurons of the frontal cortex. While this is widely evidenced, the extent to which psychedelic-induced activation of 5-HT2AR-dependent signaling is necessary for the post-acute, translationally relevant effects of psychedelics in rodent models remains a topic of significant debate. Previous findings using relatively selective antagonists, such as ketanserin and volinanserin (or M100907), suggest that pharmacological blockade of 5-HT2AR does not reduce PSI-induced structural plasticity in the frontal cortex or its antidepressant-like activity in rodents19,20. In contrast, gene manipulation studies have shown 5-HT2AR-dependent changes in frontal cortex dendritic spines following administration of DOI compared to vehicle21. This evidence for the role of 5-HT2ARs in psychedelic-induced dendritic structural plasticity in the frontal cortex and antidepressant-like effects has been further supported by studies using 5-methoxy-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT)22 and PSI23,24 in 5-HT2AR-KO mice and controls, respectively. Discrepancies in the role of 5-HT2AR in the post-acute effects of psychedelics may be related to pharmacodynamic factors, including their relative affinities for 5-HT receptor subtypes. For example, phenethylamines such as DOI primarily target 5-HT2Rs, including 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2CR, whereas tryptamines such as PSI also recruit signaling processes via 5-HT1ARs, among many other monoaminergic G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)8. Additionally, the region-specific expression of these receptors and their associated neuronal circuits may differentially influence behavioral outcomes. Most preclinical work on the therapeutic-related effects of psychedelics has focused on models of mood and stress disorders25 compared to the few studies indicating that 5-HT2AR blockade suppresses behavioral sensitization, and withdrawal symptoms in rodents treated with the opioid morphine26,27.

In the present study, we assessed the post-acute effects of a single exposure to PSI on opioid-seeking behavior and withdrawal symptoms, revealing sex-specific effects of PSI on both 5-HT2ARs in frontal cortical neurons as well as non-5-HT2ARs that differentially modulate epigenomic and synaptic plasticity in subcortical target regions.

Results

Sex differences in effect of PSI on unconditioned behaviors

To explore the potential role of 5-HT2AR in the post-acute effects of PSI on OUD models, we first tested its effect on head-twitch behavior (HTR), a mouse behavioral proxy for human psychedelic potential16,28. Treatment with all doses of PSI (0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mg/kg) induced a HTR effect that peaked during the first 30-min post injection, before decreasing steadily across time in both sexes (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Similar to previous findings with the phenethylamine psychedelic DOI29, analysis of the total 30-minute HTR showed that PSI elicited more HTR in female mice as compared to males (Fig. 1a). Since this difference was more evident at 1 mg/kg PSI (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1a), and considering that pre-administration of the 5-HT2AR antagonist volinanserin (0.1 mg/kg) fully blocked the effect of PSI (1 mg/kg) on HTR in both male and female mice (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1b), we selected this dose of the psychedelic PSI for the remainder of studies. Additionally, as expected, male and female mice did not show any HTR difference in the vehicle-treated groups (Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Fig. 1a, b).

a Dose-response effect of PSI on HTR behavior. HTR counts correspond to the first 30 min after injection with PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle in male (n = 6 per group) and female (n = 5-6 per group) wild-type mice (dose F [3,36] = 29.67, p < 0.001; sex F [1,36] = 16.27, p < 0.001; interaction F [3,36] = 3.94, p < 0.01). b Effect of pretreatment with the 5-HT2AR antagonist volinanserin (vol) (0.1 mg/kg) or vehicle 15 min prior to the administration of PSI (1 mg/kg) on HTR behavior. HTR counts correspond to the first 30 min after injection with PSI or vehicle in male (n = 6 per group) and female (n = 5-6 per group) wild-type mice (drug F [3,39] = 60.37, p < 0.001; sex F [1,39] = 8.89, p < 0.01; interaction F [3,39] = 9.00, p < 0.001). c Brain concentration of psilocin after a single administration of PSI (1 mg/kg) in male (n = 4-5 per group) and female (n = 5 per group) wild-type mice (time F [3,31] = 27.44, p < 0.001; sex F [1,33] = 0.16, p > 0.05; interaction F [3,31] = 0.68, p > 0.05). Arrow indicates time of administration of PSI. d Blood concentration of psilocin after a single administration of PSI (1 mg/kg) in male (n = 5 per group) and female (n = 4–5 per group) wild-type mice (time F [3,31] = 117.1, p < 0.001; sex F [1,33] = 0.85, p > 0.05; interaction F [3,31] = 1.07, p > 0.05). Arrow indicates time of administration of PSI. e and f Lack of effect of PSI on exploratory behavior in an open field. Behavior was tested 24 h after a single administration of PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle in male (n = 8 per group) and female (n = 5-6 per group) wild-type mice (e: time F [17,391] = 36.40, p < 0.001; drug F [1,23] = 0.09, p > 0.05; sex F [1,23] = 1.45, p > 0.05; interaction F [17,391] = 0.67, p > 0.05; see Supplementary Table 1 for additional statistical comparisons) (f: drug F [1,23] = 0.07, p > 0.05; sex F [1,23] = 0.23, p > 0.05; interaction F [1.23] = 0.0002, p > 0.05). g and h Lack of effect of PSI on dark-light choice test. Behavior was tested 24 h after a single administration of PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle in male (n = 6 per group) and female (n = 6 per group) wild-type mice (g: time F [2,60] = 12.99, p < 0.001; drug F [1,60] = 1.29, p > 0.05; sex F [1,60] = 1.06, p > 0.05) (h: drug F [1,20] = 1.98, p > 0.05; sex F [1,20] = 5.93, p < 0.05; interaction F [1,20] = 0.55, p > 0.05). i and j Lack of effect of PSI on exploratory preference during the novel-object recognition test. Behavior was tested 24 h after a single administration of PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle in male (n = 6 per group) and female wild-type (n = 5-6 per group) mice (i: preference F [1,20] = 110.0, p < 0.001; drug F [1,20] = 0.28, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,20] = 1.04, p > 0.05) (j: preference F [1,18] = 17.65, p < 0.001; drug F [1,18] = 0.005, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,18] = 0.001, p > 0.05) (i and j: sex F [1,38] = 2.26, p > 0.05; see Supplementary Table 2 for additional statistical comparisons). k and l Sex-specific effect of PSI on exploratory time during the novel-object recognition test. Behavior was tested 24 h after a single administration of PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle in male (n = 6 per group) and female (n = 5-6 per group) wild-type mice (k: exploration F [1,20] = 0.09, p > 0.05; drug F [1,20] = 0.55, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,20] = 0.001, p > 0.05) (l: exploration F [1,18] = 34.11, p < 0.001; drug F [1,18] = 5.45, p < 0.05; interaction F [1,18] = 0.21, p > 0.05) (k and l: sex F [1,38] = 6.67, p < 0.05; see Supplementary Table 3 for additional statistical comparisons). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA (a, b, c, d, f, h, i, j, k,l) and/or three-way ANOVA (e, g, i, j, k, l) (+p < 0.05, ++p < 0.01, +++p < 0.001, n.s., not significant) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, n.s., not significant). Data show mean ± s.e.m.

We next evaluated whether these sex differences on PSI-induced HTR were related to pharmacokinetic variations between male and female mice. Administration of PSI systemically (i.p.) allows for the compound to be metabolized into its active metabolite psilocin in order to cross the blood-brain barrier and elicit its neurobiological effects. Therefore, we tested the distribution of psilocin at different time-points in plasma and the CNS following PSI (1 mg/kg) administration in male and female mice, as compared to mock-injected (t = 0) control animals. Concentrations of psilocin were higher in brain samples as compared to blood in both sexes (Fig. 1c, d). Additionally, the absorption of psilocin was fast, and reached its maximal concentration during the first ~30 min in brain (Fig. 1c). However, no significant differences were observed in the half-life (t1/2) of psilocin in brain or plasma samples between male and female mice (Fig. 1c, d).

Similar to previous studies with DOI21, we measured unconditioned behaviors 24 h post-administration of PSI (1 mg/kg) to evaluate potential post-acute effects of this dose once the active component psilocin is fully metabolized (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Animals were tested for locomotor activity in a novel environment, as a model of exploratory behavior. We show that PSI did not produce any lasting locomotor effect at 24 h post-acute (Fig. 1e, f, and Supplementary Table 1). Additionally, our data indicate that there were no differences across sexes in the horizontal activity measure (Fig. 1e, f, and Supplementary Table 1). Next, a separate cohort of mice was tested in the light-dark box assay 24 h following PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle. Rodents generally prefer dark and small areas and are less likely to explore open or bright areas; therefore, we measured the amount of time spent in the light-zone as a conflict paradigm. Administration of PSI had no effect on the time spent in the light compartment (Fig. 1g). However, a sex-dependent effect was observed in total exploratory time, with female mice spending less time exploring than males (Fig. 1h).

