Abstract

High-efficiency integrated difference frequency generation (DFG) has long been pursued for optical communications and signal processing. Recent developments of the thin-film lithium niobate platform enable strong optical confinement in nanoscale waveguides, greatly enhancing the nonlinear efficiencies. However, the absolute DFG conversion efficiencies (CEs) in recent studies are limited because of fail to satisfy the phase-matching condition strictly. Here, we demonstrate an integrated DFG device based on an adapted thin-film periodically poled lithium niobate waveguide. The generated idler wave achieves a maximum output power of 13.2 dBm and a CE of 48.6%. Furthermore, our device exhibits flat optical responses and high-quality eye diagrams when converting a signal at 1638 nm to an idler at 1556 nm, enabling bringing unique-band light into the amplifier’s gain band. By overcoming the efficiency limitations of previous DFG implementations, our work opens wider possibilities for practical applications in optical communications, wavelength conversion, and signal amplification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global data traffic has emerged as a critical challenge amid the exponential growth of link capacity requirements in the era of artificial intelligence. Accessing new wavelength spectra beyond the conventional communication band in optical communications is crucial for increasing transmission capacity, as it enables more data channels to be multiplexed within the same fiber. However, coherent light waves are typically generated through stimulated emission in III-V semiconductor materials, such as InP and InGaAs-based laser sources1,2,3,4,5. The achievable wavelengths are fundamentally constrained by the electronic band structure of these materials, making it difficult to produce coherent light at certain desired wavelengths. Additionally, conventional optical fiber amplifiers, such as erbium-doped fiber amplifiers (EDFA), exhibit limited gain bandwidth, restricting the use of wavelengths outside their amplification spectrum. Nonlinear parametric processes, including second-harmonic generation6,7,8,9,10,11,12, sum-frequency generation13,14,15,16, and difference-frequency generation (DFG)17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27, provide a powerful solution to these challenges by transforming coherent light within conventional gain spectra into light at desired wavelengths. Crucially, they can also shift light from outside the amplifier’s gain band into the amplifiable range, thereby overcoming spectral limitations. Among these techniques, DFG stands out due to its broad wavelength tunability, making it uniquely valuable for flexible and wideband optical signal processing.

Periodically poled lithium niobate (PPLN) has been widely explored for nonlinear wavelength conversion through parametric processes owing to its excellent optical properties, such as a broadband transparency window ranging from 400 nm to 5 μm and large second-order nonlinear coefficients (27 pm/V@d33). The emergence of thinfilm lithium niobate (TFLN) platform with nano-scale confinement of optical fields enhances light-matter interaction strength for several orders, significantly reducing the device length and pump power when compared with bulky PPLN28,29,30. Moreover, compact thin-film PPLN devices make nonlinear wavelength conversion easier be integrated with other optical components to realize versatile and functional chips31,32,33,34. Consequently, DFG devices based on thin-film PPLN have attracted significant interest in the past few years. In 2019, Liu et al. demonstrated the DFG process in a TFLN microdisk with a conversion efficiency (CE) of approximately 10-420. In 2019, Luo et al. demonstrated the DFG process in a TFLN microring resonator with a conversion rate of −53 dB21. In 2021, Mishra et al. proposed an on-chip DFG device based on a thin-film PPLN waveguide, enabling wavelength conversion from near-infrared region to mid-infrared region of 3.3 μm with a normalized CE of 200% (W−1cm−2)22. In 2024, Koyaz et al. demonstrated an ultrabroadband tunable DFG device covering 1418–1862 nm using a dispersion-engineered thin-film PPLN waveguide23. However, high absolute CE DFG devices based on thin-film PPLN waveguides have barely been reported because the thickness inhomogeneity of TFLN can severely disrupt the phase-matching condition.

In this work, we present a high-efficiency and broadband integrated DFG device based on a thin-film PPLN waveguide. An adapted-poling method was adopted to overcome the thickness inhomogeneity issue [11]. The device achieves remarkable performance by generating an idler wave with a maximum output power of 13.2 dBm and a record CE of 48.6%, while maintaining a normalized CE exceeding 100% W−1cm−2 across a 90 nm bandwidth. Significantly, the demonstrated DFG device achieves excellent signal fidelity when converting a modulated 1638 nm signal (outside conventional amplifier bands) to a 1556 nm idler (within the EDFA gain spectrum), as evidenced by flat optic-optic response and well-preserved eye diagrams after DFG conversion. The breakthroughs in efficiency and bandwidth overcome previous DFG limitations, paving the way for practical applications in optical communications, wavelength conversion, and amplifier technologies.

