Abstract

Excitons are bond states of electron-hole pairs formed through Coulomb interaction. While excitonic phases have been widely studied in semiconductors and quantum Hall double-layers, prior works largely focus on bulk systems with large number of excitons, limiting their applications in quantum devices. Here, employing the approach of quantum Hall antidot with two spatially separated edge channels, we demonstrate a type of quantum Hall quasiparticle exciton which represents a quantum-coherent bound state of an electron and a hole situated on their corresponding edges coupled through intralayer tunneling and Coulomb interaction. This approach allows localization and electrical tuning of individual quantum Hall excitons. Quantum-coherent dynamics of exciton are observed in the gate-dependence of antidot conductance peaks near the electron-hole resonance, which signifies a quantum superposition of vacuum- and electron-hole pairing states. Modeling the electron-hole pair as a coupled two-level system, semi-quantitative understanding of experimental observations is achieved. This work opens avenues for creating quantum systems of multiple quantum Hall quasiparticles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solid-state systems have been a major area for the development of quantum devices and circuits owing to their advantages in scalability, electrical control, and constant progress in size reduction down to the nanoscale level. This combination of characteristics allows manipulation of individual quasiparticles associated with the states of charge1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, spin9,10,11,12,13,14, magnetic flux and superconducting phase15,16,17,18,19,20,21, or more complex combined degrees of freedom. In this context, a two-dimensional (2D) electron quantum Hall (QH) system has been a unique platform that, in addition to the basic integer charge states, hosts the more exotic quasiparticles associated with fractional QH (FQH) abelian and non-abelian anyonic states22,23,24,25,26, and excitons in double-layer QH systems27,28,29,30,31,32 which exhibit Bose–Einstein condensation (see, e.g., ref. 33) and unusual quantum solids34. Evidence of the anyonic exchange statistics was obtained in the edge modes-based Fabry-Perot QH interferometer35,36,37,38,39 and in the anyon collisions40.

Another experimental platform that utilizes QH edge modes is QH antidot41,42,43 in which the edge modes encircle the maximum of an electrostatic potential, forming closed orbits. Quantized energy levels obtained in this way can localize individual QH quasiparticles, including those with fractional charge and statistics, and provide the basis for their manipulations. Coulomb-blockade-type correlations among the quasiparticles on the antidot, combined with the discrete antidot energy spectrum, control the number of quasiparticles and minimize the phase space for scattering, hence enhancing quantum coherence. Resonant tunneling through the antidot energy levels has successfully demonstrated the fractional charges of FQH quasiparticles44,45,46. The fractional exchange statistics of the anyonic quasiparticles are also theorized to be observable through transport measurement in multi-antidot molecule systems47. Beyond single antidot atoms, however, while there has been experimental evidence of the double-antidot transport in accidental48 and defined42 structures, creating controllable and quantum-coherent multiple QH quasiparticle systems remains limited and challenging.

One of the archetypal interacting multi-particle quantum systems is an exciton, a bound state of an electron-hole pair formed through Coulomb attraction. In QH double-layers, interlayer Coulomb interactions can induce excitonic states from the spatially separated electrons and holes on their corresponding layers, forming a bosonic condensate28,29,30,31,32. QH quasiparticle-associated excitons offer the potential of creating quantum states combining interaction effects and non-trivial quantum statistics. However, to date, the study on QH excitons has been largely limited to the bulk systems with a large number of excitons.

In this work, employing the platform of a quantum Hall antidot with two spatially separated electron- and hole-edge channels, we demonstrate a coherent and interacting quantum state of an individual localized exciton. Quantum-coherent dynamics of excitons are observed in the gate dependence of antidot conductance peaks near the electron-hole resonance, which signifies a quantum superposition of vacuum- and electron-hole pairing states. Modeling the electron-hole pair as a coupled two-level system, semi-quantitative agreement with the experimental observations is achieved.

Results

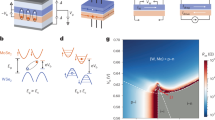

Figure 1a illustrates the basic principle of such a QH antidot exciton in comparison with a conventional exciton. A conventional exciton forms in the free space of a semiconductor by exciting a valence electron. The resulting hole in the valence band and the excited electron form an excitonic pair through Coulomb interaction, with energy lower than the conduction band edge. A QH antidot exciton, on the other hand, forms in a pair of closely placed QH antidot edge modes hosting an electron and a hole. The quantum tunneling of an electron from the hole-edge mode to the electron edge mode creates a coherent electron-hole pair, which, through Coulomb interaction, forms an excitonic state with reduced ground state energy. In contrast to the interlayer QH excitons (Fig. 1b), a QH antidot exciton is localized individually and created via intralayer Coulomb interaction and tunneling.

a A schematic showing the principle of the QH edge mode exciton formed by intralayer Coulomb interaction, and its comparison with the conventional exciton. The red and the blue arrowed circles correspond to the orbits of the electron and hole chiral edge modes. b Schematic showing the principle of the QH bilayer exciton, formed by interlayer Coulomb interaction. c A schematic of the sample consists of a heterostructure of patterned few-layer graphite (FLG) top gate, hBN, monolayer graphene (MLG), hBN, and FLG bottom gate. d QH edge modes on a graphene channel, including the bulk edge modes and the top gate-defined edge modes at the couplers and the antidot. The edge modes form at the boundaries of different filling factors. The red and blue arrowed lines correspond to the electron and hole-edge modes. The dotted arrows indicate where tunneling can happen.

While Coulomb-blockade transport of individual excitons has been studied in quantum dots49,50,51 as one of the approaches to the development of “on-demand” single-photon sources, and continue to attract practical interest up to now (see, e.g., ref. 52 and references therein), the distinct element added by our antidot structure to the manipulation of the individual excitons is quantum coherence between the electron and the hole parts of the exciton. Such quantum coherence within the individual excitons is potentially useful for quantum information applications, e.g., as an interface for quantum information transfer between the photons and the antidot qubits. From the point of view of qubits, electron-hole attraction within the exciton enhances the energy gap between the qubit states beyond the typically not-so-large tunnel coupling of these states, something that would be beneficial in many different contexts, most directly, in the case of the ground state quantum computing53.

