Abstract

Controlling electron dynamics at optical clock rates is a fundamental challenge in lightwave-driven nanoelectronics and quantum technology. Here, we demonstrate ultrafast charge-state manipulation of individual selenium vacancies in monolayer and bilayer tungsten diselenide using picosecond terahertz source pulses, focused onto the junction of a scanning tunneling microscope. Using pump–probe time-domain sampling of the defect charge population, we capture atomic-scale snapshots of the transient Coulomb blockade, a hallmark of charge transport via quantized defect states. We leverage the Franck–Condon blockade, which restricts accessible vibronic transitions and promotes unidirectional charge transport, to effectively mitigate back tunneling to the tip electrode. Our master equation approach models the non-reciprocal tunneling process due to vibrations and angular momentum multiplicities, accurately reproducing the time-dependent tunneling current across different coupling regimes. Capturing and controlling ultrafast charge dynamics in low-dimensional materials at the atomic scale opens frontiers in lightwave-driven nanoscale science and technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Artificial atom qubits, such as quantum dots (QDs) and color centers, have attracted significant interest in light of their applications in quantum sensing, communication, and photonic quantum computing1,2,3. In particular, the inherently strong confinement for solid-state atomic-scale defects imposes a large characteristic energy scale that leads to exceptionally long coherence times, and operability beyond cryogenic environments4. Spin-selective optical decay pathways enable high-fidelity spin initialization and optical readout5. While optical access is advantageous for addressing individual QDs at THz to PHz frequencies6, electrical interfaces offer crucial benefits for scalable on-chip integration. The primary engineering challenge lies in developing suitable leads for atomic interfaces. Although extreme ultraviolet lithography is making progress towards atomic contacts, scanning probe hydrogen resist lithography7,8 has already demonstrated proof-of-concept devices. Promising candidates for well-defined atomic interfaces are two-dimensional (2D) materials that are chemically versatile, tunable via external fields, and they can host atomic-scale QDs9. Several spin-bearing, optically active defect emitters have been identified in transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs)10,11 and hexagonal boron nitride12,13, including substitutional defects and vacancies. However, achieving device-scale electron transport through single defects in 2D materials has so far remained elusive.

The tunneling contact in scanning probe microscopy offers a means of studying quantized electron transport through single defects and exploring the Coulomb blockade regime at the atomic scale. Steady-state Coulomb blockade of adatoms, molecules, and defects has previously been observed in scanning tunneling microscopy (STM)14,15,16. Dangling bonds of an H-terminated Si surface have been demonstrated to exhibit quantized transport8,17 and Coulomb blockade8. Similarly, chalcogen vacancy defects in TMDs introduce discrete defect states deep in the band gap of the host material, with narrow defect resonances followed by vibronic sidebands18,19. These defect states can be probed individually via scanning tunneling spectroscopy (STS), revealing the influence of spin-orbit coupling18 and layer-dependent binding energy16,20. To operate and control single-electron dynamics in these atomic QDs at their natural time scale, ultrafast probes are required. Recent technological advancements in ultrafast probes now bring this vision within reach, making it possible to capture “movies” with simultaneous picosecond temporal resolution, millielectronvolt energy resolution, and picometer spatial precision21,22. Ultrafast STM has resolved charge carrier dynamics in semiconductors23,24, coherent lattice dynamics of bulk crystals25,26, single molecules27, and atomic defects28,29. However, the direct observation of ultrafast single-electron dynamics at the atomic scale has remained an open challenge.

Here, we address this challenge by demonstrating ultrafast Coulomb blockade at an atomic defect in a 2D semiconductor by lightwave-driven STM (LW-STM). By applying tailored single-cycle THz pulses to the STM tip, we achieve a controlled population of atomic defect orbitals and trace their subsequent depletion in the time domain. The temporal evolution of the Coulomb blockade quantifies the charge-state lifetime of selenium vacancies (VacSe) in WSe2/graphene heterostructures. By controlling the coupling strength of the tunnel junction via dc bias and tip–sample distance, along with a theoretical model utilizing the master equation, we identify the Franck–Condon blockade as a key mechanism to prevent back tunneling to the source electrode. This study represents the direct observation of ultrafast electron dynamics at the atomic scale with LW-STM, opening new avenues for advancing our microscopic understanding and control of ultrafast electron transport at atomic length scales.

Results and discussion

Coulomb blockade at a single Selenium vacancy

The STM geometry enables the resonant exchange of electrons (e−) in the single-atom VacSe QD between tip (source electrode) and sample (drain) through sequential tunneling processes (Fig. 1a, b). A finite tunneling current occurs if the e− exchange proceeds in series, i.e., from the source (tip) to the QD to the drain (substrate), or vice versa. Thereby, the coupling strength to the source and drain can be precisely controlled via the tip–sample distance and TMD layer thickness, respectively. In standard STM/STS, static lead potentials enable measuring energy-selective, stochastic tunneling processes and average QD populations. Ultrafast pump-probe schemes in LW-STM allow us to access also the charge dynamics of the atomic QD. In the near-field of the tunneling junction, strong-field THz source pulses act as ultrafast bias transients that add to any static dc bias, as illustrated schematically in the equivalent circuit diagram in Fig. 1c. We preserve state-selectivity of the tunneling process by tailoring the amplitude and carrier-envelope phase of the THz transient to a single-cycle, unipolar pulse resonant with an electronic defect state27,30,31.

a Illustration of the experiment: VacSe in two monolayer (2 ML) WSe2 on quasi free standing epitaxial graphene (QFEG) and conductive SiC studied with lightwave-driven STM. Free-space propagating THz pulses induce transient voltage bursts at the STM tip that enable electron tunneling into localized defect states of VacSe. b Energy diagram illustrating electron tunneling from the tip to the VacSe in a double-barrier model, where the Fermi level (EF) is pinned by the QFEG substrate. The electron transfer depends on the different coupling strengths Γ, which are based on energy (voltage) differences, the tip-sample spacing z and the WSe2 layer thickness d that determines the coupling of VacSe to the tip (T) and the substrate (S), respectively. The charge occupation at VacSe exponentially relaxes to its equilibrium state. c Schematic representation of sequential electron tunneling depicted as an equivalent circuit. The time-dependent tip voltage bias (Vt) is the sum of: (i) constant Vdc, and (ii) single THz voltage pulse with peak amplitude \({V}_{{{{\rm{THz}}}}}^{{{{\rm{pk}}}}}\), or (iii) pump and probe THz pulses with individual amplitude and time delay Δt.

