Abstract

Owing to increasing concerns regarding climate change, research concerning the use of plant biomass as a renewable carbon resource has become increasingly active. Phenylpropanoids, which are aromatic compounds derived from plants, offer renewable sources owing to their availabilities and structural diversity. This study presents an approach for use in producing decomposable polymers with high biomass contents via [2 + 2] cycloaddition polymerization. Bifunctional monomers with silyl ether-linked phenylpropanoids were synthesized, and their polymerizations were investigated using chemical and electro- and photochemical methods. The resulting polymers contained aromatic and cyclobutane rings and silyl ether bonds in their backbones, which enhanced their thermal properties. Notably, these polymers could be decomposed via Diels-Alder reactions at the cyclobutane rings or Si–O bond cleavage, facilitating chemical re- and upcycling. Here, we show a sustainable method of producing high-biomass decomposable polymers, potentially contributing in reducing plastic waste and promoting a circular economy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The efficient use of renewable plant biomass resources in polymeric materials is urgently required to halt anthropogenic carbon emissions from petroleum-derived raw materials1,2,3,4,5. Biomass resources derived from wood and plants display potential as sufficient carbon sources to replace raw petroleum materials because of their levels of abundance. Phenylpropanoids are natural aromatic organic compounds extracted from plants, such as anise, ylang-ylang, and clove, as essential oils. Because of their availabilities and structural diversity, they are widely used in spices, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical derivatives6,7,8,9, and the worldwide market for essential oils reached USD 10 billion in 202110. In addition, considerable efforts have been devoted to generating phenylpropanoids directly or indirectly from inedible woody biomass, such as lignin, facilitating its use as a renewable source of raw materials11,12,13,14.

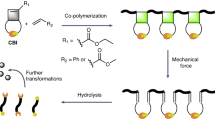

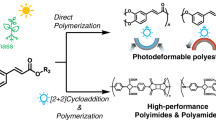

In this context, the polymerization of phenylpropanoids has been extensively investigated for decades. The reactivities of the vinyl groups of phenylpropanoids are generally low owing to the steric hindrance of their 1,2-disubstituted frameworks. Therefore, the homopolymerization of phenylpropanoids has been a long-standing challenge in this field, and their copolymerization with other reactive monomers, such as styrene and methyl acrylate, has been widely studied15,16,17,18. Recently, progress was reported in the homopolymerization of phenylpropanoids19,20,21,22,23, generating polymers with high contents of biomass-derived components. However, even with state-of-the-art polymerization techniques, only a handful of polymers with high phenylpropanoid contents, e.g., >65 wt.% phenylpropanoids, have been reported. In addition, most reported phenylpropanoid-containing polymers exhibit polystyrene-type backbones polymerized via addition at the vinyl moiety, which limits the applicability and recyclability of phenylpropanoids (Fig. 1A). Notably, Labrie-Cleary et al. recently reported the synthesis of photodegradable polymers via the homopolymerization of o-hydroxycinnamic acid. However, the resulting material faces limitations in chemical recyclability, as the decomposition products are not readily reusable23.

A Previous studies regarding the conversion of biomass-derived phenylpropanoids to polymer materials. B Precedents of [2 + 2] cycloaddition and polymerization as a method of efficiently polymerizing phenylpropanoids. C Strategy applied in synthesizing biomass-derived decomposable polymers using phenylpropanoids in this study. D Energy diagram for [2 + 2] cycloaddition polymerization.

To develop decomposable polymers with high phenylpropanoid contents, [2 + 2] cycloaddition reaction represents a promising strategy, as the reactivity of multiply substituted olefins in this transformation is well established24. Since [2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions hardly proceed under thermal conditions, they are generally induced via single electron transfer (SET)-triggered reactions using chemical reagents25,26,27,28, electrolysis29,30,31, and photoredox catalysis32,33,34, and the photochemical reactions based on energy transfer using photosensitizers (Fig. 1B)35,36,37. Indeed, Bauld et al. reported the [2 + 2] cycloaddition polymerization of diolefins bearing electron-rich aromatic rings via SET-triggered hole-catalytic cycloaddition (Fig. 1B)38,39. Although their study introduced a unique polymerization mechanism, the polymers reported by them were neither derived from biomass resources nor designed to be chemically decomposable, thereby limiting their relevance to sustainable polymer development. Regarding the photocatalytic cycloaddition pathway, Oshimura et al. reported the synthesis of a bifunctional cyclobutane-containing monomer from a caffeic acid derivative via [2 + 2] cycloaddition reaction and subsequently reacted it with tetraethylene glycol to produce biomass-derived polyester40. Although they have also succeeded in hydrolysis of the resulting polyester, strong acidic or basic conditions and/or heating are typically required for hydrolysis. From the perspective of environmental impact, it seems necessary to design polymers that can be decomposed under milder conditions.

