Abstract

Degradation of complex dietary fiber by gut microbes is essential for colonic fermentation, short-chain fatty acid production, and microbiome function. Ruminococcus bromii is the primary resistant starch (RS) degrader in humans, which relies on the amylosome, a specialized cell-bound enzymatic complex. To unravel its architecture, function, and the interplay among its components, we applied a holistic multilayered approach: Cryo-electron tomography reveals that the amylosome comprises a constitutive extracellular layer extending toward the RS substrate. Proteomics demonstrates remodeling of its contents across different growth conditions, with Amy4 and Amy16 comprising 60% of the amylosome in response to RS. Structural and biochemical analyses reveal complementarity and synergistic RS degradation by these enzymes. We demonstrate that amylosome composition and RS degradation are regulated at two levels: structural constraints and expression-driven shifts in enzyme proportions enforce enzyme proximity, which allows R. bromii to fine-tune its adaptation to dietary fiber and shape colonic metabolism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dietary fiber is essential for promoting a diverse and balanced human microbiome, which in turn enhances metabolic function, reduces inflammation, and protects against chronic diseases1,2. Dietary fibers are composed of various carbohydrates that are indigestible to the human host and remain structurally intact until they reach the lower gastrointestinal tract, where they undergo microbial fermentation. Dietary fiber carbohydrates are degraded by specialized microbes into simple sugars fueling the entire microbial community3. This process plays a crucial role in microbiome-host interactions, by producing metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which promote host health4.

Resistant starch (RS) is a major dietary fiber component, whose fermentation has been linked to various health benefits, including improved insulin sensitivity5, reduced risk of colorectal cancer6, protection against infectious diarrhea7, reduced inflammation in chronic kidney disease8, and enhanced glucose control and satiety9. RS typically forms large, insoluble granules that, like other dietary fibers, cannot be degraded by human enzymes. Instead, its breakdown relies entirely on microbial fermentation, during which RS is converted into simpler sugars that fuel both RS-degrading bacteria and secondary consumers in the gut microbiome.

To date, only a few bacterial species have been identified as RS degraders in the human gut, the major species being Ruminococcus bromii and Bifidobacterium adolescentis10. Among them, R. bromii is the dominant degrader, accounting for 80% of RS-adherent bacteria in human fecal samples11 and outcompeting B. adolescentis on a wide range of recalcitrant substrates12. While B. adolescentis may respond more strongly to certain starches such as raw potato starch13,14, R. bromii remains central to RS breakdown in the human gut. This positions R. bromii as the keystone species for RS degradation in the gut12, enabling metabolic cross-feeding that supports the growth of other microbiota members, such as Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron15 and Ruminococcus gnavus16. R. bromii abundance is associated with multiple health benefits, including enhanced response to cancer immunotherapy17, protection against chronic kidney disease18, and reduced risk of depressive disorders19. Some of these benefits stem from its ability to stimulate production of SCFAs, particularly butyrate20, a key regulator of immune function and inflammation4.

The ability of R. bromii to efficiently deconstruct RS while simultaneously supporting the broader gut ecosystem is attributed to a cell-adjacent protein complex known as the amylosome21. While early studies inferred the potential role of this complex in RS degradation using R. bromii cell extracts, the precise function of its components and how they interact with RS remain unclear. Structurally, the amylosome resembles the well-characterized cellulosome22, exhibiting a high degree of adaptability. It consists of two protein groups: (i) the scaffoldins, which contain cohesin domains and serve as structural organizers, either attaching to the cell wall or remaining free in the extracellular space, and (ii) the dockerin-containing proteins, which bind to the scaffoldins via specific cohesin-dockerin interactions and include key carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes)23.

Genomic analyses have identified five scaffoldins (Sca1–Sca5) and 27 dockerin-containing proteins in R. bromii21,24. Among them, five dockerin-containing proteins—Amy4, Amy9, Amy10, Amy12, and Amy16—also contain CAZyme domains, rendering them primary candidates for RS degradation. One enzyme, Amy4 (also known as Sca1), exhibits a unique dual-domain architecture, possessing both a cohesin and a dockerin domain, thereby functioning as both a scaffoldin and a glycoside hydrolase family 13 (GH13) α-amylase. This structural duality suggests that Amy4 plays a central role in amylosome assembly and function. The ability of Amy4 to homo-polymerize through intermolecular cohesin-dockerin interactions may further contribute to amylosome organization and enzyme recruitment. The scaffoldins Sca2 and Sca5 have a sortase recognition motif, indicating that they are anchored to the cell wall, while Sca3 and Sca4 are presumed to be in the cell-free state.

Among the dockerin-containing proteins, the five amylosomal CAZymes underwent preliminary characterization for their substrate preferences: Amy4, Amy9, and Amy16 exhibited amylase activity, while Amy10 and Amy12 acted as pullulanases24. Further characterization of Amy10 and Amy12 indicated that they produce maltotriose from pullulan, and revealed the mechanism of action for Amy1225. Key carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs) of the starch-adherence systems, Sas626 and Sas2027, were also characterized for their structure and binding behavior. Sas20 is especially notable, as it is consistently among the most highly expressed amylosome proteins and binds exclusively and uniquely to cohesin domain 6 of Sca5.

Despite these insights, the structural organization, functional interactions between the enzymes, and precise role of the amylosome in RS degradation remain largely unexplored. In this study, we therefore aimed to elucidate the molecular architecture of the amylosome, identify key enzymes involved in RS degradation, connect their structure to function, determine how its components interact, and uncover the mechanistic basis for R. bromii’s exceptional ability to degrade RS.

We leveraged cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) to visualize the architecture of the amylosome in situ, revealing it as a densely packed extracellular layer extending from R. bromii toward the RS substrate. This organization reinforces the concept of a highly structured, cell-bound degradation system. Next, quantitative proteomics demonstrated that amylosome composition shifts dynamically in response to different growth stages and carbon sources, allowing us to identify its major CAZymes. To further elucidate their function, we applied cryo-EM single-particle analysis (SPA) to resolve the structure of four key amylosome enzymes and identify structural variations in their active sites, providing insights into their substrate preferences and potential functional complementarity. Biochemical assays and interaction studies identified Amy4 and Amy16 as key RS-degrading enzymes and revealed that they exhibit strong synergistic activity in RS breakdown, a synergy critically dependent on their spatial organization. Notably, while the amylosome exhibits high combinatorial flexibility, we found that the degrees of freedom are constrained in a manner that directs Amy4 and Amy16 into close proximity, ensuring efficient RS degradation. Taken together, our findings provide a comprehensive physiological, structural, and functional understanding of amylosome-mediated RS metabolism by R. bromii, a keystone species of the gut microbiome.

Results

Amylosomes appear as dense, constitutively expressed structures at the periphery of R. bromii cells

To elucidate R. bromii’s ability to degrade RS via its amylosome system, we first characterized the spatial organization of amylosomes around R. bromii cells, using fluorescence imaging and cryo-ET. We visualized amylosome distribution around bacteria grown on either fructose, the simplest carbon source that R. bromii can utilize, as it cannot use glucose12, or RS, where R. bromii’s role as a keystone species in the human gut microbiome is manifested.

To assess the prevalence of amylosomes on a population level, we used light and fluorescence microscopy and labeled cells with a previously described GFP-dockerin probe that binds to exposed cohesin domains on the cell surface24. Fluorescence imaging confirmed that amylosomes are detected around almost all R. bromii cells, forming a rim around the cell, regardless of whether fructose or RS was supplied as the carbon source (Fig. 1a). To further resolve the molecular architecture of amylosomes, we applied cryo-focused ion beam (FIB) milling followed by cryo-ET to vitrified R. bromii cultures. Low-magnification cryo-ET revealed that bacterial cells are embedded in the outer layer of RS granules, with distances of up to 200 nm between the cell wall (CW) and the nearest RS surface (Fig. 1b, c). Higher magnifications showed direct cell-substrate contact at specific sites, with an extracellular protein layer extending from the CW (Fig. 1d). These extracellular densities were observed in 85% (111/130) of fructose-grown cells and 90% (133/148) of RS-grown cells, closely matching the proportion of amylosome-positive cells identified through fluorescent labeling. The layer structurally resembled the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome22, supporting its identification as the amylosome.

a Staining R. bromii with eGFP-Doc13a, an amylosome label (shown here in the “Fire” look-up table), reveals that almost all cells seen in brightfield (BF) imaging (gray) express amylosomes, both after growth on fructose and HiMaize resistant starch (RS, outlined with dashed line). The overlay of BF and deconvolved fluorescence microscopy is shown (left). A zoom-in image (right) clearly shows that the staining is localized to the cell surface. Here, only the fluorescence signal is shown. b, c Crops from a low-magnification tomogram of R. bromii grown on RS granules. Bacterial cells adhere to the RS substrate (outlined with dashed line) with a maximal distance of 200 nm. d At higher magnifications, direct contacts between bacterium and RS (outlined with dashed line) can be seen. The cell is surrounded by a dense protein layer, the putative amylosome (arrow). e High-magnification tomogram of the edge of R. bromii grown on RS (outlined with dashed line) shows the cells in close proximity with the substrate. The architecture of the amylosomes is visible as globular densities anchored to the cell wall through elongated linkers. f A 10-nm slice through a segmentation of the tomogram shown in panel (e), with resistant starch highlighted in gray, putative amylosome proteins in orange, cell wall and cell membrane in purple and ribosomes in green. g A model of the position of two dockerin-domain containing proteins relative to the cell wall. Doc1 and Amy4, the shortest and longest protein modeled, respectively, are shown in a half-extended and fully extended state. The residue numbers of key predicted domains are indicated. Created in BioRender. W, B. (2025) https://BioRender.com/e2uu9wq. All microscopy images are representative views from at least two biological replicates (light microscopy n = 2 per condition, cryo-ET n = 2 for Fructose, n = 7 for RS).

