Abstract

Two-dimensional (2D) nanosheet membranes exhibit promising H2 purification due to their atomic thickness. However, the synergistic interplay between in-plane pores and interlayer spacing on gas transport in 2D membrane has never been studied. Here, we engineer porous MXene nanosheets with artificially controllable in-plane pore to construct membranes with precise interlayer spacing, balancing the two types of channels for promising H2/CO2 separation. Optimal porous-MXene nanosheet membranes achieve a threefold increase in H2 permeance (1335 GPU) over nonporous-MXene nanosheet membranes (419 GPU) with comparable H2/CO2 selectivity (118). Theory and experiment demonstrate that the larger in-plane pores provide fast mass transfer channels enhancing H2 permeance, while smaller interlayer spacings as effective sieving channels govern selectivity. The Raman mapping visualizes H2 transport through in-plane pores. Manufacturing of meter-scale membranes underscores industrial viability. This work establishes universal design principles in high-performance 2D nanosheet membranes for separation, adsorption and catalysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrogen emerges as the 21st-century ultimate energy due to its environmental friendliness and minimal carbon emission1,2. Currently, over 90% of the global hydrogen is produced primarily through the steam reforming of natural gas. However, this production process yields various hydrogen-containing gas mixtures, especially H2 with CO23. The efficient separation of H2/CO2 is imperative for achieving carbon neutrality4. While conventional industrial techniques such as cryogenic distillation are energy-intensive, membrane separation offers a low-energy and high-efficiency alternative, making it a predominant option for H2 purification5,6,7,8,9. In recent years, two-dimensional (2D) nanosheets have flourished as membrane building blocks in H2 purification due to their atomic thickness, overcoming the trade-off between permeability and selectivity of traditional polymer membranes10,11.

Usually, graphene oxide (GO)12,13, MXene14,15,16,17 and MoS218 are employed to construct membranes, which have gained increasing attention due to their simple fabrication and scalability19,20. It should be noted that in the membranes comprising these above nonporous nanosheets, gas transport primarily occurs through interlayer channels between adjacent nanosheets, inevitably resulting in tortuous pathways and diminished separation efficiency. To shorten the pathway and enhance separation efficiency, porous nanosheets appear to assemble membranes, e.g., 2D zeolites21,22, 2D metal organic frameworks (MOFs)23,24,25, 2D covalent organic frameworks (COFs)26,27, g-C3N428,29, where the well-defined intrinsic in-plane pores promote efficient gas separation, but their interlayer spacings are usually negligible due to strong interactions and restacking between adjacent nanosheets23,30.

Therefore, current research continues to examine the separation mechanisms of these two types of membranes as isolated systems, employing either interlayer spacing or in-plane pores31,32. However, for membranes engineered from porous nanosheet building blocks, systematic investigation of the coordinated mass transport through both intrinsic nanopores and inter-sheet channels remains critically underexplored—a fundamental knowledge gap in membrane science that requires comprehensive mechanistic elucidation. Moreover, balancing the synergistic interplay between in-plane pores and interlayer spacing to achieve highly efficient gas separation remains a significant challenge.

To unravel the synergistic contributions of both intrinsic nanopores and inter-sheet channels to gas separation mechanisms, a systematic investigation integrating dual transport pathways is imperative. Herein, a kind of porous Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets (transition metal carbide) with artificially tunable nanopores are utilized as the building units to assemble membranes with controlled interlayer spacing, where a controllable and scalable O3 treatment strategy is utilized (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). Reasonable regulation of in-plane pores parameters including pore size and pore density and interlayer spacing can directly affect the effective sieving channels, and gas separation performance. The optimal porous-MXene nanosheet membranes with an in-plane pore size of 10 nm and a free interlayer spacing of 0.37 nm as sieving size, significantly shortening the gas transport pathway, thus exhibiting ~3 times higher H2 permeance (1335 GPU) compared to the nonporous-MXene nanosheet membranes (419 GPU), while maintaining high H2/CO2 selectivity of 118 (Supplementary Fig. 2).

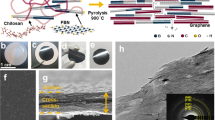

a Schematic illustration of preparing the porous MXene nanosheets by O3 strategy. b TEM, and (c) AC-STEM images of the nonporous MXene nanosheets. Insets are the corresponding SAED and IFFT patterns, Ti atoms are blue, C atoms are yellow, O atoms are red. d TEM, and (e) high-resolution TEM images of the porous MXene-O3-60s nanosheet. Insets are the corresponding SAED pattern. f AC-STEM, and (g) high-resolution AC-STEM images of the porous MXene-O3-60s nanosheet. h Average pore size, pore density, and porosity of the porous MXene nanosheets with different O3 treatment time followed by acid washing. i Pore formation mechanism for the multi-atom-thick monolayer MXene nanosheet. j O1s XPS spectra of the nonporous MXene and porous MXene-O3-60s nanosheets.

Furthermore, the individual contributions of in-plane nanopores and interlayer channels to mass transport in 2D nanosheet membranes remain unverified by real-time visualization characterization techniques. This study establishes an impactful methodology that conclusively addresses this critical research gap. The perpendicular H2 transport pathway through the in-plane nanopores of the porous-MXene nanosheet membranes is visualized using a Raman mapping characterization. Moreover, meter-scale spiral-wound and hollow fiber membrane modules show scalable manufacturing potential, advancing toward practical industrial gas separation implementations.

