Abstract

The craton edge beneath southwestern Canada has been characterized as a ‘lithospheric step’ involving the transition from the warm Cordillera to an ancient, mechanically strong North American craton. Using converted shear waves that are sensitive to this boundary zone, this study shows a snapshot of this transition and reveals the existence of westward-dipping interfaces west of the Rocky Mountain Trench (RMT). These interfaces correlate well, both in location and conversion amplitude, with horizontal shear-velocity gradient zones within the craton core. In a span of 400-600 km west of the RMT, the presence of two distinctive horizontal structural gradients (at ~75 km and ~180 km) suggests a dual-lithosphere architecture, where the Precambrian craton core (Laurentia) now underlies the southeastern Cordilleran lithosphere. The morphology of the craton edge suggests influences from uplift and convective erosion over the past 60 million years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Marked by the rugged terrain of the Canadian Rocky Mountains, the mantle lithosphere west of the Cordillera-craton Boundary (CCB) is characterized as thin (~60 km) and uniform, largely formed in response to edge-driven, small-scale mantle convection in a back-arc setting1,2,3. Based on recent evidence from xenoliths4 and broadband seismic observations1,5, the anomalously thin Cordilleran lithosphere terminates abruptly near the Rocky Mountain Trench6,7 (RMT), where a young upper crustal fault appears to have developed between these two geologically distinct landmasses. The proposed CCB is abutted to the east and northeast by an ancient Laurentian lithospheric root, which is 100–200 km thicker6,8,9,10. The resulting lithospheric step near the CCB underscores sharp changes in subcrustal temperature2,3, morphology6,11, rheology12,13 and composition14,15.

The origin of the present-day craton boundary structure remains debated. Before 2015, it was widely believed that the evolution of the Cordillera was initiated by the break-up and rifting of the Neoproterozoic supercontinent ‘Rodinia'16, followed by episodes of tectonic convergence and landward-dipping subduction. The CCB began to form in the late Devonian16 and continued into the Mesozoic as the Panthalassic Ocean subducted beneath the western margin of North America16,17. For decades, landward subduction was widely regarded as a defining feature of the “accretionary” (non-collisional) model of Cordilleran orogenesis17. This geometry was supported by early electromagnetic and active-source seismic data18, but it was incompatible with a number of subsequent geological and geophysical observations19,20. More recently, results from shear wave tomography6,21 and dynamic calculation22 favored a steeper craton edge and emphasized contributions from edge-driven convection22 or lithosphere detachment21.

The proliferation of regional network data since 2015 (e.g., refs. 23,24) has enabled an appraisal of earlier proposed models of Cordillera-craton interaction (e.g., refs. 16,19,20,25,26). Tomographic imaging based on improved data6,27,28 provides support for an alternative hypothesis centered on a late Cretaceous collision between an exotic Cordilleran ribbon continent and the North American (NA) craton, favoring west-dipping subduction beneath the Cordillera20. The presence of a cryptic collisional suture near the RMT is corroborated by geological observations, e.g., the existence of a carbonatite belt29, and recent geodynamical calculations11,14. Details of westward subduction model (e.g., subduction boundary location and geometry) are crucial for 1) understanding the paleogeographic evolution that culminated in orogenesis; and 2) determining whether orogenesis involved the accretion of exotic lithosphere, simple deformation of existing lithosphere, or some combination of the two.

This study examines potential shallow mantle interfaces beneath the Cordillera-craton transition zone by utilizing S-to-p converted waves resulting from impedance contrasts. We find compelling evidence for an enigmatic suture that is attributable to west-dipping subduction in the upper-mantle. According to our observations, the eastern Cordilleran lithosphere is underlain by the cratonic lithosphere, forming a complex, multi-layered upper-mantle architecture. The geometry of the Moho and the Lithosphere-Asthenosphere Boundary (LAB) across the Foreland margin (the deformation front) of an orogen provides direct constraints on the orogen-autochthon relationship. Commonly, continuity of the Moho and LAB from beneath an orogen out into the autochthon is interpreted as evidence of an autochthonous origin. In contrast, discontinuities affecting either the Moho or the LAB, including dual LABs and stacked Mohos, are commonly associated with 1) suturing of previously disparate lithospheric plates, or 2) significant post-orogenic modification of the lithospheric mantle30,31.

For simplicity, we refer to the lower boundaries of the Cordilleran and NA cratonic lithospheres as the Cordillera Lithosphere-Asthenosphere Boundary (CLAB) and Laurentia Lithosphere-Asthenosphere Boundary (LLAB), respectively.

Results

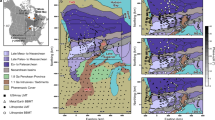

Our dataset comprises recordings from 107 broadband stations, including 40 from the USArray32 (Fig. 1), which substantially improves the data coverages and volumes examined by earlier regional studies of mantle converted waves (e.g., refs. 1,33). After component rotation (to great-circle path), filtering, and spectral deconvolution, we retained 3968 high-quality SRFs in the frequency range of 0.02–0.2 (or 0.1) Hz and depth-migrated the time axis using PREM34. The predefined discontinuity at 220 km depth, a feature of PREM34, can produce absolute depth errors no greater than 5 km after migrating the S-to-p converted phases (see Supplementary Material “Synthetics”).

a Map view of regional tectonic provinces and surface topography109. Hatched areas indicate different tectonic provinces and ages. Colored symbols denote 107 broadband seismic stations from 4 networks used in this study. Major tectonic boundaries are delineated by colored lines. The red circle highlights station SLEB, which was analyzed by Miller and Eaton33 and revealed mantle conversions at ~100 km and 180 km depths. Abbreviations: ME2010 Miller and Eaton33; BHT Buffalo Head Terrane, BHH Buffalo Head Hills, BM Birch Mountain, CDF Cordilleran Deformation Front, GSLSZ Great Slave Lake Shear Zone, RMT Rocky Mountain Trench, GFTZ Great Falls Shear Zone, STZ Snowbird Tectonic Zone, Ta Taltson magmatic zone, THO Trans-Hudson Orogen, VS Vulcan Structure, ML Mountain Lake. b Event (red circles, mainly occurred from 2014 to 2019) used in SRF computation110. The blue polygon marks the boundaries of the study area.

