Abstract

Visualization in complex, extreme environments necessitates that the imaging material/system to deliver more comprehensive information and endures external mechanical deformation. Endowing polarization, for example, helicity, in adaptable optical materials—to construct circular-polarization-enabled imaging—offers the chance to address the issue. However, retaining considerable luminescence asymmetry during processing while behaving like an elastic rubber remains challenging, resulting from unstable circularly polarized luminescence when deforming existing polarization materials. Here, we propose a covalent cross-linking strategy, combining a sustainable light generator with an optical helicity modulator, to prepare chiroptical network structures exhibiting superior mechanical-chiroptical coupling. The obtained structures provide satisfying circularly polarized luminescence with an asymmetry factor up to 1.31 alongside exceptional tensile strain tolerance, and more importantly, the asymmetry maintains a magnitude of 10−1 even with 80% deformation. We further advance our materials into wearable polarization optical sensors, practicing our developed circular polarization differential imaging in a fire scenario, showing an advancement in imaging resolution compared to other technologies such as thermal, intensity and fluorescence imaging. This covalent-bonding chiroptical network structures enable deformable optical helicity, paving a way for achieving portable imaging identification under extreme conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Imaging-in-optic, one indispensable technology for humanity, unveils the material information of observable objects1,2,3. Background light influences the resolution and signal-to-noise ratio, causing most traditional optical imaging (such as intensity imaging, spectral imaging, infrared radiation imaging, etc.) to fail in some extreme environment4,5. Polarization, beyond the intensity and wavelength of light—offers a source of additional optic information—to be efficiently captured in complex spaces6,7,8. Within that, circular polarization light allows the optimal polarization state retention during transmission, showing the most promise for imaging technology9,10,11,12,13. More importantly, when paring the mechanical deformation capability with circular polarization rotation materials, it provides the chance to be a wearable imaging system towards adapting human behavior; yet, it has not been implemented.

Combining macro-helical domains (chiral liquid crystals, representatively14) and illuminant units—to form a circularly polarized emitting composite—enables large optical asymmetry (luminescence asymmetry factor, glum, over 10−1 in general)15,16,17, required for circular polarization-based imaging2,18. However, most formed composites exist as physical-doping hybrids, suffering from phase separation and unsatisfying stability even with the arcane surface processing of structures towards practice19,20,21,22; while the others are generated in the form of physical-stacking bilayers23,24,25, inevitably undergo interfacial delamination during stretching and deformation. These intrinsic instabilities severely restrict their viability in adaptable imaging systems that require simultaneous retention of high glum and stretchability. Thus, developing mechanically robust circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) materials and maintaining significant circular polarization optics in drastic working remain challenging.

Here we report a chiroptical network structure with mechanical-chiroptical coupling, allowing for strong CPL in deformation. The robust composite is achieved by a designed covalent cross-linking strategy, connecting a soft spiral structure (namely optical helicity modulator, OHM) and the inorganic phosphor embedded in polymer as a sustainable light generator (SLG). The as-prepared network-structure composites obtain a large glum value up to 1.31 and a strain tolerance of 192%. Crucially, the covalent network resists interfacial failure, performing satisfied circular polarization effect even under the deformation of 80%. With obtained deformable optical helicity, wearable polarization optical sensors are built and performed with an extended imaging technology—circular polarization differential imaging (CPDI), that is, image information is presented by subtracting two images with different intensities acquired by passing sensor-generated circularly polarized light through the left- and right-handed circular polarizing filters (L- and R-CPFs). We then successfully identify the person who wears the sensor emitting circularly polarized light in a fire scenario using CPDI. The chiroptical network structures and adaptable imaging technology we developed are expected to work under more extreme conditions.

