Abstract

The electroreduction of nitrate (NO3−) offers a promising pathway for carbon−free NH3 production and nitrogen cycle management. Pulsed NO3− electroreduction has demonstrated to enable the improvement of catalytic performance, but the underlying mechanisms remain little understood. Herein, we tune the Cu catalyst structure and steer the key N−containing intermediate adsorption configuration during pulsed NO3− electroreduction. By applying different positive and negative potentials, in situ dynamic restructuring of the Cu catalyst and the regulation of local microenvironment have been revealed. According to detailed in situ characterizations and theoretical calculations, periodic Cu oxidation occurs within specific potential ranges from −0.2 V to 0.2 V vs. saturated Ag/AgCl, facilitating the transition of *NO adsorption configuration and thereby enhancing NH3 formation. It can also increase NO2− coverage on Cu surface and inhibit side reactions. Conversely, the enhanced catalytic preformation in potential ranges from −1.2 V to −0.2 V was only attributed to the intrinsic characteristics of pulsed electrolysis. This study not only reveals the in−depth understanding of pulsed NO3− electrolysis, but also offers a general way of optimizing other electrocatalytic reactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitrate (NO3−) electroreduction into ammonia (NH3) via intermittent renewable electricity holds great promise for effluent treatment and ammonia production under mild conditions1,2,3. Most of the reported works have focused on designing novel catalysts to improve the NO3−-to-NH3 reaction performance through potentiostatic electrolysis. However, these catalysts would undergo complex synthesis procedures, the use of noble metal and deactivation issues unavoidably4,5,6,7,8, which drives researchers to develop alternative electrolysis techniques. Pulsed electrolysis method has emerged as a simple and responsive “knob” to affect product selectivity and electrode durability9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. For NO3− reduction, the alternate application of two different pulse potentials over a single-atom catalyst or an intermetallic compound enables the improvement of NH3 generation. The observations have been attributed only to some generalized factors, such as the in situ dynamic restructuring of the catalyst and the tuning of the local microenvironment. There is a strong need for understanding the underlying mechanisms and clarifying the essential reason for the enhanced catalytic performance.

NO3− electroreduction reaction involves two key steps: NO3− deoxygenation and nitrite hydrogenation. Currently, 3d transition metal-based catalysts, especially copper, have been intensively studied for NO3− reduction17,18. Cu has a favorable ability to bind NO3− and produce active *H, but it usually suffers from rapid deactivation due to the strong adsorption of N-bound intermediates, like *NO2 and *NO9,19,20,21. It is important to develop an appropriate strategy to regulate the structural properties of the Cu catalyst and thus alleviate the limitation above. Rational modulation of catalyst composition and structure through approaches such as doping22,23, alloying6,24, surface modification25,26, and hybrid loading13,27 has been shown to effectively optimize the electronic configuration and interfacial microenvironment. In addition to structural design, pulsed electrolysis provides a promising means to enhance catalytic performance. By tuning parameters such as potential amplitude, pulse duration, and step sequence, pulsed operation induces dynamic changes in the reaction environment, including local pH, mass transport, Cu restructuring, and oxidation state28. These factors break the balance between transient physicochemical processes at the electrode/electrolyte interfaces. More importantly, the variation extent can be controlled by changing the pulse duration and potential. Therefore, it is particularly crucial for NO3−-to-NH3 to establish the relationship between pulse parameter and catalytic performance.

The inherent sensitivity between the catalyst structure and reaction activity is directly reflected in the intermediate adsorption behavior. As such, regulating the formation and coordination of the intermediates (i.e., *H, N-bound and O-bound) is of great significance to optimize the NO3−-to-NH3 performance. For example, the imbalance between the generation and consumption of *H will lead to the poisoning of active sites or enhance the competing HER. Various materials design strategies, including heteroatom incorporation, heterogeneous structure construction, confinement approaches, alloying, and phase engineering, have been employed on Cu-based and other metal-based catalysts to tune the kinetics of H2O dissociation to generate *H, thereby facilitating localized *H enrichment and achieving a dynamic equilibrium between the generation and consumption of *H29,30,31,32. For example, applying a positive potential pulse periodically would modify the Cu surface, which contributes to the redistribution of electron cloud density, thereby facilitating the moderate adsorption and activation of *NO211. Moreover, the modified Cu site also results in different Cu–N and Cu–O affinities, which have a marked effect on the adsorption configurations of *NO (O-end, N-end, and NO-side), as well as the following reaction pathways. Consequently, revealing the correlation between the catalyst nature and intermediates adsorption configuration may fill the knowledge gap of pulsed NO3− electrolysis, and provide general guidance for other electrocatalytic reactions.

Herein, we used Cu nanoparticles as a model catalyst to investigate the dynamic behavior of catalyst structural changes and reaction intermediates during NO3− reduction under pulsed conditions (Fig. 1A). NH3 Faradaic efficiency (FE) and yield rate were significantly enhanced under different pulsed conditions compared to potentiostatic electrolysis. Notably, we achieved an NH3 FE of 94.1% with a corresponding yield rate of 2.3 mg h−1 cm−2. Both in situ experimental data and theoretical calculations provided compelling evidence that within the potential range where redox changes occurred (−0.2 V to 0.2 V), there was a transition from *NO Top to *NO Side-on, enhancing the coverage and conversion of NO2− and thereby promoting NH3 formation. Conversely, in the potential range where no discernible redox process occurred on the catalyst structure (−1.2 V to −0.2 V), only *NO Top was observed. The observed improvement in NO3− to NH3 performance was attributed to the inherent characteristics of pulsed electrolysis.

A Scheme of the potentiostatic potential electrolysis and pulsed electrolysis. EP represented a relatively positive potential, and EN represented a relatively negative potential. TP and TN represented the positive potential and negative potential pulse durations, respectively; B the FE and yield rate under the potentiostatic potential electrolysis over Cu nanoparticles in the electrolyte with 0.5 M K2SO4 and 0.01 M KNO3; NH3 FE and yield rate under the pulsed potential electrolysis conducted at C EP = 0.2 V for different TP, EN = −1.4 V for TN = 50 s and D EP = 0.2 V for TP = 2 s, EN = −1.4 V for different TN; E NH3 yield rate under potentiostatic potential electrolysis and the pulsed potential electrolysis conducted at different EP for TP = 2 s, EN = −1.4 V for TN = 50 s. Error bars denote standard deviations based on three independent measurements. The voltage is not iR corrected. Source data for the figure are provided as a Source data file.

Results

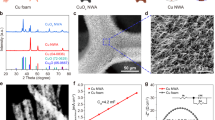

Cu nanoparticles with an average size of around 100 nm were synthesized and used as model catalysts (Fig. S1). The electrocatalytic performance for NO3−-to-NH3 conversion was assessed in a standard three-electrode H-cell under ambient conditions. 0.5 M K2SO4 aqueous solution containing 0.01 M KNO3 was used as electrolyte. Liquid product concentrations (NO3−, NO2−, and NH3) were quantified by UV-visible (UV-vis) absorbance spectra, and gaseous products were analyzed via gas chromatography33. Standard calibration curves for the corresponding measurements were provided in Figs. S2–S4. All electrode potentials were referenced to the reversible Ag/AgCl electrode14.

