Abstract

We investigate the two-dimensional motion of a single vortex orbiting a pinned anti-vortex in a unitary Fermi superfluid. By analyzing its trajectory, we measure the yet-unknown longitudinal and transverse mutual friction coefficients, which quantify the vortex-mediated coupling between the normal and superfluid components. Both coefficients increase while approaching the superfluid transition. They provide access to the vortex Hall angle, which is linked to the relaxation time of the localized quasiparticles occupying Andreev bound states within the vortex core, and to the vortex Reynolds number Reα associated with the transition from laminar to quantum turbulent flows. We compare our results with numerical simulations and an analytic model originally formulated for superfluid 3He, finding good agreement. Our work suggests that vortex dynamics in unitary Fermi superfluids is essentially affected by the interplay between delocalized thermal excitations and vortex-bound quasiparticles. Further, it provides a novel testbed for studying vortex dynamics at finite temperatures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The dynamics of quantized vortices exhibit rich behavior that underlies many phenomena across various quantum fluids. These range from the emergence of quantum turbulence in superfluid helium, atomic and polariton condensates1,2,3, and flux resistance in type-II superconductors4, to the decay of persistent currents5,6,7 and glitches in rotating neutron stars8,9,10. In any finite-temperature superfluid system, as vortices move through the normal component, scattering from thermally-excited quasiparticles gives rise to mutual friction forces11. The microscopic mechanisms governing mutual friction hinge on the intrinsic fundamental properties of the system and its excitations.

Vortex dynamics in fermionic superfluids presents an especially complex problem12. Excitations above the superfluid ground state include fermionic quasiparticles—linked to pair-breaking mechanisms—and bosonic collective modes13. In addition, vortices host in-gap Andreev quasiparticles confined inside their cores, which occupy quantized energy levels referred to as Caroli-de Gennes-Matricon (CdGM) states14,15. At temperatures well below the superfluid transition, these bound quasiparticles scatter off delocalized excitations, i.e., the normal fluid. This provides the leading mechanism behind mutual friction in weakly interacting fermionic systems12,13,16—well described by Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) theory. There, the CdGM level spacing ℏω0 is of the order of ∣Δ∣2/EF, where Δ is the superfluid gap and EF is the Fermi energy, whereas their relaxation time τ is determined by quasiparticle scattering, depending on the thermal population of normal excitations above the gap. In both 3He fluids and conventional superconductors where ∣Δ∣ ≪ EF, the CdGM spectrum is dense and the quantized nature of CdGM states becomes obfuscated by fast quasiparticle relaxation, especially at high temperature. On the other hand, high-temperature superconductors feature relatively large gaps, Δ being a significant fraction of EF, and some hints of discrete CdGM levels have been reported17,18. However, the study of free vortex motion in superconducting materials is hampered by pinning to impurities. Experiments have thus far been mostly focused on superfluid 3He, where the observed mutual friction has been attributed to the presence of CdGM states16,19,20,21.

Advances in ultracold atom experiments have opened new avenues for exploring vortex dynamics in the strongly interacting regime of fermionic superfluidity22,23,24. The so-called unitary Fermi gas (UFG) displays the highest critical temperature Tc (normalized to EF) for the superfluid transition of any known fermionic system. It is especially attractive owing to its universal scaling properties, which make it an extraordinary model system for strongly correlated matter. The vortex core size, pair correlations, interparticle spacing, and particle mean free path are indeed governed by a single length scale, namely the inverse Fermi wave vector \({k}_{F}^{-1}\). In the UFG, the large energy gap ∣Δ∣ ≃ 0.47 EF25 leads to ℏω0 ~0.25 EF, restricting in-core bound states to only a handful of discrete levels (Fig. 1a) whose number and thermal population increase with temperature26. In the presence of such sparse CdGM spectrum, the role of vortex-bound quasiparticle scattering in vortex motion is yet unclear.

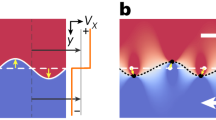

a In Fermi superfluids, the vortex core is populated by localized quasiparticle states (blue wavepackets) characterized by discrete in-gap energies. The energy levels shown in the sketch are calculated using the SLDA for T = 0.7 Tc. The scattering process between in-core localized states and delocalized excitations (red wavepackets), is illustrated as a yellow lightning. b Initial configuration of the single vortex dipole. A vortex appears as a depletion in the atomic density in time-of-flight. The effects of the mutual friction coefficients α and \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) are visualized in the vortex trajectory (continuous spiraling arrow), deviating from the frictionless circular trajectory (dashed circle). c Due to mutual friction, the vortex, with circulation direction indicated by the blue arrow, moves with a velocity vL, forming an angle \(\frac{\pi }{2}-{\Theta }_{H}\) with respect to the superfluid velocity vs. The dotted arrows represent the decomposition of vL into parallel and perpendicular components to vs. d Normalized probability distribution Pv of the vortex initial position, characterized by the standard deviations \({\sigma }_{x}=2.55(3){k}_{F}^{-1}\) and \({\sigma }_{y}=2.06(3)\,{k}_{F}^{-1}\). Continuous and dashed circles represent the estimated size of the vortex core \(\sim 2{k}_{F}^{-1}\), and the imaging resolution \(\sim \)1 μm, respectively.

In this work, we investigate the motion of a single vortex in unitary Fermi gases for temperatures well below the superfluid transition. We engineer a minimal two-vortex configuration, i.e., a vortex dipole, where one vortex orbits around a pinned anti-vortex (Fig. 1b). We describe the mobile vortex trajectories by the dissipative point vortex model (DPVM)27. Here, the scattering of quasiparticles with the vortex line is phenomenologically accounted for by the longitudinal (dissipative) and transverse (reactive) mutual friction coefficients, α and \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\), respectively12,27,28. This analytic model successfully describes vortex motion in various systems, including superfluid 3He19,20, 4He29,30, and atomic superfluids24,31,32,33. We extract α and \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) as functions of temperature by fitting the vortex trajectories, finding that both increase as the superfluid transition is approached. Our results agree with simulations carried out within a time-dependent density functional theory for superfluid Fermi systems, in the formulation commonly referred to as superfluid local density approximation (SLDA)34. They are also well captured by an analytic model for mutual friction developed for superfluid 3He, which accounts for the scattering of bulk excitations with localized quasiparticles occupying Andreev bound states in the vortex core12. This agreement suggests that the analytical description remains applicable even in the presence of a sparse CdGM spectrum. Moreover, from this agreement we infer the presence of CdGM states in the unitary Fermi superfluid. Finally, from the mutual friction coefficients, we determine the vortex Hall angle ΘH (Fig. 1c) and the vortex Reynolds parameter Reα of the unitary Fermi superfluid. These are important markers controlling the vortex Hall effect in superconducting systems35,36 and the onset of quantum turbulence in neutral superfluids37.

