Abstract

Direct harvesting of electronic-grade acetylene (C2H2) from ternary C2 mixtures is a great challenge due to the ubiquitous adsorption preference of conventional porous materials (C2H2 > ethylene (C2H4) > ethane (C2H6)). Here, we report a strategy to reverse this selectivity by leveraging ligand functionalization in porous crystals. Through the incorporation of trifluoromethyl/methyl groups into a pyrazole-carboxylate linker, we engineer a series of MOF-5 analogs. The optimal material, NTU-98, fully reverses the adsorption trend of C2 hydrocarbons (C2H6 > C2H4 > C2H2), enabling direct production of C2H2 with >99.99% purity from ternary feeds at room temperature in one-step. Combined density functional theory calculations and gas-loaded crystallographic analyses unveil the molecular mechanism: methyl groups precisely positioned within the cages enhance host-guest interactions with C2H4 and C2H6, while suppressing the binding affinity for C2H2. This work presents a porous crystal for direct C2H2 purification from ternary feeds and a blueprint for designing microporous environments targeting challenging separations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acetylene (C2H2) is a crucial feedstock in the chemical and semiconductor industries, where ultrahigh-purity electronic-grade C2H2 is indispensable for manufacturing carbon masks used in photolithography during advanced integrated circuit production1. However, industrial C2H2 streams mainly derived from cracked gas or ethane (C2H6) dehydrogenation typically contain ternary C2 hydrocarbon mixtures (C2H2, C2H4 and C2H6) with nearly identical physicochemical properties, making their separation particularly challenging2,3. Current purification strategies predominantly rely on solvent extraction, wherein C2H2 is selectively dissolved into organic solvents and subsequently recovered via desorption4. While effective, this process is constrained by the steep temperature dependence of hydrocarbon solubility, necessitating energy-intensive sub-ambient conditions (e.g., −40 °C) to maximize efficiency. Furthermore, solvent regeneration generates substantial liquid waste, and the purity of recovered C2H2 often falls short of the stringent electronic-grade thresholds in a single operational cycle. These limitations underscore an urgent demand for innovative separation technologies that simultaneously prioritize energy.

Adsorptive separation presents a compelling alternative to conventional absorption methods, particularly for applications requiring high selectivity, energy efficiency, facile regeneration, and operational versatility. Unlike solvent-dependent absorption, adsorption leverages the selective interactions between target molecules and tailored porous adsorbents, thereby enabling precise capture of trace impurities and adaptability to environmentally sensitive processes5,6. Microporous materials such as zeolites and activated carbon have been considered as prominent candidates for C2H2 purification7,8. Yet their practical utility is hampered by inherent limitations: elevated temperature for adsorbent regeneration and/or insufficient selectivity. Particularly, the high reactivity of C2H2 at elevated temperatures may produce undesirable side reactions (e.g., polymerization or decomposition), adding new impurities or blocking the pore of the adsorbent. These challenges persist even in state-of-the-art systems, restricting scalability and industrial adoption. Highlight the need for developing adsorbents with engineered pore geometries and optimized binding affinities—innovations critical to achieving highly pure C2H2.

Porous coordination polymers (PCPs), also known as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), have emerged as a versatile platform for light hydrocarbon separations, owing to their precisely engineered pore geometries9,10,11 and chemical functionalities12,13,14 enabled by crystal engineering and isoreticular design principles15,16,17,18,19. The high quadrupole moment and π-electron density of C2 gases hydrocarbons drive strong interactions with polar binding sites or open metal centers in PCPs20, leading to a typical adsorption sequence of C2H2 > C2H4 > C2H621. However, to facilitate efficient and direct harvesting of highly pure C2H4 in the adsorption process, strategies involving supramolecular sites and structural dynamics have been developed for tuning the adsorption sequence22,23,24,25,26,27,28, with notable success in C2H4 purification via partially reversed selectivity adsorption order (C2H2 > C2H6 > C2H4)29,30,31. However, due to its high quadrupole moment and small kinetic diameter, C2H2 remains the most strongly adsorbed species in most porous systems. By utilizing a perfluorinated narrow channel, a reversed adsorption order of C2 hydrocarbons has been observed in Zn-FBA; however, the negligible uptake differences between C2H6-C2H2 and C2H4-C2H2 render C2H2 purification infeasible from C2 ternary mixtures32. In other words, neither a function-driven approach nor a finely tuned structural design of PCPs has successfully achieved electronic-grade C2H2 purification from ternary C2 mixtures in one-step under industrially relevant conditions.

