Abstract

In nature, nanocrystals form primarily through geological processes, such as chemical weathering of rocks and minerals. However, artificial systems that mechanistically parallel geological nanocrystal formation, particularly in the solid state, replicating the hydrolytic conditions of geological processes remain rare. Here, we report an all-solid-state strategy for the synthesis of quantum-sized semiconductor nanostructured materials under ambient conditions. The approach relies on a hydrolysable organozinc precursor, consisting of [RZn(amidate)]n-type molecular clusters featuring reactive Zn-C and Zn-N bonds, confined within a single-crystal lattice prone to water-mediated hydrolytic processes. The initial millimetre-sized precursor crystals, when exposed to humid air, undergo hydrolytic transformations. Within hours these transformations lead to the formation of ZnO quantum dots at room temperature, reminiscent of natural chemical weathering. The crystalline network of the precursor system provides a specific environment for the formation of zinc hydroxide/oxide species, followed by nucleation and growth of quantum dots within an emerging hydrogen-bonded host organic matrix composed from the hydrolysable amidate ligands. This organic matrix, in turn, can be removed from the system under reduced pressure, yielding a nanocrystalline mesoporous scaffold consisting of quantum-sized crystals. This organometallic synthetic system provides insights into solid-state nanostructured materials formation under mild conditions and offers a pathway to sustainable synthesis of functional materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Development of solid-state reactions is a major challenge and one of the key targets for sustainable synthetic strategies1,2,3. However, to date, only a few artificial solid-state synthetic strategies that lead to predesigned products under ambient conditions, without the addition of external energy, have been described4,5,6. Moreover, there is a scarcity of examples where molecular precursors, typically reactive in solutions, are employed for the solid-state synthesis of nanocrystalline materials. This is due to the relatively low reactivity and diffusion rates of chemical species in the crowded templating environment of the solid state, which substantially limits mass transport and nanoscale materials nucleation and growth7,8,9. To overcome these energy barriers and facilitate the movement of molecules or ions along with particle nuclei – thereby promoting the formation of desired nanomaterials – applying heat8,10,11 and/or mechanical treatment12,13,14 is necessary, as it enables allowing efficient reactant mixing. In contrast to these laboratory conditions, nanoscale materials formation in nature occurs at moderate temperatures, primarily through chemical weathering processes driven by water, oxygen, and carbon dioxide, which are the key factors in the breakdown of rocks and minerals (Fig. 1a)15,16,17,18. Although the timescale of these natural processes is impractical from laboratory setting, they offer valuable insights for designing artificial precursor systems for nanoscale materials, particularly regarding their reactivity towards hydrolytic and/or oxidative species19,20.

a, b Schematic representation of weathering processes occurring in nature (a) and nature-inspired weathering processes of molecular single-crystals described in this work (b). c Design principles of the HOPE system. d Molecular structure of [EtZn(BA)]4. e Crystal structure of [EtZn(BA)]4. f 1D chains of stacked barrel-shaped clusters derived from assembly of [EtZn(BA)]4 clusters. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Inspired by natural processes, we describe here a predesigned artificial all-solid-state molecular system for synthesising monodisperse semiconductor nanostructured materials under ambient conditions (Fig. 1a, b). Our synthetic approach relies on single-crystals (SCs) consisting of organometallic [RZn(X)]n-type molecular clusters (where X = monoanionic organic ligand), referred to as a Hydrolysable Organozinc PrEcursor (HOPE) throughout the text, featuring both the R-Zn and Zn-X units prone to water-mediated hydrolytic processes. By employing a variety of in situ spectroscopic and diffraction techniques, we demonstrate that exposure of a SC of nonporous in the initial state HOPE to humid air results in the stepwise formation of low-dispersity semiconductor ZnO nanoparticles with diameters of ca. 4.5 nm embedded within an emerging organic matrix composed of hydrolysed organic ligands X, closely resembling natural chemical weathering; herein after we call these quantum size ZnO particles as quantum dots (QDs). Since the nanocrystals reported herein have diameters near the exciton Bohr radius of ZnO and given that ZnO NCs typically exhibit domain-like substructures capable of confining local quantum effects21,22, we refer to our nanostructured materials as QDs. Furthermore, we reveal that the ongoing hydrolytic transformations generate a dynamic, hydrogen-bonded matrix based on hydrolysed ligands and water molecules, enabling efficient mass transport within the developing host matrix and providing highly controlled conditions for nanocrystals nucleation and growth.

Results

Design and synthesis of a model single-crystal HOPE system

The tightly packed nature of nonporous crystal lattices poses significant challenges for mass transport. Consequently, solid-state transformations of nonporous SCs without external stimuli (e.g., temperature or mechanical forces) into alternative molecular or nanocrystalline products are rarely explored23,24,25,26,27,28. Recently, we reported a structurally adaptable molecular system based on heteroleptic [RZn(X)]-type complexes in which pyrophoric dialkyl zinc (R2Zn) guest molecules can induce the formation of internal cavities loaded with the guest molecule, resulting in the formation of relatively robust towards air corresponding molecular crystals29. In this vein, a molecular SC system incorporating [RZn(X)]n-type clusters that is reactive towards water and oxygen (as air components), and enabling efficient growth of nanostructured materials within its crystalline network, would be conceptually different from currently known processes. As in this type of system the formation of a nanocrystalline phase is anticipated to take place through initial molecular cluster-to-cluster transformations and nucleation and growth processes (which are all driven by a complex interplay of bulk, surface, and interface thermodynamics), a subtle balance between the structure and reactivity of a predesigned precursor must be considered30,31. Mimicking natural systems, we envisioned that a molecular solid-state precursor system prone to chemical weathering towards nanostructured materials should ensure (i) moderate reactivity towards air and (ii) a synthetic environment that provides efficient mass transport, along with effective nucleation and growth of emerging nanoparticles (Fig. 1b). Based on our extensive experience in both design of various organometallic precursors and their controlled hydrolysis10,29,32,33 alongside their controlled transformations to metal-organic frameworks34 and quantum-sized crystals35,36, we selected an ethylzinc benzamide derivative, i.e., a tetranuclear [EtZn(BA)]4 cluster, as a model system for the solid-state transformations [where BA = monodeprotonated benzamide ligand; benzamide (BA-H) exhibits relatively moderate acidic character37 (pKa ca. 14) and can act as a weak N-base and accept proton when deprotonated]. This type of clusters bear “encoded” functional features in its molecular structure, as both reactive Zn-C bonds and Zn-N bonds can readily interact with acidic protons10, as shown in Fig. 1b. The incorporation of these functionalities is critical, as upon contact with traces of water such organometallic precursor can undergo efficient transformations to various zinc oxide species through stepwise release of benzamide and volatile ethane molecules, which both can contribute to enhanced mass transport in the solid-state. Additionally, the hydrolysable BA ligands may serve as a source of an inherent supramolecular organic matrix composed of the released BA-H molecules. In combination with water molecules, the emerging matrix can potentially provide (i) efficient mass transport of reactants and (ii) kinetic control over nucleation and growth of the nanostructured materials formed during the described processes.