Two different electrolysis methods were carried out in our work, including potentiostatic potential electrolysis and pulsed electrolysis. During potentiostatic electrolysis, the FE of NH3 exhibited a characteristic volcanic shape. The maximum value was 57.2% at −1.4 V, corresponding to a yield rate of 0.7 mg h−1 cm−2 and a partial current density of 5.3 mA cm−2 (Figs. 1B, S5 and S6). The by-products were NO2− and H2 (Figs. S7 and S8). During pulsed electrolysis, a periodic potential sequence was applied, consisting of a brief pulse at a relatively positive potential (EP), followed by a reduction step at a more negative potential (EN), where the electroreduction reaction predominantly occurs (Figs. S9 and S10)28. At EP values ranging from –1.2 V to –0.4 V, the current generated upon applying EP is negative, whereas in the range of –0.2 V to 0.4 V, the current generated upon applying EP is positive. We identified −1.4 V as the optimal EN for screening the other pulsed electrolysis conditions. The positive potential and negative potential pulse durations (TP and TN) were optimized under the conditions of EP = 0.2 V, EN = −1.4 V, which showed that NH3 FE and yield rate reached their maximum values concurrently at TP = 2 s, TN = 50 s (Fig. 1C, D). We also tested the performance by adjusting EP at TP = 2 s, EN = −1.4 V, and TN = 50 s. Compared with the results of potentiostatic electrolysis, both NH3 FE and yield rate were increased when applying a pulsed potential of varying EP within the potential range of −1.2 V to 0.2 V. In particular, it could achieve the highest NH3 FE of 94.1% with a corresponding yield rate of 2.3 mg h−1 cm−2 (Figs. 1E, S11 and S12). However, further increase of EP resulted in the decline of NH3 FE. The NH₃ yield rate normalized by electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) revealed that pulsed electrolysis induced a 125% enhancement in intrinsic catalytic activity. Control experiments further showed that, at EP = 0.2 V, the maximum improvements in FE and yield rate were 12.0% and 65.6%, respectively, when only ECSA changes were present. In contrast, under pulsed electrolysis, where both ECSA enhancement and *NO intermediate reconfiguration occurred, the yield rate increased by up to 207.9%, with a corresponding 37.2% rise in FE. These findings clearly indicate that, although the increase in ECSA may contribute to the observed performance enhancement by inducing microenvironmental changes (e.g., promoting the local accumulation of NO₂−), it is not the primary factor responsible for the improved electrochemical performance. Instead, the modulation of adsorption behavior plays a more critical role in enhancing the catalytic activity (Figs. S13–S16). Furthermore, the energy consumption for producing 1 kg of NH3 and the corresponding energy efficiency over Cu nanoparticles under pulsed electrolysis were calculated to be approximately 16.9 kWh and 25.0%, respectively. Compared to the values obtained under potentiostatic electrolysis, both metrics exhibited substantial improvement, indicating that the pulsed electrolysis strategy offered a more energy-efficient pathway for NH3 synthesis (the energy consumption for producing 1 kg of NH3: 25.6 kWh and the corresponding energy efficiency: 15.1%) (Table S1)12.

After 20 cycles (60 h) at EP = 0.8 V under pulsed reduction mode, the decrease in NH3 FE was not obvious. In contrast, under potentiostatic reduction mode, NH3 FE showed a significant decline after just 3 cycles (9 h) (Fig. S17). Furthermore, ICP-OES analysis revealed no detectable copper in the electrolyte at EP = 0.2 V, suggesting that there was no copper loss. These findings imply that the pulsed reduction method significantly enhances the stability of the catalyst compared to the potentiostatic approach. We also applied the pulsed reduction method to other catalysts (commercial dendrite Cu, commercial Cu foam, and as-synthesized Cu2O nanocrystals). All of these catalysts exhibited varying degrees of electrochemical performance enhancement, indicating the general applicability of the pulsed electroreduction method for different catalysts (Figs. S18–S20).

It is important to reveal the catalyst structure–performance relationships under relevant reaction conditions. A series of material characterizations were performed to track the pulse-induced Cu catalyst structural reconstructions. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images showed that the morphology of the overall Cu catalyst almost remained unchanged when EP ≤ 0.2 V (Figs. 2A and S21). When a higher positive potential was applied, the catalyst would undergo significant structural collapse. After electrolysis at EP = 0.4 V, the content of Cu in the electrolyte was found to be 0.39 ppm through ICP-OES, while no Cu was detected in the electrolyte at EP ≤ 0.2 V. This finding aligned with the information presented by SEM and TEM images, illustrating significant disruption in the catalyst structure at higher EP.

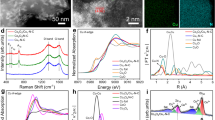

A TEM images, B HRTEM images, and C wavelet transform of Cu K-edge EXAFS spectra for the Cu nanoparticle under the condition at various EP; D in situ IR spectra under the potentiostatic and pulsed electrolysis; E the ratios of peak area of *NO Top to *NO Side-on; F the calculation of ratios between the area of the NO2− absorption band and the total area of absorption bands associated with both NO2− and *NH2OH production. All characterizations were applied after 1 h of electrolysis. Error bars denote standard deviations based on three independent measurements. The voltage is not iR corrected. Source data for the figure are provided as a Source data file.

To confirm the Cu species under pulsed electrolysis conditions, a series of characterizations were conducted after holding the potential at EP. The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images in Fig. 2B show that the lattice fringe spacing was 0.21 nm when EP was −0.4 V, indexed to the Cu(111) plane. As the EP was increased to −0.2 V, the Cu2O(111) facet (0.25 nm) was observed. Upon further increasing EP to 0.4 V, both CuO(111) (0.27 nm) and Cu2O(111) were noted, with Cu0 species being absent34. The structure changes of the catalysts have also been confirmed by the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns in Fig. S22. Quasi in situ Cu Auger L3M45M45 transitions were conducted to discern the valence state of the catalysts (Figs. S23 and S24). At EP = −0.4 V, exclusively metallic Cu0 was detected. Increasing EP to −0.2 V resulted in the emergence of Cu+ species, indicating the coexistence of Cu0 and Cu+. Further increasing EP to 0.2 V yielded a higher proportion of Cu+. The corresponding average copper oxidation state at 0.2 V was quantified between 0 and +1. At EP = 0.4 V, CuO became the dominant species, shifting the average oxidation state to the +1 to +2 range. These results demonstrate that the applied potential directly modulates the valence state distribution of the catalyst. According to X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy spectra and their linear combination fitting analysis35,36 (Figs. S25 and S26), at EP = –0.4 V, only metallic Cu0 was present. When EP increased to –0.2 V, Cu+ species began to appear, though in a minor fraction (only 14.6%). As EP was further increased to 0.2 V, the proportion of Cu+ rose significantly to 56.5%. At EP = 0.4 V, Cu2+ species emerged, accompanied by a corresponding decrease in the contents of Cu+ and Cu0. Additionally, the wavelet transform of Cu K-edge extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra depicted a decreasing trend in Cu–Cu coordination intensity and an increasing trend in Cu–O coordination intensity with increasing EP from −0.2 V to 0.2 V (Fig. 2C). When EP was 0.4 V, the absorption edge lay between those of standard Cu2O and CuO references, with the Cu–O coordination intensity post-wavelet transform exhibiting a further increase compared to that at EP = 0.2 V. To probe the structure changes of the catalysts under the potentiostatic reduction and the pulsed reduction process, in situ Raman was applied in the electrolyte containing 0.5 M K2SO4 and 0.01 M KNO3 (Fig. S27). Peaks at 446 cm−1 were assigned to Cu–OH37,38, and the peak at 614 cm−1 could be indexed to CuOx1,37,39,40. Under the potentiostatic reduction and the pulsed reduction processes, the peak of Cu–OH always existed. In contrast to the above results, the peak of CuOx appeared at the EP ≥ −0.2 V, and the peak intensity became stronger as EP was further increased. These results further demonstrated that EP played an essential role in changing Cu species.

