Abstract

Developing dynamic polymeric materials that possess closed-loop recyclability under mild conditions and outstanding mechanical properties is a highly desirable but challenging pursuit. This study presents a entropy-driven toughening strategy through divergent metal-pyrazole (DiMP) coordinations, achieving a mechanically robust and recyclable polyurethane (PU) elastomer. DiMP interactions feature multiple discrete complexes (i.e., CuL2, Cu2L2, and CuL3, where L = dipyrazole ligand) to minimize the entropy-gain mediated compensatory effect during bond dissociation and accordingly increase energy dissipation upon polymer deformation. The DiMP-crosslinked PUs (DiMPUs) exhibit an unprecedented 11-fold improvement in toughness (310.8 MJ m−3), a tensile strength of 59.0 MPa, and exceptional elastic recovery (94%), attributed to gradient energy dissipation mechanisms involving dynamic DiMP coordinations and synergistically hierarchical hydrogen bonds. Crucially, the selective acidolysis of pyrazole-urea bonds, together with the inherently weak protonation affinity of pyrazole relative to amine, allows monomers to be efficiently recovered and reengineered into virgin materials, manifesting the closed-loop recyclability. This work provides a sustainable blueprint for dynamic polymers balancing mechanical robustness and environmental circularity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polyurethanes (PUs) are ubiquitous in consumer marketplaces and industrial applications, owing to their versatility and excellent mechanical properties1,2. PUs rank as the sixth most produced polymer globally with annual production exceeding 20 million tons. Currently, addressing polymer waste in oceans and landfills has become a global priority3,4. Dynamic chemistry, characterized by labile chemical linkages, offers a promising approach to enhance the sustainability of polymers by enabling the development of new polymer architectures5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 or making the existing polymeric materials degradable and recyclable16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. They mainly rely on dynamic covalent/non-covalent bonds, which can be broken and reformed under specific conditions. However, the dynamic properties, motivated by bond reversibility and chain mobility, often lead to increased plasticity and reduced mechanical performance27.

The enhancement of polymer toughness can be achieved by enriching the amount of energy being dissipated upon deformation before breaking (Fig. 1a)28,29. Being more dissociatively labile than most covalent bonds comprising the network, the scission of weak non-covalent interactions under moderate loads enhances the material’s ability to dissipate mechanical energy without failure, thereby increasing the mechanical toughness. Recent efforts have shown that the introduction of non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding30 and metal-ligand coordination31,32,33,34,35,36,37, into polymer chains forming dynamic polymer networks is an effective method for improving the toughness of polymers.

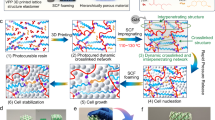

a Energy dissipated during the cyclic loading and unloading process. Mechanical work (W) is divided into irreversibly dissipated energy (E1) and stored elastic energy (E2). b Thermodynamic explanation for the entropy-driven toughening mechanism. Because of the entropy rise (ΔS > 0) during the dissociation of non-covalent bonds, Gibbs free energy (ΔG) is inversely proportional to ΔS. Consequently, a lower entropy gain will result in a higher energy input for bond rupture, thus enhancing energy dissipation during polymer elongation (assuming comparable enthalpy changes for the dissociation of identical coordination bonds in analogous geometries). c The diverse metal-pyrazole coordination architectures with higher disorder exhibit a lower entropy increase during stretching, thereby suppressing entropy-gain compensatory effects. d Schematic illustrating the synthesis of DiMPU-Cu elastomers and their molecular structures. PTMG poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol, HMDI hydrogenated methylene diphenyl diisocyanate.

In terms of thermodynamics, the dissociation of typical non-covalent interactions is often accompanied by an enthalpy increase (endothermic, ΔH > 0) and an entropy gain (more microstates, ΔS > 0). Based on the basic thermodynamic principle (ΔG = ΔH − TΔS), non-covalent interactions with the high-enthalpy increase or low-entropy gain may generate greater energy dissipation during polymer elongation and hence enhance mechanical toughness (Fig. 1b). Different from hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) often involving flexible molecules, metal-ligand bonds are generally stronger and more directional, leading to more rigid and stable structures32. Therefore, the dissociation of metal-ligand complexes typically produces a larger increase in entropy compared to breaking H-bonds, likely causing reduced energy dissipation upon stretching38,39. Such a rationale may explain the observed higher toughness of PU elastomers employing multiple H-bonds as the dominant physical crosslinkers40,41,42,43,44. We believe that decreasing entropy variation during deformation should be an alternative way to further improve energy dissipation and toughness. Unfortunately, despite the abundance of metal-ligand interactions that can be exploited for structure design31,32,33, the potential of entropy-driven toughening for polymeric materials remains largely unexplored45,46.

In this work, we demonstrate the construction of robust and recyclable PUs utilizing divergent metal-pyrazole (DiMP) interactions via a low-entropy-gain-driven toughening approach (Fig. 1c, d). Unlike polymer toughening strategies relying on traditional metal-ligand interactions47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, which typically dissipate energy through a uniform coordination complex via a high-enthalpy-increase process33, metal-pyrazole interactions can generate diverse coordination architectures, three discrete complexes from the same ligand and metal, which could effectively minimize the entropy-gain induced compensatory effect during bond dissociation and therefore increase the energy dissipation (Fig. 1c). Coupled with hierarchical hydrogen bonds, the divergent metal-pyrazole crosslinked polyurethane (DiMPU) establishes gradient energy dissipation mechanisms, achieving a dramatic 11-times enhancement in toughness. In addition, the selective cleavage of pyrazole-urea bonds under mild acidic conditions enables controlled degradation of DiMPUs. Along with the remarkable disparity in protonation affinity between pyrazole and amine, a practical and facile separation of original monomers can be achieved, paving the way for closed-loop recycling.