Results

Design and fabrication

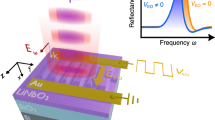

Figure 1a shows a schematic illustration of the DFG process in a thin-film PPLN waveguide. A cross-sectional view of the designed waveguide with a width w of 2 μm, waveguide thickness t of 600 nm, and etch depth h of 300 nm is shown in Fig. 1b. The sidewall angle of the waveguide was set as 60° due to the isotropic etching process of the TFLN. It should be noted that the exact thickness t is not strictly 600 nm across a TFLN wafer because of imperfect smart-cut technology. The thickness variations are more than 5 nm for the state-of-the-art TFLN wafers currently. Therefore, the exact thickness of the TFLN layer was measured using an optical thickness measuring instrument based on reflectance measurements, as shown in Fig. 1c first. A two-dimensional motorized moving stage was placed under the thin-film PPLN chip to precisely acquire the thickness distribution. Subsequently, the poling period distribution along the waveguide was calculated according to the measured thickness distribution. Therefore, the phase-matching condition can be satisfied even with a non-uniform thickness distribution along the waveguide; thus, the absolute DFG efficiency limitation can be overcome. The fitted curve of the measured thickness distribution (dashed) with a step of 200 μm along a 1-cm-thin-film PPLN waveguide is plotted in Fig. 1d. As a result, the corresponding poling period distribution involving three wave mixing wavelengths of 798 nm, 1550 nm, and 1645 nm in the designed waveguide can be obtained according to the phase-matching condition. Figure 1d plots the calculated poling period distribution (solid) along the 1-cm-thin-film PPLN waveguide (see note 2 in the supplementary information).

Figure 2a–c present the simulated modal profiles of the interacting waves in the thin-film PPLN waveguide, the pump, signal, and idler waves were fixed at 798 nm, 1607.9 nm, and 1584.3 nm, respectively, to satisfy the energy conservation condition (see note 1 in the supplementary information). Figure 2d–f present the simulated DFG conversion characteristics in the thin-film PPLN waveguide, obtained by solving the coupled-wave equations (see note 1 in the supplementary information). Under ideal conditions with perfect thickness uniformity, the simulations (Fig. 2d) show stable and efficient energy transfer from pump to signal and idler waves. When accounting for the actual measured thickness variations in the TFLN layer (Fig. 2e), although initial power transfer occurs, the signal and idler powers quickly begin oscillating around low values, resulting in fundamentally limited conversion efficiency that cannot be improved by simply increasing the interaction length (see note 3 in the supplementary information). However, implementing customized compensation through adaptive poling period adjustments can effectively counteract the thickness inhomogeneity effects as shown in Fig. 2f, leading to substantial improvements in both signal and idler output powers.

a–c Simulated modal profiles of (a) pump, (b) signal, and (c) idler waves in the designed thin-film PPLN waveguide. d–f Simulated DFG conversion characteristics of pump, signal, and idler waves under conditions of ideal phase matching (d), without the adapted-poling method (e), and with the adapted-poling method (f) when inhomogeneity of the TFLN layer is considered. g Simulated normalized CE at different signal wavelengths in conditions of ideal phase matching and with the adapted-poling method. h Simulated normalized CE at different signal wavelengths under different thickness measuring step sizes.

Figure 2g illustrates the simulated normalized CE across varying signal wavelengths. Both the adapted-poling and ideal scenarios exhibit robust difference-frequency generation (DFG) operation spanning the 1420–1820 nm wavelength range, yielding a theoretical bandwidth of approximately 400 nm. The close correspondence between the adapted-poling and ideal CE profiles further validates the efficacy of our adapted-poling technique in enabling high-performance DFG. To assess the impact of measurement step size in the adapted poling process, we analyzed the normalized CE dependence under different measurement step sizes as shown Fig. 2h. The results reveal a clear degradation in CE with increasing step size, attributed to the loss of detailed thickness distribution information during the characterization process. This highlights the critical need for high-resolution thickness measurements to optimize device performance. Therefore, a step size of 200 μm towards the experimental setup limitation was adopted.

