Abstract

Long-range imaging in the Mid-wave infrared (MWIR) is crucial for defense, industrial and environmental applications, requiring very large aperture (~100-1000 mm) lenses for high-resolution imaging. Glass-based refractive optics make such systems bulky and expensive. Metalenses are lightweight alternatives but face fabrication limits at large apertures. We proposed a computational imaging strategy, the Golay metalens, combining (a) a small aperture array in designed spatial configuration and (b) a reconstruction algorithm that recover high-resolution, high-contrast images as though obtained by a single large aperture lens. The design is inherently scalable to larger apertures. A prototype in 89 mm diameter, 356 mm focal length was demonstrated, achieving near diffraction-limited performance enhanced by an image reconstruction algorithm with neural network-based denoising. A large recursive Golay metalens was further designed, demonstrating improved spatial resolution in simulations. Our development represents a significant step toward practical, high-performance MWIR imaging systems that are both scalable and accessible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mid-wave infrared (MWIR: 3–5 μm) imaging is known for its sensitivity to temperature variations and ability to penetrate atmospheric haze, which makes it effective for target detection and tracking1, remote 3D imaging2, and astronomical observations3. Most of these applications, however, necessitate long-range imaging with large aperture optics, and traditional MWIR refractive lenses become increasingly heavy and bulky as the aperture size grows. Metalenses are ultrathin optical elements that focus light through subwavelength structures, offering lightweight designs, potential freedom from spherical aberrations4,5, and complex phase customization, providing more degrees of freedom than traditional lenses, enabling various applications6,7,8,9,10,11. Initial meta-optics were fabricated primarily using electron beam lithography with the size limited to ~103–104 λ12. Advances in nano-fabrication13 have enabled apertures of ~105 λ14,15,16,17 through deep ultraviolet lithography, nanoimprinting18 and direct laser writing19. The largest reported metalens (100 mm diameter), for example, was created by stitching multiple exposure fields with different photolithography reticles during each exposure cycle, leading to aberrations and efficiency decrease compared to single-shot photolithography. Scaling such large metalenses to even larger apertures remains extremely challenging.

A promising approach for building large aperture systems involves using sparse aperture configurations, exemplified by the Atacama Large Millimeter Array20, a 66-telescope array where smaller units combine to achieve the resolution of a larger aperture. In optical sparse aperture systems21, electromagnetic fields directly interfere on a single focal plane detector. Applying metalenses in a sparse aperture configuration helps overcome size limitations while maintaining a lightweight design. However, design and fabrication challenges remain due to their differences from traditional refractive lenses, leading current research to still be in its early stages. This includes simulation studies22,23 and experimental demonstrations of simple configurations with up to 4 sub-apertures, all at the micron scale24,25,26,27, which are unsuitable for long-range imaging. For such applications, larger apertures with more sub-apertures in complex arrangements, ranging from centimeter to meter scale, are recommended. Sparse apertures generate large, asymmetric point spread functions (PSFs) leading to perceptually blurry images, and metalenses have lower efficiencies, causing reduced signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) than standard lenses28. Thus, computational reconstruction is essential for these sparse aperture metalens systems, whose current works employ only basic techniques like Wiener filtering and the Richardson–Lucy algorithm, resulting in suboptimal outcomes. State-of-the-art deep learning-based image reconstruction methods, effective in addressing image degradation and noise29,30,31,32 have yet to be implemented.

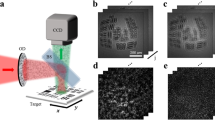

Here, we proposed a computational imaging system referred to as Golay metalens. Modified from the Golay array configuration33, which targets multiple sub-apertures and uses compact non-redundant autocorrelations to maximize spatial frequency bandwidth, our system features an 89 mm outer diameter with seven sub-apertures, operating in the MWIR (see Fig. 1a for system schematic). While the weight of the plano-convex lens scales as the cube of the focal length, the metalens scales only as a square, leading to an increasing weight disparity as focal length grows (Fig. 1b). Our Golay metalens realized a 15-fold weight reduction compared to an equivalent traditional refractive lens. Fabricated on an all-silicon platform using cost-effective direct laser writing, our system utilizes an effective image reconstruction method based on the half-quadratic splitting (HQS) technique with a deep learning-based denoiser prior, acquiring high-resolution images for objects with MWIR radiation. To address the need for larger apertures for higher spatial resolution at longer distances (Fig. 1c), we also designed and simulated a large recursive Golay metalens (outer diameter of 495.1 mm), formed by arranging 7 Golay6 + 1 metalenses as sub-apertures in a Golay6 + 1 configuration. Our Golay6 + 1 and Recursive Golay6 + 1 metalenses overcome the fabrication constraint on the maximum diameter of a single metalens (d), achieving a larger outer diameter (D) and offering scalable resolution enhancement factors (D/d) of 5.56 and 30.94, respectively. Taken together, our study paves the way for developing lightweight, cost-effective, and high-resolution imaging systems suitable for long-range MWIR applications.

