Abstract

Current melanoma prognostic tools have limited clinical use at the bedside, highlighting the need for more effective biomarkers. Dermatoscopy correlates with established prognostic markers obtained through invasive procedures. However, its direct predictive value for metastasis remains unexplored. In this multinational study, 30 dermatologists evaluated 776 dermatoscopic images of melanomas (stage IB and above) for predefined criteria including structures, colors and vessels. Extensive dermatoscopic ulceration and blue-white veil are associated with increased risk of metastasis in the total cohort and reduced recurrence-free survival in early-stage melanomas, while extensive regression is associated with reduced metastasis risk and improved recurrence-free survival. Three predictive models of metastasis: (1) dermatoscopic features only, (2) histopathologic features only, and (3) a combination of both demonstrate comparable prognostic accuracy. Here, we show that dermatoscopy may offer valuable prognostic insights into melanoma’s biological behavior before excision and help guide therapeutic decisions. Prospective validation in future trials is essential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The 8th edition of melanoma staging designated Breslow thickness (BT) and ulceration as the key determinants of prognosis, and essential factors in guiding adjuvant treatment for early-stage tumors1. However, evidence from randomized trials on adjuvant immunotherapy suggested that approximately 30% of stage IIB/IIC patients will experience recurrence despite treatment, which is comparable to stage IIIA-IIIB2,3. Furthermore, registry-based studies indicate that a considerable number of stage I/IIA will relapse, potentially contributing to increased melanoma-related mortality4,5.

The need for more accurate melanoma prognostication, combined with the impact of metastatic events on survival, has driven the development of various prognostic tools6. Clinical information and histopathologic factors of the primary tumor have been incorporated into nomograms to identify patients at high risk of relapse7,8,9. Additionally, gene expression profiles on FFPE specimens of the primary tumor (GEPs), such as the CP-GEP or 31-GEP, tried to stratify patients into recurrence risk groups, based on their genetic profile10,11,12. However, despite external validation, these tools have shown limited clinical use to date.

Dermatoscopy has been shown to significantly improve the early diagnosis of melanoma13,14. In addition, studies suggest that certain dermatoscopic features may predict Breslow thickness, ulceration, and sentinel lymph node (SLN) positivity, indicating their potential for indirect prognostic assessment15,16. However, evidence directly linking dermatoscopic structures to the risk of melanoma spread at locoregional or distant sites remains limited.

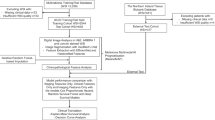

In this work, we evaluate the role of dermatoscopy in predicting melanoma prognosis by investigating whether specific dermatoscopic criteria are associated with the development of tumor metastasis. To this end, we recruit patients with cutaneous melanoma and adequate follow-up time for metastasis occurrence in a multinational, multicenter retrospective study conducted in skin cancer centers across the globe. Also, we invite dermatologists, experienced in dermatoscopy, to evaluate dermatoscopic images of the primary tumor based on predefined criteria via a web-based interface. According to their ratings, we identify dermatoscopic criteria predictive of metastasis, which are included in a predictive model of metastasis (model 1). We validate the performance of the model internally by using a stratified split into training and test sets and 5-fold cross-validation, and we explore the clinical relevance by comparing with the performance of models based on established histopathologic prognostic factors, such as Breslow thickness and ulceration (model 2), and the current AJCC classification (model 4). Additionally, we conduct subgroup analyses to evaluate the performance of model 1 in patients with early-stage tumors and sensitivity analyses to examine the validity of our results. Here, we show that dermatoscopy can predict metastasis development with comparable accuracy to current determinants of melanoma staging, while the combination of models proves the most accurate approach. Also, among non-metastatic patients at presentation, specific dermatoscopic features are indicative of metastasis during follow–up, setting the hypothesis for the preoperative prognostic risk evaluation.

Results

Descriptive analysis of the sample

The study included 524 patients with cutaneous melanoma. Their baseline clinical and histopathologic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Metastasis occurred in 222 patients (42.4%), either at the time of initial diagnosis or during the follow-up period. The remaining 302 patients did not develop metastases, with a median follow-up duration of 50 months (IQR, 32–72 months). A detailed breakdown of melanoma stages at diagnosis and during follow-up is available in Table 1 and Fig. 1f.

a. Workflow of the study. Figure 1b–e denotes dermatoscopic images of primary tumor of patients with melanoma who shared similar prognostic characteristics according to current AJCC classification and there were correctly classified by model 1 [b: Breslow thickness (BT): 0.8 mm without ulceration correctly classified as non-metastatic, c: BT: 0.8 mm without ulceration correctly classified as metastatic, d: BT:2.0 mm without ulceration correctly classified as non-metastatic, e: BT: 2.0 mm with ulceration correctly classified as metastatic). Figure f represents melanoma stage transitions at diagnosis and during follow-up. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. (OR: Odds Ratio, HR: Hazard Ratio, RFS: Recurrence-free survival, DMFS: Distant metastasis-free survival).

Reader analysis

The study evaluated 776 dermatoscopic images of primary melanomas, assessed by 30 readers (Fig. 1b–e). These evaluations resulted in 3346 assessments, with a median of five reads per image (range: 1–26). Each reader evaluated a median of 104 images (range: 21–208), with balanced proportions of metastatic and non-metastatic lesions analyzed (Supplementary Table 1). Of the melanomas assessed, 403 (76.9%) had single or multiple images depicting the same anatomical area, while 121 (23.1%) had multiple images capturing different areas of the lesion. The distribution of multi-image cases was comparable between non-metastatic (54/121, 44.6%) and metastatic melanomas (67/121, 55.4%). Interrater agreement varied across features, ranging from fair agreement for color assessment to moderate agreement for pigmentation grade, ulceration, and vascular structures (Supplementary Table 2).

