Abstract

Deep discriminative models provide remarkable insights into hierarchical processing in the brain by predicting neural activity along the visual pathway. However, these models differ from biological systems in their computational and architectural properties. Unlike biological systems, they require teaching signals for supervised learning. Moreover, they rely on feed-forward processing of stimuli, which contrasts with the extensive top-down connections in the ventral pathway. Here, we address both issues by developing a hierarchical deep generative model and show that it predicts an extensive set of experimental results in the primary and secondary visual cortices (V1 and V2). We show that the widely documented sensitivity of V2 neurons to textures is a consequence of learning a hierarchical representation of natural images. Further, we show that top-down influences are inherent to hierarchical inference. Hierarchical inference explains neural signatures of top-down interactions and reveals how higher-level representation shapes low-level representations through modulation of response mean and noise correlations in V1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hierarchical processing of visual information is a fundamental property of the visual cortex. Recently, deep learning models have emerged as central tools to investigate the hierarchical processing of visual information1. These models rely on a feed-forward processing hierarchy, which enables them to effectively process natural images. A highly successful class of models applied to the visual system are goal-oriented image models, which postulate that the relevant training objective of visual cortical computations is to perform specific tasks, such as classification of inputs into discrete categories. Such goal-directed models have been immensely successful in predicting neuronal responses to natural images, such that progression of processing stages qualitatively matched those of the ventral stream2, as well as in designing synthetic images that elicit specific response patterns in populations of visual cortical neurons3,4. However, images that were specifically designed to confuse the feed-forward model also significantly delayed neural responses, indicating that computations beyond feed-forward processing were recruited by the visual system5.

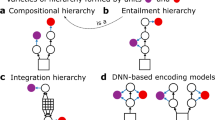

Top-down interactions between the processing stages are ubiquitous in the visual cortex (Fig. 1) but lack a well-established role in goal-directed models of vision. Scrutinizing the computational principles underlying the goal directed models might provide normative arguments why biological vision recruits a more complex architecture and how top-down connections help perceptual processes. Goal-oriented models learn to compress stimulus information such that information relevant for the specific task is retained. For instance, if a model is trained for animal classification, it will excel in this task by recognizing a tiger irrespective of its posture. To achieve this, goal-directed models rely on a learning paradigm called supervised learning, which capitalizes on image and category pairs to train the hierarchical model. Recently, studies have highlighted that the specific task the goal-oriented model is trained on is actually affecting how well a model accounts for neural data6. In contrast with supervised learning of a task-specific neural representation, biological learning imposes two seemingly contradicting requirements. First, representations need to be learned without supervision, i.e., learning in the visual cortex should be performed without a signal what its output should be. Second, the visual system is expected to learn a model of natural images that is not adapted to perform one specific task, instead one that can flexibly perform arbitrary tasks, according to the needs of the current context of the animal. In other words, while under some circumstances it is sufficient to infer if we are facing a tiger or a zebra, in other circumstances it is imperative to precisely judge which movements are plausible based on the current posture of the animal. However, optimization for only one set of task variables (distinguishing different species) does not provide guarantees for efficient computations relying on other variables (evaluating the posture). These requirements motivate a task-independent framework for hierarchical processing in the visual cortex7.

a Example natural image. b Inference in a goal-directed model, which aims to identify categories of images. c Illustration of feed-forward processing in the ventral stream of the visual cortex. d Inference in a hierarchical task-independent model, which permits reverse engineering the contribution of a hierarchical set of features to the observed stimulus. e Illustration of top-down (red arrows) influences supplementing feed-forward processing (blue arrows) along the hierarchy of the ventral stream10. f Computational role of top-down connections. Top: Response intensities of a pair of Z1 neurons (axes) are determined by the features they represent (insets on axes). Interpretation of the image (posterior distribution, empty contours) is the combination of the prior (filled red ellipses) and the evidence carried by the image (likelihood, gray ellipses). Mean response of the neuron (measured across trials, or across a long span of time) is the posterior mean (dot), its correlation is contributing to the noise correlation. Middle: Change of contextual priors upon changes in stimulus statistics. Bottom: Contribution of Z2 neurons to contextual priors in Z1. Saturated colors indicate stronger activation. g Neuronal circuitry of TDVAE that learns a hierarchy of features Z1 (orange) and Z2 (green) corresponding to V1 and V2 in the ventral stream. Features are represented in a layer of neurons (planes with orange and green disks that correspond to individual neurons). Layers of neurons (gray planes) transform feed-forward (Z1-ff, Z2-ff, blue arrows) and top-down information (Z1-TD, red arrow) to ensure precise inference. Integration of feed-forward and top-down information is achieved at Z1-INT. Image credit: (a, f) iStock Photos/Getty Images; (b, d) Users Appaloosa, Patrick Giraud, and VikiUNITED of Wikimedia Commons, user Nikhil Patle of pexels; (c, e) Imaging data provided by the Duke Center for In Vivo Microscopy NIH/NIBIB (P41 EB015897)116,117.

We propose that the ingredient that can address the dual challenge of learning is provided by top-down interactions. We argue that top-down signals have a central role in a class of task-independent learning systems, which has recently achieved considerable success in machine learning applications, deep generative models. Conceptually, top-down interactions establish expectations to support inference8: representing and computing with expectations is a key topic in theories of perception9,10 and was shown to have both neuronal and behavioral correlates8,11,12. Top-down interactions ensure that instead of performing inference at the top of the hierarchy by a simple feed-forward pass of information, inference can be performed at intermediate layers too, which is supported by contextual information fed back from higher levels of hierarchy. Formally, top-down interactions establish a contextual prior which is integrated with evidence, carried by the feed-forward channel, to perform hierarchical inference.

In this study we investigate how a task-independent hierarchical model is acquired through adaptation to natural image statistics. Specifically, we investigate the hierarchical representations learned in a deep generative model from two major directions. First, we seek to characterize learned representations to see if it reflects the properties of the early and mid-level visual cortices, V1 and V2 in particular. Second, we seek to understand if top-down effects found in V1 are aligned with the way high-level representations interact with low-level representations by establishing contextual priors. In order to explore the defining characteristics of this model, we study texture representations, which is motivated by three factors. First, textures are highly relevant features of natural images and critically contribute to higher-level visual processes such as segmentation and object recognition13,14. Second, texture representations have been established in mid-level visual cortices, and in particular in V2, across multiple species, ranging from humans15, through non-human primates16,17,18, to rodents19, suggesting that textures are not only relevant from a machine learning point of view but from a neuroscience point of view as well. Third, while some features that the V2 is sensitive to can be identified with linear computations, textures can only be learned through non-linear computations, a critical component of the successes of deep learning models.

Based on fundamental principles of hierarchical inference, we extend the feed-forward deep learning framework to perform task-independent hierarchical inference (Fig. 1). The adopted Variational Autoencoder (VAE) framework allows unsupervised learning of a nonlinear model of natural images. We develop the hierarchical TDVAE (Top-Down VAE) model, which we train end-to-end on natural image patches. First, to establish the feasibility of the model we contrast the representation learned by the hierarchical TDVAE with the responses of neurons in the early visual cortex of macaques. Next, we investigate the learned properties of top-down connections through a series of experiments that explore two aspects: contextual influences of V2 on V1 responses, and effects of V2 representations on V1 response properties. The proposed framework relies on a feed-forward V1 – V2 pathway and a top-down pathway that avoids direct feedback to the feed-forward components, but integrates feed-forward and top-down components in a distinct population. Through the development of a Variational Autoencoder model, our work provides a normative interpretation of the extensive top-down network present in the visual cortical hierarchy and demonstrates signatures of top-down interactions in neural response patterns.