a Schematic diagram of Golay metalens imaging in the mid-wave infrared (MWIR). b Comparison between the weight of a traditional silicon plano-convex lens and a metalens (both in a focal ratio (F/#) of 4 configuration) across different focal lengths. c Diffraction-limited resolution over distance for apertures with different resolution enhancement factors D/d, where D is the outer diameter of the sparse aperture system and d is the sub-aperture diameter (d = 80 mm in this case). d Schematic diagram of the Golay6 and Golay6+1 metalenses. The triangular lattice pattern with spacing L1, the central point (0, 0), the outer diameter D, and the sub-aperture diameter d are shown. The central sub-aperture is indicated by an arrow. e Simulated two-dimensional modulation transfer functions (2D MTFs, λ = 4.5 μm) for the Golay6 and the Golay6+1 metalenses. f Simulated one-dimensional modulation transfer function (1D MTF) comparison (λ = 4.5 μm) for the Golay6, the Golay6+1 metalenses, the center aperture and the effective aperture.

Results

Design of the 6+1 sub-aperture system

The Golay configuration is composed of arrays with non-redundant autocorrelations for broad yet compact spatial frequency coverage and typically targets a number of sub-apertures that is a multiple of three33. Increasing the number of sub-apertures (e.g., from 3 to 6 or 9) improves spatial frequency sampling by extending the autocorrelation domain coverage. As demonstrated in Fig. S1a, MTF simulations clearly show this improvement when comparing Golay3, Golay6, and Golay9 configurations with uniform sub-aperture sizes and minimum spacing. The corresponding schematic diagrams of these three configurations are presented in Fig. S1b. Among these three configurations, Golay6 achieves a practical balance between imaging performance and manufacturability: its MTF coverage surpasses Golay3, while remaining more feasible than Golay9, as the latter’s complex coordinate arrangement presents significant fabrication challenges.

While Golay6 serves as a promising starting point, we expanded it to a 6 + 1 sub-aperture system (Golay6 + 1) by adding a central aperture, shown in the configuration image in Fig. 1d. The advantages of Golay6 + 1 over Golay6 arise from two key factors. First, the central sub-aperture was introduced to augment low and mid-frequency MTF response for better image quality. This improvement is clearly demonstrated in our MTF simulation comparisons between Golay6 + 1 and Golay6, as shown in Fig. 1e. Second, the central sub-aperture serves as a reference for alignment during both fabrication and operation. Having a reference sub-aperture at the exact center of the wafer is crucial for achieving more efficient, precise, and stable alignment processes. In addition, adding an extra aperture increases the overall light-transmitting area, thereby enhancing SNR of the captured image.

The six peripheral sub-apertures in Golay6+1 are arranged on a uniform spacing triangular lattice (Fig. 1d), whose coordinates (xn, yn) for the nst sub-aperture are provided in Table S1 of the Supplementary Information. Taking the central point as coordinate (0, 0), the exact coordinates of the six surrounding sub-apertures can be calculated based on a fixed outer diameter. The detailed calculation is included in section S3 of the Supplementary Information.

The fill factor of the sparse aperture is another critical design consideration. It refers to the ratio of the total area of all sub-apertures that make up a sparse aperture system to the area of the circumscribed circle aperture that encloses the sub-apertures21, that can be calculated as follows:

where N is the number of sub apertures. Fig. S1c shows the horizontal and vertical MTF comparisons of the Golay6+1 metalens with the same outer diameter (D = 89 mm) but three different sub-aperture radius (d = 12, 16, 20 mm). With a consistent outer diameter, a smaller fill factor results in smaller sub-aperture radii, conserving material but sacrificing more mid-frequency information. To balance these two aspects, we selected the 6 + 1 sub-aperture system with a fill factor of 0.226 when d = 16 mm for our sparse aperture metalenses, with the resolution enhancement factor of 5.56 for our final design.

To evaluate performance differences, we conducted simulations comparing three configurations: the Golay6+1 aperture, a single central sub-aperture, and an effective circular aperture (42.3 mm diameter) matching the total light-collecting area of Golay6+1, all maintaining an identical 356 mm focal length. The MTF results in Fig. 1f indicate that the Golay6+1 configuration exhibits substantially better high-frequency response relative to both the effective aperture and the central sub-aperture, with the effective aperture showing better performance than the central sub-aperture in this regard. Corresponding PSF simulations in Fig. S1d reveal that Golay6 + 1 produces the sharpest PSF, collectively confirming its superior resolution capability. These simulations were conducted using the angular spectrum wave propagation method34 and a hyperbolic phase distribution35 across the entire circumscribed aperture to ensure that all sub-apertures focus on the same focal spot. Further details are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Meta-optics design and fabrication

