Abstract

Uni-traveling-carrier photodiodes (UTC-PDs), which utilize only electrons as the active carriers, have become indispensable in high-speed optoelectronics due to their unique capabilities, such as high saturation power and broad bandwidth. However, extending the operating wavelengths into the visible region for wider applications is challenging due to the lack of suitable wide-bandgap III-V semiconductor combinations with the necessary band alignment and lattice matching. Here, we show that a UTC-PD based on a van der Waals heterojunction composed of a 2D transition metal dichalcogenide, molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), as a photoabsorption layer and a gallium nitride (GaN) film as a carrier collection layer, offers a solution to this challenge. The fast vertical carrier transport across the heterointerface is enabled by the direct epitaxial growth of a MoS2 layer on a GaN film. Our device demonstrates a frequency response in the several-GHz range with a quantum efficiency on the order of 1% throughout the entire visible spectrum, highlighting the promise for high-speed visible optoelectronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wide-bandgap semiconductors offer intrinsically favorable electronic properties such as high-power operation, high breakdown voltage, and high-temperature stability1,2. In particular, gallium nitride (GaN) has attracted attention owing to its high electron mobility, large electron saturation velocity3,4. GaN-based transistors have already become key elements in high-frequency electronic devices and wireless communications5,6. It is thus natural to anticipate that GaN-based photodiodes can exhibit excellent high-speed high-power characteristics in the visible wavelength range. Such high-speed wide-bandgap photodiodes can become key components in emerging visible-light technologies, since visible light offers higher directivity, lower absorption in water, and higher spatial resolution compared to near-infrared light. Applications include intersatellite communication7, visible-light communication (Li-Fi), particularly for underwater communication8,9, and high-resolution distance sensing technologies such as the Light Detection And Ranging (LiDAR) and Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)10,11.

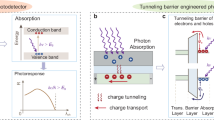

Uni-traveling carrier photodiodes (UTC-PDs)12,13 are one of the most successful examples of high-speed photonic devices in the telecommunication industry. They utilize the type-II band-alignment of the photoabsorption layer and diffusion block layer, which allows only electrons to transit in the carrier collection layer, to maximize response bandwidth and suppress space-charge saturation14. Adapting this concept to the visible range is nonetheless challenging, as it requires semiconductor combinations with specific band alignment and good lattice matching15, which, to our knowledge, have not yet been realized for GaN-based materials. Moreover, InGaN ternary alloys need to be inserted to shift the absorption edge of GaN (360 nm, corresponding to the bandgap ~ 3.4 eV) to the visible range. The InGaN/GaN quantum-well structure, however, reduces bandwidth due to slow carrier escape dynamics, resulting in the bandwidth typically in several hundred MHz to a few GHz16,17.

Recent advances have shown that two-dimensional (2D) transition metal dichalcogenides, such as molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), offer unique electrical and photonic properties. The combination of MoS2 with GaN is highly promising for high-performance photoabsorption layers, owing to the material system’s small lattice mismatch18,19,20, type-II band alignment21,22,23, and strong light-matter interaction in the visible region24,25,26. However, several groups have explored MoS2/GaN heterojunction photodetectors27,28,29,30,31, finding relatively slow responses on the order of microseconds or longer32,33,34,35. Such slow responses might be attributed to the imperfect interface of the heterojunction34. Although the intrinsic speed capabilities of MoS2/GaN interfaces remain unclear, we note that the ultrafast (less than 100 fs) carrier transport across heterointerfaces of 2D materials has been reported36,37, suggesting the intrinsic speed capabilities of the MoS2/GaN system have yet to be fully realized.

In this work, we report the successful realization of a UTC-PD based on a MoS2/GaN van der Waals heterojunction, which exhibits frequency response exceeding several GHz for visible light. Here, a few-layer MoS2 absorption layer is epitaxially grown directly on a GaN film using metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD), as opposed to the stamp transfer method. The demonstrated response of our device is currently constrained by an RC limit rather than fundamental carrier transport limits, suggesting that further structural optimization can push the bandwidth to tens of GHz or higher.

