Abstract

Photonic crystal fibers (PCFs) that trap and guide light using photonic bandgaps have revolutionized modern optics with enormous scientific innovations and technological applications spanning many disciplines. Recently, inspired by the discovery of topological phases of matter, Dirac-vortex topological PCFs have been theoretically proposed with intriguing topological properties and unprecedented opportunities in optical fiber communications. However, due to the substantial challenges of fabrication and characterization, experimental demonstration of Dirac-vortex topological PCFs has thus far remained elusive. Here, we report the experimental realization of a Dirac-vortex topological PCF using the standard stack-and-draw fabrication process with silica glass capillaries. Moreover, we experimentally observe that the Dirac-vortex single-polarization single-mode is bound to and propagates along the fiber core in the full communication window (1260-1675 nm). Our study pushes the research frontier of PCFs and provides a new avenue to enhance their performance and functionality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since their discovery in 1991, photonic crystal fibers (PCFs)1,2 that use photonic bandgaps to confine and guide light have attracted great attention across many disciplines due to their outstanding ability to overcome the limitations of conventional optical fibers, such as bending-insensitive low-loss guidance of light, design flexibility of fiber cross-sections, and high-power light delivery. Recently, inspired by the advancements in topological photonics3,4,5,6,7,8,9, the concept of topological PCFs with robust topological protection has been theoretically proposed10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 based on different physical mechanisms and experimentally demonstrated18,19 in a multicore PCF whose cores are arranged in a Su–Schrieffer–Heeger chain with topological end states, significantly improving the performance and functionality of conventional PCFs. The unique properties of topological PCFs, such as the single-polarization single-mode7, azimuthally and radially polarized orbital angular momentum (OAM+1)20, and near-zero flattened dispersion21, exhibit promising potential applications in next-generation robust quantum networks and optical communications. In particular, Dirac-vortex topological PCFs7, originating from Dirac-vortex states in a Kekulé-distorted honeycomb lattice22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, have been theoretically proposed with ultra-broadband single-polarization single-mode light transport or arbitrary degenerate fiber modes. However, due to the challenge of sample fabrication and experimental characterization, Dirac-vortex topological PCFs have thus far remained out of experimental reach.

Here, we fabricated and experimentally demonstrated, for the first time to our best knowledge, the Dirac-vortex topological PCF using the standard stack-and-draw process with silica glass tubes. In particular, we directly observed that the Dirac-vortex fiber mode bounds to and propagates along the fiber core, with its unique intensity profile and polarization distribution consistent with the theoretical results in a wide wavelength range (1260–1675 nm). Moreover, we experimentally explored the influence of different incident light beams on the fiber output, exhibiting excellent and robust single-polarization single-mode property of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF.

Results

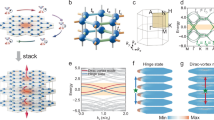

We begin with a common silica PCF with perfect triangular lattice of air holes and introduce Kekulé distortion to the thickness of the silica struts in the cross section to construct a Dirac-vortex topological PCF, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. Figure 1b shows a unit cell of the cross section of the perfect triangular PCF with a lattice constant of \(\sqrt{3}\) a (a = 3 µm) and a silica strut width of t0 = 0.16a. The Kekulé distortion is introduced by changing the strut width with Dirac mass \(m={m}_{0}{e}^{i\varphi }\), where m0 is the amplitude of the Dirac mass, \(\varphi=\omega \theta (r)\) is the vortex phase angle, \(\theta \left(r\right)\) is the space phase angle, and ω is the vortex winding number. After Kekulé distortion, the strut width becomes t1 = t0 + m0cos(φ) (red color), t2 = t0 + m0cos(φ + 2π/3) (blue color), and t3 = t0 + m0cos(φ + 4π/3) (green color), where t0 = 0.16a and winding number ω = 1, as shown in Fig. 1c. When the Dirac mass m0 = 0 (without Kekulé distortion), the bulk band structure of the perfect triangular PCF (blue lines) exhibits a double Dirac point with fourfold degeneracy at the Γ point with nonzero wave vector kz. When m0 ≠ 0 (m0 = 0.024a) and φ = π/3 (with Kekulé distortion), the double Dirac point with fourfold degeneracy will be lifted (gray lines), opening a complete topological photonic bandgap at kz = 4π/a (see the band inversion and Wilson loop in Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig 1), as shown in Fig. 1d. More significantly, though the topological photonic bandgap range has a minor regular fluctuation from 186.26 to 189.08 THz with different φ, it persists for arbitrary phase of φ if m0 ≠ 0, as shown in Fig. 1e, in which the color represents the phase φ varying from 0 to 2π. We then arrange a series of Kekulé-distorted triangular photonic crystals with six different modulation phases φ angularly around the fiber core to form a Dirac-vortex topological PCF, as shown in Fig. 1f. As a result, a single Dirac-vortex topological PCF mode appears in the middle of the bandgap, being tightly localized and propagating along the fiber core with a nonzero wave vector kz.