The key observable in LW-STM is the rectified charge QLW transferred between tip and substrate per lightwave (THz) transient. Similar to the current in conventional STM, QLW can be efficiently increased by reducing the tip-sample distance z. In a QD geometry, a rectified charge requires two consecutive tunneling events from one lead to another via the discrete QD state. Here, two regimes can be distinguished: QLW ≤ 1e/pulse and QLW > 1 e/pulse. In the latter regime, multiple e− tunnel per source pulse, which is only possible if the state that facilitates tunneling is short-lived, indicating strong QD–substrate coupling, ΓS, where the charge-state lifetime (τ0) is much shorter than the source pulse duration (τLW), \({\tau }_{0}={\Gamma }_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}^{-1}\ll {\tau }_{{{{\rm{LW}}}}}\). The coupling of the tip electrode can be tuned continuously from the weak-injection regime, (\({\Gamma }_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}^{-1}\gg {\tau }_{{{{\rm{LW}}}}}\)) to the strong-injection regime. In van der Waals materials, and in particular for localized in-gap states (orbitals), the weak coupling between layers and across 2D heterostructures results in long-lived excitations. As a result, the regime of QLW > 1 e/pulse is not always accessible, because the large Coulomb energy associated with double charging of the QD inhibits multiple electron transfers within the short pulse duration. However, by using two time-delayed THz pulses, it becomes possible to probe e−–e− correlations, such as the Coulomb blockade in the time domain.

Previous studies could show that the average charge-state lifetime τ0 can be estimated via the maximum tunneling rate at saturated current through a localized state15,32. Specifically, when the tip–sample coupling ΓT greatly exceeds the substrate coupling ΓS, the relationship \({\Gamma }_{{{{\rm{tot}}}}}^{-1}={\Gamma }_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}^{-1}+{\Gamma }_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}^{-1}\approx {\tau }_{0}\) holds, which can be achieved by approaching the tip. Additional WSe2 layers effectively decouple VacSe and substrate, allowing control over τ0 across several orders of magnitude. In a previous study, we reported average charge-state lifetimes of single VacSe in the top layer of 1–4 ML WSe2, ranging from 1 ps to several ns16. Owing to the spatial distribution of the defect orbital, top and bottom VacSe in the same layer exhibit similar coupling strength to the substrate and thus comparable charge-state lifetime16. This study lays the basis for investigating ultrafast charge dynamics in the time domain using LW-STM. As a starting point, we consider a neutral VacSe in 1 ML and 2 ML WSe2 characterized by the LUMO and LUMO+1 states (Fig. 2a), residing in the unoccupied spectrum of the WSe2 band gap. STM topography and orbital images reveal the three-fold symmetric orbital shape of the defect state (Fig. 2b)18.

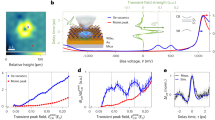

a dI/dV spectra of VacSe in 1 ML (yellow) and 2 ML (turquoise) referenced to pristine WSe2 (gray). b STM topography and constant-height dI/dV orbital mapping of a top VacSe in 2 ML WSe2. The height set point z0 corresponds to Vdc = 1.2 V and Idc = 100 pA (Methods). c LW-STS of VacSe in 1 ML (yellow) and 2 ML (blue), each referenced to pristine WSe2 (gray). The tip–sample distance is z0 − 4 Å for 1 ML and z0 − 3 Å for 2 ML. d LW-STM orbital images of VacSe in 1 ML (upper panels) and 2 ML (lower panels) at THz peak voltage indicated with (i)–(iv) in (c). All lightwave measurements are performed at Vdc = 0 V. Integration time per data point is 2 s for LW-STS and 20 ms for LW-STM, corresponding to 20 M and 0.2 M THz pulses at 10 MHz repetition rate.

Quenching of lightwave-driven orbital imaging

To maximize the time resolution of THz pulses, the majority of LW-STM/STS experiments have so far been performed in a configuration where Vdc ≪ VTHz and at or close to Vdc = 0 V to minimize dc background currents. Figure 2c shows the rectified charge per THz waveform (transient) in units e/tr as a function of peak THz voltage, which, in first order, reproduces the I(V) characteristic of the tunnel junction28. The onset of the two rising edges in the \({Q}_{{{{\rm{LW}}}}}({V}_{{{{\rm{THz}}}}}^{{{{\rm{pk}}}}})\) curve (black arrows) aligns with the expected spectral locations of the lowest unoccupied molecular/defect orbital (LUMO) and LUMO+1. Additionally, the LW-STM map of the LUMO [Fig. 2d (i)] closely resembles the dc STM measurement. However, the situation is strikingly different for LW-STS of VacSe on 2 ML WSe2 (Fig. 2c turquoise). In this case, we are unable to resolve the defect states through LW-STM [Fig. 2d (iii) and (iv)], even though their STS spectrum matches closely the spectrum of VacSe on 1 ML WSe2. Instead of observing an enhancement in the LW-driven rectification at the defect position, which would typically arise from additional tunneling channels, we see a reduction of LW-driven tunneling at the defect center. This observation suggests that the VacSe on 2 ML WSe2 enters a different lifetime regime, affecting the ultrafast tunneling process. The sub-nm point-like reduction of LW rectification to the conduction band in configurations (ii) and (iv) differs from the defect orbital and appears as a consequence of local band bending due to the charged VacSe33,34.

We attribute the loss of in-gap defect state contrast in 2 ML to an enhanced charge-state lifetime, related to the electronic decoupling of VacSe via the additional WSe2 layer16. The average charge-state lifetime of different VacSe/2 ML obtained from dc current saturation measurements ranges from \({\tau }_{0}^{{{{\rm{2\,ML}}}}}=50 \;{{\rm{to}}}\; 86 \, {{\rm{ps}}}\) (Fig. S1), significantly longer than the sub-1 ps source voltage duration. Consequently, multiple tunneling events per pulse are highly unlikely. Subsequently to the injection by the source pulse, the e− can relax through two possible pathways: (i) forward tunneling to the substrate, contributing to a measurable current, or (ii) backward tunneling to the tip. Due to the small duty cycle in LW-STM, intermediate to strong charge injection from the tip is required to facilitate tunneling within the short duration of the THz peak field. Hence, back tunneling is the more probable pathway if the charge-state lifetime exceeds a few picoseconds, quenching charge rectification. As a result, a transiently charged VacSe in 2 ML is more likely to relax by discharging via the STM tip (back tunneling) instead of the substrate (forward tunneling), resulting in zero net charge rectification. In contrast, the smaller lifetime of VacSe in 1 ML (\({\tau }_{0}^{{{{\rm{1\,ML}}}}} < 3\) ps) enables notable charge rectification from tip to substrate during the transient THz pulse, which explains the orbital contrast observed in the LW-STM images for VacSe in 1 ML WSe2. For THz peak voltages reaching the conduction band, femtosecond carrier relaxation and strong delocalization of continuum states enable sub-cycle charge rectification during the THz gate, irrespective of the layer thickness, yielding an unperturbed onset of conduction band states (gray curves in Fig. 2c).

