Abstract

Lithium metal batteries (LMBs) are promising next-generation energy storage solutions, but face challenges in achieving stable performance across wide temperature ranges. While sulfurized polyacrylonitrile (SPAN) offers advantages over traditional sulfur positive electrodes, its compatibility with ether electrolytes remains problematic. This work introduces a temperature-resistant, anion-rich solvation structure using an asymmetric ether solvent, ethyl butyl ether, to enable Li | |SPAN batteries with a wide operational range of 100 °C ( − 40 to 60 °C). The tailored electrolyte fosters a bi-layer interphase on Li negative electrode, which is more effective than the conventional mosaic interphase in suppressing dendrite growth and electrochemically inactive Li accumulation. Concurrently, it builds a dual-layer interphase on the SPAN positive electrode, enabling rapid Li+ transport and shuttle-free sulfur conversion. The resultant Li | |SPAN batteries achieve 72.8% capacity retention after 1000 cycles at 60 °C and 1 C and stably operate at −40 °C and 0.1 C. Validation via an Ah-level pouch cell underscores practical feasibility. This work advances electrolyte design strategies for LMBs resilient to extreme environments, offering critical insights into interfacial engineering for next-generation energy storage systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lithium (Li) metal batteries (LMBs) have recently attracted considerable attention from academic and industrial communities due to their high energy density, which renders them a promising power source for next-generation energy storage systems1,2,3. They are regarded as a pivotal technology for applications requiring compact, lightweight, and high-performance energy storage solutions4, including electric vehicles, electric vertical take-off and landing aircraft, deep-space and deep-sea probes, medical devices, etc. Given the operational versatility required for these devices to function in diverse environments, the development of LMBs with a wide operational temperature range is imperative to satisfy the demands of these varied real-world applications5,6. However, the practical LMBs face significant difficulties in achieving stable electrochemical performance across a broad temperature range. At low temperatures, the predominant challenge lies in the sluggish kinetics, which results in diminished ionic conductivity, compromised rate performance, and accelerated dendrite growth7. Conversely, at elevated temperatures, the intensified electrode-electrolyte side reactions lead to accelerated material consumption and even pose safety hazards8.

In the domain of LMB technologies, Li | |sulfur (S) batteries demonstrate notable advantages, including high theoretical specific energy and cost-effectiveness. However, challenges such as suboptimal utilization of S, rapid capacity decay due to lithium polysulfide (LiPS) shuttle effects, and inadequate temperature adaptability constrain their practical application at present9. Instead, LMBs employing sulfurized polyacrylonitrile (SPAN) positive electrodes have emerged as promising alternatives to Li | |S batteries10. This is because the improved electrical conductivity, superior structural stability, and improved S utilization exhibited by SPAN contribute to enhanced cycling performance and durability, even at low and high temperatures. In carbonate electrolytes, the SPAN can exhibit a high Coulombic efficiency (CE) of >99.9%, as the covalent bond between short-chain S and polyacrylonitrile enables a “solid-solid” reaction conversion mechanism and prevents the formation and shuttle of LiPS11,12. However, the carbonate electrolyte exhibits poor compatibility with the Li metal negative electrode, making it impractical for use in actual Li | |SPAN batteries. In contrast, in the ether electrolytes, which have higher Li-compatibility and are more promising for LMBs, the breaking of the S-S bond in the SPAN backbone and dissolution of LiPS leads to rapid capacity degradation13,14.

In recent years, a variety of ether-based electrolytes have been developed to enhance the reversibility and performance of LMBs, including Li | |S and Li | |SPAN batteries15,16. (Localized) high-concentration electrolytes are the representatives and have demonstrated significant success17,18,19. However, their widespread adoption is limited by low ionic conductivity, high viscosity, and elevated costs. Another promising class is ether-based weakly solvating electrolytes (WSEs)20. By tailoring the structure of ether solvents, such as reducing the oxygen-to-carbon (O/C) ratio and extending alkyl chain lengths, the solvating power of the solvents can be decreased21, allowing the design of anion-rich solvation structures at non-high salt concentrations22. This approach lowers desolvation energy20, promotes the formation of inorganic-rich solid-electrolyte interphase/cathode-electrolyte interphase (SEI/CEI)23, and reduces solvent polarization24, thereby simultaneously improving the electrochemical stability of both positive and negative electrodes. Among these weak ethers, single oxygen linear ethers (SOLEs) have attracted significant attention in recent years because of their reduced melting points (MPs), which ensure favorable viscosity levels and wettability even at low temperatures25,26. Unfortunately, the trade-off for lower MP is usually lower boiling points (BPs), which present challenges for the SOLEs, especially at high temperatures. Consequently, these electrolytes have been primarily applied to boost the low-temperature performance of LMBs, while their performance at high temperatures, such as above 50 °C, remains unsatisfactory, highlighting the need for further optimization. More importantly, the spatial distribution of the chemical compositions in the inorganic-rich SEI/CEI is normally random and shows a mosaic structure, adversely affecting the stability of electrode-electrolyte interfaces during the discharging/charging cycles and thus limiting the overall electrochemical performance of LMBs across a wide temperature range.

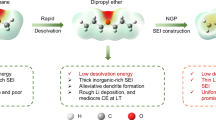

In this study, we establish a temperature-resistant, anion-rich solvation structure with an asymmetric ether, ethyl butyl ether (EBE), at a standard salt concentration of 1 M. This design can not only maintain a reasonable physical property of the electrolyte but also generate a bi-layer CEI/SEI, thereby facilitating the development of Li | |SPAN batteries with a broad operational temperature range. As schematically shown in Fig. 1, on the Li metal genitive electrode side, a thinner SEI is formed, with the outer layer composed of organic species, sulfides, and nitrides, while the inner layer is composed of Li2O. In comparison with the conventional mosaic SEI that forms in the normal ether electrolyte, the designed Li2O-rich bi-layer SEI is more effective in suppressing Li dendrite growth and mitigating the accumulation of electrochemically “dead Li (i.e., Li metal regions which are electronically disconnected from the current collector), which greatly improves the reversibility of the Li metal. On the SPAN positive electrode side, the outermost layer of the CEI is amorphous, while the inner layer is composed of crystalline phases, including Li2S, LiF, and Li3N. Such a configuration of a CEI can not only facilitate Li+ diffusion through the interface but also inhibit the generation and dissolution of LiPS, as corroborated by in situ ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry (UV-VIS), thus achieving a shuttle-free SPAN positive electrode. Consequently, the Li | |SPAN batteries exhibit a broad operational temperature range of 100 °C. Specifically, the battery demonstrates operational stability at sub-zero temperatures of −20 and −40 °C, and more importantly, it exhibits a prolonged lifespan at elevated temperatures of 60 °C. Even after undergoing 1000 cycles, the Li | |SPAN battery demonstrates a capacity retention of 72.8% at 60 °C. To further validate the electrolyte’s practical value, an Ah-level pouch-type cell was assembled and tested. This study offers new insights into the design of high-energy-density and wide-temperature LMBs.

Results

Design, solvation structure, and physical properties of the electrolytes

The conventional ether electrolytes for LMBs are generally developed based on glymes, such as 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME). SOLEs have a lower O/C ratio and solvating power compared to glymes27, and can be used for the design of WSEs. Diethyl ether (DEE), the simplest SOLE, has shown potential for use in WSEs25, but the low BP of 34.6 °C makes it inapplicable at high temperatures. By extending the terminal alkyl chains of DEE to n-propyls and n-butyls, the solvating power can be further reduced, the BP of the solvents can be improved to 90 and 141 °C, respectively, and thus the temperature range of LMBs can be extended to some extent14,26. However, the physical properties of electrolytes, such as ionic conductivity and viscosity, are compromised, which will ultimately lead to poor kinetics and high polarization. The utilization of an asymmetric structure can maintain the weak solvability of the ether to build an anion-rich solvation structure whilst improving the physical properties of the electrolytes. As shown in Fig. 2a, the minimum electrostatic potential (ESPmin) of the DME molecule is −45.11, suggesting a relatively high solvability, while that of the dibutyl ether (DBE) molecule is “improved” to −33.69, indicating a decreased solvability28. When the n-butyl on one side of DBE is reduced to ethyl, the resulting asymmetric ether EBE shows a similar solvability, with the ESPmin kept at a very close value of −33.51. The binding energy of Li+ with the DME, DBE, and EBE is calculated as −3.02, −2.19, and −2.13 eV (Supplementary Fig. 1), respectively, which agrees well with the ESP results.

a ESP images for the DME, DBE, and EBE. MD snapshots for the DME-E b, DBE-E c, and EBE-E d. Atom color legend: C (gray); O (red); H (white); N (blue); F (light green); Li (purple); S (yellow). RDF curves based on the MD simulations for the DME-E e, DBE-E f, and EBE-E g. h Statistics of the ionic species in the three electrolytes. i MSD curves of the electrolytes and the calculated Li+ diffusion coefficients. j Ionic conductivity of the electrolytes measured at a wide temperature range of −40 to 80 °C.

