Abstract

The Arctic Ocean has undergone accelerated warming and a marked decline in sea ice over recent decades. Yet, the response of the biological pump—a critical mechanism for atmospheric carbon sequestration—remains poorly understood. Here, we develop a satellite-derived dataset (2003–2022) to identify a regime shift in the Arctic biological pump. Between 2003 and 2012, the strength and efficiency of the biological pump increased rapidly, primarily driven by sea ice decline. However, from 2013 to 2022, this trend plateaued, coinciding with stabilized sea ice conditions and increased phytoplankton biomass. Earth system model simulations (1850–2100) support the observed link between biological pump enhancement and sea ice loss, and project a future regime shift towards a weakened biological pump under nearly ice-free conditions, associated with shifts in phytoplankton community structure. These findings underscore the Arctic’s vulnerability to climate-driven changes, with far-reaching implications for Arctic carbon sequestration and ecosystem stability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arctic sea ice decline represents a striking indicator of global climate change1,2, driving significant alterations in ecosystem processes, including the production and deep-ocean export of organic carbon, or, as it is popularly known, carbon sequestration3. The Arctic Ocean (AO) serves as a significant sink for atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2), accounting for up to 12% of global oceanic carbon uptake4,5,6, despite comprising less than 5% of the global sea surface area. Much of this CO2 uptake is driven by the biological pump, which transfers carbon from the surface ocean and its linked atmosphere to the deep waters7. While the strength and efficiency of the biological pump strongly influence the degree of carbon export to the deep ocean, its response to rapid sea ice loss in the AO remains poorly understood. In particular, Arctic sea ice extent has drastically declined in recent decades, characterized by earlier seasonal retreats and reduced ice thickness1. However, the impacts of sea ice decline on the biological pump remain debated. Some studies suggest that sea ice decline reduces vertical carbon export in the AO due to increased stratification and diminished nutrient supply8,9,10, while others argue that sea ice retreat enhances the biological pump’s strength through improved light penetration, an extended growing season, and intensified ocean circulation11,12,13,14. A key reason for these conflicting findings is that observational datasets predominantly consist of temporally sparse measurements, offering only limited coverage of the dynamic ocean environment.

Resolving these conflicting statements has proven challenging due to the region’s spatial and temporal variability and the scarcity of consistent observations. Ocean color satellite-based observations have been utilized to continuously monitor the variations in the biological pump by evaluating net primary production (NPP)15. However, this method depends on empirical links between the export efficiency (e-ratio) and satellite-derived NPP and sea surface temperature (SST)16, which vary regionally across the global oceans, leading to discrepancies in carbon export estimates. Alternatively, Earth system models (ESMs) have been employed to monitor alterations in the biological pump under climate change conditions17,18,19; however, in most ESMs, carbon export is parameterized almost exclusively via particle sinking, whereas other mechanisms, such as zooplankton vertical migration and the subduction or vertical redistribution of dissolved and suspended organic carbon, are largely omitted19,20. Therefore, a fundamental question remains unanswered: has the biological pump in the AO strengthened or weakened in recent decades as a result of diminishing sea ice extent?

To address this critical knowledge gap in AO carbon cycle research, we present a satellite-based dataset of net community production (NCP) spanning 2003–2022. NCP, representing the net accumulation of organic carbon in the surface ocean after accounting for heterotrophic respiration by consumers, effectively reflects the export flux of carbon from the surface under steady-state conditions and across large spatial scales18,21. A portion of the exported carbon can be transferred to the deep ocean and stored there, mediated by several biological pump processes such as gravitational settling of particles, zooplankton-driven vertical transport, and the subduction or mixing of organic material22. Accordingly, NCP serves as a key proxy for biological pump strength23,24,25. Normalized by NPP, the e-ratio (NCP/NPP) provides an index of carbon export efficiency16,23,26. Although ship-based measurements have offered foundational insights10,27,28,29, their limited spatiotemporal coverage has hindered robust assessments of long-term trends, particularly in the AO, where no decadal-scale, high-resolution monitoring existed prior to this study30. Here, we overcome these limitations using a satellite-based framework, enabling systematic quantification of spatial variability and multi-decadal changes in the Arctic biological pump.

In this work, we estimate NCP using a semi-analytical algorithm that integrates satellite observations, reanalysis products, machine learning techniques, and biogeochemical models (see Methods; Supplementary Figs. 1–7, Supplementary Tables 1–2). Additionally, we use NPP to assess variations in the e-ratio. We employ five established models to map NPP distribution, including VGPM31, Eppley-VGPM32, CbPM33, CAFE34, and a locally calibrated Arctic Ocean Productivity Model (AOPM)35 (Supplementary Figs. 8, 9). Our analysis focuses on the period from late spring to late summer (June–September) because sea ice typically begins to melt in early June and refreezes in October for the majority of the AO, and the mixed layer remains relatively stable during this period. We statistically analyse trends in NCP, NPP, and the e-ratio over the past two decades across the entire AO and its 11 subregions (Fig. 1a) in relation to sea ice dynamics. We incorporate ESM simulations to extend the analysis from 1850 to 2100, capturing the evolution of the impacts of warming and sea ice loss on the biological pump. Collectively, these datasets provide critical insights into the historical trajectory and the future response of the Arctic biological pump under ongoing climate change.

a Map of the AO showing the shelf seas and central basin. Climatological summer means of b NCP and c e-ratio for 2003–2022. Summer mean d NCP and e e-ratio across the AO and its subregions. In a, subregions are outlined by thin black lines and classified as Basin, Inflow shelves (Chukchi Sea, Barents Sea, and Norwegian Sea), Interior shelves (Beaufort Sea, East Siberian Sea, Laptev Sea, and Kara Sea), or Outflow shelves (Greenland Sea, Baffin Bay, and Canadian Archipelago). Land areas are shown in grey. Inflow and outflow currents are shown as red and blue arrows, respectively. The color bar represents bathymetry in the AO in (a). White pixels in (b) and (c) denote missing data. In the boxplots d and e, the upper and lower bounds represent the first and third quartiles, the whiskers show the minimum and maximum values, while the centre line and open squares indicate the median and mean values, respectively.

Results and Discussion

Biological pump strength and efficiency

On average, the AO exhibits a mean NCP of 8.81 ± 2.03 mmol C m−2 d−1, surpassing the upper limit of NCP observed in other open ocean regions (Supplementary Table 3) and highlighting its significant contribution to carbon cycling in the global ocean. The area-integrated NCP is approximately 55.24 ± 15.27 Tg C yr−1, consistent with a previous estimate of 61 ± 23 Tg C yr−1 within the mixed layer depth (MLD)7. The mean e-ratio across the AO is 0.12, indicating that about 12% of the NPP is exported out of the MLD through the biological pump.

Both NCP and the e-ratio exhibit pronounced subregional heterogeneity (Fig. 1b,c and Supplementary Fig. 10). The highest NCP values (9.62 ± 2.12 mmol C m−2 d−1) occur in inflow shelves, driven mainly by enhanced phytoplankton biomass stimulated by nutrient-rich subarctic inflows36,37. Outflow (7.83 ± 2.83 mmol C m−2 d−1) and interior shelves (6.10 ± 2.69 mmol C m−2 d−1) also exhibit relatively high NCP. Conversely, notably low NCP values appear in river-dominated coastal zones on interior shelves (e.g., the Kara and Laptev Seas), primarily due to substantial inputs of terrigenous dissolved organic matter38, most of which is remineralized to dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) in coastal areas39. The e-ratio shows a broadly similar spatial pattern (Fig. 1c). The highest e-ratio values, exceeding 0.5, occur in inflow regions such as the Northeast Barents Sea and Chukchi Sea shelves, whereas the lowest e-ratio values (<0.05 or 5%; Fig. 1e) are observed in interior shelf coastal zones. These low values reflect high NPP combined with intense respiration, fueled by terrestrial organic carbon inputs and rapid organic matter turnover in the shallow shelf40 (Fig. 1b,c and Supplementary Fig. 9). Interestingly, the central basin, despite its low NPP (Supplementary Fig. 9b), shows moderate NCP (5.26 ± 4.40 mmol C m−2 d−1) and relatively high e-ratio values (reaching up to 0.40, with a mean of 0.13). These patterns are likely driven by phytoplankton blooms near the ice edge41,42, highlighting the pivotal role of the marginal ice zone in deep-ocean carbon sequestration.

Trends in the biological pump

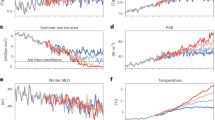

Satellite observations over the past two decades reveal distinct trends in the strength of the Arctic biological pump (Fig. 2a,d), with rapid intensification during the first decade (2003–2012) followed by a marked slowdown in the second decade (2013–2022). During the first decade, NCP increased at 0.067 mol C m−2 yr−2, three times the second decade’s rate of 0.021 mol C m−2 yr−2. This acceleration was strongest in the Kara and Barents Seas, where NCP rose by 0.093 and 0.076 mol C m−2 yr−2, respectively (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 10). Moderate but significant increases also occurred in the Norwegian, East Siberian, and Greenland Seas. In contrast, other subregions, including the Laptev and Beaufort Seas, showed no significant trend (P > 0.05). In 2013–2022, only the Kara Sea maintained a significant increase, while NCP growth elsewhere stalled or reversed (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 10).

a Long-term trend of NCP (mol C m–2 yr–1) from 2003 to 2022. NCP trends (mol C m–2 yr–2) during b 2003–2012 and c 2013–2022. d Long-term trend of e-ratio (dimensionless) from 2003 to 2022. The e-ratio trends (yr–1) during e 2003–2012 and f 2013–2022. Trend, Kendall’s tau-b correlation coefficient, and significance test (P value) between years and NCP or e-ratio are shown in (a) and (d). Solid and dashed lines in (a) and (d) indicate Sen’s slope estimates for NCP and e-ratio during different periods.

