Abstract

Low-symmetry thermoelectric material GeSe exhibits inherently low thermal conductivity but suppressed electrical transport properties. Here, we demonstrate that Mn doping in AgBiTe2-alloyed rhombohedral GeSe introduces band engineering and further significantly enhances lattice symmetry. Mn-induced resonant energy levels enhance the density of states effective mass and significantly optimize the Seebeck coefficient. Crucially, elevated lattice symmetry reduces deformation potential and weakens phonon-electron coupling, triggering a 185% surge in carrier mobility despite a ~1.2-fold increase in the effective mass. The synergistically optimized Seebeck coefficient and electrical conductivity enable the high-symmetry (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 sample to achieve a record average power factor of ~17 μW cm−1 K−2 over 300–673 K while retaining low lattice thermal conductivity. Consequently, a maximum ZT of ~1.50 at 673 K and an average ZT of ~0.94 (300–673 K) are achieved, yielding a single-leg thermoelectric conversion efficiency of ~6.1% under a temperature difference of 325 K. This lattice symmetry manipulation through rational doping provides a universal pathway to promote phonon-electron decoupling and enhances thermoelectric performance in low-symmetry thermoelectric materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global energy sustainability challenges have intensified research into thermoelectric technology for waste heat recovery1,2,3,4,5. The efficiency of thermoelectric materials is governed by the dimensionless figure of merit ZT = T(σS2)/κtot, where a high ZT value requires concurrent high electrical conductivity (σ), large Seebeck coefficient (S), and low total thermal conductivity (κtot)6,7. These correlated parameters pose difficulties for the improvement of net ZT8,9,10. Thermoelectric materials with high structural symmetry, such as bismuth telluride and lead chalcogenides, exhibit both excellent electrical and high thermal transport properties11,12,13. Multiscale defect engineering is implemented to effectively reduce their thermal conductivity and superior thermoelectric performance is achieved14,15. However, as their lattice thermal conductivity is reduced to approach the amorphous limit, a bottleneck for further enhancing thermoelectric performance emerges16,17,18. Thus, achieving a high average ZT across operational temperatures remains a persistent challenge, motivating novel material design paradigms.

Recently, thermoelectric materials with low-symmetry structures have attracted extensive research interest due to their inherent low lattice thermal conductivity19,20,21,22,23,24. The low-symmetry crystal structures exhibit strong anharmonicity arising from their complex atomic arrangements, leading to intrinsically low lattice thermal conductivity but poor electrical transport properties25,26,27,28,29. Enhancing electrical properties necessitates concurrent improvement of the conflicting S and σ. According to Pisarenko relationship, increasing carrier concentration (n) contrarily diminishes the S30,31. Low-symmetry materials with complex electronic band structure allow band engineering to enhance the density of states effective mass (m*) and benefit S32,33,34. Nevertheless, enhanced m* could dramatically degrade carrier mobility (μ) due to the relationship of μ ∝ m*−2.5. Thus, the key challenge is to liberate the suppressed μ by decoupling phonon-electron interrelation without decreasing m*35,36,37. Strategies of elevating structural symmetry offer a pathway to decouple phonon-electron interactions through reducing deformation potential Ξ (μ ∝ Ξ −2)38,39. In N and P-type SnSe, the introduction of Pb or Te alloying engineers the complex electronic band structures and thus optimizes the S32,33,34. Meanwhile, lattice symmetry is enhanced, leading to improved μ and thus contributes to higher thermoelectric performance40,41. Inspiringly, doping with elements capable of both band structure modulation and lattice symmetry enhancement could enable synergistic optimization of the S and σ, ultimately realizing superior thermoelectric performance.

Germanium selenide (GeSe) is a low-symmetry thermoelectric material and has attracted attention for its low lattice thermal conductivity and ultrahigh theoretically predicted ZT to ~2.542. However, the thermoelectric performance of intrinsic GeSe is limited by its low carrier concentration (~1 × 1016 cm−3) and poor carrier mobility, primarily attributed to its wide bandgap (~1.1 eV) and the low structural symmetry of orthorhombic phase43,44. To address these limitations, researchers have employed solid-solution engineering to enhance the thermoelectric performance44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60. For instance, the introduction of Te46,47, CdTe48, and I-V-VI2 ternary chalcogenides49 (including AgSbSe250, AgBiTe251,52,53,54, MnCdTe255, etc.) into the GeSe lattice have been shown to transform the orthorhombic phase into a more symmetric rhombohedral phase, which reduces the bandgap to 0.3–0.6 eV61. This phase transition significantly reduces the formation energy of Ge vacancies, thereby leading to an increased hole n of ~1 × 1021 cm−3. Additionally, the higher crystal symmetry of the rhombohedral phase leads to greater band degeneracy, which demonstrates the effectiveness of band structure modulation in Seebeck coefficient optimization in GeSe-based materials. However, a high-performance thermoelectric material requires a Seebeck coefficient of ~160 μV K-1 62. Most reported GeSe-based materials at optimal n of ~1 × 1020 cm−3 exhibit room-temperature S values well below ~150 μV K-1 59. Furthermore, the rhombohedral phase still exhibits a distorted structure with limited symmetry, resulting in compromised μ and suboptimal ZT. Inspired by the previous work on the low-symmetry SnSe, we deduced that further improving the symmetry of rhombohedral phase through precise doping is crucial for fully exploiting the potential of GeSe. This strategy could manipulate electronic bands and concurrently enhance the μ, resulting in increased electrical transport performance. Meanwhile, the sustained inherently low lattice thermal conductivity could promote electron-phonon decoupling, and an optimized ZT could be achieved.

