Abstract

Jupiter’s magnetosphere is often presented as a template for fast-rotating magnetospheres. Distinct from Earth-like, solar wind-driven magnetospheres, it contains an extended magnetodisk encircling the planet. Although the magnetodisk has been studied since the 1970s, its stability and non-equilibrium dynamics remain poorly understood. Here, we present observational evidence for the role of plasma pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities, including the mirror, cyclotron, and firehose instabilities, in these processes. Data from the Juno mission, supported by theoretical analysis, indicate that these instabilities determine the marginal equilibrium states towards which the magnetodisk plasma tends to evolve after being disturbed. Detailed analyses particularly highlight the role of firehose instability, which acts as a key mechanism to dissipate free energy produced by Fermi acceleration during magnetic dipolarizations. Our observations thus suggest that pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities govern the non-equilibrium evolution of the Jovian magnetodisk following disturbances, offering insights into the physics of Jupiter’s magnetodisk and magnetosphere.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The magnetosphere of Jupiter is filled with plasma primarily originating from its moon Io1. Generated near Io’s orbit at approximately 5.9 RJ (Jupiter radii, about 71492 km), the plasma is then transported radially outward, likely driven by corotation-induced interchange instability2,3,4. While it moves outward, the plasma stretches the magnetic field lines frozen within it, forming an extended magnetodisk near the equatorial plane of the magnetosphere2,3,4,5 (Fig. 1a). This magnetodisk is integral to our understanding of the Jovian system, as it is dynamically coupled with various components6,7,8,9, including Jupiter itself, its atmosphere, ionosphere, magnetosphere, and the Io torus, mediating the exchange of mass, momentum, and energy among them.

a Schematic of the magnetodisk (the blue area) in the Jupiter system. This illustration also includes Jupiter, Io, the Io torus (the orange area surrounding Io), the Jovian ionosphere (the green area surrounding Jupiter), magnetic field lines (black curves) and the Juno trajectory with respect to the magnetodisk. b Schematics of plasma instabilities and the associated VDF evolution driven by pressure anisotropy (\(A={P}_{\perp }/{P}_{\parallel }\)). VDFs with \(A > 1\) (upper subpanel) exhibit larger perpendicular phase space densities (PSDs) than parallel PSDs. If \(A\) further exceeds the mirror instability threshold (\({A}_{m}\)) or the ion cyclotron instability threshold (\({A}_{c}\)), waves are excited and \(A\) decreases. Conversely, VDFs with \(A < 1\) feature large parallel PSDs than perpendicular PSDs (bottom subpanel). If \(A\) drops below the firehose instability threshold (\({A}_{f}\)), waves are generated and \(A\) increases. c The distribution of Juno data points in \(A\)-\({\beta }_{\parallel }\) space. The upper solid curve, dashed curve, and lower solid curve represent \({A}_{m}\), \({A}_{c}\) and \({A}_{f}\). The regions unstable to the mirror/cyclotron instability and to the firehose instability are shadowed by light blue and orange colors. d Distribution of the occurrence rate (in a log scale) of Juno data points in \(A\)-\({\beta }_{\parallel }\) space. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As with any astrophysical plasma structure, the magnetodisk is usually not in equilibrium. First, both the intrinsic outward transport of plasma from Io’s orbit to the outer magnetosphere and the accompanying inward return flow4 continuously generate anisotropic velocity distribution functions (VDFs)10, driving the magnetodisk toward instability. Besides, the magnetodisk frequently experiences disturbances across a broad range of spatio-temporal scales driven by internal (i.e., satellite) or external (i.e., solar wind) sources, from localized magnetic reconnection11,12 and interchange instability2,10 to global substorm-like processes13,14. These disturbances provide free energy, driving the magnetodisk plasma away from equilibrium.

Regardless of their sources, the disturbed magnetodisk plasma subsequently undergoes relaxation towards marginal equilibrium states. Any theoretical framework developed to explain the relaxation processes must address two fundamental questions: What determines the marginal equilibrium states? How are free energies exhausted? Studies of other natural and laboratory plasmas15,16,17,18 have identified plasma microscopic instabilities as a critical element in addressing these questions. In particular, the mirror instability19,20,21, electromagnetic cyclotron anisotropy instability22 (shortly cyclotron instability), and firehose instability20,23,24 are considered particularly relevant. These instabilities, collectively referred to as pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities here, occur when particle pressure anisotropy, defined as the ratio of perpendicular pressure to parallel pressure, significantly deviates from unity (\( > \)1 for the mirror and cyclotron instabilities and \( < \)1 for the firehose instability; see Fig. 1b for illustration). As these instabilities grow, plasma waves are excited at the expense of the free energy in particle VDFs. Concurrently, particle VDFs relax20,21,24, and pressure anisotropy returns towards unity (Fig. 1b).