Results and Discussion

Experimental protocol

We produce disk-shaped Fermi superfluids with a balanced mixture of the first and third lowest hyperfine states of 6Li atoms below the critical temperature Tc for the superfluid transition, with Np = 2.5(7) × 104 atoms per spin state. Pair interactions, characterized by the s-wave scattering length a, are tuned to the Feshbach resonance located at about 690 G. We focus on the UFG, defined by the interaction parameter 1/kFa ~0. Here kF is the Fermi wave vector, \({k}_{F}=\sqrt{2m{E}_{F}}/\hslash\), determined by the global Fermi energy EF and the mass m of a single lithium atom, and ℏ is the reduced Planck’s constant. The gas is confined in the x − y plane by a cylindrically symmetric hard-wall repulsive potential of radius R = 36.5(5) μm, realized through a digital micromirror device. Along the vertical z-direction, the atoms are instead confined within a tight harmonic trap. The homogeneous density in the x − y plane is n2D = 6.0(16) μm−2 per spin component, while EF/h = 8.4(12) kHz and kF = 3.2(2) μm−1. We control the gas reduced temperature T/TF (where TF = EF/kB is the Fermi temperature and kB is the Boltzmann constant) by following different gas preparation procedures. The value of T/TF is directly measured using a method based on the equation of state similar to Ref. 38. See “Methods” for the sample preparation and temperature determination. We tune \(T/{T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{Trap}}}}}\) in the range 0.3–0.6, where \({T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{Trap}}}}}\simeq 0.18\,{T}_{F}\) for our trapping geometry, as obtained from a fully self-consistent t-matrix approach39 (Supplementary Information).

We prepare the initial vortex configuration by using the chopstick method outlined in Refs. 24,40. In particular, we create a vortex–anti-vortex pair – the two-dimensional analog of a vortex ring30– by translating two μm-sized optical potentials across the superfluid. Both pinning potentials have a Gaussian profile with a 1/e2-width σ = 1.6(2) μm, and intensity V0/EF = 2.7(5). The width σ is of the same order of the expected vortex core size, \({\xi }_{v} \sim 2{k}_{F}^{-1}=0.62(4)\,\mu {{{\rm{m}}}}\)15, and is limited by the resolution of our optical system (\(\sim \) 1 μm). One vortex is positioned at the center of the sample, while the other is dragged at a distance \({r}_{0}=14.3(9)\,\mu {{{\rm{m}}}}=45(6)\,{k}_{F}^{-1}\) (Fig. 1b). Each vortex carries a single quantum of circulation κc = h/2m. We control their initial positions with a precision \(\sim \) 1.1ξv, estimated as the standard deviation of the distribution of vortex initial position over repeated realizations (see Fig. 1d). This aspect is crucial for a reliable reconstruction of vortex trajectories across many independent measurements.

The vortex dynamics is initialized by removing the potential pinning the off-centered vortex. The free vortex follows a spiraling trajectory, influenced by the background superfluid flow generated by the pinned central vortex and boundary conditions, and mutual friction (Fig. 2a–b). The in-plane density homogeneity minimizes the influence of density gradients on vortex motion unlike for harmonically confined gases22,31. Moreover, the strong confinement along the z-direction limits the excitation of Kelvin waves, keeping vortex lines rectilinear, thus making their dynamics effectively two-dimensional (Supplementary Information). This applies only to the geometry of vortex motion, not to the dimensionality of the system’s microscopic excitations or interactions. During the cyclotron motion of the mobile vortex, only sound waves having wavelengths λ ≫ r0 are expected to radiate out of the accelerating vortex41,42, negligibly affecting the observed trajectories.

a Imaging individual vortices at different evolution times. Images are averaged over 2–4 experimental realizations. Curved arrows represent the path of the free, orbiting vortex as a function of time. b Relative position between the vortices for different realizations as a function of time, encoded by their hue. c Time evolution of the standard deviation of the angular position Δθ for the data in (b). Full blue diamonds represent values obtained from the experimental data, empty red circles are obtained from DPVM time evolution. For each evolution time, 1000 independent DPVM time evolutions are performed featuring different initial positions of the mobile vortex within its measured confidence range (see Fig. 1c).

We track vortex trajectories over hundreds of milliseconds (Fig. 2b), performing at least 30 repetitions for each evolution time. Despite the precise initial positioning of the vortices, the angular standard deviation Δθ increases with the evolution time (Fig. 2c). We study this behavior, by analyzing the time evolution of multiple vortex trajectories with the DPVM model, starting from slightly different initial positions, accounting for the experimental uncertainty. The observed agreement between the experimental and numerical evolution of Δθ(t) suggests that the observed spread in the data is fundamentally limited by the intrinsic constraints of manipulating quantum vortices with finite resolution, even though comparable to the core size.

Temperature dependence of the mutual friction

We investigate the effects of thermal excitations on vortex dynamics by performing measurements at different temperatures, within the range 0.3–0.6 Tc. In Fig. 3a, b, we present two typical experimental trajectories for \(T/{T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{Trap}}}}}=0.37(4)\) and \(T/{T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{Trap}}}}}=0.49(6)\). In general, we observe that at higher temperatures the trajectories exhibit more pronounced deviations from circular motion. To extract the mutual friction coefficients, we fit the experimental trajectories using the equation of motion of the mobile vortex of the DPVM, assuming the normal component remains stationary in the laboratory frame31,33,43 (see “Methods” and Supplementary Figs. S.1 and S.2 for details). The values of α are obtained from the time-evolution of the radial coordinate r, while those of \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) are extracted from the temporal lag of the azimuthal coordinate θ. Both coefficients increase with temperature (Fig. 3c, d), reflecting the increasing normal component. Interestingly, \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) remains finite over the entire temperature range explored, in contrast to previous experiments and theories for atomic bosonic superfluids, where it was considered to be negligible28,44. At the same time, the measured values of α are much higher than those reported for a weakly-interacting BEC over a comparable temperature range, where the maximum value was found to be α ≃ 0.03 at T ≃ 0.8 Tc31. In that case, the dominant contribution to mutual friction was believed to arise from the scattering of collective excitations (phonons) by the vortex velocity field. The higher sound speed in Fermi superfluids25, instead, leads to an energetic suppression of Bogoliubov-Anderson phonon excitations, potentially reducing their role in mutual friction. However, their contribution is yet to be theoretically determined45,46. Furthermore, the measured dissipative coefficient α exhibits an intermediate trend between those measured in 3He16 and 4He47 fluids (see Supplementary Fig. S.3). This behaviour fits in with the values measured at low temperatures when moving from the BEC towards the BCS regime24, being compatible with an increasing number of CdGM states due to the exponential gap reduction in BCS superfluids.