The model SC precursor, incorporating the closely packed tetranuclear clusters [EtZn(BA)]4, is prepared by an equimolar reaction between commercially available diethyl zinc (Et2Zn) and benzamide (BA-H), followed by quantitative crystallisation from the post-reaction mixture at the multigram scale to yield single crystals (see Methods for details). The molecular and crystal structure of [EtZn(BA)]4 was confirmed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD) and is shown in Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1 (see Supplementary Data 1 and 2). The [EtZn(BA)] moieties crystallise in the space group P-1 as a tetramer with a slightly distorted Zn4O4 heterocubane structure. Each BA ligand adopts μ3-(η2-Ο):(η1-Ν)-coordination mode, bridging three four-coordinate Et-Zn centres and resulting in a barrel-shaped molecular structure based on fused six-membered rings (for selected geometrical parameters, Supplementary Tab. 1). The non-specific, noncovalent interactions-driven self-assembly of the tetranuclear clusters leads to a close-packed nonporous crystal lattice with no solvent molecules entrapped (Fig. 1d). The crystal lattice is propagated along the a-axis, forming 1D chains of stacked barrel-shaped clusters (Fig. 1e). Although the calculated volume of the channel formed by stacked cluster (ca. 1 Å) is too small for inclusion of small molecules (e.g., water), the surface arrangement of hydrophilic O- and N-centres of the BA ligands, located in discrete next-like microcavities within the barrel-shaped clusters (Fig. 1e), creates a suitable environment for adsorption of water molecules. This affinity for water molecules may promote efficient hydrolysis of the Zn-C and Zn-N bonds (Supplementary Fig. 2) and proof-of-concept studies are demonstrated below using various in situ spectroscopic techniques.

Spectroscopic insights into the HOPE chemical weathering

Chemical reactions in nonporous solids are usually hindered by relatively low diffusion rates of reactants at low temperatures, rendering these chemical transformations kinetically inacessible7,8,9. We conceptualised that introducing a SC lattice prone to chemical weathering could overcome this limitation, as structural rearrangements within the system induced by emerging chemical reactions could unlock efficient mass transport. To test our hypothesis, we exposed single crystals of the [EtZn(BA)]4 system to air at room temperature and monitored the progressing weathering processes using a range of time-resolved in situ as well as ex situ spectroscopic techniques, including diffuse reflectance infra-red Fourier transform (DRIFT) and Raman (RS) spectroscopy, further supported by cross-polarisation magic angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (CP-MAS NMR).

In the HOPE system based on heteroleptic [EtZn(BA)]4 clusters, water serves as a primary source of oxygen for the formation of ZnO QDs, as the four-coordinate Zn-Et moieties present in the [EtZn(BA)]4 molecular structure are deemed to be essentially unreactive towards dioxygen38 (Supplementary Fig. 8; see Supplementary Note 3). An overview of the water-driven transformations within the HOPE SCs to intermediate clusters is summarised in Fig. 2a. In the first step, water molecules adhere to the discrete hydrophilic microcavities of clusters on the HOPE surfaces (Supplementary Fig. 2) and initiate complex hydrolysis events involving both the Zn-BA and Zn-Et units, respectively. Although the detailed mechanisms of the hydrolysis reactions of [RZn(X)]n-type clusters remain underexplored, based on our experience with the controlled hydrolysis of organozinc compounds32,33,39,40,41, it is reasonable to anticipate that [EtZn(BA)]4 clusters embedded the SC lattice are initially hydrolysed into various hydroxide- and oxide multinuclear transient clusters tentatively formulated as [ZnO]x[EtZn(BA)]y, ZnOx(OH)y(BA)z(Et)n, or ZnOx(BA)y39,41. The formation of these new chemical entities triggers local changes and distortions within the SC lattice, facilitating the penetration of additional water molecules into the crystal interior and promoting further hydrolysis of the parent [EtZn(BA)]4 clusters. While transformations of well-defined organozinc complexes leading to partially hydrolysed clusters with sequestered “ZnO” units are known in solutions39,41, experimental insights into this chemistry in the solid state are scarce42.

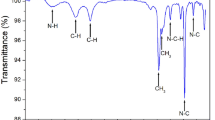

a Schematic representation of the HOPE system transformation mechanism to ZnO QDs involving: (i) initial hydrolysis of [EtZn(BA)]4 cluster, (ii), formation of zinc hydroxide- and oxide intermediates, (iii), nucleation and growth of ZnO@BA QDs. b, c Time-resolved DRIFT (b) and the evolution of selected signals in time (c). d Time-resolved Raman studies on the transformation of HOPE towards ZnO QDs. e 13C CP-MAS and 15N CP-MAS NMR studies on the transformation of HOPE towards ZnO QDs. Asterisks (*) indicate emerging signals from amide group of free crystalline BA-H. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Indeed, time-resolved DRIFTS experiments on a HOPE micronized sample exposed to air reveal that the successive hydrolysis steps start from relatively rapid protonolysis of BA ligands of the pristine [EtZn(BA)]4 clusters (Fig. 2b, c). The bands at 3370 and 3185 cm−1, corresponding to the asymmetric and symmetric stretches of the NH2 group in the released BA-H molecules, appear within the first seconds of air exposure (Fig. 2b, c). The rapid development of these bands, along with broad bands in the 3000-3400 cm−1 range, indicates the progressing hydrolysis mediated by penetrating water molecules and concurrent formation of intermediate zinc hydroxide- and oxide species. After the first 30 min, the process slows down, however the subsequent hydrolysis of the Zn-C bonds becomes evident (as seen in the decrease of C-H stretching bands of the Zn-Et units at 2850 cm−1; also observed in the Raman spectrum at 2880 cm−1). The DRIFT data were further corroborated by the Raman spectra, showing the emergence of a band at 3630 cm−1 (Fig. 2d) characteristic for the O-H stretching modes and indicating zinc hydroxide intermediates in the reaction medium43. After ≈4 h two new bands are observed at 583 and 1156 cm−1, assigned to the ZnO-stretching vibrations, indicative for the formation of QDs. Both the DRIFT and Raman spectra indicate that the hydrolysis of Zn-Et groups, leading to the release of volatile ethane, lags behind the BA ligands protonolysis.

