Abstract

Organic crystal-based micro/nanostructures with morphology-driven photons/electrons transport characteristics demonstrate exceptional potential for the development of optoelectronic functional materials. However, the construction of continuities and lossless interfaces within multicomponent structures remains a significant challenge, primarily due to inherent material differences and current technology limits. Herein, organic parallel grouping crystals (OPGCs), which devoid of grain boundaries between crystals via a solution viscosity-induced binuclear co-growth strategy, are designed to enhance photon transmission efficiency. Notably, the symbiotic phenomenon among components within OPGCs is precisely regulated by manipulating the solvent viscosity to exceed 0.5 mPa·s through adjustments in factors such as the cooling rate, solvent type, concentration. Compared with the low photon transmission efficiency (2.1%) caused by the discontinuous splicing interface, the elimination of grain boundaries significantly enhances the interlayer photon transmission efficiency of OPGCs, resulting in an overlap degree-dependent adjustable transmission efficiency ranging from 21.3% to 54.9%. This symbiotic strategy demonstrates universality to small molecules, coordination compounds, and cocrystals, enabling the construction of parallel grouping structures comprising single- or multi-component crystals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic low-dimensional crystalline materials have attracted considerable interest within the field of material chemistry owing to their diverse chemical compositions1, large optical cross-sections2, and wide-ranging optoelectronic properties3. Notably, organic hierarchical micro/nanostructures, distinguished by their integrated interface characteristics4,5,6, exceptional structural customizability7, and morphology-driven optoelectronic attributes8, have emerged as promising candidates in the realm of integrated optoelectronics9. Among them, organic parallel multilayer micro/nanostructures demonstrate capabilities in confining and manipulating photons/electrons, alongside exhibiting rectification behavior and the photovoltaic effect10,11, which gives them an advantage in the parallel connection and interconnection of photons and electrons. For example, WS2/graphene multilayer structures featuring highly tailored heterojunctions were utilized to fabricate field-effect transistors (FETs) that exhibit a combination of tunneling and thermionic transport mechanisms12, allowing for current modulation capabilities surpassing 1 × 106 at room temperature and a high ON/OFF ratio.

Significantly, the grain boundary functions as the transitional zone between distinct grains within organic hierarchical micro/nanostructures, and plays a pivotal role in determining the stability and overall optoelectronic performance of hierarchical crystals13,14,15. Achieving precise control over the grain boundary entails optimizing the hierarchical microstructure through accurately regulating the atomic arrangement16, defect distribution17, and chemical composition at the grain boundary during the crystal growth or synthesis processes18,19,20,21. To date, the methodologies used to construct organic hierarchical micro/nanostructures can be categorized into “top-down” and “bottom-up” approaches22,23,24. Specifically, the former employs direct techniques, including simple cutting, adhesion, and splicing, to manipulate the desired geometric configuration25. Nevertheless, the occurrence of interface defects during this process is relatively prevalent and challenging to fully circumvent26, consequently compromising the interface stability of the resulting hierarchical structural materials (Fig. 1a). The bottom-up approach27, which has demonstrated successful rational synthesis of various types of conventional organic hierarchical architectures through an orderly epitaxial growth process based on the principle of lattice matching. However, under actual experimental conditions, achieving perfect lattice matching is difficult. This is mainly due to the differences in lattice constants between different materials (lattice mismatch), which will cause significant lattice superposition or distortion at the interface region, manifested as the periodicity of atomic arrangement being disrupted at the interface28,29, thereby generating dislocations, local strain fields, and other defects. As the epitaxial thickness increases, high-density grain boundary defects will gradually form. Meanwhile, dynamic factors during the growth process and interface strains often result in certain defect structures at the interface, which are inevitably unfeasible under actual growth conditions. Therefore, it is imperative to investigate a strategy for optimizing or eliminating grain boundaries, with the aim of enhancing the stability of hierarchical crystal structures, minimizing the degree of light scattering, and improving the photon transmission efficiency.

In this work, we propose a solution viscosity-induced binuclear co-growth approach for the construction of organic parallel grouping crystals without grain boundaries between hierarchical microstructures (Fig. 1b). The elimination of grain boundaries significantly enhances the connection tightness between microstructures30, and reduces the scattering of photons at the interface, which is crucial for the efficient transmission of photons in organic hierarchical microstructures31. Typically, 1,2,4,5-tetracyanobenzene-benzo[c]phenanthrene (THT) molecules are added into a solvent with relatively high viscosity (η > 0.5 mPa·s), resulting in the adhesion of the two cocrystal particles during the formation of crystal nuclei and forming parallel grouping crystals with non-boundary symbiotic parts during the subsequent growth process. Interestingly, the parallel grouping of microstructures with adjustable lengths of symbiotic parts was realized via finely modulating the cooling rate of the solvents. The visualization of the co-assembly process for organic parallel grouping microstructures was then recorded and verified via theoretical calculations. Furthermore, the controllable construction of parallel grouping microstructures was achieved on the basis of a variety of viscosity control methods, such as the type, concentration, and molar ratio of different solvents. Notably, the interlayer transmission efficiency of photons demonstrated a positive correlation with the overlapping degree. Importantly, this approach exhibited universality not only to monomolecular and multimolecular-based parallel grouping homostructures, but also to heterostructures based on different crystals. This strategy of eliminating grain boundaries provides an avenue to optimize the performance and reliability of optoelectrical circuits.

