Abstract

The 15-minute city concept promotes accessibility to daily needs within multifunctional neighbourhoods but often overlooks urban nature and biodiversity, missing an opportunity to merge human and non-human requirements into urban design. In this perspective, we propose integrating urban nature and its biodiversity into the 15-minute city concept to meet both human needs and biodiversity conservation goals. This integration requires urban planning to incorporate natural elements with high social-ecological value, such as pocket parks and community gardens, to support social cohesion, recreation, and habitat connectivity. Aligning with global biodiversity initiatives, this approach can enhance urban life for both people and nature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A majority of the world’s human population lives in cities today, while a majority of the world’s plant and animal populations are threatened by human settlement encroachment1. Urbanisation and the impact on biodiversity creates two fundamental challenges in the anthropocene: to push for sustainable urban development for people, and to maintain and create liveable habitat for nature and its biodiversity in and around human settlements. Although these contemporary challenges are related, solutions to address them remain largely separate2. For example, public administration in urban planning may have different interests than environmental protection agencies and limited communication between actors, which may result in differences between the implementation of environmental and spatial planning policies3,4.

Missing institutional mechanisms may limit the capacity of urban planners to effectively integrate nature conservation objectives5. Fragmented organizational structures that hinder communication among planning and environmental professionals can further lead to missed opportunities to develop urban environments for people and nature. A strategic alignment of different urban planning strategies through the collaboration of residential, infrastructure, green and blue infrastructure, social and health departments may increase the livability of urban environments for people and nature6. Such a strategic alignment requires new planning and conservation concepts and/or frameworks that allows an integrated, collaborative work towards shared goals. In other words, we need approaches that can be a win-win for both objectives, creating livable cities for both human and non-human life.

One urban planning concept that we see that has win-win potential for working towards shared goals is the increasingly popular “15-minute city” urban planning concept. The 15-minute city concept aims to reorganize urban life within a multifunctional urban neighborhood, in which all the necessary functions and needs of city dwellers (living, working, shopping, education or recreation) can be reached within 15 minutes by bike or on foot7. The idea of a 15-minute city is that city dwellers find essential necessary activity options and functions already in their neighborhoods, reducing the need for driving or public transport8. A 15-minute city may also foster relationships with neighbors, a sense of place, and improve the social connectedness within the neighborhood. Thinking in minutes to the next proximate activity or function, rather than in distance, is suggested to reduce car trip duration and travel time, limit potential encounters with urban stressors (e.g., traffic, noise) and enhance the overall quality of human life in the city. The 15-minute city is one of several urban planning concepts emerging for contemporary urban life, with some potential drawbacks including risks of gentrification, social segregation, and the so far limited availability of data on efficiency of social and environmental services at larger scales9. Nevertheless, this proximity-focused “city of short distances” has attracted international attention and has been implemented in neighborhoods and districts in Paris, Melbourne, Oslo, Bogota and other cities across diverse socioeconomic and income levels8,10,11,12. Indeed, a review in 2024 found that 98 cities worldwide have adopted 15-minute city practices at the neighborhood to national level, with 414 planning practices implemented12. Implementation in different countries exists under concepts working towards parallel objectives, such as ‘Complete Neighbourhoods’ in Portland (USA), ‘Superblocks’ in Barcelona (Spain), and ‘15-Minute Community Life Cycle’ in Guangzhou (China)12.

However, what has largely been overlooked in the 15-minute city implementation is the proximal needs of nature and non-human life. The 15-minute concept was derived largely from an engineering, physics and mobility perspective where the focus is placed on human needs, mobility, and activity10. There has been no focus on the potential value of the 15-minute city concept for maintaining and creating quality habitat for not just people and their daily needs and activities, but also for supporting plant and animal life, i.e., constituents of urban biodiversity. There is some mention of biodiversity as a subsequent benefit of the 15-minute city in recent reviews of the concept13, but an explicit incorporation of urban biodiversity’s needs in the concept and in recommendations for its implementation from the start is largely missing or not considered as a potential dual focus. The 15-minute city has, thus, largely been “biodiversity blind” in urban planning practice.

At the same time, cities worldwide are developing urban nature and biodiversity strategies and implementing aims to conserve habitat that is important for native and endemic species within metropolitan areas14. At the national level, alliances and movements are building networks for nature-oriented and biodiversity-oriented policies and plans. For example, in Germany, over 428 cities, municipalities and districts have committed to promoting species-rich natural areas in residential and surrounding areas and benefit from recommendations and support in implementation (“Municipalities for Biological Diversity” or “Kommunen für Biologische Vielfalt” in German15). There is also a growing movement around ‘Biodiversity Inclusive Design’6 and ‘biophilic design’, and subsequently a growing network of biophilic cities that commit to create and maintain space for biodiversity in the built environment16,17,18,19. Biophilic architecture concepts such as ‘Animal-Aided Design’ propose a method to systematically integrate animals – their life histories and subsequent needs—into the planning cycle of urban planning and design processes at the local neighborhood to landscape scale20. In Animal-Aided Design, the requirements of target species set boundary conditions for the planning process, while also inspiring the design itself.

In this perspective, we suggest that planning concepts such as the 15-minute city could align well with biodiversity conservation aims and urban initiatives to bring nature back into the city and connect people to nature and its biodiversity. In the context of global challenges such as biodiversity loss, climate change, progressive urbanisation and the extinction of nature experiences, we argue that it is critical to implement new ways of organizing urban coexistence for both people and nature that also contribute to the livability of cities for all.