High-magnification tomograms revealed amylosomes as a dense protein layer attached to the CW through string-like protrusions, both in RS-grown cells (Fig. 1e) and fructose-grown cells (Fig. S1a), extending toward the substrate after growth on RS. Nevertheless, our analysis did not reveal any significant difference of amylosome structures between the two substrates. To further examine this, we focused our analysis on a subset of 21 tomograms (10 RS- and 11 fructose-grown cells), in which both cytoplasmic and extracellular structures were clearly resolved, and the cell membrane (CM) and CW were contained in cross-sections. To validate molecular preservation, we performed sub-tomogram averaging (STA) of ribosomes in the cytoplasm, achieving a resolution of 14 Å from 1135 particles (Fig. S2). To analyze the in situ architecture of the amylosome, we extracted the coordinates for all extracellular densities in the observed diameter range of 6–8 nm using the size-picking approach first described by Jin et al.28. We attempted to resolve these proteins by STA and classification (Fig. S3), but could not recover the identities of individual proteins due to a combination of two factors: Firstly, the size of amylosome proteins, particularly their rigid domains, approaches the detection limit for in situ cryo-ET around 60 kDa29. Secondly, the densities likely represent not one, but dozens of amylosome proteins.

We thus decided to study the amylosome architecture rather than its contents in our cryo-ET dataset. Initially, we combined the protein coordinates, along with segmented CW, CM, and RS and the cytoplasmic ribosomes into a single model for each tomogram (Fig. 1f, Fig. S1b, Videos S1 and S2). This model clearly shows a very dense amylosome layer adjacent to the cell wall, with most proteins at a distance of 30-50 nm from the outer edge of the cell wall (Fig. S1c). To validate whether these protein-CW distances were compatible with the known amylosome components, we predicted the structures of all dockerin-containing proteins larger than 40 kDa using AlphaFold330, and separately measured the diameter of predicted domains and the length of predicted unstructured linker regions for each protein, as well as the CW-anchored Sca2 and Sca5. With a maximally extended linker length of 3.8 Å per residue, we predict that the largest domain of dockerin-containing proteins is placed 73-160 nm from the CW in a fully extended state, and 41-88 nm in a “half-extended” state (Fig. 1g). We concluded from these analyses that the dense protein layer anchored to the CW indeed contains the amylosome.

Within the amylosome, proteins were densely packed with local protein concentrations of 0.6 ± 0.4 mM for both carbon sources (mean ± SD). Mapping the local concentration around each particle revealed that the amylosome density was generally the highest close to the CW, with some dense protein clusters directly attached to RS where substrate was present (Fig. S1d).

This analysis confirms that despite their remarkable abundance in the cell population, amylosomes retain a consistent architecture, when R. bromii cells are grown on fructose or RS. We thus hypothesized that the enzymatic composition of the amylosome would be dynamically regulated, even though the overall structure remains unchanged. This could allow dynamic fine-tuning degradative capabilities in response to changing environmental cues.

Carbon source-driven remodeling of the amylosome

To test our hypothesis that R. bromii adapts to changing carbon sources by modulating amylosome composition, and to identify key proteins that vary in their proportions and are important for R. bromii amylosome function, we conducted a proteomics analysis of bacteria grown on four carbon sources: RS, fructose, soluble starch, and pullulan, which mimics RS branching points. We incorporated a temporal dimension to the proteomic analyses by sampling cultures at three growth phases—mid-logarithmic, late-logarithmic, and stationary (Fig. S4). Given that amylosomes are structurally well-organized around the R. bromii cell wall and previous studies have identified amylosome components in both cell-associated and supernatant fractions21, we separately analyzed the cell-associated and secreted proteomes (Supplementary Data 1 and 2).

We first examined overarching trends across both cell-associated and supernatant proteomes in response to different carbon sources. The overall number of detected proteins varied significantly with the carbon source but was largely unaffected by growth phase (two-way ANOVA: carbon source, Fₐ(3, 24) = 254.8, p < 0.001, η² = 0.90; growth phase, Fb(2, 24) = 8.261, p = 0.0019, η² = 0.02). While a broad set of proteins was expressed in cultures grown on simple sugars like fructose and similarly on soluble starch, significantly smaller protein subsets were expressed in RS- and pullulan-grown cultures (Fig. 2a, p < 0.0001, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test). Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of the presence-absence proteome (Jaccard matrix) further confirmed that the carbon source has a marked influence on both the cell-associated (ANOSIM R = 0.71, p = 0.0001) and supernatant (ANOSIM R = 0.66, p = 0.0001) proteome with samples clustering according to the carbon source provided (Fig. S5a). Heatmaps of all amylosome proteins and free CAZymes involved in starch degradation, expressed in both the cell-associated proteome and the secretome, further illustrate the amylosome component versatility across carbon sources (Fig. S6).

We performed proteomics analysis of the R. bromii proteome in two fractions, the cell-associated proteome and the supernatant, after growth on four different carbon sources, at three time points. a Depending on the carbon source, significantly different numbers of proteins could be identified, shown here for supernatant and cell-associated fraction together (mean ± 95% confidence interval, two-way ANOVA, p < 0.0001, three biological replicates). Results from Dunnett’s multiple comparison test between each carbon source and fructose are shown. b PCA of the amylosome proteins in the cell-associated proteome shows carbon source-specific adaptation of the amylosome (ANOSIM R = 0.65, p = 0.0001). c Relative abundance of each class of amylosome proteins as part of all amylosome-associated proteins, across carbon sources in the cell-associated amylosome at the late stationary timepoint. The mean abundance from three biological replicates is shown. d Enrichment of amylosome CAZymes after growth on RS normalized to their abundance after growth on fructose. Three biological replicates and the results of an unpaired two-sided t test with Holm–Šídák multiple testing correction shown, line indicates mean. Exact adjusted p-values p = 0.0004 (Amy4), p = 0.0219 (Amy9), p = 0.0230 (Amy16), p = 0.4861 (Amy10), p = 0.0219 (Amy12). *: p < 0.05, ns: not significant.

Our analyses of the combined secreted and cell-associated proteomes across carbon sources also reveal a common core of 329 proteins (proteins identified in 2 out of 3 replicates for each condition). This common core proteome represents 98% of the pullulan expressed proteins, with no proteins specific to growth on pullulan. This suggests that R. bromii employs a specialization strategy to adapt protein expression to various complex carbon sources.

In our subsequent analyses, we focused on the cell-associated proteome, as the cell-associated fraction harbors substantially higher starch-degrading activity than the supernatant21. Principal component analysis (PCA) of the cell-associated protein quantities revealed distinct adaptation patterns of the amylosome proteins (Fig. 2b, ANOSIM by carbon source R = 0.65, p = 0.0001). The abundances of Amy12, Sca2 and Doc17 (a putative protease) are among the strongest contributors to the variance on principal component (PC) 1, while the abundances of Doc14, Doc16 and Doc19 (two putative proteases and one uncharacterized protein, respectively) are the strongest contributors to PC2. The expression of Amy16 is also triggered and upregulated in RS-grown cells as compared to that of other carbon sources (Fig. S6 and Supplementary Data 3). Together, these findings further support our hypothesis that amylosome composition is dynamically regulated in response to the substrate. We then focused on identifying amylosome-associated proteins that are fine-tuned based on carbon source availability.