Association of dermatoscopic features with metastasis – Univariate analysis

Dermatoscopic features more frequently present in metastatic melanomas compared to non-metastatic ones included blue-white veil (64.0% vs 42.1%), ulceration (48.7% vs 21.2%), white shiny streaks (60.4% vs 50.0%), red color (74.3% vs 48.3%), blue/gray color (69.4% vs 57.9%), white color (68.9% vs 49.3%), and mixed-type vessels (32.9% vs 9.9%). All these differences were statistically significant (χ²-test, p < 0.05).

In contrast, dermatoscopic features less frequently observed in metastatic melanomas compared to non-metastatic ones included pigmentation occupying more than 75% of the lesion (32.4% vs 73.5%), regression structures occupying more than 50% of the lesion (6.3% vs 12.3%), as well as brown (73.9% vs 89.1%) and black color (41.1% vs 51.3%). These differences were also statistically significant (χ²-test, p < 0.05).

The frequencies of dermatoscopic criteria in both groups are detailed in Supplementary Table 3, while the results of the univariate analysis for predicting melanoma metastasis based on dermatoscopy are presented in Supplementary Table 4.

Multivariable analysis

We developed a predictive model for melanoma metastasis by applying backward elimination to significant dermatoscopic criteria identified in univariate analysis (Table 2, Fig. 2a, Supp. Table 4) and after adjusting for clinical cofounders (i.e. age, sex, anatomic location). The presence of a blue-white veil and extensive ulceration (occupying >50% of the lesion surface area) conferred a 6.43-fold and 3.45-fold elevated risk of metastasis, respectively. Conversely, heavy pigmentation (occupying >75% of the lesion surface area) compared to its absence, as well as extensive regression (occupying >50% of the surface area), emerged as negative predictors of metastasis.

a. Forest plot showing Odds Ratios (ORs) (squares) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) (error bars) for the prediction of metastasis based on predictors entered the last step of multivariable analysis in the total cohort (n = 524 patients). b. Boxes show the Area under the curve (AUC) values from 5-fold cross-validation in training set (n = 425) and test set (n = 99) for the prediction of metastasis. The middle line denotes the AUC value and the upper and lower parts demonstrate the upper and lower 95%CI, respectively. Dots indicate AUCs for individual folds. Two-sided p-values derived from DeLong’s test and stars (*) denote pairwise comparisons of AUC values between three models [training set: M1/M2 p = 0.20, M1/M3 p = 0.52 M2/M3 p = 0.10, test set: M1/M2 p = 0.51, M1/M3 p = 0.72, M2/M3 p = 0.31]. Correction for multiple comparisons was not applied. c. Accurate (TP: true positive, TN: true negative) and false predictions (FP: false positive, FN: false negative) according to status of parameters included in model 1 by AJCC stage in training set (n = 425). The order of variables in y axis is Pigmentation (Pigm.) – Ulceration (Ulcer.) - Regression (Regres.) - Blue-white veil (BWV). H: high, M/L: moderate/low, A: absent. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. (Ref.: reference level).

Comparative analysis of the accuracy of models

The dermatoscopy-based predictive model (Model 1) underwent 5-fold cross-validation on the training set (n = 425), demonstrating 79.1% accuracy (336/425 correct classifications) in predicting metastasis status, with an AUC of 0.802 (95% CI: 0.752–0.854) (Fig. 2b). Clinical and histopathologic associations with metastasis are detailed in Supplementary Table 5. Model 2, incorporating only Breslow thickness and histopathologic ulceration (Table 2), achieved marginally lower performance – 74.5% accuracy (317/425 correct classifications) and an AUC of 0.758 (95% CI: 0.707–0.801). Model 3, combining dermatoscopic and histopathologic predictors, showed superior performance with an AUC of 0.824 (95% CI: 0.784–0.877) (Table 3, Fig. 2b). These patterns persisted during independent validation in the test set (n = 99), where all three models maintained comparable and no statistically significant different performance [AUC (95%CI), model 1: 0.814 (0.732–0.896), model 2: 0.772 (0.682–0.870), model 3: 0.834 (0.757–0.912), DeLong’s test, p-value > 0.05 for pairwise comparisons] (Fig. 2b).

RFS and DMFS in early-stage melanomas

After a median follow-up of 60 months (IQR, 37–83.3 months), 79 of 381 patients (20.7%) with early-stage melanomas developed any type of metastasis, while distant metastases occurred in 63 patients (16.5%). The median time to first metastasis development was 17 months (IQR, 12–36 months). Cox regression analysis of the full dataset of early-stage melanomas, adjusted for clinical cofounders, revealed the following predictors of recurrence-free survival (RFS): In the dermatoscopy-based model (Model 1), extensive ulceration and blue-white veil were associated with reduced RFS, while extensive regression predicted increased RFS. In the histopathology-based model (Model 2), Breslow thickness and ulceration were linked to decreased RFS. In the combined model (Model 3), Breslow thickness, dermatoscopic ulceration, blue-white veil and extensive regression remained significant predictors of RFS (Supp. Table 6).

