Abstract

Quiescent muscle stem cells (MuSCs) respond to exercise; however, the coordinated regulation of increased loading, exerkines, and quiescence signaling remains unclear. We found that increased loading reduces calcitonin receptor (CalcR) expression, and forced activation of protein kinase A (PKA), a downstream of CalcR signaling, suppresses MuSC proliferation. Although MuSC-specific Calcr knockout (C-cKO) alone is insufficient, exercised C-cKO mice exhibit significant MuSC proliferation independent of increased loading. Reinforcement of CalcR signaling, either through PKA induction or Yap1 depletion, suppresses MuSC proliferation. Load-independent MuSC proliferation is also suppressed by the deletion of gp130 in C-cKO mice. Serum from exercised mice recapitulates MuSC proliferation in all analyzed muscles of sedentary C-cKO mice, which is abrogated by anti-IL-6 antibodies, and we find cross-talk between CalcR and gp130 signaling via Yap1 phosphorylation. Together, our findings reveal an integrated mechanism by which increased loading, exerkine-gp130, and CalcR signaling converge to fine-tune MuSC activity during exercise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Movement constitutes the fundamental capability of animals to acquire energy and respond to crises. When “movement” exceeds a certain threshold, it is classified as “exercise,” which is defined as a planned, structured, and repetitive activity1. Skeletal muscle, predominantly composed of multinucleated myofibers, plays a critical role not only in allowing movement but also in exerting various additional effects in response to exercise. Exercise affects homeostasis and longevity of organisms in different species. Swimming has been shown to protect Caenorhabditis elegans from arsenite-induced mortality2. In both humans and mice, exercise has the potential to alleviate the effects of aging3 and reduce susceptibility to various diseases, including cancer4 and depression5. These systemic effects are considered to be mediated by myokines or exerkines released from myofibers into the bloodstream4,6.

Muscle stem (satellite) cells (MuSCs) are indispensable for skeletal muscle development, regeneration, and hypertrophy. Under steady-state conditions, MuSCs remain in a mitotically quiescent state7,8 through several signaling pathways9,10. However, when muscle experiences injury or mechanical loading due to exercise, MuSCs exit quiescence and enter a proliferative state. Of note, accumulating evidence suggests that MuSC proliferation in loaded muscles occurs without overt signs of myofiber death or regeneration11,12,13. Moreover, MuSC behaviors differ between regenerating and loaded muscles. In contrast to the regenerative process, in loaded muscles, nearly all MuSC-derived myonuclei are located peripherally within myofibers, and MyoD expression is either undetectable or low in proliferating MuSCs14,15. However, the contribution of myofiber damage to MuSC proliferation in exercised animals cannot be completely excluded. Multiple lines of evidence indicate that exerkine expression can occur independently of muscle injury16,17,18. Therefore, demonstrating that exerkines can induce systemic MuSC proliferation under sedentary conditions would provide compelling evidence for an injury-independent mechanism of MuSC proliferation in adult skeletal muscle. To date, no study has successfully induced systemic MuSC proliferation through exercise-related factors in sedentary conditions.

The activation and proliferation of MuSCs are contingent upon the type of exercise. Treadmill running is commonly employed in the field of exercise physiology; high-intensity (fast-speed) and short-duration training mimics explosive training, whereas low-intensity (slow-speed) and long-duration training models endurance training. Wheel-running is a moderate-intensity, long-duration exercise typically classified as an endurance-style physical activity within the exercise paradigm. Studies have shown that high-intensity exercise induces muscle damage, which is believed to be associated with MuSC activation/proliferation19. Meanwhile, a previous study indicated that wheel-running induces MuSC proliferation in plantar flexor muscles with minimal muscle damage20,21. In addition, wheel-running stimulates exerkine production, including factors that promote MuSC proliferation4. However, in wheel-running mice, MuSC proliferation occurs only in specific muscles in a load-dependent manner20. Given that exercise exerts systemic effects through circulating factors, these factors might influence MuSCs across all muscles. Nevertheless, MuSCs in muscles not subjected to increased load during exercise remain quiescent. It is unclear whether the levels of systemic factors are insufficient to induce MuSC proliferation or whether MuSCs possess intrinsic mechanisms that inhibit the effects of these systemic factors.

The calcitonin receptor (CalcR), a G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), maintains MuSC quiescence through the PKA/Yap1 axis22,23,24 and serves as a prominent marker for detecting quiescent MuSCs in both mice and humans25,26. The loss of CalcR leads to transient expression of cell-cycle-related molecules and a time-dependent reduction in the MuSC pool22. However, MuSCs lacking Calcr do not undergo cell division in non-damaged muscle22. In a surgical resistance training model (an intense exercise regimen that induces muscle hypertrophy), the number of MuSCs expressing CalcR decreases27; yet, the impact of CalcR signaling on MuSCs in a physiological exercise model remains unexplored.

In this study, voluntary wheel-running was used as the exercise model due to its low risk of muscle damage and its potential to enhance exerkine secretion. Initially, we observed that MuSCs in specific muscles proliferated in response to the increased loading induced by exercise, with activated/proliferating MuSCs losing CalcR expression. Activation of Protein Kinase A (PKA), a downstream effector of CalcR signaling, inhibited the increased number of MuSC-derived new myonuclei, suggesting that downregulation of CalcR signaling is crucial for MuSC proliferation in muscles experiencing increased loading. Notably, we observed that Calcr-deficient MuSCs proliferated in response to exercise independent of increased loading, and that exerkines promoted their proliferation in all examined muscles of sedentary mice. Mechanistically, IL-6 within exerkines was involved in the proliferation of Calcr-depleted MuSCs by enhancing the nuclear accumulation of Yap1. Therefore, the loss of CalcR signaling enables MuSCs to proliferate independently of injury, and their expansion can be artificially induced by modulating CalcR and IL-6 signaling.

Results

Increased loading-dependent MuSC proliferation in running mice

Voluntary wheel-running is an exercise model in which rodents are intrinsically motivated to engage in spontaneous running, leading to activated anabolic pathways due to increased loading on the plantar flexor muscles compared to a sedentary condition28. To assess the effects of exercise on MuSC behavior, we analyzed the following muscles: three plantar flexor muscles (soleus, plantaris (PLA), and gastrocnemius (GC)), two dorsiflexion muscles (tibialis anterior (TA), extensor digitorum longus (EDL)), quadriceps (Qu), gluteus maximus (GM), and triceps (Tri) muscles after 2 weeks of wheel-running (Fig. 1A, B). Proliferating MuSCs during the exercise period were labeled with EdU, and the number of EdU+ myonuclei was quantified as MuSC-derived myonuclei generated through MuSC-myofiber fusion (Fig. 1A, C, D). Recently, Ismaeel and colleagues demonstrated that non-proliferating (EdU-) MuSCs can also fuse with myofibers in overloaded muscles29. Therefore, although this assay is restricted to myonuclei derived from proliferated MuSCs and may underestimate the overall contribution of MuSCs, a substantial number of EdU+ myonuclei were detected in the soleus and PLA muscles of exercised mice. In contrast, neither control nor exercised mice exhibited EdU+ myonuclei in the TA and EDL muscles (Fig. 1C, D, and Fig. S1A). These results align with previous findings demonstrating increased MuSC incorporation into myofibers in the soleus and PLA muscles, but not in the TA muscles, of wheel-running mice20. In other muscles (except the GM), a slight but significant increase in the number of EdU+ myonuclei was observed (Fig. 1D). To further examine the cell cycle state of MuSCs, we quantified the frequency of Ki67+ cells in MuSCs from the TA, EDL, PLA, and soleus muscles after 4 or 7 days of exercise (Fig. 1E). In a study that simulated the mechanical work during trotting using a mouse hindlimb musculoskeletal model, the ankle plantar flexor muscles showed greater work compared to the dorsiflexor muscles30. Therefore, the TA and EDL muscles were classified as non-increased-loading muscles (defined here as muscles where exercise does not induce an increase in MuSC-derived myonuclei), whereas the PLA and soleus muscles were categorized as increased-loading (where exercise leads to a substantial increase in MuSC-derived myonuclei). Consistent with the EdU+ data, the frequency of Ki67+ MuSCs was significantly higher in the soleus and PLA muscles compared to the TA and EDL muscles (Fig. 1F, G, and Fig. S1B). Notably, the number of central myonuclei, a hallmark of regenerated myofibers, was scarce in both the soleus and PLA muscles, indicating that MuSC proliferation in exercised mice occurs without overt signs of muscle regeneration (Fig. S2).

