Abstract

Tetracoordinate boron compounds are widely used as dyes in medicinal research and material sciences. Current methods for accessing such compounds with a stereogenic boron center rely on chiral substrate-induced diastereoselective reactions or metal-catalyzed desymmetrization of pre-formed tetracoordinate boron molecules. Directly constructing a tetracoordinate B(sp3) center in a catalytic enantioselective manner remains challenging and underdeveloped, as controlled asymmetric reactions on a flat B(sp2) center are virtually unknown. Here, we address this challenge by leveraging the inherent structural features of commonly used boron compounds. In our approach, the amino-thiourea organocatalyst activates the phenol oxygen of the salicylaldehyde as an effective nucleophile for enantioselective addition to the B(sp²) center of a B,N-heterocyclic substrate. Subsequent iminium exchange involving the amine moiety of the B,N-heterocycle furnishes the tetracoordinate B(sp³) products with excellent optical purities. Our study adopted the B(sp²)-to-B(sp³) transformation strategy for the enantioselective synthesis of tetracoordinate boron molecules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

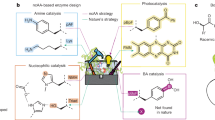

Boron is an inexpensive element with a significant presence in life and broad applications in chemistry, material sciences, and biomedical fields (Fig. 1a). For instance, the borophycin is a natural product isolated from the cyanobacterium Nostoc linckia that exhibits cytotoxicity against cancer cells1. Synthetic boron-containing molecules, such as bortezomib and lxazomib citrate, are FDA-approved human medicines for the treatment of cancers, infections, and multiple other diseases2,3. The boron dipyrromethene (BODIPY) and its derivatives are widely used fluorescent dyes in biological research4. Boron-containing molecules with chiral tetracoordinate boron centers also received considerable attentions for their applications in circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) materials5,6. Synthetic strategies for activating and modulating boron reactivity have now been developed to incorporate boron atoms into various molecules7,8,9,10. In contrast to the relatively well-developed reactivity modulation, constructing stereogenic (tetracoordinate) boron centers remains challenging. Current methods are based on chiral substrate-induced diastereoselective reactions11 or recently asymmetric catalysis (Fig. 1b)12,13,14,15,16,17,18. To date, fewer than ten asymmetric catalytic methods are reported, all relying on transition metal-catalyzed desymmetrization of compounds with pre-formed tetracoordinate boron centers (Fig. 1b, left). Our analysis of the widely used tetracoordinate boron compounds revealed that many of them either bear an iminium moiety (such as BOSPY4 and BASHY19) or a heteroaryl iminium analog (such as BODIPY18 (Fig. 1c). We therefore hypothesized that it may be feasible to develop a conceptually novel strategy by employing catalytic iminium formation as a handle to construct chiral boron centers. Given another observation that boron atom is often connected to heteroatoms in useful compounds such as BOSPY, we proposed a direct nucleophilic addition (of heteroatom) to B(sp2) center to construct a tetracoordinate B(sp3) stereogenic center (Fig. 1c). Our overall strategy constitutes a catalytic enantioselective nucleophilic addition of oxygen nucleophile to B(sp2) for direct construction of a chiral B(sp3) center (Fig. 1b, right). We expect our study to start a powerful catalytic strategy for direct and efficient construction of chiral tetracoordinate boron molecules with diverse structures and functions.

In this work, we show that under the catalysis of an organic catalyst containing a primary amine and a thiourea unit, reaction between salicylaldehyde 1a and BN phenanthrene 2a gave tetracoordinate boron compound 3a with an excellent optical purity (Fig. 1c). The formation of an iminium intermediate between catalyst and the salicylaldehyde substrate is a critical step to enable subsequent transformations and setup the boron chiral center (Fig. 1c, bottom left). The use of AgOAc co-catalyst could accelerate the iminium exchange process (swapping of the catalysts amine group with the boron substrate amine unit). The reaction yield and enantioselectivity could be significantly enhanced through adjusting the basicity of the catalytic system (Fig. 1c, bottom middle). The choices of solvent and bases are also crucial to achieve enantioselective process, because the background racemic reaction could occur under many different conditions (Fig. 1c, bottom right). The chiral boron products are afforded in good to excellent yields and optical purity. Preliminary studies revealed that these chiral boron compounds exhibit promising antibacterial activities against plant bacterial pathogens. These molecules also found interesting applications as synthetic precursors and as fluorescent materials.