Results

Preparation and characterization of porous MXene nanosheets

The nonporous MXene nanosheets, prepared via chemical exfoliation as previously described33,34, exhibit an average lateral size of ~3.5 μm and a thickness of ~1.5 nm (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Figs. 3–6). The aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC-STEM) reveals their characteristic hexagonal symmetry (inset in Fig. 1b) and a nearly defect-free structure (Fig. 1c). Subsequently, the nonporous nanosheets were then subjected to O3 treatment and subsequent acid washing to obtain porous MXene nanosheets. During O3 treatment, partial regions of the nonporous MXene nanosheets are oxidized to TiO2 nanoparticles in aqueous solution (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1) according to Eqs. (1) and (2). O3 and ·OH radicals as O3 derivatives can indiscriminately attack the MXene nanosheets in aqueous solution due to their high redox potentials (2.07 V and 2.73 V, respectively), thus enabling homogenous in-plane oxidation of MXene nanosheets:

Following oxidation, the TiO2 nanoparticles are removed by acid washing, resulting in the porous MXene nanosheets with homogeneously distributed nanopores (Eq. 3):

As O3 treatment time increases from 30 s to 180 s, tiny amorphous TiO2 particles gradually transform into large crystalline anatase TiO2 particles on the MXene nanosheets (Supplementary Fig. 7). Upon further extending the O3 treatment duration to 300 s, the MXene nanosheets undergo severe degradation (Supplementary Fig. 8). Subsequent acid washing removes the TiO2 particles, leading to the formation of in-plane pores on the MXene nanosheets (Fig. 1d, e, Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10). The porous MXene nanosheets retain the single-crystal structure and exhibit a homogeneous pore distribution (Fig. 1f). For example, the porous MXene-O3-60s nanosheet (60s O3 treatment followed by acid washing) exhibits a large defect-free area with bright spots corresponding Ti atoms in the high-resolution AC-STEM image (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 11), the absence of bright spots indicates pore formation. Minor amorphization is observed at the pore edges, suggesting residual carbon following Ti removal (Fig. 1e)35.

Prolonged O3 treatment followed by acid washing generates MXene nanosheets with an increased pore size (8–20 nm) and pore density, yielding enhanced porosity and a significantly narrower pore size distribution compared to other porous MXene nanosheets reported in literature (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Fig. 10)36,37,38. Another key advantage of such O3 treatment strategy for pore formation is the homogeneous pore distribution, quantified by calculating the mean distance between the TiO2 particles formed through oxidation and leaving pores after acid washing (Supplementary Fig. 12)39. It is known that O2 preferentially oxidizes the edge sites of the MXene nanosheets (abnormal distribution), because its relatively low redox potential (0.82 V) is insufficient to overcome the relatively high defect formation energy on the basal plane40. In contrast, O3 treatment yields a more homogeneous pore distribution (normal distribution), attributed to the higher redox potentials of O3 (2.07 V) and ·OH radicals (2.73 V), facilitating homogeneous oxidation41,42. In comparison, H2O2 treatment can cause non-uniform pores and structural damage in MXene nanosheets due to the aggressive liquid-liquid interaction between H2O2 and the MXene nanosheets suspension (Supplementary Fig. 13). Compared to porous GO, porous MXene possesses more controllable pore size and pore distribution, uniform functional groups and enhanced nanosheet rigidity. Although MXene is susceptible to oxidation, its membranes remain stable in gas separation due to operation within light-tight testing cell under a reducing atmosphere (like H2/CO2). The N2 adsorption analysis further confirms the increased specific surface area and pore size of the porous MXene-O3 nanosheets (Supplementary Fig. 14). This finding indicates that such pore-forming strategy only perforates the MXene nanosheets without compromising their overall structural integrity (Supplementary Figs. 15–17).

Inspired by the interplay of crystal nucleation and growth43, the pore formation mechanism for multi-atom-thick monolayer MXene nanosheets can be conceptualized as a three-stage process (Fig. 1i). In stage I, short-term O3 exposure attacks the top and bottom Ti layers, forming pit-shaped defects (pore nuclei) on the nanosheet. In stage II, these nuclei grow into through-holes as O3 exposure time increases, while new pore nuclei continue to form. In stage III, further extension of O3 treatment time leads to hole expansion, increasing both pore size and pore density as new pore nuclei continue to form and grow. In this work, O3 enables the generation of high-density pore nuclei on the MXene nanosheets in a short time, thus facilitating the kinetic matching of pore nucleation and growth to obtain numerous small pores rather than a few large ones.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) and etching X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) confirm the increased atomic content of C and O and the decreased atom content of Ti and F in the porous MXene-O3-60s nanosheets (Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). This indicates that O3 selectively etches Ti atoms, preferentially breaking Ti-F bonds while leaving C atoms behind, and unsaturated Ti atoms readily bond with O atoms. The O 1 s XPS spectra exhibit a higher proportion of C-Ti-OH (36.1%) in the porous MXene-O3-60s nanosheets compared to that in the nonporous MXene nanosheets (13.8%) (Fig. 1j and Supplementary Table 3). Further analysis reveals that the concentration of -OH groups in the porous MXene nanosheets increases from 18.4% to 39.1% compared to the nonporous MXene nanosheets, while the proportions of =O and -F groups decrease from 60% and 21.6% to 44.9% and 16%, respectively. These changes arise from Ti-F and Ti–O bonds cleavage, but increased exposure of Ti atoms at the pore edges binding with −OH groups for saturation of the pore wall after pore formation (Supplementary Fig. 20). The above results demonstrate that the pore structure and chemical composition of the MXene nanosheets can be modulated using such a controllable O3 strategy.

