Abstract

A special class of valleytronic two-dimensional (2D) semiconductors possesses carrier pockets (i.e., valleys) along certain directions in the first Brillouin zone, which can be applied as a new degree of freedom for information storage and processing. Here we show that members of this family that are ferroelectric allow the location of these valleys to be switched by rotating the ferroelectric polarization. This makes possible the control of electronic state transmission probability through an energy barrier by ferroelectrically switching the polarization direction, thereby creating or eliminating valley matching in reciprocal space. We apply molecular beam epitaxy to grow lateral sandwich heterostructures with monolayer-thick ferroelectric SnTe separated by nanometer-wide paraelectric PbTe as the barriers. Using scanning tunneling microscopy, we show that the transmission probability of the 2D hole states at the valence band maximum of SnTe monolayer strongly relies on the relative orientation between the polarization directions of the two SnTe electrodes. The transmission can be switched from a suppressed state to a permitted state by rotating the ferroelectric polarization of one SnTe electrode by 90 degrees. Our work demonstrates the electric-field-control of valley locations and its potential for tunnel junction valleytronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electronic valleys—the electron or hole pockets at the conduction band minimum (CBM) or valence band maximum (VBM) of semiconductors or semimetals that are located at certain positions in reciprocal space—are proposed as novel candidates for controlling the transmission probability through tunnel junctions1,2,3. Currently existing strategies for addressing the valley degree of freedom typically involve a selective quasiparticle population in different valleys in the Brillouin zone—namely a “valley polarization”—by external optical, electric or magnetic fields4,5,6,7. Hexagonal two-dimensional (2D) semiconductors like graphene and transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers (MLs), which have two valleys located at a pair of points linked by time reversal symmetry in the first Brillouin zone, are the most frequently recurred materials for valley polarization studies8,9,10,11,12,13,14. This is so because the quasiparticles in these two valleys bear Berry curvatures with opposite signs, and thus “pseudospins” can be defined at each valley7.

The effect presented here relies on the fact that the electronic valley degree of freedom can be utilized not only for the non-equilibrium states mentioned above, but also for equilibrium states as long as the positions of the valleys in reciprocal space can be controlled by changing the orientation of the first Brillouin zone, i.e. the orientation of the 2D crystal. A straightforward approach of realizing such a rotation is an in situ mechanical pushing by a local probe, which has been demonstrated in an atomic force microscope on a twisted bilayer of 2D materials15. Beyond mechanical manipulation, a recently discovered class of 2D ferroelectric semiconductors16,17, in which the locations of electronic valleys are tied to the direction of the electric polarization P, provides the possibility of electric-field-control of the valley polarization. A series of non-volatile devices utilizing such a ferroelectric valley-switching mechanism have been theoretically proposed, such as in CuInP2S6-MnPS3 ferroelectric-antiferromagnetic heterostructures18, ferroelectric 1 T”-MoS219, ferroelectric SnTe and bismuth monolayers with strong spin-orbit coupling20, as well as the vertical heterostructures between quantum spin Hall insulators Pt2HgSe3/Pd2HgSe3 and 2D ferroelectric materials with vertical P21. Furthermore, it is predicted that in bilayer graphene encapsulated with ferroelectric MoTe2, a small band gap can be opened or closed by tuning the polarization direction of MoTe2 between parallel and antiparallel22. However, the predictions above have not been experimentally demonstrated. Besides, most of the device designs focus on the valley-swapping effect induced by the 180° rotation of P, while the valley movement in the reciprocal space induced by a 90° rotation of P is still less discussed.

Here we report a valley-dependent transmission probability in a lateral sandwich heterostructure formed from MLs of ferroelectric SnTe23,24 separated by a 3-unit-cell-wide paraelectric PbTe ML barrier. State-of-the-art molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) methods are applied for the growth of SnTe-PbTe ML lateral superlattices with the width of a single material as small as 2 nm, enabling the lateral transmission of hole states. The change in transmission probability across the PbTe barrier at the permitted/suppressed states and the corresponding ferroelectrically-assisted crystal orientation switching are measured by in situ scanning tunneling microscopy (STM). This way, we provide a strategy for using the polarization in 2D ferroelectrics as an efficient handle for switching the locations of electronic valleys, which could be applied in future non-volatile devices.

Results

The principle of valley-dependent transmission

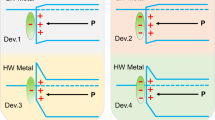

An electric-field-controlled valley-dependent transmission through a finite-height energy barrier is enabled by combining the growth of atomically narrow heterostructures and the local switching of crystal orientation in a multi-valley 2D material. Figure 1a shows the atomistic structure of a 2D SnTe-PbTe-SnTe ML lateral sandwich heterostructure. The paraelectric PbTe ML section has a tetragonal lattice while the ferroelectric SnTe MLs have orthorhombic structures and in-plane ferroelectricity. The interfaces of SnTe-PbTe ML heterojunctions preferentially form along the \(\left\langle 11\right\rangle\) directions and the in-plane polarization P of the SnTe ML makes an angle of ~45° with respect to the heterointerfaces. Using external electric fields, the orientation of P on SnTe MLs can point towards one of the four equivalent directions along \(\left\langle 10\right\rangle\).