Results

We commenced our investigation of the B(sp2) addition reaction using the salicylaldehyde 1a and the BN phenanthrene 2a as the substrates, with key results summarized in Table 1. The reaction is a facile process with a low energy barrier when polar solvent (such as CH3CN, EtOH, and DMF) was used without the assistance of any additional acid or base catalyst (Entry 1). Fortunately, we found that the reaction could hardly be processed in the solvent with lower polarity (Entry 2). Therefore, we continued to optimize the reaction condition using THF as the solvent, in which the racemic background reaction was minimized. Different chiral amine catalysts are evaluated for the dehydrative cycloaddition reaction (Entries 3 to 6). The chiral secondary amine catalyst A (known as Jørgensen-Hayashi catalyst)20,21 that has achieved great success in the asymmetric activation of aldehydes could promote our reaction, but only gave the target tetracoordinate B(sp3) product 3a in 17% yield (Entry 3). The (1S,2S)-cyclohexane-1,2-diamine catalyst B22 bearing a primary amino group could give the target product in a higher yield, but still with poor optical purity (Entry 4). The introduction of the thiourea group into the (1S,2S)-cyclohexane-1,2-diamine catalyst could help promote the product enantioselectivity, while the existence of a primary amino group in the catalyst structure proved crucial to achieve a promising yield (Entries 5 v.s. 6)23,24. Organic solvents with high polarity generally afford the products in racemic forms (e.g., Entry 7). Non-polar organic solvents generally favored the reaction enantioselectivities without much erosion on the product yields (e.g., Entry 8). Lewis acids have proven promising in the promotion of the enantioselectivities in organocatalytic reactions via non-covalent H-bonding or p-π interactions25,26, and activate the iminium intermediates formed between the amino catalysts and the reaction substrates. Therefore, various Lewis acids were evaluated as the co-catalyst in order to help accelerate the iminium transformation at the end of the current aminothiourea-catalyzed B(sp2) nucleophilic addition/iminium formation reaction (e.g., Entries 9 to 10). The addition of a catalytic amount of AgOAc showed encouraging effects in this transformation in enhancing both the reaction yield and enantioselectivity (Entry 10). Basic additives were found effective in promoting the reaction yields (e.g., Entries 11 to 13). The use of the strong basic additives could increase the yield of the target product 3a, but at the sacrifice of the enantioselectivity. Notably, the addition of a stoichiometric amount of the weak base of HCOONa led to the formation of the desired product 3a in a 60% yield with an excellent 96:4 er value (Entry 13). Meanwhile, we found that strong bases could promote the reaction in almost quantitative yields, but with detrimental effects on the enantioselectivity (e.g., Entry 12). It was believed that the strong bases could efficiently facilitate the multiple deprotonation steps throughout the reaction process, help accelerate the catalyst turnover, and thus promote the reaction process. We therefore examined the basicity of the reaction system, trying to figure out the optimal conditions for this enantioselective catalytic process. EDTA complexes have been widely used in buffer solvents in both organic synthesis and analytical chemistry. We therefore used the EDTA-4Na complex to adjust the basicity of the reaction system (Entries 14 to 15). Finally, the target product 3a could be afforded in a satisfactory 71% yield and 96:4 er value when switching the basic additive from HCOONa (Entry 13) to the mixture of EDTA-4Na / PTA (Entry 15).

Having identified the optimal reaction condition for the asymmetric B(sp2)-addition reaction between the salicylaldehyde 1a and the BN phenanthrene 2a, we then examined the reaction scope of the salicylaldehyde substrates 1 bearing different substituents (Fig. 2). An electron-withdrawing Cl group could be introduced onto the 5-position of the benzene ring of the salicylaldehyde, with the chiral tetracoordinate boron product 3b afforded in a higher yield and excellent enantioselectivity. Switching the Cl atom into an electron-neutral methyl group resulted in an increase on the reaction enantioselectivity, although with a sacrifice of the product yield (3c). Both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups could be installed on the 6-position of the benzene ring, with the corresponding products given in moderate yields and excellent er values (e.g., 3d and 3e). Introducing substituents onto the 4- and 3-positions of the benzene ring also led to the formation of the products in moderate yields and excellent enantioselectivities, regardless of their electronic properties (e.g., 3f to 3j). It is worth noting that the benzene ring of the salicylaldehyde could be switched into a naphthyl group, a fused heterocyclic group and a pyridyl group, with the target products afforded in moderate yields with excellent optical purities (3k to 3m). To our delight, challenging substituents such as the carboxyl group and the ester group could be introduced onto the salicylaldehyde substrate: the product 3n bearing a free carboxyl group was afforded in 50% yield with an excellent er value, while the product 3o bearing an ester group was afforded in 63% yield with a moderate optical purity. Salicylaldehyde bearing a 5-propionyl group could only give a trace amount of the desired product, which was difficult to isolate from the reaction system.