We conducted quasi in situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), XRD, and in situ Raman to investigate species changes at EP = 0.2 V following varying reduction times (Figs. S28–S30). The quasi in situ XPS, XRD, and in situ Raman results revealed a decrease in the ratio of CuOx as the reduction time increased. However, during subsequent cycles, the catalysts exhibited consistent component compositions. This observation suggested that while the catalysts undergo dynamic copper surface reconstruction during the redox cycle, they maintained similar component characteristics across each cycle.

To elucidate the surface reconstruction behavior from Cu to CuOx, the ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulation was applied to focus on the oxidation process of four-layered Cu models, which involved the gradual introduction of oxygen. As shown in Fig. S31, we presented snapshots that depict both the initial configurations and the final arrangements after oxygen incorporation. Significantly, the results indicated that the Cu surface consistently undergoes reconstruction following the oxidation molecular dynamics (MD) cycles. Besides, we utilized H218O isotope labeling in the electrolyte to confirm the origin of oxygen species in the materials (Fig. S32)11. Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry revealed a significant incorporation of 18O, indicating that the oxygen species in CuOx were derived from hydroxides present in water. When the electrolyte was switched from H216O to H218O, the 18O/16O ratio increased from 0.003 to 1.4, demonstrating that the oxygen species from H2O participate in the evolution of the copper catalyst. The 18O/16O ratio for H216O was measured at 0.003, which aligns closely with the theoretical value of 0.002.

Our subsequent analysis aimed to establish the structure–activity relationship of catalysts under different electrolysis conditions. To resolve the mechanism of NH3 FE changes, we employed in situ Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometry to probe the dynamics of key reaction intermediates. Considering the catalyst structural collapse and the decrease in NH3 FE at EP ≥ 0.4 V, we excluded high EP potentials during subsequent discussions. In Fig. 2D, only the *NO Top peak at 1747 cm−1 was observed during the potentiostatic electrolysis and pulsed electrolysis at EP = −0.4 V, indicating linear adsorption of *NO over the active sites10. Upon increasing EP to −0.2 V, the appearance of *NO Side-on at 1571 cm−1 suggested the side adsorption configuration of *NO (Table S2)40,41,42. As EP increased to 0.2 V, the ratio of Area*NO Side-on/Area*NO Top increased to 0.52 (Fig. 2E). Meanwhile, the ratios between the area of NO2− absorption band and the total area of absorption bands associated with both NO2− and *NH2OH production were also calculated (Fig. 2F). For potentiostatic electrolysis, the ratio of AreaNO2−/(AreaNO2− + AreaNH2OH) was 60.5%, whereas it decreased to 55.6% under pulsed electrolysis at EP = −0.4 V. With the emergence of *NO Side-on at EP = −0.2 V, a significant decrease was observed (31.0%). At EP = 0.2 V, the ratio of AreaNO2−/(AreaNO2− + AreaNH2OH) further declined to 27.8%. These results indicated that the ratio of AreaNO2−/(AreaNO2− + AreaNH2OH) was strongly dependent on the adsorption configuration of *NO intermediate. A higher ratio of Area*NO Side-on/Area*NO Top corresponded to a faster rate of NO2− conversion. Similar enhancements in electrochemical performance were observed at lower NO₃⁻ concentrations, accompanied by distinct *NO intermediate configurations under different applied EP (Figs. S33 and S34).

Combined with the electrocatalytic performance and Cu species change, the appropriate applied EP potentials could be divided into two regions. The EP range from −0.2 V to 0.2 V was designated as Region 1, characterized by redox processes and the transition in *NO adsorption configuration from *NO Top to *NO Side-on. The EP range from −1.2 V to −0.2 V was identified as Region 2. No discernible redox process occurred on the catalyst, and only *NO Top was present. Importantly, the NO2− conversion rates in both regions were faster than those under potentiostatic electrolysis conditions.

In Region 1, the significant difference that accompanied the NH3 FE enhancement was the adjustment in *NO intermediate adsorption configuration. We further investigated the underlying causes of the *NO conformational change and its impact on the reaction pathway, thereby offering a more comprehensive understanding of the structure–performance relationship. To elucidate the EP-dependent *NOad, quasi in situ XPS was used to examine the surface composition of Cu catalysts at varying EP. The O 1s XPS spectra (Figs. 3A and S35) depicted peaks at 532.0 and 529.7 eV, representing the adsorbed OH or water on the oxygen neighboring vacancies and Cu–O–Cu bonding, respectively. It can be found that the integral-area ratios of these peaks escalated with prolonged cathodic potentials43,44,45. Additionally, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy was performed to study the generation of oxygen vacancies after the pulsed reduction and potentiostatic reduction. The catalysts after the pulsed reduction at EP = 0.2 V and EP = −0.2 V exhibited similar EPR signal (g = 2.002), which could be identified as the electrons trapped in oxygen vacancies (Fig. 3B)46,47,48,49. However, no signals were detected after the pulsed reduction at EP = −0.4 V and potentiostatic reduction. These results indicated the generation of oxygen vacancies after higher EP treatment, which experienced the redox process. Photoluminescence (PL) spectra (Fig. S36) affirmed oxygen vacancy (OV) concentration, with a peak at ~608 nm associated with the recombination of two-electron-trapped vacancies with photo-generated holes49,50. It exhibited maximal intensity at EP = 0.2 V, indicating the highest OV concentration.

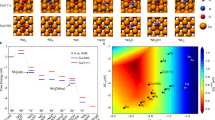

A XPS spectra of O 1s for catalysts during pulsed electrolysis at EP = 0.2 V. The measurement of the adsorbed OH or water on the vacancy sites was conducted after ~70 oxidation–reduction cycles; B EPR spectra of the catalysts after the pulsed reduction and potentiostatic reduction. C CV curves illustrating the OHad for Cu nanoparticles across various potentials during both the pulsed and potentiostatic electrolysis. D Fluorescence spectra displaying detected •OH radicals in 1 M KOH electrolyte using TPA (0.4 mM) as probe molecules. E The adsorption energy of *NO Side-on and *NO Top (ΔEads(*NO)) over the surface of both Ov-Cu2O(111)/Cu(111) and Cu(111); F the projected density of states (PDOS) of *NO on Ov-Cu2O(111)/Cu(111); G Gibbs free-energy diagrams of *NO-to-*NOH over Ov-Cu2O(111)/Cu(111) and Cu(111); H Schematic depicting the impact of pulsed strategy on changes in *NO configurations. The voltage is not iR corrected. Source data for the figure are provided as a Source data file.