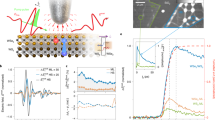

Back tunneling suppression via Franck–Condon blockade

Next, we study the effect of the dc bias on THz charge rectification for a VacSe in 2 ML (Fig. 3a). To ensure comparability across different VacSe, we define a relative voltage offset from the LUMO ΔVz = Vdc − VLUMO(z) to account for local shifts of the relative LUMO position with tip height, lateral tip position, and sample heterogeneity (Methods). The first two factors arise from the well-known voltage drop across a double-barrier tunneling junction35. In contrast to Fig. 2d (iii), where we set Vdc = 0 V, we start to observe orbital contrast in LW-STM as Vdc nears the LUMO resonance, as seen in Fig. 3b. This effect becomes more pronounced as ΔVz approaches zero. We attribute the reestablished LW-STM contrast to a suppression of back tunneling. This suppression can be explained by the so-called Franck–Condon blockade36, which is more significant than the (slowly-varying) bias-dependent change of the tunneling barrier. Note that the orbital shape of VacSe in Fig. 3b appears saturated, unlike in the monolayer case in Fig. 2d (i). Due to the required ΔV ≈ 0 V, dc electrons block the THz electrons at some tip positions. The same orbital shape as for the 1 ML case can be recovered for specific Vdc and tip heights, as shown in Fig. 4b. When Vdc exceeds the onset of the VacSe resonance (ΔVz > 0 V), significant dc currents occur, eventually leading to the saturation of Idc and causing charge fluctuations that substantially increase the noise in the THz current (Fig. 3c).

a Schematic illustration of reduced back tunneling rate at elevated Vdc. b LW-STM orbital images of VacSe/2 ML showing a strong nonlinear increase of net rectified charge and orbital sensitivity as ΔV = VLUMO − Vdc → 0 V. Measurement obtained at \({V}_{{{{\rm{THz}}}}}^{{{{\rm{pk}}}}}=0.49\) V, VLUMO = 0.7 V, and z = z0 −3 Å. c dI/dV (green shaded curve) and I(V) spectrum (black, upper panel) and rectified charge (black, lower panel) as a function of Vdc measured with \({V}_{{{{\rm{THz}}}}}^{{{{\rm{pk}}}}}=0.32\) V and z = z0 − 3 Å. The simulation (red curve) assumes a single vibrational mode ℏΩ = 8 meV, a Huang-Rhys factor of 2.2, and experiment values for THz waveform, LDOS and z (Methods). The data for (b) and (c) were obtained on \({{{{\rm{Vac}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Se}}}}}^{2.2}\) and \({{{{\rm{Vac}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Se}}}}}^{2.4}\) respectively (Fig. S1). Black crosses in panel b indicate an equivalent position of the point spectrum. Integration time per data point is 100 ms for LW-STS and 15 ms for LW-STM, corresponding to 4.1 M and 0.6 M THz pulses at 41 MHz repetition rate. d Transitions between vibronic states of the charged and neutral VacSe LUMO in the Franck–Condon picture at high Vdc(ΔV → 0 V) are limited to ground state transitions. e At reduced Vdc transitions to higher vibronic modes of the neutral state become available, enhancing the effect of back tunneling.

a Schematic illustration of the electronic coupling strength of VacSe to the STM tip at different tip height. b LW-STM orbital images with \({V}_{{{{\rm{THz}}}}}^{{{{\rm{pk}}}}}=0.49\) V and at Vdc = 0.7 V (\(\Delta {V}_{{z}_{0}}=0.0\) V). Images left to right at increasing tip—sample distance show a transition from the saturated (Δz = −3.5 Å) to the unsaturated (Δz = −1 Å) orbital shape. Reduced charge rectification at the center of VacSe at Δz = −3.5 Å is related to strong back tunneling, i.e., efficient charge depletion by the tip. The dotted line marks the position for cross sections in Fig. S5b. c QLW point spectrum (black curve) as a function of tip--sample distance measured on the orbital lobe of VacSe. The maximum at −2.5 Å emphasizes the interplay of forward and backward tunneling, modeled by a simulation (red) that assumes a single vibrational mode with an energy of 8 meV and a Huang-Rhys factor of 2.2 (Methods). The data for b and d were obtained on \({{{{\rm{Vac}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Se}}}}}^{2.2}\) and \({{{{\rm{Vac}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Se}}}}}^{2.4}\) respectively (Fig. S1). Black crosses in b mark the equivalent position of the point spectrum in (c). Integration time per data point is 100 ms for z-spectroscopy and 15 ms for LW-STM, corresponding to 4.1 M and 0.6 M THz pulses at 41 MHz repetition rate.

In the Franck–Condon blockade regime, changes in the phonon population of a defect can introduce an asymmetry between forward and backward tunneling. In Fig. 3d, e, the principle of the Franck–Condon blockade is schematically illustrated. Within the Franck–Condon approximation, each charge-state of the defect is represented by a harmonic potential with a single vibrational mode of characteristic energy ℏΩ. Due to fast vibrational cooling in 2D semiconductors37 (curved black arrow), charge-state transitions primarily occur from the vibrational ground state (dark red), centered around the relaxed nuclei positions. The displacement of the potential energy surface between different charge states increases with the electron-phonon coupling strength. As a result, electron transfer (vertical blue arrows) is generally accompanied by vibrational excitation. However, when the dc bias is set close (within the order of the vibrational energy) to the LUMO orbital energy (Fig. 3d), the overlap with energetically accessible low-lying vibrational states of the neutral defect is greatly reduced38. In contrast, when the dc bias is much lower (Fig. 3e), all vibrationally excited states remain accessible. Consequently, back tunneling can be significantly suppressed by raising the electrochemical potential of the tip.

We model the transient charging and discharging of the atomic defect by a time-dependent Markov process, described by the so-called Master equation, as detailed in the Methods section. This model treats the defect by three electronic states (one ground state and two charged states, LUMO and LUMO+1), as well as a single vibrational mode (ℏΩ ≈ 8 meV) with multiple quanta, and a Huang-Rhys factor of S ≈ 2.2 for a VacSe in 2 ML WSe2. These parameters are extracted from experimental STS spectra and the average charge-state lifetime τ0 from STM approach curves (Fig. S6a, b). The transition matrix is expressed as the sum of the transition rates due to sample, tip, and phonon relaxation. To calculate the rectified charge, we model the actual waveform of the THz transient (Fig. S6c). The simulations, shown in Fig. 3c (red), qualitatively and quantitatively reproduce the steep increase of the THz current as a function of dc bias within tens of meV of the defect resonance. Importantly, the strong suppression of back tunneling at elevated bias is attributed to a reduction in the energetically allowed vibronic transitions into the neutral state. The Franck–Condon blockade acts as an effective backflow valve, favoring unidirectional charge transport when charge-state lifetimes exceed the pulse duration, which is crucial for achieving charge rectification in LW-STM.