a Atomistic structure of a SnTe-PbTe-SnTe ML lateral sandwich heterostructure with the intrinsic electric polarization P in the two SnTe ML sections perpendicular to one another. P can be switched between parallel and perpendicular orientations by an external electric field. Valley structures of SnTe (b) and PbTe (c) MLs. The gray planes represent the Fermi energy. The apex of the SnTe ML hole valleys along the Γ − X direction is slightly above the Fermi energy. d Type-II band alignment between SnTe and PbTe MLs. Transmission between the hole valleys of SnTe MLs is permitted (e) or suppressed (f) depending on the orientation of P in the SnTe ML sections at both sides of an ultra-narrow PbTe ML barrier.

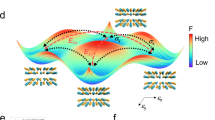

As a consequence of the lattice symmetries, the number and positions of the electronic valleys in the first Brillouin zones of SnTe and PbTe MLs are different (Fig. 1b, c). Both materials are p-type semiconductors when epitaxially grown on graphene surfaces; thereby we focus on the hole valleys that are close to the Fermi energy (EF). The four-fold rotational symmetry of a PbTe ML leads to four valleys along the four equivalent Γ−X directions. On the other hand, the non-centrosymmetric orthorhombic lattice of a SnTe ML has a mirror plane perpendicular to the x-y plane and parallel to the Γ−X direction. The lowered symmetry lifts the energy degeneracy of the hole valleys along the Γ−X and Γ−Y directions, placing the VBM along the Γ−X direction24,25,26. The energy difference between the apices of the hole bands along the Γ−X and Γ−Y directions is over 0.3 eV24. Because of the type-II band alignment (Fig. 1d) at the heterojunction interface of SnTe and PbTe MLs27, when EF is adjusted in between the VBMs of SnTe and PbTe in a SnTe-PbTe-SnTe ML sandwich heterostructure, the SnTe ML becomes a degenerately doped semiconductor while the PbTe ML section is insulating. Therefore, the PbTe ML section acts as a finite-height potential barrier between the two SnTe ML sections, as shown in Fig. 1e, f. The transmission probability of the hole states across this barrier is determined by the crystal orientation of the SnTe MLs on both sides of the barrier. The valleys are located at the same positions in reciprocal space on both sides of the barrier when the Γ−X directions of their Brillouin zones are parallel (Fig. 1e), and the hole states transmit directly. However, when the Γ−X directions of SnTe MLs on both sides are perpendicular to each other (Fig. 1f), the hole valleys on both sides of the barrier do not overlap in reciprocal space, and transmission cannot occur unless with the participation of a large momentum transfer process, hence the transmission probability is suppressed. In such a structure, the rotation of the first Brillouin zones of SnTe MLs can be simply accomplished by switching the direction of P with an external electric field.

It is worth noting that although the selective transmission described above realizes the switching behavior utilizing the in-plane ferroelectricity of SnTe MLs, its working principle is completely different from the existing ferroelectric tunnel junctions (FTJ). In a FTJ, a ferroelectric thin layer with P perpendicular to the interfaces is used as the tunnel barrier, inducing an electric potential imbalance between the two electrodes, which are usually composed of two types of metal with different work functions, or with a metal at one side and a semiconductor on the other side28,29. The ferroelectrically controlled valley-dependent transmission in this work requires no built-in electric field, and it can adopt the configuration of either lateral or vertical heterostructures. When the switching of P in one SnTe ML section occurs, the rotation of P preserves its component perpendicular to the interface and does not alter the charge distribution around the barrier, therefore the states with permitted or suppressed transmission are energetically degenerate. This is a potential advantage if this effect is applied in non-volatile tunnel junction devices in the future.

Ultra-narrow monolayer-thick lateral superlattices

The biggest challenge toward the creation of the aforementioned sandwich heterostructure is the growth of lateral superlattices with minimum line widths approaching the atomic scale so as to allow for robust transmission across the barrier. Lateral heterostructures between 2D materials have been grown using chemical vapor deposition (CVD) techniques for more than a decade30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40 but the minimal feature widths are still too large (over 10 nm)41,42 to enable significant transmission. Here, we have adopted MBE techniques with the capability of switching molecular fluxes on and off in a fraction of a second, to precisely control the width of each ML material section and the quality of the interfaces. Superlattices such as those shown in Fig. 2a–c are grown by adjusting the temperature of the graphene substrate and the SnTe/PbTe molecular beam fluxes from standard Knudson cells into a suitable parameter window, so that molecules adsorbed on the surface of SnTe or PbTe cannot nucleate but only form bonds when encountering the edges of the nanoplate, resulting in a horizontal growth mode (see Methods section for details).