We thus analyzed the share that each amylosome protein occupied at late stationary growth phase for each carbon source, defining putative amylosome components as proteins containing annotated dockerin or cohesin domains, or with predicted cell wall localization (Fig. 2c). This analysis reveals a strong shift in occupancy for the cell-associated amylosome, whereas the cell-free amylosome was remarkably stable in composition (Fig. S5b–d). After growth on fructose, the amylosome occupancy of the cell-associated amylosome is approximately split into thirds: one third consists of the five amylosome CAZymes Amy4, Amy9, Amy10, Amy12, and Amy16, one third of the starch-adherence systems Sas6 and Sas20, and the remainder consists mostly of dockerin-containing proteins with unknown functions, as well as annotated proteases. On soluble starch, the overall composition is similar to that of fructose; however, there is a slight increase in the share of CAZymes at the expense of the dockerin-containing proteins of unknown function. On pullulan, the cell-associated amylosome consists almost exclusively of Sas20, with about 20% Amy4 and Amy16 in the late stationary phase. The pullulanase Amy12 was only detected up to the end-log time point in the cell-associated proteome, while both Amy10 and Amy12 were detected in the supernatant at all timepoints (Figs. S6, S7), suggesting that R. bromii might rely on pullulan degradation in the medium, rather than close to the cell. On RS, there is a marked departure from the amylosome compositions on all other carbon sources: Amy4 alone accounts for over 40% of the amylosome proteins, with Amy16 accounting for another 15% (Fig. 2c). Overall, the CAZymes account for 70% of amylosome proteins. The share of starch-adherence system proteins (Sas6, Sas20, and Doc22) is slightly reduced. The strong enrichment of CAZyme activity in the amylosome likely reflects the challenge of efficiently degrading the recalcitrant RS substrate.

Notably, the CW-anchored scaffoldins Sca2 and Sca5 were not consistently detected in the cell-associated proteome, suggesting they were not efficiently removed during proteomics sample preparation, likely due to their covalent attachment to the cell wall. However, specific antibodies confirmed their presence on the cell wall using fluorescent immuno-labeling, thereby supporting their expression despite limited detection by mass spectrometry (Fig. S8).

To validate whether our observation of CAZyme enrichment in response to growth on RS was statistically significant, we compared the relative abundance of each enzyme on RS to the abundance observed after growth on fructose (Fig. 2d). Amy4, Amy9, and Amy16 were significantly enriched on RS-grown cells: Amy4 increased threefold to 45 ± 3%, Amy9 increased fivefold to 8 ± 2%, and Amy16 increased threefold to 14 ± 4%. In contrast to the observed increased abundance of the latter enzymes, Amy10 remained stable at 4 ± 0.4%, whereas Amy12 was depleted 2.5-fold to 1.8 ± 0.5% (mean ± SD, 3 biological replicates).

Together, these insights support our hypothesis of an architecturally stable amylosome, whose contents are dynamically regulated in response to environmental cues. After growth on RS, the most recalcitrant substrate tested, some CAZymes were strongly enriched in the amylosome. For example, the two most abundant amylases Amy4 and Amy16 alone accounted for 60% of the amylosome proteins. To understand why the enrichment of CAZymes was differentially modulated after growth on RS, we next aimed to understand the functional and structural differences between the five amylosome CAZymes.

Functional and structural basis for complementary activity in RS degradation

Based on our finding that the amylosome CAZymes were specifically enriched or depleted in response to changing carbon sources, we sought to investigate their differential roles in RS degradation. To this end, we assessed their activity against model substrates with glycosidic bonds similar to those found in RS, and determined the structures of Amy4, Amy10, Amy12, and Amy16 by cryo-EM SPA. Our results revealed distinct substrate specificities among the amylosome CAZymes. Notably, Amy4 and Amy16, both strongly enriched on RS, exhibited partially complementary activities.

RS granules consist mainly of two glucose polymers, amylose and amylopectin, which are packed tightly into alternating crystalline and amorphous layers31. Amylose is a mostly linear polymer, its glucose oligomers are linked via α(1,4)-glycosidic bonds, with branches occurring only once in hundreds or thousands of residues. Amylopectin, on the other hand, contains many shorter linear chains, which are branched through α(1,6)-glycosidic bonds at approximately every 20th residue. These polymers form complex secondary and tertiary structures through hydrogen-bonding, resulting in the granular appearance of RS. This chemical and structural complexity necessitates multiple enzyme activities for efficient degradation. The five amylosome-associated CAZymes in R. bromii share a conserved domain composition: an N-terminal signal peptide for secretion, followed by either a GH13-family amylase (AmyA; α(1,4)-hydrolyzing) or a pullulanase (PulA; α(1,6)-hydrolyzing) domain, along with CBM26 and dockerin domains. The PulA domains contain a CBM48 module and are present together with mucin-binding protein (MucBP) domains. The CBM mediates substrate binding32, while the dockerin domain enables enzyme-scaffoldin interactions, facilitating amylosome assembly. Additionally, Amy4 carries a cohesin domain, allowing it to recruit additional dockerin-containing proteins into the amylosome (Fig. 3a).

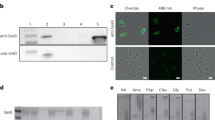

a The schematic domain organization of the amylosome CAZymes (InterPro prediction): signal peptide (SP), amylase (AmyA) or pullulanase (PulA) domain, carbohydrate-binding modules (CBM) and mucin-binding protein domains (MucBP). b Activity profiles of the purified enzymes incubated with maltoheptaose (M7), cornstarch (CS) or pullulan (Pul.), as determined by thin-layer chromatography (2 biological replicates). Amy4, Amy9 and Amy16 act on ɑ(1,4) bonds in M7, while Amy10 and Amy12 act on ɑ(1,6) bonds in Pul. Additionally, Amy16 is also active against CS and Pul. Activity of Amy4 against CS reported by Mukhopadhya et al.24 and of Amy10 against M7 reported by Cockburn et al.25 could not be replicated here but are indicated by a pink shade. c Activity of Amy16 analyzed through ion chromatography. The release of glucose (G1), maltose (G2), panose (Pan.) and maltotriose (G3) in comparison to no-enzyme controls is shown. (Unpaired two-sided t-tests with Holm-Šídák correction, 3 technical replicates). Exact adjusted p-values for release from Pul: p = 0.0183 (G1), p = 0.0004 (G2), p = 0.0360 (Pan.), p = 0.0001 (G3). Release from M7: p = 0.0020 (G1), p = 0.0006 (G2), p = 0.0004 (G3). d The fold of the catalytic domains of Amy4, Amy9, Amy16, Amy10 and Amy12, the catalytic residues are shown. The structures for Amy4, Amy10, Amy12 and Amy16 were experimentally determined, the structure for Amy9 was predicted using AlphaFold2. The models are colored by the domain annotation, following the scheme in (a), with gray representing non-annotated regions. e Detailed view at the active site of Amy4. A G3 substrate from PDB 7DCG was docked into the active site, the catalytic residues and those delimiting the active site are shown and labeled. The glucose unit to be cleaved is outlined. f The active site of Amy16 with the same substrate docked reveals a more accessible catalytic center. The bulky aromatic sidechains C-terminal of the glutamate residue are absent in Amy16. g The active site of Amy10 accommodates a maltopentaose chain on its surface, with a cleaved G3 branch below it, docked from PDB 7LSA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

To understand the role of each enzyme, we expressed and purified full-length Amy9, Amy10, Amy12, and Amy16, along with the truncated mutant Amy4Δdoc, which lacks the C-terminal dockerin domain of wild-type Amy4. This truncation was necessary to prevent aggregation of Amy4 through intramolecular cohesin-dockerin interactions during purification. We used a thin-layer chromatography (TLC) assay to determine the activity profile of each enzyme. We tested the ability of each enzyme to hydrolyze the two most common glycosidic bonds occurring in RS using model substrates: ɑ(1,4)-glycosidic bonds in maltoheptaose (M7) and the more complex cornstarch (CS), and ɑ(1,6)-glycosidic bonds in pullulan. These experiments showed that Amy4Δdoc, Amy9 and Amy16 were able to hydrolyze the ɑ(1,4)-glycosidic bonds in M7, while Amy16 was additionally active against CS and pullulan. In contrast, Amy10 and Amy12 degraded the ɑ(1,6)-glycosidic bonds in pullulan, but not the ɑ(1,4)-glycosidic bonds in M7 or CS (Figs. 3b, S9a). To further investigate Amy16’s apparent dual activity, and to assess whether it can act as a true pullulanase, i.e. hydrolyze the ɑ(1,6)-glycosidic bonds of pullulan, we analyzed its products released from pullulan and M7 by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD). Amy16 released low, but significant amounts of maltotriose from pullulan, indicating that it can indeed hydrolyzes the ɑ(1,6)-glycosidic bonds (Figs. 3c, S9b). It also released glucose, maltose, and panose from pullulan, which involves cleavage of ɑ(1,4)-glycosidic bonds, albeit at a much lower rate than when degrading M7 (Figs. 3c, S9b).

These activity data hint at a complementary relationship between the proteins enriched in response to RS, in which the dual activity of Amy16 and the specificity of Amy4 and Amy9 together ensure efficient substrate breakdown. Potentially, Amy16’s pullulanase activity could compensate for the low abundance of Amy10 and Amy12 in the proteome after growth on RS.