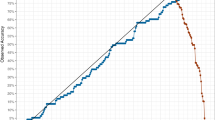

After splitting the dataset of early-stage melanomas into training and test sets, stratified by TNM, age, and sex (Supp. Table 7,8), the 5-fold cross-validation in the training set provided similar AUC values for all three models [AUC (95%CI), model 1: 0.795 (0.721–0.868), model 2: 0.736 (0.650–0.823), model 3: 0.814 (0.764–0.892), DeLong’s test, p-value > 0.05 for pairwise comparisons] (Supp. Table 9, Fig. 3a) When applied to the test set, Model 3 showed a numerically higher AUC compared to Models 1 and 2 (Fig. 3a). Regarding prediction of metastatic events during follow-up, among the 66 patients in the training set who developed metastases, Models 1 and 2 correctly identified 51 (77.2%) and 43 patients (65.1%), respectively, while Model 3 identified 53 patients (80.3%) (Fig. 3c). In the test set, 13 of 13 metastatic patients were correctly classified by Model 1 and 3, while Model 2 identified 11 metastatic patients (84.6%) (Fig. 3d).

a,b Boxes present the Area under the curve (AUC) values from 5-fold cross-validation in training set (n = 306) and test set (n = 75) for the prediction of Recurrence-free survival (RFS) (a) and Distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) (b) in patients with early-stage tumors (n = 381). The middle line in the box denotes the AUC value and the upper and lower parts of the box denote the upper and lower 95%CI, respectively. Dots indicate AUCs for individual folds. Two-sided p-values derived from DeLong’s test and stars (*) denote pairwise comparisons of AUC values between three models [RFS: training set, M1/M2 p = 0.30, M1/M3 p = 0.70 M2/M3 p = 0.15, test set, M1/M2 p = 0.61, M1/M3 p = 0.71, M2/M3 p = 0.37 and DMFS: training set, M1/M2 p = 0.39, M1/M3 p = 0.46, M2/M3 p = 0.12, test set, M1/M2 p = 0.52, M1/M3 p = 0.90, M2/M3 p = 0.49]. Correction for multiple comparisons was not applied. c, d Survival curves according to model 1 classifications in training and test set. Two-sided p-values derived from log-rank test (3c: exact p = 3.52 ×10-13 and 3 d: exact p = 1.02 ×10-6). Survival curves are truncated at 120 months for graphical reasons and no events occurred afterwards. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The same criteria were found to predict distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) in all three models (Supp. Table 6). There was no significant difference in accuracy among the models (DeLong’s test, p > 0.05) (Supp. Table 9, Fig. 3b).

In addition, the incorporation of dermatoscopic features along with AJCC stage into a multivariable model (model 4) deemed blue-white veil and AJCC stage as significant predictors of RFS and DMFS (Supp. Table 10). The accuracy of the model was similar to models 1,2,3 (Supp. Table 11). The prediction of metastatic events of early-stage melanomas based on dermatoscopy (model 1) and according to AJCC stage risk (low risk: stage IB/IIA, high risk: stage IIB/IIC) is shown in Fig. 4a, b. Of note, in AJCC low-risk group, Model 1 accurately split patients into risk categories and captured 23 out of 33 relapses in the training set (69.7%), and four out of four in the test set (100%) (Fig. 4c, d).

a, b Survival curves denote Recurrence-free survival (RFS) of patients predicted as metastatic and non-metastatic by model 1 in training set (n = 306) (a) and test set (n = 75) (b) stratified by AJCC risk categories (IB/IIA: low risk, IIB/IIC: high risk). Two-sided p-values derived from log-rank test calculated over strata (4a: exact p = 6.09 × 0-14 and 4b: exact p = 1.01 ×10-8). c, d Survival curves denote RFS of AJCC low risk patients (gray color) and the classification into predicted metastatic (red color) and non-metastatic (blue color) by model 1 in training (n = 236) (c) and test set (n = 57) (d). Also, patients correctly predicted as metastatic and non-metastatic according to model’s prediction and AJCC classification are shown. Survival curves are truncated at 120 months for graphical reasons and no events occurred afterwards. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Sensitivity analyses

To enhance the robustness and reproducibility of our results, several additional analyses were conducted. First, acral and subungual melanomas potentially confer aggressive biologic behavior and a higher tendency for metastasis development. The exclusion of patients with those lesions from multivariable models renders extensive regression marginally not statistically significant for metastasis prediction in model 1 only (OR 0.46, p = 0.05, 95%CI 0.20–1.00) (Supp. Table 12). Similar results were drawn for extensive regression and RFS for both models 1 and 3, but not for DMFS (Supp. Table 13). Additionally, Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons in univariate analysis, deemed extensive regression structures marginally not significant for metastasis prediction (Supp. Table 14). Furthermore, patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis might exhibit different biological and morphological characteristics compared to patients who developed metastasis during follow-up. Despite the absence of statistically significant association of initial metastatic status (regional or distant) and frequencies of dermatoscopic criteria (Supp. Table 15), when patients with metastasis at diagnosis were excluded, extensive regression rendered marginally not significant in multivariable model 1 (OR 0.35, p = 0.06, 95%CI 0.12–1.07) (Supp. Table 16). Also, despite limited data availability for histopathologic subtype of the primary tumor (n = 291), further adjustment of model 1 for that parameter did not alter primary results (Supp. Table 17).

In addition, analyses based on clinically relevant thresholds across Breslow thickness continuum (i.e., BT > 2 mm constitutes a criterion for selection for adjuvant treatment) revealed significant predictors. For example, the subgroup of thick melanomas exhibiting extensive regression and heavy pigmentation conferred lower risk for metastasis. In contrast, in thin tumors with BT < 2 mm or BT < 1 mm, we found increased metastatic potential for tumors displaying blue-white veil and extensive dermatoscopic ulceration and blue-white veil alone, respectively. Similar results were drawn for early-stage melanomas, RFS, and DMFS (Supp. Table 18,19).

Discussion

The role of dermatoscopy in assessing the biological course of melanoma remains underexplored in medical literature. This analysis identified specific dermatoscopic features associated with an increased risk of metastasis, including blue-white veil, extensive dermatoscopic ulceration, low pigmentation, and the absence of regression structures. A predictive model based on these non-invasive features performed as accurately as the current standard histopathologic predictive TNM staging model, which relies on Breslow thickness and histopathologic ulceration.