The electrolytes were prepared by dissolving 1 M lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiFSI) in a mixture of linear ether with 1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl-2,2,3,3-tetrafluoropropyl ether (TTE) in a volume ratio of 1:1. Depending on the type of linear ether, the electrolyte can be designated as DME-E, DBE-E, or EBE-E, respectively. TTE reduces the viscosity of electrolytes and is widely used in LMBs to improve cycling stability29. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, all the electrolytes have relatively low viscosity values, with EBE-E being the lowest. For example, at 24 °C, DME-E, DBE-E, and EBE-E have viscosities of 3.22, 2.65, and 2.01 mPa·s, respectively. The solvation structures and properties of the electrolytes were investigated using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with an optimized combination of force fields and charge models, which implicitly account for polarization effects and can describe ionic interactions in solution. The DME-E can be described as Li+[FSI−]0.37[DME]2.14[TTE]0.01 at 25 °C, as indicated in Fig. 2b and the statistics on the solvation cluster in Supplementary Fig. 3a. The radial distribution function (RDF) in Fig. 2e and the coordination number (CN) results in Supplementary Fig. 4a provide further evidence that, within the first solvation sheath of Li+, DME molecules exhibit a predominant role, while the presence frequency of FSI− anions is lower. This solvent-dominated structure is attributed to the high solvating power of DME. In contrast, the solvation structure of DBE-E can be defined as Li+[FSI−]0.98[DBE]0.89[TTE]0.02, in which the number of FSI− anions is increased, accompanied by a decrease in that of the solvent, as shown in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 3b. Furthermore, the RDF (Fig. 2f) and CN results (Supplementary Fig. 4b) substantiate that within the first solvation sheath, the frequency of FSI− anions in the Li+ solvation sheath exceeds that of DBE solvents, thereby indicating the formation of an anion-dominated weak solvation structure. This outcome can be attributed to the diminished solvability of DBE. Interestingly, for the EBE-E, the asymmetric structure exerts minimal influence on the solvation structure compared to DBE-E, which can be described as Li+[FSI−]0.98[EBE]0.92[TTE]0.02, as illustrated in Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 3c. Furthermore, in the first solvation sheath, the presence frequency of FSI− anions in the Li+ solvation is higher than that of solvents (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 4c), due to the low solvability of EBE. The proportion of ionic species in these three electrolytes is further counted based on the MD results. As shown in Fig. 2h, the ratio of solvation-separated ion pairs (SSIP), contact ion pairs (CIP), and aggregate species (AGG) in DME-E are 38.33%, 54.43%, and 7.24%, respectively. In contrast, in both DBE-E and EBE-E, the AGG species occupies the major component with a high ratio of 89.20% and 87.60%, respectively, while the ratio of SSIP in these electrolytes is as low as 2.20% and 1.60%, respectively. The Raman tests of the electrolytes experimentally prove the anion-rich solvation structures in the DBE-E and EBE-E that were predicted by the MD simulations. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 5, the Raman spectra for the S-N-S stretching vibrational mode of the FSI− anion reveal that the portion of AGG-I (one anion binding to two Li+)/AGG-II (one anion binding to more than two Li+) in the DBE-E and EBE-E is as high as 33.82%/56.34% and 36.22%/47.90%, respectively, directly confirming the dominant role of the AGG species in these electrolytes. In contrast, the ratio of AGG is only 16.00% in the DME-E.

Despite the absence of alterations in the solvation structure resulting from the asymmetric structure (compared to symmetric DBE), there is an obvious enhancement in the kinetics of the EBE-E. As illustrated in Fig. 2i, the Li+ diffusion coefficients (\({D}_{{{Li}}^{+}}\)) of the electrolytes were studied by monitoring the mean-squared displacements (MSD) as a function of the elapsed time over a period of 5000 ps. The \({D}_{{{Li}}^{+}}\) for the DME-E is 1.93 × 10−6 cm2 s−1, while that of DBE-E is decreased to 0.52 × 10−6 cm2 s−1. This phenomenon is a common occurrence in WSEs, which can be attributed to the anion-dominated structure and the increased molecular size of the solvents. In the case of EBE-E, the \({D}_{{{Li}}^{+}}\) is 0.95 × 10−6 cm2 s−1, which is nearly twice the value observed for DBE-E. This suggests that the asymmetric structure of EBE enhances the diffusion mobility of Li+ within the electrolyte.

Pulsed-field gradient nuclear magnetic resonance (PFG-NMR) provides indispensable experimental benchmarks for validating MD simulations of electrolytes30. Therefore, we further measured the Li+ diffusion coefficients in the electrolytes using the PFG-NMR method. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, fitting the 7Li PFG-NMR attenuation curves yields diffusion coefficients of 2.73×10−6, 1.28×10−6, and 1.42×10−6 cm−2 s−1 in DME-E, DBE-E, and EBE-E, respectively. These values reproduce both the magnitudes and the trends observed in the MD simulations. The combined validation from PFG-NMR and Raman spectroscopy confirms that the applied force fields and charge models are scientifically sound and reliable. It was noted that residual discrepancies between MD and PFG-NMR diffusivities remain, consistent with previous reports31,32,33. These differences can be rationalized by two factors: (i) timescale and length-scale mismatch—PFG-NMR probes effective diffusivities over milliseconds and macroscopic distances, whereas MD captures nanosecond dynamics in nanometer-scale boxes; and (ii) species sensitivity—PFG-NMR likely detects the motion of solvated clusters (CIP and AGG) in addition to free Li+, which may lead to apparent diffusivities higher than those obtained from single-ion MSD tracking in MD.

It is significant that across a broad temperature range spanning from −40 to 80 °C, the DME-E and DBE-E exhibit the maximum and minimum values of ionic conductivity, respectively, while the EBE-E delivers a moderate value (Fig. 2j). For example, the ionic conductivity of DME-E, DBE-E, and EBE-E at 20 °C is 6.14, 0.33, and 0.88 mS cm−1, respectively. This finding provides experimental evidence in support of the enhanced Li+ diffusion kinetics observed in the EBE-E as compared to the DBE-E. The restricted kinetics in the DBE-E will lead to elevated electrochemical polarization, thereby reducing the specific capacity and compromising the lifespan and low-temperature performance of LMBs (see subsequent sessions for further details). Consequently, the DME-E will be utilized as the primary reference electrolyte. Meanwhile, the DBE-E will only be employed for comparing electrochemical performance under ether solvents with different terminal alkyl groups.

The solvation structure of the electrolytes is examined by using NMR spectroscopy. As demonstrated in Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 7, the 13C NMR spectra show that both the methoxy carbon (Ca) and ethane α-carbon (Cb) of DME have an upfield chemical shift after adding LiFSI, indicating a shielding and an increase in electron density of these carbon nuclei. The latter exhibits a significantly higher shift (1.41 ppm) compared to the former (0.47 ppm). This is consistent with the five-membered ring chelation structure of the DME-Li+ coordination complex (Supplementary Fig. 1), in which the ethane α-carbon atoms are closer to the Li+ coordination sites. Conversely, the 13C NMR spectra of EBE and EBE-E in Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 8 present a contrasting phenomenon. The ethyl terminal carbon (Ca) and n-butyl β-carbon (Cd) demonstrate the most upfield chemical shift, corresponding to 1.46 and 1.31 ppm, respectively. This is because EBE exhibits a solo coordination site, and these two carbons exhibit the strongest interaction with Li+. In the 7Li NMR spectra in Fig. 3c, the peak of EBE-E has a downfield shift compared to that of DME-E, indicating a decreased electron density around Li+34. The shift can be attributed to the weaker binding effects of the EBE compared to DME, resulting in a reduced solvent present in the Li+ solvation sheath. Additionally, a downfield shift is observed in the 19F NMR spectra for the EBE-E peak compared to the DME-E peak (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 9), which can be attributed to the de-shielding effect resulting from stronger Li+-FSI− interactions in the EBE-E35. This result also corroborates the predominance of a large ratio of AGG species in the EBE-E. The microscopic structure of the electrolytes is also examined by a wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) diffractometer (Fig. 3e). There is an obvious peak located at a position of Q = 1.47 and 1.39 Å−1 for the DME-E and EBE-E, respectively, which are ascribed to the distance between the neighboring atoms of different anions36,37. The lower value of Q reflects the more compact solvation structure of the EBE-E, in which the distance of the anions is shorter. Another predominant peak for the solvation structure in the EBE-E is situated at Q = 0.46 Å−1, which is assigned to the AGG-dominated large clusters38. In contrast, in the DME-E, the broad shoulder located at Q = 1.06 Å−1 could be attributable to the solvent-rich solvation clusters, which have a smaller size, while the tiny peak at Q = 0.53 Å−1 could be responsible for the small ratio of AGG in the DME-E. These experimental observations are consistent with the characteristic behavior of WSEs and are in close agreement with the MD simulation results. The solvent-dominated and anion-dominated solvation structures of the DME-E and EBE-E are, therefore, accordingly illustrated in Fig. 3h, i.

