Abstract

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) threaten ecosystems worldwide due to their persistence, bioaccumulation, and toxicity. Through a global-scale meta-analysis of 119 aquatic and terrestrial food webs from 64 studies, we analyse 1009 trophic magnification factors (TMFs) for 72 PFAS and identify key variability drivers. On average, PFAS concentrations double with each trophic level increase (mean TMF = 2.00, 95% CI:1.64-2.45), though magnification varies considerably by compound. Notably, the industrial alternative F-53B exhibits the highest magnification (TMF = 3.07, 95% CI:2.41-3.92), a critical finding given its expanding use and minimal regulatory scrutiny. Methodological disparities across studies emerge as the dominant source of TMF variability. Our models explain 85% of the variation in TMFs, underscoring predictive capacity. This synthesis establishes PFAS as persistent trophic multipliers and provides a framework to prioritise high-risk compounds and harmonise biomagnification assessments. Our results call for consideration of stricter PFAS regulation to curb cascading ecological and health impacts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human activities increasingly destabilise ecological networks, eroding the integrity of food webs and their capacity to withstand environmental shifts1. This degradation accelerates biodiversity decline and amplifies vulnerabilities across ecosystems, with contamination by persistent toxic chemicals representing a pervasive and escalating threat2. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are synthetic chemicals specifically engineered for durability. PFAS are currently used across more than 200 categories of products3, and their resistance to degradation has led to global environmental infiltration, permeating ecosystems from industrial zones to remote habitats4,5. A portion of this contamination transfers from the geosphere to the biosphere6,7 and moves from prey to predator8. Once introduced into food webs, PFAS can traverse trophic levels if organisms absorb these compounds faster than they can metabolise or excrete them. Such dynamics drive trophic magnification, concentrating PFAS in apex predators, including humans, at levels exponentially exceeding environmental background concentrations9. Such type of bioaccumulation, coupled with PFAS’ known toxicity10, risks destabilising ecological hierarchies and exacerbating health crises across species, underscoring an urgent need to quantify and mitigate their cascading impacts.

Efforts to quantify PFAS’ impacts face the critical barrier of stark inconsistencies in reported trophic magnification11,12. Conflicting evidence ranges from reports of negligible accumulation or even biodilution in select food webs13,14 to extreme biomagnification in others9,15,16, with magnitudes varying over tenfold. This unresolved variability hinders predictive models and regulatory decisions as explanations remain contested. Competing hypotheses attribute discrepancies to inherent ecological complexity (e.g., food web structure, compound-specific traits) or methodological artifacts that artificially inflate variability. Resolving this ambiguity is essential to isolate true ecological risks from study design biases, a prerequisite for evidence-based policy.

To quantify PFAS biomagnification and resolve persistent ambiguities, we conduct the first global meta-analysis integrating standardised trophic magnification factors (TMFs) from 64 studies spanning 119 food webs. TMFs, calculated as the antilog of log-concentration versus trophic-level regression slopes, provide a unified metric to quantify cross-ecosystem trends. Our analysis systematically addresses four objectives: (1) estimating PFAS and compound-specific TMFs, (2) dissecting within- and between-study variability, (3) ranking drivers of variability (Table 1), and (4) discussing critical data gaps. By synthesising fragmented evidence, this meta-analysis delivers trophic magnification values for PFAS, defined here as organic compounds containing at least one perfluorinated methyl or methylene carbon atom, including perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs), their precursors with partially fluorinated chains (e.g., fluorotelomer-based compounds), and several replacement substances such as 6:2 chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulphonate (F-53B) and 4,8-Dioxa-3H-perfluorononanoic acid (ADONA; for a glossary of PFAS acronyms, see Supplementary Data 1). By providing results for PFAS both as a chemical group and as individual substances, this approach offers comprehensive insights into compound-specific and class-level biomagnification potential, thereby establishing a benchmark for harmonising future research and policy and bridging the divide between ecological theory and actionable chemical regulation.

Results

Systematic review and dataset overview

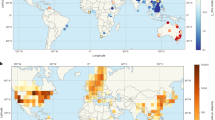

Our meta-analysis synthesised 64 studies reporting the TMF of PFAS (Table S1), yielding 1009 TMFs from 119 geographically diverse food webs and 72 PFAS. Most food webs (85%) were aquatic, with a pronounced geographic bias toward the northern hemisphere (East Asia, Europe, North America; Fig. 1). Within the aquatic food webs, 49% were freshwater, 34% were marine, and 17% were estuarine, tidal, or brackish water. Trophic levels of food webs ranged from 0.9 to 5.9, averaging 11.8 species per food web. Legacy compounds, including perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluoroundecanoic acid (PFUnDA), and perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA), were the most studied (56, 45, and 42 studies, respectively). Perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCA) and sulphonates (PFSA) comprised most TMFs (61% and 25%, respectively). Only 1% of the TMFs were from emerging PFAS.

Each point represents a food web, with colours indicating the corresponding ecosystem type. A slight jitter was applied to minimise overlap between points for clearer visualisation (for exact geographical locations, see Supplementary Data 5 or the Source Data file). Base map from rnaturalearth (1.0.0) R package. Made with Natural Earth. Free vector and raster map data @ naturalearthdata.com.

PFAS trophic magnification

Our multilevel meta-analytic model revealed an overall positive and statistically significant TMF of 2 (TMF = 2.00, 95% confidence interval (hereafter CI) = (1.64, 2.45); Fig. 2A). This indicates that, on average, the concentration of PFAS doubles with each increase in trophic level when combining all studies, food webs, and chemicals included in the analysis. Nonetheless, magnification varied considerably among compounds (Fig. 2B), indicating distinct biomagnification behaviours.