The presence of OV in the catalysts can complement the oxophilicity of Cu, which in turn enhances the intrinsic activity of NO3−-to-NH3 conversion51. To study the surface oxygenophilic properties of the catalysts under different reduction processes, an electrochemical hydroxide ion (OHad) adsorption and desorption experiment was conducted52,53. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves (Fig. 3C) revealed Cu0-Cu+ redox peaks at approximately −0.37 and −0.67 V. Significantly, an OHad-associated peak was observed at around −0.59 V over the catalysts subjected to the pulsed process, whereas no significant signal was detected over the initial Cu nanoparticles54. This heightened OHad adsorption suggested stronger oxophilicity of the catalysts under the pulsed process compared to the initial catalysts. Additionally, fluorescence probe experiments were also carried out to assess differences in catalyst interaction with •OH radicals, indicating that the pulsed strategy significantly enhances oxygenophilic properties of the catalyst (Fig. 3D). Terephthalic acid (TPA) acted as a nonfluorescent probe, reacting with •OH radicals generated during the reaction to produce fluorescent 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid55,56,57,58. The fluorescence intensity of the catalysts under pulsed electrolysis surpassed that under potentiostatic electrolysis. It indicated that the Cu surface had higher oxophilicity under pulsed electrolysis, thereby facilitating the binding of oxygen-containing intermediates (*NO) and influencing the reaction pathway.

Subsequently, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were also performed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the *NO intermediates adsorption configuration over different Cu sites. Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) combined with ion etching was employed to investigate the distribution of oxygen after 1 h of pulsed reduction at EP = 0.2 V. As shown in Fig. S37, the oxygen content decreased with increasing etching depth, indicating that oxygen was predominantly present on the surface of the catalysts under the pulsed reduction process. By combining the AIMD results with the AES data, we adopted the catalyst model as heterostructures of Cu(111) and Cu2O(111) with oxygen vacancies to conduct DFT calculations (Fig. 3E and Supplementary Data 1). It revealed that both *NO Side-on and *NO Top configurations could be formed on Ov-Cu2O(111)/Cu(111), whereas the *NO Side-on configuration could not be stabilized on Cu(111). The projected density of states (PDOS) in Fig. 3F illustrates significant hybridization between the O atom of *NO and the Cu atom on Ov-Cu2O(111)/Cu(111), indicating the strong affinity of *NO for this surface, potentially facilitating the formation of *NO Side-on configuration. For Cu-based catalysts, the rate-determining step is typically regarded as the conversion from *NO to *NOH. Following the hydrogenation of *NO, the subsequent steps are usually characterized as thermodynamically spontaneous in the literature1,59,60. We subsequently calculated the Gibbs energy barrier (ΔG) for the *NO to *NOH transition to investigate the feasibility of *NO protonation across different configurations. It decreased from 0.17 eV over Cu(111) to −2.08 eV over OV-Cu2O(111)/Cu(111) (Fig. 3G), which could be attributed to the fact that the oxophilicity-controlled transition of *NO adsorption from Top to Side-on configuration enhanced the conversion of *NO into *NOH. Therefore, we can conclude that the redox process under pulsed conditions induced the emergence of OV, consequently modifying the oxygen affinity of the catalyst. It prompted the transition of *NO adsorption from Top to Side-on configuration, thereby enhancing NH3 formation (Fig. 3H).

Applying the pulsed electrolysis method in Region 1 not only affected the *NO adsorption configuration, but also regulated the microenvironment, such as elevating local pH and influencing H2O activation. To establish the connection between the structural changes of the catalyst and the competitive adsorption of H2O and NO2−, we continued the research from both theoretical and experimental perspectives. MD simulations were initially employed to model the concentrations of NO2− and H2O on the catalyst surface (Fig. 4A, B and Supplementary Data 1), indicating an increased concentration of NO2− and a decreased concentration of H2O on Cu2O(111) than that on Cu(111)10. Consequently, the alteration in catalyst components due to the brief pulse at positive potential could increase NO2− concentration and reduce H2O concentration.

The radical density of NO2− and H2O over the surface of A Cu2O(111) and B Cu(111) catalyst model. C The IR peak position shift under various potentials during both the pulsed electrolysis at EP = 0.8 V and the potentiostatic electrolysis. D H2 signals under the pulsed electrolysis at EP = 0.8 V and the potentiostatic electrolysis were detected by online DEMS. E The potentials required to attain a current density of −1 mA cm−2 and the reaction rate constants under varying EP conditions in the pulsed and potentiostatic electrolysis. The note (EP = 0.4 V, EP = 0.6 V, and EP = 0.8 V) stood for the Cu nanoparticles that experienced an hour pulsed reduction at EP = 0.4 V, EP = 0.6 V, and EP = 0.8 V, respectively. Error bars denote standard deviations based on three independent measurements. The voltage is not iR corrected. Source data for the figure are provided as a Source data file.

In situ FTIR spectroscopy was employed to examine the impact of different electrolysis strategies on *NO2 and *H intermediates coverage61. Figure S38 illustrates frequency variations of *NO2 stretching vibration at different applied potentials during potentiostatic and pulsed reduction processes. The peak within 1210–1250 cm−1 corresponds to the *NO2 band frequency. It showed linear changes with increasing potential, which could be attributed to the alterations in Fano line shape and Stark effect62. During pulsed electrolysis, *NO2 band shifted from 1236 cm−1 (−1.2 V) to 1226 cm−1 (−1.5 V). The Stark tuning rate for *NO2 adsorption was 33 cm−1/V (Fig. 4C), which was higher than that under potentiostatic electrolysis (11 cm−1/V). It indicated a stronger interfacial electric field under the pulsed electrolysis condition, which could improve NO2− coverage, catalyst conductivity, and suppress hydrogen evolution reaction (HER)8. Moreover, the peak frequency of the IR bond correlates with bond strength63. The observed red-shift of NO2− peaks under pulsed reduction mode suggested that NO2− was more readily activated.

To visually assess the effect of pulse conditions on inhibiting HER, online differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) was also used to monitor H2 signals. As illustrated in Figs. 4D and S39, H2 evolution was significantly restrained under pulse conditions at EP = 0.2 V compared to that under potentiostatic electrolysis. Bode plots were analyzed after different oxidation potential treatments to elucidate the mechanism underlying the suppression of H2 evolution by pulse conditions (Fig. S40)64. Notably, the peak intensities under pulsed electrolysis were obviously reduced compared to those under the potentiostatic process, and they also shifted to lower frequencies with increasing EP. It demonstrated that the pulsed process delayed the Heyrovsky step and suppressed H2 generation, facilitating *H capture by NO2−.

