Abstract

Precisely constructing homochiral helical nanostructures from achiral molecules by non-covalent interactions remains challenging owing to the untraceable handedness control at different hierarchical levels. Here, we present an aurophilicity-assisted orthogonal assembly strategy, enabling not only the homochiral assembly of an achiral carbene-anchored trinuclear gold cluster with chiral amines but also the inversion of circularly polarized luminescence (CPL). This gold cluster could spontaneously form random right- or left-handed helices, while introduction of chiral amines effectively drives the formation of hierarchically homochiral twists with |glum| of 10−2, directed by inherent aurophilicity of gold cluster and orthogonal intermolecular C-H⋅⋅⋅O/N interactions. Furthermore, by fine-tuning the assembly conditions from DMF to DMF/H2O solvent, the morphology of assemblies can be specifically controlled, resulting in inversion of CPL signals. This study highlights the potential of aurophilicity-driven orthogonal assembly strategy in effectively controlling hierarchical chirality and paves the way for advancing chiral metallo-superstructures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Constructing functional self-assembly through non-covalent interactions is of great scientific value for mimicking biological systems to build ordered nanostructures, and developing smart materials. A variety of non-covalent interactions, such as hydro-/halogen bonds, π–π stacking interactions, metallophilic interactions, metal coordination bonds, have been used to join building elements to fabricate supramolecular assemblies1,2,3. Recently, researchers have exploited supramolecular assembly strategy to establish helical structures based on emitters to achieve circularly polarized luminescence (CPL)-active materials with attractive performance, including high glum4,5, tunable luminescence6,7,8 and chirality inversion9,10,11. However, owing to its weak intensity, it is difficult to build target structures with ideal properties through only one type of non-covalent bond.

Orthogonal self-assembly12,13,14 is a way to achieve synergistic effect of two or more independent non-covalent supramolecular interactions, which occur without crosstalk. The resulting assemblies can exhibit more excellent properties than that obtained by using a single force15,16. As a typical metallophilic interactions, aurophilic interactions17, also known as aurophilicity are van der Waals interactions, but unusually strong ones because of relativistic effects. Aurophilicity are fundamental to assembly structure and luminescent properties of Au(I) complexes18,19,20. In the absence of steric hindrance, such unique aurophilic interactions21 were found not to be easily disturbed by other non-covalent interactions, thereby usually cause linear mononuclear complexes or planar trinuclear Au(I) clusters to self-organize in extended columnar stacking in one dimension (1D) direction22,23,24 with an intermolecular equilibrium Au · ··Au distances in the range of ca. 2.50–3.50 Å. Therefore, the aurophilic interactions can be used as an ideal driving force to direct orthogonal assembly. Therein, benefiting from aurophilic interactions, cyclic trinuclear complexes (CTCs) of Au(I) generally adopt long columnar assemblies with well-documented assemblies and luminescent properties24,25. Aida and co-workers have reported that achiral pyrazole-anchored dendritic CTCs self-assembled into luminescent superhelical fibers with micrometer-scale via metal-metal interactions26. Recently, Li et al. synthesized two achiral Au3(4-Clpyrazolate)3 and Au3(4-Brpyrazolate)3 complexes showing high-efficiency near-infrared luminescence with (+) or (−)-CPL27. However, in the above works, both chirality of the morphology and CPL properties could not be effectively regulated. Although a large number of CTCs have been reported, CTCs emitting controllable CPL properties were rarely reported and the formation mechanism of helical structure remains unclear.

As a typical kind of CTCs, aromatic acyclic amino carbene-anchored Au3 cluster28 exhibit flexible propeller-like conformation, where the peripheral aromatic rings can rotate freely in solution state. While in solid state, the conformation will be rigidified by intermolecular interactions, which could lead to formation of either right-handed (P)- or left-handed (M)-conformation. For example, Espinet et al. designed a pyridine-modified Au3 carbeniates28, which simultaneously adopted P- or M-conformation in crystal controlled by the aurophilic interactions, hydrogen bonding and steric hindrance. We anticipated that under chiral condition, such achiral Au3 carbeniates could be easily induced to adopt homochiral conformation and further form chiral 1D assemblies.

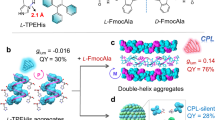

In this study, we report construction and morphological regulation of homochiral assembly from an achiral C3‑symmetric [Au3(p-CNPhN=COMe)3] cluster, donated as p-CN-Au3 (Fig. 1a), directed by aurophilicity and orthogonal C-H · · · O/N interactions. Cooling a hot p-CN-Au3 solution resulted in mixtures of P- and M-helical fibers. Introduction of R- or S-tetrahydrofurfurylamine(R- or S-THFA) enabled separation of the racemic assemblies. The hierarchical homochiral structure obtained by drop-casting their DMF solution exhibited excellent CPL properties. In this case, intermolecular C-H · · · N and C-H · · · O interactions successfully induced chirality transfer from R- or S-THFA to p-CN-Au3. Then, aurophilic interactions drive asymmetric growth of the chiral adducts (p-CN-Au3 and R-/S-THFA) in 1D direction to form chiral architectures. Moreover, with extra addition of poor-solvents H2O molecules, chirality and chiroptical properties could be easily inversed. Thus, an orthogonal assembly strategy directed by aurophilicity and C-H · · · O/N interactions was proposed and verified to enable the generation and inversion of homochirality. This study further enhances the understanding of the chiral evolution process, from the molecular structure to the hierarchical supramolecular scale.

Chemical structures of a p-CN-Au3 and b m-CN-Au3. c UV–Vis absorption and d PL spectra of p-CN-Au3 in DMF/H2O solution under different fw. fw indicates the volume fraction of water in the solvent mixture (excitation wavelength: 365 nm). e, f, g Enantiomer molecular conformation, dimeric stacking patterns and packing structures in p-CN-Au3 crystals. h PL spectra and i time-resolved luminescence decay curves of p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3 crystals detected at different wavelength, and the inserted images in (h) are the optical images of crystals under UV excitation (excitation wavelength: 365 nm, scale bar: 300 μm). j HOMO and LUMO orbitals at PBE0/def2-SVP level of p-CN-Au3. Transition from HOMO to LUMO + 1 orbitals contribute 90.8 % of the S0 → S2 process, of which the oscillator strength (f) is 0.0708.

