Abstract

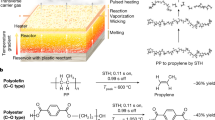

The accumulation of plastic waste poses a severe environmental issue, and efficient depolymerization of plastic is essential toward sustainable waste management and circularity. However, depolymerizing polyolefin plastic into monomer with high selectivity remains a challenge. Herein, inspired by the incandescent light bulb, we demonstrate a catalytic depolymerization strategy utilizing high-temperature transition metal filaments to convert polyolefin plastic to olefin monomer, with monomer selectivity reaching up to 65%. The electrified transition metal filaments, serving as localized heat sources, can reach a high temperature of up to 2300 °C, significantly promoting the generation of gaseous products. The reaction region with sharp temperature gradient restrains secondary transformations of monomer. Monomer selectivity is tunable by varying different high-melting-point metallic elements, and can be extended to bulk commodity alloy, such as stainless steel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plastic products are ubiquitously used to bring great convenience to modern society, but they also pose non-negligible environmental and health problems1,2,3. It is estimated that millions of tons of plastic waste enter the oceans every year, forming a massive plastic garbage belt that has a devastating impact on marine ecosystems4,5. In terrestrial ecosystems, plastic waste destroys soil structure, hinders plant growth, and affects the balance and stability of the entire ecosystem6. Moreover, plastic pollution may pose a potential threat to human health, as humans ingest microplastics entering the ecosystem through food and water1,7. The most dominant disposal methods for plastics are still landfills and incineration, which either cause direct pollution or have a high carbon footprint8,9,10,11. Recycling plastics through mechanical recovery avoids these problems, but the recycled plastics have compromised properties and are difficult to meet the demands of regular use12,13,14,15.

Chemical recycling of plastics, i.e., converting plastics into their monomers and then re-polymerizing the monomers, on the other hand, is an approach that offers reliable product properties16,17,18,19,20,21. Along this line, exciting advances have been reported, such as depolymerization of polyethylene terephthalate by enzymatic hydrolysis22,23,24 or biomimetic binuclear catalysts25 to obtain monomer, with a selectivity of nearly 100%. However, in the case of waste polyolefin plastics, such as polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP), the selectivity for obtaining monomer remains low. Since polyolefins are primarily composed of carbon–carbon (C–C) single bonds, their chemical structure lacks distinct catalytic active sites26,27,28. As a result, even with the use of catalysts, the selectivity for monomer formation from polyolefins remains highly limited18,29. Additionally, the C–C bond structure in polyolefins is quite stable and has a high bond energy, which means that at usual reaction temperatures, a sufficient reaction time is required to meet the energy demand of deep and effective depolymerization of polyolefins30,31. However, the reaction network of the depolymerization, i.e., pyrolysis process, grows exponentially with reaction time, increasing the formation of by-products and thereby reducing the selectivity for monomer32,33.

The conventional pyrolysis process is characterized by a slow heating rate, requiring a long duration to reach high temperatures. This property inevitably triggers numerous undesirable secondary reactions, resulting in low selectivity for the depolymerization of polyolefin plastics. In contrast, as an emerging electrified heating method, Joule heating features rapid heating and cooling rates, demonstrating the potential of improving the selectivity of plastic waste into valuable gaseous products, and even monomer, at moderate temperatures (600–800 °C)34,35,36. Specifically, Dong et al. used a porous carbon felt as the Joule heating substrate to depolymerize PP into propylene monomer with a high selectivity of 36% through spatiotemporal heating at a peak temperature of 600 °C34. It should be noted that temperature control is critical in polyolefin pyrolysis for product distribution. At low temperatures (<500 °C), long-chain scission and mild cross-linking dominate, producing high-molecular-weight tar and some char with low gas selectivity37,38. Between 500–800 °C, intensified thermal cracking increases tar and gas yields while reducing char28,39. Theoretically, at even higher temperatures with appropriate control, secondary tar cracking can promote gas formation, ultimately leading to near-complete gasification and potential olefin monomer recovery. However, few studies have addressed the high-temperature Joule-heating depolymerization of polyolefin plastic to produce gaseous products, especially olefin monomer.