We fabricated and experimentally tested the Golay6+1 metalens, the center aperture and the effective aperture. Within the aperture area, we employed the hyperbolic phase distribution, chosen for its robustness to fabrication imperfections and ability to directly focus the designed wavelength. To ensure that the alignment errors of the sub-aperture coordinates remain within acceptable fabrication tolerances, we conducted perturbation experiments. Specifically, to estimate the fabrication tolerance, the sub-apertures (excluding the central one) of the Golay6 + 1 configuration were randomly shifted in the ±X and ±Y directions within the range [−L, L], as shown in Fig. 2a. For each perturbation, the PSF was simulated, convolved with the ground truth image, and Gaussian noise was added before image reconstruction and peak-SNR (PSNR) computation. Using the effective aperture’s PSNR (29.94 dB) as our performance baseline, we aimed to ensure the perturbed Golay6+1 metalens maintained a PSNR no lower than this reference value. As shown in Fig. 2b, the Golay6+1 design demonstrated robust performance, achieving an average PSNR of 30.27 dB even with perturbations up to L = 50 μm, while still exceeding the effective aperture’s baseline performance. This demonstrates a high degree of robustness to reasonable fabrication errors.

a Configuration in which all apertures except the central aperture can be perturbed in both ±x and ±y directions. b Different perturbation limits and the corresponding average peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) for all perturbations within each limit, with the dash-dot line representing the PSNR of the unperturbed Golay aperture, and the dotted line representing the effective aperture’s PSNR. c Schematic diagram of scatterer nanostructures. d Zoomed-in scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the nanostructures of the fabricated lens. Photographs of the fabricated Golay6+1 metalens (e), the fabricated central aperture (f), and the fabricated effective aperture (g).

Next, we converted the phase values into the dimensions of the nanostructures and created the layout for fabrication accordingly. The metalenses are realized using an all-silicon platform, where silicon nanostructures are directly etched on a silicon wafer, for a simple fabrication process. To transform the phase information of the metalenses into nanopillars, we wrapped the phase information between 0 and 2π, discretized it, and selected corresponding nanostructures from a library of nanopillars simulated by RCWA36,37. This ensured that their transmission phase closely approximated the ideal hyperbolic focusing profile. To satisfy fabrication constraints, we chose a relatively large unit cell period of 5.6 μm and used nanopillars with a height of 7.9 μm. Figure 2c shows the schematic diagram of a single nanopillar and the relationship between its feature size, transmission phase, and transmittance. The nanopillars were uniformly arranged in rows and columns with a minimum spacing of 3.67 μm. Ultimately, the complete Golay6+1 metalens comprised approximately 45 million nanopillars, with each sub-aperture containing about 6.4 million nanopillars.

We fabricated MWIR metalenses on a 4-in. double polished silicon wafer, where we patterned using laser direct writing lithography and etched the patterns using deep reactive ion etching (details provided in the “Methods” section). The scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the fabricated metalenses are shown in Fig. 2d. The thickness of the fabricated metalenses is only about 300 μm. The photograph of the fabricated Golay6+1 metalens is shown in Fig. 2e while the center aperture and the effective aperture are presented in Fig. 2f, g, respectively. We will use all these samples to compare their performance.

Imaging

To evaluate the performance of the sparse aperture metalens, we imaged four targets: a wooden USAF target (100 × 100 mm), a wooden Siemens target (40 mm diameter), a wooden snowflake (85 mm max width), and a cross target (16 mm max width). These targets were placed in front of a hot plate, and the SNR was controlled by adjusting the hot plate’s temperature. A 4.25–4.75 μm narrowband filter was placed in front of the camera during the imaging of the targets. Additionally, we imaged a heater featuring dense patterns and stripes across the entire MWIR range, without using the narrowband filter. Our imaging tests were conducted at distances of 7.5, 15, and 30 m.

To enhance the clarity of the images captured by the sparse aperture system, we employed the HQS method with a dilated-residual U-Net (DRUNet) deep learning network to restore the images captured by the sparse aperture metalenses. This method, also known as plug-and-play image restoration with deep denoiser prior (DPIR)38,39,40,41,42,43 and detailed in the Supplementary Information, leverages the power of a discriminatively learned deep convolutional neural network (CNN) denoiser as a sophisticated image prior. The DRUNet denoiser exhibits state-of-the-art Gaussian denoising performance. This denoising model is seamlessly integrated into an iterative algorithm based on the HQS method, overcoming challenges associated with existing plug-and-play methods that struggle with deeper and larger CNN models. DPIR sets a benchmark in plug-and-play image restoration compared to both state-of-the-art model-based and learning-based methods.