In this study, we report phenylpropanoid-containing polymers with high biomass contents and decomposability via [2 + 2] cycloaddition polymerization (Fig. 1C). Bifunctional monomers containing two phenylpropanoids connected via silyl ether linkages are synthesized, and polymerizations are performed using chemical, electrochemical, and photochemical methods. The polymer design comprises aromatic, cyclobutane, and silyl ether groups in the main chain. The aromatic rings improve the mechanical and thermal properties, whereas the cyclobutane groups provide a high thermal stability due to the thermally unfavorable nature of the retro-[2 + 2] reaction. The Si–O bonds of the silyl ether linkages display higher bond dissociation energies (108 kcal mol−1) than that of the Csp3–Csp3 bond (83 kcal mol−1), rendering the polymer chemically and thermally stable. In addition to their robustness, the polymers developed in this study exhibit unique dual decomposition capacities under mild conditions (Fig. 1C). A radical cationic cyclobutane ring is known to be in equilibrium with two olefins, the precursor of the [2 + 2] cycloaddition32,41. Therefore, the cyclobutane ring enables a hole-catalytic Diels-Alder reaction in the presence of a diene, enabling an unprecedented mode of polymer decomposition32. In addition, the polymers reported herein can be decomposed via reaction with fluoride anions at the Si–O bonds to yield bisphenol products. The resulting bisphenols can be used in chemical re- and upcycling to produce value-added products42,43,44. In general, [2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions between unactivated substrates have high activation energies and do not proceed. However, by activating substrates by one-electron oxidation or energy transfer, the activation energy is reduced, and cycloaddition reaction proceeds (Fig. 1D). Overall, this study proposes a design concept for use in fabricating biomass-derived decomposable polymeric materials with unique main-chain structures, potentially contributing to the sustainable, circular use of carbon resources.

Results

Monomer synthesis

First, we attempted to synthesize monomers comprising bisphenylpropanoids connected by silyl ether bonds. The condensation reactions of the phenylpropanoids and dialkyldichlorosilanes were performed at 25 °C in the presence of triethylamine as the base and a catalytic amount of 4-dimethylaminopyridine. We first examined the influences of the substituents on the silicon atom (Table S1). Sterically unhindered substituents lead to destabilization of the resulting monomers, whereas sterically hindered dialkyldichlorosilanes did not react with phenylpropanoids. The reaction between the phenylpropanoids and dichlorodiisopropylsilane proceeded smoothly, affording the desired stable monomers M1–M6 in high yields (Fig. S1).

Hole-catalytic polymerization using a chemical oxidant

The silyl ether linkages of M1–M6 increase the electron densities in the aromatic rings because of the small electronegativity of the silicon atoms compared to carbon and oxygen atoms, and thus, these monomers may be compatible with the hole-catalytic cycloaddition polymerization initiated via SET. The hole-catalytic cycloaddition polymerization explored by Bauld et al. mostly relied on the use of a catalytic amount of the chemical oxidant magic blue (MB). Thus, we first examined the polymerization of M1 using MB.

MB addition to a solution of M1 resulted in an immediate color change from blue to orange, suggesting a smooth SET between MB and M1. However, reprecipitation afforded a significant amount of an insoluble gel. A small amount of the soluble fraction was subjected to gel permeation chromatography (GPC), which suggested the formation of a polymer of >100 kDa (Fig. S5). Thus, MB induced cross-linking via cationic polymerization at the vinyl groups, in addition to the desired cycloaddition polymerization (Table S3), as observed for specific monomers in a previous study45.

Inspired by recent progress in hole-catalytic [2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions using hypervalent iodine in small-molecule synthesis26,46, we changed the oxidant from MB to iodobenzene diacetate (PIDA). M1 was polymerized by adding 50 mol.% PIDA in 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) at 25 °C (Fig. 2A). After purifying the crude product via reprecipitation, P1 was obtained as a white powder in a 54% yield without the formation of an insoluble product. GPC revealed that the number- (Mn) and weight-average molecular weights (Mw) of P1 were 3300 and 6200, respectively, and its polydispersity index (PDI) was 1.90 (Fig. 2B). Comparing the 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra of M1 and P1 suggested that the signals representing the olefin protons of M1 were mostly diminished after the reaction. This is concomitant with the manifestation of the signals representing methine protons, which are characteristic of the cyclobutane rings of P1 (Fig. 2C). In addition, the signals representing the terminal olefin protons of P1 were observed at the same positions as those of M1 (\(\delta\) = 6.0–6.5). The molecular weight of P1 estimated from the 1H NMR was 3600 Da, corresponding to ca. 9.5 repeating units, showing a good agreement with the results of GPC measurement (Fig. S15). From these data, it is suggested that M1 polymerization proceeds via the formation of cyclobutane rings via [2 + 2] cycloaddition to yield P1. The content of biomass-derived ingredients in P1 is 69 wt.%, which is higher than most of the reported polymers synthesized from phenylpropanoid by copolymerization with other non-biomass vinyl monomers.

A Schematic of hole-catalytic polymerization via chemical oxidation using 50 mol.% PIDA as a chemical oxidant. B GPC traces (in THF) and C 1H NMR spectra (in CDCl3) of M1 and P1. D Time course of conversion using 0.1 M M1, as initiated by PIDA. E Relationship between the conversion of M1 and number-average molecular weight (Mn) of P1. The green line represents the experimental data, and the dark/light gray dotted lines represent the theoretical lines of living/stepwise polymerization, respectively. F Schematic of hole-catalytic polymerization via electrochemical oxidation using 50 mol.% tris(4-bromophenyl) amine as a redox mediator (TsO− = p-toluenesulfonate, TfO− = trifluoromethanesulfonate, TFSI− = bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide). G Images of the solutions with different electrolytes during electrolysis. H Schematic of photocatalytic [2 + 2] cycloaddition polymerization via energy transfer. I Results of photocatalytic [2 + 2] cycloaddition polymerization using the monomers. J Time course of conversion using 0.77 M M4. K Relationship between the conversion of M4 and Mn of P4. Me methyl, Et ethyl, Ph phenyl.

