Abstract

Dance is an ancient, holistic art form practiced worldwide throughout human history. Although it offers a window into cognition, emotion, and cross‑modal processing, fine‑grained quantitative accounts of how its diverse information is represented in the brain have rarely been performed. Here, we relate features from a cross‑modal deep generative model of dance to functional magnetic resonance imaging responses while participants watched naturalistic dance clips. We demonstrate that cross-modal features explain dance‑evoked brain activity better than low‑level motion and audio features. Using encoding models as in silico simulators, we quantify how dances that elicit different emotions yield distinct neural patterns. While expert dancers’ brain activity is more broadly explained by dance features than that of novices, experts exhibit greater individual variability. Our approach links cross-modal representations from generative models to naturalistic neuroimaging, clarifying how motion, music, and expertise jointly shape aesthetic and emotional experience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Naturalistic neuroimaging studies, such as those where participants watch natural scenes or listen to stories during recording, seek to understand how the human brain operates in real-world contexts, rather than under the highly controlled yet often artificial conditions typical of traditional experiments1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. However, many studies still rely on unimodal stimuli, such as natural scenes presented without sound, or sounds without accompanying visuals. In contrast, everyday experiences seamlessly integrate multiple sensory streams, highlighting the importance of investigating multimodal environments12.

To address this gap, the present study focuses on dance, which inherently fuses dynamic bodily movement with rhythmic music and thus offers an especially rich, cross-modal stimulus. Dance provides an embodied, emotionally expressive setting that integrates visual and auditory cues, reflecting real-life music–movement interactions13,14,15,16,17. Street dance, in particular, tightly couples beats and motion, and the recent availability of large-scale, richly annotated databases18 supports extended experiments linking brain activity to detailed motion–music features.

Despite growing interest in the neuroscience of dance, several limitations remain. Some previous studies examined dancers’ cognitive or neural functions without incorporating actual dance stimuli19,20,21,22,23, while others employed highly controlled or artificial stimuli24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, such as biological motion or isolated movement or pose presented without audio, potentially compromising ecological validity32. Even in studies employing naturalistic dance clips, quantitative analyses have typically been limited to coarse, clip‑level metrics33,34,35,36,37,38,39—for example, stimulus‑level audio‑vs‑visual contrasts39 or whole‑brain inter‑subject correlation38—thus providing only limited insight into how moment‑to‑moment motion, music, and their interaction jointly shape neural activity. Typically, these studies used coarse or binary descriptors (e.g., “dance video vs. non-dance video,” “matched vs. unmatched audio–motion”) that, while interpretable, fail to capture the fine-grained, high-dimensional interactions that are characteristic of complex dance. Moreover, although differences between expert and novice dancers have been explored19,20,23,24,27,28,29,30,31,35,40,41, these investigations typically focused on isolated aspects of dance, failing to fully leverage the holistic, cross-modal character of real-world dance performances. Another important issue is that these findings were derived independently from multiple dance studies, with each modeling approach operating in isolation. This makes it difficult to directly and quantitatively compare both how and to what extent the features investigated in each study are represented in the brain during the viewing of a single dance video clip.

In recent years, neuroscience has benefited from advances in AI-based naturalistic modeling, spurring new approaches to modeling brain activity3,4,5,11. These developments are partly driven by methodological breakthroughs in generative AI. Notably, the quantitative encoding models adopted in these studies enable comparisons of how different types of features are represented in the brain, marking a significant leap beyond traditional frameworks. In the field of dance, various generative models have also been introduced42,43, but it remains unclear how closely they mirror actual human cognition. In particular, recent state-of-the-art models (Editable Dance GEneration: EDGE43) predict the next movement based on prior sequences of audio and motion in a way that appears to align with human cognition, suggesting these models approximate real dance performance quite closely44— underscoring the importance of validating them.

Here, we address these gaps by fusing naturalistic dance stimuli with a cross-modal deep generative model (EDGE)43 and a voxel-wise encoding model6,7,45. Specifically, we recorded brain responses from 14 participants (including expert dancers) as they watched a diverse collection of both street and jazz dance clips18. This setup enables us to quantitatively dissect how unimodal versus cross-modal features of dance explain brain activity, and how dance expertise influences these representations. We focus on three central questions: (1) How and to what extent does the human brain represent cross-modal dance features compared to the traditional unimodal features? (2) How does dance expertise influence these neural representations? and (3) How do different dance clips evoke specific patterns of brain activity, and how are these patterns related to viewers’ emotional experiences? By leveraging Transformer-based joint motion–audio embeddings, we aim to capture the fine-grained, high-dimensional relationships in dance that coarse or binary descriptors may overlook.

Results

We conducted an fMRI experiment with 14 participants who watched five hours of naturalistic dance clips. Seven participants were experts with more than five years of dance experience, whereas the remaining seven were novices with no formal dance training. We use a set of 1,163 clips from the publicly available AIST Dance DB18 as stimuli. These clips featured performances by 30 dancers executing various choreographies to 60 pieces of music spanning 10 genres (e.g., pop, lock, waack, and ballet jazz). For further details on participants and stimuli, see the Methods.

In this study, we model the dance clips using features derived from EDGE (see Fig. 1a and Methods for details on feature extraction). EDGE generates subsequent naturalistic dance motions based on past dance motions as well as aligned audio features extracted from a latent representation of a deep learning model46. Many deep generative models that employ such predictive mechanisms in the language, image, and audio domains not only model stimuli more effectively than conventional features across various tasks but also correspond more closely to human brain activity3,4,5,11. More broadly, predictive processing is regarded as one of the most fundamental human cognitive processes44. Based on this, we hypothesize that EDGE leverages feature embeddings that are also informative for human observers, such that its cross‑modal features may explain neural responses during dance viewing more effectively than low-level motion and audio features. Specifically, EDGE integrates motion and audio features through seven transformer layers with a cross-attention mechanism, which serve as latent representations of cross-modal features. Using these features, we construct whole-brain voxel-wise encoding models (Fig. 1b).

a Overview of the deep generative dance model (EDGE). EDGE integrates motion and audio inputs to generate cross-modal features. Motion is represented as 72-dimensional 3D joint locations estimated by a machine learning model from nine synchronized video cameras. Audio features are derived from the latent representation of a deep learning model for music. Cross-modal features are obtained from transformer layers that fuse motion and audio features to predict subsequent motion. The generative model was trained to optimize next-motion prediction. b Overview of the experiment and encoding model building. We use fMRI to record the participants’ blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) responses while they watched five hours of naturalistic dance clips. Each feature (XAudio, XMotion, and XCross-modal) is extracted from each time point in each dance clip and resampled to the BOLD signal rate (1 Hz) to construct feature matrices. Voxel-wise encoding models are built using L2-regularized linear regression (ridge regression) to predict BOLD signals from the feature matrix. To predict the BOLD signal, the weights of the constructed model are multiplied by the test data features. The illustration of a human brain was created by the authors. The dance images are taken from the AIST Dance DB18 and used with permission from the license holder.