Figure 3a shows the raw sensor measurement and the reconstructed images of the Siemens target being placed 7.5 m from the lens, captured by the Golay6+1 metalens. The raw sensor measurement image has an SNR of 13.6 dB. In comparison, the reconstructed image displays significantly reduced noise and sharper target edges and tips. Figure 3b compares the MTF extracted from both the denoised raw sensor measurement image and the reconstructed image for the Golay6 + 1, the center aperture and the effective aperture. Images from both the center aperture and effective aperture configurations are presented in Fig. S2a, b. The experimental MTF extraction method will be discussed in the Methods section. All configurations demonstrate significant MTF enhancement after reconstruction compared to raw sensor measurements, confirming the effectiveness of the image reconstruction process. Among these, the Golay6+1 metalens exhibits the broadest MTF profile. At an MTF threshold of 0.1, the Golay6+1 metalens achieves a cutoff frequency of 18.7 lp/mm, surpassing both the effective aperture (15.7 lp/mm) and center aperture (8.0 lp/mm). It also maintains higher contrast transfer across all spatial frequencies compared to the effective aperture and the center aperture. These comparisons demonstrate that the Golay6 + 1 metalens surpasses even the enhanced resolution of the effective aperture, which itself shows improvement over the center aperture. In addition, we imaged the Siemens target by blocking the central sub-aperture of the Golay6 + 1 metalens to emulate a Golay6 configuration, and its image appears inferior than that of the Golay6+1 metalens, as shown in Fig. S2c, d. These experiment results are consistent with the conclusions drawn from the simulation.

a Raw sensor measurement and reconstructed images of the Siemens star target 7.5 m away from the lens, taken by the Golay6 + 1 aperture. b Comparison of the extracted modulation transfer function (MTF) from the raw sensor measurement and reconstructed images of the Golay6 + 1 metalens, the central aperture, and the effective aperture. Raw sensor measurement (c) and reconstructed images (d) of the USAF resolution target 7.5 m away from the lens, taken by the Golay6 + 1 aperture. Cropped raw sensor measurement and reconstructed images of the wooden snowflake 7.5 m away from the lens, taken by the Golay6 + 1 aperture (e) and the effective aperture (f).

Figure 3c, d present the raw sensor measurement image (c) and the reconstructed image (d) of the USAF target at 7.5 m captured using the Golay6 + 1 metalens, successfully resolving the target’s Group 1 Element 4 with a minimum line width of 0.7 mm, which is close to the theoretical diffraction-limited resolution of 0.49 mm at this distance, despite the noise in the raw sensor measurement image affecting the resolution. Comparable images captured using the center aperture and the effective aperture are shown in Fig. S3c, d, f, g. The image captured by the center aperture demonstrates the lowest contrast and clarity, failing to resolve any elements in Group 1 of the USAF target. We further conducted a quantitative image comparison by calculating the structural similarity index (SSIM) of these images. The reference ground truth image was captured using a refractive MWIR lens (125 mm focal length) at 1 m distance, as this lens lacked sufficient magnification for clear imaging at our experimental distance of 7.5 m. The acquired image was subsequently cropped and upsampled to match the size in pixels of the USAF target images obtained through the metalens, with the processed ground truth shown in Fig. S3a. The Golay6 + 1 system showed significant improvement in image quality, with its reconstructed image achieving a 77% higher SSIM than the raw sensor measurement. Moreover, it outperformed the reconstructed image from the effective aperture system by 23% in SSIM. These results demonstrate both the effectiveness of our reconstruction algorithm and the superior imaging performance of the Golay6 + 1 configuration compared to a single aperture with equivalent light-collecting area.

We analyzed the intensity profiles of Group 1 (Elements 1–4) in the reconstructed USAF image from the Golay6 + 1 system, comparing vertical and horizontal orientations. The intensity profile images and their corresponding contrast values are shown in Fig. S3h. The calculated contrast ratio is defined as (Ipeak − Ivalley)/(Ipeak + Ivalley), where Ipeak represents the mean of three peak intensities and Ivalley denotes the mean of two valley intensities. While both vertical and horizontal orientations can resolve Group 1 Element 4, subtle contrast differences exist between them (vertically 0.1577 vs horizontally 0.1768), though these variations are not visually distinguishable in the image.

The wooden snowflake target, which has a maximum radius of 89 mm and is characterized by its 6-fold symmetry and varying features along the radius, was also imaged at a distance of 7.5 m from the metalens. To ensure the snowflake remained unaffected by the heat (maintaining high contrast in the captured images), we preheated the hot plate to a fixed temperature before placing the snowflake in front of it and quickly captured the images. The cropped raw sensor measurement and reconstructed images captured with the Golay6 + 1 and effective aperture are shown in Fig. 3e, f, respectively. We also performed quantitative analysis of the wooden snowflake images by calculating their SSIM values relative to the ground truth images, which were acquired and processed using the same methodology as for the USAF target images. The Golay6 + 1 system achieved 24% higher SSIM than the effective aperture and 78% improvement over raw sensor measurements.