Observed vortex trajectories (a) decomposed on the radial [(b)-i] and azimuthal [(b)-ii] coordinates over time for different temperatures: \(T/{T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{Trap}}}}}=0.37(4)\) (blue) and \(T/{T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{Trap}}}}}=0.49(6)\) (red). Data points represent the average angular and radial position of the vortex, error bars are standard deviation of the mean. Solid curves represent fits of the experimental trajectories using the DPVM. The dashed circumference [in (a)] shows the frictionless vortex trajectory. Measured mutual friction coefficients: (c) α and (d) \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) as a function of temperature. Experimental data are shown as blue diamonds, vertical error bars correspond to the fitting error of the trajectories, horizontal error bars correspond to the uncertainty in the temperature determination. The green triangle shows the value of α obtained in Ref. 24. Red open circles are obtained from the time-dependent SLDA simulations for kFr0 = 31, normalized by the SLDA critical temperature \({T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{SLDA}}}}}\) = 0.305. The blue curves correspond to Eq. (1) and (2) using ρs/ρ, Δ/Δ(T = 0), and ℏω0 = ∣Δ∣2/EF from SLDA, and \({T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{Homo}}}}}\simeq 0.17\,{T}_{F}\) (homogeneous case). The inset shows the estimated normal component extracted from Eq. (2), with the solid red line representing ρn/ρ from SLDA.

We carry out numerical simulations using the time-dependent SLDA, a fully microscopic approach that is formally equivalent to the mean-field Bogoliubov-de Gennes equations for Fermi systems (see “Methods”). This method has been previously shown to provide a quantitative description of dissipative vortex dynamics in Fermi superfluids26,34. We apply the same DPVM model fitting protocol to analyze the SLDA-simulated vortex trajectories (see Supplementary Fig. S.4), extracting predictions for α and \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) shown in Fig. 3c, d. We considered a vortex dipole size kFr0 = 31 fulfilling the condition of isolated vortex dynamics for the range of temperatures explored experimentally (see Supplementary Figs. S.5–S.8). The SLDA simulations accurately reproduce the experimental values of α, while capturing the qualitative trend of \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\). As expected, at low temperatures, both coefficients approach zero, reflecting the vanishing population of the normal component. Similar to the experimental case, for T > 0.3 Tc, \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) remains finite and exceeds α.

To connect our results with the microscopic mechanisms underlying the mutual friction in fermionic superfluids, we compare them with the analytical predictions developed by Kopnin for describing mutual friction in 3He and weakly coupled BCS systems12,21. This approach describes mutual friction as originating solely from the scattering of quasiparticles occupying CdGM bound states with delocalized excitations12,21. For the transverse force, it recovers the Iordanskii force as well as the so-called anomalous contribution to the transverse cross section due to the mixed particle-hole nature of BCS quasiparticles12. Both contributions can be alternatively derived from the Aharonov-Bohm effect for BCS quasiparticles probing the relative phase change of 2π when encircling the vortex, highlighting the mainly topological nature of the transverse force12,13,21. The mutual friction coefficients take the form:

where ρ = ρs + ρn is the total density, ρs/ρ is the superfluid fraction, and \(\tau=A\frac{\rho }{{\rho }_{n}}{\tau }_{n}\), with \({\tau }_{n} \sim {E}_{F}/{({k}_{B}{T}_{c})}^{2}\) being the Fermi-liquid relaxation rate in the normal state at the critical temperature12,21, and A \(\sim \) 1 a proportionality coefficient (see “Methods”). In particular, the dissipative parameter α is proportional to the scattering rate Γ\(\sim \) τ−1 of quasiparticles confined within the vortex core with delocalized excitations, compatible with an increasing momentum exchange between the normal and superfluid components as scattering events become more frequent. Conversely, the reactive \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) depends only on the properties of the bulk superfluid.

Remarkably, as shown in Fig. 3c, d, this analytic approach closely reproduces the observed behaviour of both α and \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) using a single fitting parameter A\(\sim \) 0.4. The agreement between the experimental data and Kopnin’s prediction suggests that CdGM states play a key role in the emergence of mutual friction in unitary Fermi superfluids. The remaining discrepancy may stem from the finite number and nonlinear spectrum of CdGM levels at unitarity, deviating from the weakly interacting BCS limit considered within Kopnin’s model (see Supplementary Fig. S.9). Additional contributions from in-bound scattering events within the vortex core could further enhance mutual friction48, yielding small yet non-zero dissipation even for T → 049. Additional effects emerging from the non-homogeneity of the gas along the z axis may also contribute to the observed discrepancy (see Supplementary Fig. S.10). Notably, Kopnin’s model, despite being originally formulated for a different interaction regime, quantitatively reproduces also the behavior observed in SLDA simulations (see “Methods”), provided that appropriate inputs are used for Δ(T = 0), Tc and ρs/ρ and Δ/Δ(T = 0) as a function of T/Tc. The deviation seen for \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) in Fig. 3, between both theoretical models, can be traced back to the overestimation of \({T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{SLDA}}}}}\simeq 0.3\,{T}_{F}\) in the SLDA, compared to the experimentally determined value of \({T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{Homo}}}}}=0.17(1)\,{T}_{F}\) for a homogeneous system25. From Eq. (2), we estimate the normal fraction ρn/ρ, and find it follows a consistently increasing behavior with temperature. We find somewhat higher values with respect to recent experimental results50, that possibly originate from the non-homogeneity of the gas along the vortex line axis. However, we remark that measuring ρn at low temperatures remains a challenge51.

The relative strength between transverse and longitudinal components of the mutual friction force offers a clear geometric description of vortex motion, which mirrors charge transport in electric and magnetic fields. In ordinary metals, deviations from a pure cyclotron orbit are characterized by the Hall angle, proportional to the ratio between the transverse (Hall–reactive) and the longitudinal (Ohmic–dissipative) conductivities. Analogously, the vortex Hall angle \({\Theta }_{H}={\tan }^{-1}\left((1-{\alpha }^{{\prime} })/\alpha \right)\)35,36 describes how a vortex moves with respect to the background superfluid velocity field vs. As temperature increases and mutual friction becomes more significant, the direction of the vortex velocity vL shifts relative to vs. This results in ΘH deviating from π/2, its value in the absence of dissipation, corresponding to the vortex moving together with the superfluid velocity (see Fig. 4a and Fig. 1c). The measurement of ΘH provides important insights into the properties of quasiparticles localized within the vortex core. In Kopnin’s approximation where the mutual friction is entirely determined by the interaction of vortex bound states with delocalized quasiparticles above gap, the vortex Hall angle is directly related to the scattering time of the localized quasiparticles τ and ℏω0 through the relation \(\tan {\Theta }_{H}={\omega }_{0}\tau\). Fixing ℏω0 = ∣Δ∣2/EF, we can obtain a reasonable estimate of τ (Fig. 4a)21. Interestingly, we observe that τ increases with decreasing temperature, while remaining significantly shorter than the timescale of vortex dynamics. This ensures that the observed trajectories reflect a steady equilibrium of scattering events. In addition, the measured values of ω0τ suggest that, for unitary superfluids, the broadening of the CdGM energy levels, δECdGM \(\sim \) τ−1, is small with respect to level separation \(\sim \) ℏω0 in the explored temperature range. Analogously to ultraclean superconductors36, these results open prospects for directly probing discrete CdGM states using spectroscopic techniques.