Results

To investigate the contribution of top-down connections to computations in a normative framework, we introduce a task-independent hierarchical model of natural images. In a hierarchical task-independent model inference aims to establish the presence or absence of a hierarchy of features of different complexities (Fig. 1d). This is phrased as learning a joint distribution over objects and features of different complexities: \(p({{{{\rm{features}}}}}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{{{{\rm{features}}}}}_{{{{\rm{M}}}}},{{{{\rm{features}}}}}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}},{{{\rm{object}}}}\,| \,{{{\rm{image}}}})\). In contrast, a goal-oriented model is trained to make inference only about high-level features, object category in our case (Fig. 1b). Here, p(object ∣ image) is calculated such that object category information is provided during the training to learn a flexible and non-linear mapping from images to object categories1,2,20. In contrast with learning to infer the topmost features of the hierarchy, task-general learning is a more fine-grained form of inference that enables performing not only one particular task, such as viewpoint invariant recognition of objects, but also learning to infer the different aspects of different observations of the same visual component. Given that a task-independent learning is taking place, no category labels are provided at any level of the computational hierarchy. In both model categories, activity of neurons in the hierarchy of the ventral stream are identified with the activities of model neurons at different processing stages but while in goal-directed models intermediate states merely serve the inference of the features at the top level (Fig. 1c), in task-general models neurons at different stages of the ventral stream represent different stages in hierarchical inference (Fig. 1e). In the coming sections, we first introduce the computational principles of hierarchical inference in a task-independent model of natural images; second, we introduce algorithmic details of inference, which provides insights about the circuitry underlying inference; third, the neural circuitry is introduced.

Computational principles of hierarchical inference

We focus on inference on two levels of features: \(p({{{{\rm{features}}}}}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{{{{\rm{features}}}}}_{{{{\rm{M}}}}}| {{{\rm{image}}}})\), which we will refer to as Z1 and Z2 for clarity. Thus, the values in vector Z1 denote the activity of a population of low-level model neurons, while values in Z2 denote the activities of model neurons at the higher layer of the computational hierarchy. Image-evoked activity in Z1 is determined by solving an inference problem:

Here, p(Z1 ∣ image), the posterior distribution, assigns probabilities to different response intensities of the neurons of the Z1 population for a stimulus such that the most likely response intensity corresponds to the most probable value of the feature in the image. Partitioning the joint distribution p(Z1, Z2 ∣ image) provides insights into the dependencies. The feed-forward partitioning solely relies on feed-forward progression of information (see also Methods): p(Z1 ∣ image) ⋅ p(Z2 ∣ Z1). In contrast, the top-down partitioning also relies on top-down interactions between processing stages: p(Z1 ∣ Z2, image) ⋅ p(Z2 ∣ image). These formulations provide mathematically equivalent formulations to the inference problem and as such either of these could be used to learn a hierarchical task-independent model. However, inference is only approximated and one of the most effective approximations, variational inference, terminates equivalence21. Motivated by the top-down interactions characteristic of the anatomy of the visual cortex22, we focus on hierarchical inference that recruits top-down interactions besides feed-forward processing (Fig. 1e). In our study we will seek to establish links between model neurons in Z1 and Z2 with neurons in V1 and V2 regions of the visual cortex. Specifically, we identify Z1 responses with layer 2/3 responses in V1 (see later in this section). Although the circuitry for inference is more complex than a single layer, for the sake of simplicity, we refer to the Z1 neurons as V1 throughout the paper. In order to assess potential differences of the two partitionings of the joint distribution, we also investigate the feed-forward parametrization.

A key insight of the top-down component in hierarchical inference becomes evident when the interpretation of an input image becomes uncertain as a consequence of poor viewing conditions, occlusion, or noise (Fig. 1a). Under uncertainty, an observer needs to rely on their prior23,24 (Fig. 1f, top), which carries information about learned regularities in the environment. Importantly, regularities change from environment to environment, implying that an observer knowledgeable about the environment shall rely on local environment-dependent priors, termed contextual priors (Fig. 1f, middle). According to hierarchical inference, those are the Z2 neurons that can provide contextual priors for Z1 neurons through top-down connections, as patterns in top-down connections reflect the statistics of the local context. This provides the flexibility to alter the contextual information of Z1 neurons through different activation patterns in Z2 (Fig. 1f, bottom).

Algorithmic solution to hierarchical inference

In order to train a network to perform hierarchical inference in a task-independent model of images, we turn to the Variational Autoencoder (VAE) formalism25,26. VAEs learn a pair of models: the recognition model supports inference, i.e. it describes the probability that a particular feature combination underlies an observed image; and the generative model, which summarizes the ‘mechanics’ of the environment, i.e. how the combination of features produces observations (see Methods for details, Supplementary Fig. 1). Relying on advances in hierarchical versions of VAEs27,28, we developed Top-Down VAE, or TDVAE for short (Fig. 1g). We constructed the TDVAE model based on two principles. First, the computational framework is determined by a highly principled approximation in probabilistic inference but apart from the well-motivated restrictions (optimizing a lower bound to the true objective, performing amortized variational inference, deterministic propagation of signals across layers of the hierarchy), the TDVAE was left as general as possible such that its properties were determined solely by natural image statistics. Second, we capitalized on neuroscience intuitions about V1 and V2 to constrain the architecture for learning about low- and mid-level features, Z1 and Z2. Along this line, we assumed sparseness in the generative model29 (Methods). Further, we assumed a linear relationship between the features that Z1 neurons are sensitive to and the pixels of natural images29,30. At the level of Z2, the generative model allowed flexible nonlinear computations such that more complex feature sets can be learned. Next, as the recognition model ultimately defines the neural circuitry for hierarchical inference, we relied on anatomical insights (Fig. 1g). The top-down formulation requires computing two components: p(Z1 ∣ Z2, image), and p(Z2 ∣ image). In a VAE formalism, these components are calculated by neural networks. We used the same feed-forward pathway to process image information (Fig. 1g), implemented by the neural network that is denoted by Z1-ff, which pathway forked into a pathway reaching Z1 and another reaching Z2, the latter implemented by the neural network denoted by Z2-ff. This joint feed-forward component ensures that no direct connection to Z2 is assumed. The top-down information (Fig. 1g), implemented by the neural network that is denoted by Z2-TD, is integrated with the feed-forward pathway in a neural network denoted by Z1-INT before reaching Z1 (Fig. 1g, see also Methods), reminiscent of the integration of the likelihood and prior for Bayesian inference. The joint feed-forward pathway is analogous to parameter sharing, a widely used approach in machine learning28,31. In order to demonstrate that the shared feed-forward pathway does not limit the performance of the TDVAE model, we have also implemented the alternative model with distinct feed-forward pathways (see later).

The full computational graph of the TDVAE describes the way the input is processed through subsequent layers to infer Z1 and Z2, as well as the way the generative component contributes to the reconstruction of the input, the precision of which ultimately drives learning (Supplementary Fig. 1). In this paper we focus on the analysis of the recognition model, that is, activities of model neurons in Z1 and Z2 are used to predict patterns in cortical neural activities (Fig. 1g).

Z1 and Z2 activations in TDVAE are assumed to correspond to activations of V1 and V2 neurons up to a linear combination of the variables (see Methods for details), standard in earlier approaches2. The probabilistic nature of inference (Eq. (1)) necessitates that we define how probability distributions are represented. In a non-probabilistic approach the neural response would be identified with the maximum of the distribution. In neural data, this maximum a posteriori response can be identified with the trial-averaged response and variance is interpreted as mere noise in the circuitry. For a probabilistic interpretation of neural responses, we adopt the sampling hypothesis32. The sampling hypothesis takes a stochastic approximation to represent a probability distribution. According to this, neural activity at any given time is a stochastic sample taken from the probability distribution and the sequence of samples constitutes the distribution, with mean of the neural activity corresponding to the most probable interpretation of the stimulus (see also Methods). Thus, mean of p(Z1 ∣ image) and p(Z2 ∣ image), referred to as posteriors, corresponds to the mean response of the V1 and V2 neurons. Spike count collected in a time window corresponds to a finite number of samples from the posterior therefore it is expected to show considerable variance around the mean posterior, which can be reduced through averaging across trials. At the level of V1, a single sample can be identified with an activity from a 20 ms time window33. Width of the posteriors is reflected in response variance, while correlations in the posterior are reflected in noise correlations34,35. Importantly, noise correlations can be produced by various sources36, and thus our interpretation corresponds to a form of noise correlation that results from high-level perceptual variables. In this paper response variances are not investigated in detail but we refer the reader to earlier work37,38. In practice, we collect samples from the variational posteriors of Z1 and Z2, which is then compared to responses of V1 and V2 neurons in electrophysiology experiments. The number of these samples is set to approximate the specific experimental conditions TDVAE responses are tested on (see Methods). Activity of model neurons are not constrained to be positive and therefore are identified with membrane potentials, similar to earlier approaches37 (see Methods for details). The presented results can be translated to firing rates by transforming membrane potentials with a threshold-linear transformation37,39. We motivate reporting results on the untransformed activities of Z1 and Z2 in order to demonstrate that the results of an end-to-end natural image trained VAE can be directly applied to predict neural data.