The e-ratio generally tracked NCP variations across the AO, independent of the choice of NPP products (Supplementary Fig. 11). It increased widely in the first decade (0.0117 yr−1 overall) but stabilized in the second decade (Fig. 2d). Early increases were concentrated in the Kara (0.0147 yr−1), Barents (0.0135 yr−1), East Siberian (0.0068 yr−1), and Greenland (0.0132 yr−1) Seas, and detectable—though often not significant—in most other shelves (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 10). By contrast, in 2013–2022 localized gains occurred only in the Kara Sea and parts of the central basin’s marginal ice zone, while previously increasing regions such as the East Siberian, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas declined (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 10).

Biological pump trends linked to sea ice decline

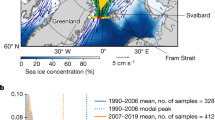

By controlling the availability of light, nutrients, and habitat space essential for primary producers in the AO43, sea ice plays a pivotal role in ecosystem functioning. Accordingly, changes in sea ice exert profound influences that may restructure Arctic marine ecosystems. Between 2003 and 2022, Sea Ice Concentration (SIC) declined significantly while open water duration (OWD) increased (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 12a), coinciding with NCP changes. From 2003 to 2012, SIC declined rapidly, and NCP increased significantly, particularly in interior and outflow shelves such as the Kara, Laptev, and northern Barents Seas, as well as the Beaufort Sea (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 12b). In contrast, from 2013 to 2022, the rate of SIC loss slowed, leaving concentrations relatively stable. In this period, SIC decreased slightly—but not significantly—in the eastern interior shelves (East Siberian, Laptev, and Kara Seas), while a slight increase was observed in the western shelves (Beaufort Sea) (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 12c). Correspondingly, the biological pump remained stable (Fig. 3d).

Spatial distributions of summer SIC trends (% yr–1) during a 2003–2022, b 2003–2012, and c 2013–2022. d Time series of SIC, NCP, and e-ratio during 2003–2022. Time series of e chlorophyll-a (Chla) and NCP, f SIC and mixed layer depth (MLD), and g MLD and NCP during the same period. Analyses are separated into two periods: 2003–2012 and 2013–2022. Black dots in (a–c) indicate statistically significant changes at the 5% level (P < 0.05). Pearson’s correlation coefficients (Pearson’s r) and corresponding P values are reported in (d–g) to quantify the strength of the relationships.

Correlation analysis further supports the coupling between biological pump variations and sea ice changes over the past two decades. A robust negative correlation was identified between NCP and SIC variation (r = −0.72, P < 0.001) during 2003–2022. This correlation was predominantly driven by the strong association between NCP and SIC during the first decade. For instance, NCP was significantly correlated with SIC (r = −0.77, P < 0.01) and OWD (r = 0.81, P < 0.01) in the first decade (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 12d); however, these correlations were not significant in the second decade. In contrast, during 2013−2022, a significant positive correlation emerged between NCP and chlorophyll-a (Chla) (r = 0.77, P < 0.01, Fig. 3e). The trend in the e-ratio closely followed NCP variation, exhibiting significant correlations with SIC (r = −0.77, P < 0.01) and OWD (r = 0.81, P < 0.01) during 2003–2012. However, no significant correlations were observed between the e-ratio and either sea ice variation or Chla during the second decade. These findings indicate a shift in the primary drivers of the biological pump over the past two decades.

Physical–biological coupling driving shifts in the biological pump

Mechanistic evidence supports the observed coupling between declining SIC and increasing NCP during the early melting period. The expansion of open water areas caused by reduced SIC44,45,46, combined with more frequent high-latitude storms47, markedly weakened sea surface stratification. This transition shifted the upper ocean from a meltwater-stratified regime9—driven by surface accumulation of low-salinity meltwater, strong stratification, a shallow MLD, and limited vertical exchange under higher SIC—to a mixed-layer-homogenized regime under lower SIC, where wind-driven turbulence48 disrupts stratification, deepens the MLD, and enhances vertical mixing49. Reduced SIC is also linked to intensified eddy activity along shelf break regions11,50, which facilitates the downward transport of organic matter11. Together, these physical changes create favorable conditions for organic carbon export to the deep ocean.

Significant correlations between SIC or OWD and MLD (Fig. 3f; Supplementary Figs. 12e and 13d), along with a positive correlation between NCP or e-ratio and MLD during the active melting period of 2003–2012 (Fig. 3g; Supplementary Figs. 13e and 14), support the hypothesis that reduced upper ocean stability, reflected by MLD deepening under declining SIC, was the key physical driver of enhanced carbon export (higher NCP and higher e-ratio). In the shallow mixed layer of the AO (typically 5–30 m in summer51,52,53), even small MLD changes can substantially strengthen the biological pump and carbon export efficiency through multiple pathways. For example, MLD deepening entrains nutrient-rich bottom waters, alleviating nutrient limitations in strongly stratified surface layers (see Supplementary Fig. 15). Nutrient-deficient phytoplankton exhibit disproportionate productivity gains from small nutrient inputs54,55. Reduced SIC also markedly increases light penetration into the water column1. Deeper mixing redistributes phytoplankton out of the surface light-inhibition zone and optimizes photosynthetic efficiency under enhanced light conditions. Enhanced nutrient supply56, combined with optimized photosynthesis, supports higher primary production in marginal shelves44,45,57 and drives a shift in phytoplankton communities toward large-celled taxa such as diatoms58,59,60,61. Larger phytoplankton enhance carbon export because their faster sinking accelerates POC transfer to depth62. Rapid sinking shortens particle residence time in the euphotic zone and limits remineralization by heterotrophs63. As a result, a larger fraction of primary production was transferred to the deep ocean as sinking particles64,65 (i.e., the e-ratio; Fig. 2d), contributing to higher NCP. The link between phytoplankton size structure and carbon export explains the rise in NCP, despite no significant increase in NPP during this period44,45 (Supplementary Fig. 9d). Together, these findings provide mechanistic, spatial, and statistical evidence that sea ice decline was the primary driver of the intensified biological pump in the first decade, acting through regionally coherent physical (MLD-mediated mixing) and ecological (size-structure shift) pathways.

The coupling between NCP and phytoplankton biomass during the second decade aligns with expectations, as SIC remained relatively stable, reflecting post-melt stage conditions. During this stage, NCP was mainly driven by nutrient availability and primary production, consistent with mechanisms observed in the open ocean10,27,28,29. Variability in NPP during this decade was largely influenced by increased phytoplankton biomass, resulting from the intensified inflow of nutrient-rich waters from the subarctic ocean—a process commonly referred to as “Atlantification” or “Pacification”66. This process strengthened the coupling between NCP and Chla (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 13c). The lack of a significant correlation between the e-ratio and Chla is not unexpected, because the simultaneous enhancement of NCP and NPP, due to increased phytoplankton biomass, suppressed variability in their ratio (i.e., the e-ratio), thereby weakening the correlation.

We further applied a structural equation model67 (PiecewiseSEM) to quantify the causal pathways linking sea ice decline, mixed-layer processes, and biological production (Fig. 4). Results showed that SIC exerted the strongest influence on both NCP and the e-ratio (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 13a,b), confirming sea ice decline as the dominant driver of biological pump trends during the rapid melt period of 2003–2012. During this period, SIC decline affected NCP and the e-ratio through both direct and indirect pathways. These effects were mediated by biogeochemical processes, including MLD deepening and nutrient entrainment (path coefficient: β = 0.818, P < 0.001, Fig. 4a). In contrast, during 2013–2022, the model revealed a driver chain dominated by biological adaptation, in which sea ice-driven processes weakened, nutrient supply and biomass formed a positive feedback loop, and biomass (Chla) directly promoted NCP (path coefficient: β = 0.715, P < 0.05, Fig. 4b). These results imply that the primary drivers of the biological pump shifted over the past two decades, transitioning from sea ice dynamics to phytoplankton biomass as the dominant factor.

a Results for 2003–2012. b Results for 2013–2022. Blue boxes indicate physical factors, and orange boxes indicate biological factors. Solid black arrows denote positive relationships, while dashed red arrows denote negative relationships. Numbers on the arrows show significant standardized path coefficients, and asterisks indicate significance levels (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

To further elucidate changes in NCP from satellite observations, we extended our analysis over the 251-year period using an ESM. Simulations were performed for a historical period (1850–2014, BHIST) and a high-emission future scenario (2015–2100, BSSP585) using the most recent release of the Community Earth System Model version 2 (CESM2) (see Methods). Although CESM2 has been used previously to simulate Arctic sea ice68, snow69, clouds and precipitation70, and sea surface pCO271, here we extend its application to NCP modeling. To better represent plankton diversity and size structure in NCP simulations, we incorporated the Size-based Plankton Ecological TRAits (SPECTRA) model72 into the Marine Biogeochemistry Library (MARBL) framework73 (Supplementary Table 4).