The experimental platform studied in this work is a graphene-hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) heterostructure illustrated in Fig. 1c, with hBN encapsulated monolayer graphene tunable by two graphite gates (see Supplementary Information (SI)). The bottom graphite gate tunes the carrier density uniformly throughout the whole monolayer graphene channel. The top graphite gate is patterned with an antidot and two couplers etched out. The diameter of the antidot here is \(D\simeq 180{{{\rm{nm}}}}\). The couplers point toward the antidot with an edge-edge distance of ~80 nm at the closest points. Combining the top and bottom gates, carrier density and QH filling factor can be separately adjusted inside the antidot and coupler region, \(\nu=\frac{{nh}}{{eB}}\), and outside, \({\nu }^{{\prime} }=\frac{{n}^{{\prime} }h}{{eB}}\). Here \(n\) and \({n}^{{\prime} }\) are the corresponding local carrier densities, \(h\) is Planck’s constant, \(e\) is the electron charge, and \(B\) is the external magnetic field. When the corresponding numbers of the filled Landau levels (\(f\) and \({f}^{{\prime} }\), positive on the electron side and negative on the hole side) are different between the two regions, QH edge modes form at the boundaries of the antidot and the couplers. As a result of quantum confinement (particle in a ring), the energy of the QH edge modes encircling the antidot becomes quantized:

with energy level spacing: \(\Delta \varepsilon=\frac{2\hslash {v}_{{QH}}}{{D}_{{QH}}}\) in a fixed magnetic field43,46 (see SI). Here, \(j\) is an integer which indexes the quantization energy levels, \({v}_{{QH}}\) is the QH edge mode velocity, \({D}_{{QH}}\) is the effective diameter of the antidot edge mode, \(\Phi\) is the magnetic flux through the antidot, and \({\varPhi }_{0}=\frac{h}{e}\) is the magnetic flux quantum. The occupation of the energy levels can be tuned through the gate voltage, while a magnetic flux shifts the manifold of the levels, manifesting the Aharonov–Bohm effect. When the distance between the couplers’ and the antidot’s edge modes is sufficiently small, coupling between the bulk edge modes through the antidot takes place and lowers the transverse resistance \({R}_{T}\equiv \frac{{V}^{+}-{V}^{-}}{I}\) (I being the electric current flowing through the I+ and I− electrodes) which can be characterized through the transport measurement in the configuration shown in Fig. 1d. In the regime when the bulk graphene is tuned to a QH plateau with quantized resistance \({R}_{{QH}}\), the antidot tunneling conductance can be measured from the corresponding resistance valley: \({G}_{{AD}}=\frac{1}{{R}_{T}}-\frac{1}{{R}_{{QH}}}\).

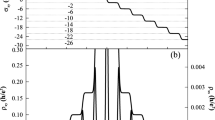

The basic signature of QH antidot tunneling is illustrated in Fig. 2a under the simplest configuration where the antidot and the couplers are within the \(f=0\) insulating gap, while the outside bulk is on the \({f}^{{\prime} }=-2\) QH plateau. Here, consistent with the prior studies on physically etched QH antidots43,46, the emergence of quasi-periodic resistance valleys on a QH plateau, associated with tunneling through discrete antidot levels, is observed in our gate-defined QH antidot device. Each resistance valley corresponds to adding a single hole charge onto the antidot43. Figure 2b goes beyond the linear conductance and demonstrates the top gate voltage and bias voltage dependencies of resistance (charge stability diagram). The dotted lines highlight the discernible Coulomb diamonds and excited states. We note that compared to typical quantum dots, the Coulomb diamond features are less pronounced in the QH antidot. This may be due to (1) break-down of the quantized plateau resistance under finite bias voltages which adds a bias-dependent background; (2) small Coulomb energy due to the relatively large antidot size and screening from the hBN dielectric layers; (3) asymmetric tunneling amplitude between the antidot and the two coupler, which results in nearly invisible resonant tunneling traces at the positive-sloped boundaries of the Coulomb diamonds. From this diagram, the on-site Coulomb repulsion energy and quantization energy spacing on a \({f}^{{\prime} }=-2\) QH plateau in a 1 T magnetic field can be estimated to be \(U\simeq 1{{{\rm{meV}}}}\) and \(\Delta \varepsilon \simeq 0.7{{{\rm{meV}}}}\), respectively. More examples of charge stability diagrams and Coulomb diamonds showing a similar energy scale can be found in the SI. Based on the quantization energy, the QH edge mode velocity of \({v}_{{QH}}=\frac{{\Delta \varepsilon D}_{{QH}}}{2\hslash }\simeq {10}^{5}{{{\rm{m}}}}/{{{\rm{s}}}}\) can be estimated, which is in qualitative agreement with the previous reports on edge mode velocity in QH interferometers54,55. The measured on-site Coulomb energy of one edge state can be understood considering a localized ring of charge density with thickness on the order of the magnetic length \({l}_{B}=\sqrt{\frac{\hslash }{{eB}}}\), and partially screened by the nearby gate electrodes: \(U=\frac{{e}^{2}}{2\pi {\epsilon }_{{BN}}{\epsilon }_{0}L}{{{\mathrm{ln}}}}\left[{\left(1+\frac{{4{t}_{{BN}}}^{2}}{{{l}_{B}}^{2}}\right)}^{1/2}+\frac{{2t}_{{BN}}}{{l}_{B}}\right]\) (see SI). Here, \({\epsilon }_{{BN}}\simeq 3.5\pm 0.2\) is the dielectric constant of hBN, and \({t}_{{BN}}\simeq 10{{{\rm{nm}}}}\) is the effective hBN thickness for the screening effect from both graphite gates. The observed Coulomb energy of \(U\simeq 1{{{\rm{meV}}}}\) suggests an antidot mode circumference of \(L\simeq 600{{{\rm{nm}}}}\), i.e., \({D}_{{QH}}\simeq 190\pm 10{{{\rm{nm}}}}\). This is consistent with the similar but slightly smaller diameter of the antidot in the top graphite gate (\(D\simeq 180{{\mathrm{nm}}}\)).