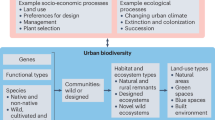

In what follows, we outline four principles for urban planning how we propose the 15-minute city as one urban planning concept that can support sustainable urban development to increase and maintain livability for human and non-human life based on the four dimensions of the concept7: proximity, density, diversity and digitalization. To visualize, Fig. 1 develops Moreno and colleagues’ (2021) four dimension concept of activity options and functions necessary for 15-minute neighborhoods (such as shown in ref. 21) further by presenting a biodiversity and ecological perspective. We discuss the feasibility, challenges and limitations of implementing the 15-minute city concept for human and non-human needs and present recommendations on how to overcome them and move forward.

Fig. 1. Left part: The concept of the 15-minute city adapted from Moreno, C. et al.: Introducing the “15-minute city”: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities 4, 93–111 (2021) published under CC-BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ and adapted from Kabisch, N. & Egerer, M. Die 15-Minuten-Stadt Paris: Ein Beispiel des stadtplanerischen Konzepts einer klimaresilienten und gesunden Stadt der Zukunft. Geogr. Rundsch. 76, 24–27 (2024), https://www.westermann.de/anlage/4662519. Right part: The 15-minute city concept from a biodiversity or ecological perspective. The used Figure elements (graphics / icons) were customly drawn by Imre Sebestyén (unitgraphics.com).

Principle 1—people, plants, and animals all have proximate needs

Important functions and needs of daily human life are accessible in the 15-minute neighborhood due to their proximity and density by means of sustainable mobility options. By focusing on the dimensions of proximity and density, the 15-minute city concept would generate independence from cars, reduce CO2 emissions and air pollution and thus contribute to healthier, climate-resilient, sustainable cities. In other words, having a high density of local amenities across the neighborhood that support the needs and activities of residents, means that people reduce travel time, thereby saving and optimizing their time as well as minimizing their ecological footprint13.

Proximity and density are dimensions also relevant for plant and animal species. Many mobile animal species such as wild bees or beetles have dispersal distances of just a few hundred meters, meaning that a high density of proximate and connected habitat patches and ecological niches distributed across a landscape with food and nesting resources can be valuable for supporting species movement and metapopulations. Hedgehogs may use connected networks of gardens to move across the landscape, finding shelter within these habitats22. Many well-connected parks and forest remnant patches can be important for insects, birds and bats23,24,25,26. For example, close proximity to other green spaces was a strong positive predictor of bird species occupancy in over 100 green spaces in Mexico City, while as green space isolation increased, bird richness or predicted occupancy decreased25.

Thus, networks of green spaces add to landscape connectivity, and can be a core component of a ‘proximate-thinking’ urban planning and a city of short distances to work towards reconciling needs for both humans and non-humans27,28,29. This is not just the case for people, but for non-human life that benefits from multifunctional neighborhoods with elements of green and blue infrastructure. The 15-minute city needs not only to be a human-centered concept, but can also consider connected habitat niches for non-human life of plants and animals.

Principle 2—(small) size and density matters for people and nature

Even small-scale amenities or habitat patches can have a powerful aggregate impact on the livability of cities for people as well as for biodiversity through their proximity and density, rather than e.g., just one large park far away30. Small urban green spaces such as ‘pocket parks’31 can promote healthy behaviors including physical activity and social interactions for residents, and are perceived as attractive in function and accessibility32,33. Small urban green spaces can also increase a sense of community when equipped with age appropriate infrastructure such as benches or playgrounds34, and decrease levels of psychological distress35. The availability of many small green spaces that are densely distributed across a city landscape can also increase people’s levels of general life satisfaction to contribute to overall wellbeing36, improve social cohesion37,38, and frequent visits can be easier to integrate into daily life when e.g. small pocket parks are located close to one’s home. Hence, many small urban green spaces located in proximity to people’s homes can provide similar positive wellbeing outcomes as few larger urban green spaces39. This was particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which lockdowns and restricted mobility led to increased use and value of proximate parks within people’s neighborhoods for recreation and socializing40.

While large, (semi-)natural urban green spaces are undoubtedly important for maintaining populations of plants and insects41,42, small urban green spaces in high density, well connected and distributed across the urban landscape can also support the taxonomic and functional diversity of plants and animals through the provisioning of food and shelter. For example, high bird species richness in green spaces less than 5 ha was shown to have not only high connectivity but also complex vegetation structure25. In a vegetation assessment of green spaces in Zurich, Switzerland, authors found that, while large green spaces individually have high plant species richness, small spaces <20 m2 collectively host greater plant beta species diversity (species turnover) than their larger green space counterparts43. Urban community gardens are also systems where, regardless of size, plant beta species diversity is high, especially of wild plants that coexist with their cultivated counterparts44. Thus, small vegetation patches along streetscapes, greening of treepits or small gardens can be very important for maintaining high species diversity within urban landscapes, and could be better considered in urban planning practices that consider incorporating habitats for biodiversity. Due to the scarcity of and difficulty to implement large parks or nature reserves in many cities45, promoting the conservation and integration of such small green spaces for biodiversity in city neighborhoods can be an easier conservation approach than the conservation and integration of a few large green spaces in cities25,30. While large urban greenspaces are important for metacommunity dynamics and species conservation by acting as population sources, small urban green spaces are very important for acting as diverse stepping stones, habitat niches and connectors among habitats in the landscape43,46. To meet urban biodiversity conservation aims in cities, such habitats must be abundant, connected, and well distributed across the landscape30.