Results

Design and characterization of divergent metal coordination

Di(pyrazole-urea) (DPU) L was designed as the model ligand to bind with copper ions (Cu2+) to investigate the characteristics of coordination chemistry (Supplementary Figs. 1–5). We speculated that bidentate ligands with binding sites at 1,7-position tend to form diverse coordination complexes, whereas those with 1,4/1,5-positions are more likely to yield fixed, well-defined structures via stable 5/6-membered rings. As shown in Fig. 2a, upon mixing the MeOH solutions of CuCl2 and L in an equimolar ratio, a substantial amount of green precipitate appeared immediately, suggesting the formation of insoluble coordination compounds. High resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HR-ESI-MS) was employed to identify the compositions of potential coordination complexes (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 6). Regardless of the L dimer peak, one prominent set of peaks with +1 charge state associated with CuL2Cl2 was clearly observed as a result of the loss of one Cl−, whose molecular weight agreed well with the expected chemical composition of [CuL2Cl]+. A comprehensive examination of the HR-MS peaks uncovered another two sets of signals corresponding to the complexes Cu2L2Cl4 and CuL3Cl2. All experimental isotope patterns closely matched the theoretical simulations. In traveling wave ion mobility-mass spectrometry (TWIM-MS), these complexes with different ion charge states and sizes were effectively distinguished through their drift times (Fig. 2c), which were directly related to the characteristic ion collision cross section (CCS, Supplementary Fig. 7.). These results proved that metal-pyrazole interactions can give rise to diverse coordination structures.

a Schematic diagram and photographs of the coordination reaction between DPU L and CuCl2 (molar ratio = 1:1, 100 mM) showing the formation of complex precipitates and diverse structures. b HR-MS spectra of metal-pyrazole complexes. Inset: observed and simulated isotope patterns for [CuL3]2+, [Cu2L2Cl]+, and [Cu2L2Cl2]·Na+. c TWIM-MS plots (m/z vs drift time) of coordination complexes. d ITC titration data of DPU L (14 mM) with Cu(OTf)2 (50 mM) at 25 °C (solvent: MeOH). e 1H NMR spectroscopic titrations of DPU L (0.014 mM) by varying the concentration of CuCl2 (0.0014-0.07 mM) in d6-DMSO. f DFT-optimized structures of CuL2, Cu2L2, and CuL3. g AIM molecular diagrams of CuL3. h IGMH analysis of non-covalent interactions in CuL3. Color code: red for repulsive, yellow for weakly repulsive, green for weakly attractive, and blue for strongly attractive forces. Isovalue: 0.004 a.u.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) was used to understand the binding affinity of Cu2+ and ligand L (Fig. 2d). Our initial investigations under varying conditions barely detected obvious coordination thermal flow (Supplementary Fig. 8), revealing minimal enthalpy changes in the coordination reactions. By switching counterions from the coordinating anion Cl− to the non-coordinating anion OTf−, the exothermic profile with an association constant (Ka) of 1.41 × 103 M−1 was obtained, which is quite small compared to common coordination bonds but still higher than that of H-bonds33,56. As we mentioned above, the relatively weak and dynamic copper-pyrazole interactions contributed to producing DiMP coordinations.

Furthermore, 1H NMR titration was performed to detect possible binding sites of DPU with Cu2+. On account of the paramagnetic properties of Cu2+, the titration of L with Cu2+ led to NMR signal broadening and shifting. The pyrazole protons (H6 and H7) displayed evident line broadening and downfield shifting upon incremental addition of Cu2+, with nearly complete baseline merging observed at the L/Cu2+ ratio of 1:1 (Fig. 2e). The N-H peak (H8) displayed a similar pattern but with a delayed tendency. These proofs indicated that the N atom in pyrazole was the chelating site. In contrast, the H1-H5 signals remained largely unaffected during this process, even with 2 eq of Cu2+, as these protons were located farther from the paramagnetic Cu2+ center.

To gain further insights into the structural details of coordination complexes, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were conducted using methyl di(pyrazole-urea) and CuCl2 as model substrates (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 9). Theoretical studies disclosed that the bidentate coordination mode involving both the nitrogen of pyrazole and oxygen of carbonyl (a hexacoordinate copper complex) was energetically disfavored as opposed to the monodentate coordination mode with pyrazole’s nitrogen. Conformational analysis of CuL2 identified the thermodynamically preferred structure as one stabilized by an intermolecular hydrogen bonding between the ligands, with a coordination binding energy of −1.93 eV. Otherwise, dipyrazole acted as a bridging ligand in Cu2L2 to form a dinuclear metal complex, with each copper center exhibiting a distorted square planar geometry. Similar to CuL2, CuL3 adopted a tetracoordinate structure stabilized by hydrogen bonding, which was calculated to be the lowest energy state among these structures.

The topological properties of the electron density distribution were analyzed using the atoms in molecules (AIM) theory with the optimized geometry of CuL3. AIM analysis indicated bond critical points (BCPs) between the pyrazole’s nitrogen and copper with the electron density (ρBCP) of 0.0755 a.u. and the Laplacian of the electron density (∇2ρ) of 0.2448 a.u. (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Table 1), which were typical for weak coordination bonds. These findings were in agreement with the ITC experiments. The molecular diagrams revealed that three intermolecular H-bonds were formed, where the proton of urea formed H-bonds with urea’s carbonyl (NH···O), pyrazole’s nitrogen (NH···N), and the chlorine (NH···Cl), respectively. The ρBCP of H-bonds, ranging from 0.0174 to 0.0724 a.u., suggests energetically favorable non-covalent bonds, confirmed by the positive ∇2ρ. The independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partition (IGMH) was applied to study and visualize the non-covalent interactions (Fig. 2h). The green areas represented the attractive interactions of H-bonds (NH···O and NH···N), CH···π, and van der Waals (vdW) forces, while the greenish-blue zones corresponded to the relatively strong hydrogen bond (NH···Cl) and coordination bonds. These theoretical investigations highlighted the presence of multiple non-covalent interactions in DiMP structures aside from the coordination bonds, which would be vital for energy dissipation in polymer systems.