Incandescent light bulb, as a common household appliance, produces light through Joule heating of a high-resistance metal filament, typically tungsten filament, raising its temperature to an incandescent state. The filament temperature, accompanied by light emission, can reach up to 2500 to 3000 °C, potentially providing a platform for high-temperature Joule-heating depolymerization of polyolefin plastic. Meanwhile, the natural temperature gradient of the light bulb and the potential catalytic effect of the metal filament substrate are expected to further modulate the selectivity of the olefin monomer. Here, we report a high-temperature catalytic strategy for selectively depolymerizing polyolefin plastic into gaseous olefin monomer. Drawing inspirations from the properties of light bulb, we use transition metal filaments to provide instantaneous high temperatures through the Joule heating effect while serving as in-situ catalysts for the depolymerization reaction. Taking PE as an example, an ethylene monomer selectivity of over 65% can be achieved after optimization. Transformation dynamics and mechanism analyses reveal the crucial role of high-temperature-induced heat transfer and mass transfer, as well as radical chemistry, in the reaction process.

Results

Design principle of the depolymerization strategy

Light bulb consists of structural units such as glass chamber, metal filament, and inert gas atmosphere (Fig. 1a). When the bulb is off, glass chamber, metal filament, and inert gas are all at room temperature. When a light bulb is turned on, the metal filament instantly (usually <1 μs) generates a temperature of 2500–3000 °C, which is the origin of its luminosity. The lighting process of the metal filament is an ultra-fast heat transfer process, allowing for a significant heating rate of the metal filament (>109 °C s–1). Meanwhile, the glass chamber remains at near room temperature, while the intervening inert gas creates a temperature field with a sharp temperature gradient. Based on the different temperatures of the metal filament, glass chamber, and inert gas, a multi-temperature zone is spontaneously formed inside the light bulb at the instant the bulb is turned on.

Inspired by the dual properties of ultra-fast heat transfer and multi-temperature zone of the light bulb, we combined these potential advantages into a reactor for the depolymerization of polyolefin plastics (Fig. 1b). The unique property of ultra-fast heat transfer can serve as a reaction environment capable of avoiding the undesired side reactions triggered by the traditionally slow heating process of polyolefin plastics. Besides, the multi-temperature-zone environment created by the bulb potentially provides favorable conditions for controlling and stopping secondary reactions in the depolymerization of polyolefin plastics. Further, we introduce a flowing inert gas (e.g., argon) to create a characteristic flow field opposite to the temperature, which in turn enables the transport and control between different temperature zones. Moreover, the metal filament can be potentially used as an in-situ catalyst to further modulate the depolymerization reaction. The polyolefin plastic is deposited on the surface of the metal filament prior to depolymerization to enable the rapid heating rate and allow the metal filament to catalyze the depolymerization reaction. By the advantages of ultra-fast heat transfer, multi-temperature control, and in-situ catalysis, we expect the light bulb-inspired high-temperature catalytic strategy depolymerizing the polyolefin plastic to monomer selectively.

Depolymerization of polyolefin plastic into monomer

In a proof-of-concept experiment, we chose tungsten filament, just the filament in the commercial light bulb, as the starting metal filament material for the depolymerization of polyolefin plastic. Among the numerous metal materials, tungsten is distinctive due to its highest melting point, which is also one of the most important reasons why tungsten is used as the filament material in the commercial light bulb40,41. The high melting point of the tungsten filament allows for the maximum possible tuning of the reaction temperature, thus modulating the monomer selectivity from depolymerization. The reaction temperature was mainly regulated by the variation of voltage input (Fig. 2a). The range of temperatures was set from ~900 °C to ~2300 °C, which is a fairly high temperature since high temperatures are more conducive to the depolymerization of plastics to gas products and are kinetically favorable37,42. Under the different voltage inputs, the monomer selectivity, i.e., ethylene selectivity, of a low-molecular-weight PE (LMWPE, Mw = 5.2 × 103 g mol–1, polydispersity Ð = 4.1) was investigated. At the voltage of 8 V, the ethylene selectivity of ~36% was obtained (Fig. 2a), while the selectivity was improved to ~48% with the increase of voltage to 12 V. However, with the further increase of voltage, the ethylene selectivity dropped rapidly, with the selectivity of ~29% at the voltage of 30 V. For the optimized voltage of 12 V (reaction temperature of ~1250 °C), approximately 48% of ethylene was detected (Fig. 2b), accompanied by the production of other light hydrocarbons (e.g., methane, ethane, propylene, and propane). Propylene was the second largest component with a selectivity of about 14%, while the C1–C3 alkanes accounted for about 12%.

a Operation temperature and ethylene selectivity of the depolymerization of low-molecular-weight polyethylene under different voltage inputs. b Representative gas product distribution measured by gas chromatography with flame ionization detection with a reaction temperature of ~1250 °C. The pale red rectangle is present only to guide the eye. c Olefin monomer selectivity of the depolymerization of different types of polyolefin plastics. d Comparison of melting points of different transition metals. The dashed line denotes the temperature at 1250 °C. e Product distribution and ethylene selectivity based on different transition metal elements.

