Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 variants resistant to current antivirals remain a significant threat, particularly in high-risk patients. Although nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir both target the viral 3CL protease (Mpro), their distinct susceptibility profiles may allow alternative therapeutic approaches. Here, we identify a deletion mutation at glycine 23 (Δ23G) in Mpro that conferred high-level resistance to ensitrelvir ( ~ 35-fold) while paradoxically increasing susceptibility to nirmatrelvir ( ~ 8-fold). This opposite susceptibility pattern is confirmed both in vitro and in a male hamster infection model. Recombinant viruses carrying Mpro-Δ23G exhibit impaired replication, pathogenicity, and transmissibility compared to wild-type, though the co-occurring mutation T45I partially restore viral fitness. Structural analyses reveal critical conformational changes in the catalytic loop (Ile136–Val148) and β-hairpin loop (Cys22–Thr26), directly influencing inhibitor binding selectivity. These results highlight differential resistance profiles of Mpro inhibitors, supporting potential sequential or alternative use of nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir in patients requiring prolonged antiviral treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has been significantly mitigated by rapid advancements in vaccines and antiviral therapies, markedly reducing COVID-19-related hospitalizations and mortality1,2,3,4. However, the continuous evolution of Omicron subvariants, driven by antigenic drift, presents ongoing challenges by diminishing vaccine efficacy and potentially altering susceptibility to antiviral agents5,6,7,8. Currently, four antivirals including ensitrelvir (S-217622), nirmatrelvir (PF-07321332), remdesivir (GS-441524), and molnupiravir (EIDD-1931) are approved for treating SARS-CoV-2 infections9. Ensitrelvir and nirmatrelvir target the viral 3C-like (3CL) protease (Mpro), a conserved enzyme essential for polyprotein cleavage and viral replication10,11, whereas remdesivir and molnupiravir inhibit the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), thereby disrupting viral genome replication12,13. With increased clinical use of these antivirals, resistance mutations, particularly within Mpro have emerged8,14,15,16,17, raising concerns regarding their long-term effectiveness.

Although extensive research has characterized nirmatrelvir resistance mechanisms18, fewer studies have focused on ensitrelvir, despite its demonstrated potent activity against multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern, including Omicron subvariants, in vitro and in vivo studies9,10,19,20,21. Ensitrelvir is a non-covalent, non-peptidic inhibitor with favorable pharmacokinetics enabling once-daily dosing and a strong safety profile10,22,23. Given its expanding clinical use24, systematic characterization of ensitrelvir-associated resistance mutations is critical to mitigate potential treatment failures.

Multiple resistance-associated mutations have been identified in Mpro under antiviral selection pressure, with certain mutations (e.g., S144A, E166A/V, L167F, Δ168P, and T45I/Δ168P) conferring cross-resistance to both nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir25,26. In contrast, other mutations (e.g., T45I, D48G, M49I, and P52S) uniquely reduce susceptibility to ensitrelvir in vitro17,25. However, only a limited subset of these mutations (M49L, E166A, and M49L/E166A) have been characterized in vivo27, highlighting an urgent need to further investigate their clinical implications.

Given the expanding clinical use of ensitrelvir, understanding mutations that compromise its antiviral efficacy is crucial. Here, we characterized a deletion mutation (Δ23G) in SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, conferring significant resistance to ensitrelvir but paradoxically enhancing susceptibility to nirmatrelvir. We generated recombinant viruses harboring Δ23G, evaluated their viral fitness, pathogenicity, competitive fitness, and genetic stability under selective pressure, and performed structural analyses to elucidate resistance mechanisms. Our findings highlight distinct resistance profiles of 3CL protease inhibitors, underscoring the need for vigilant monitoring and strategic antiviral treatment to mitigate resistant SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Results

Selection and antiviral susceptibility of ensitrelvir-selected SARS-CoV-2 variants through serial passaging

To assess whether ensitrelvir induces resistance mutations, Wuhan-like SARS-CoV-2 and the BA.5 Omicron variant were serially passaged five times in Vero E6 cells under increasing concentrations of ensitrelvir, starting at 1 μM and doubling upon detectable viral replication (Fig. 1a). Viral titers were determined by TCID50 assays, and resistance mutations were identified by next-generation sequencing (NGS). In the Wuhan-like strain, NGS identified Mpro mutations Δ23G/T45I (Lineage A) and M49L (Lineage B), while BA.5 Omicron variants developed S144A (Lineage C) and P252L (Lineage D) mutations (Fig. 1b).

a Serial passage of Wuhan-like (Wild-type) and Omicron BA.5 variants of SARS-CoV-2 under escalating concentrations of ensitrelvir in Vero E6 cells. Viral replication was quantified using TCID50 (dotted line, left Y-axis) and ensitrelvir concentration indicated on the right Y-axis (continuous line). Drug concentration was increased only when viral replication was detectable. BA.5 lineage D (P252L) replicated poorly at 4 μM and yielded no recoverable virus at 8 μM; consequently, this lineage did not progress beyond passage 4 (i.e., no recovery at P5). b Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) identified through next-generation sequencing (NGS). Positions of amino acid substitutions are listed at the top; variants selected during passages (P1–P5) are indicated on the left. Darker shades of blue reflect increased mutation frequencies, with previously reported resistance mutations in the Main protease (Mpro) denoted by an asterisk (*). c, d Antiviral susceptibility assays measuring cell viability (%) in response to ensitrelvir, nirmatrelvir, and remdesivir for Wuhan-like (Wild-type, Lineages A and B, c) and BA.5 Omicron-derived variants (Lineages C and D, d). Curves represent dose-response relationships to antiviral treatments (n = 3 biological replicates). Bars indicate means ± SD. e Mean IC50 values ± SD (μM) and fold-change relative to the matched WT (Wuhan-like or BA.5). The heatmap encodes increased susceptibility ( ≤ 0.33-fold; light blue) and resistance ( ≥ 3– < 6-fold, light red; ≥ 6– < 30-fold, red; ≥ 30-fold, dark red). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Antiviral susceptibility testing showed minimal change with remdesivir across variants; only BA.5 Lineage D (P252L) exhibited a low-level reduction in susceptibility (3.41-fold) (Fig. 1c–e), consistent with its unrelated mechanism. However, in the Wuhan-like background, Lineage A (Δ23G/T45I) and Lineage B (M49L) showed high-level resistance to ensitrelvir (IC50 = 16.67 ± 2.29 μM; 32.06-fold and 31.24 ± 1.06 μM; 60.08-fold, respectively, vs WT 0.52 ± 0.03 μM) (Fig. 1c, e). Interestingly, nirmatrelvir susceptibility in Lineage A (Δ23G/T45I) markedly improved, with the IC50 decreasing to 1.40 ± 0.10 μM (0.18-fold vs WT), while Lineage B (M49L) showed no meaningful shift (7.92 ± 0.62 μM; 1.36-fold vs WT). In the BA.5 background, ensitrelvir resistance increased to an intermediate level in Lineage C (S144A; 25.38 ± 8.74 μM, 28.84-fold) and showed no meaningful shift in Lineage D (P252L) (Fig. 1d, e). For nirmatrelvir, BA.5 Lineage C showed intermediate resistance (36.95 ± 0.90 μM; 7.60-fold) and Lineage D low-level resistance (18.61 ± 0.48 μM; 3.83-fold) relative to BA.5 WT (4.86 ± 0.73 μM) (Fig. 1d, e). Overall, these results indicate that serial exposure to ensitrelvir can select for resistance mutations in both Wuhan-like and BA.5 Omicron variants. Notably, the Mpro-Δ23G/T45I mutation can confer high-level resistance to ensitrelvir while unexpectedly enhancing susceptibility to nirmatrelvir, suggesting potential differences in resistance mechanisms between these two 3CL protease inhibitors.

Susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and its recombinant variants to antivirals

Given that Mpro mutations M49L, S144A, and P252L have previously been identified as ensitrelvir resistance mutations27,28, we investigated the newly discovered Mpro-Δ23G and Mpro-T45I mutations for their impact on antiviral susceptibility. Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 viruses (Wuhan-like background) carrying single (Δ23G or T45I) or combined (Δ23G/T45I) Mpro mutations were generated using reverse genetics (RG) and evaluated in vitro against ensitrelvir, nirmatrelvir, remdesivir, and molnupiravir.