Design and Characterizations of DiMPUs

To achieve superior toughness, the divergent metal-pyrazole crosslinked polyurethane (DiMPU) was designed by utilizing the entropy-driven toughening strategy. First, linear poly(pyrazole-urethane) (PPU) was synthesized by a two-step polymerization approach using dipyrazole as chain extender (Supplementary Figs. 10-11), followed by Cu2+ coordination and subsequent solvent evaporation to yield the amorphous DiMPU elastomer (denoted as DiMPU-Cux, x is the molar ratio of Cu to dipyrazole, Supplementary Figs. 12-14). The interaction between Cu2+ ions and pyrazole groups in DiMPU-Cu was verified by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis. The EPR spectrum of CuCl2 exhibited the characteristic fine structure of paramagnetic Cu2+ ions, while the DiMPU-Cu1 curve validated a loss of this fine structure accompanied by a notable shift of the g factor value (Supplementary Fig. 15), suggesting an interaction between Cu2+ and PPU. Additionally, the binding energy of N 1 s electrons for the pyridinic N in pyrazole moved from 400.7 eV (DiMPU) to 401.5 eV (DiMPU-Cu1), confirming that the N atom of pyrazole was involved in the coordination with Cu2+ (Supplementary Fig. 16). The crosslinking via coordination in DiMPU was also proved by the constant rubber plateau and the prominently improved elastic plateau modulus after Cu2+ addition in dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA, Supplementary Fig. 17). Rheological tests also confirmed a higher crosslink density for the DiMPU-Cu elastomer (Supplementary Fig. 18).

Stress-strain curves of DiMPUs with varying Cu2+ ratios revealed that mechanical properties were considerably enhanced upon the incorporation of Cu2+ (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Table 2). Notably, the DiMPU-Cu1 exhibited preeminent mechanical properties with a tensile strength of 59.0 MPa and toughness of 310.8 MJ m−3, representing great improvements of sixfold and elevenfold over PPU, respectively. The material also demonstrated superior toughness and elastic recovery compared to the conventional commercial PU elastomers (Supplementary Fig. 19, S20, and Supplementary Table 3). Since the true stress-strain curve has a more precise evaluation of the stress resistance in highly extensible materials, the true stress at break of DiMPU-Cu1 was calculated to be as high as 0.77 GPa (Fig. 3b). The high strength and toughness of DiMPU-Cu can also be visually reflected by a thin strip of DiMPU-Cu1 (0.1 g, 0.2 mm T × 3.0 mm W × 30.0 mm L) that can lift a 5.0 kg weight, 50 000 times its own mass, without breaking (inset of Fig. 3b).

a Engineering stress-strain curves and b typical true stress-strain curves of PPU and DiMPU-Cu elastomers. Inset in b Photograph showing a DiMPU-Cu1 thin sheet specimen (weight: 0.1 g) lifting a weight of 5.0 kg. c Cyclic tensile test curves of DiMPU-Cu1 in successive loading-unloading cycles with increasing strains, performed without delay time. d The corresponding hysteresis area of PPU, DiMPU-Cu0.5, and DiMPU-Cu1 at each loading-unloading cycle. e Cyclic stress-strain curves for DiMPU-Cu1 under ten consecutive cycles with 300% strain and no waiting time, followed by recovery at 50 °C for 1 h (Cycle 11). f Quantification of the cyclic behavior: hysteresis ratio (left y-axis) and recovery degree (right y-axis) for DiMPU-Cu1. (1–10: continuous; Cycle 11 tested after 1 h recovery at 50 °C). g Photographs of the original, elongated, and recovered DiMPU-Cu1 elastomers. h Comparison between DiMPU-Cu1 and previously reported similar materials in terms of ultimate stress, recovery degree, and toughness improvement factor (the toughness ratio of metal-coordinated versus non-coordinated samples). i Tensile curves of intact and notched DiMPU-Cu1.

Cyclic tensile tests with increasing strains without delay time were performed to investigate the energy dissipation behaviors of the elastomer (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 21). The hysteresis areas of DiMPU-Cu gradually grew with increasing strain, while the dissipated energies rose significantly with the increment of copper ions, being much higher than those of non-coordinated PPU (Fig. 3d). This was consistent with the trend of improved mechanical toughness, meaning that the gradual breaking of H-bonds and diverse coordination architectures caused a gradient energy dissipation as the strain increased. In the 11-cycle load-unload test of DiMPU-Cu1 (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Figs. 22–24), the first cycle exhibited a large hysteresis area, attributed to energy dissipation from the rupture of hydrogen and coordination bonds. The second cycle, performed without a waiting time, showed a markedly reduced hysteresis area due to insufficient time for bond reformation. Subsequent cycles displayed negligible changes in hysteresis areas, indicating that the elastomer network reached a metastable state after energy dissipation through the molecular chain slippage and weak bond breaking. When allowed to relax for 1 h at 50 °C, the curve nearly returned to its original state, suggesting the reassociation of broken weak bonds and network recovery. To quantitatively investigate recovery ability, the recovery degree (1-residual strain/strain) was determined to be 94% for the first cycle and remained up to 89% even after ten cycles (Fig. 3f). The excellent resilience was also visualized in Fig. 3g. The initial length of the DiMPU-Cu1 sample, after being stretched to 500%, could be fully recovered after a 3-hour rest at room temperature. This approach fundamentally differs from conventional metal-ligand coordination strategies, such as those employing uniform coordination complexes, which typically yield modest toughness enhancements despite higher mechanical strength48. In stark contrast, our entropy-mediated strategy maximizes energy dissipation capacity, resulting in an 11-fold toughness enhancement over the pristine PU—a record high among metal-coordinated PU elastomers reported to date (Fig. 3h). This highlights the effectiveness of harnessing diverse coordination environments for superior toughening.

Dynamic weak interactions of metal coordination and H-bonds in DiMPU-Cu could also supply elastomers with excellent damage resistance. The fracture energy (Г), the energy per unit area required for crack growth in a material, was evaluated using the Rivlin-Thomas pure shear test (Supplementary Fig. 25). As shown in Fig. 3i, the notched DiMPU-Cu1 sample could still be stretched to more than twelve times its original length with a fracture energy as large as 347.4 kJ m−2, which is over 30 times greater than natural rubber (10 kJ m−2). The trouser tear test also exhibited a fracture energy of 283.9 kJ m−2, illustrating the distinguished mechanical tear resistance of the elastomer (Supplementary Fig. 26). The excellent performance of the DiMPU-Cu1 elastomer could be attributable to the divergent coordination bonds and H-bonds. Under external forces, the dynamic rupture and reformation of these bonds allow localized stress at the crack tip to be redistributed across the entire network, effectively passivating cracks and preventing lateral propagation.