a Resistance oscillations on the \({f}^{{\prime} }=-2\) plateau from antidot tunneling, under zero back gate voltage. b Charge stability diagram for antidot tunneling on the \({f}^{{\prime} }=-2\) plateau, showing the bias voltage (\({V}_{{bias}}\)) and \({V}_{{TG}}\) dependence of the differential resistance. The dotted lines are guides to the eyes to some of the conductance peaks. Here back gate voltage is \({V}_{{BG}}=0.08{{{\rm{V}}}}\). c Tuning antidot tunneling through the dual gates. The color map shows the \({{{{\rm{\nu }}}}}^{{\prime} }\) dependence of transverse resistance on the lower density side of the \({f}^{{\prime} }=-2\) plateau over a wide range of \({{{\rm{\nu }}}}\). The bright-colored dots correspond to the resistance valleys on a background of the \({f}^{{\prime} }=-2\) plateau. Four characteristic regimes are labeled, with their corresponding Landau level energy diagrams illustrated. The Landau level diagrams are across the center of the antidot and couplers, reaching the bulk edges of the graphene channel, as indicated by the dotted line on the device schematic in the color map inset. In the inset, the blue and the apricot regions illustrate the antidot/couplers and the bulk regions, respectively. In the Landau level diagrams, the red and blue lines correspond to electron and hole Landau levels, respectively. The number on each Landau level indicates its degeneracy. Around the antidot, the Landau level energy is quantized into discrete energy levels due to the quantum confinement effect on the closed edge modes. In regimes I and IV, antidot tunneling is suppressed by the large tunneling distances between the edges. Regimes II and III allow antidot tunneling.

The gate-control of the antidot tunneling is illustrated in Fig. 2c. The main panel shows the tunneling resistance versus the filling inside (\(\nu\)) and outside (\(\nu\)’) the antidot/couplers regions. Sharp bright dots (resistance valleys) signify the antidot tunneling on the QH plateau of \({R}_{{QH}}=\frac{h}{2{e}^{2}}\) (\({f}^{{\prime} }=-2\)), coarsely sampled over a wide range of filling factor \(\nu\) in the antidot/couplers regions that are tuned by the back gate. Four characteristic (\({f,f}^{{\prime} }\)) combinations are highlighted with their corresponding Landau level energy diagrams. The spatial profiles of the Landau level energy (in relation to the chemical potential) are tuned through the patterned top gate, while the back gate uniformly shifts the chemical potential throughout the whole channel. The QH edge modes are located where the Landau levels cross the chemical potential \(\mu\). The edge mode tunneling strength depends sensitively on the spatial separation between the coupler and antidot edge modes, adjusted by the dual gates. To enable coupler-antidot tunneling, the tunneling distance between the coupler edge mode and the antidot edge mode needs to be near its minimum when the Landau Level associated with these edge modes is tuned slightly across the chemical potential. Directly relevant to the discussions below and for \(f{f}^{{\prime} }\le 0\), this corresponds to the lower carrier density end of a QH plateau. A more detailed discussion of the edge mode tunneling in these four regimes is given in the SI.

Having demonstrated the basic principle of QH antidot operation, we next focus on the symmetry-breaking \({f}^{{\prime} }=-1\) state in a magnetic field \(B=3.3{{{\rm{T}}}}\). Figure 3a shows the top gate voltage dependence of the transverse resistance \({R}_{T}\), where quasi-periodic resistance valleys associated with coupler-antidot tunneling of the hole side of the zeroth Landau level edge modes emerge on the plateau background of \({R}_{{QH}}=\frac{h}{{e}^{2}}\). Following Eq.(1), the gate voltage positions of these valleys shift with changing magnetic field at a rate of one resistance valley per magnetic flux quantum \({\varPhi }_{0}\) through the effective area of the antidot: \(\frac{\delta {V}_{{TG}}}{\Delta {V}_{{TG}}}=-\frac{\delta \varPhi }{{\varPhi }_{0}}=-\frac{\delta B\pi {D}_{{QH}}^{2}}{{4\varPhi }_{0}}\). Here, \(\delta {V}_{{TG}}\) is the shift of a resistance valley in top gate voltage under a changing magnetic field, \(\Delta {V}_{{TG}}\) is the top gate voltage period of the resistance valleys, \(\delta B\) and \(\delta \Phi\) are the changes of magnetic field and flux, respectively. From the magnetic shift of the resistance valleys, \({D}_{{QH}}\approx 230{{\mathrm{nm}}}\) can be estimated, suggesting the edge mode to situate ~25 nm away from the physical antidot edge of the top graphite gate. With this effective diameter, we can also estimate the number of charges added to the antidot per gate period: \(\Delta N=\frac{{c}_{{TG}}{{{\rm{\pi }}}}{D}_{{QH}}^{2}}{4e}\Delta {V}_{{TG}}=1.04\pm 0.06\) (\({c}_{{TG}}=\frac{{\epsilon }_{0}{\epsilon }_{{BN}}}{{d}_{{hBN}}}\) is the area capacitance of the top gate with \({d}_{{hBN}}=18{{{\rm{nm}}}}\) being the thickness of the hBN layer between the graphene can the top graphite gate), consistent with the addition of single fundamental charges in the integer QH regime46. All these observations further confirm the antidot nature of the resistance valleys.

a Top gate-dependent transverse resistance showing quasi-periodic valleys on the \({f}^{{\prime} }=-1\) plateau. Inset: shift of resistance oscillations under varying magnetic fields. The curves are displaced on the y-axis for clarity. b Color-mapped antidot tunneling conductance versus doping inside and outside the antidot. The yellow dotted straight lines trace the random jumps in conductance peak traces along constant top gate voltages. The black dotted curves are guides to the eyes for the anti-crossing-like features, which are associated with tunneling through the electron-hole pairing states. The yellow dotted rectangle highlights a pronounced exciton state, which is discussed quantitatively in the text. c Antidot tunneling conductance curves inside the yellow dotted rectangle in (b), shifted in the y-axis direction for clarity. The dashed lines highlight the evolution of the position of the conductance peaks. d Qualitative schematic showing gate tuning of the antidot levels for the outer (hole) and inner (electron) antidot modes. The red and blue lines correspond to electron- and hole-associated levels, respectively. Bottom right plot: the energy levels spread out with increasing magnitude of top gate voltage. Due to the energy offset between the \({f}^{{\prime} }=\pm 1\) Landau levels (\({\varepsilon }_{g}\)), the electron- and hole- antidot levels can cross each other, resulting in resonances and pairing. Here we highlight the shift of an electron level and a hole level (thick red and blue lines in the \(E({V}_{{TG}})\) plot and the red and blue solid circles in the Landau level diagrams) under changing top gate voltage, with corresponding Landau level diagrams at top gate voltages of 0, \({V}_{1}\) and \({V}_{2}\) shown in panels ①, ②, and ③. Panel ① inset: device schematic where Landau level diagrams are along the dotted line. The blue and the apricot regions illustrate the antidot/couplers and the bulk regions, respectively.