Device characterization

We fabricated the device on a 600-nm x-cut 5% MgO-doped TFLN on a 2-μm silica with a 525-μm-thick Si substrate. Figure 3a shows an optical microscope image of the facet of the fabricated thin-film PPLN waveguide for fiber-waveguide coupling. The piezoelectric force microscope (PFM) signal of the periodical ferroelectric domain inversion in the thin-film PPLN waveguide is shown in Fig. 3b, indicating uniform periodical poling of the fabricated waveguides. Figure 3c shows a scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the chip facet. The experimental setup for the DFG performance characterization is shown in Fig. 3d. An image of the chip in the DFG experiment captured by the camera is shown in Fig. 3e. The bright visible light radiating from the chip indicates the high-power second-order nonlinear phenomena.

a Optical microscope image of waveguide facets. b The measured PFM signal of the periodical ferroelectric domain inversion in the thin-film PPLN waveguide. c SEM image of a waveguide facet. d Experimental setup for DFG characterization. e Captured image of the chip in the DFG experiment. f Measured spectrum of signal and idler waves. g Simulated (line) and measured (dots) normalized CEs of DFG at different temperatures. TEC, thermoelectric cooler. PD, photodetector. PC, polarization controller. WDM, wavelength division multiplexer.

Firstly, the coupling losses of the pump and signal waves were characterized by simultaneously injecting the pump and signal waves into the thin-film PPLN waveguide under test. The coupling loss of the pump wave was estimated to be ~6.5 dB/facet after carefully calibrating the relative positions between the thin-film PPLN waveguide and the lens fibers. The coupling loss for the signal wave was estimated to be ~6.8 dB/facet under the condition that the pump wave has a minimum coupler loss. The losses of polarization controllers (PCs) were evaluated as 0.4 dB and 0.5 dB for pump and signal/idler waves, respectively. The losses of the wavelength division multiplexers (WDMs) were measured as 0.5 dB for pump, signal, and idler waves. The coupling loss of the signal wave is higher than that of the pump wave because of the wavelength-dependent modal profiles of the fibers and the waveguide. The coupling losses for the signal and idler waves were estimated to be the same because their wavelengths were similar when compared with the pump wave. Under the on-chip input powers of pump and signals of 19.3 dBm and 21.2 dBm, respectively, the best DFG performance was observed when the wavelength of the signal wave was tuned to 1607.9 nm and the temperature of the chip was tuned to 50 °C. The spectrum of the recorded signal and idler waves is shown in Fig. 3f, where the peaks on the left and right refer to the idler and signal waves, respectively. In addition, the measured power of the idler wave on the chip can reach up to 13.2 dBm, indicating that the CE of the DFG process in this chip can reach up to 48.6%. The CE of the DFG process was evaluated by the ratio of the power of the pump wave converted to the signal and idler waves. The measured (dots) and fitted (line) normalized CE of the DFG process as a function of temperature are shown in Fig. 3g, indicating that the chip temperature had already been optimized to obtain the highest efficiency of the DFG process. The peak around 1596 nm in the spectrum mainly originated from the seed wave inside the pump laser source and was observed when only a pump wave was injected into a TFLN waveguide without periodical poling.

To characterize the broadband response of the DFG process, we performed a wavelength sweep of the signal wave. The on-chip signal wave power was maintained at approximately 21 dBm (with EDFA amplification) and 7 dBm (without EDFA amplification) across the entire sweep range. The on-chip powers of the signal and idler waves were estimated from the recorded spectral data after calibrating the exact power of the optical spectrum analyzer (OSA) with a photodetector and are presented in Fig. 4a, b. In the absence of EDFA amplification, the signal wavelength was swept from 1500 nm to 1640 nm, covering the full tuning range of the laser source. Within this range, an idler wave was observed for signal wavelengths between 1505 nm and 1640 nm, confirming the broadband DFG response of the fabricated thin-film PPLN waveguide. Notably, no idler signal was detected for signal wavelengths below 1505 nm because the corresponding idler wavelengths fell outside the operational range of the optical spectrum analyzer (OSA). Future experiments using instruments with a broader spectral response are expected to reveal an even wider DFG bandwidth. When EDFA amplification was applied, the sweep range was constrained to 1530–1610 nm due to the limited gain bandwidth of the amplifier. The absolute CE derived from the amplified on-chip power is plotted in Fig. 4c, showing CE around or above 20% between 1554 nm and 1610 nm. Additionally, the normalized CE was measured without EDFA amplification to maximize the broadband response as shown in Fig. 4d. A peak value of >710% (W−1cm−2) and the normalized CE remained above 100% (W−1cm−2) over 90 nm are observed, further highlighting the high performance of the thin-film PPLN waveguides.