The potential role of pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities in Jupiter’s magnetodisk has been discussed from a theoretical perspective. For instance, ref. 25 has noted that a force-balance model of the magnetodisk fails to converge when the parallel pressure notably exceeds the perpendicular pressure, suggesting that the middle magnetosphere may be susceptible to the (fluid) firehose instability. A similar conclusion is also drawn in ref. 10, which, based on an order-of-magnitude analysis, suggested that pressure anisotropy must remain close to unity for force balance to hold in the direction perpendicular to the magnetic field. However, the role of pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities in the magnetodisk remains largely unconfirmed experimentally due to the limited availability of anisotropy measurements beyond 30 RJ: On the one hand, flyby missions like Voyager26 collected data only during single-orbit encounters. On the other hand, plasma data from the orbiter mission Galileo were largely restricted to regions near the Galilean satellites (namely, within about 30 RJ) due to instrumental and communication issues27. This situation improved with the arrival of NASA’s Juno mission28. The charged particle instruments onboard, together with the spin of the spacecraft, now provide high-quality plasma data necessary to address this question.

Here, we present a systematic investigation of Juno observations of heavy ions, defined as ions with a mass-to-charge ratio greater than 5 amu/e (primarily O+ and S++ ions29,30), which dominate both mass and energy density29,30 of the Jovian magnetodisk. Our data analysis unequivocally reveals that heavy ions are regulated by pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities, with most Juno observations of them reside in the stable region outlined by the thresholds of these instabilities. In addition, Juno detected ongoing disturbances outside the stable region. Upon detailed examination, we show that these disturbances are mainly associated with Fermi acceleration during magnetic dipolarization and are undergoing relaxation induced by the firehose instability.

Results

Pressure anisotropy of the magnetodisk heavy ions

During its prime mission, Juno followed a series of polar orbits, with perijove close to Jupiter’s surface and apojove extending beyond 100 RJ24. These orbits, combined with Jupiter’s about \({10}^{\circ }\) dipole tilt and 10 h rotation, allow Juno to periodically cross the magnetodisk (Fig. 1a). Each crossing is characterized by a reversal in the magnetic field direction (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for an example). Based on this signature, ref. 31 has identified 404 magnetodisk crossings within the 0–6 local time sector beyond 20 RJ from Juno’s first 25 orbits (see a detailed description in Methods, subsection magnetodisk crossings and Supplementary Data, sheet magnetic crossings). For each crossing, we extract Juno observations from a one-hour interval centered on the crossing time. This interval is then evenly subdivided into 24 segments, each 150 s long and hereinafter referred to as a “data point”. All observables presented below are defined with respect to the mean values over the time periods corresponding to these data points.

Measurements from the Jovian Auroral Distributions Experiment (JADE)32 and the Jupiter Energetic Particle Detector Instrument (JEDI)33 provide heavy ion VDFs spanning energies from about 10 eV to 10 MeV. We calculate the perpendicular and parallel pressure (\({P}_{\perp }\) and \({P}_{\parallel }\)) from these VDFs through numerical integration (“Methods”, subsection heavy ion pressure). The calculated pressures then provide the pressure anisotropy, \(A={P}_{\perp }/{P}_{\parallel }\) (given in Supplementary Data, sheet heavy ion anisotropy). Figure 1c shows \(A\) as a function of \({\beta }_{\parallel }={P}_{\parallel }/{P}_{B}\), where \({P}_{B}\) denotes the magnetic pressure derived from the Juno Magnetic Field Investigation (MAG)34 measurements. Figure 1d presents the corresponding occurrence rate distribution within the \(A\)-\({\beta }_{\parallel }\) space. Both Fig. 1c and d reveal a significant clustering of data points near the A = 1 line, suggesting the effects of pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities.

To further investigate these effects, we compute the thresholds for the mirror instability (\({A}_{m}\)), cyclotron instability (\({A}_{c}\)), and firehose instability (\({A}_{f}\); strictly speaking, the instability of concern here is the kinetic firehose instability, but we drop the term “kinetic” for simplicity) using parameters from Juno statistics (Methods, subsection instability thresholds). The results show that \({A}_{m}\) and \({A}_{c}\) are almost identical, so we do not distinct the cyclotron and mirror instabilities hereinafter. These thresholds delineate three regions in the \(A\)-\({\beta }_{\parallel }\) space: one unstable to the mirror/cyclotron instability (light blue-shadowed area in Fig. 1c), one unstable to the firehose instability (orange-shadowed area), and a stable region (white area). Most observations fall within the stable region. Particularly, the mirror/cyclotron instability threshold bounds the occurrence rate distribution in the \(A > 1\) half-space (Fig. 1d). These features indicate that pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities play a regulatory role in the dynamics of the magnetodisk by determining the marginal equilibrium states of the magnetodisk plasma.

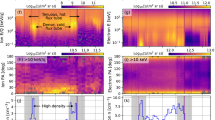

Magnetic fluctuations

However, data points outside the stable region, especially those below the firehose instability threshold (Fig. 1c, d), also exist. Further analysis reveals that they are associated with high levels of fluctuations. To illustrate this, Fig. 2a provides the distribution of the integrated amplitude (\({B}_{w}\)) of magnetic fluctuations with periods between 0.5 and 150 s (see “Methods”, subsection magnetic fluctuations). Previous studies31 have shown that the magnetic field strongly depends on radial distances, with smaller magnitudes in the outer magnetodisk. To rule out potential biases introduced by this dependence, we normalize \({B}_{w}\) by the magnetic field in the lobe regions (\({B}_{L}\); Methods, subsection magnetodisk crossings) during the same magnetodisk crossings where \({B}_{w}\) is taken. Figure 2b presents the distribution of this normalized amplitude.

