Abstract

Atmospheric water harvesting technology, which extracts moisture from ambient air to generate water, is a promising strategy to realize decentralized water production. However, the prohibitively high energy consumption of heat-induced evaporation process of water extraction hinders the technology deployment. Here we demonstrate that vibrational mechanical actuation can be used instead of heat to extract water from moisture harvesting materials, offering about forty-five-fold increase in the extraction energy efficiency. We report the energy consumption for water extraction below the enthalpy of water evaporation, thus breaking the thermal limit of the energy efficiency inherent to the state-of-the-art thermal evaporation and making atmospheric water harvesting technology economically feasible for adoption on scale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many communities worldwide are located in arid climate zones and experience a shortage of fresh water resources, which severely inhibits their land development and creates harsh humanitarian conditions for their populations1. More than half of Mexico’s national territory lies in the arid and semi-arid climate zones, including the Chihuahuan and Sonoran deserts, which extend northward into the United States. The Colorado River is drying up at an alarming rate, putting these areas at even higher risk of freshwater shortages. Similarly, in southern Ukraine, desertification of thousands of hectares of fertile steppe land may occur following the breach of the Kakhovka Dam by the Russian army in 2023, with potentially grave consequences for the world food supply. The situation is even more dire in the Middle East, where only three major rivers supply the vast region with fresh water, and where most land areas are arid. In many cases, the climate problems are exacerbated by the economic and security-related ones, which make the costs of the industrial installations for water purification prohibitive for communities in need2,3.

Fortunately, the Earth's atmosphere provides a vast resource of fresh water. Fog harvesting has been ubiquitously practiced by plants, animals, and humans throughout history4,5,6,7,8,9,10. However, the majority of the 12,900 billion tons of fresh water stored in the atmosphere11 is not available as fog, which only forms when the relative humidity (RH) of air approaches 100%. Accordingly, there is a need for atmospheric water harvesting (AWH) technologies that can operate in arid or semi-arid climates or in regions where large-scale installations are impractical due to economic or security reasons12,13,14,15,16,17,18. These typically fall into two major categories, including (i) active refrigeration technology19,20 to cool air below the dew point and promote condensation20,21,22,23, and (ii) sorption-desorption technology that employs porous hydrophilic sorbents to collect moisture from air, followed by water extraction via the heating-induced evaporation-condensation process12,21,24,25.

However, the former technology is hard to scale down to realize affordable decentralized water production, while the latter one, in its current state of development, exhibits prohibitively high energy consumption associated with the heat-driven process of water desorption from AWH materials. The temperature needed to release the captured water from a sorbent can be as high as 160 °C for conventional desiccants such as silica gel, zeolite, and activated alumina26,27,28. Desorption temperatures of other recently-developed sorbents, including hydrogels15, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)12,21, and anhydrous and hydrated salt couples13 are in the 60 °C–80 °C range, which makes water release an energy-intensive process29,30. Furthermore, all the AWH prototypes demonstrated to date exhibit at least an order of magnitude higher energy consumption than the predicted thermodynamic limit of about 2MJ/kg at 30% RH29. This is a major bottleneck of the sorption-desorption AWH technology, which limits its contribution to the United Nations’ 6th Sustainable Development Goals (SDG6)31.

The ongoing efforts to increase water harvesting capability and reduce the energy consumption mostly focus either on engineering more efficient sorbents (i.e., capable of sorbing higher weight of water per gram of material)32,33 or/and on designing autonomous AWH systems that can utilize solar energy12,13,21,33. Since the energy consumption occurs during the desorption process, finding alternative technologies to replace heat-driven evaporation is the key to achieving a breakthrough in the AWH technology feasibility. Recent studies showed that re-engineering the sorbent structure to facilitate water evaporation at lower temperatures, e.g., by incorporating a secondary network of reconfigurable phase-change polymers30, or by combining heating with other external stimuli, such as sunlight or laser illumination can increase the evaporation efficiency, even beyond the thermodynamic limit34.

Here, we propose an alternative method of moisture extraction, which uses vibrational mechanical actuation enabled by piezoelectric materials (Fig. 1, Supplementary Movie 1, Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Fig. S1) to extract water from AWH sorbents. We draw inspiration from prior studies that used piezoelectric actuators35 and Si-based Micro-Electro-Mechanical-system (MEMS)36 for atomization of liquids. We show that this method offers at least a forty-five-fold reduction of the energy needed to extract the same mass of water as the standard evaporation-condensation technique. While demonstrated here for hydrogels, the technique is very general and may be used with other sorbents, including MOFs, superabsorbent fibers and textiles, salts, and desiccants. Since the alternative technology is not based on the heating-induced evaporation, its efficiency is not bound by the thermal limit derived for the conventional desorption process, offering promise for further efficiency improvements.

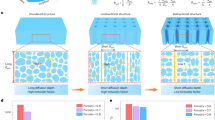

a The ultrasonic extractor comprises a PZT-crystal piezoelectric transducer and a stainless-steel (SS) porous membrane through which the desorbed water is extracted from a sorbent material under vibrational actuation. The black dashed box shows the transducer structure, including an Ag-coated PZT ring topped with a thin layer of water-resistant resin attached to the SS membrane and encased in a silicone elastomeric ring. The red dashed box shows the structure of the micro-machined nozzles on the SS membrane, which assist in directing the flow of water out of the device. b The diagram of the system assembly and sorption/desorption stages of the moisture harvesting process utilizing a sorbent material and a micro-actuator. The top Ag layer and the SS membrane are connected to the electrode wires. c A CAD model of the system custom-designed to collect the moisture extracted from the sorbent by the actuator. d A photograph of the FDM-printed device prototypes with hydrogel sorbents in the process of moisture harvesting from ambient air. The inset shows a close-up view of the collected water droplets on the glass enclosure. e Efficiency values of the moisture extraction achieved in this study compared with the state-of-the-art literature data (here, s = short actuation period; l= long actuation period; s_m = multiple repetitive cycles of short actuation periods). Scale bars: 50 µm (a); 15 mm (d).

Results

Figure 1a illustrates a piezoelectric-ceramic-based single-head ultrasonic actuator used in this study for water extraction from several AWH hydrogels (AWH-Hs). High-voltage-driven lead zirconate titanate (PZT) ring converts applied electrical power into the in-plane displacement of the ring, which in turn causes out-of-plane mechanical oscillation of the steel mesh membrane clamped to the ring. Mechanical oscillation of the membrane is accompanied by the Joule heating caused by ferroelectric hysteresis loss of the PZT material when driven at high frequency37, as illustrated in Fig. 1b. Here, we show that a synergetic impact of the mechanical actuation and device heating facilitates moisture extraction from AWH-Hs, reduces the extraction time, and increases the system energy efficiency. The first prototype device utilizing this water extraction method is shown in Fig. 1c, d.

In Fig. 1e, we plot the energy efficiency of water extraction \(\eta\), which is defined as a ratio of the enthalpy of water vaporization \({h}_{{lv}}\) (\({h}_{{lv}}=2.257{M}{\rm{J}}/{\rm{kg}}\) at 100 °C) and the energy consumption of the device needed for the extraction of a unit mass of water from a sorbent, \(E\) [MJ/kg]: \(\eta={h}_{{lv}}/E\)29,38,39 (see Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Table 4). In an ideal thermal process, where the enthalpy of desorption is identical to the enthalpy of vaporization of water, all the heat provided to the system is used for water evaporation, i.e., \(E={h}_{{lv}}\). In this work, we refer to this ideal thermal process with \(\eta=100\%\) as the thermal limit. In any real thermal water release process, the heat provided is used not only to evaporate water, but also to sensibly heat the system and sorbent, and is partially lost to the ambient, leading to \(\eta < 100\%\). Conversely, an efficient non-thermal extraction method (such as, e.g., vibrational actuation) can have a specific energy consumption lower than the enthalpy of vaporization of water, \({h}_{{lv}}\). Then, the energy efficiency of the water release process can in principle exceed 100%.

Figure 1e compares the efficiency of our device operated with a polyacrylamide and lithium chloride (PAM-LiCl) hydrogel sorbent with that of the-state-of-the-art AWH devices40,41,42,43,44. The extraction efficiency values plotted in Fig. 1e for different systems account for the specific heat of both water and other solids used in the system (i.e., sorbent materials, heaters, enclosures, etc.) as well as heat dissipation losses. Each of the devices in Fig. 1e represents a single-stage system without heat recovery, and thus these efficiency values are all less than 100%. Our device shown in Fig. 1a–d demonstrated energy efficiency of almost 428%, exceeding the state-of-the-art efficiency of 9.5%39,45 by a factor of ~45 (Fig. 1e). In the following, we analyze the performance of the system operated with hydrogel-based sorbents, but the concept is much broader, encompassing a variety of AWH materials and actuator types, and showing a potential to further increase the efficiency.