The main finding of this work is shown in Fig. 3b, which illustrates the evolution of the antidot tunneling conductance oscillations on the lower density side of the \({f}^{{\prime} }=-1\) plateau over a range of filling factor \(\nu\) in the antidot/coupler regions. For clarity, the horizontal axis is set to \({V}_{{TG}}+{\alpha }_{{AD}}{V}_{{BG}}\), which directly depicts the electrostatic doping at the outside vicinity of the antidot, where \({\alpha }_{{AD}}=0.53\) is the effective capacitance ratio between the bottom and the top gates for antidot charging (see SI). The antidot tunneling conductance peaks appear as near-vertical stripes with abrupt jumps. Most interestingly, anti-crossing-like features are observed, highlighted by the black dotted curves in Fig. 3b. These features are generally present under the \(\left(f,{f}^{{\prime} }\right)=(1,-1)\) configuration, although the regularity of their locations is disturbed by a few random slides occurring along the yellow dotted straight lines in Fig. 3b. The source of these random slides is identified as quantum dot-like charge trapping centers located near the antidot edge on the top graphite gate (see SI), which is not the focus of this work. In the discussions below, we focus on the anti-crossing feature highlighted by the yellow box in Fig. 3b, for which the individual curves of the antidot conductance are shown in Fig. 3c. As will be argued below, after developing a quantitative model, the anti-crossing-like features observed here originate not from atomic-scale traps, but from the formation of a gate-defined pair of electron-hole edges coupled both by tunneling amplitude and Coulomb attraction.

Anti-crossing features are typically associated with level coupling. In high-quality graphene samples, symmetry-breaking interaction effects lift the 4-fold degeneracy of the zeroth Landau level. With a well-developed \({f}^{{\prime} }=-1\) plateau and insulating behavior at the charge neutrality, the inner electron and the outer hole-edge modes are expected to coexist and be spatially separated by a gapped region. Increasing the magnitude of the top gate voltage, the antidot-defining potential profile becomes increasingly sharp, resulting in antidot edge modes with larger edge mode velocities (\({v}_{{QH}} \sim \frac{{dV}}{{dr}}\)), hence larger quantization energy level spacing (\(\Delta \varepsilon=\frac{2\hslash {v}_{{QH}}}{{D}_{{QH}}}\)). As a result, both the outer hole- and the inner electron-antidot edge modes have their quantization energy levels fan out with increasing top gate voltage. Since the manifolds of hole- and the electron- quantization energy levels are offset by the charge neutrality gap, the energy levels of the outer- and inner- modes with different indices will have different shifting rates under changing top gate voltage, and will cross each other as illustrated by Fig. 3d. As a result, just from the top gate voltage, some of the hole- and electron levels can be tuned to align with and cross each other, creating tuning and detuning of an electron-hole resonance. With the back gate tuning the chemical potential throughout the channel, one can ensure tunneling through the antidot under the conditions of the electron-hole resonance. A more analytical discussion of the gate voltage dependence of the resonance can be found in the SI.

To understand the energy spectrum of the coupled electron and hole-edge modes, we consider a basic model of graphene QH antidot43 extended to two coupled co-centric edge modes, shown in Fig. 4a. Here, \(\Gamma\) is the tunneling rate between the couplers and the outer hole mode. The inner electron mode is not coupled directly to the couplers, but to the hole mode with a tunneling amplitude \(\Delta\). The energy spectra of the two edge modes are quantized, and therefore, in the main approximation, the tunnel coupling between the two modes is coherent. Besides tunneling, electrons and holes also experience Coulomb interaction, which can be described in the constant-interaction approximation for each individual mode:

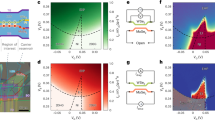

a Transport model of the antidot made of two coupled electron and hole-edge modes. b Diagram of charging phases with different electron-hole configurations as the ground states, represented by different colors. The dashed line corresponds to \(\xi=0\), along which \(\left|00\right\rangle\) and \(\left|11\right\rangle\) are degenerate and therefore are mixed strongly by the tunnel amplitude \(\Delta\). (c) and (d) illustrate color-coded tunneling conductance versus top and back gate voltages, computed with the transport model with \(u=0.7{{{\rm{meV}}}}\) and \(\Delta=1{{{\rm{meV}}}}\), and with \(u=0.7{{{\rm{meV}}}}\) and \(\Delta=0.4{{{\rm{meV}}}}\), respectively. Correspondingly, the insets illustrate the real space separation of the two modes under these parameters. In (c), the labeled gray arrows indicate tunneling processes illustrated in (e). Processes i and iv are between states with electron and hole levels detuned. Processes ii and iii involve tunneling through the excitonic state, which is a superposition of \(\left|00\right\rangle\) and \(\left|11\right\rangle\), with dotted ovals indicating the components that contribute to the tunneling conductance. f Ground state energy reduction from that of the non-interacting isolated electron-hole pair.

Here, \({n}_{h}\) and \({n}_{e}\) are the numbers of particles in the hole and electron mode, respectively, \({U}_{h,e}\) are the corresponding interaction constants for the two modes, and \(u > 0\) is the magnitude of the Coulomb electron-hole attraction between the two edges.

Similar to the basic Coulomb-blockade model for tunneling through the quantum dots, Eq.(2) leads to a periodic response of the edges to the two gate voltages that control \({n}_{h}\) and \({n}_{e}\). For the outer edge, this translates into a quasi-periodic sequence of the resonant tunneling peaks of the antidot conductance \({G}_{{AD}}={dI}/d{V}_{{bias}}{|}_{{V}_{{bias}}=0}\), with each peak occurring at the bias conditions at which the number of holes in the edge changes, \({n}_{h}\to {n}_{h}+1\). On the other hand, the relations among the parameters in Eq. (2): nearly equal repulsion energies \({U}_{e}\) and \({U}_{h}\), and a strong attraction constant \(u\) close to \(U\), combined with the choice of the non-vanishing tunneling terms, make this model very specific to the system we consider: concentric electron-hole edges encircling one antidot. In this case, the inner edge does not affect the conductance directly, but the number \({n}_{e}\) of electrons in it also changes periodically by 1 as a sequence of resonances.