Results

Formation of MoS2/GaN Type-II heterojunction

The structure and operation principle of the MoS2/GaN UTC-PD developed in this study is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1a. The device is composed of an anode electrode, an absorption layer of MoS2, an i-GaN carrier collection layer, an n-GaN contact layer, and a cathode electrode. Incident photons absorbed within the MoS2 layer generate electron-hole pairs. The holes rapidly diffuse to the anode electrode adjacent to the MoS2 layer, whereas the electrons traverse the type-II aligned conduction band interface into the i-GaN layer. Subsequently, the electrons alone travel through the externally biased i-GaN layer and eventually reach the cathode through the n-GaN contact layer. Similar to standard UTC-PDs, high-speed operation is anticipated because of the smaller effective mass and the larger saturation velocity of electrons (~ 3 × 107 cm/s) than those of holes ( ~ 0.6 × 107 cm/s)38.

a Band structure of a MoS2/GaN UTC-PD. Here, \({E}_{g}^{{{{{\rm{MoS}}}}}_{2}}\) and \({E}_{g}^{{{{\rm{GaN}}}}}\) represent the bandgap energies of MoS2 and GaN, respectively, and EF denotes the Fermi energy. b Raman spectra of the MoS2layer grown on a GaN/sapphire substrate. The inset shows the details of the Raman peaks due to the MoS2 layer. c High resolution high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) cross-sectional scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image of MoS2/GaN heterojunction. The MoS2 film consists of 2 to 4 layers, being consistent with the result of the Raman spectroscopy. d Absorption spectrum of the MoS2/GaN heterostructure measured by a spectrophotometer. The left axis indicates absorbance, whereas the right axis shows absorption ratio. At wavelengths below 380 nm, absorption predominantly originates from the GaN layer. For the reference, the inset graph shows the absorption spectrum of the bare MoS2 layer directly grown on the sapphire substrate.

To achieve optimal interface conditions, we employed epitaxial growth of the MoS2 layers directly onto a GaN film on a c-plane sapphire substrate using metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD). More detailed information on the growth conditions is described in the Method section.

Raman spectroscopy analysis reveals a frequency difference Δω of 22 cm−1 between the \({{{\mathit{E}}}}_{2g}^{1}\) and A1g peaks (Fig. 1b), indicating that the MoS2 layers consist of bilayer or trilayer39. The atomic alignment of MoS2 layers on GaN is confirmed by cross-sectional high-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM), shown in Fig. 1c. Remarkably, the MOCVD-deposited MoS2 layers are epitaxially grown on the GaN film, likely due to the small lattice mismatch (0.8%) between MoS2 and GaN crystals18. The absence of unintended interfacial layers, such as native oxide, is also evidenced by the small discrepancy between measured and theoretical interlayer atomic spacing (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 1d shows the photoabsorption properties of the MoS2/GaN heterostructure. Absorption peaks are attributed to the excitonic peaks A, B, and C of the bare MoS2 absorption40,41 (inset in Fig. 1d).

In order to examine the band alignment of the MoS2/GaN van der Waals heterostructure, Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KPFM) measurements were conducted. This technique is capable of probing the surface potential of materials, making it a widely used method for determining the band offsets in heterostructures involving 2D materials42,43,44. Figure 2a shows the mapping image of the MoS2 on GaN/sapphire substrate, showing change in surface potential between MoS2 and GaN, and a line-scan of the surface potential along the indicated line in this image is reported in Fig. 2b. The results indicate the type-II band alignment of the conduction band and the offset ΔEc of 0.26 eV, as shown in Fig. 2c, which is consistent with previous reports22,23,45, thereby verifying that MoS2 layers effectively function as the active absorption layer for UTC-PD applications.

a Kelvin Probe Force Microscope (KPFM) mapping image of MoS2 on GaN/sapphire substrate, showing change in surface potential between MoS2 and GaN. b Plot of surface potential difference across MoS2/GaN interface along the line as indicated in (a). c Schematic of the band alignment of the MoS2/GaN van der Waals heterojunction, where Ec, Ev, EF, and ΔEc denote the conduction band energy, the valence band energy, the Fermi energy, and the conduction band offset between MoS2 and GaN, respectively.

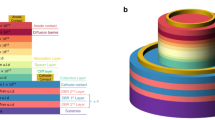

Device fabrication

Figure 3a provides a three-dimensional image of the fabricated device, whose photosensitive area is 60 μm in diameter. The device is designed to operate with illumination from the substrate side, as indicated in Fig. 3b. Photolithography and reactive ion etching (RIE) processes are utilized to form the mesa pattern of the device. The stacking structure comprises an n-GaN contact layer, an i-GaN carrier collection layer with a thickness of 0.3 μm and the carrier density ~ 1016 cm−3, MoS2 photoabsorption layers. A passivation layer of SiO2 is deposited around the mesa structure. Subsequently, Cr/Au is deposited as the anode electrode, and Ti/Al/Ti/Au is deposited as the cathode electrode using sputtering techniques. Finally, Ti/Pt/Au is deposited as the pad electrode. The device exhibits high stability due to the MoS2 being encapsulated by the anode metal and the SiO2 passivation layer, which minimizes susceptibility to atmospheric moisture and oxygen, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7.