Optimal tip distance between weak and strong coupling

The coupling of the atomic QD to the tip contact not only sensitively depends on the tip bias, but also on the tip–sample distance (Fig. 4a). Figure 4b shows a series of LW-STM images illustrating the evolution of the orbital contrast at different tip heights at Vdc = 0.7 V, corresponding to ΔV = 0 at z0. In contrast to Fig. 2c the orbital images are saturated as a consequence of a transient population that produces a convolution of defect orbital and a local variation in Franck–Condon blockade. The black curve in Fig. 4c presents a QLW approach curve obtained on a VacSe orbital lobe. Both spatial (Fig. 4b) and height (Fig. 4c) dependence reveal an initial increase, followed by a decrease of the LW signal as the tip approaches the defect. Initially, reducing the tip height compensates for the short duty cycle in LW-STM and enhances the signal. However, at very close distances, stronger back tunneling suppresses the rectified current, resulting in a maximum rectification near z − z0 = − 2.5 Å. Two factors contribute to this effect: Due to the voltage drop across the WSe2 layers, smaller tip heights (or closer lateral tip position) shift the LUMO resonance to higher voltages, thereby reducing ΔV and thus enhancing back tunneling, as previously discussed. Additionally, the increasing tunneling rate ΓT(z) becomes much larger than the defect–graphene tunneling rate, ΓS. This promotes back tunneling, dominating over the Franck–Condon blockade. Our simulations (Fig. 4c, red) reproduce the shape and magnitude of the experimental QLW(z) curve, accounting for both the z-dependent voltage drop and the increase in ΓT(z). While quenching of excited states via electron transfer to the tip was previously reported for photo-excited molecules39,40, here we directly map this process with ultrafast time resolution.

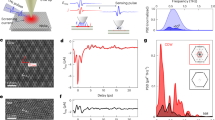

Time-domain detection of the ultrafast Coulomb blockade

Finding optimal parameters for ΔV and z enables time-domain mapping of the transient Coulomb blockade close to its average charge-state lifetime. Here, we use a sequence of two time-delayed THz transients in combination with Vdc, such that Vdc+\({V}_{{{{\rm{THz}}}}}^{{{{\rm{pk}}}}}\) accesses the localized in-gap defect state, but remains below the onset of the conduction band (Fig. 5a, d). In Fig. 5b, e, we show the transient Coulomb blockade at VacSe in 1 and 2 ML WSe2. In these measurements, QLW(Δt) describes the rectified charge by the probe transient only (kHz amplitude modulation), while the pump transients interact at full repetition rate (41 MHz). Near the overlap Δt = 0 ps, the signal is dominated by interference between the THz waveforms, such that we restrict our analysis to time delays Δt > 1.5 ps. For time delays much longer than the average charge-state lifetime τ0, the transient signal recovers to the equilibrium value \({Q}_{{{{\rm{THz}}}}}^{{{{\rm{eq}}}}}\), corresponding to unperturbed rectification by the probe transient. For orbital images acquired at different time delays, we plot the relative change of rectified charge \(\Delta {Q}_{{{{\rm{THz}}}}}={Q}_{{{{\rm{THz}}}}}-{Q}_{{{{\rm{THz}}}}}^{{{{\rm{eq}}}}}\), obtained by subtraction of a reference map at a large delay (Δt ≫ τ0). The differential images clearly reveal the orbital structure of VacSe with negative amplitude, providing a direct and dynamic visualization of a Coulomb blockade at the atomic scale.

a STM topography and STS spectrum of VacSe in 1 ML WSe2. The gray spectrum references pristine WSe2. The illustration shows the concept of pump-probe measurements, where a THz pump pulse (red) charges the system while a time-delayed THz probe pulse (blue) measures the transient charge occupation. b The rectified charge of the THz probe pulse as a function of THz–THz delay. The black line is an exponential fit to the relaxation of the charge state. Orbital images at selected delays, illustrating the change of rectified charge ΔQLW with respect to an equilibrium reference at 10 ps. c Dependence of the charge-state lifetime extracted via exponential fitting in panel b as a function of ΔV = VLUMO − Vdc. The horizontal line (gray) marks the intrinsic charge-state lifetime from dc measurements. Error bars correspond to the fit uncertainty, and lifetime values below 0.5 ps are shorter than the time resolution of the experiment. d–f Same analysis for VacSe in 2 ML. Due to significant THz reflections, apparent as dips in QLW(Δt), the extraction of a charge-state lifetime from the pump-probe measurement in panel (e) must be matched with a simulation as detailed in the Methods. The data was obtained on different VacSe characterized in Fig. S1: a–c at \({{{{\rm{Vac}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Se}}}}}^{1.2}\), d–e at \({{{{\rm{Vac}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Se}}}}}^{2.3}\), and f at \({{{{\rm{Vac}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Se}}}}}^{2.4}\). Integration time per data point is 100 ms for LW-STS and 30 ms (1 ML) or 15 ms (2 ML) for LW-STM, corresponding to 4.1 M and 1.2 M or 0.6 M THz pulses at 41 MHz repetition rate.

We model the lightwave-driven pump-probe (LW-PP) point spectrum by a single exponential fit (dashed black line) that allows to extract the relaxation dynamics of the VacSe QD. This effective charge-state lifetime τeff combines the interplay of intrinsic charge relaxation to the substrate and ultrafast back tunneling to the tip. To disentangle these contributions, we record LW-PP spectra at increasing Vdc. We determine τeff via exponential fitting of the spectra at time delays between 1.5 ps and 12 ps, ensuring robust convergence of fit parameters. The error bar includes disturbances related to THz trailing oscillations at high Vdc. τeff strongly increases as ΔV → 0 and peaks near ΔV = 0 V, where it reaches the intrinsic charge-state lifetime τ0 (Fig. 5c). At ΔV ~ 0 V, back tunneling is strongly suppressed and the intrinsic relaxation channel to the substrate becomes the dominant mechanism for charge relaxation. Notably, the effective charge-state lifetime is rapidly quenched for negative ΔV. This highlights the critical role of the Franck–Condon blockade for this experiment. At ΔV < − 50 mV the time resolution and transient signal amplitude become insufficient to resolve the Coulomb blockade. Our master equation model enables simulations of charge rectification at various time delays using a model of our experimental waveform (Methods). Exponential fitting of simulated LW-PP spectra with similar boundary conditions as in the experiment clearly reveals the trend of increasing effective charge-state lifetime near ΔV = 0 V (Fig. 5c). The onset of quasi-static charging at dc biases above the LUMO resonance, as shown in Fig. 3c, precludes ultrafast measurements due to dominant stochastic tunneling.