The majority of receiver functions after undergoing stacking and bootstrapping analysis (see Supplementary Fig. S6) show robust negative phases in the depth range of 50–350 km, which are typically associated with earlier-reported lithospheric interfaces35,36,37. Spatially interpolated depths of major negative gradients (phase 1, Fig. 2) approximately follow a Gaussian distribution centered at an average of 207 ± 3 [2σ] km. Approximately 75% of the observations fall within one sigma, whereas outliers near 1.98–1.90 Ga-aged Kiskatinaw and Ksituan domains in northwestern Alberta (block A, Fig. 2) are deeper than 230 km. The azimuthal coverage at our stations is biased toward NE–SW orientations. Despite detecting consistent phases associated with the LLAB and CLAB on individual SRFs (see Supplementary “Resolution”), the limited range of angles prohibits a systematic analysis of the azimuth-dependency of mantle conversions.

a Color-coded depths that correspond to the maximum amplitudes (Phase 1) of stacked SRFs. The time-to-depth migration is computed based on PREM34. Grey and white circles indicate the clusters of stations used to compute the mean SRFs. Red rectangles mark five sub-regions. b Sample SRF stacks from our study region. SRF results for all data are filtered between 0.02 and 0.2 Hz (or 0.1 Hz). Grey and red colors correspond to velocity increase and decrease with depth, respectively. Solid black lines show stacked SRFs, and blue dashed lines mark the averages of bootstrapping stacks (light grey lines). The error envelopes (black dashed lines) correspond to the ±2σ confidence intervals of stacked amplitudes. The algorithm of bootstrap resampling can be found in the method and supplementary information, and the maximum amplitude of each SRF is normalized to unity. The interpreted Laurentia Lithosphere-Asthenosphere Boundary (LLAB) and Cordillera Lithosphere-Asthenosphere Boundary (CLAB) are marked using vertical cyan and blue lines, respectively. c The mean SRFs of the Cordillera and the Craton computed from subsets of stations (white and grey circles) shown in (a). The vertical blue and cyan lines indicate the seismic phases corresponding to CLAB and LLAB, respectively.

From the Buffalo Head Terrane (BHT) to the southern Hearne province, the strongest lithospheric gradient (see Fig. 2a, blocks B, C, and D) progressively deepens by more than 20 km towards the southeast where the cratonic basement is covered by 3 km thick Phanerozoic sedimentary strata38. This conversion occurs at ~180 km depth beneath the center of the BHT, which indicates a locally thinned lithosphere consistent with estimated depths from kimberlite xenolith thermobarometry39,40, electrical resistivity41, and heat flow42 data. The most important outcome of our SRF analysis is the identification of the LLAB beneath eastern Cordillera at ~180 km depth (see Fig. 2a, block E).

This deep, sub-Cordilleran LLAB is quantitatively different from the CLAB, which we also identify through a series of west-dipping phases (at ~75 km), and it is not directly associated with the reported ‘lithospheric-step’ (e.g., ref. 14). The most compelling evidence of sub-Cordilleran interfaces and their connections to the adjacent NA craton is regional stacks of SRFs on either side of the RMT. On the craton side, only a single interface at ~220 km, i.e., the LLAB, is detected within the broad depth range of 50–250 km. On the other hand, the upper mantle beneath eastern Cordillera contains distinct interfaces at 180 and 75 km depths. Despite a reduced amplitude and considerable waveform complexities, the CLAB signature is recognizable above ambient noise levels.

Cordillera lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary (region ‘1’)

The SRFs from our study provide unique and reliable constraints on the physical properties of the CLAB (e.g., depth) due to their strong sensitivity to velocity gradient. The average CLAB depth is 75 ± 17 km (see Fig. 2c), after applying timing corrections43 for mantle heterogeneity44, elevation and crustal thickness (CRUST1.045; Supplementary Fig. S3). Three parallel profiles of eastern Cordillera show multiple negative SRF arrivals associated with CLAB west of the RMT (see Fig. 3a, region ‘1’; Fig. 3b–d). Devoid of significant north-south variations (see Fig. 3b–d), a uniform CLAB is consistent with the earlier reported LAB depth (60-85 km) in the western portion of the Cordillera (e.g., refs. 46,47,48). According to synthetic SRFs calculated from a constant, low P-wave velocity layer (from 60 to 85 km depth; see Supplementary Fig. S9), a thin and hot eastern Cordilleran lithosphere11,28,49,50,51 is capable of producing a negative conversion with a 20–50% relative conversion amplitude to direct S. Our observed CLAB depth (70–75 km) is within uncertainty of the average depth (65 ± 5 km) of chemical equilibration of Cenozoic to recent mantle-xenolith bearing alkaline lavas of the Canadian Cordillera15.

a Laurentia Lithosphere-Asthenosphere Boundary (LLAB) depth perturbations from the regional average. Colored solid lines delineate the surface traces of three different profiles; seismic stations share color conventions with the corresponding profile line. The region shaded in gray is the Cordillera-craton boundary zone, estimated from recent tomographic models and thermal boundary definitions (e.g., refs. 6,7,8,9,28). Regions numbered from 1 to 3 denote the Cordillera, craton, and Cordillera-craton transition zone, respectively. b–d S receiver functions (black-shaded) superimposed on shear velocities from surface wave tomographic inversions10,79. Thin, solid white lines indicate 1.2% and 0.1% perturbations in velocity. Surface elevation (grey-shaded polygons) and Bouguer gravity111 (blue lines) are plotted on top of each profile. The LLAB is denoted by a horizontal pink line at each station, and measurements from all stations are subsequently interpolated (linearly) using thick, white dashed lines.

The simplest explanation for a negative shallow mantle velocity gradient is increased mantle temperature. For decades, a shallow asthenosphere with elevated temperatures has been proposed to isostatically compensate for a 30–48 km shallow, thin and flat Moho (e.g., refs. 2,52,53) and a negative Bouguer gravity anomaly54 beneath the uplifted mountainous terrain west of the RMT (~1500 m high; Fig. 3). Geothermal observations4,11,46,55,56 suggest that the Cordilleran back-arc mantle temperature at the CLAB exceeds 1200 °C, nearly 400 °C higher than those within the craton to the east at similar depths. Partial melt, small-scale convection and a wet upper asthenosphere (e.g., refs. 7,15,22,55,57) further complicate the thermochemical properties of the Cordilleran upper mantle. These defining characteristics diminish gradually near the eastern edge of the Cordilleran lithosphere, where the CLAB ramps upward towards the Moho of the NA craton near the RMT. Similar mantle conversions have been previously detected by Miller & Eaton33 at 100 km and 180 km depths beneath station SLEB (labelled ME2010, see Fig. 1).