a Schematic of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF. The unit cell of the cross-section of a triangular PCF without (b) and with c Kekulé distortion. The Kekulé distortion is introduced by changing the strut width with m0 and phase φ, where t1 = t0 + m0cos(φ), t2 = t0 + m0cos(φ + 2π/3), t3 = t0 + m0cos(φ + 4π/3), t0 = 0.16a, and a = 3 µm. d Simulated bulk band structures of the triangular PCF without (blue lines) and with (gray lines) φ = π/3 Kekulé distortion at kz = 4π/a, respectively. The grown region indicates the photonic bandgap. e Vortex bandgaps with fixed Dirac mass m0 = 0.024a and different phases φ at kz = 4π/a. The color represents the phase φ varying from 0 to 2π. f Schematic of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF consisting of six aperiodic Kekulé-distorted triangular photonic crystals with a winding number of +1. The color of the struts represents their widths.

Figure 2a shows the cross section of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF with space-dependent six different modulation phases φ and fixed m0 = 0.024a angularly around the fiber core. From the fiber dispersions with absolute (Fig. 2b) or relative frequency (Fig. 2c), we can observe a single Dirac-vortex topological PCF mode (red line) in a broad frequency range of 164–317 THz (946–1829 nm) located in the topological photonic bandgap induced by the Kekulé distortion. Besides the nontrivial Dirac-vortex topological PCF mode, there also exist trivial index-guided modes (blue line), which usually appear in pairs with different polarizations and are confined wherever there is a local maximum of the strut thickness (equivalent to a high effective refractive index). Here, we only focus on the Dirac-vortex fiber modes inside the topological bandgap, as shown in Fig. 2d, whose field intensity (red color) and electric vector (black arrows) distribution are tightly localized around the fiber core with a C3v symmetry, similar to an azimuthally polarized beam (APB). To facilitate the fabrication of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF, we round off the six sharp corners of the hexagon with a radius of r, as shown in the inset of Fig. 2e. As we increase the radius r, the topological bandgap (the red region represents the minimal bandgap range of φ = 0) gradually decreases but always exists as long as the hexagonal air holes do not transform into circular air holes. Figure 2f shows the eigenmode spectrum of a Dirac-vortex topological PCF with a radius r = 0.3a, from which we can see a Dirac-vortex topological PCF mode (red dot) exists in the topological bandgap, whose field intensity is almost the same as that in Fig. 2d.

a Schematic of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF cross-section. The inset color bar represents the phase distribution of the Kekulé modulation. Simulated fiber dispersion with absolute (b) and relative (c) frequencies, and the red (blue) line represents the Dirac-vortex fiber (index-guided) modes. The intensity (red color) and electric vector (black arrows) distributions of the index-guided modes are shown in the inset of (b). d Simulated intensity (red color) and electric vector (black arrows) distributions of the topological Dirac-vortex fiber modes at kz = 4π/a with the refractive index of silica equal to 1.4491 (ε = 2.1). e Topological Dirac-vortex bandgap as a function of the radius r of the rounded corners at kz = 4π/a. Inset: a unit cell with r = 0.3a and t0 = 0.16a. f Simulated eigenstate spectrum of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF with r = 0.3a. Inset: simulated intensity (red color) and electric vector (black arrows) distributions of the topological Dirac-vortex fiber modes with r = 0.3a at kz = 4π/a.

Experimental realization of a Dirac-vortex topological PCF

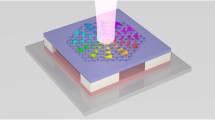

Next, we fabricate the Dirac-vortex topological PCF using the standard stack-and-draw technique (see detailed fabrication process in Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig 2). We first stack four kinds of silica glass capillaries with the same outer diameter d and different inner diameters to form the fiber preform. The combination of silica glass capillaries with inner diameters d1 and d2 (d3 and d4) can be used to construct the unit cell with modulation phase φ = 0, 2π/3, 4π/3 (φ = π/3, π, 5π/3), respectively, which consist of struts with thickness t0 ± m0/2 (t0 ± m0), as illustrated in Fig. 1f (see detailed correspondence between the combination of four different silica capillaries and the varying strut widths in Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig 3). Then we draw the stacked silica glass capillary structure using a fiber drawing tower to produce a uniformly sized Dirac-vortex topological PCF, as shown in Fig. 3a. The difference between the actual and theoretical geometrical parameters is less than 0.1 μm, and the fabricated fiber exhibits the unique properties of Dirac-vortex topological PCF, indicating the stack-and-draw technique is stable and suitable to fabricate the Dirac-vortex topological PCF (see detailed theoretical analysis and simulation results of the fabricated Dirac-vortex topological PCF in Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4).