a Three-dimensional image of the fabricated device acquired using a laser microscope. b Cross-sectional schematic image. The blue arrow illustrates backside illumination in our characterization. The device structure consists of three main layers: an n-GaN layer (thickness: 3.6 μm, carrier density: 4.22 × 1019 cm−3), an i-GaN layer (thickness: 0.3 μm, carrier density: 1015 ~ 1016 cm−3), and a MoS2 layer (2–4 layers, sheet carrier density: 8.5 × 1013 cm−2). c I–V characteristics of the device. The solid lines represent measurements under dark conditions, while the dotted lines correspond to measurements under illumination with a 405 nm laser diode at a power density of 75 W/cm2.

To evaluate the basic electrical properties and demonstrate the rectifying behavior of the fabricated device, we measured the I–V characteristics shown in Figure 3c. The solid lines represent measurements under dark conditions, while the dotted lines correspond to measurements under illumination with a 405 nm laser diode at a power density of 75 W/cm2. I–V characteristics of the device measured under dark conditions clearly exhibit diode-like rectifying behavior. The summary of Hall effect measurements, sheet resistivities, mobilities, and carrier densities of MoS2 and GaN layers, are found in Supplementary Table 1. Notably, the Hall measurements of the MoS2 layers indicate n-type conduction, which may be attributed to the sulfur atom vacancies46,47. Transmission line model (TLM) measurements (described in Supplementary Fig. 3) confirms the ohmic contact between the anode electrode and MoS2 layers, indicating the rectification originates from the MoS2/GaN heterojunction rather than Schottky barrier at the contact. The physics behind the rectifying behavior of the device is discussed in Supplementary Section 3, where the two factors are considered: the crystal-momentum mismatch between the conduction electrons in MoS2 and GaN48, and the polarization charge of GaN49.

Experimental Verification

We evaluate the large-signal response of the device by measuring the time-domain photocurrent signal when illuminating the light with a wavelength of 445 nm and a pulse width of 100 μs. In Fig. 4a, the black line represents the pulse waveform of the incident light, which is taken by a Si-PIN photodiode (Hamamatsu Photonics; S9055), as a reference, while the blue line represents the photocurrent signal of the device. The photocurrent signal closely follows the pulse waveform of the incident light, where the rise and fall times are on the order of microseconds, which are limited by the time-response of the light source itself. Note that the slight distortions of the baseline and the top of the pulse in the photocurrent signal are mainly due to the peripheral circuits, as discussed in Section 6 of Supplementary Information. The photocurrent response is thus three to six orders of magnitude faster than previously reported MoS2/GaN photodetectors22,29,34,50,51. Such improvements can be attributed to the high-quality epitaxial MoS2/GaN van der Waals heterointerface, which effectively reduces carrier trapping effects at the heterojunction. Figure 4b shows the dependence of the photocurrent signal on the incident light power density. Based on the peak photocurrent values in Fig. 4b, we examine the linearity between the optical input power and the output current. Figure 4c presents the peak photocurrents as a function of the optical input power, showing excellent linearity between them and no saturation up to the maximum optical input power of approximately 100 W/cm2.

a Time dependence of the photocurrent signal of the device. Photocurrent signal of the device is shown as the blue line, while the pulse waveform signal of the incident light is shown as the black line. Here, the latter signal is taken by a Si-PIN photodiode (Hamamatsu Photonics; S9055) as a reference. The rise and fall times of the incident light are on the order of microseconds, which closely follows the pulse waveform of the incident light. b Dependence of the photocurrent on the incident light power density. c Peak photocurrents in (b) as a function of the optical input power.

To investigate the characteristics of the device in much higher frequency regions, we examine the frequency response of the device with intensity-modulated light (Fig. 5a). Figure 5b demonstrates that the MoS2/GaN PD achieves a − 3 dB bandwidth of approximately 5 GHz at a reverse bias of 4 V. This response is well explained by an RC low-pass filter model, where R corresponds to the external impedance of Rload = 50 Ω, and C corresponds to the i-GaN depletion capacitance of Cj = 0.8 pF. The equivalent circuit of the photodiode system at a reverse bias of 4 V is presented in Section 3 of Supplementary Information. Here, the device capacitance Cj is identified by capacitance-voltage (C–V) measurement as described in Supplementary Fig. 4.