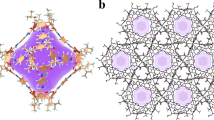

In this work, we address the challenge of purifying C2H2 from ternary C2 mixtures by adopting a counterintuitive strategy: weakening the host-guest interactions with C2H2 while enhancing the binding with its saturated counterparts, C2H6 and C2H4. To achieve this, we developed an adsorption-steering methodology utilizing a MOF-5 analog platform (Zn4O(PyC)3, PyC = 4-pyrazolecarboxylate) (Fig. 1a)33,34. Through incorporation of inert functional groups (trifluoromethyl and methyl groups) to the PyC ligand, we synthesized a series of MOF-5 analogs and realized several synergistic objectives: (1) maintaining a high surface area (>1000 m2 g−1) to ensure adequate adsorption capacity; (2) strengthening van der Waals interactions with hydrogen-rich C2H6 and C2H4 while simultaneously suppressing the affinity for C2H2; and (3) enhancing the water-stability of the framework through steric protection of the metal nodes by hydrophobic methyl groups. Of them, NTU-98, featuring two methyl groups on the PyC ligand, represents a robust framework and exhibits a fully inversed adsorption order (C2H6 > C2H4 > C2H2), enabling the direct harvesting of high-purity C2H2 (>99.99%) from C2 ternary mixtures at 298 K. Density functional theory calculations and gas-loaded crystallographic analyses reveal that in NTU-98, the abundant methyl groups within the small cage, along with the methyl-decorated nitrogen/oxygen adsorption corners in the large cage, provide stronger interactions with the more saturated C2H6 and C2H4, while concurrently diminishing the affinity for C2H2. This behavior contrasts with other analogs with single methyl or trifluoromethyl group on the ligand, which exhibit significantly limited separation efficiency.

a Systematic implantation of inert groups with varying types and loading amounts for enhanced C2H6/4 uptakes and C2H6/4/C2H2 selectivities. b–d Corresponding structures: NTU-96, NTU-97 and NTU-98, respectively. Color code: Zn4O, brown tetrahedra; C, gray; O, red; N, blue; H, white; F, cyan; void space, highlighted in green, blue and light red; gray row, fine-tuned structures.

Results

Structure and adsorption properties

Colorless transparent crystals of NTU-96, NTU-97 and NTU-98 were obtained through solvothermal reactions of zinc nitrate hexahydrate and 4-PyC derivatives (TFPC, MePC and DiMePC, respectively) (Fig. 1b–d). Single crystal X-ray diffraction results demonstrated that NTU-96 and NTU-97 both crystallize in space group Fm-3m, while NTU-98 crystallizes in F-43m (Supplementary Table 1). The similar coordination properties of pyrazolate and carboxylate make these structures analogous to that of MOF-5, featuring a classical node of Zn4O (Supplementary Figs. 1–5). But, differently, the coordination of the two N sites of 4-PyC derivatives greatly constraints the rotational freedom of the ligand, yielding the three-dimensional framework with two different cages in NTU-96 to NTU-98. Upon ligand functionalization with trifluoromethyl, methyl, and two methyl groups, the internal diameter of the smaller cubic cage slightly contracts, shrinking from the original 8.0 Å (in Zn4O(PyC)3) to 5.8, 6.0, and 5.6 Å, respectively (Fig. 1b–d, Supplementary Fig. 6). Note that, although Zn4(μ4-O)(DiMePC)3 was previously investigated for the capture of nerve agents and mustard gas35, the reported structure is not exactly the same as that of NTU-98 (with different crystal symmetries), and the functional implications of the two methyl groups in modulating host–guest interactions remain unexplored. Phase purity of NTU-96, NTU-97 and NTU-98 were confirmed by the powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis (Supplementary Figs. 7–9). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of as-synthesized and activated samples confirm that these materials are thermally stable up to 400 °C (Supplementary Figs. 10–15).