Cross-modal features predict brain activity across cortex

Figure 2a shows the prediction performance of stacked ridge regression47 using motion, audio, and cross-modal features simultaneously in a single participant. Stacked ridge regression is a unified encoding approach that integrates predictions from multiple feature spaces by optimally weighting their contributions through cross-validation (see Methods for details on stacked ridge regression). In this study, cross-modal features refer to CM5 (6th cross-modal layer), which yielded the highest average prediction performance across participants. These results demonstrate that motion, audio, and cross-modal features derived from naturalistic dance clips predict activity across multiple brain regions, including lower visual and higher visual areas as well as auditory cortex (P < 0.05, FDR corrected). Using brain activation estimated by the encoding model for cross-modal feature, we identify the dance clips that elicit the strongest activity in each brain region among all dance clips. These results indicate that different cortical regions are selectively responsive to different dance types (see Fig. 2a for examples of dances). Supplementary Fig. 1 presents the results for all participants. Figure 2b and 2c show the prediction performance of each feature for a single participant and the results for each region of interest (ROI)48, respectively. These results indicate that the cross-modal features (CM0 to CM7) explain brain activity in the higher visual cortex (anterior occipital sulcus) more effectively than low-level sensory features such as motion or audio (see Supplementary Figs. 2–5 for results across all ROIs). Detailed voxel-level prediction maps for all features and participants are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1. Furthermore, auditory features show high prediction performance in the auditory cortex (transverse temporal sulcus), while parieto-occipital regions such as the superior temporal sulcus (STS) equally represent a wide range of information. To address concerns about circularity—namely, potential overlap between the model’s training data and the stimuli used in the fMRI experiment—we retrained EDGE using only the training stimulus set used in the fMRI experiment. We confirm that the overall prediction trends remained consistent, indicating no compromise to our results (see “Effect of training dataset of EDGE,” in Methods and Supplementary Fig. 19).

a Prediction performance for a single participant (Sub001; novice dancer) measured by Pearson’s correlation coefficients (R) between predicted and actual BOLD responses. Responses are evaluated with a voxel-wise encoding model on held-out test clips, using three dance-related feature spaces (motion, audio, and cross-modal [CM5]) within a stacked ridge regression framework. Shown are the inflated (four corners) and flattened (center panel, centered on the occipital lobe) cortical surfaces of both hemispheres. Colored brain regions indicate significant prediction accuracy (all colored voxels: P < 0.05, FDR corrected). White boxes mark anatomically defined representative regions of interest (ROIs), selected based on known involvement in visual (e.g., occipital regions), auditory (e.g., transverse temporal sulcus), and broader cognitive functions (e.g., precuneus). Pie charts show the distribution of the top 1% of dance genres that most strongly activate each ROI, and one representative dance clip from the most frequent genre within this top 1% is shown for each ROI. All dances flow from left to right. See Supplementary Figs. 7–14 for all ROIs. RH, right hemisphere; LH, left hemisphere; IPS, intraparietal sulcus; STG, superior temporal gyrus; FFG, fusiform gyrus; STS, superior temporal sulcus. The dance images are taken from the AIST Dance DB18 and used with permission from the license holder. b Prediction performance for each individual feature space: motion, audio, and cross-modal (CM5) features. c Averaged prediction performance across participants. ROI averages across participants are superimposed on the flatmap of Sub001. ROIs with average R < 0.01 are omitted for visual clarity. Note that the R values in this panel span a different numerical range from those in b. For clarity, each panel keeps its own color scale, and the exact minimum and maximum values are printed beside the color bar. d Prediction performances of individual feature space across participants in four representative ROIs from the left hemisphere. Boxes span the 25th–75th percentiles, and the center line marks the median (50th percentile). Whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values that are not considered outliers—no farther than 1.5 times this range from the 25th and 75th percentiles—and points beyond are outliers. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Unique contributions of each dance-related feature

Next, we investigate the unique contributions of each feature to brain activity. We investigate the α values from stacked ridge regression, which represent the estimated parameters indicating how each feature contributes to prediction performance (see Methods for details on stacked ridge regression). Unlike the previous analysis, this analysis builds a unified encoding model incorporating all features simultaneously. This enables explicit consideration of the correlational structure among features and allows identification of their unique contributions. Figure 3a–c present results for a single participant (Sub001), while Fig. 3d–f show averaged α values across all participants for representative ROIs. Motion features exhibited distinctive representations, primarily within the visual cortex and dorsal visual areas, while ventral visual and auditory cortex robustly represent audio features. Notably, cross-modal features have larger contributions than other features, mainly in the intraparietal sulcus (IPS), precuneus, and STS, all high-level associative brain regions. Supplementary Fig. 6 presents results for all participants.

a–c Stacked regression results for a single participant (Sub001) displayed on flattened cortical surfaces, showing the spatial distribution of each feature’s contribution (α, the estimated weight of stacked regression). For visualization purposes, voxels with the top 10,000 prediction accuracy in the full model (Fig. 2a) are colored. d–f Averaged α values across participants for the three feature spaces in representative ROIs. For visualization purposes, only ROIs with at least 12.5% significant voxels are colored. Note that α‑weights in these panels span a different numerical range from those in (a–c). For clarity, each panel keeps its own color scale, and the exact minimum and maximum values are printed beside the color bar. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In silico mapping of dance concepts onto brain

While dance can evoke a wide array of concepts in the human mind, the underlying phenomenon in our brain remains elusive. To advance our understanding of cross-modal information representations, we next examine which aspects of dance (e.g., aesthetic appreciation and dynamics) elicit stronger brain responses. To this end, we conduct in silico simulations using our encoding model. Specifically, we calculate cross-modal features for all dance clips and estimate whole-brain activation based on these features (Fig. 2a shows examples of the most activating dance clips for different ROIs in a single participant). To interpret which aspects of dance activate the brain, we labeled the dance clips using 42 concepts (Fig. 4a). These consist of 34 basic concepts49, six dance-related descriptors provided by expert dancers (see Methods), and two general ratings (likability and technical proficiency). We incorporate multiple rating scales because emotional experiences are multifaceted rather than reducible to a few dimensions49. Subsequently, we conducted an online experiment in which approximately 250 participants rated the concepts evoked by the dance clips. We include only the responses from participants who correctly answered all attention-check trials, where they were asked to indicate what the dancers were wearing, resulting in a final sample of 166 participants. On average, seven participants rated for each dance clip. While clips in the same dance genre share similar characteristics, we observe substantial diversity across clips (Supplementary Fig. 17 provides an overall summary). Note that the concepts reported by participants reflect the perceived or expressed emotional content of the dance clips, rather than their own felt emotion. In other words, participants’ ratings may represent the emotion they believe the dancer intended to convey, their personally experienced emotion, or a combination of both (see Collection of concept ratings for dance clips from fMRI participants in Methods for further discussion).