Results and discussion

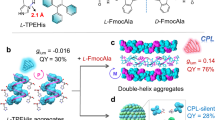

Deformation of covalent-bonding chiroptical network structure

To enable deformable CPL, we proposed to composite chiral macro-helical materials and phosphors (allowed to yield large circular polarization) via the covalent bonding, which offers the largest binding energy for strong interfacial connection26,27,28. A covalent-bonding chiroptical network (CBCN) structure was designed—functionalized by two components, OHM and SLG (Fig. 1a)—whose interface was formed via covalent crosslinking to generate a network structure (Fig. 1b). Preserved polarization under continuous deformation was expected on account of the designed network structure’s high elasticity. To construct CBCN, we first built the OHM layer using a cholesteric liquid crystal elastomer that synthesized from crosslinking assembly of liquid crystal monomers, flexible spacer, and crosslinker (Fig. 1c, see details in Methods and Supplementary Tables 1, 2). Inorganic phosphors with high luminescence efficiency—have higher physical and chemical stability compared to others (organic dyes, inorganic quantum dots, etc.)29—were chosen, embedded into polymer matrix for forming SLG. When we poured the SLG precursors on the formed OHM surface, olefinic bonds of the used poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA, in the SLG) would co-polymerize with the unreacted ones of OHM, forming a whole network structure, i.e. CBCN. We also tuned the CBCN emission (Fig. 1d) for further utilization.

a Concept and design of the CBCN composed of OHM and SLG. b Schematic image of the covalent bonding interface, generating a network topological structure. c Fabrication process of the CBCN, including two stages: I formation of OHM; II polymerization of the luminescent precursor with the surface of OHM. d Photographs showcasing the CBCN with different color emissions. Scale bar, 1 cm. e 3D-reconstruction images of the CBCN, viewed from the front (the left) and side (the right) directions. Scale bars, 150 μm. f Cross-sectional SEM image of the CBCN, showing a tightly bound interface. Scale bar, 10 μm. g FTIR spectra of the CBCN, demonstrating the formation of covalent bonds through the olefinic bonds disappearance of OHM and luminescent precursor. h Mechanical characterization of the CBCN-based film: the upper photographs illustrates its flexibility, while the lower graph depictes the tensile test result. Scale bar, 1 cm. i Simulated strain distribution within the CBCN model (top) and a physical-stacking bilayer model (bottom) conducted via finite element analysis. The models consist of a OHM layer and a SLG layer. Applying 50% strain to the OHM layer, the SLG will generate 50% strain in the CBCN model while failing to achieve in the physically stacked bilayer model, demonstrating the mechanical compliance and robust interface of CBCN.

From the 3D-reconstruction and cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images, a well-defined clear heterogeneous interface was observed in the CBCN (Fig. 1e, f), preventing delamination under mechanical strain (Supplementary Fig. 1). We employed Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to examine the CBCN’s interface and found no olefinic bond signal (Fig. 1g), evidencing the covalent bond formation between the OHM and SLG. The CBCN exhibits exceptional low-stress deformability (top panel in Fig. 1h), for example, a 192% stretch enabled under 0.64 MPa (bottom curve in Fig. 1h), with satisfying wearability. Finite element analysis simulation was further applied and demonstrated that the robust interfacial bonding allowed for efficient redistribution of mechanical strain across the OHM and SLG layers, avoiding the undesirable interface separation (Fig. 1i and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Polarization optics of deformable CBCN

With achieved well-deformation of CBCN, we then examined its circular polarization characteristics. As quasi-1D photonic crystals, OHM exhibits intrinsic photonic bandgap effect that selectively reflects circularly polarized light with the same handedness while transmitting the opposite one, enabling effective glum enhancement. Consequently, in the CBCN’s bilayer structure, CPL was anticipated to generate (Fig. 2a)—by passing the unpolarized light excited from the SLG to OHM—owing to the photonic bandgap-mediated selective transmission. We initially used right-handed OHM and engineered its photonic bandgap to optimally overlap with the emission peak of SLG (Supplementary Figs. 3, 4), attaining full-color left-handed circularly polarized light (Fig. 2b) with encouraging glum values as high as 1.31 that is over 260% of the required value for visualization applications (Fig. 2c–e)30. We further measured the transmittance of the light passing through a quarter-wave plate followed by a rotating analyzer (Supplementary Fig. 5), confirming a superb circular polarization characteristic of the luminescence generated from CBCN. Our prepared CBCN showed an advancement compared to the reported CPL-active materials in both glum value and stretchability16,20,25,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42, offering potential for further practice.