The substitution patterns on the BN phenanthrenes 2 were also explored to further clarify the advancements and limitations in the currently developed asymmetric B(sp2)-addition reaction (Fig. 2). For instance, introducing substituents onto the ring A and B of the substrate 2 generally gave the target products in moderate yields with good to excellent enantioselectivities (e.g., 4a to 4h). Switching the phenyl ring B into a dibenzo[b,d]thiophenyl ring or a furyl ring led to lower product yields and er values (4i and 4j). The reaction proved vulnerable to the 2-substituent on the benzene ring C of the B,N-heterocyclic substrate 2. Replacing the 2-CH3 group on the ring C with a H atom or a less steric 2-OCH3 group resulted in significant drops in the product optical purity (4k and 4l). In contrast, the 2-isopropyl group with bulkier steric hindrance on the ring C gave the product 4m in excellent enantioselectivity. Installing a Cl group on the 3-position of the ring C led to the formation of the product 4n in an almost quantitative yield, although the er value was only moderate under the current reaction condition. Similarly, switching the ring C from a phenyl group to a thiofuryl group resulted in dramatic improvement in the product yield, but with sacrifice on the enantioselectivity (4o). Although the ring C could also be replaced by a cyclohexyl group, a methyl group or an alkynyl group, the products could only be produced in moderate yields with poor to moderate optical purities under the current reaction condition (4p to 4r).

The BN phenanthrene substrates 2 could also be replaced with other types of B,N-heterocycles (Fig. 2). For instance, the BN naphthalene compound 5a could react with the salicylaldehyde 1a through a similar B(sp2) addition / dehydrative annulation reaction to give the chiral B(sp3) product 6a in a moderate yield and good optical purity. The NBN phenalene compound 5b was also effective in this asymmetric catalytic process, although the target product 6b could only be afforded in a poor yield and enantioselectivity under the current reaction conditions.

The absolute configuration of the product was elucidated via X-ray analysis on the single crystal of the chiral 3k afforded from this approach (Fig. 3a, left side). The tetrahedral character (THCDA) of the boron atom in 3k was calculated as 92.8% according to the Höpfl’s equation based on the 6 bond angles of the N–B–O, N–B–C1, N–B–C2, C1–B–C2, O–B–C1 and O–B–C2 bonds (Fig. 3a, right side)27. Meanwhile, the stereochemical stability of the tetracoordinate boron product 3a was evaluated through heating at 180 °C in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Fig. 3b). The racemization rate was recorded, and the energy barrier for racemization was experimentally determined as ∆G‡rac = 37.1 kcal/mol (see supplementary information for detailed experimental procedures)28.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to elucidate the mechanism for the enantioselective formation of the chiral zwitterionic product 3a via the dehydrative cycloaddition of salicylaldehyde 1a with boron substrate 2a, catalyzed by the chiral aminothiourea catalyst D. Figure 4 presents the Gibbs free energy profile for the studied mechanism.

The free energies were computed at SMD(diethylether)-M06-2X/def2-TZVP//M06-2X/(def2-TZVPPD for Ag and def2-SVP for all other atoms) level of theory. All values are given in kcal mol−1 with respect to the starting catalyst D, and all other substrates. TDI turnover frequency-determining intermediate, TDTS turnover frequency-determining transition state.

Our calculations suggest that the reaction starts with the condensation of the substrate 1a with the catalyst D to form the stable chiral imine intermediate I, with the release of one water molecule. This step is exergonic, with I lying at −3.8 kcal mol−1. Next, the interaction between I and the boron substrate 2a is endergonic, resulting in the formation of the complex II, lying at 12.9 kcal mol−1 above I.

We then examined the key enantio-inducing transition state (TS) structures by considering the nucleophilic attacks from either (Re)-face or (Si)-face at the stereogenic B(sp²) center by the OH group in the intermediate II. The calculated TS barriers suggest that the OH preferentially attacks the boron center from the (Re)-face via TS1_Re (overall barrier of 15.5 kcal mol−1 from I), which is 1.9 kcal mol−1 lower than the barrier from the (Si)-face via TS1_Si (overall barrier of 17.4 kcal mol−1 from I, see Fig. S7 for the DFT optimized structures). Therefore, after deprotonation of the OH group on the TS1_Re by the basic imine group, the phenoxide anion attacks the boron empty p-orbital from its (Re)-face and gives the adduct III as the key intermediate, which lies 12.2 kcal mol−1 above the intermediate I.

Subsequently, the intramolecular aminal formation reaction between the iminium ion moiety and the N(sp3) atom in III forms the stereoselective cyclic intermediate IV, lying at 3.4 kcal mol−1 above III. The calculated TS barriers indicate a preference for the N atom to attack the carbon center of iminium ion moiety in III from the (Re)-face via TS2 (barrier of 10.5 kcal mol−1 from III), rather than from the (Si)-face via TS2’ (barrier of 15.4 kcal mol−1) that leads to less stable isomer IV’ (for details, see Figure S8 in the supplementary information). It is worth noting that along the pathway originating from TS1_Si and leading to the minor product, the lowest-energy cyclization transition state TS2_minor lies 2.8 kcal mol−1 higher in free energy than TS2, which leads to the major enantio-selective product 3a, Fig. 4 (see Fig. S8 for the DFT optimized structures). Notably, this III → IV cyclization step via TS2 constitutes the overall enantio-determining and irreversible step, as the forward transformation from IV to 3a via TS3 proceeds with a lower barrier (5.5 kcal mol−1) than the reverse reaction from IV to III via TS2 (barrier of 7.1 kcal mol−1), further reinforcing the kinetic preference for the formation of enantio-selective product 3a, Fig. 4.