To explore the universality of this method on other polyolefin plastics, the depolymerization of different molecular weights and different types of polyolefin plastics was also investigated (Fig. 2c). For high-molecular-weight PE (HMWPE), the monomer selectivity of 47% was achieved, which is similar to that of LMWPE. Moreover, despite differences in monomer composition, PP plastic was depolymerized to its monomer with a selectivity of 45%, which is also comparable to the results of PE. Furthermore, the depolymerization capability for mixed PE and PP plastics was also evaluated. A combined selectivity of 58% was achieved for a 1:1 mixture of PE and PP, with proportions of 33% ethylene and 25% propylene, showing the versatility in depolymerizing various polyolefin plastics.

To further optimize this process, we considered using different metal elements as the filament materials. Based on the results of using tungsten filaments, 1250 °C was used as the subsequent temperature benchmark. We first considered metal elements that can withstand such a high temperature. For alkali metals, the melting points are too low, typically below 200 °C (Fig. S3). Besides, alkali metals lose their outer electrons easily, which makes them susceptible to reacting with oxygen and moisture in the air to form oxides or hydroxides, which in turn cannot exist in the air as the metal state. The melting points of the alkaline-earth metals are higher, and one among them, Beryllium, reaches a melting point of 1,287 °C, which slightly exceeds the value of 1250 °C (Fig. S4). Moreover, the melting points of the post-transition metals are all below 700 °C (Fig. S5). In contrast, most of the transition metals have appreciably high melting points, providing a large number of options for the study of filament materials (Fig. 2d). After considering the various properties of the metals (such as melting point, ductility, and hardness), 14 metallic materials, including W (Tungsten), Ti (Titanium), V (Vanadium), Fe (Iron), Co (Cobalt), Ni (Nickel), Zr (Zirconium), Nb (Niobium), Mo (Molybdenum), Pd (Palladium), Ta (Tantalum), Re (Rhenium), Ir (Iridium), and Pt (Platinum), were selected as filament materials for subsequent conversion. Figure 2e shows the product distribution and the corresponding ethylene selectivity of PE by means of these above metallic materials. The effect of different metallic materials on PE conversion performance was significant, with ethylene selectivity ranging from ~31% to ~65%. Almost half of the metals presented significantly lower selectivity compared to tungsten, while the rest had similar or even significantly higher performance. For example, when titanium or zirconium was used as a filament material, ethylene selectivity was only below 35%, accompanied by relatively more methane and propane. For niobium, tantalum, or platinum, ethylene selectivity was improved to exceed 60% along with an increase in the proportion of methane, while the portion of all other products was reduced, showing the potential of different metallic materials to modulate monomer selectivity.

Mechanism

We employed computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation to analyze the transformation dynamics. The simulation reveals that the reactor remains predominantly at room temperature immediately after turning on, with only the metal filament reaching high temperatures (Fig. 3a). Under this operation condition, this reactor creates a sharp temperature gradient (>106 °C m−1) within less than 1 mm of the filament in just 0.1 s (Fig. 3b). Unlike conventional heating systems, which exhibit a large spatial region with intermediate temperatures between the high-temperature and ambient-temperature zones, only the central filament maintains an extremely high temperature, while regions just a short distance away remain close to room temperature. This results in a significantly smaller intermediate-temperature region compared to conventional systems, effectively minimizing the occurrence of undesired thermal pyrolysis side reactions in this zone. The depolymerization of PE to ethylene at an elevated temperature of 1250 °C is also thermodynamically favorable and has a considerable kinetic rate. Thus, PE not only melts and vaporizes rapidly near the surface of the metal filament, but also instantly depolymerizes to ethylene monomer when the reactor is activated. The high-temperature zone favorable for PE depolymerization to ethylene expands slightly during the operational period, while maintaining a favorable temperature gradient.

a Three-dimensional transient temperature distribution inside the reactor at the operation time of 0.1 s. b Two-dimensional transient temperature distributions of the axial cross-section at different time scales. Both (a, b) are based on the temperature legend below. c Two-dimensional transient distribution of axial velocity in the axial cross-section at the operation time of 0.1 s. d Two-dimensional transient distribution of cumulative mass flux from inlet to outlet of the reactor at the operation time of 0.1 s. e Schematic of the fluid path in a typical Clusius-Dickel thermal diffusion column. f Two-dimensional transient distribution of the flow field in the y-direction at the operation time of 0.1 s. The light orange color represents the positive direction, and the light blue color represents the negative direction (see Fig. S6 for the full-scale and detailed information).

