Abstract

Semiconducting transition metal dichalcogenide (TMDC) moiré superlattices provide an unprecedented platform for manipulating excitons. The in-situ control of moiré excitons could enable novel excitonic devices but remains challenging. Meanwhile, as dipolar composite bosons, interlayer excitons in the type-II aligned TMDC moiré superlattices exhibit strong interactions with fermionic charge carriers. Here, we demonstrate active manipulation of exciton diffusivity by tuning their interplay with correlated carriers in moiré potentials. When electrons form Mott insulators, the interlayer exciton energy is blueshifted due to strong electron-exciton repulsion, leading to the enhancement of diffusivity by as much as two orders of magnitude. In contrast, exciton diffusivity is suppressed at fractional fillings, where carriers form generalized Wigner crystals. In between fractional fillings, electrons populate all moiré traps, resulting in enhanced diffusivity with increasing carrier density, owing to the effectively reduced moiré potential confinement experienced by excitons. Our study inspires further engineering and controlling exotic excitonic states in TMDC moiré superlattices for fascinating quantum phenomena and novel excitonic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transition metal dichalcogenide (TMDC) moiré superlattices offer unprecedented opportunities not only for engineering electronic structures1,2,3,4,5 but also for enabling new excitonic states6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15, where a periodic potential landscape with desired periodicity and potential profile can be designed to control exciton motion and even form exciton superlattices. However, active control of exciton motion, critical for eventual device applications, often requires in-situ tunability, such as tunable twist angle16,17, which is challenging to achieve.

Meanwhile, it has been shown that various TMDC moiré superlattices can enable flat moiré bands1,18,19,20,21,22,23,24, in which the electron kinetic energy is significantly suppressed, and the Coulomb interaction is strong due to the reduced screening in two-dimensional (2D) materials. The resulting enhanced electron correlation, characterized by the ratio of Coulomb interaction to kinetic energy, opens up exciting opportunities for realizing and exploring quantum-correlated states, such as Mott insulators19,25, Wigner crystals18,20,21, and excitonic insulators26,27,28.

The interlayer excitons in a type-II aligned TMDC moiré heterojunction, with electrons and holes separated in different layers9,29, inherit this correlation and strongly interact with electrons7. This strong interaction is manifested in the significant blueshifts of interlayer exciton photoluminescence (PL) at the correlated electronic states7,30. This inspires us to employ the electron-exciton interaction to control exciton dynamics, such as exciton diffusion31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 in the angle-aligned WS2/WSe2 moiré heterojunction, by directly measuring the interlayer exciton diffusion length and extracting the diffusivity as a function of the electrostatic doping.

We found that when the electron (hole) density reaches one per moiré cell and forms a Mott insulator, the blueshifted interlayer excitons exhibit greatly enhanced diffusivity due to reduced moiré potential confinement, with an enhancement factor as large as two orders of magnitude compared with excitons in the charge-neutral regime. In contrast, when electrons crystallize at fractional fillings and form a generalized Wigner crystal, the interlayer exciton diffusivity is suppressed because the excitons scatter off electrons and effectively interact with the electron crystal as a whole, resulting in increased backscattering and limiting the exciton mobility. Between the fractional fillings, when the electron density is less than one per moiré cell, electrons in the Fermi liquid state dynamically populate all moiré traps. The electron-exciton repulsion effectively reduces the moiré potential confinement of excitons, mobilizing them and leading to enhanced exciton diffusivity as the electron density increases.

The modulated exciton diffusivity exhibits a similar trend for both 60-degree (H-stacked) and 0-degree (R-stacked) aligned WS2/WSe2 devices, while the enhancement from n = 0 to filling factor approaching 1 is more pronounced for the R-stacked device. The difference might stem from the different nature of the two stacked configurations: the interlayer exciton is more extended in the H-stacked WS2/WSe2 as the associated electron and hole are at different moiré sites7,30.

The drastic modulation of the moiré exciton diffusivity demonstrated here by tuning electrostatic doping and correlated electrons ushers in an exciting route of engineering exciton dynamics via quantum many-body interactions44 and can be explored for new quantum states and novel optoelectronic devices.