A Experimental scheme for the analyses of exercising or sedentary male mice utilizing a voluntary wheel-running cage (+Ex, both leg of n = 2–4) or a conventional housing cage (-Ex, both leg of n = 2–4). B Anatomical position of plantar flexor muscle (Plantaris (PLA), soleus, gastrocnemius muscle (GC)), dorsiflexor muscles (tibialis anterior (TA), and extensor digitorum longus muscle (EDL)), and quadriceps muscle (Qu). C Detection of EdU+ myonuclei in EDL (+Ex) or soleus (+Ex). Arrowheads indicate EdU+ nuclei (white) beneath dystrophin (green). Scale bar, 50 µm. D Number of EdU+ myonuclei per 100 myofibers: (−Ex)(black circle, n = 8 muscles; TA, EDL, GC, Qu, PLA, and soleus, n = 4 muscles; GM and Tri) versus (+Ex)(red circles, n = 8 muscles; TA, EDL, GC, Qu, PLA, and soleus, n = 4 muscles; GM and Tri). E Experimental design for analyzing MuSC behavior after 4 (both leg of n = 4) or 7 (both leg of n = 4) days exercise. F Immunostaining for Ki67 (green), Pax7 (red), and laminin (LN, white) in EDL (+Ex) or soleus (+Ex) after 7-days running. Arrows or arrowheads indicate Pax7+Ki67- or Pax7+Ki67+ cells, respectively. Scale bar, 10 µm. G Number of Ki67+ cells in Pax7+ MuSCs in indicated muscles after 4- or 7-days exercise. H Experimental design for evaluating the additional mechanical load on the EDL induced by TA tenotomy in both (+Ex) and (−Ex) mice. I Number of EdU⁺ myonuclei per 100 myofibers in EDL from (−Ex)(Sham; black circles, n = 4), (−Ex) tenotomized (Ope; black squares, n = 4), and (+Ex) tenotomized (Ope; red squares, n = 4). J Experimental design for investigating the effects of unloading on the soleus via cast immobilization (Cast (+)). The contralateral limb was left uncasted (Cast (−)). Four randomly selected soleus from Fig. 1D were analyzed as bilaterally cast-free controls (-Ex). K Number of EdU⁺ myonuclei per 100 myofibers in immobilized (−Ex Cast (+); blue circles, n = 4), contralateral mobilized (−Ex Cast (−); blue squares, n = 4), and bilaterally cast-free soleus (−Ex; black circles, n = 4). The graphs show individual data with mean ± s.d.; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (D) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (G, I, K). Note: In all panels, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue).

To further elucidate the role of mechanical loading in MuSC proliferation, the loading on EDL was increased by transecting the TA tendon (tenotomy) in both exercised and non-exercised mice (Fig. 1H). Although tenotomy alone did not significantly increase the number of EdU+ myonuclei, its combination with exercise resulted in a notable increase in the number of EdU+ MuSC-derived myonuclei (Fig. 1I and Fig. S3A). Next, we sought to reduce the load on the soleus during exercise by cast immobilization; however, the mice exhibited insufficient running activity. Therefore, we examined MuSC-derived myonuclei in the soleus of non-exercised mice (-Ex), where one limb was immobilized (Cast (+)) and the other was mobilized (Cast (−)) (Fig. 1J). Additionally, non-exercised (−Ex) mice with both soleus muscles free of casts (−) were analyzed. Importantly, a significant difference in the number of EdU+ myonuclei was observed among immobilized (Cast (+)), mobilized (Cast (−)), and cast-free (−) mice (Fig. 1K and Fig. S3B). In summary, these results suggest that MuSCs transition from a quiescent state to active proliferation in response to increased mechanical load during exercise. In contrast, MuSCs in non-increased-loading muscles, such as the EDL and TA muscles, remain quiescent even in exercising mice.

CalcR downregulation required for MuSC proliferation in running mice

CalcR is one of the most reliable markers for quiescent MuSCs25. Considering that CalcR expression is specific to the quiescent state, it is conceivable that the expression of CalcR in MuSCs differs between increased- and non-increased-loading muscles, as observed in surgically overloaded muscles27. In fact, the frequency of CalcR+ MuSCs was reduced in the soleus and PLA muscles, but not in the TA and EDL muscles, of the exercised mice (Fig. 2A, B, and Fig. S4). Notably, most CalcR- MuSCs were positive for Ki67, indicating an activated or proliferative state (Fig. 2B and Fig. S4). Moreover, CalcR-Ki67+ MuSCs were also detected in the EDL muscle of both tenotomized and exercised mice (Fig. 2C). These findings imply that the decreased expression of CalcR contributes to the divergent behavior of MuSCs in increased- and non-increased-loading muscles during exercise. To validate this hypothesis, transgenic mice (PKA-tg: Pax7CreERT2/+::PKA-tg) expressing the inducible catalytic subunit of PKA (PKAC[α]) were analyzed after wheel-running exercise (Fig. 2D), as PKA acts downstream of CalcR signaling to maintain MuSC quiescence23. The running distance during the two-week exercise period was similar between control and PKA-tg mice (Fig. 2E). However, inducible PKA remarkably suppressed the increased number of EdU+ myonuclei in the soleus and PLA muscles (Fig. 2F, G). Collectively, these results indicate that down-regulation of the CalcR-PKA signaling axis is essential for MuSC activation/proliferation and for the subsequent myonuclei accretion in increased-loading muscles during exercise.

A Immunostaining of calcitonin receptor (CalcR, green), Pax7 (red), and Ki67 (white) in EDL (+Ex) or soleus (+Ex) after seven days exercise. Arrows or arrowheads indicate Pax7+CalcR+Ki67- or Pax7+CalcR-Ki67+ cells, respectively. Scale bar, 50 µm. The reproducibility of the data was confirmed using four biological replicates. B Frequency of Ki67-CalcR- (blue), Ki67-CalcR+ (green), Ki67+CalcR- (red), or CalcR+Ki67+ MuSC (purple) in TA, EDL, PLA, and soleus after 4 (both leg of n = 4) or 7 (both leg of n = 4) days exercise (+Ex) or from sedentary mice (−Ex, both leg of n = 4). The graphs show individual data with mean ± s.d.; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. C Frequency of Ki67-CalcR- (blue), Ki67-CalcR+ (green), Ki67+CalcR− (red), or CalcR+Ki67+ MuSC (purple) in EDL from home cage (−Ex sham, n = 4), tenotomized and home cage (−Ex Ope, n = 4), and tenotomized and wheel-running group (+Ex Ope, n = 4). The graph shows individual data with mean ± s.d.; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. D Experimental design for analyzing MuSC behaviors in loaded soleus and PLA of control groups (PKA: PKA-tg, n = 4 or Pax7: Pax7CreERT2, n = 5), or Pax7-PKA mice (Pax7CreERT2::PKA-tg, n = 6) after 2 weeks of exercise. E Count of wheel rotations per night of PKA (Cont), Pax7 (Cont), or Pax7-PKA mice for 2 weeks. The graph shows individual data with mean ± s.d.; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. F Detection of EdU+ (white) nuclei beneath dystrophin (green) in soleus (+Ex) of wheel-running control (Pax7(+Ex)) or Pax7-PKA(+Ex) mice. Arrowheads indicate new myonuclei supplied by MuSCs. Scale bar: 50 µm. The reproducibility of the data was confirmed using more than four biological replicates. G Number of EdU+ myonuclei in soleus or PLA of PKA (Cont, n = 4), Pax7 (Cont, n = 5), or Pax7-PKA (n = 6) mice. The graphs show individual data with mean ± s.d.; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

CalcR loss induces MuSC proliferation in TA and EDL in running mice

MuSC proliferation is typically restricted to injured or mechanically increased-loading muscles20. However, given that exercise exerts systemic effects through circulating factors, it is plausible that these factors can access MuSCs in the whole muscle, including non-loaded muscles. This notion is supported by the rejuvenating effects of young blood on aged MuSCs31 and the finding of Galert MuSCs32. In addition, serum from wheel-running mice was reported to improve the activation of aged MuSCs in the EDL muscle, a non-increased-loading muscle33. Consistent with our observations, wheel-running exercise did not significantly affect MuSCs in the EDL of young mice. However, the role of quiescent signaling in the context of systemic factors remains unknown. We hypothesized that the CalcR-PKA pathway represents a potential quiescent signaling that counteracts the impact of systemic factors. To validate this hypothesis, we analyzed MuSCs in the EDL and TA muscles of Calcr mutant mice (C-cKO, Pax7CreERT2::Calcrflox/flox::Rosayfp/yfp or +) (Fig. 3A). These muscles were selected due to their common use in muscle research and their lack of an increased number of MuSC-derived myonuclei following wheel-running (Fig. 1D).

