Abstract

Recent years have seen remarkable progress in three-dimensional (3D) integration of non-silicon materials, enabling the convergence of diverse functionalities such as sensing, storage, and computing beyond mere transistor scaling. This advancement accelerates edge intelligence by enabling more efficient information processing at the source with reduced latency and power consumption. In this work, we contribute to this rapidly evolving landscape by demonstrating reservoir computing through 3D integration of In2Se3-based photodetectors with MoS2-based memtransistors. Our top tier exploits the variation in photoresponse of an optical reservoir constructed using flakes of different thicknesses of In2Se3. The bottom tier deploys programmable MoS2 memtransistors to convert the photocurrent into photovoltages which are subsequently processed by a trained readout circuit that is also based on MoS2 memtransistors. Notably, the physical proximity between sensors and computing elements is less than 50 nm, surpassing current state-of-the-art packaging solutions. We also demonstrate the benefits of near-sensor information processing for better photoresponse calibration and to achieve higher photoresponse speed. Overall, our 3D stack, with its near-sensor and in-memory compute capability, marks a significant milestone in vertically stacked functional layers composed of heterogeneous materials beyond silicon for edge applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Three-dimensional (3D) integration is a promising approach for enhancing near-sensor computing applications, offering significant improvements in performance, efficiency, and miniaturization1,2,3,4,5,6. This advanced technology involves stacking and interconnecting multiple layers of semiconductor devices, sensors, and circuits vertically, creating a compact and highly integrated system. Currently, there are two distinct approaches to 3D integration: packaging and monolithic integration5,7,8. The packaging method assembles independently fabricated components within a package, but this approach can suffer from increased via length, limited via density, and constrained performance improvements in latency and bandwidth. In contrast, the monolithic 3D integration (M3D) method employs fabrication techniques to stack components directly on top of each other through vias on a single unified chip, offering a more efficient approach with a smaller footprint, reduced parasitic effects, and better energy efficiency.

There have been several recent demonstrations in M3D integration, including 3D stacking of 2D material-based transistors1,9, prototype systems that combine CNT transistors and resistive memory devices10,11, and hybrid microchips that integrate 2D materials with CMOS technology12,13,14,15,16,17. However, the full potential of M3D integration of heterogeneous materials remains untapped18. This integration is anticipated to be especially advantageous for neuromorphic edge applications, where computing needs to occur close to the sensor19,20.

In this work, we accelerate reservoir computing (RC), a powerful computational paradigm for processing time-series data, using M3D integration of In2Se3 photodetectors and MoS2 memtransistors that naturally meet the criteria for a physical reservoir. Specifically, the upper tier leverages the photoresponse variations from an optical reservoir built with In2Se3 flakes of varying thicknesses, while the lower tier employs programmable MoS2 memtransistors to convert photocurrent into photovoltages. These photovoltages are then processed by a trained readout circuit, based on MoS2 memtransistors. Remarkably, the sensors and computing elements are physically positioned within 50 nm of each other, exceeding the capabilities of current state-of-the-art packaging solutions. Additionally, we highlight the advantages of near-sensor information processing, which enhances photoresponse calibration and achieves faster photoresponse speeds. In short, we demonstrate the benefits of near-sensor and in-memory computing using 3D architecture for better information processing and for accelerating edge intelligence.

Results

M3D integration of In2Se3 photodetector and MoS2 memtransistors

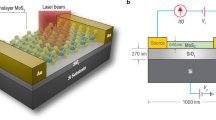

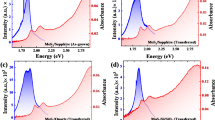

Figure 1a, b, respectively, show the schematic and cross-sectional high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) images of our 3D integrated In2Se3 photodetector and MoS2 memtransistor acquired through scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) was used to obtain the elemental distribution of the 3D integrated device stack as depicted in Fig. 1c, d, and Supplementary Fig. 1. MoS2 films utilized in this study were grown on epi-ready 2-inch c-plane sapphire (α-Al2O3) substrates using metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD). In contrast, In2Se3 was exfoliated from a bulk single-crystal using Scotch tape. The growth parameters and detailed synthesis steps are outlined in our previous studies (also see Methods section)1,21,22,23,24,25. Supplementary Fig. 2a–d, respectively, show the optical images of a representative MoS2 memtransistor and In2Se3 photodetector and the corresponding Raman spectra obtained from the channel using a 532 nm laser. The in-plane \({E}_{2g}^{1}\) (387 cm−1) and out-of-plane \({A}_{1g}\) (404 cm−1) vibrational modes with a separation of 17 cm−1 observed in the Raman spectra for MoS2 confirm the monolayer nature of the film26. Similarly, for In2Se3, the Raman peaks obtained at 89, 103, 180, 196, and 204 cm–1 are attributed to E, A (LO + TO), A (LO), A (TO), and A (LO) phonon modes, respectively27. Specifically, the peak obtained at 89 cm–1 can be considered as an indication of 2H stacking within the In2Se3 crystal. Additionally, the presence of the A(LO) and A(TO) modes at 180 and 196 cm–1 results from the LO–TO splitting and indicates a lack of inversion symmetry in the R3m structure. These Raman results confirm that the In2Se3 in this work has an α-phase crystal structure.

