Abstract

Recent emergence and dissemination of plasmid-borne tmexCD1-toprJ1 tigecycline resistance threatens the efficacy of tigecycline as a “last-resort” defense against bacterial infections. Here, we report two cryo-EM structures of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 alone and in complex with its NMP inhibitor, and both are determined at the resolutions of 2.97 Å and 3.0 Å, respectively. The symmetry of overall architecture explains how the tripartite organization adopts a 3:6:3 protomer stoichiometry (TOprJ1: TMexC1: TMexD1) to assemble an elongated, rod-like pump spanning bacterial double membranes. The periplasmic TMexC1 adaptor bind the trimeric TOprJ1 funnel via a universal “tip-to-tip” contact, and bridges the bottom TMexD1 engine by extensive interactions. A unique form of resting (R) states is observed for TMexD1 trimer. Besides two binding-interfaces of TMexC1 with TOprJ1 and TMexD1, we characterize a substrate/inhibitor-loading cavity. Collectively, these findings constitute molecular bases for assembly and inhibition of transferable TMexCD1-TOprJ1 machinery, and benefit developing next-generation of antimicrobials targeting functional efflux pump.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of the top 10 priority threats of global health concern1,2,3,4. Notably, the deaths attributable to AMR rise markedly from 0.7 million in 20141, to 1.27 million in 20195, posing enormous burdens to one health and economy6. Among them, the AMR-causing deaths separately are ~141,000 in the Americas7, and ~250,000 in the WHO African region8. Silent pandemic of AMR that approached during COVID-19 period (2019–2022), largely supports the speculation of Jim O’Neil that annual AMR-attributable deaths are 10 million globally by 20501,9,10. Thus, the next generation of “resistance-proof” antimicrobials is prioritized to combat the complexity of ongoing AMR crisis2,3,11. The broad-spectrum β-lactam antibiotics, carbapenems are clinically introduced to combat against multidrug-resistant (MDR) infections12. Along with the “70-year-old” colistin (polymyxin E, a cyclic polypeptide antibiotic13,14), tigecycline, the 3rd generation tetracycline antibiotic15, is regarded as the few “final-line” options tackling clinical MDR challenges. The prevalence of diverse carbapenem resistance renewed the interest of colistin as a “last-resort” defense13, albeit its nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity14. However, clinical efficacy of colistin is challenged by global dissemination of plasmid-borne mobile colistin resistance (MCR) elements16,17,18,19. This places tigecycline as a sole therapeutic option against bacterial pathogens with MCR colistin resistance20,21.

To some extent, the replacement with tigecycline overcomes certain tetracycline resistance arising from both efflux exporters and ribosome protection15. It seemed likely that clinical use of tigecycline is compromised by recent emergence of two mobile tigecycline resistance machineries21,22,23,24. Namely, they include (i) plasmid-encoded TetX4 in Enterobacteriaceae21,23 plus TetX5 of Acinetobacter21, and (ii) plasmid-borne resistance-nodulation-division (RND) efflux pump, TMexCD1-TOprJ1 in an important ESKAPE-type pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae22. Not only has the TetX4 ancestor, termed TetX(2/4)-P, been determined to arise from the poultry pathogen, a member of Flavobacteriaceae25, but also the additional variant TetX6 is localized to co-exist with MCR-1, a lipid A modifying enzyme on a single plasmid in an epidemic lineage of Escherichia coli26. Consistent with that of the TetX4 progenitor25, all the three transferable oxidoreductases (TetX427 to TetX625) invariantly convert tigecycline antibiotic into 11a-hydroxyltigecycline, promoting tigecycline resistance28. As a member of the ubiquitous RND superfamily of drug exporters, the transmissible TMexCD-TOprJ tripartite efflux pump is assumed to rapidly sense the pool of tigecycline, and efficiently trigger drug extrusion29. This might explain in part (if not all) the kind of transferable tigecycline resistance.

So far, a total of 10 tmexCD-toprJ cluster subtypes (from temxCD1-toprJ122 to tmexCD6-toprJ130, in Fig. S1), have been detected from different bacterial species. This suggests an expanding arsenal of TMexCD-TOprJ efflux pumps that mediates tigecycline resistance. In 2020, the prototype of transferable tmexCD1-toprJ1 operon was identified by two Chinese groups, which is coharbored with an mcr-8 colistin resistance gene on a single plasmid of drug-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates of animal origins22,31. Shortly, this kind of genetic cluster was also detected on an mcr-1-bearing plasmid from a clinical K. pneumoniae strain32. This hints silent epidemic of ESKAPE-type pathogen having reduced susceptibility to two “ultimate-line” antimicrobials tigecycline and colistin. In addition to the IS26 insert sequence that enables the acquisition of tmexCD1-toprJ1 determinant in K. pneumoniae33,34, a growing body of heterogeneous variants has been successively discovered, which included, but not limited to (i) tmexCD2-toprJ2/Raoultella ornithinolytica35, (ii) tmexCD3-toprJ3/K. aerogenes36, and (iii) tmexCD4-toprJ4/K. quasipneumoniae & Enterobacter roggenkampii37. The presence of chromosomal variants revealed that (i) Pseudomonas30,38 and Aeromonas39 act as natural reservoirs for RND-type tigecycline efflux pumps. Subsequently, a large-scale genomic epidemiology revealed the dissemination of mobilized tmexCD-toprJ cluster in clinic sector, and called for timely monitoring in the “one health” framework40. Worrisomely, in addition to MCR-1/822,32, several tmexCD-toprJ subtypes are combined with critical resistance elements (esp. TetX638, KPC-235, NDM-1/436,41), posing a substantial threat to anti-infection therapies.

As the most efficient/effective resistance pathway, drug extrusion proceeds by six families of efflux pumps in a cooperative manner. Unlike the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters that primarily utilize ATP to drive drug transport, all the other five secondary active pumps are powered by electrochemical energy arising from transmembrane ion gradients. Namely, these systems include (i) major facilitator superfamily (MFS), (ii) multidrug and toxin extrusion (MATE) family, (iii) small multidrug resistance (SMR) family, (iv) proteobacterial antimicrobial compound efflux (PACE) family, and (v) resistance nodulation division (RND) superfamily29. The paradigmatic RND-type efflux pump refers to an intrinsic AcrAB-TolC complex of E. coli42,43,44 and its paralog MexAB-OprM system on the P. aeruginosa chromosome45,46. In brief, the tripartite AcrAB-TolC machinery consists of TolC, an outer-membrane factor (OMF) that is connected by a membrane fusion protein (MFP) with an inner-membrane trimeric transporter AcrB42,43,44. In addition to AcrAB-TolC cryo-EM architecture47, the in situ structure and assembly mode of this efflux pump have been proposed, which is largely dependent on observations with electron cryo-tomography. Extensive allosteric alteration is a prerequisite for drug expelling by the RND-type efflux pumps48,49. However, biochemical mechanism by which a transferable TMexCD-ToprJ tripartite machinery confers bacterial tigecycline resistance50, remains poorly understood.

In this study, we aimed to address this missing gap of knowledge by using integrated approaches comprising cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) technology and bacterial genetics. We present the overall cryo-EM structures of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 machinery and its NMP inhibitor-liganded form. The combinational mutations study provides functional insights into the assembly of bipartite and tripartite efflux pump, and its recognition by some substrate/inhibitor. Taken together, these findings expand mechanistic understanding for mobile TMexCD1-TOprJ1 tigecycline resistance, and facilitate the development of distinct lead compounds targeting the resistance reversal.

Results

Genetic description of transferable tmexCD1-toprJ1 cluster

The E. coli ArcAB-TolC and P. aeruginosa MexAB-OprM are two extensively-studied RND-type tripartite efflux pumps, leading to intrinsic resistance to multiple antibiotics3,29. An ever-increasing body of distinct plasmids mediates the transferability of TMexCD-TOprJ machinery across the top priority ESKAPE-type pathogens40. Of the 10 known subtypes (Fig. S1), the “tmexCD1-toprJ1” cluster is a prototypic determinant of mobile tigecycline resistance22. As expected from genetic context analysis, the transferable tmexCD1-toprJ1, which is carried on pHNAH8I plasmid of K. pneumoniae, is organized in a manner similar to the two chromosomally-encoded versions AcrAB-TolC and MexAB-OprM (Fig. 1a). It was reported that tmexCD1-toprJ1 transcription is weakly modulated by a TetR-type regulator TNfxB1 of 185-residue long51, which is equivalent to AcrR and MexR (Fig. S2). However, the only exception lies in that the E. coli tolC locus is separated from its partner acrAB (Fig. 1a). As inferred from phylogeny, diverse tmexCD-toprJ variants identified so far, can be provisionally classified into 10 subclades exemplified with TMexCD1-TOprJ1 (abbreviated from TMexC1D1-TOprJ1, in Fig. 1b). Among them, TMexC3D3-TOprJ1 is a leading subgroup. Two subtypes are second only to TMexC3D3-TOprJ1, including (i) TMexC1D1-TOprJ1, and (ii) TMexC2D2-TOprJ2 (Fig. 1b). With an exception of TMexC6D6-TOprJ1 subclade with 5 members, all the other subtypes are rare variants (Fig. 1b). Namely, they comprised (i) TMexC2D1-TOprJ1, (ii) TMexC6D6-TOprJ1, (iii) TMexC3D5-TOprJ2, (iv) TMexC6D3-TOprJ1, (v) TMexC2D6-TOprJ2, and (vi) TMexC4D4-TOprJ4 (Fig. 1b).

a Genetic context of TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 cluster. The “3-gene” operon encoding an RND-type pump consists of an outer-membrane tunnel TolC/MexM/TOprJ1 (orange), an adapter AcrA/MexA/TMexC1 (magenta), and an inner-membrane transporter AcrB/MexB/TMexD1 (blue). The regulator AcrR/MexR/TNfxB1 is shown in yellow. b Phylogeny of the family of TMexCD-TOprJ variants. c Schematic diagram for the TMexCD1-TOprJ1 tripartite efflux pump. TOprJ1 tunnel is colored orange, TMexC1 adapter is indicated in magenta, and TMexD1 transporter is displayed in blue. d The clinical isolate of K. pneumoniae carrying plasmid-borne TMexCD1-TOprJ1 displays comparable level of bacterial insusceptibility to tigecycline and eravacycline. e Expression of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 enables the recipient E. coli host resistant to tigecycline and eravacycline at a similar level. Three independent experiments were performed and each dot represented an individual MIC determination.