a Experimental setup for measuring the frequency response of the fabricated MoS2/GaN UTC-PD. A single-mode laser diode (465 nm) is intensity-modulated via a Mach--Zehnder interferometer (see Methods). An AC photocurrent signal is fed into a vector network analyzer through a transmission line radio frequency (RF) probe and a wideband amplifier matched at 50 Ω. b Frequency response characteristics of the device at a wavelength of 465 nm with a reverse bias of 4 V, normalized (norm.) by low-frequency sensitivity. The response is calibrated (cal.) using a reference GaAs PIN-photodiode (flat up to 20 GHz; see Supplementary Fig. 9 for raw data and the noise floor of the measurement system). The gray line indicates the noise floor with the laser diode turned off. The calibrated signal (light blue line) contains large fluctuations both in low and high frequencies due to the 1/f noise and the crosstalk of the radiation from the driving signal. See supplementary Section 8 for extended low-frequency data. Smoothing is applied (blue line) to see the salient feature of the frequency response. A simple RC low-pass filter response (black line) is also shown.

The cutoff frequency of 5 GHz is thus neither due to carrier escape delay in the MoS2 layer nor carrier transit time in the i-GaN layer. We can anticipate a faster response by minimizing the capacitance by, for instance, optimizing the thickness of the electron collection layer, and/or miniaturizing the size of the photosensitive area, as discussed in Section 12 of Supplementary Information.

Next, we evaluate the dependence of sensitivity and frequency response on wavelength and reverse bias voltage. Figure 6a–d show the results for the wavelengths of the light at 405 nm, 465 nm, 530 nm, and 620 nm, respectively. For measurements at 405 nm, 530 nm, and 620 nm, the intensity modulation is performed by direct modulation of the laser diodes rather than by using the separate phase modulator described in Fig. 5a. Even after smoothing, nonignorable noise remains above 2 GHz (shaded region) for those results, which is mainly due to the larger electrical crosstalk caused by the direct modulation circuit. The broad sensitivity across the visible wavelength suggests that electron-hole pair generation occurs in the MoS2 layer rather than GaN layers. Thus, the photocurrent signal corresponds to electron transit in the i-GaN layer, in accordance with the UTC-PD model shown in Fig. 1a. Highest quantum efficiency is obtained at 405 nm, reaching approximately 1.5%, while the efficiencies are lower around 0.5% for other wavelengths (465 nm, 530 nm, and 620 nm), which is consistent with the photoabsorption spectrum (Fig. 1d). Additionally, Supplementary Fig. 6 provides further details on other photoresponse characteristics, such as responsivity, detectivity (D*), and noise equivalent power (NEP).

Wavelength dependence of the frequency response, measured using laser diodes (LD) at 405 nm (a), 465 nm (b), 530 nm (c), and 620 nm (d), with power densities of 50 W/cm2, 10 W/cm2, 70 W/cm2, and 70 W/cm2. Each response is represented in terms of the quantum efficiency (Q.E.) and the responsivity calibrated by a commercially available Si PIN-PD, whose quantum efficiency is specified by the manufacturer. We only show the results with smoothing to eliminate the low and high-frequency noise. In 6a, 6c, 6d, the frequency region above 2 GHz is grayed-out to indicate the signal is dominated by crosstalk. The lines in each figure correspond to different reverse bias voltage applied to the device. e Internal quantum efficiencies for varying wavelengths and reverse biases. The internal quantum efficiency is defined as the quantum efficiency (depicted in 6a-6d) divided by the absorption (depicted in Fig. 1d). f Band structure of bilayer MoS2 (2H phase) calculated using density functional theory (DFT). The energy level of the B- and C-exciton transitions indicates that photogenerated electron-hole pairs occupy different crystal momentum states.

Figure 6e shows the internal quantum efficiencies for varying wavelengths and reverse biases. Here, the internal quantum efficiency is defined as the quantum efficiency divided by the absorption depicted in Fig. 1d, expressing what portion of electrons generated in the MoS2 layer turns into the photocurrent. The fabricated devices exhibit relatively low internal quantum efficiencies, ranging approximately from 1% to 5%, as shown in Fig. 6e. Note that, as the reverse bias increases, the internal quantum efficiency also increases for all wavelengths. Furthermore, the reverse bias dependence of the internal quantum efficiency is more significant for longer wavelengths.

