Abstract

Assessing the sustainability of plastic chemical recycling requires realistic feedstocks and catalysts designed within sustainability-led frameworks (Plastic-to-X). We link catalyst design and systems analysis to study hydrogenolysis of high-density polyethylene (virgin and bottle caps; Mw = 100–200 kDa). We report Ru–Ni alloy nanoparticles (3–4 nm) supported on titania that yield up to 55% liquid C6–C45 products under optimized conditions, whereas monometallic Ru produces virtually no liquids Operando spectroscopy and simulations reveal structure sensitivity: backbone scission follows dehydrogenation and hydrogenation cycles at defective alloy sites formed in situ. Integrating these mechanistic insights with life cycle and techno-economic analyses indicates profitable processing of plastic caps over the optimal catalyst (2.5 wt% Ru, 5 wt% Ni) with substantially lower CO2 emissions even when using green H2. Furthermore, within the Plastic-to-X framework, we identify a minimum average chain length threshold of C11 for product distributions as a critical design metric to reconcile environmental and economic objectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polyolefins, including high-density polyethylene (HDPE), low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and polypropylene (PP), are by far the largest contributors to plastic pollution, with an annual production rate equal to 350 Mt1. Collected goods are nowadays mechanically recycled into other plastic products with widespread applications delimited by regulations2 or culture3. Efforts to develop chemical routes−now handling < 1% of all plastic waste−are on the rise since they can produce monomers, fuels, chemicals, or materials, opening up other markets while contributing to sustainability4,5,6. Among these routes often applied to other complex feedstocks like biomass7, catalytic hydrogenolysis generates alkane streams (in contrast to hydrocracking, which also produces olefins and aromatics8) at mild conditions (200–300 °C, 10–30 bar H2), making it suitable for the production of gases, fuels, or lubricants9.

After approximately half a decade of development10, polyolefin hydrogenolysis now requires more coordinated efforts from catalyst to process scales to determine conditions for environmental and economic sustainability11,12. A key aspect to consider is the influence of using green hydrogen, which is known to impose economic constraints to other environmentally benign processes13,14,15. Another factor is the potential to access many different product distributions, suggesting a large impact variability across scenarios that has led to a lack of clear target products; an issue that can be summarized as the Plastic-to-X question. Within this complexity, however, liquid range alkanes (C6–C45) may be preferred since they require less hydrogen than gases and currently offer more attractive prices16. This valuable direction aligns with seminal analyses using model polyethylenes (average molecular weight Mw < 100 kDa)16,17. Comprehensive life cycle assessment (LCA) focused on realistic waste streams can be used to identify environmentally preferred routes5,15,18,19,20,21. In the context of plastics, it has been shown that extending the material’s lifetime via chemical recycling can lead to notable emission reductions in the plastics sector at the expense of higher costs when compared to the current fossil-based linear system22,23,24. Thus, pinpointing Plastic-to-X routes that satisfy the economy-environment nexus is relevant to guiding catalyst design.

Supported monometallic ruthenium catalysts are considered reference materials for the hydrogenolysis of model polyolefins, particularly PP25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 and LDPE30,34,35,36,37,38,39, and serve as a benchmark for the less studied HDPE40. With these reports revealing key mechanistic features, realistic feedstocks must now be prioritized to demonstrate the viability of this technology. Recent studies have shown that titania-supported ultrafine Ru nanoparticles exhibit high activity for commercial-grade HDPE (Mw = 200 kDa) and for plastic caps made from it; however, they favor methane formation41. This lack of selectivity control emanates from ruthenium’s intrinsic high activity to promote terminal C–C scission (demethylation, yielding methane) versus the desirable secondary-secondary C–C scission (backbone scission, yielding progressively shorter multicarbon products)28,35.

The addition of a second metal to form atomically controlled bimetallic structures42,43 with enhanced selectivity is a strategy that has proven successful in other processes involving hydrocarbons, such as hydrorefining of acetylene into ethylene44, propane dehydrogenation45, or ethylene epoxidation46. Recent works centered on model LDPE (Mw = 4 kDa, equivalent to ca. C150) have indeed observed reduced demethylation over a Ru-Co single atom alloy47 and Ru-Pt systems48,49. Nickel also shows promise as a ruthenium modifier owing to its low carbon footprint50 and higher preference for backbone scission in the hydrogenolysis of short alkanes51,52,53 and hydrocracking of HDPE54,55,56,57,58 or LDPE59. Nonetheless, Ni displays low activity in monometallic form thereby exhibiting complementary features to Ru. A recent model LDPE hydrogenolysis study using silica-supported Ru-Ni nanoparticles has signaled a reduction in the demethylation degree compared to monometallic Ru, though the lack of synthesis-structure-performance relations precludes its extrapolation to other plastics and catalyst architectures 60. In this regard, the adoption of advanced characterization techniques such as operando spectroscopy may represent a suitable step forward toward enhanced understanding in this field. Following this emerging approach, we integrate catalyst design with system-level analysis to investigate catalyst composition, structure, and performance for HDPE hydrogenolysis. We first develop titania-supported RuNi alloys nanoparticles (ca. 5 nm), yielding up to 16% liquid products under standardized conditions, compared to null for monometallic Ru, and rationalize their operation via operando monitoring of alloy formation coupled to experimental and simulation studies. Further optimization of operating conditions resulted in up to 55% liquid yield for the RuNi catalyst. Bridging these findings with life cycle and techno-economic analyses, we predict environmentally and economically sustainable processing of plastic caps even using green hydrogen. Furthermore, extending this analysis to the Plastic-to-X concept revealed a minimum average chain length threshold of C11 for hydrocarbon products to reconcile economic and environmental demands. Overall, this work highlights how studies aiming at the development of emerging catalytic technologies can largely benefit from a holistic approach.

Results

Selectivity control gained over XRuYNi catalysts in HDPE hydrogenolysis

We devised a sequential impregnation method depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1 and described in detail in the Methods section to synthesize titania-supported nanoparticles with varying ruthenium and nickel content (XRuYNi, where X and Y stand for the wt% of Ru and Ni, respectively). Briefly, YNi catalysts (Y = 0–15 wt%) were first prepared by impregnation of the Ni precursor on TiO2 (anatase), followed by thermal treatment in flowing N2 and reduction in H2. The second impregnation added ruthenium (X = 0–2.5 wt%) to reach the final XRuYNi systems. In the first stage of this study, these catalysts were used to promote hydrogenolysis of commercial-grade HDPE with average molecular weight Mw = 100 kDa (HDPE100) to identify performance trends, and later of the more widely used HDPE200 and plastic caps (Supplementary Table 1). Experiments were performed in a parallel reactor setup and product quantification was possible via gas chromatography, as described in the Methods section and depicted in Supplementary Figs. 2, 3.

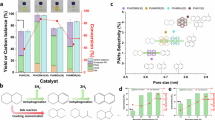

First tests explored the reactivity of XRu and YNi catalysts separately. Monometallic XRu displayed very high conversion (defined as C1-C45 yield), promoting almost exclusively gaseous products even at reduced reaction times of 0.5 h (gray symbols in Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 2). These results align with the high activity and tendency of Ru to promote terminal cleavage41. On the other hand, YNi displayed low activity with a tendency to promote liquid products. Variable Ni contents (Y = 0–15 wt%) and reduction temperatures (573–873 K) enabled a matrix of YNi catalysts with particle sizes between 6 and 20 nm where Ni(111) and NiO(111) facets predominated (Supplementary Figs. 5, 6). Following previous reports using nickel catalysts for other polyolefins54,57,59, catalytic tests revealed very modest conversions even at high Ni contents (e.g., < 10% C1-C45 yield on 15Ni), as reflected in Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 3. Despite the low activity, selectivity toward liquid products (measured as the percentage of the converted fraction into the C6-C45 range) could reach values over 90% (e.g., 5Ni reduced at 573 K, Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 3) and conversion peaked for 5Ni catalysts reduced at 723 K (Supplementary Fig. 8). These results reinforce that monometallic Ni catalysts tend to favor liquid products within their modest activity.

a Yield of C1–C45 products versus Ru content, with lines corresponding to different Ni content. b Yield to liquid products (C6–C45) versus yield to C1–C45 products for catalysts containing 2.5 wt% Ru. c Product distributions from catalysts with 2.5 wt% Ru and 5 wt% Ni prepared by different synthetic routes. More details can be found in the Methods section and metal distributions in Fig. 2. Reaction conditions: P(H2) = 20 bar, T = 523 K, stirring rate = 750 rpm, t = 0.5 h (XRu) or 4 h (XRuYNi), catalyst/plastic = 0.1, feedstock = HDPE100. d Product distributions obtained from different feedstocks (1 = HDPE100, 2 = HDPE200, 3 = caps) over 2.5 Ru and 2.5Ru5Ni catalysts under optimized conditions. Numerical values and reaction conditions are provided in Supplementary Tables 2, 5, 6, 9.

