Abstract

Strigolactones (SLs) are pivotal plant hormones involved in developmental, physiological, and adaptive processes. SLs also facilitate symbiosis with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and trigger germination of root parasitic Striga plants. The carboxylesterase CXE15, recently identified as the SL catabolic enzyme in Arabidopsis thaliana, plays a crucial role in regulating SL levels. Our study elucidates the structural and regulatory mechanisms of CXE15. We present four crystal structures capturing the conformational dynamics of CXE15, revealing a unique N-terminal extension (Nt) that transitions from a β-sheet in monomers to an intertwined helical structure in dimers. Only the dimeric form is catalytically active, as it forms a hydrophobic cavity for SLs between its two active sites. The moderate dimerisation affinity allows for genetic regulation through protein expression levels. Additionally, we identify an environment-controlled regulation mechanism. Under oxidising conditions, a disulphide bond forms between Cys14 of the two monomers, blocking the active site and inhibiting SL cleavage. This redox-sensitive inhibition of SL catabolism, triggered by reactive oxygen species (ROS) in response to abiotic stress, suggests a mechanism for maintaining high SL levels under beneficial conditions. Our findings provide molecular insights into the regulation of SL homeostasis and catabolism under stress conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Strigolactones (SLs) are phytohormones fulfilling different functions within plants, but also released by roots into the soil for rhizospheric communications1,2. As an inhibitor of shoot branching, SLs are a major determinant of plant architecture1,2. They also regulate further developmental, physiological, and adaptive processes1,2,3. Additionally, SLs exuded into the soil act as signals for establishing mutualistic associations with arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi that provide water, phosphate (Pi), and other soil nutrients to plants4. The need for SLs for recruiting AM fungi and for architectural adjustments under phosphate deficiency explains why SL biosynthesis and release are significantly enhanced under nutrient limitation5. However, exuded SLs have been co-opted by root parasitic plants, such as Striga hermonthica, which perceive them as germination signals, coordinating their life cycle with that of host plants and ensuring their availability2,6. These weeds are a severe problem for agriculture in warm and temperate regions and represent one of the major threats to global food security7.

Structurally, natural SLs are defined as carotenoid derivatives that contain a butenolide ring (D-ring) as a characteristic chemical structure. This D-ring is linked by an enol ether bridge to a tricyclic lactone (ABC-ring) in canonical SLs or to a different moiety in non-canonical SLs7,8. Both SL classes originate from β-carotene through a well-established pathway that includes isomerisation and subsequent oxidative cleavage and intramolecular rearrangements. Catalysed by the enzymes DWARF27 (D27), carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 7 and 8 (CCD7 and 8), these reactions occur in the plastid and lead to the central intermediate carlactone, a 19-carbon metabolite containing the D-ring moiety. Once exported into the cytosol, various enzymatic modifications, such as oxygenation and methylation, convert carlactone into different SLs2,9,10.

SLs are perceived by DWARF14 (D14), a member of the α/β hydrolase (ABH) superfamily11. D14 binds SLs in a deep pocket and uses its weak hydrolysis activity to cleave and retain the D-ring11,12,13. SL binding and hydrolysis also promote the structural rearrangements required for D14 to serve as an adaptor between the F-box protein MORE AXILLARY GROWTH 2 (MAX2), a part of a Skp1-Cullin-F-box (SCF)–type E3 ligase, and its targets the Suppressor of MORE AXILLARY GROWTH1-like (SMAX1-like) transcriptional repressors (SMXL6, SMXL7, SMXL8)/DWARF53 (D53)14,15,16,17,18. Thus, D14 functions as both a receptor and hydrolase. However, perception-coupled SL degradation by D14 is too slow to be an efficient means to regulate SL abundance. SL catabolism was shown to rely on another enzyme, the recently identified carboxylesterase CXE15 in Arabidopsis, which belongs to an evolutionary conserved clade19. CXE15 is predicted to be an ABH enzyme, like D14, suggesting that the mode of action of both may be similar5,20,21,22. Indeed, CXE15 and D14 catalyse the same reaction, namely cleavage of the enol-ether between the D-ring and the rest of the SL molecule19,23,24. However, the regulation of CXE15 remains largely elusive, despite the elucidation of the first CXE15 crystal structure25.

We combined structural, biochemical, and physiological analyses to shed light on the catalytic mechanism of CXE15. By determining four crystal structures representing CXE15 in different structural states, combined with in vitro assays and in planta experiments, we demonstrate that CXE15 is a hydrolase that functions as a dimer, the enzymatic activity of which can be inhibited by an internal disulphide bridge formed under oxidising conditions. This mechanism ensures that this degrading enzyme is not active under Pi starvation, which causes the formation of ROS and promotes the biosynthesis of SLs needed for architectural adaptation and AM symbiosis26. Our work demonstrates how the evolution of a specific Nt allows an ABH carboxylesterase to catabolise the large plant hormone SL and unveils how the hydrolysis activity is regulated to adjust SL levels to meet the plant’s demand.

Results

CXE15 crystallises in both monomeric and dimeric forms with different N-terminal conformations

We crystallised full-length Arabidopsis thaliana CXE15 (CXE15) in two different space groups and determined four distinct crystal structures (Supplementary Table 1). All structures shared a conserved catalytic core (residues 45–329), which adopts a canonical α/β-hydrolase fold characterised by a central β-sheet formed by eight β strands, connected by linkers containing one or two helices (Fig. 1). However, the conformation of the N-terminal extension (Nt; residues 9–44) and the oligomeric state varied between space groups.

A The monomeric crystal structure of CXE15 (black) superimposed on a single chain of its dimeric form (core: green; N-terminal extension: grey). Catalytic residues are highlighted in magenta and encircled. Cys14 is shown in orange. B The dimeric form of CXE15. The first molecule is coloured as in (A), and the second molecule is in dark green with its N-terminal extension in black. The catalytic residues on one chain are shown in magenta and encircled. C Superimposition of the N-terminal helices of the CXE15 dimer (grey) over the helices of the CXE15 C14S mutant (cyan). Both Cys14 involved in disulphide bond formation are depicted as orange sticks with a prime (‘) denoting the second chain. D Superimposition of the CXE15 monomer (green, from the dimeric form) with rice D14 (PDB: 6elx, light brown). E A zoomed-in view of the superimposed catalytic sites shown in (D). F GR24 (cyan sticks) docked to the CXE15 dimeric structure [coloured as in (B)]. Residues interacting with GR24 are shown as sticks.

The first structure, determined at 3.1 Å resolution in space group P3₂21, contained two CXE15 molecules in the asymmetric unit. However, the total buried interface between the two molecules was relatively small (1070 Å2) and predicted to be unstable in solution based on PDBePISA analysis (ΔG = −4.5 kcal/mol; CSS score = 0), indicating that this represents a monomeric form. Residues 11–28 of the Nt form an additional β-sheet consisting of three antiparallel strands (Fig. 1A). The residues connecting the Nt β-sheet to the core domain were not resolved in the electron density, indicating conformational flexibility. This P3₂21 crystal structure, including the Nt β-sheet, closely matched the AlphaFold prediction (AF-Q9FG13-F1; RMSD = 0.41 Å; Supplementary Fig. 1A). The combined architecture of the catalytic core and Nt β-sheet also showed strong structural similarity to known proteins in the PDB, such as 2-hydroxyisoflavanone dehydratase from Pueraria lobata (PDB ID: 8ea2; Foldseek E-value: 5.5e − 26) and tabersonine synthase from Catharanthus roseus (PDB ID: 6rs4; E-value: 5.6e − 23) (Supplementary Fig. 1B).

A second crystal structure of CXE15, resolved at 2.05 Å in space group P4₁2₁2, included residues 9–329 and contained a single molecule in the asymmetric unit. While the catalytic core was unchanged compared to the P3₂21 structure (RMSD = 0.42 Å), the Nt adopted a markedly different conformation. Instead of forming a β-sheet, residues 9–22 folded into an α-helix (Fig. 1A). However, both the β-sheet (in the P3₂21 monomeric form) and the helix (in this P4₁2₁2 structure) interacted with a similar region of the core domain located at the entrance to the active site (F89, P121, L225, K228, F229, R231, and L232).

In the P4₁2₁2 crystal form, the loop connecting the N-terminal helix to the core domain was well resolved in the electron density, revealing that the Nts of two adjacent molecules in the crystal lattice were intertwined (Fig. 1B). This interaction buried 2994 Å2 of solvent-accessible surface area and formed a stable dimer interface, as predicted by PDBePISA (ΔG = −39.6 kcal/mol; CSS score = 0.87). The closest (monomeric) structural match to this fold, including the Nt helix, was the rice gibberellin receptor GID1 (PDB ID: 3ED1; E-value: 6.5e − 27). However, GID1’s Nt helix differed in structure and did not mediate dimerisation, highlighting the CXE15 dimer as an unusual variation of the carboxylesterase fold (Supplementary Fig. 1C).