Presumably, the paradigm TMexCD1-TOprJ1 complex functions as a supramolecular tripartite machinery for multidrug expulsion that spans the bacterial periplasm from an inner-membrane to the outer-membrane (Fig. 1c). When aligned with the known OMF, TolC of E. coli, TOprJ1 appears to be a distant ortholog with 19.42% identity (Figs S3-S4). In contrast, TMexC1 is closely-related to AcrA with 45.08% identity (Figs S5-S6). Compared to AcrB/MexB, TMexD1 consistently gives ~48.5% homology (Figs S7-S8). It is of great interest to further examine this assumption. Consistent with a previous statement by Lv and coauthors22, the clinical K. pneumoniae isolate that contains a plasmid-borne tmexCD1-toprJ1 cluster exhibited the tigecycline (or eravacycline) minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 16 μg/ml, which is 128(64)-fold higher than that of negative control, K. pneumoniae lacking the tmexCD1-toprJ1 operon (Fig. 1d). Moreover, an introduction of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 into E. coli significantly increased bacterial resistance of tigecycline (or eravacycline) by around 32-fold (Fig. 1e). Collectively, these data validate the functionality of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 pump, enabling subsequent exploration of “structure-to-mechanism” relationship.

Architecture of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 efflux system

We developed the system of a single plasmid, termed pBAD24::tmexCD1-toprJ1, to co-express all the three components of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 efflux pump (Figs. 2a and S9). In this construct, unlike tmexD1 that is tag-free, the other two adjacent loci are dedicated to give fusion proteins, namely (i) Strep-tag for TMexC1, and (ii) hexa-histidine (6x His) for TOprJ1 (Fig. 2a). Following the “two-step” affinity purification (Fig. S10), the resultant TMexCD1-TOprJ1 complex was purified to homogeneity (Fig. 2b). Gel filtration using a Superdex 200 column revealed that this tripartite complex elutes at a volume of ~9.8 ml, corresponding to a molecular weight of ~760 kDa. Negative staining assays illustrated our protein complex sample forming intact rod-like particles (Fig. 2c). This finding prompted us to further investigate how TMexCD1-TOprJ1 efflux machinery assembles by using cryo-EM single-particle analyses (Figs. 2d and S11–S13).

a Linear scheme for a single plasmid expression strategy engaged in production of the tripartite TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 efflux transporter. TOprJ1 tunnel-encoding gene is colored orange, the remaining two loci are presented in magenta for TMexC1 adapter, and blue for TMexD1 transporter, respectively. SP is colored green, and the two tags are highlighted in cyan for Strep, and blue for 6x His, respectively. b Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) profile of the purified tripartite system of the TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 multidrug efflux pump. An inset gel denotes the three components of TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 complex. c. Negative staining-based visualization for the tripartite TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 protein complex. The particles of TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 complex were indicated with red arrows. Besides SDS-PAGE (b), negative-staining electron microscopy (panel c) is a representative of over three independent assays. d A representative of 2D classification of cryo-EM graphs suggested a fully-assembled TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 complex with a channel shape. Surface presentation (e) and ribbon illustration (h) of cryo-EM architecture of the tripartite TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 machinery. f Top view of the tripartite TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 pump (e) via the counter-clockwise 90° rotation. g Bottom view of the TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 complex (f) by the counter-clockwise 180° rotation. i Top view of the tripartite TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 system (h) rotated at the counter-clockwise 90°. j Bottom view of the TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 pump (i) by the counter-clockwise 180° rotation. Designations: ParaC The araC promoter, S transcriptional start site, SP signal peptide, Strep Strep tag, 6x His hexa-histidine tag, A280 Absorbance of protein sample at the wavelength of 280 nm, mAu molar absorptivity unit, OM Outer-membrane, IM Inner membrane.

As expected, the reconstruction clearly showed electron potential map for all the three components of TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 complex (Fig. S11a–d). Individual structures of TMexC1, TMexD1, and TOprJ1 predicted by AlphaFold can be fitted into the electron potential map with minor adjustment. Cryo-EM structure of this tripartite pump was determined at 2.97 Å resolution (Table S1). Not surprisingly, the whole complex exhibits C3 symmetry with a height of 332 Å and a diameter of 129 Å (Figs. 2e–j, S13c). To rule out the possibility that the symmetry is an artifact due to applying symmetry during data processing, we reprocessed the data without applying symmetry. The reconstruction at 3.5 Å shows apparent C3 symmetry again (Figs. S11 and S13c), implying a resting (R) state for TMexC1D1-TOprJ1. Consistent with assembling modes of CusAB52 and AcrAB-TolC efflux42, our pump architecture also adopts a 3:6:3 stoichiometry (TOprJ1: TMexC1: TMexD1), displaying a vertically-elongated rod shape. The supramolecular structure consists of one TOprJ1 trimer, one TMexC1 hexamer, and one TMexD1 trimer (Fig. 2e–j). This largely agreed with an observation of size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 2b). In fact, the top and bottom of our complex structure are formed by TOprJ1 and TMexD1 trimer, which has an outer diameter of 60 Å (Fig. 3) and 97 Å (Fig. 2e–j), respectively. TOprJ1 and TMexD1 are separated by TMexC1 hexamer in the middle, which has an outer diameter of 129 Å (Fig. 2e–j). To assemble TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 complex, the α-barrel domain of TOprJ1 contacts the α-helical hairpin domain of TMexC1 in a “tip-to-tip” manner (Figs. 3–5), while the αβ-barrel and MP domains of TMexC1 form a hat sitting on top of TMexD1 (Figs. 6–7).

a Existence of TOprJ1 trimer suggested by gel filtration assay. b SDS-PAGE (12%) profile of the purified TOprJ1 component. Prior to the treatment with heating at 100 °C, TOprJ1 protein collected from size exclusion chromatography (panel a) displayed a mixture of solution states (from monomer, dimer to trimer) when separated with SDS-PAGE gel. In contrast, only monomer band was seen upon the TOprJ1 sample was treated at 100 °C for 15 min. The symbol of minus “–” denotes no heating at 100 °C, and the plus “+” refers to the treatment of heating at 100 °C. c TOprJ1 protein predominantly appears as homotrimer particles in negative staining trials. The particles of TOprJ1 homotrimer are circled in purples. As described in Fig. 2b, c, the experiments of SDS-PAGE (b) and negative stain (c) were performed with TOprJ1 channel in three replicates, and a representative result was displayed. d Ribbon presentation for structural architecture of the trimeric TOprJ1 channel. Three TOprJ1 protomers are separately colored orange, hot-pink, and purple blue. Clearly, every protomer can be divided into two subdomains, namely (i) α-barrel domain located in periplasm and β-barrel domain spanned bacterial outer-membrane. As for each protomer, an equational domain is formed that primarily consists of α1-helix. e Top view structure of TOprJ1 (d) with 90° counter-clockwise rotation. f Top view structure of TOprJ1 (d) rotated at 90° clockwise. g Overall structure of TOprJ1 protomer. Unlike the β-barrel domain that is composed of four β-sheets (β1 to β4), α-barrel domain majorly comprises eight α-helices (α1 to α8). Designations: OD280 optical density at the wavelength of 280 nm, mAu molar absorptivity unit, OM outer-membrane, C C-terminus, N N-terminus.

a SEC analysis and SDS-PAGE verification of the purified TMexC1 adapter, a member of fusion protein family. SEC assays suggested an assignment of the molecular size ( ~ 250 kDa) to the TMexC1 organization, and inside gel showed the molecular size ( ~ 42 kDa) of a TMexC1 monomer. 1# and 2# referred to two duplicates of TMexC1 preparations separated by 12% SDS-PAGE. The combined data indicated that solution structure of TMexC1 as a hexamer. b, c Ribbon structure of TMexC1 homo-hexamer and its top view with the counter-clockwise 90° rotation. Six protomers of TMexC1 were consecutively numbered (Protomer 1 to Protomer 6), and labeled in different colors. d Structural dissection of TMexC1 protomer with four distinct modules. TMexC1 is a fusion protein, in which four structural domains are connected by certain loops. Namely, they included (i) α-helical hairpin; (ii), lipoyl domain (LD); (iii), αβ-barrel; and (iv) membrane proximal (MP). The α-helical hairpin consists of 2 long α-helices (α1 and α2). The LD module is mainly formed by five short β-sheets. In addition to the α3-helix, the αβ-barrel domain also comprises the β2-strand and five continuous β-sheets (β8 to β12). The MP domain is consisted of eight β-strands, i.e., seven continuous β-sheets (β13 to β19) plus β1-sheet. e Ribbon presentation for the conserved LD domain of E. coli OGDH (PDB: 1PMR). K25 denotes the lipoylated residue of OGDH. f The known structure of E. coli PDH LD domain (PDB: 1QJO). K41 refers to the lipoylated site of PDH. g Structural characterization of TMexC1 LD domain. The putative K87 residue is a lipoylated site of TMexC1 LD domain. Designations: OD280 optical density at the wavelength of 280 nm, mAu molar absorptivity unit, M protein marker, kDa kilo Dalton, OM outer-membrane, C C-terminus, N N-terminus, PDH pyruvate dehydrogenase, OGDH oxoglutarate dehydrogenase.