To describe the antidot transport properties in the vicinity of one combined electron-hole resonance (where both the electron and hole antidot energy levels align with the chemical potential), we need to consider four charge states, each labeled by \({n}_{h}\) and \({n}_{e}\): \(\left|{n}_{h}{n}_{e}\right\rangle\). On the basis \(\left\{\left|00\right\rangle,\left|11\right\rangle,\left|01\right\rangle,|10\rangle \right\}\) of these four states, the Hamiltonian of the antidot is:

Here, \({\delta }_{h}\) is the gate-induced energy deviation of the outer edge state from the resonance point, \({\delta }_{e}\) is the same for the inner edge, \(\xi={\delta }_{h}-{\delta }_{e}-u\) is the energy of the electron-hole pair occupying the edge states. We include \(t\), \({t}^{+}\) terms to indicate how the states of the electron-hole system are coupled to the external charge reservoirs and produce the incoherent tunneling rates \(\Gamma\) illustrated in Fig. 4a. However, under the limit of weak antidot-reservoir coupling, we do not calculate these terms. Note that the electron-hole tunnel amplitude \(\Delta\) that couples \(\left|00\right\rangle\) and \(\left|11\right\rangle\) states has a somewhat unusual form of simultaneously creating or destroying two particles, an electron and a hole, which form an exciton. The reason for this is that it describes the coupling of the two different edge states, the electron and the hole-edge states. If one reformulates the description of both edges in terms of the same-charge particles, e.g., electrons, it becomes evident that the tunnel amplitude \(\Delta\) corresponds physically to the usual tunneling process of transfer of one electron between the two edge states. Such a transfer either adds an electron to the electron edge, leaving a hole in the hole edge, thus creating an exciton, or, in the reverse process, takes an electron from the electron edge, filling a hole in the hole edge, thus destroying an exciton in the process.

From the Hamiltonian, \({\delta }_{h}\) and \({\delta }_{e}\)-dependent ground states can be calculated as superpositions of the basis states. Tunneling through the antidot occurs when the system is tuned across two degenerate ground states with the same electron numbers but with hole numbers differing by one. This limits the conductance-contributing tunneling processes to \(\left|00\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left|10\right\rangle\) (empty electron edge mode) and \(\left|11\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left|01\right\rangle\) (filled electron edge mode). Without electron-hole coupling, the basis states are the eigenstates of the Coulomb energy, and their charge configurations in the ground state depend directly on the energies \({\delta }_{h},{\delta }_{e}\), as shown in Fig. 4b. \(\left|00\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left|10\right\rangle\) and \(\left|11\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left|01\right\rangle\) lead to the vertical traces of conductance peak along the corresponding phase boundaries in the (\({\delta }_{h}\),\({\delta }_{e}\)) plane. The horizontal shift between the two vertical parts of this boundary (which is also observed experimentally, e.g., in Fig. 3b) is the direct manifestation of electron-hole attraction within the exciton. This shift represents the additional magnitude of the gate voltage that is needed to overcome the Coulomb attraction energy \(u\) between the individual electron and hole in the two respective edge states of the antidot, after one extra electron was added to the internal edge of the antidot, when the gate voltages evolved past the resonance point.

Near electron-hole resonance, the tunnel amplitude \(\Delta\) mixes the states \(\left|00\right\rangle\) and \(\left|11\right\rangle\) along \(\xi=0\), forming a ground state which is the quantum superposition of the two states (see SI). Tunneling conductance peak emerges at energy determined by the condition of degeneracy between the resonance state and the adjacent ground states of \(\left|01\right\rangle\) and \(\left|10\right\rangle\) (see SI):

Here, the hyperbolic \(\left({\delta }_{e},{\delta }_{h}\right)\) relations (which, in the absence of electron-hole tunneling, correspond to the straight boundaries between the states \(|\)11〉 and \(|\)01〉 and between the states \(|\)10〉 and \(|\)00〉 in Fig. 4b) give rise to the anti-crossing feature in the conductance peak trace.

Near the resonance, the amplitude of the tunneling conductance from the \(\left|00\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left|10\right\rangle\) and the \(\left|11\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left|01\right\rangle\) processes is determined by the composition of the \(\left|00\right\rangle\) and \(\left|11\right\rangle\) states in the superposition, respectively. The tunneling probability \({p}_{0}\) for the \(\left|00\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left|10\right\rangle\) process rapidly decays as the superposition evolves into pure \(\left|11\right\rangle\) state under negative \(\xi\); and the tunneling probability \({p}_{1}\) for the \(\left|11\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left|01\right\rangle\) process rapidly decays as the superposition evolves into pure \(\left|00\right\rangle\) state under positive \(\xi\) (see SI):

Hence, deviation from the resonance condition drives the system out of the electron-hole superposition and results in the termination of the curvy anti-crossing feature.

Applying the model above to our experimental system, we simulate the doping dependence of the antidot tunneling conductance as shown in Fig. 4c. Here, we assume Lorentzian-shaped tunneling conductance peaks46 with an energy broadening of 0.2 meV to match the broadening of the measured conductance peaks. The energy (\({\delta }_{e}\), \({\delta }_{h}\)) dependences of the peak position and peak amplitude are calculated from Eqs.(4) and (5). The gate voltage-tuning of energy at ~0.5 meV/mV is obtained from the ratio between the top gate voltage period and the corresponding charging energy measured in Fig. 2a, b. Semi-quantitative agreement with the experimental observations (Fig. 3b, c) is achieved with an electron-hole Coulomb energy of \(u=0.8{{{\rm{meV}}}}\) and tunneling amplitude of \(\Delta=0.3{{{\rm{meV}}}}\), reproducing the anti-crossing-like gate-dependent peak position as well as the tunneling conductance peak amplitude. In Fig. 4c, the arrows highlight tunneling processes that give rise to conductance peaks, both far off-resonance (i and iv) and near resonance (ii and iii). The corresponding electron and hole energy level configurations of the tunneling states are depicted in Fig. 4e. In processes ii and iii, exciton states are the superposition of the \(\left|00\right\rangle\) and \(\left|11\right\rangle\) states.