Neural circuitry for hierarchical inference

We investigate activity of Z1 and Z2 of the recognition model. As these deliver the result of inference, read by downstream structures, we relate their activities to layer 2/3 of V1 and V2. This assumption is well aligned with the fact that layer 2/3 integrates feed-forward and top-down information40. While we do not expect that the neural circuitry is fully determined by the computational architecture proposed here, it is a useful exercise to consider potential mapping between the two. The joint feed-forward component of the recognition model (Fig. 1g, Z1-ff) can be considered as layer 4 neurons in V1, receiving relatively unfiltered input from LGN40, and sending projections within V1 as well as feed-forward input to V241. The top-down information initially reaches V1 at Z1-INT (Fig. 1g) before converging on Z1. Z1-INT is in a similar position as layer 5 neurons of V1, known to receive top-down input42,43. Note that the computational graph does not rely on direct forward projections from Z1 towards Z2, thus avoiding dense recurrent information flow. Extensive layer 2/3 forward connections that are characteristic of V140,41 are not exploited by the recognition model and thus can serve further elaboration of the posterior.

To investigate the representations emerging as a result of adaptation to natural image statistics23,24, we trained the TDVAE model end-to-end on natural image patches (Methods). To demonstrate the invariance of our results on the specific choice of the generative and recognition models, we trained an array of models with different parametrizations, including the feed-forward partitioning of the posterior (Eq. (1)) and an untrained TDVAE model (see Methods). The goodness of these alternative models was established through calculating the value of the optimization objective (ELBO, Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table 3, Methods) and the model having the highest ELBO was used in the main text of the study, while alternatives are presented as Supplementary Information. Inference in the model was validated by contrasting the match between inference in the recognition and in the generative models (see Methods for details and Supplementary Fig. 1). We tested a model alternative, in which parameter sharing was not present in the two components of the recognition model. We performed the comparison on a smaller model that used 20 × 20-pixel image patches instead of the default 40 × 40-pixel patches. Simulations did not identify major performance or qualitative differences ( − 400, distinct pathways: − 407; see also Supplementary Table 3; see also Methods). Apart from these architectural choices, TDVAE has no free parameters that are fitted to neural data: all parameters are determined by natural image statistics.

a Loss function of alternative models. Shallow-VAE: non-hierarchical VAE constrained to Z1, yielding a linear model of V1; ffVAE: hierarchical VAE with feed-forward processing; TDVAE: variants of hierarchical VAEs with top-down processing. Linear integration: feed-forward and top-down pathways are linearly combined to reach Z1; shallow nonlinearity: generative model between Z2 and Z1 relies on single-layer MLP (Supplementary Table 2); deep nonlinearity: as above but with two-layer MLP. Untrained: Model with random parameters. b Top: The first-order and an example second-order receptive field, as well as the orientation tuning (STA, STC, and ori., respectively, see Methods) of a selected active Z2 neuron, together with power spectra (PS). Bottom: Example first-order receptive fields of six Z1 units. c Examples from the 15 texture families (colors) used in the paper. d Texture family decoding accuracies from different layers of the hierarchy. Means of n = 5 fits are shown; s.d. < 0.01 everywhere. Black line: chance performance. Pixels: direct decoding from images. Labels as in (a). CORnet: goal-directed feed-forward model. e Two-dimensional visualization (t-SNE) of mean responses of Z1 and Z2 neurons to randomly sampled texture images (dots). Colors as on panel (c). Disks: means across samples from a family. f Same as (e) but in V1 and V2 recordings from macaques. Reproduced with permission from17(PNAS). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Hierarchical representation of natural images

First, we investigate the representations that emerge in TDVAE. At the level of Z1, we found that TDVAE robustly learns a complete dictionary of Gabor-like filters (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 3). The receptive fields of individual model neurons are localized, oriented, and bandpass (Supplementary Fig. 4), qualitatively matching those obtained by training a VAE lacking a Z2 layer (Supplementary Fig. 5). This result confirms earlier studies using single layer linear generative models featuring sparsity constraint on neural activations29,30. Thus, learning a hierarchical representation complete with a Z2 layer on top of Z1 left the qualitative features of the Z1 representation intact in the TDVAE model.

Unlike the compact receptive fields of Z1 model neurons, the representation at the Z2 layer has no noticeable linear structure (Fig. 2b STA). The second-order, nonlinear receptive fields and the orientation tuning curves of Z2 units, however, reveal orientation and wavelength selectivity (Fig. 2b STC and ori., Methods), offering a first glimpse into the representation learned by the Z2 layer.

Inspired by extensive evidence supporting that V2 neurons are sensitive to texture-like structures15,19,44, we used synthetic texture patches to further explore the properties of the Z2 representation that TDVAE learned on natural images45. We selected 15 natural textures characterized by dominant wavelengths compatible with the image patch size used in the study (Fig. 2c, Methods). We matched low-level texture family statistics (Methods), thus making texture families linearly indistinguishable in the pixel space (Fig. 2d, Methods). Since model Z1 neurons learn a linear mapping from the neural space to the pixel space, we expect that texture information cannot be read out with a linear decoder from Z1 response intensities either. Decoders that queried the texture family that a particular image was sampled from but ignored the identity of the image showed low performance on model Z1 neurons, which was still distinct from chance (0.1943 ± 0.0012, error denotes standard deviation over five repeats of the fit, Fig. 2d ‘Z1, TDVAE’). The non-hierarchical version of VAE that completely lacked a Z2 was slightly outperformed by TDVAE (compare 0.1073 ± 0.0020 with 0.1943 ± 0.0012 for ‘Z1, shallow-VAE’ and ‘Z1, TDVAE’, respectively, Fig. 2d).

Nonlinear components in the generative model endow the Z2 with building a representation that is capable of distinguishing texture families such that textures can be effectively represented in this layer. Texture was reliably decodable from the response intensities of Z2 neurons of TDVAE (0.8761 ± 0.0001, ‘Z2, TDVAE’, Fig. 2d). This texture representation was very robust as it was qualitatively similar for all investigated hierarchical architectures (Supplementary Table 4). The texture representation discovered by TDVAE was low dimensional, irrespective of the architectural details of the model (Supplementary Table 4). This finding is surprising but recent experiments have confirmed that even though textures are represented by large neuron populations in the V2 of macaques, the effective dimensionality of this representation is very limited19. Intriguingly, the TDVAE architecture best fitting natural images only featured texture-selective dimensions, yielding a very compact representation exclusively focusing on textures (Supplementary Tables 3, 4). Responses of the Z2 population displayed clustering by the texture family (Fig. 2e), similar to the representations identified in V2 neuron populations in macaque (Fig. 2f). In contrast, no such clustering could be identified in Z1 (Fig. 2e), reminiscent of V1 neuron populations of the same macaque recordings (Fig. 2f).