Principle 3—diversity matters

Most contemporary global cities are very heterogeneous in their accessibility times to resources and services47, driving inequality and the need for including socio-economic and cultural factors into urban revitalization processes. The 15-minute city dimension of diversity refers on the one hand to the mixed-use functions in the neighborhood (diversity through residential, business and entertainment functions, social infrastructure) and on the other hand to the diversity of cultures and people living in and using the neighborhood. Diversity in the neighborhood could lead to an increase of social cohesion and an increase in social interaction. Diversity of cultures could have a positive impact on the local economy e.g. through selling opportunities of a variety of products, e.g. through tourism and the associated jobs created7. Ideally, restructuring neighborhoods to provide a diversity of functions for the daily human needs for a diversity of population groups in a 15-minute city would focus on an entire city area and thus avoid prioritizing only some city districts with specific functions (e.g., those of the wealthy), and counteract potential gentrification processes that could be triggered by developing neighborhoods according to the 15-minute city concept8,48.

Diversity is also important to consider when designing neighborhoods for a diversity of non-human life. The ability of urban green spaces to support biodiversity likely depends on the habitat characteristics of the space itself 49, as well as the level of urbanization surrounding the space25. The diversity of plant species, as well as the diversity of habitat features including canopy cover, tree diversity, tree height, layers of vegetation of a neighborhood park, forest or garden determine the diversity of animals25,50,51. For example, within city parks, bird species richness is positively affected by higher vegetation cover and the abundance of old and coniferous trees, and by deadwood2,52,53. Increasing diversity in vegetation characteristics of urban green spaces through conservation interventions or integrating understory vegetation within green spaces promotes bats, native birds, beetles, and other arthropods, and more native vegetation overall positively associates with all native taxa50. Projects such as Rewild my Street Britain illustrate how neighborhoods can incorporate diverse resources or niches for species within their neighborhood streets54. Conservation interventions such as implementing flower strips in urban parks or lawn areas to increase pollinator biodiversity aims at positively impacting biodiversity55, regulating ecosystem services and simultaneously providing health and wellbeing benefits for humans56.

The transformation of cities in the context of the 15-minute city for increasing and maintaining livability for both, human and non-human life should, thus, consider diversity of nature and biodiversity but also in relation to the values and practices towards biodiversity of different population groups with regards to their cultural or age or socioeconomic background57.

Principle 4—Digitalization to measure impact of the 15-minute city on people and nature

The digitalisation dimension is inspired by the smart city concept and enables improvements in the other three dimensions—density, proximity and diversity, e.g. through smart solutions, networking, data collection, automated government processes, but also through flexible spatial working hours and arrangements through home offices or coworking spaces58. Mobile apps and online platforms provide information and services related to public transport, bike-sharing schemes, and community resources enabling easier and more efficient commuting and access to local amenities.

Smart digital solutions have been used to improve and maintain ecosystem health also in urban areas. Smart solutions include, for instance, the construction and operation of city-wide climate measurement sensor networks to measure environmental parameters such as air temperature or soil humidity. The environmental parameters should help identify hot spot areas as priority areas for climate resilient development but also to identify hotspot areas where urban vegetation is stressed e.g. by drought59 to initiate mitigation actions. For example, the city of Hannover, Germany, was planning to implement smart city related measures linked to the sponge city idea. One of the city’s ideas was to collect rainwater in large subsurface cisterns and link them to the street trees to supply them with sufficient water based on a sensor network that provides real-time data on humidity, water level and soil moisture60.

New AI-based approaches, apps and species identification platforms are harnessing citizen science to better record species occurrences in urban areas, informing where biodiversity is in the city. Platforms such as ‘ObsIdentify’61 and ‘Dawn Chorus’62 use both visual and acoustic citizen science data to contribute to global databases on species presence.

Smart digital solutions in the 15-minute city can support both human and non-human needs by streamlining daily human processes, such as working arrangements and efficient planning of commutes. At the same time digital solutions in the 15-minute city can provide information about local species presence and contribute to ecosystem health. Using adaptive management techniques with smart sensor-based networks, these solutions dynamically adjust management practices in urban green spaces to effectively support local biodiversity under challenging environmental conditions.

One size does not fit all

The feasibility of implementing the 15-minute city concept for human and non-human needs comes with challenges and limitations concerning contextual applicability including competition for space, institutional and financial constraints, risk of green gentrification and differing public attitudes toward nature.

Highly dense and growing cities, particularly those with large-scale informal development and rapid urban expansion face competition for space with human settlement encroachment driving loss of natural spaces degrading habitat and biodiversity1. Limitation of and competition for space is shown in cities of developing countries63 but also in cities with long-term experience in formalized local planning. For example, Berlin, Germany has been challenged in the last decades to provide sufficient and affordable housing for a growing population number while at the same time biodiversity and sustainability strategies evolved such as the “Charta Stadtgrün”, a “Bee Strategy” and a push towards sustainable mobility (bicycles, pedestrians)64. Institutional limitations such as the division of responsibilities into different planning departments (residential development, green space planning, social infrastructure, technical infrastructure departments, etc.) but also a physical separation of departments located across different city districts and subsequent “isolation” and silo thinking remains a challenge for implementing multi-sectoral planning goals, particularly those in favor of biodiversity64. Departmental separation and limited cross-departmental collaboration may hinder implementing a 15-minute city concept that aligns with biodiversity conservation initiatives because it requires close collaboration of multiple city departments with their respective expertise in conservation, landscape planning and residential development.