The recombinant wild-type (Mpro-WT) virus showed an ensitrelvir IC50 of 0.44 ± 0.06 μM, consistent with its parental strain (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2a, e). Notably, both single Δ23G and double Δ23G/T45I mutants exhibited high-level ensitrelvir resistance, with IC50 values of 15.20 ± 2.06 μM (34.55-fold) and 15.55 ± 1.73 μM (35.34-fold), respectively, indicating Δ23G alone confers significant resistance (Fig. 2a, e). The T45I mutation alone showed low-level resistance (IC50 = 1.75 ± 0.07 μM; 3.98-fold) without additive effects when combined with Δ23G. Regarding nirmatrelvir susceptibility, Mpro-WT displayed an IC50 of 6.02 ± 0.51 μM, similar to the parental virus (Fig. 2b, e). Remarkably, the Δ23G and Δ23G/T45I mutants showed paradoxically enhanced susceptibility ( ≥ 3-fold lower than WT) with IC50 values of 0.78 ± 0.21 μM (0.13-fold) and 1.49 ± 0.42 μM (0.25-fold), respectively (Fig. 2b, e). In contrast, T45I alone showed no meaningful shift in nirmatrelvir susceptibility (IC50 = 8.79 ± 1.06 μM; 1.48-fold increase). Susceptibility to remdesivir and molnupiravir was essentially unchanged across all recombinant viruses, confirming that these mutations specifically affect responses to 3CL protease inhibitors (Fig. 2c–e).

a–d Dose–response curves for ensitrelvir (a), nirmatrelvir (b), remdesivir (c), and molnupiravir (d) measured as cell viability (%) using recombinant viruses encoding WT, T45I, Δ23G, or Δ23G/T45I (n = 3 biological replicates; points/bars, mean ± SD). e Summary table of IC50 (mean ± SD) for each virus–drug pair (ensitrelvir/S-217622; nirmatrelvir/PF-07321332; remdesivir/GS-441524; molnupiravir/EIDD-1931). The heat map encodes increased susceptibility ( ≤ 0.33-fold; light blue) and resistance ( ≥ 3– < 6-fold, light red; ≥ 6– < 30-fold, red; ≥ 30-fold, dark red) relative to WT. f Steady-state enzyme kinetics (Michaelis–Menten; n = 3 biological replicates) for purified WT and mutant Mpro proteins, reporting kcat/Km (bars, mean ± SD). g, h Enzymatic inhibition assays (n = 3 biological replicates) for purified WT and mutant Mpro, showing residual activity (%) across inhibitor concentrations for ensitrelvir (g) and nirmatrelvir (h); IC50 trends mirror recombinant-virus phenotypes. i–k Growth kinetics in Vero E6 cells (n = 3 biological replicates) without drug (i), with 10 μM ensitrelvir (j), or with 20 μM nirmatrelvir (k). Viral titers (TCID50) are quantified over time; bars/curves show mean ± SD. Representative P values (WT vs mutants) for panel (i): WT vs T45I, p = 0.0751; WT vs Δ23G, p < 0.0001; WT vs Δ23G/T45I, p = 0.0006; Δ23G vs Δ23G/T45I, p = 0.0013. For panel (j): WT vs T45I, p > 0.9999; WT vs Δ23G, p = 0.0115; WT vs Δ23G/T45I, p < 0.0001; Δ23G vs Δ23G/T45I, p < 0.0001. For panel (k): WT vs T45I, p = 0.1525; WT vs Δ23G, p = 0.0029; WT vs Δ23G/T45I, p = 0.0029. Statistics. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons (i–k); AUC (0–72 hpi) significance is annotated by asterisks for WT vs mutants and by ‘#’ for Δ23G vs Δ23G/T45I (* p < 0.05; **, ## p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001; ns, not significant). Across panels, exact P values, n, and tests are stated in the legends; data are from three independent biological replicates unless indicated. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Enzymatic inhibition assays with purified WT and mutant Mpro proteins further validated these findings. All four Mpro proteins cleaved the fluorogenic substrate, but catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) decreased from 2.17 × 104 M-¹·s-¹ in WT to 1.91 × 104 in T45I ( ~ 88% of WT), 3.22 × 103 in Δ23G ( ~ 7-fold lower), with partial recovery to 4.17 × 103 in Δ23G/T45I (Fig. 2f). Mpro-WT showed nanomolar-level inhibition by ensitrelvir (IC50 = 0.096 ± 0.006 μM) and nirmatrelvir (IC50 = 0.166 ± 0.009 μM) (Fig. 2g, h). Ensitrelvir exhibited moderately decreased potency against T45I (IC50 = 0.184 ± 0.010 μM) and significantly diminished activity against Δ23G-containing mutants (Fig. 2g), consistent with recombinant virus phenotypes. Nirmatrelvir maintained robust inhibition across Mpro-mutants, enhanced for Δ23G (IC50 = 0.084 ± 0.005 μM) and Δ23G/T45I mutants (IC50 = 0.102 ± 0.008 μM), aligning with viral assay results (Fig. 2b, h). Consistent with these trends, ITC showed 9–10-fold tighter nirmatrelvir binding to Δ23G and Δ23G/T45I (KD, 0.44–0.45 nM) than to WT (4.20 nM), accompanied by a more favorable Gibbs free energy (ΔG, –12.42/–12.16 vs –11.80 kcal/mol) (Supplementary Fig. 1a–d). Ensitrelvir binding was detected for WT and T45I but not for Δ23G-containing mutants (Supplementary Fig. 1e–h). Together, these data demonstrate the Mpro-Δ23G mutation’s distinct resistance profile, highlighting a functional trade-off with significantly increased ensitrelvir resistance but enhanced susceptibility to nirmatrelvir.

Growth kinetics of recombinant SARS-CoV-2 variants under antiviral pressure

To evaluate the impact of Mpro-Δ23G, Mpro-T45I, and Mpro-Δ23G/T45I mutations on viral replication and antiviral susceptibility, recombinant SARS-CoV-2 variants were assessed in Vero E6 cells in the presence or absence of ensitrelvir and nirmatrelvir. In the absence of inhibitors, the Mpro-T45I variant replicated comparably to Mpro-WT, reaching peak titers by 48 hours post-infection (hpi) (Fig. 2i). In contrast, Mpro-Δ23G (24 to 60 hpi, p < 0.0001) and Mpro-Δ23G/T45I (36 to 60 hpi, p = 0.0006) variants exhibited markedly reduced replication, indicating a significant fitness cost conferred by the Δ23G deletion. Notably, the addition of T45I partially restored replication capacity in the double mutant (24 to 48 hpi, p = 0.0013), suggesting a compensatory effect.

Upon treatment with ensitrelvir (10 μM), replication of Mpro-WT and Mpro-T45I was completely inhibited, confirming their susceptibility (Fig. 2j). In contrast, the Δ23G-containing variants maintained efficient replication, consistent with their resistance phenotype. Under nirmatrelvir treatment (20 μM), Mpro-WT and Mpro-T45I showed delayed replication kinetics, eventually reaching peak titers similar to that in inhibitor-free condition by 120 hpi, indicating partial inhibition (Fig. 2k). Interestingly, Mpro-Δ23G and Mpro-Δ23G/T45I variants failed to replicate under nirmatrelvir treatment, demonstrating paradoxically increased susceptibility. These results reveal a distinct fitness trade-off associated with the Δ23G deletion: strong resistance to ensitrelvir but heightened sensitivity to nirmatrelvir. While T45I alone had minimal impact on replication or drug susceptibility, it partially compensated for the fitness deficit caused by Δ23G.

Overall structure of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro-Δ23G mutant

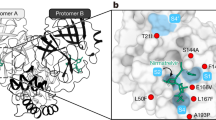

To investigate structural alterations associated with active-site mutations affecting inhibitor binding, we determined the crystal structure of the ligand-free SARS-CoV-2 Mpro-Δ23G mutant at 1.75 Å resolution in the C2 space group (Fig. 3a–e and Supplementary Table 1). Structural analysis revealed one monomer (Mpro-Δ23G protomer) per asymmetric unit, consistent with analytical size-exclusion chromatography (hydrodynamic behavior; Supplementary Fig. 2a) and SEC–MALS (oligomeric assignment; Supplementary Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 1), whereas WT, T45I, and Δ23G/T45I were dimeric in solution by SEC–MALS (Supplementary Fig. 2b). The Mpro-Δ23G protomer comprises three domains (DI, DII, and DIII), with the catalytic site located between the β-barrel structures of DI and DII, consisting of the catalytic residues His41, Cys145, and Gln16629 (Fig. 3a, b). Structural superposition with Mpro-WT indicated high overall similarity (root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) = 0.36 Å for 278 Cα atoms)30 (Fig. 3c). However, significant conformational differences were observed within critical functional regions. Specifically, Phe140 in the catalytic loop (residues 136–148) underwent a notable outward shift ( ~ 9.8 Å), disrupting its π-stacking interaction with His163 (Fig. 3b, c). This perturbation destabilizes the catalytic loop and displaces the active-site loop, potentially collapsing the oxyanion hole and rendering the enzyme inactive, consistent with previous studies31,32. Additionally, pronounced conformational changes were observed in the substrate-binding region, particularly within the intrinsically flexible catalytic loop (Ile136–Val148) of DII33 and the β-hairpin loop (Cys22–Thr25) connecting strands β1 and β2 in DI. Both regions exhibited outward displacement relative to the substrate-binding site, with the β-hairpin adopting a closed conformation. This repositioning altered the substrate-binding pocket, resulting in an extended S1’ subsite with modified shape and accessibility (Fig. 3d, e). Collectively, these structural variations in Mpro-Δ23G may influence substrate recognition, enzymatic activity, and inhibitor selectivity, providing critical insights into the molecular basis of altered inhibitor susceptibility.