a Assembly and relative orientation between TOprJ1 and TMexC1. The three TOprJ1 protomers are colored in green, cyan, and pink, respectively. The LC and SC protomers of TMexC1, which form larger and smaller contact with TMexD1, are separately colored orange and magenta. b, c Enlarged views on interactions between TMexC1 and TOprJ1 at the α3-α4 helices region. d, e Structural snapshots on an interplay between TMexC1 and TOprJ1 at the α7-α8 helices region. f Use of structure-guided, site-directed mutagenesis to analyze interface between TOprJ1 and TMexC1. The MIC measurements were carried out in triplicates for single-point mutants, and for six times towards double mutants. Each dot represents an individual value of tigecycline resistance. g Use of Western blot to verify expression of all the TMexCD1-TOprJ1 derivatives carrying the appropriate TOprJ1/TMexC1 components with certain point mutation. A representative result of three independent WB detections was showed here. Abbreviations: SP signal peptide, WB Western blot, 6x His hexa-histidine.

a SEC analysis of the inner-membrane TMexD1 transporter. b. The purity of TMexcD1 was validated by separation with SDS-PAGE (12%). The numbers (1# and 2#) indicated two duplicates of TMexD1 samples separated by 12% SDS-PAGE. c, d Overall structure of symmetric TMexD1 trimer and its top view with the rotation of counter-clockwise 90°. e, f Structural illustration for a TMexD1 protomer and its top view rotated at counter-clockwise 90°. Structural dissection of TMexD1 protomer defines three distinct modules, namely (i) docking domain, (ii) pore domain, and (iii) TM domain. g Ribbon presentation of docking domain. The TMexC1-docked funnel domain is composed of two subdomains (i) DN colored orange, and (ii) DC colored yellow. h, i Rainbow presentation for structural organization of TM domain and its top view rotated at counter-clockwise 90°. 12 TM helices (TM1 to TM12) are labeled. Four structural resembling subdomains, called PN1 (j), PN2 (k), PC1 (l), and PC2 (m) participate in assembly of pore domain. Designations: OD280 optical density at the wavelength of 280 nm, mAu molar absorptivity unit, IM inner membrane, TM Trans-membrane.

a Representative diagram of a binary plasmid system dedicated to the TMexC1D1 subcomplex production. The recombinant plasmid pBAD24::TMexC1 was used to express the periplasmic TMexC1 fusion protein, and the plasmid pET28::TMexD1-6x his was applied to give the 6x His-tagged TMexD1 transporter. The two plasmids were introduced into a single colony of E. coli BL21 expression host. b SEC analysis of the subcomplex of TMexC1 and TMexD1. An inside gel (12% SDS-PAGE) showed two components of the TMexC1D1 subcomplex. It is a representative result from three individual SDS-PAGE separations. c Structural insights into assembly of TMexC1D1 subcomplex. As for this subcomplex, it was illustrated with cylindrical helices and flat/fancy sheets. The TMexC1 hexamer, a trimer of TMexC1 dimers is connected with a TMexD1 trimer. Counter-clockwise 90° rotation of TMexC1D1 subcomplex (c) proceeded giving the top view (d) and its clockwise 90° rotation allowed visualizing the bottom view (e). f–k Structural dissection for interaction between TMexC1 hexamer and TMexD1 trimer. TMexD1 is colored green-cyan, and its adjacent four TMexC1 protomers (D, E, F, and I) are separately displayed in pink (f–h) magenta (i) lime (j) and light-orange (k). The hydrogen bonds are indicated with dashed lines, and hydrophobic contacts are shown with red line arrows. l Tigecycline MIC-aided functional analyses of TMexC1-TMexD1 interface. Following a panel of point mutations of TMexC1 and/or TMexD1, tigecycline MIC assays were conducted. Three independent experiments were performed and each dot represented an individual MIC determination.

Characterization of TOprJ1 pore

Despite the limited sequence identity (19.42%, Fig. S3), the outer-membrane protein TOprJ1 (477aa, ~53 kDa) is topologically-related to the E. coli TolC and Pseudomonas aeruginosa OprM (Fig. S4). The RMSD of TOprJ1 against TolC (PDB: 1EK9)53 and OprM (PDB: 6TA6)54 are 1.9 Å and 0.9 Å, respectively. In TMexCD1-TOprJ1 complex, the trimeric TOprJ1 forms the top of the rod-like structure (Fig. 2). To clarify whether the folding and trimerization of TOprJ1 is affected by its interacting with TMexC1, we expressed and purified an isolated TOprJ1 protein. Gel filtration revealed that TOprJ1 is eluted at a volume of ~11.66 ml, corresponding to a molecular weight of ~180 kDa (Fig. 3a). As shown in the SDS-PAGE (12%), the transition from monomer to trimer was observed for TOprJ1 protein without any heat treatment (Fig. 3b). However, only its monomer band was invariantly present, when treated with heating (Fig. 3b). As expected, the analyses of negative staining showed that TOprJ1 mainly behaves as a homotrimer in solution, independently of TMexC1 (Fig. 3c). Upon trimerization, TOprJ1 forms a “ring-like” open tunnel with a height of 129 Å and a diameter of 60 Å (Fig. 3d–f). The inner diameter of the narrowest section is 18 Å. TOprJ1 is structurally divided into two unique domains, namely (i) a small β-barrel domain spanned the outer-membrane, and (ii) a large α-barrel domain located within bacterial periplasm (Fig. 3d). The diameter of β-barrel domain (50 Å) is relatively-smaller compared to that of α-barrel domain (60 Å). As for each protomer, the β-barrel domain consists of four β-strands (β1 to β4) that are arranged in anti-parallels, and the α-barrel domain is formed by eight α-helices (Fig. 3g). Intriguingly, both N-terminal part (α1 to α4) and C-terminal part (α5 to α8) of this α-barrel domain almost mimic each other in overall folding (Fig. S4). It was noted that α1-helix primarily participates in forming an additional small domain, called equational domain (Fig. 3d, g). Therefore, elucidation of TOprJ1 here extended the repertoire of outer-membrane channel components, which namely included, but not be limited to (i) Pseudomonas OprM46,55 and OprN55,56,57, (ii) Escherichia CusC58,59, (iii) Campylobacter CmeC60,61, and (iv) Neisseria MtrE62.

Functional analyses of TMexC1 adapter

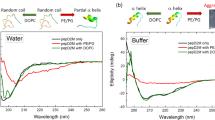

Relative to AcrA (or MexA) fusion protein, TMexC1 of 387 aa long gives 45.08% (or 41.51%) identity (Fig. S5). This suggests that TMexC1 is a putative adapter connecting TOprJ1 with TMexD1. As described for TOprJ1, TMexC1 protein alone was also prepared, and purified to homogeneity. As expected from SDS-PAGE profile, it was positioned at ~42 kDa (Fig. 4a). In size exclusion chromatography, TMexC1 displays an apparent size of ~250 kDa as it was eluted at a volume of ~11.84 ml on a Superdex G200 column (Fig. 4a). Consistent with that of gel filtration, cryo-EM structure of TMexC1 homo-hexamer illuminates a funnel-like architecture of ~130 Å high, of which top diameter is ~54 Å, and bottom one is ~113 Å (Fig. 4b, c). The low RMSD values (~0.1 Å to ~0.4 Å) suggested that TMexC1 gives a similar folding per protomer. In fact, TMexC1 is topologically divided into four domains, namely (i) an α-helical hairpin domain, (ii) a lipoyl domain (LD), (iii) an αβ-barrel domain, and (iv) a membrane proximal (MP) domain (Fig. 4d). Except for the central α-helical hairpin domain, the rest of 3 domains all require the residues from both the N- and C-termini (Fig. S5a, b). The α-helical hairpin domain forms a barrel and contributes to the TOprJ1-TMexC1 interaction (Fig. 5). In TMexC1 (and/or AcrA), the α-helical hairpin domain consists of 2 α-helices with 9 turns. In contrast, only 7 turns are carried within the equivalent α-helices of MexA. Accordingly, the height of MexAB-OprM (PDB: 6TA6, 327 Å) is shorter than those of AcrAB-TolC (PDB: 5O66, 333 Å) and TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 (332 Å). The αβ-barrel domain interacts with LD domain via two rings stacking. Whereas it is loosely tethered to MP domain, and thereby contributes to the TMexC1-TMexD1 interaction. In fact, the LD domain that is rich in β-fold, is also present in two well-known enzymes of central metabolism, including (i) 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH, Fig. 4e), and (ii) pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH, Fig. 4f).

Given the conservation in residues lipoylated (K25 for OGDH, Fig. 4e; and K41 for PDH, Fig. 4f), we anticipated that K87 of TMexC1 is a putative lipoylation site (Fig. 4g). Notably, we cannot rule out a role of the additional lysine K77 in LD domain of TMexC1. In particular, a C24 palmitoylation residue was bioinformatically assigned to the MP domain of periplasmic TMexC1 adapter (Fig. S5b). Inspired by the two distinct post-translational modifications, we then evaluated the in vivo roles in the context of tigecycline resistance by TMexCD1-TOprJ1 efflux pump. Structure-guided, point-mutagenesis was applied to generate a total of five TMexC1 mutants, including 3 single-point mutants (C24A, K77A, and K87A), and 2 double mutants (C24A/K77A, and C24A/K87A). The tigecycline MIC of 4.0 μg/ml was assigned to the positive control E. coli strain that expresses the wild-type TMexCD1-TOprJ1 (Fig. S5c). As expected, the K87A substitution of TMexC1 led to 8-fold decrement of tigecycline MIC in the E. coli host. A similar scenario was also observed for the TMexC1 (K77A) mutant (Fig. S5c). This underscored the importance of K87 (K77) lipoylation in proper TMexC1 connection TOprJ1 and TMexD1. Upon the mutation of TMexC1 (C24A), the recipient E. coli only gave the tigecycline MIC of around 1.0, 4-fold lower than that of parental version (Fig. S5c). We propose that putative C24 palmitoylation enhances the hydrophobicity of MP domain (Figs. 4b–d and S5a, b), and thereafter benefits an adaption of periplasmic TMexC1 hexamer to a trimeric TMexD1 transporter (Fig. 2h). Compared to C24A replacement, the K87A mutation seemed dominant. By contrast, the double mutation of TMexC1 (C24A/K77A) exerted a synergistic effect on this tripartite efflux system (Fig. S5c). Taken together, we anticipated that fatty acylation (i.e., palmitoylation and lipoylation) is essential for TMexC1 assembly.