N2 (77 K) and CO2 (195 K) adsorption isotherms were collected to evaluate the permanent microporosity of NTU-96 to NTU-98, respectively. Type-I adsorption isotherms were observed without any hysteresis (Supplementary Figs. 16, 17). NTU-96 and NTU-97 exhibit high N2 uptake, up to 250.6 and 320.3 cm3 g−1, respectively. However, the N2 uptake of NTU-98 (44.5 cm3 g−1) is much lower than that of the other two, but it has comparable CO2 uptake (240.3 cm3 g−1). This is likely due to the blocking effect of aggregated N2 at very low temperature. Based on the CO2 isotherms, Brunauer-Emmet-Teller (BET) surface areas of the three were calculated to be ∼1150, 1470 and 1245 m2 g−1, respectively. The derived pore size distribution centers at 8.8 Å in NTU-96, 9.6 Å in NTU-97 and 8.4 Å in NTU-98, which are all comparable to the geometrically determined values of the cavities based on the crystal structures.

To evaluate the role of nanopores in PCPs, single-component adsorption isotherms of C2H2, C2H4, and C2H6 were collected at 273–308 K, along with data for the precursor Zn4O(PyC)3 (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figs. 18–53, and Supplementary Table 2). Zn4O(PyC)3 exhibits a preference for C2H6 adsorption, with nearly overlapping adsorption isotherms for C2H2 and C2H4. This observation correlates with the zero coverage isosteric heat of adsorption (Qst) values (C2H6: 25 kJ mol−1; C2H4: 22.6 kJ mol−1 and C2H2: 23.8 kJ mol⁻¹). In contrast, NTU-96 demonstrates a completely reversed adsorption order for these gases. The Qst values for NTU-96 are significantly higher, measuring 29.4 kJ mol−1 for C2H6, 27.7 kJ mol−1 for C2H4, and 26.5 kJ mol−1 for C2H2, all exceeding those of Zn4O(PyC)3 (Table 1 and Supplementary Figs. 54–66). The elevated Qst for C2H2 suggests that the polar trifluoromethyl groups have a synergistic effect with some of the original adsorption sites rather than interfering with or shielding the adsorption sites. However, the uptake difference between C2H4 and C2H2 remains relatively modest, at 6.7 cm3 g−1 at 298 K and 50 kPa. Upon substituting the trifluoromethyl with methyl group, NTU-97 also exhibits a completely reversed adsorption order for C2 hydrocarbons. This alteration is accompanied by a moderate increase in the uptake difference between C2H4 and C2H2, recorded at 10.3 cm3 g−1, despite a significantly larger uptake difference of 31.3 cm3 g−1 between C2H6 and C2H2. Importantly, NTU-98, which contains two implanted methyl groups, demonstrates not only a fully inversed adsorption order, but also steeper uptake profiles for all three gases (Fig. 2a–c). When compared to benchmark materials, NTU-98 exhibits the largest uptake difference for C2H4 and C2H2 (11.3 cm3 g−1), while its uptake difference for C2H6 and C2H2 (26.5 cm3 g−1) is only slightly smaller than that of NTU-97 (31.3 cm3 g−1) (Fig. 2d, e and Supplementary Table 3). Additionally, the Qst values for NTU-98 are 32.2 kJ mol−1 for C2H6 and 27.3 kJ mol−1 for C2H4, both of which are marginally higher than those for NTU-97 (28 and 25 kJ mol−1, respectively). However, these values are still lower than that of Zn-FBA (42.8 and 39.8 kJ mol−1), indicating a reduced energy requirement during cyclic operations. Considering the emerging adsorption order and systematically tuned uptake differences, ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST)36,37,38 was applied to calculate the adsorption selectivity (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Figs. 67–71). NTU-98 demonstrated exceptional adsorption selectivity for equimolar C2H4/C2H2 and C2H6/C2H2 mixtures, achieving values of 1.62 and 2.62, respectively, at 298 K and low pressure. These selectivities further increased at 273 K, reaching 1.95 (C2H4/C2H2) and 3.98 (C2H6/C2H2), underscoring its temperature-dependent performance. In contrast, NTU-96 (1.25 and 1.88), NTU-97 (1.51 and 2.32), and Zn4O(PyC)3 (0.93 and 1.09) exhibited markedly lower selectivities under identical conditions. The results highlight NTU-98 as a superior adsorbent for the challenging separation of C2H2 from C2H6 and C2H4-containing mixtures.