To study the influence of temperature on the solvation structure of EBE-E, MD simulations were also performed at low and high temperatures. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 10a, at −20 °C, the electrolyte structure can be represented as Li+[FSI−]0.99[EBE]0.70[TTE]0.02, close to that at 25 °C. The RDF and CN curves in Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 10b clearly demonstrate that in the solvation sheath, the presence frequency of FSI− is higher than that of the EBE solvent. The ratio of AGG species is also kept at a high level of 91.40%. When the temperature is enhanced to 60 °C, the electrolyte doesn’t exhibit a significant change in solvation structure, which is identified as Li+[FSI−]0.98[EBE]1.07[TTE]0.02, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 11a. The anion-rich solvation structure is maintained well, as verified in the RDF curves in Fig. 3g and the CN curves in Supplementary Fig. 11b. This is also proved by the high AGG and CIP ratio of 78.60% and 19.40%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 11c). This temperature-resistant solvation structure is illustrated in Fig. 3i, which can help to construct robust electrode-electrolyte interfaces, thus benefiting the improvement of LMBs over a wide temperature range.

Improving the reversibility of Li metal negative electrodes at a wide temperature range

The lifetime of LMBs is highly dependent on the CE of Li metal negative electrodes, and the morphology of Li deposition can determine the reversibility of Li plating/stripping cycles. In general, granular or lumpy Li contributes to high reversibility, while dendritic or mossy Li leads to poor reversibility or even safety hazards39. Thus, the Li deposited in the DME-E and EBE-E at a low temperature of −20 °C, a room temperature of 25 °C, and a high temperature of 60 °C was observed with scanning electron microscopy (SEM). As demonstrated in Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 12, at a temperature of −20 °C, Li predominantly deposits with non-uniform morphology under an applied current density of 0.5 mA cm−2 and an area capacity of 0.5 mAh cm−2 under the DME-E, exhibiting the presence of conspicuously tortuous dendritic Li. When the temperature is elevated to 25 and 60 °C, the size of Li increases because of the boosted deposition kinetics, yet Li dendrites persist, as illustrated in Figs. 4c and 4e, and Supplementary Figs. 14 and 16. In contrast, under the same electrochemical conditions, the deposited Li in EBE-E exhibits a granular morphology at all temperatures, as demonstrated in Fig. 4b, d, f, and Supplementary Figs. 12, 14, and 16. With an increase in temperature, the size of Li particles also increases, and the deposited Li becomes denser. Even when the deposition time is extended to 10 h and the area capacity reaches 5 mAh cm−2, the Li plated in EBE-E is denser and more compact than that in DME-E with a larger size at all temperatures, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 13, 15, and 17.

SEM images of the Li deposited at −20 a, 25 c, and 60 °C e in the DME-E. SEM images of the Li deposited at −20 °C b, 25 °C d, and 60 °C f in the EBE-E. The applied current density is 0.5 mA cm−2, and the area capacity is 0.5 mAh cm−2 in a–f. g Li | |Cu cell tests at −20 °C with a current density of 0.2 mA cm−2 and an area capacity of 1 mAh cm−2. h Li | |Cu cell tests at 25 °C with a current density of 1 mA cm−2 and an area capacity of 1 mAh cm−2. i Li | |Cu cell tests at 60 °C with a current density of 1 mA cm−2 and an area capacity of 1 mAh cm−2, and (j) the corresponding discharging-charging curves. SEM images of the Li@DME-E k and Li@EBE-E l after 75 cycles in Li | |Cu cells at a current density of 1 mA cm−2 and an aera capacity of 1 mAh cm−2 at 25 °C. Scale bars: 5 µm a–f and 50 µm k, l.

The reversibility of the Li metal negative electrode was evaluated through the measurement of the CE of Li | |Cu cells. At a temperature of −25 °C, the Li | |Cu cell with DME-E delivers an average of 97.10% and a lifespan of approximately 75 cycles. The value of CE fluctuates with cycling, exhibiting a high standard deviation (SD) of 7.14%, as depicted in Fig. 4g. In comparison, the Li | |Cu cell with EBE-E exhibits a significantly higher lifespan, exceeding 100 cycles, while maintaining an average CE of 98.91% and a low SD of 0.23%. At 25 °C, the Li | |Cu cell with DME-E can work for more than 100 cycles, with a CE of 98.64% and a reduced SD of 1.31%, while that with EBE-E can work for over 160 cycles, and the CE is improved to 99.17% and the SD is as low as 0.12%, as shown in Fig. 4h. At an elevated temperature of 60 °C, the Li | |Cu cell with EBE-E exhibits stable performance over 200 cycles, achieving a high CE of 99.22% and a low SD of 0.17% (see Fig. 4i, j). This performance is better than that of the cell with DME-E, which only operates for 150 cycles, with a CE of 98.87% and an SD of 1.89%. The high SD in the DME-E is potentially attributable to the unstable electrode-electrolyte interfaces and the subsequent soft short circuit40,41, as demonstrated in the discharging-charging curves depicted in Supplementary Figs. 18-20. The diminished SD in the EBE-E substantiates the enhanced interfacial stability during Li plating/stripping cycles. The heightened CE and extended lifespan testify to the capability of the EBE-E to enhance the reversibility of the Li metal electrode. The morphology of the cycled Li metal electrodes was examined to further validate the results. As shown in the top-view SEM images in Supplementary Fig. 21, the Li cycled in DME-E (denoted as Li@DME-E) has a cluttered and uneven surface, with granular Li embedded irregularly in the substrate of electrochemically “dead” Li (i.e., Li metal regions which are electronically disconnected from the current collector). The side-view SEM image in Fig. 4k reveals that the “dead” Li layer is mostly exfoliated from the Li electrode, leaving a distinct gap, and the thickness of the layer ranges from 29 to 48 µm. In strong contrast, the Li cycled in EBE-E (denoted as Li@EBE-E) has a flatter and more uniform surface (Supplementary Fig. 21), which is covered by dense, lumpy Li. From the side-view SEM image in Fig. 4l, a layer of “activated” Li is tightly adhered to the substrate of the Li electrode, whose thickness is much lower, ranging from 12 to 15 nm.

In the case of the Li | |Cu cells with the DBE-E, which also possesses a solvation-rich structure, the average CE are 98.54%, 98.47%, and 99.09%, respectively, at temperatures of −20, 25, and 60 °C, and the corresponding SDs are 0.24%, 0.69%, and 0.16%, respectively. These values approach those of the EBE-E, as demonstrated in Supplementary Figs. 18-20. However, the shortest lifespan and the largest potential hysteresis reveal that the poor physical properties of the DBE-E greatly compromise the electrochemical performance.

The findings of the SEM observation and Li | |Cu cell tests demonstrate that the high ionic transport properties in DME-E or the anion-rich solvation structure in DBE-E alone cannot ensure dendrite-free uniform deposition and high reversibility of the Li metal negative electrode. EBE-E features both decent ionic transport properties and the capacity to establish anion-derived electrode-electrolyte interfaces (see subsequent discussions), thereby facilitating expeditious interfacial kinetics and high electrochemical performance for the Li metal negative electrodes.