a Schematic and (b) cross-sectional scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) images of our 3D integrated In2Se3 photodetector and MoS2 memtransistor. c Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) results illustrating the elemental distribution within the white-dotted box region of the 3D integrated device stack depicted in (b). d Enlarged EDS elemental maps showing the distributions of In, Se, Mo, and S. e Photoresponse of 30 different In2Se3 photodetectors obtained using a source-to-drain bias of 1 V for an input optical stimulus of \({{{\rm{P}}}}_{{{\rm{IN}}}}\) = 10−10 Wm−2. f Extracted responsivity (\({{{\rm{R}}}}_{{{\rm{PH}}}}\)) and (g) specific detectivity (\({{{\rm{D}}}}^{*}\)) values for each of these photodetectors. h Transfer characteristics of 100 MoS2 memtransistors at a constant drain voltage (\({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{DS}}}}\)) of 1 V. Corresponding distribution of (i) field-effect electron mobility (\({{{\rm{\mu }}}}_{{{\rm{FE}}}}\)), ( j) subthreshold slope (SS), and (k) threshold voltage (\({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{TH}}}}\)) for these 100 devices. l Post-program and (m) post-erase transfer characteristics of a representative MoS2 memtransistor, measured at \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{DS}}}}\) = 1 V after applying negative and positive back-gate voltage pulses of magnitude 5 V to 12 V, with a constant pulse width of 10 ms. n Analog programming and non-volatile retention characteristics for five distinct conductance states.

Following the material characterization, the 3D stack was fabricated on a commercially available substrate consisting of 285 nm SiO2 on p++ Si. It is important to note that other substrates compatible with our fabrication process flow can also be used. The monolayer MoS2 memtransistor-based compute circuits are allocated to the bottom tier, while the In2Se3 photodetectors are placed on the top tier. We followed a sequential fabrication method, as depicted schematically in Supplementary Fig. 3. Initially, local back-gate electrodes (5 nm Ti and 15 nm Pt) were patterned using electron beam (e-beam) lithography, followed by metal deposition through e-beam evaporation. Subsequently, a 15 nm/3 nm/7 nm stack of Al2O3/HfO2/Al2O3 was deposited using atomic layer deposition (ALD) to serve as the floating-gate (FG) dielectric stack for the bottom-tier MoS2 memtransistors. As we will elucidate later, this stack enables non-volatile and analog programming of the MoS2 memtransistors. Next, the MOCVD-grown monolayer MoS2 film was transferred from the growth substrate to the prefabricated local back-gate islands using a polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)-assisted transfer process. The MoS2 film was patterned using e-beam lithography and etched with sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) to define the channel areas. Next, the source/drain contacts for individual MoS2 memtransistors and the connections for the readout circuit were delineated through e-beam lithography, followed by the deposition of 40 nm Ni and 30 nm Au. Finally, a lift-off process completed the fabrication for the bottom-tier MoS2 devices and circuits.

Next, a 50 nm layer of Al2O3 was deposited using atomic layer deposition (ALD) to serve as the interlayer dielectric (ILD), separating the top and bottom tiers. The via access to the necessary source/drain and gate electrodes for the bottom-tier MoS2 memtransistors was then patterned using e-beam lithography, followed by etching of the ILD with a BCl3 plasma. In2Se3 flakes were subsequently placed on top of the ILD using mechanical exfoliation. Due to the random nature of the exfoliation process, flakes were found in various locations. However, we identified flakes that were physically close to the MoS2 memtransistors for constructing the stacked devices. Next, the source/drain contacts for each In2Se3 photodetector, their connection to the inter-tier vias, and the vias were fabricated by patterning with e-beam lithography, followed by e-beam evaporation of 40 nm Ni and 30 nm Au. The metal stack thickness was chosen to be more than the ILD thickness to ensure proper via connection between the tiers. A final lift-off process to remove the excess metal concluded the fabrication of the 3D stack. A significant aspect of this approach of fabricating the In2Se3-MoS2 3D stack is that the entire fabrication process is maintained within a thermal budget of 180 °C. This temperature range ensures compliance with back-end-of-line (BEOL) requirements, enabling the addition of more tiers without compromising the integrity of the lower ones.

Initially, In2Se3-based photodetectors were examined for their optoelectronic response. The photocurrents for different devices were recorded by illuminating the sample with a blue LED (λ = 450–455 nm) at a fixed voltage (VLED = 4 V). Figure 1e presents the photoresponse of 30 different In2Se3 photodetectors obtained using a source-to-drain bias of 1 V. The current through the photodetectors under dark (IDark) and in the presence of light (ILight) was found to be different across the devices. This device-to-device variation can be primarily attributed to the varying thicknesses of the In2Se3 flakes, with thicker flakes generally contributing to higher current. Figure 1f, g, respectively, show the extracted responsivity (RPH), defined as the ratio of photocurrent (\({I}_{{PH}}={I}_{{Light}}-{I}_{{Dark}}\)) to the input optical power (PIN), and for each of these photodetectors. We found that the RPH values range from ~ 2 A/W to ~ 8500 A/W, consistent with previous literature on In2Se328,29. Similarly, Fig. 1g shows the extracted specific detectivity (D*) values for each of these photodetectors. The lower D* values can be attributed to higher dark current in In2Se3 devices. As we will show later, integrating a programmable MoS2 memtransistor with In2Se3 photodetector to convert the photocurrent into corresponding photovoltage offers the unique advantage of mitigating the response variation in RPH and D*.