In this P4₁2₁2 crystal form, the two CXE15 chains were covalently linked via a disulphide bond between their Cys14 residues, located on the second turn of the Nt helix (Fig. 1B, C). To assess the structural role of this disulphide bond, we crystallised the C14S mutant and determined its structure at 2.75 Å resolution. Like the wild-type (WT), the C14S mutant crystallised in space group P4₁2₁2 and adopted the same overall dimeric arrangement. However, the Nt helix was shortened, comprising only residues 17–22, and Ser14 was located in a flexible, unresolved loop region (Fig. 1C).

Finally, we produced the 2.55 Å structure of the E271Q mutant, previously shown to be catalytically inactive by Xu et al.21. The E271Q mutant also crystallised in P4₁2₁2. It was structurally identical to the dimeric WT form (RMSD of 0.18 Å), and retained the disulphide bond between the two Cys14 residues (Supplementary Fig. 1D). The E271Q variant was intended to facilitate substrate capture in the crystal for structural analysis. Despite extensive soaking and co-crystallisation trials with SLs, we did not observe any electron density that could be confidently attributed to SLs or their degradation products. However, all structures exhibited residual electron density adjacent to the catalytic Ser169, corresponding to an unidentified compound. Neither the SL D-ring, nor common D14/HTL-associated ligands—such as MPD, glycerol, DMSO, or metal ions—fitted this density unambiguously, and mass spectrometry confirmed the absence of covalent additions for CXE15 (Supplementary Fig. 1E).

CXE15 structures reveal key discrepancies to previously published models

During the preparation of this manuscript, Palayam et al. published two structures of A. thaliana CXE15 (PDB accessions 8VCA and 8VCD)25. These structures crystallised in the same P4₁2₁2 space group, with nearly identical unit cell parameters as our dimeric CXE15 structures (8ZRF, 8ZRG, 8ZR6). Although the catalytic cores were nearly identical, the structures derived from these data show critical differences.

First, the Nt regions and their connections to the catalytic core were modelled differently. In both 8VCA and 8VCD, the Nt was modeled in a cis configuration, consistent with a monomeric form of CXE1525. This configuration obscures the dimeric architecture that becomes evident when the Nt is modeled in trans, as in our structures. Inspection of the deposited diffraction data from 8VCA and 8VCD revealed strong omit electron density at a 1σ cutoff, clearly consistent with the in trans configuration. This reanalysis strongly supported that the crystals by Palayam et al. also contained the arm-exchange dimer (Supplementary Fig. 2A).

Second, the structures of Palayam et al. lacked the inter-chain disulphide bond between Cys14 residues, which stabilises the dimeric form in our WT and E271Q models. However, the Fo–Fc (3σ) and 2Fo–Fc (1σ) maps of 8VCA and 8VCD showed strong electron density between adjacent Cys14 residues, indicating that this disulphide bond was also present in their crystallographic data (Supplementary Fig. 2B, C).

Third, Palayam et al. interpreted residual electron density adjacent to the catalytic Ser169 in their GR24-soaked structure (8VCD) as a covalently bound hydrolysed lactone D-ring of rac-GR2425. To test whether this interpretation could explain the residual electron density in our crystallographic data, we attempted to model the same intermediate into our own GR24-soaked structures. However, the fit was poor, and mass spectrometry analysis of GR24-incubated protein did not detect any covalent modification of Ser169 (Supplementary Fig. 1E), suggesting that the residual density in our structures corresponds to a different (non-covalently bound) molecule. Notably, a strong negative Fo–Fc difference map in the 8VCD data also challenges the covalently bound D-ring assignment by Palayam et al. Instead, we found that a DMSO molecule provides a significantly better fit of the crystallographic data (Supplementary Fig. 2D, E), consistent with the absence of covalent modification in the mass spectrometry data reported by Palayam et al.25. Taken together, these discrepancies in structural interpretation help explain why Palayam et al. did not identify the disulphide-stabilised dimeric form of CXE15 in their data.

Dimerisation produces a joint active site required to accommodate SL for catalysis

CXE15 is the only enzyme in the CXE family with a glutamic acid in the catalytic triad, instead of the aspartic acid typical for plant CXEs21. Our structures confirmed the catalytic triad as Ser169/Glu271/His302, suggested previously21,25. The position of this triad within the CXE15 α/β-hydrolase fold corresponds to the Ser/Asp/His catalytic triad in D14 and its homologues KAI2 and HTL (Fig. 1D), explaining how CXE15 can perform the same SL cleavage reaction as D14. However, the structural extensions of the core hydrolase fold differ substantially between D14 and CXE15, resulting in a very differently configured ligand binding site (Fig. 1D, E). Thus, CXE15 and D14 present evolutionary different α/β-hydrolase lineages that developed the ability to cleave SLs.

In the monomeric AlphaFold structure prediction, the CXE15 catalytic site is partly occluded by Nt residues 28–40 (Supplementary Fig. 1A). In the monomeric crystal structure, electron density for this Nt region is mostly absent, suggesting high flexibility. Intriguingly, the catalytic site entrance is obstructed by the N-terminal helix in the interlaced and C14 disulphide–bonded dimeric structures. Due to the shortening of the Nt helix, this occlusion is reduced in the C14S mutant (Fig. 1C). We computationally docked the SL analog GR24 into the active site of the structural models to probe the effects of CXE15 dimerisation on catalysis (Fig. 1F). GR24 docking into the crystallographic monomeric form, where the Nt loop residues 28-40 were flexible and not modelled, showed that the catalytic site is too shallow to engulf GR24, leaving much of the hydrophobic A/B rings exposed to the solvent (Supplementary Fig. 3A). In the monomeric AlphaFold model, where the active site is mostly covered by residues 28–40, the resulting catalytic cavity was too small to accommodate GR24 in its natural linear form (Supplementary Fig. 3B). Hence, monomeric CXE15 appeared unable to capture the SL substrate. Conversely, GR24 fitted well in the hydrophobic cavity that dimeric CXE15 forms between both catalytic sites (Fig. 1F, Supplementary Fig. 3C, D). However, only one GR24 molecule can be accommodated by this combined cavity at a time. Importantly, entry of GR24 into the active site would require the opening of the Nt helix. This movement is precluded by the disulphide bond formed between the two C14 residues of the dimer.

To further investigate the structure–function relationship of residues implicated in CXE15 dimerisation and catalytic activity, we performed 500 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulations on several CXE15 constructs. The constructs included WT CXE15 in both dimeric and monomeric forms bound to GR24, the WT dimer in its apo form, the dimeric C14S mutant bound to GR24, and a nona mutant featuring nine substitutions in the flexible Nt region (D13R, L17R, L18R, L21R in the Nt helix, and E30R, I32R, D33R, I35R, and K42D in the helix–core linker; see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 4). Analysis of RMSD and root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) profiles revealed that GR24 binding stabilises the protein compared to its apo form. The C14S mutation had a mildly destabilising effect. Notably, both the monomeric WT and the nona mutant exhibited significantly reduced structural stability relative to the dimer, particularly within the first 30 N-terminal residues (Fig. 2A–C, Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6).

A Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis of residues 9–40 from CXE15 using molecular dynamics simulations for the monomeric and dimeric forms, along with their respective mutants. B Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) profiles of CXE15 residues calculated from molecular dynamics simulations for the monomeric and dimeric forms, including their respective mutants. C RMSD and RMSF values for the CXE15 monomer, dimer and its mutants. Data are expressed as mean values ± SEM. The data shown in panels A, B were repeated three times independently. D MST curve for dimerisation of CXE15 or the CXE15 C14S mutant in the presence and absence of GR24. The Kd values are given in square brackets and the data are presented as mean values ± SEM from three independent replicates. E Yeast two-hybrid screening to identify binding partners of CXE15 and its mutants (n = 1). F YLG hydrolysis activity of CXE15 and its dimer mutants. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM from three independent replicates. G Non-reducing SDS-PAGE gel for CXE15 and the CXE15 C14S mutant treated with H₂O₂ in the presence and absence of DTT. Samples represent SEC fractions as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7B. The experiments were repeated three times independently.

Together, these findings support a model in which the ability to hydrolyse SLs evolved independently in CXE15 and the D14/HTL/KAI2 family through distinct adaptations of the carboxylesterase fold. In CXE15, this adaptation involved the emergence of a unique N-terminal extension that enables the protein to exist in both monomeric and dimeric states. Dimerisation is essential for catalysis, as it creates a structural configuration capable of accommodating the large, hydrophobic SL molecule within the joint carboxylesterase active sites. Under oxidative conditions, a disulphide bond between C14 residues occludes the active site in the dimer, thereby preventing substrate access.