Next, we aimed to identify the structural features that could explain the substrate preferences of the key amylosome enzymes. The structure of the catalytic domain of Amy12 was previously determined25, revealing the active site of the protein and its mode of substrate binding. We used cryo-EM single-particle analysis to determine the structures of the catalytic domains of Amy4, Amy10, Amy12 and Amy16 at global resolutions of 2.8 Å, 3.1 Å, 3.1 Å, and 4.6 Å, respectively (Figs. S10–S13, Supplementary Data 4). Here, we compare our atomic models for Amy4, Amy10, and Amy12 to a flexibly fitted predicted model for Amy16 and a predicted model for Amy9 (Fig. 3d). All proteins share the canonical structural features of GH13-family CAZymes: an alpha/beta barrel fold and the catalytic triad consisting of two aspartic acids and a glutamate.

To investigate the structural basis for their diverging activity profiles, we focused on comparing the catalytic sites of the strictly ɑ(1,4)-hydrolyzing Amy4, the promiscuous Amy16 and the ɑ(1,6)-specific Amy10. We did not separately consider Amy12, as it showed a high structural similarity with Amy10 throughout the catalytic domain, with a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 1.1 Å across 428 Cɑ atoms and the same activity profile in our assay. A cutaway view through the active site of Amy4 reveals that the catalytic residues are embedded in a deep pocket (Fig. 3e). Docking a maltotriose substrate from the Weissella cibara GH13-family glucosidase33 (catalytic residue RMSD 0.8 Å, PDB: 7DCG) revealed a tight fit of the substrate into the catalytic site. The three glucose residues of the maltotriose occupy the full catalytic pocket, with the catalytic residues positioned to cleave off the reducing-end glucose (Fig. 3e, circle). The substrate is enclosed by protein on three sides. The C-terminal extension of the glutamate E382 acting as an acid/base catalyst contains two bulky aromatic amino acids, H383 and W384, which limit the accessibility of the active site and might be involved in coordinating the substrate.

In comparison, the active site of Amy16 is much more accessible, both towards the reducing and non-reducing end of the substrate, in line with its more promiscuous activity. The C-terminal extension of the catalytic glutamate E239 contains the aliphatic residues I240 and V241, which are less bulky and might permit more varied substrates to be recruited to the catalytic site (Fig. 3f).

In contrast to these primarily ɑ(1,4)-hydrolyzing enzymes, the catalytic residues of Amy10 are located in a shallow cleft. Docking of the cleaved maltotriose/maltopentaose substrate from Amy1225 (catalytic residue RMSD 1.0 Å, PDB: 7LSA) illustrates the fit of branched substrates into the catalytic site (Fig. 3g). Here, the branching point residue sits on the protein surface (Fig. 3g, circle). Again, the C-terminal loop of the catalytic glutamate E412 plays a key role; through a kink in P413, the bulky aromatic W414 is tilted towards the main chain of the substrate, offering a second starch binding site on the enzyme surface to increase Amy10’s affinity for branched substrates, which was previously described in Amy1225.

In conclusion, analysis of the experimental structures of the amylosome CAZymes Amy4, Amy10, Amy12, and Amy16 serves to explain the basis for the divergent substrate preferences between the ɑ(1,4)-specific Amy4, the ɑ(1,4)-preferring Amy16 and the ɑ(1,6)-specific Amy10 and Amy12. Strikingly, although Amy9 shares the highest sequence similarity with Amy1624, it lacks the residual α(1,6)-hydrolyzing activity toward resistant starch observed for Amy16, leaving its function within the amylosome unresolved. A central finding is the complementary activity profiles of the highly enriched enzymes Amy4 and Amy16. Based on our functional and structural characterization of the amylosome enzymes, we hypothesize that this complementarity may play an important role for RS degradation.

Amylosome CAZymes exhibit synergistic effects in RS degradation

To further elucidate the roles of the amylosome CAZymes in RS degradation and to test our hypothesis of their complementary functions, we examined their activity against HiMaize RS.

We therefore incubated the enzymes with raw HiMaize 958 RS, and monitored product formation after 3 h qualitatively and quantitatively using TLC and HPAEC-PAD. In addition, we quantified the total release of reducing sugars using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Fig. 4a). HPAEC-PAD analysis indicated that Amy4Δdoc and Amy16 released glucose, maltose and maltotriose from RS, while Amy9 released primarily maltose and maltotriose, all at levels below the sensitivity of the TLC assay (Fig. S9c). Product release was highest by Amy16, followed by Amy4Δdoc and Amy9. The differences in total activity were supported by total reducing sugar quantification, which indicated that Amy16 released 1.1 ± 0.2 mM reducing sugars, while Amy4Δdoc released 0.4 ± 0.2 mM reducing sugars. The production of reducing sugars by Amy9 was not significant above background levels (1 µM enzyme, mean ± SD, 4 biological replicates, Fig. 4b). To reconcile these biochemical findings with our previous proteomics results, in which Amy9 was 5-fold enriched in the amylosome on RS compared to fructose (Fig. 2d), we investigated whether enzymatic activities against the autoclaved RS used for culturing R. bromii differed from those against untreated RS. Indeed, Amy4Δdoc, Amy9, and Amy16 were significantly more active against autoclaved HiMaize RS (Fig. S14a). Autoclaving Hi-Maize 958 alters its structure, reducing its native crystalline content (type 2 RS) and converting it to a retrograded crystallinity (predominantly type 3 RS) form. As R. bromii’s role as a keystone species is strongest on RS212, we continued our biochemical characterization with raw RS.

a An assay to test the RS-degradation capability of the amylosome CAZymes: the purified enzymes were incubated with resistant starch either individually or in combinations for 3 h at 37 °C. After the reaction time, product formation was assessed qualitatively by TLC and ion chromatography and quantitatively using a BCA assay. Created in BioRender. W, B. (2025). https://BioRender.com/c49f659. b The release of reducing sugars quantified by the BCA assay. Only Amy4Δdoc (p = 0.0005) and Amy16 (p < 0.0001) show significant reducing sugar production (four biological replicates, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test). c If all enzymes are incubated together, more substrate is produced than expected by the sum of activities (four biological replicates, two-sided paired t test, p = 0.0098). d The synergistic interactions were quantified as the ratio of observed over expected product formation. In a leave-one-out series, no significant synergism was detected without Amy4Δdoc (four biological replicates, two-sided paired t tests). Exact p-values: p = 0.7447 (no Amy4Δdoc), p = 0.0173 (no Amy9), p = 0.0160 (no Amy16), p = 0.0046 (no Amy10), p = 0.0046 (no Amy12). e Pairwise synergism with Amy4Δdoc is only observed for Amy16, all other combinations not significant (two-sided unpaired t test, Amy10 and Amy12: three technical replicates, Amy16: five technical replicates from two biological replicates, Amy9: 2 technical replicates after outlier removal). Exact p-values: p = 0.3194 (Amy9) p = 0.0023 (Amy16), p = 0.3239 (Amy10), p = 0.5599 (Amy12). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns: not significant.

Next, we were interested in reconstituting a situation resembling the amylosome, in which different enzymes act at the same time. We thus incubated the five purified CAZymes together with RS. This mixture released 2.4 ± 0.2 mM reducing sugars, significantly exceeding the sum of individual enzyme activities by over 40% (Fig. 4c, expected activity 1.7 ± 0.2 mM, paired t-test), indicating a strong synergistic interaction between the enzymes.

To further investigate this effect, we quantified the individual contribution of each enzyme to the observed synergistic interaction. To this end, we measured the activity of enzyme combinations in which one CAZyme was omitted from the reaction mixture. Plotting the synergy strength, i.e., the ratio of observed over expected product formation, for this leave-one-out series, indicates that Amy4Δdoc is the key component driving synergism, as its absence resulted in the loss of significant synergistic interactions. In contrast, the other enzymes were not essential for synergism to occur (Fig. 4d). When we tested whether synergistic effects could be captured in a minimal two-enzyme system by combining Amy4Δdoc with each of the other enzymes in the presence of RS, we found that Amy4Δdoc exhibited pairwise synergism exclusively with Amy16, but not with any other CAZymes (Fig. 4e). We used this system to confirm that our previous assays were capturing a state of substrate abundance. Indeed, even after 180 min, product release had not plateaued, and the synergistic interaction between Amy4 and Amy16 was constant over time (Fig. S14b).

This finding corroborates our prediction of Amy4 and Amy16’s key role in RS degradation, and is in line with our proteomics and structural analysis. It extends our previous findings by demonstrating a direct synergistic interaction between these two strongly enriched enzymes.

Coordination through Amy4’s cohesin domain is required for synergistic RS degradation

Based on Amy4’s unique domain architecture, which allows it to serve as a scaffoldin (Fig. 3a), and its key role in synergistic RS degradation (Fig. 4d), we hypothesized that the direct interaction of CAZymes in an amylosome-like complex is important for their pronounced synergistic activity. To test the importance of the scaffoldin function of Amy4, we compared the binding behavior and synergistic RS degradation of two truncated Amy4 mutants: Amy4Δdoc, lacking the dockerin domain, and Amy4Δcoh, lacking the cohesin domain. Both mutants were equally active against RS, as confirmed by TLC and reducing sugar quantification (Fig. S15).