Model results corroborate satellite observations, showing NCP regime shifts closely tied to SIC variability (Fig. 5a). In the early industrial period (1850s–1960s), NCP gradually increased under high and stable SIC conditions (Fig. 5b). From the 1970s to the 2020s, NCP rose sharply, coinciding with rapid sea ice decline (Fig. 5c). However, as sea ice continues to retreat, NCP is projected to decline from the 2030s, with a substantial drop between the 2080s and 2100 (Fig. 5 d). Strong correlations between NCP and SIC persisted throughout the entire period. The model also showed significant long-term shifts in phytoplankton community structure (Supplementary Fig. 16a). Prior to the 1970s, phytoplankton community composition remained stable (Supplementary Fig. 16b). Between the 1970s and 2020s, large phytoplankton expanded while smaller phytoplankton declined, coinciding with higher NCP. Conversely, from the 2030s to 2100, large phytoplankton are projected to decrease, and smaller phytoplankton are expected to increase, paralleling the anticipated decline in NCP. CESM2 simulations revealed strong spatial coherence between trends in NCP and large phytoplankton (Supplementary Fig. 17), highlighting the role of phytoplankton community structure in modulating the Arctic biological pump. For instance, regions with strong NCP increases (e.g., Barents Sea, Chukchi Sea) coincided spatially with high abundances of large phytoplankton under contemporary conditions (1981–2020). Under future projections (2021–2100), both NCP and large phytoplankton biomass are projected to decrease (Supplementary Fig. 17c,f), suggesting a potential “miniaturization” of the phytoplankton community under sustained low-SIC conditions. This shift toward smaller cells favors remineralization in the euphotic zone74, reducing export efficiency and decoupling biomass from carbon sequestration. Together, satellite observations and model simulations indicate that the biological pump in the AO is highly responsive to sea ice change. Notably, the model projects another regime shift starting in the 2030s, when SIC drops below 40%. In some regions, satellite-derived NCP and the e-ratio data suggest that this shift may already be underway (Supplementary Fig. 10).

a Variations in NCP and SIC from 1850–2100. Trends in NCP and SIC during b the historical (1850–1970), c the modern (1970–2030), and d future periods (2030–2100). In a, blue, yellow, and red indicate distinct regimes of the trends in NCP and SIC. Thin and bold lines represent annual and five-year running means of NCP and SIC, respectively. In the upper-right corner of the panel, long-term changes in NCP and SIC are indicated by Sen’s slope and significance test (P value) derived from the Mann-Kendall test. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (Pearson’s r) and associated P value for the NCP-SIC relationship are shown in the lower-left corner of the panel.

The AO is particularly vulnerable to climate change, as evidenced by the rapid decline in sea ice. However, the responses of the biological pump to these changes have remained contentious, largely due to a lack of continuous observations20,43—until now. By integrating advanced algorithms, satellite observations, and numerical modeling, this study offers a comprehensive assessment of changes in NCP and the e-ratio in response to sea ice loss.

Our analysis elucidates and quantifies the critical impact of substantial sea ice retreat on the biological pump over the past two decades, with projections suggesting its continued influence into the future. This advance was enabled by a framework that integrates a machine learning-based approach to generate high-precision observational datasets, enabling more accurate quantification of the biological pump. Unlike traditional methods—typically based on fixed or temperature-dependent export efficiencies16,23,25,64,65,75,76 and associated with considerable uncertainties20—our framework estimates export as the balance between community production and respiration. This method captures a broader range of export processes, encompassing both advective-diffusive and non-advective-diffusive pathways19. Furthermore, by incorporating key biogeochemical parameters such as pCO2, DIC, and NCP, our methodology enables a more integrated understanding of the biological pump’s response to climate variability. Given its demonstrated performance in the AO, this framework could be applied globally in conjunction with numerical models.

The regime shift in the biological pump reported here aligns with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s call for improved understanding of regime shift dynamics in polar regions77. The observed transition from sea ice—dominated to phytoplankton biomass—dominated biological pump dynamics is further supported by ESM simulations, which project a continued decline in the biological pump’s strength as sea ice diminishes. The agreement between satellite-based observations and model predictions from the 2000s to the 2020s underscores the robustness of these projections. A weakened biological pump is likely to induce a positive feedback loop in climate change, thereby accelerating further decline. Additionally, the biological pump contributes significantly to alleviating ocean acidification on Arctic continental shelves46,78. Its weakening may intensify ocean acidification beyond the projected rise in sea surface pCO271. This intensified acidification would adversely affect calcifying organisms, such as shellfish, and disrupt broader marine ecosystems, highlighting the urgency of addressing these cascading impacts in the Arctic Ocean and beyond.

Methods

Data sources and processing

Satellite observations, field measurements, and numerical models were used to construct a spatially and temporally continuous NCP dataset, following the procedure outlined in Supplementary Fig. 1. Underway sea surface pCO2 observations in the AO were compiled from a variety of international sources, including the Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas79 (SOCAT v.2022; http://www.socat.info), the Global Ocean Data Analysis Project80 (GLODAPv2.2022; https://glodap.info/), the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC; http://www.godac.jamstec.go.jp/darwin/e), the Chinese National Arctic and Antarctic Data Center (Chinese NAADC; https://datacenter.chinare.org.cn/) and the United States Geological Survey database (USGS; https://pubs.er.usgs.gov). Only summer (June–September) pCO2 measurements from 2003 to 2022 were used to calibrate and validate the retrieval model for estimating sea surface pCO2 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Ultimately, the dataset includes over 456,000 sea surface pCO2 measurements collected during 193 cruises, accompanied by corresponding SST and sea surface salinity (SSS) records (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Note that the SOCAT v.2022 and GLODAPv2.2022 datasets provide the fugacity of CO2 (fCO2) rather than pCO2. To ensure comparability, data were standardized to pCO2. Values originally reported as fCO2 were converted to pCO2 based on in situ SST measurements using Eq. (1)27:

The conversion from fCO2 to pCO2 introduces a negligible error, as the observed difference is smaller than the ±2 μatm measurement precision. Each sampling point was assigned to one of eleven subregions and four functional topographies for regional analysis45,81 (Supplementary Dataset 1). Subregional boundary maps and geolocation data (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Dataset 1) are provided to ensure reproducibility of regional assignments. In this study, MODIS/Aqua summer climatological SST data were used to divide the Nordic Sea into the Greenland Sea and the Norwegian Sea82. For the sake of brevity, this will not be reiterated below.

MODIS/Aqua L3 SST data (R2019.0), including daily, 8-day, and monthly composites at a 4-km resolution, were acquired from the NASA Ocean Color website (https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/l3/). Satellite-observed SST was compared with concurrent underway SST observations within the same spatial grid. In the AO, the root mean square error (RMSE) between satellite-observed and in situ SST measurements was 1.08 °C, with a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.87 (see Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). A linear correction was applied to the satellite-observed SST data (Supplementary Fig. 3a) to reduce bias in subsequent analyses.

We obtained MODIS/Aqua L2 remote sensing reflectance (Rrs) products (R2022.0) from the NASA Ocean Color website (https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/) to develop a localized Chla retrieval algorithm, calibrated using the in situ Chla dataset provided by Lewis and Arrigo.81. The locally calibrated Chla algorithm yielded an RMSE of 0.21 mg m–3, a MAPE of 39.6%, a Slope of 0.72, and an R2 value of 0.65 (see Supplementary Fig. 4). This algorithm was then applied to daily MODIS/Aqua imagery to estimate daily Chla concentrations across the AO. Pixels flagged for potential errors—such as atmospheric correction failure (bit 0), land (bit 1), high or saturated radiance (bit 2), stray light contamination (bit 8), and cloud/ice presence (bit 9)—were masked in daily imagery to maintain data quality. Daily data were then aggregated to generate 8-day and monthly composites.

Daily and monthly data of SSS and MLD, provided at a spatial resolution of 0.083° × 0.083° (~8 km), were compiled from the Copernicus Marine Environmental Monitoring Service (CMEMS) global ocean reanalysis product (https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/GLOBAL_MULTIYEAR_PHY_001_030/)83. The reanalysis dataset provides multi-decadal, three-dimensional fields of ocean physical properties, generated by integrating satellite and in situ observations into a numerical ocean modeling framework, thus ensuring consistent and homogeneous representations of the ocean state over time83. Prior to incorporating the SSS product into the retrieval model, reanalysis SSS values were compared with field measurements, demonstrating strong consistency. Although overestimation was noted at low SSS levels (<25 psu) (Supplementary Fig. 3c), the correlation (R2 = 0.79, P < 0.001) between measured and reanalysis SSS was significant, with most residuals below 2 psu and an RMSE of 1.91 psu (see Supplementary Fig. 3d). As waters with SSS below 25 psu account for a minor proportion of the AO, a simple regression equation was applied to regions with higher salinity (>25 psu) for correction to minimize error propagation. Near-weekly xCO2 data at a 0.05 sine-of-latitude resolution were sourced from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Earth System Research Laboratory (ESRL) Greenhouse Gas Marine Boundary Layer (MBL) Reference84 (http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/mbl/).