Lastly, considering that, upon acute administration, psychedelics disrupt cognition and sensory processing8, we assessed the post-acute effects of PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle using a novel-object recognition test as a behavior model of cognitive performance (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Our data show that PSI administration did not affect novel-object recognition in male or female mice during the cognitive task (Fig. 1i, j, and Supplementary Table 2). In male mice, exploratory time was comparable between the PSI and vehicle groups (Fig. 1k). However, female mice exhibited both a post-acute enhancement by PSI (Fig. 1l) and a significant reduction in novel object exploration time compared to male animals (Fig. 1k, l, and Supplementary Table 3). Together, these data indicate that a single dose of PSI augments HTR in male and female mice acutely – with a higher response in the female cohort – whereas female mice exhibit reduced exploratory behavior compared to males in the light-dark box and novel object recognition tasks, suggesting sex-dependent differences in post-acute exploratory responses.

OXY-induced CPP in male and female mice

Conditioned place preference (CPP) is a rodent model that focuses on the rewarding aspects of the drugs through context-related conditioning and memory associated with drug use30. This preclinical model is of interest because pairing classical conditioning using a drug of abuse and a specific context highlights the importance of environmental behavioral history in SUD, which commonly plays a role in relapse. Male and female mice were habituated to CPP chambers (day 1), and then underwent OXY (3 mg/kg) or vehicle conditioning for three days (days 2-4). One day after the last conditioning session (day 5), animals were allowed to explore freely between the three compartments for 15 min, and time spent on each side was recorded (Fig. 2a). As expected, based on previous reports27, we found that both sexes showed an increased preference for OXY compared to vehicle-treated animals, with no differences between male and female mice (Fig. 2b).

a Timeline of the experimental design. b OXY-induced CPP in male (n = 56-63 per group) and female (n = 41-47 per group) mice (drug F [1,203] = 92.78, p < 0.001; sex F [1,203] = 0.10; p > 0.05; interaction F [1,203] = 0.88, p > 0.05). c PSI reverses OXY-induced CPP post-acutely in male wild-type mice (n = 22-26 per group) (OXY F [1,87] = 0.22, p > 0.05; PSI F [1,87] = 0.02, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,87] = 7.76, p < 0.01). d PSI does not reverse OXY-induced CPP post-acutely in female mice (n = 20-27 per group) (OXY F [1,93] = 12.72, p < 0.001; PSI F [1,93] = 0.28, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,93] = 0.05, p > 0.05). e, f PSI facilitates extinction of OXY preference in male wild-type mice (n = 26 per group). Mice conditioned with OXY were assessed for within-subject changes on day 5 (e: pre-vehicle, red square; f: pre-PSI, red square) and day 6 (e: 24 h post-vehicle, white square; f: 24 h post-PSI, green square) (e: t25 = 1.73, p > 0.05; f: t25 = 3.84, p < 0.001). g and h PSI does not affect extinction of OXY preference in female wild-type mice (n = 24–25 per group). Mice conditioned with OXY were assessed for within-subject changes on day 5 (g: pre-vehicle, red circle; h: pre-PSI, red circle) and day 6 (g: 24 h post-vehicle, white circle; h: 24 h post-PSI, green circle) (g: t23 = 1.56, p > 0.05; h: t24 = 1.48, p > 0.05). i OXY-induced CPP in male (n = 19-20 per group) and female (n = 17-19 per group) 5-HT2AR-KO mice (drug F [1,71] = 44.43, p < 0.001; sex F [1,71] = 8.88; p < 0.01; interaction F [1,71] = 2.54, p > 0.05). j PSI does not affect OXY-induced CPP post-acutely in male 5-HT2AR-KO mice (n = 9-10 per group) (OXY F [1,35] = 10.71, p < 0.01; PSI F [1,35] = 0.30, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,35] = 0.11, p > 0.05). k PSI does not affect OXY-induced CPP post-acutely in female 5-HT2AR-KO mice (n = 8-10 per group) (OXY F [1,32] = 11.44, p < 0.01; PSI F [1,32] = 0.40, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,35] = 0.002, p > 0.05). l, m PSI does not affect extinction of OXY preference in male 5-HT2AR-KO mice (n = 10 per group). Mice conditioned with OXY were assessed for within-subject changes on day 5 (l: pre-vehicle, red circles; m: pre-PSI, red circles) and day 6 (l: 24 h post-vehicle, white circles; m: 24 h post-PSI, green circles) (l: t9 = 0.66, p > 0.05; m: t9 = 0.14, p > 0.05). n and o PSI affects extinction of OXY preference in female 5-HT2AR-KO mice (n = 9-10 per group) (n: pre-vehicle, red circle; o: pre-PSI, red circle) and day 6 (n: 24 h post-vehicle, white circle; o: 24 h post-PSI, green circle) (n: t8 = 0.98, p > 0.05; o: t9 = 4.40, p < 0.01). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA (++p < 0.01, +++p < 0.001, n.s., not significant) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (b–d, i–k), or paired Student’s t-test (e–h, l–o) (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, n.s., not significant). Data show mean ± s.e.m.

Sex differences in post-acute effects of PSI on OXY-induced CPP

Next, we interrogated the consequence of a single exposure to PSI on the post-acute conditioned effects of repeated OXY exposure. As above, mice were habituated to CPP chambers (day 1) and then underwent OXY (3 mg/kg) or vehicle conditioning for three days (days 2-4). On day 5, expression of OXY-induced CPP was measured as a preference score followed by administration of PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle. On day 6, preference was measured 24 h post-treatment (Fig. 2a). Our data indicated a PSI-induced reduction in the expression of OXY preference in male mice (Fig. 2c), an effect that was not observed in female animals (Fig. 2d). PSI administered to non-opioid conditioned mice had no effect on post-condition score in either sex (Fig. 2c, d). To evaluate whether the reduction of OXY-induced CPP was due to a facilitation of extinction learning, the same cohort of male and female mice was assessed for within-subject changes in preference scores across day 5 (pre-PSI/vehicle treatment) and day 6 (24 h post-PSI/vehicle treatment). We show that male mice conditioned with OXY and treated with PSI (but not vehicle) had a significant decrease in preference score across time points (Fig. 2e, f, and Supplementary Figs. 3a, b and 4a). This PSI-induced post-acute effect was not observed in the female cohort (Fig. 2g, h, and Supplementary Figs. 3c, d and 4b), suggesting that PSI treatment accelerates extinction of OXY-induced CPP in a sex-dependent manner.

Sex differences in post-acute effects of DOI on OXY-induced CPP

To evaluate whether this effect could be extended to other chemical group of classical psychedelics, we tested the post-acute effect of the phenethylamine DOI. As with our work using PSI, the DOI dose (2 mg/kg) was selected based on our previous findings showing maximal sex-related differences on DOI-induced HTR29. As before (see Fig. 2b), both male and female mice exhibited an increased preference to OXY relative to vehicle-treated controls, with no significant sex differences observed (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Interestingly, when assessed 24 h after administration of DOI (2 mg/kg), neither male nor female mice conditioned with OXY displayed a significant reduction in OXY-induced CPP (Supplementary Fig. 5b, c). Furthermore, DOI administration alone did not alter post-conditioning scores in non-conditioned control animals (Supplementary Fig. 5b, c). Notably, male mice conditioned with OXY and subsequently treated with DOI, but not vehicle, exhibited a significant reduction in preference between day 5 (pre-DOI treatment) and day 6 (24 h post-treatment) (Supplementary Figs. 5d, e, 6a, b and 7a). This effect was not observed in female mice (Supplementary Figs. 5f, g, 6c, d and 7b).