A Overall TMF based on a meta-analysis of 1009 effect sizes from 119 aquatic and terrestrial food webs. The mean meta-analytic estimate is represented by a black circle filled with red. The thicker bars indicate the 95% confidence interval, while the thinner bars represent the 95% prediction interval. Light grey circles depict individual effect sizes scaled by precision (inverse of the standard error, as shown in the legend). The number of effect sizes is represented by ‘k’, while the number in parentheses indicates the number of studies. The red dotted line highlights a TMF of 1 (biomagnification above 1 and biodilution below 1). The x-axis was capped at 10 for improved visual readability and does not show 15 effect sizes (for the full version of the plot, see Fig. S6). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. B) Compound-specific TMFs for individual PFAS estimated using a subgroup-correlated effects meta-regression model. A black bubble represents the mean TMF for individual chemicals, and the bars indicate the 95% confidence interval. Bubble size represents the number of effect sizes contributing to the estimate. Bubbles and k values in black represent estimates significantly different from 1 (i.e., p < 0.05). The number of effect sizes is represented by ‘k’, while the number in parentheses indicates the number of studies. Dark and light green shields identify compounds listed in the global treaty the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants and the European regulatory framework REACH regulation, respectively (for more information on PFAS regulation classification, see the ‘Statistical modelling overview’ paragraph in the Methods section and Supplementary Table 3). Only the results for compounds with at least ten effect sizes are shown in B (for the full version of the plot, see Fig. S1). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

We observed a high level of relative heterogeneity17 (i.e., the percentage of variance between effect sizes that cannot be attributed to sampling error) across our dataset (I2total = 97.55%), with the majority of the variation attributed to differences at the effect size, study, and chemical levels (I2PFAS = 29.84%; I2study = 27.64%; I2es = 27.18%). A smaller proportion of the heterogeneity was associated with the food web level (I2fw = 12.89%). To explain this heterogeneity and explore potential sources of variability (Table 1), we conducted single- and multi-moderator meta-regression analyses.

Sources of variability

A single-moderator meta-regression analysis revealed that the type of sample analysed (whole-organism, tissue-specific, or a combination of both) was a statistically significant predictor of TMF (F(df1 = 3, df2 = 1006) = 20.9, p < 0.001; Fig. 3A). On average, TMFs calculated using tissue-specific samples (e.g., liver, muscle, blood plasma) or whole-organism homogenates were 50% higher than those based solely on whole-organism samples (TMFcontrast = 1.50, CI = (1.21, 1.84)). However, only 10% of studies (n = 6) applied a biomass conversion to adjust tissue-specific concentrations to whole-organism equivalents.

Trophic magnification factor (TMF) of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), stratified by sample type (A), concentration determination method (B), trophic enrichment factor (C), and treatment strategy of undetected values (D). The meta-analytic mean estimate for each stratification is represented by a red-filled circle with a black outline. Thicker bars denote the 95% confidence interval, while thinner bars represent the 95% prediction interval. Light grey circles show individual effect sizes, scaled by precision (inverse of the standard error, as indicated in the legend). The number of effect sizes is represented by ‘k’, while the number in parentheses indicates the number of studies. The red dotted line marks a TMF of 1, with values above 1 indicating biomagnification and those below 1 indicating biodilution. TMF values are capped at 14 for improved visual clarity (refer to Fig. S7-S10 for full versions). In panel A, ‘mixed’ refers to a combination of specific tissue and whole-organism samples. R2 values represent the proportion of variance explained only by the fixed effects in the model (marginal R2). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

We also found significant differences between TMFs derived from non-normalised PFAS concentrations and those adjusted for protein or lipid content (F(df1 = 1, df2 = 943) = 17.5, p < 0.0001; Fig. 3B). TMFs based on non-normalised concentrations were, on average, 44% higher than those using normalised values (TMFcontrast = 1.44, CI = (1.21, 1.70), p < 0.0001). Additionally, the nitrogen isotope trophic enrichment factor (TEF) (F(df1 = 4, df2 = 735) = 12.1, p < 0.0001; Fig. 3C) and the method used to handle undetected data (F(df1 = 1, df2 = 5) = 4, p = 0.0014; Fig. 3D) were also significant predictors of TMF. We observed high variability in how undetected data were treated across studies (Table S4).

Meta-regression analysis with PFAS identity as moderator identified PFAS type as a statistically significant predictor of TMF (F(df1 = 52, df2 = 935) = 19.3, p < 0.0001). Twelve PFAS exhibited results significantly greater than 1, with F-53B, PFOS, and PFDA having the highest TMFs (F-53B: TMF = 3.07, CI = (2.41, 3.92); PFOS: TMF = 3.02, CI = (2.64, 3.46); PFDA: TMF = 2.80, CI = (2.35, 3.33); PFUnDA: TMF = 2.41, CI = (2.04, 2.86); PFNA: TMF = 2.21, CI = (1.85, 2.65); PFTrDA: TMF = 2.04, CI = (1.58, 2.64); PFDoDA: TMF = 2.01, CI = (1.75, 2.32); FOSA: TMF = 1.89, CI = (1.38, 2.59); PFHxS: TMF = 1.76, CI = (1.33, 2.32); PFTeDA: TMF = 1.42, CI = (1.15, 1.75); Fig. 2B; for a glossary of PFAS acronyms, see Supplementary Data 1). Ten additional compounds also showed TMFs significantly above 1 (Fig. S1), although these results were based on fewer than ten effect sizes. We found no statistical evidence of biodilution for any PFAS (i.e., TMF < 1; Fig. S1). Notably, all TMFs for the substance F-53B were derived from food webs located in East Asia (Supplementary Table 2), and we observed a significant effect of geographic regions (i.e., North America, Europe, East Asia, and polar regions) on the TMF (F(df1 = 5, df2 = 966) = 9.3, p < 0.0001; Fig. S2). Our meta-regression analysis identified PFAS chemical class as a moderator of TMF (F(df1 = 4, df2 = 973) = 1.4, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4A). The PFAS carbon chain length did not show a significant moderating effect on TMF values (F(df1 = 1, df2 = 984) = 0.5561, p = 0.4560; Fig. 5A). Additionally, the perfluoroalkyl chain length, defined as the number of fully fluorinated carbon atoms (–CF₂– and –CF₃ groups) in the linear alkyl chain of a PFAS molecule, excluding any non-fluorinated carbon atoms that are part of the functional group (e.g., carboxylic acid –COOH), was not correlated with TMF values (F(df1 = 1, df2 = 977) = 1.3892, p = 0.2388; Fig. S3).