Model construction of pCO2 and assessment (Step 1)

Monthly SST, xCO2, Chla, SSS, and MLD were utilized to reconstruct long-term sea surface pCO2 in the AO. SST was used to capture thermodynamic effects, xCO2 was employed to reflect the forcing of sea surface pCO2 by rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations, Chla served as a proxy for the biological effects on sea surface pCO2, and SSS and MLD were used to characterize the physical mechanisms of horizontal and vertical seawater mixing, respectively. All environmental variables were resampled to a 4-km × 4-km spatial resolution to ensure consistency.

The matchup process between field-measured variables and satellite observation-based products was conducted using consistent spatial and temporal criteria85,86. Specifically, 8-day composites of MODIS/Aqua Chla and SST were applied for matchup with field measurements, thereby reducing cloud contamination and increasing the number of valid pairings. For each in situ sea surface pCO2 measurement, valid satellite data within a 3 × 3-pixel window were extracted and averaged to reduce sensor-related and algorithm-derived noise87. Matchups were retained only when at least five valid pixels were present within the window, and the variance among these pixels did not exceed 10%86. To reduce the influence of skewness arising from their multi-order variability, Chla and MLD were log-transformed (base 10) prior to analysis88. We compiled 90,623 in situ–satellite matchup samples of sea surface pCO2 and associated environmental variables, which were utilized to train and validate the retrieval scheme.

Using these data, an XGBoost machine learning model reconstructed monthly pCO2 distributions across the AO for 2003–2022. During model calibration, 60% of the 90,623 matchup pairs (57,092 matchup pairs) were randomly selected to construct the training datasets for the XGBoost model, 30% of the original dataset (24,468 matchup pairs) was designated as the corresponding test dataset, and the remaining 10% (9063 matchup pairs) were reserved for independent validation of the model’s performance. The final XGBoost algorithm consisted of 1820 decision trees with a maximum depth of nine levels. Each tree was trained using 90% of the input features and 80% of the training samples, selected through random subsampling. A learning rate of 0.2 was applied to each sequential tree, and L1 regularization was used to mitigate overfitting. Multiple metrics were used to comprehensively assess the XGBoost model85,89,90, including RMSE, R², mean bias (MB), mean ratio (MR), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), and mean relative error (MRE).

Overall, the XGBoost model training results yielded an average R2 of 0.98 and an RMSE of 5 μatm compared to the observations. The MB was lower than –0.02 μatm, the MR was near 1, the MAPE was less than 1.0%, and the MRE was below –0.04%. The statistical metrics indicate that the XGBoost regression model reliably reproduced the variability of sea surface pCO2 across the AO. Its predictive skill was further assessed with an independent validation dataset (Supplementary Table 1). For the two cruises conducted in the Barents and Chukchi Seas, the XGBoost model successfully reproduced the variation of pCO2 on the shelves (Supplementary Fig. 5), with R2 of 0.95 and 0.91, RMSE of 13.87 μatm and 16.53 μatm, MB of 0.37 μatm and 1.76 μatm, MR of 1.00 and 1.01, MAPE of 2.53% and 3.03%, and MRE of 0.16% and 0.62%, respectively. For the dataset comprising 25 independent cruises, the XGBoost model achieved R2 > 0.95, RMSE < 9 μatm, an MB of –0.03 μatm, an MR near 1, MAPE less than 1.50%, and an MRE of –0.02% (Supplementary Table 1). These results confirm that the satellite-based XGBoost model reliably reconstructs sea surface pCO2 variability.

Calculation air-sea CO2 flux (Step 2)

Using satellite-derived pCO2, 10 m wind speed (U10), xCO2, sea level pressure (Psl), ice, SSS, and SST, we estimated long-term air-sea CO2 fluxes in the AO from 2003 to 2022. The net air-sea CO2 flux (FCO2) was calculated as follows91,92:

where \({K}_{{{\mbox{CO}}}_{2}}\) (m d−1) in Eq. (2) and (3) represents the gas transfer velocity of CO2, estimated from the 10 m wind speed (U10, m s−1) and the Schmidt number (\({S}_{{\mbox{C}}}\)) following Wanninkhof et al.93. Monthly mean U10 values were taken from the NCEP-DOE Reanalysis 2 dataset (https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/gridded/data.ncep.reanalysis2.html). The Schmidt number (\({S}_{{\mbox{C}}}\)) was calculated from SST (°C) using the coefficients reported by Wanninkhof et al.93. \({K}_{{\mbox{S}}}\) in Eq. (2) represents the CO2 solubility coefficient, which depends on SST and SSS94. The term ice denotes the fraction of the air-water interface covered by sea ice (%, between 0 and 1), extracted from the NOAA/NSIDC Climate Data Record of Passive Microwave Sea Ice Concentration product (G02202)95. ΔpCO2 is the difference in partial pressure between oceanic and atmospheric CO2 (equation (4)), where \({{p{\mbox{CO}}}_{2}}_{{\mbox{sea}}}\,\) and \({{p{\mbox{CO}}}_{2}}_{{\mbox{air}}}\) represent sea surface and atmospheric pCO2, respectively. In Eq. (5), Psl and Pw are sea level pressure and water vapor pressure, respectively. Monthly mean Psl values were extracted from a reanalysis dataset (ECMWF-ERA5, https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/) over the study period, and Pw was calculated from Psl and SST96. The \({{p{\mbox{CO}}}_{2}}_{{\mbox{air}}}\) values were computed from monthly averages of the xCO2 (data adopted from the above) and atmospheric pressure following Dickson et al.97. Similarly, all parameters, including \({{p{\mbox{CO}}}_{2}}_{{\mbox{air}}}\), U10, and sea ice, were mapped onto a 4 km × 4 km grid and averaged to monthly means to ensure consistency with the gridded sea surface pCO2 as described above.

Calculation of net community production (Step 3-6)

Satellite observations have been widely used to derive NCP via various empirical algorithms, enabling further investigations of biological pump variability in both regional and global oceans16,23,25,64,65,75,76. However, the inherent limitations of these empirical approaches constrain their application in the rapidly changing AO, as they either assume a constant e-ratio or rely on statistical regressions between NCP and NPP. To overcome these limitations, we developed a semi-analytical retrieval algorithm to characterize the biological pump in the changing AO and applied it to generate a satellite-based summer NCP dataset spanning nearly two decades (Supplementary Fig. 1).

NCP was estimated based on observed temporal variations of nutrients or DIC in the upper mixed layer28,98. In this study, we employed DIC drawdown in the upper mixed layer to estimate NCP. Monthly DIC values were calculated from satellite-derived pCO₂ (pCO2sat), total alkalinity (TAsat) and other parameters (Psl, SSTsat, SSSsat) using the CO2SYS program version 3.227,99,100 (Step 4). The pCO₂sat values were retrieved from satellite observations utilizing the XGBoost model described above, while SSTsat represents the MODIS/Aqua L3 SST product. The SSSsat, provided by the CMEMS, is the reanalysis product simulated from satellite observations and field measurements. The TAsat in surface seawater was estimated from SSSsat using an empirical statistical relationship calibrated with discrete field measurements of TA and salinity from the upper mixed layer (depth <30 m), obtained from the GLODAPv2.2022 dataset80,91 (Step 3, Supplementary Fig. 1c). Only samples collected in the AO during summer (June–September) from 2003 to 2022 were utilized to establish an empirical algorithm between SSS and TA. This linear relationship (Eq. (6), R2 = 0.91, N = 1664, P < 0.001) was employed to derive the m\({\mbox{TA}}=\left(44.27{\pm}0.34\right)\times {\mbox{SSS}}+\left(767.39{\pm}10.17\right)\) onthly TAsat dataset for the AO over the long-term series from the SSS product.

The accuracy of satellite-derived DICsat was evaluated using field-measured DIC from the GLODAPv2.202280 dataset. Although the time scales of the two datasets (monthly DICsat dataset vs daily DICin situ dataset) are not aligned, the DICsat generated by the CO2SYS program effectively captured the variation of field-measured DICin situ, exhibiting a robust linear relationship (Slope = 0.81, R2 = 0.52, P < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. 6a). Additionally, a reference dataset (DICcal) was produced using field-measured pCO2, SSS, SST, Psl, and TA processed in the CO2SYS program to validate the satellite-based DICsat. The comparison yielded strong agreement, with a Slope of 0.88 and an R2 of 0.78 (Supplementary Fig. 6b). These results confirm that the satellite observation-based DICsat successfully captured the DIC variations and could be reliably used to estimate NCP in the AO.

A one-dimensional biogeochemical mass balance model was applied to the mixed layer to quantify the DIC budget and disentangle the contributions of physical mixing, air-sea CO2 fluxes, and biological activities (e.g., photosynthesis and respiration) (Step 5). Therefore, based on the conservation of mass principle, the temporal change in DIC mass balance (\(\Delta {\mbox{DIC}}\)) can be expressed as Eq. (7)92,99,101:

where \(\Delta {\mbox{DIC}}\) represents the total change in DIC inventory within the surface mixed layer, calculated as DIC concentration at time step t + 1 (one month in this study) minus that at time step t (Eq. (8)). \(\Delta {{\mbox{DIC}}}_{{\mbox{a}}-{\mbox{s}}}\) denotes the contribution from air-sea CO2 flux, \(\Delta {{\mbox{DIC}}}_{{\mbox{bio}}}\) represents biologically driven DIC changes, and \(\Delta {{\mbox{DIC}}}_{{\mbox{mix}}}\) accounts for physical mixing processes, including horizontal advection, vertical entrainment/detrainment, and turbulent diffusion102.