For the Coulomb interaction between the electron and the hole QH antidot edges, we estimate \(u=\frac{{e}^{2}}{2\pi {\epsilon }_{{BN}}{\epsilon }_{0}L}{{{\mathrm{ln}}}}\left[{\left(1+\frac{{4{t}_{{BN}}}^{2}}{{{d}_{{eh}}}^{2}}\right)}^{1/2}+\frac{{2t}_{{BN}}}{{d}_{{eh}}}\right]\) (see SI). Here, \({d}_{{eh}}\) is the radial separation between the electron and hole edges, which should roughly be equal to \({d}_{{eh}}\simeq 35{{{\rm{nm}}}}\) to produce \(u=0.8{{{\rm{meV}}}},\) in agreement with the observations. A theoretical estimation of \({d}_{{eh}}\) requires detailed information on the \(\nu=0\) energy gap and the gate-dependent edge mode velocity, and is beyond the scope of this study. Our QH antidot exciton estimates, nevertheless, are consistent with the most natural model of concentric electron and hole-edge modes with similar diameters and significant tunneling between them. The order-of-magnitude of these estimates for \(u\) and \(\Delta\) are consistent with the assumed geometry of our exciton model with tunnel-coupled, roughly concentric electron and hole edges. Indeed, the inter-mode Coulomb attraction energy \(u\) is close to and slightly smaller than the on-site Coulomb energy measured from the charge stability diagrams, consistent with the fact that the effective distance between the edges is slightly larger than the characteristic distance between the charges on the same edge. At the same time, the tunnel coupling \(\Delta\) is significant, which implies closely spaced electron and hole edges. If an electron were localized on an atomic-scale impurity trap at such a small distance from the hole edge, it would produce more complex scattering of the hole instead of the observed coherent tunneling with amplitude \(\Delta\).

Reducing the inter-mode coupling \(\Delta\), the model suggests that the hyperbola part of the anti-crossing feature around the resonance is reduced (Fig. 4d). This is consistent with the observations at smaller filling factor \(\nu\), as shown in Fig. 3b (more discussion can be found in the SI). At small \(\nu\), the inner electron edge mode just starts to emerge near the center of the antidot and hence is physically distant from the outer hole-edge mode. As a result, the tunneling amplitude between the two modes is small, and the hyperbola feature in the gate dependence of the conductance peaks is largely reduced.

Similar to the conventional exciton, the localized QH exciton state is stabilized by reducing the ground state energy of an electron-hole pair. Compared to the non-interacting (\(u=0\)) and isolated (\(\Delta=0\)) electron-hole states, the excitonic state has its ground state energy lowered by finite interaction and finite inter-mode tunneling: \({E}_{g}\left(u,\Delta \right)-{E}_{g}\left({{\mathrm{0,0}}}\right) < 0\). This gate-dependent energy reduction can be considered as the equivalent of the exciton binding energy. In particular, for the neutrally biased electron-hole state (\({\delta }_{h}={\delta }_{e}\)), we have \({E}_{g}\left({{\mathrm{0,0}}}\right)-{E}_{g}\left(u,\Delta \right)=\frac{u}{2}+\sqrt{\frac{{u}^{2}}{4}+{\Delta }^{2}}\). Interestingly, and different from conventional excitons, the binding energy of the localized QH exciton is not only affected by the Coulomb energy but also by the tunneling amplitude between the electron and the hole modes. Finite inter-mode tunneling leads to a ground state energy reduction in comparison to the decoupled interacting electron-hole pair: \({E}_{g}\left(u,\Delta \right)-{E}_{g}\left(u,0\right)=\left|\frac{\xi }{2}\right|-\sqrt{\frac{{\xi }^{2}}{4}+{\Delta }^{2}}\), with maximum reduction of \(\Delta\) occurring at \(\xi=0\) (see Fig. 4f).

We note that a unique characteristic of the electron-hole system studied here is the combination of Coulomb repulsion on-site and Coulomb attraction between the two edges, which is different from the more familiar multi-quantum dot systems with Coulomb repulsion only. The electron-hole attraction \(u\) in the exciton breaks one continuous trace of the external hole-edge mode tunneling peak when the inner electron edge changes from being empty (\(\left|10\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left|00\right\rangle\)) to filled (\(\left|11\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left|01\right\rangle\)). Since the inter-edge Coulomb attraction effectively reduces the on-site Coulomb blockade, the shift of the off-resonance tunneling conductance peaks is toward a smaller magnitude of gate voltages with increasing number of electrons on the inner antidot edge. Classically, the two segments of the conductance peak would be connected and smoothly shifted by an energy of \(u\), reflecting the gradual increase of the average occupation of the electron state from 0 to 1 with the gate voltage. Quantum mechanically, on the other hand, strong tunneling couples the vacuum state \(\left|00\right\rangle\) and electron-hole pair state \(\left|11\right\rangle\), creating a coherent quantum superposition of the two states. Hole tunneling through the vacuum-pair superposition, as discussed through our model, leads to the anti-crossing-like gate voltage dependence of the conductance peaks with diminishing amplitude away from the electron-hole resonance.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a localization of individual quantum-coherent QH excitons in a graphene QH antidot. Compared to the conventional excitons on semiconductors, the QH exciton allows electrical tuning of the electron and hole states, and shows a ground state energy, which is determined both by Coulomb interaction and inter-mode tunneling. This work paves the way to a series of scientific tasks and technical developments. For example, excitonic states may be studied in more complex and versatile many-antidot systems for excitonic molecules. Time-dependent measurements may be performed on the excitonic state to explicitly study the quantum coherence. The QH antidot exciton scheme can potentially be extended to study the individual anyonic excitons in the FQH regime by tuning the bulk filling inside and outside the antidot to the fractional fillings of the zeroth Landau level. This implements a coupled state of the two fractional quasiparticles with opposite charges. The interaction energy of such fractional excitons, together with the tunnel coupling between the edge states of these quasiparticles, would be significantly smaller than in the integer regime, requiring much lower temperatures to observe the excitonic state. In the case of a single antidot, which can accommodate at most one exciton at a time, fractional exchange statistics may manifest itself indirectly, via the shape of the tunneling conductance peaks through the antidot. Beyond a single antidot, potential direct observation of the exchange statistics may be possible through exciton transport in the inter-coupled multi-antidot structures.

Methods

Sample fabrication

Graphite-hBN encapsulated graphene stack was assembled using standard van der Waals dry pickup technique, where top hBN, top graphite gate, middle hBN, monolayer graphene, bottom hBN, and bottom graphite gate are picked up sequentially following Fig. 1b with a polycarbonate (PC) stamp. All flakes were mechanically exfoliated onto precleaned (sonication in isopropanol followed by UV ozone cleaning for 2 min and 350 °C baking for 1 min) SiO2 substrates and were scanned using an atomic force microscope (AFM) to ensure contamination-free and atomically flat surfaces. The stamp base was a droplet-shaped polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) to take advantage of its natural curvature. The PC solution at 6% was then spin-coated onto the droplet-like PDMS base at 1000 rpm and left to dry on a hot plate at 100 °C for a total of 20 min.