Trophic magnification factor (TMF) of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), stratified by PFAS chemical class (A), food webs of exclusively water breathing organisms versus mixed breathing types (B), and food webs with either air breathing or water breathing top predators (C). The meta-analytic mean estimate for each stratification is represented by a red-filled circle with a black outline. Thicker bars denote the 95% confidence interval, while thinner bars represent the 95% prediction interval. Light grey circles show individual effect sizes, scaled by precision (inverse of the standard error, as indicated in the legend). The number of studies is indicated in parentheses, with ‘k’ representing the number of effect sizes. The red dotted line marks a trophic magnification factor (TMF) of 1, with values above 1 indicating biomagnification and those below 1 indicating biodilution. TMF values are capped at 14 for improved visual clarity (refer to Fig. S11–S13 for full versions). R2 values represent the proportion of variance explained only by the fixed effects in the model (marginal R2). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The relationship between trophic magnification of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and carbon chain length (A), trophic position of the food web’s baseline organism (B), trophic position of the food web’s top predator (C), the number of trophic levels in the food web (D), food webs’ latitude (E), and publication year of the included studies in the meta-analysis (F). The uni-moderator fitted models are depicted as thick black lines, with their 95% confidence intervals shown as red dashed lines and 95% prediction intervals represented by dotted black lines. Light grey circles represent the individual effect sizes (k), and the size of each circle reflects its precision (inverse of standard error). The number of effect sizes is represented by ‘k’, while the number in parentheses indicates the number of studies. The TMF is on the natural logarithm scale to enhance visual readability of results. R2 values represent the proportion of variance explained only by the fixed effects in the model (marginal R2). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

We did not find statistically significant differences in average TMFs across ecosystem types (terrestrial vs aquatic) (TMFcontrast = 1.05, CI = (0.65, 1.71), F(df1 = 1, df2 = 1007) = 0.0394, p = 0.8428; Fig. S4). Within aquatic ecosystems, no differences emerged between marine and freshwater ecosystems (TMFcontrast = 0.76, CI = (0.51, 1.11), F(df1 = 1, df2 = 635) = 1.9856, p = 0.1593; Fig. S5). On the other hand, we observed statistically significant differences in TMFs between food webs composed exclusively of water-breathing organisms and those that included both water- and air-breathing organisms (F(df1 = 1, df2 = 1007) = 6.2, p = 0.0128; Fig. 4B). Specifically, TMFs in food webs consisting only of water-breathing organisms were 52% lower (TMFcontrast = 0.52, CI = (0.31, 0.87)), on average, than those in mixed food webs. Similarly, food webs with a water-breathing top predator had TMFs that were 60% lower than those with an air-breathing top predator (F(df1 = 1, df2 = 856) = 6.6, p = 0.0104; TMFcontrast = 0.60, CI = (0.41, 0.88); Fig. 4C).

We found no direct association between TMF and the trophic positions of either the baseline organism (F(df1 = 1, df2 = 839) = 1.8, p = 0.1826; Fig. 5B) or the top predator (F(df1 = 1, df2 = 839) = 0.1, p = 0.7030; Fig. 5C). Similarly, the number of trophic levels in a food web was not related to TMF values (F(df1 = 1, df2 = 839) = 0.5745, p = 0.4487; Fig. 5D). Latitude showed no effect on TMFs (F(df1 = 1, df2 = 1007) = 0, p = 0.9722; Fig. 5E).

When we tested the regulation status of chemicals (i.e., whether they are listed under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants18, the REACH regulation19, or remain internationally unregulated) as a post-hoc moderator (i.e., not pre-registered; see Supplementary Table 3 for details), we found an effect on TMF (F(df1 = 3, df2 = 841) = 11, p < 0.0001; Fig. S14). However, TMFs did not differ between internationally unregulated compounds and those listed under REACH (TMFcontrast = 0.67, CI = (0.39, 1.13)) or the Stockholm Convention (TMFcontrast = 0.88, CI = (0.52, 1.49)).

The results from the multi-moderator meta-regression model (hereafter the ‘full model’), which accounts for potential confounding correlations among moderators, corroborated the findings of the univariate models, identifying sample type (i.e., whole-body, tissue-specific, or mixed) and concentration determination method (normalisation) as predictors of variability in TMF (p < 0.0001 for both). However, unlike the univariate models, the full model revealed a borderline non-significant effect of breathing type at both the food web and top predator levels (p = 0.051 and p = 0.057, respectively). PFAS chemical class, carbon chain length, and food webs’ latitude did not emerge as predictors of change from the full model. We excluded five moderators with moderate to high levels of missing data from the full model, including the strategy for handling undetected values (n = 281), trophic enrichment factor (n = 83), trophic levels of the baseline organism (n = 119) and top predator (n = 119), and food web length (n = 119), to preserve statistical power. A correlation analysis, aided by visual inspection of an alluvial plot of categorical variables, confirmed that the included moderators were not highly correlated (i.e., no evidence of excessive collinearity; Fig. S15). Notably, our model explained 85% of the variation in TMFs when accounting for both fixed and random effects (conditional R² = 0.85), indicating strong predictive capacity. The fixed effects alone explained around 18% of the variance (marginal R² = 0.18).

We used multi-model inference to generate models with all possible combinations of moderators from the full model. Two “best models” were identified based on the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Sample type, concentration determination method, breathing type of top predator and whole food web, and PFAS carbon chain length and chemical class appear in both models. Food webs’ latitude did not appear in the second-ranked model but appeared in the first-ranked. Relative importance analysis with Akaike weights identified (1) the type of sample, concentration determination method, and carbon chain length as the most important predictors of change, (2) the breathing type of top predator and whole food web and PFAS chemical class as secondary predictors, and (3) food webs’ latitude as the least important predictor (Fig. S16).

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

A visual assessment of study precision (inverse of standard error, Fig. S17) and a meta-regression of time-lag (F(df1 = 1, df2 = 1007) = 0, p = 0.9490; Fig. 5F) provided little evidence of publication bias. However, the meta-regression with standard error as a moderator indicated a potential publication bias (F(df1 = 1, df2 = 1007) = 22, p < 0.001; Fig. S18). Applying a two-step robust point and variance estimation20 reduced the effect magnitude by a factor of 3.46, but the direction and statistical significance remained unchanged (TMF = 1.65, CI = (1.28, 2.13)). The leave-one-out analysis showed that no individual study had a substantial impact on the overall results (Fig. S19). A validation test of the meta-regression model, using PFAS identity as a moderator, found no evidence of overparameterisation, supporting the model’s reliability (Supplementary Method 1 and Fig. S20). A study validity assessment was performed using a modified version of SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool21 (Supplementary Method 2 and Supplementary Data 2). Excluding studies with at least one high-risk-of-bias item did not change the overall direction of the meta-analytic result (Fig. S21). It only slightly affected its magnitude, providing evidence of no significant impact of the removal of potentially biased studies on the robustness of the findings.