A Experimental scheme for analyzing MuSC behavior in EDL and TA in exercised control (+Ex) (Cont; Pax7CreERT2::Rosayfp/yfp, n = 3), exercised C-cKO (+Ex) (Pax7CreERT2::Calcrflox/flox::Rosayfp/yfp, n = 5), or non-exercised C-cKO (−Ex) (n = 3) using immunohistochemistry (IHC). B Count of wheel rotations per night of Cont (n = 3) or C-cKO (n = 5) mice for 2 weeks-exercise with mean ± s.d.; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. C Verification of EdU+ myonuclei (white) located beneath dystrophin (green) in EDL of C-cKO (−Ex) and (+Ex). Arrowheads indicate EdU+ myonuclei in EDL of C-cKO (+Ex) mice. Scale bar, 50 µm. D Number of EdU+ myonuclei in EDL or TA in Cont (+Ex, n = 3), C-cKO (−Ex, n = 3), or C-cKO (+Ex, n = 5) mice. E Immunostaining for LNα2 (green), M-cadherin (red), and EdU (white) in EDL from C-cKO (+Ex) mice. Scale bar, 10 µm. F Number of EdU+M-cadherin+ MuSCs in EDL or TA in Cont (+Ex, n = 3), C-cKO (−Ex, n = 3), or C-cKO (+Ex, n = 5) mice. G Experimental scheme for analyzing MuSC number on isolated single myofibers (SMF) from EDL of exercised Cont (n = 5), C-cKO (n = 8), C-cKO/PKA (Pax7CreERT2::Calcrflox/flox::PKA-tg::Rosayfp/yfp, n = 4), or C/Y-cdKO (Pax7CreERT2::Calcrflox/flox::Yap1flox/flox::Rosayfp/yfp, n = 7) (+Ex) after 2 weeks of exercise. SMF of non-exercised Cont (n = 4), C-cKO (n = 7), C-cKO/PKA (n = 3), and C/Y-cdKO (n = 4) (−Ex) mice were also analyzed. H Count of wheel rotations per night of Cont, C-cKO, C-cKO/PKA, or C/Y-cdKO for 2 weeks of exercise. I Detection of YFP+Pax7+ MuSCs on isolated myofibers from C-cKO (−Ex) or (+Ex). Arrowheads indicate YFP+Pax7+ cells. Scale bar, 50 µm. J Number of MuSCs per single myofiber from EDL of Cont (−Ex, n = 4), Cont (+Ex, n = 5), C-cKO (−Ex, n = 7), or C-cKO (+Ex, n = 8) mice. K Frequency of myofiber harboring >10 MuSCs on one myofiber in (J). L Number of MuSCs per single myofiber from C-cKO/PKA (−Ex, n = 3), C-cKO/PKA (+Ex, n = 4), C/Y-cdKO (−Ex, n = 4), or C/Y-cdKO (+Ex, n = 7) mice. M Percentage of myofiber harboring >10 MuSCs on one myofiber in (L). The graphs show individual data with mean ± s.d.; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (D, F, H, J–M). The reproducibility of the data was confirmed using more than three biological replicates (C, E, I).

We first confirmed that the physical activity levels of the C-cKO mice were comparable to those of control mice (Cont, Pax7CreERT2::Calcrflox/flox::Rosayfp/yfp or +) (Fig. 3B). In control (+Ex) and non-exercised C-cKO (-Ex) mice, EdU+ myonuclei were rarely detected in the EDL and TA muscles. However, exercised C-cKO (+Ex) mice exhibited a significant increased number of EdU+ myonuclei in both muscles (Fig. 3C, D). The observed ‘0.8’ EdU+ myonuclei per 100 myofibers (Fig. 3D) in C-cKO (+Ex) corresponds to approximately 30–40% of the MuSC population in C-cKO mice 2 weeks after tamoxifen injection22, indicating a substantial biological phenomenon.

To further verify the proliferation of C-cKO MuSCs in the EDL and TA muscles in response to exercise, we performed immunostaining for M-cadherin and EdU. EdU+M-cadherin+ cells were detected in neither control (+Ex) nor C-cKO (-Ex) mice (Fig. 3F). In contrast, a substantial number of EdU+M-cadherin+ MuSCs were observed in C-cKO (+Ex) mice (Fig. 3E, F, and Fig. S5). These findings indicate that the loss of CalcR enables MuSCs to proliferate in response to exercise stimuli, independent of mechanical load, and that the proliferated MuSC population subsequently fuses with myofibers, as shown in Fig. 3C.

To further validate MuSC proliferation in the non-increased-loading muscle of exercised C-cKO mice, we quantified the number of MuSCs on single myofibers isolated from the EDL muscles (Fig. 3G). The physical activity levels of C-cKO mice were comparable to those of the control mice (Fig. 3H), and exercise did not affect the number of MuSCs in control mice (Fig. 3J). Although the number of MuSCs in non-exercised C-cKO (-Ex) mice was lower than that in control (-Ex) mice, it significantly increased following exercise (+Ex) (Fig. 3I, J). Moreover, the frequency of myofibers containing more than 10 MuSCs significantly increased in exercised C-cKO (+Ex) mice (Fig. 3K), whereas no such changes were observed in control mice (Fig. 3J, K). These findings further support that MuSCs in C-cKO mice undergo exercise-induced proliferation in the EDL muscle, independent of increased loading.

To investigate the role of CalcR downstream signaling in MuSC proliferation in non-increased-loading muscles of exercising mice, we used C-cKO/PKA (Pax7CreERT2:: Calcrflox/flox::PKA-tg::Rosayfp/yfp) and C/Y-cdKO (Pax7CreERT2:: Calcrflox/flox::Yap1flox/flox::Rosayfp/yfp) mice23. Following the same experimental protocol as in the C-cKO studies, mice were housed in either standard cages or wheel-running cages for 2 weeks (Fig. 3G). The physical activity levels of C-cKO/PKA and C/Y-cdKO mice were comparable to those of control mice (Fig. 3H). However, wheel-running exercise did not increase the number of MuSCs in the EDL muscles of C-cKO/PKA or C/Y-cdKO mice (Fig. 3L, M). These results suggest that the CalcR/PKA/Yap1 axis is a signaling pathway that maintains MuSC quiescence in exercised mice by counteracting the effects of exercise-dependent circulating factors.

Gp130 drives MuSC proliferation in C-cKO non-increased-loading muscles

Skeletal muscles subjected to mechanical loading during exercise release various signaling molecules, including interleukin (IL)−6 and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF)34. IL-6, the most well-characterized exerkine35, has been implicated in the regulation of MuSC proliferation. Independent studies have demonstrated that IL-6 contributes to the local expansion of MuSCs in vivo in response to surgically overloaded36,37. Additionally, elevated serum IL-6 levels have been reported in wheel-running mice4. Similarly, LIF has been proposed as a candidate exerkine as its mRNA expression is rapidly upregulated in human muscles following exercise38,39. LIF-null mice exhibit impaired muscle hypertrophy in response to high-loaded resistance training, an effect that can be rescued by exogenous LIF administration40. Furthermore, LIF has been shown to enhance the proliferation of both human and murine myogenic cells41,42. These findings suggest that IL-6 family cytokines may induce MuSC proliferation in exercised C-cKO mice. To assess the involvement of IL-6 family signaling in C-cKO MuSCs, the common receptor of the IL-6 family, gp130, was depleted in C-cKO MuSCs (C/130-cdKO) (Fig. 4A). The physical activity levels of C/130-cdKO mice were comparable to those of C-cKO mice (Fig. 4B). However, exercised C/130-cdKO (+Ex) mice exhibited a significantly reduced number of MuSCs in the EDL compared to exercised C-cKO (+Ex) mice, with no significant difference observed in non-exercised C/130-cdKO (-Ex) mice (Fig. 4C–E). Additionally, the numbers of MuSC-derived myonuclei and EdU+M-cadherin+ MuSCs in C/130-cdKO mice were not dramatically increased by exercise and were significantly lower than those observed in C-cKO (+Ex) mice (Fig. 4F–J, Fig. S6). These findings indicate that gp130-dependent signaling is essential for the proliferation of MuSCs in non-increased-loading muscles (EDL and TA) of exercised C-cKO mice.

A Experimental scheme for analyses of MuSC behaviors on isolated single myofiber (SMF) from EDL of C-cKO or C/130-cdKO (Pax7CreERT2:: Calcrflox/flox::gp130flox/flox::Rosayfp/yfp) mice, subjected to exercise (+Ex, C-cKO; n = 4, C/130-cdKO; n = 7) or no exercise (−Ex, C/130-cdKO, n = 5). B The graph shows individual data of count of wheel rotations per night of C-cKO (n = 4) or C/130-cdKO (n = 7) mice during 2 weeks exercise. C Detection of YFP+Pax7+ MuSCs on freshly isolated myofibers from exercised C-cKO (+Ex) or C/130-cdKO (+Ex). Arrowheads indicate YFP+ cells. Scale bar, 100 µm. D The graph shows individual data of MuSC number per single myofiber from EDL of C-cKO (+Ex, n = 4), C/130-cdKO (−Ex, n = 5), or C/130-cdKO (+Ex, n = 7) mice. E Frequency of myofibers harboring > 10 MuSCs on one myofiber in (D). F Experimental design for analyses of MuSC behaviors in EDL and TA in C/130-cdKO mice, subjected to exercise (+Ex, n = 7) or no exercise (−Ex, n = 5) by immunohistochemistry (IHC). G Detection of EdU+ myonuclei in EDL of C/130-cdKO mice. MuSC-derived new myonuclei were identified as EdU+ nuclei (white) beneath dystrophin (green). Arrows or arrowheads indicate EdU+ non- or EdU+ myonuclei, respectively. Scale bar, 50 µm. H The graph shows individual data of EdU+ myonuclei number in EDL or TA in C/130-cdKO (−Ex, n = 5) or C/130-cdKO (+Ex, n = 7) mice. Dotted lines represent the results of C-cKO mice. I Immunostaining for LNα2 (green), M-cadherin (red), and EdU (white) of EDL from C-cKO (+Ex), C/130-cdKO (−Ex), or C/130-cdKO (+Ex) mice. Arrows or arrowheads indicate EdU-M-cadherin+ or EdU+M-cadherin+ cells, respectively. Scale bar, 20 µm. J The graph shows individual data of EdU+M-cadherin+ cells number in EDL or TA from C/130-cdKO (−Ex, n = 5) or C/130-cdKO (+Ex, n = 7) mice. Statistical calculations for (H) and (J) were performed using the C-cKO (+Ex) values in Fig3D and 3F. The graphs show individual data with mean ± s.d.; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (B, H, J) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (D, E). The reproducibility of the data was confirmed using more than three biological replicates (C, G, I).