We performed the same series of measurements at a VacSe in 2 ML WSe2 with an intrinsic charge-state lifetime τ0 = 86 ps. As the charge-state lifetime exceeds the time window of trailing reflections from windows in our beam path, which can amount up to 30% field amplitude (Fig. S2), QLW(Δt) deviates from a simple exponential decay, instead displaying dips indicative of interference with these reflections. Since ΔV values close to 0 V are necessary to suppress back tunneling effectively, the impact of trailing reflections on the measurements can only be minimized, though not entirely eliminated. At elevated Vdc close to the onset of the defect state, the amplitude of THz pulse reflections is sufficiently high to interact with the VacSe states, causing additional excitations and experimental replica at various time delays. Nevertheless, an ultrafast Coulomb blockade lasting over few-10 ps is clearly revealed by the LW-PP spectrum and ultrafast orbital images in Fig. 5e. For simple and robust extraction of an effective charge-state lifetime, we determine the equilibrium signal at Δt > 250 ps and fit a single exponential model only to the unperturbed data from 1.5 to 15 ps. Simulated LW-PP spectra on the basis of the Franck–Condon blockade and the full transient waveform with multiple reflections quantitatively model the experiment, including the effect of THz pulse reflections (Methods, Fig. S2). Limiting the fit interval to Δt < 15 ps causes large fit errors for τeff ≳ 20 ps, however, it ensures robustness of the fit in experiment and simulation. Again, the sharp decrease of τeff with more negative ΔV emphasizes the increasing relevance of back tunneling for VacSe in 2 ML with extended τ0. As ΔV strongly depends on the lateral and vertical position of the tip, distinct ΔV regimes can coexist within a single LW-STM image. In the defect periphery, where ΔV > 0, large dc currents permanently charge the defect, effectively quenching QLW. At the circular transition region, where ΔV ≈ 0, charge fluctuations dominate, leading to significant noise in QLW (Fig. S5c).

The lack of a WSe2 moiré structure in our sample reduces mechanical strain and facilitates fast delocalization of phononic excitations. At time scales <5 ps, signatures of coherent motion of the WSe2 layer interfere with THz field-induced modulations and remain indistinguishable in the experiment. In consequence, we do not resolve a coherent motion of the WSe2 layer or energy modulation of the defect state driven by inelastic excitations of the VacSe states as reported by Roelcke et al.28, which would also modulate the Franck–Condon blockade significantly. In contrast to fast charge relaxation on a metallic substrate, finite charge-state lifetimes and the Coulomb blockade in our samples impose a stochastically uncorrelated perturbation to any coherent signal since the charge relaxation is not phase locked. Furthermore, the decoherence of lattice excitations is amplified by charge transfers from pulse replicas that become relevant at elevated Vdc.

In conclusion, using THz pump–THz probe time-domain sampling, we capture real-space snapshots of the transient Coulomb blockade. By fine-tuning the transient THz waveform, dc bias offset, and tip height, we selectively populate specific defect orbitals of single selenium vacancies in monolayer and bilayer WSe2 and track the charge transfer into the substrate. A rate equation model accurately describes the time-dependent tunneling process across the different coupling regimes, applicable to other materials and quantum systems. Our experiments overcome challenges posed by back tunneling, revealing a Coulomb blockade that persists for two orders of magnitude longer than the duration of THz voltage pulses. Quenching of the LW-STM signal due to population depletion by the tip electrode is mitigated by breaking the symmetry between charge transfer from and to the tip via the Franck–Condon blockade, acting as a charge backflow valve. The Franck–Condon blockade drastically reduces the charge-transfer rate from the defect state to the tip by limiting the number of available vibrational transitions. Precise control of the transient bias and coupling strength between the STM tip and the defect state enables net charge rectification, essential for LW-STM measurements. This work complements recent advances in observing defect resonances29, coherent lattice dynamics28, charge density waves41, and bidirectional subcycle tunneling currents42 with LW-STM, establishing a pathway for probing ultrafast charge dynamics in low-dimensional materials and localized quantum states. We envision that tunneling asymmetries induced by vibrational transitions, spin and orbital momentum multiplicities will enable lightwave-driven charge control in complex materials, pushing the frontiers of ultrafast nanoscale electronics.

Methods

Sample preparation

Our WSe2 samples are grown via metal organic chemical vapor deposition on few-layer epitaxial graphene supported by a conductive silicon carbide (c-SiC) substrate. The plasma frequency of c-SiC is sufficient to effectively suppress THz reflections from the bottom surface. Intercalation of the graphene layers with hydrogen prior to WSe2 growth terminates the dangling silicon bonds, providing a homogeneous electrostatic background. Further details of the sample growth procedure were previously reported along references16,43. Key advantages of epitaxially grown samples on quasi-free-standing graphene (QFEG) are the electronic homogeneity (no moiré), a Fermi energy pinned in the center of the large WSe2 band gap, and weak hybridization with the substrate16. The strong out-of-plane confinement facilitates electron-phonon coupling, well-defined defect states, and high contrast of the defect states inside the band gap, enabling LW-STM at nonzero Vdc.

High-temperature annealing in UHV is required to clean samples after ambient exposure. We generate isolated VacSe in the top WSe2 layer via light sputtering with Ar ions, approximately 2 s at 0.12 kV acceleration bias, 0.16 kV discharge voltage, and a sub-μA sputter-current16. Multiple VacSe in 1–2 ML WSe2 were investigated for this study, emphasizing the robustness and repeatability of the technique. Fig. S1 lists STM topography, dI/dV spectra, and current saturation curves of the relevant VacSe.

STM height set point and average charge-state lifetime

For a reproducible definition of the tip height z0, the STM feedback loop was opened on pristine WSe2 at a set point current of 100 pA with applied bias voltage of 1.5 V (1 ML) or 1.2 V (2 ML), corresponding to an energy 200 meV above the conduction band onset. We estimate an absolute tip–sample distance at z0 of (7 ± 2) Å. The average charge-state lifetime (τ0) of VacSe states scales with the decoupling layers of the sample and is determined via the current saturation in STM approach curves15,16,32. For simplicity, we consider only the first unoccupied defect state (LUMO) of VacSe for the determination of τ0. Reduced localization due to a lower binding energy slightly reduces the average charge-state lifetime of the LUMO+1 defect state16. For different VacSe, τ0 slightly vary due to differences in their dielectric environment, however, the energy spectra and orbital shape remain comparable within a few-10 meV shifts (Fig. S1).

Voltage drop and definition of ΔV

In our double barrier tunneling junction geometry, the effective voltage from the tip to the VacSe defect states depends on the WSe2 dielectric screening and the absolute height set point z0. The relative voltage ΔV = Vdc − VLUMO(z) is important to compare LW-STM data across different VacSe, where the onset of the LUMO, VLUMO(z), varies on the order of tens of meV due to inhomogeneity of the sample and as a function of z. While for ΔV < 0 the dc current is negligible, ΔV > 0 V generates a notable dc current and thus increases the VacSe population statically in the experiment. In orbital imaging, we define ΔV at a single point on the orbital lobe of VacSe, avoiding complications of lateral dependence. We determine VLUMO(z) directly from a dI/dV measurement at z or via extrapolation of VLUMO(z0) on the basis of measurements performed in ref. 16, Fig. 2. Owing to the high sensitivity towards thermal drifts on the sub-Å scale, we estimate an accuracy δΔV ≈ 10 mV.

