Abstract

Genetically encoded indicators that can detect concentrations of metabolites and signalling molecules through fluorescence lifetime changes are gaining attention, because they expand the potential for quantitative imaging. These indicators offer advantages over conventional fluorescence intensity-based indicators by minimizing artifacts such as variations in indicator concentration, cellular morphological changes, and focus drift. However, the availability of fluorescence lifetime-based genetically encoded indicators remains limited, particularly those compatible with the widely used conventional 488 nm laser in microscopy. Here, we introduce qMaLioffG, a single green fluorescent protein-based ATP indicator that exhibits a substantial fluorescence lifetime shift (1.1 ns) within physiologically relevant ATP concentrations. This enables quantitative imaging of ATP levels in the cytoplasm and mitochondria under steady-state conditions across various cell types, providing insights into ATP distribution. We demonstrate that qMaLioffG can be used in multicellular systems, applying it to Drosophila brain and HeLa cell spheroids to reveal spatially heterogeneous ATP levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is an energy currency that drives metabolism and regulates extracellular signaling. It also behaves as a hydrotrope that enhances the solubility of intracellular proteins1. Fluorescence imaging has been indispensable for unraveling biological processes involving ATP. To date, various fluorescent ATP indicators have been developed, including Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)2, dual-emission ratiometric3,4 and single fluorescent protein (FP)-based indicators5. More recently, an indicator with submicromolar affinity has also been reported for the detection of extracellular ATP6,7. Despite their extensive availability, intensity-based analyses encounter common difficulties related to indicator concentration, excitation light amplitude, photobleaching, and focus drift, which often hamper quantitative analysis. Even if one attempts to cancel these artifacts using the ratiometric indicators, where intensities at two different channels are measured, it remains challenging to reproduce consistent ratio values and indicator performance between different researchers due to variations in microscopy settings8. Unlike the intensity-based approach, fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM)-based analyses offer the potential for quantitative analysis9. For instance, FLIM is well-suited for FRET-based indicators as the fluorescence lifetime of the donor is altered during the energy transfer process (FRET-FLIM)10. Yet a FRET indicator consists of two FPs, introducing uncertainties in quantitative analysis due to different maturation states of the chromophores between the two proteins11. In addition, FRET-FLIM occupies two color channels, restricting the possibility of multiplex imaging. By contrast, a single FP-based FLIM indicator can potentially circumvent this issue. Several indicators using a single FP, such as mTurquoise or T-Sapphire, have recently emerged for detecting calcium8, glucose12 and lactate13, as well as a specific red-colored FP-based Ca2+ indicator, R-CaMP1h with capability for FLIM imaging14. Nevertheless, the availability of FLIM-based indicators compatible with a conventional 488 nm laser remains scarce, with the exception of the H2O2 and Ca2+ indicators15,16. Herein, we present a single FP-based indicator that is compatible with FLIM, and we demonstrate its applications in the imaging of ATP in the cytoplasm and mitochondria of various cell types, including three-dimensional multicellular spheroidal HeLa cells and Drosophila brain.

Results

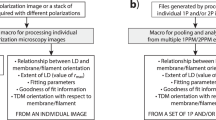

We previously described MaLionG, an intensiometric ATP indicator based on single yellow FP Citrine5. This was identified by the generation of genetic variants in which an ε subunit of an ATP-binding domain of a bacterial FoF1-ATP synthase was inserted into a variant of Citrine via optimized peptide linkers (Fig. 1a). We inserted an ATP-binding domain at different positions within Citrine, generating two scaffolds (Scaffolds I and II) (Fig. 1b). Subsequently, short peptide linkers were incorporated at the C-terminus to enhance structural diversity. For the linkers, we chose segments of the NZ leucine zipper, known for its strong α-helical structure, enabling efficient transmission of ATP-induced conformational changes to the framework of Citrine, thereby altering the molecular environment surrounding the chromophore. The resulting variants were then screened for changes in fluorescence intensity (ΔF/F0) and fluorescence lifetime (Δτ) in the presence and absence of ATP. Primary screening identified a mutant from Scaffold II that exhibited an increase in fluorescence, leading to the development of a preferable turn-on type intensity-based indicator. The variant from Scaffold II was further optimized through intensity-based screening, resulting in the generation of MaLionG with the turn-on property, previously (ΔF/F0 = 390%)5. Other variants with relatively large Δτ values were also found in Scaffold I. These were subjected to fluorescence lifetime-based screening through site-directed saturation mutagenesis to verify the linker at the N-terminus. We ultimately identified the variant showing the turn-off intensity property as well as 1.25 ns (1.1 ns using purified protein) change under 10 mM ATP using cell lysate, which was designated quantitative monitoring ATP level fluorescence lifetime-based turn-off green (qMaLioffG) (λex/λem = 512/525) (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Figs. 1, 2). The lifetime changes (Δτ) of genetic variants identified through screening were also plotted against the intensity change (ΔF/F0), with results suggesting that there was little correlation between the two (Fig. 1d). Although MaLionG showed a greater fluorescence increase upon ATP binding, the lifetime change was only 0.17 ns (Fig. 2a, b). Notably, the dynamic range (Δτ = 1.1 ns using purified protein) of qMaLioffG exceeded that of conventional FRET-FLIM indicators, which typically range from 0.1 to 0.6 ns17,18, with a few exceptions, such as FRET-based cAMP and pH indicators at above 1.0 ns19,20. Regarding the sensing mechanism, in contrast to MaLionG, qMaLioffG is unlikely to follow the exchange mechanism between the protonated and deprotonated states (Fig. 2c) (discussed later). Similar to previous MaLion indicators, qMaLioffG also exhibited specificity for ATP, as well as a comparable kinetic constant for ATP binding (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 3). The influence of pH fluctuation on fluorescence lifetime was also observed to be less significant than its effect on fluorescence intensity (Fig. 2e, f and Supplementary Table 1). In addition, we tested the dose dependence of ATP concentration at room temperature (RT) and 37 °C, where apparent Kd values were estimated to be 2.0 mM and 11.4 mM, respectively (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Table 1). The dynamic range of qMaLioffG at 37 °C was reduced to just half of that at RT.