Discussion

The internal quantum efficiency of the fabricated devices is significantly lower than unity that the conventional PIN photodiodes would attain, indicating that some of the photo-generated carriers do not contribute to the photocurrent. Several observations are consistent with the low internal quantum efficiency arising primarily from the crystal-momentum mismatch between electrons in MoS2 and GaN. A fuller discussion is provided in Section 10 of the Supplementary Information; we summarize a brief overview here. The band struture of bilayer MoS2 (2H phase), calculated using density functional theory (DFT), is shown in Fig. 6f. We focus on the C-exciton transition ( ~ 3 eV) lies on the Γ-point and the B-exciton transition ( ~ 2 eV) on the K-point (purple and red arrows in Fig. 6f) whose transitions can be excited by 405 nm and 620 nm illumination, respectively. For the B-exciton transition, photo-excited electrons in the K-point of MoS2 cannot efficiently transfer to GaN (whose conduction minimum lies at Γ) because of the crystal-momentum mismatch, so they eventually recombine within MoS2. Under reverse bias, thermally assisted tunneling enables carrier transfer, thereby improving internal quantum efficiencies. For the C-exciton transition (405 nm), on the other hand, part of photo-excited elctrons around the Γ-point of MoS2 can directly transfer to GaN before relaxing to the K valley, leading to a comparatively higher internal quantum efficiency. Trap-assisted tunneling might also be a carrier escape path. However, we infer that such a slow process would not significantly contribute to the observed wideband photocurrent response. Taken together, these considerations indicate that momentum-space matching is an important design guideline for 2D-material/GaN photodetectors, which has received little attention in previous studies.

In conclusion, we successfully fabricated a UTC-PD based on a MoS2/GaN van der Waals heterojunction, where the type-II aligned MoS2 layer selectively inject photoelectrons to the i-GaN collection layer. The fabricated UTC-PD worked at entire visible wavelengths with the quantum efficiency on the order of 1%. Our device exhibits an excellent frequency response, which corresponds to three to six orders of magnitude faster than those reported in earlier studies, thanks to the high-quality epitaxial van der Waals heterointerface between MoS2/GaN. Supplementary Table 2 provides a comparison between our device and previously reported 2D materials/GaN photodetectors as well as other high-speed photodetectors.

Through this study, we proved the feasibility of UTC-PDs for visible light by incorporating a 2D semiconductor layer as a photoabsorption layer and a wide-bandgap GaN film as an electron collection layer. Further material exploration and structural optimization are expected to improve the device performance and provide additional solutions in the field of high-speed visible optoelectronics.

Methods

Growth of MoS2

The MoS2 layers were directly grown onto a GaN film on a 4-inch c-plane sapphire substrate using an MOCVD system (Oxford Instruments; Nanofab 1000 Agile). The precursors used for the MoS2 growth are molybdenum hexacarbonyl, Mo(CO)6 (Japan Advanced Chemicals) for metal, and hydrogen sulfide, H2S for chalcogen. MoS2 was grown on a 4-inch GaN/sapphire wafer using the following process. Initially, the sample was transferred from the load lock chamber to the process chamber of the MOCVD system, and heated from room temperature to 800 °C under vacuum conditions (2.8 × 10−6 Torr). Next, to sulfurize the GaN surface, we treated it with H2S at a flow rate of 20 sccm for 1 minute at 800 °C. Following this, the main deposition process was conducted with Mo(CO)6 at a flow rate of 5 sccm and H2S at 20 sccm, also at 800 °C for 1 minute. In this step, the precursor bottle and piping system were heated to 60 °C to increase the vapor pressure of Mo(CO)6, with Ar used as the carrier gas. For the post-deposition process, cooling was performed at first under an H2S atmosphere at 20 sccm for 5 minutes, followed by cooling under an Ar atmosphere at 100 sccm for 10 minutes, which brings the stage temperature down to 650 °C. Finally, the sample was transferred back to the load lock chamber, cooled to room temperature under vacuum, and then removed. The MoS2 grown on the 4-inch GaN/sapphire wafer exhibits an in-plane distribution of 2 to 4 layers, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

STEM analysis

To obtain atomically resolved information on the MoS2/GaN van der Waals heterojunction, a STEM analysis has been performed as shown in Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1, and Supplementary Fig. 2. The sample was prepared by thinning using a micro-sampling method with a Focused Ion Beam (FIB). The observations were made along the a-plane direction [11\(\bar{2}0\)] of GaN using STEM (JEOL; JEM-ARM200F).

Fabrication of the device

Photolithography and reactive ion etching (RIE) processes were used to make the mesa patterns of the device. The photosensitive area is 60 μm in diameter. The anode electrode is composed of Cr/Au (10 nm/200 nm), while the cathode consists of Ti/Al/Ti/Au (10 nm/300 nm/150 nm/50 nm) deposited by sputtering.