Extending the lifespan of wide-temperature Li | |SPAN batteries

The potential of the developed electrolytes for utilization in wide-temperature Li | |SPAN batteries was assessed by evaluating the cycling performance. SEM analysis shows that SPAN material exhibits a particle-like morphology with sizes ranging from 100 to 400 nm, and XRD and Raman spectra indicate an amorphous carbon structure with high defect density, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 22. A moderate condition was initially applied to these batteries, characterized by a low positive electrode mass loading of approximately 1 mg cm−2, an infinite Li foil of 500 µm, and a flooded electrolyte of 40 µL per battery. The low-temperature performance of the batteries was evaluated at −20 °C with a specific current rate of 0.2 C (1 C = 1650 mA g−1 for all Li | |SPAN batteries). As demonstrated in Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 23, the battery displays an initial discharging capacity of 350 mAh g−1 (based on the mass of S, similarly hereinafter) in DME-E, accompanied by a low CE of 39.96%, and the capacity rapidly diminishes to below 250 mAh g−1 after 110 cycles. In comparison, the battery with EBE-E exhibits an initial discharging capacity of 681 mAh g−1, with a much higher CE of 68.52%. After 500 cycles, the capacity remains above 595 mAh g−1, indicating an enhanced retention of 87.3%. Even when the testing temperature was down to −40 °C, the EBE-E can support the stable cycling of the Li | |SPAN battery. As shown in Fig. 5b, the battery still exhibits a discharging capacity of 445 mAh g−1 after 200 cycles with a favorable retention of ~69% at a specific current rate of 0.1 C. Then the batteries were subsequently assessed at a room temperature of 25 °C, which were activated at a specific current rate of 0.2 C for two cycles, followed by cycling at a rate of 1 C. As demonstrated in Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 24, the Li | |SPAN batteries exhibit comparable initial discharging capacity in the DME-E and EBE-E after activation, at 1059 and 995 mAh g−1, respectively. However, in the DME-E, the capacity rapidly declines to below 600 mAh g−1 after 70 cycles. In contrast, the battery in EBE-E demonstrates a capacity retention of 73.9% after 450 cycles, indicating a sustained capacity of 736 mAh g−1. Furthermore, the average CE for the initial 100 cycles is 99.21% in the DME-E, which is evidently lower than that of 99.86% in the EBE-E. The overall average CE in the EBE-E can reach a high level of 99.93%. The accelerated capacity decay and diminished CE in DME-E at both low and ambient temperatures can be ascribed to the generation and shuttle effects of LiPS in the electrolytes based on normal ethers15,42. The boosted cycling performance in the EBE-E reveals the capability of the electrolyte to address these problems inside the Li | |SPAN batteries. The high-temperature performance of the batteries has been evaluated at 60 °C. The cycling performance of the batteries exhibits significant enhancement in comparison to their performance at low and room temperatures. This can be attributed to the facilitation of the decomposition of anions at elevated temperatures, which results in the generation of increased inorganic SEI/CEI components. These components have been observed to mitigate electrode-electrolyte interactions and suppress the consumption of active materials within the batteries. As demonstrated in Fig. 5c, d, and Supplementary Fig. 25, the battery with DME-E exhibited stable performance during the initial 520 cycles, with a capacity retention of 72.7% (based on the capacity after activation), followed by a rapid degradation. Importantly, the battery with EBE-E exhibits a high capacity of 853 mAh g−1 even after 1000 cycles, with a capacity retention of 72.8%. Such stable cycling performance at a wide temperature range (especially at high temperatures) achieved in the EBE-E is comparable to that in the state-of-the-art ether-based electrolytes, particularly the SOLE-based WSEs, as summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

To investigate the Li⁺ diffusion and charge transfer processes in Li | |SPAN batteries under low-temperature conditions, a three-electrode configuration was employed to separately analyze the interfacial properties of the Li negative electrode and SPAN positive electrode. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 26 and 27 and Supplementary Table. 2-6, the impedance of both the Li and SPAN increases significantly at low temperatures, with the SPAN exhibiting a more pronounced temperature-dependent impedance rise, making it the key limiting factor in Li | |SPAN battery performance. At reduced temperatures, both Li⁺ migration through the CEI and interfacial charge transfer become markedly sluggish. Although the DME-E demonstrates improved ionic transport properties and lower charge transfer resistance of SEI compared to EBE-E, the inferior CEI properties in DME-E severely hinder electrochemical performance at low temperatures. Overall, the EBE-E electrolyte exhibits the most favorable low-temperature performance among the investigated systems, offering the optimal balance between ion conductivity and interfacial stability.

Concerning the Li | |SPAN batteries with DBE-E, across the wide operation temperature range of −20 to 60 °C, the discharging capacity and lifespan are remarkably decreased. Concurrently, the potential polarization during the discharging-charging processes is greatly increased, as displayed in Supplementary Figs. 23-25. This can be attributed to the sluggish kinetics resulting from the low ionic conductivity.

In order to further show the advantage of the EBE-E, the mass loading of the SPAN is augmented to 1.8 mg cm−2 (about 2.1 mAh cm−2), together with the reduction of the thickness of the Li to 50 µm. The capacity ratio of the negative electrode to the positive electrode (n/p ratio) is approximately 5. As shown in Fig. 5e, at room temperature and a current rate of 0.2 C, the Li | |SPAN battery can deliver a high capacity retention of ~100%. More importantly, an Ah-level pouch-type Li | |SPAN is assembled and tested to demonstrate the potential of practical application of the EBE-E, as shown in Fig. 5f. As summarized in Supplementary Fig. 28, the cell is manufactured by using the prismatic winding process; the SPAN electrode is double-sided coated with an area capacity of 5 mAh cm−2, the n/p ratio is controlled at ~2, and the electrolyte amount is limited to ~4 µL mAh−1. As shown in Fig. 5f, and Supplementary Figs. 28 and 29, at a current of 150 mA, the cell delivers a discharging capacity of 1041 mAh, with a specific energy of 170.91 Wh Kg−1. After 50 cycles, the cell can still exhibit a discharging capacity of 680 mAh.

Chemical composition and structure of the SEI

The surface chemical properties are pivotal in determining the electrochemical performance of Li metal negative electrodes. Therefore, the surface chemistry of the Li metal electrodes cycled in the Li | |SPAN batteries was investigated with X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). In the Li 1 s XPS profiles in Supplementary Fig. 30, the intensity of the Li0 peak, indicative of metallic Li, is observed to be lower in the Li@EBE-E than the Li@DME-E. This observation suggests that the Li substrate underlying the SEI is more readily discernible in the Li@EBE-E. Consequently, it can be deduced that the SEI formed in the EBE-E is thinner than that in the DME-E. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 31, the C 1 s XPS depth profiles clearly present that the peak intensity of C-containing species, which are primarily derived from the decomposition of solvents on the Li surface, is lower on Li@EBE-E than on Li@DME-E. Furthermore, the intensity of the peaks that belong to Li2CO3 and ROCOOLi (R is short-chain alkyl groups) on the Li@EBE-E is also lower than that on Li@DME-E, as depicted in the Li 1 s XPS depth profiles in Supplementary Fig. 30 and the O 1 s XPS depth profiles in Fig. 6a. These results demonstrate that the reduction stability of the ether solvents is improved in the EBE-E43. A significant observation is the predominance of Li2CO3 and ROCOOLi within the SEI of the Li@DME-E, as demonstrated by the Li 1 s XPS depth profiles. The intensity of the latter is consistently the most pronounced, extending from the surface to the depth of sputtering for 300 s. In stark contrast, within the SEI of Li@EBE-E, Li2O consistently exhibits a dominant role, displaying the highest intensity in all the sputtered durations (see Supplementary Fig. 30). The O 1 s XPS profiles depicted in Fig. 6a further substantiate the elevated Li2O content observed within the SEI of Li@EBE compared to that of Li@DME-E. These comparisons confirm that the SEI formed in the DME-E is organic-rich, but the SEI generated in the EBE-E is inorganic-rich. Another salient observation is that the LiF content in the SEI of Li@DME-Li is distinctly higher than that in the Li@EBE-E, as shown in Fig. 6b. Conventional wisdom holds that LiF is the optimal SEI component, and an increase in LiF within the SEI is associated with improved reversibility of the Li metal electrodes44. However, our results contradict this conclusion. In the SEI generated in EBE-E, more Li2O but less LiF is formed, while the Li | |Cu cells deliver improved CE in EBE-E, regardless of temperature. This proves that Li2O is a more effective SEI component in improving the reversibility of the Li metal electrode compared to LiF. Some recent studies also confirm that Li2O is more capable of conducting Li+, regulating the Li deposition behavior, and suppressing the Li dendrite growth, thus alleviating the active loss during the Li plating/stripping cycles45,46. Given the identical salt concentration and the same amount of TTE in the DME-E and EBE-E, it can be inferred that the formation of LiF should be primarily attributed to the decomposition of TTE on the Li surface, while the formation of Li2O can be principally ascribed to the decomposition of anions. Additionally, the intensity of LixS (x = 1,2) loacted at 160.5 eV, which also has higher ionic conductivity than LiF, is higher in the SEI of Li@EBE-E (see Supplementary Fig. 32), suggesting the promoted decomposition of anions.

O 1 s a and F 1 s b XPS depth profiles, and TOF-SIMS depth profiles c of the cycled Li metal negative electrodes. TOF-SIMS surface mapping of the representative secondary ions of Li@DME-E d and Li@EBE-E e. TOF-SIMS 3D rendering images of the representative secondary ions of Li@DME-E f and Li@EBE-E g. The Li metal negative electrodes were cycled in Li | |SPAN batteries for 200 cycles at 1 C and 25 °C.