CXE15 dimerisation and catalytic activity depend on Nt residues

We next assessed the predictions from our structural analysis in vitro. Microscale thermophoresis (MST) on recombinant, purified CXE15 under reducing conditions confirmed that the protein self-associates with a dissociation constant (Kd) of 1.62 ± 0.39 µM (Fig. 2D). The C14S mutant still dimerised, but with a slightly reduced affinity (Kd = 4.5 ± 1.0 µM). The addition of 100 µM GR24 marginally enhanced self-association to a Kd of approximately 1 µM for both WT and C14S variants.

To further dissect the role of the N-terminus (Nt) in dimer stabilisation, we generated and tested several disruptive point mutants. These included F89R and W94R, targeting hydrophobic residues at the dimer and substrate interface; a triple mutant (L17R, L18R, L21R) affecting residues in the Nt helix near C14; and a nona mutant additionally targeting residues in the linker between the Nt helix and the protein core. All these mutations impaired CXE15 dimerisation (Supplementary Fig. 7A). Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assays corroborated these findings: the triple and nona mutants, as well as the Nt deletion mutant (CXE15∆40), failed to self-associate. The F89R and W94R single mutants retained only residual interaction capacity (Fig. 2E).

These results highlighted the critical role of hydrophobic residues in the Nt helix and ligand-binding cavity in stabilising CXE15 dimers. While residues in the flexible Nt linker may contribute additional stabilisation, the minimal difference between the triple and nona mutants suggests that disruption of the Nt helix alone is sufficient to abrogate dimerisation.

Catalytic activity, assessed via Yoshimulactone Green (YLG) hydrolysis assays, further supported the functional importance of dimerisation. Mutants that disrupted dimer formation also exhibited markedly reduced catalytic activity, underscoring the essential role of dimerisation in CXE15 enzymatic function (Fig. 2F).

The dimeric form is covalently stabilised under oxidative conditions

In size exclusion chromatography coupled to multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) CXE15 eluted as a monomer (calculated and SEC-MALS molecular weights Mw were 36.7 and 37.6 ± 0.3 kDa, respectively) under reducing buffer conditions, as expected from the micromolar Kd observed in MST (Supplementary Fig. 7B). However, prior exposure to 10 mM H2O2 produced a strong peak for a dimeric species (calculated and measured Mw were 73.5 and 75.1 ± 0.5 kDa, respectively). Conversely, the CXE15 C14S mutant remained monomeric regardless of H2O2 treatment, supporting that disulphide bonding of C14 was responsible for stabilising the dimers under oxidising conditions (Supplementary Fig. 7B). Non-reducing SDS PAGE gel analysis confirmed that purified CXE15 forms covalently linked dimers after treatment with 10 mM H2O2 (Fig. 2G, Supplementary Fig. 7C). In the absence of H2O2 treatment or upon H2O2 treatment followed by adding a reducing agent (10 mM DTT), CXE15 migrated only as a monomer. In further support of the role of C14, the CXE15 C14S mutant did not form covalent dimers after being subjected to oxidising conditions (Fig. 2G).

SEC-linked small angle X-ray scattering (SEC-SAXS) data collected for H2O2-treated CXE15 yielded two peaks (radius of gyration Rg of approximately 31 Å and 22 Å). The C14-linked dimeric crystallographic model fitted the SEC-SAXS data for the large species (χ2 = 0.78), whereas the monomer with the Nt β-sheet fitted the scattering pattern of the smaller species (χ2 = 0.95) (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Fig. 7D, E, and Supplementary Table 2). Thus, SEC-SAXS supported the presence of the crystallographic monomer and dimer in vitro.

A Fit of the SAXS experimental data (blue dots) for monomeric (left) and dimeric (right) peak fractions with the scattering pattern calculated for the monomeric (red) and dimeric (green) structural models shown below. Particle parameters from the SAXS data are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7E. B Thermal melting curve for CXE15 and the CXE15 C14S mutant treated with H2O2 in the presence and absence of DTT. The experiments were repeated three times independently. C YLG hydrolysis activity of CXE15 and its mutants. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM from three independent replicates. D Thermal melting curve for CXE15 and the CXE15 C14S mutant in the presence and absence of GR24. The experiments were repeated three times independently.

Differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) of proteins at a 10 µM concentration revealed that the H2O2-promoted and SEC-purified CXE15 dimer has a 3.5 °C higher thermal melting temperature Tm than the monomeric form (Tm of 42.5 ± 0.5 vs 46 ± 0.7 °C, respectively). Adding 5 mM DTT to the H2O2-treated CXE15 resulted in a species with the Tm of the untreated monomer. The C14S mutant did not decrease the Tm (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Table 3). The CXE15 mutant lacking residues 1–40 (CXE15∆40) of the Nt had a 2.5 °C lower Tm, compared to the wild type, supporting the role of the Nt in stabilising the catalytic core domain. Collectively, these results confirm the presence of monomeric and C14-linked dimeric CXE15 species in vitro.

Disulphide-bond cross-linking of CXE15 dimers inhibits catalysis

Only the glutamic acid and serine within the presumed CXE15 catalytic triad had been previously confirmed, based on mutational analysis21,25. To complete this characterisation, we used in vitro enzymatic assays to also confirm the histidine within the catalytic triad inferred from structural analysis. Following incubation with 10 µM CXE15, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis showed the disappearance of the peak corresponding to the substrate GR24 and the formation of the product, as a result of GR24 hydrolysis. In contrast, the active site mutants S169A or H302A did not show hydrolysis activity, confirming H302 as catalytic residue (Supplementary Fig. 8A–C). YLG assays further confirmed catalytic activity of CXE15, but not of the S169A or H302A mutants (Fig. 3C). These results fully confirm the catalytic triad of CXE15, and hence that the spatial disposition of the active site residues in CXE15 within the α/β-hydrolase core is the same as for D14/HTL/KAI2 proteins.

In D14/HTL proteins, SL binding has been shown to reduce the melting temperature Tm, likely due to induced structural flexibility, whereas non-hydrolysable ligands increase the Tm27. In contrast, the addition of 50 or 100 µM of the SL analog GR24 did not significantly alter the Tm of either WT CXE15 or the C14S mutant (Fig. 3D), suggesting rapid substrate turnover and/or limited conformational changes upon SL binding or hydrolysis.

The YLG assay, performed at 3 µM protein concentration, further demonstrated that the purified H2O2-treated CXE15 dimer was not catalytically active. Catalysis was restored under reducing conditions (10 mM DTT) that were strong enough to break the C14 disulphide bond (Fig. 3C). The CXE15 C14S mutant remained catalytically active even after oxidative treatment, consistent with its capability to form dimers (albeit with reduced affinity) that cannot be cross-linked by cysteines. Additionally, the truncated variant CXE15∆40 was catalytically inactive, supporting the essential role of the N-terminus in dimerisation and active site formation.

These findings were confirmed by LC-MS analysis. Whereas non-oxidised CXE15 degraded all GR24, neither CXE15 from the H2O2-treated dimer fractions nor CXE15∆40 degraded GR24 (Fig. 4A). Conversely, the C14S did not significantly affect the enzymatic activity in the LC-MS analysis. This assay was carried out at protein concentrations (10 µM) above the dimerisation kd, hence still allowing for the formation of CXE15 C14S dimers (Fig. 4B). As an additional control, we produced and tested the C14D mutant, aimed at introducing charge-charge repulsion at this position. This mutant degraded GR24 similarly to the C14S mutant.

A LC-MS elution profiles for GR24 incubated with CXE15 taken from SEC nonoxidised or oxidised fractions, and Δ40 mutant. B LC-MS elution profiles for GR24 incubated with CXE15, C14S, and C14D mutants. C Redox-dependent YLG hydrolysis activity of oxidised CXE15. The activity of oxidised CXE15 was measured using YLG as a substrate under varying redox conditions, achieved by adjusting the ratio of oxidised (DTTox) to reduced (DTTred) dithiothreitol while keeping total DTT constant. Fluorescence from the hydrolysis product was used to quantify enzyme activity. Data represent mean ± SEM from three independent replicates.

To investigate the redox regulation of CXE15, we determined the redox potential of the C14 disulphide bond using a DTTred/DTTox redox couple. A titration curve plotting catalytic activity of oxidised CXE15 against the redox potential of the DTT couple28,29,30, yielded a midpoint potential, Em, of −332 ± 4 mV at pH 7.0 (Fig. 4C). This relatively low redox potential suggests that the C14 disulphide bond remains predominantly reduced under typical cytosolic conditions, becoming oxidised only in more oxidative environments. These findings support a regulatory role for C14 oxidation in modulating CXE15 activity in response to cellular redox status.