a Schematic illustration for the conversion of sustainable light generated from SLG into spirally polarized light via the OHM. b Normalized circularly polarized luminescence spectra. c–e Variation in glum values as a function of wavelength of CBCN structures corresponding to (b). f–h Dependence of glum values on applied strain. i Schematic representation of the helical structure during deformation. j Atomic force microscope height images of the OHM layer in the CBCN structure with different stretch ratios (ε = 0% and 50%, respectively). Scale bars, 10 μm. k Two-dimensional wide-angle X-ray scattering patterns of the CBCN structure subjected to different stretching conditions. The color scales represent “Intensity (arb. units)”. l Types of deformation accommodated by the CBCN structure. m Brightness difference of the obtained circularly polarized light through L- and R-CPFs under different deformation corresponding to (l). Scale bars, 1 cm.

Based on the obtained strong CPL, all CBCN structures showed a luminescent intensity difference (Supplementary Fig. 6) when the generated circularly polarized light passed through L- and R-CPFs, respectively. Such feature is considered to be ideal prerequisite to perform the imaging recognition with circular polarization.

To evaluate the circular polarization properties of prepared CBCN structures under tensile deformation—towards further adaptable imaging practice—we measured CPL spectra under various stretches. We found the glum value remained above 10−1 at a deformation rate of up to 60–80% (Fig. 2f–h and Supplementary Fig. 7), ensuring sufficient brightness contrast for further applications. The CPL degradation can be attributed to the spectral mismatch between the OHM’s photonic bandgap and SLG’s emission peak induced by stretching (Fig. 2i and Supplementary Fig. 8). On the other hand, the well-defined initial periodic structures were also gradually disrupted with the deformation increasing (Fig. 2j and Supplementary Fig. 9). The transition from Debye ring to arcs evidenced that the liquid crystal director (the long axis of the molecule) predominantly aligned along the mechanical stretching direction (Fig. 2k and Supplementary Figs. 10, 11). It is worthy to note that the skin deformation rates occurring during maximal motion of human joints (such as elbows and knees) does not exceed 50–70% for adult female and male (Supplementary Fig. 12). Therefore, the polarization retention of CBCN satisfies the wearable requirements. Additionally, we successfully captured high-quality luminance difference of the CBCN under various deformation conditions using a luminance meter (Fig. 2l, m and Supplementary Fig. 13).

Processability of CBCN

To apply our CBCN in practical wearable applications, we further developed processing technology, shaping CBCN into diversity including patterned two-dimensional films and woven one-dimensional fibers (Fig. 3a). Owing to the designed covalent bonding in CBCN, strongly crosslinking enabled to print varies of labels (with the glum value over 1) using direct ink writing (Fig. 3b, c, Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary video 1). Meanwhile, we used core/cladding method to generate core-shell fibers interfaced by covalent binding (Supplementary Fig. 15 and Fig. 3d–g), with considerable circularly polarized emission as well (Supplementary Figs. 16, 17). The maintaining high optical helicity in processing products provides the chance to realize wearable sensors using a designed CPDI technology. To implement this imaging technology, we developed a binocular camera equipped with L- and R-CPFs (Fig. 3h and Supplementary Fig. 18), and thus allowing to capture two images with different light intensities of CBCN, which can be further used to create a differential imaging subject by subtracting the two images. In contrast, the unpolarized light emitted from ordinary luminous objects maintained consistent transmittance through the L- and R-CPFs (Supplementary Fig. 19), resulting in two images with equal light intensities, which failed to produce differential imaging. And we then experimentally validated this imaging technology (Fig. 3i), demonstrating that CPDI has significant potential for improving imaging contrast and accuracy. We further integrated the fabricated polarization optical sensors into wearable forms, presenting a series of CPDI signals (Fig. 3j and Supplementary Figs. 20, 21). Considering the water stability of sensors during wearable operation, we placed the sample in the artifical sweat to assess its operational durability and found that the CBCN remained excellent CPL performance after more than 200 h immersion (Supplementary Fig. 22).