Results

The typical polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon molecules of benzo[c]phenanthrene (BHT) exhibit a well-defined aromatic π-conjugated structure, characterized by a strong electron-donating capacity (Supplementary Fig. 1a). When combined with the electron acceptor 1,2,4,5-benzeneenetetranitrile (TCNB), which possesses strong electron affinity, BHT molecules can self-assemble into TCNB-BHT (THT) cocrystals in face-to-face mode via charge-transfer (CT) interactions (Supplementary Figs. 1b and 2). It is worth noting that the individual molecular growth morphology of TCNB and BHT are both 1D structures (Supplementary Fig. 3). The THT crystal is categorized within the triclinic space group Pī, whose cell parameters are a = 7.2363 Å, b = 8.0530 Å, c = 16.9259 Å, α = 88.451°, β = 89.127°, and γ = 87.740° (Supplementary Table 1). As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1c, the examination of cocrystals using fluorescence microscopy (FM) distinctly reveals a one-dimensional (1D) single microstructure featuring bright edges and a body that exhibits typical optical waveguide properties. These as-prepared BHT microrods exhibit an average length of 61.6 µm (Supplementary Fig. 1d) and prominent green emission, with a photoluminescence (PL) peak located at 560 nm (Supplementary Fig. 4). Furthermore, the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image further demonstrated the hexagonal prism-like 1D structure and smooth crystal surface of BHT single structures (Supplementary Fig. 5), effectively minimizing the occurrence of light scattering. The observation through transmission electron microscopy (TEM), accompanied by the corresponding selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern of the THT microrods (Supplementary Fig. 6), clearly reveals a high degree of crystallinity oriented along the [100] direction, which is in good agreement with the calculated morphology (Supplementary Fig. 7).

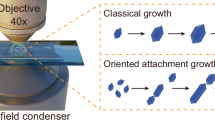

Notably, as the solvent viscosity increases, the THT single crystal structures predominantly appear in the form of parallel grouping crystals, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. Specifically, parallel grouping crystallization occurs during the initial stages when the crystals are relatively small (depicted as Stage I in Fig. 2a). Subsequently, when accompanied by high solvent viscosity, smaller crystals tend to attach and adhere to adjacent crystals along their broader crystalline facets during the metastable growth process of the THT cocrystal (Stage II). Notably, the self-assembly process of the THT cocrystals is dynamic process, which undergoes a morphology evolution from kinetic to thermodynamic states32. During the initial crystallization stage (≤30 s), the THT cocrystals form through a kinetically controlled process where CT interactions drive rapid anisotropic growth along the [100] direction. This resulted in the formation of metastable 1D microcrystals composed of the large (001) top surface, (011), and (010) side surfaces (Supplementary Fig. 8a1), which is consistent with the simulated growth morphology (Supplementary Fig. 8a2). In this non-thermodynamic equilibrium, the crystal is in an unstable metastable state, which is the initial stage of the parallel growth phenomenon we have proposed. The (001) facet’s large surface area provides statistically more sites for secondary nucleation and attachment. Then, increasing the self-assembly time of the THT cocrystals to 60 s, it was found through SEM images and the corresponding simulated growth morphology (Supplementary Fig. 8b) that the side surfaces (011) and (01-1) crystal planes of the THT cocrystals grow rapidly, gradually reaching the thermodynamic equilibrium state. Compared to the (011) and (01-1) faces of the hexagonal prisms that are relatively stable only under thermodynamic morphology, the symbiotic phenomenon always occurs on the (001) crystal surface during the dynamic morphology stage. Generally, these crystals tend to unite in a parallel orientation, with random attachment being uncommon. During the subsequent growth phase (Stage III), growth continues after grouping, finally leading to the integration of multiple microcrystals into a cohesively bound structure.

a Schematic illustration of the co-growth process for organic parallel grouping microcrystals. b SEM image of a typical organic parallel grouping microcrystal. Scale bar: 10 μm. c TEM image of an individual parallel grouping microcrystal. Scale bar: 500 nm. d–f SAED patterns of the corresponding parallel grouping microcrystal labeled as “1” d, “2” e, and “3” f in c. The scale bars are all 2 1/nm. Crystal face indices g and molecular packing arrangement h of a single microrod. i, j Crystal face indices i and molecular packing arrangement j of the parallel grouping microrod. k SEM images of organic parallel grouping microrods with increasing overlapping length from left to right. l Distribution of the overlap degree (ω) of parallel grouping microstructures at different cooling rates.