Discussion

We found strong evidence for the amplification of PFAS contamination as it moves up the food chain. Notably, when aggregating results from different chemicals (n = 72) and ecosystems (n = 119), we found that, on average, PFAS concentrations doubled with each increase in trophic level. However, we observed substantial variation among individual compounds. While F-53B and PFOS showed TMFs exceeding 3, others were below 1 (see Figs. 2B and S1). Although our analysis provides a mean TMF estimate across all PFAS compounds, caution is warranted when interpreting this value. Treating PFAS as a homogeneous class may obscure critical differences in trophic transfer. As such, risk assessments and regulatory decisions should prioritise compound-specific evidence wherever possible.

Our data showed high heterogeneity, with nearly 30% of TMF variability attributed to compound-specific differences. The rest was evenly divided between within- and between-study factors. Methodological differences across studies emerged as the primary drivers of TMF variation. Although some differences reflect genuine biological variability, much of the observed variation arises from inconsistent methodological decisions. Two earlier literature reviews11,12 hypothesised that multiple factors influence PFAS TMFs. Our analysis ranks the contribution of these factors using a quantitative approach and a model that explained 84% of the total variability in the data.

Sample type was one of the most important predictors of change in TMF estimates. Specifically, TMFs measured in food webs where lower trophic level organisms were analysed as whole organisms and upper trophic level ones using a tissue-specific sample had a 50% higher TMF than those with all organisms analysed as whole organisms. This effect arises because some tissues and organs, such as the liver, muscle, and lung, accumulate the highest PFAS concentrations22,23, resulting in an overestimation of the TMF. Conversely, using tissues not prioritised by PFAS bioaccumulation (e.g., non-target organs) in top predators risks underestimating TMFs, obscuring true magnification trends. Our finding quantitatively supports concerns previously raised by Borgå et al.24 and emphasises the impact of sampling strategies on TMF outcomes. Concentration determination methods also contributed to variability, as normalising PFAS concentrations for lipid or protein content consistently resulted in lower TMFs. While Kelly et al.25 first proposed accounting for these factors, our analysis reinforces the importance of recognising lipid- and protein-normalisation as critical sources of variation in TMF calculations. Furthermore, the observed influence of nitrogen isotope enrichment factors (TEF) on TMF reflects the significance of accurately quantifying Δ15N dynamics. While the widely applied average Δ15N of 3.4‰ per trophic level offers practical utility, its oversimplification risks misrepresenting food web structure by masking taxon-specific variability and the dynamic nature of isotopic discrimination26. However, our model revealed that the specific contribution of TEF to TMF variability was relatively little when accounting for the influence of other moderators included in this meta-analysis. We also observed an effect of the strategy used to deal with undetected values (e.g., the instrument limit divided by two) on the TMF. However, the high variability of strategies and missing information hindered our ability to test its effect while controlling for other moderators.

Beyond methodological drivers, true biological variability associated with ecological and environmental differences exerts limited influence. While TMFs were significantly higher in food webs containing both water and air breathing organisms, particularly those culminating in air-breathing apex predators, this pattern is likely attributable to confounding factors inherent to the samples. Notably, when accounting for potential confounders, biological variability did not emerge as a robust predictor of observed differences. A plausible explanation for this confounding lies in the structural composition of such food webs: systems integrating both water and air breathing organisms predominantly terminate in air breathing predators, where PFAS concentrations are measured in specific tissues or organs. This measurement focus may inadvertently conflate biological processes with methodological artifacts tied to tissue-specific PFAS bioaccumulation dynamics. Furthermore, we observed no significant differences in TMFs between terrestrial and aquatic food webs, corroborating the hypothesis of the aforementioned confounding effect.

Building on these general patterns, our analysis revealed significant trophic magnification for twelve individual compounds. Among these, F-53B (including 6:2 and 8:2 Cl-PFESA), PFOS (including linear and branched isomers), and PFDA exhibited the highest magnification factors (F-53B: TMF = 3.07, CI = (2.41, 3.92); PFOS: TMF = 3.02, CI = (2.64, 3.46); PFDA: TMF = 2.80, CI = (2.35, 3.33)). Of these twelve compounds, six are currently regulated under a global treaty, the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants18, eight are listed in the European REACH regulation19, and one (F-53B) remains unregulated at the international level27. We observed significant variation in TMF across compounds, with some exhibiting particularly high magnification patterns, warranting closer examination. Notably, our findings reveal that F-53B, a trade name for a complex mixture of chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulphonic acids (primarily 6:2 and 8:2 Cl-PFESA), exhibits a higher trophic magnification factor than PFOS, the compound it was designed to replace28. This finding raises concerns about the environmental safety of F-53B and suggests it may qualify for classification as a very bioaccumulative (vB) substance under the REACH regulation. Originally synthesised in the 1970s, chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulphonic acids have been used predominantly as mist suppressants in China’s electroplating industry29. Mist suppressants reduce the formation of airborne droplets or fumes during industrial processes. Production of F-53B increased after 2000, following the phase-out of PFOS by major manufacturers from 2000 to 200230. However, some industries ceased F-53B production in 2020 due to more stringent environmental regulations31. Like PFOS, F-53B is resistant to degradation and poses a risk to aquatic ecosystems29. It has been widely detected in the blood of the Chinese population, with several health disorders linked to its exposure27,32. Although F-53B use remains largely confined to China, environmental monitoring has detected its presence in wildlife and ecosystems there14,28,33, and, to a lesser extent, in South Korea34, Greenland35, the United States, and Europe36. Our results reiterate prior concerns37 about F-53B’s extreme bio-persistence, highlighting its potential risks as one of the most enduring PFAS compounds studied to date.