a Each dance clip received a rating based on 42 concepts. After watching each dance clip, the crowd-sourced raters reported 34 basic concepts and six dance-related concepts that came to mind. Each rater also rated each dance clip on a scale of 1–9 for more general concepts of ‘like’ and ‘technique’. b Schematic figure describing the method for calculating the correlation between the degree of brain activity induced by each dance clip, as estimated by cross-modal features, and the rating of concept assigned to each dance. c–e ROIs indicating significant positive (red) or negative (blue) correlations on the cortex of a single participant (Sub001) for three representative concepts. f–h Number of participants showing significant positive (red; left) or negative (blue; right) correlations in each ROI for three representative concepts presented in Fig. 4c–f. i Concepts significantly correlated with activity in the left anterior occipital sulcus in one participant (Sub001). Only significant correlations are shown (P < 0.05; 10,000 times permutation test). mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We then examine how the concept ratings for each dance clip relate to the magnitude of brain activity (Fig. 4b). We extract cross-modal features for all non-overlapping motion sequences derived from dance clips within AIST Dance DB (N = 18,109 sequences from 1408 dance clips). For each participant, we multiply these features by the encoding weights to estimate whole-brain activity. Correlations between the estimated activity and the 42 concepts are then computed voxel-wise, and voxel values within each ROI are averaged to yield a single correlation coefficient per ROI. Statistical significance is assessed by generating null distribution of correlation coefficients obtained from randomly shuffled activation and concept, repeated 10,000 times. After performing family-wise error correction, we identify concepts showing significantly positive or negative correlations. This process is repeated for each participant and each ROI.

In Fig. 4c–e, we present correlations between brain regions and three concepts for an example participant (Sub001): Aesthetic Appreciation, Dynamics, and Boredom (P < 0.05, 10,000 times permutation test; see Methods for details on significance testing). Aesthetic Appreciation shows strong correlations with both low- and high-level visual regions, whereas the other concepts are primarily associated with low-level visual regions. Supplementary Fig. 15 presents results for all participants. Figure 4f–h show group-level results, with positive correlations for Dynamics and negative correlations for Boredom in regions such as the precuneus and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), key components of the default mode network. Figure 4i illustrates concepts significantly correlated within a single ROI (anterior occipital sulcus) for Sub001, and Supplementary Fig. 16 shows results for all concepts. Among all significant effects, Dynamics exhibited the largest positive R value, whereas Boredom exhibited the strongest negative R value. Supplementary Table 1 summarizes the percentage of ROIs showing significant correlations for each concept, indicating that Dynamics, Boredom, and Aesthetic Appreciation are the most frequently associated with the brain activity.

Model-based comparison between expert and novice dancers

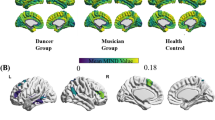

After developing models to elucidate and interpret brain activity during dance observation, we examine whether these models can shed light on differences between expert dancers and novices, as reported in prior studies. To this end, we first compare the number of significant voxels across the whole brain. Figure 5a shows the number of significant voxels in the analyses of the encoding models across whole brain, calculated for each feature in both groups. Expert dancers tend to exhibit a higher number of significant voxels, particularly for motion features (U = 8, P = 0.038 for motion feature, two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test, uncorrected). However, no significant differences are observed for music features, indicating that the previously reported disparities between experts and novices stem from specific computational processes rather than the overall differences for all features. To further investigate these group differences, we next examine the similarity of activation patterns across dance clips among participants (Fig. 5b). Figure 5c depicts correlations between participants in estimated brain activity induced by cross-modal features across dance clips for each ROI. Expert dancers exhibit lower similarity in brain responses among themselves compared to novices (P < 0.001, 1000 times permutation test). Finally, we compare the percentage of concepts showing significant correlations across all ROIs for each concept between the two groups, and observe that the two groups generally followed the same trend (Pearson’s R across 42 concepts = 0.89), although the correlations were slightly lower among expert dancers (0.052 ± 0.042 for novices and 0.042 ± 0.052 for experts; see Supplementary Table 1).

a Comparison of expert dancers and novice participants in the number of significant voxels across the cortex for each feature. Data show means and ± s.e.m. across participants. *U = 8.0, P = 0.038, two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test, uncorrected. b Correlations of estimated evoked activation patterns by dance stimuli are calculated separately for expert and novice dancers. c Results for the correlations of estimated evoked activation patterns in each representative ROI, shown separately for expert dancers (N = 7; top) and novices (N = 7; bottom). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

This study investigates how the diverse information inherent in dance is represented across regions of the human brain. To this end, we employ whole-brain voxel-wise encoding models in combination with a deep generative dance model. Our findings indicate that cross-modal information processing within the generative model elucidates brain activity during dance viewing more effectively than low-level sensory features.

This study maps motion, audio, and cross-modal features onto brain activity using a cross-modal deep generative model. Our work overlaps with prior literature in identifying well-established regions associated with motion and audio processing; however, our main contribution lies in extending these findings to naturalistic dance stimuli—an approach increasingly recognized for capturing the complexity of real-world perception1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. By employing an encoding model that directly compares unimodal (motion, audio) and cross-modal components, we reveal how these features are represented across brain regions. In many areas (e.g., higher visual cortex and STS), cross-modal features outperform unimodal features in predicting brain activity, although not all subregions of traditionally cross-modal regions (e.g., IPS and prefrontal cortex) are equally well captured (Fig. 2d). These differences are not binary but lie on a continuum, illustrating the fine-grained nature of cross-modal integration. This quantitative approach provides insights beyond those provided by earlier methods. Notably, because dance is an art of coordinating body motion and music, our results show that brain activity corresponding to these cross-modal features emerges across broad regions of the occipital, parietal, and temporal lobes (Fig. 3c).

The deep generative model used here, particularly its cross-modal features, robustly predicts human brain activity during dance viewing. This finding suggests that the model’s next-motion prediction architecture aligns well with human cognition. Although previous studies in other sensory domains have examined similar approaches1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, no prior work has explicitly used motion–audio stimuli—a cross-modal input central to human cognition—and compared the model’s alignment with human brain activity. From a NeuroAI perspective50, our study provides a unique contribution by testing the internal representations of a cross-modal deep generative model against human brain data, revealing parallels between how biological and artificial systems process and integrate audiovisual information. Thus, our findings highlight the potential of AI architectures to align with human neural processing, particularly in predictive and multimodal contexts. We note that, however, we do not claim that EDGE is the ultimate solution for explaining neural processing during dance observation. While EDGE currently offers one of the best generative frameworks for predicting realistic dance motions, models that integrate higher-level musical structure (e.g., rhythmic or melodic analysis), choreographic style, and individual dancer differences may more accurately account for how the brain processes dance. Future comparisons with alternative models will further deepen our understanding of these underlying neural mechanisms.

Our overarching aim is to clarify how cross-modal (auditory and visual) features of dance map onto brain activity and subjective emotional experiences. Guided by evidence that emotions cannot be fully captured by a limited set of dimensions49, we employed multiple rating scales (e.g., excitement, enjoyment, tension, and boredom) to identify which emotional factors best explain neural variability and whether expertise influences emotional engagement with dance. The results reveal that dynamics, boredom, and aesthetic appreciation are strongly correlated with predicted brain activity, particularly in default mode network regions (precuneus and mPFC), where greater activation corresponded to stronger perceived dynamics and reduced activation to boredom. Aesthetic appreciation is linked to both low- and high-level visual areas, implying that evaluative processes interplay with basic perception during dance observation. These findings highlight the value of multifaceted emotional ratings for capturing the fine-grained ways in which dance engages the brain, emphasizing the importance of moving beyond simple sensory or motor descriptions to understand how viewers integrate cross-modal information with subjective interpretation.