Financial constraints and the costs of implementations means that investments are needed—for biodiversity supporting green infrastructure, maintenance, or smart technologies, which can be challenging in places where resources are limited. Implementing biodiversity measures such as flowering meadows or strips within an urban area can cost up to 10,000–20,000 Euros for a couple hundred square meters (e.g. as in the case of Munich, information conveyed verbally by planners) if e.g., soil additions are required, as well as high initial maintenance, and up to many thousands more if unsealing impervious surfaces and proper contaminant and rubble disposal are required. Thus, scarce finances or a lack of prioritization in decision making for such a transformative planning concept may reduce the feasibility of implementation.

There is a risk that implementing biodiversity measures as part of a 15-minute city concept may also lead to increased property values due to a (perceived) improved environmental quality. As neighborhoods are perceived as more desirable, rents and housing costs can rise making those areas less affordable for lower income groups leading to processes known as green gentrification, ecological gentrification65 or green grabbing—when new residential development takes place adjacent to existing or new green spaces66. Gentrified city areas have also been shown to harbor the highest mammal species richness, perhaps contributing to a disconnect of lower income groups from nature67. Green gentrification scholars have criticized the 15-minute city concept due to a risk of displacing groups who are unable to remain in upgraded neighborhood areas9,68.

Finally, public attitudes toward nature differ69 and may even translate into human-biodiversity conflicts and trade-offs that can emerge in cities with plenty of green stepping stones and visible biodiversity. Wildlife-related car accidents, uneven maintenance of green spaces, complaints of fallen fruits from trees, health issues related to allergenic plant species or vector borne diseases and safety concerns in vegetated areas are a very real aspect of such neighborhood landscapes70,71,72. This questions remains on how to balance benefits and risks of shared landscapes within a 15-minute city, reducing potential disservices from nearby nature.

An outlook on how we get there in practice

Overcoming challenges such as competition for space, institutional fragmentation, siloed thinking contextual feasibility and public attitudes hindering the transformation of neighborhoods into more biodiverse 15-minute cities requires a system’s approach that considers a cross-departmental and intersectoral collaboration, bringing together various urban planning departments to integrate the 15-minute city in a way that it is inclusive and multifunctional benefiting human and non-human spheres. Here we provide some recommendations on how to move forward:

Context matters; planners must work with it

for planning a biodiverse 15-minute city, planners should allow model concepts that provide ideas but are also flexible for local, context-driven adaptations68. This is not only from a social perspective, but also from a biodiversity perspective, as cities are located in different ecosystems and have different forms of urban nature (from e.g., coastal wetlands, rainforests to grasslands), and thereby plant and animal species pools and species of conservation concern73,74. Planning concepts must acknowledge the natural history of the landscape in order to incorporate native elements into planning processes75.

Competition of limited space could be reduced by integrating more small, connected habitat elements

Planning conflicts may pose that space for biodiversity conflicts with urban living, rather than seeing urban nature and biodiversity as a key component of the quality of urban life. Instead of ‘land sharing vs sparing’ in urban development76, urban planners should focus on increasing total habitat area—even if small and dispersed—and habitat connectivity30. The benefit of the 15-minute city is that small habitat elements or niches in the landscape such as pocket parks, verge gardening or tree-lined streetways could be relatively small, entry-level steps towards integrating habitat and ecological niches in neighborhoods. Even pop-up projects such as gardens or grasslands can increase biodiversity and improve the esthetic quality of neighborhoods—for example, pop-up grasslands in Melbourne, Australia increased arthropod species richness over six weeks (e.g., 2.5x more insect pollinator species, 3.5x more beetle species compared to a reference site77). Working towards a 15-minute city that takes a biophilic design or ‘Biodiversity Inclusive Design’ approach can consider focusing on implementing low-bar small habitats that have a positive aggregate effect on biodiversity and improve the esthetic quality of the landscape6.

Avoid green gentrification through inclusive governance

To avoid green gentrification processes, and to support nature connectedness for all, an inclusive governance approach is needed when designing biodiversity-oriented friendly cities for all human and non-human life. Adopting an inclusive governance approach helps integrate ecological goals with social equity objectives and can include strategies such as to ensure community involvement and participatory planning to reflect diverse voices and needs and differing public attitudes toward nature78. Also, the implementation of inclusive zoning laws and housing policies that protect low-income residents from rising house prices and rents and that ensure a portion of new developments remains affordable supports affordable housing alongside ecological improvements. Municipal planning agencies are requested to take a stronger role to integrate projects across sectors and prioritize policies that advocate for development without displacement and community-led or municipality-led tools such as community land trust or inclusionary zoning65,79.