To address horizontal advection, we applied a non-zero endmember salinity normalization approach (Eq. (9))27,103,104, where salinity was used as a conservative tracer to correct the dilution effect of sea ice meltwater and river runoff on DIC:

where the endmember salinity, DIC, and TA values for meltwater/river-runoff were set at 5 psu, 400 μmol kg−1, and 450 μmol kg−1, respectively105, corresponding to DICS=0 = 60 μmol kg−1 and TAS=0 = 104 μmol kg−1. Using the previously described monthly SSS product, we calculated the grid-cell mean salinity over 2003–2022 as a reference value (\({{\mbox{S}}}_{0}\))27,106, which helps to smooth short-term advective variability.

In the AO, vertical turbulent exchange across the base of the mixed layer is typically weak during summer, driven by strong stratification. Reported vertical diffusion coefficients107 (\({K}_{{\mbox{z}}}\)) range from 10−8 to 10−6 m2 s−1, exerting a much smaller influence on DIC horizontal freshwater inputs (i.e., sea ice meltwater and river runoff). Consequently, their contribution to DIC variability is negligible. Regarding the entrainment/detrainment process, its accurate quantification relies heavily on spatiotemporally continuous observations of DIC below the mixed layer (\({{\mbox{DIC}}}_{{\mbox{below}}}\))108. However, due to limitations in the penetration depth and inversion accuracy of remote sensing techniques, the vertical fine structure of deep DIC—such as the dynamic variations in \({{\mbox{DIC}}}_{{\mbox{below}}}\) with depth and time—is challenging to precisely retrieve via remote sensing. To assess the potential impact of the entrainment/detrainment process, we used in situ DIC profile datasets (e.g., GLODAPv2.2022) to calculate the vertical DIC gradient (\(\frac{{{{\rm{dDIC}}}}}{{{{\rm{dz}}}}}\)) and derive \({{\mbox{DIC}}}_{{\mbox{below}}}\) (i.e., DIC below the MLD)108. Results demonstrate that the entrainment/detrainment process contributes approximately 8.57% to the \({\mbox{sDIC}}\) estimate. Additionally, MLD remains relatively stable during summer in the AO, such that vertical entrainment events are episodic. Therefore, the impact of vertical mixing on DIC was relatively minor. The temporal changes in \({\mbox{sDIC}}\) (\(\Delta {\mbox{sDIC}}\)) primarily reflect biological activity and air-sea CO2 flux (Eq. (10)):

Surface seawater density, \(\rho\) (kg m−3) was derived from SST and SSS data using the equation of state109 and used to convert DIC from units of μmol kg−1 to mmol m−3. Changes in DIC attributable to air-sea CO2 exchange were calculated according to Eq. (11):

where FCO2 represents the net air-sea CO2 flux (mmol C m−2 d−1), ∆t is a time step (one month in this study), and MLD data were obtained from CMEMS. Biologically driven DIC change (\(\Delta {{\mbox{DIC}}}_{{\mbox{bio}}}\)) was calculated by correcting the air-sea CO2 flux effect (\(\Delta {{\mbox{DIC}}}_{{\mbox{a}}-{\mbox{s}}}\)) based on conservative mixing (Eq. (12)). Finally, NCP (mmol C m−2 d−1, i.e., \(\Delta {{\mbox{DIC}}}_{{\mbox{bio}}}\)) was estimated as Eq. (13)92,101 (Step 6).

Using DICsat to compute \(\Delta {\mbox{DIC}}\) in Eq. (7), NCPsat can subsequently be estimated from satellite observation-based products through Eq. (8−13). The reliability of satellite-derived NCP estimates (NCPsat) was assessed by comparison with ship-based NCP derived from O2/Ar measurements collected during five cruises across the western AO, central and eastern North American Arctic, and Subarctic (Supplementary Fig. 7). In high-latitude regions, ocean color data acquisition is challenged by sea ice, persistent cloud cover110, and high solar zenith angles, resulting in substantial data loss after quality control. To ensure statistically robust validation, monthly-averaged NCPsat values were collocated with instantaneous ship-based \({{\rm{NCP}}}_{{{\rm{O}}}_{{2}}/{{\rm{Ar}}}}\) observations in space and time. Supplementary Fig. 7 shows that NCPsat and \({{\rm{NCP}}}_{{{\rm{O}}}_{{2}}/{{\rm{Ar}}}}\) exhibit strong consistency in overall spatial patterns and temporal variations. Statistical comparison across \({{\rm{NCP}}}_{{{\rm{O}}}_{{2}}/{{\rm{Ar}}}}\) measurements from five cruises (−22 to 190 mmol C m−2 d−1) indicates that the mean deviation of NCPsat ranges from −7.83 to 2.29 mmol C m−2 d−1, which falls within the expected accuracy range for NCP estimates. Although this agreement holds for most observations, several instantaneous, localized productivity peaks—especially in coastal waters—captured by shipboard measurements are underestimated in the monthly averaged NCPsat data. This underestimation mainly results from mismatches in spatial and temporal resolution. Satellite-derived values represent averages over 4 km × 4 km pixels and monthly timescales, while shipboard measurements are instantaneous, small-scale “snapshots”. Residual analysis (right panel of Supplementary Fig. 7) indicates that large residuals, though occasionally present, are rare and contribute negligibly to the total variance. The dominant pattern shows a tight clustering of residuals around zero, indicating strong overall consistency between the datasets. In summary, despite limitations in resolving short-lived, localized productivity events, NCPsat reliably captures the dominant spatiotemporal variability of NCP in the AO and is suitable for assessing large-scale, long-term trends.

Calculation of net primary productivity

We calculated NPP using five distinct models to evaluate biological pump efficiency and its ranges (Supplementary Fig. 8). The Vertically Generalized Production Model (VGPM), which is based on chlorophyll, available light, and photosynthetic efficiency, links chlorophyll to temperature-dependent growth rates via a polynomial function of SST. Although it lacks explicit spectral, temporal, or vertical resolution31, VGPM remains widely applied, with studies highlighting the critical need for accurate estimation of photosynthetic efficiency111. Accordingly, Morel et al.32 modified the photosynthetic efficiency in VGPM to an exponential function of SST based on the Eppley curve, yielding a reasonable estimate of the photosynthetic efficiency (e.g., Eppley-VGPM). Pabi et al.35 developed a regionally calibrated NPP algorithm, the Arctic Ocean Productivity Model (AOPM), which integrates satellite remote sensing data of Chla, SST, PAR, and sea ice cover to account for the changing AO. In contrast, the Carbon-based Productivity Model (CbPM) estimates phytoplankton biomass using remote sensing-derived particulate scattering coefficients, allowing carbon concentration to serve as the primary metric instead of chlorophyll33. The CAFE model34 explicitly considers the absorption by Colored, Dissolved, and Detrital material (CDM) to reduce overestimations of NPP in coastal waters. Given the reliance on the variable Chla in multiple models (VGPM, Eppley-VGPM, and AOPM), we developed a locally optimized satellite-based Chla remote sensing retrieval algorithm (Supplementary Fig. 4) tailored for the AO to improve the accuracy of NPP estimation.

To ensure robust trend analysis, we examined long-term temporal trends across all five NPP datasets (Supplementary Fig. 11a). VGPM, Eppley-VGPM, and AOPM showed broadly similar trajectories over the two decades. In contrast, CbPM continued to rise significantly after 2012, while the CAFE trend weakened, reflecting inherent algorithmic sensitivities to environmental drivers or input data sources. Importantly, spatial distribution patterns were highly consistent across all products (Supplementary Fig. 8). The e-ratio (NCP/NPP) remained remarkably stable both spatially and temporally (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 11a), demonstrating robustness against NPP model choice and supporting its use in assessing export efficiency. To further minimize inter-model discrepancies in trend analysis, we used the mean across the five NPP products (Supplementary Fig. 9). We focused on NPP and NCP rates (mmol C m−2 d−1) rather than total integrated carbon (Tg C) to disentangle ecological dynamics from the confounding influence of expanding ice-free areas. Previous studies have indicated that total Arctic NPP (Tg C) increases primarily reflect ice-free area expansion rather than changes in NPP rate44. Our multi-product trend analysis confirms the absence of significant trends in NPP rate during the first decade (Supplementary Fig. 11a), consistent with stable Chla biomass proxies44.