a Schematic representation of qMaLioffG, illustrated using AlphaFold2. b Optimization of the linkers between Citrine and Bacillus Subtilis ε. The B. Subtilis ε domain for ATP binding was inserted at the different positions within Citrine, respectively (I or II). For each scaffold, short linkers (EF, AEF, ALEF, or ALKEF) were introduced at the C-terminus. Changes in fluorescence intensity (ΔF/F0) and lifetime (Δτ) of mutants, with and without ATP, were summarized in the table. Promising mutants were then subjected to further screening through the site-directed mutagenesis of the N-terminus linker (X). c Final screening results of fluorescence lifetime, with the top variant named qMaLioffG. d Correlation between ΔF/F0 and fluorescence lifetime (Δτ). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

a Fluorescence spectra, b fluorescence lifetime, and c absorption spectra of purified qMaLioffG and MaLionG under buffer conditions. The dotted lines represent the absence of ATP, while the solid lines represent the presence of 10 mM ATP. In (b), fluorescence lifetime values of MaLionG (τ = 1.39 ns and 1.56 ns) and qMaLioffG (τ = 2.57 ns and 1.49 ns) are shown without and with ATP, respectively. d Specificity of qMaLioffG to the other nucleotides. Δτ represents the dynamic range obtained from the comparison with the presence and absence of nucleotides. pH sensitivity of qMaLioffG in the fluorescence intensity (e) and lifetime (f). g Calibration curves in the buffer solution at room temperature (RT) and 37 °C. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates) for (d–g). Fitting curve for RT: y = 2.56 + (1.44−2.56) (x1.82/(2.021.82 + x1.82)), and 37 °C: y = 2.30 + (1.44−2.30)(x1.40/(11.421.40 + x1.40)), where x is ATP (mM) and y is fluorescence lifetime (ns). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Subsequently, we evaluated the performance of qMaLioffG in HeLa cells. Prior to FLIM imaging studies, we assessed the photostability of qMaLioffG in terms of fluorescence lifetime and intensity (Supplementary Fig. 4). Under the conditions used for subsequent time-lapse experiments for 1 h with optimized laser power, fluorescence lifetime alterations due to bleaching or phototoxicity were minimal. Based on these conditions, we proceeded with the validation of qMaLioffG by monitoring intracellular ATP depletion. When qMaLioffG was expressed in HeLa cells, treatment with sodium fluoride (NaF), an enolase inhibitor, during observation resulted in increased fluorescence intensity and lifetime, indicating ATP depletion (Fig. 3a–c, Supplementary Figs. 5–7). Since some FPs are likely to respond to halide ions, we examined this effect in this validation experiment and observed that the halide anion rarely altered the fluorescence lifetime of qMaLioffG (Supplementary Fig. 8)21. We also validated the mitochondrial target qMaLioffG for monitoring mitochondrial ATP (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10). We observed that the ATP concentration in mitochondria was lower than the basal level in the cytoplasm. Upon the addition of NaF and oligomycin, inhibitors for glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) respectively, ATP levels in both compartments approach a nearly identical level (Fig. 3e). To quantify intracellular ATP concentration, a calibration curve of the fluorescence lifetime against the ATP concentration was prepared in membrane-permeabilized cells at RT, exhibiting slight differences compared to that in solution (Fig. 3f).

a Montage of HeLa cells expressing qMaLioffG under NaF inhibition (10 mM) and b its time-course analysis of fluorescence lifetime at different cells. Scale bar: 50 μm. c The comparison before and 30 min after NaF treatment (n = 15, three independent dishes, two-tailed paired Student’s t-test). ****p < 0.0001. The exact p value is 3.2787 × 10−18. d FLIM images of mitochondrial ATP before and after the treatment with oligomycin (25 μM) and NaF (100 mM). Scale bar: 50 μm. e ATP depletion in the cytoplasm and mitochondria with oligomycin and NaF (n = 24–39 cells, three independent dishes, Tukey’s multiple comparisons with adjustment). The middle bar represents the average. ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001. The exact p values are 0.0002 for mitochondria (NaF+Oligomycin) vs. cytoplasm (NaF+Oligomycin) and <0.0001 for others. f Calibration curves comparing membrane-permeabilized HeLa cells and in vitro test tube conditions at RT (test tube data identical to Fig. 2g). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 15–21 cells, three independent dishes). Fitting curve for in cell: y = 2.50 + (1.26−2.50) (x1.60/(2.011.60 + x1.60)). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

We examined whether qMaLioffG was able to differentiate between the ATP levels in different cells with distinct activities in energy metabolism. First, qMaLioffG was applied to skin fibroblasts derived from patients with mitochondrial dysfunction. Fibroblasts obtained by skin biopsy from a patient with a mutation in dynamin-1-like protein (DNM1L) were used22. Quantitative imaging of ATP indicated that mitochondrial ATP levels were significantly lower in the diseased cells than in the normal human dermal fibroblasts (Fig. 4a, b). Correct mitochondrial fission and fusion, in which DNM1L plays a key role, are essential for maintaining mitochondrial function. Since impaired fission and fusion are known to cause ATP depletion, the observed decrease in mitochondrial ATP levels would be consistent with previous studies23. On the other hand, diseased cells exhibited higher cytoplasmic ATP levels than normal cells. This might reflect differences in energy metabolism between them, including possible alterations in glycolysis24. Another possibility is that mitochondrial dysfunction might also impact other processes, such as the ATP/ADP exchanger, thereby altering the balance between ATP and ADP in the cytoplasm. For a clearer understanding, further investigation using additional energy flux analyzers and genetic analyses will be necessary in the future.