To evaluate the spatial uniformity of our reconstruction algorithm, we analyzed the Golay6 + 1 imaging results of the snowflake target by dividing both pre- and post-reconstruction images into three concentric regions from center to edge, representing distinct field of view (FoV) regions. Quantitative assessment using SSIM metrics, calculated separately for each region against corresponding ground truth references, revealed consistent improvements throughout the FoV. Specifically, the reconstruction enhanced image quality by 0.24 SSIM in the innermost region (center), 0.23 in the middle region, and 0.16 in the outermost region. These quantitative improvements were corroborated by visual inspection of Fig. S4, where reconstructed images exhibited substantially enhanced clarity and sharpness compared to raw sensor measurements across all field positions.

To further demonstrate the imaging capability of our system at long distances, we imaged a heater in low radiation mode, as shown in the setup in Fig. 4a. The heater, located 15 m and even 30 m from the lens, has a diameter of 15 in. and features metal strips covered with black velvet on the exterior and polygon patterns on a curved aluminum plate inside, as shown in Fig. 4b, c. Infrared radiation is first emitted by the heater’s filament, and then reflected by the curved aluminum plate and transmitted out. Fig. S5 presents the heater images acquired at 30 m distance using the Golay6+1 metalens, demonstrating performance under both broadband (unfiltered under 3–5 μm MWIR spectrum, a–c) and narrowband (4.5 μm bandpass filtered, d–f) conditions. While the broadband images exhibit slightly lower contrast, our reconstruction algorithm successfully recovers spatial details to a level comparable to the narrowband results, with similar feature discernibility. Subsequent results focus on the broadband operation to illustrate the system’s functionality throughout the MWIR spectral range.

a Experimental setup for imaging the heater using the sparse aperture. b Photograph of the heater in low-radiation mode. c Photograph of the heater’s strips and internal textures. Image of the heater at 30 m taken by the Golay6 + 1 aperture without a narrowband filter, before (d) and after (e) reconstruction. Image of the heater at 15 m taken by the Golay6 + 1 aperture without a narrowband filter, before (f) and after (g) reconstruction. h Photograph of the cross target positioned in front of the hot plate. i Seven frames extracted from a video with timestamps, captured by the Golay6 + 1 system after reconstruction, illustrating the cross at various positions within the images. The corresponding field of view (FoV) of each cross center is indicated.

To characterize the heater under different thermal conditions, we captured images in three states: while the heater was on and stabilized, 30 s after it was turned off from the stabilized state, and 60 s after being turned off from the stabilized state, demonstrating different radiation intensities. Figure 4d, e compare the raw sensor measurement and the reconstructed images of the heater 30 m away, captured using the Golay6 + 1 metalens, while Fig. 4f, g provide the same comparison for the heater 15 m away. The effectiveness of image reconstruction is evident, as it makes the strips and textures clearly visible even at a distance of 30 m. Similar images obtained by the center aperture are shown in Fig. S6b for further comparison. At a distance of 30 m, the Golay6 + 1 metalens reveals detailed textures within the heater, whereas the center aperture shows less detail and lower contrast. This demonstrates the capability of our Golay6 + 1 metalens to image distant objects under the broadband thermal radiation across the entire MWIR spectrum, resolving intricate details of the heater compared to the center aperture. This difference becomes more pronounced when imaging the heater 30 s and 60 s after it has been turned off, as shown in Fig. S6c–f.

To verify whether our imaging system can produce clear images under camera motion, we inscribed a cross with both horizontal and vertical widths of 1 mm on a small piece of aluminum foil, and placed it in front of the hot plate 7.5 m away from the lens. The photo of the cross target is shown in Fig. 4h. Video capture was conducted using the Golay6 + 1 metalens. During the capture process, we randomly moved the cart holding the camera to ensure constant motion. Figure 4i displayed 7 frames extracted from the captured video, which are after reconstruction, with timestamps indicated at the bottom-right corner of each frame. These frames display the cross target at multiple field positions representing distinct FoV regions. In particular, one configuration places the cross at the extreme edge of the imaging range (0.486∘ FoV). Continuous camera motion during acquisition did not degrade image quality, as all targets, including this edge case, maintained sharp reconstruction fidelity. These observations collectively demonstrate the system’s motion tolerance and uniform performance throughout the operational FoV.

