Abstract

Chemists have a strong language describing and defining idealized polyhedra P and symmetry point groups G, but no efficient measure to correlate these to real molecular structures Q. The Continuous Symmetry operation Measure changes this by providing automated symmetry determination and a yardstick for quantifying deviations from symmetry. Symmetry and structure have been ascribed through experience, but this approach is error-prone and provides no measure that can correlate molecular structure to molecular properties. The Continuous Symmetry operation Measure tool solves this issue as it can quantify the symmetry of any structure that can be described as a list of points in space. Here, we compare the Continuous Symmetry Measure, the Continuous Shape Measure, and the Continuous Symmetry operation Measure approaches and demonstrate how the Continuous Symmetry operation Measure can be used as a tool to determine the molecular structure, the coordination geometry, and the symmetry of water, organic molecules, transition metal complexes, and lanthanide compounds. We conclude that the Continuous Symmetry operation Measure is not limited by any of the restrictions present in the other methods and allows a detailed analysis of e.g. phase changes and luminescence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The atomic composition and structure determine the chemical and physical properties of any material. This statement would appear trivial, and in chemistry we always define the constitution and conformation of compounds. However, the actual structure—which we refer to as the molecular structure—is frequently generalized broadly using hybridization in organic chemistry and coordination polyhedra in inorganic chemistry and materials science. Often, this generalization is lacking. The electronic structure and the chemical properties are determined by symmetry, and we propose that new tools now allow chemistry to move from generalized structures to exact molecular structures of identified symmetry1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8.

In chemistry, symmetry considerations are common. Electronic structures of organic molecules are simplified using group theoretical considerations. Similarly, the intricacies of metal complexes are reduced using symmetry in the framework of crystal field and ligand field theory. This allows electronic transitions to be calculated and experimental spectra to be assigned9,10,11,12. Further, symmetry dictates whether electronic transitions are allowed or forbidden13,14, which in turn enables the design of molecules with intricate photophysical properties15,16,17,18,19. In general, symmetry reduces the complexity of structure determination, and can be used as a decisive argument when creating structure-property relationships.

To identify and determine symmetry, we must agree on several premises. First, we must lock an axis for each symmetry under consideration20. Second, we must determine how much of a compound that must be included in the molecular structure, for the molecular structure to be true21. And finally, we must agree on a yardstick for determining symmetry and then start using it. Here, we investigate symmetry in the molecular structure of water, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), classical transition metal complexes, single molecule magnets, and lanthanide complexes. The level of detail that we go to has recently been reviewed with a focus on molecular conformations and polymorphs22, where our focus is on the minute structural details that determine the properties of lanthanide complexes. Here, we illustrate this using neodymium(III) and europium(III) electronic structure and luminescence.

Defining structure

We define a molecular structure as a set of atomic coordinates that gives rise to a specific electronic structure. In some cases, the electronic structure is maintained across variations in the atomic coordinates23,24,25. In other cases, minute changes in atomic coordinates changes the electronic structure, and each set of atomic coordinates is a separate molecular structure. A molecular structure thus by definition gives rise to a molecular entity as per the IUPAC Gold Book. Do note that a molecular entity can have several molecular structures23.

The distinction between molecular entities may appear ethereal, but in fact it is a highly relevant across chemistry. Structure-property relationships require determination of distinct structures. Seemingly simple molecules such as water H2O, become complex when more than a few molecules are involved26,27. Agglomerates of water molecules form different molecular entities with distinct properties28,29, and the complexity is increased further in bulk water H2O30,31,32,33,34, and if water interacts with surfaces35,36. Even in the solid state, the individual water molecules form several molecular entities that are different across the various forms of ice37,38,39. Each molecular entity is defined by symmetry.

Similarly, the structure of nanotubes and Buckminsterfullerenes are defined by symmetry as they exist in various constitutions40,41,42,43, mainly differentiated by symmetry1,41,42,43,44. For these carbon allotropes the differences are pronounced45, but for all organic molecules that are identified using NMR, the symmetry of the molecular structure must be known to interpret the spectrum.

From the earliest models of the electronic structure of transition metal complexes and metal clusters symmetry arguments have been used46,47,48, also the metal centers in metalloproteins are differentiated by symmetry49. Where crystal field theory fully establishes the theoretical basis for symmetry in the description of coordinating atoms and the electronic structure50,51,52, the molecular structure is not as easily defined. Jahn-Teller effects reduces otherwise ‘perfect symmetry’, and it has been reported repeatedly that tools like the Continuous Shape Measure (CShM) do not work in these cases53. That the symmetry of the transition metal compounds is important is clear in magnetic materials and from measurements using e.g., EPR and Mössbauer spectroscopy11,54,55,56,57,58,59. Even high energy X-ray spectroscopies rely on symmetry considerations when modeling the experimental results60,61.

Magnetic properties are particularly sensitive to symmetry. Thus, symmetry is particularly important in the area of single molecule magnets (SMMs)62,63,64,65,66,67. SMM performance, in particular blocking temperature, has been proposed to depend on symmetry68,69. But it remains unclear if it is SMM linearity or if it is other symmetry operations that are most important, a question that is likely to vary depending on the central metal70,71. As quasi-symmetry often is the only measure reported72,73, it is hard to determine which symmetry is best. Particularly, in cases where the distinction between coordination geometry and molecular geometry is not clear68,74,75,76. The area of SMMs needs accurate determination of symmetry and it is clearly stated that CShM, e.g., as implementation in the SHAPE software, is not good enough69,77.

The electronic structure of lanthanide(III) compounds is very sensitive to small changes in structure and symmetry. This is apparent in the lanthanide(III) based SMMs62,64,65,66,67,68,69, but has also been shown in fundamental studies of ytterbium(III) Yb78,79,80,81 europium(III) Eu82,83, and neodymium(III) Nd84,85. In all cases, the determined properties are related to the reported molecular structures.

The molecular entity

IUPAC defines constitution and conformations, which in turn defines all molecules and materials through the specific connectivity of distinct sets of atoms placed at specific relative coordinates (x,y,z). When considering structure, we can ignore bonding and all other interatomic interactions, as these becomes a consequence of the set of atoms and atomic positions.

IUPAC further defines a molecular entity, see Fig. 1 which is a molecule or material of a specific constitution that is distinctly different from another molecule or material of the same constitution. That is two molecular entities are the same groups of atoms, but where the electronic structure or the atomic positions give rise to two sets of properties Ø that we can discriminate in a measurement.

a Defining the molecular coordinate system (x,y,z). b Identifying the molecular structure Q. c The structure Q can be determined to be identical to a polyhedron P = T-4 (a tetrahedron). d The structure Q is highly symmetric with symmetry elements like: a C3-rotational axis and three mirror planes. e The symmetry of methane is described by G = Td and Q is reproduced by all 24 symmetry operations in G = Td. Note that the symmetry axis z depends on the symmetry operation, while the molecular Z axis remain constant. Atom legend. carbon = brown, hydrogen = pink, chlorine = green.

The atomic positions (x,y,z) we define as the molecular structure Q(x’,y’,z’), when the atomic positions are aligned to the main symmetry axis (z’). Each molecular entity corresponds to a set of molecular structures QN, sets of atomic positions that all give rise to the same measured property Ø. To define the molecular entities, we need to be able to define, orient and compare the corresponding groups of atomic positions, and we define the molecular structure Q to do this comparison.

Two molecules—methane and chloroform—with different constitutions are by definition different molecular entities. Compounds with identical constitution can be different molecular entities e.g., molecular entity 1, with the molecular structure set Q1, has a property Ø that is different from molecular entity 2, with the molecular structure set Q2 and the property Ø1 ≠ Ø2. We know we have two molecular entities as we have measured two sets of properties. To compare molecular entity 1 and 2 their molecular structures Q1 and Q2 must be known and in the same coordinate system. If we measure three properties, there will be three molecular entities etc.

By definition a set of molecular structures QN describes a single molecular entity as long as it gives rise to the same distinct measurable property Ø. None of the tasks involved in defining a molecular entity is trivial. The molecular structures must be known, and the measurement can be conditional. In an ensemble of molecules, the variation in molecular structures may be so small that only one property is measured e.g., the boiling point of water. While another measurement reveals that several molecular entities are present e.g., the IR spectrum of bulk water26,27. With properties and atomic positions in hand, these must be compared in the correct coordinate system.

Examples of compounds that are different molecular entities include: i) benzene in the ground state S0 ≠ benzene in the first excited singlet state S1 ≠ and benzene in the triplet state T1. ii) water ice-III ≠ water ice-IV. iii) neodymium(III) nonaaqua ion in the tricapped trigonal TTP form ≠ neodymium(III) nonaaqua ion in capped square antiprismatic cSAP form. And iv) a transition metal complex with identical connectivity and Oh ≠ a transition complex with identical connectivity and Td symmetry.