a STM topographic image of a superlattice nanoplate (sample bias voltage Vs = 3.0 V, tunneling current I = 10 pA). The difference in the apparent height of SnTe and PbTe MLs originates from their type-II band alignment. The triangular-shaped higher area near the upper edge of the nanoplate is an atomic step on the SiC substrate. b Atom resolved image of a heterointerface with suppressed interdiffusion (Vs = −1.0 V, I = 10 pA). c STM topographic image of a superlattice with the width of a single wire as small as 2 nm (Vs = 1.5 V, I = 10 pA). d dI/dV spectra acquired at the positions indicated by the blue and red arrows in the inset image of (e), lying at the center of SnTe and PbTe ML sections, respectively. e Spatially resolved dI/dV spectrum with a seesaw pattern acquired along the dashed arrow in the inset. Spectra setpoints: Vs = 2.0 V, I = 100 pA for positive bias voltage and Vs = −0.9 V, I = 100 pA for negative bias voltage. Imaging setpoint for the inset: Vs = 3.0 V, I = 5 pA.

The type-II band alignment between SnTe and PbTe MLs, directly observed from the differential conductance (dI/dV) spectra acquired by STM in Fig. 2d, e, results in the different apparent heights in Fig. 2a–c that assist in distinguishing SnTe from PbTe27. By optimizing the growth conditions, the interfacial molecular diffusion can be confined to within ~1 nm (Fig. 2b), thus allowing for a minimum width of 2 nm for the tunnel barrier, equal to three lattice periods in the [11] direction (Figs. 1a, 2c). The dI/dV spectra acquired along a straight line perpendicular to the superlattice interfaces reveal alternating positive and negative bound charges at the interfaces, resulting in seesaw-shaped band edges (Fig. 2e). Measurements at the center of each SnTe or PbTe ML section reveal that the CBM and VBM of SnTe MLs are 0.42 and 0.37 eV higher than those of the PbTe ML, respectively, in agreement with previous results27. The hole band of the SnTe ML undergoes further lateral confinement near EF in the superlattice induced by the PbTe ML barrier, forming a series of one-dimensional (1D) bands shown in Fig. 2e. The type-II band alignment can also be observed from spatially resolved dI/dV spectra acquired at room temperature (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Information).

Electronic state transmission determined by crystal orientation

Now we experimentally demonstrate the valley-dependent transmission with the dual-junction heterostructure shown in Fig. 3a, which has five lateral sections. Sections I and V can be considered as “semi-infinite” SnTe MLs given that they are wider than the coherence length of the hole states close to the VBM, while sections II and IV are 2-nm wide PbTe ML barriers. Section III is a 10 nm wide SnTe ML nanowire, whose polarization direction is parallel to that of section I and perpendicular to that of section V. The dI/dV spectra across a similar dual-junction heterostructure is presented in Fig. 3b. We observe the formation of the first- and second-order 1D bound states induced by the confinement of PbTe barriers in section III, and standing waves of 2D hole states due to reflection at the PbTe ML barriers in sections I and V. Note that the VBM of SnTe in Fig. 3b is higher than that in Fig. 2e due to the thickness of the few-ML graphene substrate. On a bilayer graphene substrate, the VBM of a SnTe ML is 50 meV below EF, while on a trilayer graphene substrate, its VBM is 26 meV above EF, making the SnTe ML a degenerately doped semiconductor. This VBM shift is most likely because of differences in surface work function among few-layer graphene substrates. Indeed, multiple previous experimental studies conclude that the work function of epitaxial graphene on SiC tends to monotonically increase as the thickness of graphene increases43,44,45. This is consistent with our dz/dV measurements, which suggest that the work function of bilayer graphene is 0.19 eV higher than that of monolayer graphene (see Fig. S2 in Supplementary Information). Our first principles calculation shows that the work function of free-standing SnTe ML is slightly lower than those of bilayer and trilayer graphene27, hence there is a stronger electron transfer from SnTe to trilayer graphene, resulting a higher VBM. We also notice that the LDOS at the EF of the SnTe ML grown on trilayer graphene is mildly suppressed, which is likely due to the enhanced band hybridization at EF in this low-dimensional electron system.

a STM topography image of a SnTe-PbTe-SnTe-PbTe-SnTe ML dual-junction structure. 2 nm wide PbTe ML sections are laterally inserted into a SnTe ML as barriers. The five sections are labeled by Roman symbols I through V (Vs = −1.1 V, I = 100 pA). b Spatially resolved dI/dV spectrum (lower panel) acquired along a straight line perpendicular to the junctions shown in the upper panel, at the temperature of 0.4 K. (Spectra setpoint: Vs = −0.2 V, I = 100 pA.) A pair of red arrows indicate the energy at which the standing waves in section I are interrupted. c Schematic of the electronic states and corresponding transmission probabilities in this dual-junction structure. Thicker curled double-head arrows indicate a higher transmission probability. d Simulated local density of states (LDOS) obtained from a single-particle quantum well model (see “Methods” section for details). The barriers in sections II and IV are set as finite and infinite, respectively. e Schematic of the spatial dependence of dI/dV intensity at a certain energy Vs, as well as the definition of the effective barrier positions xb(Vs), and the intensity of standing waves in section I (\({\Delta }_{\parallel }\)) and section V (\({\Delta }_{\perp }\)). f Energy dependence of xb(Vs) at the two PbTe barriers, obtained by extrapolating the standing waves in the sections I and V. The error bars are obtained from the uncertainties of peak positions with a Gaussian fitting. g Bias voltage dependence of the standing wave intensities (upper panel) and the transmission probability 1 − \({\Delta }_{\parallel }/{\Delta }_{\perp }\) (lower panel). The error bars are obtained from the uncertainties of peak intensities with a Gaussian fitting.