The second stage focused on determining reactivity patterns within the XRuYNi family (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 2). Figure 1a discloses that activity increases with X (Ru content), with catalysts containing 3 and 5 wt% Ni showing similar trends and superior to the 10 wt% case. Conversion and liquid yield were the two main criteria for catalyst selection, leading to the catalysts with 2.5 wt% Ru content being chosen for further analysis. Within this group, 3 and 5 wt% Ni content showed high conversion (80% to C1-C45, with 9 and 16% to C6-C45, respectively, Supplementary Table 2), giving a first indication of the enhancing effect of Ni on the production of liquids. When displaying conversion against liquid yield (Fig. 1b), the 2.5Ru5Ni catalyst was chosen for further investigations as it attained the highest activity out of the XRuYNi materials and the highest liquid yield in the 2.5RuYNi group (83% yield to C1-C45, with 16% to C6-C45), clearly departing from the catalytic behavior of 2.5Ru (97% yield to C1-C5, 3% to C6-C45 after 0.5 h).

The first indication of the need for a close interaction between nickel and ruthenium to achieve high liquid yields came after obtaining exclusively gaseous products over physical mixtures with similar Ru and Ni contents (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 4). After these experiments, alternative synthesis routes were applied to prepare catalysts with 2.5 wt% Ru and 5 wt% Ni, targeting other catalyst structures. These routes are sequential impregnation in the reverse order (first Ru and then Ni) and flame spray pyrolysis, a method proven to achieve controlled dispersion of metals on oxides (Supplementary Fig. 1)61,62. Figure 1c discloses that 2.5Ru5Niinv (inverse impregnation) gave only 5% liquid yield (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Table 5 for other compositions following the same trend), whereas 2.5Ru5NiFSP (flame spray pyrolysis) was almost inactive.

These results revealed structural sensitivity, as evidenced by themicroscopy analysis contained in Fig. 2. The structure of the as-prepared 2.5Ru5Ni system consisted of well-dispersed nanoparticles (3-4 nm on average, Supplementary Fig. 11 for a larger field of view), resembling that of 2.5Ru (Supplementary Fig. 12), with Ru and Ni showing a high degree of co-location (Fig. 2a, b). Catalysts did not exhibit noticeable morphological changes after reaction, suggesting structural stability (Fig. 2c, d and Supplementary Figs. 13, 14 for other compositions). On the other hand, 2.5Ru5Niinv presented a less intimate contact between metals, with aggregates ranging from dozens of nanometers (Fig. 2e) to nanoparticles (Supplementary Fig. 15). In contrast, 2.5Ru5NiFSP displayed an uneven metal dispersion where nickel was highly dispersed while ruthenium formed aggregates of varying sizes (ca. 10–100 nm, Fig. 2f). The structural sensitivity of the reaction was evident from these results, recommending 2.5Ru5Ni as reference material for further exploration. Overall, these results underscore the relevance of matching scalable synthetic methods with optimal catalyst structure, since the simplicity and capacity of a synthesis route is a cornerstone feature for its industial feasibility63.

Representative STEM-EDX elemental maps and HAADF-STEM images of the as-prepared (a, b) and used (c, d) 2.5Ru5Ni catalyst. Reaction conditions are the same as in Fig. 1. Representative STEM-EDX elemental maps of (e) 2.5Ru5Niinv and (f) 2.5Ru5NiFSP after reaction. Additional maps and images are provided in Supplementary Figs. 11–15, 22.

We then proceeded to an initial optimization of reaction conditions to maximize the yield to liquid products on the reference 2.5Ru5Ni by varying reaction time, temperature, hydrogen pressure, stirring rate, and catalyst-to-plastic ratio (Supplementary Fig. 16 and Supplementary Table 6). The maximum liquid yield obtained from these experiments was close to 55% for certain combinations of reaction conditions. Among them, T = 538 K, t = 6 h, P(H2) = 20 bar, stirring rate = 750 rpm, catalyst-to-plastic ratio = 0.1 were chosen due to the simultaneous high conversion (> 90%) and the mentioned high fraction of liquids, demonstrating the relevance of reaction engineering in this process. A parallel optimization for 2.5Ru using lower catalyst amounts resulted in a maximum liquid yield of ca. 25% at 85% conversion (Supplementary Fig. 17 and Supplementary Table 7). The role of Ni as promoter toward liquid products was reinforced when comparing the 2.5Ru and 2.5Ru5Ni catalysts at similar conversion levels, with 2.5Rsu5Ni still showing improved liquid yields (Supplementary Fig. 18). Consecutive tests were performed over 2.5Ru5Ni under optimized conditions to check for reusability (Supplementary Fig. 19a and Supplementary Table 8). While the catalyst remained active, the conversion and liquid yields decreased slightly. This may be due to residual carbon material contributing to the measured catalyst mass (Supplementary Fig. 19b), resulting in the actual amount of catalyst in the reactor being lower. These results suggest that 2.5Ru5Ni can be reused, although further improvements to the recycling procedure are necessary.

Results for hydrogenolysis of virgin HDPE with larger molecular weight (HDPE200) and post-consumer plastic waste (caps) over 2.5Ru5Ni and 2.5Ru using optimized conditions are presented in Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 9. 2.5Ru5Ni displayed a higher liquid yield for HDPE200 and plastic caps than 2.5Ru while maintaining high activity. Hence, the ability of 2.5Ru5Ni to process various HDPE feedstocks warrants a deeper investigation into its catalyst structure.

Formation of RuNi alloys

In view of the distinctive feature of co-location of Ni and Ru over 2.5Ru5Ni compared to the other materials with similar composition (Fig. 2), characterization efforts probed the potential formation of RuNi alloys in XRuYNi systems. Textural characterization indicated similar surface areas and pore volumes for the set of XRuYNi catalysts under study (Supplementary Table 10). X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of as-prepared and used 2.5Ru5Ni did not show reflections corresponding to Ru nor Ni phases, suggesting low crystallinity or small crystallite size (Supplementary Fig. 20). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of 2.5RuYNi materials after reaction revealed the predominance of oxidic Ru and Ni phases, likely due to exposure to air (Supplementary Fig. 21). Elemental analysis disclosed Ni/Ru ratios slightly higher than theoretical ones, suggesting these materials have Ni-rich surfaces. Notably, 2.5Ru5Ni and 2.5Ru5Niinv exhibited similar values (4.8 and 4.3, respectively), pointing to a modest influence of the synthesis method on surface composition (Supplementary Table 11).

For a detailed phase investigation, the fast Fourier transforms (FFT) of micrographs taken from different domains of used samples were analyzed (Fig. 3a). Electron diffraction patterns compatible with the (100), (002), (101), (102) and (110) reflections of the reference Ni1Ru1 as model for hexagonal closed-packed structure (hcp, with d-spacing 2.26, 2.10, 1.99, 1.54, and 1.30 Å, respectively) could be identified. Additional analysis also supported domains with Ni-rich alloys with face-centered cubic (fcc) structure (Ni0.8Ru0.2 taken as a reference) through the identification of reflections matching the (111), (200), and (220) planes with corresponding d-spacing of 2.07, 1.79, and 1.27 Å. These results provided the first support for RuNi alloys formation but required additional evidence due to the existence of other possible crystalline species with similar structures. For instance, metallic Ru hcp shows d-spacing values of identified planes close to those for the Ni1Ru1 alloy (e.g., d-spacing 2.33 vs. 2.26 Å for the (111) plane). Metallic Ni and Ni-rich hcp alloys also suffer from similar constraints (e.g., d-spacing 2.05 vs. 2.07 Å for the (101) plane). Precise identification of alloy compositions thus requires further characterization efforts. Red colored regions in Fig. 3b indicate the possible location of alloys considering these limitations. A more detailed analysis of the images revealed an unidentified semicrystalline phase (yellow colored) that could be assigned to partial amorphization of the TiO2 support at the surface (raw and additional images in Supplementary Fig. 22). D and G bands typical of coke formation (1350 and 1580 cm−1, respectively) were absent in Raman spectra for the 2.5Ru5Ni catalyst, with the spectra measured before and after reaction showing close resemblance (Supplementary Fig. 23).

a HR-TEM images and corresponding FFTs of 2.5Ru5Ni after reaction. Colored lines correspond to different phases, with red indicating the likely location of RuNi alloys (blue: TiO2, yellow: unidentified amorphous phase). Unmodified and additional images are provided in Supplementary Fig. 22. b DRIFTS upon CO adsorption on 2.5Ru5Ni with monometallic counterparts added for reference. Band maxima associated with different CO adsorption modes are indicated. Conditions: mcat = 20 mg, FT = 15 cm3 min−1, T = 298 K. Evolution of bulk electronic structure and oxidation state obtained at different times during operation monitored by (c) normalized X-ray absorption near edge structure spectra corresponding to the Ru K-edge and (d) Fourier-transform EXAFS spectra at the Ru K-edge. Spectra recorded from a metallic ruthenium foil and from ruthenium oxide are added for reference. e Evolution of the main Ru reflection obtained at different times during operation monitored by X-ray diffraction. The symbol * indicates reflections corresponding to TiO2. The extended patterns are provided in Supplementary Fig. 26. The label “Fresh” refers to the state when the catalyst is loaded into the reactor, whereas 0.0 h refers to the moment when nominal pressure and reaction temperature have been reached. Reaction conditions: P(H2) = 20 bar, T = 523 K, catalyst/plastic = 1, feedstock = HDPE100. The subscripts x and y indicate relative metal content.