a, b Quantitative imaging of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial ATP level in human dermal fibroblasts and the cells derived from a human patient with DNM1L mutation (n = 26–27 cells, three independent dishes, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. The exact p values are 0.0153 for cytoplasm and 0.0005 for mitochondria. Scale bars: 10 μm. c, d Quantitative imaging of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial ATP in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) with or without leukemia inhibitory factor (2iLIF) (n = 57–65 cells, three independent dishes, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test). Scale bars: 20 μm. ****p < 0.0001. NS (not significant). The exact p values are 3.9145 × 10−11 for cytoplasm and 0.1130 for mitochondria. e–g Analysis of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial ATP in cells from intestinal tumor-derived organoids (AKTP). Cell lines such as SC3, SC24, SC6, and SC4 were obtained via subcloning from AKTP, which were classified into two groups with high and low metastasis ability (n = 84–91 cells, three independent dishes, Tukey’s multiple comparisons with adjustment). ****p < 0.0001, **p < 0.01, NS (not significant). The exact p values for mitochondria are 0.6190 (SC3 vs. AKTP), 0.6494 (SC24 vs. AKTP), 1.0000 (SC24 vs. SC3), 0.1354 (SC6 vs. AKTP), 0.8884 (SC6 vs. SC3), 0.8691 (SC6 vs. SC24), 0.5569 (SC4 vs. AKTP), 1.0000 (SC4 vs. SC3), 0.9999 (SC4 vs. SC24) and 0.9265 (SC4 vs. SC6). The exact p values for cytoplasm are 0.9925 (SC3 vs. AKTP), 0.5416 (SC24 vs. AKTP), 0.8153 (SC24 vs. SC3), 0.0018 (SC6 vs. AKTP), 0.0093 (SC6 vs. SC3), 0.1588 (SC6 vs. SC24), 1.6730 × 10−6 (SC4 vs. AKTP), 1.6733 × 10−5 (SC4 vs. SC3), 0.0013 (SC4 vs. SC24) and 0.5140 (SC4 vs. SC6). Scale bars: 20 μm. The middle bars represent the average in the dot-plots graph in Fig. 4. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

We also investigated cytoplasmic and mitochondrial ATP in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs). mESCs can maintain a naïve state in culture by adding 2i (MEK and GSK3 inhibitors) and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF)25. After the removal of 2i and LIF (hereafter 2iLIF), the expression of Nanog, an essential factor for sustaining the naïve state26, was entirely lost, whereas slight expression of Oct3/4 was observed, which served as a pluripotency marker (Supplementary Fig. 11). Subsequent quantitative ATP analysis of mESCs showed that cytoplasmic ATP levels were higher in the presence of 2iLIF than in its absence, whereas no significant difference was observed in mitochondrial ATP levels (Fig. 4c, d). According to previous studies, pluripotency is maintained in the presence of 2iLIF through a combination of glycolysis and OXPHOS; these cells are referred to as naïve pluripotent stem cells27. Conversely, in the absence of 2iLIF, ATP production relies solely on glycolysis, without the assistance of OXPHOS. Interestingly, previous studies also reported that glycolytic activity in embryonic stem cells was not enhanced as a compensatory response to reduced OXPHOS activity28. This hypothesis is consistent with the observed decrease in cytoplasmic ATP levels upon 2iLIF removal, likely driven by sustained glycolysis coupled with reduced OXPHOS (Fig. 4c, d). One might wonder why mitochondrial ATP levels showed little difference despite potential variations in mitochondrial activity with and without 2iLIF. Under normal conditions, mitochondrial ATP concentration remains relatively low due to the rapid efflux of ATP in exchange for ADP via the ATP/ADP exchanger2. We assumed that mitochondrial ATP concentration does not necessarily reflect the rate of ATP synthesis. Therefore, the evaluation of mitochondrial activity, including ATP-producing capacity, remains challenging.

In another series of experiments, we examined ATP levels in cancer cells with varying metastatic abilities. Previously, Morita et al. subcloned organoids derived from intestinal metastatic tumors carrying driver mutations, such as ApcΔ716, KrasG12D, Tgfbr2−/− and Trp53R270H (AKTP). They then transplanted a single subcloned cell line into mice to investigate the occurrence of liver metastasis29,30. The subclones were categorized into two populations based on high (lines SC3 and SC24) or low (SC4 and SC6) metastatic abilities (Fig. 4e). We observed that cytoplasmic ATP levels were significantly higher in high metastatic cell lines than in the low metastatic cell lines (Fig. 4f, g). No significant differences were observed in mitochondrial ATP levels (Fig. 4g). Further genetic analysis of these cell lines demonstrated the loss of stemness markers in cell lines with low metastatic ability, whereas the genetic background identified by AKTP remained unaltered30. The elevated ATP levels observed in metastatic cell lines appear to correspond well with the increased cytoplasmic ATP levels as seen in mESCs that maintain stemness under 2iLIF conditions (Fig. 4d).

To further evaluate qMaLioffG in multicellular systems, it was applied to the Drosophila brain. FLIM images of the brain expressing qMaLioffG revealed that the ATP concentration was highest in Kenyon cells of the mushroom body, followed by other neurons (P neurons, including pSP and pIP neurons), and lowest in the optic lobes (Fig. 5a, b). In addition to differences across distinct brain regions, we also observed heterogeneity within the same region. Although ATP levels differ among cells and regions, treatment with inhibitors of glycolysis and OXPHOS significantly reduced this variance, depleting ATP levels to near-empty levels (Fig. 5b). Distinct regions of the brain play pivotal roles in functions such as recognition, learning and memory, and how energy is managed for these various activities remains an open question31. While ATP heterogeneity is plausible in principle due to region-specific energy demands and supply, sample degradation cannot be ruled out and is indeed likely, considering the extremely low ATP levels observed. These findings also suggest that ATP measurements may provide a more sensitive indicator of sample quality compared to conventional viability assays such as PI staining. Although brain samples were minimally damaged during preparation, as supported by previous literature and cell viability tests (Supplementary Fig. 12), it should be taken into account that the neural network may not remain fully intact. Further investigation is required for a deeper understanding of energy metabolism or other activities32. In the future, this cellular heterogeneity could be addressed through in vivo imaging under more intact conditions by integrating other technologies that identify cell types based on genetic information.