It is worth noting that the long-period nature of S converted waves limits their spatial resolution in mapping the geometry of lithospheric discontinuities. Further complexities could result from corner diffractions, which weaken the SRF’s ability to resolve sharp deflections58, relatively sparse station density (especially north of 49 ° N) and back-azimuth coverage. 3-D effects on ray paths may introduce additional uncertainties to our observations (detailed information is provided in the Supplementary material “Resolution”).

Laurentia lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary east of the foothills (region ‘2’)

In a 150 km wide area between the RMT and Cordillera Deformation Front (CDF), which we define as the Cordillera-craton transition zone (Fig. 3a, region 3), the 75-km deep CLAB transitions sharply to the LLAB at a regional average depth of ~207 km. The lithosphere beneath the Archean Hearne Province is notably thick, extending to ~220 km. This estimate is in general agreement with thermal thickness calculations (~200–220 km), defined by the intersection of a geotherm with the mantle adiabat59 (T = 1300 °C), as well as constraints from garnet xenoliths from depths below 200 km60. These depths are only moderately shallower than those proposed by seismic tomography5,61 (deeper than 250 km) and an earlier magnetotelluric survey62 (~250 km). Differences in data sampling and depth sensitivity37,63 could be partially responsible for the different reported craton depths. The localized LLAB is characterized as a strong amplitude in the SRF data (see Fig. 2c), and its depth is comparable to that of the Precambrian lithosphere64. Regional tomographic models (e.g., ref. 9) indicate shear velocity perturbations in excess of 4% beneath the Laurentian lithosphere, and up to 9% beneath the nearby cratons according to recent studies of SS precursors (e.g., ref. 65). The strong velocity gradients reflect a combination of physical and chemical properties variations within the Laurentian lithosphere, such as dehydration and past partial melting events associated with the cratonic lithosphere. The vertical variations in Mg#, water, and Fe59,66,67,68, as well as anisotropy variations10,69 could all contribute to a strong mantle gradient near the base of the NA craton. Differences aside, the compelling evidence of a relatively deep and stable LLAB favors a long-lived Archean Hearne lithosphere60,70 that has undergone minimal modifications since the Paleoproterozoic71.

The lithospheric root of the Hearne province shallows to ~200 km beneath the Medicine Hat block (MHB) and ~180 km beneath the Buffalo Head Terrane (BHT). For the former region (i.e., MHB) the Archean-aged lithosphere has undergone significant reworking due to Paleoproterozoic subduction and magmatism62,72,73, which may have resulted in partial removal of the craton root. In the case of BHT, evidence from garnet lherzolite xenolith and magnetotelluric surveys has favored a lithosphere as thin as 180 km39,41, which is in general agreement with our findings (~180 km) from SRFs. Partial melting triggered by hydration from subduction74 or upwelling of low-velocity asthenosphere75 are both capable of causing lithospheric modification and erosion15,76. These processes may have eroded and thinned the lithosphere beneath this region.

Cordillera—craton transition zone (region ‘3’)

An essential feature from the profiles is the west-dipping CLAB near the RMT (see Fig. 3b–d). This morphology is concordant with models of the Mid- to Late Cretaceous Cordilleran orogenesis, which implies that it resulted from interactions between an allochthonous ribbon continent and the NA craton19,20,77. Closure by westward subduction of the ocean basin east of the Cordillera, which continued into the passive west-margin of cratonic NA, and post-collision slab break-off78 were the most significant tectonic events at the former convergent boundary. To ascertain the orientation of the subduction interface, we linearly fit the depths of the conversions in an area bounded by 150 km west of the RMT and 120 km east of it. The slope of the CLAB is consistent with a westerly dip of 6 °, nearly identical to the slope of a gradient zone based on the 0% shear wave velocity contour in model NA1479. This dip angle is significantly lower than has been suggested by other studies using body 6 (~70°) and surface28,80 (20–30°) waves at similar positions. We attribute this discrepancy to 1) sparse regional station coverage in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin, which hampers the spatial resolution of global surface-wave-based models, and 2) vertical smearing along ray paths8,35,81 from tomographic inversions, especially in the case of body waves. In other words, the boundary between NA and the Cordillera is gentler than a vertical ‘lithospheric step’. Its westward dip contradicts the accretion model, which proposes long-lived1 and landward-dipping (i.e., opposite) subduction beneath the western margin of the Cordillera, during which the Cordilleran lithosphere either underwent thinning or was detached17,25,78.

A related physical description of the Cordillera-craton boundary is ‘suture zone’. Without a consensus, various geophysical and geological studies have placed the eastern edge of the CLAB at the CDF8, RMT6,7, or the Omineca belt4,82. In the averaged SRF profiles (see Fig. 4), conversions associated with the CLAB are relatively diminished at a depth of ~38 km and a position that is ~100 km east of the RMT (near the eastern end of profile). Despite minor variations among different transects (see Fig. 3), e.g., a westward extension of the Cordillera-craton transition zone at ~47 ° latitude in profile C, the geometry of the CCB relative to the RMT appears stable and uniform across the latitude range from 46 °N to 50 °N. According to Audet et al.1, this west-dipping interface may extend as far north as northern British Columbia (~60 °N), based on their experiments involving P-to-s converted waves, seismic velocities, geothermal modelling and time-dependent thermal simulations.

The background shows averaged shear velocities from profiles AA’, BB’, and CC’ (NA1479). White lines are contours of seismic velocity perturbations at −0.3%, 0%, 0.5% and 0.8%. Different symbols represent our picks for the Cordillera Lithosphere-Asthenosphere Boundary (CLAB), Laurentia Lithosphere-Asthenosphere Boundary (LLAB), and phase ‘X’ from each receiver function stack. Dashed lines are the linear least-squares fit to our measured depths of the CLAB, LLAB, phase ‘X’ at all receivers. Slopes of fitted functions are utilized to evaluate the geometries of the corresponding contrasts. The left panel shows the westward extension of the velocity profile and the fitting functions. The intersection points between CLAB, LLAB and phase ‘X’ are marked with solid grey circles. Slopes from linear least-squares are: CLAB: k = 0.11, root mean square error (RMSE) = 9.66; LLAB: k = −0.12, RMSE = 9.86; 0% velocity contour: k = 0.11, RMSE = 2.07; Phase ‘X’: k = 0.17, RMSE = 10.63.