We acknowledge that our meta-analysis rests on key assumptions inherent to the use of the TMF. First, the TMF assumes steady-state conditions11, where the intake and elimination of PFAS are balanced. If the included studies in our meta-analysis violate this assumption, our findings may capture short-term fluctuations rather than long-term trends in PFAS TMF, potentially affecting its accuracy. Second, the TMF assumes that dietary intake is the primary pathway of contaminant exposure and that trophic level largely determines contaminant buildup in organisms and food webs24. However, the relationship between chemical concentration and trophic level may be distorted due to variability within and between species if different exposure pathways (e.g., inhalation, dermal exposure, direct uptake from water or sediments) significantly influence contaminant levels in upper-trophic level organisms.

In addition to these foundational assumptions, our meta-analysis has minor limitations worth mentioning. Our dataset is skewed towards aquatic food webs, with terrestrial food webs being underrepresented. As a result, our findings are likely more applicable to aquatic ecosystems. Although we did not observe significant differences between the two types of food webs, we consider our results for terrestrial food webs to be preliminary. Furthermore, the geographic distribution of available studies, with a disproportionate concentration in North America, Europe, and China, limits the global applicability of our findings, particularly for understudied regions like the southern hemisphere. Finally, our results provided some evidence of publication bias, suggesting that smaller studies in our dataset tend to report larger effect sizes. However, after statistically accounting for this correlation, the direction and significance of the effect remained unchanged, demonstrating the robustness of our findings. This pattern may therefore be driven by unexplained heterogeneity rather than a small-study effect38. Despite these limitations, our meta-analysis provides the most comprehensive quantitative synthesis of PFAS TMFs to date, though its conclusions should be interpreted with these caveats in mind.

Considering our findings, we propose two recommendations for future research on TMF estimation for chemicals in general, including but not limited to PFAS. First, researchers could convert biomass to tissue-specific concentrations into whole-body concentrations (see Kidd et al.39) to improve the comparability of lower and higher trophic levels. If a biomass conversion cannot be used, multiple tissues or organs should be used for higher trophic level organisms. Small organisms like plankton and invertebrates are typically analysed whole due to their size. In contrast, contaminants in larger species (e.g., fish, birds, or mammals) are usually quantified via specific tissues due to ethical and practical reasons, ignoring uneven accumulation in the body22,40. Biomass-based conversion to whole-body concentrations or multi-tissue analysis would improve TMF accuracy by accounting for relative heterogeneity. Second, future studies should report TMFs using both protein-normalised and non-normalised concentrations. Unlike many persistent organic pollutants, PFAS preferentially bind to proteins41,42, making dual reporting helpful for cross-chemical comparisons and standardised estimates across species with diverse tissue compositions. Finally, studies should evaluate the sensitivity of their results to variations in the chosen TEF. In ecological food web models, TEF values are often selected arbitrarily and may not accurately reflect the true isotopic enrichment per trophic level26. Such discrepancies can influence the results, potentially leading to overestimating or underestimating trophic position and biomagnification patterns. Our recommendations aim to enhance methodological consistency, reduce bias, and ensure that observed TMF variability reflects true biological, chemical, or ecological differences rather than methodological artifacts. For further guidance on measuring the TMF, see Fremlin et al.43.

In summary, our analysis provides compelling evidence of PFAS trophic magnification in both aquatic and terrestrial food webs by an average factor of 2, identifies F-53B and several other chemicals as highly biomagnifying, and highlights methodological choices as key drivers of variability in TMF estimates. An average TMF of two indicates that, across all compounds and ecosystems analysed, concentrations double at each trophic level, threatening apex predators and humans and potentially destabilising biodiversity and food web resilience. This quantifiable risk may demand urgent policy action: stricter regulation of PFAS discharges, expanded monitoring of high-trophic species, and global treaties to curb bio-accumulative chemical production. Furthermore, our results reveal widespread methodological disparities that obscure true ecological drivers of PFAS biomagnification, undermining risk assessments and delaying targeted regulations. Addressing these inconsistencies must precede policy. Standardised protocols are essential to isolate real-world trends from study artifacts, ensuring regulatory decisions reflect ecological reality.

Methods

Our methodology consisted of five key procedural steps. First, we registered the project plan44, which detailed the research questions, hypotheses, and methods. Minor revisions were made to the original plan, and these changes were documented, explained, and justified (Supplementary Table 5). Second, we identified the research question components (Supplementary Method 3) and conducted a systematic literature search of primary studies relevant to the research topic. Third, we extracted specific data items from the literature and stored them in a relational database (Supplementary Data 1 and 5). Fourth, we tested our research questions by extracting or estimating effect sizes and using statistical modelling techniques. Fifth, we tested the robustness of our analysis through a publication bias assessment and sensitivity analysis. The methods are presented in accordance with the Method Reporting with Initials for Transparency (MeRIT) system45, while data and analysis reporting adhere to the PRISMA-EcoEvo guidelines46 (Supplementary Table 6). We used an adapted version of the SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for study validity assessment21 (see the ‘Publication Bias and Sensitivity Analysis’ section for more details). The raw data and code are publicly available in our GitHub repository (https://github.com/ThisIsLorenzo/PFAS_Trophic_Magnification).

Systematic review and dataset structure

LR conducted a systematic literature search across six academic databases (PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, GreenFile via EBSCO, Bielefeld Academic Search Engine, and ProQuest Theses & Dissertations) to identify studies on the trophic magnification of PFAS. The Scopus search string was validated by cross-referencing 25 previously identified records from an earlier literature review12, retrieving all entries, thereby confirming the string’s comprehensiveness (Supplementary Table 7). The initial search yielded 3744 bibliographic records. Comprehensive details regarding search dates, query syntaxes, and the number of hits per database are provided in the Supplementary Table 8.

Duplicated records were systematically identified and removed using a two-step process: first, through string-matching algorithms implemented in the R package synthesisr47 (0.3.0), which detected 1385 duplicates; then, additional deduplication using Rayyan’s proprietary function (https://www.rayyan.ai/), which identified 14 remaining duplicates. This resulted in a final corpus of 2345 unique records.

Six independent reviewers (LR, ML, CW, PPottier, KM, PPollo) screened titles and abstracts of 2,345 records against predefined eligibility criteria (Supplementary Method 4). LR and ML performed a pilot assessment on a 10% subset of records to ensure consistency in full-text screening, after which LR completed the remaining full-text evaluations (Fig. S22). Studies excluded during full-text screening were documented with rationale (Supplementary Table 9). LR extracted the data and organised it into five structured tables summarising study characteristics, study validity assessment results, food web parameters, PFAS analytes, and quantitative datasets used for effect size calculations (Fig. S23).