a Distribution of the absolute amplitude (\({B}_{w}\)) of magnetic fluctuations in \(A\)-\({\beta }_{\parallel }\) space. b Distribution of the relative amplitude (\({B}_{w}/{B}_{L}\)) of magnetic fluctuations in \(A\)-\({\beta }_{\parallel }\) space. The curves labeled by \({A}_{m}\), \({A}_{c}\) and \({A}_{f}\) in panels a and b have the same meanings as those in Fig. 1c. c Histograms of \({B}_{w}\) in the stable region (black) and \({B}_{w}\) in the unstable region (red), with the mean values and standard deviations denoted. The stable region is defined as the areas between \({A}_{m}\) and \({A}_{f}\) in \(A\)-\({\beta }_{\parallel }\) space, while the unstable region is defined as the other areas. d Histograms of \({B}_{w}/{B}_{L}\) with the same format as panel c. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Both \({B}_{w}\) and \({B}_{w}/{B}_{L}\) are enhanced in the unstable regions, especially at low anisotropy values below the firehose instability threshold. Figures 2c, d provide quantitative confirmation of this observations. These figures show histograms of \({B}_{w}\) and \({B}_{w}/{B}_{L}\), respectively, for the data points in the stable (black) and unstable (red) regions. Evidently, the distributions for the unstable regions shift towards large values compared to those for the stable region, demonstrating that the magnetodisk plasma fluctuates more when it is unstable to pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities, particularly the firehose instability. This observation reinforces the role of pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities in relaxing the unstable magnetodisk plasma.

Magnetic dipolarization inducing firehose instability

Figures 1 and 2 indicate that the firehose instability frequently occurs in the magnetodisk. A potential free energy source driving this instability is magnetic dipolarization35, which refers to a global-scale, burst-like reconfiguration process during which magnetic field lines become more dipole-like. To explore this possibility, Fig. 3a plots the distributions of the dipolarization angle defined as \(\arctan {B}_{N}/{B}_{L}\), where \({B}_{N}\) represents the magnetic field component normal to the magnetodisk (“Methods”, subsection magnetodisk crossings). This parameter serves as a proxy for magnetic dipolarization, following previous studies35,36 at Earth (see more discussions in Supplementary Note 1). As shown in Fig. 3a, the dipolarization angles below the firehose instability threshold reach a larger value (about \({20}^{\circ }\)) compared to others, associating the occurrence of the firehose instability with magnetic dipolarization.

a Distribution of dipolarization angle in \(A\)-\({\beta }_{\parallel }\) space. The red dashed curve represents the contour of 12°. Data points inside this contour are defined as dipolarization events. b Spatial distributions of the dipolarization events (green-yellow coded contour curves) and all data points (gray-coded background). The horizontal axis represents the radial distance to Jupiter. The vertical axis represents the ratio of the local magnetic field strength \(B\) to \({B}_{L}\), which is a proxy for the vertical distance to the magnetodisk center. Each distribution is normalized so that the maximum occurrence rate equals unity. c–e Cumulative probability of \({P}_{\parallel }\), \({P}_{\perp }\) and \({P}_{B}\), respectively, of the dipolarization events (red) and the background (black). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We further examine the effects of magnetic dipolarization by comparing data points taken during magnetic dipolarization with the background. For clarity, we define the former (from now on termed as dipolarization events) as data points enclosed by the contour of \({12}^{\circ }\) dipolarization angle (red dashed curve in Fig. 3a), which corresponds to the 80th percentile of the observed dipolarization angle distribution. Compared with Fig. 2, we note that this area also exhibits high-level magnetic fluctuations. Figure 3b shows the occurrence rate of the dipolarization events (green-yellow coded contours) and the total dataset (gray-coded contours) as a function of radial distances and \(B/{B}_{L}\), where \(B\) represents local magnetic field strength. Given the current-sheet nature of the magnetodisk, \(B/{B}_{L}\) serves as a good proxy for the vertical distance to the magnetodisk31, with \(B/{B}_{L}=\)0 and 1 corresponding to the magnetodisk center and the lobes, respectively. Figure 3b clearly shows that the dipolarization events are more likely to occur near the magnetodisk boundary (i.e., at intermediate \(B/{B}_{L}\)), while the occurrence rate of the total dataset peaks in the lobes. Therefore, it would be inappropriate to directly compare the dipolarization events with the total dataset, since plasma and magnetic pressure strongly depend on the vertical distance (and also on the radial distance)29,30,31. To eliminate potential biases, we construct a background dataset from data points that are not part of the dipolarization events population but share the same spatial distributions (see more details in “Methods”, subsection background dataset).

