Abstract

Tungsten diselenide (WSe2) is a promising p-type semiconductor limited by high contact resistance (RC) and the lack of a reliable doping strategy. Here, we demonstrate that exposing WSe2 to chloroform provides simple and stable p-type doping. In monolayer WSe2 transistors with Pd contacts, chloroform increases the maximum hole current by over 100× (>200 µA/µm), reduces RC to ~ 2.5 kΩ·μm, and retains an on/off ratio of 1010 at room temperature. These improvements persist for over 8 months, survive a 150 °C thermal anneal, and remain effective down to 10 K, enabling a cryogenic RC of ~ 1 kΩ·μm. Density functional theory indicates that chloroform strongly physisorbs to WSe2, inducing hole doping with minimal impact on the electronic states between the valence band and conduction band edges. Auger electron spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy suggest that chloroform intercalates at the WSe2 interface with the gate oxide, contributing to doping stability and mitigating interfacial dielectric disorder, though further studies are needed to conclusively confirm this mechanism. This robust, scalable approach enables high-yield WSe2 transistors with good p-type performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) semiconductors, particularly transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), are promising candidates for next-generation, high-density, complementary-metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS)1,2 and low-temperature electronics. However, the large contact resistance (RC) often observed in nanoscale TMD devices poses a significant obstacle to device performance, limiting the on-state drain current, ID, needed for practical circuit applications. Both n-type and p-type transistors are critical for low-power CMOS3, but progress on minimizing RC has largely been limited to n-type devices4,5. Developing scalable, low-RC p-type contacts for 2D transistors remains a critical challenge. Additionally, RC typically increases further at low temperatures, impeding other fundamental charge transport studies6.

Various strategies have been explored to reduce RC to p-type WSe2 transistors, including transferred metal7 or semimetal8,9 contacts. However, metal contacts typically form large Schottky barriers at the metal-2D semiconductor interface (preventing low RC), and semimetal contacts have yet to experimentally demonstrate superior performance for p-type devices. An alternative is to lower RC by implementing stable p-type doping near the contacts. Substitutional doping with electron acceptors (e.g., V10, Nb11,12) is stable due to covalent chemical bonding but is likely to require complex fabrication with multiple material growth steps. In comparison, p-type surface charge transfer doping (SCTD)13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24 withdraws electrons from the 2D channel using higher electronegativity capping or adsorbate layers with work function values below the Fermi-level of the WSe2, such as transition metal oxides (MoOx13 and WOx14,17,18), NOx19,20,25,26, and halide compounds (HAuCl421, AuCl322, RuCl323,24, PtCl416). SCTD typically preserves the host lattice and has the potential to introduce fewer scattering centers27. However, the temporal and thermal stability of these methods remains unclear due to the high chemical reactivity or low thermal stability of the reagents involved28. Furthermore, there is little consensus on the mechanism of halide-based doping, with some studies suggesting reactions in which Cl atoms substitute and passivate chalcogen vacancies29,30,31, while others propose molecular physisorption22,32 or intercalation33.

Solvent exposure can also unintentionally dope TMDs. For example, MoS2 and WSe2 are n-doped by exposure to the low-electronegativity solvent acetone during removal of electron-beam (e-beam) lithography resists like poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA)34,35. Conversely, the high-electronegativity solvent chloroform (CHCl3) was shown to p-dope semimetallic graphene33. This suggests that chloroform could serve as an effective p-type dopant for 2D semiconductors such as WSe2, offering a simple and scalable approach compared to existing doping techniques. However, solvent-based doping is often regarded as transient, and the impact of chloroform doping on the electrical performance of p-channel WSe2 transistors has not yet been studied.

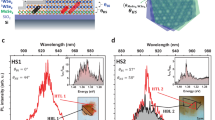

In this work, we demonstrate that chloroform can induce high-performance, stable, and high-yield p-doping in monolayer WSe2 transistors (Fig. 1a, b). Exposing monolayer WSe2 transistors to chloroform increases ID by two orders of magnitude, with hole currents reaching up to 203 μA/μm at VDS = −1 V (Fig. 1c). These devices also maintain large Ion/Ioff ratios (~ 1010) and a low RC of 2.5 kΩ·μm (at room temperature) and 1.0 kΩ·μm (at 10 K). Compared to recent approaches such as contact engineering (e.g., Sb/Pt8,36, Ru37,38), oxide-based doping (WOx17,39, MoOx8,40, NOx19,39), and other halide-based dopants (HAuCl421, RuCl323), chloroform doping achieves one of the highest reported values for p-type transistor current (Fig. 1b). Additionally, we observe that chloroform-doped transistors remain stable over 8 months (retaining 81% of initial doped ID,max) and survive annealing at 150 °C. Density functional theory (DFT) reveals that chloroform binds strongly ( > 260 meV, i.e., >10kBT at 296 K) to WSe2 without introducing mid-gap states. Atomic-force microscopy (AFM), Auger electron spectroscopy (AES), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) suggest that chloroform intercalates at the WSe2 interface with the gate oxide, further stabilizing its doping. This straightforward approach enhances p-type performance in WSe2 transistors and complements other contact and interface engineering techniques for advancing 2D semiconductor technologies.

a Schematic of chloroform-doped WSe2, illustrating the doping process and possible adsorption pathways. After fabrication, devices are left in chloroform overnight. b Benchmarking maximum p-type current (|ID,max|) vs. monolayer WSe2 channel length (Lch) at drain voltage (VDS) = -1 V at room temperature, using various contact metals and doping strategies. Circles8,37,38,39,75,76,77,78,79,80,81 mark results with no intentional doping, squares8,17,19,25,36,39,40 denote oxide-based doping (MoOx, WOx, NOx), and triangles21,23 label halide-based doping. Our results with chloroform doping (stars) achieve among the highest hole currents to date for monolayer WSe2. c Measured drain current (ID) vs. gate voltage (VGS) for monolayer WSe2 device before (black line) and after (green line) chloroform doping, reaching hole current of 203 μA/μm. Forward and backward sweeps are shown, revealing some counterclockwise hysteresis. d Raman spectra before and after chloroform doping of monolayer WSe2. e Photoluminescence (PL) spectra of monolayer WSe2 before and after chloroform doping.

Results and discussion

Characterization of chloroform-doped WSe2

Optical spectroscopy provides insights into the physical and chemical interactions between the WSe2 and chloroform. Raman spectra of monolayer WSe2 soaked overnight in chloroform show no significant changes in the E’/A1’ peak intensity ratio (Fig. 1d), which suggests that long-term chloroform exposure does not significantly increase the WSe2 defectivity. We also do not observe an increase in LA(M) or 2LA(M) peak intensity associated with the disruption of the WSe2 lattice (Supplementary Fig. 1). The photoluminescence (PL) spectrum after chloroform doping (Fig. 1e) shows lower intensity than for the undoped sample. This PL quenching is consistent with a chloroform-induced increase in the hole concentration, leading to more non-radiative recombination via positive trions34. Additionally, the negligible change in surface roughness and morphology after doping indicates that residue adsorption does not play a significant role (Supplementary Fig. 2).