a Photograph and magnified image of the cross-section of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF. b Schematic diagram of the measurement of Dirac-vortex topological PCF. c The input APB and different polarization states detected in the light manipulating module. d The output Dirac-vortex topological PCF beam and different polarization states detected in the observing module.

We then experimentally characterize the fabricated Dirac-vortex topological PCF. The simplified diagram of the experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 3b (see detailed experimental configuration in Supplementary Note 5 and schematic diagram in Supplementary Fig. 5). The light manipulating module consists of a Sagnac interferometer with a spatial light modulator to generate arbitrarily shaped scalar and vectorial modes as the incident beam. The imaging module, composed of an illuminating source and an imaging system, is placed along the optical field coupling path to monitor the fiber input facet. The observing module is adopted to map the polarization-intensity patterns of the output beam of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF. To match the topological mode supported by the Dirac-vortex fiber, we first use an APB beam created by the light manipulating module as the input beam at 1550 nm, as shown in the left panel of Fig. 3c, which is carefully aligned to the fiber core with beam size reduction by a long focal lens combined with an objective lens to match the effective mode field area of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF. By rotating the polarizer (white arrows), the intensity patterns of the APB turn into two symmetric petals whose orientation is altered with different polarizations, as shown in the right panel of Fig. 3c. The measured intensity pattern of the output Dirac-vortex topological PCF mode is shown in the left panel of Fig. 3d, matching well with the simulation results shown in Fig. 2d, f. When the output Dirac-vortex topological PCF modes are passed through different oriented polarizers (white arrows), the intensity patterns of the Dirac-vortex fiber modes exhibit similar distributions with those of the APB, verifying the unique vectorial nature of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF modes.

To investigate the broadband single-polarization single-mode property of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF, three different input beams, including linearly polarized (LP) Gaussian beam, circularly polarized (CP) Gaussian beam, and the first-order OAM+1 mode, are coupled into the Dirac-vortex topological PCF, respectively, as shown in the left panel of Fig. 4a. The corresponding measured output intensity patterns without and with different oriented polarizer (white arrows) are presented in the right panel of Fig. 4a. It can be seen that the output fields remain the Dirac-vortex fiber mode even under different incident beams. Figure 4b shows the measured relative output power at various wavelengths under different incident beams. For each incident beam, the power variation is about 1 dB, and the measured transmission loss and bending loss of APB remain relatively stable (see detailed loss analysis in Supplementary Note 6 and Supplementary Fig. 6), indicating that the Dirac-vortex topological PCF exhibits a broadband and robust performance across the full communication window (1260–1675 nm). Moreover, the output powers of the Dirac-vortex fiber under APB (blue line) and OAM+1 (red line) beams are much higher than those under CP (brown line) and LP (green line) Gaussian beams, indicating that the more closely the input beam aligns with the topological Dirac-vortex fiber mode, the higher the output power. It is worth mentioning that, although the APB and OAM+1 beams both have similar doughnut intensity patterns, the output power of the Dirac-vortex fiber under APB (blue line) is higher than that under OAM+1 (red line). This can be explained by the fact that the APB beam with azimuthal polarization distribution is closer to the topological Dirac-vortex fiber mode. To further demonstrate the broadband single-polarization single-mode characteristic of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF, we also plot the measured output optical fields without and with different oriented polarizer (white arrows) at different wavelengths, as shown in Fig. 4c. We observe that the output topological fiber modes keep almost the same across the full communication window (1260–1675 nm), verifying that the Dirac-vortex fiber maintains its topological properties over a broad wavelength range. It is worth noting that the measured 415 nm wavelength range (1260–1675 nm) is mainly based on the current available lab conditions. From the trend of the curves in Fig. 4b, there should be a larger bandwidth of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF, as predicted by theory, indicating its superior performance in an ultra-broad wavelength range.

a Measured input (left panel) and output (right panel) field intensity distributions of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF under incident LP Gaussian beam (top row), CP Gaussian beam (middle row), and the first-order OAM+1 beam (bottom row). The white arrows represent different oriented polarizers. b Measured relative output power of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF under incident APB beam (blue line), OAM+1 beam (red line), CP Gaussian beam (brown line), and LP Gaussian beam (green line) across the full 415 nm communication window (1260–1675 nm). c Measured output field intensity distributions of the Dirac-vortex topological PCF without (top row) and with (lower rows) different oriented polarizers (white arrows) at 1260 nm, 1310 nm, 1360 nm, 1460 nm, 1530 nm, 1550 nm, 1565 nm, 1625 nm, and 1675 nm, respectively.