The dipolarization events show a clear increase in \({P}_{\parallel }\) compared to the background (Fig. 3c), whereas \({P}_{\perp }\) and \({P}_{B}\) are similar between the two distributions (Fig. 3d, e). These observations thereby identify the effects of magnetic dipolarization as parallel acceleration. It is well known that magnetic dipolarization can cause parallel acceleration through Fermi acceleration-like processes37,38. Illustratively, magnetic dipolarization shortens the magnetic field lines and, consequently, the distance between the mirror points of particle bounce motion. Particles are then accelerated in the parallel direction as they bounce between the approaching mirror points. This parallel acceleration both decreases \(A\) and increases \({\beta }_{\parallel }\), moving heavy ions into the unstable region and leading to the growth of the firehose instability and waves. Besides Fermi acceleration, magnetic dipolarization could also cause betatron acceleration in the perpendicular direction37, particularly in the so-called growing flux pileup stage. This may account for the bright yellow spot seen above \(A=1\) in Fig. 3a. Nevertheless, the overall effects of perpendicular acceleration, whether due to magnetic dipolarization or other mechanisms, are weak compared to parallel acceleration, as few data points are observed beyond the mirror/cyclotron instability threshold (Fig. 1c, d). Consequently, the magnetodisk behaves asymmetrically in the half spaces above and below \(A=1\), with its relaxation predominantly occurring through the firehose instability in the \(A < 1\) half-space. In contrast, the \(A\)-\({\beta }_{\parallel }\) distribution in the solar wind15,16 and Earth’s magnetotail18 is more symmetric, indicating a more balanced role of mirror/cyclotron and firehose instabilities. These plasma systems follow different relaxation paths following disturbances.

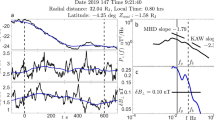

Figure 4 presents measurements of two crossings with evidence for dipolarization events. In both examples, \({B}_{w}\) increases as heavy ions become more unstable to the firehose instability (i.e., smaller \(A-{A}_{f}\)), indicating that the statistical trends also show up in individual crossings. To further validate these conclusions, we conduct a detailed dispersion relation analysis of particle distributions during periods of large \({B}_{w}\) and enhanced anisotropy in the two crossings (Supplementary Note 2), using a dispersion relation solver developed by ref. 39. The solution identifies a growing wave mode corresponding to the firehose instability at a few Hz, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, supporting the conclusions drawn from the \(A\)-\({\beta }_{\parallel }\) diagram.

Discussion

Juno observations confirm that pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities, which have been shown to play a key role in Earth’s solar wind-driven magnetosphere18,19, are also at work in Jupiter’s planet rotation-driven magnetosphere. The thresholds of these instabilities outline a stable region in phase space where the magnetodisk plasma tends to dwell. Although Juno occasionally observes the magnetodisk plasma outside this stable region, these instances are statistically associated with large magnetic fluctuations, indicating the ongoing relaxation of unstable plasma VDFs through the emission of plasma waves. Our analysis particularly highlights the role of the firehose instability, which functions as a mechanism to relax unstable plasma produced by Fermi acceleration during magnetic dipolarization. In summary, our findings provide compelling evidence for the controlling role of pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities in the non-equilibrium dynamics of the magnetodisk: These instabilities determine the marginal equilibrium states of the magnetodisk plasma and exhaust the free energy contained in unstable VDFs.

We note that the above conclusions are drawn from data in the post-midnight to dawn sector. Due to orbital precession, Juno moved out of the equatorial plane beyond ~20 RJ after entering the pre-midnight and earlier local time sectors, leaving the magnetodisk in these regions unobserved. Previous works have shown that the post-midnight sector is more active than other local times. For instance, refs. 4,10 predicted a preference for magnetic reconnection x-lines in the post-midnight sector due to the solar wind-magnetosphere interaction, a prediction later confirmed by observations40,41. Consequently, the \(A-{\beta }_{\parallel }\) diagram may differ in other local time sectors from what is observed here. For example, the occurrence rate of data points in the firehose-unstable region (Fig. 3a, red contour) may be lower, as they are mainly generated by magnetic dipolarization, which, in turn, is related to magnetic reconnection. These uncertainties may be addressed by ESA’s upcoming JUICE mission, which will provide broader local time coverage and magnetodisk observations in regions not covered by Juno.

Nevertheless, our findings demonstrate that pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities play a controlling role in the dynamics of the Jovian magnetodisk, at least in the post-midnight to dawn sector, a region previously identified as a crucial region of the Jovian magnetosphere. These observations provide a link toward a comprehensive understanding of magnetodisk physics. Studies of the magnetodisk date back at least to the 1970s, when Pioneer 10 provided the first in-situ measurements. Despite pioneering works10,11,25,42,43, the micro-physics of the non-equilibrium evolution of the magnetodisk has long been obscured by a lack of systematic plasma observations, especially pressure anisotropy. Consequently, previous considerations have primarily focused on steady states6,9,44. The Juno observations presented here reveal that the magnetodisk is inherently unsteady and time-varying, shaped by the interplay between microscopic instabilities and non-equilibrium relaxation processes. These results pave the way for developing a more comprehensive theoretical framework for the dynamics and energetics of Jupiter’s magnetodisk and magnetosphere, with implications for other rapidly rotating planetary and exoplanetary systems as well.