Towards a multi-wafer-based recursive sparse aperture metalens

Due to limitations in current single-wafer dimensions and the fabrication challenges of large-aperture metalenses, we provide a theoretical study of recursive sparse aperture designs to enable further scaling of the system. This approach facilitates significantly larger aperture sizes, which are essential for achieving longer focal lengths and enhanced long-range imaging capabilities. A 49-sub-aperture recursive (nearly 50 cm diameter) sparse aperture system was designed using seven discrete Golay aperture systems. Each wafer contains seven sub-apertures, each with a diameter of 16 mm, arranged in a Golay6 + 1 configuration with an outer diameter of 89 mm. These 7 wafers are also arranged in Golay6 + 1 configuration, resulting in a maximum circumscribing radius D of 495.1 mm, as shown in Fig. 5a, forming a recursive Golay6+1 metalens system in an F/4 configuration, with a resolution enhancement factor of 30.94 compared with a single sub-aperture with diameter of 16 mm. The simulated 2D MTF results presented in Fig. 5b, c demonstrate the performance comparison between the recursive Golay6 + 1 metalens and its effective aperture with matching light transmission area (112 mm diameter) at identical focal length. Figure 5d further illustrates their 1D MTF characteristics at λ = 4.5 μm, clearly showing the recursive Golay6 + 1 metalens achieves substantially better MTF coverage in high spatial frequency regions compared to its effective aperture. This performance advantage highlights the recursive Golay6 + 1 configuration in preserving fine spatial details. Calibration and alignment for the experimental demonstration of recursive Golay based systems are expected to be a significant and time-consuming engineering challenge, making it outside the scope of this paper, but we believe that it is an important and promising direction for future study. Here, we demonstrate the potential advantages of a recursive Golay configuration through physically realistic simulations.

a Aperture configuration of the recursive Golay6 + 1 metalens, showing seven Golay6 + 1 elements distributed on seven wafers. The sub-aperture diameter of a single element (d), as well as the sub-aperture diameter (D1) and outer diameter (D2) of the recursive Golay6+1 metalens, are indicated. Two-dimensional (2D) modulation transfer function (MTF) plots comparing the recursive Golay6 + 1 metalens (b) with its effective aperture sharing the same focal length (c). d Quantitative one-dimensional (1D) MTF comparison between the two configurations. Image simulation results featuring (e) the ground-truth Siemens star target, and reconstructed images from (f) the effective aperture and (g) the full recursive Golay6 + 1 metalens.

The image reconstruction performance was evaluated under noisy conditions where both systems processed input images degraded to 30.0 dB SNR through PSF convolution and additive Gaussian noise. The ground truth reference image is presented in Fig. 5e, while Fig. 5f, g demonstrate the reconstructed results, clearly showing the recursive Golay6 + 1 metalens achieves recovery of finer features than its effective aperture, particularly in resolving the delicate tips of the Siemens star target. This visual advantage is quantitatively confirmed by the recursive design’s higher reconstruction metrics (PSNR 18.00 dB, SSIM 0.93) compared to the effective aperture’s results (PSNR 14.56 dB, SSIM 0.84), demonstrating its enhanced robustness to noise-induced degradation.

Discussion

Obtaining larger aperture, high-quality metalenses for practical imaging applications remains challenging due to fabrication scaling limitations, stitching errors, and associated efficiency degradation. Particularly for infrared imaging, these constraints impose significant resolution limitations. In this work, we designed and fabricated the Golay sparse aperture metalens with an 89 mm outer diameter and 6 + 1 sub-apertures, operating in the MWIR, and demonstrated that it has achieved higher resolution compared to a single sub-aperture, both in simulations and imaging experiments.

By arranging sparse apertures in a non-redundant Golay configuration, we maximize spatial information content while overcoming the scaling challenges of conventional metalenses. Adding an additional central sub-aperture in the configuration serves as both a configuration reference and an MTF enhancement. Our Golay6 + 1 metalens demonstrates superior imaging performance with nearly uniform resolution in all directions. The scalable recursive Golay6 + 1 design achieves significantly larger apertures, enabling longer focal lengths and enhanced long-range imaging capabilities for future systems.

Image reconstruction is crucial in sparse-aperture metalens imaging systems. To significantly improve the captured image quality, particularly in resolution and MTF roll-off, we applied a reconstruction algorithm that integrates deep-learning-based denoising into a deconvolution process using the HQS method. Experimental results demonstrated that our reconstruction algorithm is highly effective, significantly reducing noise and producing clearer reconstructed images. While the current implementation delivers decent image quality and achieves near real-time performance on a single GPU, we acknowledge that true real-time operation (>30 fps) will be required for highly dynamic applications. Through multi-GPU parallelization and further algorithmic refinements, we expect to substantially improve processing speeds while maintaining reconstruction quality.

In summary, our experimentally demonstrated Golay6 + 1 metalens and the theoretically explored recursive Golay6 + 1 design, combined with an effective image reconstruction algorithm, provide a promising way to overcome the resolution limitations inherent in individual metalenses due to fabrication constraints. Specifically, our approach enables several orders of magnitude reduction in the imaging systems, and without using metasurface such reduction is not possible. In fact, our approach enables making an extremely large aperture metasurface, which was considered a big challenge. This development lays the foundation for the creation of lightweight, high-resolution MWIR long-range imaging systems. Future challenges include the precise alignment of individual metalenses as sub-apertures and improving the durability and preservation of the fragile metalenses.