a The vortex Hall angle \({\Theta }_{H}={\tan }^{-1}\left((1-{\alpha }^{{\prime} })/\alpha \right)\) as a function of temperature, determining the deviation of the vortex velocity from the normal to the background superfluid velocity. The inset shows the estimated relaxation time τ of localized quasiparticle, normalized to the Fermi time tF = h/EF = 0.12(2) ms, determined from \(\tan {\Theta }_{H}={\omega }_{0}\tau\) by fixing ℏω0 = ∣Δ∣2/EF. b Vortex Reynolds number \({{\mbox{Re}}}_{\alpha }=(1-{\alpha }^{{\prime} })/\alpha\) as a function of temperature. The shaded gray region defines the estimated transition temperature to the laminar regime, Reα ~1. Specifically, it marks the regime of temperatures providing a value of Reα between 0.5 and 2 according to Kopnin formula Reα = ω0τ (blue line). Color code is defined in Fig. 3c–d. The error bars are obtained from the propagation of uncertainties in the quantities α and \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\).

Even though our experiments are performed in a system containing two vortices, they provide an inroad into regimes of superfluid turbulence, through the intrinsic vortex Reynolds number defined as \({{\mbox{Re}}}_{\alpha }=(1-{\alpha }^{{\prime} })/\alpha\). This velocity-independent marker is fundamental to characterize the transition from laminar to turbulent flow in superfluids2,37, as it parametrizes the crossover from Kelvin waves free to propagate along the axis of a vortex filament (Reα > 1) to overdamped Kelvin waves (Reα < 1)29,37,52,53,54. The damping of these excitations is tightly connected to the rate of momentum exchange between the normal and superfluid components, owing to Reα = ω0τ. For slow rates, Γ ≪ ω0 or Reα ≫ 1, the system is unable to dissipate vortex excitations, cascading into chaotic vortex dynamics, and allowing for quantum turbulence to develop. On the other hand, when the relaxation is efficient, Γ ≳ ω0 or Reα ≲ 1, Kelvin waves relax keeping vortices rectilinear, resulting in mutual-friction-dominated regime37. The description of quantum turbulence relies additionally on the (extrinsic) superfluid Reynolds number, Res = uL/κc, where u and L denote the characteristic velocity and length scales of the superflow2,37,53. As long as Reα ≳ 1, the superflow becomes turbulent only for Res ≫ 1, while it remains laminar whenever Res \(\sim \) 137,53. Within the temperature range explored in this work, we find Reα \(\sim \) 10−40 (Fig. 4b). Thus, although our two-vortex system lies well inside the laminar regime with Res ≃ 1 (u ≃ κc/r and L ≃ r), our results suggest that the UFG is suitable to the study of quantum turbulence in many-vortex systems featuring Res ≫ 155,56. Following Kopnin’s prediction, we estimate that near the superfluid transition, T \(\sim \) 0.9 Tc, the condition Reα ≲ 1 is fulfilled, leading to a regime where the flow is inherently laminar independently on the vortex number53.This is an intermediate scenario compared with 4He and 3He superfluids28,37,49,57 (see Supplementary Information). In 3He-B (at 10 bar) this crossover is observed for lower values of T/Tc16, due to the much larger value of α—an outcome of the much denser spectrum of CdGM bound states, ℏω0 \(\sim \) 10−4EF.

In summary, we have measured the longitudinal and transverse mutual friction coefficients in the unitary Fermi superfluid at finite temperatures. By comparing our results with numerical SLDA simulations and analytical predictions developed for BCS superfluids, we find consistent indications of the essential role played by localized Andreev bound states in the dissipative dynamics of quantum vortices. The large Hall angles observed across the investigated temperature range suggest that the UFG operates in the ultraclean-core limit, where the discrete nature of core-bound states becomes pronounced. In this regime, which has been difficult to achieve in other Fermi systems12,36, vortices exhibit low-viscosity dynamics.

In the future, we plan to investigate other superfluid regimes within the BEC-BCS crossover. Exploring the BEC regime will provide quantitative insights into mutual friction mechanisms that remain uncharacterized, particularly concerning \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\), linking to the unsolved problem surrounding the Iordanskii force in bosonic superfluids28. Conversely, in the BCS regime, CdGM states are expected to have an even stronger influence26,58, leading to enhanced dissipation19,24 and the emergence of a non-negligible vortex inertial mass59. The ability to precisely track vortex motion will allow the study of disordered phase structures in BCS spin-imbalanced systems60. Moreover, the latter scenario represents a unique system offering key insights into the polarization dependence of mutual friction coefficients. This dependence stems from modifications of the CdGM spectrum in spin-imbalanced vortex cores61. Finally, our single-vortex pinning protocol paves the way for highly controlled investigations of the mechanisms behind vortex pinning62, particularly its stability against thermal fluctuations63 and sound waves50,64. In the limit of many vortices, this will enable the study of vortex depinning avalanches, which are thought to underlie neutron stars glitches65.

Methods

Superfluid sample preparation

We prepare the unitary superfluid by evaporating a balanced mixture of the hyperfine states \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle=\left\vert F,{m}_{F}\right\rangle=\left\vert 1/2,1/2\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert 3\right\rangle=\left\vert F,{m}_{F}\right\rangle=\left\vert 3/2,-3/2\right\rangle\) of 6Li, near their scattering Feshbach resonance at 690 G66 in an elongated, elliptic optical dipole trap. A repulsive TEM01-like optical potential at 532 nm is then adiabatically ramped up in 100 ms before the end of the evaporation to provide strong vertical confinement, with trapping frequency ωz = 2π × 560(5) or 640(5) Hz. Successively, in the x-y plane, a box-like potential is turned on to trap the resulting sample in a circular region. This circular box is projected using a Digital Micromirror Device (DMD). When both potentials have reached their final configuration, the infrared lasers forming the crossed dipole trap are adiabatically turned off, completing the transfer into the final pancake trap. A residual radial harmonic potential of 2.5 Hz is present due to the combined effect of an anti-confinement provided by the TEM01 laser beam in the horizontal plane and the confining curvature of the magnetic field used to tune the Feshbach field. This weak confinement has a negligible effect on the sample over the R = 36.5(5) μm radius of our box trap, resulting in an essentially homogeneous density. We estimate the Fermi energy as67 :

Temperature estimation

To measure the temperature of our system, we adopt a similar protocol as in38. We probe the equation of state of the UFG by shining an optically homogeneous potential at the center of the cloud with the DMD (see Fig. 5).