Exercise circulating factors drive systemic MuSC proliferation in C-cKO

To evaluate the direct impacts of circulating exerkines on the loading-independent MuSC proliferation in C-cKO mice, we injected serum from exercised mice into sedentary C-cKO mice and analyzed MuSC behaviors using isolated myofibers or tissue sections (Fig. 5A). Compared to C-cKO mice treated with serum from non-exercised mice (-Ex-serum), those receiving serum from exercised mice (+Ex-serum) showed a significant increase in MuSC numbers on isolated myofibers (Fig. 5B, C), although no myofibers harbored more than 10 MuSCs. Similarly, +Ex-serum transfer significantly increased the number of MuSC-derived EdU+ myonuclei and EdU+M-cadherin+ MuSCs in all the analyzed muscle of sedentary C-cKO mice (Fig. 5D–G, Fig. S7A). In the TA muscle, C-cKO (+Ex) mice exhibited approximately 0.8 EdU+ MuSC-derived myonuclei and 0.3 EdU+M-cadherin+ MuSCs per 100 myofibers after 2 weeks of wheel-running (Fig. 3D, F). While, serum-transferred sedentary C-cKO mice showed approximately 0.3 EdU+ MuSC-derived myonuclei (Fig. 5E) and 0.2 EdU+M-cadherin+ cells (Fig. 5G) during one week of serum treatment. Considering the shorter exposure period of serum transfer experiments, these findings suggest that exercise-induced factors exert a robust stimulatory effect on MuSC proliferation in the absence of CalcR signaling. Collectively, these results indicate that circulating exercise-dependent factors can systemically induce C-cKO MuSC proliferation.

A Experimental scheme for analyses of MuSC behaviors by isolated single myofiber (SMF; B, C) of EDL or immunohistochemistry (IHC; D-G) of TA, GM, Tri, GC, and Qu from C-cKO (Pax7CreERT2:: Calcrflox/flox::Rosayfp/yfp) mice transferred with exercised serum (+Ex-serum, n = 7) or non-exercised serum (−Ex-serum, n = 4). B Detection of YFP+Pax7+ MuSCs on freshly isolated myofibers from C-cKO mice with +Ex-serum or −Ex-serum. Arrowheads indicate YFP+Pax7+ cells. Scale bar, 50 µm. C Number of MuSCs per single myofiber from EDL of C-cKO mice with −Ex- (n = 4) or +Ex-serum (n = 7). D Detection of EdU+ myonuclei in GM and Tri of C-cKO mice transferred with +Ex-serum. Arrowheads indicated EdU+ nuclei (white) beneath dystrophin (green). Scale bar, 20 µm. E Number of EdU+ myonuclei in TA, GM, Tri, GC, and Qu in C-cKO mice transferred with −Ex- (n = 4) or +Ex-serum (n = 7). F Immunostaining for LNα2 (green), M-cadherin (red), and EdU (white) of GM and Tri muscles from C-cKO mice transferred with +Ex-serum. Arrowheads indicate EdU+M-cadherin+ cells. Scale bar, 20 µm. G Number of EdU+M-cadherin+ cells in TA, GM, Tri, GC, and Qu in C-cKO mice transferred with −Ex- (n = 4) or +Ex-serum (n = 7). The graphs show individual data with mean ± s.d.; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (C, E, G). The reproducibility of the data was confirmed using more than four biological replicates (B, D, F).

Blocking IL-6 attenuates exercised-serum effects on C-cKO MuSCs

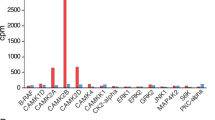

To identify the serum factor acting through gp130, we first quantified the levels of IL-6 and LIF in serum after exercise (Fig. 6A). In the wheel-running mice, IL-6 levels were remarkably elevated compared to both non-exercised and treadmill-running mice. We also observed that LIF levels showed a modest increase relative to sedentary mice, but were comparable to those in the treadmill-running group (Fig. 6A). In contrast, neither IL-6 nor LIF levels were significantly elevated in the treadmill-running model (Fig. 6A). In addition, serum from treadmill-running mice did not increase the number of EdU⁺ myonuclei (Fig. S7B). We therefore examined the effect of IL-6 in serum from wheel running mice on C-cKO MuSCs using an anti-IL-6 antibody (Fig. 6B). Compared to control IgG-treated mice, the number of MuSCs on EDL-derived myofibers from C-cKO (+Ex-serum) mice treated with anti-IL-6 antibody was significantly reduced (Fig. 6C, D). The numbers of EdU⁺ myonuclei and EdU⁺M-cadherin⁺ cells were also decreased in anti-IL-6 antibody-treated C-cKO (+Ex-serum) mice compared with controls (Fig. 6E–H and Fig. S8).

A Protein concentration of LIF and IL-6 in blood of non-exercised (−Ex, n = 4), treadmill running (+Ex, n = 3), or wheel-running (+Ex, n = 4) mice. B Experimental design for analyzing MuSC behaviors of indicated muscles in C-cKO (+Ex-serum) mice treated with either control or anti-IL-6 antibodies using isolated single myofibers (SMF; C, D) from the EDL or immunohistochemistry (IHC; E–H). C Detection of YFP+Pax7+ MuSCs on freshly isolated EDL myofibers from C-cKO (+Ex-serum) mice treated with either control or anti-IL-6 antibodies. Arrowheads indicate YFP+Pax7+ cells. D Number of MuSCs per single myofiber from EDL of C-cKO (+Ex-serum) with control or anti-IL-6 antibodies. E Detection of EdU+ myonuclei in GM and Tri of C-cKO mice treated with control IgG. F Number of EdU+ myonuclei in indicated muscles in cKO (+Ex-serum) with control (n = 5) or anti-IL-6 (n = 5) antibodies. G Immunostaining for M-cadherin (red) and EdU (white) of GM and Tri from C-cKO (+Ex-serum) with control or anti-IL-6 antibodies. H Number of EdU+M-cadherin+ cells in indicated muscles in the cKO (+Ex-serum) mice treated with control (n = 5) or anti-IL-6 (n = 5) antibodies. I Experimental design for analyzing MuSC behaviors of indicated muscles in (−Ex) Cont or C-cKO with or without IL-6 using immunohistochemistry (IHC; J–M). J Detection of EdU+ myonuclei (Dystrophin; green, EdU; white) in Tri of C-cKO mice treated with IL-6 (2 ng/mL). Arrowheads indicate EdU+ myonuclei. K Number of EdU+ myonuclei in indicated muscles in Cont (−Ex)(2 ng/mL, n = 6) or cKO (−Ex)(0; n = 5, 1; n = 4, 2 ng/mL; n = 6). L Immunostaining for M-cadherin (red), LNα2 (green), and EdU (white) of GC muscle from cKO (−Ex) with IL-6 (2 ng/mL). Arrowheads indicate EdU+M-cadherin+ cells. M Number of EdU+M-cadherin+ cells in indicated muscles in Cont (−Ex)(2 ng/mL, n = 6) or cKO (−Ex)(0; n = 5, 1; n = 4, 2 ng/mL; n = 6). The graphs show individual data with mean ± s.d.; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. (D, F, H) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (A, K, M). The reproducibility of the data was confirmed using more than four biological replicates (C, E, G, J, L). Scale bar, 20 µm (E, G), 50 µm (C, J, L).

To further examine the involvement of IL-6 in C-cKO MuSC proliferation, sedentary control and C-cKO mice were treated with -Ex-serum containing IL-6 (Fig. 6I). Consistent with the results obtained thus far, administration of IL-6 increased the number of EdU⁺ myonuclei and EdU⁺M-cadherin⁺ cells only in sedentary C-cKO (-Ex) mice (Fig. 6J–M and Fig. S9). Collectively, these results indicate that IL-6 is the key factor driving the proliferation of C-cKO MuSCs in an exerkine-dependent manner.