The external morphology of the crystal in the SEM image indicates the involvement of multiple crystals, and the central zone exhibits a composite crystal core, thereby confirming the involvement of two individual crystals (Fig. 2b). The FM image vividly illustrates the significant differences between single structure and parallel grouping structure within the same field of view (Supplementary Fig. 9). In the co-growth stage, there is a pronounced tendency towards eliminating the initial mismatch among crystals within the parallel grouping relationship through the synchronized growth of bi-nuclei. Consequently, the external irregularities gradually diminish, ultimately resulting in the formation of an integrated crystal without a grain boundary within the interconnected region. The TEM images (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 10) demonstrate a regular external morphology of parallel grouping structures, as well as the uniformity of the intergrowth regions. The corresponding SAED patterns (Fig. 2d, f) reveal a high degree of crystallinity in both the single structure regions and the intergrowth areas. Simultaneously, the growth direction of the symbiotic parts remains consistent with that of their respective single-structure counterparts. Notably, these as-prepared THT parallel grouping structures demonstrate uniformly consistent optical properties across various points within the structure (Supplementary Fig. 11), and maintain both their structural integrity and emission characteristics even after being stored in air for a period of 180 days (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Crystal symbiosis phenomenon occurs when two crystals grow together on a specific face, forming a composition face that serves as the initial planar attachment point33. For the successful formation of parallel grouping structures, it is essential that each component microcrystals possess a dominating surface parallel to the corresponding dominating surface of neighboring microcrystals. This alignment ensures that bonding occurs when the two broad (001) crystal surfaces of the THT cocrystal are in direct contact (Fig. 2g and 2i). Once this bond is established, the two crystals continue to grow intertwined, with their boundaries expanding along the direction of the fastest-growing face, i.e., the [100] direction (Fig. 2h and 2j). Essentially, the presence of parallel grouped crystals constrains the orientation of adjacent crystals, necessitating the simultaneous fulfillment of two conditions (Supplementary Fig. 13): (i) the involvement of two or more crystals, each relatively small in size upon their initial interaction; and (ii) parallelism between a prominent microcrystal surface in and a corresponding surface in another.

The involvement of two or more crystals is pivotal, as it eliminates the possibility of a single crystal growing into a twin or a single irregularly developed crystal34. When dealing with diverse crystals, it is imperative to consider the possibility of an epitaxial relationship, which arises from the nucleation process of one crystal onto the surface of another. Although intergrowth and epitaxy are closely related processes, there are significant differences between them. Specifically, epitaxy entails the formation of nucleation sites for smaller crystals on the face of larger ones35. Conversely, for parallel grouping, crystals initiate independently nucleated and remain small in size during their initial stage of adherence. Consequently, if the microcrystals are comparatively small in size at their initial encounter, the possibility of epitaxial growth can be conclusively excluded. After the growth mechanism of parallel grouping crystals is explored in detail, the precise regulation of the overlapping degree within these crystals is studied. The elevated cooling rate serves as the pivotal factor contributing to the increase in solvent viscosity. The SEM images presented in Fig. 2k clearly illustrate the proportion of the intergrown section within the total length of parallel grouping crystals, referred to as the overlap degree (ω). As the solution cooling rate increased from −3 °C/min to −8 °C/min, the value of ω exhibits an upward trend, ranging from 8.8% to 75.1%. To be specific, when the cooling rate of the solvent for the crystal is less than −3 °C/min, no crystal symbiosis phenomenon will occur (Figure 2k1). Compared with the viscosity observed at relatively slower cooling rates, the solvent viscosity at higher cooling rates increases, resulting in a more substantial overlap when two crystals are in contact (Fig. 2k2-k6). This finding highlights the significant correlation between the cooling rate of the solvent and the degree of crystal overlap (Fig. 2l). The difference in the degree of overlap arises from the viscosity-dependent kinetics of crystal fusion during early growth stages. In high-viscosity solutions, the dense molecular network formed by strong intermolecular interactions creates a confined environment, which restricts the movement of crystals and thus provides sufficient time for the fusion of crystals between adjacent regions. This prolonged contact period facilitates more extensive overlap before further growth occurs. Conversely, in low-viscosity solutions, enhanced molecular mobility reduces the effective contact duration between growing crystals, limiting their ability to achieve optimal alignment and resulting in less overlap. The final crystal morphology is the direct result of the interaction between the solution viscosity and the contact time between the crystals during the crucial initial fusion stage.

Furthermore, through the calculation results of molecular dynamics simulation36, the microscopic mechanism and dynamic characteristics of the symbiosis process of parallel grouping crystals are investigated in detail. As depicted in Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 14, in the initial state (Supplementary Data 1), the TCNB and BHT molecules are uniformly yet disorderly distributed throughout the system. Then, at 10 ns, the assembled molecules initially tend to aggregate with this aggregation trend marginally increasing at 20 ns. Subsequently, at 30 ns, the assembled molecules start to adopt a rod-like shape, a trend that becomes more evident by 40 ns. As the system further evolves to t = 50 ns, two rod-like crystal nuclei initially form in the upper left and lower right corners. By t = 60 ns, the rudimentary form of the rod-like crystal nucleus is established, and the aggregation of the assembled molecules becomes particularly significant. At t = 80 ns, parallel intergrowth is observed between the two nuclei. Ultimately, the complex nucleus undergoes rapid expansion, forming a prominent nucleus characterized by a distinct symbiotic structure at 90 ns (Supplementary Data 2).