Measured density in the region where the optical potential is applied as a function of its intensity (green points), and fitted curve using Eq. (6) (continuous line). The insets show the observed profile at different values of the external potential. The empty black squares indicate the observed density outside the applied potential.

The vertical confinement provided by the TEM01 laser beam is such that EF/ℏωz ≈ 15, making the system collisionally three dimensional. This allows us to use the 3D density distribution of a unitary Fermi gas written in the local density approximation:

where β = 1/(kBT) and \({\lambda }_{DB}=\sqrt{2\pi {\hslash }^{2}/m{k}_{B}T}\) is the thermal de Broglie wavelength, m the mass of a 6Li atom, \(V({{{\bf{r}}}})=\frac{1}{2}m{\omega }_{z}^{2}{z}^{2}+{U}_{box}(r,\theta )\) the confining potential, and the equation of state fn(q) defined as68:

where F(q) = n(q)/n0(q) is the ratio between the unitary and the non-interacting Fermi gas density measured experimentally in ref. 69 and Li3/2(x) is the polylogarithm of order 3/2 and argument x. The column density measured during the imaging process is:

To extract the temperature and chemical potential, we fit the measured column density nc(μ − V, T) in the region where the optical potential is applied using Eq. (6) for different values of V, where V is the height of the barrier. The height of the step is tuned by changing the arrangement of the mirrors of the DMD to achieve different reflection intensities, I, which translated to the optical potential V = ζI, where ζ is a calibration constant. To obtain the ratio T/TF, we use the fitting result of Eq. (6) for the temperature T and the expected Fermi temperature TF given by the atomic density. Moreover, the chemical potential μ and the calibration constant ζ are obtained by performing the fitting with Eq. (6) similarly to38. We note that the value of the calibration constant is comparable to that measured following the method highlighted in ref. 70.

As shown by the black points in Fig. 5, the outer density is not affected by the application of the external potential, confirming that the cloud is not dramatically perturbed by its application. For most of the experimental realizations, the thermometry procedure was performed before and after the vortex dynamics experiment. In this case, the temperature value is determined as the average of the two independent measurements, and the associated uncertainties is obtained through error propagation or, if greater, by taking the maximum deviation between the results of the two independent measures. We tune the value of T/TF of the cloud by transferring the atoms into the final trap with varying depths, at the end of the evaporation process and loading the atoms in the final configuration using a lower or higher initial trapping potential, subsequently set to the values of interest.

Dissipative point vortex model

The effect of dissipation on the vortex dynamics can be introduced in the context of the two-fluid model as the effect induced by mutual friction within the normal and superfluid components71. According to the two-fluid model, the total density is ρ = ρs + ρn, where ρs and ρn are the density of the superfluid and normal components, respectively. In the description of the dynamics of the vortex, with vs and vn we refer to the background superfluid and normal velocities, namely the velocities of the superfluid and normal components, respectively, in the absence of the vortex.

In our configuration, the motion of the vortex is expected to be determined by the mutual friction force per unit length FN in the superfluid region in proximity to the vortex core, caused by scattering of thermal quasiparticles. In a homogeneous system, for a vortex moving in the \(\hat{{{{\bf{x}}}}}-\hat{{{{\bf{y}}}}}\) plane, this can be written in the form12,71:

where D and \({D}^{{\prime} }\) are dissipative and reactive coefficients quantifying the longitudinal and transverse force per unit length, respectively, vL is the vortex velocity and \(\hat{{{{\bf{z}}}}}\) is the unit vector orthogonal to the plane of vortex motion. The dynamics of a vortex sets a change of momentum in the superfluid flow. For massless vortices, the momentum balance sets71:

where \({{{{\bf{F}}}}}_{M}={\kappa }_{c}{\rho }_{s}({{{{\bf{v}}}}}_{s}-{{{{\bf{v}}}}}_{L})\times \hat{{{{\bf{z}}}}}\) is the Magnus force.

From Eq. (8) it is possible to write the vortex velocity in terms of two mutual friction coefficients α and \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\), associated with dissipative and reactive terms, respectively12. For two-dimensional vortex dynamics, the velocity of the vortex \({{{{\bf{v}}}}}_{L}=\frac{d{{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{L}}{dt}\) moving in the \(\hat{{{{\bf{x}}}}}-\hat{{{{\bf{y}}}}}\) plane is described by:

where σ = ± 1 is the circulation sign (σκc = σh/2m). The coefficients α and \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) are related to D and \({D}^{{\prime} }\) by12:

To take into account the effects of the boundaries, we consider the contribution of imaginary vortices located at \({\tilde{{{{\bf{r}}}}}}_{L}=\frac{{R}^{2}}{| {r}_{L}{| }^{2}}{{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{L}\) for the off-center vortex72. The velocity field of the central vortex fulfills the boundary condition.

Assuming that the normal component is at rest, vn = 0, and considering that the central vortex is ideally pinned at the origin, the motion of the satellite vortex is described by:

where \({{{{\bf{v}}}}}_{s}^{0}\) is the superfluid velocity generated by the central pinned vortex and by the imaginary vortex. We note that the assumption vn = 0 can be relaxed, at the expense of providing the solution of the coupled Navier-Stokes equations, or Boltzmann equation, for the normal component, thus obtaining vn. More complex approaches also simulating the normal component such as30,44,73 may provide benchmarks on the effects of the back-reaction of the normal component to the vortex dynamics.

This set of equations can be solved analytically in the case α ≠ 0, yielding:

where W(x) is the Lambert W-Function, which is the inverse function of f(W) = WeW, and (r0, θ0) are the initial coordinates at t = 0. Letting α = 0 leads to the solution:

with a constant angular velocity as a function of time. The choice of σ = ± 1 simply sets the direction of motion of the satellite vortex, clockwise or anticlockwise.

Analytical model of mutual friction for Fermi superfluids

The values of the parameters D and \({D}^{{\prime} }\) can be theoretically predicted from the microscopic theory of the superfluid system and of the scattering processes. This, together with Eq. (10)–(12), set the vortex motion as a macroscopic probe for microscopic processes, thus providing a benchmark for microscopic theories. In Fig. 3, we compare the obtained values of α and \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) with the ones predicted by Kopnin and Volovik12,74 considering the effect of localized quasiparticles in the mutual friction.

The mutual friction coefficients predicted by this model have the following temperature dependence:

where we introduced the superfluid fraction ρs/ρ. We estimate their values considering ℏω0 = ∣Δ∣2/EF, and \(\tau=\frac{1}{A}\frac{\rho }{{\rho }_{n}}{\tau }_{n}\), with A being a phenomenological parameter of the order of 1, and τn is the Fermi-liquid relaxation rate in the normal state at the critical temperature, that we estimate as \({\tau }_{n}={E}_{F}/{T}_{c}^{2}\)12. Let us remark that Eq. (20), already includes the presence of the Iordanskii force21 written as d⊥ = − ρn/ρs = − (1 − ρs)/ρs. In Fig. 6, this term is explicitly shown in comparison with the rest of the curves. Substituting Eqs. (19)–(20) into Eqs. (10)–(11), without any approximations, we get:

Equivalently,

where \(\tilde{\Delta }=| \Delta | /{k}_{B}{T}_{c}\), \(\tilde{T}=T/{T}_{c}\). Notice that depending on the value of Tc/TF, the behavior of α and \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) is expected to change.