Previous studies have proposed that NO3− reduction involves a 2 + 6 electron transfer process21. A series of MD simulations and rotating disk electrode control experiments indicated that the pulsed strategy not only increased NO3− concentration near the electrode surface but also enhanced the kinetics of NO3−-to-NH3 (Figs. S41 and S42). To understand how pulsed electrolysis affected the kinetics performance of NO3−-to-NO2− and NO2−-to-NH3 conversion, we then investigated the potentials needed to achieve a current density of −1 mA cm−2 in 0.01 M NO3− or 0.01 M NO2− electrolytes under different electrolysis processes (Figs. S43 and S44)37,65. The results indicated similar potentials for NO3− and NO2− reduction during the potentiostatic reduction process, suggesting comparable catalytic activity in these two conversions (Fig. 4E). However, in the pulsed reduction process, NO3− reduction potentials increased by 386 mV, 402 mV, and 420 mV at EP = −0.2 V, 0 V, and 0.2 V, respectively, while NO2− reduction potentials experienced positive shifts of 552 mV, 582 mV, and 618 mV. These indicated the enhanced efficiency of both conversions during the pulsed reduction process. Further analysis was performed to calculate rate constants (k1) for NO3− conversion and (k2) for NO2− conversion. The k1 and k2 in the pulsed reduction process exhibited a similar trend, indicating stable conversion of NO3− and NO2−. Correspondingly, the k2/k1 ratios increased with increasing oxidation potential, demonstrating an enhancement in the NH3 formation efficiency compared to the potentiostatic process (Fig. S45). Overall, these findings suggested that pulsed electrolysis boosted NO3−/NO2− conversion.

Furthermore, we also investigated the mechanism of the enhanced NO3−-to-NH3 conversion via the pulsed method in Region 2. According to the DEMS results, the H2 signals during the pulsed process at EP = −0.6 V exhibited a decreasing trend compared to the potentiostatic process, indicating the inhibition of the competing HER (Fig. S46). Additionally, reaction kinetics were calculated to assess NO3− and NO2− conversion rates within the potential range of −1.2 V to −0.2 V at intervals of 0.2 V (Figs. S47 and S48). Compared to the NO3− and NO2− reduction potentials in the potentiostatic reduction process, NO3− reduction potentials increased by 18 mV, 53 mV, 72 mV, 110 mV, and 176 mV at EP = −1.2 V, −1.0 V, −0.8 V, −0.6 V, and −0.4 V, respectively, while NO2− reduction potentials experienced positive shifts of 30 mV, 120 mV, 217 mV, 374 mV, and 427 mV in Region 2 (Fig. S49). The k1 and k2 values in the potentiostatic reduction were 4.7 min−1 10−3 and 1.5 min−1 10−3, respectively. In contrast, the rate constants (k1 and k2) in the pulsed electrolysis increased with the increasing EP (k1: 5.8 min−1 10−3, 6.5 min−1 10−3, 8.8 min−1 10−3, 9.9 min−1 10−3, and 12.5 min−1 10−3, k2: 3.5 min−1 10−3, 4.9 min−1 10−3, 7.5 min−1 10−3, 8.9 min−1 10−3, and 11.8 min−1 10−3). The positive shifts of NO3− and NO2− reduction potentials and the increase in rate constants in Region 2 indicated that even without oxidation, the pulsed condition still promoted the conversion of NO3− and NO2−. These findings suggested that the inherent characteristics of pulsed electrolysis modulated the catalyst microenvironment, potentially preventing catalyst poisoning by N-containing intermediates and inhibiting side reactions15,66.

Discussion

In summary, this study has revealed the dynamics regulation of the Cu catalyst structure and key N-containing intermediate adsorption configuration during pulsed NO3− electroreduction and provided an in-depth understanding of the enhancement of NH3 formation. The composition and structure of the Cu catalyst underwent diverse periodic reconstruction by applying different alternating positive and negative potentials. When the EP was higher −0.2 V, the resulting Cu+/Cu0 surface induced the change of oxygen vacancy concentration. It could improve the surface oxophilicity and promote the transition from *NO Top to *NO Side-on, leading to reduce the *NO-to-*NOH energy barrier and enhance NH3 formation. Moreover, the modulated catalyst microenvironment could also increase NO2− coverage and inhibit side reactions. Differently, in the EP range from −1.2 V to −0.2 V, no discernible redox processes occurred on the catalyst, with only *NO Top being present. The pulsed strategy can improve both the inherent activity of the active sites and the FE significantly. The elucidated mechanism will contribute to a deeper understanding of pulsed NO3− electroreduction, facilitating the rational development of high-efficiency systems for NO3−-to-NH3 conversion. We believe that it could also inspire the design of novel, efficient catalytic systems for broad electrochemical reactions.

Methods

Chemicals

Toray Carbon Paper (CP, TGP-H-60, 19 × 19 cm), Nafion D-521 dispersion (5% w/w in water and 1-propanol, ≥0.92 meg/g exchange capacity), Copper sulfate pentahydrate, and Nafion N-117 membrane (0.180 mm thick, ≥0.90 meg/g exchange capacity) were supplied by Alfa Aesar China Co. Sodium hydroxide, potassium sulfate, potassium nitrate (≥99%), and sodium hypochlorite solution (≥5.2%) purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., P. R. China. Hydrazine hydrate and sodium nitroprusside dihydrate (≥99%) were obtained from J&K Scientific Ltd.

Synthesis of Cu NPs

The preparation of copper nanoparticles involved dissolving 3 g of stearic acid in 200 mL of 0.05 mol/L CuSO4 ethanol solution at 50 °C, forming a CuSO4-stearic acid mixture. Subsequently, a 1.5 mol/L KOH ethanol solution was rapidly added at 1.9 L/min under magnetic stirring at 1000 r/min, adjusting the pH to 12 to produce a Cu(OH)2 colloid. This colloid was then transferred to a three-neck flask, heated to 75 °C under an argon atmosphere, and reduced by the dropwise addition of 5 g hydrazine hydrate, with stirring continued for 300 min to yield a copper nanoparticle dispersion. The nanoparticles were isolated by centrifugation, washed with absolute ethanol and deionized water, and vacuum-dried.

Characterization

The SEM images were acquired using a JEOL SU8020 system, while TEM and HRTEM images were obtained with a JEOL JEM-2100F transmission electron microscope. XRD analysis was conducted using a Rigaku D/MAX2500 diffractometer equipped with a Cu-Kα source. XPS measurements were performed on a Thermo Scientific ESCA Lab 250Xi instrument, utilizing a 500 μm X-ray spot and 200 W monochromatic Al Kα radiation, with a base pressure of approximately 3 × 10−10 mbar in the analysis chamber. Energy referencing for all binding energies was based on the C 1s peak at 284.8 eV. UV-vis absorbance spectra were recorded using a Perkin Elmer Lambda 1050+ spectrophotometer. X-ray absorption spectroscopy measurements were conducted at the 4B9A beamline of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility, and the resulting data were analyzed using Athena and Artemis software. Photoluminescence spectra were acquired using a FluoroMax+ instrument.