PSI reduces OXY-induced CPP via 5-HT2AR

Given the post-acute effects of PSI on both expression and extinction of OXY preference, we assessed whether these effects are 5-HT2AR-dependent. To test this, we used male and female 5-HT2AR-KO mice in the same CPP paradigm (Fig. 2a). As with wild-type controls, both male and female 5-HT2AR-KO mice conditioned with OXY expressed a greater preference score than vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 2i). However, a sex effect was observed, with female 5-HT2AR-KO mice showing a reduction in OXY preference compared to male 5-HT2AR-KOs (Fig. 2i). When tested 24 h following administration of PSI, neither male nor female 5-HT2AR-KO mice showed a reduction in their OXY-induced CPP (Fig. 2j, k). A three-way ANOVA also indicated genotype-related differences in the effect of PSI on OXY-induced CPP in male and female mice (Supplementary Table 4). Similar to the wild-type control group, PSI treatment had no effect on post-condition score in the non-conditioned 5-HT2AR-KO mice in either sex (Fig. 2j, k). In the within-subjects measure across days 5 and 6, male 5-HT2AR-KO mice had no significant decrease in OXY preference score across time points (Fig. 2l, m, and Supplementary Figs. 8a, b and 9a), suggesting that PSI facilitates extinction of OXY-induced CPP via a 5-HT2AR-dependent mechanism. Interestingly, female 5-HT2AR-KO mice treated with PSI, but not vehicle, showed a significant increase in OXY preference score within subjects across time points (Fig. 2n, o, and Supplementary Figs. 8c, d and 9b).

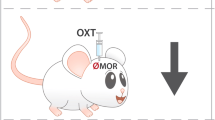

PSI reduces somatic signs of OXY withdrawal via 5-HT2AR

Opioid withdrawal syndrome, which is characterized in part by somatic signs, motivates compulsive drug-seeking and drug-taking behaviors in some individuals31. To examine the post-acute effects of PSI on physical signs of OXY withdrawal, male and female mice were implanted with OXY (60 mg/kg/day) or vehicle minipumps for one week. On day 8, 30-min after removal of the minipumps, male and female mice were administered PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle, and 24 h later (day 9), the animals were observed for somatic signs of withdrawal, including paw tremors, head shakes, backing, ptosis and jumping, for 30 min (Fig. 3a). As expected32, mice that received OXY via mini-pump delivery showed higher signs of withdrawal compared to the vehicle group, regardless of sex (Fig. 3b, c). Importantly, male mice treated with PSI exhibited a reduction in somatic signs, with no significant difference from the vehicle-treated group (Fig. 3b). In contrast, this post-acute PSI-induced effect on OXY withdrawal was absent in female mice (Fig. 3c). In 5-HT2AR-KO mice, however, male animals showed no significant decrease in somatic signs following treatment with PSI (Fig. 3d), suggesting that the reduction of somatic signs of OXY withdrawal upon PSI treatment is mediated through a 5-HT2AR-dependent mechanism. Our data also indicate lack of effect of PSI administration on OXY withdrawal symptoms in female 5-HT2AR-KO mice (Fig. 3e). There were no effects of PSI alone on somatic signs across sexes and genotypes (Fig. 3b–e). A three-way ANOVA also indicated sex- and genotype-related differences in the effect of PSI on OXY withdrawal in male and female mice (Supplementary Table 5).

a Timeline of the experimental design. b Post-acute effects of PSI on somatic signs of OXY withdrawal in male wild-type mice (n = 8-9 per group) (OXY F [1,29] = 81.32, p < 0.001; PSI F [1,29] = 28.74, p < 0.001; interaction F [1,29] = 25.55, p < 0.001). c Post-acute effects of PSI on somatic signs of OXY withdrawal in female wild-type mice (5–10 per group) (OXY F [1,28] = 20.29, p < 0.001; PSI F [1,28] = 0.09, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,28] = 0.66, p > 0.05). d Post-acute effects of PSI on somatic signs of OXY withdrawal in male 5-HT2AR-KO mice (n = 3-6 per group) (OXY F [1,17] = 26.11, p < 0.001; PSI F [1,17] = 0.08, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,17] = 0.71, p > 0.05). e Post-acute effects of PSI on somatic signs of OXY withdrawal female 5-HT2AR-KO mice (3-4 per group) (OXY F [1,11] = 31.90, p < 0.001; PSI F [1,11] = 0.89, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,11] = 0.64, p > 0.05). f and g Post-acute effects of PSI on OXY-induced antinociception in male wild-type mice (n = 6 per group) (f: drug F [3,20] = 66.90, p < 0.001; time F [6,120] = 17.53, p < 0.001; interaction F [18,120] = 4.40, p < 0.001) (g: OXY F [1,20] = 494.0, p < 0.001; PSI F [1,20] = 0.82, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,20] = 0.84, p > 0.05). h and i Post-acute effects of PSI on OXY-induced antinociception in female wild-type mice (5-6 per group) (h: drug F [3,19] = 27.30, p < 0.001; time F [6,114] = 26.29, p < 0.001; interaction F [18,114] = 8.30, p < 0.001) (i: OXY F [1,19] = 123.8, p < 0.001; PSI F [1,19] = 0.007, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,19] = 0.10, p > 0.05). Maximum possible effect (MPE). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA (b–e, g, i) or two-way repeated measured ANOVA (f, h) (+++p < 0.001) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, n.s., not significant). Data show mean ± s.e.m.

Post-acute effects of PSI on OXY-induced antinociception

Using the warm water tail-withdrawal as a mouse model of acute thermal nociception, we tested whether PSI post-acutely affected the analgesic effect of OXY (5 mg/kg) in male and female mice. As expected27, OXY caused an increase in antinociception on the tail-flick test in both male (Fig. 3f, g) and female (Fig. 3h, i) mice. Antinociceptive effects were persistent across time points for both sexes up until approximately 60 min post-OXY injection (Fig. 3f, h). We also found that pre-treatment with PSI 24 h prior to OXY administration did not induce adjunctive antinociceptive effects in male (Fig. 3f,g) or female mice (Fig. 3h, i). There were no effects of PSI alone on antinociception in either sex (Fig. 3f–i). Together, these results indicate that PSI may be able to alter behaviors related to opioid reward without altering nociception.

Post-acute effects of PSI on natural reward behavior

To evaluate the potential impact of psychedelic administration on natural reward behavior, we tested saccharin preference 24 h following PSI or vehicle administration. Our data show no differences in saccharin preference (Fig. 4a) or total fluid intake (Fig. 4b) between PSI- and vehicle-treated male or female mice. As an additional control, we examined whether repeated OXY administration affects the subsequent psychoactive effects of PSI, which could interfere with downstream 5-HT2AR-dependent signaling events. To test this, mice received a single dose of PSI or vehicle 24 h after the final administration of OXY or vehicle. Importantly, our data indicate that HTR induced by PSI was not affected by three days of intermittent OXY pre-treatment in male (Fig. 4c) or female (Fig. 4d) mice. However, consistent with previous findings (Fig. 1a), the PSI-induced HTR was increased in female mice compared to males (Fig. 4c, d, and Supplementary Table 6).

a, b Post-acute effects of PSI on saccharine preference (a) and total fluid consumption (b) in male (n = 6 per group) and female (n = 6 per group) wild-type mice (a: drug F [1,28] = 3.23, p > 0.05; sex F [1,28] = 4.08, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,28] = 1.15, p > 0.05) (b: drug F [1,28] = 2.91, p > 0.05; sex F [1,28] = 0.0002, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,28] = 0.01, p > 0.05). c Effect of repeated OXY administration on PSI-induced HTR behavior in male wild-type mice (n = 4 per group) (OXY F [1,12] = 0.04, p > 0.05; PSI F [1,12] = 20.34, p < 0.001; interaction F [1,12] = 0.03, p > 0.05). d Effect of repeated OXY administration on PSI-induced HTR behavior in female wild-type mice (n = 3-4 per group) (OXY F [1,11] = 1,64, p > 0.05; PSI F [1,11] = 191.0, p < 0.001; interaction F [1,11] = 9.36, p < 0.05). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA (a–d) (+++p < 0.001, n.s., not significant) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (*p < 0.05, n.s., not significant). Data show mean ± s.e.m.