CXE15 forms dimers in planta

To investigate the presence of CXE15 dimers in planta, we transiently expressed CXE15 fused to split YFP in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves, using Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. We observed a strong Bimolecular fluorescence complementation assay (BiFC) fluorescent signal for YFP-CXE15, suggesting the formation of dimers in plant cells. The C14S or C14D mutations reduced the BIFC fluorescence more than twofold, consistent with the reduced self-association affinity of these mutants (Fig. 5A, B). These observations supported the presence of CXE15 dimers in N. benthamiana leaves and the role of the N-terminal extension for stabilising these dimers in planta.

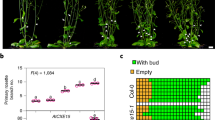

A BiFC fluorescence of CXE15, C14S, and C14D mutants in N. benthamiana. Scale bars: 20 µm. B Corrected total fluorescence from (A). Data represent mean ± SD from three independent replicates, asterisks indicate statistically significant differences as compared to control by one way ANOVA (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). C Phenotype of Arabidopsis Col-0, CXE15-OE-1, and CXE15-OE-8 lines. D Phenotype quantification of axillary buds treated with methyl viologen; n ≥ 6. Data represent mean ± SD from independent replicates, asterisks indicate statistically significant differences as compared to control by two way ANOVA (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). E Methyl carlactonoate (MeCLA) content in Col-0 and CXE15-OE-8 lines treated with methyl viologen; Data represent mean ± SD from three independent replicates, asterisks indicate statistically significant differences as compared to control by the two tailed unpaired Student t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001).

ROS blocks SL degradation in Arabidopsis

Our analysis suggests that disulphide bonding of the Nt within the CXE15 dimers halts SL catabolism. To test this hypothesis in planta, we generated CXE15-overexpressing Arabidopsis lines and phenotyped them in comparison with wild-type (Col-0) and the SL-deficient max3 mutant, which is incapable of synthesising SLs. Compared to wild-type (Col-0) plants, both the CXE15-overexpressing CXE_OE1 and CXE_OE8 and max3 plants showed the characteristic high-branching and dwarfism phenotypes associated with SL depletion (Fig. 5C), in agreement with previous reports21,25. To determine the effect of ROS on CXE15 activity, we treated the plants with methyl viologen that induces ROS production in the plants31. Methyl viologen treatment did not affect the branching phenotype in max3 plants but significantly reduced the number of branches in CXE_OE8, in line with the inactivation of CXE15 through disulphide-mediated dimerisation (Fig. 5C, D, Supplementary Fig. 9). To confirm that the rescue of branching phenotype observed upon methyl virologen treatment is caused by an increase in SL content, we quantified the major active Arabidopsis SL methyl carlactonate (MeCLA)28. Col-0 Arabidopsis contained markedly more MeCLA than CXE_OE8 plants, in agreement with higher SL catabolism in the latter (Fig. 5E). Methyl viologen treatment resulted in equal MeCLA content in both Col-0 and CXE15_OE8 Arabidopsis, suggesting that the reduced branches were due to the deactivation of CXE15 in planta (Fig. 5E, Supplementary Fig. 10).

To confirm the effect of Cys14 for CXE15 dimer stabilisation and cross-linking, we generated and phenotyped two overexpression lines carrying the C14S mutation: CXE15_C14S_OE1 and CXE15_C14S_OE6. Under non-stress conditions, these lines exhibited a moderate reduction in plant height, but had no significant effect on bud outgrowth and MeCLA content (Supplementary Fig. 11). This mild phenotype is consistent with a synergy between a diminished dimerisation capability of this mutant and a lower overexpression levels of the C14S mutant compared to WT, in particular in the shoots (Supplementary Fig. 12). Notably, in contrast to wild-type overexpression lines, the C14S lines showed no significant changes in height, bud number, or MeCLA content, supporting the role of Cys14 in dimer stabilisation and ROS-mediated inhibition of CXE15 activity.

To ensure that the observed effects were not specific to ROS generated by methyl viologen, we further examined CXE15_OE5 and CXE15_OE8 lines under oxidative stress induced by high salinity and phosphate starvation. In both conditions, the enhanced branching phenotype was suppressed, with a marked reduction in axillary bud formation (Supplementary Fig. 13). These results confirmed that CXE15 is inactivated under oxidative stress.

Discussion

SL production, perception, and degradation are crucial for plant development and resilience, necessitating tight regulation29,30,32. Uniquely among plant hormones, the SL receptor D14 (along with its homologous HTL and KAI2) also cleaves SLs. However, this reaction is too slow to control SL abundance13. Moreover, D14-mediated SL hydrolysis is coupled with a biological function, i.e. signal transduction involving ubiquitination and degradation of the target, different from regulating SL content. The recent identification of A. thaliana CXE15 as a carboxylesterase hydrolysing SLs revealed an enzymatic route for SL degradation21. Given that both D14 and CXE15 are carboxylesterases that cleave SLs into the same reaction products, it was suggested that they share a basic reaction mechanism21.

Indeed, our analysis highlights several parallels: Both CXE15 and D14 have their catalytic residues in the same relative positions within the α/β-hydrolase core, link SL hydrolysis with large structural rearrangements, and have evolved structural extensions to accommodate and position the relatively large SLs for hydrolysis in a shallow α/β-hydrolase core active site. However, their mechanisms and resulting features of D14 and CXE15 differ substantially. D14 has evolved a ~70 residue extension between β5 and β6 that forms a hydrophobic funnel above the active site to contain SLs. Conversely, CXE15 uses conformational changes of the ~45 residue Nt to convert the shallow catalytic site of the monomer into a large hydrophobic ligand-binding groove within a catalytically active dimer. Although the Nt helix of the dimer must open and close for each catalytic cycle, CXE15 exhibits fast substrate cleavage and product release. SL hydrolysis by D14, however, is slow and coupled to the retention of the D-ring and structural changes that allow D14 to link an E3 ligase with its transcriptional repressor targets3,12,13,16,25,33,34. Jointly, D14, CXE15, and the gibberellin receptor GID1 highlight how modifications and extensions of the α/β-hydrolase core result in proteins with catalytic and dynamic features adapted to different phytohormone responses.

While this manuscript was in preparation, a first structural and functional analysis of CXE15 had been reported by Palayam et al.25, already identifying the unusual Nt helix as critical for supporting SL hydrolysis. Our findings align with and complete this earlier work in several key areas, including the structure of the catalytic core, identification of catalytic residues, and demonstration of rapid SL hydrolysis by CXE15 compared to D14/HTL/KAI2, without thermal destabilisation upon GR24 binding and cleavage.

However, our study reveals key structural features that were not recognized by Palayam et al.: We identified the disulphide-linked CXE15 dimer tethered by the intertwined Nt in one crystal form, and we determined a monomeric crystal structure of CXE15 with a distinct Nt conformation. These insights, supported by extensive in vitro and in planta experiments, were critical for uncovering the structural mechanism controlling CXE15 function (summarised in Fig. 6).

Left: in monomeric CXE15 the Nt forms a β-sheet (grey) which is connected to the hydrolase core (pink) by a flexible linker (magenta line). The Nt β-sheet partly covers the active site opening of the hydrolase core. Middle: sufficient CXE15 expression promotes its dimerisation through linker arm exchange (protomers are in pink and grey). The Nt forms a helix (spiral) that also includes Cys14 (cyan position). The combined active site openings of the dimer can harbour an SL for cleavage. However, SL access to the active site requires opening of the Nt helix (illustrated through arrows and schematic helix movement). Right: Oxidising conditions, caused by ROS, link both Cys14 through a disulphide bond, precluding helix opening and SL hydrolysis. Created in BioRender. Wang, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/fmiylyi.

This mechanism suggests two modes of regulation. First, our observation that only the dimeric form is catalytically active—and that dimerisation occurs with moderate micromolar affinity—implies that CXE15 activity can be modulated by expression levels or local protein enrichment. In support, Xu et al.21 reported that CXE15 was induced following exogenous SL applications. Dimerisation may also be influenced by interacting proteins or small-molecule ligands, further tuning CXE15 activity. Interestingly, the crystallisation agents (0.2 M sodium acetate trihydrate and 20% w/v PEG 3350) appear to have blocked CXE15 dimerisation and preserved the protein in the monomeric form despite the high protein concentration in the P3₂21 crystal form. A full characterisation of this mode of regulation warrants further analysis.