Binding of TMexC1 adapter to TOprJ1 pore

As shown in complex structures of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 (Figs. S11–S13), TMexC1 homo-hexamer forms a funnel-like ring (Fig. 4b, c). Out of the four subdomains (Fig. 4d), only the central “α-helical hairpin” domain of TMexC1 is recruited to bind TOprJ1 partner at its α-barrel domain (Fig. 5a). The LD domain of TMexC1 does not interact with either TOprJ1 or TMexD1. In contrast, the remaining two domains (i.e., MP and αβ-barrel) are involved in TMexD1 interaction (Figs. 6 and 7). Based on their contact surfaces with TMexD1, TMexC1 protomers are provisionally divided into two groups: (i) large contact (LC) protomers, and (ii) small contact (SC) protomers. The details of TMexC1/TMexD1 interaction will be discussed later. The binding of TMexC1 to TOprJ1 appears in a “tip-to-tip” manner similar to that of AcrAB-TolC system (Figs. 5b and S13e)42,63. Besides a few electrostatic interaction, extensive hydrogen-bonding (H-bond) networks are formulated between TMexC1 α-helical hairpin and TOprJ1 α-barrel (α3-α4, in Fig. 5b, c; and α7-α8, in Figs. 5d, e and S13e). Among them, TOprJ1 pore offered 12 residues that are identical across a variety of TOprJ variants (Fig. S14), and TMexC1 donated 6 residues that are highly conserved in different TMexC subtypes (Fig. S15). This might highlight a universal mechanism for the assembly of TMexC fusion protein with TOprJ pore.

It is plausible that the negatively-charged D135 residue from one TMexC1 SC protomer forms a salt bridge with the positively-charged residue R210 on the α3-helix of TOprJ1 (Fig. 5b). Also, the side chains of the two residues (D135 and R210) give an H-bond interaction (Fig. 5b). Moreover, the main chain oxygen (O) atom of TMexC1 D135 residue produces an intense H-bonding network with the main chain nitrogen (N) atoms of the two residues (A217 and Y426) of TOprJ1. Similarly, the side chain O-atom of S138 from the same TMexC1 SC protomer forms H-bond interaction with G213 located at the α3-α4 linker region of TOprJ1 (Fig. 5b). The R127 from the adjacent TMexC1 LC protomer binds the main chain O-atom of TOprJ1 A212 residue via an H-bond (Fig. 5c). The neighboring arginine of TOprJ1 R210, (i.e., R209) exploits its guanidinium group to establish a H-bond with the main chain O-atom of A136 residue from the TMexC1 LC protomer (Fig. 5c). Of note, the same D135 residue from one TMexC1 LC protomer (rather than SC promoter) utilizes its hydroxyl group to give an H-bond with the side chain of Y419 residue positioned at TOprJ1 α7-α8 linker (Fig. 5d). In fact, this TMexC1 LC protomer also donates S138 residue to bind the main chain O-atoms of G422 and V423 from TOprJ1 α7-α8 linker (Fig. 5d). Similar to R209 of TOprJ1 α3-helix, R418 located at its α7-helix adopts an extended conformation to form an H-bond interaction with the main chain O atom of A136 residue arising from TMexC1 SC protomer (Fig. 5e). Since TOprJ1 R418 residue is flanked by L414 and V423, it might form hydrophobic interactions with two distinct residues, (i) L218 of the neighboring TOprJ1, and (ii) L131 of TMexC1 SC protomer (Fig. 5e). In particular, the main chain O-atoms of two distant TOprJ1 residues (G213/α3-helix and G422/α7-helix) participate in formation of H-bonds with the main chain N-atom of TMexC1 residue Q140.

To investigate if the landscape of TOprJ1-TMexC1 interplays we observed is functionally relevant, we totally developed 23 combinations of TMexC1 (and/or TOprJ1) mutations, and then assayed the alteration of tigecycline MIC in different E. coli recipients. Here, the positive control E. coli strain harbors a plasmid-borne WT TMexCD1-TOprJ1. Namely, the collection of efflux pump derivatives contained (i) 6 TOprJ1 single-point mutants, such as TOprJ1(R210A), (ii) 5 single TMexC1 mutants, like TMexC1(R127A), and (iii) 12 combined TOprJ1 and TMexC1 mutations, exemplified with TOprJ1(R210A)/TMexC1(D135A) (Fig. 5f). Relative to the control strain that has tigecycline MIC of 4.0 μg/ml, the R209A mutation of TOprJ1 rendered the host E. coli in 8-fold decrement of tigecycline insusceptibility (Fig. 5f). The rest of five E. coli derivatives that express a single TOprJ1 mutant invariantly retained tigecycline MIC of ≤0.25 μg/ml (Fig. 5f). Supported by the fluctuation of tigecycline MIC that ranged from 0.125 to 1.0 μg/ml, all the five TMexC1 mutants enabled the recipients to give varied level of tigecycline susceptibility. The strain that contains a D135A (A136G) mutation in TMexC1 possessed a tigecycline MIC of ~0.5 (0.25) μg/ml. As for the strain that carries any one of the three mutations (R127A, L131A, and S138A), the tigecycline MIC value was reduced to 0.125 μg/ml (Fig. 5f). The majority of strains having the combined mutations of TOprJ1 and TMexC1, was invariantly characterized by the MIC of tigecycline that is as low as ≤0.125 μg/ml (Figs. 5f and S16). Of four TOprJ1 mutations in combination with TMexC1(D135A), only R210A mutation can synergistically reduce bacterial tigecycline insusceptibility (Fig. 5f), and the rest of 3 derivatives (A217G, Y419A, and Y426A) conferred relatively-higher tigecycline MIC at the level of 0.25 to 0.5 μg/ml (Fig. S16). In particular, Western blot assays demonstrated that all the mutants are well expressed (Fig. 5g). This ruled out the possibility that dysfunction of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 is due to its expressional loss. Collectively, the repertoire of TMexC1 binding TOprJ1 defines a shared mechanism for TMexC-TOprJ assembly, and plays an indispensable role in tigecycline expulsion by such kind of RND-type tripartite machinery.

Characterization of TMexD1 transporter

As the largest subunit of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 tripartite system, the inner membrane-localized TMexD1 (1044 aa, ~110 kDa) exhibited ~48.5% identity to the two well-known transporters AcrB and MexB (Fig. S7). To address the characteristics of TMexD1, we prepared its recombinant form in vitro. Our SEC analysis showed that the dominant TMexD1 peak of interest is eluted at the volume of ~12.5 ml, giving an apparent size of ~330 kDa (Fig. 6a). As predicted, the purified form of TMexD1 is positioned at ~110 kDa in our SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6b). The combined data suggested solution structure of TMexD1 trimer, which is further validated by cryo-EM structure (Fig. 6c, d). Unlike an asymmetric organization of AcrB (Fig. S17a, b)48 and MexB (Fig. S17c–f)46,54, TMexD1 here organizes as a triangular prism-like homotrimer with C3 symmetry (Figs. S13c, d and S17g). In brief, the height of TMexD1 architecture is ~121 Å, and the two diameters is separately 42 Å on the top, and 99 Å on the bottom (Fig. 6c, d). Each TMexD1 protomer is composed of three distinct domains (Fig. S7), namely (i) the top docking domain, (ii) the portal domain, and (iii) the bottom transmembrane (TM) domain (Fig. 6e, f). Among them, the docking domain contains two subdomains (i.e., DN and DC). As depicted in Fig. 6g, both DN and DC subdomains are of α/β fold in nature. However, different from DC, the DN subdomain contains one extended hairpin, which points away from the main body of the docking domain. This long loop from the docking domain threads through a hole in the neighboring protomer, which might facilitate the relative movement of TMexD1 protomers (Fig. 6g). The bottom TM domain is consisted of 12 TM helices and spans the bacterial inner-membrane (Fig. S7). The N-terminal TM1-TM6 helices are related to its C-terminal TM7-TM12 helices by a pseudo-two-fold axis (Fig. 6h, i). It was noted that TM4 and l0 are two conserved and important helical motifs, whose equivalents already been well documented in proton translocations by the other RND transporters. The portal domain can be further divided into 4 subdomains with a similar folding pattern, namely (i) PN1 (Fig. 6j), (ii) PN2 (Fig. 6k), (iii) PC1 (Fig. 6l), and (iv) PC2 (Fig. 6m). Like DN and DC, the two docking subdomains (Fig. 6g), all the four subdomains of this pore also feature a similar α/β-folding pattern (Fig. 6j–m). They all contain a flat β-sheet, which is formed by four (or five) anti-parallelled β-strands. Each of them invariantly positions two α-helices on the same side of the β-sheet (Fig. 6j–m). As for asymmetric structure of AcrB trimer48, each protomer can be characterized in three different states (Fig. S18a–f): loose state (L) accessible to substrates, tight state (T) dedicated to substrate binding, and open state (O) for substrate extrusion. TMexD1 deviates from the three states to the same extent (Fig. S18a–c). Specifically, the RMSD between TMexD1 and LTO states of AcrB (PDB: 5O66) are 2.10 Å, 1.81 Å, and 1.95 Å, respectively. The RMSD between TMexD1 and LTO states of MexB (PDB: 6TA6) are 1.66 Å, 1.62 Å, and 1.74 Å, respectively.