To investigate the electrical performance of chloroform-doped WSe2, continuous monolayer CVD-grown WSe2 was transferred onto an array of prefabricated ~5 nm HfO2 local back gates (Fig. 2a). The local back gates were defined by photolithography and lift-off of 2/8 nm Ti/Pt, followed by thermal atomic-layer deposition of HfO2 gate dielectric with equivalent oxide thickness of 1.23 nm. The WSe2 channel was patterned by XeF2 etching. Fine contact regions were also defined using e-beam lithography with a bilayer PMMA resist stack. Pd/Au (20/20 nm) were deposited by evaporation at ~10-7 Torr, followed by lift-off in acetone overnight, then rinsed in isopropanol (IPA). Electrical measurements were conducted in a vacuum at ~10-4 Torr. After initial device measurements, the devices were soaked in chloroform for >8 h and re-measured in vacuum (see Methods for more details).

a Cross-sectional schematic of the WSe2 transistor (top) and optical microscope image of the fabricated device (bottom). b Measured ID vs. VGS before and after doping at several channel lengths (Lch) from 0.1 to 1 μm. c Lch-dependent statistical analysis before and after doping of (top) maximum drain-current ID,max at VGS = −3.4 V, and (bottom) on-state current Ion at an overdrive voltage Vov = 1.3 V. d Threshold voltage (VT,cc) at a constant current of 10 nA/μm before and after doping. All devices display a positive shift in VT, indicating p-doping. In panels (c, d), a box plot was created for every group of data. The central mark of the box indicates the median, and the bottom and top edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. e Contact resistance (RC) of chloroform-doped WSe2 devices with Pd contacts, extracted using the transfer length method (TLM). f Subthreshold swing (SS) vs. ID in Lch = 1 μm devices before and after doping. Doped devices show lower SS across the whole subthreshold ID range. g Measured ID vs. VGS at 10 K after doping for various channel lengths (Lch = 0.1 to 0.7 μm). h ID vs. VDS curve for a representative Lch = 0.7 μm device at 10 K from VGS = −3.0 V to −2.2 V in steps of 0.1 V increments. The inset shows a magnified view of the low-voltage region. i RC of chloroform-doped WSe2 devices with Pd contacts at 10 K, extracted using the TLM method. Notably, a low contact resistance and high drain current are still maintained at cryogenic temperatures. In panels (e, i), error bars indicate the standard error of the linear fit used for TLM extraction (fitting total resistance vs. Lch at fixed Vov), representing the uncertainty in the extracted RC.

Figure 2b presents the transfer characteristics of 101 transistors before and after p-doping at VDS = −1 V, with channel lengths (Lch) ranging from 100 nm to 1 μm. Prior to doping, the devices exhibit a highly negative VT around −2.6 V. After doping, the VT shifts positively and the maximum ID uniformly increases by ~100× across all devices, from ~ 1 μA/μm to >100 μA/μm (Fig. 2c). The low device-to-device variation after doping demonstrates the reproducibility of this doping method. Noticeably, the electron branch is strongly suppressed after doping (Fig. 2b). This suppression likely arises from the positive VT shift from increased hole concentration (thus requiring higher VGS for electron injection) and from the increase in electron Schottky barrier height, which together hinder electron current.

We can further understand the origin of these improvements by examining the effects of chloroform upon the statistical distributions of the maximum hole current ID,max (at VGS = −3.4 V) and the on-state hole current Ion at a fixed overdrive voltage (Vov = |VGS − VT | ), both shown in Fig. 2c. Interestingly, devices of all channel lengths show concurrent increases in max ID, and in Ion at fixed Vov = 1.3 V. Evidently, the chloroform doping shifts VT positively, but the observed increase in Ion at fixed Vov in both long- and short-channel devices suggests the improvement is a combined effect of increased mobility and reduced RC. The maximum transconductance (gm) of each device shows a 30.5× median increase (from 1.07 to 33 μS/μm) for Lch = 1 μm devices (Supplementary Fig. 3a), consistent with this interpretation.

All devices demonstrate a positive VT shift (VT extracted at a constant current 10 nA/μm)41, with a median shift value of 1.0 V (from −2.6 V to −1.6 V), consistent with p-doping (Fig. 2d). This VT shift corresponds to roughly 0.9–1.8 × 1013/cm2 carriers induced from this doping technique (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Precise quantification of the initial doping concentration in the WSe2 is difficult as fabrication-induced effects (e.g., adsorbates, annealing, processing history, etc.) can alter the concentration. We estimate an initial electron concentration on the order of 1012 cm-2 prior to doping (see Supplementary Note 1). Thus, upon chloroform doping, the induced hole density of ~1013 cm-2 can compensate this initial doping and dominate the final carrier concentration, shifting the device to p-type operation.

Additionally, unlike other SCTD methods13,19,21, the chloroform-doped transistors did not exhibit any degradation in off-state current even at the shortest Lch of 100 nm. We extract the RC of our Pd-contacted doped monolayer WSe2 devices using the transfer length method (TLM), yielding an RC of 2.5 (2.8) kΩ·μm for our best (median) pseudo-TLM structure (as described in Methods) (Fig. 2e). In comparison, the initial RC before chloroform exposure was 168 kΩ·μm (Supplementary Fig. 3c). The improved RC likely stems from the doping of the WSe2 region near the contacts, which narrows the metal-semiconductor energy barrier width and enhances the contribution of tunneling42,43. We estimate a low Schottky barrier height (SBH) of ~ 100 meV after doping, consistent with previous theoretical calculations44. However, direct extraction of SBH from temperature-dependent data remains challenging due to the small screening length and large contribution of tunneling current across the narrow barrier. Rigorous simulations to extract SBH are an important future topic to understand the RC improvement in these and other doped WSe2 devices. Notably, this RC value represents the best reported for Pd contacts on monolayer WSe2 and is comparable to the highest-performing contact schemes reported to date (e.g., Sb/Pt with MoOx doping36, WOx and NO doping39). Supplementary Table 1 benchmarks the performance of p-type monolayer WSe2, highlighting that our devices achieve state-of-the-art RC and performance metrics.

Comparison of the subthreshold swing (SS) before and after doping reveals a decrease in SS for the doped devices, down to 81.4 mV/dec from 144 mV/dec at room temperature (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 3d). This improvement in SS spans the entire subthreshold range of ID from doping. (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 3e), which may be due to passivation of interfacial defects and could also explain the increase in mobility45.