Cross-talk between CalcR and IL-6 signaling

To elucidate the mechanism underlying the proliferation of C-cKO MuSCs by IL-6 in non-increased-loading muscles during exercise, we focused on key downstream effectors of IL-6 signaling. STAT3 is a well-established mediator of IL-6 signaling. Consistent with a previous report, activated STAT3 (p-STAT3: phosphorylated STAT3) was detected in proliferating MuSC in vitro (Fig. 7A)43. However, p-STAT3-positive MuSCs were absent in the EDL muscles of C-cKO (+Ex)(Fig. 7A), suggesting that IL-6-mediated STAT3 activation does not contribute to MuSC proliferation under these conditions.

A Immunostaining for Pax7 (red) and phosphorylated STAT3 (p-STAT3, green) in MuSCs on freshly isolated EDL myofibers from (+Ex) C-cKO mice. Cultured myofibers (2-day cultured) were used as a positive control for p-STAT3 staining. Scale bar, 50 µm. The reproducibility of the data was confirmed using more than three biological replicates. B Immunostaining for Yap1 (red) and Pax7 (white) in MuSCs on freshly isolated EDL myofibers from (+Ex) Cont, (−Ex) C-cKO, (+Ex) C-cKO, or (+Ex) C/130-cdKO mice. Scale bar, 50 µm. The reproducibility of the data was confirmed using more than three biological replicates. C Quantification of Yap1 expression (frequency or intensity) in MuSCs on freshly isolated EDL myofibers of (+Ex) Cont (n = 3), (−Ex) C-cKO (n = 3), or (+Ex) C-cKO (n = 3) mice. The graphs show individual data with mean ± s.d.; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. The comparison between (+Ex) C-cKO (n = 4) and (+Ex) C/130-cdKO (n = 5) was conducted as a completely independent experiment from the three-group comparison. The graphs show individual data with mean ± s.d.; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. D Western blotting analysis of total Yap1 in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of CalcR-expressing C2C12 treated with 10% FCS, IL-6 (100 pg/ml), or elcatonin (EL; 0.1 U/mL). β-Tubulin and Lamin A/C were served as markers for cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, respectively. Uncropped blots in Source Data. E Quantification of Yap1 protein levels in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions shown in (D), normalized to β-Tubulin or Lamin A/C protein levels. Four independent experiments were performed. F Western blotting analysis of phosphorylated Yap1 (P-Yap1) at Ser127, Tyr357, Ser397, or total Yap1 in CalcR-expressing C2C12 treated with 10% FCS, IL-6 (100 pg/ml), or elcatonin (EL; 0.1 U/mL). Uncropped blots in Source Data. G Quantification of each P-Yap1 protein levels in (F), normalized to total Yap1 levels. Four independent experiments were performed. The graphs show individual data with mean ± s.d.; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (E, G).

We next examined Yap1, given that the loss of CalcR permits its nuclear accumulation (activation), and gp130 signaling can activate Yap1 independently of STAT344. Consistent with our previous findings, nuclear Yap1 localization was elevated in C-cKO MuSCs under sedentary conditions (−Ex) (Fig. 7B, C). Notably, compared with control (+Ex) and C-cKO (-Ex), both the frequency of Yap1-positive nuclei and the intensity of nuclear Yap1 signal were significantly increased in C-cKO (+Ex) MuSCs, whereas they were reduced in C/130-cKO (+Ex) (Fig. 7B, C). These results suggest that the further increased accumulation of nuclear Yap1 is involved in the proliferation of C-cKO MuSCs by exerkines.

To further explore the relationship between CalcR signaling, Yap1, and IL-6, we assessed whether IL-6 induces Yap1 nuclear translocation in C2C12 expressing CalcR (C2C12-CalcR). Under serum-starved conditions, Yap1 was predominantly localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 7D). However, IL-6 stimulation promoted nuclear translocation of Yap1, comparable to the effect of FCS (positive control)(Fig. 7D, E). Importantly, pretreatment with a CalcR ligand significantly suppressed IL-6-induced nuclear accumulation of Yap1 (Fig. 7D, E).

Phosphorylation of Yap1 at Ser127, which promotes its cytoplasmic retention45, is induced by CalcR signaling23. In contrast, phosphorylation of Yap1 at Tyr35744 facilitates its nuclear localization46. To investigate the interplay between CalcR and IL-6 signaling, we analyzed their effects on these phosphorylation events. Similar to FCS, IL-6 suppressed Ser127 phosphorylation in serum-starved C2C12-CalcR cells; however, pretreatment with the CalcR ligand abrogated this effect and sustained Ser127 phosphorylation (Fig. 7F, G). Conversely, IL-6 enhanced Tyr357 phosphorylation, whereas CalcR signaling inhibited this modification (Fig. 7F, G). Consistent with our previous findings, phosphorylation at Ser397, which targets Yap1 for degradation45, was not affected by either CalcR or IL-6 signaling. Collectively, these in vivo and in vitro findings suggest that CalcR signaling acts as a protective mechanism against exercise-induced IL-6 signaling by inhibiting IL-6–mediated Yap1 activation.

Discussion

In the field of muscle stem cell (MuSC) research, a long-standing question is how the behavior of MuSCs is regulated by various types of muscle contractions. Myofibers contract and relax randomly, even in sedentary mice, where MuSCs remain quiescent. However, when skeletal muscles experience loading exceeding a certain threshold, MuSCs become activated and enter a proliferative state47. A prevailing hypothesis posits that intense muscle contractions induce myofiber damage, thereby inducing MuSC proliferation, as typically observed in regenerating muscles. In such regenerative contexts, damaged myofibers, alongside factors derived from macrophages or mesenchymal progenitors, promote MuSC activation and proliferation48,49,50,51. Nevertheless, experimental evidence suggests that MuSCs can proliferate in overloaded muscles under conditions of minimal or no overt signs of myofiber damage12,15. Notably, robust MuSC proliferation has been observed in hypertrophic models without significant myofiber death, as evidenced by clusters of proliferating MuSCs on living myofibers15. However, these models do not fully exclude the contribution of exercise-induced localized muscle damage. To conclusively demonstrate injury-independent MuSC proliferation and differentiation, it is essential to recapitulate these processes in sedentary conditions by regulating exercise-altered signaling pathways. Here, we demonstrated MuSC proliferation and differentiation - evidenced by MuSC-derived EdU+ myonuclei - in non-increased-loading muscles of wheel-running C-cKO mice. Additionally, both serum from exercised mice and administration of IL-6 successfully recapitulated MuSC proliferation and increased the number of MuSC-derived myonuclei in sedentary C-cKO mice. Considering the decreased expression of CalcR and elevated serum IL-6 levels in the absence of overt muscle regeneration, we propose the concept of ‘non-regenerative myogenesis’, defined as injury-independent MuSC proliferation and differentiation, as a primary mechanism driving MuSC proliferation and subsequent myonuclear accretion in response to mechanical loading. Further investigation of this process will deepen our understanding of muscle adaptation and inform therapeutic strategies for treating injury-unrelated muscle atrophy.

A fundamental physiological question is why some MuSCs proliferate while others remain quiescent, depending on their location within or across muscles. Our findings demonstrate that reduced CalcR expression contributes to divergent proliferative responses of MuSCs during exercise. Furthermore, our results suggest exercise load intensity influences CalcR expression in MuSCs. Given that exercise also alters signaling pathways in myofibers, including those related to metabolism, it is plausible that both direct mechanical loading and indirect paracrine effects regulate CalcR expression. Elucidating these regulatory mechanisms governing CalcR expression will enhance our understanding of exercise-induced muscle adaptation and define the mechanical loading threshold of triggering MuSC proliferation.

Our previous study provides evidence for the indispensable role of interstitial PDGFRα+ mesenchymal progenitors in promoting MuSC proliferation in surgically overloaded muscles27. While the roles of mesenchymal progenitors in exercise-dependent muscle loading are under investigation, a recent study highlights the pivotal role of PDGFRα+ cells as a primary source of secreted factors in the bloodstream in a running exercise model52, suggesting their activation and functional importance in both running and resistance training models.

CalcR is a GPCR that plays a pivotal role in diverse physiological processes, including bone formation, thermoregulation, feeding, and cardiac fibrosis53,54,55,56. In MuSCs, CalcR expression is restricted to the quiescent state and inversely correlates with MuSC activation and proliferation during development, regeneration, and hypertrophy22,25,27. Brett et al. reported that exercise-dependent systemic factors rejuvenate aged MuSCs via Cyclin D1 in EDL muscles, noting a more modest effect on young MuSCs compared to aged counterparts33. Although the systemic factors mediting this rejuvenating remain unidentified, IL-6 is a potential candidate, as IL-6 deficiency reduces Cyclin D1 mRNA expression in overloaded muscle36 and during liver regeneration57. Furthermore, age-associated downregulation of CalcR expression in MuSCs may contribute to the differential responses between young and aged MuSCs26.