Data on the role of dermatoscopy in melanoma prognosis are limited. To date, only two small retrospective analyses have explored the association between dermatoscopic features and tumor metastasis. De Giorgi et al. conducted a case-control study with 16 patients with thin melanomas and found that multiple colors (more than three), an atypical vascular pattern, and blue-gray areas were more frequent in metastatic cases than in non-metastatic controls17. They also observed that acral melanomas developing distant metastasis, particularly lung metastasis, tended to exhibit low pigmentation on dermatoscopy. A single-center Austrian study investigated dermatoscopic features associated with ulceration and mitotic rate, aiming to indirectly predict melanoma’s biological course. The study identified the blue-white veil and milky-red areas as predictors of distant metastasis, while dermatoscopy could not predict SLN status18.

In our analysis, heavy pigmentation (primarily brown) was associated with a favorable prognosis, appearing in 73.5% of non-metastatic cases. This relationship may be explained by the fact that heavy dermatoscopic pigmentation reflects increased melanin levels. In vivo and in vitro studies suggest that melanin affects the nanochemical and elastic properties of melanoma cells. Higher melanin content may promote a well-defined cellular shape and tight cell junctions, which could reduce the tumor’s ability to invade, migrate, and metastasize19,20. Additionally, heavily pigmented melanomas represent a more differentiated tumor state compared to hypopigmented lesions. These hyperpigmented tumors express higher levels of MHC class I molecules and release melanogenesis-related proteins (MPRs), which serve as tumor antigens21,22,23. As a result, they form tighter cell junctions and demonstrate enhanced antigen presentation capacity, leading to increased immune cell recruitment and potentially lower rates of metastasis.

The association between brown color and a good prognosis is easier to explain. Dermatoscopic colors reflect the location of chromophores within the skin, with brown and black indicating melanin presence in the epidermis or upper dermis. A crucial step in melanoma metastasis is the ability of tumor cells to grow beyond the basement membrane and access dermal lymphatic and blood vessels24,25,26. Importantly, the density of these vessels is significantly lower in the upper dermis compared to the deeper dermis27. Thus, brown-colored melanomas observed dermatoscopically are likely in a radial growth phase within the epidermis or upper dermis, a stage associated with very low metastatic potential28,29,30.

In contrast, blue and red colors, especially the presence of a blue-white veil, were associated with a higher risk of metastasis. A plausible explanation is that melanocytes located in the deep dermis are surrounded by a dense vascular network, increasing the likelihood of vascular invasion and subsequent dissemination27,31. Additionally, the blue-white veil corresponds to a raised or palpable area of a lesion, often seen in nodular melanomas, which are inherently more aggressive32,33.

Dermatoscopic ulceration emerged as another significant predictor of metastasis in our multivariable analysis. The AJCC melanoma staging system recognizes histopathologic ulceration as an independent negative prognostic factor1. Mechanistically, the loss of epidermal integrity and tumor cell infiltration through the basement membrane, visible as structureless dark red areas in dermatoscopy, facilitates tumor migration34. This is further supported by increased neovascularization at the ulceration site and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, both of which promote tumor spread35. While the prognostic significance of the extent of histopathologic ulceration remains debated in the literature36,37, our findings suggest that extensive dermatoscopic ulceration poses the highest risk for metastatic progression.

Our analysis identified dermatoscopic regression as a positive prognostic factor in melanoma. In dermatoscopy, scar-like depigmentation and gray granules correspond to papillary dermal fibrosis and melanophages, which are definitive markers of melanoma regression38. Previous observational studies reported higher frequency of dermatoscopic regression structures in melanoma in situ or thin invasive tumors compared to thick lesions39,40, and in patients with negative as compared to positive SLN status41, implicating favorable prognostic characteristics. Regarding histopathologic regression, recent large-scale observational studies have linked regressive melanomas to improved survival outcomes42,43,44,45. Those results were further verified by meta-analyses6,46, which highlight regression as a good prognostic factor leading to decreased risk for distant metastasis6. This may be attributed to an activated immune response against melanoma cells, further supported by higher response rates and better survival in patients with regressive melanomas treated with immunotherapy compared to other treatment modalities42,47. Additionally, in vitro studies have linked the presence of melanophages to improved long-term patient outcomes48. Notably, our findings emphasize the prognostic significance of the extent of dermatoscopic regression, revealing that melanomas with extensive regression carry a lower risk of metastasis.

The interplay between dermatoscopy and melanoma prognosis has recently gained research interest. Initially, dermatoscopic features were found to correlate with indirect prognostic markers, including histopathologic and molecular parameters49,50. More recently, a multicenter cohort study demonstrated that machine learning algorithms analyzing dermatoscopic images could directly predict metastasis development with accuracy comparable to established prognostic factors51. This, along with our reader-based analysis, suggests that dermatoscopic morphology holds prognostic value in melanoma. Integrating this information could enhance risk stratification both pre- and post-operatively for melanoma patients.

Currently, risk stratification and treatment decisions for melanoma primarily rely on histopathologic factors. Adjuvant immunotherapy is recommended not only for stage III melanoma, but also for stages IIB and IIC, which are defined solely by Breslow thickness and ulceration2,3. However, only a subset of stage II patients will relapse, and among them, only a fraction benefits from adjuvant immunotherapy. Rather than exposing all stage II patients to the potential risks of immune-related side effects, a more precise approach would involve identifying and treating high-risk patients while de-intensifying therapy for those at low risk. Additionally, some stage I patients will relapse or progress, and SEER data suggest that stage I melanomas account for nearly 25% of melanoma deaths4. Currently, these patients are treated only after relapse, as no reliable method exists to identify them in advance. Molecular and genetic biomarkers, such as CP-GEP, are under investigation in clinical trials as potential prognostic tools10,52. Findings from primary and subgroup analyses of our study suggest that further research should explore the development of “digital” biomarkers based on dermatoscopy to assess melanoma progression risk and refine treatment strategies.