a Bright fields (BF) and FLIM images of Drosophila brain in the absence and presence of NaF (100 mM) and oligomycin (25 µM). b Quantification of ATP level in the mushroom body (Kenyon cells), P neurons, and optic lobe (n = 32–48, Tukey’s multiple comparisons with adjustment). ****p < 0.0001, NS. The exact p values are 0.9806 (stimulated P vs. stimulated MB), 5.8835 × 10−8 (basal OL vs. stimulated MB), 1.0708 × 10−6 (basal OL vs. stimulated P), 0.9455 (stimulated OL vs. stimulated MB), 0.9998 (stimulated OL vs. stimulated P), 3.5473 × 10−5 (stimulated OL vs. basal OL), and <0.0001 for others. Scale bar: 50 μm. c–e Quantification of changes in ATP level under treatment of 2DG in 3D spheroid and 2D HeLa cells stably expressing qMaLioffG. c Schematic illustration of the imaging with definition of region of interests (ROIs) in 3D spheroid. Created in BioRender. Vu, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/zw7vrp6. d FLIM images of 3D spheroid in different Z positions and 2D HeLa cells under the treatment of 2DG. e Fluorescence lifetime of different ROIs in different Z positions at the basal condition and under the treatment of 2DG (20 mM) for 90 min. Data shows mean ± SD. Scale bar, 50 μm. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Finally, we imaged 3D spheroidal HeLa cells stably expressing qMaLioffG. Cultured spheroids are used for drug screening because their denser multicellular structure is closer to that of tissues. Remarkably, we observed lower cytoplasmic ATP levels within the spheroids than in their surroundings (Fig. 5c, d). The lower internal ATP level observed was likely due to the limited nutrient diffusion to the center of the spheroid. Subsequently, the spheroids were exposed to 2-deoxyglucose (2DG), a glycolytic inhibitor. Over time, the concentration gradient of cytoplasmic ATP gradually disappeared, although heterogeneous ATP levels persisted in comparison with the 2D cells (Fig. 5e). With more critical treatment using NaF as a strong glycolytic inhibitor, the gradient completely disappeared, suggesting that the concentration gradient in spheroidal cells observed in Fig. 5d is unlikely to be an artifact, due to e.g., light scattering, light penetration issues, and bleaching (Supplementary Fig. 13).

With a renewed focus on the above results, we sought to quantify ATP concentration across different cells using the in-cell calibration curve. As shown in Fig. 3f, the fluorescence lifetime in the cytoplasm of permeable-HeLa cells in the absence of ATP (0 mM) in the medium was nearly identical to that of HeLa cells in a depleted state after treatment with inhibitors for glycolysis and OXPHOS (Fig. 3e, f). Likewise, we examined the depletion of mitochondria as a distinct compartmentalized space. The ATP depletion level in mitochondria showed a slight difference compared to the cytoplasm (Fig. 3e). This might be attributed to the complexity of the compartmentalized space, preventing complete ATP depletion. Yet, considering the detection limit of 0.25 mM (approximately 2.45 ns) based on in-cell calibration curves, this slight variation could not be discussed in the detail and can be thought as negligible (Fig. 3e). To assess the applicability of the calibration curve obtained from HeLa cells, we also examined the ATP-depleted states in cytoplasm of different cell types such as fibroblasts and Drosophila brain. We found that the depletion levels were nearly identical across species, consistent with the starting point in the in-cell calibration curve (Supplementary Fig. 14). For reference, the fluorescence lifetime data obtained through this study were converted to ATP concentration using an in-cell calibration curve (Supplementary Table 2). Consequently, the evaluated ATP concentration range was in good agreement with previously reported millimolar concentrations in the literature33,34. For instance, intracellular ATP concentration across various cell types has been quantified using other techniques that require cell lysis followed by HPLC analysis or luciferase-based assays with substrates in chemical reactions, reporting values ranging from approximately 0.5 to 10 mM35. In contrast, fluorescence-based indicators, such as the intensity-based ratiometric indicator (Queen 37) and the bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET)-type ATP indicator, estimated cytoplasmic ATP concentration in HeLa cells to be 3.9 ± 1.1 mM and 3.8 ± 0.1 mM at 37 °C, respectively33,36. The latter BRET indicator also measured mitochondrial ATP levels at 2.5 ± 0.1 mM, which was lower than the cytoplasmic ATP level. Although ATP concentration data varied depending on the different modality, our results (Supplementary Table 2, HeLa: cytoplasm, 4.6 ± 1.1 mM, mitochondria, 1.9 ± 0.4 mM) were likely consistent with previous studies and fell within the same millimolar range. Since the ATP level in Drosophila brain was out of range and could not be quantified, the apparent Kd value should be optimized in the future to extend the detection range beyond 10 mM. In addition, the observed data variation, as shown in Fig. 4g, may be due to the detection ability approaching its limit at higher ATP concentrations. Expanding this limit could also enable more accurate measurements in cells with relatively higher ATP levels, such as metastatic cancer cell lines. Conversely, for extracellular ATP, the Kd value should be adjusted to the micromolar range. Additionally, because so many cells show a limited tolerance of temperature variation, it would be interesting to develop an indicator that functions effectively at physiologically relevant 37 °C with a higher dynamic range6.