Next, intramolecular proton transfer within IV leads to the formation of the N,N-aminol intermediate V, lying at 3.4 kcal mol−1 above IV. The dissociation of the C–N bond via TS3 in V forms complex VI, where the re-generated catalyst D is bonded to the desired product 3a via N–H…π interaction. This step is exergonic, with VI lying 8.2 kcal mol−1 below IV. It is worth noting that the less stable stereoisomer IV’, formed from the less favorable TS2’, undergoes B–N bond cleavage in the subsequent C–N bond dissociation step and leads to a ring-opening process to curtail the formation of 3a (for details, see Figure S9 in the supplementary information). This is because that the intermediate IV could give the cyclic C = N bond in E stereochemistry with the H atom placed outside the ring system, whereas the intermediate IV’ would form the C = N bond in Z stereochemistry with the H atom placed inside the ring system, distorting the ring and causing B–N bond to break (Figure S9). Finally, from VI, the release of product 3a, along with the regeneration of the active catalyst D is facilitated by the co-catalyst AgOAc, which plays a key role in stabilizing the product 3a complex, Fig. 4. The AgOAc bound product 3a lies at 1.9 kcal/mol below the starting reactants D and 1a, thus, the overall transformation is thermodynamically favorable.

By examining the full Gibbs energy profile, it is evident that TS2 exhibits the highest barrier among all the steps in the catalytic cycle, making it the turnover frequency (TOF) determining transition state (TDTS), while complex I, being the most stable intermediate in the catalytic cycle, represents the TOF-determining intermediate (TDI). The catalytic cycle exhibits an overall energetic span (ΔG) of 22.7 kcal mol−1, which is consistent with the experimentally observed catalytic reactivity at 25 °C: the starting material of 2a could be recovered in 15% yield, and the intermediate I could be isolated in 11% yield after quenching the reaction after stirring for 48 h. Moreover, the computed free energy difference of 2.8 kcal mol−1 between the enantio-determining TS structures, TS2 vs TS2_minor, translates to an enantiomeric ratio of 99:1, which is in excellent agreement with the experimentally observed enantioselectivity of product 3a (96:4, Entry 15 of Table 1). TS2 is favored over TS2_minor potentially due to more favorable non-covalent interactions, such as π–π stacking and C–H…π interactions (Figure S10), along with more stabilizing interaction energy between the two fragments constituting the transition state (Table S6).

Finally, based on the computational and experimental results, a plausible reaction mechanism for the amino-thiourea bifunctional catalyst-promoted nucleophilic B(sp2) addition reaction is proposed, as depicted in Fig. 5. Initially, the salicylaldehyde substrate 1a is activated by the amine catalyst D to give the chiral imine intermediate I, which could be isolated and fully characterized (for details, see supplementary information on Page S16). The chiral intermediate I interacts with the compound 2a via H-bonding effects to give the complex II. In the complex II, the H-bonding interactions between the thiourea moiety of the catalyst D and the N(sp2) atom of the substrate 1 not only reduce the LUMO energy of the B(sp2)–N(sp2) bond, but also provide stereochemical orientation for the nucleophilic B(sp2) addition reaction. The imine N atom may deprotonate the acidic phenol proton, allowing the phenoxide to attack into the empty p-orbital of the boron center, giving the intermediate III. The adduct III could go through a rate-determining intramolecular aza-Mannich reaction between the iminium ion moiety and the N(sp3) atom to give the cyclic intermediate IV. A proton shift within IV gives the N,N-aminol intermediate V, which then breaks the C–N bond to yield the desired chiral product 3a and regenerate the amino-thiourea organic catalyst.

The optical properties of the afforded tetracoordinated boron compounds 3 and 4 were tested in both dichloromethane solutions and solid powder states (for details, see supplementary information on Pages S36 to S63). Different solutions of the compounds 3h and 3l were further examined, since they had given the highest quantum yields among all the tetracoordinated boron products 3 and 4 (Table 2). The absorption spectra of the compounds 3a, 3h and 3l were shown in Fig. 6a. The dichloromethane solution of 3a showed maximum absorptions at the wavelengths of 434 nm and 309 nm, with the extinction coefficients obtained as 10600 M−1 cm−1 and 22,600 M−1 cm−1, respectively. The dichloromethane solution of 3h showed similar maximum absorption peaks to 3a, but with dramatically distinct extinction coefficients: the extinction coefficient at 430 nm was 24500 M-1 cm−1, and the extinction coefficient at the UV region was only 4000 M−1 cm−1. In contrast, the compound 3l showed obvious bathochromic shifts on the absorption peak compared to 3a and 3h, and gave a maximum absorption peak at 455 nm with an extinction coefficient of 26,700 M−1 cm−1. The time-dependent DFT calculations demonstrate that the absorption maxima of 3a at 434 nm obtained in the experiment correspond to the S0 to S1 energy state, which originates from the HOMO to LUMO transition with the maximum extinction coefficient (for details, see Table S12 in the supplementary information).