Our results show that Amy4 can recruit Amy16 through its cohesin domain, and that formation of this complex is essential for their synergistic interaction. Amy4Δdoc formed a stable complex with Amy16 during size exclusion chromatography (SEC) (Fig. 5a, top) which enabled significant synergistic interaction between all CAZymes, and solely with Amy16 (Fig. 5a, bottom). In contrast, Amy4Δcoh failed to bind to Amy16 (Fig. 5b, top) and did not facilitate significant synergistic interactions (Fig. 5b, bottom). Taking together the binding and activity data, these findings indicate that Amy4 functions as a scaffoldin for Amy16, ensuring physical proximity, which significantly enhances their ability to degrade RS through their synergistic interaction (Fig. 5c).

a Top: Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) profile showing tryptophan (Trp) fluorescence in absorbance units (AU) during elution of Amy4Δdoc, Amy16 (dashed), or their combination (continuous line). Amy4Δdoc elutes together with Amy16 in a single peak, which contains both proteins, as seen on the SDS-PAGE gel on the right. Below, the synergistic interaction between Amy4Δdoc either with all other amylosome CAZymes (p = 0.0230) or with Amy16 alone (p = 0.0011) is shown, with results of unpaired two-tailed t-test (three technical replicates). b SEC profile showing the Trp fluorescence during elution of Amy4Δcoh, Amy16 (dashed), or their combination (continuous line). The combination elutes in two separate peaks. Below, the observed over expected product formation of Amy4Δcoh incubated either with all other amylosome CAZymes (p = 0.8058) or with Amy16 alone (p = 0.0853), indicates no significant synergistic effect. Results of unpaired two-tailed t-test are shown (three technical replicates). c A model linking complex formation and synergistic activity. Amy4Δdoc, which lacks the cohesin and thus does not interact with other dockerin-containing enzymes, exhibits synergism. Amy4Δcoh, which does not interact, does not induce synergism. Created in BioRender. W, B. (2025). https://BioRender.com/4nx8bk0. d Interaction data for the dockerin domains in the amylosome CAZymes with the cohesin domains in Amy4 or the cell-bound scaffoldins Sca2 and Sca5. Data from Mukhopadya et al.24 and Ze et al.21, scored on the five-point scale used by Ze et al.21. Amy16 does not bind to either cell-bound scaffoldin (Sca2 or Sca5), but binds strongly to Amy4. e Model highlighting the recruitment of Amy16 to cell-bound Amy4, based on interaction data. All Amy16 in cell-bound amylosomes must be found in complex with Amy4, as there is no alternative mechanism for its recruitment to the cell. Only catalytic, cohesin and dockerin domains are shown in this schematic, for full model see Fig. S17. Created in BioRender. W, B. (2025). https://BioRender.com/y31q9fi. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ns: not significant.

As we could not resolve individual protein identities in our cryo-ET dataset and thus directly visualize whether the synergistic Amy4-Amy16 complex is formed in situ using STA, we instead studied binding flexibility in the amylosome to assess whether this complex can be formed in a physiological setting. We thus investigated the potential cohesin-dockerin-complexes formed within the amylosome. Specifically, we examined how the two cell-bound scaffoldins interact with the five amylosome CAZymes, in order to better understand amylosome structure and function in RS degradation. For this purpose, we complemented cohesin-dockerin binding affinities within the amylosome from two previous studies21,24 with newly measured ELISA interaction data for dockerin-containing enzymes detected in our proteomic analyses (Fig. S16, Supplementary Data 5). Together, these results reveal that Amy16 can only be recruited to the cell-bound amylosome through Amy4, as Amy16 is the only amylosome CAZyme that lacks the ability to directly bind to the cell-bound scaffoldins Sca2 or Sca5 (Fig. 5d).

This suggests that compositional flexibility within the amylosome is constrained specifically for Amy16. Since Amy16 does not directly bind Sca2 or Sca5 but is highly abundant in the cell-associated proteome, we propose a model in which Amy4 acts as a cell-surface adapter for Amy16 (Fig. 5e). In this model, constrained binding flexibility ensures their spatial proximity and unlocks their synergistic effects in RS degradation. While this complex could not be directly visualized in situ, our proteomics data and combinatorial studies strongly suggest its existence.

Integrative model of the amylosome highlights flexibility and efficiency

The fact that the amylosome architecture is maintained, while its contents are adapting to environmental changes, is a direct consequence of the modular architecture of the amylosome. The covalently cell-wall anchored scaffoldins Sca2 and Sca5 remain in place, while their dockerin-containing binding partners are flexibly exchanged. This is only possible due to the promiscuity of the cohesin-dockerin interactions within the amylosome (Fig. S16, Supplementary Data 5). Combining the cohesin-dockerin binding affinities with the abundance information derived from quantitative proteomics allows us to construct a model of the amylosome after growth on RS (Fig. 6, equivalent models for other carbon sources in Fig. S17). Four proteins, Amy4, Amy16, Doc22 and Sas20 each occupy more than 10% of the amylosome. Two of these, Amy16 and Sas20, exclusively interact with one cohesin domain: Amy16 with the Coh1 of Amy4, Sas20 with the Coh6 of Sca5. This reveals a mechanism for regulating amylosome function beyond abundances. The high enrichment of these dockerin-containing proteins and their high affinity for a specific binding cohesin enforce complex formation; these two factors together unlock the synergistic effects required to access complex carbon sources such as RS.

The schematic shows the amylosome compositions expressed on resistant starch by R. bromii L2–63. The predicted carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs) and catalytic domains of each expressed component are shown. The arrows indicate possible cohesin-dockerin interactions and are colored by the respective cohesin domain. Exclusive interactions are represented by continuous lines, possible interactions by dashed lines. Only proteins detected at >1% of the amylosome content in two replicates are represented, and protein names constituting at least 10% of the amylosome content are highlighted. The schemes depict data from the late stationary phase. The sortase motifs responsible for covalently anchoring Sca2 and Sca5 to the cell wall are not represented. Created in BioRender. M, S. (2025). https://BioRender.com/ltrly9a.

Discussion

In this study, we present a comprehensive physiological, structural, and functional understanding of amylosome-mediated RS metabolism by R. bromii, a keystone species of the gut microbiome. We first leveraged cryo-ET to visualize the amylosome in situ as a dense layer of proteins anchored to the CW. We focused on studying the overall architecture of the amylosome on different carbon sources and could not observe any carbon-source specific modulation at this level.

We then generated a quantitative proteomics dataset with spatial and temporal resolution, highlighting the adaptability of the amylosome at the protein level. Through biochemical assays, we identified Amy4 and Amy16 as synergistic partners for RS degradation and identified their assembly in an amylosome-like fashion as a key to their synergism. Using combinatorics, we identified that Amy4 serves as an amylosome adapter to Amy16 in situ, thereby enforcing their assembly and suggesting synergism in the amylosome.

Even though our comprehensive proteomics dataset uncovered precise and complex patterns of nutrient adaptation, the underlying regulatory mechanisms remain unknown. Indeed, unlike other starch-degrading bacteria in the gut microbiome, R. bromii’s CAZymes are not organized in polysaccharide utilization loci (PULs), but are instead dispersed throughout the genome24, suggesting that distinct regulon systems, potentially mediated by specific promoters and regulatory elements, control their expression. In Gram-negative bacteria, PULs typically depend on two-component systems (TCSs) to sense environmental carbohydrates, but Gram-positive organisms appear to employ different signaling strategies. For example, in Clostridium thermocellum, membrane-associated anti-sigma (anti-σ) factors regulate alternative sigma-I (σI) factors in response to extracellular polysaccharides34,35,36. However, our search for PF23750 domain-containing proteins (anti-σ factor RsgI-like domains) in the R. bromii genome did not identify clear homologs, suggesting that R. bromii may rely on a regulatory system yet to be characterized. Supporting this notion, our analysis of publicly available transcriptomic datasets16 comparing R. bromii growth on soluble versus resistant starch revealed a distinct clustering of expression profiles on these two substrates, with 26 genes significantly upregulated on soluble starch (Fig. S18, Supplementary Data 6). Many of these genes encode enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism, including those linked to sugar transport and central metabolic processing. Notably, however, no amylosome components were differentially transcribed between soluble and resistant starches, implying that the observed adaptation of the proteome is driven by a coordinated but as-yet unidentified regulatory network that enables R. bromii to discriminate between these substrates which are chemically equivalent but physically different.