Western LLAB and dual-layered lithosphere architecture

Judging from the westward continuity of the LLAB (see Fig. 3b–d), the western edge of the intact craton core extends to ~200 km west of the suggested locations from recent tomographic inversions6,28. The upper surface of the intact craton lithosphere is delineated by two semi-parallel, westward dipping (labelled CLAB and phase ‘X’ in Fig. 4) S-to-p conversions with an average separation depth of 50 km. Phase ‘X’ is interpreted as a relic of an oceanic plate that now lies directly above the cratonic lithosphere78. By linearly fitting the depths of phase ‘X’ (see Supplementary material for a robustness estimate) and LLAB (see Fig. 4), which are associated with the top and bottom surfaces of the NA craton, we estimate the western craton margin to be positioned at ~320 km west of the RMT, at a depth of 165 km. This depth is notably shallower than the regional average of ~220 km, a relatively stable value expected for a craton margin that has not undergone major deformations in the past 100 million years50,83,84.

We attribute the progressive westward thinning of the NA craton to erosion, in combination with an uplift caused by a highly convective sub-Cordilleran mantle76,85. Observations of seismic anisotropy86 and geodynamic modelling14,87 suggest that a southwestward mantle wind could exceed 4 cm/yr in the back-arc of the Juan de Fuca subduction zone88,89. In spite of the strength and rigidity of the craton core7, the severity of the convective flow over the past 100 million years is fully capable of shearing the craton margin and elevating the boundary via the pressure differences between the top (low pressure) and bottom (high pressure) of the craton lithosphere14.

A boundary zone dominated by westward subduction resulted in a dual-layered lithosphere architecture in a 300–500 km wide window between the eastern intermontane and the RMT (Fig. 5). This complex geometry includes cratonic Laurentian lithosphere that extends down to ~180 km, directly underlying the Cordilleran lithosphere, which terminates at a depth of ~75 km. The geological evolution that led to the development of the stacked lithospheres includes Neoproterozoic rifting and the subsequent formation of the western Laurentian passive margin; the Devonian to Cretaceous development of a Cordilleran ribbon continent that lay west of cratonic NA, and the mid-Cretaceous closure of the basin separating the ribbon continent from cratonic NA by west-dipping subduction beneath the Cordilleran ribbon continent’s eastern margin. Post-collisional slab break-off at ~95 Ma detached the westward subducting oceanic slab that subsequently foundered into the deep mantle26, leaving behind the westward dipping Laurentian continental lithosphere that had been pulled into and beneath the Cordilleran upper plate by the subducting slab78 and a small remnant of the former oceanic plate (see Fig. 5).

The side panels show averaged S receiver function (SRF)s for both the Cordillera and the North American (NA) craton and the horizontal blue lines mark the depths of mantle lithosphere. The averaged SRF of Cordillera reveals two comparable negative phases (10% amplitude difference) at 72 km and 207 km, which we interpret as the Cordillera Lithosphere-Asthenosphere Boundary (CLAB) and Laurentia Lithosphere-Asthenosphere Boundary (LLAB), respectively. On the other hand, SRF stack from the cratonic region shows a single (negative) peak at 214 km in connection with the LLAB. Interpreted Moho depths are shown by grey lines at ~35 km for the Cordillera and ~40 km for the NA craton. Arrows indicate inferred mantle flow in the study region. Relative to cratons, the Cordilleran SRF (red shading) suggests a dual-layered lithospheric architecture.

Cratonic lithosphere, when continuous with and attached to subducting oceanic lithosphere, will be dragged into and beneath thinner, arc-bearing upper plate lithosphere. It becomes resistant to subduction due to buoyancy forces, and the resulting duplication of the LAB by lithospheric stacking across a collisional convergent margin is predicted by plate tectonics. The complex lithosphere architecture revealed by our SRF observations is consistent with 1) attempted westward subduction of cratonic Laurentia beneath the Cordillera19,20, and 2) tomographic models that image the Laurentian cratonic lithosphere juxtaposed against and extending beneath the Cordilleran lithosphere1,6. A modern-day parallel is the Tibetan Plateau, where attempted northward subduction of cratonic India beneath Asia gave rise to a lithospheric stack and the development of a complex, multi-layered lithospheric architecture down to 250 km90. Older examples include the Paleoproterozoic stacking of cratonic lithosphere of the western Slave Province beneath the eastern Slave Province to depths greater than 200 km91, and the Archean Sask Craton that was, together with its diamondiferous mantle root, completely overthrust by the Hearne Craton during the Paleoproterozoic Trans-Hudson orogeny92.

Collectively, by taking advantage of SRFs from regional seismic arrays, we are able to reach a few key conclusions pertaining to the Cordillera-craton transition region,

-

1)

The base of the Cordilleran lithosphere directly overlays a wedge-shaped Laurentian lithosphere that bottoms at ~180 km. Together, they form a unique dual-layered lithosphere architecture.

-

2)

The western NA craton boundary dips westward at an approximate angle of 6 degrees. Its present-day morphology may be strongly influenced by Mesozoic subduction, slab break-off and mantle convection.

-

3)

The NA craton edge shows evidence of convective erosion and possible uplift within a window from the RMT to the Intermontane belt.

Our study offers compelling evidence for a multi-layered lithospheric architecture beneath the eastern Cordillera. Granted, many of the inferences from SRFs may be impacted, to varying degrees, by limited azimuthal coverage, depth sensitivity and 3-dimensional nature of the raypaths. They do, however, provide an impetus for a better understanding of the Cordillera-craton boundary evolution, especially when aided by improved constraints from seismic tomography, geological sampling and geodynamic modelling.

Method

This study utilizes the frequency domain water-level S receiver function technique93,94 to analyze S-to-p converted waves resulting from mantle interfaces (see Fig. S1(a)). Since S-to-p converted waves travel faster than direct S, their waveforms are minimally affected by multiple-reflected S. This is a distinct advantage over P-to-s conversions, which are commonly used in crust and mantle imaging but suffer from contaminations from P wave coda at lithospheric depths69,94,95 (see Fig. S1(c)).

