Abstract

Selective capture of nitrate from wastewater is crucial for ensuring safe drinking water and promoting resource circularity. This study investigated alkylated polyaniline redox polymers as highly-selective electrosorbents to address this challenge. By controlling polymer solvation properties through synthetic functionalization, poly(N-methylaniline) (PNMA) achieves a nitrate uptake of up to 1.38 mmol g−1-polymer and a separation factor of 7 over chloride. Poly(N-butylaniline) (PNBA) further enhances selectivity, achieving a separation factor beyond 14 due to increased hydrophobicity. The mechanisms underlying this selectivity are investigated using ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) and in-situ electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance (EQCM) studies, which reveal that hydrophobicity reduces chloride binding. A technoeconomic analysis indicates that methylation on PANI reduces nitrate removal costs by 50% compared to non-functionalized PANI, due to enhanced selectivity and uptake, and decreased energy consumption. PNMA electrodes demonstrate practical nitrate selectivity over 20 versus chloride in real wastewater, while avoiding sulfate binding. This study highlights the potential of controlling solvation at electroactive polymers to enhance nitrate selectivity, offering a promising design path for redox-mediated electrochemical separations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitrate, a prevalent nutrient in water, can cause adverse effects on the aquatic ecosystem such as eutrophication and coastal algal blooms1,2, while contamination in drinking water can increase health risks and even cancer3,4. Nitrate contamination is primarily driven by the widespread use of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers and nitrate runoff from agricultural practices5,6. Global nitrate emission from intensive agricultural production systems is predicted to reach 35.3 Tg-N yr−1 in 20307. Therefore, the World Health Organization (WHO) and US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have recommended maximum contaminant levels (MCL) of 11.3 and 10 mg L−1 NO3-N, respectively, for water supplies4,8,9. At the same time, nitrate has been proposed as a potential nitrogen source for ammonia production10,11,12, being considered as a promising alternative pathway over direct nitrogen conversion13,14,15,16. However, nitrate concentrations in contaminated wastewaters are often low (below 1 mM), and accompanied by competing ions such as chloride15,17,18,19, which decrease nitrate removal efficiency in separations20,21. At the same time, the presence of chloride can decrease the nitrate/ammonium conversion efficiency in electrochemical nitrogen recovery processes due to chlorine-mediated ammonium oxidation22,23. Thus, efficient nitrate-selective separations are critical for wastewater treatment and environmental remediation, as well as resource circularity. Here, we develop electrosorbents by leveraging the control of hydrophobicity of redox-polymers to enhance nitrate over chloride selectivity, to achieve a nitrate-selective electrochemical separation.

Electrochemical separation technologies such as electrodialysis and electrosorption have gained recent attention as sustainable nitrogen separation platforms that can decrease chemical usage compared to traditionally employed ion-exchange systems24,25,26,27. However, in recent studies, both methods have presented limited separation factors (SFs) of nitrate to chloride in the range of 1.2 to 3.228,29. Technoeconomic analyses suggest that further enhancement of SFs is needed to significantly reduce the water treatment cost for electrochemical nitrate removal to below 0.2 USD m−3 water30. From a physico-chemical standpoint, the major hurdle for achieving higher nitrate selectivity is the similarity between nitrate and chloride, due to their comparable size and same electrostatic charge, as well as close diffusion coefficients28. To enhance SFs for nitrate recovery, advances in molecular design and a deeper understanding of ion solvation, electrostatic interactions, and charge-transfer properties are essential to overcome the inherent limitations in traditional sorption systems31.

Redox-active polymers have emerged as a promising platform for designing ion-selective materials, offering tunable interactions and selective ion binding for various ion separation applications32,33,34,35. The electrochemical operation of redox polymers enables reversable ion binding and release by modulating electrochemical potential without the use of chemical regenerants36. The ion selectivity and electrochemical activity of redox polymers can be fine-tuned through the choice of redox centers and non-redox functional groups37. However, redox polymers yet to be extensively explored for selective nitrate separation and existing systems still present limited selectivity. Nitrogen-containing functional groups in polymers like polypyrrole (PPY) and polyaniline (PANI) have shown promising nitrate adsorption capacities in synthetic nitrate solutions38,39. More recently, a PANI composite carbon nanotube (CNT) electrode achieved a nitrate over chloride SF of 3.2 and over 1.13 mmol g−1-polymer of electrochemically reversible nitrate uptake by exploiting synergistic electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding in the emeraldine salt (ES) form of PANI40.

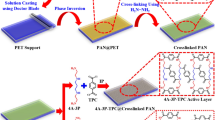

Notably, nitrate selectivity correlates strongly with Gibbs hydration energy, indicating that less hydrated nitrate is more favorably transported through the polymer film than chloride when ion dehydration occurs at the water-polymer interface41,42,43. To extend beyond the nitrate selectivity of conventional nitrogen-containing redox polymers, engineering a favorable solvation microenvironment by integrating additional hydrophobic groups in the polymer could be an effective strategy to enhance selectivity towards nitrate over similar-sized monovalent anions based on their distinct solvation properties. In this study, we report the design of highly nitrate-selective redox polymers by engineering the hydrophobicity of PANI through various alkylation types and ratios. These redox polymers were evaluated for electrochemically reversable nutrient separation and recovery as well as clean water production from wastewater streams (Fig. 1a, b).

The holistic approach we adopt encapsulates five stages, each of which contributes towards elucidating the underlying design principles and mechanisms for controlling selectivity, while presenting an electrochemically-mediated process for water treatment. First, we synthesize conventional PANI and alkylated PANI-based polymers (including poly(aniline-co-N-methylaniline) (PAMA), poly(N-methylaniline) (PNMA) and poly(N-butylaniline) (PNBA)) by electropolymerization on a CNT substrate and elucidate the relationship between material hydrophobicity and nitrate selectivity. Second, we investigate the selective binding mechanisms of nitrate and competing chloride ions on different alkylated PANI-based polymers through a combination of electronic structure calculations and electrosorption tests. Third, we explore the role of solvation on selective nitrate binding by using electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance (EQCM) and ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations. These methods provide complementary outcomes: the EQCM results yield solvent flux profiles of anion binding in polymer films, while the AIMD simulations unveil molecular insights into the solvation number of anions (i.e., populations) on the polymer binding sites. Fourth, turning from fundamental to more practical aspects, a techno-economic analysis (TEA) demonstrates how nitrate selectivity and uptake capacity of the redox polymers can affect water treatment costs for different water compositions. Finally, through proof-of-concept flow cell experiments, we integrate these fundamental and applied results to demonstrate the exceptional selectivity of PNMA for nitrate over competing anions in real wastewater, with remarkable electrochemical regeneration. Thus, we demonstrate how synthetic modification and in-depth molecular design of redox polymers can achieve superior molecular selectivity compared to state-of-the-art electrochemical systems.