To validate the practical application of the fabricated DFG device in optical communication systems, we conducted a wavelength conversion experiment. The primary objective was to demonstrate the conversion of signal waves outside the EDFA gain spectrum to idler waves within the amplification band. This capability effectively extends the usable wavelength range beyond conventional EDFA limitations, enabling amplification of signals that would otherwise fall outside the amplifier’s operational bandwidth. The experimental configuration for evaluating the optical communication performance is illustrated in Fig. 5a. The experimental setup was designed to characterize the ability of the DFG device to maintain signal integrity while performing wavelength conversion across different wavelength spectral regions. The electro-optic (EO) response of the idler wave can be obtained by modulating the signal wave, but measuring the idler wave after the DFG process. The optic-optic (OO) response of the DFG process S21,DFG can be calculated by comparing EO responses of both the converted idler wave S21,idler and the original signal wave S21,signal, and written as

The normalized OO response of DFG S21, NORM can be evaluated as

a Experimental setup for OO response measurement after DFG process. b Measured optical spectrum of the idler wave. c Measured EO responses of the signal and idler waves. d Measured normalized OO response after DFG process. e Calculated eye diagram from EO responses of the signal and idler waves at data rates of 20 Gbps (right) and 40 Gbps (left). TEC, thermoelectric cooler. PD, photodetector. PC, polarization controller. WDM, wavelength division multiplexer. VOA, variable optical attenuator. BPF, bandpass filter.

Figure 5b presents the measured optical spectrum obtained from the OSA, demonstrating complete suppression of the signal wave through band-pass filtering. This confirms that the EO response recorded by the vector network analyzer (VNA) originates from the idler wave. The inset provides a detailed view of the idler wave spectrum, observed sidebands verify successful transfer of the modulation from the signal to the idler waves through the DFG process. The EO responses of both the converted idler wave (red trace) and the original signal wave (blue trace) are plotted in Fig. 5c. The signal wave response was acquired by directly coupling the electro-optic modulator (EOM) output to the VNA’s high-speed photodetector module. The remarkable similarity in response characteristics between the signal and idler waves demonstrates faithful modulation transfer during wavelength conversion. The normalized OO response of the DFG process, derived from the measured S21 parameters of both waves, is shown in Fig. 5d. The response exhibits excellent flatness across a broad microwave spectrum, indicating consistent conversion efficiency over a wide frequency range. Finally, Fig. 5e displays well-open eye diagrams generated from time-domain analysis of both signal and idler wave responses, with all eyes remaining clearly open after the DFG conversion process. These results conclusively demonstrate that our on-chip DFG process preserves modulation integrity while enabling wavelength conversion, thereby extending the operational wavelength range of optical communication systems beyond conventional EDFA amplification bands.

We further compare our DFG performance with lithium niobate-based DFG devices as shown in Table 1. The overall CE and NCE of DFG exceed the state-of-the-art of integrated lithium niobate devices. Further, the CE and output idler power can be improved by improving the pump power. Ultra-broadband and low noise integrated optical parametric amplification with a gain more than 10 dB can be expected.

Discussion

In conclusion, we demonstrated an integrated DFG wavelength conversion device based on an adapted thin-film PPLN waveguide. The periods of periodical poling were precisely tailored by measuring the thickness distribution of the TFLN layer. This customization aimed to effectively minimize the phase mismatches induced by the inhomogeneity of the TFLN thickness. The experimental results demonstrate the remarkable performance of the DFG process, with an absolute CE of up to 48.6%. The bandwidth with a normalized CE of above 100% (W−1cm−2) is beyond 90 nm. The OO response of the DFG wavelength conversion device and the simulated eye diagram results demonstrate the potential feasibility of using it in optical communication systems. By converting the signal wave to the C-band or L-band through the DFG process, the signal wave, which extends beyond the C-band to the L-band, becomes EDFA amplification available without losing the information it carries. Therefore, the demonstrated high-efficiency on-chip DFG device is a promising platform for optical communication systems and integrated laser sources with unique wavelengths. In future work, we aim to design the periods of adapted poling in the DFG process to generate idler waves from the near-infrared to the mid-infrared region, thereby finding many practical applications beyond optical communications, such as imaging and sensing.