Absorption (a) and emission (b) of selective compounds in dichloromethane; Absorption (c) and emission (d) spectra changes of 3h in acetonitrile and water mixture solutions (4 × 10−5 M); The CD (e) and CPL (f) spectra of the (R)-3a and (S)-3a in dichloromethane. Emissions were obtained with excitation at 450 nm.

Upon excitation, most of the tetracoordinated boron compounds we tested exhibited broad emission peaks in the range of 500–600 nm, showing green to orange colored fluorescence (Fig. 6b). It is worth mentioning that all the tetrahedral boron (III) compounds obtained from the current protocol possessed large Stokes shifts ranging from 2610 cm−1 (4q) to 8650 cm−1 (4j), which are much larger than those of the reported BOSPYs (~2000 cm−1) and BODIPYs (~500 cm−1)3,4,5. These large Stokes shifts could help reduce the interference from the exciter and improve the resolution of the image. The compounds 3a, 3h, and 3l in the solutions of THF and acetonitrile exhibited similar absorption and fluorescence properties to those in the solution of dichloromethane. However, the fluorescence emission spectra of 3h and 3l showed obvious bathochromic shifts (31 nm to 86 nm) in their solid forms, with their quantum yields significantly increased to 49.2% and 56.3%, respectively.

The good solid-state emission of these compounds indicates possible emission enhancement in the aggregate state due to the restricted vibration and rotation in aggregates10,11. Indeed, the tetrahedral boron (III) compounds we obtained showed satisfactory aggregation-induced emission (AIE) activities (Fig. 6c, d). For instance, the compound 3h showed weak emission in the acetonitrile solution. However, the emission intensity of the 3h solution could be enhanced when the aggregation was caused by adding the poor solvent of water. Especially, the emission intensity could be significantly enhanced 4.46 fold when the water fraction was increased from 60% to 99%. Meanwhile, the emission peak was bathochromic shifted by 34 nm when the water fraction was varied from 0% to 99%, causing the color of the solution changed from light green to bright yellow.

The chiroptical properties of the representative chiral-at-boron enantiomers were studied via circular dichroism (CD) and CPL spectroscopies (Fig. 6e, f, and Figures S17–22). The CD and CPL spectra of the (R)-3a and (S)-3a in dichloromethane exhibit clear mirror images with distinct Cotton effects (Fig. 6e, f). Their luminescence dissymmetry factors (glum) were measured as +5.3 × 10−4 and −6.0 × 10−4, respectively. Similarly, enantiomer 3k and 4i also display mirror-image CPL spectra in the 550–650 nm range, with closely matched glum values (Figures S21, 22). These glum values align with those of recently reported chiral tetracoordinate boron compounds exhibiting CPL activity12,16.

Intersystem crossing (ISC) process from singlet excited state to triplet excited state is another possible competitive pathway for the relatively weak emission of these compounds obtained in organic solvent. We therefore studied the reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation ability of these compounds using 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF) as a ROS sensor, which decreases in absorbance upon reaction with ROS. Notably, all these measured compounds 3 showed efficient ROS generation ability (for details, see supplementary information on Pages S51 to S57) and the ROS quantum yields (Table S11) are in the range of 0.36-0.90. Interestingly, the solution of 3a in the presence of TEMP (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine, a selective spin-trap agent for 1O2) under light irradiation produced no signal in the EPR spectra (Figures S26), but significant EPR signals could be observed upon irradiation of the solution 3a and DMPO (dimethylpyrrolo-1,3-dione N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnitrone, a selective spin-trap agent for O2•–), indicating the generation of O2•– radical (Type I ROS). In order to rationalize the efficient ROS generation properties, the relative energy level (ΔEST) and the spin-orbit coupling (SOC) of representative 3a and 3j were calculated (Table S14). Both compounds exhibited small energetic gaps between T3 and S1, with ΔEST values of 0.003 eV for 3a (degenerate S1 and T3) and 0.09 eV for 3j, coupled with correspondingly large SOC values of 1.38 and 1.54 cm−1, respectively (for details, see Table S14 in the supplementary information). This indicates that S1 → T3 is the most important triplet deactivation channel for our chiral-at-boron compounds. These results suggest that these chiral-at-boron compounds are a promising class of heavy-atom-free Type I photosensitizers29.