As expected from multiple sequence alignments (Fig. S19), the paradigm TMexD1 is akin to the other five TMexD variants (TMexD2 to TMexD6), suggesting that they might share a similar folding mode. Not only are a panel of putative substrate-binding sites conserved (Fig. S7), but also an arsenal of predictive transmembrane determinants is dominant across all the six TMexD subtypes (Fig. S19). To ascertain functional importance of these conserved sites in TMexD1, we selected 10 representative residues for site-directed mutagenesis. In addition to two amino acids (D191 and R776) on the docking domain, we introduced four residues (R169, G612, G617, and G619) of the portal domain, as well as four sites (D409, D410, R966, and T973) from the TM domain (Fig. S19). All of them were subjected to an alanine substitution. The only exception denoted the two glycine residues (G612 and G617) that are additionally replaced with a proline. Unlike the R966A mutation that exerts no effect on TMexD1 function, the D409A substitution lowered the tigecycline MIC of its recipient strain by 2-folds (Figs. S19-S20). Upon substituted with a single alanine, the three residues (D191, D410, and R776) invariantly led to 4-fold decrement of bacterial tigecycline resistance. The remaining 5 residues are critical for TMexD1 activity, supported by the 8 to 32-fold reduction of tigecycline MIC values we observed (Fig. S20). Therefore, our results illuminated functionality of TMexD1 in the context of tigecycline resistance.

Assembly of TMexC1-TMexD1 complex

We are aware that TOprJ1 pore exploits the “tip-tip” interaction for TMexC1 binding, independently of TMexD1 transporter (Fig. 5a). It is reasonable to ask the question of whether TMexC1 adapter assembles with TMexD1, independently of TOprJ1 pore. To test this hypothesis, we co-expressed TMexC1 and TMexD1 using a binary plasmid system (Fig. 7a). Along with SDS-PAGE gel profile, gel filtration confirmed that TMexC1 forms a stable complex with TMexD1 (Fig. 7b). As depicted in cryo-EM structure of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 system, extensive interactions are required to maintain the stability of TMexC1-TMexD1 intermediate (Fig. 7c–e). Overall, each TMexD1 protomer contacts two neighboring TMexC1 protomers. One of the TMexC1 protomer gives more extensive interactions with TMexD1 than the other TMexC1 protomer, which causes slightly-different TMexC1 conformations (Figs. 4b, c, 7c–e). The RMSD between the neighboring TMexC1 protomers is 2.17 Å. In addition to the primary form of H-bond network (Figs. 7f–k and S13f), they also include (i) electrostatic interactions/salt bridges (Fig. S21) and (ii) hydrophobic interaction (Figs. 7f, h, k and S13f).

The α-helical hairpin, LD and α/β-barrel domains of the TMexC1 hexamer form a stack of three continuous rings (Fig. 4b–d). Among them, the α/β-ring fits tightly with the top of TMexD1 trimer. Together with TMexC1 α/β-barrel, its MP domain also adopts symmetric conformation and participate in the interactions with TMexD1 docking and pore domains (Fig. 7c–e). Like TOprJ1 R210 that binds TMexC1 D135 via a salt bridge (Fig. S21a-e), the 3 positively-charged residues (R291, R308 and R373) of TMexC1 are positioned to separately make electrostatic interactions with the 4 negatively-charged residues (D191, D728, E231 and D656) of TMexD1 (Fig. S21d-g). Both the G197 amino acid of TMexD1 (Fig. 7f), and its residue Q731 interacts with TMexC1 Y289 via hydrophobic contact (Fig. 7k). Via tight packing, W805 of TMexD1 DC subdomain forms a hydrophobic cation-π interaction with R312 of TMexC1 MP domain (Fig. 7h). In particular, extensive H-bond networks detected positive for the assembly of TMexC1-TMexD1 complex. Specifically, the α/β-barrel residues R58 and R291 of TMexC1 are located to make H-bond interactions with Q193 and G197 from the DN subdomain of TMexD1 (Fig. 7f). The main chains of A653, L655 and D656 of TMexD1 PC1 subdomain form H-bond interactions with either R365 or S360 of the MP domain of TMexC1 (Fig. 7g). Notably, TMexC1 protomer #2, rather than its protomer #1, arranged three α/β-barrel residues (S267, T268, and Q270) to give 3 individual H-bonds with TMexD1’s docking subdomain residues R254, S260, and R261, respectively (Fig. 7i). Similar scenarios were also observed for the two MP residues (S342 and R308) of TMexC1 protomer #3, during the cross-talking with E229 and E231 at the tip of DN subdomain arising from TMexD1 (Fig. 7j). Whereas, binding of TMexC1 protomer #4 to TMexD1 is dependent on hydrophobic interaction in combination with an H-bond (Fig. 7k).

To investigate the physiological relevance of TMexC1-TMexD1 interplay to tigecycline efflux, we designed a series of structure-guided TMexC1 (and/or TMexD1) mutants. Namely, they included (i) 9 TMexC1 single-point mutants, (ii) 7 TMexD1 single-point derivatives, and (iii) 17 combination TMexC1 and TMexD1 mutants. As expected from assays for tigecycline insusceptibility, none of the 9 TMexC1 single-point mutants can render the recipient to give tigecycline MIC of over 0.5 μg/ml (Fig. 7l). Except for the two alanine substitutions of TMexD1 (E231A and D728A) that only led to 4-fold decrement in tigecycline MIC, the rest of five single-point mutants were largely inactive with tigecycline expulsion, supported by the 8 to 32-fold reduction of tigecycline MIC, compared to that of WT TMexD1 (Fig. 7j–l). Not surprisingly, all the 17 combined mutations of TMexC1 and TMexD1 consistently compromised bacterial tigecycline resistance (Fig. S22a, b). Similar results were obtained for AcrA-AcrB binding interface64, highlighting functional conservation in RND-type efflux pumps. Therefore, the integrative evidence confirmed functional importance of TMexC1-TMexD1 assembly in tigecycline resistance.

Substrate recognition of TMexD1 transporter

As expected from the prior studies, not only does the paradigm AcrB protomer exhibit a series of symmetric states (Fig. 8d–g) (PDB: 2I6W65, 3D9B66, 4K7Q67, 5V5S48, and 6ZOE49), but also it features an asymmetric conformation (Figs. S17, and S23-S24) (PDB: 5JMN68, 2HRT44, 2GIF44, and 5O6648). Among the symmetric structures, an overall folding of AcrB (PDB: 6ZOE)49 is most similar to that of TMexD1 with an RMSD value of 1.44 Å. The RMSD values between TMexD1 and other symmetric AcrB structures ranged from 1.72 Å to 1.80 Å. In the asymmetric state (Figs. S23-S24), three AcrB protomers adopt distinct configurations: “L” (loose)/Access, “T” (tight)/Binding, and “O” (open)/Extrusion. In the “L” protomer, a channel leads from the periplasm into the protomer. In the “T” protomer, the channel extends deeper into a central cavity, which serves as the loading site for diverse substrates and/or inhibitors69,70. In the “O” protomer, a channel links the central cavity to the substrate tunnel (Fig. S23-S24). Presumably, upon the diffusion of some substrates through these channels, the switching of the three configurations drives substrate efflux. As for the symmetric state, AcrB adopts a C3 symmetric conformation, in which all three protomers resemble the “L” protomer in the asymmetric state (Fig. 8a, d–g). The lack of channel leading to the substrate tunnel allowed the proposal of “L”-type symmetric state as an inactive form.

a Schematic representative for symmetric AcrB trimer (PDB: 5V5S). Cartoon presentation for apo-form (b) and NMP-liganded state (c) of trimeric TMexD1 efflux pump (this study). Surface structure of symmetric AcrB trimer in top view (d) and front view (e). f Surface presentation of symmetric AcrB trimer sliced with a horizontal plane. g Surface of symmetric AcrB trimer is sliced with a vertical plane. A substrate tunnel leading to the periplasm is determined in each protomer (in a, f & g). Surface presentation of symmetric/resting TMexD1 trimer in top view (h) and front view (i). Surface of symmetric/resting TMexD1 trimer sliced with a horizontal plane (j) or a vertical plane (k). A closed cavity was detected in each protomer. Surface presentation of the resting NMP-liganded TMexD1 trimer in top view (l) and front view (m). Surface of the resting NMP-liganded TMexD1 trimer sliced with a horizontal plane (n) or a vertical plane (o). The closed cavity occurs in every protomer. Notably, the closed cavity is assumed to appear in each protomer (in panels b, c, j, k, n & o). p HPLC profile of the positive control, tigecycline at varied levels. q Use of HPLC assays to reveal that cytosolic tigecycline is largely reduced upon expression of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 in the E. coli ΔacrB strain. A representative result is given from three independent trials. The data validated that TMexCD1-TOprJ1 efflux pump enables the ΔacrB mutant of E. coli to export tigecycline. Designations: L loose state, R resting state, HPLC high performance liquid chromatography.

Cryo-EM structures of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 resemble those of AcrAB-TolC (Figs. S17 and S25). Like TOprJ1 and TMexC1, TMexD1 also adopts a C3 symmetric conformation (Table S1, and Fig. S13c, d). Notably, each TMexD1 protomer contains a central cavity that is isolated from both the periplasm and the substrate tunnel. A similar conformation has been observed for Campylobacter jejuni CmeB multidrug efflux pump, which was named resting state60. Single-molecule FRET experiments in the same study suggest that the resting state of CmeB is a functional intermediate state during the transportation process. Thus, the configuration adopted by TMexD1 here was designated as “R” state for resting (Fig. 8h–k). This observation is different from that of asymmetric AcrB in “L” state (Fig. 8). Compared to AcrB in the “L” or “T” state, the PC2 subdomain of TMexD1 shifts toward the PC1 subdomain (Fig. S18a–f), which prevents the substrate from entering the binding pocket. Unlike the three subdomains (PN2, PC1 and PC2) TMexD1 that are conformationally similar to the equivalents of AcrB in “O” state, the conformation of TMexD1 PN1 is close to that of AcrB in “L” or “T” state (Fig. S18). This might efficiently block the substrate from entering the central channel of the TMexCD1-TOprJ1 system.