The surface chemical properties of the cycled Li electrodes were examined using time-of-flight secondary-ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS). Figure 6c (upper panel is Li@EBE-E and lower panel is Li@DME-E) shows the TOF-SIMS depth profiles, which reveal that the intensity of the 7Li− secondary ion, indicative of Li metal, gradually increases in the Li@DME-E. However, in the Li@EBE-E, the intensity increases rapidly at 60 s and subsequently stabilizes. Furthermore, the TOF-SIMS surface mapping analysis (see Fig. 6d, e) reveals a higher concentration of 7Li− in the Li@EBE-E, thereby substantiating the inference that the SEI formed in the EBE-E is thinner than that in the DME-E. The TOF-SIMS depth profiles further demonstrate that the intensity of the CO3− secondary ion, which is indicative of the organic byproducts resulting from electrolyte decomposition, remains constant with sputtering for 300 s in the Li@DME-E. However, it undergoes a rapid decline within sputtering for 60 s in the Li@EBE-E. Furthermore, in the TOF-SIMS surface mapping analysis, the content of the CO3− secondary ion is lower in the Li@EBE-E compared to that in the Li@DME-E, which also proves that the reduction decomposition of the ethers on the Li surface is mitigated. Specifically, the intensity and content of LiO−, which delegates Li2O in the SEI, is higher in the Li@EBE-E, while the intensity and content of LiF2−, which delegates LiF in the SEI, is lower in the Li@EBE-E. These observations are in agreement with the XPS results. Furthermore, the depth profiles in Fig. 6c reveal that the intensity of the ions in the Li@DME-E does not exhibit a discernible change with sputtering over a duration of 300 s. However, a significant change is observed in the Li@EBE-E within the initial 60 s of sputtering, indicating a chemical composition change in the SEI. This initial sputtering process can be subdivided into two distinct regions: the first region encompasses the interval from 0 to approximately 20 s, while the second region extends from approximately 20 to approximately 60 s. TOF-SIMS three-dimensional (3D) rendering for the representative second ions was performed to provide more information about the 3D structure of the SEI on Li metal electrodes. As visually demonstrated in Fig. 6f and Supplementary Fig. 33, the SEI on the Li@DME-E shows a spatially mosaic structure. The organic species (mainly represented by CO3−, LiCO3−, and CH2− ions) and inorganic species, including LiF (characterized by LiF2− and LiF− ions), Li2O (characterized by LiO− and Li2O2− ions), S-containing components (characterized by Li2S− and SO3− ions), and nitrates (characterized by NO2− ion), are homogeneously mixed, without layered structure. In striking contrast, the SEI on the Li@EBE delivers an evident inorganic-rich bi-layer structure, as visually shown in Fig. 6g and Supplementary Fig. 34. The outer layer (close to the electrolyte) is composed of LiF, S-containing components, and nitrates, with a thin layer of organic species, while the inner layer (close to Li metal) is mainly composed of Li2O, mixed with a little LiF.

The comparisons in the chemical composition and 3D structure of the SEI on the cycled Li electrodes confirm that the difference in the solvation structure has an indubitable impact on the reduction decomposition behavior of the electrolytes. The organic-rich homogenous SEI of the Li@DME-E demonstrates the solvents in the DME-E precedence in terms of decomposition, while the contribution to the SEI composition from the anion decomposition is the secondary factor. In comparison, in the EBE-E with anion-rich solvation structure, the FSI− anions in the Li+ solvation sheaths not only can lower the polarization of the solvent molecules, thus decreasing their reduction potential, but can also decompose to yield favorable SEI components, particularly Li2O. The Li2O component is closer to Li metal than the organic components, confirming the priority in the decomposition of the anions compared to the solvents in the EBE-E. The inorganic components can facilitate the ion diffusion speed through the SEI because of their high ionic conductivity, which can promote the growth of Li to a chunky morphology. In addition, their low electric conductivity can impede electron tunneling within the SEI, thereby hindering the progression of solvents toward further decomposition47,48,49. The organic outermost layer can buffer the mechanical stress at the interface during the Li plating/stripping cycles50,51. Therefore, the formation of Li dendrite and “dead” Li (i.e., Li metal regions which are electronically disconnected from the current collector) can be suppressed, and Li metal electrodes can exhibit enhanced reversibility in the EBE-E at a wide temperature range.

Chemical composition and structure of the CEI

The electrochemical stability of the SPAN positive electrode is significantly influenced by the surface chemical properties of the CEI. The chemical composition and structure of the CEI of the cycled SPAN were analyzed using XPS and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The CEI on the surface of the SPAN cycled in the DME-E (denoted as SPAN@DME-E) is amorphous without apparent crystalline phases, as evidenced by the TEM images in Fig. 7a, b, and the thickness of the CEI ranges from 17 to 25 nm. The CEI on the surface of the SPAN cycled in the EBE-E (denoted as SPAN@EBE-E) exhibits a comparable thickness of 18-24 nm, yet a discernible bi-layer structure is identifiable, as illustrated in Fig. 7c, d. The outer side of the CEI (in proximity to the electrolyte) is amorphous, suggesting an organic-rich composition, with a thickness ranging from 4 to 10 nm. In contrast, the inner side (in proximity to the SPAN) of the CEI is predominantly crystalline, with a thickness of 9 to 14 nm. The fast Fourier transform (FFT) patterns in Fig. 7e associated with Fig. 7d prove the existence of crystalline Li3N, Li2S, and LiF on the inner side. The high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images in Fig. 7e substantiate that the observed lattice fringes in the selected regions can be indexed as the (002) plane of LiF, the (200) plane of Li2S, and the (100), (101), and (002) planes of Li3N. The energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping images in Fig. 7f visually verify that an N-, S-, and F-rich CEI “shell” is coated on the SPAN “core”. In contrast, the CEI on the SPAN@DME-E does not demonstrate the enrichment of N, F, and S elements, as evidenced by the EDS mapping images depicted in Supplementary Fig. 36. The C 1 s XPS spectra in Supplementary Fig. 37a validate that the C-containing species in the SEI of the SPAN@DME-E is higher than those of the SPAN@EBE-E. This proves that the oxidation decomposition of the ether solvents is suppressed in the EBE-E, leading to the reduced formation of amorphous organic phases in the CEI. The higher intensity of the F 1 s (see Supplementary Fig. 37b) and N 1 s (see Supplementary Fig. 37c) spectra verifies that more inorganic CEI components are formed in the CEI of SPAN@EBE-E. The observed discrepancies in the composition and structure of the CEI can be ascribed to the divergent solvation structures of the electrolytes. The solvent-dominated solvation structure of DME-E results in an organic-rich amorphous CEI, whereas the anion-dominated solvation structure yields an inorganic-rich bi-layer CEI. As is the observation in the bi-layer SEI on the Li, the inorganic crystalline phases are in close proximity to the SPAN. This suggests that the anions take precedence over solvents in the oxidation decomposition process. The anion-derived inorganic CEI components, including Li3N, Li2S, and LiF, in conjunction with the amorphous matrix, have the capacity to establish a robust interphase, thereby facilitating ion diffusion and suppressing the potential shuttle effect of the LiPS22,52,53.

Low-magnification TEM image of SPAN@DME-E a and SPAN@EBE-E c. High-magnification TEM image of SPAN@DME-E b and SPAN@EBE-E d. e FFT pattern of the SPAN@EBE-E and the high-resolution TEM images of representative regions in the CEI. f EDS elemental mapping of the SPAN@EBE-E. Scale bars: 10 nm a, c, 5 nm b, d, 2 nm e, and 50 nm f. The SPAN positive electrodes were cycled in Li | |SPAN batteries for 200 cycles at 1 C and 25 °C.

To further understand the mechanism behind the formation of the bilayer-structured electrode-electrolyte interfaces, we investigated the structure of the SEI and CEI formed in the DBE-E. As shown in the TOF-SIMS 3D rendering images in Supplementary Fig. S35, the SEI on the Li@DBE-E exhibits a typical mosaic structure without distinct layered characteristics. Additionally, TEM analysis in Supplementary Fig. S38 reveals that the CEI on the SPAN@DBE-E is amorphous in nature. These observations indicate that both the SEI and CEI formed in DBE-E are similar to those seen in DME-E. These findings demonstrate that the anion-rich solvation structure of DBE-E alone is insufficient to regulate the formation of the distinctive bilayer SEI/CEI. Instead, it highlights that the asymmetric molecular structure of EBE plays the decisive role in engineering the bilayer interphases.