Results and Discussion

Molecular design and characterization of alkylated PANI electrodes

Our design relies on the concept that by enhancing hydrophobicity in our redox-polymer, we can enhance the selectivity towards less hydrated anions such as nitrate. To investigate the impact of solvation on nitrate-selective transport in redox polymers, we electropolymerized PANI-based polymers with varying hydrophobicity onto CNT substrates. The hydrophobicity is manipulated through alkylation of the monomers, by varying both the ratio of alkylated/non-alkylated groups, and the length of the alkyl groups (Fig. 1a). A higher composition of alkylated groups and a longer length of the alkyl groups increase hydrophobicity. Here, PAMA represents 50% methylation, while PNMA and PNBA correspond to full methylation and full butylation, respectively on the amine groups on the PANI backbone (Fig. 1b). The alkylation strategy is expected to enhance hydrophobicity while preserving the redox-activity of the polymer (to enhance selectivity) and electrochemical regenerability.

The PANI-based polymers were grown on the CNT substrates through electropolymerization in 0.5 M H2SO4 (see “Methods” for polymer fabrication). The loadings of alkylated PANIs (3.5 ± 0.3 mmol g−1-CNT for PNMA and 3.1 ± 0.2 mmol g−1-CNT for PNBA) were significantly lower than that of non-functionalized PANI (11.6 ± 1.3 mmol g−1-CNT). The morphology of alkylated PANI/CNT electrodes were examined by using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscope (SEM), showing that the polymers were uniformly deposited on the CNT substrate as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3. Contact angle measurements were carried out as shown in Fig. 1c, demonstrating that alkylated PANIs showed significantly higher hydrophobicity with contact angles between 89 to 93°, greater than that of PANI (55° contact angle).

Additionally, we confirmed the chemical characterization of PANI backbone and differentiated the properties of alkylated polymers using FTIR and Raman spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Fig. 1d). The chemical bonds and structure of PANI and alkylated PANIs were characterized by FTIR (Supplementary Fig. 6). Since the electropolymerization reactions ended at 0 V vs. Ag/AgCl and the products were rinsed by DI water, the PANI-based polymers were mostly in the reduced leucoemeraldine salt (LS) form. The electrodeposited PANI shared similar characteristic IR peaks with reference samples of commercial PANI. The broad peak between 3200 to 3400 cm−1 is attributed to N-H stretching44,45. Among the polymers, only PANI showed an obvious N-H stretching peak and PAMA showed a small N-H stretching peak, indicating that the alkyl groups locate on the proton binding sites on amine groups in the alkylated PANIs. All PANI-based polymers showed the same peaks at 2900 cm−1, 1585 cm−1, 1497 cm−1, 1300 cm−1 and 1141 to 1162 cm−1 as well as 820 cm−1, corresponding to aromatic C-H stretching, quinonoid ring stretching, benzenoid ring stretching, C–N stretching of secondary aromatic amine and sulfate ions (remaining dopants from electropolymerization) as well as quinonoid ring deformation, respectively45,46.

The Raman spectra unveiled a distinct pattern of peaks in alkylated PANIs compared to PANI (Fig. 1d). The peaks at 1195 cm−1, 1520 cm−1, and 1616 cm−1 were especially exhibited in alkylated PANIs, and which are attributed to C–H in plane deformation, C = N stretching and C–C stretching, respectively47. On the other hand, the peaks at 1363 cm−1 and 1583 cm−1 (which represent the phenazine-like segment stretching and C = C quinonoid stretching, respectively48) were only displayed by PANI. Our physiochemical characterization results revealed that the alkylation on the amine groups on PANI increases the overall polymer hydrophobicity and alters their protonation properties.

Anion binding affinity and nitrate selectivity of alkylated PANIs

To evaluate the impact of synthetic functionalization of PANI on nitrate vs chloride selectivity, electrosorption experiments were conducted using a mixed solution of 5 mM NO3− and 5 mM Cl− (equimolar conditions) with PANI/CNT and varying alkylated PANI/CNT electrodes. The redox behavior of the polymers was characterized via cyclic voltammetry (CV) testing in 0.5 M NaNO3, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. The oxidation peaks of alkylated PANIs were approximately 0.14 V higher than that of PANI at 0.3 V vs. Ag/AgCl (Supplementary Fig. 7). To ensure the complete oxidation of the redox polymers, an oxidation potential of 0.5 V vs Ag/AgCl was applied. Figure 2a shows the anion uptake capacities of PANI and alkylated PANI/CNT electrodes. Virtually no anion uptake was observed in the blank CNT substrates (Supplementary Fig. 8), with nitrate electrosorption solely driven by the redox-polymer coatings. All PANI-based polymers showed a significant uptake towards nitrate, ranging from 0.89 to 1.38 mmol g−1-polymer, with PNMA exhibiting the highest nitrate uptake. In contrast, chloride uptake was overall lower in all alkylated PANIs (ranging from 0.04 to 0.21 mmol g−1-polymer) compared to the control PANI (0.27 mmol g−1-polymer). Notably, PNBA showed a negligible uptake of chloride. These results suggest that increased hydrophobicity in the redox polymer inhibited the binding of chloride ions. To further investigate the selective binding mechanism, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were carried out to determine the binding energy of each anion to the different PANI-based polymers (see “Methods” for calculation details). The optimized geometry of the anions bound to the polymers is shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. The DFT results shown in Fig. 2b reveal that the binding energy trends for each anion were consistent with the experimentally measured electrosorption uptake of the anions.

a Anion uptake capacity of PANI-based polymers and b DFT-calculated binding energy of NO3− and Cl− species bonded to emeraldine salt (ES) form of the polymers. c Separation factor of NO3− over Cl−, d energy consumption of the polymers. Heat maps of e the separation factor and f NO3− uptake capacity of the polymers in 5 mM equal molar NaNO3/NaCl mixed solution at various potentials in pH 7.6. Heat maps of g separation factor and h NO3− uptake capacity of the polymers in varied pH conditions at 0.5 V vs Ag/AgCl. The electrosorption experiments were carried out in 1 mL of 5 mM NaNO3 + 5 mM NaCl mixed solution. (See Supplementary Fig. 10a for anion uptake capacity per active site).

We note that a more negative binding energy (Gibbs free energy change upon binding, ΔG) corresponds to a more favorable ion-polymer binding. The predicted ΔG of nitrate binding to the polymers was consistently negative, ranging from −93.6 to −108.07 kJ mol−1, indicating a strong binding affinity of PANI-based polymers towards nitrate. On the other hand, the ΔG of chloride (more hydrated anion) binding was generally less negative than that of nitrate, indicating that PANI-based polymers provide less binding affinity towards chloride. Especially, PNMA and PNBA exhibited the least favorable ΔG values of +14.5 kJ mol−1 and +1.9 kJ mol−1 towards chloride, respectively, suggesting that the extra hydrophobic interaction from the alkylated groups causes the binding of chloride to be thermodynamically less favored (arguably disfavored). These small predicted free energies could be within the error of thermal fluctuations depending on temperature, and thus indicate the non-preferred sorption of chloride onto these highly alkylated materials. Figure 2c showed that the SFs (see “Methods” for calculation details) of nitrate over chloride increased significantly as the polymer’s hydrophobicity increased, with longer alkyl group chains. The SFs of PANI, PAMA, PNMA and PNBA were 4.4, 7.3, 7.2 and 14.6, respectively, (where SF ≤ 1 is defined as non-selective). Remarkably, SF enhancement by factors of 1.6 and 3.3 can be achieved by methylation and butylation on the amine groups of PANI, respectively, in comparison with that of PANI. Despite similar binding energy of nitrate to PNMA and to PNBA, higher nitrate uptake via PNMA was observed, implying that the longer alkyl chains in the polymer matrix could potentially increase steric hindrance for nitrate binding. Thus, proper tuning of the alkyl chain length is critical to achieve sufficient hydrophobicity to reduce the binding of hydrated competing ions while optimizing the accessibility towards binding sites for nitrate. Moreover, the alkylated PANI electrosorbents can be fully regenerated through electrochemical desorption at −0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl (Supplementary Fig. 10b), with all the selectively-bound nitrate being released by applying negative potentials. This nitrate-selective process significantly reduced the energy consumption (from 392 kJ mol−1-NO3− (PANI) to 215 kJ mol−1-NO3− (PNBA), Fig. 2d) and enhanced Faradaic efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 10c), demonstrating a significant promise for resource recovery (see “Methods” for calculation details of energy consumption).