Second, our structural, biochemical, and in planta analyses reveal that ROS-induced oxidation of CXE15 leads to dimerisation via a disulphide bond between Cys14 residues, blocking access to the active site and SL catabolism. This mechanism provides direct structural evidence for ROS-mediated enzymatic regulation in plants. ROS are rapidly produced under biotic and abiotic stress and increasingly recognized as signaling molecules that modulate protein function through oxidative post-translational modifications2,26. Recent studies show, for example, that ROS-induced cysteine oxidation regulates auxin signaling by promoting multimerization of the transcriptional repressor IAA3 and nuclear import of the F-box proteins TIR1/AFB35,36. In biotic stress, ROS modify transcription factors like bHLH25 and CHE, altering their DNA-binding and defense functions37,38. ROS also regulates MAPK signaling by activating OXI1 and inactivating MPK4 via cysteine oxidation39,40. However, the resulting mechanistic models rely on mutational analysis and predictive modeling rather than experimentally resolved oxidised structures. In this context, our crystallographic structure of oxidised CXE15 provides rare and direct evidence of how ROS can directly inhibit a hormone-metabolising enzyme through disulphide cross-linking. Indeed, the low-SL phenotypes, i.e., high branches and reduced plant height of CXE15 overexpressing plants, reverted to normal SL levels under methyl viologen treatments, concomitant with a decreased SL catabolism. The resulting increase in SL is beneficial for plants under stress in several ways, including acclimatisation to drought, alteration of source-sink relationships, and promoting symbiosis with mycorrhizal fungi26. Our work, therefore, expands the structural understanding of redox regulation in plants by revealing how ROS modulate hormone metabolism through targeted inhibition of SL catabolism.

Among the other Arabidopsis CXE paralogues, only CXE12 has a cysteine in the equivalent position; however, it remains to be determined if the CXE12 Nt has the same role. Thus, our analysis suggests that this regulatory mechanism is either specific to CXE15 or restricted to two paralogues in Arabidopsis (Supplementary Fig. 14). The N-terminal cysteine is highly conserved in CXE15 orthologues from monocot and dicot plant species. Notably, CXE15 from rice has the N-terminal cysteine of the Arabidopsis enzyme, whereas in rice CXE17, this cysteine is replaced by a leucine (Supplementary Fig. 15).

Our work significantly extends on previous structural and functional analyses of CXE1521,25 by uncovering how the SL-degrading activity of CXE15 is modulated by environmental factors. Thus, our results highlight how the α/β-hydrolase core can be adapted to specific tasks through structural extensions, and enhance our understanding of the molecular pathways involved in plant stress responses. These insights could also assist agricultural food production, given the crucial role of SL homeostasis in regulating crop plant branching and stress resistance.

Methods

Cloning, expression, and purification of CXE15

Full-length Arabidopsis WT CXE15, as well as the CXE15 point mutants E271Q, C14S, C14D, F89R, and W94R, the CXE15 triple mutant (L17R, L18R, L21R), the nona mutant (D13R, L17R, L18R, L21R, E30R, I32R, D33R, I35R, and K42D), and the deletion mutant Δ40 mutants were cloned into the pGEX6P-1 expression vector (GE Healthcare). The plasmids were then transformed into BL21(DE3) cells for expression. Cells were grown in LB medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) at 37 °C until an OD600 of 0.6. Protein expression was induced by adding 200 μM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and the cultures were incubated at 18 °C overnight. Further affinity purification steps were followed as previously reported41. After GST cleavage, the eluted proteins were purified on a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 prep-grade gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) using a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and 3 mM DTT. Protein purity was evaluated using SDS-PAGE. The purified proteins were concentrated to 10 mg/ml and stored at −80 °C.

Crystallisation and structure determination

CXE15, E271Q, and C14S mutants at a concentration of 10 mg/ml, purified in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, and 3 mM DTT (pH 7.5), were subjected to the sitting drop vapour diffusion method for crystallisation screening using commercially available sparse matrix screens. CXE15 WT and E271Q mutant crystals in the P 41 21 2 space group were obtained in reservoir solutions containing 1.26 M sodium phosphate monobasic monohydrate and 0.14 M potassium phosphate dibasic (pH 5.6). CXE15 WT crystals in the P 32 2 1 space group were obtained in 0.2 M sodium acetate trihydrate and 20% w/v PEG 3350. The CXE15 C14S mutant crystals were obtained in 0.056 M sodium phosphate monobasic monohydrate and 1.344 M potassium phosphate dibasic (pH 8.2). The crystals appeared after 3 days at 23 °C. For data collection, 25% glycerol was used as a cryo-protectant, and the crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. Data were collected at 100 K at the beamlines PROXIMA 1 and PROXIMA 2 A at the SOLEIL Synchrotron (France), using EIGER X 16 M and EIGER X 9 M detectors, respectively (Proposal numbers 20210195, 20210932, 20220373, 20231539). The data were processed using the “XDS made easier” pipeline42, including STARANISO43. Initial phases were determined using the Alphafold model (AF-Q9FG13-F1)44 as a search model for molecular replacement using Balbes or Phaser45,46. The structures were manually inspected and corrected using Coot47 and refined using either Phenix Refine48 or PDB redo49 (Supplementary Table 1). The figures were drawn with PyMOL50 and Chimera51.

Thermal shift assay

The thermal stability of CXE15 WT and the C14S mutant in the presence and absence of different ligands, as well as the effect of H2O2 in the presence and absence of 5 mM DTT, was determined using thermal unfolding profiles. The thermal stability of CXE15 Δ40 was measured separately. All measurements were carried out at a final protein concentration of 10 μM in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and Sypro Orange dye (Invitrogen) at a 3× final concentration. Thermal denaturation temperatures were obtained using a CFX96 Touch Real-Time Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad) with an optical reaction module by ramping the temperature between 25 and 100 °C at 1 °C per minute, with fluorescence acquisition through the channel. Data were analysed with CFX Manager Software V3.0 (Bio-Rad) and plotted using PRISM version 10.0 (www.graphpad.com).

YLG hydrolysis assay

The YLG hydrolysis assay was performed using 3 μM CXE15 in a final volume of 100 μl on a 96-well black plate (Corning). The fluorescent intensity was measured using excitation and emission wavelengths of 480 and 520 nm, respectively, in a Pherastar microplate reader (BMG Labtech). Either CXE15 WT, the CXE15 dimer purified from size exclusion, the point mutants C14S, S169A, E271Q, H302A, F89R, and W94R, the CXE15 triple mutant (L17R, L18R, L21R), or the nona mutant (D13R, E30R, D33R, L17R, L18R, L21R, I32R, I35R, K42D) were mixed with 1 μM YLG (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co. Ltd.), and the resulting fluorescence was measured every 5 min. The data were plotted using GraphPad Prism version 10.0.

Non-reducing SDS gel electrophoresis

CXE15 WT and C14S mutants were run through size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 (10/300) GL column after incubation with 10 mM hydrogen peroxide (Sigma) for 30 min at 23 °C, as well as without H2O2 incubation. Eluted proteins from the respective peaks were run on an SDS-PAGE gel in the presence and absence of 5 mM DTT. The gel was stained using Coomassie blue, then destained using 10% acetic acid, and the image was recorded using a Bio-Rad GelDoc EZ imaging system.

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC)-multi angle light scattering (MALS)

CXE15 WT and C14S mutants were run through size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 (10/300) GL column after incubation with 10 mM hydrogen peroxide (Sigma) for 30 min at 23 °C, as well as without H2O2 incubation. The eluted proteins from the SEC column were further analysed using DAWN MALS (Wyatt Technology) systems. The respective protein sizes were estimated based on the refractive index of the protein samples and analysed using ASTRA software from Wyatt Technology.

Microscale thermophoresis (MST)

CXE15 WT and C14S mutants were N-terminally labelled with Alexa Fluor 647™ NHS ester dye (Thermo Scientific). 30 µM unlabeled WT and C14S mutant proteins were serially diluted to 0.9 nM and mixed with the corresponding 25 nM labelled protein in the presence or absence of 100 µM GR24. The experiments were carried out as reported previously52,53. Specifically, a gradient increase in temperature was initiated using a laser diode, and the change in the excited fluorescence of the red dye was recorded. To determine the Kd values for the binding, the change in thermophoresis of the fluorescently labelled protein was plotted against the concentrations of unlabeled protein. Data were analysed using NanoTemper software and plotted using Prism 10.0 (www.graphpad.com).

SAXS data determination

CXE15 at 5 mg/ml was incubated with 10 mM H2O2 for 30 min before passing through SEC-SAXS in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 250 mM NaCl, pH 7.5. The data were recorded at the SWING beamline, SOLEIL, France. Measurements were carried out at 10 °C, and the scattering of the buffer was subtracted from the protein sample. The data were further processed and analysed as reported previously53. Data were analysed using PRIMUS, ATSAS software package54, and FOXS55.

Cavity calculation and molecular docking of GR24 to CXE15

The CASTp server56 was used to compute the cavity topography of the CXE15 monomer, dimer, and AlphaFold models, with figures prepared using Chimera51. Our CXE15 monomeric and dimeric structures served as receptors for docking the ligand GR24 using AutoDock Vina version 4.2.657,58,59. The model with the lowest possible free energy was selected and analysed for potential interaction sites, with figures prepared using PyMOL50.