Determining structure

Detailed molecular structure determination is challenging, which we exemplify with methane. Figure 1b shows a methane molecule, a small set of atomic coordinates describing the placement of four protons around a central carbon atom in the coordinate system defined in Fig. 1a. The shape of the molecule is described as a perfect tetrahedron, and by aligning the atomic coordinates in the coordinate system described by the Td point group, we can show that methane indeed has Td symmetry. As shown in Fig. 1b, the molecular structure Q of methane is reproduced by all the symmetry operations of the Td point group. Thus, we can describe methane as a single molecular entity with Td symmetry. Note that methane excited to vibrational states that break this symmetry must be considered as separate molecular entities, as e.g., the symmetry and IR spectrum will be different for vibrationally excited methane.

The atomic coordinates of methane in the correct coordinate system can, using symmetry operations, be shown to have Td symmetry. All other relevant molecular structures of methane will be of higher complexity. Therefore, we must define a single measure of symmetry and start reporting on molecular structures using this measure. Further, to make the measure relevant, we must often assume that we are working on static molecular structures. The alternative is to drown in complexity e.g., if we are to differentiate between the many different thermally excited methane molecules in a sample.

Beyond ideal molecules with symmetry (e.g., methane with Td symmetry), the complexity in determining structure increases. Even with the atomic coordinates of a molecular structure in hand, describing the molecular structure is not trivial, and several approaches are in use. Often, the structure is simply determined ad hoc or relies exclusively on the crystal structures and crystal symmetry. If symmetry is not present, the term pseudo-symmetry is used to assign non-perfect symmetry to molecules and crystals. And even though symmetry is fundamentally a binary concept—it is either present or absent, experiments indicate that approaching a given symmetry is enough for symmetry to be defining the observed properties9,10,12,17,18,86,87,88,89. Thus, moving beyond absolute symmetry and defining a quantity that report on the distortion from symmetry in a continuous matter makes sense. That is, determining symmetry as a continuous property has merit.

The methods available to quantify symmetry include the Continuous Symmetry Measure (CSM)90, which aligns the atomic coordinates and determines distortion from symmetry. While CSM in principle is exact across all symmetries for all structures and mathematically elegant, it has limitations arising from how it is defined and the most recent implementation is limited to cyclic symmetry point groups91. An alternative to a symmetry method is the Continuous Shape Measure (CShM) that measure how close a molecular structure Q is to a set of selected structures P’. The CShM tool has severe limitations, as the current implementations are restricted to the inner coordination sphere and does not take the nature of the coordinating atoms into account. Thus, we prefer to quantify symmetry with the Continuous Symmetry operation Measure (CSoM). The CSoM quantifies the symmetry of any molecular structure, and we propose that CSoM determined symmetry and that the CSoM determined symmetry deviation σsym(Q,G) is the best descriptor of both structure and molecular properties.

To measure symmetry with CSoM, a molecular structure Q is defined as a set of atomic positions. The CSoM software aligns the molecular structure Q in the appropriate molecular coordinate system for all point groups, and reports which symmetry i.e. which point group G, that is the most relevant for this molecular structure. Further, the CSoM approach then provides a numerical deviation from symmetry—a σsym(Q,G)-value, for all selected point groups. The σsym(Q,G)-value defines how well the molecular structure Q is described by each G. Thus, the CSoM places the molecular structure Q on a continuum of σsym(Q,G)-values approaching symmetry which is identified as σsym(Q,G) = 0. By using the CSoM software, we determine and define the symmetry, constitution, and confirmation of each molecular entity in a consistent framework on an absolute scale.

Practical considerations when comparing molecular structures

The structure of compounds can come from many sources and arise from methods with or without restraints. The most important prerequisite, when determining the molecular structure of a molecular entity, is that the crystal structure was not solved—and the computed coordinates were not generated—with any restrictive symmetry. This may lead to artifacts, as these methods per definition generate atomic coordinates of ideal symmetry.

Constitution – how large is the molecular structure?

The same molecular entities cannot have different constitutions. Thus, it is a requirement that molecular structure comparisons take the constitution into account. Nevertheless, it can be relevant to compare molecular structures with different central ions e.g., in the d-block and the f-block. Historically, comparison of metal complexes that differ in donor atoms has been made, and comparisons have been done based on coordination polyhedra alone. These simplifications may be relevant in a descriptive context, but not for describing molecular entities. Here, the question becomes how much of a compound is needed to describe the molecular structure responsible for the observed property. Is the molecular entity defined by the local structure around a metal ion (the first coordination sphere), is the second coordination sphere needed, or should the full complex and solvent be included? Similarly, for solids, is the complex enough, is the symmetry equivalent, should the full unit cell or multiple unit cells be used, and is the solvent in the structure important? The questions are open, as we must determine the size of the molecular structure that gives rise to a specific property, but the method for comparing molecular structures should be able to handle the different types of input.

Note that it is assumed that all properties and structures under consideration are known, isolated and arise from distinct species92,93.

Scaling

Comparing atomic coordinates based on reference structures i.e., using CShM, inherently requires some form of scaling. The same applies if molecular structures with different elements are compared using position or distances alone. While scaling itself is not problematic, it is an additional parameter that must be declared and does create an opportunity for errors to occur. Comparing symmetry, i.e., using CSM and CSoM, does provide a normalized measure but the comparisons themselves do not require scaling.

The yardstick

The true value of molecular structure determination come at scale. Defining a common yardstick that is universal and readily applied will allow a field to start comparing their important properties to e.g., symmetry on a common scale. The key property of the yardstick is that it is agnostic and translatable. Our recommendation is that CSoM should be widely used at the expense of the other approaches. The reason why should become apparent below.

Methods used to determine structure

The continuous symmetry measure: CSM

CSM is a direct measure of symmetry, as defined by a measure for the shortest distance the atomic coordinates have to move to construct a polyhedron with evaluated symmetry. In technical terms: CSM measures the deviation to a point group G defined as the Euclidean distance between the coordinates of the evaluated structure Q and the coordinates of the best aligned G-symmetric polyhedron. The deviation S(Q,G) is defined by the average squared distance between each vertex k of Q and P best aligned to each other with respect to |Qk - Pk|27. The measure is defined in Eq. 1, and the average of Euclidean distances is a normalized root mean square value, where 0 is perfect symmetry.

Q is a sample structure with k vertexes, G is the point group symmetry to which the structure is evaluated to, P is a structure with k vertexes that is restricted to the symmetry \({{\boldsymbol{P}}}{|}_{{{\boldsymbol{G}}}}\) with minimal distance to Q, and N is the number of vertexes k in the polyhedron. The definition is based on early work developed in 1992 by D. Avnir et al90,94.

Illustrations of the CSM calculations are shown for CH4 and CH3Cl in Fig. 2a. CH4 is perfectly Td symmetric and the CSM value therefore yields S(CH4,Td) = 0. The tetrahedron is the only Td symmetric polyhedron with four vertexes. The CSM value for Td symmetry in Coordination Number (CN) = 4 complexes are therefore defined with the tetrahedron T-4. CH3Cl is C3v symmetric and does not contain Td symmetry and the CSM value for Td is therefore required to be nonzero. As the tetrahedron is the only Td symmetric four vertex polyhedron the CSM value is again obtained by evaluating the CHCl with T-4. The obtained value is S(CH3Cl,Td) = 7 as shown in Fig. 2a. The structure is found to be even worse described by D4h symmetry: S(CH3Cl,D4h) = 35. For D4h symmetry the polyhedron used is the square, which is the only D4h symmetric polyhedron with four vertexes. The actual symmetry of CH3Cl is C3v, but this is not readily found with CSM. The triangular pyramid vTBPY-4 is a C3v symmetric polyhedron, however, an infinite span of different vTBPY-4 polyhedra exists—all with C3v point group symmetry. To find the one with the minimal distortion, to satisfy Eq. (1), different search algorithms can be employed.

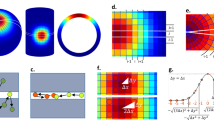

Determining molecular structure Q and symmetry point group G of methane and chloroform either using polyhedral P with the (a). CSM, b CShM or symmetry with c CSoM. CSM provides S-values, CShM provides σideal-values and CSoM provides σsym-values as deviations from ideal fit to P or the symmetry G. Atom legend: carbon = brown, hydrogen = pink, chlorine = green.

The original approach that creates P from Q with respect to a particular symmetry used the so-called ‘folding-unfolding’ algorithm 86,90,95. For four vertexes this works well and the C3v symmetry can readily be assigned for CH3Cl using this method. Using the correct vTBPY-4 polyhedron the structure is indeed found to be C3v-symmetric: S(CH3Cl, C3v) = 0. Beyond four vertexes, the algorithm becomes computationally heavy. These issues can be overcome with intelligent algorithmic design. A recent tool, ChemEnv96 by Waroquiers et al., drastically reduces the amount of permutations by separating groups of atoms within the chemical environment. The most recent implementation of CSM91 by Tuvi-Arad et al. scans only chemically relevant permutations that maintain the connectivity of the molecule allowing the analysis of larger molecules, but is limited to cyclic symmetry point groups. CSM as implemented by Tuvi-Arad is used below.