We introduced three alternative models as controls to our TDVAE model. First, we investigated a model that had identical architecture to the TDVAE but was not adapted to natural images. Second, we tested the robustness of the learned texture representation against the form of partitioning of the posterior distribution. Third, representation learned by a goal directed feed-forward model was tested. The untrained model showed slightly higher decoding performance on texture families in Z1 (compare 0.2850 ± 0.0078 with 0.1943 ± 0.0012 for ‘Z1, untrained’ and ‘Z1, TDVAE’, respectively, Fig. 2d) but, in contrast with TDVAE, markedly lower performance in Z2 than the TDVAE (compare 0.0820 ± 0.0076 with 0.8761 ± 0.0001 for ‘Z2, untrained’ and ‘Z2, TDVAE’, respectively, Fig. 2d). The contra-intuitive higher Z1 result is explained by the fact that decoding is performed from a large dimensional space (matching the dimensionality of active Z1 dimensions) and the non-linear recognition model has the potential to distribute responses of Z1 such that it carries texture family information. As it is the generative model that assumes linear relationship between Z1 and pixel activations, the nonlinear recognition model ‘unlearns’ texture decodability as the generative and recognition models are jointly adapted to natural images. In contrast with TDVAE, no clustering was found in either Z1 or Z2 of the untrained model (Supplementary Fig. 6a).

The variant of TDVAE using feed-forward partitioning of the joint posterior distribution instead of top-down partitioning, ffVAE (feed-forward VAE), showed limited texture family decodability from Z1 (0.0930 ± 0.0003, ‘Z1, ffVAE’) and high texture family decodability from Z2 (0.9150 ± 0.0002, ‘Z2, ffVAE’, Fig. 2d), similar to TDVAE. This underlines the robustness of the learned texture representation against the exact implementation of the recognition model.

We have contrasted the hierarchical representation learned by TDVAE with that of a goal-directed model. We used a standard feed-forward implementation available in the literature, the CORnet model46. The CORnet model was trained on ImageNet and we designed analyses analogous to those performed with TDVAE (see Methods). In particular, we sought to identify layers across the processing hierarchy that bear similarities with Z1 and Z2 of TDVAE. Early layers with localized and orientation sensitive filters could be identified in this goal-directed model. Texture family decoding was not possible from the responses of this layer (0.1303 ± 0.0005, ‘Z1, CORnet’, Fig. 2d), but layers immediately above this layer were characterized by a representation from which texture family decoding was effective (0.9770 ± 0.0003, ‘Z2, CORnet’, Fig. 2d).

We investigated the representation learned by TDVAE further in order to contrast it with more specific properties of the representation found in V1 and V2. We first investigated the learned invariances of TDVAE. Mean responses of individual Z1 neurons displayed a high level of variability both across instances of texture images belonging to the same texture family and those belonging to different texture families (Fig. 3a). This tendency was similar to the sensitivities displayed by V1 neurons in the macaque visual cortex (Fig. 3b). In contrast, Z2 neurons displayed a higher level of invariance across texture images belonging to the same texture family (Fig. 3a), again reflecting the properties of macaque V2 neurons (Fig. 3b). To quantify this observation, across-population statistics was calculated by dissecting across-sample and across-family variances in mean responses both in Z1 and Z2 neurons of TDVAE using a nested ANOVA method17. Note, that in order to make our analysis more general by permitting an arbitrary linear mapping between model Z2 neurons and biological neurons, we used a random rotation of Z2 to perform the analysis (Methods). The relative magnitude of response variance across families versus across samples was significantly higher in Z2 than in Z1 (Fig. 3c), corroborating experimental findings (Fig. 3d).

a Mean responses of one example neuron from Z2 and one example neuron from Z1 (rows two and three, respectively) to three example images from three texture families each (top). Bottom: Variability of mean responses of the same two neurons across 4000 images in each of the 15 texture families (colors; center lines: means, whiskers: extrema). b Same as (a) top in V1 and V2 recordings from macaque monkeys. c Left: Partitioning single-unit response variances into variance across images from different families, variance across images within families and a residual component (across stimulus repetitions) with nested ANOVA both in Z2 and Z1 (n = 100 neurons, dots). Insets: Distribution of the sum of the first two components of variance. Right: Distribution of the ratio of the first two components. Geometric mean of variance ratios (triangles) is significantly smaller in Z1 (0.064) than in Z2 (2.097) (one-sided independent two-sample t-test in the log domain, t(df = 198) = − 32.7, p = 6.5 × 10−82, \({d}_{e}^{{\prime} }=4.7\), 95% confidence interval = [−∞, −3.3]). Here and later in the paper, \({d}_{e}^{{\prime} }\) denotes the average sd discriminability index. d Same as (c) in 102 V1 and 103 V2 units from a pool of 13 macaque monkeys. e Decoding texture family (red) and within-family stimulus identity (black) from the same 100 Z1 and Z2 units (horizontal axis and vertical axis, respectively) as in (c). Dot sizes: decoding on randomly selected subpopulations (n = 1, 3, 10, 30, 100). Solid line: Chance performance. Dot centers: means; error bars: 95% confidence intervals of bootstrapping over included neurons and partitionings. f Same as (e) from single unit V1 and V2 macaque recordings. g Phase scrambling-induced modulation of the magnitude of mean responses to texture images in the same 100 Z2 (top) and Z1 (bottom) neurons as in (c). Mean modulation index (triangles) is significantly smaller in Z1 (−0.062) than in Z2 (0.027) (one-sided independent two-sample t-test, t(df = 198) = −12.4, p = 8.6 × 10−27, \({d}_{e}^{{\prime} }=1.77\), 95% confidence interval = [−∞, −0.077]). h Same as (g) from V1 and V2 recordings in macaques. Experimental data panels are reproduced with permission from PNAS (b−f 17) and SNCSC (h16). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Higher invariance of responses to different stimuli belonging to the same texture family in Z2 than in Z1 can also be captured by a linear decoding analysis (Fig. 3e). Efficiency of discrimination between images in the same texture family is weaker in Z2 than that of Z1 (Fig. 3e). Such increasing invariance to lower-level features along the visual hierarchy is a hallmark of gradual compression and can be identified at the population level in the primate visual cortex as well (Fig. 3f). In contrast with within-family stimulus identity decoding, decoding of texture family is more efficient from Z2 than from Z1 in TDVAE (Fig. 3e), a finding confirmed by macaque recordings (Fig. 3f).

Texture families can be defined through a set of pairwise statistics over the co-activations of linear filters represented in Z1/V145. To demonstrate that the learned Z2 representation reflects these quintessential features of a proper texture representation, the TDVAE model can be tested with stimuli in which these high-level statistics are selectively manipulated while keeping the low-level statistics intact (Methods). To achieve this, we used phase scrambling of images16. As texture sensitive neurons are assumed to be sensitive to high-level statistics, their removal is expected to reduce Z2 activations. For this, a modulation index was calculated for each neuron, which was defined as the difference between sample- and presentation-averaged absolute responses to undisturbed texture images and their phase scrambled counterparts normalized by their sum. Texture-sensitive units in Z2 showed higher modulation than active units in Z1 (Fig. 3g), in line with findings in macaque recordings (Fig. 3h).

In summary, Z1 and Z2 representations of TDVAE display key features of V1 and V2 representations of the macaque visual cortex. In particular, an elaborate texture representation is a salient feature of hierarchical representations of natural images.

Top-down contributions to hierarchical inference

In a task-independent model inference can be performed on all levels of the hierarchy (Fig. 1d). According to equation (1), top-down influences affect the inference of Z1 activities through establishing a contextual prior for Z1 (Fig. 1f). Importantly, contrary to simple Bayesian computations, this prior is not an invariant component, instead it depends on the higher-level interpretation of the scene. In the following sections we seek to identify signatures of this contextual prior in Z1 response statistics: first on mean responses, second on response correlations.