Financial feasibility can be achieved through participatory approaches

Challenged by budget constraints and high costs of implementation, planning processes can utilize a soft governance approach that actively involves the local community through voluntary citizen initiatives, informal strategies, or awareness campaigns helping to transform neighborhoods rather than binding formal regulations or structural changes of a political and economic systems. In Munich, a project around mobility corridors involved grass roots planning and citizen initiatives and was based on workshops and other participatory formats with residents. In a “Mosaic Governance” approach, informal citizen activities can contribute to a biodiversity friendly environment e.g. such as the case of the 20 Walks Berlin in which citizen initiatives and NGOs jointly mapped and designed a network of green corridors80. The identified green corridors were later formally and politically approved and acknowledged. Mosaic Governance holds potential to advance just transformations through a 15-minute city idea for human and non-humans by enabling empowering, bridging, and linking pathways across diverse communities. Through establishing long-term collaborations between local governments, communities, and grassroots initiatives Mosaic Governances is a potential for just transitions which are sensitive to existing inequities81.

Public communication and education to address public fears, misunderstandings and attitudes

People have different attitudes toward biodiversity and its management in cities, either wanting it in their proximity or not82. Yet, biodiversity-focused planning depends on support from current but more importantly future generations. Cross generational and sectoral environmental education programs are needed to involve, educate and excite residents of all generations in urban greening initiatives focused on reducing fear, xenophobia and misunderstandings of urban biodiversity and simultaneously improving conditions for biodiversity83. Projects that involve co-creative processes to bring biodiversity into neighborhoods with diverse stakeholders in environmental education and urban greening can increase not only the acceptance of biodiversity but also integrate local knowledge and increase residents’ ownership in local biodiversity conservation30. For the 15-minute city, such local ownership and empowerment in improving socioecological conditions of a neighborhood can work to debunk fears around e.g., unwanted green space and green gentrification, social exclusion, or loss of freedoms on personal mobility9. Co-design and participation with residents, research and data from other 15-minute city success stories, as well as flexibility to local conditions are strategies to counteract misinformation by conspiracy theorists or skeptics as in the post-COVID-19 era, where there was a backlash of the 15-minute city approach9,68. In the context of a recently theorized ‘post-pandemic paranoid urbanism’, the 15 minute concept can and should be adapted to local social and geographical realities, communicated carefully to residents, and not considered a top-down framework84.

Monitor 15-minute city implementations to evaluate its impact on people and nature

The benefits of the 15-minute city are still largely speculative, and there is a need for more evidence on social as well as environmental impact of such a concept to further justify and adapt planning strategies for achieving social and environmental benefits. Providing this evidence may include surveys on resident life satisfaction, frequency of bike commuting, as well as monitoring of target species of e.g., birds, insects and/or wild plant populations.

Creating more-than human 15-minute cities for multiple aims

The Sustainable Development Goal 11 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development focuses on resilient, sustainable, safe and inclusive cities worldwide85. At the same time, urbanisation trends driven by increasing demand for housing and infrastructure go in hand with land sealing and the loss of open green and blue spaces for both human recreation as well as non-human needs. In the context of global changes such as climate change, ongoing urbanisation, biodiversity loss, pandemics and a loss of nature experiences, new ways of organizing urban coexistence for human and non-human life that also contributes to the livability of cities for both are needed.

An opportunity arises if topics that are collaboratively discussed with stakeholders about the opportunities, benefits, and challenges of the 15-minute city realisation incorporate multiple objectives, specifically around urban nature and biodiversity. If biodiversity and creating shared neighborhood landscapes for human and non-human life is discussed alongside topics of improved mobility or climate resilience, then it can be a strategic way to make people think about how to design their neighborhoods for their families, their neighbors, and also non-human residents. Participatory approaches in urban planning to increase collaborative planning and sustainable urban transformation86 can be a way to facilitate the planning and implementation of the 15-minute city by neighborhood residents7. Concepts such as living laboratories or pop-up information booths in public areas are giving residents a say in the design and implementation of neighborhood planning concepts that address issues such as climate change adaptation, mobility, or local food. These initiatives can also be better connected to those citizen driven initiatives that already engage for more nature and biodiversity in cities87.

In conclusion, what is special about the 15-minute city concept is that it offers a way in which people can physically and may even socially connect in their day-to-day work and play activities. Yet it also offers a way for people to connect with their nearby natural space, and forms of non-human life that also reside in cities—in essence, also their neighbors. As the extinction of nature experience becomes a growing phenomenon and a ‘pandemic’ in and of itself—also framed as “nature deficit disorder” by Richard Louv in 2005 in “Last Child in the Woods”88,89—addressing this global health issue by incorporating more proximate green space in cities is necessary. Developing cities multifunctional for both human and non-human inhabitants can be a way to foster relationships between people and nature, having nature and its biodiversity as a nearby amenity in the 15-minute city. Creating win-win solutions for people and nature can start with aligning goals in participatory planning procedures that are becoming mainstream. The challenge is now to adapt and implement such concepts within the existing built infrastructure of diverse global cities—from old medieval cities to Megacities—in a way that is fair, inclusive, and just for all: humans and non-humans.

References

Simkin, R. D., Seto, K. C., McDonald, R. I. & Jetz, W. Biodiversity impacts and conservation implications of urban land expansion projected to 2050. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, 1–10 (2022).

Sandström, U. G., Angelstam, P. & Khakee, A. Urban comprehensive planning - Identifying barriers for the maintenance of functional habitat networks. Landsc. Urban Plan. 75, 43–57 (2006).