A second evidence for the existence of RuNi alloys was provided by diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) applied to CO adsorption after H2 reduction of 2.5Ru, 2.5Ru5Ni, and 5Ni (Fig. 3b). The monometallic nickel catalyst showed bands at 2053 cm−1 (linear configuration), 1920 cm−1 (bridge), and 1856 cm−1 (hollow)64,65. The 2.5Ru surface displayed a band centered at 1981 cm−1 to which linear, bridging, and three-folded configurations contribute66,67. Distinctive bands were observed for the bimetallic material, which displayed a first band associated with linear bonding on Ni (with a tail suggesting the contribution from metallic Ru), as well as with a new band centered at ca. 1870 cm−1. These results indicate the emergence of new adsorption sites in 2.5Ru5Ni or modulated electronic structure of Ru/Ni species after alloying, leading to a distinctive interaction with carbon monoxide.

With previous evidence strongly hinting to the formation of alloyed RuNi phases, operando characterization for the 2.5Ru5Ni catalyst revealed the dynamics of alloy formation and its stability under operation. Normalized X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra for the Ru K-edge (Fig. 3c) demonstrated progressive reduction until reaching a stable metallic character after 0.5 h, as revealed by the lower whiteline intensity and the pre-edge shift to lower energies. Results for the Ni K-edge (Supplementary Fig. 24) mimicked this behavior, disclosing Ni in a mainly metallic but partially oxidized form, which seems to be favored by the strong interaction with TiO2. The time evolution of the Fourier transform extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra for the Ru K-edge (Fig. 3d) reveals that alloy formation starts during the temperature ramp (transition from Fresh to 0.0 h) and continues for the first 0.5 h of the reaction (from 0.0 h to 0.5 h), as suggested by the Ru-Ni contribution at ca. 2 Angstrom. After this, the alloying process is completed, and the signal remains stable. XANES and EXAFS analysis for the 2.5Ru catalyst displayed only the reduction of the initial oxide phase without the peak at ca. 2 Angstrom, confirming this interpretation (Supplementary Fig. 25). Complementary results obtained by operando synchrotron X-ray diffraction (SXRD, Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 26) indicated the restructuring and alloy formation within the same period through the gradual shift of Ru reflections over time, also suggesting restructuring into slightly larger nanoparticles or with higher crystallinity prior to the reaction. Statistical analysis of microscopy images of the 2.5Ru5Ni catalyst before and after the reaction exhibited a shift from 3 to 4 nm as the average particle size (Supplementary Fig. 27). These results highlight the value of adapting advanced characterization techniques readily explored in other thermocatalytic reactions to the more experimentally challenging three-phase hydrogenolysis of polyolefin waste.

Complementary analyses for 2.5RuYNi catalysts after reaction added a deeper understanding of their chemical environment (Supplementary Figs. 28, 29). XANES spectra of monometallic and bimetallic catalysts confirmed their predominant metallic character with some minor contribution from oxidic phases (Supplementary Fig. 28). EXAFS spectra at the Ni and Ru K-edge for monometallic systems were consistent with a coordination number (CN) of 9.5 for Ni−Ni in the 5Ni catalyst, and 3.5 for Ru−Ru in the 2.5Ru catalyst (Supplementary Fig. 29 and Supplementary Table 12), coherent with the presence of metallic species68. The spectra from 2.5RuYNi catalysts showed the consistent presence of a peak at ca. 2.2 Å (Ni-Ru) in the Ni K-edge with CNNi−Ru = 1.1 and a peak at ca. 1.9 Å (Ru-Ni) in the Ru K-edge with CNRu−Ni = 2.1, suggesting the formation of alloys (Supplementary Fig. 29). However, these low values indicate a limited Ru-Ni interaction, leading to alloys in the form of clusters or small nanoparticles rather than by dissolution of one phase into the other. The CNRu−Ni increased with the Ni content, suggesting a larger population of Ru alloying with Ni. Taking CNRu−Ni as a proxy for the abundance of alloyed sites, we could correlate liquid yield and CNRu−Ni (Supplementary Fig. 30), revealing that increasing CNRu−Ni leads to higher liquid yields. The decreasing trend observed for 2.5Ru10Ni may be attributed to the presence of poorly active Ni nanoparticles that interfere with the exposure of active Ru sites, as revealed by the emergence of Ni-Ni bonds (Supplementary Table 12). This correlation supports the catalytic role of alloyed sites.

Origin of enhanced liquid formation over RuNi alloys

Herein, we explore temperature-programmed surface reaction (TPSR) experiments and density functional theory (DFT) simulations to probe the cleavage of C–C bonds over monometallic and bimetallic catalysts, aiming to rationalize their distinct catalytic behavior. Heptane is used as a surrogate for HDPE to compare scission of terminal C–C bonds (yielding C1 + C6) and internal ones (yielding C3 + C4 or C2 + C5). As heptane and HDPE possess distinct physical properties, these results may not fully represent the initial stages of the reaction. Nevertheless, heptane is one of the HDPE hydrogenolysis products, allowing these experiments to provide an understanding of the latest stages of the reaction and possible reasons for the different selectivity obtained from Ru and RuNi systems.

TPSR experiments consisted of saturating the catalyst surface with heptane and dosing hydrogen while a temperature ramp was applied (more details in the Methods section). Product formation was continuously monitored by mass spectrometry, with the results displayed in Fig. 4a–c and Supplementary Fig. 31. For the 2.5Ru system, such an approach provided an onset temperature of 383 K for methane formation, while no evolution of propane as a proxy for multicarbon products could be observed to any appreciable extent. This result suggests the intrinsic tendency of monometallic Ru catalysts to promote terminal cleavage, in line with product distributions obtained from HDPE (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). TPSR experiments over 5Ni yielded a parallel evolution of methane and propane starting at higher temperatures (onset 505 K). These insights are also aligned with the lower activity and larger selectivity to liquid products from HDPE (Supplementary Table 3). In contrast to the monometallic systems, 2.5Ru5Ni promoted the early evolution of propane (onset 393 K) over methane (onset 450 K), with other XRuYNi catalysts also featuring this behavior (Supplementary Fig. 31). A control experiment over a physical mixture of 2.5Ru and 5Ni showed results similar to 2.5Ru, confirming the unique behavior of bimetallic catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 32). This experimental indication of a distinctive mechanistic pathway over XRuYNi prompted the exploration of alloyed phases using density functional theory (DFT, PBE + D2) to assess reaction paths associated with C–C and C–H cleavage of heptane.

Temperature programmed surface reaction of heptane as surrogate for HDPE on (a) 2.5Ru, (b) 2.5Ru5Ni, and (c) 5Ni after hydrogenolysis of HDPE100 with signals corresponding to methane (m/z 16), propane (m/z 44) and hydrogen (m/z 2). Dashed lines indicate onset temperatures. Reaction paths computed via DFT for the cleavage of heptane on (d) Ru, (e) RuNi, and (f) Ni models. Schematic energy profiles are shown for the key steps. Steps with reaction energies ΔE ≤ – 0.3 eV are marked in green (exothermic), steps with 0.3 eV > ΔE > – 0.3 eV are depicted in black (thermoneutral), and steps with ΔE ≥ 0.3 eV or high activation energies Ea ≥ 1.6 eV are marked in gray (blocked). Dashed circles indicate species from which hydrogenation into final products occurs. Additional information is provided in Supplementary Figs. 33–36. Ru: blue, Ni: brown.

Based on microscopy characterization and the lack of discernible reflections in XRD analyses (Supplementary Figs. 6, 20, 22), we employed models of defective surfaces including steps and kinks of the Ni(211) termination and defective Ru and RuNi(0001) (Supplementary Figs. 33, 34) to assess reaction paths associated with C–C and C–H cleavage of heptane (Fig. 4d–f, detailed mechanisms and analysis on other surfaces in Supplementary Figs. 35, 36). These defective structures may be transient and thus challenging to identify via experimental characterization techniques, with previous theoretical studies already pointing to their formation under reaction conditions comparable to those found in this reaction69,70,71,72. C–C cleavage on flat or stepped pristine Ru, RuNi, and Ni surfaces was found to be less favored than on defective sites (Supplementary Tables 13, 14). A common feature of all studied defective surfaces is the favored dehydrogenation of heptane over the C–C cleavage due to smaller activation energies (Ea) for C–H breaking. From the thermodynamic standpoint, the reaction energy (ΔE) for C–H bond cleavage and formation lies between − 0.28 and 0.28 eV for the three models Supplementary Fig. 35. This suggests that heptane molecules can readily undergo fast and multiple dehydrogenation and hydrogenation cycles under reaction conditions.