Numerous studies have reported differences in brain activity between expert dancers and novices during dance viewing19,20,23,24,27,28,29,30,31,35,40,41. Here, we identify specific differences in information processing between these groups, which may underlie previously reported disparities that did not explicitly model each sensory feature: (1) the groups differ in the degree of motion and cross-modal processing of dance elements (Fig. 5a); (2) expert dancers show less similarity among themselves compared to novices (Fig. 5c); and (3) both groups exhibit comparable relationships between dance-elicited emotions and brain activity (Supplementary Table 1). Although experts come from various dance genres, it is not necessarily clear that this diversity would result in increased variability. For example, one could equally predict that their shared level of expertise would produce more similar responses than those of novices. In fact, our findings reveal that experts exhibit consistently high predictability in neural activation, yet display diverse relationships between brain activity and the emotional dimensions of dance—underscoring a fine-grained form of variability. These results highlight the importance of modeling brain activity at the individual level, as done in our approach.

In this study, we build a model that captures how dance features relate to brain activity (i.e., an in silico simulator), enabling us to characterize how various concepts are represented in the brain during dance observation. As a proof-of-concept application of our in silico simulator, we explore whether this simulator could generate novel, artificial dance stimuli that modulate predicted neural activity across the brain (see “In silico simulation of motion–music pairings” in Methods for details). Specifically, for each motion sequence from the AIST Dance DB, we generate 10 ‘artificial clips’ by pairing it with music from 10 different genres (excluding the original pairing). These clips are then fed into our simulator to predict neural responses, which are compared against those predicted for the original paired clips. (Fig. 6a and 6b). Consistent across participants, real motion–music pairings strongly engage sensory-associated regions (e.g., visual cortices), whereas artificially paired dances tend to produce relatively higher activation in more frontal areas (Fig. 6c). These findings suggest that different cortical regions may be differentially sensitive to natural versus incongruent motion–music pairings, potentially reflecting processes such as prediction error or perceived incongruence51. Although our in silico simulator can, in principle, generate unique combinations of motion and music for both novice and expert participants, our preliminary analysis revealed no clear group differences in this setting, highlighting the complexity of defining and interpreting expertise-based effects. Overall, while these results remain exploratory, they illustrate the potential of using custom-designed motion–music stimuli to manipulate neural activity patterns in future research.

a Overview of the framework for estimating induced brain activity by artificial motion-music pairings. Cross-modal features are computed from original motion-music pairings and used to estimate induced brain activity. The same estimation is performed using artificial motion-music pairings, created by pairing the original motion with randomly selected music tracks (excluding the original). b Example of estimated brain activity for a specific brain region (anterior occipital sulcus) of a single participant (Sub001) while watching a specific dance clip (Waack clip with music WA4). Jazz ballet music (JB0) suppresses activity compared to the original music, while lock music (LO4) enhances it. The dance images are taken from the AIST Dance DB18 and used with permission from the license holder. BR break, PO pop, LO lock, WA waack, MH middle hip-hop, HO house, KR krump, JS street jazz, JB ballet jazz. c Flattened cortical maps showing the percentage of participants whose mean activity for artificial motion-music pairings is significantly different (positive, top; negative, bottom) from that for the original pairings. RH right hemisphere, LH left hemisphere. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Our study has several limitations. First, our stimuli primarily feature street dance, where movement and music are tightly coupled. While the AIST Dance DB spans ten genres (including jazz dances) and provides unprecedented detail (e.g., nine-camera motion capture), further studies are required to confirm whether our findings extend to other dance forms with looser coupling or distinct choreographic structures, and EDGE may require adaptation for alternative styles. Second, although our fMRI protocol follows standard practices—one-hour sessions with frequent breaks to minimize fatigue—and our crowdsourced participants for concept ratings completed shorter sessions (60 clips each), the fMRI experiment (i.e., viewing multiple dance clips in the scanner) still poses concerns about ecological validity. Nonetheless, a supplementary experiment with a subset of fMRI participants showed no systematic increase in boredom or fatigue, suggesting that session length did not critically bias the results (see “Collection of concept ratings for dance clips from fMRI participants” in Methods for further discussion). Third, because the AIST Dance DB was developed by an external group, our fMRI participants were recruited from a separate pool of dancers. Scanning dancers while they view their own recorded performances could yield novel insights into self-perception, embodiment, and neural engagement during dance; however, creating and analyzing such a dataset are beyond the scope of the present study. Future investigations comparing individuals’ responses to their own versus others’ performances may further elucidate how personal experience modulates dance perception and emotion.

Beyond neuroscience, our results intersect with a range of dance‑focused discussions. As EDGE generates the next natural dance motion based on past motions and audio features, the cross-modal features extracted from EDGE reflect essential functions required for choreography. Therefore, mapping these features onto the brain marks an initial step towards neuroscientific understanding of the cognitive processes involved in creating and perceiving choreography52. In terms of practical application, combining our in silico simulator with AI‑supported choreographic tools53 could provide externalized representations of choreographic thinking, consistent with computational views of external representations54 within eco-computational systems for choreographic creations. It also responds to the recent calls for mechanistic neural accounts of dance55. Collectively, these links situate our work at the nexus of neuroscience, dance studies, and multimodal generative AI, and highlight the potential of joint motion–music modelling to inform both theory and creative practice. Incorporating choreographic hierarchies, semantic cues, and individual dancer characteristics into future models may further reveal how stylistically varied performances are processed in the brain. Although the present study focuses on dance observation, naturalistic performance remains essential for a holistic view. Methodological challenges—most notably, head‑motion artifacts that arise when dancers move during brain recordings—persist; nevertheless, the partial overlap among brain regions recruited by dance execution, observation, and imagery56 suggests that the current results provide a solid foundation for understanding both watching and performing of dance.

Methods

Participants

The present investigation involves 14 participants (Sub01–Sub14), aged 22–33 years, including three females and 11 males. The participants include seven expert dancers (two females) and seven novices (one female) with normal or corrected-to-normal vision and hearing. This sample size is chosen based on previous fMRI studies with similar experimental designs7. Experts are defined as those with ≥5 years of dance experience outside compulsory education, while novices are defined as those without dance experience outside compulsory education. While all experts are versed in street dance in general, each is particularly skilled in a particular genre (e.g., ballet, break, hip-hop, waack, and street jazz). The Ethics and Safety Committee of the University of Tokyo (Japan) approved this study. All participants provided written informed consent before participation.

Stimuli and experimental procedure

We use the AIST Dance DB18 as the stimulus. The AIST Dance DB contains approximately 13900 clips categorized into four main categories:

-

1.