A key advantage of dermatoscopy is that its prognostic information is available preoperatively, unlike histopathologic or molecular markers, which are only accessible after surgery, unless a diagnostic biopsy is performed beforehand. The obvious benefit is more effective prioritization of surgical interventions. A less obvious but particularly promising implication is the potential role of dermatoscopy in guiding neoadjuvant immunotherapy. Two prospective clinical trials have found significantly improved RFS in stage III melanoma patients treated with neoadjuvant compared to adjuvant immunotherapy53,54. However, whether neoadjuvant therapy is superior in earlier-stage melanoma remains an open question. Preoperative risk assessment would be essential to explore this possibility. Our findings suggest that dermatoscopic morphology could provide valuable preoperative prognostic information as a digital biomarker, potentially aiding in patient selection for future neoadjuvant therapy trials. Notably, the comparative analysis of preoperative dermatoscopic models with postoperative gold standards, such as Breslow thickness and ulceration, revealed a non-significant difference, further supporting the aforementioned implication.

Our study has several limitations. First, the interobserver agreement among readers for the dermatoscopic criteria used as predictors was fair to moderate, indicating variability in the interpretation of dermatoscopic images. Still, among the most prominent dermatoscopic predictors that were used in the models, pigmentation and ulceration had moderate agreement, while blue/gray color and blue-white veil had fair agreement, but with alpha values in the upper quartile of the fair agreement range. To address the known limitation of poor intraobserver agreement on dermatoscopic features, we focused on the most common dermatoscopic features in the evaluation process. However, this approach does not exclude the possibility of other significant dermatoscopic predictors that were not included as variables in our analysis. Additionally, the retrospective nature of our study is prone to selection bias, especially considering the lack of information on the total population of melanoma patients treated in the participating centers. Indeed, the median Breslow thickness of 3.8 mm may indicate a bias towards thicker tumors that are followed up more closely and may not reflect the melanoma patient population. In addition, nodular and acral histopathologic subtypes are considered biologically aggressive melanoma subtypes, but this information was available only in almost half of our patients, and adjustment of multivariable models should be evaluated in that context. Another consideration could be the wide confidence intervals in multivariable models, which could possibly derive from the combination of categories of dermatoscopic predictors with low frequencies, such as extensive ulceration in non-metastatic lesions. These limitations highlight the need for further validation through prospective studies to confirm our findings.

In summary, dermatoscopy has the potential to serve as an additional non-invasive prognostic tool of melanoma, offering valuable insights into the tumor’s biological behavior before excision. This approach could enhance patient risk stratification and decision-making regarding adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatments. Further validation in prospective trials is essential to confirm its utility.

Methods

Guidelines followed

This study followed REMARK guidelines (Supplementary File) with the workflow outlined in Fig. 1a. Each participating center complied with its respective data protection and ethical regulations during image collection. Ethics committee approval was obtained by the School of Medicine of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. The study was retrospective, had no impact on patient management, and used fully anonymized datasets and de-identified dermatoscopic images.

Data source – Patient population

Ten tertiary skin cancer centers worldwide participated in the study, including seven in Europe, one in South America, one in Asia, and one in the United States. Clinical and histopathologic data from patients diagnosed with first primary cutaneous melanoma stage IB and above between 2013 and 2018, along with dermatoscopic images of the primary tumor, and documented follow-up were collected from collaborating institutions. The median time to metastasis in the literature ranges from 25 to 30 months after diagnosis55,56. Therefore, we considered a lesion as non-metastatic if no metastasis was detected after a 36-month follow-up period. Exclusion criteria were missing clinicopathological data, lack of dermatoscopic image of the primary lesion, an inadequate follow-up period and patients with more than 1 simultaneous melanoma.

Participant selection—Web-based study interface—Procedure for lesion evaluation

Thirty raters were invited via e-mail to annotate pseudonymized cases on a web-based platform using structured questions. The goal was to recruit at least two readers from each center, each with a minimum of 5 years of experience in dermatoscopy. Finally, the median years of experience in dermatoscopy was 19 and 1 evaluator had a 2-year of experience. Further details on the collaborators and number of readers per center are available in Supplementary Table 20.

During registration, each reader provided information on age, sex, and years of experience in dermatoscopy. Subsequently, readers were granted access to the web-based platform, which contained only dermatoscopic images from different patients. For each new rating, the image was randomly selected from the dataset, prioritizing images with fewer ratings. Readers could skip a case if they perceived quality issues. The questionnaire included assessments of pigmentation, features and vessels (Supp. Fig. 1). There was no time limit for completing a case, and annotations were collected between the 21st of October 2023 and the 10th of March 2024.

Criteria for lesion evaluation

Dermatoscopic images were independently evaluated by human readers in a blinded manner, based on pre-specified criteria and according to established terminology38. Some criteria assessed the extent of a feature within the lesion, expressed in quantiles (0, 25, 50, 75, 100%), while others examined the presence or absence of specific features as binary variables. The dermatoscopic criteria included in the evaluation were as follows:

-

1)

Grade of pigmentation, ulceration, regression structures (ordinal variables)

-

2)

Colors: brown, black, blue/gray, red, and white (binary variables)

-

3)

Structures: white shiny streaks, blue-white veil, eccentric blotch, angulated lines, parallel ridge (binary variables)

-

4)

Extent of vascularity in the lesion (ordinal variable) and vessel type (dotted/coiled vessels and linear/irregular vessels)

A complete list of dermatoscopic variables and their possible values is shown in Supplementary Table 21.