Another commonality among surfaces is the favored cleavage of terminal C–C bonds over the internal scission prior to heptane dehydrogenation. However, when considering the formation of an allyl group by two concomitant dehydrogenations of C7 leading to C7**, the internal C–C scission into C3** + C4 is favored over the terminal C–C cleavage of C7 (C1 + C6) on Ni and particularly on RuNi. In turn, the internal C–C scission is favored on RuNi over Ni, which is in line with TPSR results disclosing that the formation of propane occurs at lower temperatures (Fig. 4a–c). Once the C3** and C4 fragments are formed, C4 is dehydrogenated and C3** is hydrogenated to carry out further C–C cleavages, eventually leading to the formation of C1 products. In contrast, the formation of C3** is unfavorable on Ru due to its high activation energy (Ea = 2.29 eV, Supplementary Fig. 35). Therefore, the preferential cleavage of internal C–C bonds observed in the RuNi and Ni (to a lesser extent) systems is attributed to the stabilization of allyl groups. This mechanism encompassing allylic intermediates may have been elusive in previous mechanistic studies due to the use of shorter reactant surrogates51. Thus, there is a need to revise mechanisms previously proposed for alloys and Ni-containing systems have relied on experimental observations, reaxFF molecular dynamics simulations, or stochastic modeling without providing atomic-level insights (Supplementary Table 15)49,54,60,73,74,75,76.

Overall, our model describes how the Ru system performs heptane hydrogenation and dehydrogenation, followed by successive terminal C–C scissions of C7 and saturated C7-n fragments. These terminal cleavages are favored over any of the internal scission pathways. On the other hand, Ni-containing systems, and particularly the RuNi model, promote the internal C-C scission of heptane via the formation of allyl groups, which can be further cleaved and hydrogenated to form C1 products. Alternative models of RuNi systems exhibit behaviors reminiscent of Ru and Ni (Supplementary Fig. 36), which point to tight structure-performance relationships, in line with the experimental results (Figs. 1, 2).

In a previously-reported screening of metal oxides for hydrogenolysis of polypropylene, titania showed the most marked synergistic effect with Ru, hinting to the possibility of strong metal support interactions (SMSI) besides the promotional effect of Ni33. The electron transfer from TiO2 to the Ru phase has been identified as a likely factor for enhanced selectivity to liquid products in low-density polyethylene hydrogenolysis, though operando characterization would be required to confirm this effect77,78. Additional simulations investigated the structural consequences of SMSI between metals and titania, leading to partial coverage of the Ru surface in view of the semicrystalline phase observed on some regions of the catalyst (Fig. 3a). Our results disclosed an adsorption energy (Eads) of heptane on the anatase TiO2 support used (Eads = – 0.68 eV) which is comparable to its adsorption on metallic Ru, RuNi and Ni surfaces (Eads = − 0.81 to − 0.88 eV). However, the active sites for heptane hydrogenolysis are located on the metal nanoparticles since both internal and terminal C–C cleavage are endothermic on anatase TiO2. These results suggest that TiO2 could facilitate hydrocarbon adsorption and thus promote cleavage on the metallic sites if the Ru-TiO2 interface is preserved. In this regard, adsorption of reactants could stabilize the titania phase and hinder its migration onto the Ru surface, hindering the formation of SMSI architectures.

Extension to consumer-grade feedstocks

Previous analysis has focused on how catalyst structure influences C–C cleavage mechanisms in order to explain the differences in hydrogenolysis behavior. Nevertheless, the nature of the HDPE and the presence of additives may play a key role in influencing performance. Different results were observed in Fig. 1d for hydrogenolysis of HDPE100, HDPE200 and caps over the 2.5Ru5Ni catalyst, showing that the processing of caps was most challenging. In contrast to virgin HDPE100 and HDPE200 polymer pellets, the plastics used in consumer goods also contain additives (e.g., colorants, stabilizers, flame retardants, plasticizers or slip agents for processing, among others). The exact composition of these materials is generally a trade secret, including additives among several thousands of reported compounds79. Hence, a preliminary study was performed using HDPE caps of different colors to explore the influence of additives (Supplementary Table 9). Clear caps showed the highest activity and liquid yield (66% yield to C1-C45, with 42% to C6-C45) over the 2.5Ru5Ni catalyst. Other colors displayed variable performance, with conversion to C1-C45 between 24% and 57% and more modest liquid yields ( < 10%). Similar trends were observed over the 2.5Ru catalyst (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 9), suggesting that the performance variations originate from the different additives. These results highlight the importance of developing catalysts with enhanced robustness toward the diverse compositions of consumer-grade plastics.

DFT simulations were used to provide a first assessment of the interaction between additives and the catalyst surfaces. Herein, we evaluated the interaction of long-chain amides often added to bottle caps as slip agents80. When considering the adsorption of a surrogate molecule (butyramide) on defective surfaces of Ru, RuNi, and Ni, butyramide binds more strongly to the active sites than heptane (Supplementary Table 16). This indicates that the presence of such additives may have a profound effect on catalyst performance for hydrogenolysis reactions due to active site poisoning or preferential reaction, potentially leading to byproducts such as ammonia that could interact with the catalyst surface41.

Plastic-to-X framework

The selectivity control achieved toward liquid products on XRuYNi catalysts led to a detailed analysis of a potential plant for processing 20 t h−1 of plastic caps using green hydrogen. Environmental and economic assessments were based on the plant layout in Fig. 5a, which includes catalyst regeneration and product separation to reach the product distribution obtained with 2.5Ru5Ni (Fig. 1d, see Supplementary Fig. 37 for a version with labeled unit operations according to the detailed description provided in the Methods section). Green hydrogen from water electrolysis powered by either off-shore wind or solar power was chosen as a case study, together with the fossil case based on steam methane reforming. The reference business-as-usual (BAU) equivalent consists of a multi-product system which accounts for the fossil-based production of the respective hydrocarbon products as well as the production and end-of-life of HDPE plastic caps.

a Process flow sheet for recycling 20 t h−1 of plastic bottle caps via hydrogenolysis, including downstream catalyst recycle and product separation. b Global warming potential (GWP) for different sources of hydrogen, i.e., fossil hydrogen from steam methane reforming (fossil) and green hydrogen from water splitting produced in a proton-exchange membrane electrolyzer powered by either off-shore wind power or solar photovoltaic panels. The business-as-usual scenario (BAU) represents the case where caps are produced via the conventional route and incineration is applied as end-of-life treatment, whilst gas and liquid hydrocarbons are separately obtained from oil. c Sankey diagrams for the main contributions to the three scenarios displayed in (b), where the current mixed geographical origin of HDPE is considered. The diagrams illustrate the contribution of processes embedded in the supply chain of the three scenarios (cradle-to-gate), with background data from Ecoinvent 3.891 considering the geography “Global”. Only streams exceeding 5% are represented. d Production cost of the process described in a against the market price of the respective product portfolio. The margin between the total cost and market price indicates the potential profit. FOC = fixed operating costs, CAPEX = capital expenditures, RoW = rest of the world. Breakdowns are available in Supplementary Tables 17–22.

Producing liquid fuels via HDPE hydrogenolysis implies that fossil carbon contained in polymers serves two sequential functions (i.e., virgin plastics and liquid fuels). Compared to the BAU case, which requires fossil carbon to satisfy both markets in parallel, the studied system deploys less fossil feedstock at the production level and embeds less overall end-of-life emissions. Extending the lifetime of the waste polymer via hydrogenolysis delays the carbon release to the atmosphere, thus implying a lower global warming potential (GWP) in a cradle-to-grave scope (Fig. 5b)23. The computation of the GWP for the three cases (fossil, wind, solar) revealed that the fossil hydrogen scenario almost matched the impact of the BAU, while renewable options are more advantageous, with wind yielding ca. 17% less greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Table 17). In all cases, the larger contributors to carbon footprint were the conventional production of ethylene (67–75%), required for HDPE synthesis and based on naphtha steam cracking, followed by catalyst manufacturing (ca. 22%) due to mining and extraction as represented by Sankey diagrams in Fig. 5c and in Supplementary Fig. 38 for the case of BAU (see Supplementary Table 18 for a detailed breakdown). Hydrogen accounted for a reduced share of the carbon footprint, ranging from 11% (fossil) to 2% (wind). Interestingly, the corresponding techno-economic assessments providing total annualized cost of production (TAC, Fig. 5d and Supplementary Tables 19–22) predicted a favorable outcome from the fossil-free alternatives if products are sold at market price, with expected margin for profit ranging from 0.2 to 0.5 $ per kilogram of product (equivalent to 15–25% over the market price, where the composition of one kilogram of product would reflect the C1-C45 fractions obtained from the hydrogenolysis process). We noticed that, in contrast to other sustainable reactions burdened by the high fractional cost of green hydrogen13,14,15,81,82,83, green hydrogen accounted for less than 30% of the total cost for the solar and wind options. Instead, the collection and processing of plastic caps was the major cost contributor (waste HDPE is a trading commodity in Europe, hence the elevated price). This result points to the economic suitability of hydrogenolysis and the use of renewablegreen hydrogen, providing the first example of an environmentally and economically sustainable route for chemical recycling of polyolefins via hydrogenolysis.