Basic Dance includes 10800 clips (3 dancers × 10 motion patterns × 4 dance types [intense, loose, hard, and soft] × 9 camera views × 10 genres) where dancers perform according to four predetermined types of motion patterns per genre.

-

2.

Advanced Dance includes 1890 clips (3 dancers × 7 motion patterns × 9 camera views × 10 genres). In these clips, the dances are longer and more complex than Basic Dance.

-

3.

Group Dance includes 900 clips (10 dances × 9 camera views × 10 genres). In this video, dancers perform in a group.

-

4.

Moving Camera includes 300 clips (10 dances × 3 camera views × 10 genres) acquired with a moving camera.

The AIST Dance DB encompasses 10 dance genres, ranging from old-school (1970s–1990s: break, pop, lock, and waack) to new-school (after 1990: LA-style hip-hop, middle hip-hop, house, krump, street jazz, and ballet jazz). A minimum of five years of dance experience is required for all dancers. Note that our fMRI participants were recruited from a separate pool of dancers in the AIST Dance DB. While all videos were recorded in full color, many dancers opted for monotone attire when asked to choose their outfit.

The present study uses front-camera-filmed Basic and Advanced dance clips as fMRI stimuli. Basic dance clips last 7–13 s, while Advanced clips last 28–48 s. Dance clips have a pace of 80–130 BPM, apart from the house genre, which runs at 110–135 BPM. The fMRI experiment consists of 21 training runs and five test runs. The training and test runs show training and test clips, respectively. Each run lasted 356–633 s. The training clips last 12,422 s, and the test clips 2860 s. No music track was shared between the training and test clips. Specifically, we include 940 clips in the training clips and 223 clips in the test clips. The Advanced Dance sessions contained 19, 18, 18, 18, 17, 16, 16, 15, 10, 10, and 6 clips, respectively. The Basic Dance sessions contained 71, 71, 70, 70, 70, 69, 66, 65, 65, 61, 59, 59, 59, 57, 57, and 37 clips, respectively. There was no interval between consecutive clips, and no clip was repeated. Training clips are used to build the whole-brain voxel-wise encoding models, and the test clips to verify prediction accuracy. We required participants to press a button when the same dancer presented in succession to maintain their attention and interest. We asked participants to view the dances as they would normally do.

MRI data acquisition

We conduct the experiments using a 64-channel head coil and a 3.0 T scanner (Prisma; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). We scan 72 interleaved axial slices 2.0 mm thick without gaps. These slices are placed parallel to the anterior and posterior commissure lines and had a repetition time (TR) of 1000 ms, an echo time (TE) of 30 ms, a flip angle (FA) of 60°, a resolution of 2 × 2 mm2, an MB factor of six, and a voxel size of 2 × 2 × 2 mm3. A magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo sequence (MPRAGE, TR = 2500 ms, TE = 2.18 ms, FA = 8°, FOV = 256 × 256 mm2, voxel size = 0.8 × 0.8 × 0.8 mm3) is used to acquire high-resolution T1-weighted images of the whole brain from all participants for anatomical reference. We use Freesurfer57 and PyCortex58 to flatten the brain surface and visually display it.

fMRI preprocessing

Each run underwent motion correction using the statistical parametric mapping toolkit (SPM12), developed by the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging in London, UK. Each participant’s volumes are aligned to the initial echo planar image. We apply a median filter with a window size of 120 s to eliminate low-frequency drift. Slice timing correction is applied to the first slice of each scan. To normalize the response for each voxel, we subtract the mean response and scaled the response to the unit variance. We employ Freesurfer to detect cortical surfaces based on anatomical data and align them with the voxels of the functional data. Only voxels located within each participant’s cerebral cortex were analyzed. We regress the dancer’s identity, motion pattern, and dance genre as covariates from preprocessed data estimated by training data and applied this to both training and test data. We use Destrieux atlas48 for defining the ROIs.

Feature extraction

We use EDGE43 to obtain cross-modal features. This model predicts future motion based on (i) past motion features and (ii) aligned audio features from a transformer-based diffusion model.

-

Motion feature: Motion data includes sequences of poses represented in the 24-joint SMPL format. We represent each joint using a six DOF rotation representation, with a single root translation: \({{{\bf{w}}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{24 \;*\; 6+3=147}\). Additionally, binary contact labels were employed to indicate the heel and toe of each foot \({{{\bf{b}}}}\in {\left\{{{\mathrm{0,1}}}\right\}}^{2 \;*\; 2=4}\). The total number of motion features is therefore \({{{\bf{x}}}}=\left\{{{{\bf{b}}}},{{{\bf{w}}}}\right\}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{4+147=151}\).

-

Audio feature: Audio features obtained from Jukebox, a GPT-style model46 trained on one million songs to generate raw music audio. Jukebox employs a hierarchical vector-quantized variational autoencoder to compress audio into latent representations with rich predictive properties. The dimensionality of the audio feature vector is 512.

-

Cross-modal feature: EDGE uses a diffusion-based framework to synthesize sequences of N frames, \({{{\bf{x}}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N \;*\; 151}\), given arbitrary music conditioning c. Following the DDPM59 definition, diffusion is defined as a Markov noising process with latent variables \({\{{{{{\bf{z}}}}}_{t}\}}_{t=0}^{T}\) that follows a forward noising process \(q\left({{{{\bf{z}}}}}_{t}|{{{\bf{x}}}}\right)\), where \({{{\bf{x}}}} \sim p({{{\bf{x}}}})\) is drawn from the data distribution. The forward noising process is defined as:

where \({\bar{\alpha }}_{t}\in (0,1)\) is a constant that follows a monotonically decreasing schedule such that when \({\bar{\alpha }}_{t}\) approaches 0, it can be approximated \({{{{\bf{z}}}}}_{T}{{{\boldsymbol{ \sim }}}}{{{\mathscr{N}}}}(0,{{{\bf{I}}}})\). With paired music conditioning c, EDGE reverses the forward diffusion process by learning to estimate \({\hat{{{{\bf{x}}}}}}_{\theta }({{{{\bf{z}}}}}_{t},{{{\bf{t}}}},{{{\bf{c}}}})\approx {{{\bf{x}}}}\) with model parameter θ for all t. EDGE optimizes θ with the “simple” objective introduced by59:

EDGE also introduces auxiliary losses to improve physical realism for joint positions, velocities, and foot velocities. Consequently, the weighted total of the auxiliary losses and the simple aim represents EDGE’s overall training loss:

where λs are hyperparameters. Classifier-free guiding was used to train EDGE60. EDGE employs a transformer decoder architecture to manage music conditioning, projecting it onto the transformer dimension through a cross-attention mechanism. For further details of the methodology, please refer to ref. 43. For the main analysis, the 6th cross-modal transformer layer is used as a cross-modal feature (CM5). We use publicly available implementations and pre-trained weights by the original authors (https://github.com/Stanford-TML/EDGE), which is trained using data from the AIST Dance DB. Currently, the only published weight for EDGE, a publicly available state-of-the-art model, is this. Although it is possible that training with different data might change individual results, we expect the relationships between modalities and overall trends across cortical voxels to remain unchanged.