High RC also limits the operation of WSe2 transistors at cryogenic temperatures, impeding the study of WSe2 in quantum transport devices. Chloroform-doped monolayer WSe2 transistors at 10 K (Fig. 2g) show consistently high hole current across all devices, up to 403 μA/μm at VDS = −1 V for Lch = 0.1 μm (Supplementary Fig. 4), with relatively linear ID vs. VDS (Fig. 2h). The cryogenic RC ~ 1.0 kΩ·μm was extracted from a pseudo-TLM fit to devices ranging from Lch = 100 nm to 1 μm (Fig. 2i). To our knowledge, this is the lowest p-type RC reported to date for cryogenic temperatures.

Charge transfer mechanism of chloroform-doped WSe2

Temperature-dependent PL measurements of WSe2 before (Fig. 3a) and after (Fig. 3b) chloroform exposure provide additional evidence for charge transfer. In both samples, the peaks at 1.75 eV and 1.71 eV correspond to neutral excitons (X) and trions (T), respectively, with the 40 meV difference matching the reported trion binding energy46,47. Additionally, the relative intensity of the trion peak is greater than the exciton peak in the chloroform-exposed WSe2 (Supplementary Fig. 5), as expected for increased doping48.

a Photoluminescence (PL) spectra of an undoped monolayer WSe2 sample at different temperatures (6.7 to 296 K). b PL spectra of chloroform-doped monolayer WSe2 sample from 6.7 to 296 K. Representative Gaussian-Lorentzian blend curve fits are shown for the 6.7 K spectra in panels (a, b), corresponding to the neutral exciton (X), trion (T), and L1-L3 peaks (described further in the text). c Density functional theory (DFT) simulated isosurfaces of monolayer WSe2 with adsorbed chloroform in Cl-facing (top) and H-facing (bottom) configurations, as well as the calculated adsorption energies (Eads). The value of the Bader charge transfer efficiency is shown for each chloroform orientation, corresponding to the charge transfer of one chloroform molecule. d Potential energy vs. distance for an adsorbed chloroform to monolayer WSe2 in Cl-facing and H-facing orientations. The adsorption energy ranges from 300–500 meV and the equilibrium distance from 2–4 Å, consistent with strong physisorption. Inset: zoomed-out view of the potential energy vs. distance. e Projected density of states (pDOS) contributions from monolayer WSe2 and chloroform to the overall DOS in the Cl-facing orientation. The valence band maximum EV and conduction band minimum EC are marked with dashed pink lines. Noticeably, no chloroform states are formed in the WSe2 band gap. The inset shows a zoomed-in view of the PDOS contributions around the WSe2 band gap.

In both doped and undoped WSe2, the three lower-energy peaks—labeled L1 (~ 1.67 eV), L2 (~ 1.64 eV), and L3 (~ 1.60 eV)—resemble previous reports of excitonic bound states48 which display sublinear excitation power dependence (Supplementary Fig. 5) and rapidly quench above 100 K49. These characteristics are consistent with weakly-bound defect or donor states near the valence band maxima49,50. The intensity of the L1, L2, and L3 peaks is significantly higher in the doped sample (Fig. 3a, b), which indicates increased radiative recombination of electrons and holes bound to different sites and could be explained by the Fermi-level moving towards the valence band after chloroform doping51,52. The decrease in exciton intensity and emergence of bound states suggest that the passivation of WSe2 defects is unlikely. Techniques53,54,55 that passivate defects commonly exhibit an increase in quantum yield and the suppression of low-energy defect peaks at low temperatures.

To investigate the p-doping mechanism, we modeled the interactions between chloroform and WSe2 using density functional theory (DFT). The chloroform absorption site was determined by relaxation against a rigid 5 × 5 WSe2 supercell, considering geometries where the hydrogen atom faced towards (H-facing) or away from (Cl-facing) the monolayer WSe2. Additional computational details are provided in the Methods section.

The Cl-facing and H-facing chloroform orientations exhibit favorable adsorption energies (Eads) of −468 and −351 meV, respectively, indicating strong physisorption ( | Eads | ≫ kBT) to the WSe2 without inducing covalent chemical modification (Fig. 3c, d). This greatly exceeds adsorption energies between some small molecules and graphene ( | Eads | <100 meV)56 and are on the high end of values calculated for other adsorbates on TMDs (50 to 333 meV)57,58. In comparison, chemisorption is characterized by stronger binding energies (≥1 eV) and shorter distances (<2 Å)59. Thus, the adsorption energies and equilibrium distance from 2.5–3.2 Å (Fig. 3d) resemble strong physisorption.

Bader charge analysis reveals that the chloroform withdraws electrons from the WSe2 in both configurations (Fig. 3c). In both the Cl-facing and H-facing orientations, the adsorbed chloroform molecule gains a net charge of 0.0095 and 0.0351 excess electrons, respectively, confirming p-doping. These electron transfers are comparable to that between several well-known TMD SCTD systems, including: (i) MoO3, a well-established p-dopant, and MoS2 (~0.077 electrons60 transferred from MoS2 to MoO3 per unit cell of MoS2, assuming full surface coverage), (ii) MoS2 and acetone (~ 0.039 electrons transferred to MoS2 per molecule of acetone61), which is known to strongly n-dope 2D TMDs34,35, and (iii) nitric oxide (NO) and WS2 (0.018 electrons per molecule of NO57), which is known to be an excellent p-dopant for 2D TMDs19,39. For a threshold voltage shift of 1 V, the calculated Bader charge transfer of 0.0095 (0.0351) holes per chloroform molecule corresponds to a surface coverage of 1.0 (0.27) chloroform molecules per WSe2 unit cell. The calculated Bader charge transfer could be increased by up to a factor of four due to substrate interactions61, which would further enhance the predicted efficiency of hole doping due to chloroform adsorption.

According to the atom-resolved projected density of states (pDOS), the chloroform orbitals are located more than 1 eV below the valence band edge or above the conduction band edge of monolayer WSe2, and the chloroform molecule does not introduce electronic states near the band extrema or in the band gap (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 6). This suggests that the charge transfer between chloroform and WSe2 occurs without covalent bond formation or orbital hybridization, which is consistent with the adsorption energies we calculate for the chloroform/WSe2 system (additional states associated with chemisorption are typically accompanied by an adsorption energy < −500 meV62). The absence of states formed in or near the band gap suggests that chloroform doping avoids introducing scattering sites that could degrade the mobility of WSe2.