To examine the nitrate binding affinity and selectivity of the functionalized redox-polymers, electrosorption tests were performed under different potential and pH conditions (Fig. 2e–h). Figure 2e shows that the switchable nitrate selectivity by changing working potential in neutral pH condition, and the SFs increased with higher polymer hydrophobicity at each potential. At 0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl, all alkylated polymers showed the highest nitrate uptake and excellent selectivity as described in Fig. 2a, c. When the applied potential was 0.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl, the SFs of PNMA and PNBA were close to infinity due to nondetectable chloride uptake, but the nitrate uptake of both polymers was substantially lower than the higher potential window (0.21 mmol g−1-polymer (PNMA) and 0.04 mmol g−1-polymer (PNBA), Fig. 2f).

The low chloride uptake at 0.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl was likely attributed to insufficient driving force from the electric fields to overcome the hydrophobicity of the electrosorbents. When the working potential was increased to 0.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl, the SFs of all the polymers decreased to a range between 2.5 to 4.5 due to enhanced chloride uptake, driven by higher electric field. Figure 2g highlights how nitrate/chloride SF depends on solution pH at 0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl (see “Supplementary Fig. 11” for estimation of pKa of PANI). In all pH conditions, the PANI-based polymers showed significant nitrate uptakes between 0.54 to 1.93 mmol g−1-polymer at 0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl (Fig. 2h). The alkylated PANIs exhibited higher nitrate selectivity in more acidic conditions, suggesting that the protonation of tertiary amine groups can enhance their affinity towards nitrate. At pH 2.1, the SFs of PNMA and PNBA could exceed 25. On the other hand, the alkylated PANIs at pH 10.3 had similar SFs to that of PANI, ranging from 3.6 to 5.3. Overall, our electrosorption heat maps in different potential and pH ranges can provide the optimal working conditions for selective nitrate separation applications using those alkylated PANIs.

Solvation effect on nitrate selectivity of alkylated PANIs

To comprehensively understand the effects of solvation phenomena on selective nitrate binding, we utilized a combination of EQCM measurements and AIMD simulations. The EQCM provides the solvent population changes (and the dynamics thereof), and AIMD provides the solvation number that represents the underlying thermodynamics of anion binding at active sites in the polymer film, as illustrated in Fig. 3. When the potential was swept from 0 to 0.5 V vs Ag/AgCl, the net population of expelled water molecules from the polymer films during anion binding were obtained by subtracting “theoretical” (ion transfer only) frequency change (ΔFtheo) from the observed (“experimental”) values of frequency change (ΔFexp) as shown in Fig. 3a–c. The observed frequency change represents the combined masses of ions and solvent transferred, while the theoretical value represents transfer of bare ions (calculated from ion molar mass, Faraday’s law and the electroneutrality condition; see “Methods” for detailed calculations of expelled water). Notably, four factors demonstrate that the films are acoustically thin (simplistically, “rigid”), enabling the EQCM frequency response data to be interpreted gravimetrically, using the Sauerbrey equation. First, we deliberately selected film thickness and resonator frequency (harmonic) parameters for which PANI films have been demonstrated to be in the rigid regime49 rather than the viscoelastic regime50. Second, the alkyl derivatives (PNMA and PNBA) are more hydrophobic, taking them further into the “rigid” regime. Third, quantitative interpretation of the low dissipation values (see Supplementary Fig. 12) satisfies the criterion for the absence of viscoelastic effects51,52 for all harmonics used. Finally, superposition of the overtone normalized frequency data in Fig. 3a–c is diagnostic for a rigid film. The EQCM results revealed that significantly fewer water molecules were expelled from the alkylated PANI films than from PANI films during their oxidation in both NaNO3 and NaCl solutions (Fig. 3e). In PNBA, approximately 0.11 mol and 0.03 mol of H2O molecules for each mol of polymer active sites were expelled from the polymer film in 10 mM NaNO3 and NaCl, respectively. These water expulsions from PNBA were approximately 25 and 12 times lower than for PANI exposed to the same concentrations of NaNO3 and NaCl, respectively, consistent with a more hydrophobic microenvironment (less water available to be expelled) in the polymer matrix of PNBA due to its butylated functionality.

EQCM frequency changes for fifth to ninth overtones as function of time recorded corresponding to the voltammetric response at scan rate of 20 mV s−1 of a PANI, b PNMA and c PNBA films on the 5 MHz quartz resonator in either 10 mM NaNO3 or NaCl solution under potential changes. The “theoretical” (ion only transfer, see text) frequency changes are presented as black dashed lines. Anion was denoted by A−. d Schematic of solvent fluxes on polymer films in a cross-sectional view. e Amount of expelled water molecules normalized by active site of the polymers calculated from the EQCM data. f Average solvation number of bound anion on amine group of the different polymers predicted by AIMD. g Snapshots of anions bound on PANI and PNBA in AIMD simulation were taken after 3 ps simulation.

As illustrated in diagram (Fig. 3d), our EQCM data suggest that the confined space of rigid polymer backbone matrix allows hydrated anions to bind to the polymer and leads to the expulsion of water from the film. The difference in hydrophobicity between alkylated PANIs and PANI observed in the EQCM measurements was consistent with the contact angle results reported in Fig. 1c. Notably, nitrate binding on the alkylated PANIs produced significantly higher response currents and correspondingly larger ΔFtheo (based on Faraday’s law) compared to chloride binding by the alkylated PANIs (at least more than 1.7 times higher, which is the ratio of molecular weight of nitrate over chloride, see “Methods” for calculations of ΔFtheo), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 13 and Fig. 3a–c. Meanwhile, nitrate binding resulted in a higher expulsion of H2O molecules compared to chloride binding (Fig. 3e). Consequently, nitrate exhibited a stronger binding affinity for the alkylated PANIs than chloride, as indicated by the relatively higher amount of expelled water. This binding affinity trend observed in the EQCM measurements aligns with the binding energy results shown in Fig. 2b.