Formation and characterization of porous-MXene nanosheet membranes

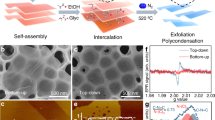

Taking advantage of the strong negative Zeta potential (Supplementary Fig. 21), 500-nm-thick membranes have been fabricated using the MXene nanosheets suspended in water as building blocks on nylon substrates via electrophoretic deposition (EPD) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 22)16,44. The nylon substrate was chosen due to its excellent mechanical strength and chemical compatibility (Supplementary Fig. 23). Both the deposited nonporous and porous MXene nanosheets exhibit well-defined lamellar structures of the membrane stack (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 24). The highly ordered laminar structures of both nonporous-MXene and porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membranes are further resolved in the AC-STEM (Fig. 2c–e). From the cross-section view, the porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membrane exhibits a distinct stack structure and maintains the same interlayer d-spacing of 1.37 nm as the nonporous-MXene nanosheet membrane. Further XRD analysis reveals that the free interlayer spacings of both the porous-MXene-O3-30s and 60 s nanosheet membranes are 0.37 nm after subtracting the theoretical monolayer nanosheet thickness of ~1 nm, consistent with the nonporous-MXene nanosheet membrane (Fig. 2f), and corroborating the TEM results (Fig. 2c–e). This finding indicates that short-time O3 treatment does not significantly alter the interlayer structure of the MXene nanosheet membrane. However, the d-spacing of the porous-MXene-O3-180s nanosheet membrane increases to 1.42 nm, potentially attributed to the localized formation of amorphous carbon residues at the pore edges during prolonged O3 treatment. These carbon residues, acting as intercalating agents, can lead to an increased d-spacing, which is in accordance with the literature35,45,46. AFM measurements of the membrane series reveal progressively lower Ra (Roughness average) and Rq (Root mean square roughness) values with increasing O3 treatment, suggesting that the membranes become smoother (inset of Fig. 2b, Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 25), possibly due to the increased abundance of -OH groups on the porous MXene nanosheets.

a Schematic illustration of the fabrication of nylon-supported porous-MXene nanosheet membranes via EPD strategy. b Cross-sectional SEM image of the porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membrane. Inset is the SEM image of the membrane surface. Cross-sectional AC-STEM images of the (c) nonporous-MXene and d porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membranes. Insets are the corresponding IFFT of c and high-resolution images of (d). Ti and C atoms are blue and yellow, respectively. e Line intensity profile acquired along the yellow square in (c) and blue square in (d). f XRD patterns of nylon, nylon-supported nonporous- and porous-MXene nanosheet membranes. g Surface roughness comparison of the membranes. Insets are the corresponding 3D AFM images.

Membrane separation performance and mechanism

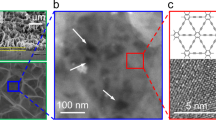

The mixed-gas H2/CO2 separation performance of the nonporous- and porous-MXene nanosheet membranes was assessed using the Wicke–Kallenbach method (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Fig. 26)31. The nonporous-MXene nanosheet membranes (O3-0 s) demonstrate a H2 permeance of 419 GPU and a H2/CO2 selectivity of 161, exhibiting lower gas permeance compared to our previous results14 due to the varied lateral size of the MXene nanosheets. With increasing O3 treatment, the H2 permeance of the membranes gradually increases, while the H2/CO2 selectivity only slightly decreases up to 60 s treatment, suggesting that the formation of in-plane nanopores accelerates gas transport. To visualize the contribution of in-plane nanopores to the overall H2 permeance, an advanced Raman study was developed and applied for the membranes assembled by nonporous and porous MXene nanosheets with average pore sizes of 8 nm, 10 nm, and 20 nm, prepared using different O3 treatment times of 30 s, 60 s, and 180 s.

a Mixed H2/CO2 separation performance of the 500-nm-thick nonporous-MXene nanosheet membranes and the porous-MXene nanosheet membranes after O3 treatment for different time. AFM images of the b nonporous- and (c) porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membranes/VOx heterostructure (left). Raman peak area mapping at 197 cm−1 is shown before (0 h, top right) and after H2 passing through (3 h, bottom right). d Raman peak area ratio of 197 cm-1 before (A0) and after (A) H2 passing through the nonporous- and porous-MXene nanosheet membranes under the same roughness (19≤Ra≤20). The error bars in Fig. 3a, d denote the standard deviation obtained from measurements of three identically prepared membranes. e Four models of possible mass transport pathways through porous nanosheets assembled membrane. d1, d2, d1’, and dgas represent in-plane pore size, free interlayer spacing, overlapping pore size between adjacent porous nanosheets, and kinetic diameters of gas molecules, respectively. f Overlapping probability of the in-plane pores in the porous MXene nanosheets with the number of stacked layers by Monte Carlo simulations. Insets are the schematic diagrams of non-overlapping pores and overlapping pores. g Probability of pore overlapping of adjacent two-layer porous MXene nanosheets with different pore sizes and pore densities.