Results

Exciton diffusion at the correlated insulating states

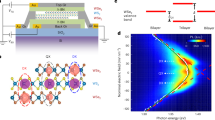

A typical dual-gated WS2/WSe2 moiré heterojunction device is schematically shown in Fig. 1a. In Fig. 1, we excite a dual-gated H-stacked device (H1) with a continuous wave (CW) laser centered at 1.699 eV, which is in resonance with the ground state of moiré intralayer excitons in the angle-aligned WS2/WSe2 heterojunction18.

a Schematic of a dual-gated WS2/WSe2 moiré superlattice device. b Schematic of the exciton diffusion measurement, along with the spatial distribution of the laser spot and PL spot taken from an H-stacked device (H1). Scale bar: 2 µm. c–f Spatially and spectrally resolved PL spectra of the interlayer exciton at different doping levels for device H1, with the x-axis showing the spatial diffusion of the interlayer exciton. The colored dashed lines overlay on the images show the spatial diffusion by tracing 1/e of the maximum intensity. g The radial line-cut of the laser (black) and PL (colored dots) spatial profile for device H1 at different doping levels. The excitation photon energy is centered at 1.699 eV, and the excitation intensity is 57 nW/µm2. All data were taken at a temperature of 3.6 K.

The diffusion of excitons has been studied using various methods31,32,35,40,41,45. In this work, for the first time, we demonstrate the control of moiré exciton diffusion utilizing correlated electrons. Here, we optically excite excitons (schematically shown in Fig. 1b) and measure the broadened spatial PL image, which we then compare with the size of the laser spot33,34,35,36,41. For Fig. 1, we choose an excitation intensity of 57 nW/µm2, which is estimated to generate about 0.2 excitons per moiré cell (see Supplementary Section 3 for details). This excitation intensity ensures that we are well within the linear regime of PL response as a function of excitation intensity. This excitation intensity also improves the linear gating response of the device close to the charge-neutral region (see Supplementary Section 8 for details).

In Fig. 1b, we found a broadened PL image spot of ~ 2.5 µm compared with that of the laser spot of ~ 1.5 µm. In the regime where the PL intensity is a linear function of excitation intensity, the broadened PL profile with a Gaussian width σ (see Supplementary Section 6 for details) compared with the laser beam width (σ0) can be well described by the diffusion of interlayer excitons, with the diffusion length \({l}_{d}\) expressed as46 (details in Supplementary Section 6):

where D is the diffusion constant (diffusivity), and τ is the lifetime of the exciton. We further study the diffusion of interlayer excitons at different doping levels by performing spectral-resolved diffusion measurements of interlayer excitons. Figure 1c–f shows spectrally resolved diffusion images with different filling factors, which normalize the doping with the moiré superlattice density, with n = 1(−1) being one electron (hole) per moiré cell.

It is evident that the diffusion length increases when the doping is increased from n = 0 (Fig. 1f) to n = 1 (Fig. 1c). However, one can also notice that the exciton diffusion length is suppressed at n = 1/3 (Fig. 1d), which corresponds to the previously established generalized Wigner crystal insulator7,18,21, with one electron shared by three moiré unit cells.

We note here that it is important to have spectral information for the diffusion measurements. At n = 1, a new interlayer exciton PL peak (centered around 1.47 eV) with a large blueshift occurs (Fig. 1c), which has been extensively studied and attributed to the exciton-electron repulsion at the Mott insulator state7,30,47. For comparison, we plot the spatial profile of the lower energy exciton peak (centered around 1.435 eV) together with those from other doping levels in Fig. 1g (line cuts from Fig. 1c–f), along with the spatial distribution of the excitation laser.