a Schematic representation of CBCN in forms of two-dimensional hetero-film and one-dimensional hetero-fiber. b, c Direct ink writing (b) for making polarization optical sensors (c). Scale bars in (c), 1 cm. d, e Preparation of core-shell polarization optical fibers. Scale bar in (e) 1 cm. f, g Cross-sectional SEM image and schematic of the core-shell fibers, showing that the cholesteric spiral layer is wrapped around the luminescent core to produce spiral polarization light. Scale bar in (f) 500 μm. h CPDI mechanism. i CPDI evaluation with the photoluminescence and circularly polarized luminescence materials. Scale bars, 5 mm. j The imaging of wearable polarization optical sensors using CPDI. Scale bars, 1 cm.

CPDI of the CBCN-based polarization optical sensor in fire scenario

We took a view, going one step further, to practice our CPDI in the extreme environment. Nearly 20000 civilian deaths and over 55000 injures occurred in fires (2022-year data from CTIF World Fire Statistics Center)43, motivating us to explore high-precision imaging technologies to monitor humans in fires for efficient rescue. Our developed CPDI offers the chance to significantly suppress the background firelight for enhanced detection and identification of targets. To evaluate it, we first monitored a CBCN-made-tag surrounded with high temperature and intense firelight from candle flame (Fig. 4a) using different imaging methods such as thermal imaging, intensity imaging, and CPDI. The results demonstrated that our CPDI accurately identified the circularly polarized signal emitted from the tag and imaged, outperforming the thermal and intensity imaging in recognition accuracy (Fig. 4b–d). It highlighted CPDI’s potential for use in rescue operations where the environment is complex and cluttered.

a Image illustration for identifying the target from fire light. Three recognition modalities are shown including infrared thermal imager, luminance meter, and polarization binocular camera. b–d Evaluation of recognition capabilities: thermal imaging (b), intensity imaging (c), and CPDI (d), using candle flames to verify the accurate capture of the CBCN-made-target. Scale bars, 1 cm. e–g CPL spectra of blue-, green-, and red-emitting CBCN at 2 °C intervals within the temperature range from 20 to 100 °C, respectively. h Schematic application for CPDI in fire scenario. i Photograph of the integrated smart device for CPDI, consisting of a binocular camera carried by an intelligent robotic platform (serving as the signal recognition system) and a terminal (serving as the information display and processing). The inset shows the robotic platform in operation. j–m CPDI monitoring of a person with varying movements in simulated fire scenarios, showing the precise identification capabilities of CPDI even with deformation of the polarization optical sensors. Scale bars, 1 cm.

We then performed in-situ CPL spectra of the CBCN within the temperature range from 25 to 100 °C to verify CPDI’s feasibility (Fig. 4e–g and Supplementary Figs. 23, 24). Strong circular polarization signals remained even at elevated temperatures, including but not limited to 100 °C, demonstrating their tolerance for high temperature environments.

Subsequently, we set up a fire scenario to test our CBCN with CPDI (Fig. 4h). A signal recognition system was assembled, comprising our designed binocular camera and an intelligent robotic platform, to locate the character carrying circular-polarized signals that were further transmitted to the data terminal for displaying and processing (Fig. 4i). The intelligent recognition system has a sensitive vision and can automatically capture the light signal in the fire, presenting two images simultaneously (Supplementary Video 2). The person, wearing the CBCN-made knee straps, was able to be identified in the fire environment without any interference (Supplementary Fig. 25 and Fig. 4j, k) owing to emitted circularly polarized signals. More importantly, the signals can still be received with large behavioral changes (Supplementary Fig. 26 and Fig. 4l, m), proving that the wearable sensors are adapted to human movements.