Results

Synthesis of p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3

Two acyclic amino carbene (AAC)-anchored trinuclear gold clusters [Au3(p-CNPhN=COMe)3] and [Au3(m-CNPhN=COMe)3], donated as p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3 (Fig. 1a,b), were synthesized from the reactions of mononuclear AAC Au(I) complexes and (THT)AuCl (THT = tetrahydrothiophene, see Supplementary Information for details, Figs. S1-S12) in CH2Cl2 in the presence of trimethylamine (TEA), which induces N-H deprotonation to generate a monoanionic AAC ligand. The purity and structure of charge-neutral p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3 were verified by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra (Figs. S13 and S14), mass spectra (MS) (Figs. S15 and S16), element analysis, Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy (Figs. S17 and S18). After recrystallization, blue-emitting microcrystals were obtained. The crystalline phase purity was confirmed by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) (Fig. S19).

Photophysical properties of p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3

UV–Vis absorption spectrum of the monomeric p-CN-Au3 in dilute dimethyl formamide (DMF) exhibited absorption maximum at 267 nm (Fig. 1c), which was mainly originated from the transition based on metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT)29. No obvious emission was observed from this dilute DMF solution. Adding small amounts of anti-solvent H2O led to a new sharp absorption band at 264 nm, which were continually enhanced and slowly blue-shifted to 261 nm when water fractions (fw) reached to 20%. This spectroscopic evolution indicates that the p-CN-Au3 have experienced a structural alteration in its ground-state configuration driven by H2O molecules, resulting in a modification of the electronic transition energy levels. Furthermore, when fw reached to 40%, the sharp absorption band happened to be weakened, while novel low-energy (LE) absorption band at 325-350 nm occurred. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) results indicated the generation of aggregates (Fig. S20). Furthermore, the particle size of the formed aggregates increases progressively with rising water content. At this point, the aggregates showed a turn-on cyan emission. In mixture with fw 95%, the emission peak intensity was 5 times larger than that of fw 40% (Figs. 1d and S21). Similarly, m-CN-Au3 was also non-emissive in dilute DMF solution, while its aggregate showed blue emission band at 517 nm, indicating aggregate-induced emission (AIE) properties (Fig. S22).

Crystal structure of p-CN-Au3

To achieve in-depth insights on the luminescent properties and stacking structures, single-crystal X-ray crystallography (SCXRD) technology was applied. High-quality single-crystals of p-CN-Au3 were grown from slow evaporation of CH2Cl2 solution at 4 °C. Unfortunately, the SCXRD data of m-CN-Au3 were failed to be achieved. The X-ray data of p-CN-Au3 are summarized in Table S1, and X-ray molecular structure of p-CN-Au3 is described in Fig. 1e–g and S23-S28. It crystallizes in the centrosymmetric (achiral) P−1 space group, where the individual planar molecules aggregate along the a-axis to form extended stacks (Fig. 1f). There are one crystallographically independent trinuclear AuI cluster and two CH2Cl2 molecules in the asymmetric unit (Fig. S24). As anticipated, the center geometry of p-CN-Au3 features a typical Au3(AAC)3 structure25, where the Au3 triangular were bridged by three C = N groups to form Au3C3N3 nine-membered ring. The distances of Au-C coordinate bonds are in the range of 1.984-1.999 Å (Table S2). The intramolecular Au · ··Au distances are 3.247, 3.258, and 3.331 Å (Fig. 1e), which are less than 3.50 Å, indicating the presence of weak aurophilic interactions20 within the Au3 moiety. Interestingly, all three peripheral p-cyanophenyl groups are tilted like the blades of a propeller relative to the Au3C3N3 ring, but making two angled counterclockwise and one angled clockwise. The torsion angles with the plane defined by three gold atoms are 45.72°, 34.02° and 48.91° (Fig. S25).

Along a-axis (Fig. 1f), p-CN-Au3 molecules stack in 1D molecular chains with alternating intermolecular Au · ··Au distances of 3.235 and 3.930 Å. Every two neighboring molecules (A1 and A2) with Au · ··Au separations of 3.235 Å form a dimer via dual aurophilic interactions. To minimize steric hindrance, p-CN-Au3 organize in staggered orientation, leading to a chair-like pattern of six gold atoms. Additionally, the formation of chair-like pattern is also benefiting from the multiple intermolecular forces (Fig. S26 and Table S3), including C-H · · · N (2.912 Å), C-H · · · O (2.725 and 3.011 Å), and C-H · ··π (2.677 and 2.624 Å). Notably, the A1 and A2 within a dimer are mirror-symmetric (Fig. 1e), which possesses an inversion center (Fig. S27) and further renders the crystal centrosymmetric and thus racemic. Additionally, dimers interact via multiple C-H · · · O and C-H · · · N (Fig. S28 and Table S4) interactions to form an extended chain arrangement. The dimeric motifs show two Au · ··Au separations of 3.930 Å, which are considerably longer than typical aurophilic interactions of 3.2 to 3.7 Å. CH2Cl2 molecules are accommodated in the space created by the molecular columns (Fig. 1g). Moreover, as observed in other reported Au3 clusters27, the rod-shape crystals (Fig. 1h, insets) indicate that p-CN-Au3 crystals might grow along the direction of Au3 packing, driving by multiple Au · ··Au interactions.

Both p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3 crystals displayed similar blue emission profiles (Fig. 1h), peaking at 460 and 440 nm with absolute photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY, ΦPL) of 5.74% and 4.88% at room temperature (Table S5), respectively. The time-resolved luminescent decay curves of p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3 revealed that their emission showed a microsecond-scale excited-state lifetime of 7.85 and 1.86 μs, respectively, indicating phosphorescence properties (Fig. 1i, Table S5). The PL spectra of their crystals were further recorded under nitrogen and oxygen atmospheres (Fig. S29). The observed enhancement in PL intensity under nitrogen atmosphere confirms that oxygen could quench the excited states, thereby supporting the assignment of the luminescence in the p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3 crystal to triplet-state phosphorescence emission. The TD-DFT calculation (see Supplementary Information for detail) reveals that the transition from HOMO to LUMO + 1 makes a major contribution (90.8 %) to the S0 → S2 process, of which the oscillator strength (f) is 0.0708 (Fig. 1j and S30, Table S6). The HOMO is mainly localized on the intermolecular Au · ··Au interactions within the dimer, while LUMO + 1 is predominantly delocalized on the π-bonding orbital of AAC ligand, correspondingly that the S0 → S2 transitions is assigned as metal-metal to ligand charge transfer (3MMLCT).