Toughening mechanism for DiMPUs

To elucidate the toughening mechanism of DiMP crosslinked PUs, we designed two comparative systems using pyridine-2,6-dimethanol (Py) and 4,4’-(2,2’-bipyridine)-4,4’-diyldimethanol (BPy) as chain extenders instead of dipyrazole, with all other components kept identical (Supplementary Figs. 27-30). Compared with the diverse coordination mode in DiMPUs, the control systems form uniform coordination architectures, which would induce a high-entropy gain upon dissociation (Fig. 1c)32,34,53. The control PUs exhibited modest toughness enhancements of 2.35- and 3.03-fold over the pristine samples for PyPU-Cu0.5 and BPyPU-Cu0.5, respectively, less than the 11-fold improvement achieved by DiMPU-Cu1 (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 31 and Supplementary Table 4). Additionally, the DiMPU network demonstrated superior toughness, recovery degree, and tensile strength than uniform metal-ligand crosslinked networks. These experiments substantiate that the low-entropy gain, originating from the multiplicity of divergent metal-pyrazole interactions, is the pivotal effect for energy dissipation, transcending reinforcing mechanisms of reversible bonding and crosslinking.

a Engineering stress-strain curves of uniform coordination systems (PyPU and BPyPU) and DiMPU elastomers. b Typical force-extension curves during single-molecule force spectroscopy characterization of DiMPU-Cu1 and PPU. c Histogram of the rupture force of DiMPu-Cu1. d C = O vibration deconvolution of DiMPU-Cu1 showing six resolved peaks corresponding to: Ⅰ (free urethane), Ⅱ (disordered H-bonded urethane), Ⅲ (ordered H-bonded urethane), Ⅳ (free urea), Ⅴ (disordered H-bonded urea), Ⅵ (ordered H-bonded urea). e The synchronous and f asynchronous 2DIR spectra calculated for the 1750–1400 cm-1 band of DiMPU-Cu1. Red and blue areas indicate positive and negative values, respectively, and signal intensity increases with color intensity. g 2D-SAXS patterns of DiMPU-Cu1 subjected to different stretching strains. h 1D-SAXS experimental data of DiMPU-Cu1 with Zernike-Prins model fitting (red line). Inset: the schematic diagram of multiphase structures for DiMPU-Cu1 according to fitting results. i AFM image of the DiMPU-Cu1 elastomer. Inset: size distributions of hard segment clusters. j 1D-SAXS profiles of DiMPU-Cu1 under different stretching strains.

We further used single-molecule force spectroscopy to characterize the presence of diverse metal–pyrazole complexes in polymer systems under stretching. Two single polymer chains of PPU and DiMPU-Cu1 were stretched to an extended state by using AFM, respectively (Fig. 4b, c, and Supplementary Fig. 32). The PPU sample (without Cu2+) exhibited a single rupture force peak centered at a low force regime of 96 pN, which corresponded to the detachment of the macromolecule from the substrate37,57. In contrast, the DiMPU-Cu1 sample displayed a typical sawtooth-like force-extension curve, and we observed much stronger rupture events with forces reaching up to 128, 376, and 679 pN according to the statistics data (Fig. 4c). However, in the BPyPU-Cu0.5 comparison system, only a single peak was observed at approximately 192 pN (Supplementary Fig. 33). The multiple, high-force peaks confirm the co-existence of diverse coordination complexes (CuL2, Cu2L2, CuL3), each with a unique stretching force. This creates a gradient energy dissipation system where hierarchical coordination bonds rupture sequentially upon deformation, effectively toughening the material.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) measurement was performed to investigate the hydrogen bonding array in DiMPUs (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 34 and Supplementary Table 5). The FTIR spectrum of the C = O stretching absorption band in the range of 1800–1600 cm−1 was deconvoluted into six sub-peaks, which can be assigned to the free, H-bonded-disordered, and H-bonded-ordered C = O in both urethane and pyrazole-urea groups, corroborating the formation of hierarchical H-bonds. Quantitative analysis showed that the H-bonded fractions in DiMPU-Cu1 increased to 68% in comparison to 52% in non-coordinated PPU. These results indicated that the DiMP structure played a synergistic role in the toughening process, providing diverse coordination crosslinking and meanwhile promoting the hydrogen-bonded assembly among PU segments. What’s more, the pronounced improvement in toughness, despite a slight increase in the hydrogen bonding ratio, emphasized the predominant role of DiMP coordination interactions in the toughening effect. In addition, in situ temperature-dependent FTIR spectroscopy was used to evaluate the thermal sensitivities of the dynamic interactions in DiMPU-Cu1 (Supplementary Fig. 35). With increasing temperature from 30 to 130 °C, the C = O bands were blueshifted and the spectral intensities of H-bonded C = O groups declined, also accompanied by the diminished intensity of the v(C = N) of pyrazole at 1460 cm−158, suggesting the heat-induced dissociation of both coordination bonds and H-bonds. Two-dimensional correlation infrared spectra (2DIR) were further generated to study the thermally responsive sequence of different weak bonds (Fig. 4e, f, and Supplementary Fig. 36). Following Noda’s rule, with careful consideration of both auto-/cross-peaks in the synchronous and asynchronous spectra, the temperature sensitivity of different groups upon heating (ordered from fast to slow) was as follows: 1653 cm−1 (v(C = O), H-bonded pyrazole-urea) > 1662 cm−1 (v(C = O), H-bonded urethane) > 1739 cm−1 (v(C = O), free urethane) > 1693 cm−1 (v(C = O), free pyrazole-urea) > 1450 cm−1 (v(C = N), pyrazole), where the slowest one primarily corresponded to the C = N influenced by coordination interactions. Overall, these results convincingly demonstrated the presence of both multiple H-bonds and diverse coordination bonds in the elastomers, which could be responsible for the energy dissipation through bond cleavage.