Temperature dependence of α (a), \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) (b), d∣∣ (c) and d⊥(d). Color code is the same of Fig. 3c--d. The additional orange line corresponds to the estimation using Kopnin’s model within the SLDA framework. The blue (orange) curve is obtained with A = 0.4 (A = 1.5) for the corresponding critical temperature \({T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{Homo}}}}}=0.17\,{T}_{F}\) (\({T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{SLDA}}}}}=0.3\,{T}_{F}\)). Black line represents the value expected from the Iordanskii force.

As shown in Fig. 6, the SLDA results show good agreement with the predictions of the Kopnin model. We note that the SLDA method does not rely on any assumption about the presence or absence of specific physical effects, such as CdGM states or the Iordanskii force, but instead it incorporates them naturally through the structure of the energy functional and the resulting dynamics. As demonstrated in the Supplementary Information (see Supplementary Figs. S.7 and S.8), CdGM states are clearly present in the SLDA results. Moreover, the value of \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) observed in SLDA simulations is consistent with the presence of the Iordanskii force.

The dissipative coefficient α depends on the parameter A, which can therefore be adjusted to match the experimental data. Moreover, there are no ab initio calculations that may give its exact value. The continuous blue line in Figs. 3 and 4 of the main text is obtained with the value of A = 0.4. Surprisingly, the non-dissipative coefficient \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) is completely locked by the temperature dependence of the superfluid fraction, ρs/ρ, and the gap, Δ. Therefore, there are no fitting parameters for \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\). Moreover, the ratio \((1-{\alpha }^{{\prime} })/\alpha\) can also be calculated without approximations:

The relevance of the mutual friction coefficients is typically assigned according to their relevant scalings. For instance in Bose superfluids28, near T = 0, it is considered that \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) scales as α2. Hence, for small values of α, the effect of the non-dissipative coefficient is considered negligible. This is not necessarily the case for Fermi superfluids. The relative dependence between α and \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) is given by:

Since Fermi superfluids typically operate in the intermediate to super-clean regimes, where ω0τ ≳ 1, even when α is small, \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) could be of the order of unity. Indeed, from the SLDA’s measured values we find \({\alpha }^{{\prime} } \sim {\alpha }^{1.3(1)}\) for the theoretical models shown in Fig. 6, for T > 0.3Tc.

SLDA simulations

The density-functional theory we apply here is formally equivalent to the mean-field Bogoliubov-de Gennes equations34. For static problems, they have the form (ℏ = m = kB = 1)

and describe the Bogoliubov amplitudes \({({u}_{n}({{{\bf{r}}}}),{v}_{n}({{{\bf{r}}}}))}^{T}\) that in turn define densities: normal ρ, anomalous ν and current j

The temperature effects are modeled by introducing the Fermi-Dirac distribution, noted as \({f}_{n}^{\pm }={(1+\exp (\pm {E}_{n}/T))}^{-1}\), when computing densities from the Bogoliubov amplitudes, and the framework becomes formally equivalent to the finite-temperature HFB method75. The time-dependent equations are obtained by changing \({E}_{n}\to i\frac{\partial }{\partial t}\) and allowing all functions to be time-dependent as well.

The Hamiltonian has the generic form

where mean and pairing fields are computed as appropriate functional derivatives of the SLDA functional34. Their explicit forms are:

The functional parameters (\(\hat{\beta }\) and \(\hat{\gamma }\)) are adjusted to ensure the reproduction of the Bertsch parameter ξ ≈ 0.4 and the pairing gap at zero temperature Δ/εF ≈ 0.5 of the uniform unitary Fermi gas, consistent with the quantum Monte Carlo results76. One of the drawbacks of such a defined framework is an overestimation of the critical temperature of the superfluid-to-normal phase transition, which reads Tc ≈ 0.305 TF. In principle, this approximation can be improved by extending the SLDA framework to include temperature-dependent terms in the energy functional, as prescribed by finite-temperature DFT (see, e.g., refs. 77,78), leading to a more accurate prediction of Tc. However, implementing this extension is non-trivial in practice, especially when addressing time-dependent problems. While the present approximation limits the accuracy of absolute temperature predictions, we emphasize that our analysis is performed in terms of the reduced temperature T/Tc, which helps mitigate this limitation in comparisons with experiment. The temperature dependence of the pairing gap, for uniform UFG, is shown in the Fig. 7a. To solve static and time-dependent equations, we have used W-SLDA Toolkit79, and calculations were executed on the LUMI supercomputer (Kajaani, Finland).

We estimated the superfluid fraction from the SLDA simulations using the method based on the response of the system to a phase twist59 and relying on a concept of Landau’s two-fluid model. We assume that the density (29) and current (31) can be decomposed into normal (n) and superfluid (s) parts:

where the superfluid velocity vs is related to the gradient of the phase of the order parameter \({{{{\bf{v}}}}}_{s}({{{\bf{r}}}},t)=\frac{1}{2}\nabla \phi ({{{\bf{r}}}},t)\) (we used M = 2m = 2 for the mass of Cooper pairs in our units). We consider that the normal component is at rest with the system boundaries, vn = 0. Therefore, the total density current j reduces to ρsvs. We can estimate the superfluid fraction in the bulk by computing the ratio:

In the Fig. 7b, we show the extracted superfluid fraction as a function of temperature by considering a uniform system with imposed superfluid flow in one direction. Due to numerical errors estimating ∣ ∇ ϕ∣, at low temperature we observe ρs/ρ exceeding 1 by about 10−2. The obtained values turn out to be well approximated by the phenomenological formula \({\rho }_{s}/\rho={\left(\Delta (T)/\Delta (T=0)\right)}^{3}\).

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available at Zenodo80 and from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Smith, M. R., Donnelly, R. J., Goldenfeld, N. & Vinen, W. F. Decay of vorticity in homogeneous turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 2583 (1993).

Tsatsos, M. C. et al. Quantum turbulence in trapped atomic Bose–Einstein condensates. Phys. Rep. 622, 1 (2016).

Panico, R. et al. Onset of vortex clustering and inverse energy cascade in dissipative quantum fluids. Nat. Phot. 17, 451 (2023).

Huse, D. A., Fisher, M. P. A. & Fisher, D. S. Are superconductors really superconducting? Nature 358, 553 (1992).

Donnelly, R. J. & Barenghi, C. F. The observed properties of liquid helium at the saturated vapor pressure. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 27, 1217 (1998).