Note that In2Se3 was chosen as the photodetector material owing to its ability to generate photocurrent by utilizing photoconductivity changes. This contrasts with most other 2D materials that utilize the photogating effect as their primary mechanism for photocurrent generation23. The photogating effect, while useful in some contexts30,31, can introduce complexities such as longer response times and potential stability issues due to the involvement of trap states and localized charges. In contrast, photoconductance change enables faster response times and higher sensitivity, making it preferable for applications requiring high-speed and high-fidelity light detection. Additionally, In2Se3 offers the significant advantage of being a direct bandgap semiconductor regardless of its thickness, unlike most other 2D materials, which exhibit direct band gaps only at the monolayer limit. This property allows In2Se3 to absorb more light compared to other 2D materials, enhancing its effectiveness as a photodetector.

Next, the transfer characteristics i.e., the plot of drain current (IDS) versus the back-gate voltage (VBG) of 100 MoS2 memtransistors in the bottom tier of the 3D stack, were acquired at a constant drain voltage (VDS) of 1 V, as shown in Fig. 1h. Here, all MoS2 memtransistors have a channel length (LCH) and width (WCH) of 500 nm and 1 µm, respectively. Figure 1i–k, respectively, show the distribution of field-effect electron mobility (μFE) extracted from peak transconductance, subthreshold slope (SS) extracted for three orders of magnitude change in IDS, and threshold voltage (VTH) extracted using the iso-current method at 100 nA for these 100 devices. The median values for μFE, SS, and VTH were found to be ~3.5 cm2/Vs, ~210 mV/dec, and ~1.15 V, respectively. The ON-current values are comparable to those reported in recent literature for MoS2 FETs at similar carrier concentrations and \({L}_{{CH}}\)32. While enhancing the performance of MoS2 memtransistors for future M3D ICs is a desirable goal, the current performance level is sufficient for the intended applications in this work.

A notable feature of our MoS2 memtransistors is their programmability, which enables circuit reconfiguration based on specific application requirements. This is achieved through the FG stack composed of Al2O3/HfO2/Al2O3, which facilitates analog programming and non-volatile storage of conductance states. In this structure, the HfO2 layer, with its smaller bandgap, acts as a charge trapping layer between two Al2O3 layers with larger band gaps. This configuration is clearly illustrated in the schematic, cross-sectional STEM-HAADF image, and EDS elemental mapping shown in Fig. 1a–c. Furthermore, Fig. 1l, m displays the post-program and post-erase transfer characteristics of a representative MoS2 memtransistor, measured at \({V}_{{DS}}\) = 1 V after applying negative and positive back-gate voltage pulses. The magnitude of programming/erase pulses ranged from 4 V to 12 V, with a constant pulse width of 10 ms. Figure 1n shows analog programming and non-volatile retention characteristics for five distinct conductance states, each maintained for 300 seconds. Supplementary Fig. 4 presents the programming endurance over 109 cycles. As we will demonstrate in the next section, the reconfigurability of conductance states in MoS2 memtransistors enables dynamic and on-chip calibration of the photoresponse from In2Se3 photodetectors.

Near-sensor compute for photoresponse calibration

While the device-to-device variation in photoresponse is desirable for our proposed RC application, the observed range of photocurrent across different In2Se3 flakes varied by four orders of magnitude, from a few hundred picoamperes to a few microamperes, as reflected in their corresponding \({R}_{{PH}}\) values. This wide variation complicates subsequent circuit processing. To mitigate this, the \({I}_{{PH}}\) can be converted into photovoltage (\({V}_{{PH}}\)) by connecting a load resistor in series with the In2Se3 photodetector, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5a. Here, the output voltage (\({V}_{{Out}}\)) is measured at the common node, and the difference between the readings under light and dark conditions constitutes the photovoltage (\({V}_{{PH}}={V}_{{Out},L}-{V}_{{Out},D}\)). Note that although this bounds the \({V}_{{PH}}\) values between \({V}_{{GND}}\) and \({V}_{{DD}}\), it still allows the device-to-device variation to be reflected. Moreover, voltage outputs are preferred in ICs due to their ease of integration, power efficiency, and noise immunity, which facilitate simpler and more robust circuit designs and support both analog and digital processing. However, to obtain the best photovoltage response, the resistance of the In2Se3 photodetector (\({R}_{{PD}}\)) and the load resistor (\({R}_{L}\)) must be matched. Supplementary Fig. 5b shows the \({V}_{{PH}}\) response obtained from the same In2Se3 photodetector under identical optical stimuli for three different scenarios: \({R}_{{PD}}\gg {R}_{L}\), \({R}_{{PD}}\ll {R}_{L}\), and \({R}_{{PD}}\approx {R}_{L}\). Clearly, maximum \({V}_{{PH}}\) response is recorded when \({R}_{{PD}}\approx {R}_{L}\). However, due to the wide range of \({R}_{{PD}}\) values associated with the In2Se3 photodetectors, designing a matching load resistor becomes challenging without altering its footprint.