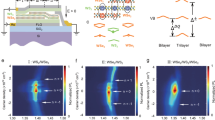

The doping-dependent PL spectra of the interlayer exciton in WS2/WSe2 moiré heterojunction have been extensively studied6,7,30,47,48. Here, we show in Fig. 2a, b the doping-dependent interlayer exciton PL spectra from one H-stacked device (H1) and one R-stacked device (R1), respectively. The correlated insulating states at integer fillings (n = ± 1, ± 2) and fractional fillings (n = ±1/3, n = ±2/3, and more) can be clearly observed, which manifests the high quality of the moiré bilayer devices. Here, we label the n = 0 as the doping when the PL peak position is a local maximum in Fig. 2a, b, but we note that the region near n = 0 can be viewed as charge neutral, and the gating is not linear in the low doping regime. However, the assignment of fractional filling such as n = ± 1/3, ± 2/3 is unambiguous from the PL spectra in Fig. 2a, b, which is also further confirmed by a control device (H2) that is only back-gated so that the microwave impedance microscopy (MIM) measurement can be performed without the screening of the top gate electrode. The comparison between MIM measurements and doping-dependent PL spectra from the control device H2 can be found in Supplementary Section 2. More correlated states from various fractional filling states can be seen from the PL spectra, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3a, b. Here, for the sake of comparison with diffusion measurement, we only focus on the pronounced ones, such as those labeled in Fig. 2a, b.

a, b are PL spectra as a function of the filling factor for H-stacked (H1) and R-stacked (R1) devices, respectively. The dotted black lines in the color plots are the extracted PL peak energies. c, e are the extracted diffusion lengths for different interlayer exciton species (colored dots) as a function of the filling factor for devices H1 and R1, respectively. d, f are the zoom-ins of the shaded gray area in (c) and (e). The black arrows in (a) and (d) point at the doping level where the PL energy has an abrupt redshift. The excitation intensity is 57 nW/µm2 (0.2 excitons per moiré cell) for (a), (c), and (d), and 140 nW/µm2 (0.1 excitons per moiré cell) for (b), (e), and (f).

We then study the spatially resolved PL of the interlayer exciton at different doping levels, and we extract the diffusion length (\({{l}_{d}}^{2}={\sigma }^{2}-{\sigma }_{0}^{2}\)) and plot it as a function of doping in Fig. 2c, e, respectively, with the zoom-ins (Fig. 2d, f) magnifying the fine features between n = −1 and 1. The abrupt blueshifts of the interlayer exciton PL at integer fillings (Fig. 2a, b) are a result of onsite repulsion between the correlated electrons and excitons, as we reported previously7,47. The resulting interlayer excitons are at excited states, and we label them in different colors to manifest their different natures: red for − 1 <n < 1, blue for − 2 <n < −1 and 1 < n < 2, and magenta for n > 2 and n < − 2. Due to the change in the nature of excitons at particular doping levels, such as at n = 1, we note that it is important in this study to keep the spectral information for the spatially resolved PL study that we use to extract the diffusion length, as illustrated in Fig. 1c–f.

The most pronounced feature of the H-stacked device (H1, Fig. 2c, d) is the abrupt decrease of diffusion length at n = ± 1, where the lower energy exciton PL (− 1< n < +1, red dots) transits into the higher energy exciton PL (n < − 1 or n > 1, blue dots), with a blueshift of 36 meV. For the R-stacked device (R1, Fig. 2e, f), the drop in the diffusion length at n = ±1 is more gradual, and the blueshift of PL peak energy (Fig. 2b) is less pronounced, about 13 meV. At n = ±1, the abrupt change of diffusion length for H-stacked devices and the gradual change for R-stacked devices are reproduced in multiple devices (see Supplementary Section 8). The exact mechanism of this difference between R- and H-stacked devices is beyond the scope of the current work, and we will explore it in future studies.