We further analyzed the axial velocity distribution inside the reactor to elucidate the impact of the flow field (Fig. 3c). Different velocity fields emerged across the radial direction. Notably, a stagnation zone formed around the central high-temperature region near the metal filament, characterized by near-zero velocities and even a tendency to form a reflux zone. This central stagnation caused increased axial velocities near the cooler walls, directing all mass transport through these lower-temperature areas. This indicates that after undergoing a series of rapid melting, vaporization, and depolymerization on the surface of the metal filament, the products do not continue to travel along the high-temperature filament. If they were to do so, it would result in extensive secondary reactions, which would in turn reduce the selectivity. In contrast, the products are transported through the adjacent low-temperature zones, thereby avoiding the occurrence of secondary reactions. The radial mass transport is also important for this process (vide infra). Moreover, this phenomenon was also manifested in the mass flux (Fig. 3d), except for the decrease in velocity and mass transfer due to friction and fluid viscosity in a tiny region near the wall (<1 mm).

This process resembles a Clusius-Dickel thermal diffusion column43,44, which will naturally bring about mass transport in the axial direction opposite to the direction of gravity (Fig. 3e). The Clusius-Dickel thermal diffusion column can be regarded as the reactor in which both the inlet and outlet velocities are set to 0. By balancing this movement with the carrier gas against the thermal diffusion, the stagnation zone on the surface of the metal filament can thus be formed. To assess radial mass transfer within the reactor, the flow field distribution perpendicular to the direction of the metal filament was also analyzed (Fig. 3f). The metal filament surface exhibits a noticeable outward radial velocity, indicating that the polyolefin plastic, after reacting, are transported from the high-temperature zone on the filament surface to the adjacent low-temperature region. This prevents prolonged high-temperature side reactions of the depolymerization products and, when combined with the axial flow field analyzed above, forms a complete mass transfer pathway.

Density function theory (DFT) was conducted to analyze the plastic-derived radical reaction45,46. Linear terminal radical47 (modeled by n-decyl radical, recorded as C10·) initiated by C–C bond cleavage of PE served as the chain initiation radical due to lower bond energy of C–C (3.57 eV) than C–H (4.17 eV). Figure 4a exhibits the activation enthalpy (ΔH) of 3 typical evaluation directions of the C10· radical via self-reaction at 1250 °C under ambient pressure. β-C–C bond scission48 shows the lowest energy barrier in enthalpy of 1.07 eV, compared to β-C–H bond scission, β-H rearrangement (α-C–H and α-C–C show the extremely high bond energies, Fig. S10), and is significantly lower than internal C–C/C–H bond energies.

a DFT-derived bonding energies of internal C–C/C–H bond energies in C10H22 and the activation enthalpy of β-C–C bond scission, β-C–H bond scission, and β-H rearrangement of C10H21· radical with the DFT-optimized transition state structures insert. b DFT-derived reaction free energy diagrams for C10H21· decomposition at 1250 °C and 1 atm. c The temperature dependences of ΔG for the generation of C2H4, C10H20, and C3H8 from C10H21·, generation of CH4 from C10H22 and H·, and dehydrogenation of C2H4 to C2H2.

The β-C–C bond cleavage as the most favorable pathway in kinetics can generate one C2H4 and another terminal radical with two C-atom releases (C8·) as shown in Fig. 4b (corresponding enthalpy and entropy diagrams shown in Fig S11). This chain propagation reaction maintains the continuous β-C–C scission of terminal radicals to produce C2H4 as the kinetically favored product until C2H5· radical formation (ΔGa for TS1–4 is at a range of 1.00 to 1.02 eV). In contrast, β-H rearrangement needs to overcome a high free energy barrier of 1.67 eV (TS1’) can release on H· radical and produce a 1‑decene (C10,=) and the further scission of 1‑decene is difficult in the gas phase by itself (Fig. S12). The secondary alkyl radical (C10·’) may be formed by β-C–H bond scission with a higher free-energy barrier of 1.87 eV, and the subsequent β-C–C scission of C10·’ re-generate the terminal radical and produces propane (scheme for propane formation shown in Fig. S13). Furthermore, the over-dehydrogenation of C2H4 to C2H2 shows the difficulty of breaking the C–H bond of C2H4 with the extremely high free energy barrier 4.10 eV. These results indicate that the gas-phase radical reaction initiated by terminal radicals prefers to produce ethylene rather than long-chain alkene, propane, and acetylene. As predicted, the same chain propagation via β-C–C scission can also occur on the terminal radical from polypropene to propane (Fig. S14).