LW-STM setup and near-field waveform detection

Our LW-STM system is a commercial low-temperature STM from CreaTec Fischer & Co. GmbH with free-space optical access to the STM junction via large numerical aperture parabolic mirrors focused on the tip apex. THz pulses are generated via tilted pulse front optical rectification in lithium niobate pumped by a multi-MHz Yb:fiber laser with pump pulse energies of a few μJ. The system achieves peak THz voltages at the STM tip up to 0.5, 1, and 2 V at 41, 20, and 10 MHz repetition rates, respectively. We use frustrated internal reflection in a PTFE prism as well as a double or single mirror sequence to adapt the phase and polarity of single-cycle THz pulses at the STM tip44. Pump and probe pulses are generated independently and are recombined in collinear geometry via a c-cut sapphire window. Purging of the optics setup with dry air reduces ambient absorption before pulses are coupled into the vacuum chamber. Operating conditions of the scanning probe microscope are 5 K base temperature and 10−10 mbar pressure.

To discriminate lightwave-driven currents, we mechanically modulate the THz path at an intermediate focus using frequencies between 800 and 1000 Hz that are compatible with the 109 transimpedance amplifier of the STM and show weak mechanical and electric noise. ILW is then extracted via lock-in demodulation and calibrated with respect to the absolute current. We convert current to rectified charge per transient (e/tr) on the basis of the laser repetition rate and the 50% duty cycle of the modulation. In pump-probe measurements, only the probe pulse is modulated, while pump pulses enter the junction at full repetition rate. We find that high DC currents prevent sensitive measurements of QLW because of large noise floors.

The THz peak voltage is calibrated against Vdc using a recently developed approach based on the strongly nonlinear onset of the WSe2 conduction band31 measured in a clean pristine region of the sample (Fig. S2a–c). On the basis of this amplitude calibration, we determine the relative time origin (Δt = 0) and temporal resolution of the experiment (380 fs) by cross correlation of equal THz fields where only the sum field rectifies charges (Fig. S2d). In a second step, we measure the transient near-field waveform at the STM tip using THz cross correlation (THz-CC)29,31. Here, we set relative amplitudes such that a strong THz gate pulse rectifies electrons to the conduction band in a linear section of the dI/dV curve, while a time-delayed weak THz pulse modulates the THz peak voltage. This approach allows waveform characterization without requiring complex retrieval algorithms31,45 (Fig. S2e, f). Waveform sampling at extended delays reveals THz reflections at approximately 40, 60, 80, 100, and 120 ps due to sapphire windows of the vacuum chamber, cryostat, and the beam combiner, which are unavoidable in our setup (Fig. S2g). Thickness variation of sapphire windows and the beam combiner effectively reduces the amplitude of major THz reflection to below 30% of the main pulse, causing reflections at 40 and 80 ps to show distorted waveforms due to interference effects.

Theoretical model

The dynamics observed in the tunnel junction can be well represented by a time-dependent Markov process, which is described by the so called Master equation \(\dot{N}=M\cdot N\), where N is a vector containing the occupation probabilities of all considered states of the system and M is the transition matrix. Here, we considered three distinct electronic states: The electronic ground state at energy E0 = 0 eV, where the defect is charge neutral (Q0 = 0 e), as well as two negatively charged states (Q1,2 = −e), with an additional electron in either the LUMO (E1) or the LUMO+1 (E2). In addition, we model each electronic state with a single vibronic mode with 6 (14) vibrational excitation levels plus the vibrational ground state, yielding a total of 21 (45) different vibronic states for 2 ML (1 ML) WSe2. The different number of required vibrational levels is due to different Huang-Rhys factors between 1 ML and 2 ML WSe2 (see below).

Transition between these states can occur due to inelastic charge transfer between defect and tip or sample, or via vibrational relaxation within one electronic state. Accordingly, the transition matrix can be written as the sum of the transition rates due to sample, tip and phonon relaxation:

The transitions related to a change of charge state are given by

with indices i and f representing the initial and final electronic state, λ and \({\lambda }^{{\prime} }\) the initial and final vibrational state, \({V}_{{\lambda }^{{\prime} }\lambda }\) the Franck–Condon factors, and \({T}_{f{\lambda }^{{\prime} }i\lambda }\) the tunneling matrix element, respectively. ϒfi captures the effect of various multiplicities of the involved states, and Λfi represents their relative coupling strength to the tip.

The tunneling matrix element \({T}_{f{\lambda }^{{\prime} }i\lambda }(z,V)\) describes the tunneling probability of an electron between the tip or sample and the defect state, depending on bias voltage V and distance z between the defect and lead:

with \(\Delta {E}_{f{\lambda }^{{\prime} }i\lambda }\) being the energy difference between the initial and final vibronic state and decay rate \(\kappa=\sqrt{2{m}_{e}(\phi -E+eV/2)}/\hslash\). The transition threshold is broadened by a Gaussian line shape g(E) and normalized to integrate to the quantum of conductance G0 = 2e/ℏ for z = 0.

For the Franck–Condon factors \({V}_{{\lambda }^{{\prime} }\lambda }\), we assume only a rigid shift in normal mode coordinates and negligible Duschinsky rotation46:

with Huang-Rhys factor S and Laguerre polynomials \({L}_{n}^{\alpha }\).

The effect of the various multiplicities on the transition rates is captured by the factor ϒfi. Since we are only considering transitions for which either the final or initial state is a singlet, we can write ϒfi = mf, with mf being the multiplicity of the final state.

The last term Λfi for the tip-mediated transitions captures the relative coupling of LUMO and LUMO+1 to the tip, which can vary with lateral tip position. The additional factor Λfi is normalized to 1 for the tip–LUMO coupling and has typical values between 0.5 and 1.0 for the tip–LUMO+1 coupling, chosen to match the experimental dI/dV spectra.

For the charge-neutral phonon relaxations, the transition matrix is written as a decay to the vibrational ground state with lifetime τph:

Lastly, the diagonal entries of the total transition matrix are set to Mll = −∑k≠lMkl.

For static bias voltages, the master equation is solved for \(\dot{N}=0\) to obtain the bias and z dependent equilibrium occupation Neq. The dc current is then given by the net charge transfer between defect and sample \({I}_{{{{\rm{dc}}}}}={\sum }_{k}{\left({W}^{s}N\right)}_{k}\), with \({W}_{f{\lambda }^{{\prime} }i\lambda }^{s}={M}_{f{\lambda }^{{\prime} }i\lambda }^{s}\cdot ({Q}_{f}-{Q}_{i})\). In order to evaluate the evolution of the system under a transient bias voltage, the master equation is solved in discrete time steps \({N}_{i+1}-{N}_{i}=M\left(V({t}_{i})\right)\Delta t\cdot {N}_{i}\), starting from the equilibrium occupation at Vdc.

Implementation of simulation

The simulations are based on the master equation and require experimental parameters that can be obtained from static measurements of the VacSe (Fig. S1). We extracted the energies of localized defect states E1 and E2 via the zero-phonon lines and the tip coupling factor Lf,i from the experimental dI/dV spectrum at the set point z0. The average charge-state lifetime τ0, and the tunneling barrier κ were obtained via a rate equation fit to the I(z) approach curve16.