Experimental setup for the frequency response measurement

The device’s photoelectric properties were characterized using three distinct methods: high-frequency response analysis, wavelength-dependent measurements, and large-signal pulsed measurements. For the high-frequency response analysis (Fig. 5), we generated phase-synchronous intensity-modulated light at 465 nm. The output of a single-mode laser diode (NICHIA; NDB4916) was guided into a Mach-Zehnder interferometer (MZI) constructed with free-space beam splitters. A waveguide phase modulator (AdvR; WPM-K0450) in one arm of the MZI was driven by a vector network analyzer (VNA, ROHDE&SCHWARZ; ZNA67). The MZI was actively stabilized using a phase-lock loop that controlled the path length via a piezo-actuated mirror, where the error signal for this loop was derived from the optical intensity at the interferometer’s unused output port. An AC photocurrent signal is amplified by a 50 Ω-matched wideband amplifier (Atlanta Micro Inc.; AM1102) and fed into the VNA through a transmission line probe (TECHNOPROBE; TP26-GSG-350-A). Non-flat frequency response of the measurement system is calibrated by a commercially available GaAs PIN-photodiode (TRUMPF; ULMPIN-25-TT). A wavelength dependence of the frequency response, measured using directly-modulated LDs at 405 nm (NICHIA; NDV4316), 465 nm (NICHIA; NDB4916), 530 nm (NICHIA; NDG4716), and 620 nm (Hangzhou BrandNew Technology; custom-made), as shown in Fig. 6. Q.E. is calibrated by a commercially available Si PIN-photodiode (Hamamatsu Photonics; S9055). The launch power of the laser and the insertion loss within the setup are primarily attributed to coupling losses into the optical fiber and insertion losses from components such as beam splitters, as shown in Fig. 5a. The laser power was measured using a power meter (Thorlabs; S120C) placed immediately before the device, ensuring that any power loss due to branching or other components in the setup does not affect the evaluation of the photoresponse and responsivity of the device. The pulsed light, as shown in Fig. 4, was generated by directly modulating a 445 nm LD to a pulse width of 100 μs using a variable pulse width driver (PicoLAS GmbH; LDP-V 03-100).

DFT calculations

Band structure of bilayer MoS2 (2H phase), as shown in Fig. 6f, was calculated using density functional theory (DFT). All calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP). The local density approximation of Ceperley and Alder (CA) was used for the exchange-correlation functional. The projector augmented-wave (PAW) potentials were used to describe the core-valence interaction. A plane-wave energy cutoff was set to 600 eV and an energy convergence criteria of 10−7 eV was used. The atomic positions were relaxed until the residual forces on all atoms became less than 5 × 10−3 eV/Å. For the initial structure of the bilayer MoS2, we adopted a- and b-axes lattice constants and atomic positions of the bulk 2H-MoS2, and the vacuum layer of about 25 Å. The atomic positions of bilayer MoS2 model were relaxed, while the cell parameters were fixed. For the K-point sampling of Brillouin-zone integrals, we used a 8 × 8 × 2 for the bulk 2H-MoS2, and a 8 × 8 × 1 for the bilayer MoS2.

Characterizations

The 3D image of the device (Fig. 3a) was acquired using a laser microscope (Keyence; VK-X3000). The Raman spectra (Fig. 1b) were measured with a Raman spectrometer (Renishaw; inVia reflex) using 532 nm excitation. The absorption spectra (Fig. 1d) were measured by a spectrophotometer (Hitachi High-Tech; U-4100). The atomic resolution cross-sectional STEM images (Fig. 1c) were measured using STEM (JEOL; JEM-ARM200F). The I–V characteristics of the device (Fig. 3c) measured using a device analyzer (Keysight; B1505A). The surface potential of the materials was measured using a KPFM (SHIMADZU; SPM-9700HT).

Data availability

The Source Data underlying the figures of this study are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29858483. All raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Iannaccone, G., Sbrana, C., Morelli, I. & Strangio, S. Power electronics based on wide-bandgap semiconductors: Opportunities and challenges. IEEE access 9, 139446–139456 (2021).

Baliga, B. J. Gallium nitride devices for power electronic applications. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 28, 074011 (2013).

Sun, Y. et al. Review of the recent progress on GaN-based vertical power Schottky Barrier Diodes (SBDs), Electronics 8, 575 (2019).

Carey, P. H. et al. Extreme temperature operation of ultra-wide bandgap AlGaN high electron mobility transistors. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 32, 473–477 (2019).

Sun, R., Lai, J., Chen, W. & Zhang, B. GaN power integration for high frequency and high efficiency power applications: a review. IEEE Access 8, 15529–15542 (2020).