In conclusion, we fabricated a flexible network structure via covalent cross-linking strategy—composed of an optical helicity modulator and a sustainable light generator—to achieve robust circularly polarized luminescence under deformation. In light of these characteristics, we further developed the CBCN structure into wearable optical polarization sensors and facilitated the deployment of designed CPDI in fire scenario, validating our technology has higher recognition accuracy than traditional optical imaging technologies, for example, thermal and intensity imagery. This will stimulate fresh explorations of polarization materials in the field of optical imaging.

Methods

Materials

The 1,4-bis-[4-(3-acryloyloxypropyloxy)benzoyloxy]-2-methylbenzene (RM257, monomer, >98.0%) was purchased from Shijiazhuang Yesheng Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. (3R,3aS,6aS)-hexahydrofuro[3,2-b] furan-3,6-diyl bis(4-(4-((4-(acryloyloxy)butoxy)carbonyloxy) benzoyloxy) benzoate) (LC756, monomer, 95%) was purchased from Nanjing Xinyao Technology Co., Ltd. The Pentaerythritol tetrakis(3-mercaptopropionate) (PETMP, >95.0%) and 2,2’-(Ethylenedioxy)diethanethiol) (EDDET, 95.0%), dipropylamine (DPA, 99.0%) and Irgacure 651 were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA, Mw = 400 Da) were purchased from Macklin. The fluoroelastomer poly (vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropene) (PVDF-HFP, Daiel G801) was provided by Daikin. The 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyl acrylate (TEAc) was purchased from Shang Fluro Co. Ltd. The photo-initiators, diphenyl-(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)-phosphine oxide (TPO), was purchased from Adamas-beta. The fume silica (SiO2, AEROSIL 200) was purchased from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. The inorganic phosphors, including Y2O2S:Eu,Mg,Ti (red emission), SrAl2O4:Eu,Dy (green emission) and Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu (blue emission), were purchased from Shenzhen Looking Long Technology Co., Ltd. All reagents used in the experiments were used directly without any further purification.

Synthesis of the OHM

1.1320 g RM257 and a series of LC756 with weight ratios of 5.0 wt%, 6.3 wt%, and 7.0 wt% were mixed with toluene and heated at 80 °C for 5 min and cooled to room temperature. Then, 0.0658 g PETMP, 0.1392 g EDDET, 0.0080 g Irgacure 651 and 0.2971 g DPA (was diluted to 1:100 ratio with toluene) were added into the mixed solution and stirred for 5 min. The obtained reactive mixture was vacuumed for 1 min and transferred to a glass substrate for 24 h. The resultant cholesteric prepolymer was photocured with UV light (365 nm) at the intensity of 40 W/cm2 for 5 min.

Preparation of the luminescent precursor

1.0 g PVDF-HFP was dissolved in 40 mL TEAc under magnetic stirred for 24 h. Then, 1 wt% PEGDA, 1 wt% TPO, 2 wt% SiO2 and 10 wt% inorganic phosphors (Y2O2S:Eu,Mg,Ti, SrAl2O4:Eu,Dy and Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu, respectively) were added into the solution, and mixed vigorously for 5 min, obtaining luminescent precursor with different emission.

Construction of the CBCN structure

The obtained OHM layer has a front side (with intensive structural color) and a back side (with weak structural). We poured the luminescent precursor onto the back side of the OHM and allowed it to spread out before curing under 365 nm UV light for 5 min.