Moreover, a sensitivity analysis showed that increasing the cost of hydrogen and waste HDPE separately by 25% would still lead to a positive profit when considering the average selling price for hydrocarbons in 2019 (Supplementary Fig. 39). Additionally, in periods of geopolitical uncertainty, the market price for hydrocarbons could undergo drastic variations—for example, the global average price of natural gas, gasoline, and diesel sharply increased in 2022 as a result of the Russia-Ukraine conflict—which could lead to even larger profits for the chemical recycling case, even when all OPEX parameters are set at their upper bound (Supplementary Fig. 39 and Supplementary Tables 23, 24). Similar sensitivity analysis for the GWP followed the same trend, predicting environmental gains under almost all possible scenarios (Supplementary Fig. 40 and Supplementary Tables 25, 26). Nonetheless, LCA and TEA have limitations that stem from assumptions and modeling choices. As the catalyst material greatly impacts both the hydrogenolysis cost and GWP, identifying more durable catalysts with low deactivation rates is essential for making hydrocarbon production even more sustainable and economically viable (Supplementary Table 27).

The confirmed sustainability of HDPE waste hydrogenolysis for this product distribution leaves the question of which other product portfolios would also enable environmental and economic sustainability, raising the Plastic-to-X question. We tackled this challenge by assessing the GWP and economic margin for a series of 19 randomly generated product distributions, taking the BAU as reference system (Supplementary Table 28). To mimic the series character of this reaction, the distributions followed a lognormal form when gaseous products were more abundant, and a Gaussian distribution when liquid products were predominant (examples in Fig. 6a). The set of distributions were selected to span a variety of average chain lengths since this parameter later served as a descriptor for identifying main trends. The GWP and economic margin results can be found in Fig. 6b–d for the three considered sources of hydrogen (numerical values in Supplementary Tables 29–31). Since hydrogen consumption increases as the average chain length of the products decreases, an inverse relation between GWP and chain length was to be expected, as reflected in Fig. 6b–d. Calculations show that hydrogenolysis using wind hydrogen always displays environmental gains versus BAU, whereas solar hydrogen requires an estimated minimum chain length of C5 to this end, a threshold that rises to C10 for fossil hydrogen.

a Examples of randomly generated product distributions based on lognormal (top) and Gaussian (bottom) distributions with indication of their average chain lengths (Supplementary Table 28 for all distributions). Evaluation of hydrogenolysis of plastic caps using hydrogen with either (b) fossil, c wind, or (d) solar origin, showing the gain in GWP compared to the equivalent BAU process (squares) and the margin for profit (circles) per kilogram of total C1–C45 products versus the average chain length of the randomly generated product distributions (see details in the Methods section). The primary y-axis (left-hand side) quantifies the GWP gains obtained by switching from BAU operation to the hydrogenolysis process that generates the same product portfolio. A positive gain indicates that we reduce the GWP of end-products relative to their BAU respective. The secondary y-axis (right-hand side) indicates the margin for profit obtained with the respective process. This unit quantifies the difference between the revenues obtained by selling the different products at market price and the cost of production. Negative values indicate that the cost of production is higher than the achievable revenues, while a positive margin translates to the potential profit obtained through the corresponding process. Minimum average chain lengths to achieve positive GWP gains and profit are indicated. For example, in the case of solar hydrogen, both environmental and economic feasibilities are achieved for chains longer than C11. Breakdowns are available in Supplementary Tables 29–31.

The economic analysis disclosed higher breakeven average chain lengths than for the GWP evaluations, with a consistent threshold of C10-C11 across wind, solar and fossil options. Since sustainability encompasses both environmental and economic dimensions, we can thus provide a first guideline describing how hydrogenolysis of HDPE requires average chain lengths at least in the upper range of the gasoline fraction (C6-C12), regardless of the type of hydrogen used. A more detailed analysis of Fig. 6b–d shows a strong dependence on the average chain length at small values due to the sharp increase in market price from low-value gases (C1-C5) to light and heavy liquid fractions (Supplementary Table 19). This also leads to the plateau in GWP gains and economic margin observed at large average chain lengths, where the motor oil fraction contribution dominates. Overall, these results can guide catalyst design and reaction engineering efforts by establishing performance targets.

Discussion

In this study, we perform an integrated investigation encompassing catalyst design and systems engineering for the hydrogenolysis of realistic HDPE waste. We first impart selectivity control by developing alloyed RuNi nanoparticles (3-4 nm on average) supported on titania, yielding up to 55% liquid yields, compared to null for monometallic Ru, and with 2.5 wt% Ru and 5 wt% Ni as optimal composition. Operando studies disclosed the formation dynamics of Ru-Ni alloys upon exposure to operating conditions, highlighting the need to incorporate advanced characterization techniques used inother fields in thermocatalysis to chemical recycling of plastics. Experimental and simulation efforts disclosed performance-structure sensitivity in these bimetallic catalysts and their intrinsic ability to promote internal (based on allylic intermediates) vs. terminal C–C bond cleavage through a mediating dehydrogenation-hydrogenation cycle. When bridging these insights with environmental and techno-economic analyses, the sustainability of this technology for processing plastic caps using green hydrogen emerged. Furthermore, the contextualization into the Plastic-to-X framework revealed that product distributions with an average chain length in the upper range of the gasoline fraction (C6-C12) or larger allow uniting environmental and economic feasibility. This work highlights the sustainability potential of polyolefin hydrogenolysis and represents a guideline for future catalyst design efforts.

Methods

Catalyst synthesis

Commercially available titanium oxide (anatase, Sigma Aldrich) was calcined in static air (5 h, 773 K, 5 K min−1) prior to its use as support during the synthesis. All catalysts were prepared by dry impregnation and sieved to < 0.2 mm particle size before use. For the monometallic Ni and Ru catalysts, only one supported metal is stated when referring to the catalyst. Bimetallic catalysts are denoted as XRuYNi, XRuYNiinv, or XRuYNiFSP depending on the method used for preparation (Supplementary Fig. 1). The content of each metal is reported in front of the respective metal as a percentage by mass (X wt% Ru and Y wt% Ni).

Monometallic Ru catalysts

In a typical procedure, 0.500 g of titania was dry impregnated with 0.855 cm3 ruthenium nitrosyl nitrate (Ru(NO)(NO3)x(OH)y, x + y = 3) in diluted HNO3 (0.015 g cm−3, Sigma Aldrich) to obtain 2.5 wt% ruthenium content. The mixture was stirred (353 K, air) with a magnetic stirring bar to evaporate the solvent. Residual solvent was removed by vacuum drying (12 h, 353 K, 80 mbar). The catalyst was thermally treated in flowing nitrogen (1 h, 573 K, 5 K min−1).

Monometallic Ni catalysts

Nickel (II) nitrate hexahydrate (Sigma Aldrich) was dissolved in distilled water to prepare a 0.5 g cm−3 precursor solution (0.1 g cm−3 Ni concentration). Typically, 0.500 g of titania was dry impregnated with 0.153 cm3 (3 wt% Ni), 0.261 cm3 (5 wt% Ni) or 0.550 cm3 (10 wt% Ni) precursor solution to obtain the desired metal content. Residual solvent was removed by vacuum drying (12 h, 353 K, 80 mbar). The catalyst was thermally treated in flowing nitrogen (3 h, 573 K, 5 K min−1) and subsequently reduced under flowing hydrogen (5% hydrogen in argon, 3 h, 723 K, 5 K min−1).

Bimetallic RuNi catalysts

0.500 g of the monometallic Ni catalyst was dry impregnated with 0.855 cm3 ruthenium nitrosyl nitrate (Ru(NO)(NO3)x(OH)y, x + y = 3) in diluted HNO3 (0.015 g cm−3, Sigma Aldrich) to obtain 2.5 wt% ruthenium content. The mixture was stirred (353 K, air) with a magnetic stirring bar to evaporate the solvent. Residual solvent was removed by vacuum drying (12 h, 353 K, 80 mbar). The catalyst was thermally treated in flowing nitrogen (1 h, 573 K, 5 K min−1).

Bimetallic RuNiinv catalysts

Typically, 0.500 g of the monometallic Ru catalyst was dry impregnated with 0.153 cm3 (3 wt% Ni), 0.261 cm3 (5 wt% Ni) or 0.550 cm3 (10 wt% Ni) precursor solution to obtain the desired metal content. Residual solvent was removed by vacuum drying (12 h, 353 K, 80 mbar). The catalyst was thermally treated in flowing nitrogen (1 h, 573 K, 5 K min−1).