Lu, H. et al. A review of GaN RF devices and power amplifiers for 5G communication applications. Fundam. Res. 5, 315–331 (2025).

Amanor, D. N., Edmonson, W. W. & Afghah, F. Intersatellite Communication System Based on Visible Light. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 54, 2888–2899 (2018).

Qi, Z. et al. Full-duplex underwater wireless blue light communication. Opt. Express 31, 9330–9338 (2023).

Yu, T-C. et al. Visible light communication system technology review: devices, architectures, and applications, Crystals 11, 1098 (2021).

Mitchell, E. W. et al. Coherent laser ranging for precision imaging through flames. Optica 5, 988 (2018).

Xu, C. et al. Ultrathin visible-light OCT endomicroscopy for in vivo ultrahigh-resolution neuroimaging in deep brain. APL Photonics 9, 110804 (2024).

Ishibashi, T. et al. Uni-Traveling-Carrier Photodiodes, Ultrafast Electronics and Optoelectronics, Optica Publishing Group, UC3 (1997).

Ishibashi, T. & Ito, H. Uni-traveling-carrier photodiodes. J. Appl. Phys. 127, 031101 (2020).

Chen, Q., Zhang, X., Sharawi, M. S. & Kashyap, R. Advances in high-speed, high-power photodiodes: from fundamentals to applications, Appl. Sci. 14, 3410 (2024).

Piels, M. & Bowers, J. E. Si/Ge uni-traveling carrier photodetector. Opt. Express 20, 7488–7495 (2012).

Hu, F. et al. Si-substrate LEDs with multiple superlattice interlayers for beyond 24 Gbps visible light communication. Photonics Res. 9, 1581 (2021).

Xu, Z. et al. 15.26Gb/s Si-substrate GaN high-speed visible light photodetector with super-lattice structure. Opt. Express 31, 33064 (2023).

Liu, F. et al. Layered transition metal dichalcogenides: promising near-lattice-matched substrates for GaN growth. Appl. Phys. Lett. 113, 243107 (2018).

Yan, P. et al. Epitaxial growth and interfacial property of monolayer MoS2 on gallium nitride. RSC Adv. 8, 33193–33197 (2018).

Al Khalfioui, M. et al. Investigation of MoS2 growth on GaN/sapphire substrate using molecular beam epitaxy. J. Cryst. Growth 652, 128047 (2025).

Tangi, M. et al. Determination of band offsets at GaN/single-layer MoS2 heterojunction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 032104 (2016).

Moun, M., Kumar, M., Garg, M., Pathak, R. & Singh, R. Understanding of MoS2/GaN Heterojunction Diode and its Photodetection Properties. Sci. Rep. 8, 11799 (2018).

Li, B., Shao, Y. C. & Chang, K. A first-principles study of electronics structure and photocatalytic performance of GaN-MX2(M= Mo, W; X=S, Se) van der Waals heterostructures. Nanotechnology 30, 225702 (2019).

Mak, K. F. & Shan, J. Photonics and optoelectronics of 2D semiconductor transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Photonics 10, 216–226 (2016).

Taffelli, A. et al. MoS2 based photodetectors: a review. Appl. Sci. 11, 1154 (2021).

Jian, P. et al. Large-scale synthesis and exciton dynamics of monolayer MoS2 on differently doped GaN substrates. Nanophotonics 12, 4475–4484 (2023).

Moun, M., Singh, A. & Singh, J. Exploring conduction mechanism and photoresponse in P-GaN/n-MoS2 heterojunction diode. J. Appl. Phys. 127, 064501 (2020).

Jain, A., Singh, J., Sinha, R. & Gupta, G. D. Current transport and band alignment study of MoS2/GaN and MoS2/AlGaN heterointerfaces for broadband photodetection application. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2, 3186–3196 (2020).

Veeralingam, S. et al. High responsivity of zero-power-consumption ultraviolet photodetector using 2D-MoS2/i-GaN vertical heterojunction. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 12313–12323 (2023).

Janardhanam, V., Zummukhozol, M., Jyothi, I., Shim, K.-H. & Choi, C.-J. Self-powered MoS2/n-type GaN heterojunction photodetector with broad spectral response in ultraviolet-visible-near-infrared range. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 360, 114534 (2023).

Vashishtha, P. et al. CVD-grown monolayer MoS2 and GaN thin film heterostructure for a self-powered and bidirectional photodetector with an extended active spectrum. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 3868–3877 (2024).