In comparison to resistors, a transistor is a better choice, as its resistance can be tuned by several orders of magnitude by applying a gate bias. Figure 2a, b, respectively, illustrate the different biasing states (\({V}_{{BG}}\)) of a MoS2 transistor and the corresponding photovoltage response measured from the In2Se3 photodetector, connected through the via in our 3D stack, for an input optical stimulus of \({P}_{{IN}}\) = 10−10 Wm−2. Supplementary Fig. 6 shows the responses from two other In2Se3 photodetectors under identical optical stimuli, each connected in series with the corresponding MoS2 transistor. We recorded these responses under a \({V}_{{DD}}\) = 1 V. It is important to note that the \({R}_{{PH}}\) values for each of these three In2Se3 photodetectors were significantly different, approximately ~1000 A/W, ~180 A/W, and ~18 A/W, respectively. However, as shown in Fig. 2c, the extracted \({V}_{{PH}}\) plotted against \({V}_{{BG}}\) follows a similar non-monotonic trend for all three devices, despite each achieving its peak \({V}_{{PH}}\) values for different \({V}_{{BG}}\) values. This observation indicates that by adjusting the gate bias, we can achieve load matching for each In2Se3 photodetector, regardless of their varying photoresponse. Furthermore, unlike a resistor, there is no need to alter the physical footprint or design of the MoS2 transistors.

a Different biasing states (\({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{BG}}}}\)) of a MoS2 transistor and (b) corresponding photovoltage response measured from the In2Se3 photodetector, connected through the via in our 3D stack, for an input optical stimulus of \({{{\rm{P}}}}_{{{\rm{IN}}}}\) = 10−10 Wm−2 and \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{DD}}}}\) = 1 V. c Extracted \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{PH}}}}\) plotted against \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{BG}}}}\) for three pairs of In2Se3/MoS2 stacked devices with different \({{{\rm{R}}}}_{{{\rm{PH}}}}\) values. Similar \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{PH}}}}\) response is seen in all devices indicating that by adjusting the gate bias, we can achieve load matching for each In2Se3 photodetector, regardless of their varying photoresponse. d Different programmed conductance state of a MoS2 memtransistor and (e) corresponding responses from the In2Se3/MoS2 stacked photodetectors under identical optical stimuli, measured using \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{BG}}}}\) = −1 V and \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{DD}}}}\) = 1 V. f Extracted \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{PH}}}}\) plotted against the programmed conductance values demonstrating that memtransistors can simplify circuit biasing due to their non-volatile and analog programming capabilities, allowing each In2Se3/MoS2 stacked device to achieve similar \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{PH}}}}\) in response to identical optical stimuli with identical biasing.

While the above demonstration clearly highlights the advantage of using a transistor over a resistor, managing different biases for each MoS2 memtransistor becomes complicated when many devices are involved. The key advantage of using a memtransistor over a conventional transistor is that the conductance of the memtransistor can be programmed in a non-volatile manner, allowing load resistance to be matched for a given \({V}_{{BG}}\). Figure 2d, e, respectively, show different programmed conductance states of a MoS2 memtransistor and corresponding responses from the In2Se3/MoS2 stacked photodetectors under identical optical stimuli, measured using \({V}_{{BG}}\) = −1 V and \({V}_{{DD}}\) = 1 V. Figure 2f shows the extracted \({V}_{{PH}}\) plotted against the programmed conductance values, resembling Fig. 2c. This demonstrates that memtransistors can simplify circuit biasing due to their non-volatile and analog programming capabilities, allowing each In2Se3/MoS2 stacked device to achieve similar \({V}_{{PH}}\) in response to identical optical stimuli with identical biasing. It is important to mention that the performance of the MoS₂ memtransistor remains unaffected by light illumination under these operating conditions. This is because MoS2 exhibits photogating effects primarily when the device is in the OFF state, where the channel conductance is low and trap states at the dielectric interface or within the semiconductor can capture photoexcited carriers. These trapped charges modulate the threshold voltage (\({V}_{{TH}}\)), effectively shifting the transfer characteristics.

However, in our case, the memtransistor was predominantly operated in the ON state, where the channel is already highly conductive. Under these conditions, the photogenerated carriers have a negligible effect on the device performance since the existing high carrier density in the ON state minimizes the relative contribution of any additional carriers introduced by light. Furthermore, the availability of empty trap states is minimal to alter the \({V}_{{TH}}\). By ensuring operation in the ON state, the MoS2 memtransistor remains insensitive to light-induced effects.

The above demonstration underscores the significance of integrating in-memory compute elements with sensors, offering greater design flexibility and enhanced robustness in managing device-to-device variations compared to traditional designs. Notably, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7, this approach is also effective in mitigating temporal drift in photodetector responses. We conducted an aging experiment by applying a 5 V source-to-drain voltage to an In2Se3 photodetector for durations ranging from 100 to 10,000 seconds. This voltage stress resulted in visible changes in the photoresponse, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7a. While we observed an increase in photocurrent, the fall time degraded. We attribute this to the formation of defects in In2Se3, which may enhance photocurrent by allowing more photocarrier capture, but slow down the response as trapped carriers decay slowly. Despite these aging effects, we recalibrated the photodetector’s response by adjusting the conductance of the MoS2 memtransistor connected as a load resistor. This adjustment, illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 7b, demonstrates the programming capability of the MoS2 memtransistor, allowing us to mitigate the temporal variations in the In2Se3 photodetector. This approach again highlights the importance of integrating programmable components to maintain optimal device performance and ensure long-term reliability and stability in photodetector systems.

Finally, to assess the dynamic range of our stacked In2Se3/MoS2 photodetectors, we conducted experiments using various light intensities from blue (λ = 450–455 nm), green (λ = 515–525 nm), and red (λ = 620–625 nm) LEDs and recorded the output voltage response, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8a–c, respectively. The extracted \({V}_{{PH}}\) values, plotted against corresponding \({V}_{{LED}}\) values, exhibit a monotonic trend, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 8d–f. We also found that our stacked In2Se3/MoS2 photodetectors can detect light pulses down to 100 µs as shown in Supplementary Fig. 9.