Assessment of ratings from readers

Following the initial assessment, ratings from each reader were extracted in a pre-specified format for further analyses. The evaluation outcome on the presence or absence of a dermatoscopic feature was determined using a majority vote per image, based on the most common reader response. For patients with multiple dermatoscopic images of the primary tumor, two authors (K.L., A.L.) independently reviewed the images to assess whether they depicted the same or different areas of the tumor. Multiple images of the same area were treated as a single entry, with a majority vote approach applied to the combined assessments. For images depicting different tumor areas, a majority vote was first applied to each image separately. Then, based on the number of different images (n), each image was rated using the following approach:

Rate = (V1/n) + (V2/n) + …(Vn/n), where V1: is the majority vote for image 1, V2 is the majority for image 2, and n: number of different images per patient.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was to investigate the association between dermatoscopic features of primary melanoma and metastasis (number of patients of the total cohort=524). Metastasis was defined as any metastatic event occurring either at initial diagnosis or during subsequent follow-up, encompassing regional disease (i.e., in-transit and satellite metastases, sentinel lymph node biopsy positivity, or completion lymph node dissection positivity) and distant metastatic spread.

Secondary outcomes included developing a predictive model for metastasis based on dermatoscopy (Model 1) and comparing its diagnostic accuracy with a model incorporating established melanoma prognostic factors (i.e., Breslow thickness and ulceration) (Model 2), as well as a combined model integrating both dermatoscopic and histopathologic predictors (Model 3). An additional secondary outcome was the comparison of the accuracy of all three models in predicting RFS and DMFS in early-stage tumors at diagnosis (number of patients=381).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and categorical variables were summarized using frequencies. Interrater agreement was evaluated with Krippendorff’s alpha coefficient, interpreted according to the Landis and Koch classification57. Median follow-up time was estimated via the reverse Kaplan-Meier method. Group comparisons for continuous variables (Breslow thickness and age) used the Mann-Whitney U test. Associations between dermatoscopic features and melanoma metastasis were analyzed using χ² tests. We employed univariate and multivariable logistic regression models to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for metastasis risk and to develop predictive models based on dermatoscopic, clinical, or histologic predictors. Backward elimination was used for automated variable selection during model construction.

To further assess the predictive utility of dermatoscopy, we conducted Cox proportional hazards regression analyses exclusively in early-stage melanomas (AJCC stage IB–II), excluding cases with metastatic events at diagnosis. Study endpoints included recurrence-free survival (RFS), defined as the time from diagnosis to first metastasis, and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS), defined as the interval from diagnosis to distant metastatic spread. Hazard ratios (HRs) and survival probabilities were calculated, with model performance quantified using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC).

For robustness, logistic and Cox regression analyses were performed using a dataset split into training (80%) and test sets (20%), stratified by TNM stage, age, and sex. A 5-fold cross-validation approach was applied to the training set to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the three models, followed by independent validation in the test set. We used DeLong’s test to compare AUC values across models58. All statistical tests were two-sided, and analyses were conducted using R packages (R version 4.5.1) and IBM SPSS Statistics (v29.0).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Raw clinical data and dermatoscopic images are not publicly available due to lack of permission from data sources to have those data distributed to third parties. Access can be obtained for academic and research purposes by submitting a request to the corresponding author (A.L.), by email at alallas@auth.gr. Requests should include the applicant’s name, contact details, affiliation and the intended use of the data. The corresponding author is responsible to contact collaborating centers and initiate the data-sharing process. Applications will be evaluated based on institutional policies. Clinical data and digitally annotated dermatoscopic image will only be shared following necessary institutional approvals. For centers that cannot provide consent for data sharing, specific reasons will be communicated to the applicants. An initial response from the corresponding author is anticipated within one month of request submission and the final acceptance or not from collaborating centers will be provided within the next three months. All remaining data supporting this work are available in the main article, supplementary information or Source data File. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Analyses were performed in R with publicly available packages. R code used in DMFS calculation is available under MIT license on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17418482.

References

Keung, E. Z. & Gershenwald, J. E. The eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) melanoma staging system: implications for melanoma treatment and care. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 18, 775–784 (2018).

Kirkwood, J. M. et al. Adjuvant nivolumab in resected stage IIB/C melanoma: primary results from the randomized, phase 3 CheckMate 76K trial. Nat. Med 29, 2835–2843 (2023).

Luke, J. J. et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy in completely resected stage IIB or IIC melanoma (KEYNOTE-716): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 399, 1718–1729 (2022).

Whiteman, D. C., Baade, P. D. & Olsen, C. M. More people die from thin melanomas (⩽1 mm) than from thick melanomas (>4 mm) in Queensland, Australia. J. Invest Dermatol 135, 1190–1193 (2015).

Garbe, C. et al. Prognosis of patients with primary melanoma Stage I and II According to American Joint Committee on Cancer Version 8 validated in two independent cohorts: implications for adjuvant treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 3741–3749 (2022).

Lallas, K. et al. Clinical, dermatoscopic, histological and molecular predictive factors of distant melanoma metastasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 202, 104458 (2024).

Verver, D. et al. The EORTC-DeCOG nomogram adequately predicts outcomes of patients with sentinel node–positive melanoma without the need for completion lymph node dissection. Eur. J. Cancer 134, 9–18 (2020).

El Sharouni, M. A. et al. Development and Validation of Nomograms to Predict Local, Regional, and Distant Recurrence in Patients With Thin (T1) Melanomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 1243–1252 (2021).

Dixon, A. J. et al. BAUSSS biomarker further validated as a key risk staging tool for patients with primary melanoma. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 39, 779–781 (2024).

Amaral, T. et al. Identification of stage I/II melanoma patients at high risk for recurrence using a model combining clinicopathologic factors with gene expression profiling (CP-GEP). Eur. J. Cancer 182, 155–162 (2023).