Suppressing the Dissolution and Shuttle Effect of LiPS

The dissolution of LiPS plays a major role in the degradation of electrochemical performance in Li | |S and Li | |SPAN batteries. The binding energy between LiPS and solvent molecules is calculated to evaluate the interactions between them. Li2S6 is used as a representative of the LiPS. As shown in Fig. 8a, b, the binding energy of the DME-Li2S6 and EBE-Li2S6 complexes is calculated as −1.62 and −1.12 eV, respectively, suggesting a lower interaction of EBE to LiPS. Furthermore, after adding 2 mM Li2S6, the DME solvent shows a uniform brown color without any sediments, indicating that the Li2S6 is completely dissolved (Fig. 8c). In sharp contrast, the EBE solvent with identical Li2S6 is almost transparent with visible sediments on the bottom, experimentally verifying the capability of EBE in suppressing the dissolution of LiPS. The dissolution of LiPS in the working Li | |SPAN batteries was monitored with in situ UV-VIS measurement. The assembly of the Li | |SPAN batteries, which consist of a Li foil, a separator film, and a SPAN positive electrode foil, was facilitated by a two-electrode quartz cell, as illustrated in the inset of Fig. 8d. The configuration of the entire in situ UV-VIS measurement is illustrated in the inset of Fig. 8e. The cells with the DME-E and EBE-E were subjected to two discharging-charging cycles. As demonstrated in the UV-VIS spectra depicted in Fig. 8d, the electrochemical process leads to the detection of distinct peaks belonging to LiPS in the DME-E. The peaks at ~242 and 290 nm can be assigned to the formation and dissolution of elemental sulfur (S8) in the DME-E, and that at 315 nm can be assigned to S62−/S42−54, which is due to the irreversible “solid-liquid” sulfur conversion in the DME-based electrolyte55. Upon the discharging-charging cycles, the intensity of these peaks increases, confirming the accumulation of these S species in the electrolyte. In strong contrast, in the cell with EBE-E at identical conditions, the intensity of these peaks is much lower (Fig. 8e), confirming that the dissolution of LiPS is greatly suppressed. This should be attributed to the robust inorganic-rich CEI formed on the SPAN@EBE-E as well as the reduced LiPS binding energy with the solvent. The results prove that the EBE-E can enable a “solid-solid” S conversion, thereby constructing a shuttle-free Li | |SPAN battery. All these can alleviate the active S loss and prolong the lifespan of LMBs.

The binding energy of the DME-Li2S6 a and EBE-Li2S6 b complexes. Atom color legend: C (gray); O (red); H (white); Li (purple); S (yellow). c Optical photo of the solvents after adding 2 mM Li2S6. In situ UV-VIS spectra of the Li | |SPAN cell with DME-E d and EBE-E e. The inset is the optical image of the two-electrode cell d and the configuration of the in situ UV-VIS measurements e. The cells are operated in cyclic voltammetry scans in a potential window of 1-2.8 V at 25 °C, with a scanning rate of 0.1 mV s−1.

Discussion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates a rational electrolyte design strategy to enable high-performance Li | |SPAN batteries with good operational temperature resilience. By leveraging the asymmetric structure of EBE, a temperature-resistant, anion-dominated solvation structure is constructed, balancing favorable physical properties and electrochemical stability. This configuration promotes preferential anion decomposition over solvent degradation at both positive and negative electrodes, fostering stable interphases. On the Li side, a Li2O-rich bilayer SEI more effectively regulates Li deposition, suppresses dendrite growth, and mitigates “dead Li (i.e., Li metal regions that are electronically disconnected from the current collector) accumulation compared to conventional organic-rich mosaic SEIs. Concurrently, an inorganic-rich bilayer CEI on the SPAN enables shuttle-free S conversion and rapid Li⁺ transport. These synergistic effects enhance Li negative electrode reversibility across temperatures, as evidenced by the improved CE and the reduced SD. The Li | |SPAN batteries deliver an extended lifespan across a wide temperature range of 100 °C. The Li | |SPAN battery can even stably work for 1000 cycles at 60 °C, which is comparable to that in state-of-the-art ether-based WSEs. Practical viability is further demonstrated via an Ah-level pouch cell operating under harsh conditions. This work underscores the pivotal role of solvation engineering in harmonizing interfacial stability and reaction kinetics for extreme-conditioned batteries. The strategy offers a scalable framework for designing wide-temperature electrolytes, which could be extended to other alkali metal/ion battery systems, thereby advancing energy storage solutions for demanding applications.

Methods

Materials

The DME ( > 99.9%, Dodo Chem), DBE (99%, TCI), and EBE ( > 99%, TCI) solvents were dried on 0.3-0.5 mm diameter lithiated molecular sieves for at least 48 h prior to use. The LiFSI salt (99.9%) was vacuum-dried at 50 °C for 2 h prior to use. S power (99.998%, Sigma-Aldrich), polyacrylonitrile (PAN) (average Mv 150,000, Sigma-Aldrich), styrene butadiene rubber (SBR) (ZEON, BM-451B, 40%), and sodium carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) (MS-Daicel, CMC1200) were used without pretreatment. Lithium foils ( > 99.9%, China Energy Lithium Co., Ltd.) were used as received. CR2032-type coin cell cases, made of 316 stainless steel and equipped with an O-ring and a 1 mm spacer, were purchased from Xiamen Tmax Battery Equipment Co., Ltd. Copper foil ( > 99.8% purity, 25 μm thickness, MTI Corporation) was cleaned by sequential washing with boiling water and dilute HCl. Carbon-coated aluminum foil (16 μm thickness, Dodo Chem) was used as received. The Li | |SPAN pouch cell was fabricated by Extreme Materials Technology (Zhuhai) Co., Ltd., and the cell parameters and testing conditions were summarized in Supplementary Fig. 28.

Preparation of SPAN positive electrode

S and PAN powders were mixed in a mass ratio of 20:5.3 by mixing with ball milling at 360 rpm for 8 h. After that, the mixture was heat-treated at 300 °C for 150 min under Ar flow, with a heating rate of 2 °C min−1. The obtained SPAN product was further ground in an agate mortar. According to the results of elemental analysis, the S content in the obtained SPAN is 48%. To prepare the positive electrode, SPAN powder, SBR (binder), CMC (binder), and Super P conductive carbon were mixed in a weight ratio of 90:2.5:2.5:5 by magnetic stirring for 12 h in deionized water with a solvent-to-solid ratio of ~3.67. Then, the obtained slurry was tape-coated on carbon-coated Al foil on a single side, followed by drying at 60 °C overnight in a fan oven. The obtained electrode sheets were punched into discs with a diameter of 12 mm (corresponding to an area of 1.13 cm2) for subsequent use. The mass loadings (based on S) were approximately 1.0 and 1.8 mg cm−2 (as specified in the respective tests), with corresponding thicknesses of approximately 60 and 100 μm, respectively.

Electrochemical tests

The coin-type Li | |Cu and Li | |SPAN batteries were assembled in an Ar-filled glovebox with O2 and H2O levels <0.1 ppm and were sealed by a manual battery hydraulic sealer sealing machine with a pressure of 750 psi. The Li foil used in these batteries had a thickness of 500 μm. A single layer of Celgard 2325 membrane was employed as the separator, and 40 μL of electrolyte was added to each battery. These batteries were tested with LAND CT3002 battery testers. For precise temperature control during the tests conducted at −40, −20, 25, and 60 °C, all batteries were maintained in a climatic chamber (MTI, MSK-TE906-30L). The Li | |Cu cells were pre-cycled with a low current of 50 μA for 5 cycles. The potential range of the Li | |Cu cells is 0-1 V. The SD of the CE was calculated using the built-in Excel function based on the CE values obtained over discharging-charging cycles of a Li | |Cu cell, which reflects the fluctuation of CE during cycling. The Li | |SPAN full cells were cycled in a potential window of 1-2.8 V without pre-cycling. The applied specific current rates for all tests were specified in the corresponding figures. The cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests of Li | |SPAN batteries for in situ UV-VIS measurements were conducted within the potential window of 1.0–2.8 V at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1. The CE of Li | |Cu and Li | |SPAN batteries were defined as the ratio of charge capacity divided by the discharge capacity in the preceding charge cycle. To ensure reproducibility, duplicate cells were tested for each battery system.

Characterizations

The ionic conductivity of the electrolytes was measured by testing the EIS curves of a blocking electrode. 13C and 19F NMR tests were performed with a Bruker 600 MHz instrument (B0 = 14.1 T) equipped with a 5 mm broadband BBO probe. 7Li NMR tests were performed with a Bruker AVANCE III 400 MHz instrument (B0 = 9.4 T) using a 5 mm PABBO broadband probe, where a solution of 1 M LiCl in D2O was used as a reference. The WAXS measurements of liquid electrolytes were carried out on a Xenocs Xeuss 2.0 instrument equipped with a Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.54189 Å, 30 W) and a Pilatus 3 R 300 K detector (pixel size = 172 μm); the sample-to-detector distance was fixed at 94.9 mm, and each pattern was acquired with an exposure time of 300 s. The SEM observation was conducted with a Tescan MAIA3 microscope with a beam voltage of 5 kV. The TEM characterization was carried out by using a JEOL JEM-F200 microscope with a beam voltage of 200 kV. XPS measurements were performed on a Thermo Fisher Scientific Nexsa system equipped with a monochromatic Al Kα source (hν = 1486.6 eV), and the binding energies were calibrated to the C 1 s peak at 284.8 eV to correct for surface charging. The TOF-SIMS tests were accomplished by using the IONTOF TOF-SIMS M6 instrument. The cycled electrodes used for SEM observation, XPS, and TOF-SIMS analyses were disassembled from the tested cells and rinsed with the corresponding solvents inside an argon-filled glovebox, and all the samples were subsequently transferred into the instrument chambers under an inert atmosphere to prevent air exposure and contamination. In situ UV-VIS measurement was performed with a ThermoFisher Evolution200 spectroscopy, where the absorption spectra were background-corrected using the electrolytes in the Li | |SPAN batteries before electrochemical reaction as the reference.