Bimetallic RuNiFSP catalysts

2.5Ru5NiFSP with nominal Ru and Ni contents of 2.5 wt% and 5 wt% was prepared by flame spray pyrolysis by pumping the mixture of precursors in the desired molar ratios for Ru (Ru(III)acetylacetonate, ABCR, 99%), Ni (Ni(II) 2-ethylhexanoate, STREM Chemicals), and TiOx (2-ethylhexanoate, ABCR, 6.4 wt% Ti) through a 0.4 mm needle at a flow rate of 6.0 cm3 min−1 and nebulized by a 6.0 L min−1 flow of oxygen at 1.5 bar. The mist was ignited by a supporting flame generated using 2.4 L min−1 of oxygen and 1.2 L min−1 of methane. Such particle-generating flames reach average flame temperatures of 2500–3000 K, with very fast cooling rates (ca. 106 K s−1). The resulting mixed-metal oxidic nanoparticles were collected on a glass fiber filter (GF/A-6) and used without further treatment.

Catalyst characterization

High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) and energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy was carried out on a double-corrected microscope JEM-ARM300F (GrandARM, JEOL) operated at an acceleration potential of 300 kV (electron gun: cold-field emitter; ΔE ≈ 0.35 eV). In addition, HAADF-STEM and EDX analyses were also conducted using an FEI Titan Themis transmission electron microscope, equipped with a probe aberration corrector and a SuperX EDX system, operated at 300 kV. Catalyst powder was dispersed in ethanol onto a perforated carbon foil supported on a copper TEM grid.

Nitrogen physisorption at 77 K was carried out using a Micromeritics TriStar II analyzer. Prior to the measurements, samples of ca. 0.1 g were degassed at 473 K under vacuum (10 Pa) for 12 h. The specific surface area (SBET) was estimated using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method, while the total pore volume (Vpore) was obtained at a relative pressure p/p0 = 0.98.

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy was performed on a Rigaku ZSX Primus IV spectrometer equipped with a 4 kW Rh source and LiF (200), Ge, PET, and RX26 analyzing crystal detectors.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was conducted using a Rigaku SmartLab diffractometer with a D/teX Ultra 250 detector using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.1541 nm) and operating in the Bragg-Brentano geometry. Data was acquired in the 20–80° 2θ range with an angular step size of 0.025° and a counting time of 1.5 s per step.

Raman spectroscopy was performed using a Horiba: LabRAM HR Evolution UV-VIS-NIR confocal Raman system comprising a 325 nm HeCd laser with 2.5 mW power, a 40 × objective lens with a numerical aperture of 0.95 (Nikon PlanApo), and a fiber-coupled grating spectrometer (1800 lines per mm). Spectra were collected in a single run with 60 s acquisition time.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted with a Physical Electronics Quantera SXM spectrometer. Monochromatic Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV) generated by an electron beam (15 kV and 49.3 W) was used to irradiate the samples with a spot size of 200 μm. The finely ground samples were pressed into indium foil (99.9%, Alfa Aesar) and then mounted onto the holder. During the measurement, electron and ion neutralizers were operated simultaneously to suppress undesired sample charging. High-resolution spectra were obtained by using pass energies of 55 eV while the C 1 s signal at 284.8 eV was used for calibration. CasaXPS (Casa Software Ltd.) was used for all calculations, and relative sensitivity factors used for quantification were taken from the instrument. All spectra were deconvoluted into Gaussian-Lorentzian components with the application of the Shirley background.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) was conducted at the Swiss-Norwegian beamlines (SNBL, BM31) of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF). The X-ray beam was collimated using a double-crystal liquid nitrogen-cooled Si(111) monochromator84. A transmission geometry configuration was used for the analysis under ex situ conditions, using a one-element Si SDD detector with Peltier cooling. For the absolute energy calibration for XAS measurements, metallic Ni and Ru foils were measured. Finely ground samples were mixed with cellulose binder, pressed into a pellet, and then mounted onto the holder. Scanning was performed for both Ni (between 8230 and 9320 eV) and Ru edges (between 22020 and 23100 eV), and the step size was set to 0.5 eV, with a scan duration of 150 s. The beam size was set to 3 × 0.2 mm (horizontal × vertical). The resulting spectra were energy calibrated, background corrected, and normalized using the Athena program from the Demeter software suite85. k2-weighted extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra were fitted in the optimal k- and R-windows using the Artemis program. An amplitude reduction factor (S02) of 0.81 and 0.85 were determined for Ni and Ru, respectively, using Ni, NiO, Ru, and RuO2 foils.

Operando XAS and XRD experiments were performed at the same beam station, following this procedure: (i) the catalyst was mixed with HDPE100 in a 1:1 mass ratio and loaded in the quartz capillary with diameter of 1.5 mm, (ii) the sample was placed on the sample holder and flushed with pure H2 and pressurized to 20 bar, (iii) measurements were performed at room temperature (RT) for the fresh catalyst, (iv) heated to 523 K with 5 K min−1 and maintained for 2 h, (v) the system was naturally cooled down to RT and measurements were performed for the used catalyst. XRD data were collected with a Pilatus3 X CdTe 2 M low background detector using a LaB6(111) channel-cut monochromator, set at a wavelength of 0.319162 Å (ca. 39 keV). Averaging procedures and azimuthal integration were performed with the pyFAI software using NIST LaB6 powder as a standard. XRD data were averaged over 60 s.

Temperature-programmed surface reaction (TPSR) measurements were conducted with a Micromeritics AutoChem II 2920. Signals were acquired with pre-equipped thermal conductivity detectors and an attached Pfeiffer Vacuum OmniStar GSD 320 O mass spectrometer with Quadera software. Prior to measurements, samples of ca. 70 mg were saturated with 0.5 mL n-C7H16 and dried (293 K, 3 h, air) to remove weakly adsorbed heptane. In the subsequent surface reaction experiment, diluted hydrogen gas (5 vol% hydrogen in nitrogen) was dosed by a set of Bronkhorst digital mass flow controllers while applying a heating ramp (313 K to 1073 K, 10 K min−1). The effluent stream of the instrument was monitored online via the Quadera software to analyze the evolution of the reactants (H2 and n-C7H16) and C1-C7 products.

Diffuse reflectance infrared fourier transform spectroscopy upon CO adsorption (CO-DRIFTS) was performed using a Bruker Invenio S Fourier transform infrared spectrometer. The as-prepared catalyst (ca. 15 mg) was first dried in the cell and purged with He (20 cm3 min−1) for 0.5 h at 473 K to remove impurities. After cooling down to room temperature, the sample was exposed to CO (10% CO in He) for 1 h to achieve a CO-saturated surface. The sample was then flushed with He for 1 h to remove all remaining gas phase and physiosorbed CO. Spectra were continuously monitored and collected every 0.5 min.

Catalyst evaluation

Hydrogenolysis reaction

The catalysts were tested in a parallel pressurized batch reactor set−up (BuchiGlasUster, Switzerland) consisting of three 50 cm3 stainless steel reactors (Supplementary Fig. 2). Each reactor was equipped with an electrical heating jacket, active cooling unit (chilled water system), mechanical stirring, temperature/pressure control systems and gas sampling lines (connected to pure hydrogen and nitrogen). Typically, 0.5 g of polyethylene pellets (Mw ~ 100 kDa, Sigma Aldrich) and 0.05 g of catalyst were added to a glass inset, and the combined weight was recorded. The inset was then placed inside the reactor. Prior to starting the experiment, the reactor was flushed with nitrogen and hydrogen before being pressurized with hydrogen to the desired pressure (20 bar, unless stated otherwise). The reaction parameters and individual steps were programmed into the SYSTAG Flexsys software before starting the experiment, and during the reaction, instantaneous measurements of the temperature, pressure and stirring torque were recorded to monitor the experimental conditions. The reaction mixture was heated and mechanically stirred for a set reaction time after having reached the set temperature (523 K, 750 rpm and 4 h, respectively, unless otherwise specified). Subsequently, the reactor was cooled to ambient temperature with circulating chilled water.

For experiments involving the optimization of reaction conditions, the temperature, pressure, stirring rate and reaction time were set directly in the SYSTAG Flexsys program. Each set of conditions was tested in separate experiments. Different catalyst-to-plastic ratios were achieved by varying the amount of catalyst (0.025 g or 0.05 g) while keeping the HDPE amount constant (0.5 g).