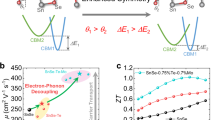

In this work, a two-step strategy was implemented. First, AgBiTe2 alloying was employed to transform the orthorhombic to rhombohedral phase and obtain the optimal (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 matrix. Based on this component, the precise Mn-doping was subsequently performed to occupy the Ge vacancies aiming to further manipulate band structures and elevate the lattice symmetry (Fig. 1a). Compared to (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1, Rietveld refinement confirmed a reduction in lattice distortion following Mn-doping, as demonstrated by convergent bond lengths (l1 and l2) and an enlarged bond angle α. Despite an enhanced m* resulting from resonant levels, Mn-doping increased lattice symmetry versus undoped (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1, yielding a dramatic ~185% surge in room-temperature μ to ~14.4 cm2 V−1 s−1. Consequently, these largely optimized electrical transport properties in the high-symmetry sample (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 resulted in a competitive thermoelectric performance over the whole working temperature. A maximum ZT of 1.50 at 673 K and a high average ZT (ZTave) of ~0.94 across 300–673 K were obtained (Fig. 1b, c), showing an advantage against reported GeSe-based materials. Moreover, a single-leg module efficiency of ~6.1% was achieved for high-symmetry (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 under a temperature difference of 325 K (Fig. 1d). This efficiency rivaled not only GeSe-based devices17,58 but also high-performance P-type single-leg devices fabricated of SnS63, SnTe64, and GeTe-based65 materials. This work demonstrates that precise dopant-induced manipulation of lattice symmetry serves as a universal strategy for optimizing electrical transport properties in low-symmetry thermoelectrics.

a A schematic: Mn doping elevates crystal symmetry and facilitates the carrier transport. b A comparison of ZT values48,49,50,52,53,55,56,57,58 and c Average ZT (ZTave)17,48,49,50,52,53,55,57,58 of high-symmetry (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 in this work compared with other reported GeSe-based samples from 296–315 K to 670–677 K. d Single-leg module efficiency based on (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 compared with other P-type single-legs17,58,63,64,65.

Results

Phase and microstructure characterization

The powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns demonstrated that the alloy of AgBiTe2 transformed the phase from orthorhombic to rhombohedral (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). The PXRD patterns of (GeMnySe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 confirmed a single rhombohedral phase without detectable impurity peaks when the Mn fraction (y) is below 0.005 (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Minor impurity peaks corresponding to Ge2Mn5 were observed in the (GeMn0.007Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 sample. Rietveld refinements were conducted to obtain crystal structure information from the XRD patterns. With the increase of Mn fraction (y ≤ 0.005), the lattice parameters along both the a and c axes increased (Supplementary Fig. 2b), indicating that the Mn atoms may occupy the Ge vacancies. When the Mn fraction reached 0.007, the lattice parameters decreased, which may be ascribed to the existence of the second phase Ge2Mn5 that reduces the Mn fraction in the matrix.

Low-magnification scanning electron microscopy (SEM) energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis confirmed dense microstructures and homogeneous elemental distributions across a large field of view, indicating excellent compositional uniformity at the macroscopic scale (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). The scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) analysis was conducted to obtain high-resolution structural elucidation. Domain structures induced by ferroelectric distortion similar to that in GeTe were also observed in AgBiTe2 alloyed GeSe samples (Fig. 2a, b, and e). A uniform elemental distribution across these domain boundaries was revealed by EDS (Fig. 2f1–f6 and Supplementary Fig. 5a–f). These domain structures could potentially impede phonon transport and result in low thermal conductivity. Atomic-scale annular dark field (ADF) STEM images along the [010] axis of (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 (Fig. 2c, d) revealed a small-angle domain boundary (~4.4°) and distorted square arrangements (yellow quadrilateral) of Ge (purple) and Se (green) atoms (with its fast Fourier transform FFT patterns in Supplementary Fig. 5g). These structural imperfections could be manifested as deficient lattice integrity and inadequate lattice symmetry, both damaging carrier transport. A high-resolution atomic image of (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 along the [2-21] axis showed the absence of apparent dislocations, stacking faults, vacancies, and interstitial atoms (Fig. 2g, with its FFT patterns in Supplementary Fig. 6), indicating the high local lattice integrity of Mn-doped sample at the sub-micron scale. The inset revealed a highly ordered, nearly square atom arrangement (yellow square) along this zone axis, with the observed lattice integrity being beneficial for carrier transport (Fig. 2gi). Collectively, the uniform distribution of Mn from the macroscopic to the atomic scale, the absence of interstitial atoms as observed through atomic-resolution STEM images, and agreement with defect formation energy results (Supplementary Fig. 7), which indicated the lowest energy for Mn substitution at Ge sites (MnGe), jointly confirmed the incorporation of Mn at Ge substitutional lattice positions.