Most IL-6 family members activate the JAK/STAT3, Ras/MAPK, and PI3K/Akt/mTORC pathways58,59. In addition, gp130 signaling activates Yap1 post-translation44. Our findings provide the first evidence of cross-talk between GPCR and gp130 signaling pathways. Furthermore, our data suggest that nuclear Yap1 protein levels may serve as a determinant or modulatory factor for MuSC proliferation. Finally, we propose that CalcR suppression and gp130 activation represent the minimal pathways required to induce MuSC proliferation.

Contralateral injury induces MuSCs to transition from quiescence to a moderately activated state termed “Galert”32. Mechanistically, injury activates HGFA, a systemic protease that triggers HGF activation, leading to mTORC1 activation via c-Met (the HGF receptor)60. The present study demonstrated that systemic factors induced by running exercise access MuSCs, resulting in the proliferation of MuSCs lacking CalcR signaling. Expansion of MuSCs can be achieved by modulating CalcR and gp130 signaling, similar to the regulation observed between CalcR and CD47 signaling in mechanical overloaded muscles27. Comprehensive analyses of MuSC dynamics under various physiological conditions, such as regeneration, exercise, and hypertrophy, will advance strategies to enhance muscle regeneration, improve gene delivery efficiency to MuSCs, and mitigate muscle atrophy in muscular disorders.

In conclusion, our study showed that exercise has the capacity to induce systemic MuSC proliferation through gp130 activation. However, CalcR signaling exerts inhibitory effects on this process. Although sedentary mice have been used in most studies, even in pathways that lack a robust phenotype under sedentary conditions, practicing physical exercise may reveal novel aspects of MuSC regulation.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 J mice were obtained from Charles River (Japan). Inducible Calcr knockout mice and the inducible PKA-Cα subunit transgenic mice (PKA-tg mice)61 were previously generated and described22,62. Pax7CreERT2+ (Stock No 012476) and Yap1-floxed mice (Stock No 027929) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). The relocation of Rosa26EYFP/+ mice (Stock No: 006148) from the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry to Osaka University was approved by the Jackson Laboratory. Gp130-floxed mice63 were kindly provided by Professor Werner Müller (University of Manchester, UK). These mice were crossed to generate conditional knockout mice.

For conditional depletion of the targeted genes, mice were injected intraperitoneally twice (24 h apart) with 200–300 µL tamoxifen (20 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich #T5648) dissolved in sunflower seed oil (Sigma-Aldrich #S5007) and 5% ethanol. The mice were housed in a controlled environment with a temperature of 24 ± 2 °C and humidity of 50% ± 10% under a 12-h light/dark cycle. Mice were provided standard sterilized food (DC-8; Nihon Clea, Tokyo, Japan) and ad libitum access to water. All experimental animal procedures were approved by the Experimental Animal Care and Use Committee of Osaka University (approval numbers: Douyaku 30-15, R02-3-10, R07-1).

Voluntary wheel-running exercise

All mice were housed in environmentally controlled facilities, maintained at a temperature of 24 ± 2 °C and a humidity level of 50 ± 10%, on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle, and had free access to water and food. Two weeks after tamoxifen injection, the mice were individually housed in cages (225 [width] × 345 [depth] × 210 mm [height]). The cages were equipped with running wheels (140 mm in diameter; MELQUEST, Toyama, Japan), enabling the mice to participate in voluntary running activities for a specified duration. The count of rotations was determined using a CNT-10 device (MELQUEST). Mice with more than 10,000 rotations over a 2-week period were used. Mice in the non-exercise group were housed in cages of the same size, but without running wheels.

Increased or decreased mechanical load by tenotomy or castration

Under anesthesia, a midline incision was made in the hindlimbs, and the distal tendons of the tibialis anterior (TA) muscles were transected (tenotomy). Because the EDL muscles are not high-load muscles in daily exercise, we transected the distal half of the TA muscle (TA tenotomy). The incision was then sutured with a 6-0 nylon suture with a needle (Natusme-Seisakusho, Tokyo, Japan). For the sham-operated group, similar incisions were made, but TA tenotomy was not performed. To overload the EDL muscle more strongly, the mice were subjected to wheel-running training for a week after TA tenotomy on both legs. Extensor digitorum longus (ELD) muscles were harvested 7 days after tenotomy.

To reduce mechanical loading, one hindlimb was immobilized in a plantar-flexed position (ankle extension causing the foot to point downward and away from the leg) using casting tape (3 M, 82002-J). The contralateral hindlimb remained non-immobilized. Seven days after the cast, soleus muscles were isolated and fixed.

Administration of IL-6 antibody

To inhibit IL-6 activity, C-cKO mice (day 0) implanted with capsules containing exercised serum received five intraperitoneal injections of anti-IL-6 antibodies (Selleck, clone MP5-20F3; Rat IgG1, κ, 200 µg/head) administered on day -1 (one day prior to implantation) and on days 0, 1, 3, and 5 post-implantation. Control mice received isotype-matched control antibodies (Selleck, clone HRPN; Rat IgG1, 200 µg/head) on the same schedule. Skeletal muscles were harvested on day 7 post-implantation.

Fixation of muscle

Plantaris (PLA), soleus, gastrocnemius (GC), quadriceps (Qu), tibialis anterior (TA), extensor digitorum longus (EDL), gluteus maximus (GM), and triceps (Tri) muscles were isolated and rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen-chilled 2-methylbutane for one minute with agitation (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan). Subsequently, the muscle samples were placed on dry ice for 1 h to vaporize 2-methylbutane and then preserved in closed containers at -80 °C freezer64.

Staining of isolated single myofibers

Single myofibers were isolated from the EDL muscles using 0.5% collagenase type I (Worthington Biochemical Corp)65. Subsequently, the isolated myofibers were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA). After washing with PBS, the myofibers were permeabilized using a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 300 mM sucrose, 50 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, and 0.5% Triton X-100 in distilled water66. After blocking with PBS containing 5% FCS and 0.01% Triton, the myofibers were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against anti-Pax7 (clone; Pax7, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, x2, ThermoFisher #PA1-117, x200), YFP (SICGEN, #AB0020-200, x1000), phosphorylated-STAT3 (Tyr705, Cell Signaling Technology #9145, x200), Yap1 (Abnove # H00010413-M01, x200), or Yap/Taz (Cell signaling #8418, x200). The following day, the myofibers were rinsed with PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies. Fluorescence was recorded using a BZ-X700 fluorescence microscope (Keyence, Osaka, Japan). For quantitative analysis, more than 30 myofibers per mouse were analyzed.

EdU labeling in vivo and detection

EdU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine; Thermo Fisher Scientific, #A10044) was dissolved in sterilized PBS (Nacalai tesque, Osaka, Japan) at a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL and stored at -20 °C. For the experiments illustrated in Fig. 1 (H and J), 5, and 6, the EdU stock solution was diluted in PBS to a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. This diluted solution was then injected intraperitoneally into mice at a dose of 5 mg/kg body weight daily until the day before euthanasia.

In other experiments, an Alzet mini-osmotic pump (Model 2002, Durect, Cupertino, CA, http://www.durect.com/)67 was used to continuously administer EdU during wheel-running or under control conditions within the home cage for 14 days. These pumps were filled with 200 µL of EdU solution in PBS at a concentration of 10 mg/mL, resulting in a delivery rate of 0.5 µL/h, equivalent to 120 µg of EdU per day. Click-iTTM EdU Alexa FluorTM 647 Cell Proliferation Kit for imaging (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #C10340) was utilized for the detection of EdU+ nuclei. Fluorescence was recorded using a BZ-X700 fluorescence microscope (Keyence), and cell size was quantified using hybrid cell count software (Keyence). For quantitative analysis, EdU+ myonuclei and EdU+M-cadherin+ cells were observed across sections.

Preparation of serum from exercised mice

After the wheel-running exercise for 7 days, exercised and nonexercised mice were anesthetized using a medetomidine, midazolam, and butorphanol cocktail at the end of the dark period of the morning. Blood samples were taken from the subclavian vein and mice were euthanized using the approved protocols. Serum samples were collected by centrifugation. A portion of the serum was used to detect the IL-6 and LIF concentration. The remaining serum was pooled and concentrated approximately twofold using an Ultracel-3 regenerated cellulose membrane (15 mL sample volume; Merck, UFC900308). An Alzet mini-osmotic pump (Model 2001) was used for the serum transfer experiments. These pumps were filled with 200 µL of concentrated serum (concentration of IL-6; 80-100 pg/mL), resulting in a delivery rate of 1 µL/h, equivalent to approximately 100 µL of blood per day.

For treadmill exercise, mice were acclimated to treadmill running over a 5-day period. On Day 1, they ran at a speed of 10 m/min for 5 minutes. From Day 2 to Day 5, the running speed was progressively increased by 2 m/min per day, reaching 18 m/min. On Day 6, the mice exercised at 20 m/min until exhaustion, after which blood samples were collected using the same procedure as for the wheel-running group. The concentration of IL-6 utilized for experiments was 10-20 pg/mL.