In spite of our continued efforts, we were unsuccessful in obtaining the cryo-EM structure of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 liganded with the tigecycline substrate. However, structural alignment of its apo-form with AcrB suggested a putative pocket for substrate entry (Fig. S26). This predicted cavity is lined with 11 hydrophobic amino acids, composed of (i) five residues (F136, I139, F180, F279, and Y329) located on PN2 subdomain, and six residues (F608, V610, F613, F615, I624, and F626) positioned on PC1 motif (Fig. S26a, b). Although that TMexD1 exhibits only ~48% identity with AcrB (Fig. S7), 9 out of the 11 pocket-forming residues are conserved in both TMexD1 and AcrB. The only exception lies in the two TMexD1 residues (I139 and F279) that are separately replaced by V139 and I277 in AcrB (Fig. S26c, d). As supported by genetic assays combined with tigecycline MIC determination, a number of pocket-forming residues of TMexD1 (e.g., I139, Y329, and V610) are functionally required for TMexCD1-TOprJ1 machinery (Fig. 9). It is expected that the availability of substrate-bound TMexCD1-TOprJ1 complex structure enables capturing altered conformation of pocket ready for substrate entry and/or release in the near future. In particular, conformations of the whole substrate-entering tunnels are not identical in TMexD1 and AcrB. It is plausible to ask the question of whether or not the kind of tunnels play roles in substrate promiscuity by TMexD1 transporter.

a The presence of NMP inhibitor eliminates the tigecycline insusceptibility of K. pneumoniae AH8I, a strain naturally carries the tmexCD1-toprJ1 cluster. b The recombinant strain of BL21 that produces TMexCD1-TOprJ1, remains sensitive to tigecycline upon the NMP inhibitor is present. Three independent MIC determinations (a, b) were conducted here, in which each dot indicates an individual value. Data are shown as means ± SD (standard deviations), and the significant difference was analyzed in two-tailed way of variance via Mann Whitney test. ** refers to p < 0.01. c A cavity of TMexD1 occupied with a molecule of NMP inhibitor. Fo-Fc omit electron density map for NMP inhibitor was contoured at 5 sigma level. d Structural insights into an interplay network of NMP inhibitor with TMexD1. The NMP molecule and TMexD1 are shown in stick and surface. A number of TMexD1 residues that are implicated into NMP binding are highlighted in sticks. e Structural comparison of apo TMexD1 with its NMP-liganded form. Besides a majority of conserved cavity-forming residues, the superimposed structures revealed that the NMP inhibitor triggers the conformational shift (shown with a dashed lined arrow) of two key residues (F136 and F180). f Varied roles of some TMexD1 substrate-binding sites in tigecycline MIC. As described in Figs. 2a and 5g, a schematic representative (inside graph) was provided for illumination of engineered expression of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 pump in E. coli (f). Three independent experiments were performed with the E. coli BL21 strain that carries a series of TMexC1-TMexD1 derivatives, and each dot represented an individual MIC determination. g Western blot (WB) analyses reveal that all the TMexCD1-TOprJ1 derivatives are well expressed in E. coli host. A representative result is given from three independent WB experiments.

Inhibition of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 efflux pump by NMP

Given that TMexD1 is an AcrB paralog, we sought direct evidence of its role in promoting antibiotic expulsion. To eliminate basal expression of acrB, we generated ΔacrB strain of E. coli BL21 as a recipient. As expected from the High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) analyses, the positive control tigecycline at varied level is constantly eluted at the retention time of 3.3 min (Fig. 8p). When grown on the condition supplemented with tigecycline, the E. coli ΔacrB strain was found to contain tigecycline at relatively-high level of ~108.4 μg/ml ( ~ 565 μg/g wet weight, Fig. 8q). In contrast, the introduction of a plasmid-borne tmexCD1-toprJ1 largely expelled tigecycline out of the ΔacrB recipient cell, in that the intracellular antibiotic is reduced to ~1.8 μg/ml ( ~ 9 μg/g wet weight, Fig. 8q). This confirmed that TMexD1 is an efficient RND-type tigecycline exporter.

It is well-established that 1-(1-naphthylmethyl) piperazine (NMP) acts as a potent RND-type efflux pump inhibitor, and thereafter restores tigecycline susceptibility in E. coli and its relatives71,72. Consistent with the description by Lv and colleagues22, K. pneumoniae AH8I, a field strain tested positive for the tmexCD1-toprJ1 cluster, can be resensitized by NMP compound to tigecycline, a “last-resort” antibiotic in clinical settings (Fig. 9a). Similarly, addition of NMP inhibitor substantially reversed phenotypic insusceptibility in E. coli BL21 to tigecycline, which is due to an over-expression of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 complex by a recombinant plasmid (Fig. 9b). Inspired by inhibitory efficacy of NMP on transferable tigecycline resistance, we attempted to elucidate the underlying mechanism by using cryo-EM technology. The incubation of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 with NMP ligand allowed determination of its complex structure at 3.0 Å resolution (Figs. S12-S13). The structure of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 liganded with NMP inhibitor is superimposable on the structure of its apo form with C3 symmetry (Figs. S13c, d, S25a–d). The RMSD value of NMP-liganded TMexCD1-TOprJ1 complex against its apo form is 1.04 Å, indicating that they share similarity in overall structures (Fig. S25). All the three TMexD1 subunit adopt the “R” configuration with an NMP inhibitor placed in the central cavity (Fig. 8c, l–o). The clear electron density for NMP can be well matched by its chemical structure (Fig. 9c). In brief, each NMP molecule forms an extensive network of hydrophobic interactions with 11 residues from the central cavity that is predicted to be occupied by tigecycline substrate (Figs. 9d and S26). Specifically, the piperazine group of NMP interacts with four TMexD1 sites (F136, Y329, Y571, and F615), while the naphthylmethyl group interacts with the remaining 7 TMexD1 residues (I139, F180, F279, F608, V610, F613, and F626). Except for Y571 in place of I624 (Fig. 9d), the rest of 10 binding sites in the NMP-liganded structure, resembles those of the putative tigecycline-bound structure (Figs. S26-S27). Compared to the apo TMexCD1-TOprJ1 structure, the central cavity in the NMP-bound structure is dramatically reorganized to better accommodate NMP. Notably, residues (F136 and F180) of TMexD1 separately undergo 3.0 Å-movement and 4.0 Å translocation to fit NMP (Fig. 9e). These findings support a model in which NMP inhibits transferable TMexCD1-TOprJ1 machinery by mimicking tigecycline and stabilizing the TMexD1 transporter in its “R” conformation.

Guided by structural observations, we functionally defined this NMP-occupied pocket by employing site-directed mutagenesis together with tigecycline MIC assays. Except for Y571 and F613, which were not included in this study, 9 of 11 TMexD1 residues were selected for single alanine substitution. In particular, a total of 4 TMexD1 double-point mutants were introduced, namely F136A/I139A, F608A/F613A, F608A/F615A, and I624A/F626A. Unlike the TMexD1 single-point “F626A” mutant that only lowers tigecycline MIC by 2-fold, the three single-point mutants of TMexD1 (F136A, F180A, and F608A) led to 4-fold decrement of tigecycline MIC in the recipient strain (Fig. 9f). Except for Y329A mutation that led to an 8-fold reduction of tigecycline MIC, the remaining 4 single-point mutants (I139A, F279A, V610A, and F615A) resulted in a 16- to 32-fold increase of bacterial susceptibility to tigecycline (Fig. 9f). Not surprisingly, all the four combined mutations completely dampened TMexD1 activity, as supported by the 32-fold reduction of tigecycline resistance (Fig. 9f). Thus, the disruption of NMP-bound pocket mimics the inhibitory activity of NMP.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, tetracycline resistance is attributed to a total of four mechanisms (http://faculty.washington.edu/marilynr/tetweb1.pdf)20. Among them, the leading one is constituted by 37 diverse efflux pumps (exemplified with TetA73, TetB74, and TetK75). Second, a collection of ribosome protection proteins (such as TetM76,77,78, TetO79,80,81, and TetW82,83,84) competitively expels drug molecules from ribosome-binding sites20. Additionally, a cluster of 16S rRNA mutations (e.g., G1058C substitution85) enables a lower antibiotic affinity for ribosomes to give tetracycline tolerance20. Except for Vibrio Tet34 that is rarely annotated as a xanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl-transferases86, a group of unrelated flavoenzymes comprising TetX28,87,88, Tet3789, and 10 variants of soil origin (Tet47 to Tet56)90,91, acts as the paradigm tetracycline modifier capable of destroying tetracycline antibiotics87. In contrast, the next-generation of semi-synthetic minocycline derivative, tigecycline was clinically demonstrated to display intensively antimicrobial activity against a broad range of Gram-positive (and/or Gram-negative) bacterial pathogens15,20. The primary mechanism for tigecycline action lies in its competition for ribosome occupancy, thereafter interfering with bacterial protein translation20. Consistent with the notion that chromosome-encoded RND efflux pump might confer an intrinsic antimicrobial resistance29,49, an expanded arsenal of plasmid-borne tmexCD-toprJ determinants raises an alternative mechanism for mobile tigecycline resistance22,92.