Sager, T. Reviving Critical Planning Theory: Dealing with Pressure, Neo-liberalism, and Responsibility in Communicative Planning. (Routledge, 2013).

Simeonova, V. & van der Valk, A. Environmental policy integration: Towards a communicative approach in integrating nature conservation and urban planning in Bulgaria. Land Use Policy 57, 80–93 (2016).

Peyrache-Gadeau, V. Natural resources, innovative milieux and the environmentally sustainable development of regions. Eur. Plan. Stud. 15, 945–959 (2007).

Hernandez-Santin, C., Amati, M., Bekessy, S. & Desha, C. A review of existing ecological design frameworks enabling biodiversity inclusive design. Urban Sci. 6, 95 (2022).

Moreno, C., Allam, Z., Chabaud, D., Gall, C. & Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-minute city”: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities 4, 93–111 (2021).

Pozoukidou, G. & Chatziyiannaki, Z. 15-Minute City: Decomposing the New Urban Planning Eutopia. Sustainability 13, 928 (2021).

Marquet, O., Anguelovski, I., Nello-Deakin, S. & Honey-Rosés, J. Decoding the 15-Minute City Debate: Conspiracies, Backlash, and Dissent in Planning for Proximity. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 91, 117–125 (2024).

Allam, Z., Chabaud, D., Gall, C., Pratlong, F. & Moreno, C. Enter the 15-minute city: revisiting the smart city concept under a proximity based planning lens. in Resilient and Sustainable Cities 93–105 (Elsevier, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-91718-6.00002-5.

Di Marino, M., Tomaz, E., Henriques, C. & Chavoshi, S. H. The 15-minute city concept and new working spaces: a planning perspective from Oslo and Lisbon. Eur. Plan. Stud. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2022.2082837 (2022)

Teixeira, J. F. et al. Classifying 15-minute Cities: A review of worldwide practices. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 189, 1–27 (2024).

Khavarian-Garmsir, A. R., Sharifi, A. & Sadeghi, A. The 15-minute city: Urban planning and design efforts toward creating sustainable neighborhoods. Cities 132, 104101 (2023).

Nilon, C. H. et al. Planning for the future of urban biodiversity: A global review of city-scale initiatives. Bioscience 67, 332–342 (2017).

Kommunen für biologische Vielfalt e.V. Kommbio – Municipalities for Biodiversity in Germany. https://kommbio.de/kommbio-municipalities-for-biodiversity-in-germany/ (2025).

Beatley, T. Biophilic Cities. in Sustainable Built Environments. Encyclopedia of Sustainability Science and Technology Series (ed. Loftness, V.) 275–292 (Springer US, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-0684-1_1033.

Milliken, S., Kotzen, B., Walimbe, S., Coutts, C. & Beatley, T. Biophilic cities and health. Cities Heal. 7, 175–188 (2023).

Pedersen Zari, M. Understanding and designing nature experiences in cities: a framework for biophilic urbanism. Cities Heal. 7, 201–212 (2023).

Biophilic Cities. Biophilic Cities - Connecting Cities and Nature. https://www.biophiliccities.org/.

Weisser, W. W. & Hauck, T. E. Animal-Aided Design–planning for biodiversity in the built environment by embedding a species’ life-cycle into landscape architectural and urban design processes. Landsc. Res. 50, 146–167 (2024).

Kabisch, N. & Egerer, M. Die 15-Minuten-Stadt Paris: Ein Beispiel des stadtplanerischen Konzepts einer klimaresilienten und gesunden Stadt der Zukunft. Geogr. Rundsch. 76, 24–27 (2024).

App, M., Strohbach, M. W., Schneider, A. K. & Schröder, B. Making the case for gardens: Estimating the contribution of urban gardens to habitat provision and connectivity based on hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus). Landsc. Urban Plan 220, 104347 (2022).

Hale, J. D., Fairbrass, A. J., Matthews, T. J. & Sadler, J. P. Habitat composition and connectivity predicts bat presence and activity at foraging sites in a Large UK conurbation. PLoS One 7, e33300 (2012).

Graffigna, S., González-Vaquero, R. A., Torretta, J. P. & Marrero, H. J. Importance of urban green areas’ connectivity for the conservation of pollinators. Urban Ecosyst. 27, 417–426 (2024).

Oropeza-Sánchez, M. T. et al. Urban green spaces with high connectivity and complex vegetation promote occupancy and richness of birds in a tropical megacity. Urban Ecosyst. 28, 50 (2025).

Kang, W., Minor, E. S., Park, C.-R. & Lee, D. Effects of habitat structure, human disturbance, and habitat connectivity on urban forest bird communities. Urban Ecosyst. 18, 857–870 (2015).

Graviola, G. R., Ribeiro, M. C. & Pena, J. C. Reconciling humans and birds when designing ecological corridors and parks within urban landscapes. Ambio 51, 253–268 (2022).

Kirk, H. et al. Ecological connectivity as a planning tool for the conservation of wildlife in cities. MethodsX 10, 101989 (2023).

Croeser, T., Bekessy, S. A., Garrard, G. E. & Kirk, H. Nature-based solutions for urban biodiversity: Spatial targeting of retrofits can multiply ecological connectivity benefits. Landsc. Urban Plan. 251, 105169 (2024).