We synthesized three types of PAM-LiCl AWH hydrogels (see Methods), which incorporate lithium (Li⁺) and chloride ions (Cl⁻) as essential elements for their ability to adsorb water molecules from atmosphere (Fig. 2a)46. Hydrogels had the same salt and polymer content, but different amounts of N,N’-methylenebisacrylamide (MBA) crosslinker, and thus exhibited different crosslinking densities. Hydrogels labeled HG-A, HG-B, and HG-C had crosslinker-to-monomer mass ratios of 0.1, 0.5, and 10 mg/g, respectively. HG-A had very low rigidity, while HG-C could stand on its own outside a Petri dish without collapsing (Fig. 2b). As a result, HG-A hydrogel demonstrated greater resistance to tearing when manually stretched, in contrast to the more rigid HG-C, which can be torn easily (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Movie 2). The differences in the hydrogels micro-structure and surface morphology are revealed by the scanning electron microscope (SEM) images, with HG-A exhibiting a low-density structure (Fig. 2d) and HG-C (Fig. 2e)—a more compact one. We also included in our study a commercial hydrogel (a cross-linked glycerol- 2-Acrylamido-2-methylpropanesulfonic acid sodium salt hydrogel), and labeled it HG-M.

a A schematic of the structure of a PAM-LiCl hydrogel with solvated lithium (Li⁺) and chloride (Cl⁻) ions diffused into a polymer network. b Photographs of synthesized PAM-LiCl hydrogels inside and outside a Petri dish, illustrating the contrast between the samples with the highest (HG-A) and the lowest (HG-C) storage moduli. c Optical images of the HG-A and HG-C hydrogels under manual stretching. d,e SEM images of HG-A (d) and HG-C (e) samples. f Mechanical properties of hydrogels measured at 25 °C and with an oscillatory load at 6.3 rad/s. g Water uptake (g/g) of hydrogels at four different RH levels at 25 °C. Scale bars: 12 mm (b); 24 mm (c), 200 µm (d); 300 µm (e).

The four types of AWH-Hs were compared by their elastic storage moduli (see Methods), which provide a measure of how much energy is stored in the material when it is subjected to a periodically oscillating load, and their loss moduli, which measure the material’s ability to dissipate applied stress through heat (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Figs. S2-S3). The progressively higher storage moduli of hydrogels with higher MBA content validate the strategy of engineering sorbents with desired mechanical properties by varying the density of chemical crosslinks47. All the PAM-LiCl sorbents exhibited loss moduli lower than their storage moduli, and thus the resultant phase shift between the mechanical deformation and the sorbent material response, \(\tan \delta=G{\prime} {\prime} /G{\prime} < 1\). This indicates the elasticity and ability of these materials to bounce back to their original shape as long as the applied deformation is below their yield point48. These data are similar to those previously reported for salt-free PAM hydrogels49, suggesting that the high salt content does not play a major role in their mechanical properties, which are mostly controlled by the polymer crosslinking density. In turn, the commercial hydrogel (HG-M) exhibited higher values of storage and loss moduli as well as \(\tan \delta\) value, thus demonstrating higher mechanical strength than PAM-LiCl AWH-Hs, but slightly lower elasticity.

Figure 2g shows that all three PAM-LiCl AWH-Hs exhibit high water uptake in different environments, from arid to very humid, between 15 and 85% RH (see Supplementary Movie 3 for water harvesting at ~15% RH). This is consistent with recent reports on PAM-based hydrogels and hygroscopic PAM-LiCl composite hydrogels exhibiting a large capability to capture moisture30,32. Water harvesting capacity at the same RH level is similar for all the PAM-LiCl AWH-Hs regardless of their crosslinking density32,50,51. In contrast, the commercial HG-M did not demonstrate any water sorption capability at low RH (15 and 30%).

The goal of the study is to use a piezoelectric actuator to generate and transmit a pressure wave into the AWH hydrogels to facilitate water extraction. To optimize the actuator geometry and performance, several candidate devices were evaluated. Based on prior literature for water atomization, we targeted a resonance frequency in the 100-160 kHz range35,36,52,53. Four piezoelectric ultrasound transducers with resonance frequencies ranging from ~107–115 kHz to ~165 KHz were designed and analyzed (Supplementary Fig. S4). Three devices had similar geometry but differed by the size of micro-nozzles perforated in their metallic membranes. The fourth device (PZ-D) had a comparatively lower diameter to thickness aspect ratio, ensuring higher ( ~ 165KHz) resonance frequency (see Supplementary Table 1). All the four devices demonstrated comparable piezoelectric coefficients (\({d}_{33}=\sim 435-440{\rm{pC}}/{\rm{N}}\)), which were measured using “quasi-static” or “Berlincourt” method, employing a static force sensor and piezoelectric meter (see Methods and Supplementary Fig. S5). The piezoelectric charge coefficient, denoted as \({d}_{33}\), is determined by applying a unit stress in the direction 3 (i.e., z-axis) that induces polarization in direction 3 (i.e., in the same direction as the polarization of the ceramic element).

All four devices were designed such that the diameter of the piezoelectric ceramic ring was at least ten times larger than its thickness (\(d > 10t\)) to maximize their displacement amplitude54. The efficiency of the piezoelectric devices in converting electric energy into mechanical energy was evaluated by their effective electromechanical coupling coefficients (\({k}_{{\rm{eff}}}\))55,56, which were found to be around 0.19 for the low-frequency devices and 0.17 for the high-frequency device (Supplementary Fig. S6). The rest of the electrical power is dissipated as heat, leading to some temperature increase of the actuator and AWH-H sorbents.

First, the nozzle size was varied to improve water extraction through the membrane without degrading the resonant behavior of the actuator, as resonance frequencies of piezoelectric devices are sensitive to variations in the membrane mass and stiffness57. PZ-A, PZ-B, and PZ-C devices were designed to each have 1000 nozzles with diameters of 10, 70, and 100 µm, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S7). Figure 3a compares the water conductance through the membranes with different nozzle sizes measured using a forward-osmosis (FO) configuration (see Methods and Supplementary Fig. S8). The water transport rate through the PZ-C membrane was found to be the highest, owing to its larger nozzle size.

a The effect of the increased nozzle size on water conductivity through the porous membrane as determined by a forward-osmosis experiment. Here and in (b,c), the data for membranes in PZ-A, PZ-B, and PZ-C transducers with nozzle sizes of 10, 70, and 100 µm are color-coded as orange, pink, and blue, respectively. PZ-D actuator had the same nozzles as PZ-A. b,c Deflection amplitudes (b) and corresponding RMS velocities (c) of the four transducers subjected to a sinusoidal input signal at 1 Vpp measured at resonant frequencies of ~110 KHz for PZs A, B, and C, and ~165 kHz for PZ-D. d Experimental modal analysis of the porous membrane attached to the ring of PZ-C transducer at 1 Vpp actuation. e–g The deflection maps across the PZ-C membrane at frequencies of 110 KHz (e), 89 (f), and 115 KHz (g) measured by a PICOSCALE vibrometer under 1 Vpp (0.35 Vrms) sinusoidal signal input. h Simulated (COMSOL Multiphysics®) displacement and velocities of the PZ-C membrane plate under higher voltages. i,j The simulated (i) and measured (j) impedance spectra of the PZ-C actuator.

AWH-Hs are actuated by the motion of the free-standing portion of the membrane that is not clamped to the PZT ring (Fig. 1a), and both the magnitude and velocity of its movement need to be maximized for efficient extraction. The diameters of these areas measured 7.8 mm for PZ-A, B, C actuators, and 5 mm for the PZ-D device. Figure 3b compares the maximum displacement amplitudes measured within the nozzle areas (M) of the membranes and the peripheral nozzle-free (P) areas, while Fig. 3c shows the corresponding RMS values of the deflection velocity. The transducers operating at lower frequencies (PZs-A, B, C) exhibit larger amplitude and velocity, both within the nozzle area and the periphery, compared to the higher-frequency device (PZ-D). For all the devices, the displacement amplitudes and velocities are higher in the center than on the periphery, as expected. PZ-C actuator membrane exhibited the largest displacements and RMS velocities. We attribute this to the larger nozzle diameter, which reduced the weight of the membrane, lowered its inertia, and modified its vibrational modes spectrum, leading to better coupling between the piezo oscillations and the membrane vibrations.