We also find the suppression of the exciton diffusion length for H-stacked devices (red dots in Fig. 2d) closely aligns with the generalized Wigner crystal states at the fractional fillings, showing that the doping dependence of interlayer exciton diffusion length can reveal correlated insulating states, similar to the doping-dependent PL spectra (Fig. 2a). The suppression of diffusion length in the R-stacked device at the Wigner crystal states is less pronounced but noticeable. These observations have been found in more than 22 angle-aligned WS2/WSe2 devices that we have measured, including 14 H-stacked and 8 R-stacked devices. It is worth noting that an additional feature appears in the H-stacked devices, as indicated by the black arrows in Fig. 2a, d, where the PL energy exhibits an abrupt redshift, and the diffusion length reaches a local minimum. This behavior might be due to the formation of attractive polarons, and the increased effective mass leads to a reduction in diffusion length (also see Supplementary Section 8).

The measured suppression of diffusion length in the control device, back-gated H2, also correlates well with the fractional filling states identified via MIM measurements, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2c (see Supplementary Section 2), further confirming that the suppressed diffusion length corresponds to generalized Wigner crystal states.

Lifetime and diffusivity of interlayer excitons

To investigate these features, we perform time-resolved PL (TRPL) measurements for H1 (Fig. 3a) and R1 (Fig. 3b), respectively. The excitation intensity of the TRPL is chosen to be as low as 200 nW/µm2, so that the PL response is in the linear regime, and the doping-dependent PL spectra are similar to what we show in Fig. 2 (see Supplementary Section 4). We also note that we resolve the spectral information of TRPL signals using a spectrograph to disperse light before the Avalanche Photodiode (APD) single-photon detector so that we can ensure monitoring the exciton of the right species, distinguishing the lower energy and blueshifted higher energy exciton across n = ±1. The lifetimes of the exciton (\(\tau\)) for both devices drop abruptly at n = ±1 (Fig. 3a, b) due to the excited state nature of the interlayer exciton in the presence of strong onsite electron-exciton repulsion7,48. Based on Eq. (1), the abrupt decrease in lifetime at n = ±1 contributes to the sudden drop of exciton diffusion length at the Mott insulator states.

It is worth noting that the lifetime has a sudden drop across n = ± 1 for the H-stacked device compared with the R-stacked device. This is because the interlayer excitons in the R-stacked device are more localized at n = 07,30. As a result, the increased doping will increase the overlap of the exciton with carriers and increase the nonradiative channels more drastically, leading to the rapid decrease of lifetime as a function of doping and a more gradual lifetime change across n = ± 1. In contrast, the interlayer exciton in H-stacked devices is more delocalized7,30 to start with, and the doping induced change is not as drastic. The different patterns of lifetime change also lead to the different behaviors of diffusion length across n = ± 1 for H- and R-stacked devices, as shown in Fig. 2c,e: a more abrupt change for the H-stacked device and a more gradual change for the R-stacked device.

However, the diffusion length dips observed at fractional fillings for both R and H stack samples cannot be attributed to the lifetime change, as the lifetimes at the fractional fillings (shown in Fig. 3a, b) actually increase, likely due to the suppression of nonradiative channels once the correlated insulators form ref. 49. From Eq. (1), such a decrease in diffusion length can only be explained by the reduced diffusivity at the fractional fillings.

Modulating exciton diffusivity via doping

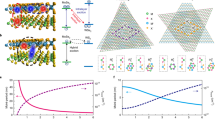

We now combine the diffusion length obtained in Fig. 2 and extrapolate the lifetime data from Fig. 3a, b, which can be used to extract the exciton diffusivity following Eq. (1) as \(D=({\sigma }^{2}-{\sigma }_{0}^{2})/2\tau\). We plot diffusivity as a function of the doping for devices H1 (Fig. 3c) and R1 (Fig. 3d), respectively.

The diffusivity of the electron and hole doping regions is similar, except for some asymmetry likely arising from the deeper moiré trapping potential for holes50. Therefore, we focus on the electron doping region in the following discussion. The behavior of diffusivity from the hole-doping region can be understood similarly.