The continuous shape measure: CShM

An alternative to the CSM is the CShM. CShM is not a measure of symmetry, but simply a geometrical deviation value to a specific reference polyhedron. A search for the perfect polyhedron is therefore not performed. Instead, a manually selected reference polyhedron P is used to compare to the input structure Q. The equation to calculate the geometrical deviation σideal(Q,P) is defined in Eq. 2 and is mathematically identical to CSM. The difference is that no minimizations or searches are performed for P prior to the evaluation, and the deviation value is therefore not to a symmetry group. Instead, it is to a specific polyhedron, which may be symmetric, but is not restricted to be symmetric94,97,98.

The CShM has been implemented in many ways6,86,90,94,95,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111, but the most commonly used algorithm is the one provided by the Shape v2.1 software103. The algorithm is easy to use and the measure has proven to be able to quantify the approximate structure of complexes with coordination numbers from 4 to 10 99,100,106,112,113,114,115,116. Fig. 2b illustrates the calculations for CH3Cl which is evaluated with six different four-vertexes-polyhedra: T-4, vTBPY-4(0), vTBPY-4(1), vTBPY-4(2), SS-4, and SP-4. As was found with CSM, the CH3Cl structure matches perfectly with a specific tetrahedron vTBPY-4. However, an infinite span of vTBPY-4 polyhedra exists with an infinite set of ratios between the distances between the apex vertex to the vertexes in the base. Figure 2b displays four different of such polyhedra, as indeed, the T-4 is also a special case of the infinite span of vTBPY-4. Therefore, finding the ideal reference polyhedron is not trivial and as the reference polyhedra are manually selected, no guarantee to select the correct polyhedron can be given.

The use of CShM and the SHAPE software should therefore be performed with caution. Three different vTBPY-4 polyhedra, excluding T-4, are used as reference polyhedra in Fig. 2b. The best reference is obviously vTBPY-4(1) resulting in σideal(CH3Cl, vTBPY-4(1)) = 0 and CH3Cl can be perfectly described as vTBPY-4, but without a search procedure any value could in principle be obtained. When the best polyhedron is found the special case where CShM and CSM coincide is obtained. In this case the vTBPY-4(1) geometry satisfy Eq. 1 and the CShM is in this specific case identical to CSM evaluated with C3v symmetry for the CH3Cl structure Fig. 2b displays three cases where CSM values coincide with CShM values: T-4 is the CSM with Td symmetry as this is the only 4-vertex polyhedron with Td symmetry, SS-4 with D4h symmetry as this is the only 4-vertex polyhedron with D4h symmetry, and vTBPY-4 with C3v symmetry as this is the best 4-vertex polyhedron to describe the structure with C3v symmetry. A recent development solves this issue. A software called Polynator uses flexible polyhedral models to determine the coordination geometry117. The polyhedra are stretched and bent within the restrictions enforced by the definition of the polyhedron, until a best fit model has been determined. Polynator thus solves the issue of finding the best vTBPY-4 polyhedron in Fig. 2b. However, the implementation employs a different yardstick than CSM, CShM, and CSoM, and the numeric results are not directly comparable to these methods.

The CShM is much more practical to use than CSM, but caution should be exerted when the calculated deviation values are interpreted. Typically, the calculations are arbitrarily selected sets of polyhedra and may not accurately reflect the distortion from symmetry. Another issue with CShM is the inability to evaluate structures to symmetries for which a polyhedron does not exist or for which so many exist that selecting the correct one is impractical. A list of all polyhedron, as provided in Shape v2.1103 from CN = 2 to 12 is provided as Supplementary Information Table S1. Here multiple relevant examples can be considered: For CN = 8 the D4d symmetry contains only a single structure and no good polyhedron with simple C4 symmetry can be constructed and evaluated. The D2d symmetry has two different polyhedra: TDD-8 and JGBF-8. These two are very different in shape and the measure therefore potentially gives very different values. At CN = 9, four C4v polyhedron exists and two D3h, but no C3, C4, and D3 symmetric polyhedra exists. In general, no polyhedron with simple rotational symmetry exists: i.e. the C2, C3, …, Cn symmetries cannot be identified. To measure approximate symmetry, CShM often provides an incomplete description. This issue increases for higher coordination numbers. It is, as the name indicates, a measure of shape and not symmetry. An alternative approach is to characterize the shape of the first coordination sphere with ellipsoids irrespective of coordination number and geometry118. The method is reported to be especially useful for octahedral distortions such as tilt and strain.

CShM: orientation of input structure Q

In order to orient the input structure Q with respect to the reference polyhedron, it is necessary to implement a series of algorithms. To compare Q and P a common molecular coordinate system (x,y,z) must be defined and a normalization must be implemented. The molecular coordinate system is defined from an origin (0,0,0), which can be manually selected, defined by the central atom, or by the center of mass. The size of Q must then be normalized to the polyhedron P. This can be accomplished in two ways. The first method is to normalize the average of the coordinates to have a length of 1 from the origin. The second method is to define all coordinates to be on the unit circle. The correct choice may vary between systems. When Q is aligned and normalized, it must be rotated to reach optimal alignment with P. This alignment is achieved by minimizing the rotation matrix between the two sets of coordinates, e.g. with the Kabsch algorithm119.

To minimize correctly, the labels for each coordinate set in Q must remain valid after each step. Thus, each rotation must occur while tracking the labels. While minimizing the rotation matrix between P and Q is a simple task in itself, tracking labels for each coordinate carries a computational that grows with N!, where N is the number of coordinate sets/labels. For a CN = 10, N! approach 4 million, which makes the approach impractical. Orientation of the input structure of CShM is described in detail elsewhere94.

The symmetry operation measure: SoM

SoM does not measure the difference to a different polyhedron and is fundamentally different to CSM and CShM. SoM is a measure of how well a symmetry operation transforms a structure back into itself120. The mathematical formula is identical to CShM as seen in Eq. 3. The important difference is the reference polyhedron, which is replaced by the symmetry operated structure ÔSQ, where ÔS is a symmetry operation and Q is the structure. The measure is thus a descriptor of how good a specific symmetry operation can be used to describe the structure.

Unlike CShM, SoM accounts directly for symmetry as the measure evaluates how well a structure is reproduced by a symmetry operation. The method has seen various algorithmic developments3,4,5,8,121, and has been used to evaluate the symmetry of simple structural coordinates1,7,108 and has even been generalized to wavefunctions6,44,122.

The issue with SoM is the limitation to only a specific symmetry operation and is therefore not a measure to a complete point group. More importantly, knowledge of the principal axis and orientation of the structure is needed to use SoM. Evaluation with rotational symmetry only really makes sense if the symmetry operation is applied along the best possible symmetry axis.

The continuous symmetry operation measure: CSoM

CSoM is a development on the SoM. It is defined as an average of all SoM for symmetry operations in an entire point group, excluding the identity. The CSoM, σsym(Q,G), is defined in Eq. 4.

σsym(Q,G) is a direct measure of approximate G-symmetry of the structure Q. σsym(Q,G) does not need a reference structure, but an input of a selected point group. Note, that as the individual SoM values for all operations within the selected point group are averaged, the individual contribution of each symmetry operation weighs less in the total σsym(Q,G) value for larger point groups.

Figure 2c shows the CSoM results of Td and C3v symmetry on the CH4 and CH3Cl molecules. To evaluate the structure, they must first be aligned with the principal axis z of the point group symmetries. Both Td and C3v can share a C3 axis, such that the z axis may coincide or be different between point groups.

For CH4, all 24 and 6 symmetry operations of the Td and C3v point groups respectively give a SoM result, a σO-value, of zero. Therefore, the CSoM methods gives a σsym-value of zero for these two point groups that is σsym(CH4,Td) = (23 × 0) / 23 = 0 and σsym(CH4,C3v) = (5 × 0) / 5 = 0. CH4 is therefore found to contain both C3v and Td symmetry.

CH3Cl, however, is not Td-symmetric and the σsym-value for Td is nonzero. Figure 2c shows the structure aligned in the best possible orientation with respect to the operations in Td. Most of the individual SoM values for CH3Cl evaluated with Td, give numerical values of 111, which is a very large numerical value that reflects poorly reproduced structures. However, some of the individual operations (i.e., two C3 and three σd operations) are found to perfectly reproduce the structure with a SoM value of σO = 0. The average deviation, which is the CSoM value gives σsym(CH3Cl,Td) = (18 × 111 + 5 × 0) / 5 = 87.