Electrode preparation

A total of 5 mg of the synthesized catalyst was dispersed and sonicated in 0.5 mL of ethanol along with 10 µL of Nafion 521 dispersion solution to create a uniform catalyst ink. The surface area of the working electrode was 0.5 cm2, with a catalyst loading on the carbon paper of 0.14 mg cm−2.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical measurements were conducted using a CHI 660E electrochemical workstation (Shanghai CH Instruments Co., China) within an H-type electrolytic cell, wherein the cathode and anode chambers were separated by a Nafion 117 proton exchange membrane. The working electrode comprised the as-synthesized catalysts on carbon paper, while a saturated Ag/AgCl electrode and a platinum net served as the reference and counter electrodes, respectively. The working and reference electrodes were situated in the cathode chamber, while the counter electrode was positioned in the anode chamber. The surface area of the working electrode was 0.5 cm2. For nitrate reduction experiments, 37 mL of 0.5 M K2SO4 solution containing 0.01 M KNO3 was added to both the cathode and anode compartments. A pretreatment involving the application of an oxidation potential for 300 s was performed within the first cycle, after which the electrolyte was refreshed. All characterizations were applied after 1 h of electrolysis. Error bars denote standard deviations based on three independent measurements.

ECSA was estimated by CV measurements performed at scan rates of 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, and 120 mV s−1 within a potential window free of significant Faradaic processes. The capacitive current densities recorded at the selected potentials exhibited a linear dependence on the scan rate, and the slope of this relationship corresponded to the double-layer capacitance (Cdl). Since Cdl is directly proportional to the ECSA, the latter was derived accordingly.

Determination of ion concentration

Ammonia-N determination

A 4 mL sample from the electrochemical reaction vessel was mixed with 50 μL of solution A (0.75 M NaOH and NaClO), 500 μL of solution B (0.32 M NaOH and 0.4 M C7H6O3Na), and 50 μL of 1 wt% C5FeN6Na2O (solution C). After 2 h of standing, the sample concentration was measured indirectly using UV-vis spectroscopy, calibrated with standard NH4Cl solutions.

Nitrite-N determination

A color reagent was prepared by mixing 1 g p-amino benzenesulfonamide, 0.1 g N-(1-Naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride, 50 mL ultrapure water, and 2.94 mL phosphoric acid. Electrolyte samples were diluted to 3 mL and mixed with 1 mL of the color reagent. After 20 min at room temperature, UV-vis absorbance at 540 nm was recorded, and the concentration–absorbance curve was calibrated using KNO2 solutions.

Nitrate-N determination

Electrolyte portions were diluted to 4 mL, mixed with 1 mL of 0.1 M hydrochloric acid solution and 0.1 mL of sulfamic acid (98%) solution (0.8 wt.%). UV-Vis absorbance at 220 nm and 275 nm was measured, and the absorbance value (A) was determined by:

Calibration curves using standard KNO3 solutions were used to quantify NO3−.

Calculation of the Faradaic efficiency (FE) and yield rate.

Where:

F is the Faradaic constant with a value of 96,485 C mol−1,

cNH3 is the concentration of NH3,

V represents the volume of electrolyte in the cathode compartment (37 mL),

MNH3 is the molar mass of NH3,

Q stands for the total charge passing the electrode, and the total charge means the sum of Q under both EP and EN conditions. Q is obtained by integrating the instantaneous currents in raw i–t curves.

t is the electroreduction time (3 h),

S is the area of the catalyst on carbon paper (0.5 cm2).

Kinetic evaluation

Kinetic evaluation was conducted by recording linear sweep voltammograms of the catalysts in 0.5 M K2SO4 containing 0.01 M NO3− or 0.01 M NO2−. To determine the rate constants, electrolysis under the different reduction processes was performed for 3 h in a 37 mL electrolyte containing 0.01 M NO3− or 0.01 M NO2− in the cathode chamber. The reaction constants (k1 for NO3− reduction and k2 for NO2− reduction) were obtained by monitoring the concentrations as a function of electrolysis time. Concentration decay was assumed to follow the first-order rate equation

where C0 is the initial molar concentration of the reactant, and Ct is the molar concentration of the reactant at time t.

Calculation method

The MD simulations were conducted using the Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS), an open-source software platform. The simulation system was constructed using the PACKMOL package, which involved stacking a liquid phase onto either the bulk Cu or Cu2O surface. The NO2− species was represented using the PCFF force field. The Lennard–Jones potential force field combined with the Single Point Charge model for water was employed for all bonded and nonbonded interactions. Interaction parameters between different atom pairs were determined using the Lorentz–Berthelot mixing rules. The O–H bond distance and H–O–H angle in water were constrained to 1.0 Å and 109.47°, respectively, using the SHAKE algorithm in LAMMPS. Adsorption models were subjected to periodic boundary conditions with a cutoff radius set at 1 nm. Prior to MD simulation, the initial models were subjected to energy minimization using the steepest descent algorithm, followed by a 20 ns MD simulation. The NVT ensemble (T = 300 K) was employed during MD simulations, with temperature and pressure controlled using the Nose–Hoover thermostat and Parrinello–Rahman barostat, respectively. Density distributions of NO2− along with water molecules along the z-axis were calculated, and visualization and image rendering were performed using OVITO software.

AIMD (ab initio molecular dynamics) simulation

All calculations were carried out with the CP2K package (version 7.1) in the framework of the DFT67, based on the hybrid Gaussian and plan-wave scheme68. Molecular orbitals of the valence electrons were expanded into DZVP-MOLOPT-SR-GTH basis sets69, and the exchange-correlation between the electrons was treated by employing the Predew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional70 supplemented with Grimme’s D3 dispersion correction71. The interaction between the valence electrons and atomic cores was described by the norm-conserving Goedecker–Teter–Hutter (GTH) pseudopotentials72. A plane-wave density cutoff of 500 Ry was adopted. The initial structure was fully relaxed by CP2K with the BFGS scheme, and the force convergence criterion was set to 4.5 × 10−4 hartree/bhor. In the AIMD simulations, a constant electric field was applied to simulate the equivalent potential. The electric field was applied in the negative z-direction, and the strength was set to 0.0004 a.u., where 1 a.u. = 51.423 V/ Å. Given a box height of 41.2 Å, the corresponding potential was calculated to be 0.85 V.

The AIMD simulation was performed in the MD module of CP2K. The basis sets and potentials of the elements were set as the same type as previously mentioned. The time step was set to 2 fs, and the temperature was controlled by a Nose–Hoover thermostat73. After 20 ps of simulations, the RDF of Cu–Cu and Cu–O and the corresponding trajectory were analyzed and visualized by the VMD code74.