Temporal and thermal stability of chloroform-doped WSe2

To evaluate the long-term stability of chloroform doping, we regularly measured the charge transport characteristics of doped monolayer WSe2 transistors for more than 8 months. Figure 4a shows the evolution of ID vs. VGS sweeps for a single doped monolayer WSe2 device over 243 days (> 8 months). The maximum drain current ID,max at VGS = −3.4 V, slightly decreases after 243 days from 113 μA/μm to 97.4 μA/μm. Figure 4b plots the forward and backward sweep VT,cc for devices with Lch = 1 μm, revealing a median negative shift of −0.18 V over the course of long-term testing. This small negative shift in VT could indicate a slight reduction in p-doping due to chloroform desorption.

a ID vs. VGS curves of a Lch = 1 μm device immediately after doping and after 6, 60, 134, and 243 days. b Threshold voltage (VT,cc) vs. days after doping for all Lch = 1 μm devices. VT,cc is extracted at a constant current of 10 nA/μm at VDS = −1 V for both forward and backward sweeps. c Drain current (both ID,max at VGS = −3.4 V and Ion at Vov = 1.5 V) vs. days post-doping for all Lch = 1 μm devices. For panels (b, c), a box plot was created for every group of data. The central mark of the box indicates the median, and the bottom and top edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. d ID vs. VGS curves of an undoped WSe2 device (Lch = 1 μm) at VDS = -1 V initially, then after annealing at 100, 150, and 200 °C. e ID vs. VGS curves of a doped WSe2 device (Lch = 1 μm) at VDS = −1 V initially, then after annealing at 100, 150 and 200 °C. f ID,max at VGS = −3.0 V after various annealing temperatures, for undoped (unfilled diamonds) and doped (filled circles) devices. For the annealing process, the devices are sequentially annealed in vacuum at ~10-4 Torr for 30 min at the given temperature. After annealing, the devices are cooled to room temperature for electrical measurement, then re-annealed at the next temperature.

Figure 4c summarizes the evolution of ID in 1 µm long devices as ID,max for VGS = -3.4 V and at Vov = 1.5 V. Chloroform doping remains remarkably stable over time, with the median ID,max retaining >96% after 6 days and >81% after 243 days. We note that the decrease in ID,max can be partially attributed to the negative VT shift because the Ion remains relatively stable. After 8 months, the final ID,max is still 76.1× higher than the initial undoped ID,max for the same set of devices. This demonstrates that the improved p-type performance from chloroform doping is highly stable over time. In contrast, other doping techniques (e.g. MoO313,63, O3 oxidation64) degrade rapidly in air, losing functionality over the course of several hours or days. The next-best reported example, nitric oxide, maintained performance after 24 days25. Additionally, the low RC from chloroform doping was maintained after 8 months (Supplementary Fig. 7). This stability of chloroform doping over time is consistent with the strong physisorption predicted from our DFT simulations (Fig. 3c, d).

Thermal stability is also critical to enable further processing. We examined the thermal stability of undoped and chloroform-doped WSe2 transistors by sequentially annealing them in vacuum for 30 min at 100 °C, 150 °C, and 200 °C. Figure 4d shows the ID vs. VGS of a control device, displaying a progressive decrease in hole current after each annealing step. This decline may result from the desorption of weakly-bound water molecules, which also contribute to p-doping65,66. Figure 4e plots the ID vs. VGS evolutions for a chloroform-doped device after the same annealing sequence. Similar to the undoped control device, the doped device exhibited a slight reduction in hole current after annealing at 100 °C and 150 °C. However, after the 200 °C anneal, the ID,max of the doped device dropped significantly to 3 × 10-3 μA/μm, comparable to the control device under similar annealing conditions. This suggests that chloroform desorbs at elevated temperatures, reverting the device to an undoped state. This is supported by activation energy calculations (Fig. 3d), which show that there is no additional barrier to desorption, leading to much faster desorption at higher temperatures.

A summary of ID,max across all annealing stages (i.e., the initial state and anneals at 100 °C, 150 °C, and 200 °C) shows that the doped devices remain >140× higher in ID,max after annealing at 100 °C and 150 °C (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 8). However, following the 200 °C anneal, there was a sharp drop in hole current of the doped devices, consistent with the desorption of chloroform and a reversal to the undoped state. This sequential annealing procedure suggests that 150 °C can be treated as a safe upper-bound for the thermal stability of chloroform doping on WSe2, although faster thermal ramping and cooling may reveal a thermal budget for higher temperatures. While this thermal budget could be a concern for direct-current (DC) operation with significant self-heating67,68, devices operating under high frequencies will heat up less. This is because the device switching speed is higher than the 2D device thermal time constant (typically from 30 to 300 ns69). In any case, this 150 °C thermal budget for chloroform stability enables compatibility with oxide encapsulation by atomic-layer deposition (ALD), which often occurs between 100 and 200 °C. This may also further enhance the thermal stability of the p-type doping, enable fabrication of top-gated devices, and allow for concurrent application of other doping techniques, such as solid charge transfer layers (e.g., MoOₓ, WOₓ).

Determination of chloroform location in a WSe2/oxide stack

To clarify the mechanism and stability of chloroform doping, we investigated its location relative to the WSe2. Figure 5a presents a 20 × 20 μm2 atomic-force microscopy (AFM) topography image of an exfoliated WSe2 flake in which the thickness increases from 2 to over 10 layers. The bilayer (2L) to four-layer (4L) region was measured in 2 × 2 μm2 scans before and after doping (Supplementary Fig. 9), yielding the height distributions shown in Fig. 5b. The peaks mark the height of the SiO2, 2L, 3L, and 4L WSe2 regions. There is no noticeable change in spacing between the WSe2 layers, but the height difference between the SiO2 and 2L WSe2 increases by >0.15 nm. This suggests that chloroform does not intercalate between the WSe2 layers, but rather that chloroform either (i) inserts at the SiO2/WSe2 interface, or (ii) adsorbs on top of every WSe2 layer. X-ray diffraction (XRD) reveals that the interplanar spacing remained constant at 0.645 nm after doping (Supplementary Fig. 10), supporting the conclusion that chloroform does not intercalate between WSe2 layers.

a Atomic-force microscopy (AFM) of an exfoliated WSe2 flake with various layer thicknesses. L denotes the number of WSe2 layers. b Height distribution of the exfoliated flake before (gray) and after (green) doping, in the 2–4L region (as marked in panel (a). The peaks mark the height of the SiO2, 2L, 3L, and 4L WSe2 regions. There is no noticeable change in spacing between WSe2 layers, but the difference between SiO2 and 2L WSe2 increases. Inset: schematic of chloroform inserting at the SiO2/WSe2 interface, causing an increase in height of the WSe2 layer relative to SiO2. Triangles denote the height of the 2L, 3L, and 4L WSe2 regions, matching the peaks in the height distribution. c Scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the exfoliated WSe2 flake as seen in panel (a). d–f Elemental mapping by Auger electron spectroscopy (AES) of a doped WSe2 flake of Se, Si, and Cl, respectively. The brighter pixels correspond to regions with higher elemental content. g Line scan of elemental Se, Si, and Cl content extracted from panel (d), showing an increase in Cl signal in the 2L WSe2 region.