The most striking feature is the enhancement of exciton diffusivity when the filling factor increases beyond the Mott insulator states (n > 1). The diffusivity exhibits around two orders of magnitude increase from n = 0 to n > 1 (33 times for device H1 and 177 times for R1). Such a drastic increase can be observed in all the samples we have measured (see Supplementary Fig. S11) and is consistent with the excited state nature of the exciton for n > 1, where the significantly blueshifted exciton PL energy suggested that the interlayer excitons experience a strong onsite repulsion from the correlated electrons forming a fermionic Mott insulator. The blueshifted exciton energy, 13 meV for R1 and 36 meV for H1, suggests that the excitons are at much-elevated energy and are less confined by the moiré potential, hence the much-enhanced diffusivity. The diffusivity is even more enhanced for the exciton with the resonance energy further blueshifted at n > 2, confirming this interpretation.

The diffusivity in both devices is evidently suppressed at n = 0, which is more obvious in Fig. 4a, b. This suppression is due to the moiré potential confinement impeding exciton diffusion, consistent with previous reports38,40,41,51. At the fractional filling, when the generalized Wigner crystals form, the diffusivity is also significantly suppressed (Fig. 4a, b), more significantly suppressed than the diffusion length due to the increased lifetime at the insulating states at the fractional fillings. This is because, at the fractional fillings such as n = 1/3, electrons form periodic crystals with electrons localized in one-third of the moiré cells. As a result, excitons scattering off electrons have to interact with the electron crystal as a whole, which possesses large mass inertia. The resulting back-scattering will suppress the diffusivity.

However, the electron Fermi liquid in between the fractional fillings would affect the exciton diffusivity differently from the generalized Wigner crystal states. For example, at the Fermi liquid state near the filling factor n = 1/3, the delocalized electrons will lead to the effective occupation of close to 1/3 electron per moiré cell. This is in stark contrast with the generalized Wigner crystal state at n = 1/3, in which one out of three moiré cells is occupied by one localized electron that strongly repels the interlayer exciton, while the two other moiré cells are vacant and do not contribute to the repulsion. Therefore, by introducing free electrons into the system, the repulsion between delocalized electrons and interlayer excitons effectively lowers the moiré potential confinement of interlayer excitons, enhancing diffusivity. As schematically shown, the effective potential well depth is lowered for excitons at n = 0.2 (Fig. 4c) than that at n = 0 (Fig. 3e) (also n = 1/3, Fig. 4d), and the diffusivity is increased. Further, this enhancement will increase as the electron density increases, which raises the average number of electrons per moiré cell and enhances repulsion. Our Monte Carlo simulations capture the feature discussed above: the suppression of the exciton diffusivity at the correlated insulator states and increased diffusivity at the Fermi liquid state as the doping increases, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S10 of the Supplementary Information. Detailed modeling and calculations can be found in Supplementary Section 7.

We note that the enhancement factor near the Mott insulator state, when the filling factor approaches n = 1 compared with that at n = 0, is drastically different for devices H1 and R1: the diffusivity increases by about 2 times for device H1 and around 45 times for R1 (Fig. 4a, b). This difference has been reproduced in another H-stacked device (H3) and R-stacked device (R2) (see Supplementary Fig. S11). This striking difference is likely attributed to the more extended nature of interlayer excitons in the H-stacked devices. The Coulomb repulsion between electrons and excitons that lowers the effective moiré potential depth is a sensitive function of screening, which increases with doping. The extended interlayer excitons could even form attractive exciton-polarons with electrostatically doped electrons that increase the effective mass of excitons and reduce diffusivity52. However, the interlayer excitons in the R-stacked moiré structure are more localized and less affected by the screening, which can be seen from the less sensitivity of PL energy resonances to the doping (Fig. 2a, b) and has been reported earlier7,30. As a result, the Coulomb repulsion remains strong for the R-stacked device even at the increased electron doping, leading to much enhanced exciton diffusivity.

Discussion

Our study reveals an intriguing moiré system in which the exciton dynamics can be sensitively tuned through electrostatic doping, due to the unique exciton-electron interaction stemming from strong electron correlation. The electrostatic doping-enhanced diffusivity is also sensitive to the stacking order of the WS2/WSe2 moiré superlattice, which hosts different interlayer excitons with the layer-separated electron and hole either occupying the same (R-stacked device) or different (H-stacked device) moiré sites. Our work provides critical insight into further engineering of exciton dynamics. The active control of interlayer exciton diffusion via electric means is also promising for further realization and implementation of moiré excitonic devices.