IL-6 Administration

Recombinant murine IL-6 (1 or 2 ng; PeproTech, PEP-216-16-10UG) was added in 1 mL of serum obtained from non-exercised (-Ex) mice. An Alzet mini-osmotic pump (Model 2001), prefilled with 200 µL of -Ex serum with or without IL-6, was implanted under anesthesia.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistological analyses, transverse cryosections (6–8 µm) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. After blocking with a MOM kit (Vector Laboratories, #BMK-2202), the sections were reacted with anti-Pax7 (clone; Pax7, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, x2), anti-laminin α2 (clone; 4H8-2, Enzo, #ALX-804-190-C100, x200), anti-EHS-laminin (Cosmo Bio, #LB-1013, x1000), anti-CalcR (Bio-Rad, #AHP635, x200), anti-Ki67 (Clone; SolA15, Thermo Fisher Scientific, #14-5698-82, x200), anti-M-cadherin (R&D, #AF4096, x200), or anti-dystrophin (Abcam, #AB15277 x800) antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After incubation with primary antibodies, sections were washed and incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies. After 1 h, the sections were washed again and mounted with VECTORSHIELD® with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, #H1200). Fluorescence signals were recorded using a BZ-X700 fluorescence microscope (Keyence).

ELISA assays

Concentration of IL-6 or LIF in serum were quantified using IL-6 (Abcam, ab100713) or LIF ELISA kit (Abcam, ab238261) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Western Blotting

Two-three x 105 cells (C2C12-CalcR) were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured in DMEM-HG containing 10%FCS and penicillin/streptomycin). After 24 hours, the medium was changed to serum-free DMEM-HG (starvation medium), and cells were cultured for 3 hours. Elcatonin (final concentration: 0.1 U/mL) was added after 1 hour of starvation. To enhance CalcR signaling, low concentrations of IBMX (final concentration: 5 µM) were co-administered with elcatonin. After 2 hours of starvation, cells were stimulated with either10% FCS or IL-6 (PeproTech, 100 pg/mL), or were non-stimulated, and the cells were additionally cultured for 1 hour, and then the cells were lysed. The C2C12 cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed in 2× SDS–PAGE sample buffer (Sigma) and vigorously agitated for 15 min at room temperature. Lysates were collected and sonicate the lysate on ice using a probe sonicator (pulse on: 10 s, pulse off: 10 s, total sonication time: 10 s, 45% amplitude), and then proteins were denatured for 5 min and separated on TGX FastCast Acrylamide gel (BioRad). Then the proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA) by Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System. The membranes were incubated in TBS-T containing 5% skim milk at room temperature to block non-specific protein binding. The membranes were subsequently incubated in blocking buffer containing the primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. Antibodies for Total YAP (#14074S, 1:1000), phosphorylated YAP S127 (#4911S 1:1000), phosphorylated YAP S397 (#13619S 1:1000), β-tubulin (#2128S, 1:1000), or Laminin A/C (#2032S, 1:1000) were obtained from Cell Signalling Technology. Phosphorylated YAP Y357 (62751 1:1000) were obtained from Abcam. After incubation with the appropriate HRP-labeled secondary antibody (e,g. goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP CST 1:2000) for 1 h at room temperature, the bands were visualized using an Amersham™ ECL™ and Amersham™ ECL Select™ (Cytiva RPN2109 RPN2235). A Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif Inc, Nuclear Extract kit) was used for the separation of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions from C2C12-CalcR. Uncropped and unprocessed scans of the blot were supplied in Source data file.

Statistics

All graphs were generated using Prism 10 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Values are presented as means ± standard deviation (s.d.). Statistical significance was assessed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. For comparisons involving more than two groups, non-repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was employed. A probability value of less than 5% (p < 0.05) was considered statistically significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents and data set. Source data are provided with this paper. All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Caspersen, C. J., Powell, K. E. & Christenson, G. M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 100, 126–131 (1985).

Hartman, J. H. et al. Swimming exercise and transient food deprivation in caenorhabditis elegans promote mitochondrial maintenance and protect against chemical-induced mitotoxicity. Sci. Rep. 8, 8359 (2018).

Cartee, G. D., Hepple, R. T., Bamman, M. M. & Zierath, J. R. Exercise promotes healthy aging of skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 23, 1034–1047 (2016).

Pedersen, L. et al. Voluntary running suppresses tumor growth through epinephrine- and IL-6-dependent NK cell mobilization and redistribution. Cell Metab. 23, 554–562 (2016).

Agudelo, L. Z. et al. Skeletal muscle PGC-1alpha1 modulates kynurenine metabolism and mediates resilience to stress-induced depression. Cell 159, 33–45 (2014).

Chow, L. S. et al. Exerkines in health, resilience and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 18, 273–289 (2022).

Mauro, A. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 9, 493–495 (1961).

Schultz, E., Gibson, M. C. & Champion, T. Satellite cells are mitotically quiescent in mature mouse muscle: an EM and radioautographic study. J. Exp. Zool. 206, 451–456 (1978).

Fuchs, E. & Blau, H. M. Tissue stem cells: architects of their niches. Cell Stem Cell 27, 532–556 (2020).

de Morree, A. & Rando, T. A. Regulation of adult stem cell quiescence and its functions in the maintenance of tissue integrity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 334–354 (2023).

Fessard, A. et al. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation training induces myonuclear accretion and hypertrophy in mice without overt signs of muscle damage and regeneration. Skelet. Muscle 15, 3 (2025).

Darr, K. C. & Schultz, E. Exercise-induced satellite cell activation in growing and mature skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 63, 1816–1821 (1987).

Fukada, S. I., Higashimoto, T. & Kaneshige, A. Differences in muscle satellite cell dynamics during muscle hypertrophy and regeneration. Skelet. Muscle 12, 17 (2022).

Fukada, S. I. & Ito, N. Regulation of muscle hypertrophy: Involvement of the Akt-independent pathway and satellite cells in muscle hypertrophy. Exp. Cell Res. 409, 112907 (2021).

Fukuda, S. et al. Sustained expression of HeyL is critical for the proliferation of muscle stem cells in overloaded muscle. Elife 8, e48284 (2019).

de Sousa, C. A. Z. et al. Time course and role of exercise-induced cytokines in muscle damage and repair after a marathon race. Front. Physiol. 12, 752144 (2021).

Furuichi, Y., Manabe, Y., Takagi, M., Aoki, M. & Fujii, N. L. Evidence for acute contraction-induced myokine secretion by C2C12 myotubes. PLoS ONE 13, e0206146 (2018).

Garneau, L. et al. Plasma myokine concentrations after acute exercise in non-obese and obese sedentary women. Front. Physiol. 11, 18 (2020).

Vierck, J. et al. Satellite cell regulation following myotrauma caused by resistance exercise. Cell Biol. Int. 24, 263–272 (2000).

Masschelein, E. et al. Exercise promotes satellite cell contribution to myofibers in a load-dependent manner. Skelet. Muscle 10, 21 (2020).

Iwamori, K. et al. Decreased number of satellite cells-derived myonuclei in both fast- and slow-twitch muscles in HeyL-KO mice during voluntary running exercise. Skelet. Muscle 14, 25 (2024).

Yamaguchi, M. et al. Calcitonin receptor signaling inhibits muscle stem cells from escaping the quiescent state and the niche. Cell Rep. 13, 302–314 (2015).

Zhang, L. et al. The CalcR-PKA-Yap1 axis is critical for maintaining quiescence in muscle stem cells. Cell Rep. 29, 2154–2163 e2155 (2019).

Baghdadi, M. B. et al. Reciprocal signalling by Notch-Collagen V-CALCR retains muscle stem cells in their niche. Nature 557, 714–718 (2018).

Fukada, S. et al. Molecular signature of quiescent satellite cells in adult skeletal muscle. Stem Cells 25, 2448–2459 (2007).

Ikemoto-Uezumi, M. et al. Reduced expression of calcitonin receptor is closely associated with age-related loss of the muscle stem cell pool. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle Rapid Commun. 2, 1–13 (2019).

Kaneshige, A. et al. Relayed signaling between mesenchymal progenitors and muscle stem cells ensures adaptive stem cell response to increased mechanical load. Cell Stem Cell 29, 265–280.e266 (2022).

D’Hulst, G., Palmer, A. S., Masschelein, E., Bar-Nur, O. & De Bock, K. Voluntary resistance running as a model to induce mTOR activation in mouse skeletal muscle. Front. Physiol. 10, 1271 (2019).

Ismaeel, A. et al. Division-independent differentiation of muscle stem cells during a growth stimulus. Stem Cells 42, 266–277 (2024).

Charles, J. P., Cappellari, O. & Hutchinson, J. R. A dynamic simulation of musculoskeletal function in the mouse hindlimb during trotting locomotion. Front Bioeng. Biotechnol. 6, 61 (2018).