a Ribbon representation of the overall structure of Mpro-∆23G, illustrating domain architecture (DI, DII, DIII) and highlighting the catalytic active site, with key catalytic residues labeled. b Detailed view of the catalytic active site interactions. Important residues including His41, Cys145, His163, Glu166, Asp187, Asn142, and Phe140 are displayed. Distance between His163 and Phe140 is indicated (9.8 Å). c Structural overlay comparing Mpro-∆23G (cyan, current study) and wild-type Mpro (yellow, PDB: 8BFQ), focusing on the catalytic loop (Ile136–Val148) and β-hairpin region (Cys22–Thr26). Structural deviations are highlighted, with inter-residue distances annotated (3.9–5.0 Å). Surface representation of the substrate-binding sites for Mpro-∆23G (d, cyan) and wild-type Mpro (e, yellow). Subsites S1, extended S1’, S2, S3, S4, and S5 are labeled, illustrating an expanded S1’ pocket in Mpro-∆23G compared to WT. Comparative structural analysis of inhibitor-bound complexes of Mpro-∆23G and variants with nirmatrelvir. Overlaid structures are shown for Mpro-∆23G and Mpro-∆23G bound with nirmatrelvir (f, pale cyan), Mpro-∆23G/45I variant in space group C2 (g, green), and Mpro-∆23G/T45I variant in space group P21 (h, pale green). Inhibitor-binding pockets and conformational shifts are highlighted by red arrows. Residue labels are according to respective variant structures.

Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro mutants (Δ23G and Δ23G/T45I) complexed with nirmatrelvir and comparison with other Mpro inhibitors

To investigate the structural basis of the Δ23G and Δ23G/T45I mutations on inhibitor binding, crystal structures of these Mpro mutants complexed with nirmatrelvir were determined. Although efforts were made to obtain complexes with ensitrelvir, only nirmatrelvir-bound structures were successfully resolved. Mpro-Δ23G was crystallized in the C2 space group (monomer per asymmetric unit), and Mpro-Δ23G/T45I was crystallized in both C2 (monomer) and P21 (dimer) space groups which represents the natural form of Mpro 29,34,35 (Supplementary Table 1). Consistently, SEC–MALS further confirmed that Δ23G/T45I is dimeric in solution (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Structural comparisons showed high similarity across complexes, with r.m.s.d. values of 0.54 Å (Δ23G, C2 vs. nirmatrelvir-bound Δ23G, C2), 0.51 Å (Δ23G, C2 vs. Δ23G/T45I nirmatrelvir-bound, C2), and 0.47 Å (Δ23G, C2 vs. Δ23G/T45I nirmatrelvir-bound, P21) (Fig. 3f–h). Upon binding to nirmatrelvir, structural rearrangements occurred predominantly within the catalytic loop (Ile136–Val148) and β-hairpin (Cys22–Thr25). The β-hairpin adopted a closed conformation, enlarging the S1 subsite, potentially altering inhibitor binding. Notably, nirmatrelvir binding restored the π-stacking interaction between Phe140 and His163, crucial for active-site integrity (Fig. 3f–h). Electron density and composite omit maps confirmed a covalent bond between nirmatrelvir’s nitrile carbon (P1 group) and Cys145 (1.76 Å) (Supplementary Figs. 3, 4). The lactam ring (P1) occupied the S1 subsite, stabilized by hydrogen bonds with His163 and Glu166. The cyclopropyl moiety (P2) engaged in extensive hydrophobic interactions within the S2 subsite (His41, Met49, Tyr54, Met165, Asp189, Asp187, Arg188). The hydrophobic tert-butyl group (P3) remained solvent-exposed, while the trifluoroacetyl group (P4) interacted via hydrogen bonds with Gln192 and Glu166 in the S4 sub-pocket, with an additional hydrogen bond formed between the P4 amide nitrogen and the carbonyl oxygen of Glu166.

In silico docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were then performed for ensitrelvir and nirmatrelvir against Mpro-WT and Mpro-Δ23G mutant. Docking indicated favorable binding to WT for both ligands, with stronger affinity for nirmatrelvir (CDOCKER energy: −55.77 kcal/mol) than for ensitrelvir ( − 13.76 kcal/mol), whereas Δ23G abolished favorable docking of ensitrelvir ( + 0.48 kcal/mol) but retained substantial nirmatrelvir binding ( − 24.05 kcal/mol) (Supplementary Fig. 5). The Δ23G substitution altered contact patterns (e.g., Met49/Pro168 for ensitrelvir; Thr190/Gln192 for nirmatrelvir), suggesting a shift in binding mode. MD trajectories revealed increased RMSD/RMSF in Δ23G relative to WT; nevertheless, both ligands remained bound, with nirmatrelvir–Δ23G complexes showing lower fluctuations than ensitrelvir–Δ23G, consistent with more stable interactions (Supplementary Fig. 5). These data indicate that Δ23G disrupts ensitrelvir binding and local stability, whereas nirmatrelvir retains favorable binding dynamics.

Structural comparisons using pocket‑level views of WT complexes (GC376, NZ804; Supplementary Fig. 6) and global overlays with Mpro‑Δ23G spanning nirmatrelvir, ensitrelvir, simnotrelvir, pomotrelvir, EDP‑235, lufotrelvir, leritrelvir, WU‑04, and S‑892216 (Supplementary Fig. 7) were performed to assess binding specificity. Across this set, Δ23G sensitivity correlates with β‑hairpin (Thr24–Thr26) engagement rather than inhibitor class (covalent/non-covalent; peptidomimetic/small-molecule). Ensitrelvir uniquely forms a direct Thr26 hydrogen bond and is therefore most vulnerable to Δ23G‑driven hairpin displacement (Supplementary Figs. 6d, 7b). For leritrelvir, lufotrelvir, and S‑892216 (red dashed circles) mark the Δ23G‑shifted β‑hairpin neighborhood near certain ligand moieties—a potentially affected region, not evidence of direct Thr26 contact (Supplementary Fig. 7d, h, i). Collectively, Δ23G-driven β-hairpin remodeling preferentially compromises Thr26-dependent (ensitrelvir-like) chemotypes.

Pathogenicity of recombinant SARS-CoV-2 variants in a hamster infection model

To evaluate the impact of Mpro mutations (Δ23G, T45I, and Δ23G/T45I) on SARS-CoV-2 pathogenicity, Syrian golden hamsters were intranasally inoculated with recombinant viruses at 104 TCID50. Mpro-WT-infected hamsters exhibited significant weight loss ( ~ 20% at 7 dpi), recovering gradually from 8 dpi onward (Fig. 4a). In contrast, mutant-infected hamsters displayed milder weight loss ( ~ 5–10%) and earlier recovery. Viral load analysis at 3 and 6 dpi showed substantially reduced replication of the Mpro-Δ23G mutant in both nasal turbinate and lung tissues compared to Mpro-WT (Fig. 4b). However, the Mpro-Δ23G/T45I double mutant exhibited reduced replication predominantly in lung tissues, suggesting that the T45I mutation partially restored viral replication fitness impaired by Δ23G. Histopathological analyses revealed severe tissue damage and abundant viral antigen in nasal turbinate and lungs of hamsters infected with Mpro-WT and Mpro-T45I variants (Supplementary Fig. 8). In contrast, hamsters infected with Δ23G-containing variants exhibited reduced tissue pathology and fewer viral antigen-positive cells, confirming attenuation associated with the Δ23G mutation. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the Mpro-Δ23G mutation significantly attenuates viral pathogenicity and replication in the hamster model, while T45I alone confers moderate attenuation and can partially compensate for Δ23G-associated replication deficits.

a Body-weight change (%) in hamsters (n = 5 per group) infected intranasally with Mpro-WT, Mpro-T45I, Mpro-Δ23G, or Mpro-Δ23G/T45I (104 TCID50); naïve hamsters (n = 5) served as controls. Points show mean ± SD. Statistical comparisons vs WT: T45I, p = 0.0010; Δ23G, p < 0.0001; Δ23G/T45I, p = 0.0023. b Viral titers (TCID50) in nasal turbinate and lung at 3 and 6 dpi (bars, mean ± SD; dots, individual animals; n = 5). c–f Therapeutic efficacy on weight loss (n = 5 per group) for ensitrelvir (ETV) and nirmatrelvir (NTV) in hamsters infected with WT (c), T45I (d), Δ23G (e), or Δ23G/T45I (f). Statistics are shown as AUC (5–8 dpi) vs vehicle: vehicle vs ETV—WT, p = 0.0022; T45I, p = 0.6991; Δ23G, p = 0.3758; Δ23G/T45I, p = 0.2162. vehicle vs NTV—WT, p = 0.0240; T45I, p = 0.8912; Δ23G, p = 0.0244; Δ23G/T45I, p = 0.0069; ns, not significant. ETV/NTV were dosed once daily from infection to 3 dpi; data are mean ± SD. g–j Viral titers (TCID50) at 4 dpi in nasal turbinate and lung following vehicle, ETV, or NTV in WT (g), T45I (h), Δ23G (i), and Δ23G/T45I (j) infections (bars, mean ± SD; dots, n = 5). k–n Representative histopathology from three biological replicates per group with similar results: H&E (left) and IHC (right) for SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid in nasal turbinate and lung from vehicle-, ETV-, and NTV-treated hamsters infected with WT (k), T45I (l), Δ23G (m), or Δ23G/T45I (n). Histologic severity and antigen detection reflect treatment effects; black arrows indicate antigen-positive cells. Scale bars: 500 µm (H&E), 50 µm (IHC). Statistics: one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons for (a, c–f) and the two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli for (b, g–j) to control the false discovery rate. Significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; ns, not significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In vivo antiviral efficacy of ensitrelvir and nirmatrelvir against recombinant SARS-CoV-2 variants