The effect of temperature on free-energy change (ΔG) of various product formations in radical reactions is shown in Fig. 4c. Producing C2H4 exhibits the negative ΔG at a temperature higher than ~500 °C, favorable in thermodynamics. Producing C3H6 shows a little lower ΔG than C2H4, which is the potential reason that makes C3H6 predominant in the by-products. CH4 is formed by the free H· radical attacking the methyl group of the carbon chain but this bi-molecule reaction occurs with a much lower probability than mono-molecule scission in such a dilute, high-temperature gaseous environment (The potential evolution of H· radical is shown in Fig. S15). The thermodynamic results further confirm that in the high-temperature zone at the initial stage of the reaction, ethylene is the predominant gaseous product, whereas in the adjacent lower-temperature zone, all side reactions cease to occur, thereby maintaining the high selectivity of ethylene. Meanwhile, the reaction process is not kinetically limited, as the generation of ethylene proceeds at a higher rate compared to alternative chemical pathways (Fig. S16). As the temperature increases, all of the products show a decrease in the formation of free energy, matching the decrease of ethylene selectivity in higher-temperature experiments (Fig. 2a). It is worth noticing that chain initiation on metal filament surface plays an important role, and medium-level adsorption energy for carbon chain is beneficial to initiate the terminal radical and corresponds to more ethylene formation (Fig. S17).

Discussion

By using commercially available industrial-grade tungsten filaments for cyclic experiments of the depolymerization reaction, the tungsten filaments maintained consistent selectivity performance (47–50%) after several experiments (Fig. S18). To confirm whether the tungsten filaments can be used repeatedly, we also characterized the filaments after multiple experiments. The results of SEM-EDS at different scales illustrated that the microscopic morphology and elemental distribution of the tungsten filaments did not show significant changes during the reaction process, except for some slight changes on the surface of the tungsten filament (Figs. S20–25). SEM-EDS at higher magnifications revealed that an increased number of reactions led to an increased surface roughness of the tungsten filament (Figs. S26–28), which was attributed to the recrystallization of tungsten at elevated temperatures49,50. Although the observed surface roughening did not affect performance in the current experiments, the physical change of the tungsten filament should be considered as a potential factor contributing to metal failure in long-term applications. Moreover, we observed from the XPS results that the tungsten oxide on the surface of the tungsten filament was slightly reduced to metallic tungsten (Fig. S29 and Table S5), which was attributed to trace amounts of hydrogen produced during the plastic depolymerization reaction such as ethylene dehydrogenation51. In practice, the trace reduction reaction can potentially be counteracted with trace amounts of oxygen during the reaction to bring about oxidation and increase oxygen tolerance. For potential larger-scale applications, strategies such as tungsten filament or reactor arrays, as well as approaches inspired by the carbon fiber prepreg manufacturing industry, could be feasible options52,53.

Furthermore, the possibility of further improving selectivity in the context of the application was also explored. While some other metals have demonstrated better performance than commercial tungsten filament, other pure metals tend to be more expensive and their mechanical properties are often difficult to be compared to those of tungsten. Therefore, we first tried to use tungsten filament as the substrate and electrodeposited a layer of other metal on the surface of the tungsten filament to improve the selectivity. Since the metal ions of niobium and tantalum are susceptible to hydrolysis and formation of oxide or hydroxide precipitates and are not suitable for electrodeposition in aqueous solution54,55, platinum was chosen as the target element for electrodeposition. After depositing platinum on the tungsten filament surface, the initially obtained platinum-plated tungsten filament achieved a higher selectivity compared to the initial tungsten filament, although the electrodeposition process has not been optimized (Fig. S30). Furthermore, we also evaluated the possibility of using bulk commodity alloys with favorable economics and excellent mechanical strength. Stainless steel is one of the most common bulk commodity alloys, and it has also been reported that stainless steel has a beneficial catalytic effect in the depolymerization of waste plastics56,57. When stainless steel was used as the filament material, the ethylene selectivity reached up to 63%, which is comparable to the finest pure metals (Fig. S29). The cyclic experiments showed relatively stable performance after multi reactions (Fig. S19). Regardless of whether tungsten, niobium, tantalum, or stainless steel is used, the ethylene selectivity based on this method is much improved compared to previously reported catalytic pyrolysis studies (Table S6).