Methods

Fabrication

The poling electrodes with customized periods were first patterned by a step of electron-beam lithography (EBL), and a layer of 100/10/150-nm Al2O3/Ti/Au electrodes was deposited by steps of electron-beam evaporation and lift off. Periodical poling was achieved by applying a sequence of short high-voltage pulses through the poling electrodes. Next, another step of EBL was used to form the waveguide pattern, and the pattern was transferred into the TFLN layer by Ar+ plasma dry etching, in which way the waveguide had a sidewall angle θ of ~60°. Finally, the facets of the chip were diced and polished to couple the light from the lens fibers to the waveguides. The PFM was adopted to characterize periodical ferroelectric domain inversion in the poled waveguide.

DFG performance characterization

The pump wave was generated by a high-power continuous-wave (CW) fiber laser source with a fixed wavelength of 798 nm. The signal wave was provided by a tunable CW laser source at telecom wavelengths ranging from 1500 nm to 1640 nm. An EDFA is used to amplify the signal wave when its wavelength sweeps from the C-band to the L-band. A pair of lens fibers was used to couple all interacting waves of the DFG process into and out of the waveguides on the chip. For the input part, two PCs were used to ensure that the pump wave and signal wave propagating in the waveguides were fundamental transverse-electric (TE) modes, ensuring that the largest second-order nonlinear coefficient d33 of TFLN was used to obtain the highest efficiency of the DFG process. The pump and signal waves were combined using a fiber-based WDM. For the output part, the pump wave and the signal/idler wave were split by the other fiber-based WDM. The output pump wave was coupled into a photodetector (HP 81530 A) to monitor the coupling conditions between the fibers and the chip. The output signal and idler waves were sent to an OSA (YOKOGAWA AQ6370C) to observe the DFG performance. Moreover, the temperature of the DFG chip was tuned by a thermoelectric cooler to change the effective refractive indices of all interacting waves in the DFG process, thus the slight phase-mismatching caused by fabrication errors can be compensated.

OO response characterization

The signal light from a tunable laser with a wavelength of 1638 nm, adjusted by a polarization controller, was sent into an EOM, and the EOM imposed high-speed data from a VNA on the signal wave. Subsequently, the modulated signal and pump waves, adjusted by two PCs independently, were combined by a WDM and coupled in and out of the thin-film PPLN waveguide through a pair of lens fibers. Another WDM separated the pump, signal, and idler waves, and the left pump wave was sent into a photodetector to assist fiber-waveguide coupling. On the 1550 nm port, only the idler wave is left after transmitting through a band-pass optical filter. An EDFA and a variable optical attenuator were used to amplify the idler wave to a suitable power. A 50:50 fiber-based splitter splits the idler wave into the OSA and the high-speed photodetector of the VNA optical module.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study have been included in the main text and Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Wang, Z. et al. Room-temperature InP distributed feedback laser array directly grown on silicon. Nat. Photon 9, 837–842 (2015).

Han, Y. et al. Room-temperature InP/InGaAs nano-ridge lasers grown on Si and emitting at telecom bands. Optica 5, 918 (2018).

Yang, C. et al. Advances in silicon-based, integrated tunable semiconductor lasers. Nanophotonics 12, 197–217 (2023).

Shams-Ansari, A. et al. Electrically pumped laser transmitter integrated on thin-film lithium niobate. Optica 9, 408 (2022).

Op De Beeck, C. et al. III/V-on-lithium niobate amplifiers and lasers. Optica 8, 1288 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. Ultrahigh-efficiency wavelength conversion in nanophotonic periodically poled lithium niobate waveguides. Optica 5, 1438 (2018).

Jankowski, M. et al. Ultrabroadband nonlinear optics in nanophotonic periodically poled lithium niobate waveguides. Optica 7, 40 (2020).

Wu, X. et al. Broadband second-harmonic generation in step-chirped periodically poled lithium niobate waveguides. Opt. Lett. 47, 1574 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Scalable, fiber-compatible lithium-niobate-on-insulator micro-waveguides for efficient nonlinear photonics. Optica 10, 688 (2023).

Hwang, E. et al. Tunable and efficient ultraviolet generation with periodically poled lithium niobate. Opt. Lett. 48, 3917 (2023).

Chen, P.-K. et al. Adapted poling to break the nonlinear efficiency limit in nanophotonic lithium niobate waveguides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 44–50 (2024).

Yang, F., Lu, J., Shen, M., Yang, G. & Tang, H. X. Symmetric second-harmonic generation in sub-wavelength periodically poled thin film lithium niobate. Optica 11, 1050 (2024).

Li, G., Chen, Y., Jiang, H. & Chen, X. Broadband sum-frequency generation using d33 in periodically poled LiNbO3 thin film in the telecommunications band. Opt. Lett. 42, 939 (2017).