The different transmission probabilities of wavefunctions at the two tunnel barriers can be resolved as follows. The standing wave in section I shows a significant shift along the x axis at −90 meV (see horizontal red arrows in Fig. 3b); this is the energy at which the second-order 1D bound state emerges in section III. On the other hand, the standing wave is continuous at any energy in section V. Those are manifestations of a finite transmission probability between sections I and III, and of a suppressed transmission between sections III and V. As Fig. 3c illustrates, because of the 90° rotation between the first Brillouin zones of sections III and V, the hole valleys are not matched in momentum space, thus opposite sides of the interface are equivalent to semi-infinite “vacuum” regions, with the vacuum boundary lying exactly at the PbTe ML barrier. Therefore, the standing wave of the hole states in section V behaves like that in a standard 1D semi-infinite square potential well. On the other hand, given that the first Brillouin zone orientations are identical in sections I and III, their hole states have a finite probability to transmit through the PbTe ML barrier, whose equivalent width has a strong energy dependence. Figure S3 showcases another example on a bilayer graphene substrate, where the standing waves display similar polarization-tuned transmission behaviors. The transmission effect in Fig. S3 is less prominent than that on trilayer graphene in Fig. 3b because the VBM of SnTe ML is lower when on bilayer graphene, and the transmission features are farther away from EF under those conditions (the apices of the second order 1D sub-bands are at −90 meV and −160 meV for SnTe on trilayer and bilayer graphene, respectively), thus making the lifetime of the quasiparticles shorter. Furthermore, to explore the extreme superlattice period, we examined a superlattice structure in which the width of each SnTe and PbTe section is only 1.1 nm (Fig. S4). The transmission between neighboring SnTe sections is so strong that the whole superlattice area forms an overall standing wave pattern near the VBM, rather than separated patterns in each section. Comparing this result with the standing wave patterns in Fig. 3b, we can safely conclude that a SnTe section width of ~10 nm and PbTe barrier width of 2 nm can form strong enough quantum confinement for a significant transmission probability switching.

The interruption of the standing waves in section I of Fig. 3b can be understood from the LDOS [G(E)] of the 1D hole states in section III, described by \(G\left(E\right)\propto {[-\left(E-{E}_{0}\right)]}^{-1/2}\), where E0 is the energy of the band edge, making constant LDOS contours appear as the inverted triangles shown in Fig. 3c. Therefore, starting from the VBM of section III, the LDOS of bound states decreases as the energy decreases, while the equivalent barrier width between sections I and III increases, causing the center position of the barrier to gradually shift towards the center of section III. G(E) suddenly increases and the equivalent barrier width narrows down at −90 meV as the next 1D bound state appears, making the center location of the barrier jump back towards section I, for a discontinuity in the standing wave in that section. An analytical model with a square potential well and a finite-height barrier inside reproduces the phenomenon of standing wave interruption (see Figs. 3d, S5, S6 and S7 for details of the model). For simplicity, this model adopts a 1D particle-in-a-box regime, in which the effective barrier also becomes narrower at the energies a new order of standing wave appears in section III. Transmission of the first order of the 1D hole states in section III can also be observed from the simulation, but because of the relatively wider effective barrier width, the transmission intensity is too weak hence can only be clearly seen in a magnified figure (Fig. S7). In the simulation, it can also be seen that the finite transmission probability induces LDOS maxima that locate at the same energies in sections I and III, especially in the range between −0.1 and −0.2 eV. No evidence of transmission is found between sections III and V.

Using data from Fig. 3b, we extract the variation of the dI/dV intensity along x at each bias voltage Vs and determine the locations of xb(Vs), the standing wave node closest to section III, which can be considered as the effective barrier positions. This is done by extracting the period of the standing wave at each energy, and then the location of the first maximum (Fig. 3e, S8 and S9). As the energy decreases, xb first moves towards the center of section III, and it suddenly jumps towards section I by −2.6 nm at −90 meV (Fig. 3f). In contrast, the location of xb between sections III and V is independent of energy, implying the absence of quasiparticle transmission at this barrier. Similar results can also be observed from the simulated standing wave patterns (Figs. S6 and S7).