Determination of CXE15 midpoint redox potential

The redox titration was conducted to determine the redox state of the CXE15 disulphide bond, which forms under oxidising conditions. The ambient redox potential was adjusted using a combination of DTTred and DTTox. Mixtures containing 3 µM oxidised CXE15 in its initial redox state were incubated for 2 h at 25 °C in a solution of 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), and 10 mM reduced/oxidised DTT at various dithiol/disulphide ratios, in a final volume of 100 µl. Following incubation, CXE15 activity was assayed as described above using YLG hydrolysis assay.The data were fitted to evaluate the catalytic activity of oxidised CXE15 as a function of the redox potential of the DTTred and DTTox redox couple60,61,62. Midpoint redox potentials are reported as the mean ± S.D.

Transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana, RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis

Transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana was performed using the floral dip method63. Plants were grown under long-day conditions (16 h light/8 h dark) until the mature flowering stage. Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101, containing the binary vector (pMDC43, Plasmid #96978), was grown overnight in 3 ml of LB broth media with 50 mg/L kanamycin and 25 mg/L rifampicin at 28 °C. Overnight cultures were inoculated into 200 ml of LB broth media with 50 mg/L kanamycin and 25 mg/L rifampicin and incubated at 28 °C with shaking at 220 rpm until the OD600 reached 0.5. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 12,000×g for 15 min and resuspended in 200 ml of floral dip inoculation medium63, which contained ½ MS medium, 0.5% sucrose, 0.05% Silwet L-77, and 44 µM benzylaminopurine, with the pH adjusted to 5.7. For the floral dip, plants were inverted and dipped in the inoculation medium for 5–10 s and then removed gently. Plants were then incubated overnight in the dark. Plants were grown for the next 3–5 weeks until dry, at which point seeds were ready to be harvested. Seeds of transformed plants were harvested, sterilised, and sown in 1% agar containing ½ MS medium, 1% sucrose, and 25 μg/ml of hygromycin. Seeds were stratified for 2 days under dark conditions at 4 °C. Then, seeds were transferred to a growth chamber at 22 °C under long-day conditions. After 7–10 days, antibiotic-resistant transformants were selected and transferred to soil for the propagation of the T1 generation. pMDC43-SEIPIN3 was a gift from Kent Chapman (Addgene plasmid # 96978; http://n2t.net/addgene:96978; RRID:Addgene_96978)64.

Total RNA was extracted from Arabidopsis seedlings using the Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep Plus Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). Briefly, 1 μg RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA with the iScript™ cDNA synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Amplification with primers (Supplementary Table 4) was performed using the SYBR Green Real-Time PCR Master Mix kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The qRT-PCR program was run in a StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies). The thermal profile was 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, 60 °C for 20 s and 72 °C for 20 s. The quantitative expression level of CXE15 was normalized to that of the housekeeping gene (AtActin), and relative expression was calculated according to the 2 − ΔΔCT method.

Yeast 2 hybrid screening

Yeast two-hybrid assays were conducted using the MATCHMAKER GAL4 system (Clontech, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Full-length coding sequences of CXE15 and its mutant variants were inserted into the pGADT-7 (activation domain) and pGBKT-7 (binding domain) vectors (Clontech, USA, PT3249-5 and PT3248-5, respectively) using EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain AH109 was co-transformed with the respective constructs. Individual colonies were cultured in 5 mL of synthetic dropout (SD) medium lacking tryptophan and leucine (SD–WL) at 30 °C for 16 h. Cultures were normalized to an OD600 of 0.5. A 10 µL aliquot of each culture was spotted onto SD–WL and selective SD medium lacking alanine, tryptophan, leucine, and histidine (SD–AWLH) with X-Gal. Plates were incubated at 30 °C for 5 days to assess protein–protein interactions.

A. thaliana growth in the Hydroponic condition

Initially, A. thaliana (Col-0), AtCXE_OE1, AtCXE_OE5, AtCXE_OE8, AtCXE-C14S _OE1, and AtCXE-C14S _OE6 were grown for 2 weeks in the designed box with a modified Hoagland nutrient solution as described63. The nutrient solution consisted of macronutrients in mM: 5.6 NH4NO3, 0.4 K2HPO4.3H2O, 0.8 MgSO4.7H2O, 0.8 K2SO4, 0.18 FeSO4.7H2O, 0.18 Na2EDTA.2H2O; and micronutrients in µM: 23 H3BO3, 4.5 MnCl2.4H2O, 0.3 CuSO4.5H2O, 1.5 ZnCl2, and 0.1 Na2MoO4.2H2O with adjusted pH value of 5.8. The nutrient solution was replaced twice a week. After 2 weeks, the seedlings were transferred into 50 ml black tubes and grown for another three weeks. For phosphorus (P) starvation, P depletion was applied for seven days by replacing the nutrient solution with a phosphate (K2HPO4·3H2O)-free solution, while untreated plants continued to be grown in the regular nutrient solution. Plants were grown in a growth chamber (Percival) under short-day conditions (10 h light/14 h dark) at 22 °C, 55% humidity, and 100 µmol m−2 s−1 light intensity.

Transient expression in leaves of N. benthamiana

Liquid Agrobacterium strain cultures (GV3101) harbouring the pMDC43_CXE15, pYFC43_CXE15, pYFC43_C14D, pYFC43_C14S, pYFN43_CXE15, pYFN43_C14D and pYFN43_C14S gene were grown at 28 °C and 220 rpm for 2 days in LB medium with kanamycin (50 mg/L), gentamycin (25 mg/L), and rifampicin (35 mg/L). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3000×g for 15 min at room temperature and then resuspended in 10 mM MES-KOH buffer (pH 5.7) containing 10 mM MgCl₂ and 100 mM acetosyringone (4’-hydroxy-3’,5’-dimethoxyacetophenone; Sigma) to a final OD600 of 0.5, then stored at room temperature for 2–4 h. Nicotiana benthamiana plants were grown in soil pots in the greenhouse under long-day conditions (16 h light/8 h dark) at 22 °C. The Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression in leaves of N. benthamiana was performed using a 1-ml syringe. Leaves of the same stage were selected to minimise variability. For each gene combination, two or three leaves from each plant were infiltrated, and a total of three plants were used for individual biological replicates. The bacterial suspension in the buffer was slowly injected into the abaxial side of the leaf to spread throughout the whole leaf area. Two days after infiltration, the infiltrated leaves were harvested for further analysis. YFP fluorescence was assayed using an inverted LSM 710 AxioObserver confocal laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss) with EC Plan-Neofluar 40×/1.3 Oil objectives. YFP was excited using a 488-nm line of an argon laser, and emission was filtered using a BP 493–550 nm filter. The data were plotted using GraphPad Prism version 10.0. pYFC43 and pYFN43 were a gift from Alejandro Ferrando (Addgene plasmid #89488, #89487; http://n2t.net/addgene:89488, http://n2t.net/addgene:89487; RRID:Addgene_89488, Addgene_89487)65.

SL extraction and analysis

The SL analogue, rac-GR24 (100 μM), was incubated with or without 20 μM purified CXE15-GST for 4 h at 37 °C in PBS buffer (1 ml, pH 7.4, 5% DMSO) in a total volume of 200 μl. After 4 h, the reaction was stopped by adding 800 μl of ice-cold acetone and incubating at −20 °C for 2 h. The corresponding ABC-FTL product and remaining substrate were analysed after filtering with a 0.22 μm filter. Extraction of SLs in Arabidopsis roots followed the published procedure66,67. Briefly, lyophilized roots were extracted with 2 ml of acetone twice, by incubation for 30 min at 4 °C followed by centrifugation for 5 min at 1356×g at 4 °C. The two supernatants were combined and dried under vacuum. The residue was re-dissolved in 100 μl of acetonitrile:water (25:75, v:v), and filtered through a 0.22 μm filter for LC-MS/MS analysis.

The analysis of SLs was performed using a UHPLC-Orbitrap ID-X Tribrid Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Scientific™) with a heated-electrospray ionisation source. Chromatographic separation was achieved on Hypersil GOLD C18 Selectivity HPLC Columns (150 × 4.6 mm; 3 μm; Thermo Scientific™) with mobile phases consisting of water (A) and acetonitrile (B), both containing 0.1% formic acid, and the following linear gradient (flow rate, 0.5 mL/min): 0–15 min, 25–100% B, followed by washing with 100% B and equilibration with 25% B for 3 min. The injection volume was 10 μL, and the column temperature was maintained at 30 °C for each run. The MS conditions were as follows: positive mode, ion source of H-ESI, spray voltage of 3500 V, sheath gas flow rate of 60 arbitrary units, auxiliary gas flow rate of 15 arbitrary units, sweep gas flow rate of 2 arbitrary units, ion transfer tube temperature of 350 °C, vaporizer temperature of 400 °C, S-lens RF level of 60, resolution of 120,000 for MS; stepped HCD collision energies of 10–50%, and resolution of 30,000 for MS/MS. The mass accuracy of the identified compounds (accurate mass ± 5 ppm mass tolerance) was acquired using Xcalibur software version 4.1.