Note: During the preparation of this manuscript, we became aware of another relevant work on moiré exciton diffusion52.

Methods

Device fabrication

We used a dry pick-up method that was reported in our previous work53,54 to fabricate angle-aligned WS2/WSe2 heterostructures. Gold electrodes are pre-patterned on the Si/SiO2 substrate. The monolayer TMDC, h-BN, and a few-layer graphite flakes were directly exfoliated on silicon chips with 285 nm thermally grown oxide and then picked up by a polycarbonate (PC)/ polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamp sequentially. The alignment of each TMDC layer was performed using a home-built microscope-based transfer stage equipped with a rotation controller (angular precision of 0.02 degrees). After stacking, the PC film was removed in the chloroform/isopropanol sequence. The fabricated devices were then dried with nitrogen gas and annealed in a vacuum (< 10−6 torr) at 250 °C for 8 h.

Optical characterization

For all the optical measurements shown in the main text, the samples were measured in a cryogen-free optical cryostat (AttoDRY 1000) at 3.6 K. A home-built confocal imaging system was used to focus the laser onto the sample (with a beam spot diameter of ~ 1.5 µm) with an achromatic low-temperature objective. The PL and spectrally resolved diffusion measurements were performed with a CW laser with the photon energy centered at 1.699 eV. For the spectrally resolved diffusion measurements, an achromatic lens with a focal length of 500 mm was used to obtain a 200✕ magnification. The optical signals were dispersed using a diffraction grating (600 grooves per mm) and detected with a silicon charge-coupled device (CCD) camera, with the x-axis array resolves the spectral information and y-axis array resolves the spatial information. Spectrally resolved time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) measurements were carried out using a supercontinuum laser (YSL Photonics) operating at a 1 MHz repetition rate. A bandpass filter with a 10 nm bandwidth was used to select excitation light centered at 650 nm. The excitation intensity is 200 nW/µm2 for H1 and 300 nW/µm2 for R1, respectively. The signal was dispersed using the same diffraction grating (600 grooves per mm) and then collected by a single-photon detector (PicoQuant) and a picosecond event timer (PicoHarp 300). The PL, spectrally resolved diffusion, and spectrally resolved TRPL measurements have also been performed in a different home-built setup based on a Montana cryostat at 6 K. The data are shown in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Data availability

The source data for Figs. 1–4 are provided with this paper. All other data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Zhang, Z. et al. Flat bands in twisted bilayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Phys. 16, 1093–1096 (2020).

Wu, F., Lovorn, T., Tutuc, E. & MacDonald, A. H. Hubbard model physics in transition metal dichalcogenide moiré bands. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 26402 (2018).

Wu, F., Lovorn, T., Tutuc, E., Martin, I. & MacDonald, A. H. Topological insulators in twisted transition metal dichalcogenide homobilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 86402 (2019).

Devakul, T., Crépel, V., Zhang, Y. & Fu, L. Magic in twisted transition metal dichalcogenide bilayers. Nat. Commun. 12, 6730 (2021).

Yu, H., Chen, M. & Yao, W. Giant magnetic field from moiré induced Berry phase in homobilayer semiconductors. Natl. Sci. Rev. 7, 12–20 (2020).

Xiong, R. et al. Correlated insulator of excitons in WSe2/WS2 moiré superlattices. Science 380, 860–864 (2023).

Lian, Z. et al. Valley-polarized excitonic Mott insulator in WS2/WSe2 moiré superlattice. Nat. Phys. 20, 34–39 (2024).

Rivera, P. et al. Interlayer valley excitons in heterobilayers of transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 1004–1015 (2018).

Seyler, K. L. et al. Signatures of moiré-trapped valley excitons in MoSe2/WSe2 heterobilayers. Nature 567, 66–70 (2019).