Self-assembly behaviour of p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3

In solution state, p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3 are achiral, as the Cphe-N bonds in the AAC moieties could rotate freely. It was reported that pyridine-modified Au3(AAC)328 took fixed P- or M-conformations in crystal (Fig. S31a). We anticipated that such fan-shaped p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3 molecules could be able to adopt homochiral conformation to form chiral assembly, when symmetry breaking occurred. The above slowly thermodynamic crystallization process resulted in racemes, but we speculated that whether the symmetry breaking phenomenon can be achieved by the rapidly kinetic process. Thus, rapid cooling of hot DMF or CH2Cl2 solutions were utilized to prepare precipitated aggregates of p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3. Morphologies of aggregates were carefully analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). SEM images of the aggregates from DMF clearly showed extended and flexible helical structure with random P- or M-helicity (Fig. 2a-c), although the p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3 are devoid of any chiral centers. The helices are not single-stranded but formed by winding several thin fibers. In the case of CH2Cl2 (Fig. 2d), discrete and short P- or M-spiral rods were observed for p-CN-Au3, while m-CN-Au3 showed a flower-like architecture composed of spiral rods (Fig. 2e,f). Nevertheless, the aggregates exhibited silent circular dichroism (CD) and CPL due to the simultaneous existence of P- or M-chiral assembly. According to PL spectra and lifetime decay curves (Fig. S32 and Table S7), the helical assemblies also showed blue phosphorescent emission with microsecond lifetime, indicating that they are formed by the supramolecular assembly of Au3(AAC)3 through Au · ··Au interactions27,29. However, the handedness of the helices were not controllable.

Chiral co-assembly of p-CN-Au3 with R-/S-THFA

It was reported that the chirality of emitters can be controlled effectively by incorporating with chiral medium30,31. We intended to prepare chiral co-assembly of p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3 by introducing small chiral amine. R-/S-THFA were selected as the chiral inducer to co-assembly with p-CN-Au3 (Figs. 3a and S33), as the –O– and –NH2 groups could act as hydrogen bond receptors and donors, respectively. The p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3 are slightly soluble in DMF at room temperature, whereas R-/S-THFA are DMF soluble. In a typical experimental protocol, for initializing the co-assembly, R-/S-THFA were added into p-CN-Au3 suspension in DMF, which turned into clear homogeneous solution after slightly ultrasound (Fig. 3a and S34). The significant solubilization effect demonstrated the strong interplay between p-CN-Au3 and R-/S-THFA. Thus, R-/S-THFA were expected to co-assembly with p-CN-Au3 to induce supramolecular homochirality.

a Samples of p-CN-Au3 and p-CN-Au3/R-THFA (molar ratio, 1:3) assemblies under natural light. b Absorption spectra of p-CN-Au3/R-THFA assemblies with different molar ratios of R-THFA. c Absorption spectra of p-CN-Au3/R-THFA (molar ratio, 1:3) assemblies under different concentration. d CD spectra of R-THFA and p-CN-Au3/R-THFA (molar ratio, 1:3) in DMF. e Luminescent images of p-CN-Au3/R-THFA (molar ratio, 1:3) assemblies. f CD and g CPL spectra of p-CN-Au3/THFA assemblies with different molar ratios. h–m SEM images of p-CN-Au3/THFA assemblies with different molar ratios (1:1, 1:3 and 1:30).

The synergistic interactions between p-CN-Au3 and R-/S-THFA were probed by both UV-Vis absorption and CD spectra, as shown in Fig. 3b-d. As comparison, no obvious absorption and CD band (Fig. S35) at around 225-350 nm were observed for the R-THFA in DMF. After addition of 1.0 equiv. of R-THFA, besides a weak decrease of the absorption band of p-CN-Au3 at 252 nm, a nonnegligible bathochromic-shift from 268 to 276 nm were observed. Furthermore, when R-THFA increased to 2.0 equiv., the band further redshifted to 288 nm with slight reduction, suggesting that the co-assembly between p-CN-Au3 and R-THFA occurred. We found that with concentration increasing, the co-assembly binding force became stronger, as the intensity of LE absorption peak (288 nm) gradually exceeded that of the high-energy (HE) absorption peak (252 nm) and became the maximum peak (Fig. 3c). Correspondingly, silent Cotton effects of p-CN-Au3 become active in the presence of chiral R-/S-THFA. The mirror-imaged CD curves centered at 288 nm (Fig. 3d) were triggered by R-/S-THFA, which were in accordance with the characteristic absorption band of co-assembly. The occurrence of Cotton effects might be attributed to the conformation chirality of p-CN-Au3 induced by R-/S-THFA.

The obtained DMF solution of p-CN-Au3/THFA were then immediately transferred onto quartz or silicon wafer substrates by using a micro pipette to consent their potential interfacial rearrangement on ambient evaporation. Under UV light excitation, solution of co-assembly was barely emissive, whereas drop-casting film emitted green luminescence (Fig. 3e). We supposed that the chiral co-assembly can endow the chromophore with CPL. Prior to the CPL properties, CD spectra of the drop-casting films in different molar ratios (Figs. 3f and S36) were conducted to confirm their successful chiral co-assemblies. Positive Cotton effects ranging from 280-450 nm were induced by R-THFA, while mirrored-imaged curves were presented in case of S-THFA. As shown in Fig. 3g and S37, the films showed strong mirror-imaged CPL, respectively. When THFA was at the critical value of 3 equiv., luminescence asymmetry factor (|glum | ) reached its maximum value of 0.018 at the CPL peak around 530 nm. Uncommonly, we found that |glum| were demonstrated larger than absorption asymmetry factor (|gabs | ). In addition, for the R-co-assembly, CD curves showed positive Cotton effect, while the corresponding CPL spectra give rise to negative signals. With rotation of the samples, almost no significant change in the CD and CPL spectra were observed, indicating that the mirrored CD and CPL signals ascribed to the chiral structure change of coassemblies (Figs. S38-41). CD and CPL represent the chiral structural information of the ground and excited states of chiroptical matter, respectively. Thus, such abnormal phenomenon may be attributed to the intrinsic properties of the AuI complex, for which the excited state generally undergo a large configurational deformation under UV excitation32,33, compared with the ground state.

Using the dimeric structure of p-CN-Au3 as a model system, we optimized the excited-state geometry and compared it with the ground-state configuration to elucidate the significant discrepancy between the gabs and glum values. Upon photoexcitation, notable structural changes were observed in the excited state (Figs. S42 and S43). Specifically, the torsion angles between the benzene ring and the plane defined by the three gold atoms underwent substantial alterations, with a maximum change of 13.69°. Consequently, the two molecules within the dimer no longer maintain mirror symmetry compared to the ground state (Figs. S27, S42 and S43). Moreover, while the intramolecular Au · ··Au distances remained essentially unchanged, the intermolecular Au · ··Au distances exhibited a pronounced reduction, decreasing from 3.235 Å to 3.221 Å and 2.880 Å. This contraction aligns with previously reported observations of shortened Au · ··Au distances in gold complexes32,33 under photoexcitation. Based on these findings, we propose that both the torsional distortions within the excited-state molecule and the changes in intermolecular Au···Au distances contribute to the significant discrepancy between the gabs and glum values.