Neural circuit-specific restoration of 5-HT2AR expression

The frontal cortex is critical for executive functions such as decision-making and inhibitory control, both of which are impaired in individuals who continue drug use despite adverse consequences33. Excitatory pyramidal neurons in the frontal cortex, where 5-HT2ARs are highly expressed34,35, project to subcortical regions involved in cognitive processes related to motivation, aversion, and reward. Additionally, a substantial body of evidence indicates that excitatory projections from the frontal cortex to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) – a key structure in the mesolimbic reward pathway – are instrumental in shaping adaptive responses to conditioned behavior36,37. To test the connectivity of frontal cortex pyramidal neurons where 5-HT2AR is critical to produce the effects of PSI on reduction of OXY-induced CPP, we used a dual AAV and retrograde AAV (AAVretro) viral strategy to selectively restore 5-HT2AR expression to frontal cortex pyramidal neurons of 5-HT2AR loxP-STOP-loxP (LSL) mice projecting to specific subcortical regions. The 5-HT2ARLSL/LSL mice contain a “neo-stop” sequence inserted into the 5’ untranslated region of the 5-HT2AR (Htr2a) gene (Fig. 5a). This neo-stop cassette is flanked by loxP sequences, allowing it to be excised by Cre recombinase16. Adult male 5-HT2ARLSL/LSL mice were injected with a AAVretro vector expressing a Flp construct under the control of EF1α, a highly active promoter in the CNS38 (AAVretro-EF1α-mCherry-IRES-Flp, or AAVr-Flp-mCherry) into the NAc, and a Flp-dependent Cre construct (AAV-EF1α-fDIO-Cre-IRES-eYFP, or AAV-fDIO-Cre-eYFP) or control viral vector (AAV-EF1α-fDIO-eYFP, or AAV-fDIO-eYFP) into the frontal cortex.

a Schematic representation of the dual AAVretro and AAV strategy to selectively restore 5-HT2AR expression in frontal cortex pyramidal neurons of 5-HT2ARLSL/LSL mice projecting to the NAc. b Representative micrographs of eYFP expression in mouse frontal cortex neurons following injection of AAVretro-EF1α-mCherry-IRES-Flp in the NAc, and AAV-EF1α-fDIO-eYFP in the frontal cortex. Mice received stereotaxic injections of mCherry- and eYFP-tagged (top panels), mCherry-tagged only (middle panels), and eYFP-tagged only (bottom panels) constructs. White arrowheads indicate mCherry-positive cells, whereas yellow arrowheads mark cells that are positive for both mCherry and eYFP. c, d Virally-mediated restoration of 5-HT2AR expression in frontal cortex pyramidal neurons of 5-HT2ARLSL/LSL mice. Animals (5-HT2ARLSL/LSL mice and wild-type controls) received mock viral vector surgeries or stereotaxic administration of AAVr-Flp-mCherry into the NAc, and AAV-fDIO-Cre-eYFP or the AAV-fDIO-eYFP control viral vector into the frontal cortex. Representative immunoblots with anti-5-HT2AR and anti-GAPDH antibodies in mouse frontal cortex samples (c). Expression of 5-HT2AR, 5-HT1AR, D1R and the housekeeping gene Gapdh mRNAs in frontal cortex samples was assessed by RT-qPCR (4-11 per group) (5-HT2AR F [3,29] = 10.51, p < 0.001; 5-HT1AR F [3,18] = 0.59, p > 0.05; D1R F [3,18] = 1.06, p > 0.05;; Gapdh F [3,32] = 1.01, p > 0.05) (d). Scale bar represents 20 µm (b). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (d) (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, n.s., not significant). Data show mean ± s.e.m.

To evaluate whether this direct targeting of specific neural circuits was achieved using the dual viral vector Cre-LSL approach, adult wild-type mice were co-injected with AAVr-Flp-mCherry into the NAc, and the Flp-dependent AAV-fDIO-eYFP construct into the frontal cortex. This dual viral vector Cre-LSL approach was only tested in male mice, considering the sex-related differences observed in the post-acute effects of PSI on OXY-induced CPP. Fluorescence micrographs showed eYFP expression exclusively in cortical cells co-expressing mCherry, an effect not observed in frontal cortex neurons of mice injected locally with the AAV-fDIO-eYFP construct alone (Fig. 5b). As an additional control, mice received stereotaxic injection of AAVr-Flp-mCherry in the NAc without the AAV-fDIO-eYFP construct (Fig. 5b). This evidences that the dual AAVr-Flp-mCherry and AAV-fDIO-eYFP vector approach yields Cre-mediated transgene expression in frontal cortex cells that project to the designated target region only, allowing for pathway-specific assessment.

We confirmed the predicted restoration of the endogenous 5-HT2AR gene product in the frontal cortex of 5-HT2ARLSL/LSL mice co-injected with AAV-fDIO-Cre-eYFP and AAVr-Flp-mCherry in the frontal cortex and NAc, respectively; compared to mock-injected wild-type and 5-HT2AR-KO animals (Fig. 5c, d, and Supplementary Fig. 10). In contrast, expression of other GPCR genes including 5-HT1AR (Htr1A), dopamine D1 (DRD1) and the housekeeping Gapdh remained unaffected (Fig. 5d).

Frontal cortex 5-HT2AR within specific projections to the NAc partially mediates PSI effects on opioid seeking behavior

Using the same AAV/AAVr-based approach, our results corroborated that OXY-induced CPP is undistinguishable in 5-HT2ARLSL/LSL mice co-injected with AAVr-Flp-mCherry and AAV-fDIO-Cre-eYFP, or AAV-fDIO-eYFP controls, as compared with vehicle-treated 5-HT2ARLSL/LSL animals co-injected with AAV-fDIO-Cre-eYFP and AAVr-Flp-mCherry (Fig. 6a).

a OXY-induced CPP in male 5-HT2ARLSL/LSL mice co-injected with AAVr-Flp-mCherry and either AAV-fDIO-Cre-eYFP or AAV-fDIO-eYFP (n = 4-7 per group) (F [2,16] = 7.17, p < 0.01). b Timeline of the experimental design. c PSI does not reverse OXY-induced CPP post-acutely in male 5-HT2ARLSL/LSL mice co-injected with AAVr-Flp-mCherry and AAV-fDIO-Cre-eYFP (n = 3-17 per group) (OXY F [1,36] = 8.36, p < 0.01; PSI F [1,36] = 0.73, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,36] = 0.43, p > 0.05). d, e PSI facilitates extinction of OXY preference in male 5-HT2ARLSL/LSL mice co-injected with AAVr-Flp-mCherry and AAV-fDIO-Cre-eYFP (n = 16 per group). Mice conditioned with OXY were assessed for within-subject changes on day 5 (d: pre-vehicle, red hexagon; e: pre-PSI, red hexagon) and day 6 (d: 24 h post-vehicle, white hexagon; e: 24 h post-PSI, green hexagon) (d: t15 = 0.99, p > 0.05; e: t15 = 2.45, p < 0.05). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way (a) or two-way (c) ANOVA (++p < 0.01) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (a, c), or paired Student’s t-test (d, e) (*p < 0.05, n.s., not significant). Data show mean ± s.e.m.

We further investigated whether neural circuit-specific restoration of 5-HT2AR expression in frontal cortex pyramidal neurons of 5-HT2ARLSL/LSL mice projecting to the NAc was sufficient to achieve the post-acute effect of PSI on OXY-induced CPP (Fig. 6b). When tested 24 h following administration of PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle, 5-HT2ARLSL/LSL animals co-injected with AAV-fDIO-Cre-eYFP and AAVr-Flp-mCherry that were conditioned with OXY and received PSI had no significant reduction of OXY-induced CPP (Fig. 6c). Similarly, PSI alone had no effect on post-condition score in the non-conditioned mice (Fig. 6c).

We next assessed the role of this circuit on facilitation of extinction learning. Interestingly, 5-HT2ARLSL/LSL animals co-injected with AAV-fDIO-Cre-eYFP and AAVr-Flp-mCherry conditioned with OXY and treated with PSI, but not vehicle, showed a decrease in preference score across day 5 (pre-PSI treatment) and day 6 (24 h post-PSI treatment) (Fig. 6d, e, and Supplementary Figs. 11a, b and 12), suggesting that the targeted pathway is implicated in the post-acute effect of PSI on the acute extinction phase of OXY-induced CPP in male mice.