a The low- and (b) medium-magnification ADF-STEM images of (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1, where inherent domain structures exist. c, d Atomic-scale HAADF-STEM image viewed along [010] axis, in which a small-angle domain boundary (~4.4°) and the regular arrangement of Ge (red) and Se (green) atoms can be observed. e The low-magnification ADF-STEM image of (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1. f1-f6 Corresponding EDS elemental maps of e, indicating the even distribution of Ge, Se, Ag, Bi, Te, and Mn. g The atomic-scale ADF-STEM image viewed along [2-21] axis indicated that the lattice within the field of view has no observable atomic defects e.g. dislocations, interstitials, etc. The gi is an enlarged view of (g) indicating that the GeSe in this direction presents a highly symmetrical, regular distribution approximately square.

Enhanced thermal power induced by the resonant level

The structural transition from orthorhombic GeSe to rhombohedral (GeSe)1-x(AgBiTe2)x significantly reduced the S (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 8a). Furthermore, Mn-doped samples exhibited enhanced S across all operating temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 10a), increasing from ~128 μV K−1 in (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 to ~156 μV K−1 in (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 at 300 K. To investigate the origin of this enhancement, Pisarenko relationship was performed according to single parabolic band (SPB) model (Fig. 3b). Although reduced n induced by Mn doping contributes to increased S, the experimental enhancement surpasses theoretical predictions based solely on carrier reduction (data points exceed SPB curves at m* = 3.19 m0). SPB model calculations revealed an increased effective mass of ~3.82 m0 in Mn-doped samples (y = 0.003–0.007), indicating band structure modification as the primary mechanism for the S optimization. First-principles calculations were subsequently conducted to elucidate the impact of Mn doping on the electronic band structure.

The computational band structure of Ge47MnSe48 revealed a complex interplay of energy bands in Mn-doped GeSe along the high-symmetry paths in the Brillouin zone (Fig. 3c). The presence of Mn dopants introduced additional energy levels, which resonated with the host GeSe electronic band structure. This resonance effect was particularly pronounced near the Fermi level (E = 0 eV), as shown in the red dotted box, suggesting an apparent modification of the electronic structure. The partial density of states (PDOS) plotted for Se, Ge, and Mn atoms further elucidates the electronic contributions from different atomic orbitals, revealing that Mn doping leads to a redistribution of electronic states (Fig. 3d). Specifically, the d-orbital states of Mn exhibited a strong overlap with the Ge and Se p-orbital states, particularly in the energy range around the Fermi level. This overlap was indicative of hybridization between the Mn d-orbitals and the host GeSe orbitals, which can lead to an increase in m* and thus contribute to the optimization of S near room temperature. As the temperature increases, thermal excitation of carriers and shifts in the Fermi level caused the Seebeck coefficient enhancement, which originates from the resonant level and low n, to diminish. This resulted in a reduction of the Seebeck advantage, which was most pronounced at room temperature and weakened gradually at higher temperatures. In the high-temperature cubic phase, the improved Seebeck coefficient in Mn-doped samples may be attributed to their lower n relative to the (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 matrix, as further supported by electrical conductivity discussed later.

Optimized electrical conductivity via lattice symmetry enhancement

The pristine orthorhombic GeSe with low n (~1 × 1016 cm−3) exhibited σ below ~10 S cm−1 across the entire temperature range (Fig. 4a). Alloying with AgBiTe2 substantially increased the conductivity (Supplementary Fig. 8b), reaching ~396 S cm−1 at room temperature in (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1. This enhancement originated from significantly optimized n (Supplementary Fig. 9). Further σ improvement was achieved through Mn-doping (Supplementary Fig. 10b), particularly near room temperature, with a maximum σ of ~643 S cm−1 attained in (GeMn0.003Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 at 300 K.

a Electrical conductivity (σ). b Carrier mobility (μ) as a function of temperature. c Structure symmetry parameters varying in (GeMnySe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 (y = 0–0.007) samples, combining bond angle (α) in the left axis and bond length ratio (l1/l2) in the right axis. d Relative deformation potential (Ξ/Ξ0) and relative carrier mean free path (lc/lc0), which means the Ξ and lc ratio between (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 and (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 matrix.