Leggett, A. J. et al. Quantum Liquids, Oxford Graduate Texts (Oxford University Press, London, England, 2006).

Halperin, B. I., Refael, G. & Demler, E. Resistance in superconductors. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 24, 4039–4080 (2010).

Anderson, P. W. & Itoh, N. Pulsar glitches and restlessness as a hard superfluidity phenomenon. Nature 256, 25 (1975).

Zhou, S., Gügercinoğlu, E., Yuan, J., Ge, M. & Yu, C. Pulsar glitches: a review. Universe 8, 641 (2022).

Antonelli, M. & Haskell, B. Superfluid vortex-mediated mutual friction in non-homogeneous neutron star interiors. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 499, 3690 (2020).

Hall, H. E. & Vinen, W. F. The rotation of liquid helium II I. experiments on the propagation of second sound in uniformly rotating helium II. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 238, 204–214 (1956).

Kopnin, N. B. Vortex dynamics and mutual friction in superconductors and Fermi superfluids. Rep. Prog. Phys. 65, 1633 (2002).

Edouard, B. Sonin, Dynamics of Quantised Vortices in Superfluids (Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Caroli, C., De Gennes, P. G. & Matricon, J. Bound fermion states on a vortex line in a type II superconductor. Phys. Lett. 9, 307 (1964).

Sensarma, R., Randeria, M. & Ho, Tin-Lun Vortices in superfluid Fermi gases through the BEC to BCS crossover. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 090403 (2006).

Bevan, T. D. C. et al. Momentum creation by vortices in superfluid 3He as a model of primordial baryogenesis. Nature 386, 689 (1997).

Berthod, C., Maggio-Aprile, I., Bruér, J., Erb, A. & Renner, C. Observation of Caroli–de Gennes–Matricon Vortex States in YBa2Cu3O7−δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 237001 (2017).

Chen, M. et al. Discrete energy levels of Caroli-de Gennes-Matricon states in quantum limit in FeTe0.55Se0.45. Nat. Comm. 9, 970 (2018).

Bevan, T. D. C. et al. Vortex mutual friction in superfluid 3 He. J. low. Temp. Phys. 109, 423 (1997).

Mäkinen, J. T. & Eltsov, V. B. Mutual friction in superfluid He-B 3 in the low-temperature regime. Phys. Rev. B 97, 014527 (2018).

Kopnin, N. B. & Salomaa, M. M. Mutual friction in superfluid 3He: effects of bound states in the vortex core. Phys. Rev. B 44, 9667 (1991).

Ku, M. J. H. et al. Motion of a solitonic vortex in the BEC-BCS crossover. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 065301 (2014).

Park, J. W., Ko, B. & Shin, Y.-i. Critical vortex shedding in a strongly interacting fermionic superfluid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 225301 (2018).

Kwon, W. J. et al. Sound emission and annihilations in a programmable quantum vortex collider. Nature 600, 64 (2021).

Bennemann, Karl-Heinz, Ketterson, J. B.Novel Superfluids: Volume 2 (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Barresi, A., Boulet, A., Magierski, P. & Wlazłowski, G. Dissipative dynamics of quantum vortices in fermionic superfluid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 043001 (2023).

Schwarz, K. W. Three-dimensional vortex dynamics in superfluid He 4: Line-line and line-boundary interactions. Phys. Rev. B 31, 5782 (1985).

Sergeev, Y. A. Mutual friction in bosonic superfluids: a review. J. Low. Temp. Phys. 212, 251–305 (2023).

Minowa, Y. et al. Direct excitation of Kelvin waves on quantized vortices. Nat. Phys. 21, 233–238 (2025).

Tang, Y. et al. Imaging quantized vortex rings in superfluid helium to evaluate quantum dissipation. Nat. Commun. 14, 2941 (2023).

Moon, G., Kwon, W. J., Lee, H. & Shin, Y.-i. Thermal friction on quantum vortices in a Bose-Einstein condensate. Phys. Rev. A 92, 051601 (2015).

Kim, JoonHyun, Kwon, WooJin & Shin, Yong-il Role of thermal friction in relaxation of turbulent Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 94, 033612 (2016).

Tyler, W. et al. Melting of a vortex matter Wigner crystal. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.09920 (2024).

Bulgac, A. Local-density-functional theory for superfluid fermionic systems: the unitary gas. Phys. Rev. A 76, 040502 (2007).

Heyl, M. et al. Vortex dynamics in the two-dimensional BCS-BEC crossover. Nat. Commun. 13, 6986 (2022).

Ogawa, R., Nabeshima, F., Nishizaki, T. & Maeda, A. Large Hall angle of vortex motion in high-Tc cuprate superconductors revealed by microwave flux-flow Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 104, L020503 (2021).

Finne, A. P. et al. An intrinsic velocity-independent criterion for superfluid turbulence. Nature 424, 1022 (2003).

Hueck, K. et al. Two-Dimensional Homogeneous Fermi Gases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 060402 (2018).

Pini, M., Pieri, P. & Strinati, G. C. Fermi gas throughout the BCS-BEC crossover: comparative study of t-matrix approaches with various degrees of self-consistency. Phys. Rev. B 99, 094502 (2019).

Samson, E. C. et al. Deterministic creation, pinning, and manipulation of quantized vortices in a Bose-Einstein condensate. Phys. Rev. A 93, 023603 (2016).

Vinen, W. F. Decay of superfluid turbulence at a very low temperature: the radiation of sound from a Kelvin wave on a quantized vortex. Phys. Rev. B 64, 134520 (2001).

Fetter, A. L. & Svidzinsky, A. A. Vortices in a trapped dilute Bose-Einstein condensate. J. Phys.: Condens. matter 13, R135 (2001).

Simjanovski, S., Gauthier, G., Rubinsztein-Dunlop, H., Reeves, M. T. & Neely, T. W. Shear-induced decaying turbulence in Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 111, 023314 (2025).

Jackson, B., Proukakis, N. P., Barenghi, C. F. & Zaremba, E. Finite-temperature vortex dynamics in Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A79, 053615 (2009).

Mozyrsky, D. & Chubukov, A. V. Dynamic properties of superconductors: Anderson-Bogoliubov mode and Berry phase in the BCS and BEC regimes. Phys. Rev. B. 99, 174510 (2019).

Pitaevskii, L. P. Calculation of the phonon part of the mutual friction force in superfluid helium. Sov. Phys. JETP 8, 888 (1959).

Barenghi, C. F., Donnelly, R. J. & Vinen, W. F. Friction on quantized vortices in helium II. A review. J. Low. Temp. Phys. 52, 189 (1983).

Silaev, M. A. Universal mechanism of dissipation in Fermi superfluids at ultralow temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 045303 (2012).

Eltsov, V. B. et al. Quantum turbulence in a propagating superfluid vortex front. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 265301 (2007).