To assess the antiviral efficacy of ensitrelvir and nirmatrelvir in vivo, Syrian golden hamsters were intranasally infected with recombinant SARS-CoV-2 variants (Mpro-WT, Mpro-Δ23G, Mpro-T45I, and Mpro-Δ23G/T45I) at a dose of 104 TCID50, followed by daily antiviral or vehicle treatment until 3 dpi. Vehicle-treated Mpro-WT-infected hamsters exhibited significant weight loss ( ~ 13%) by 7 dpi (Fig. 4c). Treatment with nirmatrelvir or ensitrelvir markedly reduced clinical severity, limiting weight loss to ~ 6% and ~2 %, respectively, confirming their efficacy against WT virus. In animals infected with the Mpro-T45I variant, nirmatrelvir ( ~ 6% weight loss) and ensitrelvir ( ~ 4% weight loss) treatments showed moderate therapeutic effects compared to vehicle control ( ~ 8%) (Fig. 4d). Notably, ensitrelvir demonstrated limited effectiveness against the Δ23G-containing variants (Mpro-Δ23G and Mpro-Δ23G/T45I), resulting in moderately improved weight profiles (Fig. 4e, f). In contrast, nirmatrelvir effectively protected hamsters infected with these variants, substantially minimizing weight loss (0–3%) and enhancing recovery, underscoring their paradoxically increased susceptibility (Fig. 4e, f).

To further quantify antiviral efficacy, viral titers were determined at 4 dpi in nasal turbinate and lung tissues (Fig. 4g–j). Consistent with clinical observations, ensitrelvir significantly reduced viral replication in Mpro-WT and Mpro-T45I-infected hamsters (Fig. 4g, h) but exhibited limited antiviral activity against Δ23G-containing variants (Fig. 4i, j). In contrast, nirmatrelvir suppressed viral replication across all tested variants, particularly in Δ23G-containing variants, demonstrating markedly increased susceptibility (Fig. 4i, j). Histopathological analyses indicated that ensitrelvir and nirmatrelvir treatments reduced tissue damage and viral antigen detection in Mpro-WT- and Mpro-T45I-infected hamsters (Fig. 4k, l). In Δ23G-containing variants, ensitrelvir showed limited improvement, whereas nirmatrelvir treatment significantly decreased pathology and viral antigen staining, aligning with virological results (Fig. 4m, n). Collectively, these findings highlight the robust in vivo resistance conferred by the Mpro-Δ23G mutation against ensitrelvir, coupled with paradoxically enhanced susceptibility to nirmatrelvir, emphasizing critical considerations for managing resistance-associated mutations in therapeutic settings.

Transmissibility of recombinant SARS-CoV-2 variants in hamsters

To evaluate transmissibility and potential circulation risks, Syrian golden hamsters were infected with recombinant SARS-CoV-2 variants (Mpro-WT, Mpro-Δ23G, Mpro-T45I, and Mpro-Δ23G/T45I), and transmission was assessed by direct contact (co-housed) and indirect aerosol-mediated exposure. In direct-contact groups, all variants efficiently transmitted to recipient hamsters, achieving high viral loads ( ~ 106 TCID50/mL) in the nasal turbinate (Fig. 5a, b). However, the single Mpro-Δ23G mutant showed reduced replication in recipient lungs, indicating moderately impaired transmissibility relative to Mpro-WT and Mpro-Δ23G/T45I. In aerosol-mediated transmission assays, Mpro-WT and Mpro-T45I variants efficiently transmitted, yielding consistently high viral titers ( ~ 105–106 TCID50/mL) in recipient nasal turbinate and lungs. Conversely, aerosol transmission of Δ23G-containing mutants (Δ23G and Δ23G/T45I) was significantly impaired, particularly in the lungs, with viral titers markedly reduced ( ~ 103–104 TCID50/mL) (Fig. 5c, d). However, the Mpro-Δ23G/T45I variant demonstrated partial recovery of viral replication in lung tissues at 5 dpc compared to the Mpro-Δ23G mutant (Fig. 5d). These results show that the Δ23G mutation significantly reduces aerosol transmissibility, while the T45I mutation partially compensates for this impairment, highlighting its compensatory role in restoring viral fitness.

a–d Hamsters (n = 5 per group) were inoculated with recombinant SARS-CoV-2 variants: Mpro-WT (Wild-type), Mpro-T45I, Mpro-Δ23G, and Mpro-Δ23G/T45I at 104 TCID50. Viral loads were measured in nasal turbinate (a, c) and lung tissues (b, d) of donor (4 dpi) and recipient hamsters at 3 and 5 days post-contact (dpc). Transmissibility was evaluated through direct contact (a, b) and aerosol-mediated indirect contact (c, d). Data points represent individual animals, and bars indicate means ± SD. Statistical significance was assessed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s mutiple comparisons test, with significance levels indicated. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In vivo competitive fitness and advantage of recombinant SARS-CoV-2 variants under antiviral selection pressure

To evaluate the competitive fitness and stability of antiviral-resistant mutations in vivo, Syrian golden hamsters were co-infected intranasally with equal titers (2 × 104 TCID50) of Mpro-WT and mutant variants (Mpro-Δ23G, Mpro-T45I, or Mpro-Δ23G/T45I), with or without antiviral treatment (ensitrelvir or nirmatrelvir). Viral populations in nasal turbinate and lung tissues were analysed at 4 dpi by NGS (Fig. 6). Without antiviral treatment, the Mpro-T45I variant maintained moderate levels (10–38%), indicating minor fitness impairment, whereas Mpro-WT strongly dominated (93–99%) over Δ23G-containing variants, highlighting their significant fitness cost (Fig. 6a–c). Under ensitrelvir pressure, resistant variants markedly increased, reaching up to 96% dominance (Fig. 6d–f). Conversely, nirmatrelvir treatment favored Mpro-WT dominance ( > 97%) over Δ23G-containing variants due to their paradoxically enhanced susceptibility (Fig. 6h, i). Mpro-T45I exhibited similar competitive fitness with Mpro-WT regardless of nirmatrelvir treatment (Fig. 6a, g). These results demonstrate the critical impact of antiviral selective pressure on the competitive fitness and prevalence of resistant SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Syrian golden hamsters (n = 5 per group) were intranasally co-infected with equal titers (2 × 104 TCID50) of recombinant wild-type SARS-CoV-2 (Mpro-WT) and variants harboring Mpro mutations: T45I (Mpro-T45I, red), Δ23G (Mpro-Δ23G, blue), or Δ23G/T45I (Mpro-Δ23G/T45I, purple). The proportion of each viral variant was quantified in nasal turbinate and lung tissues at 4 days post-infection (dpi) via next-generation sequencing (NGS). Animals were untreated (Absence; panels a–c), or treated with ensitrelvir (panels d–f) or nirmatrelvir (panels g–i). Data are relative proportion of Mpro-WT and variants in the lung and nasal turbinate tissues of infected hamsters. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

Our study identifies and characterizes resistance-associated mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro emerging under selective pressure from ensitrelvir, highlighting distinct antiviral susceptibility profiles. Unlike previously reported mutations that typically confer resistance to one or both inhibitors25,26,28,36, we identified a unique deletion mutation, Mpro-Δ23G, which markedly reduces susceptibility to ensitrelvir but paradoxically increases susceptibility to nirmatrelvir. Consistent with this, ITC, enzymology and mutant structures (with docking and MD simulations) support reduced ensitrelvir binding but preserved nirmatrelvir contacts. This unexpected observation underscores the intricate interplay and complexity of resistance mechanisms within the viral protease, despite the structural similarity of these inhibitors.