We measured the dependence of chloroform adsorption on WSe2 thickness using Auger electron spectroscopy (AES). Figure 5c shows a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the exfoliated WSe2 flake from Fig. 5a, while Fig. 5d–f display AES elemental maps of Se, Si, and Cl. Figure 5g plots the AES signal intensities along the line in Fig. 5c. As a surface sensitive technique with an Auger electron escape depth of approximately 5 to 50 Å, AES confirms that the Se signal intensity scales with the WSe2 thickness (Fig. 5d). In contrast, the Cl signal is negligible outside the WSe2 region, peaks within the 2L WSe2 terrace, and diminishes significantly for thicker WSe2 layers (Fig. 5f, g).

AFM height mapping indicates uniform increases in height across the 2L, 3L, and 4L WSe2 regions after chloroform exposure (Fig. 5b), while AES mapping shows the highest Cl signal in the (thinnest) 2L region (Fig. 5f, g). This suggests that chloroform intercalates at the WSe2/oxide interface, as reported for graphene on SiO233, with thicker WSe2 regions attenuating the AES signals from Cl beneath the WSe2. This interfacial chloroform may enhance the WSe2 device performance by increasing the oxide/WSe2 separation and reducing the influence of interfacial oxide n-doping70 and trap states—which may contribute to the observed reduction in SS for doped WSe2 devices (Fig. 2f). Although this data set is convincing, further experimental work is required to definitively confirm the intercalation of chloroform. Notably, the correlation between the Cl signal and WSe2 regions suggests that WSe2 is necessary for chloroform adsorption (Fig. 5f). XPS is consistent with this observation, detecting a Cl peak only in substrate regions covered by monolayer WSe2 (Supplementary Fig. 11). In contrast, there is no apparent Cl peak in the bare substrate regions of chloroform-soaked samples.

We further assess the substrate dependence of our doping strategy and its implications for CMOS compatibility. While chloroform doping demonstrates reproducible p-type doping without leaving metallic residues on the surface, the sensitivity to standard wet-processing solvents (e.g., acetone) poses integration challenges (Supplementary Fig. 12a). Additionally, selective-area doping requires the development of protective strategies, such as encapsulation, that prevent dopant desorption (Supplementary Fig. 12b, c). Further experimental work is needed to optimize encapsulation strategies for localized doping. To further clarify the influence of the substrate, we extend our experiments to include WSe2 devices on SiO2 (Supplementary Fig. 13). These show comparable performance enhancement as those on HfO2 (~100× increase of ID, positive VT shift, and similar change in carrier concentration). This suggests that the doping mechanism is robust across different amorphous dielectrics.

Overall, this work presents a straightforward and stable p-doping method to achieve high-performance monolayer WSe2 transistors, while providing new mechanistic insights into solvent-based doping techniques. By achieving significant improvements in hole current, RC, and device stability, this method offers a viable path for future low-power 2D semiconductor applications.

Methods

Doping process

The WSe2 sample was immersed in as-purchased undiluted chloroform (SIGMA-Aldrich, No. 650498), in a watchglass-covered borosilicate beaker at standard room temperature (20-24 °C) and relative humidity (approx. 25%-65%) in a ventilated fume hood. The chloroform solvent was used without modification (as-purchased ≥99.9% chloroform). Unless indicated otherwise, the doping process occurred overnight (>8 h). Samples were exposed only to pure chloroform, as dilution with other solvents (e.g., acetone, IPA) could introduce co-dopant effects, complicating the interpretation of concentration-dependent trends. For device measurements, the doping process was performed after the initial device fabrication process was completed.

Material characterization

Raman measurements were taken on the Horiba Labram HR Evolution Raman system in the Stanford Nanofabrication Shared Facility, using 532 nm laser excitation at 1% nominal laser power (120 μW) and a spot size <1 μm in diameter. These parameters were selected to ensure minimal sample heating during measurement. For Raman and PL, a solid-source chemical vapor deposition (CVD) monolayer of WSe2 grown on sapphire was transferred onto 100 nm SiO2 before measurement. XPS was carried out using a PHI VersaProbe 4, equipped with a monochromatized Al Kα source (1486 eV) with a beam power of 50 W and beam energy of 15 kV, base pressure of 1.2 × 10-7 Pa, and pass energy of 224 eV (step size: 0.8 eV) and 55 eV (step size: 0.1 eV) for survey and high-resolution acquisitions, respectively.

Bulk WSe2 crystals were exfoliated with scotch tape onto oxygen-plasma cleaned silicon wafers with 100 nm thermal oxide. The exfoliated WSe2 was probed for Auger electron spectroscopy (AES), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and atomic-force microscopy (AFM) images in Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 9. AES mapping, composition analysis, and line scans on exfoliated WSe2 were performed on a PHI 700 Scanning Auger Nanoprobe. XRD measurements were conducted using a PANalytic Empyrean system with a Cu-Kα source. Exfoliated WSe2 flakes were probed with symmetric 2θ/ω scans. AFM was conducted on both the exfoliated WSe2 and on CVD-grown WSe2 on sapphire using a Bruker Dimension Icon in peak force mode with an NSC19 Al BS probe (nominal spring constant = 0.5 N/m).

Local back-gate device fabrication on HfO2 and electrical measurements

Continuous 2-inch CVD-grown monolayer WSe2 on sapphire was purchased from 2D semiconductors and transferred onto local back gates of 5.3 nm HfO2 with Cox = 2.8 μF/cm2. The local back gates were defined by lift-off 2 nm/8 nm Ti/Pt followed by the HfO2 gate dielectric by thermal atomic-layer deposition at 200 °C. Coarse contact pads were then defined by lift-off 2/20 nm Ti/Pt. Polystyrene (PS) was spin-coated on top of the WSe2 and then transferred in DI water. An O2 plasma treatment (100 W, 1 min) of the HfO2 dielectric was done before transferring the PS/WSe2 film to modify the substrate’s surface energy. The PS was then removed in toluene. Channel definition was done using electron-beam lithography and etched by XeF2 (2.5 T, 30 s, 3 cycles) to define a channel width of 1 μm. Electron-beam lithography was used to pattern the fine contacts. Pd/Au (20/20 nm) was e-beam evaporated at ∼10−8 Torr. Electrical measurements were performed at 296 K in a Janis ST-100 vacuum probe station at ∼10−4 Torr, using a Keithley 4200 semiconductor parameter analyzer.