First-principles DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package75, employing the projector augmented wave method76. The exchange-correlation functional was treated using the generalized gradient approximation of the PBE functional77. The energy cutoff for the plane wave basis expansion was set to 450 eV, and the convergence criterion for geometry relaxation was set such that the force on each atom was less than 0.02 eV/Å. A vacuum of 15 Å was introduced along the z-direction to avoid interactions between periodic structures. The Brillouin zone integration was performed using a 3 × 3 × 1 k-point grid. Self-consistent calculations employed a convergence energy threshold of 10−5 eV. Van der Waals interactions were considered using the DFT-D3 method63. The Poisson–Boltzmann implicit solvation model, Vaspsol78, was used to investigate solvation effects, with the dielectric constant set to 80 to represent water. The free energies of the NO₃⁻ reduction reaction steps were calculated using the equation79:

where ΔEDFT is the DFT electronic energy difference for each step, ΔEZPE and ΔS are corrections for zero-point energy and entropy changes, respectively, obtained from vibrational analysis. T is the temperature (300 K). ΔGU is the free energy contribution related to the electrode potential U, and ΔGpH is the correction for the H⁺ free energy by the concentration, calculated as:

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper are available in the Source data file. Additional data available from the authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Wang, Y., Zhou, W., Jia, R., Yu, Y. & Zhang, B. Unveiling the activity origin of a copper-based electrocatalyst for selective nitrate reduction to ammonia. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 5350–5354 (2020).

Han, S. et al. Ultralow overpotential nitrate reduction to ammonia via a three-step relay mechanism. Nat. Catal. 6, 402–414 (2023).

Daiyan, R. et al. Nitrate reduction to ammonium: from CuO defect engineering to waste NOx-to-NH3 economic feasibility. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 3588–3598 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Structurally disordered RuO2 nanosheets with rich oxygen vacancies for enhanced nitrate electroreduction to ammonia. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202202604 (2022).

Liu, L., Zheng, S.-J., Chen, H., Cai, J. & Zang, S.-Q. Tandem nitrate-to-ammonia conversion on atomically precise silver nanocluster/MXene electrocatalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202316910 (2024).

Gao, W. et al. Alloying of Cu with Ru enabling the relay catalysis for reduction of nitrate to ammonia. Adv. Mater. 35, 2202952 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Graphdiyne enabled nitrogen vacancy formation in copper nitride for efficient ammonia synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 14898–14904 (2024).

Zhou, L. et al. Two-dimensional Cu plates with steady fluid fields for high-rate nitrate electroreduction to ammonia and efficient Zn-nitrate batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202401924 (2024).

Bu, Y. et al. Electrical pulse-driven periodic self-repair of Cu-Ni Tandem catalyst for efficient ammonia synthesis from nitrate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202217337 (2023).

Li, P. et al. Pulsed nitrate-to-ammonia electroreduction facilitated by tandem catalysis of nitrite intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 6471–6479 (2023).

Xu, L. et al. In situ periodic regeneration of catalyst during CO2 electroreduction to C2+ products. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202210375 (2022).

Huang, Y. et al. Pulsed electroreduction of low-concentration nitrate to ammonia. Nat. Commun. 14, 7368 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Efficient electrochemical nitrate reduction to ammonia with copper supported rhodium cluster and single-atom catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202202556 (2022).

Bai, L. et al. Electrocatalytic nitrate and nitrite reduction toward ammonia using Cu2O nanocubes: active species and reaction mechanisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 9665–9678 (2024).

Hu, Q. et al. Pulsed co-electrolysis of carbon dioxide and nitrate for sustainable urea synthesis. Nat. Sustain. 7, 442–451 (2024).

Qiu, W. et al. Overcoming electrostatic interaction via pulsed electroreduction for boosting the electrocatalytic urea synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202402684 (2024).

Cheng, X.-F. et al. Coordination symmetry breaking of single-atom catalysts for robust and efficient nitrate electroreduction to ammonia. Adv. Mater. 34, 2205767 (2022).

Luo, H. et al. Modulating the active hydrogen adsorption on Fe-N interface for boosted electrocatalytic nitrate reduction with ultra-long stability. Adv. Mater. 35, 2304695 (2023).

Wu, L. et al. Boosting electrocatalytic nitrate-to-ammonia via tuning of N-intermediate adsorption on a Zn-Cu catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202307952 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Efficient tandem electroreduction of nitrate into ammonia through coupling Cu single atoms with adjacent Co3O4. Nat. Commun. 15, 3619 (2024).

Chen, Z. W. et al. Unusual Sabatier principle on high entropy alloy catalysts for hydrogen evolution reactions. Nat. Commun. 15, 359 (2024).

Wang, P. et al. Photothermal-electrocatalysis interface for fuel-cell grade ammonia harvesting from the environment. Nat. Commun. 16, 5581 (2025).

Chen, F. et al. Efficient conversion of low-concentration nitrate sources into ammonia on a Ru-dispersed Cu nanowire electrocatalyst. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 759–767 (2022).

Gao, Q. et al. Synthesis of core/shell nanocrystals with ordered intermetallic single-atom alloy layers for nitrate electroreduction to ammonia. Nat. Synth. 2, 624–634 (2023).

Zhang, R. et al. Acidic nitrate electroreduction with ultrahigh energy efficiency. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202507724 (2025).

Su, X., Hong, F., Fang, Y., Wen, Y. & Shan, B. Molecular conjugated-polymer electrode enables rapid proton conduction for electrosynthesis of ammonia from nitrate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202422072 (2024).

Sui, X. et al. CO2/NOx- involved electrochemical C-N coupling reactions. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 40, 764–775 (2024).

Casebolt, R., Levine, K., Suntivich, J. & Hanrath, T. Pulse check: potential opportunities in pulsed electrochemical CO2 reduction. Joule 5, 1987–2026 (2021).

Yang, K. et al. Unveiling the reaction mechanism of nitrate reduction to ammonia over cobalt-based electrocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 12976–12983 (2024).

Liu, K. et al. Thermally enhanced relay electrocatalysis of nitrate-to-ammonia reduction over single-atom-alloy oxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 7779–7790 (2024).

Lou, Y. et al. Phase-dependent electrocatalytic nitrate reduction to ammonia on Janus Cu@Ni tandem catalyst. ACS Catal. 14, 5098–5108 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Modulating the surface concentration and lifetime of active hydrogen in Cu-based layered double hydroxides for electrocatalytic nitrate reduction to ammonia. ACS Catal. 14, 12042–12050 (2024).

Liu, Q. et al. Ambient ammonia synthesis via electrochemical reduction of nitrate enabled by NiCo2O4 nanowire array. Small 18, e2106961 (2022).

Xie, G. et al. Dual-metal sites drive tandem electrocatalytic CO2 to C2+ products. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202412568 (2024).

Timoshenko, J. et al. Steering the structure and selectivity of CO2 electroreduction catalysts by potential pulses. Nat. Catal. 5, 259–267 (2022).

Arán-Ais, R. M., Scholten, F., Kunze, S., Rizo, R. & Roldan Cuenya, B. The role of in situ generated morphological motifs and Cu(I) species in C2+ product selectivity during CO2 pulsed electroreduction. Nat. Energy 5, 317–325 (2020).