The diffusion of hydrogen through the MXene nanosheet membranes can be probed by monitoring the decay of the Raman fingerprint signal of vanadium oxide (VOx). Hydrogen gas can partially reduce VOx and introduce lattice distortion, potentially affecting the Raman-active vibration. VOx thus serves as an indicator of the presence of H2. If H2 is permeated through the membrane, it reacts with VOx, leading to a decay in the V = O vibration at 197 cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. 27)47,48,49. A structure-property relationship can be derived from the time-resolved H2-profile and the O3 treatment, thus providing insights into the transport pathway. It is found that the peak area of the Raman fingerprint at 197 cm−1 decays gradually with increasing pore size of the MXene nanosheets (Supplementary Fig. 28). The faster decay rate directly implies more efficient H2 transport through the membrane. When H2 passes through the nonporous-MXene and porous-MXene-O3-30s nanosheet membranes, no significant decay in the 197 cm−1 peak is observed, as shown by the light blue region in the Raman maps (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 29a). This indicates that gas transport in the perpendicular direction across nonporous MXene nanosheets is negligible, highlighting that interlayer diffusion alone or diffusion through low-density pores are insufficient for observable transport under these conditions. However, as the O3 treatment is extended to 60 s and 180 s, the Raman fingerprints at 197 cm−1 decay significantly, also shown by a light-to-dark blue conversion in the signals mapping (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 29b). This spatial mapping demonstrates that the pore above a diameter of 8 nm allows the penetration of H2 and induces the decay of Raman fingerprints at 197 cm−1 as shown in the dark blue zones. With increasing pore size, the decay of the Raman fingerprint becomes even more pronounced, where the ratio of A0/A (Raman peak area ratio of 197 cm−1 before (A0) and after (A) H2 permeation through the MXene nanosheet membranes) increases gradually (Fig. 3d), which is consistent with the increasing H2 permeance (Fig. 3a). Therefore, the decay of the Raman fingerprints of the VOx indicator confirms the perpendicular H2 transport pathway through the in-plane nanopores, which suggest the H2 passes through the pores, that facilitate direct and efficient transport of the gas molecules across the membrane, ultimately leading to an enhancement in H2 permeance.

The trend of increased H2 permeance and only slightly decreased H2/CO2 selectivity with enlarged in-plane pore size (Fig. 3a) is attributed to the evolution of the stacking structure of the porous MXene nanosheets in the membrane. Molecular gas transport pathways through such a membrane assembled from porous nanosheets are governed by the in-plane pore size (d1), the free interlayer spacing (d2) and the overlapping pore size (d1’) between adjacent porous nanosheets. The interplay of these three characteristic dimensions significantly impacts the effective sieving aperture, i.e. the actual mass transfer channels controlling the separation performance of the membranes. Based on the relationship between the kinetic diameters of gas molecules (dgas) and the d1, d2, d1’ values, four distinct cases can be identified (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Note 1). Gas transport in model ii (e.g., nonporous MXene) primarily occurs through tortuous interlayer channels, while model iii (e.g., 2D MOFs/COFs) relies on in-plane pores. In contrast, model iv (e.g., artificially porous MXene) offers in-plane pores and interlayer dual channels, allowing for promising separation performance (Supplementary Note 2). In this work, the H2/CO2 separation through the porous-MXene nanosheet membranes, with in-plane pore sizes exceeding 8 nm and free spacings above 0.37 nm, corresponds to case (iv). To further investigate the precise molecular transport pathways, the probability of pore overlapping between neighboring porous MXene nanosheets was calculated via Monte Carlo simulations. The probabilities of pore overlapping of the first two layers of the porous-MXene-O3-30s and 60 s nanosheets are 7.4% and 78%, respectively. Given that the probability of pore overlapping between adjacent nanosheets is equal, as the number of nanosheet layers increases, the probability of pore overlapping in the stacked membrane follows P (n) = P (2)n−1, where n represents the number of layers with n ≥ 2. The probability of pore overlapping gradually decreases with increasing layers, reaching a near-zero value at the 4th and 20th layers for the porous-MXene-O3-30s and 60 s nanosheets, respectively (Fig. 3f). Given that 500 nm-thick membranes comprise over 350 pieces of MXene nanosheets, significantly exceeding the aforementioned 4 and 20 layers, gas molecules inevitably traverse the interlayer channels. In other words, the mass transport occurs alternately through in-plane pores and interlayer channels (case (iv)), where the relatively small d2 serves as the effective sieving aperture of the membrane, dictating the gas selectivity, while the larger in-plane pores channels provide sufficient space for increased gas permeance. Consequently, the porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membrane combines high H2 permeance due to the wide in-plane pores with high H2/CO2 selectivity (Fig. 3a). In contrast, the porous MXene-O3-180s nanosheets membrane exhibits high probability of pore overlapping, reaching 100% with 500 stacked layers (Fig. 3f), enabling the facile formation of continuous straight pathways through the wide in-plane pores within the stack (inset of Fig. 3f). In this case, the relatively large d1’ becomes the effective sieving pore aperture, leading to a sharp decrease in H2/CO2 selectivity (Fig. 3a).

To further optimize the pore structure of the porous nanosheets for improved separation performance, additional Monte Carlo simulations were performed for different pore sizes (1-30 nm) and pore densities (0.9-6.8×1010 cm-2). The probability of pore overlapping gradually increases with increasing pore size and pore density (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 30). On the one hand, to achieve good membrane selectivity, there should be an upper threshold for the pore structure of the nanosheets, as indicated by the dashed line in Fig. 3g, where the probability of pore overlapping approaches 100%. This threshold indicates that gas molecules are likely to pass through the straight channels, resulting in relatively poor gas selectivity, as exemplified by the porous-MXene-O3-180s nanosheet membrane with an H2/CO2 selectivity of only 29. On the other hand, there should be a lower threshold for pore formation to enhance gas diffusion and permeation. As evidenced above, the probability of pore overlapping between adjacent porous MXene-O3-30s nanosheets is 7.4%, resulting in no significant improvement in the gas permeance of the membrane. Therefore, the lower threshold corresponds to overlapping probabilities of approximately 7.4% or lower. The area between the upper and lower thresholds represents a significant region for pore generation in nanosheets, making it suitable for achieving both high gas permeance and selectivity. For instance, the pore parameters of the porous MXene-O3-60s nanosheets fall within the suitable range, enabling the stacked membrane to exhibit both high H2/CO2 selectivity (118) and H2 permeance (1335 GPU). Such results will guide the design of high-performance porous nanosheet membranes.

The porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membrane is selected as optimal for subsequent gas separation tests (Fig. 4). The single-gas permeation through the porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membrane demonstrates a distinct cut-off effect, evidenced by the high H2 permeance (1778 GPU) compared to other gases (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 5). The ideal selectivity of H2 over other gases is significantly higher than the Knudsen selectivity (inset in Fig. 4a). The H2/CO2 ideal selectivity of 142 is higher than the mixed-gas H2/CO2 selectivity of 118 due to competitive adsorption of CO214. The membrane thickness (100 nm-1 μm) increases with prolonged electrophoresis time, leading to enhanced H2/CO2 selectivity but decreased H2 permeance (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 6, Supplementary Fig. 31). By optimizing the electrophoresis time and voltage (Supplementary Fig. 32), the 500-nm-thick membranes prepared with electrophoresis time and voltage of 5 min and 5 V achieve a favorable balance between H2 permeance (1335 GPU) and H2/CO2 selectivity (118), by far exceeding the 2008 upper bound and most other membranes reported in the literature (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table 7). Furthermore, the porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membrane maintains stable H2 permeance and H2/CO2 selectivity during continuous long-term gas separation testing for over 200 h (Fig. 4d), further SEM and XRD results confirm the intact surface structure and unchanged interlayer spacing of the membrane after 200 h-gas separation testing (Supplementary Fig. 33). The separation performance of the membrane remains almost unaffected by the presence of 3 vol% steam, with both the H2 and CO2 permeance and H2/CO2 selectivity being well-maintained (Fig. 4e). The H2 permeance of the porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membrane increases with increasing H2 concentration in the feed gas (Supplementary Fig. 34), owing to the intensified driving force for H2 permeation through the membrane. The nylon-supported porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membrane also exhibits exceptional flexibility and mechanical strength, as the H2/CO2 separation performance remains unchanged after bending the membrane to a curvature of 500 m−1 as the reciprocal of radius of curvature (Supplementary Figs. 35 and 36, Supplementary Table 8). Further investigation into the effect of feed pressure on separation performance reveals that elevated pressure can lead to a gradual decrease in H2/CO2 selectivity and a raised H2 permeance, which is attributed to the presence of non-selective defects28,31. Fortunately, the membrane separation performance can be recovered after reducing the feed pressure to 1 bar (Supplementary Fig. 37). Overcoming this limitation of poor pressure resistance of 2D nanosheet membranes is an ongoing area of research. The development of defect-free (or at least defect-minimized) nanosheet membranes should be pursued50. Critically, the spiral-wound membrane with a length of more than 2 m, the flat membrane with a large area of ~0.2 m2 and the hollow fiber membranes with lengths of ~30 cm, have been successfully fabricated, alongside the successful design of the membrane module for H2/CO2 separation (Fig. 4f). The separation performance of the large-area flat membrane was evaluated at 12 random locations (Fig. 4f), exhibiting an average H2 permeance of ~1504 GPU and an average H2/CO2 selectivity of ~105, which is comparable to that of the small-area membranes (Fig. 4g). This demonstrates the significant scale-up potential of the porous-MXene nanosheet membranes.

a Single-gas permeance through the 500-nm-thick porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membrane as a function of gas kinetic diameter. The inset shows the Knudsen and ideal selectivity of H2 with respect to other gases. b H2/CO2 separation performance of the porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membranes prepared at different electrophoresis time. The error bars in Fig. 4b refer to the standard deviation from measurements of three membranes prepared under same conditions. c H2/CO2 separation performance comparison between the porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membrane and other previously reported membranes. Information on the data points is given in Supplementary Table 7. d Long-term stability test of the porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membrane for H2/CO2 separation. e H2/CO2 separation performance of the porous-MXene-O3-60s nanosheet membrane as a function of time with shifting between dry and wet (containing 3 vol% steam) equimolar mixed feeding gas. f Scale-up potential of the porous-MXene nanosheet membranes. Digital photos of the spiral-wound membrane with a length of more than 2 m, the flat membrane with a large area of ~0.2 m2, the hollow fiber membranes with a length of 30 cm and the corresponding compact membrane module. g H2/CO2 separation performance of 12 locations of the membrane in Fig. 4f.

Discussion

This work addresses a critical gap in 2D membrane design by systematically evaluating the synergistic interplay between in-plane pores and interlayer spacing on the gas separation performance and separation mechanism. Specifically, we have designed porous Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets with artificially tunable in-plane pores (8-20 nm) via a facile and scalable post-synthesis approach of O3 treatment, which are subsequently assembled into stacked membranes with controlled interlayer spacing (0.37-0.42 nm) through electrophoretic deposition, enabling precise balancing and matching over both in-plane pores and interlayer spacing for enhanced separation performance. The optimal porous-MXene-O3 nanosheet membranes exhibit an approximately threefold increase in H2 permeance (1335 GPU) compared to the nonporous-MXene nanosheet membranes (419 GPU), while preserving a high H2/CO2 selectivity of 118. Both theoretical and experimental findings show that the relatively large in-plane pores provide a sufficient mass transfer pathway and enhance H2 permeance, while the significantly low probability of pore overlapping, as confirmed by Monte Carlo simulation, ensures that gas molecules are sieved through the relatively small interlayer spacing, leading to high H2/CO2 selectivity. Additionally, we develop a Raman mapping characterization to visualize the significant contribution of the in-plane pores generated on the MXene nanosheets to H2 permeation. This demonstrates that as the in-plane pore size increases, the Raman signal decays more dramatically, and H2 penetrates faster. The porous-MXene nanosheet membranes also exhibit exceptional stability over 200 h of gas separation and show good prospects for scale-up. This work not only provides valuable insights into enhancing the separation performance of traditional nonporous nanosheet lamellar membranes but also offers detailed theoretical guidance on balancing in-plane pores and interlayer channels. The sophisticated construction of porous-MXene nanosheet membranes should find wide applications in such fields as efficient adsorption, catalysis, or nanofluidic for further sustainable development.