The structure does not have Td symmetry. Moving to C3v symmetry the best principal axis is through the C3 rotation of the C-Cl bond. It is found that σsym(CH3Cl,C3v) = (5 × 0) / 5 = 0 and CH3Cl is found to have perfect C3v symmetry. CSoM is thus a direct measure to evaluate symmetry as compared to CShM and CSM, which are only indirect symmetry measures. They rely on reference structures with certain symmetries.

CSoM: orientation of input structure Q

The biggest issue with CSoM is finding the best orientation of the coordinates to best match the point group symmetry. To address this issue, a minimizing algorithm to find the best possible principal axis was developed. The minimization algorithm is described in detail in ref. 2.

Other symmetry measures

Numerous methodologies exist that determine distortions from ideal shape and symmetry. The recently developed PorphyStruct is a tool for the analysis of specifically non-planar distortion modes in porphyrinoids123. Using a normal-coordinate structure decomposition technique it is able to characterize the distortions in these D4d symmetric molecules arising from vibrational modes. A similar approach is found for the program Symmetry-Coordinate Structural Decomposition, which is able to measure distortions of a irreducible representation of a point group124. These techniques may allow symmetry measures to go beyond static structures.

Alternative methods are in use that quantify the similarity of multiply constitutionally identical molecules within the same unit cell (i.e. Z’ > 1 crystals). Identifying pseudo-symmetries within the unit cell of Z’ > 1 crystals can be done through different methodologies125,126,127,128. One such example is the computer program CRYSTALS125, which match two sets of coordinates within the same unit cell. The measure is similar to CShM, with the reference structure that is a same-constitution structure within the unit-cell.

Finally, Hyperspace Recognition is used to compare the similarity in structure between molecules of different constitution129. This method goes beyond the measure of simple geometric symmetry, but is not intrinsic to the specific molecular entities.

Results

Recommending the use of CSoM as a general measure of molecular structure and as a tool to identify molecular entities requires that we 1) explore the limits of the other measures of molecular structure that are in use, and 2) attempt to quantify which numerical values of σsym that represent the presence/absence of symmetry. We must remember that symmetry is a binary measure, however, molecular properties can show symmetry even though the geometrical symmetry of the molecular entity is imperfect.

We start by exploring water. The water molecule, data from molecular dynamics simulation of liquid water, and several forms of water ice. We remain in the p-block and demonstrate that CSoM can be used on benzene and larger polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which is not possible using CShM. Then, we move to the d-block looking at coordination polyhedra and molecular structures of transition metals, before concluding in the f-block. Using inorganic nomenclature to describe the number of atoms around the central atoms, we move from coordination numbers (CN) 2, 3 and 4 in water and PAHs over to CN 4-8 in the d-block to CN 5-12 in the f-block thus demonstrating that the CSoM method can be used to describe and define all molecular structures using symmetry. The molecules investigated are shown in Fig. 3.

Water – H2O

Water is a C2v symmetric molecule. The ideal H2O molecule is shown in Fig. 4a. This is the a priori result and the result obtained if the structure is opposed in silico with e.g., the UFF force field. We used UFF implemented in Avogadro using steepest descent to generate the in silico structure. The CSoM value for this optimized water structure is 1E-10, which is the numerical cut-off value of the minimization procedure in the CSoM implementation and is therefore regarded as 0. H2O has three vibrational degrees of freedom. An asymmetric stretch, a symmetric stretch, and a symmetric bend. Only the asymmetric stretch distorts the structure from C2v symmetry.

a Ideal geometry of H2O with C2v symmetry that can only be broken by the asymmetric stretch. b 2000 H2O molecules from a molecular dynamic simulation34 evaluated with the C2, Cσ, and C2v point groups, illustrating the small effect of the asymmetric stretch on symmetry. c The symmetry of water molecules and clusters in ICE III and d the symmetry of water molecules and clusters in ICE IV130,131. e CSoM analysis of a single in silico optimized benzene as well as three crystal structures showing the visual numerical CSoM output. f CSoM analysis of 11 benzene molecular structures172,173,174,192,193,194,195. g CSoM output for the in silico and crystal structure of 1,3,5-trimethyl-benzene. h CSoM analysis for in silico optimized structures and experimental crystal structures of naphthalene, triphenylene, and hexabenzocoronene. The symmetry aligned structures from in silico and the crystal structures are overlaid for visual comparison132,133,180 Atom legend: carbon = brown, hydrogen = pink, oxygen = red.

To explore how much the molecule naturally deviates from C2v, we sampled the structures from a molecular dynamics simulation34. The simulation is of 266,667 water molecules described with force fields (SPC) with a periodic boundary condition and with a density of 1 kg/L and an average temperature of 300 K. Calculating the CSoM value of a subset of 2000 water molecules from this simulation we found an average of σsym(water,C2v) = 1.3E-05, see Fig. 4b. While these are orders of magnitude larger than the optimized geometry they are still incredibly small, and we conclude that water maintains near-perfect C2v symmetry in silico. It is worth noting that if the mirror plane is evaluated with CSoM, σsym(water,σ) = 1E-10 is found. As three points always span a plane, no distortions from ideal structure can remove the Cσ symmetry. Furthermore, the orthogonal plane to the plane that the three points spans will be symmetrically equal to the C2 operation. Thus, the C2v point group of triatomic molecules is always related to the C2 point group with σsym(Q,C2v) = 2/3σsym(Q,C2).

The analysis of water also shows how CSoM can quantify minute deviations from perfect symmetry that arise in “real and perfect” systems, see how the structure of the 2000 water molecules in the MD simulation is readily analysed using CSoM.

Water ice – (H2O)n

While water is a C2v symmetric molecule in the gas phase and in silico, it does not retain a C2v site symmetry in ice. Figure 4c, d shows the analysis of two different forms of ice, ICE-III and ICE-IV130,131.

Considering a single water molecule, ICE-III has the oxygen atom bound to three hydrogen atoms maintaining only partial mirror symmetry σsym(water,σ) = 0.44. Moving beyond the individual molecule, a supramolecular unit with four water molecules has perfect D2 symmetry σsym(Q,D2) <1E-10 = 0.

In ICE-IV the individual water molecule has an oxygen atom bound to four hydrogen atoms in apparent tetrahedral symmetry, however σsym(Q,Td) = 1.2, which is likely too large to assign tetrahedral symmetry to the individual molecule. Instead, the symmetry was found to be σsym(Q,C3v) = 0. Moving beyond the individual molecule, a supramolecular network of 12 C3v symmetric water molecules was found to have D3h symmetry with σsym(Q,D3h) = 0. Note that in the crystal structure, each of the four hydrogen positions has an occupancy of ½.

The analysis of ice shows that CSoM works on both individual molecules and larger clusters. In particular it should be noted that CSoM does not require a central atom to work, which allow us to evaluate supramolecular clusters and larger organic molecules.

Benzene – C6H6

Benzene is a D6h symmetric molecule. We created an ideal benzene molecule using UFF forcefield in Avogadro using steepest descent. The CSoM analysis found σsym(D6h) = 1E-8 which shows that the molecular structure without central atoms can be analyzed, and that UFF produces a D6h symmetric benzene, see Fig. 4e.

Figure 4f shows a CSoM analysis of ten experimentally determined molecular structures of benzene compared to UFF structure. σsym(Q,C2), σsym(Q,C3), σsym(Q,C6), σsym(Q,D6), σsym(Q,D6h), and σsym(Q,S6) are displayed as these are representative for the differences across the ten structures. In particular σsym(Q,C2) highlights that the structures are different, while the C3 axis differentiate the ten structures into types, in the same manner as the more symmetric point groups. Note that CCDC 1100122 is best described by S6, which is why this point group was included.

In general, three types of molecular structures were identified. The low symmetry type contains seven structures. A high symmetry type with two structures. And CCDC 1100122 with S6 symmetry.

The molecular structure taken from CCDC 1100049 is the least symmetric in the low symmetry cluster with high CSoM values across all point groups. With a minimum value of σsym(Q,C2) = 0.17, this benzene is not symmetric. The experimental data for CCDC 1100049 has been questioned, and this example may show distortions larger than what is physical for benzene. Nevertheless, the variation between point groups in CCDC 1100049 is mirrored albeit to a lesser extent in all the ten experimentally determined structures, except for the S6 symmetric CCDC 1100122 structure. Figure 4e includes three selected experimental structures. The least symmetric CDCC 1100049, one that is slightly less symmetric CCDC 251255, and the most symmetric of the low symmetry cluster: CCDC1100158. While the distortions are clearly visible in the former two, the latter with σsym < 1E-2 only show minimal differences in the positions of the atoms after the structure has been operated on by the relevant symmetry operators.

Methylbenzenes – (CH3)n-C6H6 -n

Having analysed benzene, we increase the complexity slightly with toluene, xylene, and 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene. These molecules contain one, two, and three methyl groups which reduce the symmetry. In particular if the positions of the hydrogen atoms on the methyl groups are considered. Note that the experimental precision in determining the positions of hydrogen atoms vary. Consequently, the accuracy of the structural symmetry becomes limited. However, the following demonstrate that CSoM readily analyse proton positions.