EQCM measurements are complemented by AIMD simulations, showing that the average solvation number of bound chloride and binding distance between chloride ion and active sites followed the order of PNBA > PNMA > PANI (Fig. 3f, g and Supplementary Fig. 14, see “Methods” for computational details). The average hydration numbers for chloride binding to the amine sites on PNMA and PNBA were approximately 7.1 and 7.3 H2O molecules, respectively, both significantly higher than that of PANI, which had a hydration number of 5.5 H2O molecules (Fig. 3f). Here, the hydration number is derived from the solvent distribution (presented as a radial distribution function, RDF) around anions (Supplementary Fig. 15). The higher hydration number around chloride than nitrate reflects relatively higher hydrated property of chloride in the polymers during electrosorption. Furthermore, significant increase of hydration number and solvent distribution on chloride was observed when binding to a more hydrophobic film, suggesting that H2O molecules are repelled away from the hydrophobic polymer surface to chloride surface (Supplementary Fig. 15b). By examining the varied equilibrated time in AIMD simulation, the hydration number of bound and unbound ions on the polymers can be further differentiated. For nitrate (Supplementary Fig. 16a), the average hydration number slightly decreases in the unbound state for both PANI and PNBA, suggesting preferential binding of nitrate to these polymers. In contrast, for chloride (Supplementary Fig. 16b), the average hydration number increases in PNBA, along with the Cl− -polymer distance, indicating a tendency of chloride to be repelled from the polymer. A longer Cl−-polymer distance has been predicted in the unbound state on PNBA compared to NO3− as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 16c–f.

Additionally, the binding distances between chloride ions and the polymer active sites were predicted to be approximately twice as large for PNMA (6.3 Å) and PNBA (6.8 Å) compared to PANI (3.2 Å). These simulation results suggested that the polymer presents stronger repulsive interactions towards the more highly hydrated chloride, a trend which increases with the hydrophobicity of the polymer films. The higher solvation number and longer binding distance also explain the lower amount of expelled water during chloride binding from the EQCM results in Fig. 3e. The repulsion of chloride to the hydrophobic alkyl groups results in a low adsorption uptake experimentally, as seen from the lower simulated binding energy (Fig. 2b).

Additionally, the hydration number and binding distance for nitrate ions with PANI-based polymers were generally lower than those for chloride, indicating a less hydrated binding environment. The shorter binding distance between nitrate and the amine groups is likely due to charge-based interactions, rather than hydrophobic interactions that drive affinity with the alkyl groups. The higher adsorption uptake and binding energy of nitrate to both PANI and alkylated PANIs (Fig. 2a, b) provide evidence for the greater expulsion of water (Fig. 3e) and the closer binding (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 14) of nitrate to the polymers compared to chloride.

Technoeconomic analysis and applicability of alkylated PANI for real wastewater remediation

To compare the cost efficiency of alkylated PANI electrodes for nitrate separation and water treatment applications, we conducted a technoeconomic analysis based on the electrosorption testing results of batch reactor (Fig. 2a, c and d). To quantify the relative impacts of PANI-based polymer electrosoption capacity and selectivity for nitrate removal from drinking water, the costs attributed to the adsorption electrode were simulated for two scenarios. TEA scenarios included treating a nitrate impacted surface water source (Lake Decatur, IL) with near equal concentrations of nitrate and chloride (1.14 mM NO3−, 0.9 mM Cl−) and treating water with 10 times the original Cl− concentration to the drinking water MCL (0.7 mM NO3−) (see “Methods” and Supplementary Table 3–6 for detailed TEA calculations).

In the water price calculation, the contributions of different components were analyzed. The current collector and substrate were found to be the dominant cost factors, suggesting that substituting titanium mesh and CNT with stainless steel mesh53 and carbon black52, respectively, could significantly reduce the overall water price (Supplementary Table 6). The TEA results elucidate a tradeoff between nitrate uptake and selectivity. In both scenarios, PNMA exhibited the lowest nitrate removal price among the PANI-based polymers due to the balance between high total ion uptake capacity (1.59 mmol g−1-polymer) and high SF (7.2) (Fig. 4a, b). The higher uptake capacity of a polymer material lowers costs as it reduces the number of electrodes required to meet the nitrate maximum contaminant level (MCL) and therefore decreases the overall capital costs. The TEA results also showed how the concentration of competing anions can impact overall nitrate removal cost. In the low Cl− concentration scenario, uptake capacity is a more deterministic costing parameter than nitrate selectivity. Nitrate removal cost estimates for the alkylated PANI polymers that increased SF at the expense of uptake capacity were comparable to the non-alkylated PANI (Fig. 4a). The nitrate removal cost of PNMA was 0.047 USD m−3 water while the most nitrate-selective PNBA (with SF of 14.6) had the highest cost of 0.074 USD m−3 due to limited ion uptake (0.95 mmol gpolymer−1). On the other hand, the lowest nitrate selective PANI (with SF of 4.4) displayed the second lowest treatment cost of 0.066 USD m−3 due to its second highest uptake (1.22 mmol gpolymer−1). Additionally, PAMA and PNBA had extremely close costs because of their trade-off between uptake capacity and nitrate selectivity.

Water price prediction of removing NO3− from: a Decatur drinking water and b Decatur drinking water with 10 times Cl− background concentration using PANI, PAMA, PNMA and PNBA electrodes. c Photograph and schematic diagram of the electrosorption flow cell device. d uptake capacities, NO3− regeneration efficiency and e separation factor (SF) of NO3− over Cl−as well as energy consumption for nitrate removal of PNMA electrode with the tested wastewaters at 0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl.

In the high Cl− concentration scenario, the order of cost shifted into PNMA < PNBA < PAMA < PANI as shown in Fig. 4b. PNMA still showed the lowest cost of 0.091 USD m−3 among the polymers due to high ion uptake and sufficient nitrate selectivity. However, PNBA exhibited the second lowest cost of 0.111 USD m−3 and PANI had the highest cost of 0.169 USD m−3, highlighting the value of selectivity when the aqueous chloride concentration exceeds that of nitrate. High concentrations of competing ions can occupy the binding sites of the polymers and thus increase the required number electrodes required for sufficient nitrate removal. Therefore, more selective polymer becomes more cost effective in the higher salinity condition due to less capital costs on the required number of electrodes.

To validate applicability in real water matrices, we electropolymerized PNMA onto 5 × 5 cm2 CNT working electrode and investigated the nitrate separation performances of PNMA-CNT electrode in an electrochemical flow-cell with different nitrate-containing water streams (Fig. 4c, d). To evaluate the impact of nitrate concentration on selectivity and uptake, we compared the separation performances of the flow cell with the municipal secondary effluent stream from the wastewater treatment plant as a scenario of lower nitrate concentration and with the nitrate-contaminated groundwater as a scenario of high nitrate concentration. In the tested municipal wastewater, the competing anions were mainly chloride (3.6 mM) with low contents of divalent sulfate (0.34 mM) and nitrate concentration were 0.8 mM as listed in Supplementary Table 7. On the other hand, the groundwater sample contained nitrate as main species (1.5 mM) and minor amounts of chloride (0.18 mM) and sulfate (0.21 mM) as listed in Supplementary Table 8.