Preparation of the polarization patterns by direct ink writing

Firstly, we changed the ratio of SiO2 (4 wt%) and inorganic phosphors (20 wt%) in luminescent precursor to have suitable rheological properties as the printing ink. Then, we employed a pneumatic extrusion type microelectronic printer (MP1100, Prtronic, China) with programmable temperature and pressure control to perform pattern printing on the OHM layer.

Preparation of the core-shell polarization fibers

The luminescent precursor was injected into a low-density polyethylene tube with 1.0 mm inner diameter at a rate of 500 μL/min via a syringe pump (LSP-02). After filling, the tube was kept in a UV curing chamber for 5 min and then immersed in toluene at a temperature of 95 °C for about 30 min to dissolving the LDPE tube, obtaining a pre-bonding fiber. Afterwards, the fiber core was coated with a cholesteric reactive mixture by dip-coating, which is kept in an incubator at room temperature for 24 h to promote cladding layer self-assembly with radial helical structure and to evaporate toluene and then cured at UV curing chamber for another 5 min.

Finite element analysis simulation

A commercial finite element simulation software (ABAQUS) was used to study the stress and strain distribution within the CBCN and physical-stacking bilayer models that were both composed of a OHM layer (the dimension was set as 60 × 15 × 0.22 mm) and a SLG layer (the dimension was set as 48 × 15 × 0.69 mm). In the CBCN model, the two layers were tied by covalent bonds while they are physically bound without chemical bonding in the physical-stacking bilayer model. Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the OHM were set as 0.0074 and 0.4150, respectively, and those of the SLG were set as 0.0013 and 0.3900. When a 50% strain was applied to the OHM layer, the stress and strain distributions of the two models were simulated.

Simulation of a fire scenario

We employed a transparent acrylic box as a sealed space and placed the ignited smoke pellet inside it to generate dense smoke. Then, we used two LED-based vertical flame lamps to create the firelight effect. When the camera captured our circularly polarized optical signals through the acrylic box, the imaging environment is filled with flames and smoke interference, thus achieving an effective fire scenario simulation.

Characterizations

3D-reconstruction images were characterized by a X-ray microscope (Xradia 520 Versa). Cross-sectional SEM images were captured by a field emission scanning electron microanalyzer (Zeiss Supra 40 scanning electron microscope at an acceleration voltage of 3.0 kV). FTIR spectra were measured with a Fourier transform infrared microscope (Nicolet iN10MX). Photo-luminescence spectra were collected on a fluorescence spectrometer (Hitachi F-4700) and transmission spectra were recorded with a UV-Vis-NIF spectrometer (Shimadzu 3700 DUV). Tensile test was measured by a Instron Electronic Dynamic and Static Fatigue Testing Machine (E3000K8953). Circular dichroism spectra and circularly polarized luminescence spectra were measured on a JASCO J-1500 spectrophotometer and a JASCO CPL-300 spectrophotometer, respectively. Circular polarization characteristics of CBCN were demonstrated by converting the generated circularly polarized light to linearly polarized light using a quarter-wave slice (QWP, 350–850 nm, Thorlabs), and then the direction of linear polarization was discriminated by a rotating polarizer (400–700 nm, Thorlabs). Atomic force microscope images were obtained by an Atomic Force Microscope (Demension Icon). Two-dimensional wide-angle X-ray scattering patterns were obtained by using a Wide-angle X-ray Scattering System (Xeuss 3.0). Intensity images were taken by a luminance meter (Hopoocolor, CX-1200-25mm). Thermal imagery was performed by an infrared thermal imager (DELIXI, DM5005). Fluorescence microscopy images were conducted on an upright fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX53) under the excitation of a mercury lamp. Thermogravimetry and differential scanning calorimetry curves were tested by a thermogravimeter (TA Discovery TGA) and a differential scanning calorimeter (Shimadzu DSC-60), respectively. Photographs were taken with two industrial cameras (HIKROBOT) equipped with L- and R-CPFs.