Discussion

In this study, we generated a single Citrine-based FLIM indicator for detecting ATP. Despite using a yellow FP in a variant, qMaLioffG is compatible with microscopic settings for green FP, allowing excitation with a common 488 nm laser (hence, named qMaLioffG). In addition, Citrine-based indicators are superior to cyanine-colored ones that require a 435 nm laser, as they are excited by longer-wavelength lasers, resulting in lower phototoxicity and reduced autofluorescence background. Since several ATP indicators have been developed to date, we examined their fluorescence lifetime response (Supplementary Fig. 15 and Supplementary Table 3). For instance, ATeam1.03, a pioneering ATP biosensor, employs a FRET-based sensing mechanism, resulting in a fluorescence lifetime change (Δτ = 0.3 ns) within the typical dynamic range of FRET-FLIM biosensors. In contrast, other green FP-based ATP indicators, such as GRABATP, iATPSnFR1.0, and iATPSnFR1.1, exhibit hardly any fluorescence lifetime change upon ATP binding (Δτ = 0.01–0.05 ns). Regarding qMaLioffG, the exact sensing mechanism of the indicator underlying the alteration of fluorescence lifetime remains unclear. To address the mechanism, we investigated the radiative rate constant (kr) and the non-radiative rate constant (knr) after ATP binding. We observed a significant change in the non-radiative rate constant (knr) of qMaLioffG after ATP binding, while the change in the radiative rate constant (kr) was minimal. This led to an alteration in fluorescence lifetime upon ATP binding, as it is inversely proportional to the sum of kr and knr (Supplementary Table 1)9,37. For a deeper understanding of excited-state dynamics, we also investigated the kinetics using femtosecond transient spectroscopy. In both MaLionG with ATP and qMaLioffG without ATP, where fluorescence emission was dominant, stimulated emission with red shift was observed, as indicated by the asterisk in Fig. 6. The observation of stimulated emission suggests a more extensive distribution of emissive states in the excited state. Furthermore, no significant differences were observed in the transient absorption spectra after 1 ps. This suggested that in both MaLionG and qMaLioffG, the excited-state energy relaxes along the excited-state potential energy surface before emitting fluorescence and that equilibration between the emissive and non-emissive excited states occurs within 1 ps. In contrast, time-course analysis of the transient absorption profiles exhibited significant differences between the two indicators within 100 fs (Supplementary Fig. 16). The transient absorbance time profiles of MaLionG showed a fast relaxation toward the emissive side of the potential surface, indicating that the activation energy between the emissive and non-emissive states is relatively small (Fig. 6a). Consequently, the excited energy is predominantly relaxed through the emissive state, regardless of ATP binding, which is consistent with the small lifetime change (Δτ) of MaLionG. The increase in the population of the emissive state in the ground state upon ATP binding was a major factor contributing to the enhancement of fluorescence in MaLionG. On the other hand, the time-course analysis of qMaLioffG exhibited distinct equilibrium behavior in the presence and absence of ATP. The disappearance of stimulated emission within 1 ps upon binding of ATP suggests a shorter equilibrium time and a lower activation energy barrier between its emissive and non-emissive states in the excited state with ATP binding (Fig. 6b). As a result, the excited state relaxed through both emissive and non-emissive pathways, leading to a greater change in fluorescence lifetime due to an increased population of non-radiative relaxation states upon ATP binding. From a structural perspective, we assumed that ATP binding might increase the free volume and rotational freedom of the tyrosine-based chromophore in qMaLioffG. The free volume increment also leads to a reduced curvature of the potential energy surface. As a consequence, while the deprotonated state of the chromophore is maintained to some extent, the energy from the excited state would be dissipated via a non-radiative process due to the acceleration of chromophore motion.

Schematic illustrations of the ground and excited states of MaLionG (a) and qMaLioffG (b). The solid line represents the state without ATP, while the dotted line represents the state with ATP. Transient absorption spectra (right) were measured using femtosecond transient spectroscopy in the absence and presence of ATP (10 mM). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

One of the key advantages of single FP-based indicators is their ability to facilitate multiplex imaging. By incorporating the FLIM strategy, this approach adds a missing piece for quantitative and reproducible analysis, enabling the simultaneous quantification of multiple elements within the same cell when coupled with other color FP-based FLIM indicators. Furthermore, since FLIM analysis does not require normalization, two-photon FLIM holds great potential for advancing research on the in vivo dynamics of metabolites and signaling molecules in animal studies. This presents a promising perspective for the application of single FP-based FLIM indicators.

Methods

Ethical statement

All genetic recombination experiments were approved by the Biosafety Committee in Kanazawa University and the Institute of Science, Tokyo. The use of fibroblasts with a DNM1L mutation, derived from skin biopsy samples, was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Defense Medical College (approval number 4845) and Kanazawa University (82709-1). Since the patient involved in this study was a child, the research details were explained to the parents, and a signed informed consent was obtained. All the experimental work contributing to this study that was undertaken using A*STAR resources and on A*STAR premises was carried out in accordance with appropriate local ethical guidelines and with approvals of the local ethical committees, as and where applicable.

Chemicals

To test the specificity, ATP, ADP, AMP and GTP were purchased from Nacalai Tesque and dATP was purchased from Thermo Scientific. For cellular studies, sodium fluoride (NaF) and oligomycin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All oligonucleotides for primers were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Common reagents for cell culture were as follows: Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Nacalai Tesque), GlutaMax (Gibco), fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco), sodium pyruvate (Nacalai Tesque), penicillin-streptomycin (FujiFilm Wako), β-escin (FujiFilm, MP Biomedicals, Inc.) and EGTA (Sigma-Aldrich).

Screening and characterization of qMaLioffG

The screening procedure of qMaLioffG, including protein purification and in vitro spectroscopic characterization, was addressed in supporting information in a previous paper5. As described therein, buffer solutions containing qMaLioffG (10 μM) and different nucleotides (ADP, AMP, GTP, dATP) were prepared and placed onto glass-bottom dishes, and fluorescence lifetime was evaluated using microscopy. Likewise, the pH sensitivity of qMaLioffG was evaluated with varying pH (from 5.0 to 8.5). The in-cell calibration curve between ATP and fluorescence lifetime was prepared as described previously12. Briefly, a buffer solution with K-Gluconate (140 mM), NaCl (10 mM), HEPES (10 mM), EGTA (1 mM), MgCl2 (1.3 mM) and CaCl2 (0.34 mM) was prepared, followed by the addition of β-escin as a cell-permeabilized reagent (adjusted to 50 μM as final concentration). After HeLa cells were treated with the solution for 5 min., it was exposed with the solution without β-escin. With the buffer solutions varying ATP concentration (0–10 mM), fluorescence lifetime was plotted. We performed curve fitting using the modified Hill function with offset (Hill1 mode) in Origin software (OriginPro, Version 2022b, OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). The Hill1 equation is \(y={{\mathrm{START}}}+\left({{\mathrm{END}}}-{{\mathrm{START}}}\right)\frac{{x}^{n}}{{{k}^{n}+x}^{n}}\), where y is fluorescence lifetime, x is ATP concentration, k is dissociation constant and n is the Hill coefficient. Plasmids for biosensors, including GRABATP1.0 (#167582), iATPSnFR1.0 (#102548), and iATPSnFR1.1 (#102549), were obtained from Addgene, while ATeam1.03 plasmid was synthesized by IDT. The plasmid for qMaLioffG was deposited in Addgene under #212825.

Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM)

FLIM imaging was performed using an FV1200 confocal microscope (Olympus) equipped with rapidFLIMHiRes with MultiHarp 150 Time-Correlated Single Photon Counting unit (PicoQuant). An oil immersion objective lens was used throughout all experiments (PLAPON 60X, NA = 1.42, Olympus). For excitation, a 485 nm pulse laser (PicoQuant) was used and fluorescence emission was collected through a bandpass filter (520/35 nm, Bright Line HC). The scanning size was 512 × 512 pixels, and the scanning time was 1.109 s/frame.