Figure 4e demonstrated that nitrate was the major species removed by using the PNMA electrode. Nitrate uptake capacities of 0.42 and 1 mmol g−1-polymer were achieved at 0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl in the municipal wastewater and groundwater, respectively. On the other hand, chloride was less favorable to be adsorbed by PNMA. Nearly no chloride uptake was observed in the higher nitrate contained groundwater compared to that in the municipal wastewater (0.33 mmol Cl− g−1-polymer). Figure 4f exhibited that the SFs of NO3− over Cl− were 6.9 and above 20 (nearly no Cl− uptake), showing that PNMA has an exceptional selectivity towards nitrate. In higher initial nitrate concentration, nitrate ions can further outcompete chloride ions from the polymer binding sites, leading to a greater uptake and selectivity. Moreover, the electrosorbed nitrate can be fully regenerated by PNMA through reversing the voltage (at −0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl) as shown in nitrate regeneration efficiency of Fig. 4e and the conductivity profiles of Supplementary Fig. 17. To further investigate the effect of competing ions on nitrate selectivity, we conducted the electrosorption screening tests using 1 × 1 cm2 PNMA electrodes with an agriculturally based wastewater containing higher background of competing ions including SO42− and PO43− (Supplementary Table 9). Our results indicated that the existence of SO42− and PO43− could not significantly outcompete the binding of NO3− to PNMA as shown in Supplementary Fig. 18; SO42− is less favorable to be adsorbed and the specific binding of PO43− cannot be regenerated (Supplementary Table 10). Especially, the wastewater testing results are consistent with the electrosorption results with salt solutions with SF of 7.2 (Fig. 2b). Additionally, no sulfate uptake was detected during electrosorption in both wastewaters, implying that PNMA (by virtue of the hydrophobic methyl groups) can fully inhibit the binding of highly hydrated sulfate (with Gibbs hydration energy of −1080 kJ mol−1 43,) in the low concentration range (Fig. 4g). The energy consumption for nitrate separation decreased by 73% (from 979 kJ mol−1-NO3− to 266 kJ mol−1-NO3−) when the influent nitrate concentration increased from 0.78 mM to 1.5 mM and 10 times lower of competing ions as shown in Fig. 4f. Compared to the results with synthetic nitrate salt solution (Fig. 2a and c), the electrosorption of nitrate from municipal wastewaters yielded a decreased uptake and required higher energy consumption. This varied energy consumption in different nitrate concentrations reflects that mass transfer of the target ion at the selective electrosorbent interface is the limiting factor. Moreover, our long-term cycling stability tests showed that PNMA demonstrated the highest stability after 1000 cycles of charge-discharge among the functional PANIs, and that the extent of capacity loss of polymers is determined by the operating conditions (Supplementary Fig. 19). We observed the reduced capacity of polymer was caused by degradation of the polymer chains (Supplementary Fig. 19d). On the other hand, organic matter from real wastewater (e.g., such as the chemical oxygen demand (COD) contents in Supplementary Table 7–9) may foul the electrode surface, thereby reducing the longevity and selectivity of PNMA electrode. Organic compounds such as humic substances and proteins tend to bind to hydrophobic functional groups on electrode surfaces, leading to competitive sorption on the ion-binding sites and altering the chemical properties at the interface54. Therefore, future efforts should not only focus on improving both the mechanical and electrochemical stability of the redox-polymers but also on optimizing the surface chemical properties to minimize fouling effects. Overall, the flow cell results suggest that the PNMA can be applied to a scale-up system for nitrate separation from real wastewater. The PNMA electrosorbent can achieve high nitrate-over-chloride selectivity (SF > 20) and high removal rate (83 g-NO3− L−1 min−1 g−1-polymer, Supplementary Fig. 20) with full regeneration in mixed ion water streams, demonstrating that controlling the hydrophobicity of the electrosorbent interface is an effective strategy to improve ion selectivity for separation applications. The system developed in this study exhibits significantly lower energy consumption and competitive treatment cost compared to existing nitrate removal technologies (Supplementary Table 10). However, further experimental validation and modeling are required to more accurately assess its scalability for practical applications.

In summary, we present a fully electrochemically-controlled separation platform for nitrate removal, by pursuing a molecular design strategy that enhances nitrate-over-chloride selectivity in redox-polymers. By incorporating different alkylation patterns on a PANI backbone, we achieved high nitrate uptake (1.38 mmol gpolymer−1) and exceptional nitrate selectivity with respect to chloride (up to 14.6). The electrosorbents also demonstrate remarkable regeneration, with over 95% of the nitrate being released by electrochemical potential. A combination of electrosorption and AIMD simulations showed that alkylated PANIs exhibit strong binding affinity for nitrate via amine groups along with hydrophobic repulsion of chloride due to alkyl groups, leading to high selectivity towards nitrate. Longer alkyl chains on the conducting polymers not only increased the hydrophobicity of the polymer films but also reduced the transport of more hydrated competing anions. Hydrophobic interactions explain the reduced expulsion of water, along with the higher solvation number of bounded chloride and longer binding distance between chloride and the polymer. TEA results illustrated that the total ion uptake plays a more critical role under lower competing ion concentration on nitrate removal cost, and selectivity becomes dominant at higher competing ion concentration. The TEA provides guidance on the selection of the most cost-effective electrode materials for nitrate ion recovery in different wastewater matrices. Flow cell experiments using PNMA electrodes with municipal wastewater and nitrate-contaminated groundwater demonstrated a high nitrate selectivity over chloride (SF up to above 20) and avoided binding of sulfate, showing the feasibility of using alkylated PANI electrodes for resource separation applications. Overall, this solvation-based molecular design offers a new strategy for developing ion selective materials for more sustainable resource mining and recovery from wastewater.

Methods

Fabrication of NO3 − selective redox polymers

CNTs were utilized as the conductive substrate for electropolymerization. The CNT was dispersed in dimethylformamide (DMF) in a ratio of 6 mg mL−1 to obtain a slurry by sonicating in an ice / water bath for over 3 h40. For the electrosorption tests, the CNT slurry was drop-cast on one side of a Ti mesh strip with an electrode size of 1 × 1 cm2, followed by solvent evaporation in an oven at 60 °C for 2 h. PANI-based redox polymers including PANI, PAMA, PNMA, PNBA were electropolymerized onto the CNT electrodes from 0.2 M monomer + 0.5 M H2SO4 solution by running 10 cyclic voltammetry cycles at scan rate of 50 mV s−1 in a potential window between −0.2 V to 0.9 V vs. Ag/AgCl. After the electropolymerization reaction, the polymer/CNT electrodes were sequentially rinsed in 0.1 M H2SO4 solution and deionized water (DI, 18.2 MΩ) to eliminate residual monomers presented on the electrodes, followed by overnight drying at 60 °C. For the flow cell experiment, PNMA/CNT and cation exchange membrane (CEM)-covered CNT electrodes were used as working and counter electrodes, respectively, and with an effective area of 5 × 5 cm2. For fabrication of PNMA/CNT working electrodes, 90 mg of CNT and 10 mg of PVDF were mixed in 10 mL of DMF by sonication and drop-cast on a Ti current collector plate. After drying in an oven at 60 °C for 3 h, the CNT electrode was trimmed into a 5 × 5 cm2 square and then PNMA was polymerized onto the CNT using the same procedure as for 1 × 1 cm2 electrodes. For fabrication of the counter electrodes, 90 mg of CNT and 10 mg of PVDF were mixed in 10 mL of DMF by sonication, and the CNT slurry was coated onto the Ti plate by using a doctor blade with a height setting of 1.5 mm. The wet CNT film electrode was heated in an oven at 60 °C for 3 h to evaporate the solvent and the dry CNT electrode was trimmed to the working area size.