Data availability

The dataset supporting the findings of this study has been deposited in the Zenodo repository44, and is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17112218. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zaidi, A. et al. Metasurface-enabled single-shot and complete Mueller matrix imaging. Nat. Photonics 18, 704–712 (2024).

Lu, J. et al. Nano-achiral complex composites for extreme polarization optics. Nature 630, 860–865 (2024).

Ou, X. et al. High-resolution X-ray luminescence extension imaging. Nature 590, 410–415 (2021).

Liu, F. et al. Deeply seeing through highly turbid water by active polarization imaging. Opt. Lett. 43, 4903–4906 (2018).

Feng, X. et al. Differential perovskite hemispherical photodetector for intelligent imaging and location tracking. Nat. Commun. 15, 577 (2024).

Li, L. et al. Single-shot deterministic complex amplitude imaging with a single- layer metalens. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl0501 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Real-time machine learning-enhanced hyperspectro-polarimetric imaging via an encoding metasurface. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp5192 (2024).

Snik, F. et al. An overview of polarimetric sensing techniques and technology with applications to diferent research fields. Proc. SPIE 9099, 90990B (2014).

Lu, J. et al. High-resolution X-ray circular polarization imaging enabled by luminescent photopolymerized chiral metal-organic polymers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2410219 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Recent progress of circularly polarized luminescence materials from Chinese perspectives. CCS Chem. 5, 2760–2789 (2023).

van der Laan, J. D. et al. Evolution of circular and linear polarization in scattering environments. Opt. Express 23, 31874–31888 (2015).

Xu, M. & Alfano, R. R. Circular polarization memory of light. Phys. Rev. E 72, 065601 (2005).

van der Laan, J. D. et al. Detection range enhancement using circularly polarized light in scattering environments for infrared wavelengths. Appl. Opt. 54, 2266–2274 (2015).

Zheng, Z. et al. Digital photoprogramming of liquid-crystal superstructures featuring intrinsic chiral photoswitches. Nat. Photonics 16, 226–234 (2022).

Zhang, M. et al. Processable circularly polarized luminescence material enables flexible stereoscopic 3D imaging. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi9944 (2023).

Shi, Y. et al. Recyclable soft photonic crystal film with overall improved circularly polarized luminescence. Nat. Commun. 14, 6123 (2023).

Lin, S. et al. Photo-triggered full-color circularly polarized luminescence based on photonic capsules for multilevel information encryption. Nat. Commun. 14, 3005 (2023).

Song, I. et al. Helical polymers for dissymmetric circularly polarized light imaging. Nature 617, 92–99 (2023).

Guo, Q. et al. Multimodal-responsive circularly polarized luminescence security materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 4246–4253 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Mechanically tunable circularly polarized luminescence of liquid crystal-templated chiral perovskite quantum dots. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202404202 (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. Helical-caging enables single-emitted large asymmetric full-color circularly polarized luminescence. Nat. Commun. 15, 251 (2024).

Long, G. et al. Chiral-perovskite optoelectronics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 423–439 (2020).

Zhao, B. et al. Multifarious chiral nanoarchitectures serving as handed-selective fluorescence filters for generating full-color circularly polarized luminescence. ACS Nano 14, 3208–3218 (2020).

Wang, C. T. et al. Fully chiral light emission from CsPbX3 perovskite nanocrystals enabled by cholesteric superstructure stacks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1903155 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Dynamically modulating the dissymmetry factor of circularly polarized organic ultralong room-temperature phosphorescence from soft helical superstructures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202319536 (2024).

Grill, L. & Hecht, S. Covalent on-surface polymerization. Nat. Chem. 12, 115–130 (2020).

Roh, Y. et al. Crumple-recoverable electronics based on plastic to elastic deformation transitions. Nat. Electron. 7, 66–76 (2024).

Ma, J. et al. Mechanochromic and ionic conductive cholesteric liquid crystal elastomers for biomechanical monitoring and human-machine interaction. Mater. Horiz. 11, 217–226 (2024).