The CP-MAS NMR spectra shown in Fig. 2e further support the described transformation pathways and provide insight into changes in sample crystallinity during the hydrolysis process. The solid-state NMR data indicate that both the BA ligands (signals at 175 ppm for the carbonyl group and complex signals at 130 ppm for the phenyl group) as well as the alkyl groups (signals at 13 and −2 ppm) are protonated over time. A gradual broadening and shift of the resonances corresponding to the Zn-bound BA ligands is observed within the first 24 h. The broad resonances centred at ≈172 and ≈125 ppm are clearly visible in the spectrum after 24 h and are assigned to a mixture consisting of chemical species incorporating both deprotonated and protonated benzamide ligands. This broadening of the signals is likely due to the emerging inhomogeneity of the chemical environment and appearance of local amorphization domains within the sample. We note that a small fraction of crystalline BA-H matrix (sharp resonance at 172 ppm) is observed after 5 h of the weathering process, and the signals from these species gradually increase over time. With extended exposure, the crystalline BA-H matrix becomes the dominant fraction after 96 h. Importantly, signals from the ethyl group decrease in intensity over time, and disappear after ca. 96 h, which is attributed to the evolution of ethane as confirmed by thermogravimetric analysis (Supplementary Fig. 10) as well as DRIFT and RS. The initial amorphization and subsequent crystallisation of BA-H fraction are further observed in the CP-MAS 15N NMR experiment, where the signal of deprotonated BA at –222 ppm shifts to a broad resonance around –250 ppm (amorphous phase), which subsequently transforms into a well-shaped peak at –273 ppm, characteristic of crystalline BA-H.

We utilise isothermal thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) to analyse the mass changes of the sample during the weathering process and to highlight which groups leave the system, in collaboration with spectroscopic insights (Supplementary Fig. 10). The isothermally registered weight change for the HOPE sample as a function of time exhibits an asymmetric parabolic character. The weight loss is observed primarily within the initial 10 h of the weathering process, consistent with the evolution of gaseous ethane (Et-H) resulting from the hydrolysis of Zn-Et units. The recorded weight loss of 3.15% is lower than the calculated mass drop of 5.57% estimated for the total hydrolysis of Zn-C bonds, accompanied by the formation of ZnO/ZnOH sequestered units supported by BA ligands (vide supra spectroscopic insights into the HOPE chemical weathering); note that the hydrolysed BA-H molecules do not leave the system but form the host organic matrix. This discrepancy suggests that, parallel to the hydrolytic processes, moisture permeation occurs, and additional water molecules (formally ca. 1.3 H2O molecules per one Zn centre) are absorbed by the sample at this stage. In the subsequent period from 10 to 96 h, the combination of water adsorption, progressing hydrolytic reactions, and QD nucleation and growth processes, is evidenced by the observed slightly non-monotonic weight gain of the sample. We note that a differential scanning calorimetry experiment for the weathering process aiming to demonstrate heat flow produced by the sample when held isothermally at ambient temperature was featureless (see Supplementary Note 5, Supplementary Fig. 10).

Altogether, the described spectroscopic data provide comprehensive insights into the initial steps of hydrolytic processes within the HOPE system, where the hydrolysis of Zn-N and Zn-C bonds is critical. These hydrolysis processes progressively introduce disorder throughout the HOPE crystal structure, which, together with the release of ethane molecules, creates a water-permeable dynamic matrix essential for efficient mass transport of both water molecules and emerging zinc hydroxide and oxide intermediates. Subsequently, these intermediates act as secondary precursors for nucleation and growth of ZnO QDs. The revealed acid–base relationship between the Zn-BA and Zn-Et units is likely a key to the successive formations of zinc hydroxide/oxide species followed by nucleation and growth of QDs within an emerging hydrogen-bonded host organic matrix composed from the hydrolysable amidate ligands.

Insights into formation of quantum dots

The weathering processes were further tracked by monitoring the formation of both the BA-H-based matrix and quantum-sized ZnO crystals using in situ powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), UV-Vis spectroscopy, and optical microscopy. A schematic overview of weathering processes leading to the formation of ZnO QDs is summarised in Fig. 3a. Analysis of the PXRD patterns revealed complex transformations of the SC precursor, leading to nanocrystalline products through an amorphous intermediate phase (Supplementary Fig. 7). Reflexes characteristic of [EtZn(BA)]4 clusters (inset Fig. 3b) decrease rapidly in intensity, vanishing almost completely within the first 30 min. This loss in precursor crystallinity is likely associated with the progressive adsorption of water vapour and the relatively rapid hydrolysis of the parent [EtZn(BA)]4 clusters, resulting in the formation of a mobile phase based on hydrolysed BA-H molecules and various molecular hydroxide- and oxide clusters distributed throughout the HOPE SC body. Subsequently, the released BA-H molecules form both a new crystalline phase, identified as the classical polymorph of benzamide44 (indicative peaks at 5° − 30° 2θ, inset Fig. 3b), and a hydrogen-bonded host supramolecular network based on BA-H and entrapped water molecules. This BA-H based mobile supramolecular phase helps maintain crystal shape integrity while enabling efficient mass transport of reactants essential for nucleation and growth of ZnO QDs capped by monoanionic BA ligands, herein after referred to as ZnO@BA QDs. Following these initial weathering steps, new diffraction peaks from emerging QDs appear within 3 h, indicating simultaneous nucleation and growth processes. By the 72-h mark, distinct peaks corresponding to the benzamide crystalline phase become visible, along with progressively sharper and more defined nanocrystal reflexes. Ultimately, after 96 h, the final size of the inorganic QDs core was determined to be 4.7 nm. HRTEM examination closely aligns with the PXRD data, revealing an average QD diameter of 4.6 ± 0.6 nm, consistent with a nanocrystalline ZnO wurtzite phase (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 9). The observed narrow size distribution of QDs is a notable feature of the studied system corroborating previous reports on the liquid-phase transformations of various RZn(X)-type precursors to colloidal QDs where the incorporated monoanionic X organic ligands not only modulate the reactivity of alkylzinc species but also stabilise the surface of the growing QDs and determine their size and morphology35,45,46,47,48.