Fluorescence microscope (FM) and SEM were employed to study the morphological structures of co-assemblies. Under FM observation (Fig. 3e), p-CN-Au3/THFA co-assembled into green-emitting fibrous nanostructures. As expected, homochiral helical microtwists were directly detected by SEM (Fig. 3h–m and S44–56), indicating the occurrence of supramolecular chirality induced by R-/S-THFA. In addition, the handedness preference of these helical microtwists followed the point chirality of THFA molecules, that is, S-THFA and R-THFA enantiomers could successfully contribute to M-helical and P-helical microtwists, respectively. It was further confirmed that their mirrored CD and CPL signals were stem from the opposite supramolecular helical chirality. Moreover, the molar ratio of R-/S-THFA were found to affect morphologies of the interfacial assemblies. SEM images of R-/S-assembly clearly reveal clear morphological transition by increasing the amount of chiral inducer from 1 to 30 equiv. As shown in Fig. 3h, k, when THFA was 1 equiv., thin microtwists consisting of multiple strands of nanowires were formed, since several single flexible fibers were observed on the substrate simultaneously. When THFA was up to 3 equiv., the twist-shaped superstructure is braided by a plenty of short fiber-like units, which are clockwise- or counter-clockwise-oriented to construct M- or P-helicity superstructure (Fig. 3i, l). When THFA contents were further increased to 10 equiv., as well as 30 equiv., the twisted superstructure gradually tended to be more loosely structures with larger size (Fig. S53–56, 3j, m). These results established that the nanoscale co-assemblies experienced morphological evolution and hierarchical self-assembly as the molar ratios of THFA rose.

Photophysical analysis were conducted to attain insights into assembly mechanism, including aggregation structure and driving forces. We measured the optical properties of p-CN-Au3/THFA (3 equiv.) co-assemblies. In comparison with the individual p-CN-Au3, p-CN-Au3/THFA co-assemblies afforded red-shifted emission band peaked at 522 nm, with shorter phosphorescent lifetime of around 4.10 μs (Fig. S57). And the PLQY of the co-assemblies exhibited more than a two-fold increase from 5.7% to 14.1%. As shown in Table S8, the radiative deactivation rate (kr) and non-radiative deactivation rate (knr) were estimated according to ΦFL = τ × kr and τ = 1/(kr + knr). The p-CN-Au3/THFA co-assemblies displayed significant increasing kr (3.45 × 104 s−1) and slightly increasing knr (2.09 × 105 s−1) compared to the individual p-CN-Au3. The enhanced red-shift phosphorescence and increasing kr indicated that stronger aurophilicity effect18,20,29,33,34,35,36,37 existed in the spiral co-assembly, which acted as the principal assembly driving forces to induce the metallic supramolecular polymerization and forming 1D aggregates.

Raman spectroscopy can serve as direct evidence for the presence of aurophilic interactions. Previous studies have reported that the stretching vibrations associated with Au · ··Au interactions typically occur within the range of 30 to 200 cm⁻¹38,39,40. To validate the occurrence of such interactions in p-CN-Au3/THFA assemblies, we measured the Raman spectra of p-CN-Au3 crystals and p-CN-Au3/THFA assemblies. As shown in Fig. S58, the p-CN-Au3 crystals exhibit a distinct peak at 65 cm⁻¹ and a shoulder peak at 91 cm⁻¹. These spectral features align well with the wavenumbers previously assigned to multiple Au · ··Au stretching vibrations and can be attributed to intramolecular (3.247-3.331 Å) and intermolecular (3.235 Å) Au · ··Au interactions within the crystal structure. For the p-CN-Au3/THFA assemblies, in addition to the peak at around 64 cm⁻¹, new Raman bands emerged at 108-114 cm⁻¹. Given that νAu···Au values are closely correlated with Au · ··Au interactions38, the appearance of these higher-wavenumber peaks suggests the presence of enhanced aurophilic interactions within the assemblies.

To further elucidate the Au · ··Au interactions in the p-CN-Au3 crystal and p-CN-Au3/S-THFA assembly, a systematic synchrotron-based Fourier transform extended X-ray absorption fine-structure (FT-XAFS) scattering analysis was performed41. In the Au L3-edge FT-EXAFS spectra (Fig. S59), the spectral regions corresponding to Au · ··Au interactions are shaded in pink. The peaks centered at 3.34 Å in p-CN-Au3 crystal and 3.27 Å in p-CN-Au3/S-THFA assembly, respectively, are attributed to Au · ··Au interactions, providing strong evidence for their presence. After coassembly, the observed spectral shift toward shorter distances indicates an enhancement of the Au · ··Au interactions in p-CN-Au3/S-THFA assembly. These results support the proposed assembly mechanism driven by aurophilic interactions.

Co-assembly mechanism of p-CN-Au3 with R-/S-THFA

In addition to aurophilic interactions, intermolecular Van der Waals interactions between THFA and p-CN-Au3 molecules might be existent to facilitate chiral transfer and helical co-assembly during the solution-interface-directed assembly process. To figure out this, 1H NMR titration studies of p-CN-Au3 with THFA of different equivalents were performed in DMF solution (Fig. 4a, b). The addition of THFA (0.5 equiv.) led to distinct upfield shifts for large portion of Ha, Hb and Hc of p-CN-Au3, accompanied by the fact that remaining fraction of H were not chemically shifted yet, indicating that strong non-covalent binding most likely occurred between p-CN-Au3 and THFA. When THFA reached to 3 equiv. of p-CN-Au3, all the 1H NMR signals of p-CN-Au3 upfield shifted, suggesting that the recognition interactions reached equilibrium. The phenomenon is consistent with that p-CN-Au3 possesses C3 symmetry, each of which could bind three THFA molecules via multiple interactions.

a Chemical structure of p-CN-Au3. b Partial 1H NMR spectra of p-CN-Au3/R-THFA in d6-DMSO with different R-THFA molar ratio. c FT-IR spectra of p-CN-Au3, R-THFA and p-CN-Au3/R-THFA (3 equiv.) assembly. d ESP mapping of p-CN-Au3 and R-THFA. e Proposed C-H ∙ ∙ ∙ O and C-H ∙ ∙ ∙ N interactions between p-CN-Au3 and R-THFA. f PXRD patterns of p-CN-Au3, R-THFA and p-CN-Au3/R-THFA (1 and 3 equiv.) assemblies. g Plausible co-assembly mechanism of p-CN-Au3/R-THFA from DMF solution.