Electrosorption testing

All electrosorption tests of the alkylated PANI/CNT electrodes were conducted in the cuvette cell (Supplementary Fig. 21) with 1 mL of 5 mM NaNO3 + 5 mM NaCl mixed solution at constant voltages. To avoid any Cl− contamination of the test solution from the Ag/AgCl reference electrode, a leak-free Ag/AgCl electrode (Innovative Instruments, Inc., LF-1-100) was utilized for all the electrosorption tests. Before the electrosorption tests, the alkylated PANI/CNT electrodes were conditioned by applying −0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 30 min to release the dopants (SO42−) from the electropolymerization reactions and the electrodes were switched to another fresh NaNO3/NaCl mixed solution for the electrosorption tests. During the electrosorption tests, the working electrode was set at 0 V vs. Ag/AgCl in the beginning and applied constant voltages at 0.5 V and −0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl for charging and discharging steps, respectively. Each step was performed for 30 min and 1 mL of the mixed salt solution was sampled; the electrodes were switched to another fresh solution for the next step. The effect of redox state on nitrate selectivity of alkylated PANI electrodes was examined at open circuit potential (OCP), 0.2 V, 0.5 V and 0.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl. The effect of protonation on nitrate selectivity of alkylated PANI electrodes was examined at pH 2.1, 4.8, 7.6 and 10.3 at 0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl. The above-mentioned pH range spans pKa1 and pKa2 of PANI, according to the titration experiment (Supplementary Fig. 11). The pH of 5 mM equal molar NaNO3/NaCl mixed solution was controlled by adding either HCl or NaOH. The anion concentration of the water samples was analyzed by using ion chromatography (IC) (Thermo Scientific, Dionex™ Aquion™) combined with an anionic column (Thermo Scientific, Dionex™ IonPac™ AS22 IC Columns) and an auto sampler (Thermo Scientific, AS-DV). The concentration of nitrate and chloride was derived from the peak area calibration curves of standard solutions (5, 10, 20, 30, 40 mg L−1). An eluent solution of IC comprises 4.5 mM Na2CO3 with 1.4 mM NaHCO3 and was run at 35 °C with a flow rate of 1.2 mL min−1.

The performance indicators of electrosorption tests including uptake capacity of anions, removal efficiency, mean removal rate, SF, energy consumption, Faradaic efficiency and regeneration efficiency were calculated using the following equations:

where \({C}_{{\rm{x}},0}\), \({C}_{{\rm{x}},{t}_{{\rm{ch}}}}\) and \({C}_{{\rm{x}},{t}_{{\rm{dis}}}}\) represent concentrations of specific anion x at initial time and at charging time tch as well as tdis (here charging and discharging time were set as 30 min), respectively; I, V, v, and m are current response, applied voltage, volume of treated salt solution and mass of the polymer, respectively.

EQCM for film solvation characterization

The film solvation profiles were obtained by using EQCM with dissipation monitoring (BioLogic, BluQCM QSD and SP-200 potentiostat). Quartz sensors (QuartzPro, Au/Cr, diameter of 14 mm) with a fundamental resonance frequency of 5 MHz were employed for EQCM measurements. The thin-layer alkylated PANI films were electrodeposited on the quartz sensors by running 2 potentiodynamic cycles (scan rate 50 mV s−1; potential window between −0.2 to 0.9 V vs. Ag/AgCl) with a monomer solutions consisting of 0.2 M monomer + 0.5 M H2SO4. The deposited polymer films were rinsed in DI water and then dried at room temperature. To investigate the water flux into / out of the polymer films during electrosorption of different anions, the polymer films were potentiodynamically cycled (scan rate 20 mV s−1, between −0.2 to 0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl) in either 10 mM NaNO3 or 10 mM NaCl solution, and the EQCM frequency response monitored. The calculation details yielding the water flux are described in Supplementary Information.

Computational details

All simulations were performed in Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP) 5.4.455,56. The periodic polymer unit cells of PANI, PAMA, PNMA, and PNBA, each consisting of eight elementary units, were constructed using VESTA57. The cell dimensions were defined as a × b × c Å3, where a represets the optimized cell dimension of the aligned polymer. The values of b and c were set to 25 Å to minimize interactions between periodic images. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)58,59 functional within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) was utilized to treat exchange-correlation interactions. Grimme’s D3 dispersion correction60,61 was used to consider the long-range van der Waals interactions. A cutoff energy of 500 eV was applied in all DFT calculations. The convergence criteria for energy and atomic forces during structural optimization were set to 10−6 eV and 0.02 eV Å−1, respectively. Solvation effects were considered, using an implicit solvation approach. Prior to the optimization, at least 2 ps AIMD in implicit solvent simulations were performed to identify the most favorable structures. A time step of 1.0 fs and the H mass of 1 amu were set. The Nose-Hoover thermostat maintained the temperature at around 300 K.

The binding energies between the polymer and the adsorbates were calculated following the methodology outlined in our previous publication40:

where E*ads is the DFT energy of polymer in the presence of an adsorbate (Cl−, NO3−), E* is the DFT energy of the pristine structure, ∆Gads is the Gibbs free energy change of Cl− and NO3−, n is the number of adsorbed species.

To investigate the behavior of ions near the polymer film in a realistic aqueous environment, we performed AIMD simulations with explicit solvation. We filled a simulation box with dimensions a × b × c Å3 with 143-150 water molecules to maintain a water density around 1 g cm−³. Dimension a was defined by the four elementary units, while b and c were set to 20 Å each. The system was equilibrated for 1 ps, followed by a 3 ps production run. The number of H2O molecules between the amine group in the polymer and nitrate or chloride ions was determined by the RDF as shown in Supplementary Fig. 15; The average hydration number was determined by integrating the first peak of the RDF up to the cutoff distance. The distances between the nitrogen atoms in the polymer (-N-) and the nitrogen in nitrate or chloride ions were chosen to determine the average distance between the polymer and the ions.