The organocatalytic asymmetric B(sp2)-addition reaction can be carried out in gram scales without erosion on the product enantioselectivities, and the chiral tetracoordinate boron products have found interesting applications in organic synthesis (Fig. 7a). For instance, the chiral product 3a could be obtained in 60% yield (0.89 g) and 96:4 er value from 1.08 g of 2a through this protocol. The enantio-enriched compound 3a could react with Grignard reagents to give the chiral adducts 7 or 8 bearing simultaneously a stereogenic boron, a stereogenic nitrogen, and a stereogenic carbon center in good yields as single diastereomers without obvious erosion of their optical purities. The chlorinated product 3b could be obtained from the gram-scale reaction between 1b and 2a in 65% yield (1.15 g) and 95:5 er value (Fig. 7b). The chiral compound 3b could go through a Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction with the phenylboronic acid to give the phenyl-substituted product 9 in a good yield with a slight decrease in the optical purity. Moreover, the optically active tetracoordinate boron compounds could be introduced into various bioactive molecules (Fig. 7c). For example, the chiral compound 3n bearing a carboxylic acid group could be condensed with the hydroxyl group on the natural product Geraniol (10) and provide the product 11 in a good yield with excellent optical purity. Geraniol has been used as an antibacterial and insect repellent drug30. Phytol (12) is a natural product that has been isolated from green leaves and possesses antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-schistosomiasis, and anti-bacterial activities31. It can also be connected onto the chiral tetracoordinate boron compound 3n through simple protocols and furnishes the optically pure product 13 in a good yield as a single diastereomer. Since the compound 3n and its ester derivative have shown excellent photophysical properties with large Stokes shifts (Tables 2, 3n, and 3o), the efficient coupling of 3n to bioactive molecules would be useful in pharmacokinetics studies to visualize the drug migrations in living cells.

We have long been committed to the development of novel pesticide structures for plant protection32. To the best of our knowledge, there was no report on the application of chiral organoboron compounds in the field of pesticide development33. We are therefore very interested in the bioactivities of these chiral organoboron compounds as anti-bacterial reagents. Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo)34 and Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri (Xac)35 are two common plant bacterial pathogens that have caused significant global economic loss every year. Xoo mainly infects the leaf part of rice, which could decrease the panicle formation rate and cause death of rice. Xac could infect citrus and cause leaf drop, fruit drop, and even the death of the entire citrus tree. We systematically examined the anti-bacterial activities of the racemic mixtures and different enantiomers of the compounds 3 and 4 against Xoo and Xac (Table 3). It was interesting to find that the configurations of the stereogenic boron centers played significant roles in their anti-bacterial activities (see supplementary information for detailed biactive evaluation data). For example, the (S)-3k, (R)-4i and (R)-4j have shown about 3 times better activities than their enantiomers or their racemates in the inhibition activities against Xoo, some of which were even better than the commercial drugs of thiodiazole copper (TC) and bismerthiazol (BT). Moreover, the (S)-3b, (S)-4d and (S)-4j were 2 to 4 times more active than their (R)-enantiomers or their racemates in the anti-bacterial activities against Xac, which were all better than the efficiencies of the commercial drugs of TC and BT. Therefore, it would be interesting to pursue an in-depth investigation into the functions of stereogenic boron centers on their substrate-target interactions.

Discussion

In summary, we have disclosed an organocatalytic approach for the asymmetric construction of tetracoordinate boron compounds. A direct asymmetric addition onto the planar tricoordinate boron substrates was realized with the catalysis of a structurally simple amino-thiourea organic catalyst. The chiral-at-boron products were generally afforded in moderate to excellent yields and enantioselectivities through a dehydrative cycloaddition process. In addition, the enantio-enriched tetracoordinate organoboron compounds are valuable in synthetic transformations and can give multi-functional chiral compounds in good to excellent yields and optical purities via simple operations. The tetracoordinate organoboron compounds also showed interesting photophysical and anti-bacterial properties that were potent in the development of optoelectronical materials and pesticides. The full catalytic cycle and the mechanism underlying enantioinduction were elucidated using computational studies. Further investigation on the asymmetric B-addition reactions for chiral-at-boron compound synthesis and studies on the bioactivities of the stereogenic tetracoordinate boron molecules for plant protection are in progress in our laboratories.

Methods

General

The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were acquired over Bruker Avance 400 spectrometers. High resolution mass spectrometer analysis (HRMS) was performed on Thermo Fisher Q Exactive mass spectrometer. Shimadzu Prominence LC-20A (Shimadzu, Japan), and Waters Acquity HPLC PDA (Photodiode Array) detector. The UV-Vis absorption spectra were acquired using a Shimadzu UV-2450 spectrophotometer, and the fluorescence spectra were acquired with a Edinburgh FS5 spectrometers. Absolute fluorescence quantum yields were determined using a Hamamatsu Quantaurus spectrofluorometer equipped with an integrating sphere. Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were measured on a BioLogic MOS 500 CD Spectrometer. Circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) measurements were performed on an OLIS CPL SOLO spectrometer. The X-ray crystal diffraction data were collected using a Bruker APEX-II CCD diffractometer. The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were processed using MestReNova. The spectral data were processed using Origin 2024b.