Although Mn doping reduced n, it markedly enhanced μ at 300 K (Fig. 4b). The augmented μ was identified as the primary contributor to σ optimization near room temperature, attributed to enhanced crystal symmetry and weakened point-defect scattering. The structural symmetry parameters obtained based on XRD refinement provided evidence. The bond angle α increased from ~171° in (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 to ~172.4° in (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1, approaching the ideal value of 180°. Meanwhile, the bond length ratio between l1 and l2 decreased from ~1.12 in (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 to ~1.10 in (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1, moving closer to unity (Fig. 4c). The changes in bond length ratio and bond angle collectively signaled an increase in lattice symmetry, which can promote phonon-electron decoupling.

To quantitatively correlate the enhanced symmetry with electron transport, the deformation potential (Ξ), a descriptor of electron-phonon coupling strength, was calculated. A 30% reduction Ξ in (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 was observed compared with (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 (Ξ0), indicating suppressed electron-phonon coupling (Fig. 4d, left axis). To further elucidate the scattering mechanisms, the carrier mean free path (lc) was calculated, which reflects the cumulative effect of all scattering processes on charge carrier transport. The lc increased by 30% in (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 compared to the undoped sample (lc0), indicating an overall reduction in the total scattering rate (Fig. 4d, right axis). This improvement stems from the combined effects of weakened phonon scattering (due to enhanced lattice symmetry and reduced deformation potential) and suppressed point-defect scattering (resulting from a lower vacancy concentration).

Notably, the comparable extent of improvement in lc (30%) and reduction in Ξ (30%) suggested that the suppression of phonon scattering (driven by symmetry enhancement) dominated the reduced scattering rate and increased μ. Overall, a 1.7-fold enhancement in μ (300 K) was achieved through Mn doping, which could be attributed to the reduction in electron-phonon coupling facilitated by increased lattice symmetry and promoted the increase of σ in rhombohedral phase. During the high-temperature cubic phase, the substitutional site of Mn was expected to change, leading to a degradation in electrical conductivity. Given the inherently high lattice symmetry in cubic phase, the beneficial effect of Mn on phonon-electron decoupling was significantly diminished. The concomitant increase in the Seebeck coefficient further suggested a likely decrease in carrier concentration.

Simultaneously increased electrical conductivity and Seebeck coefficient boosted power factor

To verify the optimized electrical transport properties arising from Mn-doping induced lattice symmetry enhancement and band effect, we calculated the weighted mobility (μW)66,67, which is a comprehensive parameter integrating μ and m* (Fig. 5a). Compared to (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1, Mn-doping substantially increased μW, particularly near room temperature. A twofold enhancement of μW in (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 was observed, confirming the synergistic optimization of μ and m*. This Mn-doping-mediated electrical transport improvement simultaneously elevated both σ and S, resulting in optimized power factor (PF = σS2) across the entire operating temperature range (Fig. 5b). A maximum PF of ~19 μW cm−1 K−2 and a maximum average PF of ~ 17 μW cm−1 K−2 (Fig. 5c) were achieved in (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1, which was a 172% improvement over (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 and a nearly 20-fold enhancement compared to that in pristine GeSe. The PF value of high-symmetry (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 in this work exhibited significant advantages over other reported GeSe-based materials, validating the efficacy of lattice symmetry modulation for electrical transport optimization (Fig. 5d).

Thermal transport properties, ZT and device performance

Regarding thermal transport properties, the Mn-doped samples exhibited higher total thermal conductivity compared with the matrix (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 below 573 K (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 10e). This enhancement was attributed to both increased electronic thermal conductivity (Supplementary Fig. 10h) and slightly elevated lattice thermal conductivity (Supplementary Fig. 10f), resulting from enhanced crystal symmetry and reduced point defect scattering. The quality factor B68, which is proportional to the μW/κlat, serves as a critical metric for thermoelectric performance. The high-symmetry (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 sample exhibited significantly enhanced B factor throughout the measured temperature range, reaching a 166% improvement over the matrix at 300 K (Fig. 6b). This enhancement stemmed from superior electrical transport enabled by lattice symmetry elevation while maintaining low thermal conductivity, ultimately yielding optimized ZT across all working temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 10i). The maximum ZT (ZTmax) increased from ~1.15 in (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 to ~1.50 at 673 K in (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 (Fig. 6c). The average ZT (ZTave) between 300–673 K showed significant enhancement in Mn-doped samples, reaching a maximum value of ~0.94, representing a nearly 30% improvement over the value of ~0.73 (Fig. 6d) in (GeSe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1. Furthermore, three cycles of heating and cooling tests were conducted on (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 sample (Supplementary Fig. 11). The overall ZT value maintained good reproducibility throughout the tests, demonstrating robust thermoelectric performance stability.

a Thermal conductivity (total thermal conductivity κtot and lattice thermal conductivity κlat. b Quality factor (B). c ZT values as a function of temperature, and the inset illustrates the maximum ZT (ZTmax). d Average ZT (ZTave) between 300–673 K. e Power-generation efficiency (η) and f Output power (P) for (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 based single-leg device, with the device photo in the inset.