Resistance mutations frequently impose fitness costs37,38, influencing the epidemiology of resistant viral variants. Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 harboring the Mpro-Δ23G mutation demonstrated significant fitness impairments in vitro, characterized by reduced replication compared to wild-type virus. In vivo studies further confirmed viral attenuation, evident through diminished pathogenicity and reduced replication in hamster lungs. Although such fitness penalties may naturally limit viral dissemination, compensatory mutations such as Mpro-T45I can partially restore fitness, potentially facilitating the persistence and spread of resistant variants under antiviral selection pressure. The Δ23G mutation emerged in the presence of the T45I mutation (Fig. 1b), which previously demonstrated moderate resistance to ensitrelvir25, consistent with our observations (Fig. 2e). In our study, we additionally observed a compensatory function of T45I, reducing the fitness impairment caused by the Δ23G mutation in terms of viral replication in vitro (Fig. 2h, i) and in vivo (Fig. 4b), and during transmission experiments (Fig. 5). SARS-CoV-2 Mpro exists in a concentration- and condition-dependent monomer–dimer equilibrium essential for catalytic activity. Perturbations at the N-finger or dimer interface can shift this balance toward monomeric forms with residual activity, while dimerization can occur independently of N-terminal processing and can be stabilized by inhibitor binding39,40,41,42. In this context, the Δ23G mutation weakens N-finger–mediated dimerization, whereas the additional T45I substitution partially restores it, consistent with the recovered enzymatic activity and replication competence observed in our assays. Structurally, Mpro-Δ23G crystallized exclusively as a monomer, while Mpro-Δ23G/T45I formed both monomers and the naturally occurring dimeric form29,34,35 and these findings were corroborated by SEC–MALS, which showed a reduced molar mass for Δ23G consistent with monomerization and restoration toward a dimeric mass for Δ23G/T45I (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2b). This observation suggests that the T45I mutation partially restores the ability of Mpro to dimerize, potentially explaining the partial recovery in viral fitness. In addition, Gly23 is highly conserved among coronaviral Mpro proteins43 and the Δ23G deletion imposes a substantial fitness barrier; accordingly, our data indicate that emergence likely requires a compensatory background (e.g., T45I) and sustained ensitrelvir pressure, suggesting a two-step selection pathway.

The paradoxical effect of the Mpro-Δ23G mutation on inhibitor resistance can be explained by structural analyses revealing significant conformational rearrangements, particularly within the β-hairpin loop (Cys22–Thr26) and the catalytic loop (Ile136–Val148). These structural changes notably alter the substrate-binding pocket’s shape and accessibility, disrupting essential stabilizing interactions such as the π-stacking between Phe140 and His163, thereby affecting inhibitor binding affinity. While nirmatrelvir retains its inhibitory potency due to a robust covalent interaction with Cys145, ensitrelvir’s efficacy is substantially compromised because of its specific dependence on interactions with Thr26. Consistent with ITC, ensitrelvir binding to Δ23G was not detectable, and docking and MD simulations predicted unstable complexes between Δ23G and ensitrelvir but stable interactions between Δ23G and nirmatrelvir (Supplementary Figs. 1, 5). This distinct structural adaptability underscores the critical role of active site plasticity in modulating inhibitor selectivity and resistance, offering valuable insights for the rational design of antivirals targeting SARS-CoV-2 Mpro variants.

The Mpro-Δ23G mutation emerged and became predominant under antiviral selection pressure (Fig. 6). Genetic stability assessments through repeated passages in vitro demonstrated stable retention of this mutation even in inhibitor-free conditions (Supplementary Fig. 9), suggesting a risk for emergence and persistence in patients receiving prolonged ensitrelvir treatment. This scenario is particularly concerning for immunocompromised or high-risk individuals, in whom prolonged or suboptimal antiviral exposure may favor the selection and establishment of resistant variants, potentially complicating management.

However, the inherent fitness cost associated with the Mpro-Δ23G mutation was clearly evident, as wild-type virus consistently outcompeted Δ23G-containing mutants in the absence of ensitrelvir selection (Fig. 6b, c). Animal transmission studies confirmed this reduced fitness, showing significantly impaired transmissibility of Δ23G-containing variants, especially through aerosol-mediated spread. This limited transmissibility suggests a low likelihood of natural circulation of Δ23G variants without antiviral pressure. In contrast, under ensitrelvir selection, Δ23G variants rapidly dominated over wild-type viruses, highlighting their potential for enrichment during antiviral therapy (Fig. 6d–f). Notably, the inverse susceptibility observed with nirmatrelvir treatment indicates that alternating or sequential antiviral regimens could effectively mitigate resistant variant emergence and spread in clinical settings.

Although both Mpro-T45I and Δ23G mutations were identified in global SARS-CoV-2 genomic data, Δ23G was relatively rare, found in only two isolates (Supplementary Fig. 10). Nonetheless, despite its limited current prevalence, the clinical implications of this resistance mutation cannot be overlooked. We did not systematically map compensatory or interacting changes beyond T45I, which may influence fitness and resistance in clinical settings. Whole‑genome sequencing of passaged populations identified recurrent non‑Mpro substitutions in the Wuhan‑like background (Supplementary Table 2); however, none has an established role in protease‑inhibitor resistance or a defined compensatory function in prior clinical or experimental reports44,45. These changes, therefore, warrant further evaluation. Omicron Mpro differs from WT by a single substitution (P132H) located ~ 22 Å from Cys145 at the domain II–III interface, and it does not perturb active‑site geometry, catalysis, or small‑molecule inhibition46. Accordingly, the Δ23G mechanism, with its opposite effects on ensitrelvir versus nirmatrelvir, is expected to generalize to an Omicron background, although confirmation in an Omicron genetic background would be valuable. Finally, viral passaging under escalating ensitrelvir concentrations was performed in IFN‑deficient Vero E6 cells47, and in vivo fitness/transmission were assessed in immunocompetent hamsters; immunocompromised animal models will be prioritized in future studies focused on resistance emergence under prolonged therapy.

In conclusion, our findings provide critical mechanistic insights into ensitrelvir resistance, emphasizing the importance of continuous monitoring for resistance mutations during antiviral therapy. The discovery of an ensitrelvir-resistant variant with increased susceptibility to nirmatrelvir highlights potential therapeutic opportunities involving sequential or combination antiviral treatments. Ongoing surveillance and characterization of resistance mutations are essential for informing therapeutic strategies and public health responses aimed at controlling the emergence and dissemination of antiviral-resistant SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Methods

Ethics

Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (CBUNA-24-0012-02) at Chungbuk National University, Republic of Korea. All experiments involving infectious SARS-CoV-2 were conducted within an approved Biosafety Level 3-plus (BSL-3 + ) facility at Chungbuk National University, following procedures and guidelines approved by Chungbuk National University, the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety of the Republic of Korea, and the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Cells and viruses

Vero E6 cells (African green monkey kidney cells, ATCC®, Cat# CRL-1586™) and BHK-21 cells (Baby hamster kidney cells, KCBL, C-13) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 4.0 mM L-glutamine, 110 mg/L sodium pyruvate, 4.5 g/L D-glucose, and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Anti-Anti; Gibco) at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

The SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-like strain (Beta-Cov/Korea/KCDC03/2020) and the BA.5 Omicron variant (hCoV-19/South Korea/KDCA43426/2022) were obtained from the National Culture Collection for Pathogens (Republic of Korea). Viruses were propagated in Vero E6 cells maintained in DMEM containing 2% FBS and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution at 37 °C and 5% CO2. All SARS-CoV-2-related infection experiments were performed in BSL-3 laboratory facilities at Chungbuk National University in accordance with institutional biosafety guidelines and ethical standards.

Antivirals

Ensitrelvir (S-217622), nirmatrelvir (PF-07321332), molnupiravir (EIDD-1931), and remdesivir (GS-441524) were purchased from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, USA). Compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for in vitro experiments or in 0.5% (w/v) methylcellulose for in vivo experiments immediately before use.

Selection of ensitrelvir-resistant SARS-CoV-2 variants

SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-like (Beta-Cov/Korea/KCDC03/2020) and BA.5 Omicron (hCoV-19/South Korea/KDCA43426/2022) strains were serially passaged in Vero E6 cells under increasing concentrations of ensitrelvir (1, 2, 4, 8, and 16 μM). Initially, Vero E6 cells seeded in T25 flasks were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 for 1 hour at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After incubation, inoculum was replaced with DMEM containing 2% FBS and the designated concentration of ensitrelvir. Cultures were monitored daily for cytopathic effect (CPE), and viral supernatants were harvested when CPE reached approximately 90%. Viral titers were quantified by median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assays. Following 4–5 passages under ensitrelvir selective pressure, isolated viruses were analysed for resistance by determining the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) using antiviral assays. Viral RNA was extracted from culture supernatants using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany), mutations were identified through next-generation sequencing (NGS; DNALINK, Republic of Korea), and genomic sequences were analysed using CLC Genomics Workbench software (Qiagen, Germany).