Catalyst reusability

Catalyst reusability was evaluated for the 2.5Ru5Ni catalyst at optimized reaction conditions. As described above, each experiment was performed with 0.5 g of polyethylene pellets (Mw ~ 100 kDa, Sigma Aldrich) and 0.05 g of catalyst. Approximately 0.03–0.04 g of catalyst could be recovered (20–40% loss) in each experiment, such that several experiments were performed to collect enough used catalyst for subsequent runs (i.e., three experiments for run 1, catalysts recovered and combined, two experiments for run 2). After reaction, the liquid and solid products remaining inside the inset were dissolved in dichloromethane (50 mL), sonicated (303 K, 0.5 h) and centrifuged for 15 min at 6000 rpm (4430 × g). Part of the liquid was filtered using a syringe for analysis with GC − FID, while the remaining liquid was decanted to recover the catalyst. Residual solvent was removed by vacuum drying (6 h, 353 K, 80 mbar). The catalyst was thermally treated in static air (2 h, 673 K, 5 K min−1) to restore accessibility to active sites, which had been reduced by carbon deposits and/or structural changes. The treated catalysts were sieved to < 0.2 mm particle size before use.

Product analysis

The gaseous products were collected from the headspace of the reactor by connecting a sampling cylinder and analyzed using a gas chromatographer (HP Agilent 6890 GC) equipped with an Agilent J&W PoraPlot Q column (25 m × 0.53 mm × 20 μm) and flame ionization detector (FID) (Supplementary Fig. 3a). H2 was used as the carrier gas, and a heating ramp (308 K to 573 K, 5 K min−1) was applied while the inlet and FID were held at fixed temperatures of 573 K and 473 K, respectively. GC − FID calibration for C1 to C5 products was performed using a standard refinery mixture bottle (Agilent P/N: 5080–8755, Agilent Technologies Inc.) and following a procedure reported elsewhere86. Typically, the mixture bottle was connected to the GC inlet, and the line was flushed for two minutes to remove any residual gases. The sample was analyzed three independent times using the same GC method, and the response factors of each gas were calculated based on their concentrations and the corresponding peak areas in the FID chromatogram.

After each experiment, the glass inset was removed from the reactor and weighed to determine the total amount of gas formed (mgas). Equation (1) gives the yield of each gas (Ci), where Ai is the GC − FID peak integration of a paraffin with i carbon atoms and m0 is the initial mass of plastic used in the reaction. Yields are reported for methane (C1) and other gases (C2-C5).

The liquid and solid products remaining inside the inset were dissolved in dichloromethane (50 mL), sonicated (303 K, 30 min) and filtered using a syringe before analysis with GC − FID. Samples were analyzed in an HP Agilent 6890 GC (Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA) equipped with an HP DB-5 HT column (15 m × 0.25 mm × 0.10 μm). A 1 μL aliquot of the sample was injected and a heating ramp was applied (313 K to 648 K, 4 K min−1), while the FID was held at a fixed temperature of 613 K. Initial and final hold times were set at 2 and 10 min, respectively. GC − FID calibration was performed using a certified reference mixture of C7 − C40 n-alkanes in hexane (1 mg cm−3, Sigma-Aldrich) and extrapolated up to C45 owing to the similar response factor of C25-C40 compounds in the motor oil range87. A blank run using only dichloromethane (DCM) was performed prior to each measurement to clean the column. The baseline shift observed in the second half of the program is attributed to the column bleed Supplementary Fig. 3b.

The liquid yields were quantified using MATLAB (MathWorks Inc., USA). The baseline was found to be approximated well by the msbackadj function, tightly following the baseline of the measurement. A baseline fit was performed for each measurement due to the instrumental drift. For product quantification, the baseline function was subtracted from the signal, and trapezoidal integration was performed on the resulting signal. Calculations were performed on a mass basis, such that Eq. (2) gives the yield of a certain liquid fraction (Ci-Cj) for paraffins with i-j carbon atoms, where Ai-j is the peak integration area across the i-j range, RFi-j is the corresponding response factor, VDCM is the solvent volume used for dilution (50 mL), and m0 is the initial mass of plastic used in the reaction (500 mg).

Equation (2) quantified yields for C6-C12, C13-C20 and C21-C45 products (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Separate areas were obtained across the time ranges [1.45, 14.7], [14.7, 33.7] and [33.7, 80] (in minutes) to consider the gasoline, diesel and motor oil contributions, respectively. Response factors of 0.2796, 0.2186 and 0.1174 mg mL–1 area–1 were used for gasoline, diesel and motor oil, respectively.

Remaining C46+ hydrocarbons and solid products could not be characterized quantitatively through GC − FID due to the maximum temperature settings on the column and were thus considered as solid residue, as shown in Eq. (3). This includes long-chain waxes as well as (unreacted) polyethylene.

Overall, conversion refers to the yield of products in the C1–C45 range and selectivity refers to the fraction of each product within the C1-C45 range, always relative to the starting amount of polyethylene used in the reaction.

Density functional theory

Density functional theory (DFT) simulations were performed with the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP 5.4.4). 88,89. The density functional of choice was Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)90 supplemented with Grimme’s D2 dispersion approach and our reparametrized values for metals91,92. Valence electrons were described with planewaves with a kinetic cut-off energy of 450 eV, while inner electrons were represented with projector augmented-wave (PAW) core potentials93,94. We used the Monkhorst-Pack method to generate a \(\Gamma\)-centered mesh with a reciprocal grid size narrower than 0.041 Å−1 to sample the Brillouin Zone95. Spin polarization was included in all simulations involving Ni due to the magnetic character of this element. Inpust and outputs for all DFT simulations can be found online in the ioChem-BD repository (Data Availability section)96,97.

Lattice parameters for different bulk models of Ni, Ru, and RuNi materials were optimized with a kinetic energy cut-off of 800 eV. The energy required for a Ni atom to change from face-centered cubic (fcc) to hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structures is 0.03 eV per atom, while Ru requires 0.12 eV per atom for the reverse transformation. This suggests that Ni may adopt a hcp structure when alloyed with Ru. We used a RuNi bulk from the hexagonal crystal system and space group 187 according to the Materials Project database98.

Based on the optimized bulk materials Ni-fcc, Ru-hcp, and RuNi, different slab models were built to represent the catalysts under study (Supplementary Figs. 33, 34) containing steps and kinks due to the small size of the metal nanoparticles (Fig. 2)99. We employed a p(2 × 6) slab with 18 atomic layers of the Ni(211) facet and p(6 × 6) slabs with 6 atomic layers of the (0001) surfaces of Ru and RuNi (considering both Ni- and Ru-terminated models, as shown by RuNi, RuNi-b, RuNi-c, and RuNi-d). Half of the atomic layers (the outermost ones) were allowed to relax, while the bottommost layers were fixed to their bulk positions. Moreover, a vacuum region of 15 Å was added between slabs and a dipole correction along the z axes was included100. In the case of Ru and RuNi models, only half of the atoms in the outermost layer of the (0001) termination were included to represent a stepped surface. These models were employed to assess key steps for the hydrogenolysis of heptane as a surrogate for HDPE, as displayed in TPSR experiments (Fig. 4a–c). The heptane molecule in the gas phase and clean surfaces were used as thermodynamic sinks. The climbing image nudged-elastic band (CI-NEB)101 was employed to locate the transition states, and their nature was confirmed by computing numerical frequencies with a step size of ± 0.015 Å.

Process modeling of HDPE hydrogenolysis

HDPE hydrogenolysis was assessed based on real experimental data on conversion and selectivity of the 2.5Ru5Ni catalyst. Aspen Plus v12 was used with the PENG-ROB property method, which deploys the Peng-Robinson cubic equation of state and is suitable for non- or mildly polar mixtures containing hydrocarbons and light gases102. Bottle caps were modeled as a polyolefin mimicking consumer-grade polymers with a molecular weight of 200 kDa and an average input flow of 20 t h−1, following assumptions by Salah et al.103.

The process flowsheet is included in Fig. 5a of the main text and Supplementary Fig. 37 and considers current experimental results for conversion and selectivity and detailed downstream separation blocks. A 5% catalyst loss was assumed after ten consecutive runs. (Supplementary Table 27). HDPE (25 °C, 1.013 bar) and hydrogen (40 °C, 20 bar) are fed to the process in stoichiometric amounts before being mixed (M1) and heated to reaction conditions (250 °C) in H1. The reactor (R1) was modeled with the RStoic reactor block. It operates at 250 °C and 20 bar, with the 2.5Ru5Ni catalyst enabling the conversion and selectivity described in Supplementary Table 3 for the same conditions. The outlet stream is cooled down to 40 °C (C1) and depressurized to 1.013 bar (V1) before passing through a filter in the presence of n-hexane to regenerate the catalyst, which is recycled into the reactor (R1). The product mixture, which also comprises the used solvent and the unreacted raw materials, is sent to the downstream processing section of the process. To recover the liquid fraction in the filtered stream, the latter undergoes a flash separation, before being recompressed to 25 bar (via the pump P1 for the liquid stream and the compressor K1 for the vapor phase). The excess hydrogen, still present in the compressed stream, is recovered in a pressure swing adsorption unit (PSA). The remaining streams are mixed (M3) and cooled down to 40 °C (C2). The five hydrogenolysis products, i.e., methane, light gases, gasoline, diesel, and motor oil, are separated with high molar purity in six distillation columns (D1–D6), modeled with the DSTWU column model. The unconverted fraction of HDPE is recovered in the reboiler of column D6 and recycled into the reactor. The solvent used to regenerate the catalyst (n-hexane) is recovered in the condenser of column D4, recycled into the mixer M2 and then fed to the catalyst filter. Due to losses in the process, mainly in the recovery of products, a make-up of n-hexane is necessary. Heat integration was performed with Aspen Energy Analyzer v12 to design the corresponding heat exchange network integrating hot and cold process streams.