To gain insight into the polymerization mechanism, the relationship between the conversion of M1 and Mn was investigated. A time-trace experiment revealed that 62% of M1 was consumed within 1 min of PIDA addition (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, Mn exhibited almost no correlation with M1 conversion (Fig. 2E). These data strongly suggest that the reaction proceeded via a chain-growth mechanism with a termination reaction. Intramolecular transfer of a radical cation on the cyclobutane ring after [2 + 2] cycloaddition reaction or back electron transfer from a neutral monomer or polymer would lead to a propagating reaction, but other termination reactions would occur during the reaction. It should be noted that both M1 and P1 can potentially be involved in the propagating reaction by SET, since there was little difference in their oxidation potentials (Fig. S3).

To further investigate the competition between chain propagation and termination reactions, we performed polymerization of M1 with various conditions. The concentration of M1 had minimal impact on the molecular weight of P1 (Tables S4 and S5), whereas increasing the equivalents of PIDA significantly raised the molecular weight (Tables S5–S7). This is presumably because increasing amount of PIDA promoted reoxidation of the polymer chain ends even after swift termination reaction. The plausible mechanism of hole-catalytic polymerization based on these findings is presented in Fig. S10.

Contrasting to the result of M1, the polymerizations of the other monomers (M2–M6) hardly progressed under these conditions (Table S14). Cyclic voltammetry (CV) study of M1–M6 revealed that the oxidation potentials of M2–M6 are higher than that of M1 (Fig. S2), suggesting that the alkene moieties with electron-withdrawing groups, such as ketone or ester, render the monomers less susceptible to SET oxidation. The order of the oxidation potentials of M1–M6 matched with the order of HOMO energy levels estimated by DFT calculations (Table S2).

Hole-catalytic polymerization via electrolysis

We then investigated electrochemical hole-catalytic cycloaddition polymerization. First, the electrochemical polymerization of M1 was performed via direct oxidation on the anode surface. However, a passivation film was formed immediately, which hampered further electrolysis. To avoid passivation, electrolysis was performed using the redox mediator tris(4-bromophenyl) amine (Fig. 2F). Remarkably, the progress of the polymerization reaction was sensitive to the nature of the anionic species in the supporting electrolyte. The use of the weakly coordinating anion B(C6F5)4− was strikingly effective, and the desired polymer was obtained in an 80% yield (Table S13). When Bu4NB(C6F5)4 (Bu = n-butyl) was used as the supporting electrolyte, the color of the reaction solution remained blue, which was derived from the radical cationic state of the mediator, whereas more coordinating electrolytes turned the solution orange (Fig. 2G). This suggests that the weakly coordinating electrolyte solution keeps radical cationic cyclobutane intact47, and back electron transfer from the mediator is promoted. It is noteworthy that the use of tris(4-bromophenyl) amine mediator successfully afforded the desired polymer by electrolysis, even though the aforementioned hole-catalysis by using MB induced uncontrolled cationic polymerization. This is presumably due to the slow generation of oxidant by electrochemical reaction was preferable compared to the rapid addition of oxidant in chemical oxidation reaction.

Meanwhile, the electrochemical polymerizations of M2–M6 hardly progressed as in the case of chemical oxidants, even in using tris(2,4-dibromophenyl) amine, which has a higher oxidation potential than tris(4-bromophenyl) amine (Figs. S2 and S11). This is presumably due to the lack of nucleophilicity of the monomers and/or difficulty in the back electron transfer, making it difficult to proceed with a hole-catalytic [2 + 2] cycloaddition polymerization.

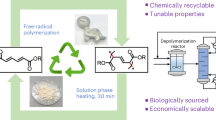

Photocatalytic polymerization via energy transfer

Several studies report the [2 + 2] cycloaddition of carbonyl-substituted olefins, including several phenylpropanoids, such as chalcone and cinnamate, under photocatalysis via an energy transfer mechanism35,36,37. Inspired by these precedents, we investigated the polymerizations of M1–M6 under photocatalytic conditions (Fig. 2H). Blue light was irradiated for 60 h in the presence of 1 mol.% of the (4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine)bis[3,5-difluoro-2-[5-(trifluoromethyl)−2-pyridinyl]phenyl]iridium(III) hexafluorophosphate (Ir-F) photocatalyst. No polymer products were obtained using M1, whereas the polymerizations of M2–M6 proceeded to afford the corresponding polymers P2–P6 in high yields (Fig. 2I). The biomass contents of the resulting polymers are 73–79 wt.%. Based on the previous reports, the successful progress of polymerization for M2–M6 was attributed to the presence of carbonyl groups adjacent to the olefins, stabilizing the triplet states36.

Although the failure of polymerization of M1 is reasonable due to the absence of a carbonyl group adjacent to the olefin moiety, the polymerization of M1 via hole-catalytic mechanism with Ir-F as a photoredox catalyst seemed reasonable. However, no polymerization was observed under these conditions as mentioned above. We attributed this outcome to the modest oxidizing power of Ir-F (E1/2 = +1.21 V vs. SCE)48, which is not strong enough to oxidize M1. In fact, when we employed [Ru(bpz)3][B(C6F5)4]2 (bpz = 2,2′-bipyrazine), a photocatalyst with a higher oxidation potential (E1/2 = +1.45 V vs. SCE)32,48, P1 was successfully obtained via photochemically driven hole-catalytic polymerization of M1 (Table S8).