The vibronic broadening of the defect state resonances was approximated by a single vibrational mode with ℏΩ = 8 meV and a Huang-Rhys factor of S = 2.2 (2 ML) for both charge states. We find that a Gaussian lineshape with 3 meV bandwidth provides a good match with the experimental dI/dV (Fig. S6b), while being consistent with literature on VacS in WS2, observing a dominant phonon mode of 12 meV and a Huang-Rhys factor of 1.218. Considering an average 40% softening of the phonon modes in WSe2 as compared to WS247, we choose a phonon mode of ℏΩ = 8 meV, and fit the Huang-Rhys factor to the STS spectrum. For the simulations on 1 ML WSe2 we cannot directly fit the vibronic satellite peaks of the LUMO resonance. Instead, we rescale the Huang-Rhys factor from 2 ML WSe2 by a factor of about two, as previously found for CS in 1 ML and 2 ML WS219. Therefore, we choose S = 5 for VacSe in 1 ML WSe2, while we assume the phonon mode energy to remain constant, ℏΩ = 8 meV19.

Although lifetime broadening of a state with tens of picoseconds of lifetime would lead to a Lorentzian lineshape with a few tens of μeV broadening, we justify the choice of Gaussian lineshapes by the presence of additional low-energy vibrational modes with a high Huang-Rhys factor (S ≫ 1), e.g., well-known interlayer phonons for multi-layer TMDs48. These low-energy phonons impose an additional Franck–Condon blockade that explains the difference between simulation and experiment at bias voltages overlapping with the LUMO resonance (ΔV > 0 V). In particular, the breakdown of simulations at ΔV ≈ 10 mV in Fig. 3c emphasizes the limitation of the 1-phonon mode treatment. A thorough 2-mode treatment would require significantly more computational resources without major benefits to our model.

The effective strength of the Franck–Condon blockade also depends on the phonon lifetime τph. We distinguish three regimes in the evolution of charge-state transitions between tip and defect: (I) A voltage gate for charging, (II) vibronic relaxation, and (III) charge relaxation, sketched in Fig. S3. The THz peak voltage \({V}_{{{{\rm{THz}}}}}^{{{{\rm{pk}}}}}\) of few-100 mV enables transitions from the neutral ground state to high vibronic modes of the charged state. Vibronic relaxation in a 2D semiconductor with strong electron-phonon coupling typically occurs faster than the THz gate timescale. Additionally, due to local resolution of LW-STM, combined with the fast lateral diffusion of phonon modes, the atomic-scale QD remains unaffected by the lifetime of acoustic phonons. As a result, we expect relaxation of the charged VacSe to the vibrational ground state within few-100 fs, as seen for thermalization and cooling of photoexcited charge carriers37. We conservatively assume τph = 1 ps for the simulations. After the source pulse and at small ΔV ≲ 0 V, charge-state transitions from low vibrational modes of the charged state have only a few vibrational modes in the neutral state available, creating an asymmetry between forward and backward tunneling that reduces the impact of back tunneling. In addition, our simulation considers the LUMO and LUMO+1 multiplicity as a quartet (J = 3/2) and a sextet (J = 5/2) state, respectively18, further enhancing this asymmetry (Fig. S5).

The voltage drop in 2 ML WSe2 is approximated by a plate capacitor model, \({V}_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}={V}_{{{{\rm{dc}}}}}\frac{z}{z+d/{\epsilon }_{r}}\), with a gap composed of vacuum and WSe2 using a dielectric constant ϵr = 6.5 and d = 6.5 Å for WSe2 layer spacing49 (Fig. S6e). Due to the complex tip shape and iso-potential surfaces that are not parallel to the substrate plane, the voltage drop does not only depends on the tip height z but also on the lateral position of the tip. An accurate description of the effective bias potential can be obtained by integrating the wavefunction with the spatial dependence of the electric potential within the junction50. In most simulations shown in this work, this effect is not crucial to reproduce the experimental data. However, for the QLW(z) measurements, this simple plate capacitor model is not sufficient to model the experiment quantitatively, see Extended Fig. S6g (red line). Because the Franck–Condon blockade depends strongly on the effective applied Vdc, it is very sensitive to changes in the voltage drop and therefore needs a more sophisticated model for the voltage drop. For this reason, we introduced a slightly modified junction model for the QLW(z) measurements. The tip position for tunneling is assumed to be at height z0, whereas the effective plane of the plate capacitor is at a larger distance from the sample zV D > z0 (Fig. S6e–g). For the 1 ML WSe2 the simple plate capacitor model is used with an d/ϵr = 0.1 Å.

To match the simulations of the VacSe in 1 ML WSe2 in Fig. 5 quantitatively, we assume a 0.4 Å uncertainty on the experimental z0 that may arise from small lateral variations in the tip position between the I(z) spectroscopy and THz pump-probe measurements.

The simulation includes a model of the extended transient waveform to reproduce the experimental time-domain signal. Since pump and probe are indistinguishable in the experiment and equally interact with the VacSe state, the Coulomb blockade causes a transient signal that is symmetric at Δt = 0 ps. This significantly impacts measurements at Δt > 15 ps, where transient signals from the main pulse and reflections overlap, causing a non-trivial curvature. Thus, we restrict the data interval for exponential fitting between 1.5 and 15 ps. As another consequence of reflections, extended coherent signals are quenched due to destructive interference from multiple excitations.

Data availability

The data supporting this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

Code is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Weber, J. R. et al. Quantum computing with defects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 8513–8518 (2010).

Awschalom, D. D., Bassett, L. C., Dzurak, A. S., Hu, E. L. & Petta, J. R. Quantum spintronics: engineering and manipulating atom-like spins in semiconductors. Science 339, 1231364 (2013).

Wolfowicz, G. et al. Quantum guidelines for solid-state spin defects. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 906–925 (2021).

Maurer, P. C. et al. Room-temperature quantum bit memory exceeding one second. Science 336, 1283–1286 (2012).

Dolde, F. et al. Room-temperature entanglement between single defect spins in diamond. Nat. Phys. 9, 139 (2013).

Heide, C., Keathley, P. D. & Kling, M. F. Petahertz electronics. Nat. Rev. Phys. 6, 648–662 (2024).

Schofield, S. R. et al. Atomically precise placement of single dopants in Si. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 136104 (2003).

Fuechsle, M. et al. A single-atom transistor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 242–246 (2012).

Liu, X. & Hersam, M. C. 2D materials for quantum information science. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 669–684 (2019).

Klein, J. et al. Site-selectively generated photon emitters in monolayer MoS2 via local helium ion irradiation. Nat. Commun. 10, 2755 (2019).

Lee, Y. et al. Spin-defect qubits in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides operating at telecom wavelengths. Nat. Commun. 13, 7501 (2022).

Tran, T. T., Bray, K., Ford, M. J., Toth, M. & Aharonovich, I. Quantum emission from hexagonal boron nitride monolayers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 37 (2016).