Conboy, I. M. et al. Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment. Nature 433, 760–764 (2005).

Rodgers, J. T. et al. mTORC1 controls the adaptive transition of quiescent stem cells from G0 to G(Alert). Nature 510, 393–396 (2014).

Brett, J. O. et al. Exercise rejuvenates quiescent skeletal muscle stem cells in old mice through restoration of Cyclin D1. Nat. Metab. 2, 307–317 (2020).

Piccirillo, R. Exercise-induced myokines with therapeutic potential for muscle wasting. Front. Physiol. 10, 287 (2019).

Whitham, M. & Febbraio, M. A. The ever-expanding myokinome: discovery challenges and therapeutic implications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15, 719–729 (2016).

Serrano, A. L., Baeza-Raja, B., Perdiguero, E., Jardi, M. & Munoz-Canoves, P. Interleukin-6 is an essential regulator of satellite cell-mediated skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Cell Metab. 7, 33–44 (2008).

Guerci, A. et al. Srf-dependent paracrine signals produced by myofibers control satellite cell-mediated skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Cell Metab. 15, 25–37 (2012).

Broholm, C. & Pedersen, B. K. Leukaemia inhibitory factor-an exercise-induced myokine. Exerc Immunol. Rev. 16, 77–85 (2010).

Broholm, C. et al. Exercise induces expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor in human skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 586, 2195–2201 (2008).

Spangenburg, E. E. & Booth, F. W. Leukemia inhibitory factor restores the hypertrophic response to increased loading in the LIF(-/-) mouse. Cytokine 34, 125–130 (2006).

Broholm, C. et al. LIF is a contraction-induced myokine stimulating human myocyte proliferation. J. Appl Physiol. 111, 251–259 (2011).

Sun, L. et al. JAK1-STAT1-STAT3, a key pathway promoting proliferation and preventing premature differentiation of myoblasts. J. Cell Biol. 179, 129–138 (2007).

Zhu, H. et al. STAT3 regulates self-renewal of adult muscle satellite cells during injury-induced muscle regeneration. Cell Rep. 16, 2102–2115 (2016).

Taniguchi, K. et al. A gp130-Src-YAP module links inflammation to epithelial regeneration. Nature 519, 57–62 (2015).

Varelas, X. The Hippo pathway effectors TAZ and YAP in development, homeostasis and disease. Development 141, 1614–1626 (2014).

Sugihara, T. et al. YAP tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear localization in cholangiocarcinoma cells are regulated by LCK and independent of LATS activity. Mol. Cancer Res. 16, 1556–1567 (2018).

Fukada, S. I., Akimoto, T. & Sotiropoulos, A. Role of damage and management in muscle hypertrophy: Different behaviors of muscle stem cells in regeneration and hypertrophy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 1867, 118742 (2020).

Tsuchiya, Y., Kitajima, Y., Masumoto, H. & Ono, Y. Damaged myofiber-derived metabolic enzymes act as activators of muscle satellite cells. Stem Cell Rep. 15, 926–940 (2020).

Zhou, S. et al. Myofiber necroptosis promotes muscle stem cell proliferation via releasing Tenascin-C during regeneration. Cell Res. 30, 1063–1077 (2020).

Patsalos, A. et al. A growth factor-expressing macrophage subpopulation orchestrates regenerative inflammation via GDF-15. J. Exp. Med. 219 (2022).

Lukjanenko, L. et al. Aging disrupts muscle stem cell function by impairing matricellular WISP1 secretion from fibro-adipogenic progenitors. Cell Stem Cell 24, 433–446 e437 (2019).

Wei, W. et al. Organism-wide, cell-type-specific secretome mapping of exercise training in mice. Cell Metab. 35, 1261–1279.e1211 (2023).

Keller, J. et al. Calcitonin controls bone formation by inhibiting the release of sphingosine 1-phosphate from osteoclasts. Nat. Commun. 5, 5215 (2014).

Goda, T. et al. Calcitonin receptors are ancient modulators for rhythms of preferential temperature in insects and body temperature in mammals. Genes Dev. 32, 140–155 (2018).

Cheng, W. et al. Calcitonin receptor neurons in the mouse nucleus tractus solitarius control energy balance via the non-aversive suppression of feeding. Cell Metab. 31, 301–312 e305 (2020).

Moreira, L. M. et al. Paracrine signalling by cardiac calcitonin controls atrial fibrogenesis and arrhythmia. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2890-8 (2020).

Cressman, D. E. et al. Liver failure and defective hepatocyte regeneration in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Science 274, 1379–1383 (1996).

Garbers, C. et al. Plasticity and cross-talk of interleukin 6-type cytokines. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 23, 85–97 (2012).

Thiem, S. et al. mTORC1 inhibition restricts inflammation-associated gastrointestinal tumorigenesis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 767–781 (2013).

Rodgers, J. T., Schroeder, M. D., Ma, C. & Rando, T. A. HGFA is an injury-regulated systemic factor that induces the transition of stem cells into GAlert. Cell Rep. 19, 479–486 (2017).

Antos, C. L. et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy and sudden death resulting from constitutive activation of protein kinase a. Circ. Res. 89, 997–1004 (2001).

Imaeda, A. et al. Myofibroblast beta2 adrenergic signaling amplifies cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Biochem Biophys. Res Commun. 510, 149–155 (2019).

Betz, U. A. et al. Postnatally induced inactivation of gp130 in mice results in neurological, cardiac, hematopoietic, immunological, hepatic, and pulmonary defects. J. Exp. Med. 188, 1955–1965 (1998).

Kaneshige, A. et al. Detection of muscle stem cell-derived myonuclei in murine overloaded muscles. STAR Protoc. 3, 101307 (2022).

Rosenblatt, J. D., Lunt, A. I., Parry, D. J. & Partridge, T. A. Culturing satellite cells from living single muscle fiber explants. Vitr. Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 31, 773–779 (1995).

Shinin, V., Gayraud-Morel, B. & Tajbakhsh, S. Template DNA-strand co-segregation and asymmetric cell division in skeletal muscle stem cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 482, 295–317 (2009).

Ikemoto-Uezumi, M. et al. Pro-insulin-like growth factor-ii ameliorates age-related inefficient regenerative response by orchestrating self-reinforcement mechanism of muscle regeneration. Stem Cells 33, 2456–2468 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express our gratitude to Prof. Werner Muller for permitting us to use gp130-floxed mice and Prof. Shahragim Tajbakhsh for sharing his protocol for antibody administration and for helpful suggestions and discussions. We also thank Editage for providing the English language editing services. S. F. was funded by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (19H04000, 22H03466), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A)(25H01098), a Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research (20K21757), the Suzuken Memorial Foundation, and the Takeda Science Foundation. L.Z. was funded by the Chongqing Municipal Basic and Frontier Research Project (CSTB2023NSCQ-MSX0303), National Natural Science Foundation of China (32300666), and the CQMU Program for Youth Innovation in Future Medicine (W0169). This research was partially supported by the Research Support Project for Life Science and Drug Discovery (Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (BINDS)) from AMED under grant numbers JP24ama121054, JP25ama121054, JP24ama121052, and JP25ama121052.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z. developed the study design, and contributed to data collection, analysis, interpretation, and manuscript writing. T.K., A.N., N.M., K.I., J.X. and Y.L. collected and analyzed the data. D.K. and M.M. provided gp130-floxed mice. A.U. contributed to experimental materials and data interpretation. A.K. contributed to interpretation, financial support, and manuscript writing. T.Y. contributed to writing and discussing the kinds of exercise animal models and muscle physiology. T.A. contributed to the setup of the wheel-running experiments. S.F. worked on the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, financial support, and manuscript writing. For Fig. 1, T.K. and L.Z. generated the data and prepared panels C, D, F, G, I, and K. S.F. generated cartoons A, B, E, H, and J and assembled the figure. For Fig. 2, L.Z. generated the data and prepared panels A-C and E-G, and S.F. generated cartoons D and assembled the figure. For Fig. 3, L.Z. generated the data and prepared panels B-F and H-M, A.N. contributed to a part of the experiments of H-M, and S.F. generated cartoons A and G and assembled the figure. For Fig. 4, L.Z. generated the data and prepared panels B-E and G-J, and S.F. generated cartoons A and F and assembled the figure. For Fig. 5, L.Z. generated the data and prepared panels B-G, N.M., K.I. and J.X. assisted with these experiments, and S.F. generated the cartoon A and assembled the figure. For Fig. 6, L.Z. generated the data and prepared panels A, C-H, and J-M. N.M., K.I. and J.X. assisted with these experiments, and S.F. generated the cartoons B and I and assembled the figure. For Fig. 7, L.Z. generated the data and prepared all panels and C-H. J.X., Y.L. and A.K. assisted with these experiments, and S.F. assembled the figure.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Kaji, T., Nakamura, A. et al. Calcitonin receptor downregulation and exercise-conditioned blood enable systemic muscle stem cell proliferation. Nat Commun 16, 10576 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65684-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65684-1