To achieve further details to understand the binding modes between p-CN-Au3 and THFA, drop-casting samples were deposited to FT-IR tests. The FT-IR spectroscopy (Fig. 4c) of p-CN-Au3/THFA co-assemblies are the combination of THFA and p-CN-Au3, where almost all peaks only presented the original characteristic band of each individual component. Concretely, the FT-IR peaks of C-O-C (1052 cm−1) and N-H (3378 cm−1) groups of THFA are significantly moved to 1040 cm−1 and 3393 cm−1 in the co-assembly, respectively. Furthermore, the 1227, 1172 and 1133 cm−1 bands, which are ascribed to C–H on benzene rings in p-CN-Au3, shifted to 1238, 1181 and 1145 cm−1 in co-assemblies. However, the FT-IR signals peaked at 2225 cm−1 of -CN group did not change (Fig. S60), demonstrating that there was no direct interaction between -CN group and THFA. Subsequently, electrostatic potential (ESP) distribution analysis were employed to reveal their binding sites (Fig. 4d). THFA show negative charges on the O atom of furan group and N atom of amino group, respectively. For p-CN-Au3, its negative charges are mainly located at cyano groups, while C-H in benzene rings and methyl moieties display obvious positive areas, which can interact with THFA molecules by C-H · · · O and C-H · · · N interactions (Fig. 4e). Crucially, introducing chiral R- or S-THFA molecules enables stereoselective control of p-CN-Au₃ through directional C-H · · · O/N non-covalent interactions, and the chiral additives selectively stabilize one P- or M-conformational isomer (Fig. S31b), thereby templating the formation of enantiopure helical assemblies with handedness dictated by the chirality of R- or S-THFA (Fig. 4e). We found that the position of the -CN substituent group of the Au3 molecules played key roles in directing the interfacial assembled structures. Achiral slender tubular microstructure was formed for co-assembly of meta-substituted m-CN-Au3 with THFA (Fig. S61), which did not show any CD and CPL signals. The molecular structure of chiral inducer is another important factor to control the supramolecular morphology and chiroptical properties. Both (R)-(+)-tetrahydro-2-furoic acid and (S)-1-(2-pyridyl)ethylamine failed to yield homochiral assembly structures from p-CN-Au3 (Fig. S62). The above findings demonstrate the requisite and cooperative roles of chromophore and chiral inducer structures.

PXRD patterns would provide molecular packing information within the assemblies. In comparison with individual p-CN-Au3 crystal, p-CN-Au3/THFA co-assemblies showed new diffraction peaks at around 4.1° (Fig. 4f), indicating their distinct aggregate structures. The single-crystal XRD data of p-CN-Au3 revealed lamellar packing mode. However, PXRD pattern of co-assemblies (3 equiv.) displayed ordered diffraction peaks at 2θ values of 4.06°, 6.94°, 7.96°, 10.48° and 11.84° with a ratio of 1:√3:√4:√7:√9, supporting a hexagonal columnar packing mode along the direction perpendicular to the growth orientation of the 1D nanowires. According to Bragg’s equation, the calculated results from diffraction peaks gave d-spacing values of 2.17 nm, which was slightly larger than the size of Au3 molecule (around 1.88 nm), due the insertion of THFA molecules.

Based on above analysis results of morphology, interactions and packing mode from the asymmetric assembly of p-CN-Au3 induced by R-/S-THFA, we proposed a possible hierarchical assembly mechanism for the formation of helical structures (Fig. 4g). The p-CN-Au3 molecules in a supernatant solution firstly interact with THFA, followed by the occurrence of chirality transfer through synergistic C-H · · · O and C-H · · · N interactions, as supported by CD, 1H NMR and FT-IR spectroscopic data. After the obtained transparent solution are transferred to substrates, slow solvent evaporation then induce the co-assembly units to aggregate along 1D direction through aurophilic interactions and allow the formation of elementary twisted fibril-like structures. Finally, the chiral control between the fibers drives their intertwining and weaving, resulting in the formation of a helical rope with homochirality. In addition to serving as a chiral inducer, THFA is proposed to exert kinetic control over the assembly process due to its solubilizing effect on p-CN-Au3 molecules. Given the relatively low solubility of p-CN-Au3 and the enhancing effect of THFA on its solubility in DMF, increasing the molar amount of THFA effectively reduces both the precipitation and assembly rates of p-CN-Au3 during solvent evaporation. Consequently, the supersaturation threshold required for p-CN-Au3 precipitation is delayed, resulting in a significantly decreased nucleation rate. This slower kinetics of assembly allows more time for pre-assembled units (p-CN-Au3 and THFA molecules) to undergo preferential growth, ultimately leading to larger and stable morphologies.

Solvent-induced helicity inversion

Solvent-solute interactions can significantly affect the conformation, electronic structure, and secondary assembly structure of flexible molecules, potentially altering their self-assembly behavior and overall optical properties. With the above solvation effect of H2O on p-CN-Au3 molecules, we initiated exploring the feasibility of using H2O-chromophore interactions to regulate chiroptical properties of p-CN-Au3/THFA assemblies. We hypothesis that strong hydrogen-bonding solvents, H2O molecules, would disturb C-H · · · O or C-H · · · N interactions in the above co-assembly to induce conformational transformations of p-CN-Au3. As anticipated, with fW increasing, the CD spectra of p-CN-Au3/R-THFA in H2O-DMF mixed-solvent system showed gradually decreased positive Cotton effect signals, which finally turned into a negative Cotton effect when fW reached to 6/7 (Fig. 5a). The red-shift absorption and DLS results suggested that aggregate occurred under fW 6/7 condition (Fig. S63). The p-CN-Au3/S-THFA exhibited exactly identical behavior, showing negative-to-positive signal alteration in Cotton effects along with the increasing of fW. It is supposed that the introduction of H2O molecules could change the configuration of p-CN-Au3, causing them to exhibit controllable chiroptical properties.

a CD spectra of p-CN-Au3 and THFA in DMF/H2O mixture with different fw. b CPL spectra of p-CN-Au3/THFA assemblies from DMF/H2O mixture with different fw. c FT-IR spectra of p-CN-Au3, R-THFA and p-CN-Au3/R-THFA (3 equiv.) assembly. SEM images of (d) p-CN-Au3/R-THFA and (e) p-CN-Au3/S-THFA from DMF/H2O mixture (fw 4/7). f PXRD patterns of p-CN-Au3, R-THFA and p-CN-Au3/R-THFA assemblies from DMF/H2O mixture with different fw. g Plausible assembly mechanism of p-CN-Au3/R-THFA assembly from DMF/H2O mixture.