We created idealized molecular structures using UFF forcefield in Avogadro using steepest descent and compared these to experimental crystal structures of the compounds. Table 1 lists the results of the CSoM and CSM analysis. Starting with toluene, the addition of a methyl group breaks the D6h symmetry of benzene. The optimized carbon structure of toluene has σsym(Q,C2v) = 2E-2 which indicates perfect C2v symmetry, but the inclusion of protons reduces the symmetry to Cσ with σsym(Q,Cσ) = 1E-6 and the CSoM value for C2v has significantly increased to σsym(Q,C2v) = 1.82. With the addition of the second methylene group, going from toluene to xylene, we have three different cases for ortho-, meta- and para-xylene. Considering first the carbon-only structure and then the full structure with protons, we see the effects of the hydrogen positions. Considering the CSoM analysis for ortho-xylene we determine σsym(o-xyleneC,C2v) = 0.03 for the carbon structure, while we find σsym(o-xylene,C2v) = 0.33 when including hydrogen atoms. Due to the hydrogen atom the molecular symmetry reduces to σsym(o-xylene,Cσ) = 0.04. Similar we find that meta- and para-xylene has σsym(m-xyleneC,C2v) = 0.08 and σsym(p-xyleneC,D2h) = 0.14 for the carbon structures, which reduces to Cσ symmetry when the hydrogen atoms are included: σsym(m-xylene,C2v) = 0.16 and σsym(m-xylene,Cσ) = 0.06, while σsym(p-xylene,D2h) = 1.35 and σsym(p-xylene,Cσ) = 0.09. Similar results may be obtained with CSM, however, the current implementation of CSM only handles cyclic point groups and while these are correctly identified by the program91, the reduction in symmetry (from e.g., Dnh to Cn) that occurs when the protons are included are not shown.

Finally, 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene was investigated and the analysis is shown in Fig. 4g highlighting the effect of the proton positions on the symmetry. The in silico carbon structure has D3h symmetry and the molecular structure has C3h symmetry: σsym(QUFF,C3h) = 5E-8. In contrast we find that the experimental structure has a significantly distorted symmetry as the carbon structure gives σsym(QC,D3h) = 0.28 and the experimental molecular structure gives σsym(Q,C3h) = 0.55. Figure 4g shows the distortions that happen in the crystal structure to remove symmetry, which demonstrates the power inherent to the CSoM analysis when visualizing the outcome of the symmetry operations. As the current implementation of CSM can only handle cyclic symmetry point groups the symmetry reduction from D3h to C3h cannot be resolved using CSM91.

Polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)

Polyaromatic hydrocarbons are typically planar and highly symmetric molecules. We created idealized molecular structures using UFF in Avogadro using steepest descent and compared these to experimental crystal structures of the compounds. The CSoM analysis of six different polycyclic aromatics is provided in Table 1 and visualized in Fig. 4h for both optimized and crystal structures. In contrast to the methylbenzenes, the polyaromatic hydrocarbons only contain sp27-hybridized carbon atoms. Thus, these are more similar to benzene than toluene. That is up to a point, as the largest PAHs, like hexabenzocoronene, are no longer planar132. Table 1 shows the CSoM analysis of naphthalene, triphenylene, and hexabenzocoronene, illustrating this deviation from planarity.

The smaller PAHs all have Dnh symmetry, as they are perfectly planar, the CSoM results are compiled in Table 1. The determined σsym(Q,Dnh) are low for the smaller PAHs. However, for triphenylene that has sterically congested hydrogens132, a small twist can be observed in the experimentally determined structure133. As this twist is not found with the UFF method, the twist is readily observed in the overlay in Fig. 4h. The twist also manifests in a deviation from D3h with σsym(triphenyleneC,D3h) = 0.15, while C3v without a mirror plane in the plane of the molecule has σsym(triphenyleneC,C3v) = 0.09 and σsym(triphenyleneC,C2) = 0.06. These values are for the carbon structure alone, if the molecular structure is considered we find σsym(triphenylene,D3h) = 0.20 and σsym(triphenylene,C3v) = 0.13 and conclude that triphenylene only has C2 symmetry with σsym(triphenylene,C2) = 0.07. The same type of distortion leads hexabenzocoronene to have D3d symmetry instead of D6h symmetry.

Transition metals, coordination polyhedra

With the demonstration of how the CSoM method can analyze organic molecules, we move to metal complexes. We start in the d-block with transition metal complexes, and we only use experimentally determined molecular structures. Here the SHAPE program has been used extensively to determine the structure of coordination polyhedra103,112,113106, which we also refer to as the first or inner coordination sphere in a complex. Thus, we start with the CSoM analysis by investigating just the coordination polyhedron. Note that SHAPE does not differentiate between donor atoms in the coordination polyhedron. SHAPE only compares the shape or geometry formed by the coordinating donor atoms to selected reference polyhedra, thus we also used Polynator that finds the correct reference polyhedra, see Table S3. Either implementation of CShM has similar limitations, thus we limit our discussion to SHAPE.

The CSoM analysis accounts for both the position and the nature of the coordinating atoms. In this section we start by comparing the differences in the CShM and CSoM analyses, in the following section we show that it can be important to consider more than just the coordination atoms when determining the symmetry of a metal complex. As the symmetry depends on the coordination numbers, we differentiate based on these. The full analysis is compiled in Table 2, and the structures can be seen in Fig. 3 and the Supporting Information pages S4-S50.

Starting with CN = 4, SHAPE finds that FeCl4 is a good match to the tetrahedron (P = T-4) with a CShM value of σideal(Qinner,T-4) = 0.23. The CSoM analysis show that the symmetry is not Td as σsym(Qinner,Td) = 0.97. Rather, iron(II) chloride is found to be C2v symmetric with σsym(Qinner, C2v) = 0.03. Where SHAPE reports that iron(II) chloride has tetrahedral geometry—inferring Td symmetry, the CSoM analysis reports that iron(II) chloride has C2v symmetry. Which symmetry that determines the molecular properties is difficult to conclude without experimental testing, but if only SHAPE was used the symmetry may have been overestimated for iron(II) chloride.

The square planar nickel complex [Ni(L)]+134 also has CN = 4, but has three different types of coordinating nitrogen atoms that almost form the plane. This is confirmed by SHAPE as the best polyhedron is found to be the square (P = SP-4) with σideal(Qinner,SP-4) = 0.72, which indicates D4h symmetry. The value found with SHAPE is small, but larger than the 0.32 found for iron(II) chloride. The symmetry of Ni(L)]+ is not that of SP-4, as σsym(Qinner,D4h) = 1.4. C2v symmetry is a better match with σsym(Qinner,C2v) = 0.56, which is still large, and the structure may be considered asymmetric.

Figure 5a-c and Fig. 5f shows the CShM and CSoM analyses of the coordinating atoms of four complexes: FeIICl4 (CN = 4)135, [Ni(L)]+ (CN = 4)134, FeIIICl6 (CN = 6)136, and Fe(btz)33+(CN = 6)137. The two iron(III) complexes with CN = 6 are with SHAPE found to be closest to the octahedron (P = OC-6). SHAPE finds σideal(Qinner, OC-6) = 0.13 for FeIIICl6 which is significantly lower than the σideal(Qinner, OC-6) = 1.4 determined for Fe(btz)33+. The former complex may be considered more octahedral, and CSoM shows that this is reflected in the symmetry. FeIIICl6 with σsym(Qinner,Oh) = 0.08 can be described with Oh symmetry, while Fe(btz)33+ with σsym(Qinner,Oh) = 2.5 cannot. However, the best CSoM result provides additional information. While Oh can describe FeIIICl6, the best CSoM result is for D4h symmetry with σsym(Qinner,D4h) = 0.01. Whether this detail is important requires experimental investigations. Fe(btz)33+, which did not have Oh symmetry despite having an octahedral shape, can instead be shown to have D3 symmetry with σsym(Qinner,D3d) = 0.01. Note that no idealized polyhedron with 6 vertexes can be constructed with D3d symmetry, thus the correct geometry for the molecular structure for Fe(btz)33+ cannot be determined with SHAPE and Polynator.

Comparing coordination polyhedra P determined with CShM using σideal-values to the symmetry expressed with point groups G determined with CSoM via σsym-values for: a FeIICl4135, b [Ni(L)]+134, c FeIIICl6136, d CdCl215-crown-5139, e CuMn-MFU-4140, f Fe(btz)33+(CN = 6)137. g The four phases observed for the BaTiO3 perovskite analyzed with CSoM for the of BaO12 h and TiO4 i centers in the BaTiO3 perovskite as a function temperature. Structural data from reference142 and 141. Atom legend: carbon = brown, hydrogen = pink, oxygen = red, nitrogen = light blue, chlorine = green, titanium = ice blue, manganese = blue, iron = gold, copper = purple, nickel = light gray, cadmium = light purple, barium = bright green.