To extract the features corresponding to a particular slice, we extract the motion, audio, and cross-modal features corresponding to that slice, respectively. To account for the hemodynamic response delay, stimulus features are time-shifted by 3 seconds and then averaged with the stimulus feature corresponding to each volume and the feature corresponding to the subsequent two-second volumes.

Encoding model estimation

We use the training dataset to determine the weights of L2-regularized linear regression models. Subsequently, we use these weights to make predictions for the voxels in the test dataset. We use predicted voxel activities to compute Pearson’s correlation coefficients between predicted and actual voxel activities. The regularization parameter for each voxel is determined by 10-fold cross-validation, utilizing a set of 25 logarithmically spaced regularization parameters ranging from 10−12 to 1012. Then, we check if the predicted correlations are statistically significant by comparing them to the null distribution of correlations between two independent Gaussian random vectors of equal length7. We determine P < 0.05 as significance level and adjust for multiple comparisons using the FDR approach.

Stacked regression

We use stacked regression47 to construct a unified encoding model that simultaneously uses motion, audio, and cross-modal features. For each participant, feature space, and voxel, 20% of the training data is reserved for validation, encoding models are trained on the remaining 80%. This procedure is repeated five times. We combine the predictions of these encoding models on the five folds, resulting in full held-out predictions of the training data. Following cross-validation, we construct a covariance matrix of residuals for each voxel v and participant s:

where n represents the total number of time points, y represents the ground truth BOLD response for voxel v in participant s. The terms \(f\left({x}_{p}^{i}\right)\) and \(f\left({x}_{q}^{i}\right)\) are the predicted responses at time i from the encoding models for feature spaces p and q, respectively. The indices p and q denote different feature spaces (e.g., motion, audio, or cross-modal). We then optimize the quadratic problem \({\min }_{{\alpha }_{1},{\alpha }_{2},\ldots,{\alpha }_{k}}{\sum }_{p=1}^{k}\mathop{\sum }_{q=1}^{k}{\alpha }_{p}{\alpha }_{q}{R}_{p,q}\) such that \({\alpha }_{j}\ge 0\) for all j > 0, and \(\mathop{\sum }_{j}^{k}{\alpha }_{j}=1\) where k is the number of feature spaces. A quadratic program solver is used to obtain a convex set of attributions αj which serve as weights for each feature space in the joint encoding model. This yields the final encoding model:

Next, we independently validate this stacked encoding model using a held-out validation set. Each \({\alpha }_{j}\) reflects the importance, or contribution, of the corresponding feature space within the stacking model for a given voxel. In the main analysis (Fig. 3d–f), we calculate the averaged αj values for each ROI and participant. For further details of the methodology, please refer to ref. 47.

Collection of concept ratings for dance clips from a crowd-sourcing experiment

We use 34 basic emotion categories from previous studies49 as concept ratings for each dance clip. In addition, we conduct our own interviews with several experienced dancers, from which we add six concepts. Ratings for all dance clips are collected through an online experiment via Crowdworks, Japan. All concepts and instructions are written in Japanese, a language all participants understand. Each participant in the online experiment (N = 250) viewed 60 randomly selected dance clips. They watched one dance clip at a time and reported whether each concept came to their mind, which is intended to capture both what they thought the dancer was trying to express (“expressed emotion”) and their own feelings (“perceived emotion”). We recognize that this phrasing could encompass both aspects. For example, some clips may have conveyed a specific emotion (e.g., “joy” or “boring”) or a subdued style without necessarily implying that participants themselves felt such emotion watching them. Multiple raters (1–12, median = 7 participants; see Supplementary Fig. 17) rated each dance clip; we calculated the average score of the ratings for each dance clip from multiple raters per individual concept. Separate questions are asked about their enjoyment (“like”) and the technical proficiency (“technique”), from 1 to 9. To ensure validity, for every five dance clips viewed, raters were asked to indicate what the dancers were wearing (attention-check trial). We use only participants who answered correctly to every question, resulting in a total of 250 to 166 participants.

Collection of concept ratings for dance clips from fMRI participants

To further examine whether the fMRI participants could be considered comparable to the crowd-sourced population in terms of concept ratings, we conduct an additional experiment with a subset of fMRI participants (N = 5). These participants provide emotion ratings for a subset (480 clips for 4 participants, 240 clips for 1 participant) of the dance clips they viewed during the fMRI scans (1163 clips in total). For each clip, we compute the cosine similarity between each participant’s binary rating (0 or 1) and the corresponding crowd-sourced rating probabilities (ranging from 0 to 1), and then average these similarities across all clips. Supplementary Fig. 18a shows that these ratings align more closely with the broader crowd-sourced ratings than would be expected by chance. Moreover, Supplementary Fig. 18b shows that the “boring” effect is not attributable to extraneous factors such as participants being more likely to report boredom later in the viewing session. Although it remains possible that the high “boring” effect arose because participants felt bored after continuously watching multiple dance clips, these results do not indicate any relationship between the number of dance clips viewed and the “boring” rating.

Correlation between concepts ratings and fMRI responses

We extract cross-modal features (CM5 in EDGE) for all non-overlap motion sequences derived from all dance clips within the AIST Dance DB to investigate the relationship between concept ratings and the degree of brain activity induced by the dance clips (N = 18,109 sequences from 1408 dance clips). Note that these clips include dance clips that are not used in the fMRI experiment. To estimate brain activity across the brain for each dance clip, for each participant, we multiply the extracted features by the encoding weights. Finally, we calculate correlations between the estimated brain activity and the 42 concepts across dance clips for each voxel, then average the values across voxels within each ROI to obtain a single correlation coefficient for each ROI. We conduct significance testing by collecting correlation coefficients between the randomly shuffled brain activation and concept, repeated 10,000 times. After performing family-wise error correction, we identify concepts having significantly positive or negative correlations. We repeat this process for each participant and ROI.

The difference between expert dancers and novices

We examine differences in the representation of dance features in the brains of expert dancers and novices from the following three perspectives:

-

1.

Extent of prediction across the brain (Fig. 5a). To this end, we calculate the number of voxels with significant prediction performance for each participant and feature, and compare these values between groups.

-

2.

Similarity of evoked patterns across participants (Fig. 5b, c). To this end, for each participant, we calculate the brain activity elicited by the cross-modal features (CM5) of each dance clip. Next, we calculate the correlations of brain activity patterns evoked from the dance clips for each group, all participant pairs, and each ROI. To assess whether similarity differed between groups, we repeatedly shuffle the “Expert” and “Novice” labels 1000 times, recalculate the group differences in mean correlation coefficients, and use this null distribution to evaluate statistical significance (Fig. 5c).

-

3.

Finally, for each concept, the percentages of ROIs showing significant correlations are calculated separately in the two groups, and compared the resulting distributions (Supplementary Table 1).