Mulder, E. et al. Using a clinicopathologic and gene expression (CP-GEP) model to identify stage I-II melanoma patients at risk of disease relapse. Cancers 14, 2854 (2022).

Hsueh, E. C. et al. Long-term outcomes in a multicenter, prospective cohort evaluating the prognostic 31-gene expression profile for cutaneous melanoma. JCO Precis. Oncol. 5, 119 (2021).

Dinnes, J. et al. Dermoscopy, with and without visual inspection, for diagnosing melanoma in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 12, Cd011902 (2018).

Apalla, Z. et al. The light and the dark of dermatoscopy in the early diagnosis of melanoma: Facts and controversies. Clin. Dermatol. 31, 671–676 (2013).

Lallas, A. et al. Dermatoscopy of melanoma according to type, anatomic site and stage. Ital. J. Dermatol Venerol. 156, 274–288 (2021).

Filipović, N., Šitum, M. & Buljan, M. Dermoscopic features as predictors of BRAF mutational status and sentinel lymph node positivity in primary cutaneous melanoma. Dermatol. Pract. Concep. 11, e2021040 (2021).

De Giorgi, V. et al. Dermoscopy as a tool for identifying potentially metastatic thin melanoma: a clinical-dermoscopic and histopathological case-control study. Cancers 16, 1394 (2024).

Deinlein, T. et al. Dermoscopic characteristics of melanoma according to the criteria “ulceration” and “mitotic rate” of the AJCC 2009 staging system for melanoma. PLoS One 12, e0174871 (2017).

Saud, A., Sagineedu, S. R., Ng, H. S., Stanslas, J. & Lim, J. C. W. Melanoma metastasis: what role does melanin play? (Review). Oncol Rep 48, 217 (2022).

Sarna, M., Krzykawska-Serda, M., Jakubowska, M., Zadlo, A. & Urbanska, K. Melanin presence inhibits melanoma cell spread in mice in a unique mechanical fashion. Sci. Rep. 9, 9280 (2019).

Cabaço, L. C., Tomás, A., Pojo, M. & Barral, D. C. The Dark Side of Melanin Secretion in Cutaneous Melanoma Aggressiveness. Front Oncol. 12, 887366 (2022).

Tsoi, J. et al. Multi-stage differentiation defines melanoma subtypes with differential vulnerability to drug-induced iron-dependent oxidative stress. Cancer Cell 33, 890–904.e895 (2018).

Pozniak, J. et al. A TCF4-dependent gene regulatory network confers resistance to immunotherapy in melanoma. Cell 187, 166–183.e125 (2024).

Damsky, W. E., Rosenbaum, L. E. & Bosenberg, M. Decoding melanoma metastasis. Cancers 3, 126–163 (2010).

Fiddler, I. J. Melanoma metastasis. Cancer Control 2, 398–404 (1995).

Brodland, D. G. & Zitelli, J. A. Mechanisms of metastasis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 27, 1–8 (1992).

Skobe, M. & Detmar, M. Structure, function, and molecular control of the skin lymphatic system. J. Investig. Dermatol Symp. Proc. 5, 14–19 (2000).

Betti, R., Agape, E., Vergani, R., Moneghini, L. & Cerri, A. An observational study regarding the rate of growth in vertical and radial growth phase superficial spreading melanomas. Oncol. Lett. 12, 2099–2102 (2016).

Ciarletta, P., Foret, L. & Ben Amar, M. The radial growth phase of malignant melanoma: multi-phase modelling, numerical simulations and linear stability analysis. J. R. Soc. Interface 8, 345–368 (2011).

Guerry, D. T., Synnestvedt, M., Elder, D. E. & Schultz, D. Lessons from tumor progression: the invasive radial growth phase of melanoma is common, incapable of metastasis, and indolent. J. Invest Dermatol 100, 342s–345s (1993).

Vandyck, H. H. et al. Rethinking the biology of metastatic melanoma: a holistic approach. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 40, 603–624 (2021).

Pizzichetta, M. A. et al. Pigmented nodular melanoma: the predictive value of dermoscopic features using multivariate analysis. Br. J. Dermatol. 173, 106–114 (2015).

Longo, C. et al. Dermoscopy of melanoma according to different body sites: Head and neck, trunk, limbs, nail, mucosal and acral. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 37, 1718–1730 (2023).

Massone, C., Hofman-Wellenhof, R., Chiodi, S. & Sola, S. Dermoscopic criteria, histopathological correlates and genetic findings of thin melanoma on non-volar skin. Genes 12, 1288 (2021).

Barricklow, Z., DiVincenzo, M. J., Angell, C. D. & Carson, W. E. Ulcerated cutaneous melanoma: a review of the clinical, histologic, and molecular features associated with a clinically aggressive histologic phenotype. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol 15, 1743–1757 (2022).

Bønnelykke-Behrndtz, M. L. et al. Prognostic stratification of ulcerated melanoma: not only the extent matters. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 142, 845–856 (2014).

In ‘t Hout, F. E. et al. Prognostic importance of the extent of ulceration in patients with clinically localized cutaneous melanoma. Ann. Surg. 255, 1165–1170 (2012).

Yélamos, O. et al. Dermoscopy and dermatopathology correlates of cutaneous neoplasms. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 80, 341–363 (2019).

Lallas, A. et al. Accuracy of dermoscopic criteria for the diagnosis of melanoma in situ. JAMA Dermatol 154, 414–419 (2018).

Polesie, S. et al. Assessment of melanoma thickness based on dermoscopy images: an open, web-based, international, diagnostic study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol Venereol. 36, 2002–2007 (2022).