General procedure for the synthesis of the chiral B(sp3) compounds

To a 4 mL reaction flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar, was added chiral thiourea D (0.03 mmol), 1 (0.3 mmol), 2 (0.1 mmol), AgOAc (0.05 mmol), EDTA-4Na (0.15 mmol), PTA (0.12 mmol), 4 Å MS (150 mg). Et2O (1 mL) was added via syringe. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 48 h at 25 °C. After completion of the reaction (monitored by TLC), the mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting crude residue was purified via column chromatography on silica gel to afford the desired products 3 and 4.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

X-ray crystallographic data for compounds 3k, 7 and 8 were available free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre under CCDC 2351572, 2352637, and 2352635. Full experimental details for the preparation of all new compounds, and their spectroscopic and chromatographic data, can be found in the supplementary materials. Geometries of all DFT-optimized structures have been deposited and uploaded to https://zenodo.org/records/17047909 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17047909). Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are also available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Hemscheidt, T. et al. Structure and Biosynthesis of Borophycin, a New Boeseken Complex of Boric Acid from a Marine Strain of the Blue-Green Alga Nostoc Linckia. J. Org. Chem. 59, 3467–3471 (1994).

Kane, R. C., Bross, P. F., Farrell, A. T. & Pazdur, R. Velcade: US FDA Approval for the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma Progressing on Prior Therapy. Oncologist 8, 508–513 (2003).

Husák, M. et al. Determining the Crystal Structures of Peptide Analogs of Boronic Acid in the Absence of Single Crystals: Intricate Motifs of Ixazomib Citrate Revealed by XRPD Guided by Ss-NMR. Cryst. Growth Des. 18, 3616–3625 (2018).

Liu, K. et al. Electrochemical C-H thiocyanation of BODIPYs: Two birds with one stone of KSCN. Green Synth. Catal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gresc.2024.10.005.

Bruhn, T. et al. Axially Chiral BODIPY DYEmers: An Apparent Exception to the Exciton Chirality Rule. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 14592–14595 (2014).

Lu, H., Mack, J., Nyokong, T., Kobayashi, N. & Shen, Z. Optically Active BODIPYs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 138, 1–15 (2016).

Neeve, E. C., Geier, S. J., Mkhalid, I. A. I., Westcott, S. A. & Marder, T. B. Diboron(4) Compounds: from Structural Curiosity to Synthetic Workhorse. Chem. Rev. 116, 9091–9161 (2016).

Légaré, M.-A., Pranckevicius, C. & Braunschweig, H. Metallomimetic Chemistry of Boron. Chem. Rev. 119, 8231–8261 (2019).

Wang, M. & Shi, Z. Methodologies and Strategies for Selective Borylation of C−Het and C−C Bonds. Chem. Rev. 120, 7348–7398 (2020).

Yang, K. & Song, Q. Tetracoordinate Boron Intermediates Enable Unconventional Transformations. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 2298–2312 (2021).

Abdou-Mohamed, A. et al. Stereoselective Formation of Boron-stereogenic Organoboron Derivatives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 4381–4391 (2023).

Zu, B., Guo, Y. & He, C. Catalytic Enantioselective Construction of Chiroptical Boron Stereogenic Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 16302–16310 (2021).

Zhang, G. et al. Construction of Boron-Stereogenic Compounds via Enantioselective Cu-Catalyzed Desymmetric B-H Bond Insertion Reaction. Nat. Commun. 13, 2624–2634 (2022).

Zhang, G. et al. Cu(I)-Catalyzed Highly Diastereo- and Enantioselective Constructions of Boron/Carbon Vicinal Stereogenic Centers via Insertion Reaction. ACS Catal. 13, 9502–9508 (2023).

Zu, B., Guo, Y., Ren, L.-Q., Li, Y. & He, C. Catalytic Enantioselective Synthesis of Boron-Stereogenic BODIPYs. Nat. Synth. 2, 564–571 (2023).

Ren, L.-Q. et al. Modular Enantioselective Assembly of Multi-Substituted Boron-Stereogenic BODIPYs. Nat. Chem. 17, 83–91 (2025).

Ankudinov, N. M. et al. Synthesis of Chiral Boranes via Asymmetric Insertion of Carbenes into B–H Bonds Catalyzed by the Rhodium(I) Diene Complex. Chem. Commun. 60, 8601–8604 (2024).

Gao, Y. et al. Catalytic Enantioselective Synthesis of Boron-Stereogenic and Axially Chiral BODIPYs via Rhodium(II)-Catalyzed C−H (Hetero) Arylation with Diazonaphthoquinones and Diazoindenines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202418888 (2025).

Santos, F. M. F. et al. A Three-Component Assembly Promoted by Boronic Acids Delivers a Modular Fluorophore Platform (BASHY Dyes). Chem. Eur. J. 22, 1631–1637 (2016).

Marigo, M., Wabnitz, T. C., Fielenbach, D. & Jørgensen, K. A. Enantioselective Organocatalyzed α Sulfenylation of Aldehydes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 794–797 (2005).