In comparison with DMF processed films, the R-assemblies prepared by drying drop-casting films of p-CN-Au3/R-THFA mixture from DMF/H2O solution also exhibited opposite Cotton effect with negative peaks at around 403 nm (Fig. S64). The mirrored CD signals are assigned to the absorption band of molecular aggregate induced by Au · ··Au interactions. Concurrently, in the presence of H2O molecules, S- and R-assemblies emitted inversed CPL properties. In fW 2/7 system, the R-assemblies showed a positive CPL with a glum of 0.011 (Fig. 5b). With increasing fW, glum increased to 0.018, demonstrating that aggregation could strengthen this chiral reversal process. With fW increasing, FT-IR peak of C-O-C stretching band in R-assemblies exhibited significant blue-shift from 1042 to 1054 cm−1 (Fig. 5c), indicating weakening of the C-H · · · O interaction. H2O can interfere with the assembly process, leading to changes in the chirality of the assembled structure. SEM micrographs (Figs. 5d,e and S65) of R-/S-assemblies revealed that H2O induced 2D-nanoflower structure composed of nanosheets rather than 1D fibers. We found that the PLQY of R-assembly (fW 4/7) is further increased to 19.5% and knr is reduced to 1.75×105, indicating a more compact stacks (Fig. S66 and Table S9). PXRD patterns showed diffraction peaks at 2θ values of 7.03 and 13.89°, which are close to the (01-1) and (02-2) diffractions of simulated XRD patterns from single-crystal data of p-CN-Au3, supporting a multi-lamellar packing mode in R-/S-assemblies (Fig. 5f).

Based on this, we proposed a possible water-mediated assembly mechanism, where H2O molecules play a crucial role in the chirality of assemblies. This phenomenon might originate from the dynamic conformational equilibrium of p-CN-Au₃. As previously mentioned, p-CN-Au3 is an achiral molecule. In solution, the benzene rings are capable of free rotation, and due to its propeller-like conformation, the p-CN-Au3 can adopt both M- and P-conformers (Fig. S31b). Upon introducing enantiopure R- or S-THFA, directional C-H · · · O/N interactions selectively stabilize one homochiral conformer, inducing homochirality evidenced by intense CD signals (Fig. 3d). Crucially, incremental water addition progressively might disrupt such THFA-cluster binding through competitive hydrogen-bonding, destabilizing the initially locked conformer. In this system, further addition of water molecules led to gradual decrease in the CD signals (Fig. 5a), which eventually inverted with increasing water content. As water content increases, the system undergoes reequilibration toward the mirror-image conformer, evidenced by CD signal attenuation. Chirality inversion indicates that water molecules induce a conformational transition of p-CN-Au3 from one enantiomeric conformation to its mirror-image counterpart. By weakening the intermolecular C-H · · · O interactions, water molecules induce a helical chirality in the assembly that is opposite to the intrinsic chirality of the THFA. Mediated by water molecules (Fig. 5g), p-CN-Au3/R-THFA form a 1D M-helical molecular chains driven by aurophilic interactions, which then undergo layer-by-layer stacking to form flexible ribbon-like nanosheets, further assembling into nanoflower structures.

Discussion

In summary, we proposed and employed an aurophilicity-assisted orthogonal assembly strategy to fabricate homochiral architectures based on an achiral p-CN-Au3 molecule. Benefiting from its C3-symmetrical structure and potential Au · ··Au interactions, p-CN-Au3 can spontaneously assemble into random P- and M-helical nanowire through symmetry breaking. The introduction of R/S-THFA have successfully induced preferred homochiral twists of p-CN-Au3 assembly. Two types of independent interactions, including aurophilicity and C-H · · · X interactions together lead to orthogonal assembly. In this case, intermolecular C-H · · · O and C-H · · · N interactions assure strong binding effect and chirality transfer process between R/S-THFA and p-CN-Au3 in DMF solution. While, aurophilicity driven p-CN-Au3/THFA units to spiral align along 1D direction forming nanoscale rod-like structures, which further assembled into hierarchical helical twists. We found that the addition of H2O could mediate the co-assembly process, which eventually result in chirality inversion and morphological transformation, accompanied by switching CPL signs. These results elaborate the chirality transfer and evolution in the hierarchical assemblies of achiral Au(I) cluster and allow the precise control of chirality through the aurophilicity-assisted orthogonal assembly methodology.

Methods

Synthesis of p-CN-Au3

Complex p-AuCSA (15.00 mg, 0.02 mmol), (THT)AuCl (6.40 mg, 0.02 mmol) and 2.0 µL of NEt3 (0.44 mmol) were added in 3 mL CH2Cl2 and stirred for 2 h at room temperature in the dark. Finally, a white turbid solution was obtained. The solvent is removed by filtration, and the precipitate was washed three times with a small amount of DCM to obtain a white product p-CN-Au3 (5.20 mg, 0.0048 mmol). Yield: 24% (based on Au). 1H NMR (600 MHz, d6-DMSO) 7.80 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 6H), 7.43 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 6H), 3.90 (s, 9H). Elemental analysis calcd (%): C 30.35; H 1.98; N 7.87; found: C 29.01; H 1.85; N 7.13. m/z: [M + Cl-] C27H21Au3N6O3Cl-. Calcd 1103.0360, found 1103.0274.

Synthesis of m-CN-Au3

Complex m-AuCSA (15.00 mg, 0.02 mmol), (THT)AuCl (6.40 mg, 0.02 mmol) and 2.0 µL of NEt3 (0.44 mmol) were added in 3 mL CH2Cl2 and stirred for 2 h at room temperature in the dark. Finally, it becomes a white turbid liquid. The solvent is removed by filtration, and the precipitate was washed three times with a small amount of DCM to obtain a white solid of m-CN-Au3. Yield: 26% (based on Au). 1H NMR (600 MHz, d6-DMSO) δ 7.68 (s, 3H), 7.61 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 3H), 3.89 (s, 9H). Elemental analysis calcd: C 30.35; H 1.98; N 7.87; found: C 29.62; H 1.96; N 7.23. m/z: [M + Cl-] C27H21Au3N6O3Cl-. Calcd 1103.0360, found 1103.0330.