Top-down influences can be expected when local interpretation of images depends on the surroundings. Establishing a wider context is directly supported by the growing receptive field sizes in higher hierarchical layers of TDVAE. To study top-down influences in detail, we rely on an implementation of TDVAE, which is trained on larger (50-pixel, see Methods) natural image patches than our standard model, which was trained on 40-pixel images. While the larger patch size requires more careful training, it offers a more precise evaluation of contextual effects. A particularly strong form of contextual effect can be established by selectively blocking direct stimulus effects from designated Z1 neurons and therefore top-down effects can be studied in isolation by investigating the emerging Z1 activation. This ‘illusory’ activity in Z1 neurons resonates with the interpretation of illusions as the contribution of priors to perception under uncertainty47. We constructed illusory contour stimuli by creating Kanizsa square stimuli (Fig. 4a) such that illusory contour segments were aligned to individual Z1 neurons and measured mean responses (Fig. 4b). We compared Kanizsa-elicited responses to both unobstructed images of squares and to control stimuli that were built from identical elements to the Kanizsa stimuli but in configurations not congruent with the percept of a square. Illusory edge responses were similar to unobstructed square stimulus-evoked responses, albeit with a lower gain for the illusory edge (Fig. 4b), similar to responses of V1 neurons of macaques48 (Fig. 4c). Confirming expectations, responses to Kanizsa-incongruent stimulus elements were muted (Fig. 4b), again reproducing experimental findings (Fig. 4c). This tendency was consistent across the model neurons investigated using stimuli that were tailored to their response properties (see Methods, Fig. 4d).

a Illustration of the illusory contour experiment. Left: receptive field of an example model Z1 neuron. Middle: receptive field-aligned Kanizsa square stimulus. Red border indicates the actual boundary of the stimulus. Arrow: direction of shifts of the stimulus relative to the neural receptive field. Right: real square (`Line'), Kanizsa square (`Illusory') and incongruent (`Rotated') stimuli. b Mean responses of the Z1 neuron in (a) to 500 presentations of the three stimuli as a function of stimulus shift. Shaded regions (invisibly small): s.e.m. c Same as (b) for a selected unit in the V1 of a macaque monkey. Number of trials is unknown. Reproduced from48 with permission (PNAS, Copyright (2001) National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A.). d Ratio of mean Z1 responses to `Illusory' and `Line' stimuli and to `Rotated' and `Line' stimuli, respectively, at the `Line' response peak, for the largest stimulus sizes that fit into the patch, for the analyzed Z1 population (n = 114 = (57 central, localized, medium wavelength Z1 filters) × (upright and upside-down stimulus orientations), Methods; center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5 × interquartile range). Mean peak ratios: 0.70 (`Illusory'), 0.23 (`Rotated'), the latter being significantly less than the former (one-sided paired two-sample t-test, t(df = 113) = 4.3, p = 1.6 × 10−5, \({d}_{e}^{{\prime} }=0.39\), 95% confidence interval = [0.29, ∞]). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; n.s., p≥0.05 in this and all subsequent Figures. e Same as (b) for the `Line' and `Illusory' stimuli, together with linear responses of the Z1 neuron (dashed lines). Magnitude of the linear response to the `Line' stimulus was scaled to the mean response peak to the `Line' stimulus. Shaded regions (invisibly small): s.e.m. f Same as (e) for the `Line' and `Rotated' stimuli. g Differences between the mean and linear responses to the `Illusory' stimulus (center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5 × interquartile range). Left: Same restricted Z1 population of TDVAE in three different conditions (n = 9 each; see text, Methods): intact inference in Z1 (mean model-linear response difference (0.076) is positive: one-sided one-sample t-test against 0: t(df = 8) = 4.7, p = 0.00076, 95% confidence interval = [0.046, ∞]), inference without stimulus-specific information at Z2 (mean model-linear response difference (−0.068) is not significant: two-sided one-sample t-test against 0: t(df = 8) = − 0.71, p = 0.50, 95% confidence interval = [−0.29, 0.15]), inference with Z2 clamped to zero (mean model-linear response difference (0.014) is significant: one-sided one-sample t-test against 0: t(df = 8) = 2.9, p = 0.011, 95% confidence interval = [0.0049, ∞], but smaller than TDVAE with intact inference: one-sided paired two-sample t-test: t(df = 8) = − 4.2, p = 0.0015, \({d}_{e}^{{\prime} }=2.07\), 95% confidence interval = [−∞, −0.034]). Right: Illusory responses in two control models: shallow-VAE (n = 29; mean model-linear response difference (0.011) is positive: one-sided one-sample t-test against 0: t(df = 28) = 3.2, p = 0.0016, 95% confidence interval = [0.0050, ∞], but smaller than TDVAE with intact inference: one-sided independent two-sample t-test: t(df = 36) = − 6.1, p = 2.2 × 10−7, \({d}_{e}^{{\prime} }=2.06\), 95% confidence interval = [−∞, −0.047]), and feed-forward goal-directed model (n = 40; mean model-linear response difference (−0.00030) is not significant: two-sided one-sample t-test against 0: t(df = 39) = −0.37, p = 0.71, 95% confidence interval = [−0.0019, 0.0013]). Filled circle: significant boosting or suppression. Hollow circle: no significant effect. Square: deterministic model. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Using the TDVAE model, we designed a stricter control. Overlap between the receptive field of Z1 neurons with the elements of the Kanizsa stimulus could contribute to model responses. To isolate top-down effects, we calculated linear responses of the neurons to the Kanizsa stimuli (Fig. 4e). We found significant boosting of the linear response in TDVAE for the example neuron. By restricting the set of analyzed neurons to those having (1) only a small overlap between the ‘Illusory’ stimulus and the receptive field and (2) all four response peaks in Fig. 4e close to each other (a proxy of regular peak shapes), consistent boosting was observed (n = 9; significant boosting: n = 9, one-sided one-sample t-tests, P < 0.05; population statistics: Fig. 4g, Methods). Incongruent Kanizsa stimuli produced limited and inconsistent modulation in the same set of Z1 neurons (n = 9; significant boosting: n = 5, significant suppression: n = 3, one-sided one-sample t-tests, P < 0.05; population statistics: Supplementary Fig. 6b). Confirming the contributions of top-down connections to illusory activity, modulation of Z1 responses was significantly weaker in a model that lacked Z2 than in the TDVAE model (Fig. 4g).

To explicitly investigate the contribution of Z2 to illusory responses in Z1, we manipulated Z2 in two different ways. First, to simulate severing feed-forward connections to Z2, we removed stimulus information by sampling the prior of Z2 instead of the posterior when presenting a Kanizsa stimulus. As predicted, severing feed-forward connections results in TDVAE responses matching linear responses (Fig. 4g). Second, as a proxy to severing feedback connections, we simulated illusory contour responses in Z1 by clamping Z2 responses to zero. This also showed modulations similar to the shallow-VAE rather then those of TDVAE (Fig. 4g). To show that illusory contour responses are a consequence of learning in the task-general model, we repeated the experiment with the goal-directed feed-forward model. No illusory contour responses were observed in this goal-directed model (Fig. 4g).