The difference between the estimated brain activation for artificial and real stimuli

For each motion sequence obtained from dance clips in the AIST Dance DB, we prepare 10 artificial dance clips by randomly selecting 10 music that do not correspond to the genre of the actual dance clip. We then generate cross-modal features (CM5 in EDGE) from the artificial dance clips, which we use as input for each participant’s encoding model to estimate the induced brain activity. We subsequently analyze whether artificial dance clips induce significantly greater or reduced brain activation than real clips across the whole brain. To assess significance, we randomly select the same number of artificial cross-modal features as the original cross-modal features for each ROI and participant, ensuring no duplicates, and calculate their mean estimated brain activity. This procedure is repeated 1000 times, and the resulting values are used for the null distribution.

Effect of training dataset of EDGE

One potential concern is the overlap between the training data used in pretraining EDGE and the stimuli used in the fMRI experiment, raising questions of circularity. To address this, we retrain EDGE using only the training dataset employed in the fMRI training sessions. This new dataset consists of 916 dance clips, a 6.5% reduction compared to the original (training dataset for the official EDGE) dataset of 980 clips. This reduction leads to slightly lower training precision as expected, reflected in higher losses during retraining compared to the original EDGE. However, the overall brain encoding trends remain highly consistent, indicating that the choice of training dataset for EDGE does not compromise the robustness of our results (Supplementary Fig. 19).

In silico simulation of motion–music pairings

To investigate whether our in silico simulator could induce different predicted neural response patterns, we created a set of “artificial dance clips” based on the AIST Dance DB. For each motion sequence in the database, we generate 10 mismatched clips by randomly pairing that motion with music from 10 different genres, excluding the motion’s original music. We then extract cross-modal features (CM5) from these resulting 10 artificial motion–music combinations via the same procedure used for real clips (see above for full feature extraction details). Using voxel-wise encoding models trained on the real dance clips, we next feed the cross-modal features of each artificial clip into the models to estimate its predicted neural response. We then compare these responses to those predicted by the original (i.e., natural) motion–music pairing. Across participants, we summarize the extent to which artificial versus original clips elicit stronger or weaker activity in each voxel, further aggregating these results at the ROI level.

Notably, real motion–music pairs tend to yield stronger activity in sensory-dominant regions, including visual and auditory cortices, while artificial pairings produce comparatively higher activation in more frontal areas. One possible explanation is that incongruent pairings may engage regions involved in cognitive control, prediction error, or evaluative processes. However, because no behavioral data were collected to assess perceived mismatch, our interpretation of potential prediction error or incongruence effects remains speculative. Additionally, although our approach can be extended to both novice and expert participants, we did not observe clear expertise-related differences with the artificial clips in this preliminary analysis. Future work may refine the number and type of artificially paired stimuli or include behavioral tasks to more definitively evaluate how expertise modulates sensitivity to incongruent dance stimuli. It is also important to note that these in silico manipulations serve as a proof-of-concept rather than an exhaustive search for the best or worst pairings. Because our dataset contains fewer distinct music tracks than movement clips, we fix the movement and vary the music to avoid a combinatorial explosion. While our goal is to demonstrate the feasibility of systematically manipulating cross-modal dance stimuli, future research should explore a broader stimulus space and confirm whether such manipulations indeed stimulate or suppress specific brain regions.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data generated in this study and reported in the paper’s figures and supplementary information are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file and at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/UTNMG. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code to perform analysis is provided at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/UTNMG.

References

Yamins, D. L. K. et al. Performance-optimized hierarchical models predict neural responses in higher visual cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 8619–8624 (2014).

Kell, A. J. E., Yamins, D. L. K., Shook, E. N., Norman-Haignere, S. V. & McDermott, J. H. A task-optimized neural network replicates human auditory behavior, predicts brain responses, and reveals a cortical processing hierarchy. Neuron 98, 630–644 (2018).

Goldstein, A. et al. Shared computational principles for language processing in humans and deep language models. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 369–380 (2022).

Schrimpf, M. et al. The neural architecture of language: Integrative modeling converges on predictive processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2105646118 (2021).

Takagi, Y. & Nishimoto, S. High-resolution image reconstruction with latent diffusion models from human brain activity. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 14453–14463 (2023).

Nishimoto, S. et al. Reconstructing visual experiences from brain activity evoked by natural movies. Curr. Biol. 21, 1641–1646 (2011).

Huth, A. G., De Heer, W. A., Griffiths, T. L., Theunissen, F. E. & Gallant, J. L. Natural speech reveals the semantic maps that tile human cerebral cortex. Nature 532, 453–458 (2016).

Lescroart, M. D. & Gallant, J. L. Human scene-selective areas represent 3D configurations of surfaces. Neuron 101, 178–192 (2019).

Khosla, M., Ngo, G. H., Jamison, K., Kuceyeski, A. & Sabuncu, M. R. Cortical response to naturalistic stimuli is largely predictable with deep neural networks. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe7547 (2021).

Kringelbach, M. L., Perl, Y. S., Tagliazucchi, E. & Deco, G. Toward naturalistic neuroscience: Mechanisms underlying the flattening of brain hierarchy in movie-watching compared to rest and task. Sci. Adv. 9, eade6049 (2023).

Denk, T. I. et al. Brain2Music: Reconstructing music from human brain activity. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.11078 (2023).

Stein, B. E. & Stanford, T. R. Multisensory integration: current issues from the perspective of the single neuron. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 255–266 (2008).

Karpati, F. J., Giacosa, C., Foster, N. E. V., Penhune, V. B. & Hyde, K. L. Dance and the brain: a review. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 1337, 140–146 (2015).

Hanna, J. L. To Dance Is Human: A Theory of Nonverbal Communication. (University of Chicago Press, 1987).

Brown, D. E. Human universals, human nature & human culture. Daedalus 133, 47–54 (2004).

Basso, J. C., Satyal, M. K. & Rugh, R. Dance on the brain: enhancing intra-and inter-brain synchrony. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 14, 584312 (2021).

Bläsing, B. et al. Neurocognitive control in dance perception and performance. Acta Psychol. 139, 300–308 (2012).

Tsuchida, S., Fukayama, S., Hamasaki, M. & Goto, M. AIST Dance Video Database: Multi-genre, multi-dancer, and multi-camera database for dance information processing. In ISMIR vol. 1 6 (2019).

Ermutlu, N., Yücesir, I., Eskikurt, G., Temel, T. & Işoğlu-Alkaç, Ü Brain electrical activities of dancers and fast ball sports athletes are different. Cogn. Neurodyn. 9, 257–263 (2015).

Li, G. et al. Identifying enhanced cortico-basal ganglia loops associated with prolonged dance training. Sci. Rep. 5, 10271 (2015).

Fink, A., Graif, B. & Neubauer, A. C. Brain correlates underlying creative thinking: EEG alpha activity in professional vs. novice dancers. Neuroimage 46, 854–862 (2009).

Poikonen, H., Toiviainen, P. & Tervaniemi, M. Early auditory processing in musicians and dancers during a contemporary dance piece. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–11 (2016).

Bar, R. J. & DeSouza, J. F. X. Tracking plasticity: effects of long-term rehearsal in expert dancers encoding music to movement. PLoS One 11, e0147731 (2016).

Orgs, G., Dombrowski, J.-H., Heil, M. & Jansen-Osmann, P. Expertise in dance modulates alpha/beta event-related desynchronization during action observation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 27, 3380–3384 (2008).