Methods

Fabrication

Our metalenses were fabricated on a 300 μm thick, double-side polished silicon wafer. First, the area surrounding the sub-apertures was coated in a 200 nm thick Cr layer to act as an aperture, blocking illumination outside the sub-aperture metalenses. This helped to reduce noise in imaging experiments. In greater detail, the on-substrate apertures were formed by first writing the apertures in negative resist (NR9G-3000-PY) using direct-write lithography (Heidelberg DWL-66+). Then, the Cr layer was deposited on the photoresist using electron beam evaporation (CHA Solution) and subsequently lifted off in acetone to construct the metal mask around each sub-aperture. The result was bare silicon surface within each sub-aperture area. To pattern the meta-optics, the wafer was coated with positive photoresist (AZ1512) and exposed using direct-write lithography (Heidelberg DWL-66+) within the previously defined apertures. Finally, we used deep reactive ion etching (SPTS DRIE) to etch to a target depth of 7.9 μm using the photoresist as the etching mask. This formed the silicon pillars. Any residual photoresist was subsequently stripped using oxygen plasma.

Experiment setup

Our imaging setup consists of a MWIR Thermal Camera (FLIR A6700) equipped with lens tubes at the front to prevent heat disturbance and reflection to the camera sensor. The metalens wafer is mounted in a 4-in. mount (Thorlabs LMR4), with a flipper (Thorlabs MFF102) serving as a shutter for background correction positioned at the front. The lens mount is placed on an optical rail (Newport PRL-12) for precise distance adjustments to achieve a focused image. For narrowband measurements, we applied a bandpass filter (Thorlabs FB4500-500) with a center wavelength of 4.5 μm between the lens tubes and the camera. A photo of the setup, which shows each mentioned part, is provided in Fig. S8.

Experimental MTF calculation

In our analysis of the Siemens star target, we extract concentric circles centered at the target’s origin, each with varying radii. We then calculate the spatial frequency and corresponding contrast for each concentric circle to determine the system’s MTF. The process begins by defining a range of angles to compute the coordinates along each circle and identifying the nearest pixel values in the image. We convert the radius r of each circle into their respective spatial frequencies by using the relationship:

Subsequently, we extract pixel values along the specified circles in the image and apply a smoothing filter to reduce noise. We identify the extrema in the smoothed data and calculate the contrast modulation M using the formula:

where Imax and Imin represent the mean of the local maxima and minima of the signal, respectively. Finally, we plot the spatial frequencies against their corresponding contrast modulation values to visualize the system’s MTF, thereby characterizing the imaging performance across different spatial frequencies.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main manuscript and in the Supplementary Information. Additional data are provided in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code supporting this study is available on GitHub: https://github.com/wj-2000/golay_simul.

References

Deng, X. et al. A compact mid-wave infrared imager system with real-time target detection and tracking. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 15, 6069–6085 (2022).

LeMaster, D., Karch, B. & Javidi, B. Mid-wave infrared 3D integral imaging at long range. J. Disp. Technol. 9, 545–551 (2013).

Orton, G. S. & Yanamandra-Fisher, P. A. Saturn’s temperature field from high-resolution middle-infrared imaging. Science 307, 696–698 (2005).

Banerji, S. et al. Imaging with flat optics: metalenses or diffractive lenses. Optica 6, 805–810 (2019).

Khorasaninejad, M. et al. Metalenses at visible wavelengths: diffraction-limited focusing and subwavelength resolution imaging. Science 352, 1190–1194 (2016).

Arbabi, A. & Faraon, A. Advances in optical metalenses. Nat. Photonics 17, 16–25 (2023).

Xiong, B. et al. Breaking the limitation of polarization multiplexing in optical metasurfaces with engineered noise. Science 379, 294–299 (2023).

Dorrah, A. H. & Capasso, F. Tunable structured light with flat optics. Science 376, eabi6860 (2022).

Li, L. et al. Metalens-array-based high-dimensional and multiphoton quantum source. Science 368, 1487–1490 (2020).

Wang, S. et al. A broadband achromatic metalens in the visible. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 227–232 (2018).

Colburn, S. & Majumdar, A. Metasurface generation of paired accelerating and rotating optical beams for passive ranging and scene reconstruction. ACS Photonics 7, 1529–1536 (2020).

Fröch, J. E. et al. Beating spectral bandwidth limits for large aperture broadband nano-optics. Nat. Commun. 16, 3025 (2025).

Leng, B., Zhang, Y., Tsai, D. & Xiao, S. Meta-device: advanced manufacturing. Light. Adv. Manuf. 5, 5 (2024).

Wirth-Singh, A. et al. Wide field of view large aperture meta-doublet eyepiece. Light Sci. Appl. 14, 17 (2025).

Zhang, L. et al. High-efficiency, 80 mm aperture metalens telescope. Nano Lett. 23, 51–57 (2023).

Park, J. S. et al. All-glass 100 mm diameter visible metalens for imaging the cosmos. ACS Nano 18, 3187–3198 (2024).