Egerer, M., Karlebowski, S., Schoo, D. & Sturm, U. Growing gardens into neighborhoods through transdisciplinary research. Urban Urban Green. 100, 128481 (2024).

Balai Kerishnan, P. & Maruthaveeran, S. Factors contributing to the usage of pocket parks―A review of the evidence. Urban Urban Green. 58, 126985 (2021).

Dong, J., Guo, R., Guo, F., Guo, X. & Zhang, Z. Pocket parks-a systematic literature review. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 083003 (2023).

Wang, P., Zhou, B., Han, L. & Mei, R. The motivation and factors influencing visits to small urban parks in Shanghai, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 60, 127086 (2021).

Enssle, F. & Kabisch, N. Urban green spaces for the social interaction, health and well-being of older people— An integrated view of urban ecosystem services and socio-environmental justice. Environ. Sci. Policy 109, 36–44 (2020).

Ha, J., Kim, H. J. & With, K. A. Urban green space alone is not enough: A landscape analysis linking the spatial distribution of urban green space to mental health in the city of Chicago. Landsc. Urban Plan. 218, 104309 (2022).

Wu, L. & Chen, C. Does pattern matter? Exploring the pathways and effects of urban green space on promoting life satisfaction through reducing air pollution. Urban Urban Green. 82, 127890 (2023).

Shanahan, D. F. et al. Health benefits from nature experiences depend on dose. Sci. Rep. 6, 28551 (2016).

Jennings, V. & Bamkole, O. The relationship between social cohesion and urban green space: An avenue for health promotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 452 (2019).

Allard-Poesi, F., Matos, L. B. S. & Massu, J. Not all types of nature have an equal effect on urban residents’ well-being: A structural equation model approach. Health Place 74, 102759 (2022).

Liu, S. & Wang, X. Reexamine the value of urban pocket parks under the impact of the COVID-19. Urban Urban Green. 64, 1–9 (2021).

Soga, M., Yamaura, Y., Koike, S. & Gaston, K. J. Woodland remnants as an urban wildlife refuge: a cross-taxonomic assessment. Biodivers. Conserv. 23, 649–659 (2014).

Planchuelo, G., von Der Lippe, M. & Kowarik, I. Untangling the role of urban ecosystems as habitats for endangered plant species. Landsc. Urban Plan. 189, 320–334 (2019).

Vega, K. A. & Küffer, C. Promoting wildflower biodiversity in dense and green cities: The important role of small vegetation patches. Urban Urban Green. 62, 127165 (2021).

Sexton, A. N. et al. Urban pollinator communities are structured by local-scale garden features, not landscape context. Landsc. Ecol. 40, 1–16 (2025).

Xun, B., Yu, D., Liu, Y., Hao, R. & Sun, Y. Quantifying isolation effect of urban growth on key ecological areas. Ecol. Eng. 69, 46–54 (2014).

Omar, M. et al. Colonization and extinction dynamics among the plant species at tree bases in Paris (France). Ecol. Evol. 9, 8414–8428 (2019).

Bruno, M., Monteiro Melo, H. P., Campanelli, B. & Loreto, V. A universal framework for inclusive 15-minute cities. Nat. Cities 1, 633–641 (2024).

Gorynski, B., Müller, T. & Gelsin, A. Beschleunigt die Corona-Pandemie den Weg zu intelligenteren Städten? in Die Europäische Stadt nach Corona - Strategien für resiliente Städte und Immobilien (eds. Just, T. & Plößl, F.) 165–183 (Springer Nature, 2021).

Sexton, A. N., Conitz, F., Sturm, U. & Egerer, M. Wild plants drive biotic differentiation across urban gardens. Ecol. Evol. 15, e71527 (2025).

Threlfall, C. G. et al. Increasing biodiversity in urban green spaces through simple vegetation interventions. J. Appl. Ecol. 54, 1874–1883 (2017).

Kaushik, M., Tiwari, S. & Manisha, K. Habitat patch size and tree species richness shape the bird community in urban green spaces of rapidly urbanizing Himalayan foothill region of India. Urban Ecosyst. 25, 423–436 (2022).

Fernández-Juricic, E. & Jokimäki, J. A habitat island approach to conserving birds in urban landscapes: case studies from southern and northern Europe. Biodivers. Conserv. 10, 2023–2043 (2001).

La Sorte, F. A., Aronson, M. F. J., Lepczyk, C. A. & Horton, K. G. Area is the primary correlate of annual and seasonal patterns of avian species richness in urban green spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 203, 103892 (2020).

Moxon, S. Rewild my Street. https://www.rewildmystreet.org/ (2025).

Hofmann, M. M. & Renner, S. S. One-year-old flower strips already support a quarter of a city’s bee species. J. Hymenopt. Res. 75, 87–95 (2020).

Chinga, J., Murúa, M. & Gelcich, S. Exploring perceptions towards biodiversity conservation in urban parks: Insights on acceptability and design attributes. J. Urban Manag. 13, 425–436 (2024).

Vierikko, K. et al. Considering the ways biocultural diversity helps enforce the urban green infrastructure in times of urban transformation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 22, 7–12 (2016).

Chanson, G. & Sakka, E. Coworking and the 15-Minute City. in Resilient and Sustainable Cities 3–14 (Elsevier, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-91718-6.00003-7.

Kraemer, R., Remmler, P., Bumberger, J. & Kabisch, N. Running a dense air temperature measurement field campaign at the urban neighbourhood level: Protocol and lessons learned. MethodsX 9, 101719 (2022).