Cryogenic measurements were conducted in a Lakeshore cryoprobe station at ~10-6 Torr, using a Keithley 4200 semiconductor parameter analyzer. The sample was slowly cooled and left to stabilize overnight at 10 K before electrical testing.

For contact resistance (RC) extraction, a pseudo-transfer length method (TLM) was used, as devices made were single devices with varying channel lengths. In this method, all devices at a certain channel length were used for RC extraction. The total resistance in kΩ·μm (normalized by the channel width) can be expressed as RTOT = 2RC + Rch = 2RC + RshLch, where Rsh is the sheet resistance of the channel and Rch is the channel resistance. RC is evaluated by plotting RTOT versus Lch and drawing a linear fit through all data points, and the y-intercept at Lch = 0 gives 2RC. The RC is extracted for each gate overdrive Vov = |VGS – VT | , with VT from the constant-current method at ID = 10–2 μA/μm.

Low temperature photoluminescence

Low-temperature photoluminescence spectroscopy was conducted with a 532 nm excitation laser, ∼1 μm spot size, and 600 l/mm spectrometer grating. The laser power was fixed at 60 μW, unless otherwise noted. The emission was collected using a 50× objective with a numerical aperture of 0.55, with 2 s acquisition times and 2 accumulations. The sample was cooled to a base temperature of ~6.7 K, then warmed up using a resistive heater for temperature-dependent measurements. For temperature-dependent experiments, the sample sat for 30 min at the desired temperature to stabilize before collecting the spectra. For this experiment, CVD-grown WSe2 was wet transferred (as described above) onto 100 nm SiO2/p++ Si, then half of the chip was cleaved and subjected to an overnight chloroform soak. Several spots across both the control and doped samples were examined to ensure peak shape consistency. Finally, peak fitting was conducted in Origin using a Gaussian-Lorentzian blend.

Temporal and thermal stability testing

For time stability measurements, devices were stored at room temperature in a nitrogen dry box under continuous N2 purge, with relative humidity maintained at ~5%. For thermal stability testing, initial electrical measurements were performed at 296 K in a Janis ST-100 vacuum probe station at ∼10−4 Torr, using a Keithley 4200 semiconductor parameter analyzer. The samples were then in-situ annealed at 100 °C, held for 30 min, then left to cool down for >5 h. Electrical measurements were taken at 300 K in a vacuum. This process was then repeated at 150 °C and 200 °C, respectively, with device measurements in between, without breaking the vacuum. At present, the impact of ambient humidity and oxygen on the long-term stability of chloroform doping remains an open question and warrants future investigation, particularly in the context of encapsulated or integrated device architectures.

Density functional theory (DFT) simulations

First, a variable cell relaxation was performed to optimize the lattice coordinates within the monolayer WSe2 primitive cell. The optimized primitive cell was then scaled to a 5 × 5 supercell, interfaced with a chloroform molecule, and then subjected to a fixed cell relaxation to determine the WSe2/chloroform atomic coordinates. Both the Cl-facing and H-facing orientations were considered, where the chlorine or hydrogen atom of the chloroform molecule was oriented towards the WSe2. Quantum ESPRESSO 7.171 was used for all DFT simulations, and the van der Waals interactions between the chloroform and WSe2 monolayer were modeled using the vdW-DF-C09 correction. For all self-consistent calculations, we use Γ-point sampling for all 5 × 5 supercells, and k-point grids of 3 × 3 × 1 and 7 × 7 × 1 for the 3 × 3 and 2 × 2 supercells, respectively. We perform non-self-consistent calculations on a 15 × 15 × 1 k-point grid prior to extracting the density of states for the WSe2 + chloroform assemblies. All DFT calculations use projector-augmented wave pseudopotentials with kinetic energy cutoffs and charge density cutoffs of 50 and 400 Ry, respectively. We use the “Bader” code72 for Bader charge analysis, PyProcar73 for plotting projected density of states and band structures, and VESTA74 for plotting isosurfaces. We note that in this work, we consider only interactions between the chloroform and WSe2 without an insulator or substrate. Including the amorphous SiO2 and HfO2 would improve the accuracy of our simulations by capturing chloroform-substrate interactions; however, simulating this interface is computationally demanding, and we leave it as a promising research direction.

Other orientations of chloroform on WSe2 are certainly possible, although a rigorous test for the most favorable orientation remains outside of the scope of this study. We confirmed that the Cl-facing orientation is stable compared to other similar random orientations by rotating the chloroform molecule by 5 degrees (i.e., tilting the C-H bond 5 degrees relative to the surface normal) and then re-relaxing the system. The chloroform molecule returned close to its original position and total energy (to within 2 meV), suggesting that this orientation is indeed favorable.

Data availability

Relevant data supporting the key findings of this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Information file. All raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

O’Brien, K. P. et al. Process integration and future outlook of 2D transistors. Nat. Commun. 14, 6400 (2023).

Kim, K. S. et al. The future of two-dimensional semiconductors beyond Moore’s law. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 895–906 (2024).

Razavieh, A., Zeitzoff, P. & Nowak, E. J. Challenges and limitations of CMOS Scaling for FinFET and beyond architectures. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 18, 999–1004 (2019).

Shen, P.-C. et al. Ultralow contact resistance between semimetal and monolayer semiconductors. Nature 593, 211–217 (2021).

Li, W. et al. Approaching the quantum limit in two-dimensional semiconductor contacts. Nature 613, 274–279 (2023).

Allain, A., Kang, J., Banerjee, K. & Kis, A. Electrical contacts to two-dimensional semiconductors. Nat. Mater. 14, 1195–1205 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. Low-resistance metal contacts to encapsulated semiconductor monolayers with long transfer length. Nat. Electron. 5, 579–585 (2022).

Lin, Y.-T. et al. Antimony–platinum modulated contact enabling majority carrier polarity selection on a monolayer tungsten diselenide channel. Nano Lett. 24, 8880–8886 (2024).

Hoang, L. et al. Enabling P-type conduction in bilayer WS2 with NbP topological semimetal contacts. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2409.18926 (2024).

Kozhakhmetov, A. et al. Controllable p-type doping of 2D WSe2 via vanadium substitution. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2105252 (2021).

Qin, Z. et al. Growth of Nb-doped monolayer WS2 by liquid-phase precursor mixing. ACS Nano 13, 10768–10775 (2019).

Kanahashi, K. et al. Dimensionality-induced transition from degenerate to nondegenerate states in Nb-doped WSe2. ACS Nano 19, 10244–10254 (2025).

Cai, L. et al. Rapid flame synthesis of atomically thin MoO3 down to monolayer thickness for effective hole doping of WSe2. Nano Lett. 17, 3854–3861 (2017).