SL samples were analysed using a Vanquish Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) system (Thermo Scientific™) coupled to a timsTOF Pro 2 mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Germany). Sample extracts were separated on a CSH C18 UPLC column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 µm, Waters) using a mobile phase consisting of H2O with 0.1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (B). The gradient used for the analysis was 0–1 min, 1% B; 1–15 min, 1–100% B, followed by washing with 100% B and equilibration with 1% B for 4.5 min. The injection volume for all samples was 10 µL, and the flow rate was set at 0.4 mL/min. The column oven and autosampler temperatures were held at 40 °C and 5 °C, respectively.

The mass spectrometer was operated in positive mode using a vacuum insulated probe—heated electrospray (VIP-HESI) source. The capillary voltage was set at 4500 V, the nebulizer gas pressure was set to 3.5 bar, and the dry gas and sheath gas flow rates were set to 10 L/min and 5.0 L/min, respectively. The dry temperature and sheath gas temperature were maintained at 260 °C and 350 °C, respectively. The acquisition was performed in a mass range of 20–1200 m/z using Parallel Accumulation-Serial Fragmentation (PASEF), and the ion mobility range was set from 0.55 to 1.86 1/K₀. The MS/MS was acquired with stepped collision energies of 20–40 eV. The acquired raw data were processed using DataAnalysis software version 6.0 (Bruker Daltonics, Germany). The data were plotted using GraphPad Prism version 10.0.

Molecular dynamics

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed in triplicate, following the same protocol as in our previous study68. The starting structures were obtained as follows: the monomeric CXE15 structure was modeled with SwissModel using the entire sequence containing the missing N-terminal residues from Uniprot, where pdb 8zro was used as a template. The CXE15 WT dimer was constructed by applying the crystallographic 2-fold axis of pdb 8zrf. The CXE15 C14S mutant was derived from the crystallographic dimer of pdb 8zrg. The dimeric nona mutant structure was derived from pdb 8zrf by introducing the mutants in silico using mutagenesis extension in PyMOL (Pymol.org). Because none of the crystal structure showed clear density for the strigolactone ligand, we docked GR24 into the CXE15 monomer structure using Alphafold369 (ipTM = 0.91 and pTM = 0.94) and into the CXE15 dimer using the SwissDock online web server58,59 (∆G: −7.43 kcal/mol), because AlphaFold3 failed to correctly predict the CXE15 dimer structure. MD simulations were performed using GROMACS 2024.370. The protein structures were inserted into a cubic box filled with water molecules (TIP3P) with the box size having a minimum distance of 10.0 Å from the protein edges. Na+ and Cl− ions were used to neutralize the system. All structures were passed through energy minimization followed by equilibration for 10 ns using NVT71 for computing velocities and atom positions. The structures were further equilibrated for 10 ns with (NPT) for constant pressure. Periodic boundary conditions (PBC) were applied in the X, Y, and Z directions. The production simulations were conducted using NPT for 500 ns for each structure, where the temperature was constant at 300 K using a velocity-rescale thermostat71,72 (τP = 2.0 ps). Output trajectories were analysed using GROMACS 202470 and PyMol50.

Mass spectrometry for the CXE15

About 100 µg of CXE15 was subjected to trypsin digestion, and then dried in speedvac for 18 h to a dry powder, which resulted in dried peptides. Thus obtained dried peptides were reconstituted in a solution containing 5% (v/v) acetonitrile and 0.1% (v/v) formic acid and analysed on the Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) coupled to a Vanquish Neo nano HPLC system (Thermo Scientific). The peptide samples were loaded onto an PEPMAP NEO C18 trap column (300 µm × 5 mm, 5 µm; Thermo Scientific) and resolved on a PepMap RSLC C18 analytical column (2 µm, 100 A, 75 µm × 25 cm; Thermo Scientific) at a flow rate of 250 nL/min over a 60 min gradient. Water with 0.1% FA (solvent A) and 95% ACN with 0.1% FA (solvent B) were used as mobile phases. The peptides were eluted from the column over a 50 min multistep gradient using 2–40% of solvent B followed by 1 min gradient to 95% B. The column was then maintained at 95% B for another 8 min to ensure elution of all the peptides before final equilibration with 2% B.

The spray was initiated by applying 1900 V to the EASY-Spray emitter and the data were acquired under the control of Xcalibur software in a data-dependent mode using top speed and 3 s duration per cycle. The Orbitrap was operated in positive ionisation mode, using the lock mass option (reference ion at m/z 445.120025) to ensure more accurate mass measurements in FTMS mode. The survey scan was recorded covering the m/z ranges from 350 to 1500 Th in profile mode with a resolution set to 60,000. The automatic gain control (AGC) target was set to standard and the maximum injection time was set to 50 ms. The most intense ions with charge state 2+ to 5+ were selected for fragmentation using HCD with a fixed collision energy mode. The HCD collision energy was set to 30% and the precursor ions were isolated using a 1.6 Th window. The AGC target was set to standard with a maximum injection time mode set to dynamic. The spectra were acquired using a 30,000 resolution.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used Copilot in order to improve the language in some passages. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Coordinates for the reported structures are deposited to the RCSB-PDB with the following codes: 8ZRF; 8ZRO; 8ZRG; 8ZR6. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Xie, X. et al. Structure- and stereospecific transport of strigolactones from roots to shoots. J. Pestic. Sci. 41, 55–58 (2016).

Wang, J. Y., Chen, G.-T. E., Braguy, J. & Al-Babili, S. Distinguishing the functions of canonical strigolactones as rhizospheric signals. Trends Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2024.02.013 (2024).

Alvi, A. F., Sehar, Z., Fatma, M., Masood, A. & Khan, N. A. Strigolactone: an emerging growth regulator for developing resilience in plants. Plants 11, 2604 (2022).

Fiorilli, V., Wang, J. Y., Bonfante, P., Lanfranco, L. & Al-Babili, S. Apocarotenoids: old and new mediators of the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1186 (2019).

Wang, J. Y. et al. Perspectives on the metabolism of strigolactone rhizospheric signals. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1062107 (2022).

Müller, L. M. & Harrison, M. J. Phytohormones, miRNAs, and peptide signals integrate plant phosphorus status with arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 50, 132–139 (2019).

Jamil, M. et al. Abscisic acid inhibits germination of Striga seeds and is released by them likely as a rhizospheric signal supporting host infestation. Plant J. 117, 1305–1316 (2024).

Yoneyama, K. et al. Which are the major players, canonical or non-canonical strigolactones? J. Exp. Bot. 69, 2231–2239 (2018).

Bruno, M. et al. Insights into the formation of carlactone from in-depth analysis of the CCD 8-catalyzed reactions. FEBS Lett. 591, 792–800 (2017).

Seto, Y. et al. Carlactone is an endogenous biosynthetic precursor for strigolactones. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 1640–1645 (2014).

Hu, Q. et al. DWARF14, a receptor covalently linked with the active form of strigolactones, undergoes strigolactone-dependent degradation in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1935 (2017).

Zhao, L.-H. et al. Destabilization of strigolactone receptor DWARF14 by binding of ligand and E3-ligase signaling effector DWARF3. Cell Res. 25, 1219–1236 (2015).

Seto, Y. et al. Strigolactone perception and deactivation by a hydrolase receptor DWARF14. Nat. Commun. 10, 191 (2019).

Yang, T. et al. The SUPPRESSOR of MAX2 1 (SMAX1)-like SMXL6, SMXL7 and SMXL8 act as negative regulators in response to drought stress in arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 61, 1477–1492 (2020).

Chevalier, F. et al. Strigolactone promotes degradation of DWARF14, an α/β hydrolase essential for strigolactone signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 1134–1150 (2014).

Shabek, N. et al. Structural plasticity of D3–D14 ubiquitin ligase in strigolactone signalling. Nature 563, 652–656 (2018).

White, A. R. F., Mendez, J. A., Khosla, A. & Nelson, D. C. Rapid analysis of strigolactone receptor activity in a Nicotiana benthamiana dwarf14 mutant. Plant Direct 6, e389 (2022).

Zheng, N. & Shabek, N. Ubiquitin ligases: structure, function, and regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 86, 129–157 (2017).

Hasan, M.dM. et al. GABA: a key player in drought stress resistance in plants. IJMS 22, 10136 (2021).

Mindrebo, J. T., Nartey, C. M., Seto, Y., Burkart, M. D. & Noel, J. P. Unveiling the functional diversity of the alpha/beta hydrolase superfamily in the plant kingdom. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 41, 233–246 (2016).