During the intergrowth process, the energy variation curve clearly shows that when two crystals engage in symbiotic growth, the combined energy is slightly greater than that of a single crystal (Fig. 3b). As previously mentioned, this phenomenon is attributed to the fact that intergrowth typically occurs on the largest crystal face (Supplementary Table 2), which is the relatively stable surface within the system. Consequently, when this stable crystal face is eliminated during the intergrowth process (i.e., it connects with other crystals to form a symbiotic structure), the total energy of the system experiences a slight increase37, but remains in a stable state.

Meanwhile, the in-situ visualizations and recordings of the morphological evolution of organic parallel grouping architectures were conducted via fluorescence microscope, which provides more direct insight into the growth mechanism occurring during the co-growth process of symbiotic structures devoid of grain boundaries. As depicted in Fig. 3c at the initial stage when the crystals are relatively small, they establish a symbiotic relationship in a parallel orientation. As growth progresses, these two crystals continue to integrate seamlessly, ultimately forming a cohesively bound unit. The resulting morphology clearly indicates the involvement of two crystals, with the central zone featuring a composite crystal core.

The viscosity (η) of solvents plays a pivotal role in the fabrication of organic parallel grouping crystals. To conduct a comprehensive investigation of the viscosity-dependent assembly of organic parallel grouping microstructures, various factors that influence viscosity, including the cooling rate, type of solvent, and solvent concentration, were employed to accurately quantify the co-growth process. As evidenced by the FM images presented in Fig. 4a, f, when the cooling rate increases from −3 to −8 °C/min (Fig. 4g), the viscosity of the solvents notably increases from 0.38 to 1.16 mPa·s. Correspondingly, the probability of crystal symbiosis significantly increases from 0% to 86%, which effectively proves the effect of viscosity on crystal symbiosis. It is necessary to point out that a rapid cooling rate also enhances the nucleation rates due to the higher supersaturation, which could lead to more individual crystals rather than parallel grouping of crystals. The experimental results shown in Fig. 4h, i demonstrate that while a higher nucleation rate will increase the number of crystals, the symbiotic process requires continuous contact between the particles, and this process is largely dependent on the viscosity of the solvents. For example, although DCM exhibits significantly higher nucleation rates due to its lower boiling point and faster evaporation rate, we observed substantially less crystal symbiosis in DCM (27.9%) compared to IPA (90.4%). This critical difference can be attributed to IPA’s higher viscosity (3.18 mPa·s) than DCM (0.68 mPa·s), which effectively restricts crystal mobility and promotes sustained interparticle contact necessary for symbiosis. Therefore, crystal symbiosis requires not only the formation of multiple nuclei, but also the maintenance of physical contact between these nuclei long enough for stable attachments to form.

a–f FM images of organic microrods with increasing parallel grouping frequency as the solvent viscosity (η) increases. g Time-dependent viscosity curve at different cooling rates; the solvent was DCM and the initial concentration was 20 mmol/L. h Concentration-dependent viscosity curve in different solvents. i Relationship between the frequency of parallel grouping crystal and the solvent viscosity.

It is worth noting that although the observed viscosity changes are related to the difference in cooling rates, the viscosity of the solvent itself is not directly dependent on the cooling rate. The significant increase in viscosity is mainly due to the faster cooling rate leads to a lower final temperature within the crystallization period compared to a slower cooling rate. Since solvent viscosity is intrinsically temperature-dependent, the lower temperature attained under rapid cooling results in higher viscosity38. In other words, the apparent viscosity difference arises because the two cooling rates drive the system to different temperature states within the same duration.

Furthermore, the slight change in viscosity resulting from the concentration also influences the symbiotic relationship of the crystal (Fig. 4h). For the THT cocrystal in the solvent system with a VDCM:VEtOH ratio of 1:2 at a concentration (c) of 3 mmol/L, crystal growth primarily occurred in the form of individual structures (Supplementary Fig. 15a–c). However, as the concentration increased to 7 mmol/L, the aggregation of the crystals became more pronounced (Supplementary Fig. 15d–j). While increasing the concentration may increase the tendency for crystal symbiosis, it also results in the deterioration of the crystal morphology due to excessive aggregation (Supplementary Fig. 15h, i).

It is well known that the different types of solvents exhibit distinct viscosity characteristics, thereby rendering the selection of a solvent a potent means to adjust the viscosity of the system. By altering the type of solvent, precise control over the fluidity of the solution was achieved, enabling an effective investigation of the effect of viscosity on the symbiosis of crystals. As illustrated in Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 16, the crystals exhibit virtually no symbiotic interaction within the solvent system consisting of low viscosity acetonitrile (ACN) or dichloromethane (DCM). However, in solvent systems with relatively high viscosities, such as methanol (MeOH), cyclohexane (CYH), or ethanol (EtOH), the crystals undergo gradual aggregation and symbiotic phenomena. Notably, when isopropyl alcohol (IPA) serves as a solvent, its relatively high viscosity induces multiple symbiotic interactions among crystals, as manifested by the stepped structure on the surface of the crystal. The viscosity of a solution is determined by the strength and density of the intermolecular interactions between different molecules in the solution (Supplementary Figs. 17–19). It directly controls the mobility of solvent and solute molecules at the crystal-solution interface. In high-viscosity solutions, strong intermolecular interactions form a dense network that hinders the movement of molecules by suppressing rapid and disordered collisions, and promoting the gradual alignment of crystal surfaces, thereby providing sufficient time for the rearrangement of the solvent layer and for the crystals to explore the optimal lattice matching direction, ultimately leading to the aggregation and growth of crystals.