The assembly process started with picking up the top hBN layer. The substrate carrying the hBN flake, preheated to 70 °C, was carefully raised until touching the lowest point of the PC stamp. The substrate was then further raised manually until the touch area expanded to the close vicinity of the destination hBN flake. The final contact was made using thermal expansion by heating the stage slowly to 110 °C at ~3 °C/min. The following separation process was done by cooling the stage/substrate back to 65 °C, at which the hBN flake got picked up from the substrate with the thermal contraction of the substrate stage as well as the PC stamp. The subsequent layers of graphite gates, hBN dielectric layers, and graphene were picked up in a similar manner. With all the layers designed in order and orientation on the PC stamp, the stack was then pressed onto a precleaned SiO2 substrate at 160 °C and heated up to 180 °C. Upon separation, the PC was detached from the PDMS stamp and transferred onto the SiO2 substrate together with the heterostructure stack. As the final step, we soaked the stack in chloroform for at least 10 h to dissolve PC. The stack was then transferred to isopropanol to remove chloroform before being blow-dried with nitrogen gas. The sample was then thermally annealed in forming gas (5% hydrogen in argon) at 400 °C for 2 h to thoroughly remove polymer residue on the top surface. The completed stack consisted of, from top to bottom, hBN (8 nm), top graphite(~2 nm), middle hBN(18 nm), monolayer graphene, bottom hBN (36 nm), and back graphite(~2 nm).

After assembly, the heterostack was scanned with an AFM for surface topography, and a bubble-free area was identified for the active area of the sample. The overall device outline was patterned into van der Pauw geometry with standard e-beam lithography and etched into shape with reactive ion etch (RIE) in CHF3/O2 plasma (40 sccm/4 sccm, 30 mTorr, 60 W). The four edge-contacts to the encapsulated graphene channel were made using the same etching method followed by thermal evaporation of 5 nm Cr and 50 nm Au. Similar edge-contact was fabricated on the top graphite gate. To prevent shorting top graphite to the graphene channel underneath the top gate lead at the edge of the channel, a crosslinked PMMA block was fabricated covering the exposed graphene edge, and the metal lead toward the top graphite gate contact was deposited over this block. In the final step, the two couplers and the antidot were etched out of the top graphite layer, together with four additional cuts made just outside the four side contacts to isolate the top graphite gate from the graphene channel. A scanning electron microscopy image of the device is shown in the SI.

Sample measurement

Transport measurement of the device was performed inside an Oxford VTI with a 12 Tesla superconducting magnet and He-III cryogenic insert with a base temperature of 300 mK. All electrical cables that enter the sample chamber go through low-pass pi-filters at room temperature and RC filters at 2 K, to minimize the high-frequency noise and the sample’s electron temperature. The high quality of the sample is confirmed by the quantum Hall (QH) plateaus, which start to form in very low magnetic fields (see S1).

All electrical measurements were carried out with the standard lock-in technique. Current excitation of 5–10 nA was provided by a Keithley 6221 current source at a frequency of 23 Hz. In the charge stability diagram measurements, the current course also provided a controllable DC bias. The AC component of the voltage response was measured by a Stanford Research SR830 lock-in amplifier, while the DC voltage bias was measured by a Keithley 2182A nanovoltmeter. The top graphite gate, bottom graphite gate, and Si gate voltages were provided by a Keithley 2450, a Keithley 2400, and a Keithley 6487, respectively.

Several segments of the patterned monolayer graphene acting as a contact to the channel are not covered by the graphite gates. When these segments are near charge neutral and under a strong magnetic field, large contact resistance can emerge and result in poor measurement results. To solve this problem, a Si back gate voltage was applied to electrostatically dope the segment with the same polarity as the graphene channel to avoid the highly resistive zero-filling gap at a p-n junction in a strong magnetic field.

Data availability

The data represented in Figs. 2–4 are available at the Figshare database: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29042864. All other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Any questions regarding the data can be addressed to the corresponding authors.

Code availability

The code underlying this study is available at at Figshare database: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29042864. Any questions regarding the code can be addressed to the corresponding authors.

References

Pashkin, Y. A. et al. Josephson charge qubits: a brief review. Quantum Inf. Process. 8, 55–80 (2009).

Bouchiat, V. et al. Quantum Coherence with a single cooper pair. Phys. Scr. T76, 165 (1998).

Nakamura, Y., Pashkin, Y. A. & Tsai, J. S. Coherent control of macroscopic quantum states in a single-Cooper-pair box. Nature 398, 786–788 (1999).

Averin, D. V., Zorin, A. B. & Likharev, K. K. Bloch oscillations in small Josephson junctions. Sov. Phys. JETP. 61, 407 (1985).

Büttiker, M. Zero-current persistent potential drop across small-capacitance Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. B 36, 3548–3555 (1987).

Averin, D. V. Quantum computing and quantum measurement with mesoscopic Josephson junctions. Fortschr. Phys. 48, 1055–1074 (2000).

Makhlin, Y., Schön, G. & Shnirman, A. Quantum-state engineering with Josephson-junction devices. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 357–400 (2001).

Manucharyan, V. E., Koch, J., Glazman, L. I. & Devoret, M. H. Fluxonium: single cooper-pair circuit free of charge offsets. Science 326, 113 (2009).

Kloeffel, C. & Loss, D. Prospects for spin-based quantum computing in quantum dots. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 4, 51–81 (2013).

Vandersypen, L. M. K. et al. Interfacing spin qubits in quantum dots and donors—hot, dense, and coherent. npj Quantum Inf. 3, 34 (2017).

Awschalom, D. D., Loss, D. & Samarth, N. Semiconductor Spintronics and Quantum Computation (Springer, 2002).

Petta, J. R. et al. Coherent manipulation of coupled electron spins in semiconductor quantum dots. Science 309, 2180 (2005).

Dutt, M. V. G. et al. Quantum register based on individual electronic and nuclear spin qubits in diamond. Science 316, 1312 (2007).

Maurer, P. C. et al. Room-temperature quantum bit memory exceeding one second. Science 336, 1283 (2012).

Friedman, J. R. et al. Quantum superposition of distinct macroscopic states. Nature 406, 43–46 (2000).

van der Wal, C. H. et al. Quantum superposition of macroscopic persistent-current states. Science 290, 773 (2000).