The resonant spectra of the membranes integrated in the actuators were measured by using a vibrometer at 1 Vpp (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Figs. S9-S10). Experimentally mapped vibrational mode profiles of the PZ-C membrane at its three dominant frequencies (89, 110, and 115 KHz) are shown in Fig. 3e–g. Supplementary Movies 4-5 and Supplementary Figs. S11-S12 visualize spatial amplitude and phase distributions of these vibrational modes. The actuation voltage of 1 Vpp was used for the above measurements to prevent the displacement amplitude over-range, as the vibrometer is not capable of detecting displacements larger than half-wavelength in magnitude (\(\lambda /2=775{\rm{nm}}\)). However, during the desorption process, the device is actuated by a much larger voltage of ~114 Vpp using an amplifier with a high gain to boost the signal strength. To evaluate the displacement and velocity of the PZ-C actuator membrane at its operational voltage, we simulated the device performance via finite-element modeling with the COMSOL Multiphysics software (Fig. 3h). Modeling predicts that both the membrane displacement and the speed grow linearly with applied voltage, reaching the values of 111 µm and 77 m/s, respectively, at 70 V.

The simulated spectrum of the PZ-C device (Fig. 3i) exhibits a characteristic Fano feature with the resonance (107 KHz) and anti-resonance (109 KHz) frequencies, which is in good agreement with the corresponding spectrum measured experimentally in the fabricated PZ-C device (Fig. 3j). The measured spectra for devices PZ-A, PZ-B and PZ-D are shown in Supplementary Fig. S13. The resonance frequency of device PZ-D was measured to be around 170 ± 5 KHz.

Finally, our finite-element simulations of the PZ-C membrane oscillations (see Methods) reveal the vibrational mode pattern forming under the piezo actuation and predict the values of M displacement (790 nm) (Supplementary Fig. S14) and corresponding velocity (0.54 m/s) (Supplementary Fig. S15) at 1 Vpp, which is in reasonable agreement (within the order of magnitude) with their experimentally measured counterparts (i.e., 373 nm and 0.18 m/s, respectively).

Figure 4a illustrates an actuator, which includes a PZT ring and a membrane and acts both as a mechanical transducer and as a Joule heater. To analyze and optimize the extraction process, the AWH-H samples were soaked in the DI water and placed on top of the membrane (Fig. 4b, c and Supplementary Fig. S16). We first used a commercial hydrogel (HG-M) to evaluate the efficiency of water extraction and to establish an optimum experimental protocol of sorbent actuation. To visually capture the water extraction process, a green laser was focused across the path of the ejected water droplets, and photographs were captured using the burst mode of a digital camera with the shutter speed of 1/30th of a second (Fig. 4b, c). These experiments revealed that—differently from the conventional evaporation-driven extraction process—water is released in the liquid form, although droplets large enough to be captured by our camera are visually observable for only a few seconds after the onset of piezo actuation.

a A schematic and a photograph of the actuator, comprising a steel membrane acting as a Joule heater and an ultrasound-generating piezoelectric component (PZT ring). b,c Photographs of an HG-M sample on the actuator and of the water droplets ejecting under stimulation (scale bars 16 mm). d Desorption kinetics measured as a function of the HG-M moisture content (quantified as a total initial weight of the specimen soaked in water). e Desorption kinetics as a function of the sample geometry. f Desorption kinetics as a function of the transducer actuation frequency. g An IR image visualizing the Joule heating of the actuator operating at a 1.5 W power (applying ~114 Vpp) and a 110 KHz frequency. h,i The rate of water extraction and membrane temperature under piezo actuation (h) and Joule heating (i). The energy consumption is calculated and listed for each curve in (d–f) and (h,i).

We conducted four series of experiments to evaluate the role of the sorbent size, weight, moisture content, and nozzle size as well as the actuation frequency on the water extraction efficiency (Fig. 4d–f and Supplementary Fig. S17). First, HG-M samples of 3 mm diameter and 1 mm thickness were submerged in DI water for of 30, 60, and 120 s, respectively. The samples were weighed before being positioned in the center of the mesh membrane of a PZ-A actuator (7.8 mm diameter and 10 µm nozzle size). The wet samples having initial weights of 0.06, 0.07 and 0.11 g, respectively, were exposed to piezoelectric stimulation for 10 minutes, and their weight loss is reported in Fig. 4d as a function of time. The heaviest sample exhibited the best performance in terms of energy consumption (9.8 MJ/kg), about 35% lower than 15 MJ/kg value measured for the samples with lower moisture content. We attribute the observed improvement to the better contact between the vibrating mesh membrane and a heavier specimen.

Second, we studied the effects of both sorbent mass and geometry by testing specimens of varying sizes under the same actuation protocol. Samples with diameters of 3, 6, and 9 mm and thicknesses of 1 mm were submerged in DI water for 120 s each, and their weight loss kinetics under actuation are reported in Fig. 4e. The largest and heaviest ( ~ 0.4 g loaded weight) sample exhibited the lowest energy consumption of 4.8 MJ/kg. The plots in Fig. 4d, e indicate that (i) the energy consumption per unit mass of extracted water does not always correlate positively with the percentage of the sample weight loss under actuation, (ii) higher efficiency is achieved when the sample fully covers the actuator membrane, and (iii) heavier samples with higher moisture content exhibit higher energy efficiency. This suggests that the optimum sample weight (achieved for a certain geometry and moisture content) needs to be found to minimize the energy consumption, as extra-heavy samples can dampen the membrane vibrations, reducing extraction efficiency.

Third, we compared the extraction efficiency achieved by using different actuator membrane geometries (Supplementary Fig. S17). As expected, the PZ-C actuator with the nozzle size of ~100 µm demonstrated lower energy consumption (7.7 MJ/kg) than PZ-A (16.6 MJ/kg), while PZ-B actuator with the nozzle size of ~70 µm had performance similar to that of PZ-C. The increased energy efficiency of PZ-C actuator can likely be attributed not only to the higher diffusion rates (Fig. 3a) but also to the larger membrane displacement and higher velocity (Fig. 3b, c).

Finally, piezo actuators operating at different frequencies, PZ-C (107 KHz) and PZ-D (165 KHz) with similar nozzle numbers and sizes, were used to extract moisture from HG-M samples of 3 mm diameter and 1 mm thickness, after they were submerged in DI water for 60 s. PZ-D actuator exhibited the highest energy consumption of 25.2 MJ/kg, indicating that the operating frequency plays a very important role in the water release process.

For all the experiments in Fig. 4d–i, the piezo actuator was driven by using a miniaturized and portable printed circuit board (PCB) electronic driver system at a constant ~70% duty cycle (defined as the ratio of the time during which the system is in an activated state (ON) and the overall duration of each cycle that comprises a series of ON-OFF cycles). Our modeling predicts that the axisymmetric displacement and velocity in the out-of-plane vibrations of the membrane at an applied voltage of 40 Vrms or ~114 Vpp reach ~60 µm and ~45 m/s, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S18). At the same time, infrared imaging (see Methods) reveals that the actuator can exhibit a temperature rise of >20 °C within 60 s while working at 70% duty cycle and 1.5 W supplied power applying ~114 Vpp (Fig. 4g). It returns to the ambient temperature within a comparable time frame after actuation stops (Supplementary Fig. S19). This fast increase in temperature facilitates desorption of water from hydrogels50, and the combined effect of fast temperature rise and hydrogel vibration synergistically drive quick and efficient water release.

The rate of water extraction and the energy consumption of the piezo-actuation and Joule heating methods are compared in Fig. 4h, i. Both the Joule heater (a bare stainless-steel membrane) and the piezo actuator were powered with 1.5 W, and the weight loss process of DI water-loaded HG-Ms was measured for a period of 10 min. The samples were actuated for 1 min-long intervals and weighed after each minute, with both the weight loss and its derivative plotted in Fig. 4h, i. The bottom panels of Fig. 4h, i show the temperatures of the membranes measured by K-type thermocouple sensors, which were deliberately kept at the same level by choosing the 1 min-long actuation periods (see Methods). The piezo-actuated specimen regained its original weight within a span of 7 minutes under piezo actuation at 42 °C (Fig. 4h). In contrast, the sample subjected to water evaporation via Joule heating did not regain its initial dry weight even after 10 min at 41 °C (Fig. 4i). These data also revealed that the piezo-driven extraction consumed a significantly lower amount of energy (7 MJ/kg), a reduction of approximately 74% compared to the Joule-heater-induced evaporation (28 MJ/kg). A piezo actuation duty cycle can be further optimized to mitigate the generation of heat and increase efficiency58.

It is important to ensure that the sorbent maintains its structural integrity under a combination of mechanical and heat stimuli during the water extraction process. The inspection of HG-M specimens and the piezo membrane after multiple tests showed no visible damage on the hydrogel and no significant material residue left on the membrane, as evidenced by the SEM image (Supplementary Fig. S20). The very few nozzles that appeared jammed were easily cleared by rinsing the membrane with DI water, thereby enabling its repetitive utilization. Surface topography scans of the membrane also revealed a relatively even terrain (Supplementary Figs. S21-S22).