Zhuo, R. et al. In-situ fabrication of PtSe2/GaN heterojunction for self-powered deep ultraviolet photodetector with ultrahigh current on/off ratio and detectivity. Nano Res. 12, 183–189 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Design and integration of a layered MoS2/GaN van der Waals heterostructure for wide spectral detection and enhanced photoresponse. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 47721–47728 (2020).

Kass, R. et al. Pulsed laser deposition for conformal growth of MoS2 on GaN nanorods for highly efficient self-powered photodetection. Nanotechnology 34, 485203 (2023).

Ye, L., Gan, X. & Schirhagl, R. Two-dimensional MoS2-based photodetectors. Sustainability 16, 10137 (2024).

Jin, C. et al. Ultrafast dynamics in van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 994–1003 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Ultrafast interlayer electron transfer in incommensurate transition metal dichalcogenide homo-bilayers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2207903 (2022).

Chen, S. & Wang, G. High-field properties of carrier transport in bulk wurtzite GaN: A Monte Carlo perspective. J. Appl. Phys. 103, 023703 (2008).

Lee, C. et al. Anomalous Lattice Vibrations of Single and Few-Layer MoS2. ACS Nano 4, 2695–2700 (2010).

Kozawa, D. et al. Photocarrier relaxation pathway in two-dimensional semiconducting transition metal dichalcogenides, Nat. Commun. 5, 4543 (2014).

Wang, L. et al. Slow cooling and efficient extraction of C-exciton hot carriers in MoS2 monolayer. Nat. Commun. 8, 13906 (2017).

Tosun, M. et al. MoS2 heterojunctions by thickness modulation. Sci. Rep. 5, 10990 (2015).

Giannazzo, F., Schiliró, E., Greco, G. & Roccaforte, F. Conductive atomic force microscopy of semiconducting transition metal dichalcogenides and heterostructures. Nanomaterials 10, 803 (2020).

Jiang, T. et al. Vertical Van Der Waals Epitaxy of p-MoxRe1−xS2 on GaN for Ultrahigh detectivity UV-vis-NIR photodetector. Adv. Opt. Mater. 12, 2301596 (2024).

Kang, J., Tongay, S., Zhou, J., Li, J. & Wu, J. Band offsets and heterostructures of two-dimensional semiconductors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 012111 (2013).

Liu, D., Guo, Y., Fang, L. & Robertson, J. Sulfur vacancies in monolayer MoS2 and its electrical contacts. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 183113 (2013).

Su, J., Li, N., Zhang, Y., Feng, L. & Liu, Z. Role of vacancies in tuning the electronic properties of Au-MoS2 contact. AIP Adv. 5, 077182 (2015).

Kümmell, T. et al. Carrier transfer across a 2D-3D semiconductor heterointerface: The role of momentum mismatch. Appl. Mater. Today 7, 23–28 (2017).

Li, W. et al. Rectification behavior of polarization effect induced type-II n-GaN/n-type β-Ga2O3 isotype heterojunction grown by metal organic vapor phase epitaxy. J. Appl. Phys. 127, 015302 (2020).

Wu, J.-B. et al. Monolithic integration of MoS2-based visible detectors and GaN-based UV detectors. Sci. Rep. 9, 4489 (2019).

Janardhanam, V., Zummukhozol, M., Jyothi, I., Shim, K. H. & Choi, C. J. Self-powered MoS2/n-type GaN heterojunction photodetector with broad spectral response in ultraviolet-visible-near-infrared range. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 360, 114523 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank T. Kishino for the GaN epitaxially growth on Sapphire substrate, Y. Nakagawa for the help with MoS2 growth, M. Sano, K. Omae, S. Nagahama, T. Mukai, and Y. Narukawa for the fruitful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K. and T.S. designed the UTC-PD based on a MoS2/GaN heterojunction. T.K. prepared and analyzed the MoS2 layers and fabricated the device. T.S. designed the experimental setup for the frequency response measurement. T.K. characterized the device. A.I. performed the DFT calculations. Y.O. assisted with device fabrication and electrical measurements. Y.K. provided helpful advice regarding the characterization of the GaN-based heterojunction. Y.I. provided helpful advice regarding the characterization of MoS2 properties. T.K., T.S., K.U., and H.O. wrote the paper. Y.K. and Y.I. reviewed and commented on the manuscript. H.O. organized all the efforts on this work. All authors contributed to the discussion concerning the experimental results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Stefan Koepfli and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kadowaki, T., Serikawa, T., Ichikawa, A. et al. Uni-traveling-carrier photodiode based on MoS2/GaN van der Waals heterojunction for high-speed visible-light detection. Nat Commun 16, 10471 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65483-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65483-8