Hao, Z. et al. Sum-frequency generation in on-chip lithium niobate microdisk resonators. Photon. Res. 5, 623 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. Quantum frequency conversion and single-photon detection with lithium niobate nanophotonic chips. npj Quantum Inf. 9, 38 (2023).

Du, H., Zhang, X., Wang, L., Jia, Y. & Chen, F. Tunable sum-frequency generation in modal phase-matched thin film lithium niobate rib waveguides. Opt. Lett. 48, 3159 (2023).

Hu, L., Li, Z., Liu, S., Ning, F. & Tan, R. Intra-cavity difference frequency generation of 3141 nm based on diode pumped rubidium laser and tandem pumped Nd:YVO4 laser. Opt. Commun. 456, 124682 (2020).

Mazzotti, D. et al. Difference-frequency generation in PPLN at 4.25 μm: an analysis of sensitivity limits for DFG spectrometers. Appl Phys. B 70, 747–750 (2000).

Belden, P., Chen, D. & Teodoro, F. D. Watt-level, gigahertz-linewidth difference-frequency generation in PPLN pumped by an nanosecond-pulse fiber laser source. Opt. Lett. 40, 958 (2015).

Liu, S. et al. Effective four-wave mixing in the lithium niobate on insulator microdisk by cascading quadratic processes. Opt. Lett. 44, 1456 (2019).

Luo, R. et al. Optical parametric generation in a lithium niobate microring with modal phase matching. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 034026 (2019).

Mishra, J. et al. Mid-infrared nonlinear optics in thin-film lithium niobate on sapphire. Optica 8, 921 (2021).

Koyaz, Y. et al. Ultrabroadband tunable difference frequency generation in a standardized thin-film lithium niobate platform. Opt. Express 32, 46776 (2024).

Mishra, J. et al. Ultra-broadband mid-infrared generation in dispersion-engineered thin-film lithium niobate. Opt. Express 30, 32752 (2022).

Wei, J. et al. All-optical wavelength conversion of a 92-Gb/s 16-QAM signal within the C-band in a single thin-film PPLN waveguide. Opt. Express 30, 30564 (2022).

Ledezma, L. et al. Intense optical parametric amplification in dispersion engineered nanophotonic lithium niobate waveguides. Optica 9, 303 (2022).

Sua, Y. M., Chen, J.-Y. & Huang, Y.-P. Ultra-wideband and high-gain parametric amplification in telecom wavelengths with an optimally mode-matched PPLN waveguide. Opt. Lett. 43, 2965 (2018).

Rabiei, P., Ma, J., Khan, S., Chiles, J. & Fathpour, S. Heterogeneous lithium niobate photonics on silicon substrates. Opt. Express 21, 25573 (2013).

Korkishko, Y. N. et al. Reverse proton exchange for buried waveguides in LiNbO3. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 15, 1838 (1998).

Sugita, T., Mizuuchi, K., Kitaoka, Y. & Yamamoto, K. 31%-efficient blue second-harmonic generation in a periodically poled MgO:LiNbO3 waveguide by frequency doubling of an AlGaAs laser diode. Opt. Lett. 24, 1590 (1999).

Chen, G. et al. Advances in lithium niobate photonics: development status and perspectives. Adv. Photon. 4, https://doi.org/10.1117/1.AP.4.3.034003 (2022).

Wang, L., Du, H., Zhang, X. & Chen, F. Optical nonlinearity of thin film lithium niobate: devices and recent progress. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 58, 023001 (2025).

Vazimali, M. G. & Fathpour, S. Applications of thin-film lithium niobate in nonlinear integrated photonics. Adv. Photon. 4, https://doi.org/10.1117/1.AP.4.3.034001 (2022).

Nikogosyan, D. N. Nonlinear Optical Crystals: A Complete Survey. (Springer-Science, New York, 2005).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62450079) and the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LDT23F04012F05).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Haoran Li and Z.Y. conceived the idea, Haoran Li and J.G. designed the DFG chip, Haoran Li, J.G., F.H. and H.G. fabricated the chip, Haoran Li characterized the chip, Haoran Li and Z.Y. wrote the manuscript, Hanwen Li contributed to the discussion of the fabrication process, Z.Y., Huan Li, Y.S. and D.D. supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Lute Maleki and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Guo, J., Huang, F. et al. Integrated broadband and high-efficiency difference frequency generation. Nat Commun 16, 11014 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65953-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65953-z