We used a hydrophone to measure the transmittance and attenuation of the ultrasound wave emitted from the actuator (see Supplementary Fig. S23) and passing through the hydrogel55 (Fig. 5a). Figure 5b illustrates the signal captured by the hydrophone while it is in contact with the hydrogel when the actuator is driven periodically, ON for 10 s, OFF for 5 s (see also Supplementary Movie 6). These measurements revealed increased acoustic wave attenuation in thicker hydrogel samples (as expected59) and for hydrogels with higher storage moduli (Fig. 5c). The HG-C hydrogel, with 100 times higher crosslinker content than HG-A, exhibits a much higher storage modulus and about the same loss modulus (\({G}_{A}^{{\prime} }=1098,{G}_{A}^{{\prime} {\prime} }=240;{G}_{C}^{{\prime} }=2855,{G}_{C}^{{\prime} {\prime} }=241\)), translating into higher attenuation of the ultrasound wave (Fig. 5c). HG-M hydrogel demonstrated a similar trend of the output voltage decrease with the increased thickness and stiffness (Supplementary Fig. S24). The COMSOL-simulated 2D image of the actuator-hydrogel system is shown in the inset for HG-A. It shows the high-intensity sound pressure level at the hydrogel-actuator interface, which attenuates away from the actuator surface. These observations are in agreement with prior studies of medical-grade hydrogels60.

a A setup for measuring transmittance and attenuation of acoustic waves propagating through hydrogel samples. A sample is placed between the actuator (transmitter) and a sensor (receiver), and the transmitted signal is measured as the output voltage. b Input and output voltages measured under periodic actuation of an HG-A sample. c The output voltage as a function of hydrogel stiffness and thickness. The COMSOL-simulated sound pressure level intensity (a.u.) in the hydrogel is shown in the inset for HG-A. d,e Water extraction rates from HG-A and HG-C gels and the corresponding energy consumption during ultrasonic actuation with 70% duty cycle. f Anomalous diffusion model describes the moisture extraction process under ultrasonic actuation. g,h Extraction rates and the associated energy costs during actuation with 30% duty cycle. i Cyclic stability of the desorption behavior of HG-A hydrogel. Scale bar: 16 mm.

Next, we compared the extraction efficiency of HG-A and HG-C samples with comparable weight (0.2 and 0.19 g, respectively) and equal moisture content equilibrated at ~80% RH (Fig. 5d, e). HG-A exhibited a higher weight loss of ~22% and energy consumption of ~12 MJ/kg under the 10-minute-long stimulation by the PZ-C actuator with ~114 Vpp and 70% duty cycle, while HG-C lost only ~12% of its weight and exhibited a much higher energy consumption of 21 MJ/kg under the same conditions. We fit the experimental data by using the Korsmeyer-Peppas (K-P) kinetic model, which establishes an exponential dependence of the fractional mass release on time \(t\) (see Methods): \(m(t)/{m}_{0}=k{{\rm{e}}}^{{nt}}\)61,62 (Fig. 5f). This model is commonly employed to analyze the release mechanism of pharmaceutical drugs from polymers, when more than one release phenomena are involved (\(k\) is a constant incorporating the sample structural and geometric characteristics, and the value of release exponent \(n\) quantifies the release process). The fitted values of the release exponent \(n\) were \(0.65\pm 0.1\) for HG-A \(0.82\pm 0.1\) for HG-C, indicating a swelling-controlled diffusion mechanism, rather than the Fickian (static) diffusion with \(n=0.45\)63.

The non-Fickian (dynamic) behavior observed in our experimental data can be characterized as an anomalous diffusion, and indicates the presence of an additional molecular relaxation process under a combined action of ultrasound, mechanical pressure, and heat64. A similar anomalous diffusion is observed for the ultrasound-triggered release of antibiotics from hydrogel carriers65. The ANOVA tests indicate that there is no statistically significant variance (\(p > \alpha=0.05\)) between the \(n\)-values of the K-P model fitting for HG-A and HG-C samples (Supplementary Fig. S25). However, a higher fitted n value for HG-C suggests that, owing to its high modulus, the water release mechanism in this hydrogel deviates further from the Fickian behavior than that in HG-A, translating into higher energy consumption. Supplementary Fig. S26 reveals the differences in the evolution of vibrational modes associated with both water molecules and polymer functional groups like methylene (-CH2-) and amino group (-NH2) during the sorption-desorption cycle, which underlie the differences in the relaxation process dynamics of hydrogels of varying stiffness.

To quantify synergistic and separate impacts of Joule heating and mechanical actuation on moisture extraction, we measured the moisture extraction rate in a cycle of periodic activation and deactivation of the PZ-C piezo-actuator (Fig. 5g, h). The plots reveal a persistent reduction of AWH-H weight even during the actuator off time periods, which indicates a temperature-driven water vapor release due to the high vapor pressure of the water in the hydrogel51. With this hybrid approach, we further increased extraction efficiency and reduced the energy consumption (to 10.2 MJ/kg and 12.4 MJ/kg for HG-A and HG-B, respectively). These data also reveal that increased mechanical rigidity of hydrogels reduces the rate of water release not only during the ultrasonic actuation but also by evaporation. The thermogravimetric analysis confirmed that when exposed to the same heating under the same environmental conditions, the stiffer HG-B and HG-C specimens released less moisture than HG-A (Supplementary Fig. S27). Despite the differences in the extraction efficiency, both HG-A and HG-C hydrogel samples exhibited consistent absorption and desorption cycles, indicating cyclic stability (Fig. 5i and Supplementary Fig. S28), while the intermediate-stiffness HG-B samples exhibited unstable performance (Supplementary Fig. S29) and were excluded from further analysis.

Comparative analysis of the data in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5d–i suggests that the water extraction process can be further improved by the duty cycle and sample size optimization. We used our complete assembled system shown in Fig. 1c-d (see also Supplementary Fig. S30 and Supplementary Movie 7) to probe extraction efficiency from HG-A and HG-C specimens of varying moisture content. HG-A specimens were equilibrated at 77% RH, and then actuated for 25 min with a duty cycle of ~30–32%, equivalent to 8.75 min of piezo actuation time. These experiments revealed the reduction of energy consumption down to 5.25 MJ/kg for a medium-heavy ( ~ 1.73 g) sample, which covers the entire surface of the membrane. Similarly, for HG-C hydrogel, the optimized energy consumption of 6.2 MJ/kg was achieved with a ~ 1.65 g specimen (Supplementary Figs. S31-32 and Supplementary Movie 7). Accordingly, the duty cycle needs to be optimized for environmental conditions, to compromise between the water harvesting amount per day and the corresponding energy consumption per unit mass of water.

To further optimize the system performance, we (i) reduced the actuation time to 2 min, (ii) performed a test using three identical actuators and samples simultaneously under 2 min extraction cycles (Supplementary Figs. S33-35), and (iii) tested a single large HG-A sample with a diameter of 34 mm under multiple consecutive 2 min extraction cycles (Fig. 6a, b). Under these optimized conditions, during each 2-minute-long extraction cycle in each of the tests, energy consumption was recorded to be below the thermal limit of 2.25 MJ/kg66, thus yielding extraction efficiency in excess of 100% (see Supplementary Note 5 for detail). Average energy consumption of 0.535 MJ/kg (corresponding to 428% efficiency) has been measured over ten 1 h-long sorption cycles run at 75% RH, separated by eleven 2 min-long ultrasonic extraction cycles (Fig. 6a). Figure 6a shows the extracted water mass and energy consumption for each extraction cycle. The lowest energy consumption of 0.47 MJ/kg (corresponding to 481% efficiency) was recorded during several cycles shown in Fig. 6a.

a, b Comparison of two strategies for water extraction from a large HG-A specimen ( >16 mm diameter): ten 1 h sorption cycles separated by 2 min- extraction periods (a) and 25 cycles of repeated 2 min extraction periods following one 24 h-long sorption cycle (b).c A comparative analysis of energy consumption between actuator-enabled water extraction and the state-of-the-art thermally driven evaporation process42. Here, si_l = a single device actuated over a long period; ar_l = an array device actuated over a long period; si_s = a single device actuated over a short period; ar_s = an array device actuated over a short period; si_s_m = a single device actuated over multiple short periods. d A comparative analysis of the daily water yield between the current work and previously reported state-of-the art AWH devices (the data is summarized in Supplementary Table 7). e, f Dynamic changes of HG-A (e) and HG-C (f) samples monitored in-situ through impedance-phase angle spectroscopy. g A schematic illustration of the machine learning model training on the measured impedance and phase angle data. The model uses a deep neural network for classification, which is shown in the confusion matrix.