Landeshauptstadt Hannover. HANNOVATIV-Hitze.Wasser.Management. https://www.hannovativ.com/projekt-hitze-wasser-management/ (2025).

Observation International. ObsIdentify. https://observation.org/apps/obsidentify/ (2025).

Dawn Chorus. Dawn Chorus. https://dawn-chorus.org/en/.

Ramaiah, M. & Avtar, R. Urban green spaces and their need in cities of rapidly urbanizing India: A review. Urban Sci. 3, 1–16 (2019).

Hansen, R. et al. Transformative or piecemeal? Changes in green space planning and governance in eleven European cities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 0, 1–24 (2022).

Anguelovski, I. (In)Justice in Urban Greening and Green Gentrification. in The Barcelona School of Ecological Economics and Political Ecology. (eds. Villamayor-Tomas, S. & Muradian, R.) 235–247 (Springer, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22566-6_20.

García-Lamarca, M. et al. Urban green grabbing: Residential real estate developers discourse and practice in gentrifying Global North neighborhoods. Geoforum 128, 1–10 (2022).

Fidino, M. et al. Gentrification drives patterns of alpha and beta diversity in cities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2318596121 (2024).

Marquet, O., Mojica, L., Fernández-Núñez, M. B. & Maciejewska, M. Pathways to 15-Minute City adoption: Can our understanding of climate policies’ acceptability explain the backlash towards x-minute city programs? Cities 148, 104878 (2024).

Fischer, L. K. et al. Public attitudes toward biodiversity-friendly greenspace management in Europe. Conserv. Lett. 13, 1–12 (2020).

Von Döhren, P. & Haase, D. Ecosystem disservices research: A review of the state of the art with a focus on cities. Ecol. Indic. 52, 2015 (2015).

Rega-Brodsky, C. C., Nilon, C. H. & Warren, P. S. Balancing urban biodiversity needs and resident preferences for vacant lot management. Sustain 10, 1–21 (2018).

Riley, C. B., Perry, K. I., Ard, K. & Gardiner, M. M. Asset or liability? Ecological and sociological tradeoffs of urban spontaneous vegetation on vacant land in shrinking cities. Sustain 10, 1–19 (2018).

Ives, C. D. & Kelly, A. H. The coexistence of amenity and biodiversity in urban landscapes. Landsc. Res. 41, 495–509 (2016).

Gentili, R. et al. Urban refugia sheltering biodiversity across world cities. Urban Ecosyst. 27, 219–230 (2024).

Ives, C. D., Taylor, M. P., Nipperess, D. A. & Davies, P. New directions in urban biodiversity conservation: The role of science and its interaction with local environmental policy. Environ. Plan. Law J. 27, 249–271 (2010).

Lin, B. B. & Fuller, R. A. FORUM: Sharing or sparing? How should we grow the world’s cities?. J. Appl. Ecol. 50, 1161–1168 (2013).

Mata, L. et al. Punching above their weight: the ecological and social benefits of pop-up parks. Front. Ecol. Environ. 17, 341–347 (2019).

Kabisch, N., Frantzeskaki, N. & Hansen, R. Principles for urban nature-based solutions. Ambio 51, 1388–1401 (2022).

Rigolon, A. & Németh, J. “We’re not in the business of housing:” Environmental gentrification and the nonprofitization of green infrastructure projects. Cities 81, 71–80 (2018).

Buijs, A. et al. Mosaic governance for urban green infrastructure: Upscaling active citizenship from a local government perspective. Urban Urban Green. 40, 53–62 (2019).

Buijs, A. E. et al. Advancing environmental justice in cities through the Mosaic Governance of nature-based solutions. Cities 147, 104799 (2024).

Straka, T. M. et al. Beyond values: How emotions, anthropomorphism, beliefs and knowledge relate to the acceptability of native and non-native species management in cities. People Nat. 4, 1485–1499 (2022).

Kowarik, I., Busmann, W. & Stopka, I. Unconventional programmes to promote experiences with urban nature in Berlin. People Nat. 1–19 https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.70013 (2025).

Caprotti, F., Duarte, C. & Joss, S. The 15-minute city as paranoid urbanism: Ten critical reflections. Cities 155, 105497 (2024).

United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021. 136, 64 (2021).

Raynor, K. E., Doyon, A. & Beer, T. Collaborative planning, transitions management and design thinking: evaluating three participatory approaches to urban planning. Aust. Plan. 54, 215–224 (2017).

Murgante, B. & Di Ruocco, I. Public Participation in the 15-Minute City. The Role of ICT and Accessibility to Reduce Social Conflicts. in Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2024 Workshops. ICCSA 2024 (eds. Gervasi, O. et al.) 77–92 (Springer). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-65238-7_6 (2024).

Chawla, L. Benefits of nature contact for children. J. Plan. Lit. 30, 433–452 (2015).

Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods. (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2008).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Caroline Böhm and Imre Sebestyén (unitgraphics.com) for supporting us in the visualization of Fig. 1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: N.K. and M.E., Writing original Draft: N.K. and M.E., Figure development contribution: N.K. and M.E.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kabisch, N., Egerer, M. Resetting the clock by integrating urban nature and its biodiversity into the 15-minute city concept. Nat Commun 16, 9281 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65170-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65170-8