Xu, E. et al. Catabolism of strigolactones by a carboxylesterase. Nat. Plants 7, 1495–1504 (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. The functional characterization of carboxylesterases involved in the degradation of volatile esters produced in strawberry fruits. IJMS 24, 383 (2022).

Nakamura, H. et al. Molecular mechanism of strigolactone perception by DWARF14. Nat. Commun. 4, 2613 (2013).

Alashoor, K. F., Wang, J. Y. & Al-Babili, S. The role of hydrolysis in perceiving and degrading the plant hormone strigolactones. Trends Biochem. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2024.09.006 (2024).

Palayam, M. et al. Structural insights into strigolactone catabolism by carboxylesterases reveal a conserved conformational regulation. Nat. Commun. 15, 6500 (2024).

Hernández, I. & Munné-Bosch, S. Linking phosphorus availability with photo-oxidative stress in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 2889–2900 (2015).

Nakamura, H. et al. Triazole ureas covalently bind to strigolactone receptor and antagonize strigolactone responses. Mol. Plant 12, 44–58 (2019).

Mashiguchi, K. et al. A carlactonoic acid methyltransferase that contributes to the inhibition of shoot branching in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2111565119 (2022).

Zhao, S. et al. Regulation of plant responses to salt stress. IJMS 22, 4609 (2021).

Mitra, D. et al. Impacts of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on rice growth, development, and stress management with a particular emphasis on strigolactone effects on root development. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 52, 1591–1621 (2021).

Cui, F. et al. Interaction of methyl viologen-induced chloroplast and mitochondrial signalling in Arabidopsis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 134, 555–566 (2019).

Sachdev, S., Ansari, S. A., Ansari, M. I., Fujita, M. & Hasanuzzaman, M. Abiotic stress and reactive oxygen species: generation, signaling, and defense mechanisms. Antioxidants 10, 277 (2021).

Guercio, A. M., Palayam, M. & Shabek, N. Strigolactones: diversity, perception, and hydrolysis. Phytochem. Rev. 22, 339–359 (2023).

Kelley, D. R. E3 ubiquitin ligases: key regulators of hormone signaling in plants. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 17, 1047–1054 (2018).

Roy, D. et al. Redox-regulated Aux/IAA multimerization modulates auxin responses. Science 389, eadu1470 (2025).

Lu, B. et al. FERONIA-mediated TIR1/AFB2 oxidation stimulates auxin signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 17, 772–787 (2024).

Liao, H. et al. Rice transcription factor bHLH25 confers resistance to multiple diseases by sensing H2O2. Cell Res. 35, 205–219 (2025).

Cao, L. et al. H2O2 sulfenylates CHE, linking local infection to the establishment of systemic acquired resistance. Science 385, 1211–1217 (2024).

Ma, M. et al. The OXIDATIVE SIGNAL-INDUCIBLE1 kinase regulates plant immunity by linking microbial pattern–induced reactive oxygen species burst to MAP kinase activation. Plant Cell 37, koae311 (2024).

Siodmak, A. et al. Essential role of the CD docking motif of MPK4 in plant immunity, growth and development. N. Phytol. 239, 1112–1126 (2023).

Shahul Hameed, U. et al. Structural basis for specific inhibition of the highly sensitive ShHTL7 receptor. EMBO Rep. 23, e54145 (2022).

Legrandp, Soleilproxima1, Aishima, J. & CV-GPhL. legrandp/xdsme: March 2019 version working with the latest XDS version (Jan 26, 2018). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.837885 (2019).

Vonrhein, C. et al. Data processing and analysis with the autoPROC toolbox. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 293–302 (2011).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Long, F., Vagin, A. A., Young, P. & Murshudov, G. N. BALBES: a molecular-replacement pipeline. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 64, 125–132 (2008).

McCoy, A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 (2007).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010).

Joosten, R. P., Long, F., Murshudov, G. N. & Perrakis, A. The PDB_REDO server for macromolecular structure model optimization. IUCrJ 1, 213–220 (2014).

Schrödinger, L. & DeLano, W., 2020. PyMOL. Available at: http://www.pymol.org/pymol.

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

Zarban, R. A. et al. Rational design of Striga hermonthica-specific seed germination inhibitors. Plant Physiol. 188, 1369–1384 (2022).

Shahul Hameed, U. F. et al. H-NS uses an autoinhibitory conformational switch for environment-controlled gene silencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 2666–2680 (2019).

Konarev, P. V., Petoukhov, M. V., Volkov, V. V. & Svergun, D. I. ATSAS 2.1, a program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 39, 277–286 (2006).

Schneidman-Duhovny, D., Hammel, M. & Sali, A. FoXS: a web server for rapid computation and fitting of SAXS profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W540–W544 (2010).

Tian, W., Chen, C., Lei, X., Zhao, J. & Liang, J. CASTp 3.0: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W363–W367 (2018).

Eberhardt, J., Santos-Martins, D., Tillack, A. F. & Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new docking methods, expanded force field and Python bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61, 3891–3898 (2021).

Bugnon, M. et al. SwissDock 2024: major enhancements for small-molecule docking with Attracting Cavities and AutoDock Vina. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W324–W332 (2024).

Grosdidier, A., Zoete, V. & Michielin, O. SwissDock, a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W270–W277 (2011).

Hirasawa, M. et al. Oxidation-reduction properties of chloroplast thioredoxins, ferredoxin:thioredoxin reductase, and thioredoxin f -regulated enzymes. Biochemistry 38, 5200–5205 (1999).

Hutchison, R. S. & Ort, D. R. [23] Measurement of equilibrium midpoint potentials of thiol/disulfide regulatory groups on thioredoxinactivated chloroplast enzymes. in Methods in Enzymology vol. 252 pp 220–228 (Elsevier, 1995).

Zaffagnini, M., Michelet, L., Massot, V., Trost, P. & Lemaire, S. D. Biochemical characterization of glutaredoxins from chlamydomonas reinhardtii reveals the unique properties of a chloroplastic CGFS-type glutaredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 8868–8876 (2008).

Clough, S. J. & Bent, A. F. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium -mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743 (1998).

Cai, Y. et al. Arabidopsis SEIPIN proteins modulate triacylglycerol accumulation and influence lipid droplet proliferation. Plant Cell. 27, 2616–2636 (2015).

Belda-Palazón, B. et al. Aminopropyltransferases involved in polyamine biosynthesis localize preferentially in the nucleus of plant cells. PLoS ONE 7, e46907 (2012).

Ablazov, A. et al. The apocarotenoid zaxinone is a positive regulator of strigolactone and abscisic acid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis roots. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 578 (2020).

Wang, J. Y. et al. The apocarotenoid metabolite zaxinone regulates growth and strigolactone biosynthesis in rice. Nat. Commun. 10, 810 (2019).

Aldehaiman, A. et al. Synergy and allostery in ligand binding by HIV-1 Nef. Biochem. J. 478, 1525–1545 (2021).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1–2, 19–25 (2015).

Bussi, G., Donadio, D. & Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 014101 (2007).

Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 7182–7190 (1981).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) through the baseline fund to S.A.B., and S.T.A. We acknowledge SOLEIL for provision of synchrotron radiation facilities and would like to thank A. Thompson, P. Legrand, S. Sirigu, M. Savko, B. Shepard and A. Thureau for assistance in using the beamlines PROXIMA 1, PROXIMA 2 A, and SWING (Proposal IDs:20210195, 20210932, 20220373, 20231539). For computer time, this research used the resources of the KAUST Supercomputing Laboratory, and experimental research was supported by the Bioscience Core Lab and the Imaging and Characterization Core Lab at King Abdullah University of Science & Technology (KAUST) in Thuwal, Saudi Arabia. We would like to thank the KAUST ACL proteomics core lab for the mass spectrometry analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T.A., S.A.B., U.F.S.H., A.B., D.A. and J.Y.W. conceived and designed the experiments. U.F.S.H., and A.B. conducted the protein purification, biochemical assays, and crystallisation. U.F.S.H and and S.T.A. did the crystallographic data collection and structural analysis. A.B., D.A. and J.Y.W. generated CXE-OE lines and performed in planta experiments. A.B. and D.A. performed BiFC assays in Tobacco leaves. J.Y.W., and A.S., performed the LC-MS analysis. U.F.S.H., and A.B. performed the MS experiments. A.A.M., and S.T.A. performed the MD simulation analysis. S.T.A., S.A.B., U.F.S.H., and J.Y.W. wrote the manuscript with the help of D.A., A.B., A.S., and A.A.M.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Feng Zhang and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shahul Hameed, U.F., Balakrishna, A., Wang, J.Y. et al. Molecular Basis for Catalysis and Regulation of the Strigolactone Catabolic Enzyme CXE15. Nat Commun 16, 10290 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65204-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65204-1