Methods

Magnetodisk crossings

Magnetodisk crossings are characterized by reversals in the measured magnetic field. For example, Supplementary Fig. 1 shows Juno’s observations during the crossing on August 30, 2017. One can see the direction of the magnetic field reverses at about 08:55 UT, indicating that Juno encountered the magnetodisk around this time. Based on these reversal signatures, ref. 31 identified 404 crossings in the radial extent from 20 to 100 RJ from the first 25 orbits of Juno. In this paper, we simultaneously analyze heavy ion pressure anisotropy and magnetic fluctuations during these crossings, as well as their relationship with plasma microscopic instabilities, which were not addressed in ref. 31 or in our subsequent studies45,46.

The orientation of the magnetodisk during a specific crossing can be derived from a minimum variance analysis (MVA)31 of the measured magnetic field. This analysis determines the directions along which the magnetic field changes most and least. In the case of the magnetodisk (which is a current sheet by nature), the former (L-axis) gives the direction of the magnetic field in the lobe regions, while the latter (N-axis) represents the normal to the magnetodisk. The third axis (M-axis) is along the cross-product of the N and L unit vectors and is approximately parallel to the current density in the magnetodisk31,45. Supplementary Fig. 1e–g shows the magnetic field in this local current sheet coordinate system for the crossing on August 30, 2017. As expected, the N component maintains a relatively steady, negative value, the M component oscillates around zero with a small amplitude, and the L component reverses directions during the crossing. This observation applies to all crossings identified by ref. 31. For further analysis, we define the component of the magnetic field normal to the magnetodisk (\({B}_{N}\)) by averaging the N component over a one-hour interval centered on the crossing time. The magnetic field in the lobe region (\({B}_{L}\)) is derived from a fit of the L component to a Harris current sheet model: \({B}_{L}=\tan \left[\left(t-{t}_{0}\right)/T\right]\), where \(t\) represents time, \({t}_{0}\) denotes the crossing time, and \({B}_{L}\) and \(T\) are free parameters.

Heavy ion plasma pressures

Figure 3 of ref. 46 shows that the cross-calibration between the JADE and JEDI datasets, including electrons, protons, and heavy ions, is statistically reliable. For electrons and protons, fluxes in the overlapping energy channels of the two instruments are in agreement, with no jump observed. Although there is no direct energy overlap between JADE and JEDI for heavy ions, the fluxes at the last three energy channels of JADE and the first three energy channels of JEDI (which can often be extended to a larger energy range; see Fig. 3c ref. 46) can be well fitted to a single power law, indicating consistency between the two instruments. These observations also hold for individual events. For instance, Supplementary Fig. 2 presents measurements from two example periods with evidence for dipolarization events, demonstrating the consistency between the JADE and JEDI datasets.

Therefore, we do not perform any further processing but simply combine the JADE and JEDI datasets to generate the number flux (\(J\)) sorted by energy (\(W\), from about 10 eV/e to 10 MeV/e) and pitch angle (\(\alpha\), ranging from \({0}^{\circ }\) to \({180}^{\circ }\)). Specifically, for heavy ions, we use the JAD-5-CALIBRATED-V1.0/SPECIES-5 and JED/NONPTOFXER/CDR/OXYGEN + SULFUR data from NASA’s Planetary Plasma Interactions (PDS). We then compute the number density (\(N\)), perpendicular pressure (\({P}_{\perp }\)) and parallel pressure (\({P}_{\parallel }\)) following the numerical integration method developed in ref. 46:

where \({V}_{\perp }\) and \({V}_{\parallel }\) denote the perpendicular and parallel bulk velocities. Here, the parallel and perpendicular directions are defined with respect to the local magnetic field detected by MAG. We note that even at the magnetodisk center, the magnetic field remains well above the noisy level due to the present of a nonzero normal component across the entire magnetodisk31. Hence, the parallel and perpendicular directions, as well as the corresponding observables, can be reliably determined. In the calculation, we assume a mean mass (\(m\)) of 24 amu and a mean charge of 1.5 e, which corresponds to a composition of singly charged oxygen (O+) and doubly charged sulfur (S++) of equal number density and is close to observations29,30. Previous studies do indicate the existence of other ion species (e.g., O++, S+ and S+++) in the considered mass-charge ratio range. Nevertheless, their abundances are minor and do not significantly affect the mean mass and derived quantities (see Supplementary Note 3 for an estimate of their influence).

A preliminary examination indicates that the velocities of heavy ions derived from numerical integration might suffer from large errors. In addition, numerical velocity calculation may not be reliable for both protons and heavy ions off the center of the magnetodisk, where counts are generally low. Fortunately, refs. 45,46 shows the torque balance model provides a reasonable estimate of \({V}_{\perp }\). This model indicates that the electrodynamic torque exerted by the \(J\times B\) force associated with radial electric current balances the net transport of angular momentum carried by radial mass transport. That is,

where \({I}_{r}\) represents radial electric current, \({B}_{n}\) represents the magnetic field component normal to the magnetodisk, and \(\dot{M}\) denotes the radial mass transport rate. Refs. 45,46 shows \({V}_{\perp }\) derived from Eq. 4, with \({I}_{r}\) from ref. 45 and \({B}_{n}\) from ref. 31 (both taken from Juno statistics) and \(\dot{M}=1500\) kg/s, fits ion velocities derived from JADE data using a forward modeling method30 well. Therefore, \({V}_{\perp }\) obtained in this way is used in Eq. 2 Additionally, we set \({V}_{\parallel }=0\) in Eq. 3 as Juno observations suggest that the field-aligned velocity component is negligible in general47.