C2H2, C2H4 and C2H6 adsorption isotherms of a NTU-96, b NTU-97 and c NTU-98 at 298 K, respectively. Comparison of d C2H4/C2H2 and e C2H6/C2H2 uptake difference of the benchmark PCPs at 298 K, 50 kPa. Values for literature materials are taken from refs: Al-PyDC43, Uio-67-(NH2)231, TJT-10029, [Zn(BDC)(H2BPZ)].4H2O44, NTU-73-CH345, HIAM-21046, Cu-FINA-247, BSF-148, MOF-52549, NPU-230, Azole-Th-125 and NUM-750. f IAST selectivity of C2H6/C2H2 (1/1, v/v) and C2H4/C2H2 (1/1, v/v) at 298 K.

Adsorption mechanism studies

To elucidate the molecular interactions between NTU-98 and C2 hydrocarbons, we conducted dispersion-corrected density functional theory (DFT-D) calculations. Our analysis reveals that the primary adsorption sites for all three C2 hydrocarbons are localized at the center of the small cage and the corners of the large cage within the NTU-98 framework. In Fig. 3, we show schematically the DFT-D-optimized adsorption structures of the three gas molecules at various adsorption sites. Within the small cage, the two HC2H2 interact with two CCH3 from DiMePc, forming C–H···C interactions with distances ranging from 3.253 to 3.353 Å (Fig. 3a). Additionally, a hydrogen bond is established between a HCH3 and a CC2H2 at a distance of 3.189 Å. Interestingly, four hydrogen bonds are observed between HC2H4 and CCH3 from DiMePc, with bond distances varying from 3.119 to 3.378 Å, coupled with a hydrogen bond between HCH3 and CC2H4 at 3.469 Å. In addition, due to the increased Hδ⁺ on C2H6, six hydrogen bonds are formed with the CCH3 groups, with bond lengths ranging from 3.269 to 3.483 Å. The increased number of hydrogen bonds, although each has slightly different bond length, clearly indicates progressively stronger host–guest interactions for C2H4 and especially C2H6. Owing to the asymmetric nature of the ligand, the metal nodes within the framework can exhibit mixed coordination environments, featuring both Zn–N and Zn–O bonds. To accurately model the host-guest interactions, we defined two representative configurations for the large cage corners, differentiated by the identity of the coordinating atom (either nitrogen or oxygen). In both cases, C2H6 and C2H4 form more hydrogen bonds and C–H···π interactions with DiMePc than C2H2 (Fig. 3b, c). For comparison, we also performed calculations on the C2 hydrocarbon adsorption in the parent framework Zn4O(PyC)3. In the absence of functional methyl groups, adsorption primarily occurs at (i) the window aperture bridging small and large cages, and (ii) the N/O-defined adsorption corners. Meanwhile, the number of hydrogen bonds at N/O corners increases with the number of hydrogen atoms on the guest molecule (C2H6 > C2H4 > C2H2). However, at the window aperture, all three C2 species form nearly the same number of hydrogen bonds (C2H2: 8, C2H4: 7 and C2H6: 8), suggesting non-discriminative binding (Supplementary Fig. 72). This contrast—between site-specific selectivity and aperture-driven uniformity—explains the diminished C2 selectivity of the parent framework. These observations are further evident from the calculated static gas binding energies at various adsorption sites (Table 2), which are also fully consistent with the experimental Qst values.

a C2 hydrocarbons located at the small cage center, b at the cage corner N site, and c at the cage corner O site. Color code: Zn, light green; C, gray; O, red; N, blue; H, white; C2H2: orange; C2H4: dark green; C2H6, purple; The green and yellow dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonding and C-H…π interaction, respectively.

To validate the computational modeling results, we further experimentally determined the gas-loaded crystal structures by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Due to the high crystal symmetry, accurately resolving the orientations of the ligand and guest gas molecules is challenging, resulting in apparent orientational disorder in the experimental structures. Nevertheless, the experimental results confirm that the three primary adsorption sites—the center of small cage and the corners of large cage featuring N or O atoms—closely match the predictions from the modeling. Consistent with the calculations, gas molecules with higher Hδ+ content exhibit stronger interactions (Supplementary Fig. 73), and the experimentally observed hydrogen bond lengths are in close agreement with the calculated values. The adsorption kinetics are of the same order of magnitude, indicating a limited influence on the overall selectivity (Supplementary Fig. 73). Therefore, the high selectivity of NTU-98 for C2H4 and C2H6 over C2H2 arises from the synergistic effect of strategically positioned methyl groups within both cages and the N/O-decorated adsorption sites. These features collectively enhance the cooperative interactions with the more saturated C2H4/C2H6, while simultaneously diminishing the affinity toward the more polarizable C2H2. This molecular-level design leverages intrinsic differences in C–H bond acidity across the C2 hydrocarbon series.