The integrative evidence accumulated in this study provides a comprehensive biochemical and structural definition for the prototypic mobile TMexCD1-TOprJ1 functionality. Prior to structural exploration, we confirmed the ability of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 in both K. pneumoniae and E. coli to expel tigecycline in vivo (Fig. 8). In parallel to AcrAB-TolC43,69 and MexAB-OprM54, this constitutes the physiological basis of phenotypic resistance of bacterial recipient to tigecycline (Fig. 1). Fortunately, our continued efforts enabled the establishment of a unique single plasmid expression system to fully assemble TMexCD1-TOprJ1 tripartite complex in vivo (Figs. 2a and S9-S10). In particular, we illuminate the cryo-EM structures of the paradigm TMexCD1-TOprJ1 alone and in complex with the NMP inhibitor (Figs. 2 and S25). In line with those of RND tripartite pumps29, the TMexD1 trimer spans the inner membrane, serving as the engine of the efflux pump, while the TOprJ1 trimer penetrates the peptidoglycan and outer membrane, functioning as the pipe of the pump. Meanwhile, the TMexC1 hexamer connects TMexD1 and TOprJ1, acting as an adapter between the engine and the pipe (Figs. 2–7). It seemed true that the similar architecture shared by a broad variety of RND-type pumps underscored an evolutionarily-conserved mechanism for bacterial survival in the adaption to excess noxious instances, esp. antimicrobials (Fig. S17).

Probably, the interchangeability of outer-membrane channel (esp., OprJ/OprM/OprN) creates some chimeric TMexCD1-based tripartite efflux systems56,93,94. This stimulates an expansion of substrate promiscuity, resulting in a wide range of cross-resistance. In spite of an assumption that the adapter of RND pump like AcrA, requires fatty acyl modification for its activity, it awaits direct demonstration. As for TMexC1 that is analogous to AcrA, we elucidate the previously-unclear functional relevance of both C24 palmitoylation and K77/K87 lipoylation as judged by tigecycline MIC evaluation (Fig. S5). Notably, a total of 85 mutations on TMexCD1-TOprJ1 we generated here benefited our understanding the relatively-complete landscape for de novo assembling the kind of tripartite pump complex. Of particular note, two kinds of bipartite interfaces are functionally defined, namely (i) the “tip-to-tip” contact of trimeric TOprJ1 pore with TMexC1 hexamer (Figs. 5a–e, S21), and (ii) docking of TMexD1 trimer into TMexC1 fusion protein (Figs. 7a–k, S21). The prevalence of “loss-of-function” mutations in the aforementioned two interfaces might render them vulnerable to certain inhibitors (Figs. 5f and 7l). Therefore, besides TMexC1 fatty acylation sites, it is of much interest to explore the potential of bipartite interfaces as alternative drug targets.

A total of three conformational states (L, T, and O) occur in the asymmetric AcrB trimer, with each protomer adopting one (Figs. S23-S24). In general, each AcrB monomer undergoes an iterative transition of conformation (L to O) to enable the drug export cycle. As expected from our cryo-EM structure of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 complex, TMexD1 is architecturally similar to AcrB. However, we are not aware whetherTMexD1 resembles AcrB to accept the regulation by an auxiliary AcrZ partner (Fig. S17b)42,48. Noticeably, TMexD1 here is captured to adopt a symmetric trimer organization with all three subunits in the same conformation (Fig. 8h–k), which is markedly different from the asymmetric “L, T, O” trimer observed for AcrB (Figs. S23-S24). Thereafter, this is called “R” configuration. Not only does the “R” configuration of each TMexD1 protomer fail to match the “L” state of symmetric AcrB (Fig. 8a, d–g), but also cannot be lined with any one of the “L, T, or O” states observed for asymmetric AcrB (Figs. S23-S24). Specifically, the proximal pocket and exit of TMexD1 are both closed, precluding classification as either “L” or “O” states (Fig. 8b). In spite that the distal pocket of TMexD1 is open and capable of accommodating drug molecules, the closed proximal pocket distinguishes it from the AcrB “T” state, where both the proximal and distal pockets remain open. The “R” configuration renders TMexD1 central cavity isolated from the solvent, indicating that it is trapped in an inactive state. This is partially consistent with the closed state of MexB protomer54. As shown in the complex structure of NMP/TMexCD1-TOprJ1, an NMP molecule occupies a continuous cavity located in the distal pocket (Fig. 9c–e). This is aligned with the distal pocket capable of accommodating substrate molecules. Thus, we concluded that the NMP inhibitor traps TMexD1 in a “R” configuration (Fig. 8l–o), which is far different from “T” configuration of AcrB captured by the other inhibitor MBX313248. The combination of structural and mutational analyses allowed us to believe that the NMP inhibitor suppresses TMexC1D1-TOprJ1 action by freezing the pump in its inactive state (Fig. 9). This is mainly due to the peristaltic TMexD1 exporter that is disconnected from recycling via its three consecutive configurations.

As expected from our microscale thermophoresis (MST) assays, TMexC1 adapter can efficiently bind to TMexD1 transporter (Fig. 10a), and TOprJ1 tunnel (Fig. 10b). Consistent with gel filtration data (Fig. 7b), this biochemical data also additionally supports the in situ AcrAB intermediate obtained by electron cryo-tomography63. Combined with recent investigation on a series of RND-type pumps (e.g., AcrAB-TolC45,63 and CusCBA52,95,96), our study allowed an alternative proposal that TMexCD1-TOprJ1 assembles in three steps (Fig. 10c): (i) TMexD1 is synthesized in the cytoplasm and inserted into the inner membrane, where it forms a homo-trimer; (ii) the hexameric TMexC1 adapter synthesized in the cytoplasm, is transported into the periplasmic space, and interacts with TMexD1 transporter via extensive electrostatic interactions; and (iii) TOprJ1 is inserted into the outer membrane, and attaches to TMexC1 through an intermeshing cogwheel-like interaction (Figs. 5 and 10c). Like the prevalent RND transporter AcrB44,49 and CmeB60, TMexD1 likely transfers substrates through a peristaltic mechanism that involves coordinated, sequential transitions between three distinct conformations: access, binding, and extrusion (Fig. 10d). Intriguingly, the conformation captured in this study is distinct from these states, which represents a resting state. The substrate such as tigecycline, might transform this resting state into the working state, while the inhibitor NMP stabilizes the resting conformation, effectively inactivating the transporter (Fig. 10d). In sum, this study provides precise structural insights that could guide the design of drugs targeting TMexC1D1-TOprJ1. While the working model deserves further exploration.

a Use of microscale thermophoresis (MST) to analyze binding of TMexD1 transporter to TMexC1 adapter. b MST analysis of an interplay between TOprJ1 tunnel and TMexC1 adapter. Three independent MST assays were conducted here. Binding curves were plotted, in which each data dot is expressed in mean ± standard deviations (SD). c Schematic diagram of an alternative pathway proposed for TMexCD1-TOprJ1 supramolecular complex. In the step 1, the adapter of TMexC1 hexamer binds to an inner-membrane transporter TMexD1, giving an intermediate of TMexCD1 subcomplex. This intermediate is then connected with an outer-membrane tunnel, TOprJ1 trimer in the step 2. As a result, this leads to formation of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 efflux pump. Protein is shown in surface presentation. TMexD1 trimer is given in green. TMexC1 hexamer is displayed in blue. TOprJ1 trimer is colored salmon.

The phylogenetic origin of mobile RND-type TMexCD1-TOprJ1 pump is only partially understood right now. In 2020, a plasmid-borne “tmexCD1-toprJ1” pump cluster was alarmingly detected from the ESKAPE-type pathogen, K. pneumoniae22. It is unusual, but not without any precedent. This is because a presumably-chimeric RND-type “mexAB-cusC” silver/copper efflux operon is located in a CP4-like prophage captured by the pan-drug resistant plasmid pNDM-CIT (acc. no.: JX182975) of Citrobacter freundii, a urinary isolate from an Indian inpatient, in 201097. Using the “mexAB-cusC” operon as a query, in silico hunting returned us five additional BLASTn hits on distinct plasmids with over 99.9% identity and 100% coverage. Namely, they include (i) Leclercia adecarboxylata plasmid pLec-476 (acc. no.: KY320277), (ii) pR17.4855_328k (acc. no.: CP100723) of S. enterica serovar Mbandaka, (iii) S. enterica serovar Typhimurium plasmid pF18S031-1 (acc. no.: CP082423), (iv) plasmid p53828CZ_VIM (acc. no.: CP085766) of K. michiganensis, and (v) plasmid p60214CZ_VIM (acc. no.: CP085747) from Enterobacter hormaechei. This represents a second example of plasmid-mediated cross-species transferability of RND-type “mexAB-cusC” efflux machinery. Not surprisingly, we noticed that the host range of tmexCD-toprJ variants is shortly extended to ~10 species (e.g., Klebsiella and Proteus) worldwide, posing the possibility of interspecies transmission40,92. Combined with epidemiological studies, database search already suggested that the mobile tmexCD1-toprJ1 element dates back to (i) the inpatient isolates of K. pneumoniae from two provinces (Jiangsu and Tianjin) of China, in 201231, and (ii) a plasmid pMKPA34-1 (acc. no.: MH547560) of P. aeruginosa clinical isolate from India in 199740. It seemed likely that the kind of TMexCD-TOprJ tigecycline resistance is dominant in poultry production, prior to its entry into human clinic sector24,31,40. Because of the prototype mexCD-oprJ efflux operon that is located on P. aeruginosa chromosome98, we anticipated that it is ancestry version of tmexCD1-toprJ1 exclusively on plasmid of K. pneumoniae. The notion that a majority of tmexCD1-toprJ1 cluster is coharbored with other resistance determinant mcr-8 on a same plasmid is largely explained by the shared preference for plasmid vehicles31. The similarity in plasmid genetic contexts allows the proposal that Aeromonas acts as an intermediate host for the donation of tmexCD1-toprJ1 cluster to the recipient K. pneumoniae, dependent of the conserved Tn5393-aided transposal events31. Given the observation that the tmexCD2-toprJ2 variant cooccurs with two carbapenemases-encoding loci (blaKPC-2 and blaNDM-1) in a single Raoultella ornithinolytica clinical isolate35, it is reasonable to ask whether or not tmexCD1-toprJ1-positive plasmid converges to the hypervirulent ST11 CRKP (or recalcitrant CRPA99) clones with KPC2 carbapenem resistance100,101,102. This seemed likely to produce a superbug that can be ultimately insusceptible to antimicrobial therapies available thus far. Therefore, it is prioritized to develop the next-generation of lead compounds/inhibitors targeting TMexCD1-TOprJ1 efflux pump. In light of the impaired type II fatty acid (FAS II)/biotin synthesis pathways bypassing MCR colistin resistance103,104, the combination of advanced lead compounds with some FAS II inhibitor (e.g., cerulenin/FabF and MAC13772/BioA) represents a promising strategy to combat against the deadly superbugs104,105,106.