In contrast, when the 2 min actuation cycles have been run consecutively, without allowing for the sorption period in between, the energy consumption progressively increased with the cycle number, while the amount of the extracted water reduced. The lowest average energy consumption of 0.336 MJ/kg (corresponding to 671.1% efficiency) has been recorded for the first extraction cycle from the largest 34 mm-diameter sample (Fig. 6b). Both, energy consumption and extracted water mass values plateaued after about 20 extraction cycles equivalent to 40 min of continued actuation (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6c summarizes the extraction efficiencies recorded under different actuating cycles and with different sorbent samples described above and compares these values to those of the highest-efficiency AWH setups reported in prior literature. Recent thermodynamic models of thermally-driven atmospheric water extraction predict the highest realistic thermal efficiency of 60%, corresponding to thermal energy consumption to 3.75 MJ/kg45. Real-world devices demonstrate even lower efficiencies, with the highest recorded efficiency of 10%67, and the currently achieved minimum energy consumption of 22.5 MJ/kg. In stark contrast, the average energy consumption and efficiency over ten sorption-extraction cycles were measured to be 0.535 MJ/kg and 428%, respectively (Fig. 6c), because the ultrasonic extraction process is not fundamentally restricted by the thermal limit inherent to evaporation-driven techniques.

Discussion

The data in Fig. 6a shows that by using ultrasound desorption mechanism, the total daily water yield is almost entirely constrained by the sorption rate. PAM-LiCl hydrogels used in this work adsorb the same amount of moisture from air with 75% RH in 40 min as can be extracted by piezo actuation in 2 min. We can estimate the daily yield of water that can be harvested from a scaled-up system with a 1-m2 sorbent area [L/m²/day] by extrapolating the results of cyclic sorption-desorption testing of a single prototype device with a large sorbent over 10 h at 75% RH, i.e., by using the data shown in Fig. 6a. This simple scaling strategy assumes that multiple identical actuators with hydrogel samples identical to those used in our study are deployed in the form of a two-dimensional (2D) horizontal array with the total area of the sample surface equal to 1 m2. We further assumed that each actuator is powered separately and the energy consumption per device is the same as measured in our experiments. Under such assumptions, the average daily productivity value is predicted to be ~3.25 L/m²/day and an average energy consumption of 0.576 MJ/kg (Supplementary Note 5).

It should be emphasized that ultrasonic extraction does not require exposing sorbent surface to sunlight. Accordingly, AWH devices can be stacked vertically on top of each other with no limitation in principle to the number of vertical rows. Adding more 2D device arrays by stacking them vertically will increase the yield by 3.25 L day⁻¹ per each row without increasing the installation horizontal footprint. For instance, using an installation with 5 vertical rows of devices, the productivity of our system can be increased fivefold to 16.25 L day⁻¹ per m2 of land footprint. Figure 6d and Supplementary Table 7 compare the estimated productivity of our system with those of previously reported AWH materials and systems. Replacing PAM-LiCl hydrogels with sorbents exhibiting higher sorption rate (such as e.g., a hygroscopic interconnected porous gel68) can further increase daily yield.

Vertical stacking or vertical arrangement of sorbents have already been used in the state-of-the-art AWH systems with thermal extraction to increase per-m2 yield68,69. However, except for the vertically oriented sorbent setup employing integrated Joule heaters69, such installations require either manual batch processing of sorbent layers or conveyor-belt-like rotating sorbents to achieve solar exposure for thermal extraction.

Remarkably, the lowest energy consumption of 0.336 MJ/kg (0.09 kWh/kg) per a single cycle measured in this work (Fig. 6b) is not only below the ideal thermal limit, but also below the dewing limit at 75% RH. Dewing limit defines the ideal minimum energy consumption of conventional dehumidification technologies, which cool air to its dewing point to promote water condensation (Supplementary Note 6). At 75% RH and ambient temperature of 25 °C, the minimum energy required for dewing is 0.58 MJ/kg (0.16 kWh/kg).

Our preliminary technoeconomic analysis of the scaled-up system performance indicates the viability of commercializing our system. The estimated cost of water extracted from air at 75% RH is 0.19 $/L, which is lower than the cost of bottled water in various countries worldwide, including USA, UK, Canada and Australia (see Supplementary Note 7 and Supplementary Figs. S36-37). Supplementary Fig. 37a illustrates that—owing to the low cost of hydrogel—its lifespan does not have a noticeable effect on the water costs, while Supplementary Fig. 37b shows the estimated water costs as a function of the device lifespan in the range from 1 to 45 years.

Given the observed dependence of the extraction energy efficiency on the sample moisture content, in-situ monitoring and dynamic optimization of the sorption-extraction cycle under variable environmental conditions could help to improve the system performance during the field operation. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) may be used to monitor the changes in the sorbent properties (Supplementary Note 3, Supplementary Fig. S26, and Supplementary Table 3), but it cannot be deployed for continuous in-situ monitoring. Fortunately, the piezoelectric actuator itself can be used not only for moisture extraction but also for real-time process monitoring. Piezoelectric materials exhibit both direct and inverse piezoelectric effects, translating into their ability to either convert applied force into measurable electric quantity or convert electric potential into quantifiable displacement, respectively70. By taking advantage of the direct piezoelectric effect, the actuator can be used as an in-situ sensor71,72. This sensing capability is illustrated in Fig. 6e, f, which show changes in the impedance ( | Z | , Ω) and phase angle ( | θ | , o) of a PZ-C actuator loaded with either HG-A or HG-C hydrogel during the process of atmospheric moisture adsorption at ~20% RH and 20 °C.

To evaluate the potential of using this sensing modality for continuous in-situ monitoring and control of the sorption process, we developed a deep learning model and demonstrated its capability to recognize absorption patterns of different hydrogels (Fig. 6g). Impedance variations datasets were collected during atmospheric moisture absorption cycles at ~20% RH and 20 °C. We used 77% of all the datasets for training and the rest 23% for testing. Following 200 epochs of training, the model successfully classified the impedance data and was able to distinguish between absorption patterns of HG-A and HG-C hydrogels, achieving an impressive prediction accuracy of 100% as shown in the confusion matrix (Fig. 6g). This monitoring and classification capability shows promise in designing fully automated systems that can switch from sorption to extraction once the optimum conditions are reached. Combining embedded sensing capability with deep learning tools for real-time data classification will allow for identifying abnormalities in the system performance and adjusting the system operation to the changes in the environment.

This study demonstrated moisture extraction by vibrational actuation with high efficiency from two different hydrogel systems. These results give reason to expect that ultrasound actuation can facilitate moisture extraction from other sorbents. This hypothesis is independently supported by literature evidence on increased drying rate of textiles73, seaweed74, and zeolite75 under ultrasonic actuation. Each material system would need to be evaluated separately under optimized actuation conditions, moisture content, and sorbent geometry, which will be the subject of our future work. Under this non-thermal extraction scenario, the kinetics of both the sorption and desorption processes under the optimized vibrational actuation for each type of sorbent will play an important role.

Accordingly, the known sorbents, including various types of hydrogels, metal-organic frameworks, micro- and nano-fiber mats, and combinations thereof, will need to be re-evaluated and re-engineered to enhance their compatibility with the alternative extraction method. Internal nano- and micro-scale structure of sorbents will further play an important role in the efficiency of this process and needs to be investigated (e.g., size and shape of the pores, surface-to-volume ratio, stiffness, etc). The overall shape of the sorbent sample can be engineered to provide acoustic resonances matched to the actuator driving frequencies. Finally, each sorbent may exhibit its overall highest efficiency when actuated not only by a different frequency but also around a different point in its sorption curve, calling for further fundamental studies and optimization efforts.

Scaling up this alternative extraction technology will necessitate further research into ultrasound-induced degradation of various sorbent materials. The robustness, cyclic stability, and efficacy for long term water harvesting capability of PAM-LiCl HG-A hydrogel composites have been previously demonstrated in numerous works30,32,46. Our initial lab-scale testing confirms that these sorbents maintain structural integrity after multiple piezo actuation cycles, as evidenced by absence of any traces of polymer residue in collected water filtered by a VWR filter paper (see Supplementary Notes 5,8). Our observations and spectroscopic analyses (Supplementary Fig. S26) also agree with prior independent studies of polymers and hydrogels subjected to piezo actuation, which have demonstrated resilience to vibrational deformations76,77 and self-healing performance78. Similarly, in this work, we did not observe any material degradation or performance loss of either HG-A or HG-M hydrogels during multiple actuation cycles (Fig. 6a, b and Supplementary Figs. S28 and S35). The degradation resistance of other sorbents will need to be evaluated separately. Some may prove incompatible with this method of extraction, others may need to be re-engineered to improve their mechanical properties so they can withstand vibrational forces over many regeneration cycles.