Dynamic breakthrough experiments

Considering the distinct adsorption order, breakthrough experiments were carried out on the three PCPs. After initial activation, the three samples were loaded into a column, followed by further activation. The system was flushed with He until no other signal was detected. Then the corresponding feed gas was introduced into the packed column. The clear time intervals indicate that NTU-98 can effectively separate the binary mixtures of C2H6/C2H2 (v/v, 1/1) and C2H4/C2H2 (v/v, 1/1) (Fig. 4a, b and Supplementary Figs. 75, 76). After changing the feed gas to the C2 ternary mixtures, C2H2 eluted first out of the fixed bed of NTU-98 at 56.5 min·g−1, and the C2H4 breakthrough the column at 57.6 min·g−1, followed by C2H6 at 67.1 min·g−1, well matching the inversed adsorption behavior of NTU-98. With reference to the higher ratio of C2H2 during the deep purification step, the feed gas ratio was then change to 90/9/1 (C2H2/C2H4/C2H6: v/v/v)39,40. Consistently, same elution sequences were observed, of which C2H2 with high purity (>99.99%) was detected at about 37.2 min·g−1, followed by C2H4 at 41.6 min·g−1, and C2H6 at 48.8 min·g−1, the corresponding C2H2 yield is 8.64 mL g−¹ (Fig. 4c). Despite extensive research in PCP chemistry, the direct one-step purification of C2H2 with high purity from ternary C2 mixtures remains, to the best of our knowledge, unreported. In comparison, NTU-96 can also separate these ternary mixtures, but the separation time for harvesting of electronic grade C2H2 is short (Supplementary Figs. 77, 78).

Breakthrough curves of NTU-98 for a C2H6/C2H2 (1/1, v/v, 0.9 mL·min−1), b C2H4/C2H2 (1/1, v/v, 0.9 mL·min−1), c C2H2/C2H4/C2H6 (90/9/1,v/v/v, 2 mL·min−1). d Photos of the large-scale synthesis for NTU-98 (L3 = DiMePC ligand; DMF = Dimethylformamide). e Comparisons of breakthrough curves of small-scale and large-scale synthesized NTU-98 for C2H2/C2H4/C2H6 (90/9/1, v/v/v, 2 mL·min−1) mixtures. The temperature and pressure for all breakthrough experiments is 298 K and 1 bar.

For practical gas separation applications, scale-up synthesis and water stability of the adsorbent material are also two important factors to consider41. We found that rapid, scaled up synthesis of NTU-98 can be readily achieved. By adding certain amount of NH3·H2O into the stirring solution (400 mL scale) of the corresponding reactants, ∼25 g of NTU-98 can be obtained in 10 min, making the space-time yield as high as about 9000 kg/m3/day (Fig. 4d). Phase purity and porosity of the large-scale synthesized NTU-98 were validated by PXRD and gas adsorption isotherms (Supplementary Fig. 79). Importantly, large-scale synthesized NTU-98 demonstrates nearly the same separation performance for C2 hydrocarbons (Fig. 4e). Furthermore, we found that NTU-98 exhibits excellent chemical stability. Even after immersion in solutions with pH ranging from 2 to 12 for one week, the sample largely retained its crystallinity and gas uptake capacity (Supplementary Fig. 80). Such high-water stability is fully expected because the two methyl groups on each ligand effectively shield the Zn-O coordination bonds from hydrolysis. Thanks to its stability, NTU-98 does not suffer any notable performance loss during cycling breakthrough experiments (Supplementary Fig. 81).

Discussion

Addressing the challenge of directly harvesting high-purity C2H2 from ternary C2 mixtures, we present an adsorption-steering strategy that optimizes ensemble host–guest interactions in a family of porous crystals. NTU-98, featuring dual methyl groups positioned at adsorption corners, exhibits a fully inverted adsorption hierarchy (C2H6 > C2H4 > C2H2). Gas-loaded crystallography and DFT-D analyses reveal that the synergistic interplay between sterically placed methyl groups and N/O-functionalized nodes enhances binding toward saturated hydrocarbons while diminishing affinity for polarizable C₂H₂. Of them, NTU-98 combines high structural robustness and synthetic scalability, enabling direct production of electronic-grade C2H2 (>99.99%) from ternary C2 feeds in one step under ambient conditions, which has not been demonstrated in earlier PCP studies. This design strategy is broadly applicable to other porous frameworks, providing a framework for exploring inverse adsorption hierarchies and advancing adsorbents for challenging separations.