Correspondingly, the single-leg device fabricated from (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 achieved a maximum energy conversion efficiency (η) of ~6.1% (Fig. 6e) and peak power of ~11.4 mW (Fig. 6f) at ΔT ~ 325 K with a cold-side temperature of 298 K, demonstrating the superior thermoelectric performance of (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1. The relevant output voltage and heat flow are provided in Supplementary Fig. 12.

Discussion

This work demonstrates that precise lattice symmetry manipulation provides a viable pathway to address carrier mobility limitations in low-symmetry thermoelectrics. Through Mn doping in rhombohedral GeSe alloyed with 10% AgBiTe2, undesirable Ge vacancies were compensated and lattice symmetry was significantly enhanced. This precise lattice symmetry strategy suppressed phonon-electron coupling and reduced scattering centers, yielding a 170% mobility enhancement. Concurrently, Mn-induced resonant level increased the density-of-states effective mass and optimized the Seebeck coefficient. The resulting synergistic enhancement of electrical conductivity and Seebeck coefficient delivered an ultrahigh power factor of ~19 μW cm−1 K−2. Critically, the augmented electrical transport properties persist without compromising the intrinsically low lattice thermal conductivity. Breakthrough thermoelectric performance was ultimately achieved: a maximum ZT of ~1.50 was realized at 673 K, attaining ~75% of the calculated theoretical value. The average ZT over 300–673 K reached ~0.94. A record single-leg conversion efficiency of 6.1% was achieved at ΔT = 325 K (Tc = 298 K), validating the practical device potential of GeSe-based thermoelectric material. Furthermore, the present devices exhibit considerable interfacial resistance, exceeding 1.5 mΩ·cm2 at a hot-side temperature of 623 K. A reduction in this contact resistance through interface engineering is likely to yield a significant enhancement in the overall device efficiency.

For decades, low-symmetry thermoelectrics have exhibited intrinsically low lattice thermal conductivity due to structural complexity, yet suffered from fundamental carrier transport constraints. The precision lattice symmetry modulation strategy presented herein enhances electronic transport performance while preserving inherent strong phonon anharmonicity. This targeted decoupling of phonon-electron transport facilitates initial progress in ZT enhancement. The strategy suggests a feasible pathway for incrementally advancing thermoelectric performance in structurally anisotropic systems.

Methods

Sample synthesis

Samples with nominal compositions (GeSe)1-x(AgBiTe2)x (x = 0, 0.08, 0.10, 0.12, 0.14) and (GeMnySe)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1 (y = 0.001, 0.003, 0.005, 0.007) were synthesized from high-purity raw materials sealed in evacuated quartz tubes. High-quality GeSe-based ingots (Supplementary Fig. 13a) were obtained via temperature-gradient growth method in a vertical crystal growth furnace: heated to 1173 K for 5 h and then soaked at this temperature for 12 h, next slowly cooled to 1023 K in 50 h and then cooled to 853 K at a rate of 1 K per hour.

Structural characterization

The powder and bulk X-ray diffraction patterns were obtained with Cu Kα (λ = 1.5418 Å) radiation in a reflection geometry on FRINGE CLASS X-ray diffraction (LANScientific, China) operating at 40 kV and 20 mA. Bulk XRD patterns exhibited significant anisotropy (Supplementary Fig. 14). The presence of diffraction peaks from multiple crystal planes confirmed the polycrystalline nature of the ingot. The Rietveld refinements were performed on the PXRD patterns with the software HighScore to obtain the structure symmetry information. The refinement results are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

The ingot was cut parallel to the temperature gradient direction, then ground and polished. SEM and EDS characterization were performed using an ion beam-scanning electron microscope (FIB-SEM) system (Zeiss Crossbeam 350, Germany). The ingots were polished to ~20 μm-thick, and then thinned to electron-transparent thickness in Gatan Precision Ion Polishing System (PIPS) II using Ar-ion milling. STEM and EDS characterizations were conducted in a Cs-corrector STEM with a cold FEG (JEOL JEM-ARM200F, Japan) operating at 200 kV.