We also investigated the photoresponse from M3D In2Se3/MoS2 stack at various input optical frequencies (\({f}_{{LED}}\)), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 10a. The extracted \({V}_{{PH}}\) values, plotted against \({f}_{{LED}}\) in Supplementary Fig. 10b, remains constant up to 100 Hz, before steadily declining at higher frequencies, limited by the response times, \({\tau }_{R}\) and \({\tau }_{F}\). In the following sections, we will turn this speed limitation into an advantage by using it as “fading memory” to construct an optoelectronic physical reservoir for predicting time-series data. Furthermore, we will leverage the response variation across the stacked In2Se3/MoS2 devices, measured under identical \({V}_{{BG}}\) biases, to map unidimensional light intensity information into a higher-dimensional space for reservoir computing (RC).

3D optoelectronic reservoir for time-series analysis

RC derived from the framework of recurrent neural networks (RNNs), has become a powerful computational paradigm for processing time-series data and performing pattern recognition33,34,35. It has been notably applied in key areas such as financial forecasting and weather prediction36,37. As shown in Fig. 3a, RC leverages a fixed, randomly connected network of nonlinear units, known as the reservoir, to map lower-dimensional input data into a higher-dimensional space, represented as state variables, \({X}_{N}\left(t\right)\). These states are linearly combined with weights (\(W\)) to produce the predicted output, \(Y\left(t+1\right)=\mathop{\sum }_{i=1}^{N}{W}_{i}{X}_{i}\left(t\right)\). The key advantage of RC is that neither the input weights nor the weights of the recurrent connections within the reservoir are trained. Only the readout weights (W), which map the reservoir states to the output, are trained with a simple learning algorithm such as linear regression. This substantially simplifies the hardware realization of RC, requiring only a physical reservoir and a relatively simple readout circuit.

a A schematic highlighting the concept of reservoir computing (RC). It leverages a fixed, randomly connected network of nonlinear units, known as the reservoir, to map lower-dimensional input data into a higher-dimensional space. These states are linearly combined to produce the predicted output. b Optical image and (c) corresponding circuit diagram showing the hardware realization of an optoelectronic reservoir and readout circuit based on M3D integration of In2Se3 photodetectors and MoS2 memtransistors.

In this study, we leverage the device-to-device variation in the photoresponse of In2Se3 photodetectors stacked with corresponding MoS2 memtransistors to construct a physical reservoir. The optical image and circuit diagram of our 3D optoelectronic reservoir alongside the readout circuit are shown in Fig. 3b, c, respectively. This 3D optoelectronic reservoir maps unidimensional input stimuli, such as light intensity, into a higher-dimensional space, i.e., photovoltages, \({V}_{{Out},N}\). Here, N denotes the number of readout nodes. Note that RC necessitates a dynamic or fading memory to ensure that the reservoir gradually forgets previous inputs as new ones are introduced, allowing it to rely on both current and past inputs. The finite fall time associated with the photoresponse of the In2Se3 photodetectors, as discussed earlier, enables the realization of this fading memory, which is crucial for RC. Lastly, the readout circuit is implemented using another set of MoS2 memtransistors connected to the reservoir, whose weights are obtained from training and are implemented through non-volatile programming of the corresponding conductance states.

While our system differs from conventional reservoir computers that employ a fixed network of randomly connected nodes to generate recurrent high-dimensional dynamics, it nevertheless leverages intrinsic material variability to provide stochastic weight distributions and nonlinear transformations. We acknowledge that our present demonstration represents a deterministically designed network at a relatively small scale. However, such architectures can still capture useful transient responses and perform complex temporal tasks, aligning with the functional goals of RC. Importantly, the feasibility of synthesizing wafer-scale In₂Se₃ films provides a practical route toward constructing larger and more complex device networks, where the intrinsic variability of the material can naturally enrich the system dynamics and enhance scalability in line with the RC paradigm.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the 3D optoelectronic reservoir, we use daily stock index data as the input time-series, mapping it to \({V}_{{LED}}\) as shown in Fig. 4a. Specifically, we utilize New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) stock prices over 500 days, converting market fluctuations and trends into respective \({V}_{{LED}}\) pulses over a duration of 5 s. Each day is represented by a 10 ms \({V}_{{LED}}\) pulse, shorter than the fall time, allowing the reservoir to exploit the fading photoresponse memory. Figure 4b presents the \({V}_{{Out}}\) readouts from six pairs of In2Se3/MoS2 devices that construct the optoelectronic reservoir. We used the first 400 readout voltages to train a simple regression model to determine the weights and bias. After determining the readout function, the remaining 100 stock prices were used for testing. The time-series prediction task showed excellent performance for both training and testing, with an R2 score of 0.88 for NYSE as shown in Fig. 4c. Similar experiments conducted on other stock prices yielded R2 scores of 0.83 for NASDAQ, 0.93 for DJI, and 0.86 for SPI. These results, summarized in Fig. 4d, demonstrate the robustness and effectiveness of the RC system in handling complex, high-dimensional time-series data for financial forecasting with minimal hardware and training requirements.

a New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) stock prices over 500 days mapped into respective \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{LED}}}}\) pulses over a duration of 5 s. Each day is represented by a 10 ms \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{LED}}}}\) pulse, shorter than the fall time, allowing the reservoir to exploit the fading photoresponse memory. b \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{PH}}}}\) readouts from six pairs of In2Se3/MoS2 devices that construct the optoelectronic reservoir. c Actual and predicted stock prices for NYSE after training a simple regression model to determine the weights and bias. d Regression scores (R2) obtained for NYSE, NASDAQ, DJI, and SPI. e Dependence of R2 score on the number of nodes (N), i.e., the pairs of In2Se3/MoS2 devices. f Colormap showing the R2 values for different N for predicting stock prices i days in advance using our 3D optoelectronic reservoir.