The aggregation structure of DiMPUs and the structural change during stretching were then thoroughly investigated to further understand the origin of their distinguished mechanical properties using small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS, Fig. 4g and Supplementary Figs. 37-38). The 2D-SAXS patterns of DiMPU-Cu1 exhibited an isotropic, round scattering ring, indicating the electric-rich components randomly dispersed in the matrix. The observed relatively strong scattering intensity in DiMPUs also verified the densification of hard domains resulting from the DiMP-induced aggregation of hard segments. The microphase separation structure of elastomers can be well-described by the globular domains on a distorted lattice (Zernike-Prins) model. The periodicity (d, the average distance between hard domains) decreased from 12.6 nm for PPU to 10.7 nm for DiMPU-Cu1, while their scattering body radii (R) remained nearly unchanged (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 39). This indicated that the assembly of pyrazole-urea and urethane was promoted by coordination interactions, resulting in the generation of additional hard domains. The microphase separation behaviors in DiMPUs accorded with phase analysis by atomic force microscopy (AFM, Fig. 4i and Supplementary Fig. 40). When subjected to stretching, the 2D-SAXS pattern became ellipsoidal, indicating deformation of the hard-phase domains along the stretching direction. Further stretching to 400% strain or higher resulted in a significant reduction in scattering intensity along the stretching direction and a shift of the scattering peak to lower q values (Fig. 4j). These observations implied that H-bonds and coordination bonds underwent dissociation upon deformation, leading to the disruption of phase-separated domains, which can significantly dissipate energy and enhance toughness. Notably, when relaxed at room temperature for 6 h, the scattering pattern reverted to the original shape and the microphase-separated structure recovered, arising from the reassociation of dynamic bonds.

Recycling, closed-loop recycling, and self-healing of DiMPUs

Separating recycled materials from plastic waste streams is a crucial yet costly step toward achieving a sustainable economy. Since pyrazole (pKa of its conjugate acid is 2.5) can be protonated under low pH, it was supposed that the solubility of DiMPU elastomers in acidic aqueous solution can be obviously enhanced, allowing the easy separation of DiMPUs from complex plastic waste. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, pieces from various plastic products, including PS, PA, PMMA, PVC, PU, PET, ABS, PP, PC, and PE, were mixed with DiMPU-Cu1. After the addition of 5 M H2SO4 aqueous solutions into plastic mixtures and stirring for 20 min (Supplementary Fig. 41), the DiMPU-Cu1 elastomer was selectively dissolved in the acid solution, whereas the other plastics remained insoluble. After filtration and subsequent removal of Cu2+ ions through water-induced precipitation, the recycled PPU sample can be redissolved and cast into films without losing mechanical properties (Fig. 5b).

a The selective recycling of DiMPU-Cu1 from a plastic waste stream containing PS (polystyrene), PA (polyamide), PMMA (polymethyl methacrylate), PVC (polyvinyl chloride), PU (polyurethane), PET (polyethylene terephthalate), ABS (acrylonitrile butadiene styrene), PP (polypropylene), PC (polycarbonate), and PE (polyethylene). b Mechanical properties of the original and recycled DiMPU-Cu1. c Time-dependent degradation profiles of DPU L and urethane analog in 2 M DCl/d6-DMSO at 70 °C. d A schematic representation of closed-loop recycling of DiMPU-Cu1 and polyurea thermosets (All 1H NMR spectra were recorded in d6-DMSO.). THDI trimer of hexamethylene diisocyanate.

During the degradation of urethanes, isocyanate intermediates are typically generated, which are sensitive to moisture and susceptible to side reactions1,3,18,20. This creates a complicated system that hinders the separation of high-value raw materials, making the efficient chemical recycling of end-of-life PUs highly challenging. Given that the protonation of pyrazole-urea bonds can accelerate their dissociation, the selective degradation of pyrazole-ureas in PUs can enable the feasibility of closed-loop recycling of DiMPUs. Hydrolysis kinetics of the DPU L and urethane analog (Supplementary Figs. 42-43) were determined under a 2 M DCl/d6-DMSO solution (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Figs. 44-45). As expected, pyrazole-urea was almost completely decomposed into protonated pyrazole and amine after 24 h at 70 °C; nevertheless, the urethane showed a negligible degradation (<1%). The whole closed-loop recycling process is shown in Fig. 5d. Following the removal of Cu2+ ions from DiMPU-Cu1, the polymer was then dissolved in an aqueous mixture of 2 M HCl/EtOH and underwent chemoselective hydrolysis at 70 °C for 36 h. After neutralization and solvent evaporation, a crude mixture of dipyrazole and macromolecular diamine was isolated. Ascribed to the easier protonation of primary alkylamines (pKa of the conjugate acid is ~10.0), the macromolecular diamine was well solubilized in water at pH 5, whereas dipyrazole was insoluble, resulting in an efficient separation of the macromolecule (85% recovered) and small molecule (87% recovered). Thereafter, the macromolecule diamine can be readily converted to isocyanates with triphosgene for the resynthesis of pristine materials, realizing the closed-loop recovery system. Moreover, benefiting from the distinguishing feature of the selective acidolysis and low protonation capacity of pyrazole, the closed-loop recycling of polyurea thermosets was smoothly accomplished as well (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 46).

The dynamic nature of H-bonds, coordination bonds, and pyrazole-urea bonds in DiMPUs endowed the elastomer with excellent healability and diversified recycling pathways9. For example, a dumbbell-shaped DiMPU-Cu1 sample was cut into two pieces and can be nearly fully healed by simple contact at 60 °C in 3 h, recovering 94% of the original tensile strength (Supplementary Fig. 47). Recyclability was demonstrated through a solvent-based casting method, which preserved the mechanical performance over multiple cycles (Supplementary Fig. 48). Alternatively, small pieces of DiMPU-Cu1 could be reprocessed into intact samples via hot pressing at 130 °C for 20 min, with stress-strain curves showing minimal loss in mechanical properties (Supplementary Fig. 49).