We then investigated the mechanism of photocatalytic polymerization using M4. The conversion of M4 exceeded 75% within 10 min of initiating the reaction, indicating a favorable reaction rate (Fig. 2J, Table S21). In contrast, Mn of P4 continued to increase even after the conversion of M4 had plateaued (Fig. 2K), indicating a behavior distinct from that observed in the hole-catalytic polymerization. This relationship indicates that photocatalytic polymerization proceeds via a stepwise mechanism.

P2–P6 showed notably larger PDI values compared to P1. This is presumably due to the difference in polymerization mechanism. Also, the possibility of forming cyclic polymers by [2 + 2] cycloadditions between terminal olefins cannot be ruled out. In fact, most of the terminal olefin protons of photopolymerized polymers are not observed in the 1H NMR spectra.

Thermal properties

The thermal properties of the resulting polymers were evaluated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Their 5% mass loss temperatures (Td5) are in the range 139–341 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere (Fig. 3A, B, D). The Td5 generally depends on the substituents, particularly those on the alicyclic structures of the main chain, with the following order of thermal stability: –CH3 (P1) > –COO (P4, P5) > –CO (P2, P3, P6).

A Structures of P1–P6. B Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) thermograms of P1–P6. C Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) thermograms of P1–P6. Heat flow is shown in the endothermic down direction. D Thermal properties of each polymer. Polymerization conditions, P1: 0.096 mM M1 in HFIP initiated by 100 mol.% PIDA at 25 °C for 60 min. P2 and P4–P6: 0.384 M monomer in acetonitrile (MeCN) catalyzed by 1 mol.% of the Ir-F photocatalyst at 25 °C for 60 h. P3: 0.384 M M3 in MeCN catalyzed by 1 mol.% of the Ir-F photocatalyst at 25 °C for 17 h.

The polymers prepared in this study exhibit relatively high glass transition temperatures (Tg) in the range 8–68 °C compared to polymers bearing silyl ether groups (Fig. 3A, C, D). The rigid framework formed by including the alicyclic structures within the main chain may improve Tg49. In addition, not only the alicyclic structures, but also aromatic rings improve rigidities of the polymers. Tg was the highest for P6, which contains the largest number of aromatic rings in its structure. Silyl ether polymers generally display relatively low Tg values owing to their flexible silyl ether bonds with high internal degrees of freedom, and Tg values of <0 °C have been reported43,44,50. Additionally, the methoxy group, as a substituent on the aromatic ring, significantly affects Tg. The polymers without methoxy groups on their aromatic rings (P1, P2, P4, and P6) exhibit relatively high Tg values.

The polymers display high thermal stabilities owing to their backbone groups, such as aromatic rings, alicyclic structures, and silyl ether bonds. These results also suggest that the thermal properties of these materials can be tuned by modifying their polymer backbones and substituents. Notably, cyclobutane rings are known for their high distortion energies, and they are thus susceptible to bond cleavage under mechanochemical conditions51. The counterintuitively high thermal stabilities should be attributed to the thermally unfavorable [2 + 2] cycloaddition, and thus, the reverse reaction, i.e., the retro-[2 + 2] reaction, is difficult to proceed thermally either.

Polymer decomposition

Then, decomposability of P1–P6 was evaluated. First, a decomposition method involving Diels-Alder reactions at the cyclobutane rings was investigated. According to the reaction conditions reported by Yoon et al.32, [Ru(bpz)3][B(C6F5)4]2 and isoprene were added to reaction solution containing P1, and the reaction was performed under white light (Fig. 4A). We have also independently synthesized possible Diels-Alder decomposition product, D1, for characterization by GPC and 1H NMR (see Supplementary Information for details). The GPC trace of the reaction mixture confirmed the decrease in the molecular weight of the polymer, and the formation of small molecular fragment overlapping to D1 was confirmed (Fig. 4B). 1H NMR spectroscopy of the crude mixture after the reaction revealed signals representing the target product D1. In addition, the peak of P1 was not observed in the 1H NMR spectrum, indicating that the polymer backbone was completely decomposed (Fig. 4C). The calculated 1H NMR yield of D1 was 63% compared to an internal standard. This decomposition approach has an excellent atomeconomic advantage, and the resulting D1 is expected to be used as an epoxy resin through epoxidation of olefins52,53.

The yields were determined via 1H NMR spectroscopy of the crude reaction mixtures relative to the internal standard 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene. Scheme (A), GPC traces (in THF) (B), and 1H NMR spectrum (in CDCl3) of the reaction mixture (C) of the Diels-Alder decomposition of P1 using isoprene. Scheme (D) and GPC traces (in THF) (E) of decomposition via Si–O bond cleavage with Bu4NF, and the 1H NMR spectra of B1–B6 (F). The coupling constants of the adjacent vicinal protons of the methine groups of B1–B6 are noted. THF tetrahydrofuran.

Subsequently, we performed polymer decomposition involving the cleavage of the Si–O bonds at the linker moieties. Fluoride anions can readily cleave silyl ether bonds under mild conditions, driven by the formation of strong Si–F bonds42,43,54. Exploiting this property, the decomposition reactions of P1–P6 were conducted by adding 2 equiv. of Bu4NF relative to the numbers of silyl ether bonds of the polymers (Fig. 4D). GPC of the reaction solutions detected no high-molecular-weight species, indicating that the polymer backbones were completely decomposed (Figs. 4E and S20). 1H NMR spectroscopy confirmed that the decomposition products of P1–P6 corresponded to the respective bisphenols B1–B6, which were produced in high yields (Fig. 4F).