Chiorescu, I., Nakamura, Y., Harmans, C. J. P. M. & Mooij, J. E. Coherent quantum dynamics of a superconducting flux qubit. Science 299, 1869 (2003).

Martinis, J. M. Superconducting phase qubits. Quantum Inf. Process. 8, 81–103 (2009).

Clarke, J. & Wilhelm, F. K. Superconducting quantum bits. Nature 453, 1031–1042 (2008).

Devoret, M. H. & Schoelkopf, R. J. Superconducting circuits for quantum information: an outlook. Science 339, 1169 (2013).

Arute, F. et al. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 574, 505–510 (2019).

von Klitzing, K. et al. 40 years of the quantum Hall effect. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 397–401 (2020).

Stern, A. Anyons and the quantum Hall effect—a pedagogical review. Ann. Phys. 323, 204–249 (2008).

Saminadayar, L., Glattli, D. C., Jin, Y. & Etienne, B. Observation of the e/3 fractionally charged Laughlin quasiparticle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 2526–2529 (1997).

Dolev, M. et al. Observation of a quarter of an electron charge at the ν = 5/2 quantum Hall state. Nature 452, 829–834 (2008).

Kapfer, M. et al. A Josephson relation for fractionally charged anyons. Science 363, 846–849 (2019).

Eisenstein, J. P. Exciton condensation in bilayer quantum Hall systems. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 5, 159–181 (2014).

Li, J. I. A. et al. Excitonic superfluid phase in double bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 13, 751–755 (2017).

Li, Q. et al. Strongly coupled magneto-exciton condensates in large-angle twisted double bilayer graphene. Nat. Commun. 15, 5065 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Interlayer fractional quantum Hall effect in a coupled graphene double layer. Nat. Phys. 15, 893–897 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. Quantum Hall drag of exciton condensate in graphene. Nat. Phys. 13, 746–750 (2017).

Zhang, N. J. et al. Excitons in the fractional quantum Hall effect. Nature 637, 327–332 (2025).

Eisenstein, J. P. & MacDonald, A. H. Bose–Einstein condensation of excitons in bilayer electron systems. Nature 432, 691–694 (2004).

Yihang, Z. et al. Evidence for a superfluid-to-solid transition of bilayer excitons. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.16995 (2023).

Nakamura, J., Liang, S., Gardner, G. C. & Manfra, M. J. Direct observation of anyonic braiding statistics. Nat. Phys. 16, 931–936 (2020).

Willett, R. L., Pfeiffer, L. N. & West, K. W. Measurement of filling factor 5/2 quasiparticle interference with observation of charge e/4 and e/2 period oscillations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 8853–8858 (2009).

Willett, R. L. et al. Interference measurements of non-abelian $e/4$ & Abelian $e/2$ quasiparticle braiding. Phys. Rev. X 13, 011028 (2023).

Camino, F. E., Zhou, W. & Goldman, V. J. e/3 Laughlin quasiparticle primary-filling nu=1/3 interferometer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 076805 (2007).

Lin, P. V., Camino, F. E. & Goldman, V. J. Superperiods in interference of e/3 Laughlin quasiparticles encircling filling 2/5 fractional quantum Hall island. Phys. Rev. B 80, 235301 (2009).

Bartolomei, H. et al. Fractional statistics in anyon collisions. Science 368, 173–177 (2020).

Sim, H. S., Kataoka, M. & Ford, C. J. B. Electron interactions in an antidot in the integer quantum Hall regime. Phys. Rep. 456, 127–165 (2008).

Hata, T. et al. Tunable tunnel coupling in a double quantum antidot with cotunneling via localized state. Phys. Rev. B 108, 075432 (2023).

Mills, S. M. et al. Dirac fermion quantum Hall antidot in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 100, 245130 (2019).

Goldman, V. J. & Su, B. Resonant tunneling in the quantum Hall regime: measurement of fractional charge. Science 267, 1010–1012 (1995).

Röösli, M. P. et al. Fractional Coulomb blockade for quasi-particle tunneling between edge channels. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf5547 (2021).

Mills, S. M., Averin, D. V. & Du, X. Localizing fractional quasiparticles on graphene quantum Hall antidots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 227701 (2020).

Averin, D. V. & Nesteroff, J. A. Coulomb blockade of anyons in quantum antidots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 096801 (2007).

Maasilta, I. J. & Goldman, V. J. Tunneling through a Coherent “Quantum Antidot Molecule”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 1776–1779 (2000).

Kim, J., Benson, O., Kan, H. & Yamamoto, Y. A single-photon turnstile device. Nature 397, 500–503 (1999).

Benson, O., Kim, J., Kan, H. & Yamamoto, Y. Simultaneous Coulomb blockade for electrons and holes in p–n junctions: observation of Coulomb staircase and turnstile operation. Phys. E: Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 8, 5–12 (2000).

Michler, P. et al. A quantum dot single-photon turnstile device. Science 290, 2282–2285 (2000).

Senellart, P., Solomon, G. & White, A. High-performance semiconductor quantum-dot single-photon sources. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 1026–1039 (2017).

Albash, T. & Lidar, D. A. Adiabatic quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015002 (2018).

Déprez, C. et al. A tunable Fabry–Pérot quantum Hall interferometer in graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 555–562 (2021).

Ronen, Y. et al. Aharonov–Bohm effect in graphene-based Fabry–Pérot quantum Hall interferometers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 563–569 (2021).

Acknowledgements

X.D. and D.A. acknowledge support from NSF award under Grant No. DMR-2104781. K.W. and T.T. acknowledge support from the JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers 21H05233 and 23H02052), the CREST (JPMJCR24A5), JST, and World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI), MEXT, Japan. This research used the Electron Microscopy facility of the Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN), which is a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility, at Brookhaven National Laboratory, under Contract No. DESC0012704.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.P., N.M., F.C., and R.L. contributed to the sample fabrication. R.P. and X.D. carried out sample measurements. K.W. and T.T. synthesized the hBN crystals used in this experiment. X.D. designed the experiment. D.A. and X.D. performed modeling and data analysis. X.D., D.A., R.P., N.M., and F.C. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks U. Chandni, who co-reviewed with Suvronil Datta, Masaya Kataoka, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pu, R., Mizuno, N., Camino, F. et al. Localizing individual exciton on a quantum Hall antidot. Nat Commun 16, 10375 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65369-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65369-9