Detailed inspection of the CSoM output structures reveal that while the FeIIICl6 does have slightly shorter distances to the axial donor atoms with Fe-Clax = 2.41 Å and Fe-Cleq = 2.55 Å the complex can likely be regarded as Oh symmetric. The perturbation to the structure is reflected in the better match to D4h symmetry.

A total of 25 structures were analyzed with both SHAPE, CSM, and the CSoM method. In many cases we found that the molecular structure had a different symmetry than the coordination polyhedron. Thus, we cannot investigate the relevant structures from the SHAPE results, which only consider the latter. With SHAPE, one general trend is worth noting: We observed that all structures with CN = 6 were found to be octahedral in the SHAPE analysis. This was not reflected in symmetry when the CSoM method was used, see the entries in bold in Table 2. While SHAPE did not differentiate these structures both Polynator and CSM did, see Tables S2 and S3, however, only CSoM determines the correct symmetry.

Transition metal complexes

The electronic structure of a molecule or complex is determined by the position of the coordinating atoms alone. The orbitals on the coordinating atoms must be described138. This is readily achieved by analysing the symmetry of the molecular structure, rather than focusing exclusively on the coordinating polyhedron.

If we return to the possibly asymmetric [Ni(L)]+ complex, where we analyzed the coordination polyhedra in Fig. 5a-c, the structure—shown in Fig. 3— with σsym(Qinner,C2v) = 0.56 could potentially have a C2 axis or a mirror plane. When the molecular structure was investigated, we find σsym(Q,C2v) = 6.6 and σsym(Q,Cσ) = 5.1, which show that the complex has no symmetry.

Figure 5d-f shows three complexes, for which we analysed the coordination polyhedral and the molecular structure. One CN = 7 cadmium(II) complex where 15-crown-5 provides 5 oxygen atoms as equatorial ligands and two chloride ions complete the coordination sphere on the axial positions139. The coordination polyhedron is best represented by the pentagonal bipyramid, and the symmetry is also found to best be described by D5h. However, the σsym-values are large, and CdCl215-crown-5 must be considered to only have approximate symmetry at best. In contrast, CuMn-MFU-4, a metal organic framework with manganese as CN = 6 vertices, and where the manganese ions only have nitrogen atoms in the coordination polyhedron, is found to have perfect Oh symmetry140. The coordination polyhedron has σsym(Qinner,Oh) = σsym(Qinner,Td) = 0.0, however the molecular structure has σsym(Qinner,Oh) = 29 and σsym(Qinner,Td) = 0.0. Thus, analysis of the coordination polyhedron provides a wrong description of the symmetry at the manganese atom, as molecular structure defines the molecule as Td symmetric. Note that SHAPE correctly defines the coordination polyhedron as an octahedron. Similarly, the [Fe(btz)3]3+ complex with CN = 6 is found to be an octahedron with SHAPE137. The CSoM method shows that the symmetry of the coordination polyhedron is in fact D3d with σsym(Qinner,D3d) = 0.01. However, if the molecular structure is analysed this is clearly wrong as we find σsym(Q,D3d) = 0.83. The symmetry of [Fe(btz)3]3+ is actually S6 with σsym(Q,S6) = 0.01.

All the numbers, symmetry axis, and symmetry operated structures are automatically generated for all point groups when the CSoM method is used. Thus, we can readily determine the difference between the coordination polyhedron and the molecular structure of [Fe(btz)3]3+, see Fig. 5f. The difference between D3d and S6 is six mirror planes, which are not present in the molecule. Note that C2h also describes the [Fe(btz)3]3+ well as a mirror plane exist orthogonal to the C2-axis.

We explored a selection of transition metal complexes. The results are shown in Table 2. While the selected set of structures are not exhaustive, it is worth noting that none of the CSoM determined symmetries of the transition metal complexes are those determined by SHAPE for the coordination polyhedra.

Phase transitions in BaTiO3

The well-studied perovskite BaTiO3 is known to have four different ferroelectric phases as a function of temperature. When changing the temperature of the perovskite from 10 to 450 K, three phase transitions have been observed between phases identified by the space groups R3m at low temperatures (<180 K), then Amm2 and P4mm, before forming \({{\rm{Pm}}}\bar{3}{{\rm{m}}}\) symmetric lattice at high temperature ( > 400 K)141,142. The phase transitions have been reported through different structural parameters. These include the lattice constants, the Ti-O distances, the O-O distances, the equivalent isotropic parameters, the unit cell volumes, the electric polarization, the extinctions coefficient, and the strain broadening coefficients142. Recently, the structure of the coordination polyhedra was analyzed with an ellipsoidal analysis providing strong complementary value118. When considering the data we note that the Ti-O distances are not effected by temperature within each phase, but change abruptly between phases. Thus, we decided to determine the symmetry of the BaO12 and TiO4 centers in each phase, see Fig. 5g.

The CSoM analysis shows that symmetry of both metals can be evaluated through the temperature series, see Fig. 5h-i. In the R3m phase, the point group of both BaO12 and TiO4 is a perfect C3v symmetry, which turns into a perfect C2v in the Amm2 phase. At higher temperatures the symmetry is perfect D4h for BaO12 and perfect C4v for TiO4 in the P4mm space group, and both adopt perfect Oh symmetry in the \({{\rm{Pm}}}\bar{3}{{\rm{m}}}\) phase. In addition to determining the symmetry, the analysis show that the σsym-values change continuously as a function of temperature. This indicates that the overall symmetry in the perovskite increases with temperature. An insight which was not obvious before using CSoM118,141,142.

Lanthanide complexes

We started exploring molecular structures in the f-block, with the perception that our understanding for coordination numbers 4 to 6/7 was well established. A statement that holds for coordination polyhedra, but not for molecular structures, see above. Lanthanide complexes are typically of coordination numbers from 7 to 10, and finding the correct reference polyhedra is difficult. As we will show below using SHAPE in the f-block gives questionable results at best111,143,144. In contrast, we show that CSoM is both fully automated and robust.

Figure 6a-d shows the analysis of four lanthanide complexes with CN = 7, 8, 9, and 12. The Dy(bbpen)X complex with CN = 7 is best described by PBPY-7 using SHAPE with σideal(Qinner,PBPY-7) = 2.05, see Fig. 6a145. However, with σsym(Qinner,D5h) = 69 the symmetry of the coordination polyhedron is not D5h symmetric as PBPY-7 would suggest, but C2, which is also the symmetry of the molecule: σsym(Q,C2) = 0.0. The Nd(pc)2 complex has CN = 8 and has a coordination polyhedron that is an almost perfect match to the cube polyhedron σideal(Qinner,CU-8) = 0.38, see Fig. 6b146. The σsym-values reveal a significant distortion from Oh symmetry with σsym(Qinner,Oh) = 0.7. Instead, the coordination polyhedron of Nd(pc)2 is found to have D4 symmetry with σsym(Qinner,D4) = 0.0. This symmetry is enforced by the molecular structure that has σsym(Q,Oh) = 8.0 and σsym(Q,D4) = 0.04. Nd(oda)3147, with CN = 9, is matched to the TTP polyhedron by SHAPE σideal(Qinner,TCTPR-9) = 1.7, see Fig. 6c. However, the symmetry is not D3h with σsym(Qinner,D3h) = 8.8, but closer to D3 with σsym(Qinner,D3) = 0.3. The σsym-value is high and scrutiny of the CSoM analysis shows that the structure is found to be better described by C2 symmetry than C3 symmetry. Both are subgroups to D3. With a minimum σsym-value value of 1.3, the molecular structure of the complex is considered to be significantly distorted from D3 symmetry. The last complex is Dy(tp-py)2148, a complex with CN = 12, see Fig. 6d. The coordinating atoms form an icosahedron with σideal(Qinner,IC-12) = 0.5, with an acceptable match to a distorted Ih symmetry σsym(Qinner,Ih) = 0.96. This value is a little large, thus the coordination polyhedral should be described as having D3d symmetry with σsym(Qinner,D3d) = 0.001 instead. The molecular structure is equally well described by S6 and D3d symmetry with σsym(Q,D3d) = 0.10 and σsym(Q,D3d) = 0.09. As S6 does not have any mirror planes perpendicular to the principal axis the transition probabilities in e.g., optical spectroscopy will be very different depending on whether the molecular structure is best described as S6 or D3d.

a Dy(bbpen)X145, b Nd(pc)2146, c Nd(oda)3147, d Dy(tp-py)2148. e CSoM investigation of the structure of Ln(sst)3THF2 series. f CSoM investigation of the structure of Tm.DOTA and Dy.DOTA(H2O) and the electronic structure of Dy.DOTA(H2O) as a function of symmetry163. Atom legend: carbon ligand backbone = pale gray, silicon ligand backbone = blue, hydrogen = pink, oxygen = red, aromatic nitrogen = light blue, aliphatic nitrogen = dark blue, lanthanum = green, neodymium = deep purple, dysprosium = bright green, thulium= aquamarine, lutetium = pale green. Images in panel f used with permission of Royal Society of Chemistry, from Chemical Science, M. Briganti et al, 10, 7233-7245, 2019; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

The analysis of the lanthanide complexes, emphasize the conclusion above: While the SHAPE can be a measure to identify a coordination polyhedron, these very often provide a poor description of the symmetry and molecular structure of the complex. In Table 2 SHAPE identify the correct structure in 1/25 cases, and in 11/25 cases the coordination polyhedron and molecular structure is of the same symmetry.