The trophic magnification factor

In this meta-analysis, we used the Trophic Magnification Factor (TMF) as the effect size, along with its standard error (SE), calculated as the square root of the sampling variance. The TMF is commonly used to assess the trophic magnification potential of pollutants and represents the increase in the concentration of a chemical compound per trophic level. The TMF is derived from the antilog of the slope (\(b\) in Eq. 1) of the relationship between log-transformed (to the base of 10 or Euler’s number) PFAS concentration and the trophic levels of organisms belonging to the same food web (Eq. 2).

where \({TL}\) represents the trophic level (also known as trophic position) of organisms in a food web and \(a\) is the intercept of the regression. The trophic level of an organism is commonly calculated using nitrogen isotope analysis (Eq. 3).

where \({{TL}}_{c}\) refers to the trophic level of a consumer, \(\left({\delta }^{15}{N}_{c}-{\delta }^{15}{N}_{b}\right)\) is the difference between the ratios of stable isotopes of nitrogen (i.e., 15N to 14N) in the consumer and a baseline organism, \({\Delta }^{15}N\) represents the trophic discrimination factor for \({\delta }^{15}N\) and \(\lambda\) is the trophic level of the baseline organism. The TMF is considered a reliable and comparable method for evaluating PFAS transfer within food webs12. It is currently adopted under the REACH regulation as a metric of chemicals’ environmental persistence and long-term ecological impact48.

In this meta-analysis, we directly extracted the TMF and its associated standard error from the included studies (Supplementary Data 3). When the TMF or its standard error was not reported directly, but necessary data were available, we calculated the TMF using the calculation scenarios described in Supplementary Method 5. When trophic levels were not reported, but nitrogen isotope analysis data were available (i.e., \({\delta }^{15}N\)) (Eq. 4), we employed these isotope results as a proxy for the trophic positions of organisms49,50,51,52.

where terms are as mentioned before.

Statistical modelling overview

To estimate the overall TMF for PFAS, LR employed a multilevel meta-analytic model using the rma.mv function from the metafor (4.4.0) R package53. This approach allowed for the incorporation of multiple sources of variability, as our model accounted for random effects at four levels: between studies, between food webs, between types of PFAS, and within studies. LR used the natural logarithm of the TMF as the response variable and specified a variance-covariance matrix (clubSandwich package, 0.6.0) clustered over food webs to account for dependence among effect sizes54. Prior to analysis, we converted TMFs that were reported using logarithm base 10 to natural logarithms to ensure consistency across effect sizes. The variance-covariance matrix was constructed using the squared standard error of the natural logarithm of the TMF as the variance of the effect sizes. Additionally, a constant within-study correlation coefficient of 0.5 was assumed.

To assess and compare trophic magnification factors (TMFs) across individual PFAS while controlling for covariates, we applied a subgroup-correlated effects meta-regression model55. This approach avoids assuming uniform biomagnification and heterogeneity rates across all PFAS, enabling direct statistical comparison of TMFs between compounds. By isolating compound-specific differences, we quantified their relative biomagnification risks. LR built the model on a variance-covariance matrix for each PFAS identity, incorporating the clustering effects from food webs and the individual TMF identifiers. LR specified a random effects structure that allowed for variability among food webs while treating the correlations among observations as diagonal. We validated our models’ overall quality and robustness to over-parametrisation using their AICc value and profile likelihood of individual variance components (Supplementary Method 1 and Fig. S20).

LR used uni-moderator meta-regression models to explore the moderating effect of individual predictors on PFAS TMF. The models had each predictor as a fixed effect (moderator) and the same random effect structure and variance-covariance matrix as the primary meta-analytic model. The multi-moderator meta-regression model (i.e., full model) tested the combined effect of all moderators together. We assessed the moderators for missingness and correlation before fitting them into the full model (Fig. S15). We also categorised chemicals according to their regulatory status. This classification was determined by evaluating whether the substances were included in Annexes A, B, and C of the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants18, listed in the European regulatory framework REACH regulation19, or not listed in any of these two international regulations (details provided in Supplementary Table 3). The categorisation reflects the most accurate and comprehensive information available during the analysis. We fitted the groups as moderators using the unregulated group as a reference to see if unregulated compounds had a statistically different mean than regulated ones.

Finally, to identify the most informative predictors of trophic magnification in our meta-analysis, LR employed model selection and multi-model inference using the dredge function (MuMIn package, 1.48.4)56 on the full model. The dredge function systematically generated a set of candidate models by exploring all possible combinations of predictor variables. These models were ranked based on Akaike Information Criterion corrected for small sample sizes (AICc), allowing us to assess the relative support for each candidate model. We selected the top models with a delta AICc value of ≤ 4 for further analysis and interpretation, and calculated the sum of model weights for each predictor variable to estimate their relative importance.

All analyses were performed in the R computational environment (4.4.0)57 using the tidyverse (2.0.0) framework (dplyr, tidyr, stringr, readr) for data cleaning and manipulation, and orchaRd and ggplot for visualisation. Additional packages were used for model selection, figure assembly, mapping, and table formatting (the full list of packages is provided in the analysis code). Confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated at the 95% level, and statistical significance was determined at a p value threshold of 0.05.

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

LR assessed the risk of publication bias58 by conducting the following two analyses: (1) Visual inspection of the full model’s residuals against their standard error38 and regression analysis of the effect size against its variance; (2) Regression analysis with publication year as moderator to test for time-lag bias59. The robustness of the meta-analytic results was assessed through the following three sensitivity analyses: (1) A ‘Leave-one-out’ analysis; (2) Exclusion of high-risk studies according to a study validity assessment21 (adapted SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool; Supplementary Method 2); (3) Validation of the subgroup correlated effects model (Supplementary Method 1).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw and generated data used in this study are available in the GitHub repository under accession code https://github.com/ThisIsLorenzo/PFAS_Trophic_Magnification. A permanent, citable reference to the GitHub repository hosting the data used in this study is provided with this paper60. Raw data is also provided in Supplementary Data 1–5. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The analysis code used in this study is available in the GitHub repository under accession code https://github.com/ThisIsLorenzo/PFAS_Trophic_Magnification. A permanent, citable reference to the GitHub repository hosting the code used in this study is provided with this paper60.