a Schematic representation of weathering processes leading to the formation of ZnO QDs. b The evolution of the time-resolved PXRD pattern during the HOPE SC transformation. c The HRTEM images of the final ZnO QD with the average size of 4.6 ± 0.6 nm. d The evolution of calculated QD diameter versus reaction time from in situ UV-Vis. e UV-Vis and PL spectra of ZnO QDs obtained by air exposure of HOPE SCs for 96 h. f Optical microscopy images of the HOPE SC upon exposure to air. g Single crystals of the HOPE after transformation photoexcited with 365 nm wavelength. h Optical microscopy images of the HOPE SC after weathering processes visualised with aligned polarizers. Needle-like crystals of BA-H at the HOPE surface are indicated by arrows. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The nucleation and growth stages of ZnO@BA QDs were further monitored using in situ UV−Vis spectroscopy49,50. The evolution of calculated QD diameter versus reaction time is shown in Fig. 3d. The data reveal two distinct quantum-sized crystal growth stages: a rapid initial growth of QDs during the first 24 h, followed by a slower growth in the later stages. The initial stage exhibits an exponential growth profile, saturating after ≈ 24 h, corresponding to QDs reaching a diameter of around 4 nm. Following this, the growth rate decreases by a factor of 10, transitioning into a quasi-linear process. Over the course of the weathering process, the QDs reach a diameter 4.40 nm after 96 h. To accurately describe the observed QD growth kinetics, we employed a combined growth model that integrates both the non-classical oriented attachment (OA) and the classical Ostwald ripening (OR) mechanisms. This model reflects a sequential process: an initial rapid growth phase governed predominantly by OA, followed by a slower, diffusion-controlled OR phase51,52, which is consistent with the experimental data and captures the complete trajectory of nanocrystal growth across both regimes. The initial exponential growth profile can be well described by equations associated with OA, suggesting that this stage of QD growth is likely dominated by OA processes, where sequential stages consist of nucleation and growth of QDs by clustering and molecular diffusion of zinc hydroxide- and oxide clusters to form larger particles without dissolving the primary particles51,53,54. While the data supports the OA-based QD growth, other, more complex scenarios cannot be entirely ruled out, in which the nucleation and growth of emerging QDs occur at the expense of molecular zinc hydroxide- and oxide clusters. The subsequent growth stage (after 24 h), characterised by a distinct and much slower QD growth rate, is well described by the classical OR process55. At this stage, the less stable, smaller crystalline domains, along with the remaining hydroxy- and oxo clusters that likely exhibit higher mobility in the organic matrix, decay in favour of the larger and more stable ZnO nanocrystalline phases. Since the organozinc precursor-derived QDs are inherently coated with organic ligands47 and embedded in the organic matrix, once their growth is completed, the neighbouring QDs do not coalesce, preserving their size and shape56.

To illustrate the above-described weathering events on a macroscopic scale, we conducted a series of experiments where HOPE SCs were exposed to air and monitored using optical microscopy and the selected images are shown on Fig. 3f, g, Supplementary Fig. 4, and Supplementary Movie 1. The captured images revealed that the HOPE SC maintained its initial shape and volume (with less than 1% change in size observed) throughout the entire process, suggesting that the BA-H based matrix not only maintains crystal shape integrity but likely also serves as a dynamic, metastable matrix for ZnO QDs’ prenucleation, nucleation and growth57. Crystallisation of the hydrolysed BA ligands, forming needle-like crystals at the HOPE surfaces, was also observed (Fig. 3h, Supplementary Fig. 5, and Supplementary Movie 1); in agreement with the PXRD data. Moreover, while the initial HOPE SCs were not photoluminescent, after several hours of exposure to air, the SC sample exhibited strong yellow luminescence (λmax = 530 nm; Fig. 3e, g) when irradiated with UV light (365 nm), characteristic of the ZnO surface electronic structure.

Self-assembly of quantum dots within the HOPE matrix

Time-resolved in situ SAXS experiments provide in-depth insights into the emerging QDs’ aggregation processes during the transformation of HOPE single-crystals. Figure 4a shows the evolution of SAXS signals throughout the initial stage of transformation (t < 2 h). The initial increase in SAXS signal intensity in the small-q region (q < 0.05 Å−1) is characteristic of transformations on the molecular level, and the QD nucleation and growth. Although the collected data did not allow for accurate particle-size determination, likely due to the surface-driven nature of these processes and the random orientation of QDs (vide infra), it nonetheless provided valuable insights into how the QDs aggregate and the overall structure of their aggregates. The SAXS patterns were fitted using a simplified sphere-approximation model that captures sample dispersity in size and shape, as well as the type and geometry of the emerging assemblies (Supplementary Figs. 11, 12; see Methods for details). An initial rise in dispersity (t < 12 h; Fig. 4b) followed by a decrease indicates a complex interplay between QD growth and aggregation processes. The exponents of the power-law in the Porod regime (high-q range (q > 0.05 Å−1)) were determined by fitting the scattering profiles in 0.05–0.2 Å−1 regime to the SAXS profiles, revealing variation in the power law value over time and establishing a clear threshold at the 12 h-time point (Fig. 4c) At the early stage (t < 12 h), a rapid growth of the exponent p for the Porod law is observed from 2.4 to 3.4 within the first 12 h, then the growth rate decelerates continually, being effectively arrested with a value of 3.6 until the end of the process. The linear growth rate of the fractal dimension exponent indicates diffusion-limited aggregation (DLA) processes (within the first 12 h), yielding increasing dispersity58. In contrast, the stable value of the exponent after the 12-h mark suggests that reaction-limited aggregation (RLA) is in place, which results in progressively decreasing dispersity (Fig. 4c).