Uncertainty analysis

Uncertainties in pCO2 and FCO2 products were quantified following the methodological approach of Landschützer et al.112,113, as implemented in later studies114,115. For each grid cell, the total uncertainty in estimated pCO2 was composed of three sources: the direct pCO2 measurement uncertainty (Uobs) from the databases, gridding uncertainty (Ugrid), and mapping uncertainty (Umap). In accordance with Sharp et al.115, Uobs was assigned based on SOCAT fCO2 accuracy flags (A-D), with flags “A” and “B” corresponding to ±2 µatm, and flags “C” and “D” reflecting an accuracy of 5 µatm79. Only data from the SOCAT database corresponding to Flags “A” and “B” were employed for constructing the retrieval model. The uncertainties of pCO2 measurements from other databases remain unknown, and their sample sizes (2.52%) are limited. To ensure a conservative approach, Uobs was set at a maximum of 5 μatm. The uncertainty derived from comparing pCO2 products generated by the XGBoost model with observations from the pCO2 databases represents Umap, with a predictive error of 8.63 μatm in the AO. Ugrid, representing the uncertainty introduced when gridding pCO2 observations from the databases onto 4-km monthly mesh maps, was calculated at 1.82 µatm, based on the estimates from the method of Roobaert et al.116 for the AO. Assuming independence among these sources, the overall uncertainty of the gridded pCO2 product (\({{\rm{U}}}_{{p{{\rm{CO}}}}_{2}}\)) was determined using Monte Carlo error propagation113,114,116 (Supplementary Table 2).

In estimating FCO2, uncertainties arise from four independent components in equations (2) to (5) used to calculate FCO2: (1) the XGBoost-derived sea surface pCO2 field constraining the air–sea gradient, (2) the gas exchange transfer velocity, (3) the solubility coefficient of carbon dioxide, and (4) the choice of the sea-ice product. Assuming the independence of these four sources, the overall FCO2 uncertainty (\({\theta }_{{{\mbox{FCO}}}_{2}}\)) was derived through root-sum-of-squares propagation (Eq. (14)), following the strategy utilized by Landschützer et al.112,113:

the uncertainty of the transfer velocity, \({\theta }_{{{\mbox{kCO}}}_{2}}\), primarily associated with the wind product, was estimated to be approximately 20%93. The contribution of the gas solubility coefficient term (\({\theta }_{{{\mbox{k}}}_{{\mbox{s}}}}\)) to our uncertainty assessment is minimal (0.2%), as suggested by Weiss et al.94. Assessments by Peng et al.117 indicate that the uncertainty associated with sea ice products is roughly 5%. To ensure a conservative estimate, we doubled this value and adopted 10% as the sea ice uncertainty. The NOAA MBL reference product provides an estimate of xCO2 uncertainty, derived by averaging uncertainties across each sine latitude step in the AO. As reported by Lan et al.84, the average uncertainty for xCO2 is 0.32 ppm. Additional uncertainties for other variables are detailed in Supplementary Table 2. Subsequently, we employed Eqs. (4) and (5) to calculate the uncertainties for \({{p{\mbox{CO}}}_{2}}_{{\mbox{air}}}\) and \({\Delta p{\mbox{CO}}}_{2}\).

Because NCP uncertainty is derived through the propagation of errors in DIC, we first evaluated the sources of DIC uncertainty. Given the uncertainties of relevant parameters (i.e., salinity-based TA, pCO2; Supplementary Table 2), the propagated uncertainties of DIC were estimated using an add-on118 for the CO2SYS program in MATLAB 2021. The propagated uncertainty incorporates combined standard uncertainties from input variables as well as the equilibrium constants100,118. TA uncertainty was assessed prior to the CO2SYS calculations and subsequent error propagation. The uncertainty of DIC was estimated at ~37.52 μmol kg−1, based on uncertainties in the TA calculation (41.44 μmol kg−1; see Eq. (6)), pCO2 (0.31 μatm), and outputs from CO2SYS. We also split the AO into four subregions (Inflow shelf, Interior shelf, Outflow shelf, and Basin), and developed empirical algorithms for each region using salinity as a proxy to estimate the surface TA concentrations, yielding an average uncertainty of 38.38 μmol kg−1, with a total uncertainty in the calculated DIC of 34.95 μmol kg−1. This result is slightly lower than the DIC uncertainty calculated from the salinity-TA relationship (Eq. (6)).

We quantified NCP uncertainties (equations (7) to (13)) by propagating parameter error through Monte Carlo simulations. For each error term, 100,000 simulations were run using Gaussian distributions, and the 95% confidence interval was used to represent uncertainty bounds for each data point in the time series119. Combined uncertainty from individual sources of error as well as NCP using the Monte Carlo simulation approach is shown in Supplementary Table 2. Satellite and reanalysis data contributed the most to the total uncertainty. The gas transfer coefficient uncertainty \({\theta }_{{{\mbox{kCO}}}_{2}}\) (20%), represents the largest contributor to FCO2 uncertainty, which propagates further into NCP calculation. The resulting uncertainty for simulated NCP based on the Monte Carlo approach is 46.85%. All reported uncertainties apply to the pan-Arctic scale and may be larger at the subregional scale114. The uncertainty associated with in situ NCP measurements was negligible (0.2%)120 relative to other error terms, and therefore excluded from the final uncertainty analysis. Although the uncertainty in NCP approaches 50%, these estimates still discern the direction of NCP measurements observed during most cruises. Moreover, this uncertainty does not significantly affect the spatial distribution or long-term trend of NCP, but only its magnitude.

NCP simulation based on Community Earth System Model version 2 (CESM2)

We conducted the historical scenario experiment (1850−2014) and the high-emissions future scenario (SSP5-8.5)121 experiment (2015−2100) using CESM2 configured with MARBL-SPECTRA to assess longer-term changes in NCP and its relationship with SIC across the pan-Arctic region. CESM2 integrates multiple components, including the CAM6 atmosphere, CLM5 land, MOSART river runoff, WW3 wave, CISM2 land-ice, CICE5 sea-ice, POP2 ocean, and MARBL ocean biogeochemistry models. The Marine Biogeochemistry Library (MARBL)73 is the core oceanic biogeochemical component of the CESM2122. Its modular design allows for flexible configuration of plankton functional types. In this study, we implemented the Size-based Plankton Ecological TRAits (SPECTRA) community model within MARBL72. This configuration, referred to as MARBL-SPECTRA, represents an advancement over the default MARBL setup, including nine phytoplankton and six zooplankton functional types with equivalent spherical diameter (ESD) ranging from 0.47–300 μm and 0.02–20 mm, respectively. Compared to the default configuration (three types of phytoplankton and one type of zooplankton), MARBL-SPECTRA significantly expands the diversity of functional types and size classes of plankton. This enables a more complex representation of the marine food web and improves our understanding of key processes such as plankton community dynamics, which were previously difficult to resolve.

MARBL-SPECTRA supports multiple ecosystem configurations of varying complexity, each incorporating different quantities and properties of functional groups, thereby demonstrating the flexibility of MARBL’s ecosystem configuration. We first used spectra-config, available at https://github.com/marbl-ecosys/spectra-config, to generate configuration files and initial conditions for MARBL-SPECTRA. MARBL-SPECTRA was then integrated into CESM2, available at https://github.com/ESCOMP/CESM, to simulate long-term biogeochemical variables from 1850 to 2100. The experiments were conducted with BHIST and BSSP585 configurations at f19_g16 resolution, which uses a finite-volume 1.9° × 2.5° mesh for the atmospheric and land components and a gx1v6 polar-shifted grid (~1°) for the oceanic and sea-ice modules. All remaining CESM2 parameters were kept at their default settings. From the CESM2 outputs, the rate of change in DIC due to biological activity was used to assess NCP variability in the AO. Sea ice fraction was also extracted to examine the variation of SIC. After modifying the phytoplankton community module in the CESM2 model, we extracted biomass data for nine phytoplankton species (Supplementary Table 4), grouped them into small and large categories based on ESD72, and calculated their relative proportions in the AO. The small group (ESD < 20 μm) included the two smallest mixed phytoplankton (mp1, mp2), picoplankton (pp), and diazotroph (diaz), whereas the large group (ESD ≥ 20 μm) comprised three diatom size classes (diat1, diat2, diat3) and the two largest mixed phytoplankton types (mp3, mp4). The extracted data, including NCP, sea ice fraction, and phytoplankton community structure, were subsequently used to analyse the relationships among these variables in the AO.

Statistical analysis

We applied Sen’s slope (derived from the Mann-Kendall test) of the long-term summer means of NCP, NPP, and the e-ratio to estimate their rates of change, with the corresponding P values used to assess the significance of these trends. Kendall’s tau-b correlation coefficient was used to assess correlations between time and NCP, NPP, e-ratio, SIC, and OWD, with trends deemed significant at P < 0.05. All Mann-Kendall trend analyses were conducted in MATLAB 2021. Additionally, Pearson’s correlation analyses (Pearson’s r) were performed to evaluate relationships between summer mean NCP and e-ratio and variables including SIC, OWD, Chla, and MLD. Statistical significance of these correlation coefficients was determined using P values (e.g., P < 0.05). Additionally, to investigate the causal relationship between key drivers and two metrics of the Arctic biological carbon pump—NCP and carbon export efficiency (e-ratio), we categorized potential drivers into physical variables (SIC, Wind, MLD, OWD, PAR, and SST) and biological variables (Nutrient, Chla, and NPP). All variables were derived from the dataset described in the Methods section. Nutrient data were obtained through modal decomposition of nitrate, phosphate, and silicate concentrations, with the original data sourced from the CMEMS product. Informed by prior knowledge, we employed the “PiecewiseSEM” R package to construct a piecewise structural equation model67, quantifying the pathways through which these drivers affect NCP and the e-ratio. The final model was selected based on the goodness-of-fit statistic (Fisher’s C) and the corresponding P value.