References

Pauly, D., Christensen, V., Dalsgaard, J., Froese, R. & Torres, F. Fishing down marine food webs. Science 279, 860–863 (1998).

Sonne, C. et al. PFAS pollution threatens ecosystems worldwide. Science 379, 887–888 (2023).

Glüge, J. et al. An overview of the uses of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 22, 2345–2373 (2020).

Kurwadkar, S. et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in water and wastewater: a critical review of their global occurrence and distribution. Sci. Total Environ. 809, 151003 (2022).

Miner, K. R. et al. Deposition of PFAS ‘forever chemicals’ on Mt. Everest Sci. Total Environ. 759, 144421 (2021).

Lechner, M. & Knapp, H. Carryover of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) from Soil to Plant and Distribution to the Different Plant Compartments Studied in Cultures of Carrots (Daucus carota ssp. Sativus), Potatoes (Solanum tuberosum), and Cucumbers (Cucumis Sativus). J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 11011–11018 (2011).

Zhao, S. et al. Mutual impacts of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and earthworms (Eisenia fetida) on the bioavailability of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in soil. Environ. Pollut. 184, 495–501 (2014).

Haukås, M., Berger, U., Hop, H., Gulliksen, B. & Gabrielsen, G. W. Bioaccumulation of per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) in selected species from the Barents Sea food web. Environ. Pollut. 148, 360–371 (2007).

Fremlin, K. M., Elliott, J. E., Letcher, R. J., Harner, T. & Gobas, F. A. P. C. Developing methods for assessing trophic magnification of perfluoroalkyl substances within an urban terrestrial avian food web. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 12806–12818 (2023).

Fenton, S. E. et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance toxicity and human health review: current state of knowledge and strategies for informing future research. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 40, 606–630 (2021).

Franklin, J. How reliable are field-derived biomagnification factors and trophic magnification factors as indicators of bioaccumulation potential? Conclusions from a case study on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 12, 6–20 (2015).

Miranda, D., de, Peaslee, A., Zachritz, G. F. & Lamberti, A. M. G. A. A worldwide evaluation of trophic magnification of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in aquatic ecosystems. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 18, 1500–1512 (2022).

Diao, J. et al. Perfluoroalkyl substances in marine food webs from South China Sea: trophic transfer and human exposure implications. J. Hazard. Mater. 431, 128602 (2022).

Pan, C.-G., Xiao, S.-K., Yu, K.-F., Wu, Q. & Wang, Y.-H. Legacy and alternative per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in a subtropical marine food web from the Beibu Gulf, South China: fate, trophic transfer and health risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 403, 123618 (2021).

Simmonet-Laprade, C. et al. Investigation of the spatial variability of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substance trophic magnification in selected riverine ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 686, 393–401 (2019).

Tomy, G. T. et al. Trophodynamics of some PFCs and BFRs in a Western Canadian Arctic Marine Food Web. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 4076–4081 (2009).

Higgins, J. P. T. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–560 (2003).

Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs). https://chm.pops.int/.

European Commission. REACH Regulation (EC 1907/2006). https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/chemicals/reach-regulation_en (2007).

Yang, Y. et al. Robust point and variance estimation for meta-analyses with selective reporting and dependent effect sizes. Methods Ecol. Evol. 15, 1593–1610 (2024).

Hooijmans, C. R. et al. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 14, 43 (2014).

Robuck, A. et al. Tissue-specific distribution of legacy and novel per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in juvenile seabirds. Environ. Sci. Techno. Lett. 8, 457–462 (2021).

Pérez, F. et al. Accumulation of perfluoroalkyl substances in human tissues. Environ. Int. 59, 354–362 (2013).

Borgå, K. et al. Trophic magnification factors: considerations of ecology, ecosystems, and study design. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 8, 64–84 (2012).

Kelly, B. C. et al. Perfluoroalkyl contaminants in an arctic marine food web: trophic magnification and wildlife exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 4037–4043 (2009).

Letourneur, Y., Fey, P., Dierking, J., Galzin, R. & Parravicini, V. Challenging trophic position assessments in complex ecosystems: calculation method, choice of baseline, trophic enrichment factors, season and feeding guild do matter: a case study from Marquesas Islands coral reefs. Ecol. Evol. 14, e11620 (2024).

He, Y. et al. Human exposure to F-53B in China and the evaluation of its potential toxicity: an overview. Environ. Int. 161, 107108 (2022).

Liu, W. et al. Atmospheric chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate and ionic perfluoroalkyl acids in 2006 to 2014 in Dalian, China. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 36, 2581–2586 (2017).

Wang, S. et al. First report of a Chinese PFOS alternative overlooked for 30 years: its toxicity, persistence, and presence in the environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 10163–10170 (2013).

Briels, N., Ciesielski, T., Herzke, D. & Jaspers, V. Developmental Toxicity of Perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and its chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonate alternative F-53B in the domestic chicken. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 12859–12867 (2018).

Environment Agency. Environmental risk evaluation report. Potassium 9-chlorohexadecafluoro-3-oxanonane-1-sulfonate [F-53B] (CAS no. 73606-19-6). 8 (2023).

Hong, S.-H. et al. Orally administered 6:2 chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate (F-53B) causes thyroid dysfunction in rats. Toxics 8, 54 (2020).

Feng, X. et al. Potential sources and sediment-pore water partitioning behaviors of emerging per/polyfluoroalkyl substances in the South Yellow Sea. J. Hazard. Mater. 389, 122124 (2020).

Wang, W. et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and their alternatives in black-tailed gull (Larus crassirostris) eggs from South Korea islands during 2012–2018. J. Hazard. Mater. 411, 125036 (2021).

Gebbink, W. A. et al. Observation of emerging per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in Greenland marine mammals. Chemosphere 144, 2384–2391 (2016).

Pan, Y. et al. Worldwide distribution of novel perfluoroether carboxylic and sulfonic acids in surface water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 7621–7629 (2018).

Shi, Y. et al. Human exposure and elimination kinetics of chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonic acids (Cl-PFESAs). Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 2396–2404 (2016).