Pagnanelli, G. et al. Clinical and dermoscopic criteria related to melanoma sentinel lymph node positivity. Anticancer Res. 27, 2939–2944 (2007).

Aivazian, K. et al. Histological regression in melanoma: impact on sentinel lymph node status and survival. Mod. Pathol. 34, 1999–2008 (2021).

Ribero, S. et al. Association of histologic regression in primary melanoma with sentinel lymph node status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol 151, 1301–1307 (2015).

Maurichi, A. et al. Prediction of survival in patients with thin melanoma: results from a multi-institution study. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 2479–2485 (2014).

Subramanian, S. et al. Regression in melanoma is significantly associated with a lower regional recurrence rate and better recurrence-free survival. J. Surg. Oncol. 125, 229–238 (2022).

Gualano, M. R. et al. Prognostic role of histological regression in primary cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Dermatol 178, 357–362 (2018).

Wagner, N. B. et al. Histopathologic regression in patients with primary cutaneous melanoma undergoing sentinel lymph node biopsy is associated with favorable survival and, after metastasis, with improved progression-free survival on immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: a single-institutional cohort study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 90, 739–748 (2024).

Handerson, T. et al. Melanophages reside in hypermelanotic, aberrantly glycosylated tumor areas and predict improved outcome in primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. J. Cutan. Pathol. 34, 679–686 (2007).

Sgouros, D. et al. Dermatoscopic features of thin (≤2 mm Breslow thickness) vs. thick (>2 mm Breslow thickness) nodular melanoma and predictors of nodular melanoma versus nodular non-melanoma tumours: a multicentric collaborative study by the International Dermoscopy Society. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol Venereol. 34, 2541–2547 (2020).

Armengot-Carbó, M., Nagore, E., García-Casado, Z. & Botella-Estrada, R. The association between dermoscopic features and BRAF mutational status in cutaneous melanoma: significance of the blue-white veil. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 78, 920–926 (2018).

Lallas, K. et al. Prediction of melanoma metastasis using dermatoscopy deep features: an international multicentre cohort study. Br. J. Dermatol 191, 847–848 (2024).

Lee, R. et al. Adjuvant therapy for stage II melanoma: the need for further studies. Eur. J. Cancer 189, 112914 (2023).

Blank, C. U. et al. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Resectable Stage III Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 391, 1696–1708 (2024).

Patel, S. P. et al. Neoadjuvant-Adjuvant or Adjuvant-Only Pembrolizumab in Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 813–823 (2023).

Mervic, L. Time course and pattern of metastasis of cutaneous melanoma differ between men and women. PLoS One 7, e32955 (2012).

Meier, F. et al. Metastatic pathways and time courses in the orderly progression of cutaneous melanoma. Br. J. Dermatol 147, 62–70 (2002).

Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159–174 (1977).

DeLong, E. R., DeLong, D. M. & Clarke-Pearson, D. L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 44, 837–845 (1988).

Acknowledgements

We thank clinicians from collaborating centers who provided dermatoscopic images and clinical data of patients with melanoma. Also, we sincerely thank Dr. Athanassios Kyrgidis (from Aristotle University of Thessaloniki) for the methodological advice and input in statistical analysis plan. External funding or project-specific grants were not received to support this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.L., H.K., P.T. and A.L. conceived of and designed the overall study. H.K., P.T. and A.L. were responsible for the collection of dermatoscopic images from collaborating centers and for the reader study participant recruitment. P.T. developed the web-based interface for lesion evaluation. K.L., P.T. and A.L. conducted the reader study and data collection. K.L. performed the analysis with support from H.K., P.T. A.L. supervised the whole project and takes responsibility for the published data as well as all analyses conducted in combination with K.L. K.L. drafted the initial version of the manuscript. H.K., P.T., J.M., A.S., A.L., C.M., N.M.M., A.Mar., E.C.S., A.C., M.M.C., H.P.S., D.S., R.B., T.L., E.D., G.A., A.Mi, S.P., R.M.B., F.P., M.T., G.B., V.M., M.A., I.Z., L.T., H.C., C.V.A. and A.A. participated in human reader evaluation of dermatoscopic images. T.A., K.Li., W.S., E.V. and Z.A. provided clinical expertise and contributed to the interpretation of the results and critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

TA- TA reports personal fees for advisory board membership from Delcath and Philogen; personal fees as an invited speaker from Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Medscape, Neracare, Novartis and Pierre Fabre; personal fees for a writing engagement from CeCaVa and Medtrix; institutional fees as local principal investigator (PI) from Agenus Inc., AstraZeneca, BioNTech, BMS, HUYA Bioscience, Immunocore, IO Biotech, MSD, Pfizer, Philogen, Regeneron, Roche and University Hospital Essen; institutional fees as coordinating PI from Unicancer; institutional research grants from iFIT and Novartis; institutional funding from MNI - Naturwissenschaftliches und Medizinisches Institut, Neracare, Novartis, Pascoe, Sanofi and Skyline-Dx; non-remunerated membership of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the Portuguese Society for Medical Oncology; a role as clinical expert in the area of medical oncology for Infarmed, and a role as an expert for SGA-Oncology at EMA. These activities had no role in the study’s design, data acquisition, results interpretation and decision to submit. HPS- HPS is a shareholder of MoleMap NZ Limited and e-derm consult. GmbH and undertakes regular teledermatological reporting for both companies. HPS is a Medical Consultant for Canfield Scientific Inc and a Medical Advisor for First Derm. These activities had no role in the study’s design, data acquisition, results interpretation and decision to submit. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Lu Si, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lallas, K., Kittler, H., Tschandl, P. et al. Predictive models of melanoma metastasis based on dermatoscopy in an international retrospective human reader study. Nat Commun 16, 10940 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65972-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65972-w