Tran, K. et al. Evidence for moiré excitons in van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 567, 71–75 (2019).

Jin, C. et al. Observation of moiré excitons in WSe2/WS2 heterostructure superlattices. Nature 567, 76–80 (2019).

Alexeev, E. M. et al. Resonantly hybridized excitons in moiré superlattices in van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 567, 81–86 (2019).

Brotons-Gisbert, M. et al. Spin–layer locking of interlayer excitons trapped in moiré potentials. Nat. Mater. 19, 630–636 (2020).

Li, W., Lu, X., Dubey, S., Devenica, L. & Srivastava, A. Dipolar interactions between localized interlayer excitons in van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Mater. 19, 624–629 (2020).

Yu, H., Liu, G.-B., Tang, J., Xu, X. & Yao, W. Moiré excitons: From programmable quantum emitter arrays to spin-orbit–coupled artificial lattices. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701696 (2017).

Tang, H. et al. On-chip multi-degree-of-freedom control of two-dimensional materials. Nature 632, 1038–1044 (2024).

Kapfer, M. et al. Programming twist angle and strain profiles in 2D materials. Science 381, 677–681 (2023).

Regan, E. C. et al. Mott and generalized Wigner crystal states in WSe2/WS2 moiré superlattices. Nature 579, 359–363 (2020).

Tang, Y. et al. Simulation of Hubbard model physics in WSe2/WS2 moiré superlattices. Nature 579, 353–358 (2020).

Huang, X. et al. Correlated insulating states at fractional fillings of the WS2/WSe2 moiré lattice. Nat. Phys. 17, 715–719 (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. Correlated insulating states at fractional fillings of moiré superlattices. Nature 587, 214–218 (2020).

Shimazaki, Y. et al. Strongly correlated electrons and hybrid excitons in a moiré heterostructure. Nature 580, 472–477 (2020).

Li, T. et al. Charge-order-enhanced capacitance in semiconductor moiré superlattices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1068–1072 (2021).

Jin, C. et al. Stripe phases in WSe2/WS2 moiré superlattices. Nat. Mater. 20, 940–944 (2021).

Li, T. et al. Continuous Mott transition in semiconductor moiré superlattices. Nature 597, 350–354 (2021).

Chen, D. et al. Excitonic insulator in a heterojunction moiré superlattice. Nat. Phys. 18, 1171–1176 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Correlated interlayer exciton insulator in heterostructures of monolayer WSe2 and moiré WS2/WSe2. Nat. Phys. 18, 1214–1220 (2022).

Gu, J. et al. Dipolar excitonic insulator in a moiré lattice. Nat. Phys. 18, 395–400 (2022).

Jin, C. et al. Ultrafast dynamics in van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 994–1003 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Intercell moiré exciton complexes in electron lattices. Nat. Mater. 22, 599–604 (2023).

Rossi, A. et al. Anomalous Interlayer Exciton Diffusion in WS2/WSe2 Moiré Heterostructure. ACS Nano 18, 18202–18210 (2024).

Sun, Z. et al. Excitonic transport driven by repulsive dipolar interaction in a van der Waals heterostructure. Nat. Photonics 16, 79–85 (2022).

Tagarelli, F. et al. Electrical control of hybrid exciton transport in a van der Waals heterostructure. Nat. Photonics 17, 615–621 (2023).

Jauregui, L. A. et al. Electrical control of interlayer exciton dynamics in atomically thin heterostructures. Science 366, 870–875 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Diffusivity reveals three distinct phases of interlayer excitons in MoSe2/WSe2 heterobilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 106804 (2021).

Bai, Y. et al. Evidence for exciton crystals in a 2D semiconductor heterotrilayer. Nano Lett. 23, 11621–11629 (2023).

Wietek, E. et al. Nonlinear and negative effective diffusivity of interlayer excitons in moiré-free heterobilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 16202 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Interlayer exciton transport in MoSe2/WSe2 heterostructures. ACS Nano 15, 1539–1547 (2021).