In non-human primates, extensive evidence supports that stimulus which resonates with the sensitivities of higher-order visual areas produce top-down effects in V149,50. A simple analysis of texture-level information in Z1 provides a strong indication that statistics represented at Z2 flows back to Z1 through top-down connections: we performed texture decoding both with intact Z2 and with removing stimulus information from it. This analysis confirmed that the small but significant decodability of texture-family information in Z1 was a consequence of top-down feedback from Z2 (Fig. 5a). Direct ablation of V2 inputs is currently not widespread in neuroscience research, instead experimental studies use the temporal evolution of V1 signals to distinguish feed-forward and top-down components. We model this effect by assuming that without direct stimulus contribution the cortex samples the prior12,32,51. Thus, pre-stimulus responses were calculated by sampling the prior of both Z1 and Z2, while at early-stimulus responses we assumed that stimulus information reaches Z1 but Z2 responses still rely on the prior. Only late responses showed illusory activity in Z1 (Fig. 5b), consistent with late-emergence of illusory contour responses in macaques48. Similar late-emerging top-down effects were identified when high-level statistics of stimuli was manipulated through phase scrambling (Fig. 5c) and when large-scale integration of visual elements was disrupted by manipulating contours (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 6c, d). These results are confirming results obtained from electrophysiology recordings from V1 of macaques when presenting stimuli matching those used in our experiments49,50.

a Mean performance of texture family decoder from mean responses of Z1 with intact inference (0.1943) is higher than without stimulus-specific information at Z2 (0.0986) (n = 5 fits from different random seeds; one-sided independent two-sample t-test: t(df = 8) = 70, p = 9.6 × 10−13, \({d}_{e}^{{\prime} }=52.4\), 95% confidence interval = [0.093, ∞]). Bar heights: means; s.d. < 0.01 everywhere. b Qualitative time course of illusory contour responses in the same restricted Z1 population in TDVAE as in Fig. 4g (n = 9 Z1 units everywhere; two-sided one-sample t-test against 0 everywhere except late Illusory; pre Illusory: mean: 0.0011, t(df = 8) = 0.72, p = 0.49, 95% confidence interval = [−0.0025, 0.0047]; pre Rotated: mean: 0.00077, t(df = 8) = 0.47, p = 0.65, 95% confidence interval = [−0.0030, 0.0045]; early Illusory: mean: −0.068, t(df = 8) = −0.71, p = 0.50, 95% confidence interval = [−0.29, 0.15]; early Rotated: mean: −0.091, t(df = 8) = −0.85, p = 0.42, 95% confidence interval = [−0.34, 0.16]; late Illusory: mean: 0.076, one-sided one-sample t-test against 0: t(df = 8) = 4.7, p = 0.00076, 95% confidence interval = [0.046, ∞]; late Rotated: mean: 0.0065, t(df = 8) = 0.92, p = 0.39, 95% confidence interval = [−0.0098, 0.023]). Center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5 × interquartile range. Inset: example stimuli. c Qualitative time course of texture family decoding performance from intact and phase-scrambled versions of textures (n = 5 fits from different random seeds; mean accuracies ± stds: pre: 0.0680 ± 0.0007, early: 0.0986 ± 0.0025, early scrambled: 0.1007 ± 0.0012, late: 0.1943 ± 0.0012, late scrambled: 0.1709 ± 0.0020; two-sided independent two-sample t-test between early and early scrambled: t(df = 8) = −1.6, p = 0.15, \({d}_{e}^{{\prime} }=1.19\), 95% confidence interval = [−0.0053, 0.00098]; one-sided independent two-sample t-test between late and late scrambled: t(df = 8) = 20.3, p = 1.8 × 10−8, \({d}_{e}^{{\prime} }=14.8\), 95% confidence interval = [0.021, ∞]). Bar heights: means; s.d. < 0.01 everywhere. Inset: example stimuli. d Qualitative time course of contour completion experiment. Top: Illustration of stimuli. Optimally oriented, identical line segment is shown in the receptive field of a Z1 neuron (left) under the condition that the neighboring visual field is filled with randomly oriented segments (center) or the neighboring segments continue the segment that covers the receptive field (right). Bottom: Qualitative time course of the response intensity difference between the contour completion and random conditions in the Z1 population (n = 57 central, localized, medium wavelength Z1 filters in TDVAE in both cases; early: mean effect size: −0.080, two-sided one-sample t-test against 0: t(df = 56) = −0.65, p = 0.52, 95% confidence interval = [−0.33, 0.17]; late: mean effect size: 0.36, one-sided one-sample t-test against 0: t(df = 56) = 3.9, p = 0.00014, 95% confidence interval = [0.21, ∞]). Center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5 × interquartile range. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Response correlations emerging through contextual priors

Illusory contour, contour integration, and phase scrambling experiments demonstrate how contextual priors affect V1 neurons through features represented higher in the cortical hierarchy, V2 in our specific case. These contextual priors carry information about the regularities of the surroundings of a neuron’s receptive field, such as the tendency of another neuron to be jointly active in the local environment. These regularities in the local environment can change from image to image and thus the changing contextual prior dictates different co-activation patterns between neurons (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Fig. 7a). Such stimulus-specific co-activation patterns are captured in correlations between neuronal responses to individual images and thus noise correlations. Indeed, across-stimulus dissimilarity of noise correlations is larger than that expected from estimating noise correlations from a finite sample (Fig. 6b). Noise correlations provide us with a tool to identify and characterize top-down influences as contextual priors contribute to these. Importantly, if regularities in a set of images are similar, the contextual prior and thus the noise correlations are not changing, therefore texture family-specific activity in V2 is expected to induce texture family-specific noise correlations in V1 (Fig. 6c).

a Z1 noise correlations for n = 40 neurons with central, localized, medium wavelength receptive fields for two example natural images (left). Center: Effect of sampling noise. Comparison of noise correlations from two independent sets of trials (n = 80 each, lower and upper triangles, respectively). Right: across-image noise correlation differences. Data taken from the central column (border colors matching those in the middle column). b Within- and across-image dissimilarity of noise correlations (from n = 80 trials each), averaged over 10 images (inset). Mean dissimilarity of noise correlations within images (0.104) is smaller than across images (0.488) (one-sided independent two-sample t-test, t(df = 188) = −38.5, p = 1.9 × 10−91, \({d}_{e}^{{\prime} }=13.1\), 95% confidence interval = [−∞, −0.37]). Data are presented as mean values ± s.e.m. c Top: Response covariance of two Z1 neurons to individual images. Dashed and dotted covariance ellipses correspond to the two inset images. Solid ellipses: average covariance ellipses for n = 80 images per texture family. Left and right columns: two example texture families. Text labels: per-family mean noise correlation coefficients. Bottom: Trial-averaged mean responses of the same Z1 units to n = 80 images (dots) from the same texture family as top. Covariance ellipses, text labels: signal correlations calculated from these responses. d Texture family decoding performance from Z1 (n = 100) and Z2 (n = 6) mean responses (as in Fig. 2d) and Z1 noise correlations (from the same n = 100 Z1 units as for Z1 means). Decoders were constructed for texture images, as well as phase and filter scrambled versions of these. Bar heights: means for n = 5 random seeds; s.d. < 0.01 everywhere. Black line: chance performance. e Relationship between noise and signal correlations for a population of Z1 (n = 40 Z1 units) neuron pairs (dots) for two texture families. Colors and data as in panel (c). f Across-stimulus dissimilarity of noise correlations (20 natural images, four noise correlation matrices per image, each calculated from 80 trials). Mean dissimilarity for intact images (0.503) is larger than for phase scrambled images (0.479) (one-sided paired two-sample t-test, t(df = 3039) = 25.4, p = 3.2 × 10−129, \({d}_{e}^{{\prime} }=0.54\), 95% confidence interval = [0.023, ∞]), and also larger than for filter scrambled versions (mean for filter scrambled images: 0.333, one-sided paired two-sample t-test, t(df = 3039) = 87.4, p < 1 × 10−100, \({d}_{e}^{{\prime} }=2.6\), 95% confidence interval = [0.17, ∞]). Bar heights: means; error bars: s.e.m. g Same as (f) in V1 multiunit recordings from two macaque monkeys. The two comparisons were calculated from data recorded in distinct experimental sessions. Number of noise correlation dissimilarity metric data points: phase scrambled vs. original: n = 645; filter scrambled vs. original: n = 7469. Data are presented as mean values ± s.e.m. Regenerated from the data of34 with permission from the authors (M. Bányai, personal communication 2025). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We measured the texture-family specificity of noise correlations in the TDVAE model by constructing linear decoders that we applied to noise correlation matrices of a small Z1 neuron population (Fig. 6d). In order to demonstrate the contribution of top-down interactions, we capitalize on a specific property of TDVAE. At a given stimulus and a specific level of Z2 response, the variational posterior is chosen to be a Laplace distribution, and specifically a variant that is free of correlations. However, as Z2 response is not a given number but a distribution over possible values as defined by the posterior, variations in Z2 might induce covariations in Z1. Consequently, in TDVAE, it is the top-down influence that is exclusively responsible for the covariability of Z1 neurons. To disentangle top-down correlations from private variability, we use the changes in the mean of the posterior of Z1, which is resulting from sampling Z2, to assess correlations. Additional private variability reduces the magnitude of noise correlations but it does not affect the overall trends reported in this section. As Z2 response means show linear decodability of texture family information, linear decoding of texture family from Z1 correlations was also highly effective (Fig. 6d). In addition, stimulus manipulations weakening the texture representation in Z2 like phase and filter scrambling also reduce the texture family decodability from Z1 correlations (Fig. 6d). In contrast to Z1 response correlations, Z1 response means are worse suited to linear decoding of texture family information (Fig. 6d).