We further investigate the dependence of R2 score on the number of nodes (N) of the reservoir, which is equivalent to the number of stacked In2Se3/MoS2 devices. As shown in Fig. 4e, the prediction accuracy increases with increasing N, but the improvement is relatively small for N > 4. The smaller number of devices required for a rather complex task of time-series data prediction makes RC appealing from a hardware implementation perspective for edge devices. We also found that our stacked In2Se3/MoS2 device-based optoelectronic reservoir can be employed to perform an increasingly intensive job of predicting stock prices several days in advance. In other words, the current state of the reservoir, \({X}_{N}\left(t\right)\), is used to predict the state i time steps ahead, \({X}_{N}\left(t+i\right)\), where i > 1. Figure 4f shows the colormap for R2 values for different combinations of i and N. As i increases, it becomes increasingly challenging for the system to forecast, thus resulting in a monotonic decrease in the R2 values. To avoid compromising the prediction accuracy in a longer time step, N can be increased.

Note that while silicon (Si) technology has been used for hardware realization of RC38,39, its lack of inherent variability and fading memory makes it less suitable for RC applications.

In contrast, novel materials such as memristors offer inherent non-linearity and memory characteristics that are more conducive to RC40,41,42. Additionally, photonic and spintronic reservoirs have been demonstrated to offer speed advantages over traditional silicon-based electronics43,44,45. However, most prior demonstrations using emerging materials or novel physical phenomena still required off-chip readout circuits based on Si technology. Our key contribution is the demonstration of a fully integrated system, where both the reservoir and the readout circuit are on the same chip. Furthermore, our approach leverages the benefits of near-sensor information processing and in-memory compute capability within a 3D stacked architecture.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have successfully demonstrated M3D integration of In2Se3 photodetectors with MoS2 memtransistors, enabling dynamic on-chip calibration and robust management of device variations by leveraging the programmability and non-volatile nature of memtransistors. Furthermore, we constructed a 3D optoelectronic reservoir computing system that achieves high accuracy in time-series predictions. Our demonstration showcases the significant advantages and vast opportunities presented by the heterogeneous 3D integration of functionally diverse materials.

Methods

Large-area monolayer MoS2 film growth

Monolayer MoS2 was deposited on epi-ready 2” c-sapphire substrate by metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD). An inductively heated graphite susceptor equipped with wafer rotation in a cold-wall horizontal reactor was used to achieve uniform monolayer deposition. Molybdenum hexacarbonyl (Mo(CO)6) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) were used as precursors. Mo(CO)6 maintained at 25 °C and 625 Torr in a stainless-steel bubbler was used to deliver 4.7 × 10−3 sccm of the metal precursor for the growth, while 400 sccm of H2S was used for the process. MoS2 deposition was carried out at 1000 °C and 50 Torr in H2 ambient, with monolayer growth achieved in 11 min. Before growth, the substrate was baked at 1000 °C in H2 for 10 min. Following growth, the substrate was cooled in H2S to 300 °C to inhibit the decomposition of the MoS2 film. More details on the growth process can be found in an earlier work46.

MoS2 film transfer to the local back-gate island

The transfer of the MoS₂ film was carried out using a polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)-assisted wet transfer technique47. Initially, the as-grown MoS₂ on a sapphire substrate was spin-coated twice with PMMA at 4000 rpm for 45 seconds and then left to rest overnight. To enable detachment, the film edges were gently scored with a razor blade before immersing the substrate in deionized (DI) water maintained at 90 °C for 1 h. Capillary action allowed the water to penetrate the interface between the hydrophilic sapphire substrate and the hydrophobic MoS₂/PMMA stack, thereby facilitating separation of the MoS₂ film from the substrate. Subsequently, the substrate was baked at 50 °C and 70 °C for 10 min each to remove moisture and promote film adhesion, thus ensuring a pristine interface. Finally, the PMMA was removed by immersing the sample in acetone for 1 hour, followed by a 30 minute isopropanol (IPA) bath and the substrate was cleaned with a subsequent 30 min IPA bath.

TEM sample preparation

The TEM sample shown in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1 were prepared using a Thermo Fisher Scientific (TFS) Scios 2 DualBeam FIB-SEM. To protect the surface from Ga ion beam damage during milling, a two-layer carbon coating was applied: an initial ~0.5 µm layer deposited via a 1.6 nA electron beam, followed by a ~3 µm layer deposited using a 0.3 nA Ga ion beam. An 1.5 µm-thick cross-sectional lamella from the target region was then extracted and transferred in situ to a copper half-grid. Final thinning was performed using a Ga ion beam with stepwise voltage reduction (30, 16, 8, 5, and 2 kV) to minimize beam-induced damage.