Methods

Synthesis of NTU-96

5-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylic acid (TFPC) (4 mg, 0.022 mmol) and Zn(NO3)2•6H2O (12 mg, 0.04 mmol) were added to the 1 mL mixed solvent of DMA/H2O (v/v, 1/1), sonicated and placed into a 10 mL glass bottle, and heated in an oven at 120 °C for 48 h. After the end of the reaction, colorless crystals are obtained. The NTU-96 crystals are washed with DMA and stored dry at room temperature.

Synthesis of NTU-97

3-methyl-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylic acid (MePC) (4 mg, 0.032 mmol) and Zn(NO3)2•6H2O (20 mg, 0.07 mmol) were added to the 1 mL mixed solvent of DEF/H2O (v/v, 3/1), sonicated, and transferred to a 10 mL glass bottle. Subsequently, the glass bottles were heated in an oven at 85 °C for 48 h. After the end of the reaction, colorless crystals were obtained. The NTU-97 crystals are washed with DEF and stored dry at room temperature.

Synthesis of NTU-98 (small-scale)

3,5-Dimethyl-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylic acid (DiMePC, 14 mg, 0.1 mmol) and zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, 27 mg, 0.09 mmol) were dissolved in 1 mL of N,N’-dimethylformamide (DMF) with the aid of sonication. The solution was then transferred into a 10 mL glass vial and heated at 120 °C for 24 h. Upon cooling to room temperature, colorless crystals of NTU-98 were obtained. The crystals were washed with fresh DMF and dried under ambient conditions.

Synthesis of NTU-98 (large-scale)

For scale-up, the corresponding reactants (DiMePC: 14 g, 0.1 mol and Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O: 27 g, 0.09 mol) were dissolved in 400 mL of DMF with stirring, followed by the addition of an appropriate amount of aqueous ammonia (NH3·H2O). Crystallization occurred rapidly, yielding ~25 g of NTU-98 within 10 min.

Gas adsorption measurements

Single gas adsorption isotherms were performed on a Belsorp volumetric adsorption instrument (BEL Japan Corp.). In the sorption measurements, ultra-high-purity grade gases of C2H2, C2H4, C2H6 and CO2 were used throughout the adsorption experiments.

Dynamic breakthrough experiments

Breakthrough experiments were performed on the Beifang Gaorui CT-4 system. The initial activated samples were tightly packed into a stainless-steel column (φ = 0.40 cm, L = 30 cm). Then, the column was activated under vacuum at the corresponding temperature and then swept with helium (He) flow to remove impurities. Until no signal was detected, the gas flow was dosed into the column. Breakpoints were determined by gas chromatography. Between cycling experiments, re-generation can be achieved under high vacuum at 393 K for half-hour. Pressure of the feed gas is 1 bar. For breakthrough experiments, the mixtures of C2H6/C2H2, C2H4/C2H2 and C2H6/C2H4/C2H2 were obtained by utilizing a premix gas cylinder.

Data availability

The crystal data generated in this study have been deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under accession code 2434597-2434601 and 2434605 [https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures]. Source data of the sorption tests, gas adsorption enthalpies, selectivities and break through tests that support the findings of this study are provided as a SourceData file (ref. 42). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Vininski, P. J. V. Acetylene process gas purification methods and systems. US patent US8182589B2 (2009).

PASSLER, P. Acetylene In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (Wiley, 2011).

Adil, K. et al. Gas/vapour separation using ultra-microporous metal–organic frameworks: insights into the structure/separation relationship. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 3402–3430 (2017).

Weissermel, K. & Arpe, H.-J. Acetylene. In Industrial Organic Chemistry (Wiley, 2003).

Yang, S.-Q., Hu, T.-L. & Chen, B. Microporous metal-organic framework materials for efficient capture and separation of greenhouse gases. Sci. China Chem. 66, 2181–2203 (2023).