It should also be noted that a traditional photothermal method of moisture extraction from sorbents also causes their accelerated degradation. For example, solar radiation causes rapid UV-triggered photooxidative degradation of polymers via chain scission and formation of free radicals79,80, which for some polymers is further accelerated in the presence of moisture and at higher temperatures81,82,83. Prior studies demonstrated that 368 nm UV irradiation can effectively degrade hydrogels84. Likewise, MOFs may also deteriorate under UV and sunshine exposure85. Even when the sorbents themselves are not directly exposed to sunlight during the moisture extraction process, long exposure of solar absorbers and constructional elements of the AWH system to sunlight, high temperatures, and moisture accelerate their ageing. Long-term studies of sorbent degradation under various stimuli (sunlight, moisture swings, temperature swings, and ultrasound signals) will need to be done for any sorbent considered for outdoor AWH operation to evaluate their lifetimes under different operational scenarios in real-life applications.

The manufacturer-indicated lifespan of piezoelectric actuators used in this study86 is 45 years. In prior studies, the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory conducted life testing on commercial piezoelectric PZT actuators, pre-stressed to 18 MPa, for up to 100 billion cycles over 580 days, revealing no discernible damage or substantial performance decline87. Several strategies can be additionally implemented to preserve long lifespans of actuators used in AWH systems. A waterproof silicon-based membrane may replace the metal membrane in the actuator used in this study, maintaining a comparable displacement and velocity profile52. Silicon coating over metallic or other corrosion-prone elements can be used to enhance corrosion resistance88. Alternatively, corrosion-resistant ultrasonic transducers can be used, e.g., those based on monocrystal fibers89,90 or on hydrophobic polymers such as polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)91.

Salt-containing sorbents like the LiCl-infused hydrogels HG-A,B, and C used in this work may present additional challenges associated with water extraction in the liquid form under ultrasonic actuation. Measured Li ion concentration in the extracted water varied between 1.5 and 15.2 ppm (or mg/L), comparable to the concentrations measured a recent study of bottled water in multiple countries (see Supplementary Note 7). While there are no regulatory thresholds for lithium either in the USA or globally, our future work will focus on the synthesis and testing of Li-free sorbents with high water uptake to limit the risk of water contamination and to reduce the cost of the technology. It is important to emphasize that the alternative extraction methodology is equally applicable to Li-free hydrogels (such as e.g., HG-M gels shown in this work) and is expected to be fully compatible with other previously demonstrated sorbents that do not contain salts.

In our devices, we estimate the energy consumption to be roughly equally divided between the mechanical actuation (49%) and heating (51%), see Supplementary Note 10. The parasitic heat generated by a piezo actuator is used to heat a sorbent, and still contributes to the water extraction, but with lower efficiency than mechanical actuation. The effective electromechanical coupling coefficients of our prototype actuators was quite low, ranging from 17 to 19%. By designing a 1-3 composite piezoelectric transducer array device instead of a single ring-shaped actuator, an electromechanical coupling coefficient of 35% can be achieved92. High-efficiency single-crystal piezoelectric materials exhibit even significantly higher electromechanical coupling factors, which can be complemented by the optimized transducer array design, promising further efficiency enhancement.

Furthermore, arraying small devices is not the most efficient way of scaling the system up, which likely overestimates the daily energy consumption while underestimating the energy efficiency of extraction. The effectiveness of large-area PZT-based ultrasound transduction has been demonstrated in various unrelated studies. For example, an interconnected network comprising hundreds of miniaturized PZT actuators has been employed over a 20 cm x 20 cm area, utilizing only 6 W of electric power, resulting in efficient transduction intensity at a depth up to 8mm93. Similarly, larger piezoelectric components could be utilized in arrays, akin to those employed in sonar applications for underwater wireless communication, which are inherently designed with a larger footprint area extending up to several sq. feet94. Future research could implement these strategies to test the AWH sorbents with a custom-made actuator array over a large surface area and associated electronic circuits for optimum power supply to the array, which may yield higher energy efficiency than we predict based on the simple approach described above.

The vibrational extraction requires the use of a photovoltaic (PV) cell—or another solar-to-electricity energy converter—to generate electric power to drive a piezo actuator if operated autonomously without access to the electric grid. While solar power can be used to directly heat a sorbent material, there are multiple arguments for the use of a PV cell to convert and store solar energy to power an outdoor AWH system (even if ultrasonic extraction is not used). First, conversion of solar energy into low-grade heat in a solar-thermal absorber is a less efficient process than conversion of solar energy to electricity with a PV cell (see Supplementary Note 11)95,96,97. Second, the daily water yield per land area can be maximized by designing vertically-oriented systems68,69 integrated with ultrasonic actuators or Joule heaters for extraction, and by optimizing the sorption-desorption cycle duration to operate around the clock. Third, other auxiliary devices can be powered by the PV-generated electricity, including sensors to monitor environmental conditions and fans to promote air convection to improve vapor diffusion68,98. Finally, AWH systems with vibrational extraction can be designed to run autonomously, avoiding manual batch-drying process98 and adapting their sorption/extraction cycles to varying environmental conditions.

To summarize, our work offers the experimental demonstration of the energy consumption of moisture extraction from AWH sorbents below both the thermal limit and the dewing limit. This major improvement in energy efficiency may promote AWH technology commercialization.

Methods

Hydrogel synthesis

We synthesized polyacrylamide hydrogels based on a simple, one-pot approach, where polymer, salt, initiator, crosslinker, and accelerator, were all mixed in water. For all hydrogels, we first dissolved the 16.72 g lithium chloride ( ≥99%) salt in a beaker with 50 mL deionized (DI) water. The solution was continuously mixed with a magnetic stirring bar, covered to prevent evaporation, and then left to cool down to room temperature. We added sequentially 4.18 g of acrylamide ( ≥ 99%), the N,N’-MBA (99%) as crosslinker (50 mg for HG-C, 2.5 mg for HG-B and 0.5 mg for the HG-A) and 14.2 mg of ammonium persulfate (APS) ( ≥ 98%) as initiator. We degassed the mixed solution for 10 min under vacuum in a dessicator. Finally, we added 12 μL of N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylendiamin (TEMED) ( ≥ 99%) as accelerator. 4 mL of solution were poured into a petri dish, covered with the lid, and left to gelate at room temperature overnight. All the chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received.

Sorption evaluation

The dynamic vapor sorption isotherms were characterized using an environmental simulation chamber (BINDER GmbH). Initially, the samples were dried at a temperature of 95 °C, for a duration of 24 hours using a gravity convection oven (MTI Corporation). Subsequently, the weight of the samples that had been dried in the oven was measured using an analytical balance (OHAUS Corporation). Next, the oven-dried samples were treated inside the environmental chamber under varying RHs (15, 30, 55, 85%) at a constant 25 °C temperature and at a maximum stage time of 720 min, ensuring that the specimen weight reached an equilibrium state. In addition to our designed hydrogel, we also used a commercially available hydrogel (HG-M) (a cross-linked glycerol- 2-acrylamido-2-methylpropanesulfonic acid sodium salt hydrogel, Medela). Finally, the water uptake was quantified by calculating the ratio of the water content in the sample at equilibrium to its oven-dried weight. The findings are shown as the mean ± standard deviation.

Oscillatory shear rheology characterization

Rheological experiments were conducted using a rheometer (HR-20, TA Instruments). For all the experiments, a 25 mm parallel plate geometry was employed to ensure accurate loading on the hydrogel specimens. A circular mold was used to fabricate gelled disks, which were formed into a diameter of 25 mm for utilization underneath the parallel plate. Before conducting the tests, the samples were given a five-minute period to reach a state of equilibrium, ensuring that both mechanical and thermal factors were balanced. The temperature was controlled using a built-in Peltier system. The experiments involving the oscillatory frequency and strain/amplitude sweeps were carried out at 25 °C. Temperature sweep experiments were conducted at an angular frequency of 6.28 rad/s and 0.1% strain.

Thermal analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis was conducted to evaluate the desorption behavior and thermal stability of the hydrogels using a thermal analysis system (TGA 5500, TA Instruments). Approximately 10 mg of samples were put into a titanium pan in the presence of nitrogen gas and were heated gradually at a rate of 1 °C/min until they reached a temperature of 50 °C.

Surface morphology

The surface morphology of the hydrogel specimens was examined using an SEM (Zeiss Sigma 300 VP). Hydrogels were completely dehydrated to prevent off-gassing during sputtering and SEM imaging. To prepare the samples and visualize them under the SEM, they were stuck to aluminum stubs with double-sided carbon tape. Next, a sputter coater (Desk V, Denton) was used to apply a 10 nm thin film coating of gold/palladium (Au/Pd) (60:40) in presence of argon gas.