The EIS measurements of the cycled Li | |SPAN batteries were performed using a three-electrode configuration assembled in a CR2032-type coin cell. In each cell, a clean Li wire (2*5 mm) served as the reference electrode, which was connected via a Cu lead. The Li wire is separated by separators and positioned at the edge of the positive and negative electrodes, ensuring it does not obstruct Li+ transport while remaining sufficiently close to the electrode under detection. Particular attention was paid to insulating all exposed portions of the Cu lead that could potentially contact the positive or negative electrode shells. The assembled batteries were encapsulated in polydimethylsiloxane to prevent damage caused by moisture condensation during low-temperature cycling and testing. Prior to EIS characterization, the cells underwent 30 charge-discharge cycles at three different temperatures (25, 0, and −20 °C) and were subsequently discharged to 50% state-of-charge. All impedance measurements were conducted using a BioLogic VMP3 potentiostat system under open-circuit conditions at their respective cycling temperatures. The frequency range was swept from 100 kHz to 0.01 mHz with an applied AC amplitude of 10 mV.

The PFG-NMR tests were performed with a Bruker AVANCE NEO 600 WB Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectrometer with a 5 mm PFG BBO probe, which has a maximum gradient field of 1680 Gauss cm−1. The PFG echo intensity was measured after a PFG NMR pulse sequence was executed. All samples were thoroughly filtered and treated to remove impurities and particulates, thereby minimizing measurement artifacts and improving reproducibility. The diffusion coefficient D was obtained by fitting the linearized Stejskal-Tanner Eq. (1)56.

Where I and I0 are the intensities of the PFG echo profile at gradient strengths of s and 0, respectively, γ is the gyromagnetic ratio, δ is the gradient duration, g is the gradient strength, and Δ is the gradient pulse interval, i.e., the diffusion time.

Theoretical computations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of three electrolyte systems were performed using the GROMACS software suite57. The interactions within the systems were described by a carefully constructed hybrid force field that integrates parameters from multiple sources to ensure high fidelity. Specifically, the neutral solvent molecules (DME, DBE, and EBE) were modeled with the OPLS-AA/M force field58,59,60, where the standard atomic charges were replaced by more accurate RESP2(0.5) charges obtained from density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The Li⁺ cations were parameterized using the Madrid-2019 force field61, while the FSI⁻ anions were described by the CL&P force field62. To account for polarization and charge transfer phenomena common in ionic solutions, the charges on both Li⁺ and FSI⁻ were scaled by a factor of 0.85, a value consistent with established protocols for concentrated solutions63. Topological files for these molecules and ions were autogenerated using the all-atom and ionic-liquid modules of the AuToFF web server (https://cloud.hzwtech.com/web/product-service?id=36).

Initial configurations were prepared using PACKMOL, where electrolyte components were placed in a 10 × 10 × 10 nm3 cubic box64. The composition of each system, including 50 Li⁺ cations, was set to precisely match the molar ratios used in the experiments. Each system was then subjected to a rigorous equilibration protocol, beginning with energy minimization, followed by a 1 ns simulated annealing cycle from 0 to 400 K and then cool down to target temperature. Subsequently, the systems were equilibrated under NPT conditions, where the temperature was maintained at 253.15/298.15/333.15 K by the velocity-rescale thermostat65 (1 ps time constant) and the pressure was controlled at 1 atm using the Berendsen barostat (isothermal compressibility of 4.5 × 10⁻⁵ bar⁻¹).

For all simulations, periodic boundary conditions were applied in three dimensions. Long-range electrostatic and van der Waals interactions were calculated using the Particle-Mesh Ewald (PME) method with a 1.5 nm real-space cutoff and a 0.12 nm Fourier grid spacing. Following equilibration, a 10 ns production simulation was carried out in the NVT ensemble for each system, with coordinates saved every 1 ps. The final 5 ns of this trajectory were used for all subsequent statistical analyses, which were conducted with the GROMACS tool suite. Molecular visualizations were rendered using VMD66.

The geometries of DME, DBE, EBE, and their complexes with the Li+ cation and Li₂S₆ were optimized within the framework of density functional theory (DFT) using the M06-2X functional67 and the 6-31 G(d) basis set68. All DFT calculations were performed using the Gaussian 16 program suite69. The electrostatic surface potentials (ESP) were calculated using Multiwfn program70 and the mapping of ESPs was rendered using the VMD program.

The binding energy of each complex was calculated using Eq. (2):

where E(A) and E(B) represent the energies of the isolated molecules, and E(A + B) is the total energy of the complex.

Data availability

All the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Liu, D.-H. et al. Developing high safety Li-metal anodes for future high-energy Li-metal batteries: strategies and perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 5407–5445 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Pathways for practical high-energy long-cycling lithium metal batteries. Nat. Energy 4, 180–186 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Lithium metal electrode with increased air stability and robust solid electrolyte interphase realized by silane coupling agent modification. Adv. Mater. 33, 2008133 (2021).

Kim, S. et al. Lithium-metal batteries: from fundamental research to industrialization. Adv. Mater. 35, 2206625 (2023).

Liu, Q. & Wang, L. Fundamentals of electrolyte design for wide-temperature lithium metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301742 (2023).

Guo, D. et al. Electrolyte engineering for thermally stable Li–S Batteries Operating from –20 °C to 100 °C. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 8151–8161 (2024).

Q. Chen, Z. Yang, P. Zhai, W. Luo, Y. Gong. Lithium batteries operating at wide temperatures: opportunities and challenges. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2417923, (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Improving cyclability of Li metal batteries at elevated temperatures and its origin revealed by cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Energy 4, 664–670 (2019).

Hwang, J.-Y., Park, H., Kim, H., Kansara, S. & Sun, Y.-K. Advanced cathodes for practical lithium–sulfur batteries. Acc. Mater. Res. 6, 245–258 (2025).

Phan, A. L., Le, P. M. L. & Wang, C. Realizing High-Energy and Long-Life Li/SPAN Batteries. Joule 8, 1601–1618 (2024).

Wang, J., Yang, J., Xie, J. & Xu, N. A Novel conductive polymer–sulfur composite cathode material for rechargeable lithium batteries. Adv. Mater. 14, 963–965 (2002).

Wei, S., Ma, L., Hendrickson, K. E., Tu, Z. & Archer, L. A. Metal–sulfur battery cathodes based on PAN–sulfur composites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 12143–12152 (2015).

Chen, X. et al. Ether-Compatible Sulfurized Polyacrylonitrile Cathode with Excellent Performance Enabled by Fast Kinetics via Selenium Doping. Nat. Commun. 10, 1021 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. Regulating interface dipole interaction between ethers and active species toward highly stable Li-SPAN batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202416731 (2025).

Xiang, J. & Lu, Y.-C. Ether-based high-voltage lithium metal batteries: the road to commercialization. ACS Nano 18, 10726–10737 (2024).

Wang, S., Shi, J., Liu, Z. & Xia, Y. Advanced ether-based electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2401526 (2024).

He, Y. et al. Dual passivation of cathode and anode through electrode–electrolyte interface engineering enables long-lifespan Li metal–SPAN batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 2866–2875 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. Interphase Engineering via Solvent Molecule Chemistry for Stable Lithium Metal Batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202317923 (2024).

Holoubek, J. et al. Toward a quantitative interfacial description of solvation for li metal battery operation under extreme conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2310714120 (2023).

Wang, Z. & Zhang, B. Weakly solvating electrolytes for next-generation lithium batteries: design principles and recent advances. Energy Mater. Dev. 1, 9370003 (2023).

Wang, D., Du, X. & Zhang, B. Solvent molecular design to regulate the intercalation behavior in ether electrolyte for stable graphite anodes in potassium-ion batteries. Small Struct. 3, 2200078 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Steric effect tuned ion solvation enabling stable cycling of high-voltage lithium metal battery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 18703–18713 (2021).

Wang, Z., Chen, C., Wang, D., Zhu, Y. & Zhang, B. Stabilizing Interfaces in High-Temperature NCM811-Li Batteries via Tuning Terminal Alkyl Chains of Ether Solvents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202303950 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Non-Flammable Ester Electrolyte with Boosted Stability Against Li for High-Performance Li Metal Batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202206682 (2022).