Furthermore, the volume ratio of MeOH to IPA was precisely regulated to investigate the impact of solvent-induced viscosity variations on the crystal growth morphology (Supplementary Fig. 20). As the volume ratio of VMeOH: VIPA transitions from 10:0 to 2:8, the probability of crystal symbiosis significantly increases from 9.2% to 84.3%. Upon further transitioning the ratio to 1:9 and eventually to 0:10, the crystals predominantly exhibit multiple symbiotic phenomena dominated by IPA. Similarly, through accurate modulation of the volume ratio of MeOH solvent to the higher-viscosity CYH solvent, FM images demonstrated a substantial increase in the probability of crystal symbiosis from 9.2% to 80.4% (Supplementary Fig. 21). Consequently, the increase in viscosity resulting from variations in the cooling rate, solution concentration, and solvent type is positively correlated with an increased probability of crystal symbiosis (Fig. 4i).

The enhancement of photon transmission efficiency within organic low-dimensional hierarchical crystals has attracted significant attention due to its profound application potential in advanced optoelectronics39, such as photonic network40, energy conversion41, and data storage42. The multilayer microstructures featuring face-to-face arrangements and tunable junction interfaces are advantageous for optimizing the photon transmission efficiency. Nevertheless, multilayer microstructures are often constructed through mechanical splicing in traditional micromanipulation techniques, resulting in low photon transmission efficiency43. The inefficiency is attributed primarily to potential discontinuities44, defects45, and impurities at the splice interface46, along with the reflection, scattering, and absorption of photons within the multilayer microstructures47. For example, when micromanipulation techniques are employed48, the two crystals are mechanically spliced in parallel alignment via a specialized probe (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 22). The obtained multilayer microstructure possesses a distinct splicing interface within its confines (Fig. 5b and inset of Fig. 5c). The photon transmission efficiency of the mechanically spliced microstructure was investigated with a homemade μ-PL system (Supplementary Fig. 23). Interestingly, regardless of the location of light excitation within any given layer of the mechanically spliced microstructure, almost no optical signal was detected in the adjacent layers, as demonstrated in the inset of Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 24. The splicing interface between the multilayer microstructures causes the photon transmission across different layers to be discontinuous, leading to an interlayer photon transmission efficiency of only 2.1% (Fig. 5c).

a Bright-field micrograph illustrating the crystal splicing process through a probe. b Schematic representation of the hierarchical microstructure through mechanical splicing at the interface (left), and parallel grouping crystal through the co-growth process without grain boundary (right). c Spatially resolved PL spectra obtained from output channels in the spliced crystal. Inset: i FM image of the spliced crystal. ii FM image collected from the spliced crystal by excitation with a laser beam at a distance of 20 μm from OIII. d, e Spatially resolved PL spectra obtained from tips in parallel grouping crystals with different overlapping degree. Inset: i FM images of parallel grouping crystals. ii FM images collected from the parallel grouping microstructures by excitation with a laser beam at a distance of 20 μm from OIII. f Overlapping degree-dependent PL intensity at different optical output channels. g Interlayer photon transmission efficiency versus overlap degree of parallel grouping crystals.

The discontinuity of interfaces within organic hierarchical crystalline microstructures leads to the obstruction of photon transmission pathways and energy loss, thus constraining the potential performance of optoelectronic devices49. Notably, the organic parallel grouping microstructures designed on the basis of a symbiotic mechanism address the problem of low interlayer photon transmission efficiency caused by the discontinuity of the crystal interface (Fig. 5b). Specifically, as illustrated in the inset of Fig. 5d, when excited by ultraviolet light (λ = 380 nm), the photons guided by the seamless interface connecting the two crystals within the organic parallel grouping microstructure, exhibit an active waveguide mode and propagate efficiently through both crystals. Thus, optical signals were detected at all channels of the organic parallel grouping microstructure, and the interlayer photon transmission efficiency was significantly enhanced to 21.3% (Fig. 5d). Therefore, by integrating symbiotic components within the parallel grouping microstructures, a seamless and efficient photon transmission channel is established, which effectively overcomes the photon transmission limitations imposed by interfaces.

Furthermore, it should be noted that under identical excitation positions, parallel grouping microstructures with varying overlap degrees demonstrate distinct photon transport efficiencies (Fig. 5d, e and Supplementary Fig. 25). As depicted in Fig. 5f, a gradual increase in the degree of overlap results in an increase in the PL intensity at the two outports located within the layer that is indirectly excited, thereby indicating increase in the photon transmission efficiency across the layers. During the precise adjustment of the overlap degree within organic parallel grouping microstructures from 9.8% to 70.0%, the corresponding interlayer transmission efficiency of photons increased from 21.3% to 54.9% (Fig. 5g). This improvement is attributed to the increased area proportion of the symbiotic segments, which results in a more concentrated and efficient photon transmission pathway within the hierarchical microstructure, leading to the transmission of photons predominantly within a single symbiotic structure, and ultimately enhancing the overall photon transmission efficiency. Consequently, notable disparities exist in the photon interlayer transmission efficiency between spliced crystals and symbiotic crystals when they exhibit the same overlapping degree. The seamless continuity and impeccable integrity of symbiotic crystals devoid of grain boundaries facilitate the transmission of photons with markedly enhanced efficiency, which facilitates the development of optoelectronics.