Our S receiver function technique contains two initial steps: 1) signal partitioning that isolates the incident from scattered wavefields, and 2) deconvolution that minimizes source and propagation effects94. The resulting receiver functions are subsequently corrected for epicentral distance (via time shifts) and stacked according to the locations of the conversion points (see below).

Dataset

Our dataset includes 15 permanent stations from the Canadian National Seismograph Network96 (CNSN) spanning 2014 to 2019, 40 temporary stations from USArray operational between 2006 and 201097 (TA), 24 stations from the Regional Alberta Observatory for Earthquake Studies Network24 (RAVEN), and 28 stations from the Canadian Rockies and Alberta Network23 (CRANE) covering the same period. To ensure optimal receiver function results, we limit our earthquake selection to magnitudes equal to or greater than 5.5 and epicentral distances ranging from 55° to 85°. Additionally, only earthquakes with depths shallower than 150 km are included to mitigate the impact of depth phases98,99. All waveform data were obtained from the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS) Data Management Center based on events listed in the USGS National Earthquake Information Center catalogue. We processed over 20,000 waveforms from more than 2,000 seismic events to produce about 3,900 high-quality SRF traces.

Wavefield isolation

Before deconvolution, we apply a transformation matrix to the recorded wavefield to enhance weak converted waves by recasting the coordinate into the L-Q-T system95,100,101 (see Fig. S1(a)). First, we convert local N-E-Z system into R-T-Z system by:

where N, E, and Z are the North-South, East-West, and vertical components of the seismogram, respectively. The outputs R, T, and Z are the radial, transverse and vertical component seismograms. Inside the transformation matrix, γ represents the back azimuth of the incident wave. Then, we rotate R–T–Z components into L-Q-T coordinates by:

where \(i=\arcsin {P}_{i}\) is the angle between incident P-wave and the vertical axis. After the rotation, S-to-p converted waves are polarized approximately along the L direction.

Deconvolution

For each event-station pair, we apply a third-order Butterworth filter with corner frequencies of 0.02 Hz and 0.1 Hz, or 0.01 Hz and 0.2 Hz, parameters that are commonly adopted by earlier studies of North America (e.g., refs. 69,98,102). We then deconvolve the L component from the Q component using frequency domain water-level deconvolution103,104. To obtain optimal results, a water-level parameter of 0.01105 was chosen empirically (see Fig. S2) to balance resolution and stability (Supplementary Data 1).

The water-level deconvolution computation follows the equation:

Where,

In these three equations, * denotes the complex conjugate and \(u\left(\omega \right)\) is the seismic signal after transforming to the frequency domain. The constant c is the water level that controls the minimum amplitude allowed in the denominator during deconvolution. In Eq. 5, \(G(\omega )\) is the conventional Gaussian filter for smoothing, the constant \(\xi\) normalizes the filter to unit amplitude, and α controls the width of the Gaussian pulse.

Deconvolved seismograms are then migrated to depth based on the original PREM34. The uncertainty introduced by the 220 km discontinuity in PREM during migration is estimated to be within ±5 km (see Supplementary Figs. S11 and S13). All receiver functions recorded by a given station are then stacked to form a single trace. It is worth noting that only minor differences could be found among different binning procedures (e.g., stacking according to conversion points).

The time corrections for lateral heterogeneity43,44 and crust45 (CRUST1.0) are applied based on 1-D ray tracing. The resulting correction value (Fig. S3(a) to (c)) is then applied to all SRFs (see Fig. S3(d)). We visually inspect and reject traces with high pre-signal noise and abnormal reverberations. SRFs have been reversed in their polarity and depth axis to represent a velocity decrease using negative arrivals.

Negative phases after the Moho conversion (~35 km beneath Cordillera and ~40 km beneath craton) are generally caused by reduced velocities (e.g., at the base of the lithosphere). Supplementary Fig. S4 shows an S receiver function example.

Bootstrap resampling

We estimate the uncertainty of SRF by the bootstrap resampling method106. For each station, 20% of quality-controlled SRF traces are randomly selected to create a bootstrapped stack, repeated 100 times to generate multiple stacks. Then we compute the mean and standard deviation of the distribution69,106,107, the latter of which offers an effective estimate of the uncertainty. Well-behaved S receiver functions generally fit within the +2σ (95% confidence level) of the bootstrapped mean. Similarly, errors in depth (d) and amplitude (a) are quantified by their departures from the respective mean values at the base of the lithosphere (see Fig. S1).

Data availability

Seismic data for CNSN network can be requested from Canadian National Data Center (https://www.earthquakescanada.nrcan.gc.ca/stndon/CNSN-RNSC/index-en.php). The original CRANE seismic records can be accessed upon request from the seismic network operator. The IRIS Data Management Center (http://ds.iris.edu/ds/nodes/dmc/) was used to access waveforms, and data from the TA network were made freely available as part of the EarthScope USArray facility. Both data sources are supported by the National Science Foundation under cooperative agreement EAR-1261681. The processed seismic data and S receiver functions generated in this study have been deposited in the corresponding Code Ocean capsule108.

Code availability

The codes of receiver function analysis are available from the Code Ocean capsule108.

References

Audet, P., Currie, C. A., Schaeffer, A. J. & Hill, A. M. Seismic evidence for lithospheric thinning and heat in the Northern Canadian Cordillera. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 4249–4257 (2019).

Hyndman, R. D. The consequences of Canadian Cordillera thermal regime in recent tectonics and elevation: a review. Can. J. Earth Sci. 47, 621–632 (2010).

Hyndman, R. D. & Currie, C. A. Why is the North America Cordillera high? Hot backarcs, thermal isostasy, and mountain belts. Geology 39, 783–786 (2011).

Canil, D. & Russell, J. K. Xenoliths reveal a hot Moho and thin lithosphere at the Cordillera-craton boundary of western Canada. Geology 50, 1135–1139 (2022).

Bao, X. & Eaton, D. W. Large variations in lithospheric thickness of western Laurentia: tectonic inheritance or collisional reworking?. Precambrian Res. 266, 579–586 (2015).

Chen, Y. et al. Seismic evidence for a mantle suture and implications for the origin of the Canadian Cordillera. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–10 (2019).

Hyndman, R. D. & Lewis, T. J. Geophysical consequences of the Cordillera-Craton thermal transition in southwestern Canada. Tectonophysics 306, 397–422 (1999).

Mercier, J. P. et al. Body-wave tomography of western Canada. Tectonophysics 475, 480–492 (2009).