Data availability

The SOCAT v.2022 dataset can be accessed at https://socat.info/index.php/version-2022, and the GLODAP v2.2022 dataset is available at https://glodap.info/index.php/merged-and-adjusted-data-product-v2-2022. The Chinese National Arctic and Antarctic Data Center (NAADC) data are available at https://datacenter.chinare.org.cn/, and the JAMSTEC dataset is available at http://www.godac.jamstec.go.jp/darwin/e, and the United States Geological Survey (USGS) database is available at https://pubs.er.usgs.gov. The NASA Ocean Biology Processing Group (OBPG) MODIS products (Rrs, Chla, SST, PAR) are available at https://oceandata.sci.gsfc.nasa.gov/. The MLD, SSS, and Nutrients (NO3, PO4, and Si) data were obtained from the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS) at http://marine.copernicus.eu/. xCO2 data were sourced from the NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory (ESRL) Greenhouse Gas Marine Boundary Layer Reference at http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/mbl/. SIC data were downloaded from the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) at https://nsidc.org/data/g02202/. Wind speed data from the NCEP-DOE Reanalysis 2 product at https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/gridded/data.ncep.reanalysis2.html, and monthly mean sea level pressure (Psl) reanalysis data were obtained from the ECMWF-ERA5 at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/. Model outputs from CESM2 used in this study, as well as the satellite-based dataset of NCP in the AO at 4-km resolution, are available from Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14020827. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The CESM2 model is available from GitHub at http://github.com/ESCOMP/CESM. The code for generating the runtime-configurable name list parameters for MARBL-SPECTRA is available at https://github.com/marbl-ecosys/spectra-config. The code in this study is archived on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14020827.

References

Sumata, H. et al. Regime shift in Arctic Ocean sea ice thickness. Nature 615, 443–449 (2023).

Stroeve, J. & Notz, D. Changing state of Arctic sea ice across all seasons. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 103001 (2018).

Boyd, P. W. et al. Multi-faceted particle pumps drive carbon sequestration in the ocean. Nature 568, 327–335 (2019).

Yasunaka, S. et al. Arctic Ocean CO2 uptake: An improved multiyear estimate of the air-sea CO2 flux incorporating chlorophyll aconcentrations. Biogeosciences 15, 1643–1661 (2018).

Takahashi, T. et al. Climatological mean and decadal change in surface ocean pCO2, and net sea-air CO2 flux over the global oceans. Deep-Sea Res. Part II-Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 56, 554–577 (2009).

Yasunaka, S. et al. An assessment of CO2 uptake in the Arctic Ocean from 1985 to 2018. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 37, e2023GB007806 (2023).

MacGilchrist, G. A. et al. The Arctic Ocean carbon sink. Deep-Sea Res. Part I-Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 86, 39–55 (2014).

Fadeev, E. et al. Sea ice presence is linked to higher carbon export and vertical microbial connectivity in the Eurasian Arctic Ocean. Commun. Biol. 4, 1255 (2021).

von Appen, W.-J. et al. Sea-ice derived meltwater stratification slows the biological carbon pump: Results from continuous observations. Nat. Commun. 12, 7309 (2021).

Kwon, S. et al. Summer net community production in the northern Chukchi Sea: Comparison between 2017 and 2020. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 1050791 (2022).

Watanabe, E. et al. Enhanced role of eddies in the Arctic marine biological pump. Nat. Commun. 5, 3950 (2014).

Harada, N. Review: Potential catastrophic reduction of sea ice in the western Arctic Ocean: Its impact on biogeochemical cycles and marine ecosystems. Glob. Planet. Change 136, 1–17 (2016).

Nishino, S. et al. Enhancement/reduction of biological pump depends on ocean circulation in the sea-ice reduction regions of the Arctic Ocean. J. Oceanogr. 67, 305–314 (2011).

Song, H. et al. Strong and regionally distinct links between ice-retreat timing and phytoplankton production in the Arctic Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 66, 2498–2508 (2021).

Arteaga, L. et al. Assessment of export efficiency equations in the Southern Ocean applied to satellite-based net primary production. J. Geophys. Res. -Oceans 123, 2945–2964 (2018).

Laws, E. A., D’Sa, E. & Naik, P. Simple equations to estimate ratios of new or export production to total production from satellite-derived estimates of sea surface temperature and primary production. Limnol. Oceanogr. Meth. 9, 593–601 (2011).

Oziel, L. et al. Climate change and terrigenous inputs decrease the efficiency of the future Arctic Ocean’s biological carbon pump. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 171–179 (2025).

Burd, A. B. Modeling the vertical flux of organic carbon in the global ocean. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 16, 135–161 (2024).

Wang, W.-L. et al. Biological carbon pump estimate based on multidecadal hydrographic data. Nature 624, 579–585 (2023).

Henson, S. A. et al. Uncertain response of ocean biological carbon export in a changing world. Nat. Geosci. 15, 248–254 (2022).

Siegel, D. A., DeVries, T., Cetinic, I. & Bisson, K. M. Quantifying the Ocean’s Biological Pump and Its Carbon Cycle Impacts on Global Scales. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 15, 329–356 (2023).

Stukel, M. R. et al. Carbon sequestration by multiple biological pump pathways in a coastal upwelling biome. Nat. Commun. 14, 2024 (2023).

Laws, E. A. et al. Temperature effects on export production in the open ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 14, 1231–1246 (2000).

Haskell, W. Z., Fassbender, A. J., Long, J. S. & Plant, J. N. Annual net community production of particulate and dissolved organic carbon from a decade of biogeochemical profiling float observations in the Northeast Pacific. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 34, e2020GB006599 (2020).

Li, Z. & Cassar, N. Satellite estimates of net community production based on O2/Ar observations and comparison to other estimates. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 30, 735–752 (2016).

Yang, B. Seasonal relationship between net primary and net community production in the Subtropical Gyres: Insights from satellite and argo profiling float measurements. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093837 (2021).

Ouyang, Z. et al. Sea-ice loss amplifies summertime decadal CO2 increase in the western Arctic Ocean. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 678–684 (2020).

Burgers, T. M., Tremblay, J.-É., Else, B. G. T. & Papakyriakou, T. N. Estimates of net community production from multiple approaches surrounding the spring ice-edge bloom in Baffin Bay. Elem. -Sci. Anthr. 8, 013 (2020).

Izett, R. W. et al. Impact of vertical mixing on summertime net community production in Canadian Arctic and Subarctic Waters: Insights from in situ measurements and numerical simulations. J. Geophys. Res. -Oceans 127, e2021JC018215 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Research progress in calculating net community production of marine ecosystem by remote sensing. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1191013 (2023).

Behrenfeld, M. J. & Falkowski, P. G. Photosynthetic rates derived from satellite-based chlorophyll concentration. Limnol. Oceanogr. 42, 1–20 (1997).

Morel, A. Light and marine photosynthesis: A spectral model with geochemical and climatological implications. Prog. Oceanogr. 26, 263–306 (1991).

Westberry, T., Behrenfeld, M. J., Siegel, D. A. & Boss, E. Carbon-based primary productivity modeling with vertically resolved photoacclimation. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 22, GB2024 (2008).

Silsbe, G. M. et al. The CAFE model: A net production model for global ocean phytoplankton. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 30, 1756–1777 (2016).

Pabi, S., van Dijken, G. L. & Arrigo, K. R. Primary production in the Arctic Ocean, 1998–2006. J. Geophys. Res. -Oceans 113, C08005 (2008).

Wang, Q. et al. Intensification of the Atlantic water supply to the Arctic Ocean through the Fram Strait induced by Arctic sea ice decline. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086682 (2020).

Woodgate, R. A. & Peralta-Ferriz, C. Warming and freshening of the Pacific inflow to the Arctic from 1990-2019 implying dramatic shoaling in Pacific winter water ventilation of the Arctic water column. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL092528 (2021).

Holmes, R. M. et al. Seasonal and annual fluxes of nutrients and organic matter from large rivers to the Arctic Ocean and surrounding seas. Estuaries Coasts 35, 369–382 (2012).

Alling, V. et al. Nonconservative behavior of dissolved organic carbon across the Laptev and East Siberian seas. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 24, GB4033 (2010).

Zhang, Y. et al. Sea-ice loss accelerates carbon cycling and enhances seasonal extremes of acidification in the Arctic Chukchi Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 9, 433–441 (2024).

Castagno, A. P. et al. Increased sea ice melt as a driver of enhanced Arctic phytoplankton blooming. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 5087–5098 (2023).

Oldenburg, E. et al. Sea-ice melt determines seasonal phytoplankton dynamics and delimits the habitat of temperate Atlantic taxa as the Arctic Ocean atlantifies. ISME Commun. 4, ycae027 (2024).

Lannuzel, D. et al. The future of Arctic sea-ice biogeochemistry and ice-associated ecosystems. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 983–992 (2020).

Ardyna, M. & Arrigo, K. R. Phytoplankton dynamics in a changing Arctic Ocean. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 892–903 (2020).

Lewis, K. M., van Dijken, G. L. & Arrigo, K. R. Changes in phytoplankton concentration now drive increased Arctic Ocean primary production. Science 369, 198–202 (2020).

Qi, D. et al. Climate change drives rapid decadal acidification in the Arctic Ocean from 1994 to 2020. Science 377, 1544–1550 (2022).