Mendelson, N. et al. Identifying carbon as the source of visible single-photon emission from hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Mater. 20, 321–328 (2021).

Senkpiel, J. et al. Dynamical Coulomb blockade as a local probe for quantum transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 156803 (2020).

Kaiser, K., Lieske, L.-A., Repp, J. & Gross, L. Charge-state lifetimes of single molecules on few monolayers of NaCl. Nat. Commun. 14, 4988 (2023).

Bobzien, L. et al. Layer-dependent charge-state lifetime of single Se vacancies in WSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 076201 (2025).

Taucer, M. et al. Single-electron dynamics of an atomic silicon quantum dot on the H-Si (100)-(2 × 1) surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 256801 (2014).

Schuler, B. et al. Large spin-orbit splitting of deep in-gap defect states of engineered sulfur vacancies in monolayer WS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 076801 (2019).

Cochrane, K. A. et al. Spin-dependent vibronic response of a carbon radical ion in two-dimensional WS2. Nat. Commun. 12, 7287 (2021).

Stolz, S. et al. Layer-dependent Schottky contact at van der Waals interfaces: V-doped WSe2 on graphene. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 6, 1–5 (2022).

Cocker, T. L., Jelic, V., Hillenbrand, R. & Hegmann, F. A. Nanoscale terahertz scanning probe microscopy. Nat. Photonics 15, 558–569 (2021).

Wallauer, R. et al. Tracing orbital images on ultrafast time scales. Science 371, 1056–1059 (2021).

Cocker, T. L. et al. An ultrafast terahertz scanning tunnelling microscope. Nat. Photonics 7, 620–625 (2013).

Jelic, V. et al. Ultrafast terahertz control of extreme tunnel currents through single atoms on a silicon surface. Nat. Phys. 13, 591–598 (2017).

Liu, S. et al. Nanoscale coherent phonon spectroscopy. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq5682 (2022).

Jelic, V. et al. Terahertz field control of surface topology probed with subatomic resolution. Nat. Photon. 19, 1048–1055 (2025).

Cocker, T. L., Peller, D., Yu, P., Repp, J. & Huber, R. Tracking the ultrafast motion of a single molecule by femtosecond orbital imaging. Nature 539, 263–267 (2016).

Roelcke, C. et al. Ultrafast atomic-scale scanning tunnelling spectroscopy of a single vacancy in a monolayer crystal. Nat. Photonics 18, 595–602 (2024).

Jelic, V. et al. Atomic-scale terahertz time-domain spectroscopy. Nat. Photonics 18, 898–904 (2024).

Müller, M. Imaging surfaces at the space–time limit: New perspectives of time-resolved scanning tunneling microscopy for ultrafast surface science. Prog. Surf. Sci. 99, 100727 (2023).

Bobzien, L. et al. Ultrafast state-selective tunneling in two-dimensional semiconductors with a phase- and amplitude-controlled THz-scanning tunneling microscope. APL Mater. 12, 051110 (2024).

Steurer, W., Gross, L. & Meyer, G. Local thickness determination of thin insulator films via localized states. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 231606 (2014).

Schuler, B. et al. How substitutional point defects in two-dimensional WS 2 induce charge localization, spin–orbit splitting, and strain. ACS Nano 13, 10520–10534 (2019).

Aghajanian, M. et al. Resonant and bound states of charged defects in two-dimensional semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 101, 081201 (2020).

Nazin, G. V., Wu, S. W. & Ho, W. Tunneling rates in electron transport through double-barrier molecular junctions in a scanning tunneling microscope. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 8832–8837 (2005).

Koch, J., Von Oppen, F. & Andreev, A. V. Theory of the Franck–Condon blockade regime. Phys. Rev. B 74, 205438 (2006).

Nie, Z. et al. Ultrafast carrier thermalization and cooling dynamics in few-layer MoS2. ACS Nano 8, 10931–10940 (2014).

Leturcq, R. et al. Franck–Condon blockade in suspended carbon nanotube quantum dots. Nat. Phys. 5, 327–331 (2009).

Doležal, J., Sagwal, A., De Campos Ferreira, R. C. & Švec, M. Single-molecule time-resolved spectroscopy in a tunable STM nanocavity. Nano Lett. 24, 1629–1634 (2024).

Imai-Imada, M. et al. Orbital-resolved visualization of single-molecule photocurrent channels. Nature 603, 829–834 (2022).

Sheng, S. et al. Terahertz spectroscopy of collective charge density wave dynamics at the atomic scale. Nat. Phys. 20, 1603–1608 (2024).

Siday, T. et al. All-optical subcycle microscopy on atomic length scales. Nature 629, 329–334 (2024).

Briggs, N. et al. Realizing 2D materials Via MOCVD. ECS Trans. 75, 725 (2016).

Allerbeck, J. et al. Efficient and continuous carrier-envelope phase control for terahertz lightwave-driven scanning probe microscopy. ACS Photonics 10, 3888–3895 (2023).

Ammerman, S. E., Wei, Y., Everett, N., Jelic, V. & Cocker, T. L. Algorithm for subcycle terahertz scanning tunneling spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 105, 115427 (2022).

Zhebrak, E. D. A method for calculating the Franck–Condon factors in the tomographic probability representation of quantum mechanics. J. Russ. Laser Res. 37, 123—132 (2016).

Zhao, W. et al. Lattice dynamics in mono- and few-layer sheets of WS2 and WSe2. Nanoscale 5, 9677–9683 (2013).

Jeong, T. Y. et al. Coherent lattice vibrations in mono- and few-layer WSe2. ACS Nano 10, 5560–5566 (2016).

Lin, Y.-C. et al. Atomically thin heterostructures based on single-layer tungsten diselenide and graphene. Nano Lett. 14, 6936–6941 (2014).

Krane, N. et al. Mapping the perturbation potential of metallic and dipolar tips in tunneling spectroscopy on MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 100, 035410 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge fruitful discussions with Oliver Gröning and generous support by Roman Fasel. J.A., L.B., E.A. and B.S. appreciate funding by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant agreement No. 948243). S.E.A. and N.K. appreciate financial support from the Werner Siemens Foundation (CarboQuant). Funding for DCF and JAR is through the National Science Foundation EEC-2113864 and ECCS-2202280. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright license to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A., L.B. and B.S. conceived the experiment. J.A., L.B. and B.S. designed and implemented the setup for LW-STM. J.A. and L.B. performed the measurements. J.A., L.B. and N.K. analyzed the data. N.K. and E.A. performed the modeling. D.E.C.F., C.D. and J.A.R. grew the samples. J.A., L.B., N.K. and B.S. wrote the manuscript with feedback from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Alexandr Svetogorov, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Allerbeck, J., Bobzien, L., Krane, N. et al. Ultrafast Coulomb blockade in an atomic-scale quantum dot. Nat Commun 16, 10806 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65834-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65834-5