Discussion

In summary, we have developed a robust and recyclable PU elastomer through a low-entropy-gain-driven toughening strategy enabled by divergent metal-pyrazole (DiMP) interactions. The DiMPUs exhibit exceptional mechanical properties, achieving an unprecedented 11-fold increase in toughness (310.8 MJ m−3) and a tensile strength of 59.0 MPa compared to non-coordinated polyurethane. The DiMP interactions suppress entropy gain during coordination bond breakage to amplify energy dissipation and concurrently promote the establishment of multiple hydrogen bonds, thus creating a hierarchical energy dissipation mechanism. Furthermore, DiMPUs exhibit closed-loop recyclability through acid-promoted selective hydrolysis of pyrazole-urea bonds and specific protonation of amines, allowing for the efficient monomer recovery and remanufacturing of original materials without compromising mechanical performance. The dynamic nature of pyrazole-urea, coordination, and hydrogen bonds also imparts excellent self-healing and reprocessing capabilities. This work advances the entropy-driven design of high-performance polymers via divergent metal-ligand coordination, offering a sustainable pathway to address critical challenges in plastic waste.

Methods

Synthesis of dipyrazole

Pyrazole (25.0 g, 0.37 mol) and finely powdered KOH (82.3 g, 1.47 mol) were dissolved in DMSO (100 mL) and stirred at 60 °C for 1 h, followed by dropwise addition of dibromomethane (33.0 g, 0.19 mol). After 4 h reaction, the mixture was filtered to remove excess KOH, concentrated by vacuum distillation and extracted with chloroform/H2O. The organic phase was dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated to give 1,1’-methylenedipyrazole. This intermediate was converted to its hydrobromide salt in 48% HBr aqueous solution, then thermally rearranged at 200 °C for 2 h in a sealed tube. The resulting brown solid was dissolved in water, and an aqueous solution of NaOH was added dropwise until the pH reached 12. An off-white precipitate of dipyrazole was formed, which was subsequently filtered and dried under vacuum to obtain the final product.

Synthesis of Di(pyrazole-urea) (DPU) L

Dipyrazole (2.0 g, 13.50 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (30 mL), and n-butyl isocyanate (2.81 g, 28.35 mmol) was added dropwise. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h, after which the solvent was removed under vacuum. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, DCM/EA) to afford DPU L as a white solid.

Synthesis of DiMPUs

PTMG (10 g, 5 mmol) was dehydrated under vacuum at 120 °C for 2 h, followed by addition of HMDI (2.62 g, 10 mmol), DBTDL (0.01 g), and DMAc (40 mL) at 60 °C. The mixture was mechanically stirred for 3 h to form the prepolymer (PTMG-HMDI). A DMAc solution (10 mL) containing dipyrazole chain extender (0.74 g, 5 mmol) was added dropwise, and stirring continued for 3 h. The resulting PPU elastomer was precipitated and washed with methanol and dried under vacuum for 24 h.

For DiMPU-Cux preparation, PPU (1.0 g) was dissolved in THF (10 mL) with stirring for 2 h. CuCl2 (5.03 mg, 0.037 mmol, in 1 mL MeOH) was added and stirred for 2 h. The solution was cast into a PTFE mold, dried at room temperature (24 h), and further vacuum-dried at 50 °C (48 h) to obtain DiMPU-Cu0.1 films. Variants DiMPU-Cu0.2 (10.06 mg CuCl₂), DiMPU-Cu0.5 (25.21 mg CuCl₂), DiMPU-Cu1 (49.75 mg CuCl₂), and DiMPU-Cu2 (100.84 mg CuCl₂) were synthesized analogously.

Synthesis of urethane analog

HMDI (3.94 g, 15 mmol) was dissolved in n-butanol under nitrogen atmosphere. DBTDL (9.47 mg, 0.015 mmol) was added dropwise, and the mixture was stirred at 50 °C for 3 h. After solvent removal under vacuum, the crude product was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, n-hexane/ethyl acetate) to afford the urethane analog as a white solid.

Acid-mediated selective dissolution and reprocessing

A mixture of commercial plastic pieces (PS, PA, PMMA, PVC, PU, PET, ABS, PP, PC, PE) and DiMPU-Cu1 elastomer (200 mg) was placed in a 20 mL cylindrical glass vial. Sulfuric acid aqueous solution (5 M, 10 mL) was introduced, and the system was magnetically stirred at 25 °C for 20 min. Selective dissolution of DiMPU-Cu1 was visually confirmed, while other polymers remained undissolved. The acidic solution containing dissolved DiMPU-Cu1 was separated via vacuum filtration. To recover the polymer matrix, deionized water was added to the filtrate under vigorous stirring, inducing precipitation of PPU. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation and thoroughly washed with deionized water to remove residual Cu2+ ions. The purified PPU was dried under vacuum (70 °C, 48 h) and subsequently redissolved in THF (10 mL). Re-coordination was achieved by adding a methanolic solution of CuCl2 (1 equiv, 1 mL) with stirring. The homogeneous solution was cast into a PTFE mold, and dried at 60 °C (24 h) to obtain reprocessed DiMPU-Cu1 films.

Closed-loop recycling of DiMPU and thermoset polyurea

After copper ions were removed with the same procedures as mentioned above, the purified PPU elastomer (0.1 g) was dissolved in a cylindrical glass vial containing 2 M HCl/EtOH (v/v = 1:5, 10 mL) under vigorous stirring. The homogeneous solution was heated at 70 °C for 36 h to achieve complete chemoselective hydrolysis of pyrazole-urea bonds, yielding a mixture of dipyrazole and macromolecular diamine (H2N-PTMG-NH2). The hydrolysate was neutralized with 2 M NaOH to pH 10, inducing precipitation of dipyrazole and H2N-PTMG-NH2. The solid was collected by filtration. Then the mixture of dipyrazole and H2N-PTMG-NH2 was washed with pH 5 aqueous HCl to remove H2N-PTMG-NH2, and dried under vacuum (70 °C, 12 h) to afford dipyrazole (yield: 85%). The filtrate containing component H2N-PTMG-NH2 was adjusted to pH 10, which induced the precipitation of H2N-PTMG-NH2. The resulting precipitate was then collected via filtration, and dried under vacuum (70 °C, 12 h) to afford H2N-PTMG-NH2 (yield: 87%).