This decomposition also confirmed the regio- and stereoselectivities of the substituents on the cyclobutane rings. Generally, [2 + 2] cycloadditions produce isomers with different regioselectivities, such as head-to-head or -tail, and stereoselectivities, such as anti or syn, depending on the reaction method used55,56,57,58,59. Regarding the regioselectivity, the coupling pattern of the signals representing the methine protons of the cyclobutane rings changes significantly from head-to-head to head-to-tail. The head-to-head mode exhibits higher-order coupling, whereas the head-to-tail mode does not exhibit such signals60,61. The 1H NMR spectra of the decomposition products revealed higher-order coupling within B1–B6, indicating that head-to-head is the predominant structure of each decomposition product. More significantly, in the case of head-to-head coupling, the coupling constant of the signal representing the methine protons differs depending on the stereochemistry, i.e., anti or syn. The general coupling constant of the anti or syn conformation with an adjacent vicinal proton is approximately 9 or 6 Hz, respectively51,55,56. The coupling constants of B1–B6 were in the range 9.0–9.8 Hz, indicating that the anti-isomer is predominant in each case (Fig. 4F). The signals representing head-to-head syn-type products were also observed in the 1H NMR spectrum of B4, and the anti:syn diastereoselectivity was 10:3. In contrast, detailed stereochemical assignments were challenging across the entire polymer series due to significant signal broadening. Nevertheless, within analyzable regions, we observed vicinal coupling constants of approximately J ~ 9 Hz (Fig. S17).

Chemical re- and upcycling

Biomass-derived bisphenols, which are the products obtained via the cleavage of the linker moieties, display potential for use as bifunctional monomers in chemical re- and upcycling. As a proof-of-concept, B1 was reacted with a stoichiometric amount of dichlorodiisopropylsilane, and condensation polymerization was performed, resulting in the successful formation of recycled P1 (Fig. 5A). The molecular weight of recycled P1 was almost identical to that of the original P1, demonstrating that the material can be depolymerized and repolymerized without significant loss of structural integrity. Furthermore, polyurethanes and epoxy-cured products were synthesized using B1. The reaction of B1 with 4,4′-methylenebis(phenyl isocyanate) (MDI) afforded the corresponding polyurethane (Fig. 5B). The reaction of epichlorohydrin with B1 afforded epoxide E1 in a 51% yield (Fig. 5C). Subsequently, two types of epoxy-cured resins were synthesized by adding amine curing agents (Fig. 5D). Therefore, the bisphenol products obtained via the decomposition of silyl ether-linked polymers can be easily recycled to form the original polymers and upcycled to generate various value-added polymers.

A Repolymerization to yield P1 by adding 1 equiv. of dichlorodiisopropylsilane. B Synthesis of polyurethane via reaction with 4,4′-methylenebis(phenyl isocyanate) in the presence of 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane. C Epoxidation of B1 via reaction with epichlorohydrin. D Curing reactions of epoxide E1 with curing agents, such as 4,4′-methylenebis(cyclohexylamine) and isophoronediamine, to yield thermoset networks.

Discussion

In this study, phenylpropanoid-derived decomposable polymers with high biomass contents of 69–79 wt.% were successfully developed. By synthesizing bifunctional monomers linked via silyl ethers and employing cycloaddition polymerization, polymers with unique combinations of aromatic, cyclobutane, and silyl ether groups in their backbones were synthesized. These polymers exhibited excellent thermal properties attributed to their robust structural components. Furthermore, the polymers underwent efficient dual decomposition via Diels-Alder reactions at the cyclobutane rings and Si–O bond cleavage facilitated by fluoride anion, enabling chemical re- and upcycling. This dual decomposability offers a significant advantage in sustainable polymer applications by enabling the decomposition and repurposing of the materials under mild conditions. These findings provide a promising pathway for the development of sustainable polymeric materials using renewable resources, addressing the urgent need to reduce our dependence on petroleum-based polymer materials. This study not only advances the field of biomass-derived polymers but also contributes to environmental sustainability by promoting the circular use of carbon resources. Further increase in molecular weight would be required for practical use, which is currently undergoing in our group. Future research can build on these results to explore further applications and the optimization of these materials.

Methods

General procedure for cycloaddition polymerization via chemical oxidation

In a 5 mL vial, a single-electron oxidant dissolved in half the required amount of solvent was added dropwise to the monomer (0.25 mmol) dissolved in the other half of the solvent, while under a nitrogen atmosphere using a balloon. The reaction mixture was stirred for 60 min at a specified temperature and then quenched with methanol. After the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, the crude polymer was purified via reprecipitation (dichloromethane:methanol = 1 mL:20 mL), dissolved in THF at a concentration of 2 mg mL−1, and characterized using GPC and NMR.

General procedure for cycloaddition polymerization via electrochemical oxidation

The reaction was performed in an undivided cell with glassy carbon plates (0.8 × 2 cm) as the anode and cathode, using the ElectraSyn 2.0 Package (IKA, Staufen, Germany). The electrodes were polished using 0.1 and 1 µm alumina and rinsed with deionized water and acetone before the reaction. A solution of the supporting electrolyte was prepared in dichloromethane (0.1 M, 3 mL). After dissolving 0.288 and 0.144 mmol of the monomer and redox mediator, respectively, electrolytic polymerization was performed at room temperature with the application of a constant current. After completion of the reaction, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude polymer was purified via reprecipitation (dichloromethane:methanol = 1.5 mL:30 mL), dissolved in THF at a concentration of 2 mg mL−1, and characterized using GPC and NMR.