The contextual prior reflects the regularities of the environment that are specific to the particular context. For texture families, the tendency of a pair of neurons to be jointly active for different texture images, referred to as signal correlation, is expected to be captured by the contextual prior of a well trained model. Indeed, Karklin and Lewicki argued that the correlations between mean filter responses is characteristic to texture families52, and we also found that such texture family-specific signal correlations were present between an example pair of neurons (Fig. 6c). Thus, the contextual prior is related to two different forms of joint response statistics: the signal correlations, measuring correlations between mean responses across images, and the noise correlations, measuring correlations between neurons following multiple presentations of the same image. Therefore, we measured for every texture family the relationship between these two quantities for a large number of Z1 neuron pairs. We found strong dependence of noise correlations on signal correlations in the responses of pairs of Z1 neurons (Fig. 6e, Supplementary Fig. 7b).

We test the consequences of the proposal that noise correlations are shaped by contextual priors in a modified setting. We argued that stimulus-specific noise correlations arise due to top-down feedback that carries information about high-level inferences. Consequently, removal of high-level structure is expected to result in reduced stimulus-specificity of noise correlations in Z1. Both our earlier analyses (Figs. 4, 5) and electrophysiology data49 support the idea that texture-statistics related information is delivered to Z1 through top-down feedback from Z2. The former analysis concerned top-down induced changes in response mean in Z1 neurons and here we extend this to top-down influences on noise correlations. To test this, we used the same stimulus manipulations that we used for exploring the properties of Z1 and Z2 representations: phase and filter scrambling of natural stimuli (Methods). We calculated the dissimilarity of noise correlation matrices for natural images and for phase- and filter-scrambled versions of the same natural images (Methods). We found reduced dissimilarity for phase scrambled versions of natural images and also for filter scrambled versions (Fig. 6f). Similar reduction in the dissimilarity of noise correlations for phase- and filter-scrambled versions of natural images was found in the V1 of macaques34 (Fig. 6g). Note, that larger magnitude of dissimilarity, i.e. higher stimulus specificity of noise correlation, in the model is a direct consequence of focusing on quantifying correlated variability and removing private variability from analyses. Sampling the posterior of Z1 reduces the measured stimulus specificity of noise correlations (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d), making the magnitude comparable to the experimentally obtained values. The exact level of reduction depends on the details of how sampling is performed, as well as experiment details, including trial length. Given the 400-ms time window of the experiments in34, we have explored a number of variants in sampling (Supplementary Fig. 7c,d). While systematic changes were introduced by the relative number of samples from Z1 and Z2, relative differences of correlation dissimilarities across stimulus types were consistent. In summary, similar stimulus statistics dependence of noise correlations in Z1 of TDVAE and V1 of macaques provide support that contextual priors emerge as a consequence of hierarchical inference.

Discussion

In this paper we extended deep learning models of the ventral stream by developing a deep generative model. The developed TDVAE model departs from the feed-forward architectures of earlier deep learning accounts as it naturally accommodates top-down interactions: top-down connections serve the implementation of contextual priors for hierarchical inference. Importantly, to investigate how neural representations emerge and shape computations, our normative model was end-to-end trained on natural images alone and neural representations could be studied in a setting where no free parameters were available. The hierarchical organization of TDVAE showed strong alignment with the early hierarchy of the ventral stream of the visual cortex: linear features of Z1 reflected simple cell characteristics of V1, while the texture representation in Z2 closely matched texture sensitivities of V2 neurons in primates and rodents. The match between the hierarchy of representations made it possible to investigate top-down computations. Our deep generative model was shown to reproduce key experimental signatures of top-down computations. Importantly, studying the computations in TDVAE enabled us to gauge how feed-forward and top-down contributions interact in V1, predicting changes both in response intensities of individual neurons and in stimulus-dependent changes in noise correlations. Beyond reproducing a wide range of experimental findings, we demonstrate that the framework opens a new window on exploring the representation, computations, and the circuitry of the early visual system.

Generative models have long been implicated in perceptual processes as these establish an essential framework for learning in an unsupervised manner. Conceptually, generative models summarize our knowledge about the world and describe the way observations are produced as a result of the interactions between (a hierarchical set of) features. Perception is assumed to invert the generative process by inferring the features that underlie observations9,24. However, modeling tools to investigate neural processes have been limited. Significant contributions to understanding the computations in the visual cortex were made with non-hierarchical, linear models29, manually designed hierarchical extensions53,54 and linear hierarchical models55,56. Non-hierarchical extension of the linear models were shown to account for extra-classical receptive field effects and response variability37,38,53,57. Further, a mild hierarchical extension that explicitly modeled dependencies between features represented by receptive fields in natural images58, when applied to V1, could account for complex cell properties52. Here we propose to overcome the obstacle of training models that are both hierarchical and flexible enough to accommodate the complexity of natural images by recruiting the recently developed Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) from machine learning25,26 and extending these towards hierarchical computations27,28. Non-hierarchical versions of VAE have previously been applied to various stages of the ventral stream, including early visual cortex30,59 and inferotempral cortex60. Interestingly, a hierarchical VAE proved useful for modeling computations along the dorsal stream61 and could establish relationships to responses in MT but top-down computations were not addressed.

The proposed TDVAE architecture relies on a limited set of assumptions while remaining as faithful as possible to the principles of probabilistic inference. In order to stick with the guarantees of VAEs, we did not rely on extensions of the framework that encourage disentanglement60,62, regularization methods that might distort the learned representations (see Methods), or methods that help limiting the number of learned parameters (convolution). TDVAE implements an approximate form of probabilistic inference, which we related to neural response statistics through the sampling hypothesis. A range of studies delivered support that stochastic sampling accounts for patterns in response variability in V1 and beyond7,12,37,38,63,64,65,66,67. In our study we obtained samples from the variational posterior of the recognition model and performed this sampling with a fixed neural architecture, yielding the so-called amortized inference. Alternatively, inference can be performed by directly sampling the learned generative model. We performed such analysis to validate the recognition model but relied on sampling the recognition model throughout the paper. We motivate the chosen approach by three arguments. First, while the two methods yield the same posterior in a well-calibrated model, the variational posterior provides a useful tool for disentangling the contribution of top-down influences to both response means and response correlations. This feature was particularly effective when interpreting stimulus-dependent modulations of noise correlations. Second, by keeping our approach as close as possible to standard machine learning approaches, the framework can be naturally extended in further directions. Third, we found the circuitry implied by the recognition model to be a good inspiration for interpreting layer-by-layer computations. In our study, TDVAE was directly used to model neural responses. Earlier studies using generative models of natural images have distinguished real-valued responses that were used to model membrane potentials and firing-rate transformed outputs to model spiking activity37,38. A Poisson-distributed version of VAE is an appealing variant to model spiking activity59 but modeling stimulus-dependent changes in noise correlations needs careful evaluation of private variability of model neurons as this affects quantitative fits to neural data68.