Macromolecular diamine (0.8 g, 0.4 mmol) was reacted with triphosgene (0.15 g, 0.5 mmol) and triethylamine (TEA) in anhydrous dichloromethane (20 mL) at 0 °C for 2 h under N2 and then warming to 25 °C for 12 h, followed by filtration and evaporation to regenerate PTMG-HMDI (isocyanate-terminated prepolymer). The prepolymer was chain-extended with recycled dipyrazole (0.059 g, 0.4 mmol) in DMAc (30 mL) at 60 °C for 3 h, followed by CuCl2 coordination (as described in synthesis of DiMPUs.), yielding reprocessed DiMPU-Cu1 with retained mechanical properties.

The closed-loop recycling of thermosetting polyurea followed a similar protocol: the polyurea was subjected to acidolysis in 2 M HCl/EtOH (v/v = 1:5) at 70 °C for 36 h, yielding a mixture of THDA (trimer of hexamethylene diamine) and dipyrazole. The hydrolysate was neutralized to pH 10, inducing precipitation of both components. After filtration, the solid was washed with HCl aqueous (pH = 5) to isolate pure dipyrazole (yield: 88%), while the filtrate was readjusted to pH 10 to recover THDA by precipitation (yield: 86%). Subsequently, THDA was converted to THDI via reaction with triphosgene and TEA in anhydrous dichloromethane under N2. Finally, repolymerization of THDI with recycled dipyrazole in DMAc at 60 °C for 3 h directly regenerated the thermosetting network.

Data availability

Characterization details and all proton and carbon NMR spectra are provided in the Supplementary Information. The raw experimental data in this study and the Cartesian coordinates of all DFT-optimized structures are available in the Source Data. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Delebecq, E., Pascault, J.-P., Boutevin, B. & Ganachaud, F. On the versatility of urethane/urea bonds: reversibility, blocked isocyanate, and non-isocyanate polyurethane. Chem. Rev. 113, 80–118 (2013).

Liu, W., Yang, S., Huang, L., Xu, J. & Zhao, N. Dynamic covalent polymers enabled by reversible isocyanate chemistry. Chem. Comm. 58, 12399–12417 (2022).

Rossignolo, G., Malucelli, G. & Lorenzetti, A. Recycling of polyurethanes: where we are and where we are going. Green. Chem. 26, 1132–1152 (2024).

Kwon, D. Three ways to solve the plastics pollution crisis. Nature 616, 234–237 (2023).

Cromwell, O. R., Chung, J. & Guan, Z. Malleable and self-healing covalent polymer networks through tunable dynamic boronic ester bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 6492–6495 (2015).

Zhang, Q. et al. Exploring a naturally tailored small molecule for stretchable, self-healing, and adhesive supramolecular polymers. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat8192 (2018).

Zhang, M. et al. Ultra-fast selenol-yne click (SYC) reaction enables poly(selenoacetal) covalent adaptable network formation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202410245 (2024).

Yang, S. et al. Direct and catalyst-free ester metathesis reaction for covalent adaptable networks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 20927–20935 (2023).

Liu, W. et al. Dynamic multiphase semi-crystalline polymers based on thermally reversible pyrazole-urea bonds. Nat. Commun. 10, 4753 (2019).

Choi, C. et al. Digital light processing of dynamic bottlebrush materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2200883 (2022).

Aljuaid, M., Chang, Y., Haddleton, D. M., Wilson, P. & Houck, H. A. Thermoreversible [2 + 2] photodimers of monothiomaleimides and intrinsically recyclable covalent networks thereof. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 19177–19182 (2024).

Obadia, M. M., Mudraboyina, B. P., Serghei, A., Montarnal, D. & Drockenmuller, E. Reprocessing and recycling of highly cross-linked ion-conducting networks through transalkylation exchanges of C–N bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 6078–6083 (2015).

Ma, Y., Jiang, X., Shi, Z., Berrocal, J. A. & Weder, C. Closed-loop recycling of vinylogous urethane vitrimers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202306188 (2023).

Xia, J., Li, T., Lu, C. & Xu, H. Selenium-containing polymers: perspectives toward diverse applications in both adaptive and biomedical materials. Macromolecules 51, 7435–7455 (2018).

Podgórski, M. et al. Toward stimuli-responsive dynamic thermosets through continuous development and improvements in covalent adaptable networks (CANs). Adv. Mater. 32, 1906876 (2020).

Chen, J. et al. Covalent adaptable polymer networks with CO2-facilitated recyclability. Nat. Commun. 15, 6605 (2024).

Fu, D. et al. A facile dynamic crosslinked healable poly(oxime-urethane) elastomer with high elastic recovery and recyclability. Mater. Chem. A 6, 18154–18164 (2018).

Liu, Z. et al. Chemical upcycling of commodity thermoset polyurethane foams towards high-performance 3D photo-printing resins. Nat. Chem. 15, 1773–1779 (2023).

Park, S. B. et al. Development of marine-degradable poly(ester amide)s with strong, up-scalable, and up-cyclable performance. Adv. Mater. 37, 2417266 (2025).

Morado, E. G. et al. End-of-life upcycling of polyurethanes using a room temperature, mechanism-based degradation. Nat. Chem. 15, 569–577 (2023).

Zheng, N., Xu, Y., Zhao, Q. & Xie, T. Dynamic covalent polymer networks: a molecular platform for designing functions beyond chemical recycling and self-healing. Chem. Rev. 121, 1716–1745 (2021).

Jin, Y., Lei, Z., Taynton, P., Huang, S. & Zhang, W. Malleable and recyclable thermosets: the next generation of plastics. Matter 1, 1456–1493 (2019).

Yang, S., Du, S., Zhu, J. & Ma, S. Closed-loop recyclable polymers: from monomer and polymer design to the polymerization–depolymerization cycle. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 9609–9651 (2024).

Zhao, X. et al. Recovery of epoxy thermosets and their composites. Mater. Today 64, 72–97 (2023).

Scheutz, G. M., Lessard, J. J., Sims, M. B. & Sumerlin, B. S. Adaptable crosslinks in polymeric materials: resolving the intersection of thermoplastics and thermosets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 16181–16196 (2019).

Elling, B. R. & Dichtel, W. R. Reprocessable cross-linked polymer networks: are associative exchange mechanisms desirable? ACS Cen. Sci. 6, 1488–1496 (2020).

Van Lijsebetten, F., Debsharma, T., Winne, J. M. & Du Prez, F. E. A highly dynamic covalent polymer network without creep: mission impossible? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202210405 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Healable and recyclable polymeric materials with high mechanical robustness. ACS Mater. Lett. 4, 554–571 (2022).