Discussion

In summary, we have experimentally realized a Dirac-vortex topological PCF that supports broadband single-polarization single-mode light transport. We demonstrate that the Dirac-vortex fiber modes are robust against deformation induced in the stack-and-draw fabrication process and different incident beams, making them well-suited for robust optical signal transport. It would also be interesting to experimentally explore Dirac-vortex topological PCF with arbitrary near-degenerate modes by simply increasing the winding number of the vortex and tunable effective mode area by changing the vortex size, as well as its topological protection against fabrication imperfections and bending losses. Our work may enable new fiber applications with robust topological protections, such as high-power topological fiber lasers, quantum networks with protected entangled states of light, and stable optical fiber communications. We envision that enormous new topological phenomena and applications will emerge by introducing non-Hermitian, nonlinear, non-abelian, and noncrystalline effects into topological PCFs.

In preparing our manuscript, we noticed two related works demonstrating topological PCFs based on helically tested twisted fiber33 and disclination defect34.

Methods

Numerical simulations

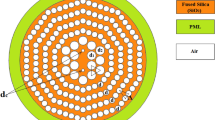

All numerical results presented in this work are simulated using the RF module of COMSOL Multiphysics. In the simulation, since the Dirac-vortex topological photonic crystal is continuous in the z-direction and has no periodicity, all simulations are performed using a two-dimensional structure. By setting a nonzero kz, the transmission characteristics of its Dirac-vortex mode in the z-direction are obtained. The bulk band structures are calculated using a unit cell with periodic boundary conditions in the x and y directions. The Dirac-vortex mode in the Dirac-vortex topological photonic crystal fiber (Dirac-vortex topological PCF) is calculated using a supercell with perfectly matched layers that are applied around the supercell. Meanwhile, by varying the kz, the relationship between the frequency of the Dirac-vortex mode and the propagation constant kz can be derived.

Data availability

All data are available in the manuscript and the supplementary materials in Figshare database at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30105034.

Change history

14 January 2026

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68161-x

References

Knight, J. C. Photonic crystal fibres. Nature 424, 847–851 (2003).

Russell, P. Photonic crystal fibers. Science 299, 358–362 (2003).

Haldane, F. D. M. & Raghu, S. Possible realization of directional optical waveguides in photonic crystals with broken time-reversal symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 013904 (2008).

Wang, Z., Chong, Y., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljačić, M. Observation of unidirectional backscattering-immune topological electromagnetic states. Nature 461, 772–775 (2009).

Lu, L., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljačić, M. Topological photonics. Nat. Photonics 8, 821–829 (2014).

Khanikaev, A. B. & Shvets, G. Two-dimensional topological photonics. Nat. Photonics 11, 763–773 (2017).

Ozawa, T. et al. Topological photonics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 015006 (2019).

Kim, M., Jacob, Z. & Rho, J. Recent advances in 2D, 3D and higher-order topological photonics. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 130 (2020).

Han, N. et al. Topological photonics in three and higher dimensions. APL Photonics 9, 010902 (2024).

Lu, L., Gao, H. & Wang, Z. Topological one-way fiber of second Chern number. Nat. Commun. 9, 5384 (2018).

Lin, H. & Lu, L. Dirac-vortex topological photonic crystal fibre. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 202 (2020).

Pilozzi, L., Leykam, D., Chen, Z. & Conti, C. Topological photonic crystal fibers and ring resonators. Opt. Lett. 45, 1415 (2020).

Makwana, M., Wiltshaw, R., Guenneau, S. & Craster, R. Hybrid topological guiding mechanisms for photonic crystal fibers. Opt. Express 28, 30871–30888 (2020).

Vaidya, S., Benalcazar, W. A., Cerjan, A. & Rechtsman, M. C. Point-defect-localized bound states in the continuum in photonic crystals and structured fibers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 023605 (2021).

Gong, R. R., Zhang, M., Li, H. B. & Lan, Z. H. Topological photonic crystal fibers based on second-order corner modes. Opt. Lett. 46, 3851 (2021).