a The evolution of the time-resolved SAXS pattern in a log-log scale during the initial stage of HOPE SC transformation. b Dispersity parameter determined by the fit of the SAXS patterns. c Power law parameter determined by the fit of the SAXS patterns. d N2 gas sorption isotherm for the mesoporous material based on ZnO QDs. e Schematic representation of the activation of the mesoporous material by vacuum-assisted sublimation of amidate organic matrix. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In DLA, particles move randomly through the surrounding medium, and growth occurs when a diffusing particle collides with an aggregate or cluster. Due to the lack of strict preferences for size or orientation in these collisions, this process promotes a broad distribution of aggregate sizes, leading to increased dispersity. In RLA, particles also approach clusters within the medium, but their movement and subsequent attachment are slower, as the aggregation is limited by the rate of chemical or surface reactions rather than by diffusion. Unlike in DLA, particles in RLA must overcome an energy barrier or react chemically to bind a cluster, introducing selectivity in the attachment process. This selective attachment results in more compact and ordered structures, which limits the variability in aggregate sizes and leads to a decrease in dispersity over time. As a result, in our system, the growth and assembly of QDs progress from the formation of primary ZnO QDs, followed by their rapid assembly to form quasi-fractal, open structures with higher dispersity of the aggregate structures. After this initial phase, the processes slow down, allowing the formation of close-packed, more ordered QD aggregates in the final material (lower dispersity of the aggregated structures, Fig. 4e).

Interestingly, the clear threshold within the first 24 h was also observed in in situ UV-Vis experiments, suggesting two distinct kinetic processes: (i) one associated with the OA-type mechanisms, accompanied by the complex growth of primary QDs through the absorption of molecular zinc hydroxide- and oxide clusters, followed by (ii) the classical OR crystal growth (vide supra). These two stages of QD growth correspond to the DLA and RLA processes, respectively, as observed in the SAXS experiments. Similar to DLA, the initial OA processes can lead to increased dispersity due to the fusion of primary particles or clusters with variable sizes and orientations59. The resultant broad size distribution later narrows as particles coalesce into more stable configurations. RLA processes, typically characterised by decreased dispersity of the resulting aggregates, occur in our system together with OR processes, also yielding lower dispersity. Collectively, the SAXS and UV-Vis data suggest that the initial phase of the HOPE transformation, with relatively high freedom for the diffusion of intermediate zinc hydroxide/oxide nanoclusters alongside primary ZnO QDs, allows for rapid and more random QD growth and aggregation. In contrast, the later stages are dominated by processes that yield lower dispersity in the size of the final material, both at the level of individual QDs and QD aggregates.

Vacuum-assisted formation of semiconductor aerogels

As discussed above, the role of the emerging organic matrix within the HOPE system was explored, revealing its auxiliary function in mass transport, which facilitates the formation of QDs. The presence of BA-H molecules within the resultant ZnO@BA/BA-H monolith draws our attention to whether the BA-H-based matrix can be post-synthetically removed, thereby providing porosity in the remaining scaffold based on ZnO@BA core-shell QDs (Fig. 4e). We hypothesised that the volatile BA-H molecules could be readily extracted and separated from the ZnO@BA core-shell QDs through a vacuum-triggered sublimation, potentially enabling the preparation of a microporous material based on semiconductor QDs without using any solvents, extended heating, or complex surface area activation procedures (see Supplementary Note 7). Subjecting the ZnO@BA/BA-H material to the reduced pressure (4·10−3 mbar at 120 °C) for 2 h led to sublimation of BA-H (Fig. 4e), yielding a white, fluffy material. The resultant material exhibits a low bulk density of 0.10 g cm−3, corresponding to only 1.4% of the density of a ZnO single crystal (5.61 g cm−³)60. The porosity of the material was further verified by N2 adsorption at 77 K. The material adsorbs N2 with a maximum uptake of 220 cm3 g−1 and exhibits a type-IV isotherm characteristic for mesoporous materials (Fig. 4d). The calculated Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area was determined to be 83 m2 g−1 and the average pore diameter is ≈9.2 nm. The data presented, in conjunction with additional TGA, PXRD, and FTIR analysis (Supplementary Figs. 13-15), show that the surface area of the ZnO@BA/BA-H material was activated, yielding a nanocrystalline mesoporous scaffold (aerogel) based on ZnO@BA building blocks61,62,63. In this light, the presented activation strategy, relaying on sublimation of organic matrix, appears particularly attractive, yielding mesoporous materials in a straightforward manner (see Supplementary Note 7 for a detailed discussion).

Discussion

Developing solid-state reactions as environmentally friendly and efficient chemical processes is a challenging task. These reactions often require high temperatures and face difficulties in controlling product formation and achieving desired nanoscale features. We have demonstrated an all-solid-state synthetic strategy for the preparation of nanoscale materials under ambient conditions. This synthetic approach relies on the predesigned organozinc precursor containing both reactive Zn-C and Zn-N bonds, confined within a non-porous single-crystal matrix prone to water-mediated hydrolytic processes. Upon contact with air (or water vapours), such predesigned precursor undergoes efficient hydrolytic transformations, leading to the straightforward formation (hours) of semiconductor QDs at ambient temperature. This artificial all-solid-state synthetic strategy explores SCs as chemical “reactors” driven by water-fuelled reaction cycles, mimicking naturally occurring chemical weathering.

The SC precursor is reactive towards selected atmospheric components and enables efficient growth of QDs within its own crystalline yet dynamic body, which is prone to rearrangements, thereby overcoming the limitation of efficient mass transport in the solid-state. The transformations from the model precursor to the final QDs proceeds through several complex developmental stages. The dynamic, hydrogen-bonded organic matrix serves as a critical factor, providing spatial control over the QDs’ formation, delineating boundaries for these processes and maintaining them within the framework of the initial SC body. During the transformation, this supramolecular host matrix acts as an intermediate “solvent”-like environment supporting the nucleation processes, similar to previously described observations for other solid-solid transitions64. Consequently, the resultant network of QDs preserves the size and shape of the original SCs.

From this point of view, the reported artificial system can also be viewed as a single-crystal chemical reactor (flask), where the crystal matrix plays a dual role, acting as a precursor of metal centres and as a “solvent”, providing the chemical environment for the reaction to proceed. The reported system unveils the formation of QDs and the assembly of their arrays within a crystalline network, revealing dynamic solid matrices as useful environments for nanosynthesis, and sets the basis to explore the desirable extremes in the intricate structure–activity relationships between molecular-level perturbations and sustainable nanosystem engineering.