Importantly, while the amylosome remains structurally stable, our findings reveal that its composition, combinatorics, and function are highly variable and responsive to different carbon sources. Within the amylosome, turnover could be facilitated by breaking down unnecessary amylase components, allowing newly synthesized proteins to be incorporated. Potentially, the dockerin-containing protease Doc17 could play this role, as it strongly contributes to the differentiation of the “generalist” amylosomes after growth on fructose or starch, but not in those adapted for pullulan or RS in a PCA. Notably, we also report relatively high consistency in the composition of cell-free amylosomes, compared to the greater variability of cell-associated complexes. One possible explanation is that newly synthesized enzymes are incorporated directly into the cell-associated amylosomes upon secretion, allowing for a flexible and adaptive assembly in response to environmental cues. In contrast, the cell-free amylosomes likely consist of proteins that have been shed or released from the cell surface and are no longer subject to active cellular regulation. As such, their composition may reflect a more stable, averaged snapshot of prior cellular states, contributing to the observed consistency.

On a structural level, our characterization of Amy4, Amy10, Amy12, and Amy16 provides the molecular basis for their distinct substrate specificities. A direct comparison of these four structures indicates a key role for the residues directly succeeding the catalytic glutamate: For the debranching enzymes Amy10 and Amy12, a tryptophan residue provides a starch-binding site for the main polysaccharide chain on the cell surface, while in Amy4, the site envelops the linear substrate. The bifunctional Amy16 carries two aliphatic instead of aromatic residues, which could support its more promiscuous activity profile; a similar arrangement was previously reported for another member of the GH13_28 subfamily originating from Bacillus subtilis37. This study contributes to a growing body of structural research on GH13-family CAZymes, which share a conserved fold yet exhibit diverse substrate preferences and are abundant in the human gut microbiome38.

Biochemical assays and interaction studies identified Amy4 and Amy16 as the principal RS-degrading enzymes, exhibiting strong synergistic activity critically dependent on their spatial organization. The biochemical basis for this synergism between structurally similar enzymes when they are assembled into an amylosome remains elusive. Potentially, the complementarity between the partially ɑ(1,6)-active Amy16 and the ɑ(1,4)-specific Amy4 could permit simultaneous activity on the same polysaccharide chain, or the increased number of CBM domains in the complex improves substrate-binding through avidity effects, as has been observed for other starch-degrading enzymes with multiple CBMs39.

While the amylosome displays high combinatorial flexibility, we show that combinatorial constraints enforce the close proximity of Amy4 and Amy16 in the cell-associated amylosome, ensuring efficient RS breakdown. For example, in response to growth on RS, the enrichment of Amy4, which interacts with a wide array of amylosome components and is otherwise subject to competition within the complex, increases its availability across the amylosome. This reduces competition for its cohesin domain and favors its interaction with Amy16, which also represents a large proportion of the amylosome components. This co-enrichment enhances the likelihood of Amy16 docking onto Amy4’s cohesin domain, prioritizing their interaction over other CAZymes that would otherwise compete for the same binding site. This selective recruitment maximizes their synergistic RS degradation in both cell-bound and cell-free fractions. Such proportional modulation likely enables distinct combinatorial assemblies that optimize enzymatic function based on substrate availability across different conditions.

Taken together, this work provides key insights into amylosome organization, enzyme interactions, and RS degradation, highlighting the molecular basis for R. bromii’s role as a keystone species in the gut microbiome. Additionally, our study delivers valuable physiological, biochemical, and structural resources to the scientific community, offering a foundation for future research into R. bromii function and its ecological significance. The synergy and combinatorics-driven mechanism for efficient RS degradation identified in this study may help in the future design of better pre- and probiotics, which might restore RS-degrading ability to all microbiomes, counteracting the dysbiosis frequently induced by an industrialized diet.

Methods

The research reported in this study conforms with all relevant ethical regulations. As no animals or human patients were used in this study, no institutional approval was required.

Bacterial culture

Ruminococcus bromii L2-63 was grown in Hungate tubes in 8 mL of autoclaved M2 anaerobic media40, supplemented with 0.2% of either fructose, pullulan (Merck), starch (from potato, Merck) or resistant starch Hi-Maize 958 (Ingredion, kindly provided by Prof. Harry Flint, University of Aberdeen) and incubated at 37 °C. It is of note that autoclaving Hi-Maize 958 alters its structure, reducing its native RS2 content and converting it to a mixed RS2/RS3 or predominantly RS3 form. Growth curves were measured on each carbon source to determine mid-logarithmic, end-logarithmic and late-stationary phases (Fig. S4). Optical densities were measured for growth on fructose, pullulan, and starch while quantitative PCR was used to determine 16S rRNA copy numbers per µL in resistant starch cultures using 16S RNA universal primers covering the V2 and V3 regions of the gene (5′-TTTGATCNTGGCTCAG-3′ and 5′-GTNTTACNGCGGCKGCTG-3′) as described previously41.

Proteomics sample preparation

Cultures were grown as biological triplicates (n = 3) on all four carbon sources, using the same batch of rumen fluid to minimize variability, and harvested at three time points (mid-logarithmic, end-logarithmic and late-stationary phases) by centrifugation at 5000 g for 10 min. The pellets were treated using the shaving approach, which includes limited proteolysis by trypsin treatment followed by removal of the cell pellet to enrich cell surface proteins42. Supernatant samples were frozen, stored at −80 °C and sent to the University of Greifswald for further preparation. For each biological replicate, a volume of 1 mL of the supernatant fluids was used for protein enrichment with 20 µg StrataCleanTM beads as previously described43. The dried StrataCleanTM beads were resuspended in 30 µL 2x reducing Laemmli sample loading buffer, incubated for 10 min at 98 °C, and loaded on an SDS gel. Proteins were separated via SDS-PAGE, each SDS gel line was cut into five equal fractions, and each fraction was in-gel digested as previously described44 and desalted using U-C18 Zip Tips (Merck Millipore), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

LC-MS/MS measurement and data analysis

Tryptic peptides were separated on a liquid chromatography system (EASY nLC, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with an in-house built 20-cm column (inner diameter 100 µm, outer diameter 360 µm) filled with ReproSil-Pur 120 C18-AQ reversed-phase material (3 µm particles, Dr. Maisch GmbH, Ammerbuch, Germany). The peptides were loaded with solvent A (water MS grade in 0.1% acetic acid (v/v)) and afterwards eluted within a non-linear 100 min gradient, ranging from 5% to 99% solvent B (99.9% acetonitrile (v/v), 0.1% acetic acid (v/v)) at the constant flow rate of 300 nL/min. Eluting peptides were injected into an LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in data-dependent acquisition mode. Full scans were recorded (full scan resolution 30,000; mass range 300 to 2000 m/z; 1 × 106 automatic gain control target in the Orbitrap), and the five most abundant (TopN = 5) precursor ions were selected for fragmentation. Singly charged ions, as well as ions without detected charge states, were not selected for MS/MS analysis. Collision-induced dissociation fragmentation was performed with a normalized collision energy of 35, and the fragment ions were recorded in the linear ion trap.

MS *.raw data were searched with MaxQuant45,46 (version 2.0.3.0) and its implemented search engine Andromeda47 against a protein database obtained from GenBank assembly GCA_900291485.1 (2,111 proteins). Common laboratory contaminants and reverse entries were added by MaxQuant. MaxQuant was used with the following parameters were used: digestion mode, trypsin/P with up to two missed cleavages; variable modification methionine oxidation, protein N-termini acetylation, and a maximal number of 5 modifications per peptide; activated label-free quantification (LFQ) option with minimal ratio count of two and “match-between-runs” feature for biological replicates and classical normalization for cell-surface proteome. Proteins were identified with at least two unique peptides; peptide-spectrum match and protein false discovery rate were set to 0.01.

For data analysis the software Perseus48 (version 2.0.3.0) was used. The data from MaxQuant output files were filtered for contaminations, reverse entries and only identified by site hits. Since classical normalization for the secretome dataset failed, the “LFQ intensities” were Z-score normalized. A protein was only quantified with “LFQ intensities” if it was present in at least two of three replicates. The quantified abundances for all replicates for cell-associated and supernatant proteome are listed in Supplementary Data 1 and 2, respectively.

All entries in the strain-specific database were additionally annotated for CAZymes using the dbCAN3 web server49 (results filtered to domains found by at least 2 tools) and the cellular localization was annotated using the pSortB 3.0 web server50.

To estimate the relative abundance of an amylosome protein, we divided the LFQ abundance of the protein by the sum of LFQ abundances of all amylosome-associated proteins in a given sample. We considered proteins as putative amylosome components if they had an annotated dockerin or cohesin domain or had a predicted cell wall localization.

For PCA, missing values were imputed based on the probabilistic minimum method. For differential expression analysis between resistant starch and other carbon sources, we used the DEP R package51, which internally employs limma for statistical testing, including variance-stabilizing transformation (VST) normalization and false discovery rate (FDR) correction.

Transcriptomics analyses

Reads from the meta-transcriptomics of R. bromii L2-63 grown on starch and resistant starch were retrieved from ArrayExpress database at EMBL-EBI (www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) under accession number E-MTAB-713816. Reads were analyzed using Deseq2 for differential expression analysis52 with batch correction performed using ComBat from the sva R package53.