STEM characterization of the cross-section

Cross-sectional STEM and EDS imaging (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1) were conducted on an aberration-corrected TFS Titan G2 60-300 TEM/STEM operated at 300 kV. Key imaging parameters included a 70 µm C2 aperture, spot size 6, 115 mm camera length, and a 25.2 mrad convergence angle. The HAADF detector collected high-angle scattered electron signals in the 42–244 mrad range. EDS mapping was performed in STEM mode using the Super-X system. The HAADF-STEM images were acquired with a 0.07 nA beam current, while EDS was collected at 0.12 nA. EDS data were processed in Esprit using 1/4 Q-Map pre-processing, the series fit deconvolution method, and P/B ZAF quantification (mass percent, normalized), with 9-pixel averaging for post-filtering. To enhance the contrast of details in the EDS map, gamma and brightness were adjusted in Esprit software. Therefore the elemental maps are qualitative, although spatial distributions are accurately represented. The color intensities are not standardized and should not be compared quantitatively between elements.

Electrical characterization

Electrical characterization of the fabricated devices was performed under atmospheric conditions using a semi-automated Formfactor 12000 probe station with a Keysight B1500A parameter analyzer.

Setup for reservoir computing system

The training of the reservoir computing (RC) system was performed offline. Specifically, each In2Se3/MoS2 device pair was first characterized to extract its photovoltage response to input optical stimuli. These photovoltage outputs—serving as the reservoir states—were recorded for a known time-series input (e.g., NYSE stock data), and the first 400 samples were used to train the readout layer. The training involved applying simple linear regression to determine the optimal weights and bias that map the reservoir states to the target outputs. Once the weights were computed, they were programmed into the MoS2 memtransistor-based readout circuit using analog, non-volatile conductance tuning. The remaining 100 samples were then used to test the trained system’s prediction performance.

Data availability

Data on samples produced in the 2DCC-MIP facility, including growth recipes and characterization data, are available at https://doi.org/10.26207/f99k-vb47. Other data generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the source data files. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The codes used for plotting the data are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Jayachandran, D. et al. Three-dimensional integration of two-dimensional field-effect transistors. Nature 625, 276–281 (2024).

Shulaker, M. M. et al. Three-dimensional integration of nanotechnologies for computing and data storage on a single chip. Nature x547, 74–78 (2017).

Dhananjay, K., Shukla, P., Pavlidis, V. F., Coskun, A. & Salman, E. Monolithic 3D Integrated circuits: Recent trends and future prospects. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II: Express Briefs 68, 837–843 (2021).

Vinet, M. et al. Monolithic 3D integration: A powerful alternative to classical 2D scaling. SOI-3D-Subthreshold Microelectronics Technology Unified Conference (S3S). 1–3IEEE: 2014, 2014.

Sheikh, F., Nagisetty, R., Karnik, T. & Kehlet, D. 2.5 D and 3D heterogeneous integration: emerging applications. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Mag. 13, 77–87 (2021).

Sadaf, M. U. K. et al. Enabling static random-access memory cell scaling with monolithic 3D integration of 2D field-effect transistors. Nat. Commun. 16, 4879 (2025).

Koester, S. J. et al. Wafer-level 3D integration technology. IBM J. Res. Dev. 52, 583–597 (2008).

Batude, P. et al. Advances, challenges and opportunities in 3D CMOS sequential integration. in 2011 International Electron Devices Meeting, 2011: IEEE, 7.3. 1-7.3. 4.

Kang, J.-H. et al. Monolithic 3D integration of 2D materials-based electronics towards ultimate edge computing solutions. Nat. Mater. 22, 1470–1477 (2023).

Shulaker, M. M. et al. Three-dimensional integration of nanotechnologies for computing and data storage on a single chip. Nature 547, 74–78 (2017).

Srimani, T., Hills, G., Lau, C. & Shulaker, M. Monolithic Three-Dimensional Imaging System: Carbon Nanotube Computing Circuitry Integrated Directly Over Silicon Imager. in 2019 Symposium on VLSI Technology, 9–14 June 2019 T24-T25, (2019).

Zhu, K. et al. Hybrid 2D–CMOS microchips for memristive applications. Nature 618, 57–62 (2023).

Tong, L. et al. Heterogeneous complementary field-effect transistors based on silicon and molybdenum disulfide. Nat. Electron 6, 37–44 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. All-in-one two-dimensional retinomorphic hardware device for motion detection and recognition. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 27–32 (2022).

Liu, C. et al. Two-dimensional materials for next-generation computing technologies. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 545–557 (2020).

Ghosh, S. et al. A complementary two-dimensional material-based one instruction set computer. Nature 642, 327–335 (2025).

Pendurthi, R. et al. Monolithic three-dimensional integration of complementary two-dimensional field-effect transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 970–977 (2024).

Ghosh, S. et al. Monolithic and heterogeneous three-dimensional integration of two-dimensional materials with highdensity vias. Nat. Electron 7, 892–903 (2024).

Ghosh, S. et al. An all 2D bio-inspired gustatory circuit for mimicking physiology and psychology of feeding behavior. Nat. Commun. 14, 6021 (2023).

Zheng, Y., Ghosh, S. & Das, S. A butterfly-inspired multisensory neuromorphic platform for integration of visual and chemical cues. Adv. Mater. 36, 2307380 (2024).

Schranghamer, T. F. et al. Ultrascaled Contacts to Monolayer MoS2 Field Effect Transistors. Nano Lett. 23, 3426–3434 (2023).

Pendurthi, R. et al. Heterogeneous Integration of Atomically Thin Semiconductors for Non-von Neumann CMOS. Small 18, 2202590 (2022).