The energy dependence of the transmission probability between sections I and III (Fig. 3g) is analyzed next. To do so, we extract the standing wave intensity in sections I and V as a function of energy, denoting them as \({\Delta }_{\parallel }(E)\) and \({\Delta }_{\perp }(E)\) when the polarization is parallel (\(\parallel\)) or perpendicular (\(\perp\)) across the two interfaces (Fig. 3e), respectively. \({\Delta }_{\parallel }\) was always smaller than \({\Delta }_{\perp }\), implying a finite transmission between sections I and III at any energy near the VBM, which is positively correlated with G(E) at the corresponding energy in section III. The stronger the transmission at a certain energy, the weaker the corresponding reflection, thus the standing wave intensity in section I is suppressed at that energy. A similar phenomenon was reported in a study of the transmission of topological surface states of Sb single crystals through atomic steps46. Since there is no observable transmission between sections III and V, \({\Delta }_{\perp }(E)\) is the standing wave intensity when all the waves are reflected (neglecting the absorption at the interface), and \(1-{\Delta }_{\parallel }/{\Delta }_{\perp }\) is the ratio of the transmission probability to the sum of the reflection and transmission probabilities at the interface between sections I and III. Figure 3g shows that \(1-{\Delta }_{\parallel }/{\Delta }_{\perp }\) has the maxima of 0.88 and 0.86 at −90 meV and −190 meV, respectively, corresponding to the energies of the maximum LDOS in section III—the apex of the second- and third-order 1D bound states.

Ferroelectric switching of the transmission probability

Now we demonstrate that the transmission probability of the hole states can be switched by manipulating the in-plane polarization of the SnTe sections beside a PbTe barrier. We manipulate the ferroelectric domains in SnTe by applying a slow-changing electric field at a large enough tip-sample distance such that no tunneling current occurs (see Supplementary Information for details). The electric field between the STM tip and the sample is mostly in the vertical direction, but there is a finite horizontal component due to the conical shape of the tip (Fig. S10), enabling the movement of domain walls. In Fig. 4, we collected the dI/dV spectra at the same place of a dual-junction structure before and after a 90° switching of the polarization in the narrow SnTe section. The movement of domain walls can be resolved from the change of moiré pattern distribution (Fig. 4a, b). Initially, the polarization directions in the two SnTe sections are perpendicular to each other, and no sign of transmission can be observed (Fig. 4c). (See Fig. S11 for details of the method for the determination of polarization direction, and Fig. S12 for additional demonstrations of polarization switching.) After the switching, an interruption of the standing waves in the wider SnTe section at the energy corresponding to the apices of the second order of 1D bound states in the narrow SnTe section (−0.18 eV) is observed (Fig. 4d), similar as the data in Fig. 3b. We performed xb analysis to the standing waves in Fig. 4d, which yields a spatial jump of 1.5 nm, while the xb in Fig. 4c shows no observable spatial dependence. Being consistent with the results in Fig. 3f, these results confirm that a local polarization direction switching can effectively tune the transmission probability through a PbTe barrier.

Topography images of an area with a dual-junction before (a) and after (b) a switching operation (Vs = 1.6 V, I = 10 pA for both images). The dashed lines indicate the ferroelectric domain walls, some of which overlap with the PbTe barriers. c,d Spatially resolved dI/dV spectra collected along the dotted arrows in (a,b), respectively. (Spectra setpoint: Vs = −0.4 V, I = 200 pA for (c), and Vs = −0.3 V, I = 400 pA for d). The path for acquiring the spectra crosses a PbTe barrier, beside which the polarization are perpendicular (parallel) to each other before (after) the switching. The overlaid red dots indicate the positions of effective barrier extracted from the electronic standing waves in section V. The error bars adopt the same definition as those in Fig. 3f.

Discussion

The lateral sandwich structure with ferroelectrically switchable electronic state transmission probability can potentially be developed into a valley tunnel junction (VTJ) device. This work has demonstrated the valley-dependent hole state transmission principle in such a sandwich structure, while future experiments are needed to verify the switching of electric resistance in a real VTJ device. Its lateral configuration has an additional advantage: since the equivalent tunnel junction width has a strong energy dependence, EF could in principle be tuned through vertical gate electrodes to realize a non-volatile tunnel junction device with adjustable tunnel resistance, which is not possible in ferroelectric tunnel junctions with vertical heterostructures. When a small reading voltage is applied across a VTJ device, the potential of the two electrodes is nearly the same, hence the tunneling current is roughly proportional to the density of states at the electrodes’ EF. Besides, the working principle of this class of VTJs can also be easily generalized to vertical structures. Furthermore, based on the technique of growing nanometer-scale lateral heterostructures, it is also possible to create low-dimensional states useful for quantum devices, such as 1D topological superconducting states and quantum dot arrays for quantum computing.