Thermoelectric properties measurements

The obtained ingots were cut and polished into rectangular blocks with size of ~3 × 3 × 8 mm3 along the direction parallel to the temperature gradient during ingot growth (Supplementary Fig. 13b). The Seebeck coefficient and electrical conductivity of the samples were obtained with Ulvac Riko ZEM-3 instrument (Advance Riko, Japan) simultaneously, with an uncertainty of 5%. The slices with size of ~Φ8 × 1 mm3 were fabricated along the same direction as the electrical transport properties measurement. The total thermal conductivity was calculated via κtot = DCpρ, with uncertainty within 15%. The thermal diffusion coefficient D was obtained using LFA457 (Netzsch, Germany). Specific heat capacity Cp was calculated according to Dulong-Petit law (Supplementary Fig. 15). Sample density ρ was inferred from the dimensions and mass of the samples and listed in Supplementary Table 2. The κlat was obtained by subtracting the κele (σLT) from κtot, where the Lorenz number (L) and other relevant parameters are provided in the Supplementary Figs. 8 and 10. Overall, the uncertainty of ZT values obtained by the final calculation was within 20%. Furthermore, thermoelectric properties along the direction perpendicular to the temperature gradient were also presented to fully characterize the anisotropic behavior of the samples (Supplementary Figs. 16 and 17).

Hall measurement

Hall coefficients (RH) were measured on specimens of ~8 × 8 × 0.7 mm3 by a Hall system (Lake Shore 8400 Series, Model 8404, USA) at 300 K. Carrier density (n) and carrier mobility (μ) were obtained through n = 1/(eRH) and μ = σRH.

Single-leg power generation efficiency test

The single-leg device of ~2 × 3 × 7 mm3 was fabricated with an optimal composition of (GeMn0.005Se)0.9(AgBiTe2)0.1, with the upper and lower surfaces electroplated with nickel as barrier layers and silver paste as contact material. Output power, conversion efficiency, and heat flux were measured through TE-X-MS (developed by Xi’an Jiaotong University, China). The cold-side temperature (Tc) was stabilized at 298 K, and the hot-side temperature (Th) ranged from 483 K to 623 K.

Computational details

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations with projected augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotential formalism were performed within the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional form of generalized gradient approximation (GGA) method as implemented in Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP) software. In this work, A plane wave basis with a convergence kinetic energy cut-off of 550 eV was adopted in all calculations. The Brillouin Zone (BZ) was sampled using the Monkhorst-Pack k-mesh of 15 × 15 × 5 with the energy convergence criterion of 10−8 eV. The crystals were fully optimized within the Hellmann-Feynman force convergence criterion of 10−2 eV/Å. The Ge47MnSe48 supercell model (Supplementary Fig. 18) was performed for electronic band calculations (lattice parameters in Supplementary Table 3). Considering the symmetry change due to the Mn substitution, the electronic band structure was unfolded to primitive cell by using the VASPKIT code.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files.

References

Bell, L. E. Cooling, heating, generating power, and recovering waste heat with thermoelectric systems. Science 321, 1457–1461 (2008).

Bu, Z. et al. A record thermoelectric efficiency in tellurium-free modules for low-grade waste heat recovery. Nat. Commun. 13, 237 (2022).

Zuo, W. et al. Atomic-scale interface strengthening unlocks efficient and durable Mg-based thermoelectric devices. Nat. Mater. 24, 735–742 (2025).

Liu, D. et al. Lattice plainification advances highly effective SnSe crystalline thermoelectrics. Science 380, 841–846 (2023).

Han, C. G. et al. Giant thermopower of ionic gelatin near room temperature. Science 368, 1091–1098 (2020).

Xu, L., Yin, Z., Xiao, Y. & Zhao, L. D. Interstitials in thermoelectrics. Adv. Mater. 36, e2406009 (2024).

Deng, T. et al. High-throughput strategies in the discovery of thermoelectric materials. Adv. Mater. 36, e2311278 (2024).

Qin, Y. et al. Grid-plainification enables medium-temperature PbSe thermoelectrics to cool better than Bi2Te3. Science 383, 1204–1209 (2024).

Wei, T. R., Qiu, P., Zhao, K., Shi, X. & Chen, L. Ag2Q-based (Q = S, Se, Te) silver chalcogenide thermoelectric materials. Adv. Mater. 35, 2110236 (2022).

Ke, S. et al. Nanomagnetism triggering carriers double-resistance conduction and excellent flexible thermoelectrics. Adv. Mater. 37, 2414511 (2025).

Ai, X. et al. High-performance ZrNiSn-based half-Heusler thermoelectrics with hierarchical architectures enabled by reactive sintering. Nat. Commun. 16, 6497 (2025).

Li Y.-Z. et al. Multi-scale hierarchical microstructure modulation towards high room temperature thermoelectric performance in n-type Bi2Te3-based alloys. Mater. Today Nano 11, 100340 (2023).

Ge, B. et al. Engineering an atomic-level crystal lattice and electronic band structure for an extraordinarily high average thermoelectric figure of merit in n-type PbSe. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 3994–4008 (2023).

Xie, L. et al. Highly efficient thermoelectric cooling performance of ultrafine-grained and nanoporous materials. Mater. Today 65, 5–13 (2023).

Biswas, K. et al. High-performance bulk thermoelectrics with all-scale hierarchical architectures. Nature 489, 414–418 (2012).