Methods

Synthesis of nonporous and porous MXene nanosheets

The nonporous MXene nanosheets were synthesized by selectively removing Al atoms from Ti3AlC2 via LiF/HCl etching process (Supplementary Methods). The porous Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets with different pore sizes were synthesized via a controlled oxidation strategy. Typically, O3 was produced from pure O2 at a flow rate of 500 mL min−1 using an O3 generator (CH-ZTW10G) with adjustable current intensity (from 0 to 100%). The higher the current intensity, the higher the O3 concentration. In this study, a current intensity of 100% was used. The O3 was then continuously introduced into 30 mL of a 1 mg L−1 MXene nanosheet dispersion via an aerator pipe with a pore size of 30 µm to distribute the O3 evenly, with oxidation times of 30, 60, 180, and 300 s. Subsequently, 3 mL of 5 wt% HF was added to the MXene dispersion for 3 h to remove TiO2. The reacted dispersion was then centrifuged at 11180 × g repeatedly several times until the pH was 6 to obtain the porous MXene nanosheet dispersion.

Preparation of the nonporous- and porous-MXene nanosheet membranes

50 mL nonporous or porous MXene nanosheets dispersion with a concentration of 1 mg mL−1 was added into a home-made electrophoresis setup containing two electrodes (anode: hydrophilic nylon substrate tightly adhered to carbon plate, cathode: carbon plate). Subsequently, a voltage of 5 V was applied between the two electrodes and maintained for different time from 1–10 min to obtain membranes with various thicknesses on the nylon substrate of the anode. The obtained membranes after electrophoresis deposition were dried in a vacuum at room temperature for 24 h.

Gas separation performance measurements

As reported in the previous work14, the gas separation of membranes was evaluated in a home-made Wicke-Kallenbach apparatus. All tested membranes were sealed with O-rings to prevent leakage. For single-gas permeation test, gases with different kinetic diameters and sweep gas (Ar) with a flow rate of 50 mL min−1 were fed at 1 bar to the feed and permeate side of the membrane, respectively. For the mixed-gas separation test, the mixed gases (H2 and CO2) with a ratio of 1:1 (50 mL min−1 for each gas) were passed into the membrane and Ar was also used as sweep gas with a flow rate of 50 mL min−1. All tests were performed at 25 °C and the pressure was maintained at 1 bar on both sides of the membrane. The gas flow rate was controlled by a mass flow controller (MFC) and calibrated by a bubble flow meter. A calibrated gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890 A) was used to detect the concentration of each gas on the permeate side. The gas permeance can be calculated by the following equation:

where Pi (mol m−1 s−1 Pa−1), Ni (mol s−1) and ΔPi (Pa) are the gas permeance, molar permeation rate, and the transmembrane pressure of component i, respectively, and A (m2) is the effective membrane area for testing. In this work, gas permeance can be converted from the GPU (Gas Permeation Unit) to the standard unit, where 1 GPU = 3.35 × 1010 mol m−2 s−1 Pa−1.

In addition, the ideal selectivity (Si/j) of the single gas can be calculated as follows:

The selectivity (αi/j) of the mixed gases was cal/culated as follows:

where xi, xj, yi, and yj are the corresponding volumetric fractions of i or j components on the feed side and the permeate side, respectively.

Characterizations

The morphology of the MXene nanosheets and membranes was characterized using a FESEM (Hitachi SU8100), TEM (Hitachi JEM-2100F), and AC-STEM (ThermoFisher Themis Z microscope). AFM (Bruker Dimension Icon) was used to measure the thickness of MXene nanosheets and the surface morphology of the MXene nanosheet membranes in tapping mode. N2 adsorption measurements analyzer (ASAP 2460) was used to evaluate the BET surface area and pore size distribution. The Raman spectra were collected using confocal Raman spectroscopy with a 532 nm stimulating laser at 5 mW (Invia Qontor, Renishaw Inc.). EDX (Oxford EDS) was used to measure the element distribution of the nanosheets and membranes. The chemical compositions of the nanosheets were analyzed using FT-IR (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and etching XPS (Thermo Scientific ESCALAB Xi + ). The Zeta potential of the nanosheets was tested by Malvern Instruments, UK. The interlayer spacing of the MXene nanosheet membranes was characterized by XRD (Bruker D8 ADVANCE) with Cu Kα radiation from 5° to 60° at the scanning rate of 2 min−1. The mechanical tests of the membranes were performed using an Instron-5565 universal testing machine (USA).

Raman visualization of gas pathway

As an indicator to probe the H2 diffusion, an M1 phase vanadium oxide (VOx) was grown on mica according to a chemical vapor deposition modified from the previous report51. Then, the nonporous and porous MXene nanosheets dispersion was drop-casted on the VOx film to form the 70-nm-thick MXene membrane on the VOx indicator, which had a responsive Raman fingerprint to the H2 gas at 200 °C within 1 h. All the spectra were collected by confocal Raman spectroscopy with a stimulating laser at 532 nm and 5 mW (Invia Qontor, Renishaw Inc). The accumulation time for the spectra was set to 2 s, and the spatial mapping of Raman spectra was set to 1 μm step−1. The analysis of Raman spectra and their mapping was carried out by WiRE 5.5 software (Renishaw Inc.). To track the thickness and location of MXene nanosheet membrane on the VOx indicator, an additional characterization by AFM was collected by Dimension Icon (Bruker Inc.) in a ScanAsyst mode (the AFM tip: PPP-NCHR, 10-130 N m−1, Nanosensor Inc).