Holoubek, J. et al. Tailoring Electrolyte Solvation for Li Metal Batteries Cycled at Ultra-Low Temperature. Nat. Energy 6, 303–313 (2021).

Cai, G. et al. Solvent Selection Criteria for Temperature-Resilient Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2200392119 (2022).

Li, Z., Liu, J., Bi, X., Qin, Y. & Gao, T. Single-Oxygen Linear Ether (SOLE) Based Electrolytes for Fast-Charging and Low-Temperature Li-Ion Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 19996–20010 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. Electrostatic Potential as Solvent Descriptor to Enable Rational Electrolyte Design for Lithium Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2300259 (2023).

Ren, X. et al. Localized High-Concentration Sulfone Electrolytes for High-Efficiency Lithium-Metal Batteries. Chem 4, 1877–1892 (2018).

Han, K. S. et al. Pulsed Field Gradient Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Diffusion Analysis in Battery Research. Chem. Mater. 33, 8562–8590 (2021).

Ishfaq, H. A. et al. Transport Number Determination and Relevance for Lithium Metal Batteries Using Localized Highly Concentrated Electrolytes. Chem. Mater. 37, 2485–2495 (2025).

Wohde, F., Balabajew, M. & Roling, B. Li+ Transference Numbers in Liquid Electrolytes Obtained by Very-Low-Frequency Impedance Spectroscopy at Variable Electrode Distances. J. Electrochem. Soc. 163, A714–A721 (2016).

Borodin, O., Smith, G. D. & Henderson, W. Li+ Cation Environment, Transport, and Mechanical Properties of the LiTFSI Doped N-Methyl-N-alkylpyrrolidinium+TFSI- Ionic Liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 16879 (2006).

Wang, Q. et al. High Entropy Liquid Electrolytes for Lithium Batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 440 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. A “Tug-of-War” Effect Tunes Li-Ion Transport and Enhances the Rate Capability of Lithium Metal Batteries. Chem. Sci. 14, 2745–2754 (2023).

Guinier, A., Fournet, G., Walker, C. B. & Vineyard, G. H. Small-Angle Scattering of X-Rays. Phys. Today 9, 38–39 (1956).

Liu, X. et al. Insight into the Nanostructure of “Water in Salt” Solutions: A SAXS/WAXS Study on Imide-Based Lithium Salts Aqueous Solutions. Energy Storage Mater. 45, 696–703 (2022).

Jie, Y. et al. Towards Long-Life 500 Wh kg−1 Lithium Metal Pouch Cells via Compact Ion-Pair Aggregate Electrolytes. Nat. Energy 9, 987–998 (2024).

Fang, C. et al. Quantifying Inactive Lithium in Lithium Metal Batteries. Nature 572, 511–515 (2019).

Mohammadi, A. et al. Assessing Coulombic Efficiency in Lithium Metal Anodes. Chem. Mater. 35, 2381–2393 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Unraveling the Solvent Effect on Solid-Electrolyte Interphase Formation for Sodium Metal Batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313447 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Sulfurized Polyacrylonitrile Cathodes with High Compatibility in Both Ether and Carbonate Electrolytes for Ultrastable Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1902929 (2019).

Aurbach, D., Daroux, M. L., Faguy, P. W. & Yeager, E. Identification of Surface Films Formed on Lithium in Propylene Carbonate Solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 134, 1611 (1987).

Fan, X. et al. Non-Flammable Electrolyte Enables Li-Metal Batteries with Aggressive Cathode Chemistries. Nat. Nanotech. 13, 715–722 (2018).

Hobold, G. M., Wang, C., Steinberg, K., Li, Y. & Gallant, B. M. High Lithium Oxide Prevalence in the Lithium Solid–Electrolyte Interphase for High Coulombic Efficiency. Nat. Energy 9, 580–591 (2024).

Zeng, H. et al. Beyond LiF: Tailoring Li2O-Dominated Solid Electrolyte Interphase for Stable Lithium Metal Batteries. ACS Nano 18, 1969–1981 (2024).

Zhang, X.-Q. et al. Highly Stable Lithium Metal Batteries Enabled by Regulating the Solvation of Lithium Ions in Nonaqueous Electrolytes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 5301–5305 (2018).

Yan, C. et al. Lithium Nitrate Solvation Chemistry in Carbonate Electrolyte Sustains High-Voltage Lithium Metal Batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 14055–14059 (2018).

Chen, H. et al. Uniform High Ionic Conducting Lithium Sulfide Protection Layer for Stable Lithium Metal Anode. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1900858 (2019).

Cheng, Y. et al. Catalytic Chemistry Derived Artificial Solid Electrolyte Interphase for Stable Lithium Metal Anodes Working at 20 mA cm−2 and 20 mAh cm−2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202305723 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Building Artificial Solid-Electrolyte Interphase with Uniform Intermolecular Ionic Bonds toward Dendrite-Free Lithium Metal Anodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2002414 (2020).

Ma, T. et al. Reversible Solid–Solid Conversion of Sulfurized Polyacrylonitrile Cathodes in Lithium–Sulfur Batteries by Weakly Solvating Ether Electrolytes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202310761 (2023).

Dou, R., Wang, Q., Ren, X. & Lu, L. In-situ UV-Vis Spectroscopy of Trisulfur Radicals in Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 40, 279–286 (2024).

Häcker, J. et al. Operando UV/vis Spectroscopy Providing Insights into the Sulfur and Polysulfide Dissolution in Magnesium–Sulfur Batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 1–9 (2022).

Kim, J. T., Hao, X., Wang, C. & Sun, X. Cathode Materials for Single-Phase Solid-Solid Conversion Li-S Batteries. Matter 6, 316–343 (2023).

Stejskal, E. O. & Spin Diffusion, J. E. T. anner Measurements: Spin Echoes in the Presence of a Time-Dependent Field Gradient. J. Chem. Phys. 42, 288–292 (1965).

Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: High Performance Molecular Simulations Through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 1-2, 19–25 (2015).

Kaminski, G. A., Friesner, R. A., Tirado-Rives, J. & Jorgensen, W. L. Evaluation and Reparametrization of the OPLS-AA Force Field for Proteins via Comparison with Accurate Quantum Chemical Calculations on Peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 6474–6487 (2001).

Jorgensen, W. L., Maxwell, D. S. & Tirado-Rives, J. Development and Testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225–11236 (1996).

Robertson, M. J., Qian, Y., Robinson, M. C., Tirado-Rives, J. & Jorgensen, W. L. Revised RNA Dihedral Parameters for the Amber Force Field Improve RNA Molecular Dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 2734–2742 (2019).

Zeron, I. M., Abascal, J. L. F. & Vega, C. A force field of Li+, Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Cl−, and SO42− in aqueous solution based on the TIP4P/2005 water model and scaled charges for the ions. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 134504 (2019).

Canongia Lopes, J. N. & Pádua, A. A. H. CL&P: a generic and systematic force field for ionic liquids modelling. Theor. Chem. Acc. 131, 1129 (2012).

Jeon, J., Lee, H., Choi, J.-H. & Cho, M. Modeling and simulation of concentrated aqueous solutions of LiTFSI for battery applications. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 11790–11799 (2020).

Martínez, L., Andrade, R., Birgin, E. G. & Martínez, J. M. PACKMOL: a package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2157–2164 (2009).

Bussi, G., Donadio, D. & Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 014101 (2007).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 (1996).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215–241 (2008).

Yoshimine, M., McLean, A. D., Liu, B., DeFrees, D. J. & Binkley, J. S. Electron correlation and basis set effects on the relative stabilities of classical and nonclassical structures of the 2-norbornyl cation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 6185–6186 (1983).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Fox, Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01, Wallingford, CT, 2016.

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Quantitative analysis of molecular surface based on improved marching tetrahedra algorithm. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 38, 314–323 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express sincere thanks for the financial support from NSFC/RGC Joint Research Scheme (Project No. N_PolyU584/23), the Research Institute for Smart Energy (Project No. Q-CDBJ), and RCNN (Project No. 1-CE0H) of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Z.W. acknowledges the Centrally Funded Postdoctoral Fellowship (No. 1-YXAU) and Distinguished Postdoctoral Fellowship (No. 4-YWE6) of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W. and B.Z. conceived the project design. Z.W. and Y.W. conducted and analyzed the experiments. Z.W., X.H., and M.G. performed the theoretical computations. Z.W. wrote the manuscript. B.Z. supervised the project. All authors contributed to the discussion and reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Wang, Y., He, X. et al. Designing bi-layer electrode-electrolyte interfaces with an asymmetric ether to enable wide-temperature lithium metal batteries. Nat Commun 16, 10976 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65938-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65938-y