Schaeffer, A. J. & Lebedev, S. Imaging the North American continent using waveform inversion of global and USArray data. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 402, 26–41 (2014).

Yuan, H. & Romanowicz, B. Lithospheric layering in the North American craton. Nature 466, 1063–1068 (2010).

Yu, T. C., Currie, C. A., Unsworth, M. J. & Chase, B. F. W. The structure and dynamics of the uppermost mantle of southwestern Canada from a joint analysis of geophysical observations. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 127, e2022JB024130 (2022).

Saylor, J. E., Rudolph, K. W., Sundell, K. E. & van Wijk, J. Laramide orogenesis driven by Late Cretaceous weakening of the North American lithosphere. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125, e2020JB019570 (2020).

Tesauro, M., Kaban, M. K. & Mooney, W. D. Variations of the lithospheric strength and elastic thickness in North America. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 16, 2197–2220 (2015).

Currie, C. A. et al. Mantle structure and dynamics at the eastern boundary of the northern Cascadia backarc. J. Geodynamics 155, 101958 (2023).

Hyndman, R. D. & Canil, D. Geophysical and geochemical constraints on Neogene-recent volcanism in the North American Cordillera. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 22, 1–25 (2021).

Dickinson, W. R. Evolution of the North American Cordillera. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 32, 13–45 (2004).

Monger, J. W. H. & Price, R. A. The Canadian Cordillera: geology and tectonic evolution. CSEG Rec. 17, 36 (2002).

Cook, F. A. & Erdmer, P. An 1800 km cross section of the lithosphere through the northwestern North American plate: Lessons from 4.0 billion years of Earth’s history. Can. J. Earth Sci. 42, 1295–1311 (2005).

Hildebrand, R. S. Did westward subduction cause Cretaceous-Tertiary orogeny in the North American Cordillera? Special Paper of the. Geol. Soc. Am. 457, 1–71 (2009).

Johnston, S. T. The Cordilleran ribbon continent of North America. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 36, 495–530 (2008).

Bao, X., Eaton, D. W. & Guest, B. Plateau uplift in western Canada caused by lithospheric delamination along a craton edge. Nat. Geosci. 7, 830–833 (2014).

Currie, C. A. & Hyndman, R. D. The thermal structure of subduction zone back arcs. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 111, 1–22 (2006).

Gu, Y. J., Okeler, A., Shen, L. & Contenti, S. The Canadian Rockies and Alberta Network (CRANE): New constraints on the Rockies and Western Canada Sedimentary Basin. Seismol. Res. Lett. 82, 575–588 (2011).

Schultz, R. & Stern, V. The regional Alberta Observatory for earthquake studies network (RAVEN). CSEG Recorder 40, 34–37 (2015).

DeCelles, P. G. Late Jurassic to Eocene evolution of the Cordilleran thrust belt and foreland basin system, western U.S.A. Am. J. Sci. 304, 105–168 (2004).

Sigloch, K. & Mihalynuk, M. G. Intra-oceanic subduction shaped the assembly of Cordilleran North America. Nature 496, 50–56 (2013).

Estève, C. et al. Surface-wave tomography of the Northern Canadian Cordillera using earthquake rayleigh wave group velocities. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, 1–22 (2021).

Zaporozan, T., Frederiksen, A. W., Bryksin, A. & Darbyshire, F. Surface-wave images of western Canada: Lithospheric variations across the Cordillera–craton boundary. Can. J. Earth Sci. 55, 887–896 (2018).

McLeish, D. F. & Johnston, S. T. The Upper Devonian Aley carbonatite, NE British Columbia: a product of Antler orogenesis in the western Foreland Belt of the Canadian Cordillera. J. Geol. Soc. 176, 620–628 (2019).

Clowes, R. Logan Medallist 2. Geophysics and geology: an essential combination illustrated by LITHOPROBE interpretations–part 1, lithospheric examples. Geocan 42, 27–60 (2015).

Dong, S.-W. et al. Progress in deep lithospheric exploration of the continental China: a review of the SinoProbe. Tectonophys. Spec. Issue Deriv. “Int. Symp. Deep Exploration into Lithosphere”, Beijing 606, 1–13 (2013).

Meltzer, A. et al. USArray initiative. GSA Today 9, 8–10 (1999).

Miller, M. S. & Eaton, D. W. Formation of cratonic mantle keels by arc accretion: evidence from S receiver functions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, 1–5 (2010).

Dziewonski, A. M. & Anderson, D. L. Preliminary reference Earth model. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 25, 297–356 (1981).

Artemieva, I. M. The continental lithosphere: reconciling thermal, seismic, and petrologic data. Lithos 109, 23–46 (2009).

Priestley, K., McKenzie, D. and Ho, T. A Lithosphere–asthenosphere boundary—a global model derived from multimode surface-wave tomography and petrology. In Lithospheric Discontinuities (eds H. Yuan and B. Romanowicz) (2018).

Rychert, C. A., Shearer, P. M. & Fischer, K. M. Scattered wave imaging of the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary. Lithos 120, 173–185 (2010).

Cook, F. A. et al. How the crust meets the mantle: Lithoprobe perspectives on the Mohorovičić discontinuity and crust-mantle transition. Can. J. Earth Sci. 47, 315–351 (2010).

Aulbach, S., Griffin, W. L., O’Reilly, S. Y. & McCandless, T. E. Genesis and evolution of the lithospheric mantle beneath the Buffalo Head Terrane, Alberta (Canada). Lithos 77, 413–451 (2004).

Faure, S., Godey, S., Fallara, F. & Trépanier, S. Seismic Architecture of the Archean North American Mantle and Its Relationship to Diamondiferous Kimberlite Fields. Econ. Geol. 106, 223–240 (2011).

Türkoǧlu, E., Unsworth, M. & Pana, D. Deep electrical structure of northern Alberta (Canada): implications for diamond exploration. Can. J. Earth Sci. 46, 139–154 (2009).

Majorowicz, J. A. Heat flow–heat production relationship not found: what drives heat flow variability of the Western Canadian foreland basin?. Int. J. Earth Sci. 107, 5–18 (2018).

Geissler, W. H., Sodoudi, F. & Kind, R. Thickness of the central and eastern European lithosphere as seen by S receiver functions. Geophys. J. Int. 181, 604–634 (2010).

Ritsema, J., Van Heijst, H. J. & Woodhouse, J. H. Complex shear wave velocity structure imaged beneath Africa and Iceland. Science 286, 1925–1931 (1999).