General procedure for cycloaddition polymerization using the photoredox catalyst

In a 5 mL vial, the photocatalyst dissolved in half the required amount of solvent was added dropwise to the monomer (0.25 mmol) dissolved in the other half of the solvent. The reaction mixture was stirred for a defined period under visible or blue light. After the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, the crude polymer was purified via reprecipitation (P2–P5, dichloromethane:hexane = 1 mL:20 mL; P1 and P6: dichloromethane:methanol = 1 mL:20 mL), dissolved in THF at a concentration of 2 mg mL−1, and characterized using GPC and NMR.

Procedure for Diels-Alder decomposition

Ru(bpz)3[B(C6F5)4]2 (2.9 mg, 1 mol.% relative to the cyclobutane rings of P1), P1 (57 mg) dissolved in dichloromethane/1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) (v/v = 1/1, 4.7 mL), and isoprene (0.3 mL) were added to a vial bottle, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 60 h under white light. After completion of the reaction, the dichloromethane and isoprene were removed under reduced pressure. 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene was then added as an internal standard, and the product was dissolved in deuterated chloroform to calculate the NMR yield of D1.

General procedure for the decomposition at the silyl ether linkage

Two equivalents (relative to the repeating unit of the polymer) of TBAF were added to a solution of the polymer in THF (10 mM repeating units) in the presence of 2 equiv. of acetic acid. The decomposition reaction was conducted by stirring the mixture at room temperature for several hours. After the evaporation of the solvent and vacuum drying, 1 equiv. (relative to the repeating unit of the polymer) of 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene was added as an internal standard, and the sample was dissolved in the appropriate deuterated solvent. The NMR yields of B1–B6 were determined using the integral value(s) of their methine groups as an index.

Data availability

The experimental and computational data generated in this study are provided in the article and the Supplementary Information, and are also available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Isikgor, F. H. & Becer, C. R. Lignocellulosic biomass: a sustainable platform for the production of bio-based chemicals and polymers. Polym. Chem. 6, 4497–4559 (2015).

Zhu, Y., Romain, C. & Williams, C. K. Sustainable polymers from renewable resources. Nature 540, 354–362 (2016).

Wang, Z., Ganewatta, M. S. & Tang, C. Sustainable polymers from biomass: bridging chemistry with materials and processing. Prog. Polym. Sci. 101, 101197 (2020).

Takeshima, H., Satoh, K. & Kamigaito, M. Bio-based vinylphenol family: synthesis via decarboxylation of naturally occurring cinnamic acids and living radical polymerization for functionalized polystyrenes. J. Polym. Sci. 58, 91–100 (2020).

Datta, J. & Głowińska, E. Effect of hydroxylated soybean oil and bio-based propanediol on the structure and thermal properties of synthesized bio-polyurethanes. Ind. Crops Prod. 61, 84–91 (2014).

Kfoury, M. et al. Essential oil components decrease pulmonary and hepatic cells inflammation induced by air pollution particulate matter. Environ. Chem. Lett. 14, 345–351 (2016).

Carvalho, A. A., Andrade, L. N., de Sousa, ÉB. V. & de Sousa, D. P. Antitumor phenylpropanoids found in essential oils. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 392674 (2015).

Wang, C. et al. Biomass materials derived from anethole: conversion and application. Polym. Chem. 11, 954–963 (2020).

Kumar, N. & Pruthi, V. Potential applications of ferulic acid from natural sources. Biotechnol. Rep. 4, 86–93 (2014).

Bizzo, H. R. & Rezende, C. M. The market of essential oils in Brazil and in the world in the last decade. Quim. Nova 45, 949–958 (2022).

Cheng, L. et al. Selective activation of C–C bonds in lignin model compounds and lignin for production of value-added chemicals. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 9, 433–464 (2024).

Sun, Z., Fridrich, B., de Santi, A., Elangovan, S. & Barta, K. Bright side of lignin depolymerization: toward new platform chemicals. Chem. Rev. 118, 614–678 (2018).

Chen, S., Yan, P., Yu, X., Zhu, W. & Wang, H. Conversion of lignin to high yields of aromatics over Ru–ZnO/SBA-15 bifunctional catalysts. Renew. Energy 215, 118919 (2023).

Zhang, B. et al. Cleavage of lignin C-O bonds over a heterogeneous rhenium catalyst through hydrogen transfer reactions. Green Chem. 21, 5556–5564 (2019).

Terao, Y., Satoh, K. & Kamigaito, M. Controlled radical copolymerization of cinnamic derivatives as renewable vinyl monomers with both acrylic and styrenic substituents: reactivity, regioselectivity, properties, and functions. Biomacromolecules 20, 192–203 (2019).

Lena, J.-B., van Herk, A. M. & Jana, S. Effect of anethole on the copolymerization of vinyl monomers. Polym. Chem. 11, 5630–5641 (2020).

Braun, D. & Hu, F. Polymers from non-homopolymerizable monomers by free radical processes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 31, 239–276 (2006).

Satoh, K. Controlled/living polymerization of renewable vinyl monomers into bio-based polymers. Polym. J. 47, 527–536 (2015).