Notably, the viscosity-dependent strategy for constructing organic parallel grouping microstructures, which operates without the confines of brain boundaries, can be generalized to a series of organic systems, clarifying its broad applicability. Firstly, the parallel grouping microstructures were fabricated utilizing single-molecule systems as their foundation. As presented in Fig. 6a, small organic molecules and coordination complexes were respectively selected as the components of single-molecule systems for constructing parallel grouping structures. Notably, with increasing solvent viscosity, these monomolecular crystals exhibited a significant symbiotic phenomenon. Then, a series of acceptor and donor molecules with different electron-deficient and electron-donating capabilities were selected to construct parallel grouping microstructures on the basis of the multimolecular system (Fig. 6b). Depending on the charge transfer (CT) interaction, a diverse array of targeted symbiotic microstructures exhibiting tunable emission colors spanning from blue to red, and even extending to the near-infrared (NIR) range were successfully prepared (Supplementary Fig. 26). Typically, acceptor molecule 1 and donor molecule 5 self-assemble to form a cyan-emissive 1&5 parallel grouping microstructure, exhibiting a CIE coordinate of (0.20, 0.35) and a high degree of crystallinity, as confirmed in Fig. 6b, d. Likewise, an NIR-emissive 8&12 parallel grouping microstructure was successfully synthesized through a solution viscosity-induced symbiosis process (Fig. 6b). The CIE coordinates of cocrystals with different colors are detailed in Supplementary Table 3 and Fig. 6d.

a Chemical structures and FM images of single molecules including 1–4 for single structures (top) and parallel grouping structures (bottom) based on single crystal. b Chemical structures of the cocrystal component molecules including 5–9 (acceptors) and 10–13 (donors) as well as FM images of single structures and parallel grouping structures based on cocrystals. c1 Schematic representation of the heterogeneous integration of the parallel grouping microstructure. c2–c4 FM images of cocrystals 6&13 c2, and 9&13 c3, parallel grouping heterostructure 6&13&9 c4. c5 SEM image of parallel grouping heterostructure 6&13&9 corresponding to c4. d CIE chromaticity diagram of these single crystals and cocrystals in a and b.

Furthermore, based on cocrystal engineering, two crystals possessing similar lattices are introduced into a shared high-viscosity solution system to construct a parallel grouping heterostructure (Fig. 6c1–c3). Upon complete solvent evaporation, these crystals form a symbiotic relationship, exhibiting distinct luminescence properties within a parallel grouping heterostructure (Fig. 6c4). The fusion capability of the 6&13&9 parallel grouping heterostructure stems primarily from the lattice compatibility between 6&13 and 9&13 cocrystals. Both crystallize in the triclinic system with closely matched unit cell parameters: a6&13 = 7.23 Å, b6&13 = 8.05 Å, c6&13 = 16.93 Å, a9&13 = 7.39 Å, b9&13 = 9.27 Å, and c9&13 = 16.05 Å, while the high-viscosity solution provides critical kinetic control by suppressing random Brownian motion. This allows sufficient time for molecular reorganization at the crystal interface. Notably, SEM observation visually revealed the symbiotic region within the parallel grouping heterostructure. Unlike the obvious heterogeneous interfaces presented by the heterostructures proposed in previous studies, the parallel grouping heterostructure only displays the feature of two crystals growing together at their termini, whereas the symbiotic region is presented as a seamless, integrated entity without any heterogeneous interfaces (Fig. 6c5). Moreover, the spatial resolution spectra obtained by the focusing laser beam (λ = 380 nm) at tip 1 and tip 2 of the parallel grouping heterostructure display the same PL peaks as those of cocrystals 6&13 and 9&13, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 27). The spectral analysis of the symbiotic region simultaneously revealed emission peaks corresponding to both cocrystals, indicating a tight symbiotic nature between the two cocrystals. Additionally, both the as-fabricated single crystals and cocrystals exhibit excellent photon confinement and optical waveguide performance (Supplementary Figs. 28–33), which ensures efficient photon transmission and lays a solid foundation for the construction of high-performance optoelectronic devices.

Discussion

In summary, organic parallel grouping crystals without grain boundaries were successfully constructed via a solution viscosity-induced binuclear co-growth strategy. The precise adjustment of the solvent viscosity demonstrated that high-viscosity solvents could induce symbiotic crystallization, and real-time visualizations of the organic parallel grouping microstructures were recorded and verified via theoretical calculations. Notably, the length of the symbiotic parts within the parallel grouping microstructure was finely modulated through accurate manipulation of the solution cooling rate. Furthermore, parallel grouping structures with non-grain boundaries not only efficiently improve the interlayer photon transmission efficiency but also exhibit a positive correlation between the efficiency and the degree of overlap. This co-assembly strategy demonstrates fascinating universality across all organic systems, applying not only to monomolecular and multimolecular-based parallel grouping homostructures, but also to heterostructures based on different crystals, which provides an avenue to optimize the performance and reliability of optoelectrical devices.