Methods

Materials

All chemicals were obtained from commercial vendors, i.e., benzamide (Sigma-Aldrich, 99% purity) and diethylzinc (ABCR, 99.9998% Zn purity), and were used as received. Solvents were dried and distilled prior to use with an MBraun SPS solvent purification system. Air-sensitive manipulations were performed under a dry, oxygen-free nitrogen atmosphere by using a glovebox (water and oxygen concentration level below 0.1 ppm) and standard Schlenk techniques.

Synthesis of [EtZn(BA)]4

Et2Zn (10 mmol) was added to a suspension of benzamide (10 mmol) in DCM (15 ml) at −78 °C, and then the reaction mixture was allowed to warm to 20 °C and stirred for an additional 24 h. Colourless crystals were obtained after crystallisation with the addition of hexane at 20 °C; isolated yield ca. 87%.

The general protocol for solid-state transformation of [EtZn(BA)]4

An appropriate amount of [EtZn(BA)]4 single-crystals were exposed to humid air at room temperature (25 °C) and relative humidity (45%-55%). The resultant material was collected after 96 h.

Single crystal X-ray diffraction

The crystal was selected under Paratone-N oil, mounted on the nylon loops, and positioned in the cold stream of nitrogen on the diffractometer. The X-ray data for complex [EtZn(BA)]4 was collected at (100 ± 2) K on a SuperNova Agilent diffractometer using graphite monochromated CuKα radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å). The data were processed with CrysAlisPro65. The structure of [EtZn(BA)]4 was solved by direct methods using the SHELXT program and was refined by full-matrix least-squares on F2 using the program SHELXL66. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. Hydrogen atoms were added to the structure model at geometrically idealised coordinates and refined as riding atoms.

Powder X-ray diffraction

Diffractograms were collected on a PANalytical Empyrean diffractometer with Ni-filtered CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), a secondary graphite (002) monochromator, and an RTMS X’Celerator (Panalytical) in an angle range of 2θ = 5° to 80°, by step scanning with a step of 0.02°.

Small angle X-ray scattering

The small angle X-ray diffraction patterns were collected with the Bruker Nanostar system fitted with a CuKα1 radiation source (Incoatec); the patterns were registered with an area detector VANTEC 2000. Precursor powder was sealed inside a glovebox in a hermetic SAXS cell with Kapton windows and transferred to a diffractometer. The sample holder section of the instrument has not been evacuated, and one of the vacuum ports was left open to allow the exchange of air with the ambient air in the laboratory. After the collection of the first scattering pattern (t = 0), the Kapton windows were punctured to admit the ambient air (RH = 55%) into the cell. The temperature of the sample was stabilised at (25.0 ± 0.1) °C throughout the experiment. The signal intensities vs. wavevector q were obtained through the integration of the pattern over the azimuthal angle. The scattering data were analyzed using SASView (http://www.sasview.org/), assuming a spherical form factor and a lognormaparticle size distribution.

Solid-state cross-polarisation magic-angle spinning 1H NMR, 13C NMR nuclear magnetic resonance (CP-MAS 13C NMR, 15N NMR)

CP-MAS NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance II 500 MHz spectrometer. For 13C MAS NMR spectra were measured at a spinning frequency of 8 kHz and for 15N MAS NMR at a spinning frequency of 6 kHz. All CP-MAS NMR spectra were performed at 298 K and were referenced to glycine as an external standard.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectra were measured with a Renishaw inVia spectrometer.

FTIR spectroscopy

FTIR spectra were measured with a Bruker Tensor II spectrometer equipped with an ATR (attenuated total reflection) accessory.

DRIFT spectroscopy

DRIFT spectra were measured with a Bruker Tensor II spectrometer equipped with a diffuse reflectance accessory (Pike Technologies).

UV–Vis spectroscopy

UV–Vis spectra were acquired on a UV 2600 spectrometer (Shimadzu), and measurements were performed on solid powders located on the BaSO4 surface in reflectance mode with the integrating sphere as a detector in the range 186–1400 nm by 5 nm wide scanning with a step of 1 nm. ZnO NC sizes were obtained from UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectra by converting the measured data to absorbance–wavelength plots for selected time points, determining the optical band gap (Eg) from Tauc plot analysis, and calculating the corresponding sizes using the Brus equation.

PL spectroscopy

PL emission was measured using Quantaurus τ (Hamamatsu C11367).

TGA

Thermogravimetric analysis measurements were performed using open alumina crucibles (5 mm diameter) on a TA Instruments Q600. Standard sample characterisation was performed with temperature ramping of 5 °C min−1 in the range between 20 and 800 °C under a flow of inert air. In-situ experiment with isothermal TGA (temperature is kept constant and the sample weight is recorded as a function of time) was performed under no flow (for the hydrolysis reaction).

Optical microscopy

Optical microscopy images were recorded on an Olympus BX53 microscope in transmission mode. The instrument was equipped with two linear polarizers (Olympus U-POT), which were oriented as indicated, and an Olympus DPT2 camera (Olympus Schweiz AG, Volketswil, Switzerland).

HRTEM

HRTEM images were obtained using a JEM 2100 microscope (JEOL Ltd, Japan) with an operation voltage of 200 kV.

Gas adsorption experiments

Gas sorption studies were undertaken using an ASAP 2020 system, Micromeritics Instrument Corporation (Norcross, Georgia, USA). ≈100 mg of HOPE SCs were transferred to a sample tube and evacuated under vacuum at 25 °C on the gas adsorption apparatus until the outgassing rate was <5 μm Hg to give fully desolvated material. All gases used were of 99.999% purity. Helium was used for the free-space determination after sorption analysis. Adsorption isotherms were measured at 77 K using a liquid nitrogen bath.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Crystallographic data (excluding structure factors) are available as Supplementary Data 1, 2, and have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre under CCDC 2428973 ([EtZn(BA)]4). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

DiSalvo, F. J. Solid-state chemistry: a rediscovered chemical frontier. Science 247, 649–655 (1990).

Kumar, A. et al. Solid-state reaction synthesis of nanoscale materials: strategies and applications. Chem. Rev. 122, 12748–12863 (2022).

McDermott, M. J. et al. Assessing thermodynamic selectivity of solid-state reactions for the predictive synthesis of inorganic materials. ACS Cent. Sci. 9, 1957–1975 (2023).