Magnetic fluctuations

We first apply a high-pass filter (period\( < 150\) s) to the observed magnetic field to remove variations associated with the motion of Juno relative to the magnetodisk (e.g., magnetodisk crossings and flapping motion). Then, a Fast Fourier transformation is employed to calculate the power spectral density of the filtered magnetic field. By integrating the results over 6.7 mHz (corresponding to 150 s) to 4 Hz, we obtain the integrated power of magnetic fluctuations. The square root of this value gives the absolute amplitude (\({B}_{w}\)) of magnetic fluctuations analyzed in the main text.

Instability thresholds

Recent theoretical studies have highlighted the role of nonlinear effects, particularly at large wave amplitudes, in governing the growth and saturation of pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities20,21,24. These nonlinear processes influence not only the saturated fluctuation amplitudes and spectral features but also the timescales and relaxation pathways by which unstable plasmas evolve toward marginal stability. As an example of the latter, numerical simulations20 have shown that pressure anisotropy is regulated by particle scattering off smaller-scale fluctuations in the nonlinear firehose instability and by a balance between particle trapping within magnetic mirrors and scattering at the mirrors’ edges in the nonlinear mirror instability. These nonlinear mechanisms may determine the observed fluctuation amplitudes within the unstable regimes of the \(A\)-\({\beta }_{\parallel }\) space, as well as the formation of fine structures in particle VDFs.

The primary objective of this study, however, is to evaluate observationally whether the pressure anisotropy and magnetic fluctuations of Jupiter’s magnetodisk are organized by pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities in parameter space. To this end, we ignore the effects of nonlinear dynamics, following previous work on the solar wind15,16. Instead, we apply thresholds based on linear instability growth rates, which provide a first-order approximation of the boundaries delineating unstable regions in phase space. This approach facilitates direct comparison with Juno’s statistical measurements and is supported by the agreement between theoretical predictions and observational results (Figs. 1 and 2).

More specifically, to determine the thresholds of the mirror, cyclotron and firehose instabilities, we consider a plasma consisting of Maxwellian electrons (density \({N}_{e}\) and temperature \({T}_{e}\)), Maxwellian protons (density \({N}_{p}\) and temperature \({T}_{p}\)) and bi-Maxwellian heavy ions (density \({N}_{h}\), parallel temperature \({T}_{h\parallel }\) and perpendicular temperature \({T}_{h\perp }\)). In this context, \(A={T}_{h\perp }/{T}_{h\parallel }\). The parameters are taken from the statistical study44 at a radial distance of 50 RJ obtained by Juno: \({N}_{p}=0.32{N}_{h}\), \({N}_{e}=1.32{N}_{h}\), \({T}_{p}=8.5\) keV, \({T}_{e}=2.3\) keV, \({T}_{h\perp }=17.3\) keV and \({P}_{B}=8.2\times {10}^{-3}\) nPa. We calculated the maximum growth rate (\(\gamma\)) of the three instabilities in the region \(0.1 < {\beta }_{\parallel } < 100\) and \(0.1 < A < 5\) using the dispersion relation solver Waves in Homogeneous Anisotropic Magnetized Plasma (WHAMP)48. The relation \(\gamma={10}^{-3}{\omega }_{{cp}}\) (proton gyro-frequency) is then fitted for the three instabilities in the following equation15,16:

where \(i=m,c,f\) for the mirror, cyclotron and firehose instabilities, and \({a}_{i}\) and \({b}_{i}\) are the fitted parameters. The fitting results are (\({a}_{m}=\)1.03, \({b}_{m}=\)0.48), (\({a}_{c}=\)0.81, \({b}_{c}=\)0.32), and (\({a}_{f}=-\)0.52, \({b}_{f}=\)0.36). Strictly speaking, these fitted parameters are not constant and depend on parameters like \({T}_{e}\) and \({T}_{p}\), which vary at radial distances. Nevertheless, testing indicates that the fitting results are not sensitive to parameter variations within the range of Juno statistics. For example, using parameters at 80 RJ, where \({P}_{B}\) and \({T}_{h\perp }\) are 56% and 123% of those at 50 RJ, respectively, the threshold for the firehose instability becomes (\({a}_{f}=-\)0.56, \({b}_{f}=\)0.36). These values are very close to those obtained with parameters at 50 RJ; when plotted on the \(A\)-\({\beta }_{\parallel }\) plane, the two curves are nearly indistinguishable. Similar behavior is observed for the cyclotron and mirror instabilities as well.

Both the mirror and cyclotron instabilities arise in the A > 1 regime. These two modes exhibit markedly different characteristics, particularly in terms of phase speed: The mirror mode is non-propagating, while the cyclotron mode propagates through the plasma with a finite phase speed. Consequently, they resonate with particles of different energies, which in turn affects both the time scale and pathway of the relaxation of unstable plasmas. However, from the perspective of linear instability theory, their instability thresholds are nearly identical, as shown, e.g., in Fig. 1c. Therefore, in this study, we address the two instability modes at the same time when comparing theoretical instability thresholds with observations.