Fluorescence quantum yield and lifetime measurement

The fluorescence quantum yield (QY) of purified qMaLioffG protein was measured with the Quantaurus-QY Plus UV-NIR absolute PL quantum yield spectrometer (C13534, Hamamatsu). The excitation wavelength was 480 nm. For fluorescence lifetime measurement, the Quantaurus-Tau Fluorescence lifetime spectrometer (C11367, Hamamatsu) was used. The excitation and emission were set to 470 and 525 nm, respectively. The peak counts were set to 500 and two-component fitting was performed to obtain the averaged τ. The concentration of qMaLioffG was 10 µM, and the measurements were conducted in an ATP-binding buffer (50 mM MOPS, 50 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.05% Triton X-100, pH 7.4) for both fluorescence QY and lifetime measurements.

Cell culture and imaging experiments for HeLa cells, human dermal fibroblasts, cells from the patient with DNM1L, and intestinal tumor-derived cell subclones

HeLa cells purchased from ATCC (CCL-2) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with FBS (10%) and penicillin-streptomycin (1%). Human dermal fibroblasts, as a control, were purchased from CELLnTEC (Bern, Switzerland). Fibroblasts were also established by skin biopsy from the patient (a 6-month-old boy) with DNM1L mutation (a de novo missense mutation of c. 1217T>C, p.Leu406Ser)22. These cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The metastatic intestinal tumor-derived cell subclones were established previously29,30. In brief, metastatic intestinal tumor-derived organoids carrying ApcΔ716, KrasG12D, Tgfbr2−/−, Trp53R270H mutations (AKTP) were developed from intestinal tumors of AKTP mice29. An established AKTP organoid was subjected to subcloning, and the metastatic ability of each subclone was examined by spleen transplantation and in vivo luciferase imaging. Although parental cells maintained high metastatic ability, approximately 30% of subclones showed a loss of metastatic ability. In this study, SC3 and SC24 subclones were used as highly metastatic AKTP tumor cells, while SC6 and SC4 were used as low or non-metastatic cells.

For further FLIM experiments, these cells were seeded on a 3.5 cm glass-based dish, followed by the transfection with 0.2 μg of the plasmid DNA of qMaLioffG (pcDNA3.1(−)) using 0.8 μl of FuGENE HD Transfection Reagent (Promega) in 10 μl of Opti-MEM (Life Technologies Corporation). After the transfection, the dishes were maintained at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for 8 h, washed out with a fresh DMEM with 10% FBS, and then incubated at 30 °C for 48 h before imaging experiments. All imaging experiments in this paper were performed at RT (23 °C).

ES cell culture and immunostaining

A mouse ESC line EB5 (RIKEN Bioresource Center) was cultured under maintenance medium containing high glucose DMEM, GlutaMax, 15% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, penicillin-streptomycin, non-essential amino acid (NEAA; Gibco), 0.1 mM 2-mercapthoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1000 U/mL LIF (Merck/Sigma-Aldrich, ESG1107). Medium was filtrated with 0.22 µm filter unit (Corning). Cells were passaged on 0.1% gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich)-coated plastic dishes (FALCON #353004) every other day. Before transfection of qMaLioffG (pcDNA3.1(−)), 1 × 105 cells were passaged on 3.5 cm glass-bottom dishes (D11130H, Matsunami-Glass, Japan) with thin Matrigel (Corning, 354230) coating. Cells were incubated with maintenance medium with 2i (1 μM PD0325901 (Stemgent, USA, Stemolecule™ 04–0006) and 3 μM CHIR99021 (Stemgent, Stemolecule™ 04-0004)). 24 h after seeding, qMalioffG was transfected into cells by using FuGene HD transfection reagent (Promega). Cells were incubated for 24 h and then used for FLIM observation and fixed for immunostaining. For induction of differentiation, 2i and LIF were simultaneously removed from the maintenance medium during transfection.

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C. After fixation, cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X diluted with PBS for 10 min at RT. Cells were blocked with CAS-BlockTM Histochemical Reagent (Thermofisher Scientific, 008120) for 30 min at RT. Then, cells were incubated with primary antibodies against Nanog (abcam, ab80892) and Oct3/4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-5279) for 1 h at RT. Cells were washed with PBS three times and incubated with secondary antibodies, ab150116 and ab150080 (Abcam). Nuclei were counterstained with 50 mg/ml Hoechst 33258 (Dojinkagaku, Japan). After incubation, cells were washed with PBS and mounted with Fluoro-KEEPER antifade reagent (Nacalai Tesque). Fluorescent images were collected with Zeiss LSM800 with x 40 lens (Plan-APO CHROMAT 40x/1.4 Oil DIC).

Fly experiments

Flies (Drosophila melanogaster) were maintained on standard fly medium, under normal 12-h light/12-h dark conditions at 25 °C. qMaLioffG-fly, a codon-optimized qMaLioffG gene for Drosophila melanogaster (Eurofingenomics, Japan), was inserted into the pJFRC7 (Addgene: Plasmid #26220) vector (Pfeiffer et al., 2010) via the Xho I and Xba I restriction sites. The plasmid was injected into embryos, which have nos-phiC31 (BL# 34771) integrase and VK00005 (BL# 9725) and the UAS-MaLioffG strain was established with standard methods. Through the GAL4/UAS system, MaLioffG was expressed in fruitless-expressing neurons (BL#66696)38. Eclosed male flies were collected and maintained in a group (approximately 10–20 flies per vial) until use. In all experiments, flies 6–7 days after eclosion were used. The plasmid was obtained from Addgene (#26220).

All imaging experiments were performed in an adult hemolymph-like (AHL) saline, containing 108 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 8.2 mM MgCl2, 4 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM trehalose, 10 mM sucrose, 5 mM HEPES39. The brain was dissected in Ca2+-free AHL saline, and the blood-brain barrier was digested with papain (10 U/ml) (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, New Jersey, USA) for 15 min at RT. The brain was transferred into a glass-bottom dish filled with AHL.