Forward-osmosis test for water permeability study

A conventional diffusion cell was used to conduct the forward osmosis test and assess the efficacy of water penetration through the porous stainless-steel membranes employed in this investigation. The experimental configuration closely resembled a recent study99. The porous membrane was installed between two glass cells, each having a capacity of 7 ml. The left cell is referred as the NaCl-solution cell, and the right one is the DI-water solution cell, (see Supplementary Fig. S8). A 2 M NaCl solution was made by dissolving 0.81 g of NaCl in 7 ml of DI water. The right cell contained 7 ml of DI-water with conductivity in the µS (micro-siemens) range. As the water conductivity increased, reaching the mS (milli-siemens) range, the ion mass began to transport through the membrane from the ion-cell to the DI-cell. This occurred under vigorous mixing at a speed of 1350 RPM at room temperature, driven by the concentration gradient. The conductance measurements were conducted using a conductivity probe (SevenCompact, Mettler Toledo) for a duration of 10 minutes for each of the three SS membranes.

Piezoelectric ultrasonic device architecture

The solid housing for the piezoelectric transducer was modeled in SOLIDWORKS and parts were printed using a Bambu Lab X1-Carbon Combo 3D printer. Aside from the glass domes, all parts within the assembly have a hole with a 12 mm diameter in the center to allow droplets to fall into the bottom dome since water can be harvested from the hydrogel on both sides (top and bottom) of the piezoelectric transducer. Two-ring structures, top and bottom insulators, are used to hold two glass domes in place. Cuts are made into the assembly to allow the domes to slide into the case. The top insulator is 8 mm tall, has an outer diameter of 33 mm, and an inner diameter of 25 mm, allowing for a perfect fit of the glass dome, which had an outer diameter of slightly below 25 mm. The wire track that houses the piezoelectric device is 8 mm tall and has an outer diameter of 20 mm and an inner diameter of 17 mm. Also, it has a cut that is 2 mm deep to hold the piezoelectric ring and provides a cavity to allow wiring and ambient moisture access into the case. The support platform connects the top and bottom insulators. The bottom insulator and the tripod together host the bottom glass dome. Each leg of the tripod is 38 mm long.

The piezoelectric transducer used in our system was circular in shape (see Supplementary Table 1-2 for detail), where a piezoelectric ring made of lead zirconate titanate (PZT) polycrystal was affixed to a porous stainless-steel membrane. To fabricate the transducer for our system, the membrane and the PZT rings were purchased from Dongguan Norvis Electronic Corporation and securely fastened. The PZT was affixed to the porous membrane by clamping one side, while the other side was covered with a hydrophobic epoxy resin. Porous membranes with three different nozzle sizes (10, 70, and 100 µm) were used with PZT crystals of two different frequencies to build the low ( ~ 110 kHz) and high ( ~ 165 kHz) frequency actuators. Piezo drivers were used to actuate the transducer at two different duty cycles of 70 ± 3% and 30 ± 3%, operating at RMS voltages of 40 and 30 V, respectively. The driver boards were powered at 1.5 W using a DC power supply to drive the piezoelectric transducers.

Piezoelectric charge coefficient d33 measurement of the piezoelectric materials

A Berlincourt meter was employed to measure the piezoelectric coefficients, d33 (pC/N), of the PZT crystals used in fabricating the four transducers. During the measurement of the coefficients, both a static force and a dynamic force are exerted on the sample. The tool controls and maintains a constant dynamic force of 0.25 N/110 Hz, while the static force of around ~1 N was manually controlled. The static force is measured using a static force sensor to assure consistent measurements (see Supplementary Fig. S41 for experimental setup).

Electrical impedance, resonant spectra, and electromechanical coefficients of piezo transducers

The electrical phase-impedance spectrum of the transducer devices was measured using an impedance spectroscopy (Solartron SI 1260, AMETEK). The impedance spectrum was screened to obtain two key parameters, the anti-resonance (fa) and resonance (fr) frequencies. The evaluation of the effectiveness of piezoelectric devices in converting electric energy into mechanical energy was conducted based on their effective electromechanical coupling coefficient (keff)56,92 using the following equation: \({k}_{{eff}}=\sqrt{({f}_{a}^{2}-{f}_{r}^{2})/{f}_{a}^{2}}\).

Modal, deflection, and velocity analysis of ultrasound devices

The vibrational modes of the steel membrane and PZT ring were analyzed using a PICOSCALE Vibrometer (SmarAct Metrology GmbH & Co. KG), which is a laser scanning vibrometer employing confocal optics and Michelson interferometry. The sample was actuated using the built-in signal generator of the vibrometer. In this case, the device was connected to a general-purpose input/output (GPIO1 from the vibrometer controller), which is used to output an electrical signal and directly feed it to the device using an adapted BNC cable.

First, microscopic imaging was used to identify the specific area of interest on the membrane and PZT ring for the modal analysis (see Supplementary Fig. S42). The membrane was analyzed at two distinct locations: the core and the periphery. Measurements on the periphery of the membrane and PZT were consistently conducted at a significant distance from the electrode cable. To uncover the local resonances, a linear sweep excitation ranging from 1 Hz to 500 kHz, with a duration of 0.01 s and an amplitude of 1 Vpp was generated and output via the GPIO1. For each identified local resonance, a 2D modal analysis was performed. During this analysis, the interferometric laser beam is raster-scanned over the sample while the amplitude and phase of the vibrations are extracted using dual-phase lock-in demodulation.

For this application, a single-frequency sinusoid is output at GPIO1, which is also used as the reference signal for the lock-in amplifier. The recorded time series is post-processed using the FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) algorithm to convert the signal from time domain into frequency domain in the form \(x\left(t\right)=A\sin (\omega t)\) to reduce the noise and reveal the resonances. The velocity (\(v\)) of the device at its resonance frequency (\({f}_{d}\)) was then calculated as \(v={dx}/{dt}=\omega \cdot A\cdot \cos (\omega t)\), where \(x\) is the displacement signal and \(\omega\) is the angular frequency. Maximum velocity value is then estimated as \({v}_{\max }=\omega \cdot A=2\pi {f}_{d}A.\) The amplitude A of the signal can be easily retrieved by performing the Fourier analysis of the recorded time-series, and the RMS value of the velocity at the peak amplitude value is calculated as \({v}_{{RMS}}=0.7{v}_{\max }.\)

In the case of a linear sweep excitation, the energy of the signal is spread over a large bandwidth. In order to retrieve the real amplitude of the motion, a correction factor is applied: \(k=\sqrt{({f}_{1}-{f}_{0}){dt}}\), where \({f}_{1}\) and \({f}_{0}\) are the highest and the lowest frequencies, respectively, and \({dt}\) is the duration of the sweep. In our calculations, a correction factor of \(k=70.71\) was used. During the experimental analysis and 2D imaging of vibrational modes, the displacement signal is demodulated on-the-fly using a digital dual-phase lock-in amplifier, and no correction factor to retrieve the actual amplitude is needed. The resulting 2D image of the sample deflection is post-processed to retrieve the maximum displacement value.

Elemental mapping, surface roughness imaging, and atomization photography

Elemental mapping, surface roughness imaging, and atomization photography Zeiss Sigma 300 VP was used to capture SEM images of the membrane nozzles and PZT material. The tool also employed Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) technology for elemental mapping of the PZT devices and provides precise information about their composition. A laser scanning confocal microscope (VK-X250, Keyence) was used to do non-contact surface profiling and roughness assessment of the membrane after the extraction cycle. The Nikon D5300 DSLR camera was used to capture the atomization process of water as it was expelled from the hydrogel and funneled through the nozzles of the porous membrane incorporated into the transducer. A green crossline was generated using a 520 nm green laser module (OXLasers), with the focal point positioned below the nozzle axis. This improved the process of envisioning for photography. T-slotted aluminum extrusions were used to build a platform for mounting the transducer between two L-shaped joint brackets to perform imaging experiments.

Infrared imaging

To monitor and visualize hydrogel heating caused by the PZT transducer heat generation, an infrared (IR) thermal camera (FLIR ETS320, Teledyne FLIR LLC) was utilized. IR imaging was also used to monitor the process of hydrogel cooling to ambient temperature after the actuation process. Due to the challenge of IR-imaging a highly polished surface such as a metallic stainless-steel membrane in our device, we used Dr. Scholl’s™ spray to deposit a thick opaque layer onto the membrane, and during imaging, emissivity (ε) value of 0.95 was set in the IR camera.

Ultrasonic radiation sensitivity

We used an acoustic sensor hydrophone (H Instruments) to measure and quantify the force exerted by a piezoelectric transducer as a function of voltage (V). To conduct the acoustic experiment, the transducer was placed within a petri dish and the hydrogel samples were attached to the device. The acoustic sensor was linked to its amplifier board operating at 9 V that had a gain of 25 dB with bandwidth up to 120 kHz and placed on the hydrogel surface. The transmitted and received waveforms were recorded. Our device served as the transmitter, while the acoustic sensor functioned as the receiver. The resulting output voltage was measured for hydrogel samples of varying thickness.