Pei, Y. et al. Convergence of electronic bands for high performance bulk thermoelectrics. Nature 473, 66–69 (2011).

Luo, H. et al. Metavalent alloying and vacancy engineering enable state-of-the-art cubic GeSe thermoelectrics. Nat. Commun. 16, 3136 (2025).

Zhao, K. et al. Structural modularization of Cu2Te leading to high thermoelectric performance near the Mott-Ioffe-Regel limit. Adv. Mater. 34, e2108573 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Realizing p-type performance in low-thermal-conductivity BiSbSe3 via lead doping. Rare Met. 42, 3601–3606 (2023).

Wang, S., Qiu, Y. & Zhao, L.-D. BiSbSe3: A promising Te-free thermoelectric material. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 260503 (2023).

Shi, H. et al. Crystal symmetry modification enables high-ranged in-plane thermoelectric performance in n-type SnSe crystals. Nat. Commun. 16, 1788 (2025).

Zhan, S. et al. Insight into carrier and phonon transports of PbSnS2 crystals. Adv. Mater. 36, 2412967 (2024).

Jiang, B. et al. The curious case of the structural phase transition in SnSe insights from neutron total scattering. Nat. Commun. 14, 3211 (2023).

Shi, H. et al. Contrasting strategies of optimizing carrier concentration in bulk InSe for enhanced thermoelectric performance. Rare Met. 43, 4425–4432 (2024).

Xia, Y., Ozoliņš, V. & Wolverton, C. Microscopic mechanisms of glasslike lattice thermal transport in cubic Cu12Sb4S13 tetrahedrites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 085901 (2020).

Ren, Q. et al. Extreme phonon anharmonicity underpins superionic diffusion and ultralow thermal conductivity in argyrodite Ag8SnSe6. Nat. Mater. 22, 999–1006 (2023).

Qin, B., Wang, D. & Zhao, L. D. Slowing down the heat in thermoelectrics. InfoMat 3, 755–789 (2021).

Tan, G., Zhao, L.-D. & Kanatzidis, M. G. Rationally designing high-performance bulk thermoelectric materials. Chem. Rev. 116, 12123–12149 (2016).

Chen, G., Dresselhaus, M. S., Dresselhaus, G., Fleurial, J. P. & Caillat, T. Recent developments in thermoelectric materials. Int. Mater. Rev. 48, 45–66 (2013).

Qin, B. & Zhao, L. Carriers: the less, the faster. Mater. Lab 1, 1–3 (2022).

Sining, W., Lizhong, S., Qiu, Y., Xiao, Y. & Zhao, L.-D. Enhanced thermoelectric performance in Cl-doped BiSbSe3 with optimal carrier concentration and effective mass. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 70, 67–72 (2021).

Xin, J. et al. Valleytronics in thermoelectric materials. npj Quantum Mater. 3, 9 (2018).

Kleinke, H. New bulk materials for thermoelectric power generation: clathrates and complex antimonides. Chem. Mater. 22, 604–611 (2009).

Siddique, S. et al. Optimization of thermoelectric performance in p-type SnSe crystals through localized lattice distortions and band convergence. Adv. Sci. 12, 2411594 (2024).

Bai, S., Qin, B. & Zhao, L. Role of carrier mobility in decoupling electron–phonon transport contradiction. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 53, 733–741 (2025).

Qin, Y., Xiao, Y. & Zhao, L.-D. Carrier mobility does matter for enhancing thermoelectric performance. APL Mater. 8, 010901 (2020).

Zheng, Y. et al. Carrier-phonon decoupling in perovskite thermoelectrics via entropy engineering. Nat. Commun. 15, 7650 (2024).

Zheng, S. et al. Symmetry-guaranteed high carrier mobility in quasi-2D thermoelectric semiconductors. Adv. Mater. 35, e2210380 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Modulating structures to decouple thermoelectric transport leads to high performance in polycrystalline SnSe. J. Mater. Chem. A 12, 144–152 (2024).

Qin, B. et al. Realizing high thermoelectric performance in p-type SnSe through crystal structure modification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 1141–1149 (2019).

Su, L. et al. High thermoelectric performance realized through manipulating layered phonon-electron decoupling. Science 375, 1385–1389 (2022).

Hao, S. Q., Shi, F. Y., Dravid, V. P., Kanatzidis, M. G. & Wolverton, C. Computational prediction of high thermoelectric performance in hole doped layered GeSe. Chem. Mater. 28, 3218–3226 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Thermoelectric properties of GeSe. J. Mater. 2, 331–337 (2016).

Duan, B. et al. The role of cation vacancies in GesE: stabilizing high-symmetric phase structure and enhancing thermoelectric performance. Adv. Energ. Sust. Res. 3, 2200124 (2022).