Since Dong et al. reported a carbon felt-based Joule heating method that achieved up to 36% selectivity in depolymerizing PP into propylene monomer34, studies on the effective depolymerization of plastics via Joule heating have been rapidly and continuously developing. For example, Selvam et al. coupled carbon paper with an H-ZSM-5 catalyst and achieved remarkable selectivity of over 90% for C2–C4 hydrocarbons via Joule heating, although the specific selectivity for C2 from PE is in the range of 10–20%, while C3 from PP in the range of 40–45%35. More recently, Ma et al. combined Joule heating-based plastic depolymerization with CO₂ dry reforming, enabling the transformation of various types of waste plastics into syngas36. However, the selectivities for monomer recovery from polyolefins are still not too high. Therefore, the 65% monomer selectivity achieved by our method may further enhance the feasibility of integrated polyolefin depolymerization-repolymerization processes in a circular manner. In addition, given that previous Joule heating methods have mainly used carbon materials as the heating medium, our approach involving a wide range of metal materials also holds promise in expanding the applicability of Joule heating by harnessing the catalysis power of metal elements.

In summary, we report a light bulb-inspired high-temperature catalytic method for depolymerizing polyolefin plastic into olefin monomer selectively. Commercial tungsten filament can be directly applied for the selective depolymerization of polyolefins, while 14 different high-melting-point metal filaments can also be employed, offering tunable control over monomer selectivity. Kinetically, β-C–C bond cleavage dominates due to its lowest activation barrier (1.07 eV), driving a chain-propagating mechanism that selectively generates olefin monomer. The formation of monomer becomes increasingly thermodynamically favorable with decreasing Gibbs free energy at elevated temperatures. The selectivity of commercial tungsten filaments can be enhanced by electrodeposited with other transition metals or even by substitution with commodity-grade stainless steel to improve performance, with all of these monomer selectivities over 60%. However, the specific technical processes and implementation schemes still require further improvement and optimization to achieve larger-scale applications in the future. Meanwhile, the separation and purification of additives, fillers, pigments introduced during manufacturing, as well as various plastic impurities and even contaminants introduced during post-consumer recycling, must also be taken into account in practical applications. In addition, the potential interactions at high temperatures between these impurities, moisture, and the metal filament materials should be carefully considered. If reused under more stringent industrial conditions, not only must the mechanical properties of different metal materials be guaranteed strictly, but carbonization reaction and coke formation of different metal materials must also be avoided to prevent a decrease in reactivity or filament breakage and failure.

Methods

Depolymerization experiment

The metal filament was coated with plastic by heating the polymer until molten, then allowing it to resolidify uniformly on the filament surface, forming a coating without decomposition. The coated filament ends were secured in OT-type copper fittings, which were bolted to copper wire connectors linked to a small direct current (DC) power supply for Joule heating. The assembly was positioned at the center of a quartz tube, sealed at both ends with fluorinated rubber O-rings. Argon was used to purge the reactor by repeated vacuum–refill cycles followed by a one-hour continuous flow to remove residual oxygen or impurities. During operation, the DC power supply illuminated the filament, whose temperature was monitored using an Optris PI 05 M infrared camera and cross-checked by its resistance change. Reaction gases were collected at the outlet in a sampling bag and analyzed by gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (GC-FID).

Characterization techniques

Elemental analysis (ThermoFisher Scientific FlashSmart CHNS Elemental Analyser) was used to analyze the elemental composition. To determine the molecular structures of the samples, Raman spectra (Renishaw inVia Qontor confocal Raman microscope) outfitted with a Renishaw Centrus 4AUL40 detector were used. The FTIR spectroscopy was collected on an Agilent Cary 660 spectrometer to analyze the organic functional groups. In order to investigate the surface chemical states, XPS analysis was conducted using a Kratos AXIS ULTRADLD instrument manufactured by Shimadzu, Japan. 1H magic-angle spinning (MAS) solid-state NMR spectroscopy and 13C cross-polarization (CP)/MAS/total suppression of sidebands (TOSS) solid-state NMR spectroscopy measurements were conducted on a Bruker Avance NEO 500 MHz NMR spectrometer. HT-GPC (Agilent PL-GPC 220) experiments were performed to obtain the molecular weight distributions of the polymers. SEM (JSM-7610F Plus, JEOL, Japan) and EDS (X-MaxN, Oxford Instruments) were conducted to observe the microscopic morphology and elemental distribution of the filaments.

More detailed experimental methods are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R. & Law, K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700782 (2017).

Ahrens, A. et al. Catalytic disconnection of C–O bonds in epoxy resins and composites. Nature 617, 730–737 (2023).