Sex-specific post-acute effects of PSI on MOR-G protein coupling

To gain greater understanding of the signaling mechanisms driving these sex-specific differences, we tested the effect of the MOR agonist DAMGO (10 µM) on [35S]GTPγS binding as a functional readout of GPCR-G protein coupling in frontal cortex and NAc membrane preparations of male and female mice injected previously (24 h before) with PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle. This concentration of DAMGO was selected based on the Emax pharmacological parameter from concentration-response assays in frontal cortex and NAc samples (Supplementary Fig. 13a, b). In vehicle-treated animals, DAMGO increased [35S]GTPγS binding in the frontal cortex (Fig. 7a) and NAc (Fig. 7b), but the MOR agonist’s effect was higher in female mice compared to male animals (Supplementary Table 7). Additionally, pre-administration of PSI 24 h in advance reduced the effect of DAMGO on [35S]GTPγS binding in the frontal cortex of female, but not male mice (Fig. 7a); an observation that was not apparent in NAc membrane preparations of both sexes (Fig. 7b, Supplementary Table 8). Similarly, reduced MOR mRNA expression was observed in the frontal cortex of female, but not male, mice following PSI pre-administration (Fig. 7c, d). However, radioligand binding assays using the MOR antagonist [3H]naloxone revealed no change in MOR protein levels in either sex 24 h after a single administration of PSI compared to vehicle (Fig. 7e). Notably, a two-way ANOVA indicated significantly higher MOR density in the frontal cortex of female mice compared to males (Fig. 7e).

a Effect of the MOR agonist DAMGO (10 µM) on [35S]GTPγS binding in membrane preparations of frontal cortex samples from male (n = 10) and female (n = 8) wild-type mice (males: DAMGO F [1,36] = 25.90, p < 0.001; PSI F [1,36] = 0.41, p > 0.05, interaction F [1,36] = 0.68, p > 0.05) (females: DAMGO F [1,28] = 17.07, p < 0.01; PSI F [1,28] = 5.29, p < 0.05; interaction F [1,28] = 5.29, p < 0.05) (sex F [1,64] = 7.14, p < 0.01; see Supplementary Table 7 for additional statistical comparisons). b Effect of the MOR agonist DAMGO (10 µM) on [35S]GTPγS binding in membrane preparations of NAc samples from male (n = 8) and female (n = 4) wild-type mice (males: DAMGO F [1,28] = 19.92, p < 0.001; PSI F [1,28] = 0.23, p > 0.05, interaction F [1,28] = 0.23, p > 0.05) (females: DAMGO F [1,12] = 891.0, p < 0.001; PSI F [1,12] = 1.32, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,12] = 1.32, p > 0.05) (sex F [1,40] = 27.53, p < 0.001; see Supplementary Table 8 for additional statistical comparisons). c PSI does not alter MOR (µ-OR) or housekeeping gene rps3 mRNA expression in the frontal cortex of male wild-type mice (n = 5) (µ-OR: t8 = 0.05, p > 0.05; rps3: t8 = 1.24, p > 0.05). d PSI reduces MOR (µ-OR) but not housekeeping gene rps3 mRNA expression in the frontal cortex of female wild-type mice (n = 5) (µ-OR: t8 = 3.14, p < 0.05; rps3: t10 = 1.20, p > 0.05). e PSI does not alter MOR density in the frontal cortex of male (n = 6) or female (n = 6) wild-type mice, as assessed by [3H]naloxone binding assays (PSI F [1,20] = 1.48, p > 0.05; sex F [1,20] = 6.53, p < 0.05; interaction F [1,20] = 0.04, p > 0.05). Agonist-induced [35S]GTPγS binding is presented as net stimulation (DAMGO effect minus basal [35S]GTPγS binding) (a, b). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way and/or three-way ANOVA (+p < 0.05. ++p < 0.01, +++p < 0.001) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (a, b, e), or multiple unpaired t-test (c, d) (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, n.s., not significant). Data show mean ± s.e.m.

Sex-specific epigenomic modulation by PSI following repeated OXY exposure

Building on these sex-specific effects at the MOR signaling level, we next assessed whether PSI alters the epigenomic landscape in a sex-dependent manner following repeated opioid exposure. Previous studies have demonstrated that opioids promote an open chromatin state via acetylation of histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27ac), which facilitates overexpression of genes specifically involved in OUD39,40,41. Our previous work suggested that a single administration of the phenethylamine psychedelic DOI has a lasting impact on the epigenomic landscape, as opposed to more transient transcriptomic alterations, in the frontal cortex of adult male mice21. We thus sought to examine potential epigenomic differences between sexes following OXY treatment and subsequent psychedelic exposure. Following a protocol similar to that used in the CPP test (Fig. 2a), mice received three separate administrations of OXY (3 mg/kg) or vehicle on consecutive days (days 1-3), with 24 hour intervals between doses, followed by a single dose of PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle (day 4), resulting in four distinct experimental groups: VEH-VEH, VEH-PSI, OXY-VEH, and OXY-PSI. On day 5, tissue samples were collected for H3K27ac profiling in NeuN-positive neuronal nuclei isolated from the frontal cortex and NAc by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). The unsupervised hierarchical clustering shows that the individual brain samples largely cluster within each group, with the exception of the male NAc samples (Supplementary Fig. 14).

Next, we used VEH-VEH as the reference to create lists of differential enhancers that are affected by the VEH-PSI, OXY-VEH, and OXY-PSI experimental conditions. Enhancers were defined by H3K27ac peaks that do not overlap with regions near transcription start sites (TSS)21,42. For all treatment conditions, there were substantially fewer differential enhancers in females than in males (Fig. 8a, b). Between the two brain regions, the number of differential enhancers was generally much higher in the NAc (Fig. 8b) than in the frontal cortex (Fig. 8a) for both sexes.

a Number of differential enhancers in the frontal cortex of male and female wild-type mice across treatments: oxycodone-vehicle, oxycodone-psilocybin and vehicle-psilocybin, with the vehicle-vehicle group as the reference. b Number of differential enhancers in the NAc of male and female wild-type mice across treatments: oxycodone-vehicle, oxycodone-psilocybin and vehicle-psilocybin, with the vehicle-vehicle group as the reference. c–f Overlap between the differential enhancer-like genes under oxycodone-vehicle (OXY-VEH) and oxycodone-psilocybin (OXY-PSI) treatment in frontal cortex (c, d) and NAc (e, f) samples of male (c, e) and female (d, f) wild-type mice. g–o Top KEGG terms associated with the groups of differential enhancer-linked genes in c–f. Top 10 terms are listed if there are more than 10 terms. The complete lists of terms are included in Supplementary Data 1. Only groups that yield enriched terms are included. Male (n = 4-6) and female (n = 3–6) mice were treated with OXY (3 mg/kg) or vehicle once a day for three days, received a single administration of PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle 24 h after the last treatment, and tissue samples (frontal cortex and NAc) were collected 24 h after (n = 3-6 mice per group). See Supplementary Data 1 for additional statistical information.

To ensure high accuracy gene annotation, differential enhancers were overlapped with previously published datasets generated using the Hi-C method, a technique which evaluates chromatin conformation based on frequency of DNA fragment physical associations43. Hi-C data allow identification of long-range contacts between enhancer and genes44. Non-overlapped enhancers were annotated to their nearest neighbor genes. In order to decipher the epigenomic changes associated with repeated opioid exposure, both alone and in combination with psychedelic administration, we divided the differential enhancer-linked genes associated with OXY-VEH and OXY-PSI into three groups (Fig. 8c–f): i) genes altered exclusively in the OXY-VEH group (these genes are altered by repeated OXY administration but recover to the reference state after post-acute PSI treatment); ii) overlapping genes (these genes are altered by repeated OXY administration and remain altered after post-acute PSI treatment); and iii) genes exclusively altered in the OXY-PSI group. We also observed additional genes that were not altered by repeated OXY administration but were post-acutely affected upon a single treatment with PSI (Supplementary Data 1). Next, we conducted GO analysis – a ranked statistical approach used to identify enriched gene clusters based on shared functional characteristics associated with specific biological processes45,46 – across various groups of genes. For male frontal cortex samples (Fig. 8c, and Supplementary Data 1), Group I genes were mostly enriched in GO terms related to cell-substrate adhesion, which is a major morphogenetic factor previously implicated in SUD47. Interestingly, our results suggest that PSI may counteract the effects of repeated OXY administration via cell-adhesion-associated pathways in male frontal cortex. Group I genes of both sexes in frontal cortex samples presented connections with morphogenesis, dendrite development, and synapse terms (Fig. 8c,d, and Supplementary Data 1). Previous research has demonstrated that opioids significantly affect cognitive processes such as learning and memory, often resulting in the formation of strong associations and cue-induced behaviors in response to drug-related stimuli48. The reactivation of genes linked to learning and memory may contribute to the observed reversal of opioid-induced CPP in male mice following PSI administration. Notably, learning- and memory-related gene signatures were absent in female mice.