Methods

Preparation of single microstructures

Through a typical facile solution evaporation method, 0.02 mmol (3.6 mg) of TCNB and 0.02 mmol (4.6 mg) of BHT were dissolved in 10 mL of DCM, yielding a THT stock solution with a concentration of 2.0 mmol L−¹. Subsequently, this THT stock solution was added to 10 mL of EtOH, and the resultant mixture was carefully dispensed onto a flat or concave substrate. Upon complete evaporation of the solvents, organic single microstructures were observed from the substrate.

General method for the synthesis of parallel grouping microstructures

To ensure uniformity of the solvent microenvironment in all experiments, we used a concave substrate to confine the solution within a specific area, thereby avoiding the uncontrollable diffusion and local density changes that might occur on flat substrates. Then, through a typical facile solution evaporation method, 0.05 mmol (9.0 mg) of TCNB and 0.05 mmol (11.5 mg) of BHT were dissolved in 10 mL of DCM, yielding a THT stock solution with a concentration of 5.0 mmol L−¹. Subsequently, this THT stock solution was added to 10 mL of EtOH, and the resultant mixture was carefully dispensed onto a concave substrate with a glass cover. Upon complete evaporation of the solvents, organic parallel grouping microstructures were observed from the substrate.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are provided in the paper or Supplementary Information. Data is available from the corresponding authors on request. Crystallographic data are available free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC 2431461; 2431462; 2431463; 2431732).

References

Price, S. L. Predicting crystal structures of organic compounds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 2098–2111 (2014).

Albota, M. et al. Design of organic molecules with large two-photon absorption cross sections. Science 281, 1653–1656 (1998).

Zhang, Q. et al. Recent progress in emerging two-dimensional organic–inorganic van der Waals heterojunctions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 3096–3133 (2024).

Ahn, J. et al. Micro-/Nanohierarchical structures physically engineered on surfaces: analysis and perspective. Adv. Mater. 36, 2300871 (2024).

Wan, N. et al. Large-scale integration of artificial atoms in hybrid photonic circuits. Nature 583, 226–231 (2020).

Chandrasekar, R. Mechanophotonics—mechanical micromanipulation of single-crystals toward organic photonic integrated circuits. Small 17, 2100277 (2021).

Wan, C., Dong, H., Jiang, L. & Hu, W. P. Organic semiconductor crystals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 422–500 (2018).

Ma, Y. X. et al. Organic low-dimensional heterojunctions toward future applications. Matter 5, 3706–3739 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Photovoltaic nanocells for high-performance large-scale-integrated organic phototransistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 1323–1332 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Supramolecular linear heterojunction composed of graphite-like semiconducting nanotubular segments. Science 334, 340–343 (2011).

Lauhon, L. J., Gudiksen, M. S., Wang, D. & Lieber, C. M. Epitaxial core–shell and core–multishell nanowire heterostructures. Nature 420, 57–61 (2002).

Georgiou, T. et al. Vertical field-effect transistor based on graphene–WS2 heterostructures for flexible and transparent electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 100–103 (2013).

Islangulov, R. R., Lott, J., Weder, C. & Castellano, F. N. Noncoherent low power upconversion in solid polymer films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 12652–12653 (2007).

Wang, K. et al. Two-dimensional-lattice-confined single-molecule-like aggregates. Nature 633, 567–574 (2024).

Feng, X. et al. Spatially resolved organic whispering-gallery-mode hetero-microrings for high-security photonic barcodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 135, 1632 (2023).

Ma, Y. X. et al. Oriented self-assembly of hierarchical branch organic crystals for asymmetric photonics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 9285–9291 (2023).

Ma, Y. X., Chen, S., Lin, H. T., Zhuo, S. P. & Wang, X. D. Organic low-dimensional crystals undergoing twinning deformation. Sci. Bull. 67, 1632–1635 (2022).

Zhao, S. et al. Programmable in-situ co-assembly of organic multi-block nanowires for cascade optical waveguides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 136, e202412712 (2024).

Qin, Z., Gao, C., Gao, H., Wang, T. & Hu, W. P. Molecular doped, color-tunable, high-mobility, emissive, organic semiconductors for light-emitting transistors. Sci. Adv. 8, eabp8775 (2022).

Bogaerts, W. et al. Programmable photonic circuits. Nature 586, 207–216 (2020).

Hao, M. et al. Flattening grain-boundary grooves for perovskite solar cells with high optomechanical reliability. Adv. Mater. 35, 2211155 (2023).

Fukino, T. et al. Manipulation of discrete nanostructures by selective modulation of noncovalent forces. Science 344, 499–504 (2014).

Dean, C. et al. Boron nitride substrates for high-quality graphene electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 722–726 (2010).

Flory, N. et al. Waveguide-integrated van der Waals heterostructure photodetector at telecom wavelengths with high speed and high responsivity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 118–124 (2020).