Preparation of p-CN-Au3 crystals

Dissolve solid powder of p-CN-Au3 in DCM under ultrasound conditions, and then seal the vial and make two small holes. After evaporating in a refrigerator at 4 °C for 2 days, the crystals of p-CN-Au3 were obtained.

Preparation of p-CN-Au3 and m-CN-Au3 self-assembly

1.00 mg p-CN-Au3 were added into 1.0 mL DMF (or CH2Cl2), then the mixture were heated until the solid were completely dissolved. After naturally cooling to room temperature, white flocculent precipitate was obtained to be the self-assembly of p-CN-Au3. The m-CN-Au3 self-assembly was obtained via the similar method.

Co-assembly protocol

p-CN-Au3 (4.00 mg) was dissolved in DMF (4.0 mL) under heating to prepare a 1.0 mg/mL solution. Two R-/S-tetrahydrofurfurylamine (R-/S-THFA) stock solutions (a and b) were prepared by dissolving 3 μL of R-/S-THFA in DMF (197 μL for solution a, 37 μL for solution b). Solution of p-CN-Au3/THFA mixture with varied equivalents (1-30 eq) were obtained by adding specific volumes of R-/S-THFA solutions (2, 4, 6, 14 μL of a; 4, 12 μL of b) to 300 μL of the p-CN-Au3 solution, followed by sonication for 20 min.

50 μL of the above mixture was drop-cast onto a 2 cm × 2 cm quartz slide and dried for 6 h in a fume hood, then the obtained film were subject to chiroptical analysis. 2 μL of the same mixture was drop-cast onto a 3 mm × 3 mm silicon wafer and dried under identical conditions, then the obtained films were subject to SEM analysis.

Single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis

Crystallographic data collection and structural refinement. Single crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis measurements of p-CN-Au3 were performed at 200 K on a Rigaku XtaLAB Pro diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å). Data collection and reduction were performed using the program CrysAlisPro[1],[2]. The structure was solved with direct methods (SHELXS)[3] and refined by full-matrix least squares on F2 using OLEX2[4], which utilizes the SHELXL-2015 module[5]. All atoms were refined anisotropically, and hydrogen atoms were placed in their calculated positions with idealized geometries and assigned fixed isotropic displacement parameters. Detailed information about the X-ray crystallography data, intensity collection procedure, and refinement results are summarized in Tables S1.

Photophysical measurements

UV-Vis absorption spectra were recorded using a Hitachi UH4150. Steady-state photoluminescence (PL) spectra were obtained via a HORIBA FluoroLog-3 fluorescence spectrometer. The luminescence lifetime were measured on a HORIBA FluoroLog-3 fluorescence spectrometer operating in time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) mode. The photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQY, ΦFL) were measured using an integrating sphere on a HORIBA Scientific FluoroLog-3 spectrofluorometer. Luminescence microscopy images were recorded on an Olympus BX53 microscope. Solvent used for photophysical measurements is of analytical purity.

CD spectra

CD spectra were recorded using a JASCO J-1500 spectrophotometers. Solid samples were prepared on quartz slides and measured in conventional transmission mode at various orientations (0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°) by rotating the quartz slide.

CPL spectra

CPL spectra were obtained using a JASCO CPL-300 spectrophotometer. To minimize interference from linear birefringence (LB) effects and potential artifacts arising from macroscopic anisotropy, the sample was flipped and its orientation was varied (0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°) along the direction of incident light propagation.

Quantum chemical calculations

The energies of frontier molecular orbitals were calculated based on the structures of the crystal dimers, by performing a single point energy calculation at PBE0/def2-SVP level[11, 12] in vacuum. Time dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) calculation was further carried out at TD-PBE0/def2-SVP level based on the structures of the crystal dimers.

Data availability

All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information file. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2361828 (p-CN-Au3). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. Source Data are provided with this manuscript. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Lu, M. et al. Adaptive helical chirality in supramolecular microcrystals for circularly polarized lasing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202408619 (2024).

Kishimura, A., Yamashita, T., Yamaguchi, K. & Aida, T. Rewritable phosphorescent paper by the control of competing kinetic and thermodynamic self-assembling events. Nat. Mater. 4, 546–549 (2005).

Du, C., Li, Z., Zhu, X., Ouyang, G. & Liu, M. Hierarchically self-assembled homochiral helical microtoroids. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 1294–1302 (2022).

Kang, S. G. et al. Circularly polarized luminescence active supramolecular nanotubes based on ptii complexes that undergo dynamic morphological transformation and helicity inversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202207310 (2022).

Wang, Y., Niu, D., Ouyang, G. & Liu, M. Double helical π-aggregate nanoarchitectonics for amplified circularly polarized luminescence. Nat. Commun. 13, 1710 (2022).

Wang, C., Xu, L., Zhou, L., Liu, N. & Wu, Z.-Q. Asymmetric living supramolecular polymerization: Precise fabrication of one-handed helical supramolecular polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202207028 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Three-level chirality transfer and amplification in liquid crystal supramolecular assembly for achieving full-color and white circularly polarized luminescence. Adv. Mater. 37, 2412805 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Full-color-tunable chiral aggregation-induced emission fluorophores with tailored propeller chirality and their circularly polarized luminescence. Aggregate 5, e613 (2024).

Fu, K., Zhao, Y. & Liu, G. Pathway-directed recyclable chirality inversion of coordinated supramolecular polymers. Nat. Commun. 15, 9571 (2024).

Liu, G., Humphrey, M. G., Zhang, C. & Zhao, Y. Self-assembled stereomutation with supramolecular chirality inversion. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 4443–4487 (2023).

Kim, K. Y. et al. Co-assembled supramolecular nanostructure of platinum(II) complex through helical ribbon to helical tubes with helical inversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 11709–11714 (2019).

Hu, X.-Y., Xiao, T., Lin, C., Huang, F. & Wang, L. Dynamic supramolecular complexes constructed by orthogonal self-assembly. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 2041–2051 (2014).

Feng, Q. et al. Highly efficient self-assembly of heterometallic [2]catenanes and cyclic bis[2]catenanes via orthogonal metal-coordination interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202407923 (2024).

Zhou, Z., Yan, X., Cook, T. R., Saha, M. L. & Stang, P. J. Engineering functionalization in a supramolecular polymer: Hierarchical self-organization of triply orthogonal non-covalent interactions on a supramolecular coordination complex platform. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 806–809 (2016).