Parker, C. L., Mooney, P. A., Webster, M. A. & Boisvert, L. N. The influence of recent and future climate change on spring Arctic cyclones. Nat. Commun. 13, 6514 (2022).

Xu, A., Jin, M., Wu, Y. & Qi, D. Response of nutrients and primary production to high wind and upwelling-favorable wind in the Arctic Ocean: A modeling perspective. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1065006 (2023).

Dosser, H. V. et al. Changes in internal wave-driven mixing across the Arctic Ocean: Finescale estimates from an 18-year pan-Arctic record. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091747 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Eddy activity in the Arctic Ocean projected to surge in a warming world. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 156–162 (2024).

Allende, S., Fichefet, T., Goosse, H. & Treguier, A. M. On the ability of OMIP models to simulate the ocean mixed layer depth and its seasonal cycle in the Arctic Ocean. Ocean Model 184, 102226 (2023).

Brenner, S. et al. Wind-driven motions of the ocean surface mixed layer in the Western Arctic. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 53, 1787–1804 (2023).

Hordoir, R. et al. Changes in Arctic stratification and mixed layer depth cycle: a modeling analysis. J. Geophys. Res. -Oceans 127, e2021JC017270 (2022).

Mills, M. M. et al. Nitrogen Limitation of the Summer Phytoplankton and Heterotrophic Prokaryote Communities in the Chukchi Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 5, 362 (2018).

Tremblay, J. É. et al. Vertical stability and the annual dynamics of nutrients and chlorophyll fluorescence in the coastal, southeast Beaufort Sea. J. Geophys. Res. -Oceans 113, C07S90 (2008).

Kellogg, D. R. & Levin, P. A. Nutrient availability as an arbiter of cell size. Trends Cell Biol. 32, 908–919 (2022).

Hill, V., Light, B., Steele, M. & Sybrandy, A. L. Contrasting sea-ice algae blooms in a changing Arctic documented by autonomous drifting buoys. J. Geophys. Res. -Oceans 127, e2021JC017848 (2022).

Blais, M. et al. Contrasting interannual changes in phytoplankton productivity and community structure in the coastal Canadian Arctic Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 62, 2480–2497 (2017).

Toullec, J. et al. Processes controlling aggregate formation and distribution during the Arctic phytoplankton spring bloom in Baffin Bay. Elem. -Sci. Anthr. 9, 1 (2021).

Nadaï, G., Nöthig, E.-M., Fortier, L. & Lalande, C. Early snowmelt and sea ice breakup enhance algal export in the Beaufort Sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 190, 102479 (2021).

Lee, Y. et al. Influence of sea ice concentration on phytoplankton community structure in the Chukchi and East Siberian Seas, Pacific Arctic Ocean. Deep-Sea Res. Part I-Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 147, 54–64 (2019).

Miettinen, T. P. et al. Cell size, density, and nutrient dependency of unicellular algal gravitational sinking velocities. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn8356 (2024).

Guidi, L. et al. A new look at ocean carbon remineralization for estimating deepwater sequestration. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 29, 1044–1059 (2015).

Dunne, J. P., Armstrong, R. A., Gnanadesikan, A. & Sarmiento, J. L. Empirical and mechanistic models for the particle export ratio. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 19, GB4026 (2005).

Dunne, J. P., Sarmiento, J. L. & Gnanadesikan, A. A synthesis of global particle export from the surface ocean and cycling through the ocean interior and on the seafloor. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 21, GB4006 (2007).

Polyakov, I. V. et al. Atlantification advances into the Amerasian Basin of the Arctic Ocean. Sci. Adv. 11, eadq7580 (2025).

Lefcheck, J. S. & Freckleton, R. piecewiseSEM: Piecewise structural equation modelling in R for ecology, evolution, and systematics. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 573–579 (2015).

DeRepentigny, P., Jahn, A., Holland, M. M. & Smith, A. Arctic sea ice in two configurations of the CESM2 during the 20th and 21st centuries. J. Geophys. Res. -Oceans 125, e2020JC016133 (2020).

Webster, M. A., DuVivier, A. K., Holland, M. M. & Bailey, D. A. Snow on Arctic sea ice in a warming climate as simulated in CESM. J. Geophys. Res. -Oceans 126, e2020JC016308 (2021).

McIlhattan, E. A., Kay, J. E. & L’Ecuyer, T. S. Arctic clouds and precipitation in the Community Earth System Model version 2. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 125, e2020JD032521 (2020).

Orr, J. C., Kwiatkowski, L. & Portner, H. O. Arctic Ocean annual high in pCO2 could shift from winter to summer. Nature 610, 94–100 (2022).

Negrete-García, G. et al. Plankton energy flows using a global size-structured and trait-based model. Prog. Oceanogr. 209, 102898 (2022).

Long, M. C. et al. Simulations with the Marine Biogeochemistry Library (MARBL). J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 13, e2021MS002647 (2021).

Cuevas, L. A. et al. Interplay between freshwater discharge and oceanic waters modulates phytoplankton size-structure in fjords and channel systems of the Chilean Patagonia. Prog. Oceanogr. 173, 103–113 (2019).

Britten, G. L., Wakamatsu, L. & Primeau, F. W. The temperature-ballast hypothesis explains carbon export efficiency observations in the Southern Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 1831–1838 (2017).

Li, Z., Lozier, M. S. & Cassar, N. Linking southern ocean mixed-layer dynamics to net community production on various timescales. J. Geophys. Res. -Oceans 126, e2021JC017537 (2021).

Meredith, M. et al. in The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (eds H.-O. Portner et al.) Ch. Chapter 3, 203-320 (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Yamamoto-Kawai, M., Mifune, T., Kikuchi, T. & Nishino, S. Seasonal variation of CaCO3 saturation state in bottom water of a biological hotspot in the Chukchi Sea, Arctic Ocean. Biogeosciences 13, 6155–6169 (2016).

Bakker, D. C. E. et al. A multi-decade record of high-quality fCO2 data in version 3 of the Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 8, 383–413 (2016).

Lauvset, S. K. et al. GLODAPv2.2022: the latest version of the global interior ocean biogeochemical data product. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 5543–5572 (2022).

Lewis, K. M. & Arrigo, K. R. Ocean color algorithms for estimating chlorophylla, CDOM absorption, and particle backscattering in the Arctic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. -Oceans 125, e2019JC015706 (2020).

Beszczynska-Möller, A., Fahrbach, E., Schauer, U. & Hansen, E. Variability in Atlantic water temperature and transport at the entrance to the Arctic Ocean, 1997–2010. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 69, 852–863 (2012).

Drévillon, M. et al. Global Ocean Reanalysis Products GLOBAL_REANALYSIS_PHY_001_030. (2022).

Lan, X., Tans, P. & Thoning, K. NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory: NOAA Greenhouse Gas Marine Boundary Layer Reference–CO2, NOAA GML. (2023).

Chen, S. et al. A machine learning approach to estimate surface ocean pCO2 from satellite measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 228, 203–226 (2019).

Le, C. et al. Estimating summer sea surface pCO2 on a river-dominated continental shelf using a satellite-based semi-mechanistic model. Remote Sens. Environ. 225, 115–126 (2019).

Bailey, S. W. & Werdell, P. J. A multi-sensor approach for the on-orbit validation of ocean color satellite data products. Remote Sens. Environ. 102, 12–23 (2006).

Wrobel-Niedzwiecka, I., Kitowska, M., Makuch, P. & Markuszewski, P. The distribution of pCO2W and air-sea CO2 fluxes using FFNN at the continental shelf areas of the Arctic Ocean. Remote Sens 14, 312 (2022).

Barnes, B. B. & Hu, C. Cross-Sensor continuity of satellite-derived water clarity in the Gulf of Mexico: Insights into temporal aliasing and implications for long-term water clarity assessment. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 53, 1761–1772 (2015).

Tu, Z. et al. Increase in CO2 uptake capacity in the Arctic Chukchi sea during summer revealed by satellite-based estimation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093844 (2021).

Ouyang, Z. et al. The changing CO2 sink in the Western Arctic Ocean from 1994 to 2019. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 36, e2021GB007032 (2022).

Xue, L. et al. Sea surface carbon dioxide at the Georgia time series site (2006–2007): Air-sea flux and controlling processes. Prog. Oceanogr. 140, 14–26 (2016).

Wanninkhof, R. Relationship between wind speed and gas exchange over the ocean revisited. Limnol. Oceanogr. Meth. 12, 351–362 (2014).

Weiss, R. F. Carbon dioxide in water and seawater: The solubility of a non-ideal gas. Mar. Chem. 2, 203–215 (1974).

Meier, W., Fetterer, F., Windnagel, A. & Stewart, S. (ed NSIDC: National Snow and Ice Data Center) (Boulder, Colorado USA., 2024).

Buck, A. L. New equations for computing vapor pressure and enhancement factor. J. Appl. Meteorol. 20, 1527–1532 (1981).

Dickson, A. G., Sabine, C. L. & Christian, J. R. Guide to best practices for ocean CO2 measurements. (North Pacific Marine Science Organization, 2007).

Ouyang, Z. et al. Summertime evolution of net community production and CO2 flux in the western Arctic Ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 35, e2020GB006651 (2021).