Methods

Growth of the lateral heterostructures and superlattices

Experiments were carried out in a Unisoku USM1300 MBE-STM combined system. The base pressure was lower than 2 × 10−10 mbar in the MBE chamber, and below 1 × 10−10 mbar in the STM chamber. The substrates were prepared by a two-step annealing treatment of phosphorus-doped, Si-terminated 4H-SiC(0001) single crystals in an UHV environment, which were heated by passing direct current through 2 mm × 10 mm-sized substrates. The SiC substrate was annealed at 900 °C in a Si molecular flux for 15 min, so that atomic terraces and a Si-rich (3 × 3) reconstruction are formed. The substrate was subsequently annealed at 1450 °C for 6 min to generate a surface mainly covered by bilayer and trilayer graphene. PbTe and SnTe molecular fluxes were obtained by heating 99.999% PbTe and SnTe granules (from Alfa Aesar) in standard Knudsen cells (from GC Inno) with water cooling and shutters. PbTe ML cores were grown at a substrate temperature Tsub ~ 180 °C using a PbTe evaporation temperature TPbTe = 460 °C. Growth times t varied between 1 min and 10 min, depending on the desired core size, which was adjusted from feedback provided by STM topographic images. The lateral heterostructures and superlattices were grown by sequentially depositing PbTe and SnTe. Knudsen cells were kept at fixed evaporation temperatures and the beam fluxes were turned on or off with shutters. The growth parameters were tuned to find the optimal window such that (i) the substrate temperature is high enough so that no nucleation happens on the surface of SnTe or PbTe and a lateral growth mode is enabled, and (ii) the substrate temperature is as low as possible to minimize interfacial diffusion and defect concentration. The optimized parameters for growing the lateral heterostructures in our system were Tsub ~ 150 °C, TPbTe = 460 °C, and TSnTe = 440 °C. The lateral growth rates of PbTe and SnTe MLs were 0.40 nm/s and 0.33 nm/s, respectively.

Scanning tunneling microscopy characterization

Low-temperature STM experiments were performed in situ in an ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) environment. Measurements were carried out with mechanically sharpened Pt-Ir alloy tips that were calibrated on Ag(111) surfaces. Samples were kept at 4.7 K unless otherwise specified. Differential conductance dI/dV spectra were acquired with the built-in lock-in amplifier in the Nanonis STM controller with a modulation frequency of 913 Hz. The polarization direction in each section of SnTe ML was determined by combining the longer extracted lattice parameter (a1) and the band bending directions at the free edges of SnTe ML, as illustrated in Fig. S11.

Ferroelectric domain wall manipulation

The manipulation of ferroelectric domain walls was performed with a procedure illustrated in Fig. S10. First, we keep the feedback loop of the STM tip closed and move the tip to an initial position on the graphene area beside the edge of the nanoplate, as the red circles in Fig. 4 indicate. The bias voltage and tunneling current are set to normal scanning values, typically 1.8 V, 20 pA. We open the feedback loop to freeze the location of the tip, and raise it by 1 nm subsequently. Any tunneling current should have vanished at this height. Next, we keep the tip at this height and increase the bias voltage to 10 V and stay at this value for 10 s. Since this voltage exceeds the work function of the tip, a field emission current of several nA can be observed. Finally, the bias voltage is decreased back to the normal scanning value 1.8 V, and the feedback loop is closed again. We scan the area of interest after each operation to inspect whether the domain configuration was altered.

Simulation of electronic standing waves

The tunneling features observed in Fig. 3b were reproduced with a one-dimensional potential well model described in Fig. S5. Since transmission between sections of SnTe MLs with orthogonal polarizations is suppressed due to electronic valley mismatch, the PbTe ML section between them is modeled as a potential barrier of infinite height, and thus only the SnTe ML sections with parallel polarizations are modeled. We expand the wavefunctions using, as a basis, states in a 1D well of width L. The eigenstates and eigenenergies of these infinite wells are \({\phi }_{n}=\sqrt{\frac{2}{L}}\sin \left(\frac{n\pi x}{L}\right)\) and \({E}_{n}=\frac{{n}^{2}{\pi }^{2}{\hslash }^{2}}{2\vert{m}^{*}\vert{L}^{2}}\), respectively, where m* is the hole effective mass at the VBM of SnTe first principles calculations give |m*| = 0.12 me, where me is the bare electron mass24. The paraelectric PbTe ML between the SnTe ML sections with parallel polarization directions was modeled by a barrier with height V0 and width L2, centered at \(L-{L}_{1}-\frac{{L}_{2}}{2}\) inside the SnTe ML well. The potential of this barrier plus the infinitely long interfaces separating SnTe ML sections with different polarizations can be included in a position dependent potential V(x). The complete Hamiltonian is H0 + V(x) and we look for the solutions of \(\left[{H}_{0}+V\left(x\right)\right]{\psi }_{n}={\epsilon }_{n}{\psi }_{n}\), where \({H}_{0}=-\frac{{\hslash }^{2}}{2\vert{m}^{*}\vert}\frac{{d}^{2}}{{{dx}}^{2}}\). We expand \({\psi }_{n}={\varSigma }_{s=1}^{{s}_{\max }}{a}_{{sn}}{\phi }_{s}\) and choose a smax large enough to guarantee numerical convergence. The solutions are found by solving the secular equation:

with matrix elements given by:

where \({\delta }_{{ps}}\) is the Kronecker delta. For simplicity, the quantities a = L − L1 − L2 and b = L − L1, defining the boundaries of the PbTe ML potential barrier are introduced into the last equation (see Fig. S5). The LDOS is written as:

We used the representation \(\delta \left(x\right)=\frac{\eta }{\pi }\frac{1}{{\eta }^{2}+{x}^{2}}\) for the Dirac delta function (\(\eta\) is a small positive number, with units of energy, that gives the broadening of the localized states inside the well). The results of the simulations are shown in Fig. 3d of the main text. The parameters used are L1 = 10 nm, L2 = 2 nm, L = 85 nm, V0 = 0.18 eV, corresponding to a PbTe ML barrier of width 2 nm, located 74 nm away from the well’s left end. We used pmax = 160. The LDOS in section (ii) is that of a potential well without any PbTe ML barrier in it. As seen in Fig. 3d, section (III) develops localized states. The second order bound state appears at around −0.092 V in region (III). States from region (I) scatter through the barrier taking advantage of this state. The simulated G(E) exhibits a discontinuity, akin to the one observed experimentally (Fig. 3c) at this energy. This is a signature of a finite transmission through the PbTe ML barrier in the tunnel junction.

Data availability

All the data generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare database https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30454919.

Code availability

The code for the quantum well model simulation has been deposited in the Figshare database https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30454919.

References

Wang, D., Huang, Z., Zhang, Y. & Jin, G. Spin-valley filter and tunnel magnetoresistance in asymmetrical silicene magnetic tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. B 93, 195425 (2016).

Hajati, Y., Alipourzadeh, M. & Makhfudz, I. Spin- and valley-polarized transport and magnetoresistance in asymmetric ferromagnetic WSe₂ tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. B 103, 245435 (2021).

Zhang, S.-H. et al. Tunneling valley Hall effect driven by tilted Dirac fermions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 246301 (2023).

Rycerz, A., Tworzydlo, J. & Beenakker, C. W. J. Valley filter and valley valve in graphene. Nat. Phys. 3, 172–175 (2007).

Xiao, D., Yao, W. & Niu, Q. Valley-contrasting physics in graphene: magnetic moment and topological transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 236809 (2007).

Xiao, D., Liu, G.-B., Feng, W., Xu, X. & Yao, W. Coupled spin and valley physics in monolayers of MoS₂ and other group-VI dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 196802 (2012).

Xu, X., Yao, W., Xiao, D. & Heinz, T. F. Spin and pseudospins in layered transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Phys. 10, 343–350 (2014).

Mak, K. F., He, K., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Control of valley polarization in monolayer MoS₂ by optical helicity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 494–498 (2012).

Zeng, H., Dai, J., Yao, W., Xiao, D. & Cui, X. Valley polarization in MoS₂ monolayers by optical pumping. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 490–493 (2012).

Cao, T. et al. Valley-selective circular dichroism of monolayer molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Commun. 3, 887 (2012).

Srivastava, A. et al. Valley Zeeman effect in elementary optical excitations of monolayer WSe₂. Nat. Phys. 11, 141–147 (2015).

Aivazian, G. et al. Magnetic control of valley pseudospin in monolayer WSe₂. Nat. Phys. 11, 148–152 (2015).

Mak, K. F., McGill, K. L., Park, J. & McEuen, P. L. The valley Hall effect in MoS₂ transistors. Science 344, 1489–1492 (2014).

Li, J. et al. A valley valve and electron beam splitter. Science 362, 1149–1152 (2018).

Ribeiro-Palau, R. et al. Twistable electronics with dynamically rotatable heterostructures. Science 361, 690–693 (2018).

Wang, C., You, L., Cobden, D. & Wang, J. Towards two-dimensional van der Waals ferroelectrics. Nat. Mater. 22, 542–552 (2023).

Barraza-Lopez, S., Fregoso, B. M., Villanova, J. W., Parkin, S. S. P. & Chang, K. Colloquium: physical properties of group-IV monochalcogenide monolayers. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 011001 (2021).

Hu, H., Tong, W., Shen, Y. & Duan, C. Electrical control of valley degree of freedom in 2D ferroelectric/antiferromagnetic heterostructures. J. Mater. Chem. C. 8, 8098–8106 (2020).

Huang, K., Samanta, K., Shao, D.-F. & Tsymbal, E. Y. Two-dimensional nonvolatile valley spin valve. ACS Nano 19, 3448–3454 (2025).

Tao, L. L., Dou, M., Wang, X. & Tsymbal, E. Y. Ferroelectric spin-orbit valve effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 076801 (2025).

Rehman, M. U., Kiani, M. & Wang, J. Jacutingaite: an efficient platform for coexistence of spin valley Hall effects, valley spin-valve realization, and layer spin crossover. Phys. Rev. B 105, 195439 (2022).

Fumega, A. O. & Lado, J. L. Ferroelectric valley valves with graphene/MoTe2 van der Waals heterostructures. Nanoscale 15, 2181 (2023).

Chang, K. et al. Discovery of robust in-plane ferroelectricity in atomic-thick SnTe. Science 353, 274 (2016).