Clarke, R. W. et al. Dynamic crosslinking compatibilizes immiscible mixed plastics. Nature 616, 731–739 (2023).

Jambeck, J. R. et al. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 347, 768–771 (2015).

Thompson, R. C. et al. Lost at sea: Where is all the plastic?. Science 304, 838–838 (2004).

Carney Almroth, B. et al. Understanding and addressing the planetary crisis of chemicals and plastics. One Earth 5, 1070–1074 (2022).

Browne, M. A. et al. Accumulation of microplastic on shorelines woldwide: sources and sinks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 9175–9179 (2011).

Kim, J., Jang, J., Hilberath, T., Hollmann, F. & Park, C. B. Photoelectrocatalytic biosynthesis fuelled by microplastics. Nat. Synth. 1, 776–786 (2022).

Sullivan, K. P. et al. Mixed plastics waste valorization through tandem chemical oxidation and biological funneling. Science 378, 207–211 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. Polyethylene upcycling to long-chain alkylaromatics by tandem hydrogenolysis/aromatization. Science 370, 437–441 (2020).

Liu, M., Wu, X. & Dyson, P. J. Tandem catalysis enables chlorine-containing waste as chlorination reagents. Nat. Chem. 16, 700–708 (2024).

Garcia, J. M. & Robertson, M. L. The future of plastics recycling. Science 358, 870–872 (2017).

Schyns, Z. O. G. & Shaver, M. P. Mechanical Recycling of Packaging Plastics: A Review. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 42, 2000415 (2021).

Kakadellis, S. & Rosetto, G. Achieving a circular bioeconomy for plastics. Science 373, 49–50 (2021).

Zhang, M.-Q. et al. Catalytic strategies for upvaluing plastic wastes. Chem 8, 2912-2923 (2022).

Van Geem, K. M. Plastic waste recycling is gaining momentum. Science 381, 607–608 (2023).

Jehanno, C. et al. Critical advances and future opportunities in upcycling commodity polymers. Nature 603, 803–814 (2022).

Ellis, L. D. et al. Chemical and biological catalysis for plastics recycling and upcycling. Nat. Catal. 4, 539–556 (2021).

Li, H. et al. Hydroformylation of pyrolysis oils to aldehydes and alcohols from polyolefin waste. Science 381, 660–666 (2023).

Ma, D. Transforming end-of-life plastics for a better world. Nat. Sustain. 6, 1142–1143 (2023).

Martín, A. J., Mondelli, C., Jaydev, S. D. & Pérez-Ramírez, J. Catalytic processing of plastic waste on the rise. Chem 7, 1487–1533 (2021).

Lu, H. et al. Machine learning-aided engineering of hydrolases for PET depolymerization. Nature 604, 662–667 (2022).

Tournier, V. et al. An engineered PET depolymerase to break down and recycle plastic bottles. Nature 580, 216–219 (2020).

Chen, C. C. et al. General features to enhance enzymatic activity of poly(ethylene terephthalate) hydrolysis. Nat. Catal. 4, 425–430 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. Depolymerization of polyesters by a binuclear catalyst for plastic recycling. Nat. Sustain. 6, 965–973 (2023).

Lee, K., Jing, Y., Wang, Y. & Yan, N. A unified view on catalytic conversion of biomass and waste plastics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 635–652 (2022).

Kugelmass, L. H., Tagnon, C. & Stache, E. E. Photothermal mediated chemical recycling to monomers via carbon quantum dots. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 16090–16097 (2023).

Lee, W.-T. et al. Mechanistic classification and benchmarking of polyolefin depolymerization over silica-alumina-based catalysts. Nat. Commun. 13, 4850 (2022).

Coates, G. W. & Getzler, Y. D. Y. L. Chemical recycling to monomer for an ideal, circular polymer economy. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 501–516 (2020).

Conk, R. J. et al. Catalytic deconstruction of waste polyethylene with ethylene to form propylene. Science 377, 1561–1566 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Low-temperature upcycling of polyolefins into liquid alkanes via tandem cracking-alkylation. Science 379, 807–811 (2023).

Zheng, K. et al. Progress and perspective for conversion of plastic wastes into valuable chemicals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 8–29 (2023).

Häußler, M., Eck, M., Rothauer, D. & Mecking, S. Closed-loop recycling of polyethylene-like materials. Nature 590, 423–427 (2021).

Dong, Q. et al. Depolymerization of plastics by means of electrified spatiotemporal heating. Nature 616, 488–494 (2023).