Lenti viral infection

For stable expression, a lentivirus was used. Five micrograms of CSII-EF-qMaLioffG, 4 µg of pMDLg/pRRE, 2 µg of pRSV-Rev and 2.5 µg pMD2.G were transfected into HEK293T (seeded with 7 million cells/10 cm dish on a previous day) with 41 µL of Lipofectamine 3000. For the next 2 days after the transfection, the viral supernatant was collected with filtration each day and concentrated with the Lenti-X Concentrator. HeLa cells were infected with the lentivirus with 10 µg/mL polybrene. Then, cells with positive expression were collected by BD FACSAria™ II Cell Sorter (Laser 488 nm, filter 530/30 for qMaLioffG).

2-deoxy-D-glucose (2DG) experiments of 3D spheroid and 2D HeLa cells

We prepared 3D spheroid HeLa cells stably expressing qMaLioffG in an EZSPHERE 96-well plate (4860-900, Iwaki). We cultured HeLa cells with a density of 8 × 104 cells/well in a DMEM (11965092, ThermoFisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (P/S) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 24–48 h to form spheroids. Next, we gently transferred spheroid cells from a 96-well plate to a glass-bottom dish coated with a functional polymer sheet40 and filled with 2 mL DMEM culture medium, and continued cultured for 8–10 h. To remove unattached spheroid cells and dead cells, we washed the spheroid cells three times with PBS solution and finally exchanged the medium to Hanks’ Balanced Salt solution (HBSS (+), 09735-75, Nacalai Tesque Inc.) before the microscopy observation. For 2DG treatment, we freshly prepared 2DG (D0051, TCI) and stimulated 3D spheroid or 2D HeLa cells stably expressing qMaLioffG with 2DG to a final concentration of 20 mM. We performed FLIM imaging with the same setup as mentioned in the FLIM imaging section, otherwise stated.

Femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy

Transient absorption spectra were measured using a home-built apparatus. For transient absorption measurements, a regeneratively amplified femtosecond pulse (Spectra-Physics, Solstice, 795 nm, 1 kHz) was split in two; the second harmonic of one beam at 398 nm was used as the excitation light, and the white light generated with the other beam by introducing it into an optical parametric amplifier (Light Conversion, TOPAS) and focusing the obtained signal light (1.3 mm) into a CaF2 plate was used as the probe light. The generated white light was divided into two parts by a half-mirror; one part was used as the monitoring light and transmitted to the 2 mm glass cell sample with stirring, and the other part was directed to a spectrometer with a s-CMOS camera (spectrometer: SpectraPro HRS-500, Princeton Instruments, s-CMOS camera: ORCA-Quest 2, Hamamatsu Photonics).

Statistics and reproducibility

All data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). No samples were excluded from analysis and all experiments were reproducible. Statistical analysis was performed using KaleidaGraph (version 5), OriginPro (Version 2022b) and Microsoft Excel (Version 16.96.1), as specified in figure legends.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data from this study are available in the main paper and its supplementary information. Source data are provided with this paper. The qMaLioffG plasmid has been deposited in Addgene (https://www.addgene.org/212825/). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Patel, A. et al. ATP as a biological hydrotrope. Science 356, 753–756 (2017).

Imamura, H. et al. Visualization of ATP levels inside single living cells with fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based genetically encoded indicators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 15651–15656 (2009).

Yaginuma, H. et al. Diversity in ATP concentrations in a single bacterial cell population revealed by quantitative single-cell imaging. Sci. Rep. 4, 6522 (2014).

Berg, J., Hung, Y. P. & Yellen, G. A genetically encoded fluorescent reporter of ATP: ADP ratio. Nat. Methods 6, 161–166 (2009).

Arai, S. et al. RGB-color intensiometric indicators to visualize spatiotemporal dynamics of ATP in single cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 10873–10878 (2018).

Wu, Z. et al. A sensitive GRAB sensor for detecting extracellular ATP in vitro and in vivo. Neuron 110, 770–782.e5 (2022).

Lobas, M. A. et al. A genetically encoded single-wavelength sensor for imaging cytosolic and cell surface ATP. Nat. Commun. 10, 711 (2019).

van der Linden, F. H. et al. A turquoise fluorescence lifetime-based biosensor for quantitative imaging of intracellular calcium. Nat. Commun. 12, 7159 (2021).

Berezin, M. Y. & Achilefu, S. Fluorescence lifetime measurements and biological imaging. Chem. Rev. 110, 2641–2684 (2010).

Klarenbeek, J. B., Goedhart, J., Hink, M. A., Gadella, T. W. J. & Jalink, K. A mTurquoise-based cAMP sensor for both FLIM and ratiometric read-out has improved dynamic range. PLoS ONE 6, e19170 (2011).

Murakoshi, H., Lee, S.-J. & Yasuda, R. Highly sensitive and quantitative FRET–FLIM imaging in single dendritic spines using improved non-radiative YFP. Brain Cell Biol. 36, 31–42 (2008).

Díaz-García, C. M. et al. Quantitative in vivo imaging of neuronal glucose concentrations with a genetically encoded fluorescence lifetime sensor. J. Neurosci. Res. 97, 946–960 (2019).

Koveal, D. et al. A high-throughput multiparameter screen for accelerated development and optimization of soluble genetically encoded fluorescent biosensors. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–14 (2022).

Díaz-García, C. M. et al. Neuronal stimulation triggers neuronal glycolysis and not lactate uptake. Cell Metab. 26, 361–374.e4 (2017).

Bilan, D. S. et al. HyPer-3: a genetically encoded H2O2 probe with improved performance for ratiometric and fluorescence lifetime imaging. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 535–542 (2013).

Linden, F. H. et al. A green lifetime biosensor for calcium that remains bright over its full dynamic range. eLife 14, RP105086 (2025).

O’Banion, C. P. & Yasuda, R. Fluorescent sensors for neuronal signaling. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 63, 31–41 (2020).

Vu, C. Q. & Arai, S. Quantitative Imaging of Genetically Encoded Fluorescence Lifetime Biosensors. Biosensors 13, 939 (2023).

Burgstaller, S. et al. PH-Lemon, a fluorescent protein-based pH reporter for acidic compartments. ACS Sens. 4, 883–891 (2019).