Chang, K. et al. Standing waves induced by valley-mismatched domains in ferroelectric SnTe monolayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 206402 (2019).

Rodin, A. S., Gomes, L. C., Carvalho, A. & Castro Neto, A. H. Valley physics in tin (II) sulfide. Phys. Rev. B 93, 045431 (2016).

Hanakata, P. Z., Carvalho, A., Campbell, D. K. & Park, H. S. Polarization and valley switching in monolayer group-IV monochalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 94, 035304 (2016).

Chang, K. et al. Vortex-oriented ferroelectric domains in SnTe/PbTe monolayer lateral heterostructures. Adv. Mater. 33, 2102267 (2021).

Wen, Z., Li, C., Wu, D., Li, A. & Ming, N. Ferroelectric-field-effect-enhanced electroresistance in metal/ferroelectric/semiconductor tunnel junctions. Nat. Mater. 12, 617–621 (2013).

Garcia, V. & Bibes, M. Ferroelectric tunnel junctions for information storage and processing. Nat. Commun. 5, 4289 (2014).

Ci, L. et al. Atomic layers of hybridized boron nitride and graphene domains. Nat. Mater. 9, 430 (2010).

Levendorf, M. P. et al. Graphene and boron nitride lateral heterostructures for atomically thin circuitry. Nature 488, 627 (2012).

Liu, Z. et al. In-plane heterostructures of graphene and hexagonal boron nitride with controlled domain sizes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 119 (2013).

Liu, L. et al. Heteroepitaxial growth of two-dimensional hexagonal boron nitride templated by graphene edges. Science 343, 163 (2014).

Duan, X. et al. Lateral epitaxial growth of two-dimensional layered semiconductor heterojunctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 1024 (2014).

Gong, Y. et al. Vertical and in-plane heterostructures from WS₂/MoS₂ monolayers. Nat. Mater. 13, 1135 (2014).

Li, M. Y. et al. Epitaxial growth of a monolayer WSe₂–MoS₂ lateral p–n junction with an atomically sharp interface. Science 349, 524 (2015).

Zhang, Z. et al. Robust epitaxial growth of two-dimensional heterostructures, multiheterostructures, and superlattices. Science 357, 788 (2017).

Sahoo, P. K., Memaran, S., Xin, Y., Balicas, L. & Gutiérrez, H. R. One-pot growth of two-dimensional lateral heterostructures via sequential edge-epitaxy. Nature 553, 63 (2018).

Zhao, M. et al. Large-scale chemical assembly of atomically thin transistors and circuits. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 954 (2016).

Shi, E. et al. Two-dimensional halide perovskite lateral epitaxial heterostructures. Nature 580, 614 (2020).

Kobayashi, Y. et al. Continuous heteroepitaxy of two-dimensional heterostructures based on layered chalcogenides. ACS Nano 13, 7527 (2019).

Herbig, C. et al. Local electronic properties of coherent single-layer WS₂/WSe₂ lateral heterostructures. Nano Lett. 21, 2363 (2021).

Hibino, H. et al. Dependence of electronic properties of epitaxial few-layer graphene on the number of layers investigated by photoelectron emission microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 79, 125437 (2009).

Renault, O. et al. Charge spill-out and work function of few-layer graphene on SiC(0001). J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 47, 295303 (2014).

Mammadov, S. et al. Work function of graphene multilayers on SiC(0001). 2D Mater. 4, 015043 (2017).

Seo, J. et al. Transmission of topological surface states through surface barriers. Nature 466, 343–346 (2010).

Acknowledgements

K.C., Z.G., R.-Q.C., W.W., C.Y. and C.L. are supported by Quantum Science and Technology—National Science and Technology Major Project (2023ZD0300500, K.C.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 92165104, K.C.; 12074038, K.C.; 12304206, W.W.; and 12204046, C.L.), and Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (Grant No. Z221100002722013, K.C.). J.-R.J. and S.S.P.P. acknowledge funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – project no. 443406107, S.S.P.P.; Priority Program (SPP) 2244, S.S.P.P.; European Union, FUNLAYERS, project number 101079184, S.S.P.P. A.H.G. and S.B.-L. acknowledge financial support from the U.S. Department of Energy (DE-SC0022120, S.B.-L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.C. designed and initialized the experiments. J.-R.J., Z.G., R.-Q.C., W.-L.W. and C.Y. conducted the MBE experiments. Z.G., R.-Q.C., W.-L.W. and C.Y. carried out the low-temperature STM experiments. Z.G., C.L. and K.C. analyzed the electronic state transmission in the dual-junction structure. Z.G. and R.-Q.C. performed the ferroelectric domain wall manipulation experiments. A.H. and S.B.L. conducted the quantum well simulation. K.C., S.B.-L. and S.S.P.P. supervised the project and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jeison Fischer and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, K., Ji, JR., Gao, Z. et al. Ferroelectrically switched valley-dependent transmission in SnTe-PbTe-SnTe monolayer lateral heterostructures. Nat Commun 16, 11063 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66005-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66005-2