Pang, C. S. et al. Atomically controlled tunable doping in high-performance WSe2 devices. Adv. Electron. Mater. 6, 1901304 (2020).

Lin, Y.-T. et al. Photolithography-induced doping and interface modulation for high-performance monolayer WSe2 P-type transistors. Nano Lett. 25, 3571–3578 (2025).

Kim, I. et al. Low contact resistance WSe2 p-type transistors with highly stable, CMOS-compatible dopants. Nano Lett. 24, 13528–13533 (2024).

Hung, T. Y. T. et al. pMOSFET with CVD-grown 2D semiconductor channel enabled by ultra-thin and fab-compatible spacer doping. In 2022 International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM). Vol. 2022 7.3.1–7.3.4 (IEEE, 2022).

Oberoi, A. et al. Toward high-performance p-type two-dimensional field effect transistors: contact engineering, scaling, and doping. ACS Nano 17, 19709–19723 (2023).

Chiang, C.-C. et al. Air-stable P-doping in record high-performance monolayer WSe2 devices. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 43, 319 (2022).

Fang, H. et al. High-performance single layered WSe2 p-FETs with chemically doped contacts. Nano Lett. 12, 3788–3792 (2012).

Ho, P. H. et al. High-performance WSe2 top-gate devices with strong spacer doping. Nano Lett. 23, 10236–10242 (2023).

Choi, M. S. et al. Lateral MoS2 p-n junction formed by chemical doping for use in high-performance optoelectronics. ACS Nano 8, 9332–9340 (2014).

Xie, J. et al. Low resistance contact to P-type monolayer WSe2. Nano Lett. 24, 5937–5943 (2024).

Pack, J. et al. Charge-transfer contacts for the measurement of correlated states in high-mobility WSe2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 948–954 (2024).

Lan, H.-Y. et al. Uncovering the doping mechanism of nitric oxide in high-performance P-type WSe2 transistors. Nat. Commun. 16, 4160 (2025).

Ghosh, S. et al. High-performance p-type bilayer WSe2 field effect transistors by nitric oxide doping. Nat. Commun. 16, 5649 (2025).

Lee, D. et al. Remote modulation doping in van der Waals heterostructure transistors. Nat. Electron. 4, 664–670 (2021).

Wang, Y., Sarkar, S., Yan, H. & Chhowalla, M. Critical challenges in the development of electronics based on two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Electron. 7, 638–645 (2024).

Yang, L. et al. Chloride molecular doping technique on 2D materials: WS2 and MoS2. Nano Lett. 14, 6275–6280 (2014).

Devi, D. S. & Mohapatra, N. R. Exploring p-type contact for monolayer WS2 FETs using Halogen Doping and Intermediate Layers. ACS Omega 9, 50634–50641 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Improvement of P-type contact in WSe2 field-effect transistors via defect engineering. Nano Lett. 25, 2803–2809 (2025).

Zou, T. et al. High-performance solution-processed 2D P-type WSe2 transistors and circuits through molecular doping. Adv. Mater. 35, e2208934 (2023).

Kim, H. H. et al. Substrate-induced solvent intercalation for stable graphene doping. ACS Nano 7, 1155–1162 (2013).

Choi, J., Zhang, H., Du, H. & Choi, J. H. Understanding solvent effects on the properties of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 8864–8869 (2016).

Poddar, P. K. et al. Resist-free lithography for monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nano Lett. 22, 726–732 (2022).

Chou, A.-S. et al. High-performance monolayer WSe2 p/n FETs via antimony-platinum modulated contact technology towards 2D CMOS Electronics. In 2022 International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 7.2.1–7.2.4 (IEEE, 2022).

O’Brien, K. P. et al. Advancing 2D monolayer CMOS through contact, channel and interface engineering. In 2021 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 7.1.1-7.1.4 (IEEE, 2021).

Maxey, K. et al. 300 mm MOCVD 2D CMOS materials for more (than) Moore scaling. In 2022 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology and Circuits (VLSI Technology and Circuits) 419–420 (IEEE, 2022).

Lan, H.-Y., Tripathi, R., Liu, X., Appenzeller, J. & Chen, Z. Wafer-scale CVD monolayer WSe2 p-FETs with Record-high 727 μA/μm Ion and 490 μS/μm gmax via hybrid charge transfer and molecular doping. In 2023 International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 1–4 (IEEE, 2023).

Chou, A.-S. et al. Status and performance of integration modules toward scaled CMOS with transition metal dichalcogenide channel. In 2023 International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 1–4 (IEEE, 2023).

Ortiz-Conde, A. et al. A review of recent MOSFET threshold voltage extraction methods. Microelectron. Reliab. 42, 583–596 (2002).

Lockhart De La Rosa, C. J. et al. Highly efficient and stable MoS2 FETs with reversible n-doping using a dehydrated poly(vinyl-alcohol) coating. Nanoscale 9, 258–265 (2017).

Ber, E., Grady, R. W., Pop, E. & Yalon, E. Uncovering the different components of contact resistance to atomically thin semiconductors. Adv. Electron. Mater. 9, 2201342 (2023).

Baikadi, P., Vandenberghe, W., Reyntjens, P., Kim, R. & Van de Put, M. Quantum transport study of transition-metal dichalcogenide top-contacted geometries investigating the impact of nonuniform doping, dielectric environment, and image-force barrier lowering. Phys. Rev. Appl. 22, 064058 (2024).

Illarionov, Y. Y. et al. Insulators for 2D nanoelectronics: the gap to bridge. Nat. Commun. 11, 3385 (2020).

Liu, M. et al. Periodical Ripening for MOCVD Growth of Large 2D Transition Metal Dichalcogenide Domains. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2212773 (2023).

Lyons, T. P. et al. The valley Zeeman effect in inter- and intra-valley trions in monolayer WSe2. Nat. Commun. 10, 2330 (2019).

Jadczak, J. et al. Probing of free and localized excitons and trions in atomically thin WSe2, WS2, MoSe2 and MoS2 in photoluminescence and reflectivity experiments. Nanotechnology 28, 395702 (2017).

Wu, Z. et al. Defects as a factor limiting carrier mobility in WSe2: a spectroscopic investigation. Nano Res 9, 3622–3631 (2016).

Wu, Z. et al. Defect activated photoluminescence in WSe2 monolayer. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 12294–12299 (2017).

Greben, K., Arora, S., Harats, M. G. & Bolotin, K. I. Intrinsic and extrinsic defect-related excitons in TMDCs. Nano Lett. 20, 2544–2550 (2020).

Munson, K. T. et al. Influence of substrate-induced charge doping on defect-related excitonic emission in monolayer MoS2. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 7850–7856 (2024).