Mottillo, C. et al. Mineral neogenesis as an inspiration for mild, solvent-free synthesis of bulk microporous metal–organic frameworks from metal (Zn, Co) oxides. Green. Chem. 15, 2121–2131 (2013).

Qi, F., Stein, R. S. & Friščić, T. Mimicking mineral neogenesis for the clean synthesis of metal–organic materials from mineral feedstocks: Coordination polymers, MOFs and metal oxide separation. Green. Chem. 16, 121–132 (2014).

Budny-Godlewski, K., Justyniak, I., Leszczyński, M. K. & Lewiński, J. Mechanochemical and slow-chemistry radical transformations: a case of diorganozinc compounds and TEMPO. Chem. Sci. 10, 7149–7155 (2019).

Martinolich, A. J., Kurzman, J. A. & Neilson, J. R. Circumventing diffusion in kinetically controlled solid-state metathesis reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 11031–11037 (2016).

Todd, P. K. & Neilson, J. R. Selective formation of yttrium manganese oxides through kinetically competent assisted metathesis reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 1191–1195 (2019).

Kamm, G. E. et al. Relative kinetics of solid-state reactions: the role of architecture in controlling reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 11975–11979 (2022).

Bury, W. et al. tert-Butylzinc hydroxide as an efficient predesigned precursor of ZnO nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 47, 5467–5469 (2011).

Sokołowski, K. et al. Tert-butyl (tert-butoxy) zinc hydroxides: hybrid models for single-source precursors of ZnO nanocrystals. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 5488–5495 (2015).

Krupiński, P., Kornowicz, A., Sokołowski, K., Cieślak, A. M. & Lewiński, J. Applying mechanochemistry for bottom-up synthesis and host–guest surface modification of semiconducting nanocrystals: a case of water-soluble β-cyclodextrin-coated zinc oxide. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 7817–7823 (2016).

Krupiński, P. et al. From uncommon ethylzinc complexes supported by ureate ligands to water-soluble zno nanocrystals: a mechanochemical approach. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 1540–1549 (2021).

Wenger, L. E. & Hanusa, T. P. Synthesis without solvent: consequences for mechanochemical reactivity. Chem. Commun. 59, 14210–14222 (2023).

Lim, X. The slow-chemistry movement. Nature 524, 20–21 (2015).

Huskić, I., Lennox, C. B. & Friščić, T. Accelerated ageing reactions: towards simpler, solvent-free, low energy chemistry. Green. Chem. 22, 5881–5901 (2020).

Sharma, V. K., Filip, J., Zboril, R. & Varma, R. S. Natural inorganic nanoparticles – formation, fate, and toxicity in the environment. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 8410–8423 (2015).

Hochella, M. F. et al. Natural, incidental, and engineered nanomaterials and their impacts on the Earth system. Science 363, (2019).

Grzybowski, B. A. & Huck, W. T. S. The nanotechnology of life-inspired systems. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 585–592 (2016).

Nudelman, F. & Sommerdijk, N. A. J. M. Biomineralization as an inspiration for materials chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 6582–6596 (2012).

Ahmed, T. & Edvinsson, T. Optical quantum confinement in ultrasmall ZnO and the effect of size on their photocatalytic activity. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 6395–6404 (2020).

Mahesh, A., Kumar, G. P., Jawahar, I. N. & Biju, V. Temperature dependent photoluminescence spectra of nanocrystalline zinc oxide: effect of processing condition on the excitonic and defect mediated emissions. Chem. Phys. Impact 8, 100456 (2024).

Atwood, J. L., Barbour, L. J., Jerga, A. & Schottel, B. L. Guest Transport in a Nonporous Organic Solid via Dynamic van der Waals Cooperativity. Science 298, 1000–1002 (2002).

Thallapally, P. K. et al. Gas-induced transformation and expansion of a non-porous organic solid. Nat. Mater. 7, 146–150 (2008).

Jones, J. T. A. et al. On–Off Porosity Switching in a Molecular Organic Solid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 749–753 (2011).

Nikolayenko, V. I. et al. Reversible transformations between the non-porous phases of a flexible coordination network enabled by transient porosity. Nat. Chem. 15, 542–549 (2023).

Jie, K., Zhou, Y., Li, E. & Huang, F. Nonporous adaptive crystals of pillararenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 2064–2072 (2018).

Yan, M., Wang, Y., Chen, J. & Zhou, J. Potential of nonporous adaptive crystals for hydrocarbon separation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 6075–6119 (2023).

Sokołowski, K. et al. Stabilization towards Air and Structure Determination of Pyrophoric ZnR2 Compounds via Supramolecular Encapsulation. Sci. Adv. 11, eadt7372 (2025).

Chamorro, J. R. & McQueen, T. M. Progress toward Solid State Synthesis by Design. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 2918–2925 (2018).

McDermott, M. J., Dwaraknath, S. S. & Persson, K. A. A graph-based network for predicting chemical reaction pathways in solid-state materials synthesis. Nat. Commun. 12, 3097 (2021).

Bury, W., Justyniak, I., Prochowicz, D., Wróbel, Z. & Lewiński, J. Oxozinc carboxylates: a predesigned platform for modelling prototypical Zn-MOFs’ reactivity toward water and donor solvents. Chem. Commun. 48, 7362–7364 (2012).

Krupiński, P. et al. Tetrahedral M4 (μ4-O) Motifs Beyond Zn: efficient one-pot synthesis of oxido–amidate clusters via a transmetalation/hydrolysis approach. Inorg. Chem. 61, 7869–7877 (2022).

Prochowicz, D., Nawrocki, J., Terlecki, M., Marynowski, W. & Lewinski, J. Facile mechanosynthesis of the archetypal Zn-based metal–organic frameworks. Inorg. Chem. 57, 13437–13442 (2018).

Terlecki, M. et al. ZnO Nanoplatelets with controlled thickness: atomic insight into facet-specific bimodal ligand binding using DNP NMR. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2105318 (2021).

Wolska-Pietkiewicz, M. et al. Towards bio-safe and easily redispersible bare ZnO quantum dots engineered via organometallic wet-chemical processing. Chem. Eng. J. 455, 140497 (2023).