Yan, M. et al. Synergetic optimization of electronic and thermal transport for high-performance thermoelectric GeSe–AgSbTe2 alloy. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 8215–8220 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Structure-dependent thermoelectric properties of GeSe1-xTex (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.5). ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 41381–41389 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Phase modulation enabled high thermoelectric performance in polycrystalline GeSe0.75Te0.25. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2111238 (2022).

Yao, W. et al. Two-step phase manipulation by tailoring chemical bonds results in high-performance GeSe thermoelectrics. Innovation 4, 100522 (2023).

Guo, M. et al. Achieving superior thermoelectric performance in Ge4Se3Te via symmetry manipulation with I–V–VI2 alloying. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2313720 (2024).

Huang, Z. et al. High thermoelectric performance of new rhombohedral phase of GeSe stabilized through alloying with AgSbSe2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 14113–14118 (2017).

Sarkar, D. et al. Ferroelectric instability induced ultralow thermal conductivity and high thermoelectric performance in rhombohedral p-Type GeSe Crystal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 12237–12244 (2020).

Sarkar, D. et al. Metavalent bonding in GeSe leads to high thermoelectric performance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 10350–10358 (2021).

Zhang, M. et al. Compositing effect leads to extraordinary performance in GeSe-based thermoelectrics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2500898 (2025).

Zhang, M. et al. High-performance GeSe-based thermoelectrics via Cu-Doping. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2411054 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Crystal symmetry enables high thermoelectric performance of rhombohedral GeSe(MnCdTe2). Nano Energy 100, 107434 (2022).

Hu, L. et al. In situ design of high-performance dual-phase GeSe thermoelectrics by tailoring chemical bonds. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2214854 (2023).

Yu, Y. et al. Doping by design: enhanced thermoelectric performance of GeSe alloys through metavalent bonding. Adv. Mater. 35, e2300893 (2023).

Huang, Y. et al. Manipulation of metavalent bonding to stabilize metastable phase: a strategy for enhancing zT in GeSe. Interdiscip. Mater. 3, 607–620 (2024).

Lyu, T. et al. Advanced GeSe-based thermoelectric materials: Progress and future challenge. Appl. Phys. Lett. 11, 031323 (2024).

Dong, J. et al. High thermoelectric performance in rhombohedral GeSe-LiBiTe2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 17355–17364 (2024).

Roychowdhury, S., Ghosh, T., Arora, R., Waghmare, U. V. & Biswas, K. Stabilizing n-type cubic GeSe by entropy-driven alloying of AgBiSe2: ultralow thermal conductivity and promising thermoelectric performance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 130, 15387–15391 (2018).

Hong, M., Lyu, W., Wang, Y., Zou, J. & Chen, Z. G. Establishing the golden range of Seebeck coefficient for maximizing thermoelectric performance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 2672–2681 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. Quadruple-band synglisis enables high thermoelectric efficiency in earth-abundant tin sulfide crystals. Science 387, 202–208 (2025).

Lyu, T. et al. Intensive widmannstätten nanoprecipitates catalyze SnTe with state-of-the-art thermoelectric performance. Adv. Mater. 37, 2503918 (2025).

Zhong, J. et al. Nuanced dilute doping strategy enables high-performance GeTe thermoelectrics. Sci. Bull. 69, 1037–1049 (2024).

Qin, B., He, W. & Zhao, L.-D. Estimation of the potential performance in p-type SnSe crystals through evaluating weighted mobility and effective mass. J. Mater. 6, 671–676 (2020).

Snyder, G. J. et al. Weighted mobility. Adv. Mater. 32, e2001537 (2020).

He, W., Qin, B. & Zhao, L.-D. Predicting the potential performance in p-type SnS crystals via utilizing the weighted mobility and quality factor. Chin. Phys. Lett. 37, 087104 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52472184), the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (52525101), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52450001, 12404037, 52401258, and 52402221), the International Cooperation and Exchange of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52411540237), the Tencent Xplorer Prize, the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program CPSF under Grant Number GZC20242150, the Taiyuan University of Science and Technology Scientific Research Initial Funding (20232094), the 10th Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST, the Young Outstanding Talent of the “San Jin Talents” Support Plan of Shanxi Province (992025025), the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (202403021212122), the funding for Outstanding Doctoral Research in Jin (20242010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.W., Y.Q. (Yuting Qiu), and L.-D.Z. conceived the research framework, synthesized the samples, conducted experimental characterization, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Y.W. (Yi Wen) performed microstructural analysis. S.B. executed density functional theory calculations. L.S. evaluated the thermoelectric conversion efficiency of the device. Y.Q. (Yongxin Qin), Y.Z., and Y.W. (Yaokun Wang) contributed to thermoelectric parameter analysis. All authors critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S., Wen, Y., Bai, S. et al. Enhanced Lattice Symmetry via Mn Doping Boosts Electrical Transport Performance in Rhombohedral GeSe Thermoelectric Materials. Nat Commun 16, 10377 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65364-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65364-0