Thus far, we have only touched on how the CSoM analysis can be used to visually compare symmetries and structures, and how the analysis can be used to determine symmetry and distortions from symmetry. The CSoM method is particularly strong when used along experimental data as in the examples below.

A series of tris(trimethylsilyl)siloxidelanthanide(III) complexes

The series of lanthanide ions has been explored by preparing isostructural complexes, looking for structural changes induced by the lanthanide contraction147,149,150,151. Along this vein, a series of CN = 5 Ln(sst)3THF2 complexes was reported by Boyle and coworkers152. In the report the structure of the complexes were described as having tricapped bipyramid (TBPY-5) coordination polyhedra, which indicates D3h symmetry. For the lighter, larger lanthanide(III) ions the description with TBPY-5 is worse than it is for the heavier, smaller lanthanide(III) ions. We revisited the data using the CSoM method. The results are shown in Fig. 6f, and the data for the Eu(III) complex is shown in Table 2.

As 0.3 < σideal(Qinner,TBPY-5) < 0.6 SHAPE reports that the complexes can be described with the TBPY-5. Similarly, the CSoM method reports that with σsym(Qinner,C3) ≈ 0.2, all the complexes have coordination polyhedra that are only slightly distorted from C3 symmetry.

Considering the molecular structure Fig. 6f shows how the σsym(Q,C3)-value clearly show how the difference in size from La(III) to Lu(III) impacts the distortion of symmetry of the complexes. This example illustrates how CSoM can improve the analysis of isostructural complexes based on the molecular structure153,154.

Ln.DOTA

Lanthanide(III) complexes of the DOTA ligand (DOTA = 1,4,7,11-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,11-tetraacetic acid) are by far the most studied lanthanide(III) complexes155,156,157,158,159,160,161. Ln.DOTA crystallize with and without a capping water molecule resulting in complexes with CN = 8 and CN = 9. Figure 6g shows a CN = 8 Tm.DOTA and a CN = 9 Dy.DOTA(H2O) complex i.e., DOTA complexes of two trivalent lanthanides that crystallized with and without a capping water molecule162. As the coordination number is different, the CShM method provides different results describing the Tm.DOTA complex as the square antiprismatic polyhedron SAPR-8; σideal(Qinner,SAPT-8) = 2.46, and the Dy.DOTA(H2O) complex as the capped square antiprismatic polyhedron CSAPR-9; σideal(Qinner,CSAPR-9) = 0.47. Thus, the two coordination polyhedra cannot be compared using SHAPE. However, the CSoM method shows that both complexes have C4 symmetry, both with σsym(Qinner,C4) = 0.02.

In this particular example, the electronic properties of Dy.DOTA(H2O) were studied as a function of the molecular structure, thus only the CSoM method is relevant. Considering the molecular structure, Tm.DOTA almost retains C4 symmetry with σsym(Q,C4) = 0.15. The molecular structure of the Dy.DOTA(H2O) complex has C4 symmetry if the protons on the capping water molecule are ignored: σsym(Q,C4) = 0.08. If the protons on the capping water molecule are included, the symmetry is broken: σsym(Q’,C4) = 0.85. The importance of the orientation of the water molecule was recognized by Le Guennic and coworkers163,164, who explored the effect on the electronic structure in silico. They found that the electronic ground state and the first excited state cross twice within a 180° rotation of the capping water molecule163. Which translated into significant changes in the magnetic properties of the complex. Determining the symmetry of the Dy.DOTA(H2O) complex with CSoM as the capping water is rotated, we see a periodic variation in the σsym(Q,C4v), σsym(Q,C4), σsym(Q,C2v), and σsym(Q,C2) values, see Fig. 6g. Interestingly, each of the four σsym-values are found to behave differently: σsym(Q,C4) is found to be invariant to the rotation, and σsym(Q,C2) varies with the full rotation of the water molecule with a period of 360°. The σsym(Q,C2v)-value has a period of 90°, while for the σsym(Q,C4v)-value it is 45°. The electronic properties determined by Le Guennic and coworkers showed a period of 90°, suggesting that the electronic properties of the Dy.DOTA(H2O) complex are governed by C2v symmetry163,164.

Europium luminescence

The lines observed in the emission spectrum of Eu(III) are routinely correlated to the perceived symmetry of a complex based on symmetry arguments82,165,166. The emissive term 5D0 contains a single electronic state, while the final terms 7F0, 7F1, and 7F2 contain 1, 3, 5 electronic states. The arguments for the three bands 5D0 → 7FJ (J = 0, 1, and 2) can be stated briefly as:

-

Without symmetry, 1, 3, and 5 lines (the maximum) will be observed in the three bands.

-

In cubic symmetry groups (e.g., Oh and Td) 1 and 2 lines will be observed in 5D0 → 7F1 and 5D0 → 7F2 bands, respectively.

-

In hexagonal or trigonal symmetry (e.g., D3h and C3) 2 and 3 lines will be observed in 5D0 → 7F1 and 5D0 → 7F2 bands, respectively.

-

In tetragonal symmetry (e.g., C4 and D4d) 2 and 4 lines will be observed in 5D0 → 7F1 and 5D0 → 7F2 bands, respectively.

-

If the point group symmetry has a mirror plane or a C2 axis perpendicular to the main symmetry axis the 5D0 → 7F0 line will disappear. In cyclic groups (e.g., Cn) a single line will be observed.

Figure 7 displays the emission spectra of the bands 5D0 → 7FJ (J = 0, 1, and 2) for ten Eu(III) complexes that we selected to analyze using CShM and CSoM. A summary of the analysis is compiled in Table S4.

The structures and spectra are redrawn from literature data: a. Eu:Ba2MgWO6196, b. Eu2(SO4)6111, c. EuOCl197, d.Eu(pic)3·3(aza)198, e. Eu.DOTA(H2O)199, f. Eu.L’(H2O)199, g. Eu(oda)3200, h. Eu(dpa)3201, i. EuTp3202, and j. Eu.edta(H2O)3201. Atom legend: europium = purple, carbon = brown, oxygen = red, nitrogen = light blue, chlorine = green, sulfur = yellow, barium = orange, tungsten = dark orange. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

In Fig. 7a a crystalline phosphor is shown, in this material Eu(III) has cubic symmetric with σsym(Eu:Ba2MgWO6,Td) = 0.0 aligning with the observation that a single line is observed for 5D0 → 7F1 while no line is observed for 5D0 → 7F0. In Fig. 7b the symmetry of Eu(III) in solid LnOCl is C4v and as expected a very intense 5D0 → 7F0 line and two lines within 5D0 → 7F1 were observed.

When moving to molecular materials in Figs. 7c and 7d the results show that the symmetry of the molecular structure is important. While first coordination sphere is described by C4 symmetry with σsym(Eu.DOTA(H2O),C4) = 0.1 and σsym(Eu.L’(H2O),C4) = 0.3, thevalues for the molecular structures σsym(Eu.L’(H2O),C4) = 43.7 and σsym(Eu.DOTA(H2O),C4) = 0.5 show that only Eu.DOTA(H2O) has C4 symmetry. The spectra confirm this finding as the splitting of the 5D0 → 7F1 band increase from 2 lines in Eu.DOTA(H2O) split into 3 three lines in Eu.L’(H2O), which corresponds to the reduction in symmetry from C4 to C2. Figure 7d shows that the maximum number of lines can be observed in Eu2(SO4)6 that has perfect C2 symmetry.

Considering trigonal groups, Eu(dpa)3 has a molecular structure with perfect D3 symmetry and the corresponding spectra in Fig. 7f show no 5D0 → 7F0 line and two lines in 5D0 → 7F1. Figure 7g shows the spectra Eu(oda)3 with near perfect D3 symmetry of the coordination atoms and a distorted molecular structure. While the spectra of Eu(dpa)3 and Eu(oda)3 are close to identical, the Eu(oda)3 corresponding spectra appear to be split slightly more due to the lack of symmetry in the molecular structure. It should be noted that the CShM value for both TTP and cSAP are identical and small for both Eu(oda)3 and Eu(dpa)3 and CSM cannot identity the D3 symmetry.