Bordwell, F. G. & Fried, H. E. Acidities of the hydrogen-carbon protons in carboxylic esters, amides, and nitriles. J. Org. Chem. 46, 4327–4331 (1981).

Lewiński, J., Śliwiński, W., Dranka, M., Justyniak, I. & Lipkowski, J. Reactions of [ZnR2 (L)] complexes with dioxygen: A new look at an old problem. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 118, 4944–4947 (2006).

Zelga, K. et al. Synthesis, structure and unique reactivity of the ethylzinc derivative of a bicyclic guanidine. Dalton Trans. 41, 5934–5938 (2012).

Leszczyński, M. K., Justyniak, I., Zelga, K. & Lewiński, J. From ethylzinc guanidinate to [Zn 10 O 4]-supertetrahedron. Dalton Trans. 46, 12404–12407 (2017).

Prochowicz, D., Sokołowski, K. & Lewiński, J. Zinc hydroxides and oxides supported by organic ligands: synthesis and structural diversity. Coord. Chem. Rev. 270, 112–126 (2014).

Szlachetko, J. et al. Hidden gapless states during thermal transformations of preorganized zinc alkoxides to zinc oxide nanocrystals. Mater. Horiz. 5, 905–911 (2018).

Vines, F., Iglesias-Juez, A., Illas, F. & Fernandez-Garcia, M. Hydroxyl identification on ZnO by infrared spectroscopies: theory and experiments. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 1492–1505 (2014).

Shtukenberg, A. G. et al. Crystals of benzamide, the first polymorphous molecular compound, are helicoidal. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 132, 14701–14709 (2020).

Chwojnowska, E., Wolska-Pietkiewicz, M., Grzonka, J. & Lewiński, J. An organometallic route to chiroptically active ZnO nanocrystals. Nanoscale 9, 14782–14786 (2017).

Grala, A. et al. ‘Clickable’ZnO nanocrystals: the superiority of a novel organometallic approach over the inorganic sol–gel procedure. Chem. Commun. 52, 7340–7343 (2016).

Lee, D. et al. Disclosing interfaces of ZnO nanocrystals using dynamic nuclear polarization: sol-gel versus organometallic approach. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 131, 17323–17328 (2019).

Badoni, S. et al. Atomic-level structure of the organic-inorganic interface of colloidal zno nanoplatelets from dynamic nuclear polarization-enhanced NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 27655–27667 (2024).

Spanhel, L. & Anderson, M. A. Semiconductor clusters in the sol-gel process: quantized aggregation, gelation, and crystal growth in concentrated zinc oxide colloids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 2826–2833 (1991).

Makuła, P., Pacia, M. & Macyk, W. How to correctly determine the band gap energy of modified semiconductor photocatalysts based on UV–Vis spectra. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 6814–6817 (2018).

Huang, F., Zhang, H. & Banfield, J. F. The role of oriented attachment crystal growth in hydrothermal coarsening of nanocrystalline ZnS. J. Phys. Chem. B. 107, 10470–10475 (2003).

Xue, X., Penn, R. L., Leite, E. R., Huang, F. & Lin, Z. Crystal growth by oriented attachment: kinetic models and control factors. CrystEngComm 16, 1419–1429 (2014).

Li, D. et al. Direction-specific interactions control crystal growth by oriented attachment. Science 336, 1014–1018 (2012).

Zhang, J., Huang, F. & Lin, Z. Progress of nanocrystalline growth kinetics based on oriented attachment. Nanoscale 2, 18–34 (2010).

Huang, F., Zhang, H. & Banfield, J. F. Two-stage crystal-growth kinetics observed during hydrothermal coarsening of nanocrystalline ZnS. Nano. Lett. 3, 373–378 (2003).

Ali, M. & Winterer, M. ZnO nanocrystals: surprisingly ‘alive’. Chem. Mat. 22, 85–91 (2010).

Von Euw, S. et al. Solid-state phase transformation and self-assembly of amorphous nanoparticles into higher-order mineral structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 12811–12825 (2020).

Lin, M. Y. et al. Universality in colloid aggregation. Nature 339, 360–362 (1989).

Cao, D., Gong, S., Shu, X., Zhu, D. & Liang, S. Preparation of ZnO nanoparticles with high dispersibility based on oriented attachment (OA) process. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 14, 210 (2019).

Rodnyi, P. A. & Khodyuk, I. V. Optical and luminescence properties of zinc oxide. Opt. Spectrosc. 111, 776–785 (2011).

Mohanan, J. L., Arachchige, I. U. & Brock, S. L. Porous semiconductor chalcogenide aerogels. Science 307, 397–400 (2005).

Ziegler, C. et al. Modern inorganic aerogels. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 13200–13221 (2017).

Matter, F., Luna, A. L. & Niederberger, M. From colloidal dispersions to aerogels: How to master nanoparticle gelation. Nano Today 30, 100827 (2020).

Peng, Y. et al. Two-step nucleation mechanism in solid–solid phase transitions. Nat. Mater. 14, 101–108 (2015).

Agilent Technologies. CrysAlisPro, Version 1.171.35.21b.

Sheldrick, G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr A 64, 112–122 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the National Science Centre (Grant MAESTRO 11, No. 2019/34/A/ST5/00416) for financial support (A.B., I.J. and J.L.). The authors thank M. Terlecki (Faculty of Chemistry, WUT) and J. Nawrocki (ICP PAS) for assistance with single-crystal synthesis; P. Bernatowicz (ICP PAS) for assistance with CP-MAS NMR measurements; A. A. Kowalska (ICP PAS) for assistance with Raman spectroscopy; Z. Kaszkur (ICP PAS) for assistance with TGA/DSC interpretations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B., K.S., and J.L. conceived the project, designed the research, and provided interpretation of the growth and aggregation mechanism of nanocrystals, as well as analysed the data and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. A.B. performed the materials synthesis and planned and carried out the in-situ and ex-situ experiments, as well as collected and processed most of the data. K.S and P.R. contributed to materials preparation and data collection. P.W.M. assisted with SAXS experiments and data processing. I.J. performed the SCXRD measurements and crystal structure analysis. A.M.C. assisted with data interpretation. J.L. supervised and guided the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shashank Mishra, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Borkenhagen, A., Sokołowski, K., Majewski, P.W. et al. Chemical weathering of molecular single crystals to monoliths of quantum dots. Nat Commun 16, 10254 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65113-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65113-3