Yang, L. et al. Recent progress in inorganic afterglow materials: mechanisms, persistent luminescent properties, modulating methods, and bioimaging applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 11, 2202382 (2023).

Zhang, C. et al. Emergent induced circularly polarized luminescence in host-guest crystalline porous assemblies. Coord. Chem. Rev. 514, 215859 (2024).

Fan, Q. et al. Tunable circular polarization room temperature phosphorescence with ultrahigh dissymmetric factor by cholesteric liquid crystal elastomers. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 4, 101583 (2023).

Lin, S. et al. Light-triggered fluorochromic cholesteric liquid crystal elastomer with hydrogen-bonded fluorescent switch: dualmodal-switchable circularly polarized luminescence. Sci. China Chem. 67, 2719–2727 (2024).

Li, S. et al. When quantum dots meet blue phase liquid crystal elastomers: visualized full-color and mechanically switchable circularly polarized luminescence. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 140 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Three-level chirality transfer and amplification in liquid crystal supramolecular assembly for achieving full-color and white circularly polarized luminescence. Adv. Mater. 37, 2412805 (2025).

Wang, X. et al. Liquid crystals doped with chiral fluorescent polymer: multi-color circularly polarized fluorescence and room-temperature phosphorescence with high dissymmetry factor and anti-counterfeiting application. Adv. Mater. 35, 2304405 (2023).

Liu, S. et al. Circularly polarized perovskite luminescence with dissymmetry factor up to 1.9 by soft helix bilayer device. Matter 5, 2319–2333 (2022).

Choi, Y. et al. Circularly polarized light emission from nonchiral perovskites incorporated into nanoporous cholesteric polymer templates. ACS Nano 18, 909–918 (2024).

Luo, J. et al. Ultrastrong circularly polarized luminescence triggered by the synergistic effect of chiral coassembly and selective reflective cholesteric liquid crystal film. ACS Mater. Lett. 6, 2957–2963 (2024).

Liu, D. et al. Highly efficient circularly polarized near-infrared phosphorescence in both solution and aggregate. Nat. Photonics 18, 1276–1284 (2024).

Takaishi, K. et al. Axially chiral peri-xanthenoxanthenes as a circularly polarized luminophore. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 11852–11857 (2019).

Takaishi, K. et al. Evolving fluorophores into circularly polarized luminophores witha chiral naphthalene tetramer: proposal of excimer chirality rule for circularly polarized luminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 6185–6190 (2019).

Chowdhury, R. et al. Circularly polarized electroluminescence from chiralsupramolecular semiconductor thin films. Science 387, 1175–1181 (2025).

CTIF. World fire statistics, CTIF, Paris, https://ctif.org/world-fire-statistics (2024).

Zhao, S. & Zhuang, T. Covalent-bonding chiroptical network structures for circular polarization differential imaging. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17112218 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China grant (2021YFA1500400, to T.Z.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 22471253, to T.Z.; and 224B2116, to M.Z.), the CAS Talent Introduction Program (Grant KJ2060007002, to T.Z.), the Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation, China (Grant BJ2060190120, to T.Z.), and the Funding of University of Science and Technology of China (Grants KY2060000168 and KY2060000235, to T.Z.). This work was partially carried out at the USTC Center for Micro and Nanoscale Research and Fabrication. This work was partially carried out at the Instruments Center for Physical Science, USTC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Z. conceived the idea and supervised the project. T.Z., S.Z. and M.Z. wrote the paper. S.Z. and M.Z. carried out the experiments and analyzed the results. A.L. and Z.T. helped to prepare figures. G.L., Q.G., Y.Z., Y.W., and J.C. helped to collect the data. All authors discussed the results and assisted during manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shunai che and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, S., Zhang, M., Li, A. et al. Covalent-bonding chiroptical network structures for circular polarization differential imaging. Nat Commun 16, 10644 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65647-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65647-6