Sperling L. H. Mechanical behavior of polymers. In: Introduction to Physical Polymer Science (Wiley, 2005).

Chen, X. et al. Enabling high strength and toughness polyurethane through disordered-hydrogen bonds for printable, recyclable, ultra-fast responsive capacitive sensors. Adv. Sci. 11, 2405941 (2024).

Lai, J. et al. Thermodynamically stable whilst kinetically labile coordination bonds lead to strong and tough self-healing polymers. Nat. Commun. 10, 1164 (2019).

Li, C. & Zuo, J. Self-healing polymers based on coordination bonds. Adv. Mater. 32, 1903762 (2020).

Meurer, J. et al. Shape-memory metallopolymers based on two orthogonal metal-ligand interactions. Adv. Mater. 33, 2006655 (2021).

Kang, J., Wang, X. & Sun, J. Engineering of hierarchical phase-separated nanodomains toward elastic and recyclable shock-absorbing fibers with exceptional damage tolerance and damping capacity. ACS Mater. Lett. 7, 2328–2336 (2025).

Liao, S., Zou, W., Wang, X. & Yin, S. Dual cold- and thermal-compatible polyurethane elastomer based on flexible polybutadiene chain and metal-ligand coordination. Eur. Polym. J. 223, 113633 (2025).

Lu X. et al. Designing strong yet tough, multifunctional and printable dynamic cross-linking waterborne polyurethane for customizable smart soft devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 6, 2502720 (2025).

Li, C. H. et al. A highly stretchable autonomous self-healing elastomer. Nat. Chem. 8, 618–624 (2016).

Spegazzini, N., Siesler, H. W. & Ozaki, Y. Activation and thermodynamic parameter study of the heteronuclear C=O…H-N hydrogen bonding of diphenylurethane isomeric structures by FT-IR spectroscopy using the regularized inversion of an eigenvalue problem. Mater. Chem. A 116, 7797–7808 (2012).

Hino, S., Ichikawa, T. & Kojima, Y. Thermodynamic properties of metal amides determined by ammonia pressure-composition isotherms. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 42, 140–143 (2010).

Niu, W., Li, Z., Liang, F., Zhang, H. & Liu, X. Ultrastable, superrobust, and recyclable supramolecular polymer networks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202318434 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Molecularly engineered unparalleled strength and supertoughness of poly(urea-urethane) with shape memory and clusterization-triggered emission. Adv. Mater. 34, 2205763 (2022).

Tan, M. W. M. et al. Toughening self-healing elastomers with chain mobility. Adv. Sci. 11, 2308154 (2024).

Wang, L. et al. Development of tough thermoplastic elastomers by leveraging rigid–flexible supramolecular segment interplays. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202301762 (2023).

Guo, R. et al. Extremely strong and tough biodegradable poly(urethane) elastomers with unprecedented crack tolerance via hierarchical hydrogen-bonding interactions. Adv. Mater. 35, 2212130 (2023).

Jin, Z. et al. Multivalent design of low-entropy-penalty ion–dipole interactions for dynamic yet thermostable supramolecular networks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 3526–3534 (2023).

Qiao, H., Wu, B., Sun, S. & Wu, P. Entropy-driven design of highly impact-stiffening supramolecular polymer networks with salt-bridge hydrogen bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 7533–7542 (2024).

Guo, X. et al. Tough, recyclable, and degradable elastomers for potential biomedical applications. Adv. Mater. 35, 2210092 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. A stretchable, mechanically robust polymer exhibiting shape-memory-assisted self-healing and clustering-triggered emission. Nat. Commun. 14, 4712 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. A highly efficient self-healing elastomer with unprecedented mechanical properties. Adv. Mater. 31, 1901402 (2019).

Ping, Z. et al. Tailoring photoweldable shape memory polyurethane with intrinsic photothermal/fluorescence via engineering metal-phenolic systems. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2402592 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. Fabrication of mechanical strong supramolecular waterborne polyurethane elastomers with the inspiration of hierarchical dynamic structures of scallop byssal threads. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2413083 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Eu-doped polyurethane with efficient multicolor fluorescence, self-healing, stimuli-responsiveness and its diverse applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 202418965 (2025).

Wang, X. & Sun, J. Engineering of reversibly cross-linked elastomers toward flexible and recyclable elastomer/carbon fiber composites with extraordinary tearing resistance. Adv. Mater. 36, 2406252 (2024).

Li, G. et al. Robust and dynamic polymer networks enabled by woven crosslinks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202210078 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. A topological polymer network with Cu(II)-coordinated reversible imidazole-urea locked unit constructs an ultra-strong self-healing elastomer. Sci. China Chem. 66, 853–862 (2023).

Archer, E. A. & Krische, M. J. Duplex oligomers defined via covalent casting of a one-dimensional hydrogen-bonding motif. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 5074–5083 (2002).

Zhang, H. et al. Superstretchable dynamic polymer networks. Adv. Mater. 31, 1904029 (2019).

Krishnakumar, V., Jayamani, N. & Mathammal, R. Molecular structure, vibrational spectral studies of pyrazole and 3,5-dimethyl pyrazole based on density functional calculations. Spectrochim. Acta. A. 79, 1959–1968 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the funding support from Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LY24E030003, W.L.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (52325303, N.Z., 52573142, W.L.). We sincerely appreciate Prof. Xiwei Guo at Wuhan Textile University for his valuable advice on SAXS data analysis and tear testing. L.H. thanks Mr. Yuhao You at Sichuan University for his helpful discussions. W.L. acknowledges Zhejiang University for startup funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.L. conceived the idea. L.H., J.X., and W.L. designed and carried out the experiments and analyzed the data. Z.J., X.H., and X.C. assisted with discussions of experimental data. L.H., J.X., and W.L. wrote the manuscript. N.Z., C.G., and W.L. supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jiheong Kang and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, L., Xia, J., Jin, Z. et al. Entropy-driven toughening and closed-loop recycling of polymers via divergent metal-pyrazole interactions. Nat Commun 16, 10673 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65700-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65700-4