Lan, T. et al. Opportunities and critical factors of porous metal–organic frameworks for industrial light olefins separation. Mater. Chem. Front. 4, 1954–1984 (2020).

Chai, Y. et al. Control of zeolite pore interior for chemoselective alkyne/olefin separations. Science 368, 1002–1006 (2020).

Choi, B.-U., Choi, D.-K., Lee, Y.-W., Lee, B.-K. & Kim, S.-H. Adsorption equilibria of methane, ethane, ethylene, nitrogen, and hydrogen onto activated carbon. J. Chem. Eng. Data 48, 603–607 (2003).

Skrabalak, S. E. & Vaidhyanathan, R. The chemistry of metal organic framework materials. Chem. Mater. 35, 5713–5722 (2023).

Zhai, Q.-G., Bu, X., Zhao, X., Li, D.-S. & Feng, P. Pore space partition in metal–organic frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 407–417 (2017).

Tian, Y. & Zhu, G. Porous aromatic frameworks (PAFs). Chem. Rev. 120, 8934–8986 (2020).

Das, M. C., Xiang, S., Zhang, Z. & Chen, B. Functional mixed metal–organic frameworks with metalloligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 10510–10520 (2011).

Kitagawa, S., Kitaura, R. & Noro, S. -i. Functional porous coordination polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 2334–2375 (2004).

Ji, Z., Wang, H., Canossa, S., Wuttke, S. & Yaghi, O. M. Pore chemistry of metal–organic frameworks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2000238 (2020).

Zhao, X., Wang, Y., Li, D.-S., Bu, X. & Feng, P. Metal–organic frameworks for separation. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705189 (2018).

Wan, J. et al. Molecular sieving of propyne/propylene by a scalable nanoporous crystal with confined rotational shutters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202316792 (2023).

Yang, W. et al. Regulating the dynamics of interpenetrated porous frameworks for inverse C2H6/C2H4 separation at elevated temperature. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202425638 (2025).

Zhang, M. et al. Fine tuning of MOF-505 analogues to reduce low-pressure methane uptake and enhance methane working capacity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 11426–11430 (2017).

Zheng, B., Bai, J., Duan, J., Wojtas, L. & Zaworotko, M. J. Enhanced CO2 binding affinity of a high-uptake rht-type metal−organic framework decorated with acylamide groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 748–751 (2011).

Wu, Y. & Weckhuysen, B. M. Separation and purification of hydrocarbons with porous materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 18930–18949 (2021).

Yang, S. et al. Supramolecular binding and separation of hydrocarbons within a functionalized porous metal–organic framework. Nat. Chem. 7, 121–129 (2015).

Wang, G.-D. et al. Scalable synthesis of robust MOF for challenging ethylene purification and propylene recovery with record productivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202319978 (2024).

Geng, S. et al. Scalable room-temperature synthesis of highly robust ethane-selective metal–organic frameworks for efficient ethylene purification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 8654–8660 (2021).

Su, K., Wang, W., Du, S., Ji, C. & Yuan, D. Efficient ethylene purification by a robust ethane-trapping porous organic cage. Nat. Commun. 12, 3703 (2021).

Xu, Z. et al. A robust Th-azole framework for highly efficient purification of C2H4 from a C2H4/C2H2/C2H6 mixture. Nat. Commun. 11, 3163 (2020).

Zhang, P. et al. Ultramicroporous material based parallel and extended paraffin nano-trap for benchmark olefin purification. Nat. Commun. 13, 4928 (2022).

Li, L. et al. Ethane/ethylene separation in a metal-organic framework with iron-peroxo sites. Science 362, 443–446 (2018).

Dong, Q. et al. Tuning gate-opening of a flexible metal–organic framework for ternary gas sieving separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 22756–22762 (2020).

Hao, H.-G. et al. Simultaneous trapping of C2H2 and C2H6 from a ternary mixture of C2H2/C2H4/C2H6 in a robust metal–organic framework for the purification of C2H4. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 16067–16071 (2018).

Zhu, B. et al. Pore engineering for one-step ethylene purification from a three-component hydrocarbon mixture. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 1485–1492 (2021).

Gu, X.-W. et al. Immobilization of Lewis basic sites into a stable ethane-selective MOF enabling one-step separation of ethylene from a ternary mixture. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 2614–2623 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. Adsorption in reversed Order of C2 hydrocarbons on an ultramicroporous fluorinated metal-organic framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202204046 (2022).