Cloning and constructs

Primers for the design of Amy4, Amy9, Amy10, Amy12, Amy16 and dockerin-containing constructs in pET28a were synthesized (Supplementary Data 7) and used with R. bromii L2-63 genomic DNA as a template for the PCR. Plasmid sequences were validated by Sanger sequencing. Plasmid GFP-Doc13a was previously described24. Residue numbering used throughout this paper is in reference to NCBI GenBank sequences, as indicated in Supplementary Data 5.

To prepare the Amy4Δdoc and Amy4Δcoh mutants, the wild-type plasmid was linearized by PCR with primers omitting the deletion and an overhang on the forward primer (sequences in Supplementary Data 7, ordered from Microsynth). The dockerin deletion removes Leu-1294–C-terminus, the cohesin deletion removes Ser-1138–Asp-1265. The template was removed from the reaction mix by DpnI digest for 3 h at 37 °C. E. coli DH5a cells were transformed with the linearized vector and allowed to recover for 3 h before plating. The next day, several clones were selected for sequencing to obtain the desired plasmid.

Protein expression and purification

Purifications of enzymes and dockerin-containing proteins were performed as follows: E. coli BL21* cells were transformed with the desired plasmid and plated. A single clone was extracted and used to inoculate 3 ×0.5 L pre-warmed Luria-Bertani (LB) medium, incubated at 37 °C with shaking (120 rpm). At OD ~ 1, 0.25 L cold LB medium and isopropyl ß-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1 mM were added, and the flask was transferred to a pre-cooled incubator for overnight expression at 16 °C with shaking (90 rpm). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. Pellets were washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 12 mM phosphate, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl) and harvested again for 15 min at 5000 × g, 4 °C. After removing the supernatant fluids, pellets were flash-frozen and stored at −80 °C until purification. GFP-Doc13a was expressed as follows: Transformed E. coli BL21 DE3 cells were grown in 3 ×0.5 L LB supplemented with 2 mM CaCl2. At OD ~ 1, they were induced with 3 mM IPTG and transferred to a pre-cooled incubator for overnight expression at 18 °C, with shaking (110 rpm). Cells were harvested by centrifugation for 15 min at 6000 × g, 4 °C. Pellets were washed with cold PBS and harvested again by centrifugation for 15 min at 6000 × g, 4 °C. For purification, pellets were thawed on ice and incubated with lysis buffer (25 mM Tris, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 5 mM imidazole, 2 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF), cOmplete protease inhibitors (Roche), pH 7.4 + 10 mM CaCl2 for enzymes). Cells were additionally lysed by sonication, and debris removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g, 1 h, 4 °C. The supernatant fluids were syringe-filtered to 0.45 µm and loaded on a HisTrap FF column (Cytiva). After a wash of 10-15 column volumes (CV) with 20 mM imidazole, the proteins were eluted using a gradient up to 500 mM imidazole while collecting 1 mL fractions. The fractions containing the proteins were dialyzed into Tris-buffered saline (TBS) + 10 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4 and concentrated using a spin concentrator (enzymes) or directly concentrated without dialysis (GFP-Doc13a), before injecting 500 µL on a Superdex 200 increase 10/300 GL increase size exclusion column (Cytiva), run at 0.3 mL/min for 1.5 CV with SEC buffer (TBS + 10 mM CaCl2 + 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), pH 7.4). Fractions containing the proteins of interest were pooled and concentrated using spin concentrators.

While Amy9, Amy10, Amy12, and Amy16 were eluted as a monodispersed peak during SEC, Amy4 showed significant signs of aggregation. We presumed that this was caused by homo-oligomer formation through intermolecular cohesin-dockerin interactions. We therefore cloned and purified AmyΔdoc, a mutant without the C-terminal dockerin domain, which did not show signs of aggregation. The activity profile of this mutant matched the wild-type enzyme, and it was thus used for further characterization. Enzymes were used directly after SEC purification or flash-frozen and stored at −80 °C. GFP-Doc13a was diluted to a final concentration of 0.25 mg/mL in 1:1 glycerol:SEC buffer, flash-frozen and stored at −20 °C.

GFP-Doc13a staining and light microscopy

To visualize the cohesins exposed on the cell surface, cells were allowed to interact with GFP-Doc13a. Bacteria were cultured on the appropriate carbon source as described above. A 1-mL volume of culture was collected, and the cells were harvested at 5000 × g for 5 min. Cells were resuspended in 200 µL PBS and washed 3 times (pellet 3 min at 5000 × g, resuspended). The final resuspension was done in 160 µL PBS + 10 mM CaCl2 + 40 µL (10 µg) GFP-Doc13a + 1:1000 SPY650-DNA (Spirochrome). Cells were incubated for 1 h at room temperature on a rotating platform. After cohesin-dockerin binding, the cells were again washed 3 times. A volume of 10 µL of the cell suspensions was added to a glass slide and air-dried in the dark for 1 h before adding DAKO mounting medium (Agilent) and closing with a cover slip, sealed with nail polish.

Samples were imaged on an Olympus IX83 widefield microscope using a 100x NA 1.4 oil objective with a z-step of 280 nm, using brightfield, Cy5 and Alexa488 filter sets. Image stacks were bleach-corrected and converted to tiff format using vsi2tif (https://github.com/bwmr/vsi2tif) before deconvolution in SVI Huygens (Scientific Volume Imaging, Hilversum, Netherlands).

Confocal microscopy of cell-associated scaffoldins

To validate the presence of the cell-associated scaffoldins Sca2 and Sca5 on the cell surface, cells grown on fructose were immuno-labeled. Cֹells (2 ml) were centrifuged (5 min, 5000 × g), washed in TBS, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 min. After three washes in TBS, cells were blocked in 5% BSA in TBS for 1 h at room temperature. Blocking solution was removed by centrifugation and specific chicken antibodies (Aluma-Bio, Israel) against full-length Sca2 (at 1:1000 dilution) or the first cohesin of Sca5 (at 1:250 dilution) were added. Following 1 h incubation at room temperature, the cells were washed another three times with TBS, and Alexa Fluor® 647 goat anti-Chicken IgG (ThermoFisher Scientific, AB-2535866) was used as secondary antibody at 1:500 dilution. After 1 h incubation at room temperature and three washes of the cells using TBS, the cells were mounted on slides with SlowFade Gold anti-fade reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using polylysine-coated cover slides. Finally, the cells were imaged using a 3i Marianas spinning disk confocal microscope equipped with a Yokogawa W1 module and Prime 95B sCMOS camera. Excitation laser (absorbance 637 nm and emission filter 672–712 nm) was achieved using a Å~100 Zeiss Plan-Apochromat 1.4 NA DIC oil objective.

Affinity-based ELISA analysis of dockerin cohesin binding

The previously published protocol was followed54. Briefly, high-binding microplates (Greiner Bio-One) were coated overnight at 4 °C with 100 µl/well of dockerin constructs (Doc2, Doc4, Sas6, Doc19 and Doc26) at 1 μg/ml in 0.1 M sodium carbonate (pH9). Plates were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 100 µl/well TBS containing 10 mM CaCl₂, 0.05% Tween 20, and 2% BSA. After blocking, serial dilutions of Coh constructs (Coh1 to Coh6) in blocking buffer were added for 1 h at room temperature (100 µl/well). Plates were washed three times with blocking buffer without BSA, incubated 1 h at room temperature with 100 µl/well of rabbit anti-CBM antibody54 (diluted 1:10 000), washed again, and incubated 1 h with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Merck, A0545, diluted at 1:10,000). Following four washes, TMB substrate was added, the reaction was stopped with 1 M H₂SO₄ (50 µl/well) and absorbances at 450 nm were measured.

Cryo-EM sample preparation

Purified proteins were concentrated to 0.3 mg/mL (Amy4Δdoc), 0.08 mg/mL (Amy10/Amy12) or 0.1 mg/mL (Amy16). Au 200-mesh R1.2/1.3 holy carbon grids (Quantifoil) were plasma-cleaned for 35 s on “High” and 10 s on “Low” (Harrick Plasma PDC-32G). Plunge-freezing was conducted on a Vitrobot Mk. IV (FEI), the camber set to 4 °C and 100% humidity. 3 µL of protein solution were applied to each grid, which was then blotted 3.5 − 7.5 s (blot force −1), before being vitrified using liquid ethane. Grids were stored in liquid nitrogen until imaging.

Cryo-EM SPA data acquisition and analysis

Samples on grids were clipped into AutoGrids and loaded into Titan Krios G3i cryo-TEM (ThermoFisher Scientific) operated at 300 kV equipped with an energy filter (zero-loss mode, 20 eV width) and K3 direct electron detector (Gatan). Data acquisition was controlled using EPU, full acquisition parameters for each dataset can be found in Supplementary Data 4.