Technoeconomic analysis details

The cost calculation is based on the batch reactor configuration, containing consumable materials of the working electrode and electricity consumption of adsorption and desorption process. Polymer and carbon black were considered to calculate the total capital cost using the following equation:

where Cc, is the electrode capital cost; Cp, Cca, Ccc are the unit price for polymer, based on lab production procedure, and carbon material, and current collector based on the market price, respectively; Mp and Mca indicates the mass of polymer and carbon material used for each experiment, respectively. With the charge passed through the electrode during adsorption and desorption steps at constant operating voltage, the electricity cost can be calculated using:

where Ce is the electricity cost; q is the applied total charge; V is the applied voltage; Pe is the electricity price (The average price of electricity for industrial sectors in Illinois state was 0.08 USD kWh−1 according to U.S. Energy Information Administration); I and t are the current response and operation time, respectively (See “Supplementary Table 3” for details of input parameters for TEA model). We assumed that the electrode reached a steady state with constant capacitance and electricity consumption and the ohmic potential drops were not considered. Regarding the adsorption uptake, we only consider the regenerable amount of ion uptake according to the discharging step, and then define it as true uptake capacity. The true uptake capacity (Ct) was used to calculate the required number of experiments to treat the water to target nitrate concentration of MCL and it can be calculated by the following equation:

where Cc is the experimental nitrate uptake capacity during the charging step and R is the regeneration efficiency, which was assumed as 1 (fully regenerated) according to the experimental observation from the electrosorption testing. The simulated water composition and final nitrate concentration after electrosorption treatments for the TEA model were listed in Supplementary Table 4. To size the system, a range of parameters were considered, including performance indicators (P uptake, charge passing, selectivity), electricity cost, as well as fixed parameters such as material unit price, operational settings (adsorption and desorption voltages and times), configuration details (material consumption and treatment volume per reactor), and scenario factors (initial concentration, regeneration efficiency) (Supplementary Table 4). A Monte Carlo simulation was employed, applying a uniform distribution across the value ranges of the variable parameters to account for uncertainty in the results62. Ten thousand costing simulations were run for systems incorporating different coating strategies and materials.

Flow cell experiments

The flow cell consists of a PNBA/CNT working electrode, CEM-covered CNT counter electrode and leak-free Ag/AgCl reference electrode as well as a rubber gasket frame (for creating spaces of water flow) as shown in Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 22. The effective area of the working and counter electrodes is 5 × 5 cm2 and volume between the above-mentioned electrodes is approximately 2.5 mL. The potentials of working electrode were set at 0.5 V and −0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl for charging and discharging stages, and each stage was set as 30 min. The flow cell was fed with nitrate-containing wastewater from the municipal wastewater treatment plant (Supplementary Table 7) as received and nitrate-contaminated groundwater collected from Nebraska (Supplementary Table 8). The total treated volume of wastewater was 25 mL, which was continuously fed into the flow cell in a closed loop at a flow rate of 20 mL min−1. The flow cell-treated wastewater was sampled at the end of charging and discharging stages.

Data reporting

Each electrosorption set in Fig. 2a, c, d and Supplementary Fig. 18a was repeated at least in triplicate (sample size was between 3–5) and the experimental results were obtained from independent experiments with distinct electrode materials and water samples. The error bars were derived from the standard deviation of the data set. The ion and organic matter concentrations of each real wastewater sample was measured repeatedly in triplicate using the same water sample (Supplementary Table 7 to Supplementary Table 9).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of the study are included in the main text and supplementary information files. Source data are provided with this paper. Raw data can be obtained upon request to the corresponding author. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Liu, X. et al. Impact of groundwater nitrogen legacy on water quality. Nature Sustainability, 1-10 (2024).

Ascott, M. J. et al. Global patterns of nitrate storage in the vadose zone. Nature Communications 8, (2017).

Pennino, M. J., Compton, J. E. & Leibowitz, S. G. Trends in drinking water nitrate violations across the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 13450–13460 (2017).

Ward, M. H. et al. Drinking water nitrate and human health: an updated review. Int. J. Environ. Res. public health 15, 1557 (2018).

Hundey, E., Russell, S., Longstaffe, F. & Moser, K. Agriculture causes nitrate fertilization of remote alpine lakes. Nat. Commun. 7, 10571 (2016).

Ator, S. W., Blomquist, J. D., Webber, J. S. & Chanat, J. G. Factors driving nutrient trends in streams of the Chesapeake Bay watershed. J. Environ. Qual. 49, 812–834 (2020).

Eickhout, B., Av, B. ouwman & Van Zeijts, H. The role of nitrogen in world food production and environmental sustainability. Agriculture, Ecosyst. Environ. 116, 4–14 (2006).

Organization W. H. et al. Guidelines for drinking-water quality: first addendum to the fourth edition. (2017).

Daryanto, S., Wang, L. & Jacinthe, P.-A. Impacts of no-tillage management on nitrate loss from corn, soybean and wheat cultivation: A meta-analysis. Scientific Reports 7, (2017).

Wang, K. et al. Intentional corrosion-induced reconstruction of defective NiFe layered double hydroxide boosts electrocatalytic nitrate reduction to ammonia. Nat. Water 1, 1068–1078 (2023).

Fan, Y. et al. Highly efficient metal-free nitrate reduction enabled by electrified membrane filtration. Nature Water, 1-13 (2024).

Zhang, G. et al. Ammonia recovery from nitrate-rich wastewater using a membrane-free electrochemical system. Nat. Sustainability 7, 1251–1263 (2024).

Suryanto, B. H. et al. Challenges and prospects in the catalysis of electroreduction of nitrogen to ammonia. Nat. Catal. 2, 290–296 (2019).

Li, J. et al. Subnanometric alkaline-earth oxide clusters for sustainable nitrate to ammonia photosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 13, 1098 (2022).

Chen, F.-Y. et al. Efficient conversion of low-concentration nitrate sources into ammonia on a Ru-dispersed Cu nanowire electrocatalyst. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 759–767 (2022).

Chen, F.-Y. et al. Electrochemical nitrate reduction to ammonia with cation shuttling in a solid electrolyte reactor. Nat. Catal. 7, 1032–1043 (2024).

Kou, X. et al. Tracing nitrate sources in the groundwater of an intensive agricultural region. Agric. Water Manag. 250, 106826 (2021).

Kim, D. I. et al. Efficient recovery of nitrate from municipal wastewater via MCDI using anion-exchange polymer coated electrode embedded with nitrate selective resin. Desalination 484, 114425 (2020).

Fan, J. et al. Effects of ionic interferents on electrocatalytic nitrate reduction: mechanistic insight. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 12823–12845 (2024).

Bhatnagar, A. & Sillanpää, M. A review of emerging adsorbents for nitrate removal from water. Chem. Eng. J. 168, 493–504 (2011).

Mubita, T., Dykstra, J., Biesheuvel, P., Van Der Wal, A. & Porada, S. Selective adsorption of nitrate over chloride in microporous carbons. Water Res. 164, 114885 (2019).

Song, Q. et al. Mechanism and optimization of electrochemical system for simultaneous removal of nitrate and ammonia. J. Hazard. Mater. 363, 119–126 (2019).

Ma, X., Li, M., Feng, C. & He, Z. Electrochemical nitrate removal with simultaneous magnesium recovery from a mimicked RO brine assisted by in situ chloride ions. J. Hazard. Mater. 388, 122085 (2020).

Kikhavani, T., Ashrafizadeh, S. & Van der Bruggen, B. Nitrate selectivity and transport properties of a novel anion exchange membrane in electrodialysis. Electrochim. Acta 144, 341–351 (2014).

Chinello, D., de Smet, L. C. & Post, J. Selective electrodialysis: targeting nitrate over chloride using PVDF-based AEMs. Sep. Purif. Technol. 342, 126885 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Enhanced selective electrosorption of nitrate from wastewater by controllably doping nitrogen into porous carbon with micropores. Langmuir 40, 6353–6362 (2024).