Generation of ensitrelvir-resistant recombinant SARS-CoV-2 variants

For site-direct mutagenesis, primers used to generate the Mpro mutations were: T45I—forward, 5′-AAGACATGTGATCTGCATCTCTGAAGACATGCTTAA-3′; reverse, 5′-CAGATCACATGTCTTGGACAGTAAACTA-3′. Δ23G—forward, 5′-TATGGTACAAGTAACTTGTACAACTACACTTAACGGTCTT-3′; reverse, 5′-GTTACTTGTACCATACAACCCTCAACTTTA-3′. Mutations were introduced by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis and verified by sequencing. Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-like viruses carrying resistance-associated mutations (Mpro-T45I, -Δ23G, and -Δ23G/T45I) were generated using a circular polymerase extension cloning (CPEC)-based reverse genetics system48. Briefly, linearized SARS-CoV-2 genomic RNA and N gene RNA transcripts, produced via in vitro transcription, were transfected into BHK-21 cells by electroporation. Electroporated cells were co-cultured with Vero E6 cells in T-75 flasks until more than 90% cytopathic effect was observed. Culture supernatants were then collected, passaged in fresh Vero E6 cells, and sequenced using NGS to confirm the presence of desired mutations and absence of unintended mutations. For lineage‑level analyses, “recurrent” variants were defined as those present at high frequency in ≥ 2% independent lineages within the same genetic background.

Antiviral IC50 determination

The antiviral efficacy (IC50) of compounds was evaluated in Vero E6 cells seeded in 96-well plates (1.5 × 104 cells/well). Cells were infected with 100 TCID50 of SARS-CoV-2 (Wuhan-like strain or recombinant variants) for 1 hour at 37 °C. Following infection, the virus-containing media was replaced with fresh DMEM containing 2% FBS and serially diluted antivirals. After 96 hours of incubation, cell viability was assessed using CellTiter-Glo (Promega), and IC50 values were calculated using nonlinear regression analysis with GraphPad Prism 10 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Resistance levels were classified by fold-change in IC50 relative to the matched wild-type background (Wuhan-like WT or BA.5 WT) as follows: no shift ( > 0.33– < 3-fold increase), low-level ( ≥ 3– < 6-fold), intermediate ( ≥ 6– < 30-fold), and high-level ( ≥ 30-fold). Increased susceptibility was defined as a ≥ 3-fold decrease in IC50 ( ≤ 0.33-fold vs WT).

In vitro growth kinetics

Vero E6 cells were infected with recombinant viruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.001. After a 1-hour incubation at 37 °C, the inoculum was replaced with DMEM containing 2% FBS with or without inhibitors (10 μM ensitrelvir or 20 μM nirmatrelvir). Culture supernatants were collected at 12-hour intervals up to 120 hours post-infection, and viral titers were quantified using the TCID50 method based on the Reed-Muench calculation49.

Protein expression and purification

SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (residues 3264-3569, Swiss Prot: P0DTD1) and mutants (T45I, Δ23G, Δ23G/T45I) were cloned into the pET-32a vector (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA), which includes an N-terminal thioredoxin and hexahistidine (His6) tag to facilitate purification. Mutations were generated via site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange method (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) and confirmed by DNA sequencing. Recombinant plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) codon plus RIL cells (Agilent) for protein expression. Bacterial cultures were grown in LB media containing ampicillin (100 μg/mL) at 37 °C until an optical density (OD600) of approximately 0.6-0.8 was reached, at which point protein expression was induced by adding isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.1 mM. Induction was carried out overnight at 18 °C.

Following induction, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 12,074 × g for 20 minutes at 4 °C. Cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 400 mM NaCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and disrupted by sonication. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 32,550 × g for 40 minutes at 4 °C. The clarified supernatant was applied to a nickel-affinity chromatography column (HiTrap Chelating HP, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) pre-equilibrated with binding buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 400 mM NaCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Bound proteins were eluted using a gradient of imidazole (25–500 mM) in the binding buffer. Eluted fractions were further purified by size-exclusion chromatography using HiLoad 26/60 Superdex-75 and Superdex-200 columns (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA), equilibrated in buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Protein purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE (15% gel). Purified proteins were concentrated to 10 mg/mL using centrifugal filters (Vivaspin20, Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany) and stored at -80 °C until further use.

Enzymatic activity and inhibition assays

Protease activity was assessed using a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based substrate (DABCYL-KTSAVLQ/SGFRKME-EDANS-NH2, BPS Bioscience). Assays were conducted at 37 °C in assay buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTT. For steady-state kinetic analyses, reactions were performed in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTT with purified Mpro at 60 nM (WT, T45I) or 120 nM (Δ23G, Δ23G/T45I) and substrate varied from 2.5–100 μM; fluorescence (Ex 380 nm/Em 460 nm) was recorded every 60 s for 60 min, initial velocities (V0) were fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation in GraphPad Prism 10, and kcat was calculated as Vmax/[E]0. For IC50 determinations, reaction mixtures included purified Mpro variants (40 nM for WT and T45I; 80 nM for ∆23G and ∆23G/T45I), 40 μM substrate, and varying concentrations of inhibitors (0.0015–3.12 μM of nirmatrelvir or ensitrelvir). Fluorescence intensity was measured at an excitation wavelength of 380 nm and emission wavelength of 460 nm every 45 seconds for 90 minutes using a SpectraMax M3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). Inhibition percentages were determined relative to control reactions containing DMSO only. IC50 values and standard deviations were calculated from triplicate experiments using nonlinear regression analysis in GraphPad Prism 10 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

ITC experiments were performed at 25 °C using a MicroCal ITC200 instrument (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK). Mpro variant proteins (WT, Δ23G, T45I, and Δ23G/T45I) were used at a concentration of 30 μM in the sample cell, while the syringe contained 300 μM of nirmatrelvir or ensitrelvir. Proteins were dialyzed into buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP, and 2% (v/v) DMSO. Nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir were prepared in the identical buffer to ensure matching excipients. To ensure comparability, the final DMSO concentration was strictly maintained at 2% (v/v) in both the protein and ligand solutions. All samples were centrifuged and degassed at 25 °C prior to titration. Titrations were performed with 2 μL injections at 150-second intervals. Thermodynamic parameters, including stoichiometry (n), dissociation constant (KD), and enthalpy change (ΔH), were obtained by nonlinear least-squares fitting. Heats of dilution were corrected using buffer-into-buffer controls, and data were fit to a one-site binding model in Origin 7.0 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA).

Size-exclusion chromatography with multi-angle light scattering (SEC–MALS)

SEC–MALS was performed using a high-performance liquid chromatography system (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) equipped with a DAWN HELEOS multi-angle light scattering detector and an Optilab rEX refractive index detector (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA, USA). The scattering data were analyzed with ASTRA software (version ASTRA 7, Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA). Approximately 1.5 mg of Mpro variant proteins (WT, Δ23G, T45I, and Δ23G/T45I) were injected per run. Chromatographic separation was carried out using a Superose 6 Increase 10/300 GL column (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) equilibrated with buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT, at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min at 25 °C. Samples were clarified by brief centrifugation and 0.22 μm filtration prior to injection. Absolute molar mass across elution peaks was calculated in ASTRA software (version ASTRA 7) using the Zimm model with a protein refractive index increment (dn/dc) of 0.185 mL·g-1; protein concentration was obtained from the RI signal.

Crystallization

Diffraction-quality crystals of Mpro variants were obtained by mixing purified protein (10 mg/mL) in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTT with reservoir solutions containing 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.5), 8% (v/v) ethylene glycol, and 10% (w/v) PEG 8000. Crystals formed after incubation for three days at 20 °C. For inhibitor-bound structures, proteins were pre-incubated with nirmatrelvir at a 1:5 molar ratio for 4 hours at 4 °C. Crystals of Mpro-∆23G:nirmatrelvir and Mpro-∆23G/T45I:nirmatrelvir complexes were grown in reservoir solutions containing 100 mM imidazole (pH 8.0), 10% (w/v) PEG 8000, and 200 mM ammonium acetate, 20% (w/v) PEG 3350, respectively. Crystals were cryo-protected with reservoir solution supplemented with 25% glycerol and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Diffraction data collection and processing

Diffraction data were collected at −173 °C on beamline BL-5C of Pohang Light Source (Pohang, Korea) equipped with an ADSC Quantum 315r CCD detector. Data were processed using DENZO and SCALEPACK from the HKL2000 suite (HKL2000 v717.1)50.

Structure determination and analysis

The crystal structures were determined by the molecular replacement method using PHENIX software (version 1.21.2-5419)51, with the crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (PDB ID: 6Y2E) as the search model29. Iterative manual model building was performed in COOT (version 0.6)52, and subsequent refinement was carried out with PHENIX (version 1.21.2-5419). Model quality and stereochemical validation were assessed using MolProbity (version 4.02-528)53. Structural figures were prepared using PyMOL (http://pymol.org, accessed on 3 May 2022, version 0.99). Solvent-accessible surfaces and interface areas were calculated with PISA (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/pisa/, version 1.48). Sequence alignments were performed with ClustalW and visualized using ESPript 3.0 (https://espript.ibcp.fr/, version 3.0 3.0.24). Detailed data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Docking study

Molecular docking studies were conducted using the co-crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with ensitrelvir (PDB: 8HBK) and the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro-Δ23G mutant. Protein structures were prepared using the Prepare Protein module in BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2024 (version Client, v24.1) (Dassault Systèmes) with the CHARMm force field, including addition of hydrogens and removal of active-site water molecules. The binding site was defined by the centroid of the co-crystallized ligand (ensitrelvir). Ligands (ensitrelvir and nirmatrelvir) were prepared using rule-based protonation (pH 7.4) and energy minimization in Discovery Studio. Molecular docking was performed using CDOCKER (Discovery Studio 2024; CHARMm docking algorithm). Up to ten docking poses per ligand were retained for subsequent binding analysis. For nirmatrelvir (a covalent inhibitor), docking evaluated the non-covalent pre-reaction pose.