Wagner, K. et al. Diffusion of excitons in a two-dimensional fermi sea of free charges. Nano Lett. 23, 4708–4715 (2023).

Yuan, L. et al. Twist-angle-dependent interlayer exciton diffusion in WS2–WSe2 heterobilayers. Nat. Mater. 19, 617–623 (2020).

Choi, J. et al. Moiré potential impedes interlayer exciton diffusion in van der Waals heterostructures. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba8866 (2025).

Li, Z. et al. Enhanced exciton drift transport through suppressed diffusion in one-dimensional guides. ACS Nano 17, 22410–22417 (2023).

Cadiz, F. et al. Exciton diffusion in WSe2 monolayers embedded in a van der Waals heterostructure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 152106 (2018).

Brem, S. & Malic, E. Bosonic delocalization of dipolar moiré excitons. Nano Lett. 23, 4627–4633 (2023).

Kulig, M. et al. Exciton diffusion and halo effects in monolayer semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 207401 (2018).

Crank, J. The Mathematics of Diffusion. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1975).

Miao, S. et al. Strong interaction between interlayer excitons and correlated electrons in WSe2/WS2 moiré superlattice. Nat. Commun. 12, 3608 (2021).

Park, H. et al. Dipole ladders with large Hubbard interaction in a moiré exciton lattice. Nat. Phys. 19, 1286–1292 (2023).

Tan, Q. et al. Layer-dependent correlated phases in WSe2/MoS2 moiré superlattice. Nat. Mater. 22, 605–611 (2023).

Shabani, S. et al. Deep moiré potentials in twisted transition metal dichalcogenide bilayers. Nat. Phys. 17, 720–725 (2021).

Knorr, W. et al. Exciton transport in a moiré potential: From hopping to dispersive regime. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 124002 (2022).

Upadhyay, P. et al. Giant enhancement of exciton diffusion near an electronic Mott insulator. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.18357 (2024).

Lian, Z. et al. Quadrupolar excitons and hybridized interlayer Mott insulator in a trilayer moiré superlattice. Nat. Commun. 14, 4604 (2023).

Meng, Y. et al. Strong-interaction-driven quadrupolar-to-dipolar exciton transitions in a trilayer moiré superlattice. Nat Photon https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-025-01741-x (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Chenhao Jin and Michael Knap for helpful discussions. S.-F.S. acknowledges support from NSF (DMR−1945420, DMR-2104902, DMR-2428545, ECCS-2344658, and ECCS-2139692) and a community collaboration award from the Pittsburgh Quantum Institute. This work was also supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, grant https://doi.org/10.37807/GBMF13836. J.C., Q.W., and Y.-T.C. acknowledge support from NSF under awards DMR-2104805 and DMR-2145735. K.W. and T.T. acknowledge support from the JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers 21H05233 and 23H02052) and World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI), MEXT, Japan. S.A.T. acknowledges primary support from DOE-SC0020653 (excitonic studies on TMDs crystals), partial support from NSF CBET 2330110, NSF CMMI 2129412, Applied Materials Inc. and Lawrence Semiconductor Labs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-F.S. conceived the project. Y.M. fabricated heterostructure devices. L.Y. and L.M. performed the optical spectroscopy measurements. Q.W., J.C., and Y.-T.C. performed the MIM measurements. M.B. and S.T. grew the TMDC crystals. T.T. and K.W. grew the BN crystals. Q.C. and B.H. helped with device fabrication. C.X. and W.Y. contributed to theoretical understanding and simulations. S.-F.S., W.Y., L.Y., L.M., Y.M., and C.X. analyzed the data. S.-F.S. wrote the manuscript with the help of L.Y., L.M., Y.M., and B.C., along with input from all authors. These authors contributed equally: Li Yan, Lei Ma, Yuze Meng, and Chengxin Xiao.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Danqing Wang, Zuocheng Zhang and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, L., Ma, L., Meng, Y. et al. Anomalously enhanced diffusivity of moiré excitons via manipulating the interplay with correlated electrons. Nat Commun 16, 10569 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65602-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65602-5