Hulnik, M. I., Kuharenko, O. V., Vasilenko, I. V., Timashev, P. & Kostjuk, S. V. Quasiliving cationic polymerization of anethole: accessing high-performance plastic from the biomass-derived monomer. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 6841–6854 (2021).

Hulnik, M. I., Kuharenko, O. V., Timashev, P., Vasilenko, I. V. & Kostjuk, S. V. AlCl3 × OPh2-co-initiated cationic polymerization of anethole: facile access to high molecular weight polymers under mild conditions. Eur. Polym. J. 165, 110983 (2022).

Imada, M., Takenaka, Y., Hatanaka, H., Tsuge, T. & Abe, H. Unique acrylic resins with aromatic side chains by homopolymerization of cinnamic monomers. Commun. Chem. 2, 109 (2019).

Hirano, T. et al. Cationic Homopolymerization of trans-anethole in the presence of solvate ionic liquid comprising LiN(SO2CF3)2 and Lewis bases. Polymer 246, 124780 (2022).

Baker, M. S., Roque, J., Burley, K. S., Phelps, B. J. & Labrie-Cleary, C. F. Development of a photo-degradable polyester resulting from the homopolymerization of o-hydroxycinnamic acid. Mater. Today Commun. 31, 103280 (2022).

Poplata, S., Tröster, A., Zou, Y. Q. & Bach, T. Recent advances in the synthesis of cyclobutanes by olefin [2 + 2] photocycloaddition reactions. Chem. Rev. 116, 9748–9815 (2016).

Yu, Y., Fu, Y. & Zhong, F. Benign catalysis with iron: facile assembly of cyclobutanes and cyclohexenes: via intermolecular radical cation cycloadditions. Green Chem. 20, 1743–1747 (2018).

Colomer, I., Barcelos, R. C. & Donohoe, T. J. Catalytic hypervalent iodine promoters lead to styrene dimerization and the formation of tri- and tetrasubstituted cyclobutanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 4748–4752 (2016).

Horibe, T., Katagiri, K. & Ishihara, K. Radical-cation-induced crossed [2+2] cycloaddition of electron-deficient anetholes initiated by iron(III) salt. Adv. Synth. Catal. 362, 960–963 (2020).

Shin, J. H., Seong, E. Y., Mun, H. J., Jang, Y. J. & Kang, E. J. Electronically mismatched cycloaddition reactions via first-row transition metal, iron(III)-polypyridyl complex. Org. Lett. 20, 5872–5876 (2018).

Chiba, K., Miura, T., Kim, S., Kitano, Y. & Tada, M. Electrocatalytic intermolecular olefin cross-coupling by anodically induced formal [2+2] cycloaddition between enol ethers and alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 11314–11315 (2001).

Okada, Y., Nishimoto, A., Akaba, R. & Chiba, K. Electron-transfer-induced intermolecular [2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions based on the aromatic ‘redox tag’ strategy. J. Org. Chem. 76, 3470–3476 (2011).

Rybicka-Jasińska, K., Szeptuch, Z., Kubiszewski, H. & Kowaluk, A. Electrochemical cycloaddition reactions of alkene radical cations: a route toward cyclopropanes and cyclobutanes. Org. Lett. 25, 1142–1146 (2023).

Ischay, M. A., Ament, M. S. & Yoon, T. P. Crossed intermolecular [2 + 2] cycloaddition of styrenes by visible light photocatalysis. Chem. Sci. 3, 2807–2811 (2012).

Riener, M. & Nicewicz, D. A. Synthesis of cyclobutene lignans via an organic single electron oxidant-electron relay system. Chem. Sci. 4, 2625–2629 (2013).

Li, R. et al. Photocatalytic regioselective and stereoselective [2 + 2] cycloaddition of styrene derivatives using a heterogeneous organic photocatalyst. ACS Catal. 7, 3097–3101 (2017).

Lei, T. et al. General and efficient intermolecular [2+2] photodimerization of chalcones and cinnamic acid derivatives in solution through visible-light catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 15407–15410 (2017).

Daub, M. E. et al. Enantioselective [2+2] cycloadditions of cinnamate esters: generalizing lewis acid catalysis of triplet energy transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 9543–9547 (2019).

Pagire, S. K., Hossain, A., Traub, L., Kerres, S. & Reiser, O. Photosensitised regioselective [2+2]-cycloaddition of cinnamates and related alkenes. Chem. Commun. 53, 12072–12075 (2017).

Bauld, N. L., Aplin, J. T., Yueh, W., Sarker, H. & Bellville, D. J. Cation radical polymerization. A fundamentally new polymerization mechanism. Macromolecules 29, 3661–3662 (1996).

Bauld, N. L., Gao, D. & Aplin, J. T. Cation radical chain cycloaddition polymerization: a fundamentally new polymerization mechanism. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 12, 808–818 (1999).

Abe, K., Oshimura, M., Kawatani, R., Hirano, T. & Ute, K. Synthesis of photodegradable polyesters from bio-based 3,4-dimethoxycinnamic acid and investigation of their degradation behaviors. Polymer 306, 127204 (2024).

Yang, X., Gitter, S. R., Roessler, A. G., Zimmerman, P. M. & Boydston, A. J. An ion-pairing approach to stereoselective metal-free ring-opening metathesis polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 13952–13958 (2021).

Lloyd, E. M. et al. Efficient manufacture, deconstruction, and upcycling of high-performance thermosets and composites. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 1, 477–485 (2023).