Laske, G., Masters, G., Ma, Z. & Pasyanos, M. Update on CRUST1.0—a 1-degree global model of Earth’s crust. Geophys. Res. Abstr. 15, 2658 (2013).

Hansen, S. M., Dueker, K. & Schmandt, B. Thermal classification of lithospheric discontinuities beneath USArray. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 431, 36–47 (2015).

Hopper, E. & Fischer, K. M. The changing face of the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary: imaging continental scale patterns in upper mantle structure across the contiguous U.S. With Sp converted waves. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 2593–2614 (2018).

Liu, L. & Gao, S. S. Lithospheric layering beneath the contiguous United States constrained by S-to-P receiver functions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 495, 79–86 (2018).

Flück, P., Hyndman, R. D. & Lowe, C. Effective elastic thickness Te of the lithosphere in western Canada. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 108, 2430 (2003).

Mooney, W. D. & Kaban, M. K. The North American upper mantle: density, composition, and evolution. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 115, 1–24 (2010).

Soyer, W. & Unsworth, M. J. Deep electrical structure of the northern Cascadia (British Columbia, Canada) subduction zone: implications for the distribution of fluids. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 127, 53–56 (2006).

Clowes, R. M., Zelt, C. A., Amor, J. R. & Ellis, R. M. Lithospheric structure in the southern Canadian Cordillera from a network of seismic refraction lines. Can. J. Earth Sci. 32, 1485–1513 (1995).

Tarayoun, A., Audet, P., Mazzotti, S. & Ashoori, A. Architecture of the crust and uppermost mantle in the northern Canadian Cordillera from receiver functions. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 122, 5268–5287 (2017).

Cook, F. A., Varsek, J. L. & Thurston, J. B. Tectonic significance of gravity and magnetic variations along the Lithoprobe Southern Canadian Cordillera Transect. Can. J. Earth Sci. 32, 1584–1610 (1995).

Ghent, E. D., Edwards, B. R. & Russell, J. K. Pargasite-bearing vein in spinel lherzolite from the mantle lithosphere of the North America Cordillera. Can. J. Earth Sci. 56, 870–885 (2019).

Harder, M. & Russell, J. K. Thermal state of the upper mantle beneath the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province (NCVP), British Columbia, Canada. Lithos 87, 1–22 (2006).

Morales, L. F. G. & Tommasi, A. Composition, textures, seismic and thermal anisotropies of xenoliths from a thin and hot lithospheric mantle (Summit Lake, southern Canadian Cordillera). Tectonophysics 507, 1–15 (2011).

Lekić, V. & Fischer, K. M. Interpreting spatially stacked Sp receiver functions. Geophys. J. Int. 210, 874–886 (2017).

Artemieva, I. M. & Mooney, W. D. Thermal thickness and evolution of Precambrian lithosphere: A global study. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 106, 16387–16414 (2001).

Canil, D., Schulze, D. J., Hall, D., Hearn, B. C. & Milliken, S. M. Lithospheric roots beneath western Laurentia: The geochemical signal in mantle garnets. Can. J. Earth Sci. 40, 1027–1051 (2003).

Chen, Y., Gu, Y. J. & Hung, S. H. Finite-frequency P-wave tomography of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin: Implications for the lithospheric evolution in Western Laurentia. Tectonophysics 698, 79–90 (2017).

Nieuwenhuis, G., Unsworth, M. J., Pana, D., Craven, J. & Bertrand, E. Three-dimensional resistivity structure of Southern Alberta, Canada: implications for Precambrian tectonics. Geophys. J. Int. 197, 838–859 (2014).

Priestley, K. & Tilmann, F. Relationship between the upper mantle high velocity seismic lid and the continental lithosphere. Lithos 109, 112–124 (2009).

Fischer, K. M. et al. A comparison of oceanic and continental mantle lithosphere. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 309, 106600 (2020).

Tharimena, S., Rychert, C., Harmon, N. & White, P. Imaging Pacific lithosphere seismic discontinuities—insights from SS precursor modeling. J. Geophys Res Solid Earth 122, 2131–2152 (2017).

Fischer, K. M., Ford, H. A., Abt, D. L. & Rychert, C. A. The lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 38, 551–575 (2010).

Griffin, W. L. et al. The origin and evolution of Archean lithospheric mantle. Precambrian Res 127, 19–41 (2003).

Snyder, D. B., Humphreys, E. & Pearson, D. G. Construction and destruction of some North American cratons. Tectonophysics 694, 464–485 (2017).

Rychert, C. A., Rondenay, S. & Fischer, K. M. P-to-S and S-to-P imaging of a sharp lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary beneath eastern North America. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 112, 1–21 (2007).

Shragge, J., Bostock, M. G., Bank, C. G. & Ellis, R. M. Integrated teleseismic studies of the southern Alberta upper mantle. Can. J. Earth Sci. 39, 399–411 (2002).

Gu, Y. J., Chen, Y., Dokht, R. M. H. & Wang, R. Precambrian tectonic discontinuities in Western Laurentia: broadband seismological perspectives on the Snowbird and Great Falls tectonic zones. Tectonics 37, 1411–1434 (2018).

Mueller, P. A., Heatherington, A. L., Kelly, D. M., Wooden, J. L. & Mogk, D. W. Paleoproterozoic crust within the Great Falls tectonic zone: implications for the assembly of southern Laurentia. Geology 30, 127–130 (2002).

Ross, G. M. Evolution of Precambrian continental lithosphere in Western Canada: results from Lithoprobe studies in Alberta and beyond. Can. J. Earth Sci. 39, 413–437 (2002).

Currie, C. A. & Beaumont, C. Are diamond-bearing Cretaceous kimberlites related to low-angle subduction beneath western North America?. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 303, 59–70 (2011).

Kjarsgaard, B. A., Heaman, L. M., Sarkar, C. & Pearson, D. G. The North America mid-Cretaceous kimberlite corridor: Wet, edge-driven decompression melting of an OIB-type deep mantle source. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 18, 1580–1593 (2017).

Hardebol, N. J., Pysklywec, R. N. & Stephenson, R. Small-scale convection at a continental back-arc to craton transition: Application to the southern Canadian Cordillera. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 117, 1–18 (2012).