Methods

Bacterial strains ad growth conditions

Two types of bacterial strains were used in this study, namely (i) the derivatives of Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae), and (ii) a variety of Escherichia coli (E. coli) mutants (Table S2). Unlike the strain K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816 that is susceptible to tigecycline107, the multidrug-resistant isolate AH8I of K. pneumoniae harbored a plasmid-borne tmexCD1-toprJ1 cluster (Table S2), producing tigecycline resistance22. The E. coli DH5α strain acted as a bacterial host for recombinant plasmid amplification, whereas the BL21 strain was used for both protein overexpression and functional analyses of varied TMexCD1-TOprJ1 variants. In addition to the parental BL21(DE3) strain, its isogenic ΔacrB mutant (termed as FYJ8002) that is devoid of AcrB transporter was also utilized to analyze the varied MIC values of tigecycline (Table S2). All the resultant strains we generated here, were maintained on Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37 °C. Since the carriage of pBAD24::tmexCD1-toprJ1 derivatives, ampicillin (100 μg/ml) was routinely required for the majority of engineered BL21 strains. Whereas kanamycin (50 μg/ml) was added for the selection of BL21 colonies that contained pET28 derivatives.

Plasmids and genetic manipulations

The plasmid pHNANH8I-1 of K. pneumoniae served as a DNA template to amplify the components of tmexCD1-toprJ1 gene cluster22. To prepare an individual subunit in vitro, the three loci of tmexC1, tmexD1, and toprJ1 were directly inserted into the pET28 expression vector with a C-terminal hexa-histidine (6x His) tag, producing pET21::tmexC1, pET28::tmexD1, and pET28::toprJ1, respectively (Tabel S1). To address the interplay between TMexC1 and TMexD1, a binary plasmid system was designed here, which was composed of pBAD24::tmexC1, a tag-free recombinant plasmid, in combination with pET28::tmexD1 having a 6x His tag at C-terminus. Notably, a single plasmid system of pBAD24::tmexCD1-toprJ1 was developed, aiming at preparation for the whole complex of a tripartite TMexCD1-TOprJ1 machinery. In brief, the acquired tmexC1 gene was attached with a Strep-tag at the 3’-end via a pair of specific primers (Table S3). Similarly, the tmexD1-toprJ1 locus was engineered to carry a 6x His tag, rather than a Strep-tag at the 3’-end. As described with the in vitro synthesis of MCR-4108,109, an overlapping PCR was conducted to assemble the two DNA fragments, leading to a full-length tmexCD1-toprJ1 cluster (Fig. S9). Ultimately, the use of a homologous recombination strategy allowed the integration of this fusion fragment into pBAD24 vector, yielding a single expression plasmid pBAD24::tmexCD1-toprJ1 (Table S2). To functionally characterize the individual module of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 efflux pump, pBAD24::tmexCD1-toprJ1 was subjected to structure-guided, site-directed mutagenesis by using PrimeSTAR® GXL DNA Polymerase (Takara, Japan). It was noted that DpnI treatment proceeds to remove the contamination of trace template plasmid as recently described with the AasS acyl-ACP synthetase110,111. As a result, this gave in a total of 85 plasmid-borne mutants (Table S2). Namely, they included (i) 55 single-point mutants (i.e., 8 for TOprJ1, 18 for TMexC1, and 29 for TMexD1), (ii) 8 double-point mutations (2 for TOprJ1, 2 for TMexC1, and 4 for TMexD1), and (iii) 22 combinational mutations (9 for TOprJ1/TMexC1 pair, and 13 for TMexC1/TMexD1 set). Following the confirmation with direct DNA sequencing, all the constructs were introduced into BL21(DE3) strain and/or its ΔacrB derivative that were dedicated to subsequent protein production and/or functional assays.

Protein expression and purification

Unlike TMexC1 that is a periplasmic protein, TOprJ1 and TMexD1 are an outer-membrane protein, and an integral inner-membrane protein, respectively. All the three components were individually prepared. Because of relatively-acidic environment in periplasm, the optimized buffer for TMexC1 preparation was composed of 25 mM MES (pH5.5), 300 mM NaCl, and 5% glycerol. In addition to the bipartite complex of TMexC1-TMexD1, the fully-assembled tripartite complex of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 was isolated. In general, 1 liter of bacterial culture was induced for around 3 h at 37 °C, upon the arrival of mid-log phase (i.e., optical density at 600 nm (OD600) = ~0.8). It was noted that different from 0.2 mM Isopropyl β-D-Thiogalactoside (IPTG) as an inducer for pET28-based derivatives, 0.2% arabinose was added to trigger pBAD24-based protein expression. To obtain an intact tripartite complex of TMexCD1-TOprJ1, a unique purification procedure was established (Fig. S10), which largely relied on two affinity tags (Strep-tag and 6x his tag) attached to this efflux pump (Fig. 2a).

In brief, bacterial pellets of the strain FYJ5950 (i.e., BL21 carrying pBAD24::tmexCD1-toprJ1) were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer, resuspended in a lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 300 mM NaCl) at a volume ratio (30 ml of buffer vs. 5 ml of pelleted cell), and disrupted with high-pressure homogenizer/French press (JINBOR Mini, Guangzhou Juneng Nano & Biotech Co. Ltd.) at 1200 MPa. As earlier described with MCR-1/2112,113 and its ancestry version ICR-Mo114 with a little change, the resultant cell lysate was subjected to the 1 h of ultra-centrifugation at 38,000 rpm, which yielded bacterial cell membrane fraction-containing pellets. The solubilized cell membranes in a buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, and 1% DDM) proceeded to the 30 min of centrifugation at 13,000 rpm, eliminating the residual cell debris. Since the clarified supernatant that presumably contained TMexCD1-TOprJ1 efflux pump, it was incubated with Strep-beads (IBA Lifesciences, Germany) by gentle inversion at 4 °C for 1 h, and then loaded into a gravity column. After the removal of contaminated proteins with three column volumes of washing buffer 1 (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, and 0.03% DDM), the protein mixtures of interest then were eluted using a single column volume of elution buffer 1 (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 0.03% DDM, and 2.5 mM dethiobiotin). Because of TMexC1 protein in a Strep-tagged form, this step of affinity purification was supposed to isolate the mixture of TMexC1 alone, two sub-complexes of TMexC1-TMexD1 and TMexC1-TOprJ1, and the fully-assembled complex of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 (Fig. S10).

Next, the initial elutes were subjected to the second round of affinity purification with nickel beads. This step was solely based on 6x His tag of TOprJ1. Thus, only TMexCD1-TOprJ1 complex remained bound by the nickel beads on gravity column, after extensive wash with washing buffer 2 (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 0.03% DDM, and 20 mM imidazole), which presumably removed those weakly-bound proteins (esp., TMexC1 and TMexC1-TMexD1). The target protein sample eluted with a buffer containing 150 mM imidazole was confirmed with SDS-PAGE (12%). Following the concentration with an Amico® Ultra tube (100 kDa cutoff, Millipore-Sigma, USA), the acquired protein sample was dialyzed in size exclusion (SEC) buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 0.03% GDN). Finally, gel filtration assays were performed using an AKTA pureTM chromatography system with a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column (Cytiva, USA). As a result, appropriate fractions collected from the interested peaks, were validated with SDS-PAGE (12%). The correctly-assembled complex was suitable for further cryo-EM structural exploration.

Assays for cytosolic tigecycline accumulation

The ability of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 system to expel tigecycline was evaluated by direct assaying the level of intracellular tigecycline with two sets of approaches. Unlike the semi-quantitative spectrophotometric method that is dependent on absorbance at a wavelength of 400 nm26, the latter one exploited high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for precise quantification115,116. As for the two methods, the establishment of calibration curves was a prerequisite for antibiotic measurement. In the spectrophotometric assay, the calibration curve was generated by plotting varied tigecycline levels (from 50, 100, 125, to 200 μg/ml) against their equivalent values of OD400. In the HPLC assays, the peak squares of tigecycline standards (ranging from 1, 10, to 100 μg/ml) were plotted versus their concentrations115. The HPLC mobile phase denoted acetonitrile: phosphate buffer (25:75 (vol/vol); pH 3.0, 0.023 M) and the UV detector was set at 244 nm.

In general, 50 ml of log-phased cultures of the ΔacrB strain and its derivative carrying pBAD24::tmexCD1-toprJ1 were subjected to the measurement for intracellular tigecycline accumulation115,116. After three rounds of wash with ice cold PBS, cell pellets were suspended in 10 ml of PBS, and kept at 37 °C for 30 mins to assure expression of TMexCD1-TOprJ1 efflux pump. Upon the supplementation of exogenous at final level of 100 μg/ml, the bacterial mixture was incubated for an additional hour at 37 °C. To remove extracellular tigecycline, the pelleted cells were washed three times with PBS. Meanwhile, bacterial wet mass was weighed. Prior to 3 h of shaking at room temperature, the resultant pellets were resuspended in 2 ml of lysis buffer (0.1 M glycine hydrochloride, pH 3.0), leading to cell lysis. Following the centrifugation of bacterial lysates at 12,000 rpm for 20 mins, the clarified supernatant was subjected to the filtration with a 0.22 μm filter. Finally, HPLC analysis was applied to determine the tigecycline concentration in the supernatants. The measurements were obtained from three independent trials. The unit of data was given as micrograms of tigecycline accumulated per gram wet weight (μg/g wet weight).

Measurement for tigecycline susceptibility