Cryo-EM SPA processing was performed using cryoSPARC (Structura Biotechnology). Briefly, movies were preprocessed with patch-based motion correction and CTF estimation, before particle picking, 2D classification and refinement against ab-initio generated templates. The processing pipelines for each structure are listed in Figs S10–S13. For Amy10, the 3DFlex workflow55 was used to retrieve additional density belonging to the accessory domains.

Model building

The models for Amy4, Amy10, and Amy16 were built based on the AlphaFold2 predicted models56. Predicted models were docked into the densities using ChimeraX57, preprocessed using Phenix58. The models were then adapted in an iterative workflow with building in ISOLDE59 and real-space refinement in Phenix. The model for Amy12 was built based on the previously published x-ray structure (PDB: 7LSA), which was docked using ChimeraX and subjected to real-space-refinement in Phenix. Complete refinement and validation statistics can be found in Supplementary Data 4.

Enzyme activity assays

Enzymes were incubated at 1 µM final concentration in SEC buffer (as described above) with 5 mM maltoheptaose (Cayman Chem), 0.6% (w/v) pullulan (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.3% (w/v) cornstarch (Maizena), or 0.3% HiMaize 958 resistant starch (Ingredion) at 37 °C for 1 h (M7, pullulan, CS) or 3 h while shaking at 300 rpm (RS). For each digestion, a substrate-only control was included. Reaction mixtures were stored at −20 °C until further use.

Thin-layer chromatography

Product formation was observed using TLC on 10 × 20 cm silica plates (Macherey-Nagel), following a previously published protocol60: On each plate, 1 µL of 10 mM glucose solution was spotted as a control. For digestions of M7, pullulan or CS, 2 × 1 µL of reaction mix were spotted, for RS degradation 3 × 1 µL. The TLC was then run in a pre-equilibrated chamber with an 85:20:50:50 acetonitrile:ethyl acetate:isopropanol:ddH2O eluent until the solvent front reached 3 cm below the top of the plate. After the solvent had evaporated, the plate was stained by spraying with 0.8% (w/v) N-(1-naphtly)ethylenediamine (Sigma-Aldrich) in 5% (v/v) sulfuric acid in methanol. After allowing the staining solution to dry, the plate was heated in an oven to 120 °C for 10 min, until spots could be seen, and imaged.

HPAEC-PAD

For analysis of product formation from RS digestion, enzymatic digests were sequentially ion-exchanged to remove background signal from Tris buffer following a previously published protocol61: After lyophilization, samples were reconstituted in ddH2O water. Enzymatic digests of pullulan and maltoheptaose by Amy16 were performed as described above using a HEPES-based buffer (25 mM HEPES, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4). In both cases, samples were diluted 1:15 in ddH2O, and boiled for 10 min at 95 °C and cleared from denatured protein by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min.

Carbohydrates present in the sample were analyzed on a Dionex ICS-6000 DC system equipped with a guard and an analytical CarboPac PA200 column (ThermoFisher Scientific). Carbohydrates were separated at 30 °C and 0.4 ml min−1 flow using the following gradient: 7 min at 100 mM NaOH, then a linear gradient to 190 mM NaOAc in 100 mM NaOH in 33 min, followed by a washout step at 425 mM NaOAc in 100 mM NaOH for 6 min, and column re-equilibration in 100 mM NaOH for 15 min. Eluted components were detected electrochemically using a non-disposable triple-A gold electrode in combination with an Ag/AgCl-pH reference electrode (ThermoFisher Scientific).

To calibrate retention times and product concentrations, a standard panel of ɑ(1,4)-linked malto-oligosaccharides containing one to seven glucose subunits, as well as the ɑ(1,6)-ɑ(1,4)-linked panose, was run in duplicate (each component was present at concentrations from 0.325 µM to 48 µM). Carbohydrates in the samples were quantified based on the linear fit of the area under the signal curve of each standard component over its linear detection range. A water sample and a low-concentration standard were run after every 8-10 samples to account for shifting retention times over the course of the analysis.

BCA assay

Reducing sugars were quantified using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay62. Briefly, 2 µL of reaction mixture or glucose standards were diluted in 60 µL ddH2O. The samples were incubated with 60 µL BCA solution (27.14 g/L Na2CO3, 12.1 g/L NaHCO3, and 0.97 g/L disodium 2,2′-bicinchoninic acid, 0.625 g/L CuSO4:5H2O, 0.63 g/L L-serine in ddH2O) at 80 °C for 20 min. Then, 100 µL of each sample were transferred to a 96-well plate, in which absorption was measured at 562 nm in a plate reader (Tecan).

Absorption values were corrected for background using a BCA + ddH2O control. Then, per-plate linear fit was calculated using the glucose standards, and unknown values interpolated. Concentrations of reducing sugars were corrected by a substrate-only control before plotting or further calculations.

To evaluate whether proteins acted synergistically, the expected and measured product concentrations were compared. To calculate the expected product formation, the individual activities of all proteins in each set were summed and compared to the product formed by the set of proteins together. Expected and measured activities were always compared within the same biological replicate, to minimize batch effects, using the paired two-tailed t-test. If only technical replicates were performed, unpaired two-tailed t-tests were used. For plotting of synergistic effects, the ratio of observed product formation over expected product formation for each replicate was calculated, with values > 1 indicating synergistic effects.

GraphPad Prism 10.3 (GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA) was used for calculations and statistical analysis.

Elution shift assay

Amy4Δdoc, Amy4Δcoh, and Amy16 were purified from flash-frozen dialysate by SEC, using a HEPES-based buffer (25 mM HEPES, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 2 mM DTT). Five samples were prepared for the analytical SEC run: Amy16, Amy4Δdoc, and Amy4Δcoh individually, Amy16 + Amy4Δdoc, and Amy16 + Amy4Δcoh. Each enzyme was used at 1 µM concentration. Samples were filtered using a spin column. 50 µL of each sample were applied to a Superose 6 increase 5/150 GL column, run at 0.2 mL/min, while measuring absorption at 280 nm and tryptophan fluorescence at 330 nm (Agilent 1200 Series HPLC).

Cryo-ET sample preparation

R. bromii cells were grown for 20 h in M2 medium containing either fructose or RS as the sole carbon source. For fructose samples, cells were harvested for 5 min at 4000 × g and resuspended in PBS to a final OD (600 nm) of 5. Cu 200-mesh R0.6/1 (Quantifoil) grids were plasma-cleaned for 1 min (Pelco EasyGlow). 3 µL of cell suspension were added, and grids were blotted from the back for 12 s before plunging into liquid ethane using a manual plunge-freezer.

For RS samples, the suspension culture was diluted 1:1 with PBS, and 3 µL were directly applied to glow-discharged Cu 200-mesh R2/1 grids (Quantifoil), and blotted from the back for 8–10 s before plunge-freezing in liquid ethane.

Cryo-FIB milling

EM grids were clipped into AutoGrids with a cutout for FIB milling (ThermoFisher Scientific). FIB milling was conducted using a Gallium source operated at 30 kV either on an Auriga 40 CrossBeam (Zeiss) at the Centre for Microscopy and Image Analysis at the University of Zurich or an Aquilos 2 (ThermoFisher Scientific) at the EMBL Imaging Center in Heidelberg. In all cases, micro expansion joints were used.

At the Auriga, samples were sputtered with 6 nm of platinum before loading into the microscope, where they were additionally coated with an organometallic platinum layer. Sample thinning was controlled manually through the Nanopatterning and Visualization Engine, with current steps 240 pA, 120 pA, 50 pA and a final polishing step at 20 pA to a set thickness of 170 nm.

On the Aquilos 2, samples were sputtered with platinum directly after loading into the microscope and after polishing was complete. Additionally, a layer of organometallic platinum was added before FIB milling. Milling was controlled using AutoTEM (ThermoFisher Scientific), with current steps 1 nA, 0.5 nA, 0.3 nA and a two-step polishing with 50 pA and 30 pA to a set thickness of 150 nm.

Cryo-ET data acquisition and preprocessing

Cryo-ET data of FIB lamellae were acquired using a Titan Krios (FEI) operated at 300 kV, equipped with an energy filter and K2 summit detector (Gatan). Acquisition was controlled using SerialEM 4.163. First, grid overviews were acquired at 175x magnification to identify lamella sites. Then, a medium-magnification montage of each lamella was acquired at 6500x magnification (calibrated pixel size 2.20 nm/px) to select positions for cryo-ET data acquisition using PACEtomo64. Low-magnification tomograms were acquired at ×8700 magnification (pixel size 1.67 nm/px) using a total dose of 20 e−/Å2 in a bidirectional acquisition scheme of 3° increments. Other tomograms were acquired at ×33,000 or ×105,000 magnification (calibrated pixel size 0.4039 nm/px and 0.1344 nm/px, respectively) in a dose-symmetric scheme with 3° increments starting from the lamella pre-tilt, with a total dose of 120–140 e−/Å2.