KEGG pathway analysis – a method that draws upon an index of biological pathways and networks associated with enriched gene clusters49 – was conducted for Group I, Group II, and Group III genes in the frontal cortex (Fig. 8g–i) and NAc (Fig. 8j–o) of both sexes. In male mice, PSI treatment led to the recovery of genes involved in both the RAP1 and cAMP signaling pathways. RAP1-dependent signaling pathways have been shown to alter neuronal excitability and behaviors associated with drug responses in the NAc of mice50, while upregulation of the cAMP signaling pathway in the NAc is a prominent feature of OUD51. In contrast, the genes recovered following PSI treatment (Group I) in the female NAc did not yield any significant terms related to SUD or neuronal activity. This result suggests that the male NAc is more strongly affected by PSI treatment in reversing the effects of OXY compared to the female NAc. While both male and female frontal cortices did not yield significantly enriched KEGG terms for Group I genes, Group III genes in the female frontal cortex were uniquely enriched in long-term depression. A previously reported meta-analysis indicated that highly enriched SUD-related genes among four drug classifications were most significantly involved in pathways associated with long-term synaptic depression52.

In order to highlight the overall difference between the two sexes in terms of PSI post-acute effects on repeated OXY administration, we constructed heatmaps of differential enhancers containing both sexes and three conditions (VEH-VEH, OXY-VEH, and OXY-PSI) after K-means clustering for the two brain regions (Fig. 9, Supplementary Data 2). In line with our previous work53, we investigated the similarity in variation patterns across the three conditions between sexes and quantified this similarity using the average pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients (PPCC) for each K-means cluster. As shown in the heatmap (Fig. 9a), two out of the four frontal cortex clusters (clusters II and III) display markedly different patterns of variation, with PPCCs of −0.21 and −0.23, respectively (Fig. 9b). In contrast, the pattern of variation is similar between the sexes for all four NAc clusters (Fig. 9c), supported by relatively high PPCC values ranging from −0.05 to 0.33 (Fig. 9d). In frontal cortex cluster II, the sexes show opposing trends when comparing VEH-VEH and OXY-VEH conditions (Fig. 9a). Similarly, in frontal cortex cluster III, the sexes exhibit opposite trends when comparing OXY-VEH and OXY-PSI conditions (Fig. 9a). Overall, the frontal cortex appears to exhibit substantially greater differences across sexes than the NAc in response to enhancer regulation and OXY versus OXY-PSI treatment.

a K-means clustering of differential enhancers in the frontal cortex. b Average pairwise Pearson correlation coefficient (PPCC) for each K-means cluster in (a). c K-means clustering of differential enhancers in the NAc. d Average pairwise Pearson correlation coefficient (PPCC) for each K-means cluster in (b). Male (n = 4-6) and female (n = 3–6) wild-type mice were treated with OXY (3 mg/kg) or vehicle once a day for three days, received a single administration of PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle 24 h after the last treatment, and tissue samples (frontal cortex and NAc) were collected 24 h after (n = 3–6 mice per group). See Supplementary Data 2 for additional statistical information.

Sex-specific effects of PSI on structural plasticity in the NAc are independent of 5-HT2AR

Previous work has reported that psychoactive drugs with high abuse liability such as cocaine increase the dendritic spine density in the NAc54,55. Here we tested the extent to which PSI produces fast-acting changes in the structural plasticity of the NAc in male and female mice, and whether this effect was 5-HT2AR-dependent. Mice received intra-NAc injections of herpes simplex 2 viral particles expressing green fluorescent protein (HSV-GFP). First, we confirmed that the virus overexpressed GFP in mouse NAc (Fig. 10a and Supplementary Fig. 15). Next, after surgery and a recovery period of 3 days, mice received either a single dose of PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle, and were sacrificed 24 h post-administration. Notably, male mice treated with PSI exhibited a reduction in overall dendritic spine density in the NAc compared to their vehicle-treated counterparts (Fig. 10b, c). In contrast, female mice receiving PSI demonstrated an increase in overall dendritic spine density in the NAc relative to the vehicle group (Fig. 10b, d). This effect of PSI on post-acute dendritic spine density was not 5-HT2AR-dependent, as a similar phenotype was observed in both male and female 5-HT2AR-KO animals (Fig. 10b–d). Furthermore, no main effect of genotype was noted (Supplementary Fig. 16 and Supplementary Table 9).

a–f Post-acute effects of PSI on dendritic spine structural elements in the NAc of 5-HT2AR-KO mice and wild-type controls. Samples from male and female animals were collected 24 h after a single injection of PSI (1 mg/kg) or vehicle. Representative image of HSV-mediated transgene expression in the NAc. HSV-GFP was injected in the NAc, and GFP expression was revealed by fluorescence microscopy imaging (a). Representative three-dimensional reconstructions of HSV-injected NAc dendritic segments (b). Total NAc dendritic spine density in male wild-type (n = 44-58 neurons from 3-4 mice) and 5-HT2AR-KO (n = 15-17 neurons from 3-4 mice) littermates (PSI F [1,130] = 18.18, p < 0.001; genotype F [1,130] = 0.53, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,130] = 0.02, p > 0.05; see Supplementary Table 9 for additional statistical comparisons) (c). Total NAc dendritic spine density in female wild-type (n = 31-35 neurons from 3-4 mice) and 5-HT2AR-KO (n = 28-33 neurons from 3-4 mice) and littermates (PSI F [1,123] = 34.86, p < 0.001; genotype F [1,123] = 0.19, p > 0.05; interaction F [1,123] = 6.81, p < 0.01; see Supplementary Table 9 for additional statistical comparisons) (d). Stubby, thin and mushroom NAc dendritic spine density in male and female wild-type mice (PSI F [1,468] = 0.56, p > 0.05; spine type F [2,468] = 186.1, p < 0.001; sex F [1,468] = 0.34, p < 0.05; interaction F [2468] = 12.95, p < 0.001; see Supplementary Table 10 for additional statistical comparisons) (e). Stubby, thin and mushroom NAc dendritic spine density in male and female 5-HT2AR-KO mice (PSI F [1,270] = 2.70, p > 0.05; spine type F [2270] = 35.46, p < 0.001; sex F [1,270] = 3.52, p = 0.06; interaction F [2270] = 2.67, p = 0.07; see Supplementary Table 11 for additional statistical comparisons) (f). g-i Repeated PSI administration affects reward processing in a sex-dependent manner. Timeline of the experimental design (g). PSI-induced CPP in male wild-type mice (n = 12 per group) (t22 = 1.09, p > 0.05) (h). PSI-induced CPP in female wild-type mice (n = 8-9 per group) (t15 = 3.60, p < 0.01) (i). Scale bars represent 20 µm (a) or 10 µm (b). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way (c, d) or three-way (e, f) ANOVA (+++p < 0.001, n.s., not significant) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test, or unpaired Student’s t-test (h, i) (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. n.s., not significant). Data show mean ± s.e.m.

Synaptogenesis and functional synaptic plasticity are closely linked to the size and shape of dendritic spines. As spines progress from immature forms – such as thin and stubby – to mature mushroom shapes, they concurrently enhance synaptic strength and stability56,57. In our study, we found that male wild-type mice exhibited a decrease in both mushroom and immature thin spines following PSI administration (Fig. 10b, e, and Supplementary Table 10). In contrast, wild-type female mice treated with PSI showed an increase in mushroom and stubby spines (Fig. 9b, e, and Supplementary Table 10). Notably, the post-acute effects of PSI on stubby spines remained evident in the NAc of both male and female 5-HT2AR-KO mice, while thin and mature mushroom spines showed no significant changes (Fig. 10b, f, and Supplementary Table 11).

Sex-specific effects of repeated PSI administration on CPP

To our knowledge, PSI has not yet been tested in CPP models for its potential rewarding effects. However, it has been shown to be non-reinforcing in other assays of reward behavior, though these experiments were conducted exclusively in male rodents58 and non-human primates59. To evaluate PSI-induced CPP in both sexes while minimizing potential tachyphylaxis, we developed an experimental design that includes a 4-day washout period between PSI conditioning sessions, followed by testing for changes in place preference (Fig. 10g). We found that male mice conditioned with PSI did not develop a place preference when compared to vehicle-conditioned male animals (Fig. 10h). Inversely, female mice conditioned with PSI showed an increased preference compared to those conditioned with vehicle (Fig. 10i). Together with the synaptic structural and epigenomic plasticity findings, these results suggest that PSI may not affect OXY-induced CPP in female mice due to its sex-specific confounding effects on rewarding behaviors.