Background dataset

To investigate the effects of magnetic dipolarization, we compare events with evidence for dipolarization events (data points circled by the red dashed contour in Fig. 3a) with the background. Previous studies have shown that plasma pressure and magnetic pressure depend on the positions where the observations are made. To eliminate the effects of this dependence, we construct a background dataset with the same spatial distributions as events with evidence for dipolarization events using the following method. First, we determine the spatial distribution of dipolarization events (the green-yellow coded contours in Fig. 3b). Then, we define the background dataset as the data points that meet two criteria: (1) they are located within the 0.1-level contour of the dipolarization event distribution shown in Figs. 3b and (2) they reside within the stable region depicted in Fig. 1c.

Data availability

The Juno/MAG data (PDS volume FGM-CAL-V1.0/SS), the Juno/JADE data (PDS volume JAD-5-CALIBRATED-V1.0/ION), and the Juno/JEDI data (PDS volume JED−3-CDR-V1.0/TOFXE) have been deposited in the NASA Planetary Plasma Interactions Node database under accession code https://pds-ppi.igpp.ucla.edu/search/default.jsp. The list of Juno magnetodisk crossings is provided in the Supplementary Data file. Source data are provided in this paper.

Code availability

Juno data were loaded, analyzed, and visualized using SpacePy (https://spacepy.github.io/install.html), NumPy (https://numpy.org/install/), SciPy (https://scipy.org/install/), and Matplotlib (https://matplotlib.org/) for Python. The dispersion relation solvers WHAMP and BO-Arbitrary are available from Ref. 48 and39, respectively, as provided by their authors.

References

Thomas, N., Bagenal, F., Hill, T. & Wilson, J. Io’s Neutral Clouds, Plasma Torus, Magnetospheric Interaction Magnetos. (2004).

Pontius, D. Jr & Hill, T. Rotation driven plasma transport: The coupling of macroscopic motion and micro diffusion. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 94, 15,041–15,053 (1989).

Caudal, G. A self-consistent model of jupiter’s magnetodisc including the effects of centrifugal force and pressure. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 91, 4201–4221 (1986).

Vasyliunas, V. M. Plasma distribution and flow. Phys. Jovian Magnetos. 1, 395–453 (1983).

Connerney, J., Timmins, S., Herceg, M. & Joergensen, J. A Jovian magnetodisc model for the juno era. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 125, e2020JA028,138 (2020).

Cowley, S. & Bunce, E. Origin of the main auroral oval in jupiter’s coupled magnetosphere–ionosphere system. Planet. Space Sci. 49, 1067–1088 (2001).

Wang, Y. et al. A preliminary study of magnetosphere-ionosphere-thermosphere coupling at Jupiter: Juno multi-instrument measurements and modeling tools. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 126, e2021JA029,469 (2021).

Al Saati, S. et al. Magnetosphere-ionosphere-thermosphere coupling study at jupiter based on juno’s first 30 orbits and modeling tools. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 127, e2022JA030,586 (2022).

Devinat, M., Blanc, M. & André, N. A self-consistent model of radial transport in the magnetodisks of gas giants including interhemispheric asymmetries. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 129, e2023JA032,233 (2024).

Kivelson, M., and Southwood, D. Dynamical consequences of two modes of centrifugal instability in Jupiter’s outer magnetosphere. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 110, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JA011176 (2005).

Russell, C., Khurana, K., Huddleston, D. & Kivelson, M. Localized reconnection in the near Jovian magnetotail. Science 280, 1061–1064 (1998a).

Zhao, J. et al. Dayside magnetodisk reconnection in Jovian system: Galileo and Voyager observation. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 129, e2023JE008,240 (2024).

Krupp, N. et al. Dynamics of the Jovian magnetosphere. Jupit. Planet Satell. Magnetos. 1, 617–638 (2004).

Kronberg, E. et al. Mass release at jupiter: Substorm-like processes in the Jovian magnetotail. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 110, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JA010777 (2005).

Hellinger, P., Trávníček P., Kasper J. C. & Lazarus A. J. Solar wind proton temperature anisotropy: Linear theory and Wind/SWE observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL025925 (2006).

Bale, S. D. et al. Magnetic fluctuation power near proton temperature anisotropy instability thresholds in the solar wind. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 211101 (2009)

Gary, S. P., Thomsen, M. F., Yin, L. & Winske, D. Electromagnetic proton cyclotron instability: Interactions with magnetospheric protons. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 100, 21,961–21,972 (1995).

Wu, M. et al. The proton temperature anisotropy associated with bursty bulk flows in the magnetotail. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 118, 4875–4883 (2013).

Hasegawa, A. Drift mirror instability in the magnetosphere. Phys. Fluids 12, 2642–2650 (1969).

Kunz, M. W., Schekochihin, A. A. & Stone, J. M. Firehose and mirror instabilities in a collisionless shearing plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 205003 (2014).

Rincon, F., Schekochihin, A. A. & Cowley, S. C. Non-linear mirror instability. Monthly Not. R. Astronomical Soc. Lett. 447, L45–L49 (2015).

Gary, S. P. & Lee, M. A. The ion cyclotron anisotropy instability and the inverse correlation between proton anisotropy and proton beta. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 99, 11,297–11,301 (1994).