Klarenbeek, J., Goedhart, J., Van Batenburg, A., Groenewald, D. & Jalink, K. Fourth-generation Epac-based FRET sensors for cAMP feature exceptional brightness, photostability and dynamic range: characterization of dedicated sensors for FLIM, for ratiometry and with high affinity. PLoS ONE 10, e0122513 (2015).

Wachter, R. M. & Remington, S. J. Sensitivity of the yellow variant of green fluorescent protein to halides and nitrate. Curr. Biol. 9, 628–629 (1999).

Zaha, K. et al. DNM1L-related encephalopathy in infancy with Leigh syndrome-like phenotype and suppression-burst. Clin. Genet. 90, 472–474 (2016).

Ashrafian, H. et al. A mutation in the mitochondrial fission gene Dnm1l leads to cardiomyopathy. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001000 (2010).

Robertson, G. L. et al. DRP1 mutations associated with EMPF1 encephalopathy alter mitochondrial membrane potential and metabolic programs. J. Cell Sci. 136, jcs260370 (2023).

Ying, Q. L. et al. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature 453, 519–523 (2008).

Stuart, H. T. et al. NANOG amplifies STAT3 activation and they synergistically induce the naive pluripotent program. Curr. Biol. 24, 340–346 (2014).

Lisowski, P., Kannan, P., Mlody, B. & Prigione, A. Mitochondria and the dynamic control of stem cell homeostasis. EMBO Rep. 19, e45432 (2018).

Carbognin, E., Betto, R. M., Soriano, M. E., Smith, A. G. & Martello, G. Stat3 promotes mitochondrial transcription and oxidative respiration during maintenance and induction of naive pluripotency. EMBO J. 35, 618–634 (2016).

Sakai, E. et al. Combined mutation of Apc, Kras, and Tgfbr2 effectively drives metastasis of intestinal cancer. Cancer Res. 78, 1334–1346 (2018).

Morita, A., Nakayama, M., Wang, D., Murakami, K. & Oshima, M. Frequent loss of metastatic ability in subclones of Apc, Kras, Tgfbr2, and Trp53 mutant intestinal tumor organoids. Cancer Sci. 114, 1437–1450 (2023).

Baeza-Lehnert, F. et al. Non-canonical control of neuronal energy status by the Na+ pump. Cell Metab. 29, 668–680.e4 (2019).

Ueno, K. et al. Coincident postsynaptic activity gates presynaptic dopamine release to induce plasticity in Drosophila mushroom bodies. eLife 6, e21076 (2017).

Okada, Y. & Yaginuma, H. Live cell imaging of metabolic heterogeneity by quantitative fluorescent ATP indicator protein, Queen-37C. Preprint at bioRxiv https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.10.08 (2021).

Porcelli, A. M. et al. Targeting of reporter molecules to mitochondria to measure calcium, ATP, and pH. Methods Cell Biol. 65, 353–380 (2001).

Traut, T. W. Physiological concentrations of purines and pyrimidines. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 140, 1–22 (1994).

Yoshida, T., Kakizuka, A. & Imamura, H. BTeam, a novel BRET-based biosensor for the accurate quantification of ATP concentration within living cells. Sci. Rep. 6, 39618 (2016).

Martin, M. E., Negri, F. & Olivucci, M. Origin, nature, and fate of the fluorescent state of the green fluorescent protein chromophore at the CASPT2//CASSCF resolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 5452–5464 (2004).

Stockinger, P., Kvitsiani, D., Rotkopf, S., Tirián, L. & Dickson, B. J. Neural circuitry that governs Drosophila male courtship behavior. Cell 121, 795–807 (2005).

Wang, J. W., Wong, A. M., Flores, J., Vosshall, L. B. & Axel, R. Two-photon calcium imaging reveals an odor-evoked map of activity in the fly brain. Cell 112, 271–282 (2003).

Suematsu, Y. et al. Ultra-thin, transparent, porous substrates as 3D culture scaffolds for engineering ASC spheroids for high-magnification imaging. J. Mater. Chem. B 8, 6999–7008 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Taniyuki Furuyama (Kanazawa University) for the kind support in measuring the fluorescence lifetime and quantum yield. This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (JP18H04832 and JP22H05176 to T.K.), a grant from the Nakatani Foundation (to S.A.), JST FOREST Program (JPMJFR201E to S.A. and JPMJFR203Q to T.F.), the Biomedical Research Council, Singapore through core support to the Skin Research Institute of Singapore (SRIS) (H.I., E.B.L.), a Human Frontier Science Program Grant (RGP0047/2018 to E.B.L.) (partial support for H.I.), and the Cooperative Research Program of “Network Joint Research Center for Materials and Devices” (to T.K. and S.A). The authors thank the A*STAR Microscopy Platform (AMP) for the technical support. TS and AMP were funded by Singapore’s Agency for Science, Technology, and Research (A*STAR) through core funds and under the HBMS IAF-PP Project (H1701a0004) and through the National Research Foundation Singapore under its Shared Infrastructure Support grant for SingaScope—a Singapore-wide microscopy infrastructure network (NRF2017_SISFP10). The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the JSPS of Science Overseas Research Fellowships (to H.I.). The authors thank the Bloomington Stock Center for providing fly strains.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A. and T.Kit. conceived and coordinated the project. Data acquisitions: S.A., H.I., C.Q.V. and L.T.N.N. Data analysis: S.A., C.Q.V. and L.T.N.N. M.Osa., Y.T. and S.N. contributed to fibroblast with DNM1L mutation experiments. M.N., M.Osh. and A.M. contributed to AKTP organoids experiments. K.O., S.O., A.T. and S.A. conducted mESCs experiments. T.Kiya., C.Q.V. and S.A. conducted Drosophila experiments. M.T., T.F. and S.R.S. contributed to 3D spheroid cell experiments. A.F. and T.Ka. performed femtosecond transient measurement. S.A. wrote the manuscript with input from T.Kit., I.H. and E.B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Joachim Goedhart and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arai, S., Itoh, H., Vu, C.Q. et al. qMaLioffG: a genetically encoded green fluorescence lifetime-based indicator enabling quantitative imaging of intracellular ATP. Nat Commun 16, 9972 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64946-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64946-2