Discussion

The results of this study reveal distinct sex-dependent behavioral and cellular plasticity effects of psychedelics in mouse models of opioid rewarding properties. A single administration of the classical psychedelic PSI reduced the expression of OXY-induced CPP in male, but not female, mice – an effect observed one day after the psychedelic had been administered, when it is already fully metabolized. This reduction was further linked to an acceleration of extinction learning in males, whereas female mice exhibited no such effect. Importantly, the attenuation of OXY-induced CPP upon post-acute PSI administration in males required expression of the 5-HT2AR, as male 5-HT2AR-KO mice did not exhibit this reduction, while female 5-HT2AR-KO mice unexpectedly demonstrated an increase in OXY-induced CPP post-PSI treatment. The consequence of a single exposure to PSI on post-acute facilitation of extinction learning following repeated OXY administration occurred via a top-down mechanism, where 5-HT2ARs in frontal cortex pyramidal neurons projecting to the NAc mediate these effects. A similar sex-specific effect was observed upon post-acute PSI administration via 5-HT2AR when evaluating somatic opioid withdrawal symptoms, whereas the acute antinociceptive properties of OXY remained unaffected following treatment with this psychedelic in both sexes. We also provide evidence that the sex-specific efficacy of PSI in modulating opioid extinction learning is mediated through mechanisms involving sex-related differences in subcortical epigenomic and synaptic plasticity effects via GPCRs other than 5-HT2AR. Together, these findings advance our knowledge related to the molecular targets and neural circuit underlying the translationally relevant effects of psychedelics in rodent models of OUD, providing key mechanistic insights into the sex-dependent modulation of opioid-induced plasticity.

Little research exists on the post-acute effects of psychedelics in the context of reward-related phenotypes, with most studies focusing on alcohol consumption and preference60,61. More recent studies have explored the potential therapeutic use of psychedelics under acute administration; when their hallucinogenic properties are still observable62,63. While such findings are pharmacologically interesting, this approach may limit translational validity since previous studies suggest clinically relevant post-acute alterations lasting up to six months after PSI administration64. It has also been recently reported that PSI reduces opioid seeking behavior in a rat model of heroin self-administration65; however, this work was conducted exclusively in male animals. Using an OXY-induced CPP paradigm, where PSI was administered following the development of opioid-induced preference to reflect an intervention-based action, as opposed to a prevention-based pre-treatment, we assessed the post-acute effects of PSI on both overall OXY preference and the extinction learning phase following preference. Our data demonstrate that PSI not only reduced overall OXY preference in male mice, but also, under the same paradigm of post-acute psychedelic administration, produced a strong within-subject extinction of OXY preference over time. These effects in male mice were shown to be 5-HT2AR-dependent and specific to opioid rewarding effects, not due to underlying deficits in unconditioned behavior. Additionally, PSI did not alter natural reward behaviors, such as saccharin preference.

While reduction in expression of opioid-induced CPP involves decreasing the rewarding or reinforcing value of opioids, acceleration of extinction learning is a process where the association between the drug context and its rewarding effects is diminished through repeated exposure to the context without the drug30. An interesting observation was that, whereas virally mediated restoration of 5-HT2AR expression in frontal cortex pyramidal neurons of 5-HT2ARLSL/LSL mice projecting to the NAc effectively reinstated the post-acute effect of PSI on the acceleration of extinction learning after repeated OXY administration, targeting this top-down neural mechanism was insufficient to reduce OXY preference in male mice upon post-acute PSI administration, as compared to post-acute vehicle. This finding supports the specificity of the frontal cortex 5-HT2AR-NAc circuit in processes associated with memory consolidation and suppression of drug-related cues; however, the exact neural circuit mechanism underlying psychedelic-induced reduction in the expression of opioid preference, including OXY, remains to be investigated. Nevertheless, this effect may be driven by distinct 5-HT2AR populations, as DOI accelerated extinction learning in male mice only, but did not affect the expression of OXY-induced CPP in either sex.

Although the acute hallucinogenic effects and post-acute clinically relevant outcomes of psychedelics in humans have been consistently studied and reported25, relatively limited attention has been given to differences across genders. The results of this study highlight distinct sex-dependent behavioral and neurobiological plasticity effects of PSI, both alone and in combination with repeated OXY administration. In contrast to what was observed in male mice, at the particular dose of PSI that we evaluated (selected based on its dose-response effect on HTR behavior), psychedelic administration did not affect any of the behavioral parameters we tested following OXY-induced CPP in wild-type female mice. This may be due to an exaggerated response upon PSI administration in female mice, considering the higher HTR effect observed at the same dose compared to male mice, which could limit the plasticity-related outcomes of post-acute PSI in females. This aligns with the opposite effects induced by post-acute PSI in females, but not males, such as heterologous GPCR desensitization of MOR function (tested by downstream G protein-dependent signaling in the frontal cortex), and increased dendritic spine density in the NAc. Differences in GPCR binding and functional outcomes may contribute to sex differences in both 5-HT2AR- and MOR-dependent effects, potentially due to pharmacological crosstalk between the two receptors66. Previous27,29 and current data indicate that 5-HT2AR density is decreased, while both MOR density and DAMGO-induced MOR-G protein coupling are increased in the frontal cortex of female mice compared to males. Female mice also exhibited a series of behavioral alterations upon post-acute PSI administration that were sex-specific, such as reduced exploratory time during anxiety-like behavior and cognitive testing paradigms, as well as an augmentation of OXY preference in 5-HT2AR-KO animals. Preference to OXY during the CPP approach was also reduced prior to PSI administration in female 5-HT2AR-KO mice compared to their male KO littermates. Together with previous findings showing sex-specific effects of DOI on both HTR behavior29 and prepulse inhibition of startle67 (a model of sensorimotor gating), as well as of the effects of volinanserin on OXY-induced antinociception27, these results suggest the presence of potential compensatory mechanisms that may differentially influence the post-acute plasticity-related effects of PSI and other classical psychedelics across sexes. Future studies using a dose-response approach to evaluate the post-acute effects of PSI administration in both sexes will be valuable to fully capture the range of behavioral and neurobiological adaptations that may underlie these sex-specific outcomes.

These differences in the post-acute effects of psychedelics in male and female mice are further supported by our findings on the impact of PSI treatment on epigenomic regulation following repeated OXY administration. Previous work has established that dopamine-dependent signaling in the NAc plays a central role in the processing of rewards and reinforcing behaviors68. Our results provide insights into epigenomic changes that align with these earlier findings, as both PSI and OXY, whether tested individually or sequentially, lead to pronounced effects in the NAc compared to the frontal cortex in terms of the number of altered enhancers. Our epigenomic profiling shows a lower number of altered enhancers in frontal cortex and NAc samples from female mice compared to male animals after the same repeated OXY treatment. This provides an epigenomic basis for previous observations that female rats self-administered twice as much OXY relative to males69,70. In addition, female frontal cortex and NAc brain regions exhibited fewer altered enhancers than the male equivalent samples following PSI alone or combined with repeated OXY administration. Our data also indicate that male mice showed PSI-induced differences in genes involved in cognitive processes in both frontal cortex and the NAc, while similar cognition-linked epigenomic alterations were absent in females. There has been widespread reporting of the involvement of these brain regions in cognitive function and flexibility71,72, and the effects of PSI on these processes25. The recovery of cognition-associated genes to their otherwise basal epigenomic configuration in male mice after PSI treatment may underlie the changes in OUD-related behaviors. Genes in the male NAc, whose epigenomic regulatory status was altered by OXY administration and then restored by post-acute PSI treatment, were significantly linked with biological processes related to cognition, as well as signaling pathways (RAP1 and cAMP) heavily implicated in drug misuse and SUDs50.

Global mapping of differential enhancers demonstrates that more significant differences across the sexes occur in the frontal cortex rather than the NAc, despite the fact that the NAc exhibits more epigenomic alterations than the frontal cortex in response to OXY or PSI treatment. As part of the reward circuitry, the frontal cortex is thought to be critical in the etiology of SUDs due to its key role in shaping higher-order executive function48,72. Various anatomical subdivisions of the frontal (e.g., the more dorsal prelimbic and the more ventral infralimbic subregions) may also play different roles in driving drug-seeking behaviors73,74. Our results on the substantial sex differences in the frontal cortex’s epigenomics underscore the potential importance of this brain region in mediating the sex-specific effects of post-acute PSI on the rewarding properties observed upon repeated OXY administration.