Amani, M. et al. Near-unity photoluminescence quantum yield in MoS2. Science 350, 1065–1068 (2015).

Schwarz, A. et al. Thiol-based defect healing of WSe2 and WS2. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 7, 59 (2023).

Park, J. H. et al. Defect passivation of transition metal dichalcogenides via a charge transfer van der Waals interface. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701661 (2017).

Kong, L., Enders, A., Rahman, T. S. & Dowben, P. A. Molecular adsorption on graphene. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 26, 443001 (2014).

Zhou, C., Yang, W. & Zhu, H. Mechanism of charge transfer and its impacts on Fermi-level pinning for gas molecules adsorbed on monolayer WS2. J. Chem. Phys. 142, 214704 (2015).

Szary, M. J. Toward high selectivity of sensor arrays: enhanced adsorption interaction and selectivity of gas detection (N2, O2, NO, CO, CO2, NO2, SO2, AlH3, NH3, and PH3) on transition metal dichalcogenides (MoS2, MoSe2, and MoTe2). Acta Mater. 274, 120016 (2024).

Nam, T., Seo, S. & Kim, H. Atomic layer deposition of a uniform thin film on two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vacuum Surfaces Film. 38, 030803 (2020).

Parija, A. et al. Electronic structure modulation of MoS2 by substitutional Se incorporation and interfacial MoO3 hybridization: Implications of Fermi engineering for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution and oxygen evolution. Chem. Phys. Rev. 2, 011401 (2021).

Mehmood, F. & Pachter, R. Density functional theory study of chemical sensing on surfaces of single-layer MoS2 and graphene. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 164302 (2014).

Paso, K. G. In Microbial Biodegradation and Bioremediation. 109–143 (Elsevier, 2022).

Xie, L. et al. Electrical measurement of non-destructively p-type doped graphene using molybdenum trioxide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 012112 (2011).

Yamamoto, M., Nakaharai, S., Ueno, K. & Tsukagoshi, K. Self-limiting oxides on WSe2 as controlled surface acceptors and low-resistance hole contacts. Nano Lett. 16, 2720–2727 (2016).

Ovchinnikov, D., Allain, A., Huang, Y. S., Dumcenco, D. & Kis, A. Electrical transport properties of single-layer WS2. ACS Nano 8, 8174–8181 (2014).

Qiu, H. et al. Electrical characterization of back-gated bi-layer MoS2 field-effect transistors and the effect of ambient on their performances. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 123104 (2012).

Wang, M. A. & Pop, E. Monte Carlo simulation of electrical transport with joule heating and strain in monolayer MoS2 devices. Nano Lett. 25, 6841–6847 (2025).

Yalon, E. et al. Energy dissipation in monolayer MoS2 electronics. Nano Lett. 17, 3429–3433 (2017).

Islam, S., Li, Z., Dorgan, V. E., Bae, M.-H. & Pop, E. Role of joule heating on current saturation and transient behavior of graphene transistors. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 34, 166–168 (2013).

Ko, K. et al. Competition between bipolar conduction modes in extrinsically p-doped MoS2: interaction with gate dielectric matters. ACS Nano 19, 1630–1641 (2025).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Quantum ESPRESSO toward the exascale. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 154105 (2020).

Henkelman, G., Arnaldsson, A. & Jónsson, H. A fast and robust algorithm for Bader decomposition of charge density. Comput. Mater. Sci. 36, 354–360 (2006).

Herath, U., Tavadze, P. & He, X. PyProcar: a Python library for electronic structure pre/post-processing. Comput. Phys. Commun. 251, 107080 (2020).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Mortelmans, W. et al. Record performance in GAA 2D NMOS and PMOS using monolayer MoS2 and WSe2 with scaled contact and gate length. In 2024 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology and Circuits (VLSI Technology and Circuits) 1–2 (IEEE, 2024).

Dorow, C. et al. Advancing monolayer 2-D nMOS and pMOS transistor integration from growth to Van der Waals interface engineering for ultimate CMOS scaling. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 68, 6592–6598 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. P-type electrical contacts for 2D transition-metal dichalcogenides. Nature 610, 61–66 (2022).

Kim, K. S. et al. Non-epitaxial single-crystal 2D material growth by geometric confinement. Nature 614, 88–94 (2023).

Penumatcha, A. et al. High mobility TMD NMOS and PMOS transistors and GAA architecture for ultimate CMOS Scaling. In 2023 International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 1–4 (IEEE, 2023).

Wang, X., Xiong, X., Shi, X., Gu, C. & Wu, Y. Optimized electrical properties of p-type field-effect transistors based on WSe2 grown at moderate temperatures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 261901 (2023).

Dorow, C. J. et al. Exploring manufacturability of novel 2D channel materials: 300 mm wafer-scale 2D NMOS & PMOS using MoS2, WS2, & WSe2. In 2023 International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 1–4 (IEEE, 2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) FuSe2 grant 2425218 and the TSMC-Stanford SystemX Alliance. L.H. was supported by the Sandia Microelectronics: Accelerating Research Talent (SMART) Internship. L.H., R.K.A.B., T.P., and E.P. acknowledge support from SUPREME, a JUMP 2.0 center within the Semiconductor Research Corporation (SRC), sponsored by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). R.K.A.B. was supported by the Stanford Graduate Fellowship and the NSERC PGS-D programs. T.P. acknowledges support from the NSF MPS-Ascend postdoctoral fellowship. A.P.S. and F.L. were supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, CPIMS Program, under award no. DE-SC0026181. Part of this work was performed at the Stanford Nanofabrication Facility (SNF) and Stanford Nano Shared Facilities (SNSF), supported by NSF award ECCS-2026822. The authors thank Krishna C. Saraswat, Johnathan Georgaras, Qingrui Cao, Akash Ramdas, Emily Chen, and Alex Shearer for valuable discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.H. fabricated the devices and conducted the device measurements and analysis under the supervision of A.J.M. and E.P. L.H. conducted the AFM, Raman, and Auger measurements. R.K.A.B. performed the DFT simulations. A.T.H. performed the CVD WSe2 material growth. T.P. and L.H. performed the low-temperature PL characterization and analysis with the help of A.P.S. under the supervision of F.L. Z.Z. performed the XRD with L.H. M.H. performed the WSe2 exfoliation. M.J. performed SiO2 thermal oxidation and provided initial fabrication support. L.H. and A.J.M. wrote the paper. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Cheol-Joo Kim, who co-reviewed with Woo-Ju Lee, Soumya Sarkar, and the other anonymous reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoang, L., Bennett, R.K.A., Hoang, A.T. et al. Low resistance p-type contacts to monolayer WSe2 through chlorinated solvent doping. Nat Commun 17, 718 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65604-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65604-3