Nakagawa, S. et al. Methods for testing publication bias in ecological and evolutionary meta-analyses. Methods Ecol. Evol. 13, 4–21 (2022).

Kidd, K. A. et al. Practical advice for selecting or determining trophic magnification factors for application under the European Union Water Framework Directive. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 15, 266–277 (2019).

Ricolfi, L., Taylor, M. D., Yang, Y., Lagisz, M. & Nakagawa, S. Maternal transfer of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in wild birds: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chemosphere 361, 142346 (2024).

Han, X., Hinderliter, P. M., Snow, T. A. & Jepson, G. W. Binding of perfluorooctanoic acid to rat liver-form and kidney-form α2u-globulins. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 27, 341–360 (2004).

Zhao, L. et al. Insight into the binding model of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances to proteins and membranes. Environ. Int. 175, 107951 (2023).

Fremlin, K. M., Elliott, J. E. & Gobas, F. A. P. C. Guidance for measuring and evaluating biomagnification factors and trophic magnification factors of difficult substances: application to decabromodiphenylethane. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. vjae025 https://doi.org/10.1093/inteam/vjae025 (2025)

Ricolfi, L. et al. What Is the Overall PFAS Trophic Magnification Estimate and the Key Drivers of Variability?: A Other Aggregative Reviews (e.g. Meta-Analyses, Critical Reviews) Protocol. https://www.proceedevidence.info/protocol/view-result?id=212, https://doi.org/10.57808/PROCEED.2024.8 (2024)

Nakagawa, S. et al. Method Reporting with Initials for Transparency (MeRIT) promotes more granularity and accountability for author contributions. Nat. Commun. 14, 1788 (2023).

O’Dea, R. E. et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses in ecology and evolutionary biology: a PRISMA extension. Biol. Rev. 96, 1695–1722 (2021).

Westgate, M. & Grames, E. Synthesisr: Import, Assemble, and Deduplicate Bibliographic Datasets. (2022).

European Chemicals Agency. Guidance on Information Requirements and Chemical Safety Assessment Chapter R.11: PBT/vPvB Assessment. ECHA-23-H-10-EN 116 https://doi.org/10.2823/312974 (2023)

Cherel, Y. & Hobson, K. Geographical variation in carbon stable isotope signatures of marine predators: a tool to investigate their foraging areas in the Southern Ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 329, 281–287 (2007).

Newsome, S. D., Martinez del Rio, C., Bearhop, S. & Phillips, D. L. A niche for isotopic ecology. Front. Ecol. Environ. 5, 429–436 (2007).

Cherel, Y. et al. Accumulate or eliminate? Seasonal mercury dynamics in albatrosses, the most contaminated family of birds. Environ. Pollut. 241, 124–135 (2018).

Peterson, B. J. & Fry, B. Stable isotopes in ecosystem studies. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 293–320 https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.18.110187.001453 (1987)

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. (2010).

Nakagawa, S., Yang, Y., Macartney, E. L., Spake, R. & Lagisz, M. Quantitative evidence synthesis: a practical guide on meta-analysis, meta-regression, and publication bias tests for environmental sciences. Environ. Evid. 12, 8 (2023).

Pustejovsky, J. E. & Tipton, E. Meta-analysis with robust variance estimation: Expanding the range of working models. Prev. Sci. 23, 425–438 (2022).

Bartoń, K. MuMIn: multi-model inference.

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021).

Dickersin, K. The existence of publication bias and risk factors for its occurrence. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1990.03440100097014 (1990).

Costello, L. & Fox, J. W. Decline effects are rare in ecology. Ecology 103, e3680 (2022).

Ricolfi, L. Code and data for ‘Unravelling the magnitude and drivers of PFAS trophic magnification’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.17293157 (2025).

Stephens, R. B. B., Shipley, O. N. N. & Moll, R. J. J. Meta-analysis and critical review of trophic discrimination factors (Δ13C and Δ15N): Importance of tissue, trophic level and diet source. Funct. Ecol. 37, 2535–2548 (2023).

Conder, J. M., Gobas, F. A. P. C., Borgå, K., Muir, D. C. G. & Powell, D. E. Use of trophic magnification factors and related measures to characterize bioaccumulation potential of chemicals. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 8, 85–97 (2012).

Houde, M., De Silva, A. O., Muir, D. C. G. & Letcher, R. J. Monitoring of perfluorinated compounds in aquatic biota: an updated review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 7962–7973 (2011).

Paine, R. T. Food web complexity and species diversity. Am. Nat. 100, 65–75 (1966).

Conder, J. M., Hoke, R. A., De Wolf, W., Russell, M. H. & Buck, R. C. Are PFCAs bioaccumulative? A critical review and comparison with regulatory criteria and persistent lipophilic compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 995–1003 (2008).

Jones, P. D., Hu, W., De Coen, W., Newsted, J. L. & Giesy, J. P. Binding of perfluorinated fatty acids to serum proteins. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 22, 2639–2649 (2003).

Martin, J. W., Mabury, S. A., Solomon, K. R. & Muir, D. C. G. Bioconcentration and tissue distribution of perfluorinated acids in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 22, 196–204 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This project was financially supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Targeted Research Grant (APP1185002; awarded to GN, SN, DH), an Australian Government Research Training Programme (RTP) Scholarship (awarded to LR), and a Canada Excellence Research Chair (ERC-2022-00074; awarded to SN). Our funders and institutions played no role in the development of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: L.R., S.N., and M.L. Methodology: L.R., Y.Y., S.N., and M.L. Literature search: L.R., P.Pottier, K.M., C.W., and P.Pollo. Software: L.R. Formal analysis: L.R. and Y.Y. Data curation: L.R. Writing–Original Draft: L.R. Writing–Review and Editing: L.R. and Y.Y. PPottier, K.M., C.W., P.Pollo, D.H., G.N., M.T., S.N., and M.L. Visualisation: L.R. PPottier. Supervision: M.T., S.N., and M.L. Project administration: L.R. Funding acquisition: L.R., D.H., G.N., and S.N.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Allyson O’Brien and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ricolfi, L., Yang, Y., Pottier, P. et al. Unravelling the magnitude and drivers of PFAS trophic magnification: a meta-analysis. Nat Commun 16, 10720 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65746-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65746-4