Orgs, G. et al. Constructing visual perception of body movement with the motor cortex. Cereb. Cortex 26, 440–449 (2016).

Calvo-Merino, B., Urgesi, C., Orgs, G., Aglioti, S. M. & Haggard, P. Extrastriate body area underlies aesthetic evaluation of body stimuli. Exp. Brain Res. 204, 447–456 (2010).

Calvo-Merino, B., Glaser, D. E., Grèzes, J., Passingham, R. E. & Haggard, P. Action observation and acquired motor skills: an FMRI study with expert dancers. Cereb. Cortex 15, 1243–1249 (2005).

Orlandi, A., Zani, A. & Proverbio, A. M. Dance expertise modulates visual sensitivity to complex biological movements. Neuropsychologia 104, 168–181 (2017).

Orlandi, A. & Proverbio, A. M. Bilateral engagement of the occipito-temporal cortex in response to dance kinematics in experts. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–14 (2019).

Pilgramm, S. et al. Differential activation of the lateral premotor cortex during action observation. BMC Neurosci. 11, 1–7 (2010).

Gardner, T., Goulden, N. & Cross, E. S. Dynamic modulation of the action observation network by movement familiarity. J. Neurosci. 35, 1561–1572 (2015).

Naselaris, T., Prenger, R. J., Kay, K. N., Oliver, M. & Gallant, J. L. Bayesian reconstruction of natural images from human brain activity. Neuron 63, 902–915 (2009).

Poikonen, H., Toiviainen, P. & Tervaniemi, M. Naturalistic music and dance: cortical phase synchrony in musicians and dancers. PLoS One 13, e0196065 (2018).

Poikonen, H., Toiviainen, P. & Tervaniemi, M. Dance on cortex: enhanced theta synchrony in experts when watching a dance piece. Eur. J. Neurosci. 47, 433–445 (2018).

Jola, C., Abedian-Amiri, A., Kuppuswamy, A., Pollick, F. E. & Grosbras, M.-H. Motor simulation without motor expertise: enhanced corticospinal excitability in visually experienced dance spectators. PLoS One 7, e33343 (2012).

Di Nota, P. M., Chartrand, J. M., Levkov, G. R., Montefusco-Siegmund, R. & DeSouza, J. F. X. Experience-dependent modulation of alpha and beta during action observation and motor imagery. BMC Neurosci. 18, 1–14 (2017).

Kirsch, L. P. & Cross, E. S. Additive routes to action learning: layering experience shapes engagement of the action observation network. Cereb. Cortex 25, 4799–4811 (2015).

Pollick, F. E. et al. Exploring collective experience in watching dance through intersubject correlation and functional connectivity of fMRI brain activity. Prog. Brain Res 237, 373–397 (2018).

Jola, C. et al. Uni-and multisensory brain areas are synchronised across spectators when watching unedited dance recordings. Iperception 4, 265–284 (2013).

Olshansky, M. P., Bar, R. J., Fogarty, M. & DeSouza, J. F. X. Supplementary motor area and primary auditory cortex activation in an expert break-dancer during the kinesthetic motor imagery of dance to music. Neurocase 21, 607–617 (2015).

Burzynska, A. Z., Finc, K., Taylor, B. K., Knecht, A. M. & Kramer, A. F. The dancing brain: Structural and functional signatures of expert dance training. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11, 566 (2017).

Li, R., Yang, S., Ross, D. A. & Kanazawa, A. Ai choreographer: Music conditioned 3d dance generation with aist++. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 13401–13412 (2021).

Tseng, J., Castellon, R. & Liu, K. Edge: Editable dance generation from music. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 448–458 (2023).

Friston, K. & Kiebel, S. Predictive coding under the free-energy principle. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 364, 1211–1221 (2009).

Huth, A. G., Nishimoto, S., Vu, A. T. & Gallant, J. L. A continuous semantic space describes the representation of thousands of object and action categories across the human brain. Neuron 76, 1210–1224 (2012).

Dhariwal, P. et al. Jukebox: A generative model for music. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.00341 (2020).

Lin, R., Naselaris, T., Kay, K. & Wehbe, L. Stacked regressions and structured variance partitioning for interpretable brain maps. Neuroimage 298, 120772 (2024).

Destrieux, C., Fischl, B., Dale, A. & Halgren, E. Automatic parcellation of human cortical gyri and sulci using standard anatomical nomenclature. Neuroimage 53, 1–15 (2010).

Cowen, A. S. & Keltner, D. Self-report captures 27 distinct categories of emotion bridged by continuous gradients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, E7900–E7909 (2017).

Zador, A. et al. Catalyzing next-generation artificial intelligence through neuroai. Nat. Commun. 14, 1597 (2023).

Hein, G. et al. Object familiarity and semantic congruency modulate responses in cortical audiovisual integration areas. J. Neurosci. 27, 7881–7887 (2007).

Stevens, C., Malloch, S., McKechnie, S. & Steven, N. Choreographic cognition: The time-course and phenomenology of creating a dance. Pragmat. Cogn. 11, 297–326 (2003).

McGregor, W. Living archive: Creating choreography with artificial intelligence. Arts & Culture Google, (2019).

Kirsh, D. Thinking with external representations. AI Soc. 25, 441–454 (2010).

Cross, E. S. The neuroscience of dance takes center stage. Neuron 113, 808–813 (2025).

Hardwick, R. M., Caspers, S., Eickhoff, S. B. & Swinnen, S. P. Neural correlates of action: Comparing meta-analyses of imagery, observation, and execution. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 94, 31–44 (2018).

Fischl, B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage 62, 774–781 (2012).

Gao, J. S., Huth, A. G., Lescroart, M. D. & Gallant, J. L. Pycortex: an interactive surface visualizer for fMRI. Front. Neuroinform. 9, 23 (2015).

Ho, J., Jain, A. & Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process Syst. 33, 6840–6851 (2020).

Ho, J. & Salimans, T. Classifier-free diffusion guidance. NeurIPS 2021 Workshop on Deep Generative Models and Downstream Applications (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Shuhei Tsuchida and Dr. Masataka Goto for providing instruction on the AIST Dance DB, Dr. Ruilong Li for providing instruction on the AIST + +, and Dr. Jessica E. Taylor for her advice on the correspondence between Japanese and English words used to describe the concepts evoked by the dance clips in our online experiments. Y.T. was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 19H05725 and PRESTO Grant Number JP-MJPR23I6. Y.T., R.O., and H.I. were supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP19H05725 and JP24H00172. D.S. was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 22K03073.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.T., D.S., R.O., and H.I conceived the study. Y.T., M.W., and R.O. designed and collected fMRI data. Y.T., D.S., and M.W. designed and collected crowd-sourced data collection. Y.T. analyzed the data. Y.T. wrote the original draft. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Frank Pollick, Huiguang He, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Takagi, Y., Shimizu, D., Wakabayashi, M. et al. Cross-modal deep generative models reveal the cortical representation of dancing. Nat Commun 16, 9937 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65039-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65039-w