Johnston, S. T. The Great Alaskan Terrane Wreck: reconciliation of paleomagnetic and geological data in the Northern Cordillera. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 193, 259–272 (2001).

Zhang, W., Johnston, S. T. & Currie, C. A. Numerical models of Cretaceous continental collision and slab breakoff dynamics in Western Canada. Spec. Pap. Geol. Soc. Am. 552, 97–112 (2021).

Yuan, H., French, S., Cupillard, P. & Romanowicz, B. Lithospheric expression of geological units in central and eastern North America from full waveform tomography. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 402, 176–186 (2014).

Schaeffer, A. J. & Lebedev, S. Global shear speed structure of the upper mantle and transition zone. Geophys. J. Int. 194, 417–449 (2013).

Steinberger, B. & Becker, T. W. A comparison of lithospheric thickness models. Tectonophysics 746, 325–338 (2016).

Rippe, D., Unsworth, M. J. & Currie, C. A. Magnetotelluric constraints on the fluid content in the upper mantle beneath the southern Canadian Cordillera: Implications for rheology. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 118, 5601–5624 (2013).

King, S. D. Archean cratons and mantle dynamics. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 234, 1–14 (2005).

Lowe, C. & Ranalli, G. Density, temperature, and rheological models for the southeastern Canadian Cordillera: implications for its geodynamic evolution. Can. J. Earth Sci. 30, 77–93 (1993).

Currie, C. A. & van Wijk, J. How craton margins are preserved: insights from geodynamic models. J. Geodynamics 100, 144–158 (2016).

Yuan, H., Romanowicz, B., Fischer, K. M. & Abt, D. 3-D shear wave radially and azimuthally anisotropic velocity model of the North American upper mantle. Geophys. J. Int. 184, 1237–1260 (2011).

Conrad, C. P., Lithgow-Bertelloni, C. & Louden, K. E. Iceland, the Farallon slab, and dynamic topography of the North Atlantic. Geology 32, 177–180 (2004).

Mallyon, D. The evolution of craton margin geometry through time. M.Sc. thesis, University of Alberta (2017).

Silver, P. G. & Holtz, W. E. The mantle flow field beneath Western North America. Science 295, 1054–1057 (2002).

Kumar, P., Yuan, X., Kind, R. & Ni, J. Imaging the colliding Indian and Asian lithospheric plates beneath Tibet. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 111, 1–11 (2006).

Cook, F. A., Van Der Velden, A. J., Hall, K. W. & Roberts, B. J. Frozen subduction in Canada’s Northwest Territories: lithoprobe deep lithospheric reflection profiling of the western Canadian Shield. Tectonics 18, 1–24 (1999).

Czas, J., Pearson, D. G., Stachel, T., Kjarsgaard, B. A. & Read, G. H. A Palaeoproterozoic diamond-bearing lithospheric mantle root beneath the Archean Sask Craton, Canada. Lithos 356, 357 (2020).

Farra, V. & Vinnik, L. Upper mantle stratification by P and S receiver functions. Geophys. J. Int. 141, 699–712 (2000).

Yuan, X., Kind, R., Li, X. & Wang, R. The S receiver functions: synthetics and data example. Geophys J. Int 165, 555–564 (2006).

Rondenay, S. Upper mantle imaging with array recordings of converted and scattered teleseismic waves. Surv. Geophys. 30, 377–405 (2009).

Natural Resources Canada. Canadian National Seismograph Network. Natural Resources Canada, https://doi.org/10.7914/SN/CN (1975).

IRIS Transportable Array. USArray Transportable Array. International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks, https://doi.org/10.7914/SN/TA (2003).

Hopper, E., Ford, H. A., Fischer, K. M., Lekic, V. & Fouch, M. J. The lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary and the tectonic and magmatic history of the northwestern United States. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 402, 69–81 (2014).

Wilson, D. C., Angus, D. A., Ni, J. F. & Grand, S. P. Constraints on the interpretation of S-to-P receiver functions. Geophys. J. Int 165, 969–980 (2006).

Bostock, M. G. Mantle stratigraphy and evolution of the Slave province. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 103, 21183–21200 (1998).

Kind, R., Yuan, X. & Kumar, P. Seismic receiver functions and the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary. Tectonophysics 536–537, 25–43 (2012).

Lekić, V. & Fischer, K. M. Contrasting lithospheric signatures across the western United States revealed by Sp receiver functions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 402, 90–98 (2014).

Ammon, C. J. The isolation of receiver effects from teleseismic P waveforms. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 81, 2504–2510 (1991).

Owens, T. J. & Taylor, S. R. Seismic evidence for an ancient rift beneath the Cumberland Plateau, Tennessee: A detailed analysis of broadband teleseismic P waveforms. J. Geophys. Res. 89, 7783–7795 (1984).

Saygin, E. Seismic receiver and noise correlation based studies in Australia, Ph.D. thesis, The Australian National University (2007).

Gu, Y. J. & Dziewonski, A. M. Global variability of transition zone thickness. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 107, 2–17 (2002).

Abt, D. L. et al. North American lithospheric discontinuity structure imaged by Ps and Sp receiver functions. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 115, 1–24 (2010).

Huang, S., Johnston, S. T., and Yu, G. J. Dual layered mantle lithosphere beneath southeastern Canadian Cordillera, https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.3534843.v1 (2025).

National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). ETOPO Global Relief Model. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/etopo-global-relief-model (2020).

Dziewonski, A. M., Chou, T. A. & Woodhouse, J. H. Determination of earthquake source parameters from waveform data for studies of global and regional seismicity. J. Geophys. Res. 86, 2825–2852 (1981).

Canadian Geodetic Survey. Canada—Gravity Data Compilation. https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/5a4e46fe-3e52-57ce-9335-832b5e79fecc (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank the host families of the CRANE seismic stations and the Global Seismology Group at the University of Alberta for their long-term field support. Y.J.G. and S.T.J. acknowledge support from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). Special thanks are extended to the M_Map project and the Generic Mapping Tools (GMT) team for their assistance in figure preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.S. and Y.J.G. performed the S receiver function computations and interpretations. S.T.J. provided geological background and contributed to the ribbon continent hypothesis. H.S., Y.J.G. and S.T.J. contributed equally to the writing and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, S., Gu, Y.J. & Johnston, S.T. Dual-layered mantle lithosphere beneath southeastern Canadian Cordillera. Nat Commun 16, 10441 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65437-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65437-0