Ranjan, S., Kumar, A. V., Chandrasekar, R. & Takamizawa, S. Spatially controllable and mechanically switchable isomorphous organoferroeleastic crystal optical waveguides and networks. Nat. Commun. 15, 7478 (2024).

Kumar, A. V. et al. Capturing the interplay between TADF and RTP through mechanically flexible polymorphic optical waveguides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202411054 (2024).

Freymann, G., Kitaev, V., Ozin, G. A. & Lotsch, B. V. Bottom-up assembly of photonic crystals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 2528–2554 (2013).

Shi, Y. et al. Bottom-up growth of n-type monolayer molecular crystals on polymeric substrate for optoelectronic device applications. Nat. Commun. 9, 2933 (2018).

Li, P. et al. Bottom-up construction of a superstructure in a porous uranium-organic crystal. Science 356, 624–627 (2017).

Rivnay, J. et al. Large modulation of carrier transport by grain-boundary molecular packing and microstructure in organic thin films. Nat. Mater. 8, 952–958 (2009).

Chu, Z. et al. Impact of grain boundaries on efficiency and stability of organic-inorganic trihalide perovskites. Nat. Commun. 8, 2230 (2017).

Wu, B. et al. Dynamic epitaxial growth of organic heterostructures for polarized exciton conversion. Adv. Mater. 35, 2206272 (2023).

Parkinson, G. N., Lee, M. P. H. & Neidle, S. Crystal structure of parallel quadruplexes from human telomeric DNA. Nature 417, 876–880 (2002).

Cölfen, H. & Antonietti, M. Mesocrystals: Inorganic superstructures made by highly parallel crystallization and controlled alignment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 5576–5591 (2005).

Xu, C. et al. A general method for growing two-dimensional crystals of organic semiconductors by “solution epitaxy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 9519–9523 (2016).

Sosso, G. C. et al. Crystal nucleation in liquids: Open questions and future challenges in molecular dynamics simulations. Chem. Rev. 116, 7078–7116 (2016).

Wang, K. et al. Stimulated emission-controlled photonic transistor on a single organic triblock nanowire. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 13147–13150 (2018).

Hou, F., Martin, J. D., Dill, E. D., Folmer, J. C. W. & Josey, A. A. Transition zone theory of crystal growth and viscosity. Chem. Mater. 27, 3526–3532 (2015).

Yu, P., Zhen, Y., Dong, H. & Hu, W. Crystal engineering of organic optoelectronic materials. Chem 5, 2814–2853 (2019).

Clark, J. & Lanzani, G. Organic photonics for communications. Nat. Photonics 4, 438–446 (2010).

Dharmarwardana, M. et al. Rapidly reversible organic crystalline switch for conversion of heat into mechanical energy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 5951–5957 (2021).

Tang, Y. Y., Zeng, Y. L. & Xiong, R. G. Contactless manipulation of write–read–erase data storage in diarylethene ferroelectric crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 8633–8640 (2022).

Benabid, F., Couny, F., Knight, J. C., Birks, T. A. & Russell, P. St. J. Compact, stable and efficient all-fibre gas cells using hollow-core photonic crystal fibres. Nature 434, 488–491 (2005).

Duan, X., Gimble, F. S. & Quiocho, F. A. Crystal structure of PI-SceI, a homing endonuclease with protein splicing activity. Cell 89, 555–564 (1997).

Choi, H. H. et al. Hall effect in polycrystalline organic semiconductors: The effect of grain boundaries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1903617 (2020).

Junggeburth, S. C. et al. Ultrathin 2D coordination polymer nanosheets by surfactant-mediated synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 6157–6164 (2013).

Khodasevych, I. E., Wang, L., Mitchell, A. & Rosengarten, G. Micro- and nanostructured surfaces for selective solar absorption. Adv. Opt. Mater. 3, 852–881 (2015).

Annadhasan, M. et al. Mechanophotonics: Flexible single-crystal organic waveguides and circuits. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 13852–13858 (2020).

Yao, Y., Zhang, L., Leydecker, T. & Samorì, P. Direct photolithography on molecular crystals for high performance organic optoelectronic devices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 6984–6990 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 524B2169; 52173177), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (nos. BK20221362; BK20230010; BK20240830). Furthermore, this project is funded by the Jiangsu Key Laboratory for Carbon-Based Functional Materials & Devices, Soochow University (KJS2156), Collaborative Innovation Center of Suzhou Nano Science & Technology, the 111 Project, Joint International Research Laboratory of Carbon-Based Functional Materials and Devices, and Soochow University Tang Scholar.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.-D. Wang designed the experiments. Y.-X. Ma and W.-H. Li synthesized the organic crystals and performed the structural characterization. M.-Y. Zhang and S. Zhao performed the optical characterization. Z.-J. Lv performed the viscosity characterization. Y.-X. Ma, H.-T. Lin, L.-S. Liao and X.-D. Wang discussed the results and wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, YX., Li, WH., Zhang, MY. et al. Organic parallel grouping crystals without grain boundary. Nat Commun 16, 10647 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65650-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65650-x