How neural circuits implement these computations is a critical question. The presented model provides a computational / algorithmic level account of the processes taking place in the early visual cortex. The approach is computational in the sense that it provides a normative account of how the connections from V2 to V1 need to be organized in order to perform hierarchical inference. It is algorithmic in the sense that sampling is assumed to perform inference. The choice of Variational Autoencoders to approximate inference is not considered to be essential but we propose it to be a convenient platform for the investigation of complex computations59,60. However, the approach hinders some circuit-level motivations, which can be addressed in an implementation-level model67,69. Such an approach has demonstrated that the combination of amortized inference and sampling to perform inference can provide insights into the recurrent interactions within the lateral structure of V167,70 but a version that could perform hierarchical computations has not been explored so far.

The deep generative modeling approach presented here complements the more traditional works on generative models of vision that directly rely on statistical insights to construct the neuronal circuitry57,71. While the multi-layer perceptron networks that implement the computational components of the recognition and generative models in TDVAE are endowed with the flexibility necessary for high-complexity models, these prevent obtaining direct mechanistic insights that more traditional approaches offer71. These mechanistic insights might help to establish inductive biases for deep generative models for more efficient learning of natural image statistics72. Note that the information that reaches Z1 through the top-down influences of Z2 are not implemented in a recurrent loop, instead, the feed-forward pathway that is shared between Z1 and Z2 is relaying information to Z2 before feeding it to Z1. This single-step top-down pass avoids highly recurrent refinement of the responses between V1 and V2. Experiments relying on time delays between neural responses in V1 and V2 are compatible with our account but more precise experimental data can identify more elaborate recurrent computations.

Top-down interactions have previously been implicated in an alternative computational framework to our deep generative models, predictive coding73,74. The two frameworks have strong parallels: both are unsupervised, rely on a generative model, and are hierarchical. The two frameworks can be distinguished based on the goal top-down connections serve. While in our account, top-down interactions contribute to rich inferences that can serve flexible task execution10,21, in the predictive coding framework top-down connections serve an efficient representation of the stimuli75. In our framework inference is inherently probabilistic. Probabilistic inference augments classical inference frameworks by representing the uncertainty associated with the interpretation of the incoming stimuli12,76. Theoretical arguments provide strong support for probabilistic inference and have also gained strong empirical support from behavioral studies11,77. More importantly, the representation of uncertainty has been identified in neuronal responses in V176 and such probabilistic computations have explained a wide range of phenomena37,38,63,67. Representation of uncertainty is not part of the existing formulations of predictive coding models (inference is performed at the maximum a posteriori level78), albeit proposals have been made to extend the original framework of predictive coding in this direction79. In practice, our results on stimulus-dependent correlations are tightly linked to a probabilistic representation and are therefore beyond the scope of predictive coding accounts.

In our hierarchical model, the computational graph of the recognition model provides insights into the potential circuitry serving the computations (Fig. 1). Feed-forward information reaching Z2 passed through a relay that precedes the Z1 layer. Neurons implementing this relay may correspond to layer 4 neurons in V1. Feedback from Z2 can be interpreted as projections to the infragranular layers of V1, which is supported both by anatomical data43 and the progression of texture information across laminae49. Recent experiments have highlighted that so-called feedback receptive fields in layer 2/3 are inherited through top-down interactions, and these are specific to layer 2/3 but are absent from layer 480,81. In line with this, we found that Z1 could inherit specific information from Z2 as texture sensitivity was affected by the integrity of top-down feedback. Layer 2/3 of V1 is well positioned to integrate feed-forward and top-down information, consequently we propose to identify Z1 with this layer. As texture was shown to be represented in V2, and evidence supports that texture-related information reaches V1 with delay49, this result also confirms that the feedback from Z2 to Z1 in TDVAE corresponds to across-area rather than within-area computations. It is important to note that feed-forward information flow towards Z2 is not implemented through Z1. While feed-forward projections from V1 have been identified from layer 4 neurons41, layer 2/3 provides a strong source of feed-forward information flow40. In our paper we did not consider how the V1 code is read by downstream areas for computational purposes, in which layer 2/3 projections certainly have a central role. Interestingly, such a feed-forward component would contribute to a more direct recurrent loop between V1 and V2, which could enrich computations. Note, that the neural networks that implemented the components of TDVAE (Z1-ff, Z2-ff, Z1-INT, Z1-TD) were considered as general computation elements. Therefore we made no attempts to link constituent neurons to the neurons of the ventral stream but this can be an inviting subject of future research.

While our model did not include explicit feedback loops, these are ubiquitous in the cortex. Such recurrent interactions have been investigated through generative models of natural images in the context of modeling collective modulations of neuronal responses by stimulus contrast, which were shown to contribute to nonlinear response properties of V1 neurons38,53,57. Interestingly, this neurally well-motivated generative model has recently been shown to extend and improve the variational autoencoder framework72, which can also be integrated in the future with the hierarchical VAE framework discussed here. Another role of recurrence has been proposed for performing fast and accurate inference in generative models of natural images by neural networks67. Recurrent computations have gained traction in deep discriminative models too and were shown to surpass purely feed-forward models in prediction of neural activity82. More specifically, recurrence was shown to contribute to such predictions when stimuli were perceptually challenging5. This result is in line with our argument that recurrent activity helps under perceptual uncertainty. Indeed, in human MEG recordings, contribution of recurrent computations was shown to be important when processing occlusion, another source of perceptual uncertainty83. This provides an insight that beyond the uncertainty arising through the hierarchical structure of natural images, uncertainty arising from the interactions of different visual elements might rely on recurrent instead of top-down computations. Generative models that combine hierarchical as well as lateral interactions have been proposed in machine learning84, which can provide inspirations for further extensions.

We emphasized the role of top-down interactions in inferring perceptual variables through establishing contextual priors. Importantly, priors that are not dependent on a context can be efficiently implemented without the need of top-down connections85,86,87. The advantage of top-down induced priors is their flexibility as these can depend on the wider context and such can depend on the stimulus itself. In contrast with the implication of top-down connections in perceptual inference, a wide array of studies consider attentional modulation as an important factor contributing to top-down interactions88. Reconciling these alternative interpretations is a critical challenge. We argue that considering task-relevant variables besides perceptual variables can be interpreted in the same inference framework66. Indeed, top-down delivered information in the early visual cortex was shown to be specific to the task being performed in humans89 and also has signatures in mice90. Also, it has been argued that attentional effects can rely on a similar computational scheme, in particular hierarchical inference, to that proposed here for perceptual inference64,91. Interestingly, the top-down modulation of noise correlation patterns has also been demonstrated under changing task conditions92. The question how perceptual and task-related variables are integrated in the circuitry that establishes top-down interactions remains a largely open question but recent studies indicate that they may share the same communication pathways93.

We argued that the emergence of illusions can distinguish goal-directed models from task-independent models that perform probabilistic inference through establishing contextual priors. Indeed, a variety of perceptual illusions have been reported to be at odds with goal-directed models94. Interestingly, modeling works, which had a focus on feedback but not on the cortical representation, highlighted an additional perceptual effect related to the Kanizsa illusion that relied on higher-level shape information95,96. This is in line with reports that cortical areas beyond V2 are central to the Kanizsa effect97. Indeed, higher-level features that are represented beyond V2 could contribute to top-down boosting of illusory responses, but the critical contribution of texture-representing region became evident through the evidence that causal intervention in the lateromedial region of mice eliminated illusory responses98. Hierarchical Bayesian models have been proposed to account for illusory contour responses99,100, which implicate recurrent connections from higher visual areas. While these hand-crafted models can capture the signatures of the Kanizsa experiment, it is an end-to-end trained model that can account for the interplay between the learned representations of a neural network and the computations taking place in them. While illusions are key signatures of the contextual priors that emerge through top-down interactions, these interactions have wider ranging effects. Recently, modulation of V1 neurons by the visual context of their receptive field has received support from a hierarchical inference account54. Disentangling the contributions of feed-forward and feedback components is thus a key challenge of systems neuroscience but novel tools promise to break this impasse by providing a quantitative testbed for theories101.