Monte Carlo method

Monte Carlo simulations were used to calculate the probability that at least one pore on a nanosheet overlaps with those on another neighboring nanosheet. To simplify the model, the pores on the nanosheets have been idealized as circular shapes, similar simplifications have been previously employed in the literature52,53. Other pore shapes, including square and triangular, were also considered as control experiments in the Supplementary Fig. 38. In a typical Monte Carlo simulation, 2 nanosheets with a size of 209 × 209 nm were constructed. In other words, the x-, and y-range of both nanosheets are all 0–209 nm. Then, a certain number of nanopores with given radii were constructed/drilled randomly one after another according to the experimental pore size distribution and pore density (Supplementary Fig. 9). For instance, 4 pores with diameter of 8 nm were generated for porous MXene-O3-30s, 15 pores with diameter of 10 nm for porous MXene-O3-60s, and 30 pores with diameter of 20 nm for porous MXene-O3-180s. The construction procedure ensures that the pores on the same nanosheet would not overlap with each other. For instance, when a newly generated pore was found to overlap with the existing ones (the least distance between the generated center of the pores is less than 2*their radii), this new pore would be rejected, and another pore would be randomly generated. It was then checked whether at least 2 pores in the two nanosheets overlapped (pores on the same nanosheet would not overlap, as described previously), i.e., if the least distance between the generated centers of the pores on the 2 nanosheets is less than 2*their radii, the counter of overlapping events would increase by 1. The above procedure was repeated 10000 times, and the probability, P (2), was calculated by dividing the number of overlapping events by 10,000. We further consider that, as for n stacking nanosheets with a given pore size and pore density, what is the probability, P (n), that pores at each nanosheet overlap to form a continuous nanochannel? Taking into account that the events of pores overlapping between adjacent layers of nanosheets are independent of each other, we have P (n)= P (2)n-1, where n represents the number of porous nanosheet layers with n ≥ 2.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are available in the paper and its Supplementary Information. Source Data are provided with this paper. The data have also been deposited at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30187897.

References

Castelvecchi, D. The hydrogen revolution. Nature 611, 440–443 (2022).

Du, Z. et al. A review of hydrogen purification technologies for fuel cell vehicles. Catalysts 11, 393 (2021).

Ockwig, N. W. & Nenoff, T. M. Membranes for hydrogen separation. Chem. Rev. 107, 4078–4110 (2007).

Turner, J. A. Sustainable hydrogen production. Science 305, 972–974 (2004).

Wang, W. et al. Recent progress of two-dimensional nanosheet membranes and composite membranes for separation applications. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 15, 793–819 (2021).

Koros, W. J. & Zhang, C. Materials for next-generation molecularly selective synthetic membranes. Nat. Mater. 16, 289–297 (2017).

Zhao, Y.-L., Zhang, X., Li, M.-Z. & Li, J.-R. Non-CO2 greenhouse gas separation using advanced porous materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 2056–2098 (2024).

Shi, X. et al. Selective liquid-phase molecular sieving via thin metal-organic framework membranes with topological defects. Nat. Chem. Eng. 1, 483–493 (2024).

Chen, G. et al. Solid-solvent processing of ultrathin, highly loaded mixed-matrix membrane for gas separation. Science 381, 1350–1356 (2023).

Park, H. B., Kamcev, J., Robeson, L. M., Elimelech, M. & Freeman, B. D. Maximizing the right stuff: The trade-off between membrane permeability and selectivity. Science 356, eaab0530 (2017).

Liu, G., Jin, W. & Xu, N. Two-dimensional-material membranes: a new family of high-performance separation membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 13384–13397 (2016).

Kim, H. W. et al. Selective gas transport through few-layered graphene and graphene oxide membranes. Science 342, 91–95 (2013).

Celebi, K. et al. Ultimate permeation across atomically thin porous graphene. Science 344, 289–292 (2014).

Ding, L. et al. MXene molecular sieving membranes for highly efficient gas separation. Nat. Commun. 9, 155 (2018).

Shen, J. et al. 2D MXene nanofilms with tunable gas transport channels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1801511 (2018).

Luo, M. et al. Tubular MXene/SS membranes for highly efficient H2/CO2 separation. AlChE J. 69, e18105 (2023).

Cao, C. et al. Solvent-mediated structural regulation of MXene membranes for H2 purification. Chem. Eng. Sci. 308, 121407 (2025).

Achari, A., Sahana, S. & Eswaramoorthy, M. High performance MoS2 membranes: effects of thermally driven phase transition on CO2 separation efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 1224–1228 (2016).

Luo, M., Zhao, Y., Wei, Y. & Wang, H. Dual-module integration of large-area tubular 2D MXene membranes for H2 purification. Chem. Eng. Sci. 283, 119392 (2024).

Kang, Y. et al. Functionalized 2D membranes for separations at the 1-nm scale. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 7939–7959 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Layered zeolite for assembly of two-dimensional separation membranes for hydrogen purification. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202304734 (2023).

Dakhchoune, M. et al. Gas-sieving zeolitic membranes fabricated by condensation of precursor nanosheets. Nat. Mater. 20, 362–369 (2021).

Peng, Y. et al. Metal-organic framework nanosheets as building blocks for molecular sieving membranes. Science 346, 1356–1359 (2014).

Song, H. et al. Structure regulation of MOF nanosheet membrane for accurate H2/CO2 separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218472 (2023).

Song, S. et al. Tuning the stacking modes of ultrathin two-dimensional metal-organic framework nanosheet membranes for highly efficient hydrogen separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202312995 (2023).

Fan, H. et al. High-flux vertically aligned 2D covalent organic framework membrane with enhanced hydrogen separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 6872–6877 (2020).