Selvam, E., Yu, K., Ngu, J., Najmi, S. & Vlachos, D. G. Recycling polyolefin plastic waste at short contact times via rapid joule heating. Nat. Commun. 15, 5662 (2024).

Ma, Q. et al. Grave-to-cradle dry reforming of plastics via Joule heating. Nat. Commun. 15, 8243 (2024).

Dai, L. et al. Pyrolysis technology for plastic waste recycling: a state-of-the-art review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 93, 101021 (2022).

Anuar Sharuddin, S. D., Abnisa, F., Wan Daud, W. M. A. & Aroua, M. K. A review on pyrolysis of plastic wastes. Energy Convers. Manag. 115, 308–326 (2016).

Zhao, D., Wang, X., Miller, J. B. & Huber, G. W. The chemistry and kinetics of polyethylene pyrolysis: a process to produce fuels and chemicals. ChemSusChem 13, 1764–1774 (2020).

Widagdo, S. Incandescent light bulb: product design and innovation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 45, 8231–8233 (2006).

Schade, P., Ortner, H. M. & Smid, I. Refractory metals revolutionizing the lighting technology: a historical review. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 50, 23–30 (2015).

Encinar, J. M. & González, J. F. Pyrolysis of synthetic polymers and plastic wastes. Kinetic study. Fuel Process. Technol. 89, 678–686 (2008).

Müller, G. & Vasaru, G. The Clusius-Dickel thermal diffusion column—50 years after its invention. Isotopenpraxis 24, 455–464 (1988).

Budin, I., Bruckner, R. J. & Szostak, J. W. Formation of protocell-like vesicles in a thermal diffusion column. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 9628–9629 (2009).

Gaussian 16 Rev. B.01 (Wallingford, CT, 2016).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Wang, L. et al. An atomic insight into reaction pathways and temperature effects in the degradation of polyethylene, polypropylene and polystyrene. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 215, 110450 (2023).

Zuo, Y. et al. Optimizing ethylene production through enhanced monomolecular β-scission in confined catalytic cracking of olefin. ACS Catal. 15, 1576–1585 (2025).

Šestan, A., Jenuš, P., Krmpotič, S. N., Zavašnik, J. & Čeh, M. The role of tungsten phases formation during tungsten metal powder consolidation by FAST: implications for high-temperature applications. Mater. Charact. 138, 308–314 (2018).

Yu, H., Das, S., Liu, J., Hess, J. & Hofmann, F. Surface terraces in pure tungsten formed by high temperature oxidation. Scr. Mater. 173, 110–114 (2019).

Kuroki, T., Sawaguchi, T., Niikuni, S. & Ikemura, T. Mechanism for long-chain branching in the thermal degradation of linear high-density polyethylene. Macromolecules 15, 1460–1464 (1982).

Dong, Q., Hu, S. & Hu, L. Electrothermal synthesis of commodity chemicals. Nat. Chem. Eng. 1, 680–690 (2024).

Hu, Q. et al. Manufacturing and 3D printing of continuous carbon fiber prepreg filament. J. Mater. Sci. 53, 1887–1898 (2018).

Schubert, T. in Electrodeposition from Ionic Liquids 95-155 (2017).

Mellors, G. W. & Senderoff, S. Electrodeposition of coherent deposits of refractory metals: I. Niobium. J. Electrochem. Soc. 112, 266 (1965).

Zhang, Y., Nahil, M. A., Wu, C. & Williams, P. T. Pyrolysis–catalysis of waste plastic using a nickel–stainless-steel mesh catalyst for high-value carbon products. Environ. Technol. 38, 2889–2897 (2017).

Liu, Q. et al. Pyrolysis–catalysis upcycling of waste plastic using a multilayer stainless-steel catalyst toward a circular economy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2305078120 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank the MOE Tier-2 project (MOE-T2EP10221-0020) from the Ministry of Education, Singapore and the National Research Foundation, Singapore, NRF Investigatorship (NRFI07-2021-0015) for the financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.Y. supervised the project. N.Y. and S.Y. conceived the research. S.Y. designed the experiments. S.Y., H.L. and S.W. built the reaction system. S.Y. carried out the experiments, conducted the characterization, and analyzed the data. P.H. contributed to the experiments and characterization. J.X. contributed to the characterization. S.Y. carried out the numerical simulation. P. H. and S. Y. designed the DFT calculation. P.H. performed the DFT calculation. S.Y., P.H. and N.Y. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, S., Han, P., Li, H. et al. Light bulb-inspired high-temperature catalytic depolymerization of polyolefin plastic with high monomer selectivity. Nat Commun 16, 10494 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65524-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65524-2