An alternative, but not mutually exclusive, explanation for the differences across sexes in the post-effects of PSI could be related to cue-related responses. Studies in healthy human volunteers associated with relapse have reported that males present an increase in drug-primed or environmental cue-related relapse whereas females were reported to respond more to stress-related cues75,76. Our data could be reflective of this reported phenomenon since CPP is largely based on the conditioning of the interoceptive drug effects with contextual cues. Using a recognition task to evaluate whether cognitive processes, including recognition memory, were affected at the same time point (24 h) following PSI administration, we show no effect of the psychedelic in either sex. Interestingly, male mice showed increased exploration time compared to females. Considering that 5-HT2AR co-activation facilitates morphine-induced MOR desensitization and down-regulation66, together, these findings open new lines of research focused on mechanisms underlying sex differences in the post-acute of PSI on opioid-induced behavioral plasticity, as well as the neural circuit responsible for the 5-HT2AR-dependent effects of PSI on reduction of expression of OXY-induced CPP in male and female mice. Similarly, further investigation will examine interactions with the estrous cycle and the role of ovarian hormones in regulating psychedelic-induced plasticity in rodents77,78.

It remains to be determined how a single administration of PSI leads to reduced MOR mRNA expression and attenuated G protein coupling in the frontal cortex in a sex-specific manner, despite no detectable changes in total MOR density as assessed by [3H]naloxone binding assays following post-acute PSI treatment. It is worth noting, however, that [3H]naloxone binding was conducted using total membrane preparations from crude homogenates, whereas DAMGO-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding assays were performed on synaptosomal fractions (i.e., P2 membranes). This methodological difference may suggest that, at 24 h post-PSI administration, MOR trafficking and subcellular localization – and consequently, the ability of MOR to recruit heterotrimeric G proteins – is altered, even as total receptor levels remain unchanged.

Our findings also bear on the hypothesized role of 5-HT2AR in the synaptic structural plasticity effects of psychedelics in frontal cortex as compared to subcortical regions such as the NAc. Previous studies using full KO mice have suggested that 5-HT2ARs expressed post-synaptically in frontal cortex pyramidal neurons are responsible for the effects of psychedelics increasing both dendritic arbor complexity and dendritic spine density21,22,23. Interestingly, our current data indicate opposite sex-dependent effects of PSI upon post-acute administration on overall dendritic spine density in the NAc with a decrease and an increase in male and female animals, respectively. These post-acute effects of PSI on subcortical structural plasticity are not mediated via 5-HT2AR, since a comparable effect of NAc dendritic spine density was observed in male and female 5-HT2AR-KO mice. This observation is particularly intriguing, given that previous studies have consistently shown opioids to reduce the number and complexity of dendritic spines on NAc medium spiny neurons79,80. On the contrary, it has been reported that psychoactive drugs with high abuse liability such as cocaine increase the dendritic spine density in the NAc54,55. Similarly, our previous work focused on the post-acute plasticity-related effect of the psychedelic DOI were mediated via a 5-HT2AR-dependent upregulation of immature and transitional dendritic spines that included thin and stubby, whereas the density of mature mushroom spines remained unaffected21. All these studies, however, have predominantly been carried out in male mice21,54,55,79,80. Our current findings indicate that most of the sex-specific effects of PSI on NAc dendritic spine density in terms of mature mushroom spines seemed to be absent in male and female 5-HT2AR-KO mice, whereas these post-acute structural plasticity events on the immature stubby spines were still observable in mice lacking this excitatory serotonin receptor. Further work will be necessary to better understand the receptor target and downstream signaling events responsible for these sex-related effects of psychedelics on dendritic spine density in the NAc, as well as the potential abuse liability of PSI and other classical psychedelics in female rodent models, particularly considering our findings that repeated PSI administration leads to conditioned effects in female but not male mice. Regardless, these results provide important insights to both preclinical and clinical researchers working with classical psychedelics, as well as those investigating potential sex differences and sex bias in drug abuse liability.

The integration of molecular and behavioral neuroscience plays a pivotal role in unraveling mechanisms underlying the actions of psychedelics, particularly in light of their profound and enduring therapeutic effects demonstrated in both preclinical models and clinical studies. Physical and psychological states, expectancy, placebo effects, and behavioral history are critical factors influencing the clinical outcomes of psychedelic studies81,82,83. However, their direct impact on psychedelic efficacy remains poorly understood, particularly in the context of clinical research on OUD. Our studies provide key insights into the molecular targets and neural circuitry responsible for the post-acute effects of PSI on OUD-related behaviors. In turn, these findings could guide future investigations into more direct and mechanistic clinical studies to determine the causal role of psychedelic-induced plasticity in sex-specific therapeutic outcomes.

Methods

Animals

Experiments were performed on adult (8-14 week-old) C57BL/6 J (Jackson Labs) male and female mice. For assays with 5-HT2AR (Htr2a) knockout mice16 (5-HT2AR-KO), heterozygous mice on a C57BL6/J background were bred to obtain 5-HT2AR-WT and 5-HT2AR-KO mice, and confirmed by genotyping tail snips. Sex classification of all mice was based on anogenital distance, in which males are characterized by a longer anogenital distance84. Animals were housed in cages with up to 4 littermates at 12 h light/dark cycle at 23 °C with food and water ad libitum, except during behavioral testing. Experiments were conducted in accordance with NIH guidelines, and were approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Animal Care and Use Committee (#AD10001212). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and the number of animals used. All behavioral experiments were completed by female identifying individuals.

Drugs

Psilocybin (free base) was purchased from Usona Institute. (R)-(+)-α-(2,3-dimethoxyphenyl)−1-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl]−4-piperinemethanol (volinanserin, or M100907), ( ± )−1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)−2-aminopropane (DOI) hydrochloride, and oxycodone hydrochloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. For osmotic minipump administration and tail-flick studies, oxycodone was obtained from Durect Corporation. All drugs were dissolved in saline (0.9% NaCl) to the appropriate volumes (5 or 10 μl/g body weight) and doses for intraperitoneal (i.p.) and subcutaneous (s.c.) administration. Vehicle-treated condition denotes administration of saline solution given to the equivalent volume of the drug administered.

Viral vectors

Adeno-associated viral vector constructs pAAV-EF1α-mCherry-IRES-Flpo (55634), pAAV-EF1α-fDIO-Cre-IRES-eYFP (121675), and pAAV-EF1α-fDIO-eYFP (5564) were purchased from Addgene. Viral preparations (AAV retrograde and serotype 8) were produced by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Vector Core. We selected AAV8 because among the AAV serotypes cloned and engineered for production of recombinant vectors, AAV8 has shown a tremendous potential for gene delivery in structures including the frontal cortex85. Herpes simplex 2 viral vector construct encoding GFP under the CMV promoter (HSV-GFP) has been previously described86. Viral particles were packaged by the Gene Delivery Technology Core at the Massachusetts General Hospital.

Tissue Sample Collection

The day of the experiment, mice were sacrificed for analysis by cervical dislocation, and bilateral frontal cortex (bregma 1.9 to 1.40 mm) and NAc (bregma 1.2 to 1.5 mm) were dissected, and either frozen at −80 °C, or immediately processed for RNA extraction and/or biochemical assays.

Psilocin distribution

Blood and brain tissue samples were obtained from male and female mice following PSI (1 mg/kg) administration. Mice were decapitated 30 min, 1 h and 4 h after drug administration; controls were mock-injected mice. Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatograph tandem mass spectrometer (UHPLC-MS/MS) assays in blood and frontal cortex samples were performed as previously reported27,29. Noncompartmental pharmacokinetics were calculated using the trapezoidal rule, with minor modifications27,29.

Head twitch response

Detection of head-twitch responses (HTR) in mice was performed as previously reported87,88, with additional visual inspection. Briefly, mice were ear-tagged with neodymium magnets (N50, 3 mm diameter × 1 mm height, 50 mg) glued to the top surface of aluminum ear tags for rodents (Las Pias Ear Tag, Stoelting Co.) with the magnetic south of the magnet in contact with the tag. Following ear-tagging, animals were placed back into their home cages and allowed to become accustomed to the tags for one week. Data acquisition and data processing was performed as previously described87,88, using our signal analysis protocol in combination with a deep learning-based protocol based on scalograms. Testing occurred no more than once per week with at least 7 days between test sessions. On test days, mice were placed individually into the monitoring chamber for 15 min to acclimate to the environment and determine baseline HTR. Subsequently, the animals received the corresponding treatments and HTRs were recorded for 60 minutes.

Conditioned Place Preference