Dodda, A. et al. Active pixel sensor matrix based on monolayer MoS2 phototransistor array. Nat. Mater. 21, 1379–1387 (2022).

Sebastian, A., Pendurthi, R., Choudhury, T. H., Redwing, J. M. & Das, S. Benchmarking monolayer MoS2 and WS2 field-effect transistors. Nat. Commun. 12, 693 (2021).

Jayachandran, D. et al. A low-power biomimetic collision detector based on an in-memory molybdenum disulfide photodetector. Nat. Electron 3, 646–655 (2020).

Tonndorf, P. et al. Photoluminescence emission and Raman response of monolayer MoS 2, MoSe 2, and WSe 2. Opt. Express 21, 4908–4916 (2013).

Lewandowska, R., Bacewicz, R., Filipowicz, J. & Paszkowicz, W. Raman scattering in α-In2Se3 crystals. Mater. Res. Bull. 36, 2577–2583 (2001).

Jacobs-Gedrim, R. B. et al. Extraordinary photoresponse in two-dimensional In2Se3 nanosheets. ACS Nano 8, 514–521 (2014).

Li, W. et al. Synchronous enhancement for responsivity and response speed in In2Se3 photodetector modulated by piezoresistive effect. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 47098–47105 (2019).

Subbulakshmi Radhakrishnan, S., Dodda, A. & Das, S. An All-in-One Bioinspired Neural Network. ACS Nano 16, 20100–20115 (2022).

Dodda, A., Trainor, N., Redwing, J. & Das, S. All-in-one, bio-inspired, and low-power crypto engines for near-sensor security based on two-dimensional memtransistors. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–12 (2022).

Das, S. et al. Transistors based on two-dimensional materials for future integrated circuits. Nat. Electron 4, 786–799 (2021).

Jaeger, H. & Haas, H. Harnessing nonlinearity: Predicting chaotic systems and saving energy in wireless communication. Science 304, 78–80 (2004).

Maass, W., Natschläger, T. & Markram, H. Real-time computing without stable states: A new framework for neural computation based on perturbations. Neural Comput. 14, 2531–2560 (2002).

Sen, D. et al. Multifunctional 2D FETs exploiting incipient ferroelectricity in freestanding SrTiO3 nanomembranes at sub-ambient temperatures. Nat. Commun. 15, 10739 (2024).

Tanaka, G. et al. Recent advances in physical reservoir computing: A review. Neural Netw. 115, 100–123 (2019).

Nadiga, B. T. Reservoir computing as a tool for climate predictability studies. J. Adv. Modeling Earth Syst. 13, e2020MS002290 (2021).

Elbedwehy, A. N., El-Mohandes, A. M., Elnakib, A. & Abou-Elsoud, M. E. FPGA-based reservoir computing system for ECG denoising. Microprocessors Microsyst. 91, 104549 (2022).

Antonik, P., Smerieri, A., Duport, F., Haelterman, M. & Massar, S. FPGA implementation of reservoir computing with online learning. in 24th Belgian-Dutch Conference on Machine Learning, (2015).

Du, C. et al. Reservoir computing using dynamic memristors for temporal information processing. Nat. Commun. 8, 2204 (2017).

Moon, J. et al. Temporal data classification and forecasting using a memristor-based reservoir computing system. Nat. Electron 2, 480–487 (2019).

Zhong, Y. et al. Dynamic memristor-based reservoir computing for high-efficiency temporal signal processing. Nat. Commun. 12, 408 (2021).

Vandoorne, K. et al. Experimental demonstration of reservoir computing on a silicon photonics chip. Nat. Commun. 5, 3541 (2014).

Larger, L. et al. High-speed photonic reservoir computing using a time-delay-based architecture: Million words per second classification. Phys. Rev. X 7, 011015 (2017).

Akashi, N. et al. A Coupled Spintronics Neuromorphic Approach for High-Performance Reservoir Computing. Adv. Intell. Syst. 4, 2200123 (2022).

Choudhury, T. H. et al. Comparison of the MOCVD growth and properties of wafer-scale transition metal dichalcogenide epitaxial monolayers. 2D Materials 2, 045009 (2025).

Sebastian, A. et al. Electrochemical Polishing of Two-Dimensional Materials. ACS Nano 13, 78–86 (2018).

Acknowledgements

Monolayer MoS₂ samples grown by MOCVD were obtained from the 2D Crystal Consortium–Materials Innovation Platform (2DCC-MIP) at The Pennsylvania State University, supported by the NSF under Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-2039351. We would also like to acknowledge funding support from NSF for NSF Career under grant number ECCS-2042154, NSF Fuse, under grant number ECCS-2328741, ONR under grant number N00014-24-1-2565, and ARO under grant number W911NF-23-1-0279 (all four funded to S.D.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. A.C. fabricated all the samples. C.C. and J.M.R. grew and characterized the MoS2 film. Y.S. and Y.Y. obtained and analysed the high-resolution cross-sectional TEM data. A.C., A.R., H.R., and S.D. performed all the electrical measurements. D.K.M. and S.D. performed the stock price prediction calculations. All authors contributed to the preparation of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Min-Kyu Song, Peng Zhou, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chowdhury, A., Rasyotra, A., Ravichandran, H. et al. 3D Integration of functionally diverse 2D materials for optoelectronic reservoir computing. Nat Commun 16, 10252 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65109-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65109-z