Hayashi, Y., Gotoh, H., Hayashi, T. & Shoji, M. Diphenylprolinol Silyl Ethers as Efficient Organocatalysts for the Asymmetric Michael Reaction of Aldehydes and Nitroalkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 4212–4215 (2005).

Mitchell, J. M. & Finney, N. S. An Efficient Method for the Preparation of N,N-disubstituted 1,2-Diamines. Tetrahedron Lett. 41, 8431–8434 (2000).

Okino, T., Hoashi, Y. & Takemoto, Y. Enantioselective Michael Reaction of Malonates to Nitroolefins Catalyzed by Bifunctional Organocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 12672–12673 (2003).

Mei, K. et al. Simple Cyclohexanediamine-Derived Primary Amine Thiourea Catalyzed Highly Enantioselective Conjugate Addition of Nitroalkanes to Enones. Org. Lett. 11, 2864–2867 (2009).

Cardinal-David, B., Raup, D. E. A. & Scheidt, K. A. Cooperative N-Heterocyclic Carbene / Lewis Acid Catalysis for Highly Stereoselective Annulation Reactions with Homoenolates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 5345–5347 (2010).

Raup, D. E. A., Cardinal-David, B., Holte, D. & Scheidt, K. A. Cooperative Catalysis by Carbenes and Lewis Acids in a Highly Stereoselective Route to γ-Lactams. Nat. Chem. 2, 766–771 (2010).

Höpfl, H. The Tetrahedral Character of the Boron Atom Newly Defined-A Useful Tool to Evaluate the N→B Bond. J. Organomet. Chem. 581, 129–149 (1999).

Reist, M., Testa, B., Carrupt, P.-A., Jung, M. & Schurig, V. Racemization, Enantiomerization, Diastereomerization, and Epimerization: Their Meaning and Pharmacological Significance. Chirality 7, 396–400 (1995).

Nguyen, V., Yan, Y., Zhao, J. & Yoon, J. Heavy-Atom-Free Photosensitizers: From Molecular Design to Applications in the Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 207–220 (2021).

Cho, M., So, I., Chun, J. N. & Jeon, J.-H. The Antitumor Effects of Geraniol: Modulation of Cancer Hallmark Pathways (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 48, 1772–1782 (2016).

Moraes, J. et al. Phytol, a Diterpene Alcohol from Chlorophyll, as a Drug against Neglected Tropical Disease Schistosomiasis Mansoni. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8, e2617 (2014).

Teng, K. et al. Designand Enantioselective Synthesis of Chiral Pyranone Fused Indole Derivatives with Antibacterial Activitiesagainst Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae for Protectionof Rice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 72, 4622–4629 (2024).

For applications of achiral tetracoordinate boron compounds in pesticide development, seeLiu, C. et al. Exploring Boron Applications in Modern Agriculture: A Structure-Activity Relationship Study of a Novel series of Multi-Substitution Benzoxaboroles for Identification of Potential Fungicides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 43, 128089–128096 (2021).

Sakthivel, K. et al. Intra-Degional Diversity of Rice Bacterial Blight Pathogen, Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, in the Andaman Islands, India: Revelation by Pathotyping and Multilocus Sequence Typing. J. Appl. Microbiol. 130, 1259–1272 (2021).

Rigano, L. A. et al. Biofilm Formation, Epiphytic Fitness, and Canker Development in Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20, 1222–1230 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD1700300). National Natural Science Foundation of China (22371057, 32172459, U23A20201). Science and Technology Department of Guizhou Province (Qiankehejichu-ZK [2021]Key033). The Central Government Guides Local Science and Technology Development Fund Projects [Qiankehezhongyindi (2024)007, (2023)001]. The Program of Major Scientific and Technological, Guizhou Province [Qiankehechengguo(2024)zhongda007]. Yongjiang Plan for Innovation and Entrepreneurship Leading Talent Project in the City of Nanning (2021005). The 10 Talent Plan (Shicengci) of Guizhou Province ([2016]5649). The Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities of China (111 Program, D20023) at Guizhou University. Singapore National Research Foundation under its NRF Competitive Research Program (NRF-CRP22-2019-0002); Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its MOE AcRF Tier 1 Award (RG84/22, RG70/21), MOE AcRF Tier 2 (MOE-T2EP10222-0006), and MOE AcRF Tier 3 Award (MOE2018-T3-1-003); a Chair Professorship Grant, and Nanyang Technological University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.N. conducted most of the experiments. S.V.C.V. conducted the DFT calculations and is estimated to contribute equally to this work. Y.Z., Y.S. and L.C. contributed to some experiments. Z.J., H.H., E.H., X.Z. and Y.R.C. conceptualized and directed the project and drafted the manuscript with assistance from all co-authors. All authors contributed to part of the experiments and/or discussions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks James Taylor, Xiao-Ye Wang, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nong, Y., Vummaleti, S.V.C., Zhang, Y. et al. Organocatalytic iminium-assisted asymmetric B(sp²)-to-B(sp³) transformation. Nat Commun 16, 10452 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65393-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65393-9