Hou, M. M., Chen, Y., Li, J. Y. & Yi, F. Single 5-centimeter-aperture metalens enabled intelligent lightweight mid-infrared thermographic camera. Sci. Adv. 10, eado4847 (2024).

Kim, J. et al. Scalable manufacturing of high-index atomic layer-polymer hybrid metasurfaces for metaphotonics in the visible. Nat. Mater. 22, 474–481 (2023).

Saragadam, V. et al. Foveated thermal computational imaging prototype using all-silicon meta-optics. Optica 11, 18–25 (2024).

Wootten, A. & Thompson, A. R. Atacama large millimeter/submillimeter array. Proc. IEEE 97, 1463–1471 (2009).

Miller, N. J., Dierking, M. P. & Duncan, B. D. Optical sparse aperture imaging. Appl. Opt. 46, 5933–5943 (2007).

Liu, T. C. et al. Large effective aperture metalens based on optical sparse aperture system. Chin. Opt. Lett. 18, 100001 (2020).

Hu, J. et al. Polarization-insensitive, orthogonal linearly polarized and orthogonal circularly polarized sparse aperture Metalenses. Photonics 10, 348 (2023).

Zhao, F. et al. Sparse aperture metalens. Photon. Res. 9, 2388–2397 (2021).

Lin, Y. et al. High-efficiency optical sparse aperture metalens based on GaN nanobrick array. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2102756 (2022).

Dong, Y. G. et al. An unconventional optical sparse aperture metalens. AIP Adv. 12, 055009 (2022).

Dong, Y. G. et al. Lossless imaging based on a donut-like optical sparse aperture metalens. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 191701 (2023).

Johansen, V. et al. Nanoscale precision brings experimental metalens efficiencies on par with theoretical promises. Commun. Phys. 7, 123 (2024).

Jin, L. et al. Deep learning extended depth-of-field microscope for fast and slide-free histology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 33051–33060 (2020).

Hui, M. et al. Image restoration for synthetic aperture systems with a non-blind deconvolution algorithm via a deep convolutional neural network. Opt. Express 28, 9929–9943 (2020).

Wu, J., Boominathan, V., Veeraraghavan, A. & Robinson, J. Real-time, deep-learning aided lensless microscope. Biomed. Opt. Express 14, 4037–4051 (2023).

Hui, M. et al. Image restoration for optical synthetic aperture system via patched maximum-minimum intensity prior and unsupervised DenoiseNet. Opt. Commun. 527, 128961 (2023).

Golay, M. J. E. Point arrays having compact, nonredundant autocorrelations. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 61, 272–273 (1971).

Goodman, W. Introduction to Fourier Optics (McGraw-Hill, 1996).

Aieta, F. et al. Aberration-free ultrathin flat lenses and axicons at telecom wavelengths based on plasmonic metasurfaces. Nano Lett. 12, 4932–4936 (2012).

Liu, V. & Fan, S. H. A free electromagnetic solver for layered periodic structures. Comput. Phys. Commun. 183, 2233–2244 (2012).

Colburn, S. & Majumdar, A. Inverse design and flexible parameterization of meta-optics using algorithmic differentiation. Commun. Phys. 4, 65 (2021).

Zhang, K. et al. Plug-and-play image restoration with deep denoiser prior. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44, 6360–6376 (2022).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (San Diego, 2015).

Chen, Y. & Pock, T. Trainable nonlinear reaction diffusion: a flexible framework for fast and effective image restoration. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 39, 1256–1272 (2016).

Ma, K. et al. Waterloo exploration database: new challenges for image quality assessment models. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 26, 1004–1016 (2017).

Agustsson, E., Timofte, R. NTIRE 2017 challenge on single image super-resolution: dataset and study. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops 3, 126–135 https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPRW.2017.150 (2017).

Lim, B., Son, S., Kim, H., Nah, S., Mu Lee, K. Enhanced deep residual networks for single image super-resolution. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops 136–144 https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPRW.2017.151 (2017).

Acknowledgements

A.V. and J.W. acknowledge funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF, grant No. IIS-2107313). A.M., A.W.S., and R.J. are supported by DoD-STTR grants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.V., A.M, V.S., and J.W. conceived the idea. J.W. developed the Golay metalens design pipeline. A.W.S. fabricated all the devices and conducted initial experimental testing. J.W. performed all imaging experiments reported in the manuscript and carried out image post-processing using the reconstruction algorithm. V.S. assisted with the experimental setup. R.J. contributed to device fabrication and acquired the SEM image. J.W. contributed to manuscript writing, and all authors helped refine the manuscript and provided feedback during the rebuttal. A.V. and A.M. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Wirth-Singh, A., Saragadam, V. et al. A golay metalens for long-range, large aperture, thermal imaging via sparse aperture computational imaging. Nat Commun 16, 10281 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65188-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65188-y