Xia, Z., Song, Y.-F. & Shi, S. Interfacial preparation of polyoxometalate-based hybrid supramolecular polymers by orthogonal self-assembly. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202312187 (2024).

Jia, P.-P. et al. Orthogonal self-assembly of a two-step fluorescence-resonance energy transfer system with improved photosensitization efficiency and photooxidation activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 399–408 (2021).

Seifert, T. P., Naina, V. R., Feuerstein, T. J., Knöfel, N. D. & Roesky, P. W. Molecular gold strings: Aurophilicity, luminescence and structure–property correlations. Nanoscale 12, 20065–20088 (2020).

Jin, M., Seki, T. & Ito, H. Mechano-responsive luminescence via crystal-to-crystal phase transitions between chiral and non-chiral space groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 7452–7455 (2017).

Zhao, X. et al. Metallophilicity-induced clusterization: Single-component white-light clusteroluminescence with stimulus response. CCS Chem. 4, 2570–2580 (2022).

Mirzadeh, N., Privér, S. H., Blake, A. J., Schmidbaur, H. & Bhargava, S. K. Innovative molecular design strategies in materials science following the aurophilicity concept. Chem. Rev. 120, 7551–7591 (2020).

Schmidbaur, H. & Schier, A. Aurophilic interactions as a subject of current research: An up-date. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 370–412 (2012).

Liu, Y.-J., Liu, Y. & Zang, S.-Q. Solvation-mediated self-assembly from crystals to helices of protic acyclic carbene aui-enantiomers with chirality amplification. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202311572 (2023).

Seki, T., Takamatsu, Y. & Ito, H. A screening approach for the discovery of mechanochromic gold(i) isocyanide complexes with crystal-to-crystal phase transitions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 6252–6260 (2016).

Ni, W.-X. et al. Approaching white-light emission from a phosphorescent trinuclear gold(i) cluster by modulating its aggregation behavior. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 13472–13476 (2013).

Rabaâ, H., Omary, M. A., Taubert, S. & Sundholm, D. Insights into molecular structures and optical properties of stacked [au3(rn═cr′)3]n complexes. Inorg. Chem. 57, 718–730 (2018).

Enomoto, M., Kishimura, A. & Aida, T. Coordination metallacycles of an achiral dendron self-assemble via metal−metal interaction to form luminescent superhelical fibers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 5608–5609 (2001).

Yang, H. et al. Achiral Au(i) cyclic trinuclear complexes with high-efficiency circularly polarized Near-Infrared tadf. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202310495 (2023).

Bartolomé, C. et al. Structural switching in luminescent polynuclear gold imidoyl complexes by intramolecular hydrogen bonding. Organometallics 25, 2700–2703 (2006).

Fujisawa, K. et al. Tuning the photoluminescence of condensed-phase cyclic trinuclear Au(i) complexes through control of their aggregated structures by external stimuli. Sci. Rep. 5, 7934 (2015).

Maity, A. et al. Counteranion driven homochiral assembly of a cationic c3-symmetric gelator through ion-pair assisted hydrogen bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 11113–11116 (2016).

Shen, Z., Jiang, Y., Wang, T. & Liu, M. Symmetry breaking in the supramolecular gels of an achiral gelator exclusively driven by π–π stacking. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 16109–16115 (2015).

Schmidbaur, H. & Raubenheimer, H. G. Excimer and exciplex formation in gold(i) complexes preconditioned by aurophilic interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 14748–14771 (2020).

Seki, T., Sakurada, K., Muromoto, M. & Ito, H. Photoinduced single-crystal-to-single-crystal phase transition and photosalient effect of a gold(i) isocyanide complex with shortening of intermolecular aurophilic bonds. Chem. Sci. 6, 1491–1497 (2015).

Seki, T. et al. Interconvertible multiple photoluminescence color of a gold(i) isocyanide complex in the solid state: Solvent-induced blue-shifted and mechano-responsive red-shifted photoluminescence. Chem. Sci. 6, 2187–2195 (2015).

Jin, M., Sumitani, T., Sato, H., Seki, T. & Ito, H. Mechanical-stimulation-triggered and solvent-vapor-induced reverse single-crystal-to-single-crystal phase transitions with alterations of the luminescence color. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 2875–2879 (2018).

Ito, H. et al. Mechanical stimulation and solid seeding trigger single-crystal-to-single-crystal molecular domino transformations. Nat. Commun. 4, 2009 (2013).

Yagai, S. et al. Mechanochromic luminescence based on crystal-to-crystal transformation mediated by a transient amorphous state. Chem. Mater. 28, 234–241 (2016).

O’Connor, A. E. et al. Aurophilicity under pressure: A combined crystallographic and in situ spectroscopic study. Chem. Commun. 52, 6769–6772 (2016).

Kumar, K., Stefanczyk, O., Chorazy, S., Nakabayashi, K. & Ohkoshi, S. -i Ratiometric and colorimetric optical thermometers using emissive dimeric and trimeric {[Au(SCN)2]−}n moieties generated in d–f heterometallic assemblies. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202201265 (2022).

Yang, J.-G. et al. Controlling metallophilic interactions in chiral gold(i) double salts towards excitation wavelength-tunable circularly polarized luminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 6915–6922 (2020).

Wu, Z. et al. Aurophilic interactions in the self-assembly of gold nanoclusters into nanoribbons with enhanced luminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 8139–8144 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 92461304 and 92356304 to S.-Q.Z., and No. 22105177 to Y.-J.L.), the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2021YFA1200301 to S.-Q.Z.), the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (No. 252300421174 to Y.-J.L.), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2021TQ0294 to Y.-J.L.), and the Zhongyuan Thousand Talents (Zhongyuan Scholars) Program of Henan Province (No. 234000510007 to S.-Q.Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.-J. Liu and S.-Q. Zang conceived and designed the experiments. Y.-J. Liu, W.-Q. Yu, Y. Liu and X.-W. Qi conducted the synthesis and characterization. Y.-J. Liu and Y. Liu completed crystallographic data collection and refinement of the structure. Y.-J. Liu, W.-Q. Yu and Y. Liu drew pictures in the manuscript. Y.-J. Liu and W.-Q. Yu analyzed the experimental results. Y.-J. Liu wrote the manuscript. S.-Q. Zang helped to revise the writings.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jatish Kumar, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, YJ., Yu, WQ., Liu, Y. et al. Solvent-mediated chirality inversion in orthogonal hierarchical assembly of achiral carbene-anchored gold cluster. Nat Commun 16, 10586 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65637-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65637-8