Ying, Y. et al. Ultrathin two-dimensional membranes assembled by ionic covalent organic nanosheets with reduced apertures for gas separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 4472–4480 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. Fast hydrogen purification through graphitic carbon nitride nanosheet membranes. Nat. Commun. 13, 5852 (2022).

Villalobos, L. F. et al. Large-scale synthesis of crystalline g-C3N4 nanosheets and high-temperature H2 sieving from assembled films. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay9851 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Reversed thermo-switchable molecular sieving membranes composed of two-dimensional metal-organic nanosheets for gas separation. Nat. Commun. 8, 14460 (2017).

Wu, W. et al. Accurate stacking engineering of MOF nanosheets as membranes for precise H2 sieving. Nat. Commun. 15, 10730 (2024).

Shen, J. et al. Subnanometer two-dimensional graphene oxide channels for ultrafast gas sieving. ACS Nano 10, 3398–3409 (2016).

Lu, Z., Wu, Y., Ding, L., Wei, Y. & Wang, H. A lamellar MXene (Ti3C2Tx)/PSS composite membrane for fast and selective lithium-ion separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 22265–22269 (2021).

Ding, L. et al. Effective ion sieving with Ti3C2Tx MXene membranes for production of drinking water from seawater. Nat. Sustain. 3, 296–302 (2020).

Guo, R. et al. Thickness-independent capacitive performance of holey Ti3C2Tx film prepared through a mild oxidation strategy. Small 19, 2205947 (2023).

Li, S., Gu, W., Sun, Y., Zou, D. & Jing, W. Perforative pore formation on nanoplates for 2D porous MXene membranes via H2O2 mild etching. Ceram. Int. 47, 29930–29940 (2021).

Hong, S. et al. Porous Ti3C2Tx MXene membranes for highly efficient salinity gradient energy harvesting. ACS Nano 16, 792–800 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Enhanced uranium adsorption performance of porous MXene nanosheets. Sep. Purif. Technol. 335, 126134 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Establishing gas transport highways in MOF-based mixed matrix membranes. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf5087 (2023).

Sang, X. et al. Atomic defects in monolayer titanium carbide (Ti3C2Tx) MXene. ACS Nano 10, 9193–9200 (2016).

Bu, F. et al. Reviving Zn0 dendrites to electroactive Zn2+ by mesoporous MXene with active edge sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 24284–24293 (2023).

Du, T. et al. Effects of ozone and produced hydroxyl radicals on the transformation of graphene oxide in aqueous media. Environ. Sci. Nano 6, 2484–2494 (2019).

Yin, Y. & Alivisatos, A. P. Colloidal nanocrystal synthesis and the organic-inorganic interface. Nature 437, 664–670 (2004).

Deng, J. et al. Fast electrophoretic preparation of large-area two-dimensional titanium carbide membranes for ion sieving. Chem. Eng. J. 408, 127806 (2021).

Zhou, H.-Y., Lin, L.-W., Sui, Z.-Y., Wang, H.-Y. & Han, B.-H. Holey Ti3C2 MXene-derived anode enables boosted kinetics in lithium-ion capacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 12161–12170 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Recycling Ti3C2Tx oxide nanosheets through channel engineering: Implications for high-capacity supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 9579–9587 (2023).

Fan, L. et al. A facile strategy to realize rapid and heavily hydrogen-doped VO2 and study of hydrogen Ion diffusion behavior. J. Phys. Chem. C. 126, 5004–5013 (2022).

Yoon, H. et al. Reversible phase modulation and hydrogen storage in multivalent VO2 epitaxial thin films. Nat. Mater. 15, 1113–1119 (2016).

Lin, J. et al. Hydrogen diffusion and stabilization in single-crystal VO2 micro/nanobeams by direct atomic hydrogenation. Nano Lett. 14, 5445–5451 (2014).

Liu, Q. et al. Unit-cell-thick zeolitic imidazolate framework films for membrane application. Nat. Mater. 22, 1387–1393 (2023).

Shi, R. et al. Phase management in single-crystalline vanadium dioxide beams. Nat. Commun. 12, 4214 (2021).

Feng, J. et al. Single-layer MoS2 nanopores as nanopower generators. Nature 536, 197–200 (2016).

Boutilier, M. S. et al. Implications of permeation through intrinsic defects in graphene on the design of defect-tolerant membranes for gas separation. ACS Nano 8, 841–849 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Y.Y.W. acknowledges the funding from the National Key Research and Development Program (2021YFB3802500), Natural Science Foundation of China (U23A20115, 22078107, 22022805), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2024A1515012724), Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Project (2024A04J6251), State Key Laboratory of Pulp and Paper Engineering 2024ZD03, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2025ZYGXZR023). L.L. acknowledges the funding from the Science and Technology Key Project of Guangdong Province (2025B0101060003) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2024A1515012725). L.D. acknowledges the funding from the National Key Research and Development Program (2023YFB3810700) and Natural Science Foundation of China (22422809).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.F.W. performed the experiments. Y.F.W., Y.Y.W., and H.W. conceptualized and designed this work. Z.S. and L.L. performed the Monte Carlo simulations. M.L., Z.L., W.W., and Y.Z. helped perform nanosheet and membrane preparation, and separation performance evaluation. S.L. and J.L. helped perform the preparation and photographing of large-area membranes. S.D., C.J., and W.L. performed the AC-STEM characterizations and analysis. K.Z., Y.Z., and L.L. performed the Raman mapping characterizations and analysis. L.D. helped revise the diagrams. Y.F.W., Y.Y.W., and H.W. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xiuxia Meng, Dan Zhao and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Shi, Z., Luo, M. et al. Balancing in-plane pores and interlayer channels of porous MXene nanosheet membranes for scalable hydrogen purification. Nat Commun 16, 10005 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64942-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64942-6