Li, H., Eddaoudi, M., O’Keeffe, M. & Yaghi, O. M. Design and synthesis of an exceptionally stable and highly porous metal-organic framework. Nature 402, 276–279 (1999).

Tu, B. et al. Ordered vacancies and their chemistry in metal–organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 14465–14471 (2014).

Montoro, C. et al. Capture of nerve agents and mustard gas analogues by hydrophobic robust MOF-5 type metal–organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 11888–11891 (2011).

Cessford, N. F., Seaton, N. A. & Düren, T. Evaluation of ideal adsorbed solution theory as a tool for the design of metal–organic framework materials. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 51, 4911–4921 (2012).

Bae, Y.-S. et al. Separation of CO2 from CH4 using mixed-ligand metal−organic frameworks. Langmuir 24, 8592–8598 (2008).

Krishna, R. Metrics for evaluation and screening of metal–organic frameworks for applications in mixture separations. ACS Omega 5, 16987–17004 (2020).

Yan, B., Cheng, Y. & Jin, Y. Cross-scale modeling and simulation of coal pyrolysis to acetylene in hydrogen plasma reactors. AlChE J. 59, 2119–2133 (2013).

Yan, B., Xu, P., Jin, Y. & Cheng, Y. Understanding coal/hydrocarbons pyrolysis in thermal plasma reactors by thermodynamic analysis. Chem. Eng. Sci. 84, 31–39 (2012).

Yan, B., Xu, P., Guo, C. Y., Jin, Y. & Cheng, Y. Experimental study on coal pyrolysis to acetylene in thermal plasma reactors. Chem. Eng. J. 207, 109–116 (2012).

Zhang, M., Duan, J., Feng, Y. & Bai, J. Fully inverse adsorption enables one-step high-purity C2H2 separation from ternary C2 mixtures in a robust porous crystal. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29815517 (2025).

Wu, E. et al. Incorporation of multiple supramolecular binding sites into a robust MOF for benchmark one-step ethylene purification. Nat. Commun. 14, 6146 (2023).

Wang, G.-D. et al. One-step C2H4 purification from ternary C2H6/C2H4/C2H2 mixtures by a robust metal–organic framework with customized pore environment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202205427 (2022).

Li, Y., Wu, Y., Zhao, J., Duan, J. & Jin, W. Systemic regulation of binding sites in porous coordination polymers for ethylene purification from ternary C2 hydrocarbons. Chem. Sci. 15, 9318–9324 (2024).

Liu, J., Wang, H. & Li, J. Pillar-layer Zn–triazolate–dicarboxylate frameworks with a customized pore structure for efficient ethylene purification from ethylene/ethane/acetylene ternary mixtures. Chem. Sci. 14, 5912–5917 (2023).

Wu, X.-Q. et al. Understanding how pore surface fluorination influences light hydrocarbon separation in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Eng. J. 407, 127183 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Yang, L., Wang, L., Duttwyler, S. & Xing, H. A microporous metal-organic framework supramolecularly assembled from a cuii dodecaborate cluster complex for selective gas separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 8145–8150 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. One-step ethylene purification from an acetylene/ethylene/ethane ternary mixture by cyclopentadiene cobalt-functionalized metal–organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 11350–11358 (2021).

Sun, F.-Z. et al. Microporous metal–organic framework with a completely reversed adsorption relationship for C2 hydrocarbons at room temperature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 6105–6111 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22171135, 22471235, both to J.D.; 22271150 to J.B.), the Outstanding Young Scientist of Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China (2025D01E06, to J.D.), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20231269, to J.D.), the State Key Laboratory of Materials-Oriented Chemical Engineering (SKL-MCE-23A18, to J.D.), and the Jiangsu Future Membrane Technology Innovation Center (BM2021804, to J.D.). We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Wei Zhou for providing valuable assistance with the DFT calculations and helpful suggestions during manuscript revision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D. and J.B. conceived this project. M.Z. and Y.F. performed the synthesis experiments. J.D. and M.Z. analyzed the experimental data. J.B. and J.D. drafted the paper with support from M.Z. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the preparation of the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jing Xiao and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, M., Duan, J., Feng, Y. et al. Fully inverse adsorption enables one-step high-purity C2H2 separation from ternary C2 mixtures in a robust porous crystal. Nat Commun 16, 10082 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65057-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65057-8