Comparative weight-loss study between Joule heater membrane and the transducer

We used a multi-channel calibrated commercial K-type thermocouple (HT-9815, RISE PRO) to measure the temperature of a free-standing (i.e., not clamped to the PZT) stainless steel membrane used as the Joule heater. The transducer device received a power supply of 1.5 W in order to maintain a consistent temperature for a comparative analysis. Throughout the experiment, either Joule heating or ultrasonic actuation were applied for 1 min each, followed by a subsequent short deactivation period to weigh the amount of weight loss. The weight loss (%) of the hydrogel was calculated by comparing the extracted mass to the initial mass of the sample.

Vibrational spectra of wetted hydrogels

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was used to investigate the changes in the vibrational spectra of hydrogels with different level of cross-linking and varying moisture content. FTIR with a built-in attenuated total internal reflectance (ATR) capability was used (iS50, ThermoFisher). The raw FITR spectra were deconvoluted into distinct Gaussian peaks corresponding to individual vibrational modes of polymer and trapped water molecules.

Energy consumption and efficiency calculation

The energy consumption, E [MJ/kg], required for moisture extraction was calculated as follows: \(E=P/m=(({\rm{power}},{kWh})\cdot ({duty\; cycle},\%) \cdot 3.6\cdot {10}^{6}\cdot {10}^{-6})/{10}^{-3}\left[\right.{MJ}\cdot {{kg}}^{-1} > \), where \(P\) is input energy [MJ], and \(m\) [kg] is the extracted mass. Using the energy consumption (E), the efficiency of the water release process of our device, \(\eta > \), is calculated as \(\eta={h}_{{lv}}/E\), where \({h}_{{lv}}=2.257\left[\right.{\rm{MJ}}/{\rm{kg}}\) is the enthalpy of vaporization of water (see Supplementary Note 4).

Li content test of extracted water

Agilent 5100 DVD was used to test the quality of the ultrasonically-extracted water from PAM-LiCl hydrogels via a coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) elemental analysis, similar to the test methods reported in recent studies of AWH hygroscopic gels30. Prior to testing with the Agilent 5100 DVD, the extracted water was collected using VWR sterile syringe filters. Multiple desorbed specimens were tested.

3D electromechanical finite element modeling (FEM)

COMSOL Multiphysics® was used to simulate vibrational modes of the transducer device consisting of a PZT ring clamped to a steel membrane with nozzles100. Solid Mechanics and Electrostatics modules were used to study the deformation dynamics, and a 3D asymmetrical model was constructed to facilitate visualization (see also Supplementary Note 2). Using a voltage sweep, the displacement and velocity were studied, and the phase-impedance spectrum was analyzed employing a frequency sweep. Simulating the nozzle dispersion pattern akin to the manufactured membrane proved challenging in COMSOL. Consequently, all the nozzles were uniformly distributed, and a diameter of 50 μm was used to accommodate around 800 nozzles. The simulation results for impedance, velocity, and displacement exhibited a high degree of agreement with the experimental data, without significant deviation. This simulation technique was also employed to visualize the behavior of ultrasonic radiation in hydrogel. For this study purpose, the Young’s modulus (E) was determined from the storage modulus of our hydrogel utilizing the formula \(E=2G(1+\mu )\), where \(\mu\) represents the Poisson ratio and storage modulus was used as the magnitude for \(G\). The density was estimated at approximately 1200 kg/m3 according to literature101, and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.5 is often employed for hydrogels. Following the calculation, the inputs were entered into COMSOL to simulate the sound pressure induced by the actuator in the hydrogel volume.

Deep neural network for the extraction dynamics monitoring

We used Edge Impulse machine learning platform102 to build a deep neural network, which was used to categorize and distinguish between different types of hydrogels during the sorption process. The neural network was trained using the measured dynamic changes in the phase angle and impedance of the transducer loaded with hydrogel samples, which were continuously sorbing moisture at ~20% RH and ~19 °C. The trained model has three hidden layers, with a total of 100 neurons, and exhibited accuracy of 100%. The training phase used 77% of the datasets, while the remaining 23% were allocated for testing the model.

Data availability

The data supporting the plots within the main text are available in Supplementary Information. Additional data relevant to this study are available from the authors upon request.

References

Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2, e1500323 (2016).

Elimelech, M. & Phillip, W. A. The future of seawater desalination: energy, technology, and the environment. Science 333, 712–717 (2011).

Shannon, M. A. et al. Science and technology for water purification in the coming decades. Nature 452, 301–310 (2008).

Estrela, M. J., Valiente, J. A., Corell, D. & Millán, M. M. Fog collection in the western Mediterranean basin (Valencia region, Spain). Atmos. Res. 87, 324–337 (2008).

Hou, Y., Chen, Y., Xue, Y., Zheng, Y. & Jiang, L. Water collection behavior and hanging ability of bioinspired fiber. Langmuir 28, 4737–4743 (2012).

Ju, J. et al. A multi-structural and multi-functional integrated fog collection system in cactus. Nat. Commun. 3, 1247 (2012).

Olivier, J. & de Rautenbach, C. The implementation of fog water collection systems in South Africa. Atmos. Res. 64, 227–238 (2002).

Park, K.-C., Chhatre, S. S., Srinivasan, S., Cohen, R. E. & McKinley, G. H. Optimal design of permeable fiber network structures for fog harvesting. Langmuir 29, 13269–13277 (2013).

Wang, Y. et al. Biomimetic water-collecting fabric with light-induced superhydrophilic bumps. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 2950–2960 (2016).

Zhang, L., Wu, J., Hedhili, M. N., Yang, X. & Wang, P. Inkjet printing for direct micropatterning of a superhydrophobic surface: toward biomimetic fog harvesting surfaces. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 2844–2852 (2015).

Schneider, S. H., Root, T. L. & Mastrandrea, M. D. No Title. Encycl. Clim. Weather.

Kim, H. et al. Water harvesting from air with metal-organic frameworks powered by natural sunlight. Science (80-.). eaam8743. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.AAM8743 (2017).

Li, R., Shi, Y., Shi, L., Alsaedi, M. & Wang, P. Harvesting Water from Air: Using Anhydrous Salt with Sunlight. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 5398–5406 (2018).

McHugh, T. A., Morrissey, E. M., Reed, S. C., Hungate, B. A. & Schwartz, E. Water from air: an overlooked source of moisture in arid and semiarid regions. Sci. Rep. 5, 13767 (2015).

Nandakumar, D. K. et al. A super hygroscopic hydrogel for harnessing ambient humidity for energy conservation and harvesting. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 2179–2187 (2018).

The UN World Water Development Report: Water for a Sustainable World. UN World Water Dev. Rep. Water a Sustain. World (2015).

Zhou, X., Lu, H., Zhao, F. & Yu, G. Atmospheric water harvesting: a review of material and structural designs. ACS Mater. Lett. 2, 671–684 (2020).

Boriskina, S. V. et al. Nanomaterials for the water-energy nexus. MRS Bull. 44, 59–66 (2019).

Wahlgren, R. V. Atmospheric water vapour processor designs for potable water production: a review. Water Res 35, 1–22 (2001).

Wikramanayake, E. D., Ozkan, O. & Bahadur, V. Landfill gas-powered atmospheric water harvesting for oilfield operations in the United States. Energy 138, 647–658 (2017).

Kim, H. et al. Adsorption-based atmospheric water harvesting device for arid climates. Nat. Commun. 9, 1191 (2018).

Nilsson, T. Initial experiments on dew collection in Sweden and Tanzania. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 40, 23–32 (1996).

Guan, H., Sebben, M. & Bennett, J. Radiative- and artificial-cooling enhanced dew collection in a coastal area of South Australia. Urban Water J. 11, 175–184 (2014).

Ji, J. G., Wang, R. Z. & Li, L. X. New composite adsorbent for solar-driven fresh water production from the atmosphere. Desalination 212, 176–182 (2007).

Wang, J. Y., Liu, J. Y., Wang, R. Z. & Wang, L. W. Experimental investigation on two solar-driven sorption based devices to extract fresh water from atmosphere. Appl. Therm. Eng. 127, 1608–1616 (2017).

Chua, H. T., Ng, K. C., Chakraborty, A., Oo, N. M. & Othman, M. A. Adsorption characteristics of silica Gel + Water Systems. J. Chem. Eng. Data 47, 1177–1181 (2002).

Wang, Y. & LeVan, M. D. Adsorption equilibrium of carbon dioxide and water vapor on zeolites 5A and 13X and silica gel: pure components. J. Chem. Eng. Data 54, 2839–2844 (2009).

Desai, R., Hussain, M. & Ruthven, D. M. Adsorption of water vapour on activated alumina. I —- equilibrium behaviour. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 70, 699–706 (1992).