Techno-economic and life cycle assessment

To assess the economic and environmental potential of implementing hydrogenolysis of polyolefins at an industrial scale, a techno-economic and environmental assessment was carried out using the model described above. Mass and energy balance data were obtained from the corresponding simulation to calculate the cost and build the life cycle inventories (LCI).

The techno-economic assessment (TEA) considered the total annualized cost (TAC) of producing the end-product portfolio and was calculated based on the cost factors and correlations in Sinnott and Towler104. The variable operating cost (VOC) includes the costs of raw materials, electricity, utilities and waste treatment operations, whilst the TAC is calculated as a function of the VOC, the fixed operating cost (FOC) and the annualized capital cost (ACC, Supplementary Table 32), as shown in Eq. (4) below. The used values for parameters a, b, and n can be found in Supplementary Table 33 for each equipment type104.

The ACC was computed considering a plant lifetime of 25 years and a 10% interest rate. Both the FOC and ACC were derived from the capital expenditures (CAPEX), which were calculated using cost correlations from Chapter 6 in Sinnott and Towler104. The CAPEX corresponds to the purchased equipment cost (C) multiplied by the installation factor, where the purchased equipment cost is calculated following Eq. (5) based on a sizing factor (S) and parameters (a and b) that are specific to each equipment unit.

The inside battery limits cost (ISBL) is then calculated based on the purchasing cost (C) and typical installation factors for “fluids-solids” processes, according to the framework described by Sinnott and Towler104 of all plant equipment ( j = 1,…, M) following Eq. (6) below. These factors account for piping ( fp = 0.6), equipment material ( fm = 1 for carbon steel and 1.3 for 304 stainless steel), equipment erection ( fer = 0.5), electrical installation ( fel = 0.2), instrumentation and control (fi = 0.3), civil engineering services ( fc = 0.3), structure and building services ( fs = 0.2), and lagging and paint services ( fl = 0.1). Here we consider that all equipment is made of carbon steel except for the reactor R1 and the PSA unit, which are made of 304 stainless steel as they involve H2.

The total fixed capital cost (FCC) is then estimated from the ISBL to account for offsites (OS), design and engineering (D&E) and contingency (X) as shown in Eq. (7) below104.

The annualized capital cost (ACC) is then calculated from the FCC and the annual capital charge ratio (ACCR), which in turn corresponds to the fraction that must be paid out each year to fully repay the capital investment cost, including principal and accumulated interest (i) over the plant lifetime (n). Both these units are calculated following Eqs. (8) and (9) below, and according to the variables described in Supplementary Table 32.

Finally, the FOC is determined from the ISBL, FCC and cost of labor (CL), following the approach described by Sinnott and Towler104. It comprises expenses linked to operating labor (CL), supervision ( fsup = 0.25), salary overheads ( fso = 0.6), maintenance ( fmt = 0.05), property taxes and insurance ( fti = 0.02), rent of land ( frl = 0.02), environmental charges ( fec = 0.01), and general plant overheads (fpo = 0.65). It is calculated following Eq. (10) below. The CL corresponds to four operators (three shift positions plus one operator for the solid catalyst regeneration section) with an average salary of USD 60'000 per person.

All values of the TEA are expressed in USD 2022. Cost data was adapted to the selected year with the Chemical Engineering plant cost index (CEPCI) whenever not directly available. The CAPEX results are displayed in Supplementary Table 34 and the cost parameters used in the VOC are displayed in Supplementary Table 35.

The LCA followed the methodology described in the ISO 14040/14044 standards105,106 with the Ecoinvent 3.8 database107 as background system and the outputs of the process simulations as foreground data. The global warming potential (GWP) of the different scenarios was calculated with the IPCC 2021 method for climate change which accounts for greenhouse gas emissions (including hydrogen and biogenic CO2) as well as short-lived climate forces for a 100-year timespan. The calculations were carried out in Brightway v2.4.3108. The assessment aims to evaluate the life cycle impacts linked to the production, consumption and end-of-life of one kilogram of end-product obtained, in a cradle-to-grave scope. Thus, the life cycle inventories (LCI) were defined for multi-product systems that account for the production and end-of-life of HDPE as well as the production and consumption of a portfolio of petrochemicals that substitute the products of hydrogenolysis in the global market. For the hydrogenolysis scenarios, the LCIs of the different end products consider the complete life cycle of HDPE, which includes the extraction of raw materials, the HDPE production steps, use phase, waste collection and sorting, chemical recycling via hydrogenolysis, and the end-of-life of the hydrogenolysis products. The latter is direct combustion for all hydrogenolysis products, given that they are used as fuels or products that are present in combustion engines (motor oil). The business-as-usual (BAU) equivalent consists of a multi-product system which accounts for the fossil-based production of the respective hydrocarbon products, as well as the production and end-of-life of HDPE (here, it was assumed that 30% of the waste polymer is incinerated and 70% landfilled). Supplementary Tables 36–38 contain the LCI data used in the LCA calculations.

Framework to map feasible product distributions from hydrogenolysis

The techno-economic and environmental assessments were systematically repeated for a series of hypothetical product distributions at the outlet of the hydrogenolysis reactor (R1 in Supplementary Fig. 37). This analysis was carried out to identify possible catalysts that would enable a margin for profit while reducing the environmental burden generated by the analogous BAU system.

The framework consists of five steps executed in series. First, 19 hypothetical product distributions (ten normal and nine lognormal) were randomly generated based on inferred parameters, which ensure a feasible range for the products, i.e., all distributions were truncated between C1 and C50, the means were sampled between C1 and C40, and the standard deviations could range between ±2 and ±13 carbon atoms. In the second step, the conversion data for the hypothetical catalysts was derived from the obtained histograms and plugged into the RStoic reactor (R1) iteratively before each adapted simulation was run. The columns were adjusted to still meet the product specifications while yielding different amounts of them. More precisely, the distillation columns were activated or deactivated (by-passed) considering the specific product distributions in each case (i.e., the absence of methane at the outlet of R1 implied that D1 was by-passed). All columns operated following the same specifications as in the 2.5Ru5Ni case, considering a 0.999 recovery of the corresponding light key component and a 0.001 recovery of the heavy key component in the condenser; total condensers with liquid distillates were assumed. Only active columns were considered in the CAPEX and OPEX calculations for the different cases. In the third step, the heat exchanger network for each adapted flowsheet was then derived with Aspen Energy Analyzer v12.

The CAPEX, OPEX, and TAC were calculated based on the mass and energy flows, following the described TEA methodology. Finally, the LCA was performed and the results of each product distribution were compared to their analogous BAU system, which corresponds to the conventional production of the issued product portfolio (i.e., C1, C2-C5, C6-C12, C13-C20, C21-C45) in the respective amounts as obtained in the reactor that follows the hypothetical product distributions, as well as the production and end-of-life of HDPE.

Data availability

The datasets generated in this study are available in the Supplementary Information and at Zenodo (10.5281/zenodo.14290553). Data related to density functional theory simulations have been deposited at the ioChem BD (https://doi.org/10.19061/iochem-bd-1-361). Data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

This study did not generate new code.

References

Statista.com. Production forecast of thermoplastics worldwide from 2020 to 2050, by type. Available at: https://shorturl.at/B5Aw0. (2024).

EUR-Lex. Commission Regulation (EU) 2022/1616 of 15 September 2022 on recycled plastic materials and articles intended to come into contact with foods, and repealing Regulation (EC) No 282/2008. 3–46 Available at: https://shorturl.at/otvhn. (2022).

Spack, L. Use of Recycled Plastics in Food Industry: How to Manage Global Compliance? (2022).

Martín, A. J., Mondelli, C., Jaydev, S. D. & Pérez-Ramírez, J. Catalytic processing of plastic waste on the rise. Chem 7, 1487–1533 (2021).

Li, H. et al. Expanding plastics recycling technologies: chemical aspects, technology status and challenges. Green. Chem. 24, 8899–9002 (2022).

Korley, L. T. J., Epps, T. H., Helms, B. A. & Ryan, A. J. Toward polymer upcycling—adding value and tackling circularity. Science 373, 66–69 (2021).

Mäki-Arvela, P., Martínez-Klimov, M. & Murzin, D. Y. Hydroconversion of fatty acids and vegetable oils for production of jet fuels. Fuel 306, 121673 (2021).

Mäki-Arvela, P., Kaka khel, T. A., Azkaar, M., Engblom, S. & Murzin, D. Y. Catalytic hydroisomerization of long-chain hydrocarbons for the production of fuels. Catalysts 8, 534 (2018).