Tsai, S.-W., Wu, M.-C., Ng, H. Y. & Hou, C.-H. Advancing the Electrosorption Selectivity of Nitrate Through Fine-Tuning Hydrophobic Ammonium Functional Groups in Anion Exchange Membranes for Membrane Capacitive Deionization. ACS ES&T Water, (2024).

Tsai, S.-W., Hackl, L., Kumar, A. & Hou, C.-H. Exploring the electrosorption selectivity of nitrate over chloride in capacitive deionization (CDI) and membrane capacitive deionization (MCDI). Desalination 497, 114764 (2021).

Shocron, A. N., Roth, R. S., Guyes, E. N., Epsztein, R. & Suss, M. E. Comparison of ion selectivity in electrodialysis and capacitive deionization. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 9, 889–899 (2022).

Hand, S. & Cusick, R. D. Emerging investigator series: capacitive deionization for selective removal of nitrate and perchlorate: impacts of ion selectivity and operating constraints on treatment costs. Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol. 6, 925–934 (2020).

Su, X. Electrochemical interfaces for chemical and biomolecular separations. Curr. Opin. colloid interface Sci. 46, 77–93 (2020).

Su, X. & Hatton, T. A. Redox-electrodes for selective electrochemical separations. Adv. Colloid interface Sci. 244, 6–20 (2017).

Chen, R. et al. Structure and Potential-Dependent Selectivity in Redox-Metallopolymers: Electrochemically Mediated Multicomponent Metal Separations. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2009307 (2021).

Mousset, E., Fournier, M. & Su, X. Recent advances of reactive electroseparation systems for water treatment and selective resource recovery. Current Opin. Electrochem. 42, 101384 (2023).

Candeago, R. et al. Unraveling the role of solvation and ion valency on redox-mediated electrosorption through in situ neutron reflectometry and Ab initio molecular dynamics. JACS Au 4, 919–929 (2024).

Su, X., Kulik, H. J., Jamison, T. F. & Hatton, T. A. Anion-selective redox electrodes: electrochemically mediated separation with heterogeneous organometallic interfaces. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 3394–3404 (2016).

Kim, N., Oh, W., Knust, K. N., Zazyki Galetto, F. B. & Su, X. Molecularly selective polymer interfaces for electrochemical separations. Langmuir 39, 16685–16700 (2023).

Shen, Y., Chen, N., Feng, Z., Feng, C. & Deng, Y. Treatment of nitrate containing wastewater by adsorption process using polypyrrole-modified plastic-carbon: characteristic and mechanism. Chemosphere 297, 134107 (2022).

Herath, A., Reid, C., Perez, F., Pittman, J.rC. U. & Mlsna, T. E. Biochar-supported polyaniline hybrid for aqueous chromium and nitrate adsorption. J. Environ. Manag. 296, 113186 (2021).

Kim, K. et al. Coupling nitrate capture with ammonia production through bifunctional redox-electrodes. Nat. Commun. 14, 823 (2023).

Luo, T., Abdu, S. & Wessling, M. Selectivity of ion exchange membranes: a review. J. Membr. Sci. 555, 429–454 (2018).

Epsztein, R., Shaulsky, E., Qin, M. & Elimelech, M. Activation behavior for ion permeation in ion-exchange membranes: role of ion dehydration in selective transport. J. Membr. Sci. 580, 316–326 (2019).

Marcus, Y. Thermodynamics of solvation of ions. Part 5.—Gibbs free energy of hydration at 298.15 K. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 87, 2995–2999 (1991).

Shao, W., Jamal, R., Xu, F., Ubul, A. & Abdiryim, T. The effect of a small amount of water on the structure and electrochemical properties of solid-state synthesized polyaniline. Materials 5, 1811–1825 (2012).

Husin, M. R. et al. Fourier transforms infrared spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction investigation of recycled polypropylene/polyaniline blends. Chem. Eng. Trans. 56, 1015–1020 (2017).

Trchová, M. & Stejskal, J. Polyaniline: the infrared spectroscopy of conducting polymer nanotubes (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 83, 1803–1817 (2011).

Wei, D. et al. Electrosynthesis and characterisation of poly (N-methylaniline) in organic solvents. J. Electroanalytical Chem. 575, 19–26 (2005).

Trchová, M., Morávková, Z., Bláha, M. & Stejskal, J. Raman spectroscopy of polyaniline and oligoaniline thin films. Electrochim. Acta 122, 28–38 (2014).

Hillman, A. R. & Mohamoud, M. A. Ion, solvent and polymer dynamics in polyaniline conducting polymer films. Electrochim. acta 51, 6018–6024 (2006).

Hillman, A. R., Mohamoud, M. A. & Efimov, I. Time–temperature superposition and the controlling role of solvation in the viscoelastic properties of polyaniline thin films. Anal. Chem. 83, 5696–5707 (2011).

Chen, R., Wang, H., Doucet, M., Browning, J. F. & Su, X. Thermo-electro-responsive redox-copolymers for amplified solvation, morphological control, and tunable ion interactions. JACS Au 3, 3333–3344 (2023).

Easley, A. D. et al. A practical guide to quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring of thin polymer films. J. Polym. Sci. 60, 1090–1107 (2022).

Lamiel, C., Hussain, I., Ma, X. & Zhang, K. Properties, functions, and challenges: current collectors. Mater. Today Chem. 26, 101152 (2022).

Kong, X., Zhang, C., Hou, C.-H., Waite, T. D. & Ma, J. Fouling in capacitive deionization: a critical review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 27, 13566–13584 (2025).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Computational Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Zhang, Y. & Yang, W. Comment on “Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 890 (1998).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. The J.Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Hand, S., Guest, J. S. & Cusick, R. D. Technoeconomic analysis of brackish water capacitive deionization: navigating tradeoffs between performance, lifetime, and material costs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 13353–13363 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the National Alliance for Water Innovation (NAWI), funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Office, Advanced Manufacturing Office under Funding Opportunity Announcement DE-FOA-0001905. The authors thank Dr. Johannes Elbert for advice on polymer chemistry and Trent Lyons for providing municipal wastewater samples, as well as Giovanny Dominguez for assistance with chromatography measurements. We would like to acknowledge startup funds at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and support through an Annual Research Grant from the Illinois Water Resources Center (IWRC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.W.T. and X.S. conceived the concept and designed the experiments. S.W.T. and C.Y.C. performed the experiments and analyzed the results. A.Z., M.F.C.A. and T.A.P. carried out the DFT calculation and analysis. Y.L. and R.D.C. performed TEA. C.Y.C. performed NMR and analyzed the data. R.C. conducted contact angles, Raman spectra and FTIR. S.W.T., A.R.H., J.F.B. and X.S. wrote and edited the manuscript. X.S. supervised the project. All authors revised and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yuren Feng, Liang An and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsai, SW., Zagalskaya, A., Li, Y. et al. Controlling solvation in conducting redox polymers for selective electrochemical separation of nitrate from wastewater. Nat Commun 16, 10207 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64895-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64895-w