Huang, H., Ning, Z. Y., Kariyado, T., Amemiya, T. & Hu, X. Topological photonic crystal fiber with honeycomb structure. Opt. Express 31, 27006 (2023).

Lin, H. et al. Topological one-way Weyl fiber. Phys. Rev. B 110, 224435 (2024).

Roberts, N., Baardink, G., Nunn, J., Mosley, P. J. & Souslov, A. Topological supermodes in photonic crystal fiber. Sci. Adv. 8, eadd3522 (2022).

Roberts, N., Baardink, G., Souslov, A. & Mosley, P. J. Single-shot measurement of photonic topological invariant. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, L022010 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Azimuthally and radially polarized orbital angular momentum modes in valley topological photonic crystal fiber. Nanophotonics 10, 4067–4074 (2021).

Kang-Hyok, O. & Kim, K. H. Topological photonic crystal fiber with near-zero flattened dispersion. Opt. Fiber Technol. 73, 103054 (2022).

Lin, Z. K. et al. Topological phenomena at defects in acoustic, photonic and solid-state lattices. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 483–495 (2023).

Gao, P. et al. Majorana-like zero modes in Kekulé distorted sonic lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 196601 (2019).

Ma, J., Xi, X., Li, Y. & Sun, X. Nanomechanical topological insulators with an auxiliary orbital degree of freedom. Nat. Nanotech. 16, 576–583 (2021).

Iadecola, T., Schuster, T. & Chamon, C. Non-abelian braiding of light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 073901 (2016).

Menssen, A. J., Guan, J., Felce, D., Booth, M. J. & Walmsley, I. A. Photonic topological mode bound to a vortex. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 117401 (2020).

Noh, J. et al. Braiding photonic topological zero modes. Nat. Phys. 16, 989–993 (2020).

Gao, X. et al. Dirac-vortex topological cavities. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 1012–1018 (2020).

Yang, L., Li, G., Gao, X. & Lu, L. Topological-cavity surface-emitting laser. Nat. Photon. 16, 279–283 (2022).

Ma, J. W. et al. Room-temperature continuous-wave topological Dirac-vortex microcavity lasers on silicon. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 255 (2023).

Han, S. et al. Photonic Majorana quantum cascade laser with polarization-winding emission. Nat. Commun. 14, 707 (2023).

Cheng, H. B., Yang, J. Y., Wang, Z. & Lu, L. Observation of monopole topological mode. Nat. Commun. 15, 7327 (2024).

Roberts, N., Salter, B., Binysh, J., Mosley, P. J. & Souslov, A. Twisted fibre: a photonic topological insulator. Preprint at: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.13064 (2024).

Zhu, B. et al. Topological photonic crystal fibre. Sci. Adv. 11, eady1476 (2025).

Acknowledgements

J.W. acknowledges the funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grants No. 62125503 and 62261160388, Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province of China under grant No. 2023AFA028, Hubei Optical Fundamental Research Center under grant No. HBO2025TQ004, Technology Innovation Program of Hubei Province (Major Science and Technology Project) under grant No. 2024BAA001, and High Quality Development Special Project of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. Z.G. acknowledges the funding from the Key Research and Development Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology grant no. 2025YFA1412300, National Natural Science Foundation of China under grants No. 62361166627 and 62375118, Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation under grant No.2024A1515012770, Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission under grants No. 20220815111105001 and 202308073000209, and High-level special funds under grant No. G03034K004. P.P.S. acknowledges the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grants No. 62220106006, 62205139, and 62361136584, and Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST under grant No. 2023QNRC001. B.Y. acknowledges the support from the Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under grant No. 2025AFB011.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W., Z.G., Q.H.N., and B.Y. developed the concept and conceived the idea. Q.H.N., B.Y., X.Z., Z.Y.W., Z.G., and J.W. contributed the methodology. B.Y. and H.L. performed numerical simulations. L.S., H.Z., J.L., and L.Z. fabricated the fiber samples. Q.H.N., X.Z., Z.Y.W., M.T.X., H.Z., and J.W. carried out the experiment and performed data analyses. B.Y., Q.H.N., Z.G., and J.W. wrote the manuscript. J.W. and Z.G. revised and finalized the manuscript. J.W., Z.G., B.Y., and P.P.S. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Kwang-Hyon Kim and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niu, Q., Yan, B., Shen, L. et al. Realization of a Dirac-vortex topological photonic crystal fiber. Nat Commun 16, 11051 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65222-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65222-z