Yan, Z. et al. Thermography of the superfluid transition in a strongly interacting Fermi gas. Science 383, 629 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Second sound attenuation near quantum criticality. Science 375, 528 (2022).

Barenghi, C. F., Donnelly, R. J. & Vinen, W. F. Thermal excitation of waves on quantized vortices. Phys. fluids 28, 498 (1985).

Volovik, G. E. Classical and quantum regimes of superfluid turbulence. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. Lett. 78, 533 (2003).

Mäkinen, J. T. et al. Rotating quantum wave turbulence. Nat. Phys. 19, 898 (2023).

Hossain, K. et al. Rotating quantum turbulence in the unitary Fermi gas. Phys. Rev. A 105, 013304 (2022).

Wlazłowski, G. et al. Fermionic quantum turbulence: Pushing the limits of high-performance computing. PNAS Nexus 3 (2024).

Donnelly, Russell J Quantized vortices in helium II, Vol. 2 (Cambridge University Press, 1991).

Simonucci, S., Pieri, P. & Strinati, G. C. Bound states in a superfluid vortex: A detailed study along the BCS-BEC crossover. Phys. Rev. B 99, 134506 (2019).

Richaud, A. et al. Dynamical signature of vortex mass in Fermi superfluids. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.12417 (2024).

Magierski, P., Barresi, A., Makowski, A., Pecak, D. & Wlazłowski, G. Quantum vortices in fermionic superfluids: from ultracold atoms to neutron stars. Eur. Phys. J. A 60, 186 (2024).

Magierski, P., Wlazłowski, G., Makowski, A. & Kobuszewski, K. Spin-polarized vortices with reversed circulation. Phys. Rev. A 106, 033322 (2022).

Blatter, G., Feigel’man, M. V., Geshkenbein, V. B., Larkin, A. I. & Vinokur, V. M. Vortices in high-temperature superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 66, 1125 (1994).

Fisher, D. S., Fisher, M. P. A. & Huse, D. A. Thermal fluctuations, quenched disorder, phase transitions, and transport in type-II superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 43, 130 (1991).

Patel, P. B. et al. Universal sound diffusion in a strongly interacting Fermi gas. Science 370, 1222 (2020).

Liu, I.-Kang, Baggaley, A. W., Barenghi, C. F. & Wood, T. S. Vortex avalanches and collective motion in neutron stars. Astrophys. J. 984, 83 (2025).

Zürn, G. et al. Precise characterization of 6Li feshbach resonances using trap-sideband-resolved RF spectroscopy of weakly bound molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 135301 (2013).

Hernández-Rajkov, D. et al. Connecting shear flow and vortex array instabilities in annular atomic superfluids. Nat. Phys. 20, 939–944 (2024).

Del Pace, G., Kwon, W. J., Zaccanti, M., Roati, G. & Scazza, F. Tunneling transport of unitary fermions across the superfluid transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 055301 (2021).

Ku, M. J. H. et al. Revealing the superfluid lambda transition in the universal thermodynamics of a unitary Fermi gas. Science 335, 563 (2012).

Kwon, W. J. et al. Strongly correlated superfluid order parameters from dc Josephson supercurrents. Science 369, 84 (2020).

Sonin, E. B. Magnus force in superfluids and superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 55, 485 (1997).

Martikainen, J.-P. et al. Generation and evolution of vortex-antivortex pairs in Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 64, 063602 (2001).

Galantucci, L., Baggaley, A. W., Barenghi, C. F. & Krstulovic, G. A new self-consistent approach of quantum turbulence in superfluid helium. Eur. Phys. J. 135, 1 (2020).

Kopnin, N. B., Volovik, G. E. & Parts, Ü. Spectral flow in vortex dynamics of 3He-B and superconductors. Europhys. Lett. 32, 651 (1995).

Goodman, A. L. Finite-temperature HFB theory. Nucl. Phys. A 352, 30 (1981).

Bulgac, A., Forbes, Michael McNeil, & Magierski, P. The Unitary Fermi Gas: From Monte Carlo to Density Functionals, in The BCS-BEC Crossover and the Unitary Fermi Gas, Lecture Notes in Physics, edited by Zwerger, W. 305–373 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012).

Mermin, N. D. Thermal properties of the Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 137, A1441 (1965).

Eschrig, H. T > 0 ensemble-state density functional theory via Legendre transform. Phys. Rev. B 82, 205120 (2010).

W-SLDA Toolkit, https://wslda.fizyka.pw.edu.pl/ (2024)

Grani, N. et al. Mutual friction and vortex Hall angle in a strongly interacting Fermi superfluid: Supplementary data, Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15084263 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank B. Haskell, M. Antonelli, and S. Autti for the discussions. We thank M. Inguscio, J. Mäkinen and D. Galli for careful reading of the manuscript, and W.J. Kwon for participating in the initial setting of the experiment. G.R., G.D.P., and P.P. acknowledge financial support from the PNRR MUR project PE0000023-NQSTI. G.R. acknowledges funding from the Italian Ministry of University and Research under the PRIN2017 project CEnTraL and the Project CNR-FOE-LENS-2024. The authors acknowledge funding from INFN through the RELAQS project. The authors acknowledge support from the European Union - NextGenerationEU for the “Integrated Infrastructure initiative in Photonics and Quantum Sciences" - I-PHOQS [IR0000016, ID D2B8D520, CUP B53C22001750006]. This publication has received funding under the Horizon Europe program HORIZON-CL4-2022-QUANTUM-02-SGA via project 101113690 (PASQuanS2.1) and by the European Community’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement n∘ 871124. This work was financially supported by the (Polish) National Science Center Grants No. 2022/45/B/ST2/00358 (G.W.) and 2021/43/B/ST2/01191 (P.M.). P.P. acknowledges funding from the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) under project PRIN2022, Contract No. 2022523NA7 and from the European Union - Next Generation EU through MUR project PNRR - M4C2 - I1.4 Contract No. CN00000013. F.S. acknowledges funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant agreement No. 949438). We acknowledge Polish high-performance computing infrastructure PLGrid for awarding this project access to the LUMI supercomputer, owned by the EuroHPC Joint Undertaking, hosted by CSC (Finland) and the LUMI consortium through PLL/2024/07/017603.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.G., D.H.R., and G.R. conceived the study. N.G., D.H.R., and C.D. performed the experiments. N.G., D.H.R., and C.D. analysed the experimental data. D.H.R., G.W., and P.M. carried out the SLDA numerical calculations. P.P. and M.P. carried out the self-consistent t-matrix calculations. N.G., D.H.R., C.D., P.P., M.P., P.M., G.W., M.F.F., F.S., G.D.P. and G.R. contributed to the interpretation of the results and to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grani, N., Hernández-Rajkov, D., Daix, C. et al. Mutual friction and vortex Hall angle in a strongly interacting Fermi superfluid. Nat Commun 16, 10245 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64992-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64992-w