Molecular dynamic simulation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted to investigate the binding stability and interaction profiles of protein complexes with two ligands: ensitrelvir and nirmatrelvir. The protein-ligand complexes, derived from docking results, were prepared using BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2024 (Dassault Systèmes). Each complex was parameterized with the CHARMm force field and placed in an orthorhombic simulation box, ensuring a minimum distance of 7 Å between the solute and box edges. The systems were solvated with explicit TIP3P water molecules, and appropriate counterions were added to neutralize charges. Energy minimization was performed using the Smart Minimizer algorithm, followed by heating protocol to reach 300 K. Equilibration was then carried out at a constant temperature (300 K) for 1 ns, and the final configurations were exported in Discovery Studio formats.

Production MD simulations were run for 1 ns under periodic boundary conditions using the NPT ensemble (300 K, 1 atm) in Discovery Studio 2024. Data were recorded every 2 ps, with long-range electrostatics handled by the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method54. A 2 fs time step with SHAKE constraints on bonds to hydrogens was applied. Trajectory analyses were performed to evaluate the root mean square deviation (RMSD)55, root mean square fluctuation (RMSF)56, and key interaction profiles between SARS-CoV-2 WT/mutant and the ligands (ensitrelvir and nirmatrelvir).

Hamster experiments

Five-to-six-week-old male Syrian hamsters (SLC, Japan) were used in this study. Hamsters (n = 15 per group) were anesthetized with isoflurane and intranasally inoculated with 10⁴ TCID50 of each specified virus in 100 μL volume. Five animals per group were monitored daily for body weight changes until 14 days post-infection (dpi). The remaining hamsters were euthanized at 3 dpi (n = 5) and 6 dpi (n = 5) to collect nasal turbinate and lung tissues for viral titration and histopathological analysis. Viral titers were quantified by TCID50 assays using Vero E6 cells.

For antiviral susceptibility assessments, hamsters (n = 10 per group) were intranasally inoculated with 10⁴ TCID50 of each virus variant. From 1 dpi to 3 dpi, animals were orally administered either 60 mg/kg ensitrelvir (n = 10), 250 mg/kg nirmatrelvir (n = 10), or vehicle control (n = 10), twice daily57,58. Five animals per treatment group were euthanized at 4 dpi for the collection of nasal turbinate and lung tissues to determine viral titers and conduct histopathological evaluations. The remaining five animals per group were monitored daily for body weight changes up to 14 dpi.

For direct transmission studies, a donor hamster (n = 1 per variant) was intranasally inoculated with 10⁴ TCID50 of each virus. At 1 dpi, inoculated donors were co-housed with naïve recipient hamsters (n = 2 per donor). Donor and recipient animals were euthanized at 4 dpi (or 3 days post-contact, dpc) and 5 dpc, with nasal turbinate and lung tissues collected for viral titration. Indirect (aerosol-mediated) transmission was evaluated similarly, with donor and recipient animals placed in adjacent cages separated by physical partitions. These transmission experiments were replicated using five donor-to-recipient sets (1:2 ratio) per group.

For co-infection studies, wild-type (Mpro-WT) virus was mixed with mutant variants (Mpro-Δ23G, T45I, or Δ23G/T45I) at a 1:1 ratio based on TCID50 titers. Hamsters (n = 5 per group) were intranasally inoculated with a total dose of 2 × 104 TCID50 virus mixture. From 1 dpi, animals were administered either ensitrelvir (60 mg/kg, n = 5), nirmatrelvir (250 mg/kg, n = 5), or vehicle control (n = 5) twice daily57,58. All animals were euthanized at 4 dpi, and nasal turbinate and lung tissues were analysed by NGS to determine the relative frequencies of WT and mutant viruses. Samples with sequencing read depths greater than 80,000 were selected for analysis.

Histopathology

Hamster nasal turbinate and lung tissues were harvested at 3, 4, or 6 dpi and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). Nasal turbinate tissues were removed from bone, decalcified with 10% EDTA solution, and embedded in paraffin. Lung tissues were similarly processed without decalcification. Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and examined microscopically by a veterinary pathologist. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for viral antigen was performed using a rabbit anti-SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid polyclonal antibody (Sino Biological, Beijing, China, Cat#40143-R019) on an automated Ventana Discovery Ultra staining system (Roche, USA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). One-way ANOVA followed by two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli was performed to assess the significance among the tissue titers in pathogenicity and antiviral susceptibility of recombinant viruses while controlling the false discovery rate. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed to assess the significance among the AUC (0–72 hpi) of growth kinetics. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparsions test was performed to assess the signification among the transmission efficiency. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was performed to assess the significance among the AUC (5–8 dpi) of weight change in the pathogenicity and antiviral susceptibility of recombinant viruses in vivo. Significant differences were indicated by P-values of * p < 0.05; **, ## p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The Crystal structural data generated in this study have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank database under accession codes 9M9N (Mpro-∆23G, https://www.rcsb.org/structure/9M9N), 9M9R (Mpro-∆23G:nirmatrelvir, https://www.rcsb.org/structure/9M9R), 9MA3 (Mpro-∆23G/T45I:nirmatrelvir in C2 space group, https://www.rcsb.org/ structure/9MA3), and 9MA6 (Mpro-∆23G/T45I:nirmatrelvir in P21 space group, https://www.rcsb.org/structure/9MA6). They are available at the http://www.rcsb.org. The NGS raw data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI SRA database under accession code PRJNA1301595 accession codes (title: “A SARS-CoV-2 Mpro mutation conferring ensitrelvir resistance paradoxically increases nirmatrelvir susceptibility”, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1301595). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Further information and requests for data that support the findings of this study are available for Min-Suk Song (songminsuk@chungbuk.ac.kr) or Sang Chul Shin (scshin84@kist.re.kr) upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Chaudhary, N., Weissman, D. & Whitehead, K. A. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 817–838 (2021).

Meyer, C. et al. Small-molecule inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 NSP14 RNA cap methyltransferase. Nature 637, 1178–1185 (2025).

Dolgin, E. Pan-coronavirus vaccine pipeline takes form. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 324–326 (2022).

Phillips, N. The coronavirus is here to stay - here’s what that means. Nature 590, 382–384 (2021).

Ao, D. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: Immune escape and vaccine development. MedComm 3, e126 (2022).

Hachmann Nicole, P., Miller, J., Collier Ai-ris, Y. & Barouch Dan, H. Neutralization Escape by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Subvariant BA.4.6. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 1904–1906 (2022).

Cho, J. et al. Evaluation of antiviral drugs against newly emerged SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants. Antivir. Res. 214, 105609 (2023).

Iketani, S. & Ho, D. D. SARS-CoV-2 resistance to monoclonal antibodies and small-molecule drugs. Cell Chem. Biol. 31, 632–657 (2024).

Uraki, R. et al. Efficacy of antivirals and bivalent mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 isolate CH.1.1. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 525–526 (2023).

Unoh, Y. et al. Discovery of S-217622, a Noncovalent Oral SARS-CoV-2 3CL Protease Inhibitor Clinical Candidate for Treating COVID-19. J. Medicinal Chem. 65, 6499–6512 (2022).

Lamb, Y. N. Nirmatrelvir Plus Ritonavir: First Approval. Drugs 82, 585–591 (2022).

Kabinger, F. et al. Mechanism of molnupiravir-induced SARS-CoV-2 mutagenesis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 28, 740–746 (2021).

Kokic, G. et al. Mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 polymerase stalling by remdesivir. Nat. Commun. 12, 279 (2021).

Shimazu, H. et al. Clinical experience of treatment of immunocompromised individuals with persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection based on drug resistance mutations determined by genomic analysis: a descriptive study. BMC Infect. Dis. 23, 780 (2023).

Hirotsu, Y. et al. Multidrug-resistant mutations to antiviral and antibody therapy in an immunocompromised patient infected with SARS-CoV-2. Med 4, 813–824.e814 (2023).

Zuckerman, N. S., Bucris, E., Keidar-Friedman, D., Amsalem, M. & Brosh-Nissimov, T. Nirmatrelvir Resistance—de Novo E166V/L50V Mutations in an Immunocompromised Patient Treated With Prolonged Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir Monotherapy Leading to Clinical and Virological Treatment Failure—a Case Report. Clin. Infect. Dis. 78, 352–355 (2024).