Figure 7h shows the Eu(tp)3, with an inner coordination sphere with D3h symmetry, and a molecular structure with C3 symmetry. This is expressed in the spectra as the 5D0 → 7F0 line appear. The importance of considering the molecular structure is enforced when considering Eu(pic)3·3(aza) in Fig. 7i where the CSoM values for the coordinating atoms are σsym(Qinner,D3h)= 0.7, but the maximum amount of lines that are observed in the spectra shows that the europium center does not have symmetry, supported by the lack of symmetry in the molecular structure. The last example is the completely asymmetric Eu.edta(H2O)3 complex shown in Fig. 7j, where the 5D0 → 7F0 line is clearly observed next to three well-separated lines in the 5D0 → 7F1 band.

Nd(III) electronic structure

The crystal field splitting of Nd(III) are not as readily explained as the crystal field splitting of Eu(III)84. However, the electronic structure of the central ion must still be influenced by the symmetry of the environment. Figure 8a shows the crystal field splitting of the 4I9/2 term of Nd(III) in ten different materials, and trends emerge when the crystal field splitting diagrams are sorted by symmetry. All D3h symmetric Nd(III) ions share a crystal field splitting where the levels are grouped in a (1, 2, 2) distribution. Reducing the symmetry to D3, C3v, or C3 the crystal field splitting is different, which is evident in the Nd(III) emission spectrum. Considering Fig. 8a, we note that the two molecular structures with D3 symmetry, Nd(oda)385 and Nd(dpa)3167, share the same distribution of (2, 1, 1, 1). In the S4 symmetric Nd:LiLuF4168, and the D2 symmetric Nd:YAG169 materials we find a similar distribution of levels. The CSoM analysis determined that the Nd:LiLuF4168 structure has slightly distorted D2 symmetric with σsym(Qinner,D2) = 0.2 and that the Nd:YAlG has distorted S4 symemtry with σsym(Qinner,S4) = 2.0, and must consider that these distortions might be of a magnitude where the effective symmetry of both structures are the same. In Fig. 8b-g the emission spectra showing the Nd(III) 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 band are shown for six materials. This data is condensed in the crystal field splitting diagram, but cursory inspection of the band shapes highlights that minute differences and similarities in symmetry are readily translated to spectral features in lanthanide(III) luminescence.

a Crystal field splitting in the lowest energy term 4I9/2 of Nd(III) in 10 different environments: Nd:LaCl3203, Nd(H2O)9(EtSO4)3204, Nd(H2O)9(BrO3)3205, Nd2(N3)8206, Nd(oda)385, Nd(dpa)3 (Note: CSoM values have been taken from the Eu(dpa)3 structure as the crystal field splitting has only been determined in solution)167, Nd:La2O3207, Nd(btmsm)3208, Nd:LiLuF4168, and Nd:YAG169. The energy levels were determined with emission spectroscopy for each molecular structure Q and the point group G was determined with a CSoM analysis. The relevant σsym(Q,G)-values are shown on the plot. The emission spectra of the 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 band for selected molecular structures Q with their CSoM determined point group G, are shown for b Nd2(N3)8, c Nd(oda)3, d Nd:YAG, e Nd(H2O)9, f Nd(dpa)3, and g Nd:LiLuF4 complexes, the spectra are redrawn from earlier work85,137,167,168,169,206. Atom legend: neodymium = deep purple, carbon = brown, oxygen = red, nitrogen = light blue. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

Discussion

Any quantitative method needs a yardstick and when it comes to symmetry a cut-off must indicate the presence and absence of symmetry. A real cut-off must be based on experimentally determined structures and symmetry dictated properties e.g., splitting of signals in NMR, EPR etc. The analysis here suggests the following cut-off values based on input data. The symmetry analysis of water suggests a numerical cut-off of σsym = 1E-4 for symmetry when using CSoM on in silico data of small molecules. For larger molecular structures a cut-off would appear to be σsym < 0.1.

Considering the CSoM analysis for ortho-xylene we determine σsym(o-xyleneC,C2v) = 0.03 for the carbon structure, while we find σsym(o-xylene,C2v) = 0.33 and σsym(o-xylene,Cσ) = 0.04 for the molecular structure. Using the cutoff of σsym < 0.1 the symmetry of ortho-xylene is assigned as Cσ for the molecule and C2v for the carbon structure. Similarly for meta- and para-xylene: with σsym(m-xylene,C2v) = 0.16 and σsym(m-xylene,Cσ) = 0.06 the symmetry of meta-xylene was determined to be Cσ, and with while σsym(p-xylene,D2h) = 1.35 and σsym(p-xylene,Cσ) = 0.09 the symmetry of para-xylene was determined to be Cσ. These numbers are not the solution, but the beginning of a yardstick.

In summary, we find that there is nothing more important in chemistry than molecular structure. However, we do not have a measure that allows us to talk about molecular structure at the level of detail that experimental and theoretical methods now provide. Here, we have shown the limits of current methods for determining and discussing molecular structure and symmetry, and we have highlighted the power of the Continuous Symmetry operation Measure (CSoM) methodology through a series of case studies spanning the symmetry in the molecular structure of water, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, classical transition metal complexes, single molecule magnets, and lanthanide complexes. We conclude that the CSoM method works across all inputs, automatically ensures that the correct molecular coordinate system is used, and provides both numerical and visual outputs.

To demonstrate applicability of CSoM and demonstrate the relevance of symmetry as a relative measure we used lanthanide(III) luminescence. The symmetry determined with the CSoM method was used to rationalize the crystal field splitting and band shapes of Nd(III) and Eu(III) emission spectra, and we noted that the CSoM results reflect both the physical distortion from symmetry and the resulting molecular properties.

Using CSoM values requires a yardstick and based on the results presented here we conclude that for in silico molecules symmetry is present if σsym ≤ 1E–4. While experimentally determined molecular structures often carry a larger error and are symmetric if σsym < 0.1. In general, 1 ≤ σsym < 5 reflects structures that are distorted or heavily distorted from a symmetry. As the size of the molecular structure is relevant, in particular for properties arising from single atoms e.g., transition metal or lanthanide centers, the σsym-values for larger structures may have less strict symmetry cut-off values. These values are to be considered as a starting point only, as they are derived from a small set of structures without considering a specific experimentally observable property. In order to provide physical meaningful CSoM cut-off values for symmetry, a specific symmetry dependent property must be declared, and the proposed values should be tested on a significant sample set. Here, we verified the selection rules in europium(III) luminescence and begun to analyse the electronic structure of neodymium(III).

In conclusion, we propose a path to making comparative studies across chemistry and material science easier. First, we propose that chemists use the IUPAC definition of molecular entities when correlating molecular structure to molecular properties. Second, we propose the CSoM methodology as a unifying method to quantify and analyze molecular structure. And third, we propose that we start using σsym-values in combination with experimental results to set a σsym cut-off for when symmetry dictates an observed property.

Methods

Structure retrieval

All structures have been manually retrieved as ‘.cif’ files from the ccdc database. The ‘.cif’ files have been used to construct the ‘.xyz’ files manually in the software VESTA v3. The distinction between molecular structure and first coordination sphere has been done manually.

In silico structures

In silico structures have been geometry optimized from the relevant crystal structures retrieved, see above, in Avogadro170 using UFF force fields171. For the geometry optimizations 500 steps have been used with the steepest descent and a convergence threshold of 10E-10.

CSM

The Continuous Symmetry Measure (CSM) program has been used on the webpage csm.ouproj.org.il. The implementation is reported in ref. 91.

CShM

The Continuous Shape Measure (CShM) has been used with the SHAPE v2.1 program. The implementation is reported in ref. 103.

CSoM

The Continuous Symmetry operation Measure (CSoM) has been used on the structure files in the ‘.xyz’ data format. The program was downloaded from (https://github.com/VRMNielsen/Continous-Symmetry-Operation-Measure-Program). The implementation is reported in ref. 2.

Polynator

The Polynator program has been used as a different shape measure. The program has been downloaded from (https://journals.iucr.org/j/issues/2023/06/00/jl5072/index.html). The implementation is reported in ref. 117.

Data availability

The structures used and data generated in this study have been deposited in the FigShare database (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29382491.v1). Visualizations of the data are included in the supporting information page S6-S50. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

The CSoM code used in this article have been uploaded to GitHub (https://github.com/VRMNielsen/Continous-Symmetry-Operation-Measure-Program). Polynator (https://journals.iucr.org/j/issues/2023/06/00/jl5072/index.html).

References

Sheka, E. F., Razbirin, B. S. & Nelson, D. K. Continuous symmetry of C60 fullerene and its derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 3480–3490 (2011).

Nielsen, V. R. M., Le Guennic, B. & Sørensen, T. J. Evaluation of point group symmetry in lanthanide(III) complexes: a new implementation of a continuous symmetry operation measure with autonomous assignment of the principal axis. J. Phys. Chem. A 128, 5740–5751 (2024).