Quest, K. & Shapiro, V. Evolution of the fire-hose instability: Linear theory and wave-wave coupling. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 101, 24,457–24,469 (1996).

Bott, A. F., Kunz, M. W., Quataert, E., Squire, J., & Arzamasskiy, L. Thermodynamics and collisionality in firehose-susceptible high-beta plasmas. J. Plasma Phys. 91, E136 (2025).

Nichols, J. D., Achilleos, N. & Cowley, S. W. A model of force balance in Jupiter’s magnetodisc including hot plasma pressure anisotropy. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 120, 10–185 (2015).

Paranicas, C. P., Mauk, B. H. & Krimigis, S. M. Pressure anisotropy and radial stress balance in the Jovian neutral sheet. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 96, 21135–21140 (1991).

Bagenal, F., Wilson, R. J., Siler, S., Paterson, W. R. & Kurth, W. S. Survey of Galileo plasma observations in Jupiter’s plasma sheet. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 121, 871–894 (2016).

Bagenal, F. et al. Magnetospheric science objectives of the Juno mission. Space Sci. Rev. 213, 219–287 (2017).

Wang, J.-Z. et al. Radial and vertical structures of plasma disk in Jupiter’s middle magnetosphere. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 129, e2024JA032,715 (2024).

Kim, T. K. et al. Survey of ion properties in Jupiter’s plasma sheet: Juno JADE-I observations. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 125, e2019JA027,696 (2020).

Liu, Z.-Y. et al. Statistics on Jupiter’s current sheet with Juno data: Geometry, magnetic fields and energetic particles. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 126, e2021JA029,710 (2021).

McComas, D. et al. The Jovian auroral distributions experiment (JADE) on the Juno mission to Jupiter. Space Sci. Rev. 213, 547–643 (2017).

Mauk, B. et al. The Jupiter energetic particle detector instrument JEDI) investigation for the Juno mission. Space Sci. Rev. 213, 289–346 (2017).

Connerney, J. et al. The Juno magnetic field investigation. Space Sci. Rev. 213, 39–138 (2017).

Baumjohann, W. et al. Substorm dipolarization and recovery. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 104, 24995–25000 (1999).

Huang, C. S. et al. Periodic magnetospheric substorms: Multiple space-based and ground-based instrumental observations. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 108, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JA009992 (2003).

Fu, H. S., Khotyaintsev, Y. V., André, M. & Vaivads, A. Fermi and betatron acceleration of suprathermal electrons behind dipolarization fronts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL048528 (2011).

Oka, M. et al. Electron power-law spectra in solar and space plasmas. Space Sci. Rev. 214, 82 (2018).

Xie, H. Efficient framework for solving plasma waves with arbitrary distributions. Phys. Plasmas. 32, 060702 (2025).

Vogt, M. F., Kivelson, M. G., Khurana, K. K., Joy, S. P., & Walker, R. J. Reconnection and flows in the Jovian magnetotail as inferred from magnetometer observations. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 115, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JA015098 (2010).

Vogt, M. F. et al. Magnetotail reconnection at Jupiter: A survey of Juno magnetic field observations. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 125, e2019JA027486 (2020).

Russell, C., Huddleston, D., Khurana, K. & Kivelson, M. The fluctuating magnetic field in the middle Jovian magnetosphere: Initial Galileo observations. Planet. Space Sci. 47, 133–142 (1998).

Russell, C., Huddleston, D., Khurana, K. & Kivelson, M. Waves and fluctuations in the Jovian magnetosphere. Adv. Space Res. 26, 1489–1498 (2000).

Caudal, G. & Connerney, J. Plasma pressure in the environment of Jupiter, inferred from voyager 1 magnetometer observations. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 94, 15,055–15,061 (1989).

Liu, Z.-Y., Blanc, M. & Zong, Q.-G. A Juno-era view of electric currents in Jupiter’s magnetodisk. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 128, e2023JA031,436 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Juno observations of Jupiter’s magnetodisk plasma: Implications for equilibrium and dynamics. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 129, e2024JA032976 (2024).

Wilson, R., Jovian current disk crossings as observed by Juno JADE-I. Icarus 413, 116006 (2024).

Rönnmark, K. WHAMP-Waves in Homogeneous, Anisotropic, Multicomponent Plasmas.(1982).

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to NASA and to the contributing institutions that have made the Juno mission possible, and to all institutions supporting the development, operation, and data analysis of the Juno instrument suite used in this study: MAG, JADE and JEDI. The co-authors at IRAP acknowledge the support of CNES for the Juno and JUICE missions and CNRS/INSU programs of planetology and heliophysics. Z.Y.L. acknowledges the support of CNES for his work at IRAP. F.A. acknowledges support from NASA’s New Frontiers Program for Juno through contract NNM06AA75C.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Y.L. conceived the project, performed the analysis of Juno data, calculated instability thresholds, and wrote the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors. N.A. and M.B. supervised the project and contributed to the Juno data analysis. S.W. assisted in calculating instability thresholds. F.A., B.M., J.E.P.C., and S.B. contributed to the Juno data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Adnane Osmane, and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, ZY., André, N., Blanc, M. et al. Pressure anisotropy-driven instabilities regulate the jovian magnetodisk. Nat Commun 16, 9886 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65064-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65064-9