He, W. et al. Splicing the active phases of copper/cobalt-based catalysts achieves high-rate tandem electroreduction of nitrate to ammonia. Nat. Commun. 13, 1129 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Speciation of Cu surfaces during the electrochemical CO reduction reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 9735–9743 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Single-entity electrochemistry unveils dynamic transformation during tandem catalysis of Cu2O and Co3O4 for converting NO3 to NH3. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202214830 (2022).

Fang, J.-Y. et al. Ampere-level current density ammonia electrochemical synthesis using CuCo nanosheets simulating nitrite reductase bifunctional nature. Nat. Commun. 13, 7899 (2022).

Jia, S. et al. Nitrogenous intermediates in NOx-involved electrocatalytic reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202400033 (2024).

Figueiredo, M. C., Souza-Garcia, J., Climent, V. & Feliu, J. M. Nitrate reduction on Pt(111) surfaces modified by Bi adatoms. Electrochem. Commun. 11, 1760–1763 (2009).

Guo, W. et al. Highly efficient CO2 electroreduction to methanol through atomically dispersed Sn coupled with defective CuO catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 21979–21987 (2021).

Ou, G. et al. Tuning defects in oxides at room temperature by lithium reduction. Nat. Commun. 9, 1302 (2018).

Zhong, X. et al. Optimizing oxygen vacancies through grain boundary engineering to enhance electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2306673120 (2023).

Guo, Y. et al. Generation of holes from intra-valence band for enhanced oxidation potentials under visible light. Chem 10, 1252–1267 (2024).

Luo, L. et al. Synergy of Pd atoms and oxygen vacancies on In2O3 for methane conversion under visible light. Nat. Commun. 13, 2930 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. Oxygen vacancy associated single-electron transfer for photofixation of CO2 to long-chain chemicals. Nat. Commun. 10, 788 (2019).

Geng, Z. et al. Oxygen vacancies in ZnO Nanosheets Enhance CO2 electrochemical reduction to CO. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 6054–6059 (2018).

Jiang, S. et al. Tunable photoluminescence properties of well-aligned ZnO nanorod array by oxygen plasma post-treatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 289, 252–256 (2014).

Ham, K., Hong, S., Kang, S., Cho, K. & Lee, J. Extensive active-site formation in trirutile CoSb2O6 by oxygen vacancy for oxygen evolution reaction in anion exchange membrane water splitting. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 364–370 (2021).

Li, M. et al. Engineering surface oxophilicity of copper for electrochemical CO2 reduction to ethanol. Adv. Sci. 10, 2204579 (2023).

Choi, C. et al. Highly active and stable stepped Cu surface for enhanced electrochemical CO2 reduction to C2H4. Nat. Catal. 3, 804–812 (2020).

Zeng, L. et al. Cooperative Rh-O5/Ni(Fe) site for efficient biomass upgrading coupled with H2 production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 17577–17587 (2023).

Liu, F. et al. Concerted and selective electrooxidation of polyethylene-terephthalate-derived alcohol to glycolic acid at an industry-level current density over a Pd-Ni(OH)2 catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202300094 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Oxophilicity-controlled CO2 electroreduction to C2+ alcohols over lewis acid metal-doped Cuδ+ catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 21945–21954 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Switching CO2 electroreduction toward ethanol by delocalization state-tuned bond cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 14260–14266 (2024).

Xie, J., Ma, J., Zhao, S. & Waite, T. D. Flow anodic oxidation: towards high-efficiency removal of aqueous contaminants by adsorbed hydroxyl radicals at 1.5 V vs SHE. Water Res. 200, 117259 (2021).

Sun, S. et al. Spin-related Cu-Co pair to increase electrochemical ammonia generation on high-entropy oxides. Nat. Commun. 15, 260 (2024).

Zhou, B. et al. Cu1-Fe dual sites for superior neutral ammonia electrosynthesis from nitrate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202406046 (2024).

Malkani, A. S., Anibal, J. & Xu, B. Cation effect on interfacial CO2 concentration in the electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction. ACS Catal. 10, 14871–14876 (2020).

Ding, J. et al. Circumventing CO2 reduction scaling relations over the heteronuclear diatomic catalytic pair. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 11829–11836 (2023).

Chang, X. et al. Understanding the complementarities of surface-enhanced infrared and Raman spectroscopies in CO adsorption and electrochemical reduction. Nat. Commun. 13, 2656 (2022).

Liang, S., Teng, X., Xu, H., Chen, L. & Shi, J. H* species regulation by Mn-Co(OH)2 for efficient nitrate electro-reduction in neutral solution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202400206 (2024).

Wu, L. et al. Intermittent electrolysis enabling the enhanced efficiency and stability for nitrate reduction. Chem 102591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chempr.2025.102591 (2025).

Chen, W. et al. Pulse potential mediated selectivity for the electrocatalytic oxidation of glycerol to glyceric acid. Nat. Commun. 15, 2420 (2024).

Hutter, J., Iannuzzi, M., Schiffmann, F. & VandeVondele, J. cp2k: atomistic simulations of condensed matter systems. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 4, 15–25 (2014).

Lippert, G., Hutter, J. & Michele, P. A hybrid Gaussian and plane wave density functional scheme. Mol. Phys. 92, 477–488 (1997).

VandeVondele, J. & Hutter, J. Gaussian basis sets for accurate calculations on molecular systems in gas and condensed phases. J. Chem. Phys. 127, 114105 (2007).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Goedecker, S., Teter, M. & Hutter, J. Separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 54, 1703–1710 (1996).

Nosé, S. A unified formulation of the constant temperature molecular dynamics methods. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 511–519 (1984).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comp. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys. Rev. B 46, 6671–6687 (1992).

Mathew, K., Sundararaman, R., Letchworth-Weaver, K., Arias, T. A. & Hennig, R. G. Implicit solvation model for density-functional study of nanocrystal surfaces and reaction pathways. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 084106 (2014).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17886–17892 (2004).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (22293015 (B.X.H.), 22302006 (L.X.), 22121002 (X.F.S.), and 22203099 (J.Q.F.)), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (J210020 (X.F.S.)), National Funded Postdoctoral Researchers Program (GZB20230049 (L.X.)), Strategic Priority Research Program (A) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA0390402 (X.F.S.)), CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research (YSBR-050 (B.X.H.)), and Photon Science Center for Carbon Neutrality. The authors also thank the X-ray absorption spectroscopy facility support of the Beamline 4B9A at Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF) and the Spectroscopy Group of the Institute of Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.M.W., X.F.S., and B.X.H. proposed the project, designed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript; L.M.W. performed the whole experiment; S.H.J. and R.H.W. assisted in analyzing the experimental data; J.Q.F., L.B.Z., H.L.L., X.T., and R.J.F. conducted a part of the characterizations. X.C.K., Q.G.Z., and Q.L.Q. participated in discussions. L.X., X.F.S., and B.X.H. supervised the whole project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Mohammadreza Nazemi and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, L., Jia, S., Wang, R. et al. Steering the catalyst structure and intermediates adsorption configuration during pulsed nitrate electroreduction. Nat Commun 16, 10444 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65391-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65391-x