Uehara, T. et al. Ensitrelvir treatment–emergent amino acid substitutions in SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro detected in the SCORPIO-SR phase 3 trial. Antivir. Res. 236, 106097 (2025).

Duan, Y. et al. Molecular mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 resistance to nirmatrelvir. Nature 622, 376–382 (2023).

Uraki, R. et al. Antiviral and bivalent vaccine efficacy against an omicron XBB.1.5 isolate. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 402–403 (2023).

Uraki, R. et al. Characterization and antiviral susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2. Nature 607, 119–127 (2022).

Sasaki, M. et al. S-217622, a SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitor, decreases viral load and ameliorates COVID-19 severity in hamsters. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eabq4064 (2023).

Shimizu, R. et al. A Phase 1 Study of Ensitrelvir Fumaric Acid Tablets Evaluating the Safety, Pharmacokinetics and Food Effect in Healthy Adult Populations. Clin. Drug Investig. 43, 785–797 (2023).

Shimizu, R. et al. Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of the Novel Antiviral Agent Ensitrelvir Fumaric Acid, a SARS-CoV-2 3CL Protease Inhibitor, in Healthy Adults. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 66, e00632–00622 (2022).

Mukae, H. et al. Ensitrelvir as a novel treatment option for mild-to-moderate COVID-19: a narrative literature review. Therapeutic Adv. Infect. Dis. 12, 20499361251321724 (2025).

Moghadasi, S. A. et al. Transmissible SARS-CoV-2 variants with resistance to clinical protease inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 9, eade8778 (2022).

Moghadasi, S. A., Biswas, R. G., Harki, D. A. & Harris, R. S. Rapid resistance profiling of SARS-CoV-2 protease inhibitors. npj Antimicrobials Resistance 1, 9 (2023).

Kiso, M. et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of SARS-CoV-2 resistance to ensitrelvir. Nat. Commun. 14, 4231 (2023).

Iketani, S. et al. Multiple pathways for SARS-CoV-2 resistance to nirmatrelvir. Nature 613, 558–564 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science 368, 409–412 (2020).

Medrano, F. J. et al. Peptidyl nitroalkene inhibitors of main protease rationalized by computational and crystallographic investigations as antivirals against SARS-CoV-2. Commun. Chem. 7, 15 (2024).

Zhou, X. et al. Structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease in the apo state. Sci. China Life Sci. 64, 656–659 (2021).

Tran, N. et al. The H163A mutation unravels an oxidized conformation of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Nat. Commun. 14, 5625 (2023).

Noske, G. D. et al. A Crystallographic Snapshot of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Maturation Process. J. Mol. Biol. 433, 167118 (2021).

Silvestrini, L. et al. The dimer-monomer equilibrium of SARS-CoV-2 main protease is affected by small molecule inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 11, 9283 (2021).

Goyal, B. & Goyal, D. Targeting the Dimerization of the Main Protease of Coronaviruses: A Potential Broad-Spectrum Therapeutic Strategy. ACS Combinatorial Sci. 22, 297–305 (2020).

Heilmann, E. et al. SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro mutations selected in a VSV-based system confer resistance to nirmatrelvir, ensitrelvir, and GC376. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eabq7360 (2023).

Herlocher, M. L. et al. Influenza Viruses Resistant to the Antiviral Drug Oseltamivir: Transmission Studies in Ferrets. J. Infect. Dis. 190, 1627–1630 (2004).

Zhou, Y. et al. Nirmatrelvir-resistant SARS-CoV-2 variants with high fitness in an infectious cell culture system. Sci. Adv. 8, eadd7197 (2022).

Nashed, N. T., Aniana, A., Ghirlando, R., Chiliveri, S. C. & Louis, J. M. Modulation of the monomer-dimer equilibrium and catalytic activity of SARS-CoV-2 main protease by a transition-state analog inhibitor. Commun. Biol. 5, 160 (2022).

Zhong, N. et al. Without its N-finger, the main protease of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus can form a novel dimer through its C-terminal domain. J. Virol. 82, 4227–4234 (2008).

Noske, G. D. et al. An in-solution snapshot of SARS-COV-2 main protease maturation process and inhibition. Nat. Commun. 14, 1545 (2023).

Paciaroni, A. et al. Stabilization of the dimeric state of SARS-CoV-2 main protease by GC376 and nirmatrelvir. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 6062 (2023).

Xiong, M. et al. What coronavirus 3C-like protease tells us: From structure, substrate selectivity, to inhibitor design. Medicinal Res. Rev. 41, 1965–1998 (2021).

Raglow, Z. et al. SARS-CoV-2 shedding and evolution in patients who were immunocompromised during the omicron period: a multicentre, prospective analysis. Lancet Microbe 5, e235–e246 (2024).

Gularte, J. S. et al. Viral isolation allows characterization of early samples of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B1.1.33 with unique mutations (S: H655Y and T63N) circulating in Southern Brazil in 2020. Braz. J. Microbiol 53, 1313–1319 (2022).

Sacco, M. D. et al. The P132H mutation in the main protease of Omicron SARS-CoV-2 decreases thermal stability without compromising catalysis or small-molecule drug inhibition. Cell Res. 32, 498–500 (2022).

Emeny, J. M. & Morgan, M. J. Regulation of the interferon system: evidence that Vero cells have a genetic defect in interferon production. J. Gen. Virol. 43, 247–252 (1979).

Kim Beom, K. et al. A rapid method for generating infectious SARS-CoV-2 and variants using mutagenesis and circular polymerase extension cloning. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e03385–03322 (2023).

Reed, L. J. & Muench, H. A SIMPLE METHOD OF ESTIMATING FIFTY PER CENT ENDPOINTS12. Am. J. Epidemiol. 27, 493–497 (1938).

Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. in Methods in Enzymology Vol. 276 307-326 (Academic Press, 1997).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. 66, 213–221 (2010).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Chen, V. B. et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. 66, 12–21 (2010).

Huang, J. et al. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods 14, 71–73 (2017).

Kroemer, R. T. et al. Assessment of Docking Poses: Interactions-Based Accuracy Classification (IBAC) versus crystal structure deviations. J. Chem. Inf. Computer Sci. 44, 871–881 (2004).

Dong, Y.-W., Liao, M. -l, Meng, X. -l & Somero, G. N. Structural flexibility and protein adaptation to temperature: Molecular dynamics analysis of malate dehydrogenases of marine molluscs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115, 1274–1279 (2018).

Kuroda, T. et al. Efficacy comparison of 3CL protease inhibitors ensitrelvir and nirmatrelvir against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro and in vivo. J. Antimicrobial Chemother. 78, 946–952 (2023).

Abdelnabi, R. et al. The oral protease inhibitor (PF-07321332) protects Syrian hamsters against infection with SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Nat. Commun. 13, 719 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at Pohang Light Source for assistance during data collection and sincerely appreciate the invaluable support of the Technology Convergence Support Center and Chang-Reung Park in molecular modeling for this research. This work was supported by the Korea National Institute of Health, the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (6634-325-320-01 to M.-S.S.), the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MISP) (RS-2021-NR059195 and RS-2020-NR049557 to M.-S.S.), and a grant from the Korean ARPA-H Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (RS-2024-00512595 to S.C.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C.M., Y.H.B., Y.K.C., H.N.C., S.C.S., and M.-S.S.; Methodology, S.C.M., J.-J.S., J.H.J., B.K.K., J.-H.P., J.R.L., D.G.L., G.C.L., S.H.A., Y.H.B., H.Y.P., G.M.K., B.S.J., S.C.S., and M.-S.S.; Investigation, S.C.M., J.-J.S., J.H.J., B.K.K., J.-H.P., J.R.L., D.G.L., G.C.L., S.H.A., Y.H.B., and B.S.J.; Visualization, S.C.M., J.-J.S., S.C.S., and M.-S.S.; Validation, S.C.M., J.-J.S., J.H.J., B.K.K., J.-H.P., J.R.L., D.G.L., G.C.L., S.H.A., Y.H.B., Y.K.C., H.N.C., H.Y.P., G.M.K., B.S.J., S.C.S., and M.-S.S.; Funding acquisition, S.C.S. and M.-S.S.; Project administration, S.C.S. and M.-S.S.; Data curation: S.C.M. and J.-J.S.; Formal analysis, S.C.M., J.-J.S.; Supervision, S.C.S. and M.-S.S.; Resources, Y.K.C., H.N.C., S.C.S., and M.-S.S.; Writing – original draft, S.C.S. and M.-S.S.; Writing – review & editing, S.C.M., J.-J.S., S.C.S., and M.-S.S.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Min, S.C., Seo, JJ., Jeong, J.H. et al. A SARS-CoV-2 Mpro mutation conferring ensitrelvir resistance paradoxically increases nirmatrelvir susceptibility. Nat Commun 16, 10737 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65767-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65767-z