Johnson, A. M., Husted, K. E. L., Kilgallon, L. J. & Johnson, J. A. Orthogonally deconstructable and depolymerizable polysilylethers via entropy-driven ring-opening metathesis polymerization. Chem. Commun. 58, 8496–8499 (2022).

Fouilloux, H., Rager, M. N., Ríos, P., Conejero, S. & Thomas, C. M. Highly efficient synthesis of poly(silylether)s: access to degradable polymers from renewable resources. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202113443 (2022).

Aplin, J. T. & Bauld, N. L. Mechanistic distinctions between cation radical and carbocation propagated polymerization. J. Org. Chem. 63, 2586–2590 (1998).

Colomer, I., Batchelor-McAuley, C., Odell, B., Donohoe, T. J. & Compton, R. G. Hydrogen bonding to hexafluoroisopropanol controls the oxidative strength of hypervalent iodine reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 8855–8861 (2016).

Schmeisser, M., Illner, P., Puchta, R., Zahl, A. & van Eldik, R. Gutmann donor and acceptor numbers for ionic liquids. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 10969–10982 (2012).

Koike, T. & Akita, M. Visible-light radical reaction designed by Ru- and Ir-based photoredox catalysis. Inorg. Chem. Front. 1, 562–576 (2014).

Cai, Y., Lu, J., Jing, G., Yang, W. & Han, B. High-glass-transition-temperature hydrocarbon polymers produced through cationic cyclization of diene polymers with various microstructures. Macromolecules 50, 7498–7508 (2017).

Zhu, L., Cheng, X., Su, W., Zhao, J. & Zhou, C. Molecular insights into sequence distributions and conformation-dependent properties of high-phenyl polysiloxanes. Polymers 11, 1989 (2019).

Kean, Z. S., Niu, Z., Hewage, G. B., Rheingold, A. L. & Craig, S. L. Stress-responsive polymers containing cyclobutane core mechanophores: reactivity and mechanistic insights. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 13598–13604 (2013).

Ecochard, Y., Decostanzi, M., Negrell, C., Sonnier, R. & Caillol, S. Cardanol and eugenol based flame retardant epoxy monomers for thermostable networks. Molecules 24, 1818 (2019).

Zhou, W. et al. Synthesis of eugenol-based phosphorus-containing epoxy for enhancing the flame-retardancy and mechanical performance of DGEBA epoxy resin. React. Funct. Polym. 180, 105383 (2022).

Shieh, P. et al. Cleavable comonomers enable degradable, recyclable thermoset plastics. Nature 583, 542–547 (2020).

Zhang, X. & Paton, R. S. Stereoretention in styrene heterodimerisation promoted by one-electron oxidants. Chem. Sci. 11, 9309–9324 (2020).

Song, X. et al. Visible light-triggered and catalyst- and template-free syn-selective [2 + 2] cycloaddition of chalcones: solid-state suspension reaction in water to access syn-cyclobutane diastereomers. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10, 16399–16407 (2022).

Jiang, Y., Wang, C., Rogers, C. R., Kodaimati, M. S. & Weiss, E. A. Regio- and diastereoselective intermolecular [2+2] cycloadditions photocatalysed by quantum dots. Nat. Chem. 11, 1034–1040 (2019).

Fedorova, O. A. et al. The regioselective [2 + 2] photocycloaddition reaction of 2-(3,4-dimethoxystyryl)quinoxaline in solution. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 18, 2208–2215 (2019).

Plachinski, E. F. et al. A general synthetic strategy toward the truxillate natural products via solid-state photocycloadditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 14948–14953 (2024).

Davis, R. A. et al. Endiandrin A, a potent glucocorticoid receptor binder isolated from the Australian plant Endiandra anthropophagorum. J. Nat. Prod. 70, 1118–1121 (2007).

Xiong, Y. et al. Structure elucidation of plumerubradins A–C: correlations between 1H NMR signal patterns and structural information of [2+2]-type cyclobutane derivatives. Chin. Chem. Lett. 36, 110149 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, KAKENHI Grant Nos. 21H05215 (Digi-TOS) to M.A., 23H04916 (Green Catalysis Science) to N.S., 23K17370 to N.S., 23K23386 to N.S., and 24H00394 to M.A., and The Society of Synthetic Organic Chemistry, Japan (DIC Award in Synthetic Organic Chemistry) to N.S., Iketani Science and Technology Foundation to N.S., the Fujimori Science and Technology Foundation to N.S., and Tokuyama Science Foundation to N.S. NMR spectroscopy was performed at the Instrumental Analysis Center (Yokohama National University). The authors thank Ms. Sayaka Kado at the Center for Analytical Instrumentation, Chiba University (Chiba, Japan), for her assistance with high-resolution mass spectrometry. The computation was performed using the Research Center for Computational Science, Okazaki, Japan (Project: 24-IMS-C176 and 25-IMS-C294).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.N. and T.S. contributed equally. R.N., M.A., and N.S. wrote the manuscript. R.N., T.S., and N.S. designed and performed all data analyses, R.N., T.S., and K.O. performed synthetic experiments, R.N., T.S., and K.U. performed thermal analysis of the polymers, M.A. and N.S. supervised and directed this project, and all authors contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Sergei Kostjuk and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagaya, R., Seko, T., Okamoto, K. et al. Essential oil-derived decomposable polymers via cycloaddition polymerization of silyl ether-linked phenylpropanoids. Nat Commun 16, 10679 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65707-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65707-x