Abstract

Selective hydrogenation of CO2 into high-value C2+ oxygenates, such as acetic acid (AA), methyl acetate (MA), and ethanol, is highly attractive yet remains a significant challenge. This study demonstrates an innovative tandem catalysis system for converting CO2 to AA and MA, employing GaZrOx and hydrophobically modified MOR-8-C1@PC (PTFE+CNTs) catalysts. The upstream GaZrOx drives CO2 hydrogenation to produce an effluent gas with a controlled CO/(DME + CH3OH) ratio of approximately 4, facilitating the subsequent carbonylation reaction over the MOR-based catalyst. For the downstream catalyst, surface silanization of MOR zeolite combined with a hydrophobic promoter effectively prevents water (generated during CO₂ hydrogenation) from entering the zeolite channels and greatly enhances the carbonylation activity and catalyst stability. Results show that at a CO2 conversion of 27%, the selectivity towards AA and MA in the organics reaches up to 78%, with no catalyst deactivation observed over 50 hours. This strategy offers an efficient approach for converting CO2 into C2+ oxygenates, with promising implications for sustainable chemical production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The widespread utilization of fossil fuels has resulted in a persistent escalation of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, substantially contributing to the rise of global temperatures over the last century1,2. Extensive efforts have been devoted to developing CO2 capture and utilization (CCU) technologies. In this context, C1 chemistry, focusing on the conversion of CO2 into valuable chemicals, has attracted significant interest, as it enables the valorization of CO2 while simultaneously mitigating CO2 emissions3,4.

Although significant progress has been made in the conversion of CO2 to C1 products, the selective hydrogenation of CO2 to C2+ oxygenates remains a major challenge. The inherent inertness of CO2 and the high energy barrier for C–C coupling make the synthesis of C2+ oxygenates particularly difficult5. Most catalytic systems for the direct conversion of CO2 to C2+ oxygenates employ bifunctional catalysts, often containing noble metals such as Rh and Pd, which are known for their strong C–C coupling ability. However, the high cost and limited recyclability of these catalysts hinder their practical application6,7,8. Alternatively, Fischer–Tropsch catalysts (e.g., Co or Fe) and modified methanol synthesis catalysts (e.g., Cu) have been explored for the conversion of CO2 to C2+ oxygenates but mostly exhibited inferior selectivity toward the desired oxygenate products9,10,11,12.

Tandem catalysis, in which different reactions are carried out sequentially in a cascade, offers an alternative strategy to precisely control reaction pathways and intermediate species. Recently, tandem catalytic systems combining metal oxides and zeolites have been successfully applied for the conversion of CO2 into C2+ hydrocarbons, following a methanol-mediated reaction route13. In such a system, methanol is generated on oxides (e.g., In2O3, ZnZrOx, and ZnAlOx), followed by C-C coupling over zeolite catalysts (e.g., H-SAPO-34, H-SAPO-18, H-SSZ-13, H-ZSM-5) to produce light olefins14,15,16,17, gasoline18, aromatics19,20,21, and other hydrocarbons22,23. Unlike the Fischer–Tropsch mechanism, the methanol-mediated route helps break the limitations of Anderson–Schulz–Flory (ASF) distribution and enhances the product selectivity24,25. Although tandem catalysis has proven effective for converting CO2 to C2+ hydrocarbons, limited progress has been gained in the efficient and selective transformation of CO2 into C2+ oxygenates (e.g., acetic acid, methyl acetate, ethanol) via this approach.

CO2 can be readily converted to CO through the reverse water-gas shift reaction (RWGS, CO2 + H2 → CO + H2O). Additionally, CO2 can be hydrogenated to CH3OH and dimethyl ether (DME)26,27. Furthermore, methanol/DME can be effectively carbonylated to produce methyl acetate and acetic acid. Through the rational design of tandem catalytic systems that integrate CO2 hydrogenation and carbonylation, the selective conversion of CO2 into C2+ oxygenates, such as methyl acetate and acetic acid, can be envisioned. However, this concept has not been successfully implemented for the selective conversion of CO2 to C2+ oxygenates, likely due to the high oxygen content of CO2 and the associated significant water formation during its hydrogenation. For CH3OH/DME carbonylation, the presence of H2O is known to significantly inhibit zeolite-catalyzed carbonylation activity28. Mechanistic studies indicate that H2O disrupts DME adsorption and subsequent CO insertion processes, thereby suppressing carbonylation activity28,29. These detrimental effects of water are also evident in the triple tandem catalytic system converting syngas to ethanol29. Compared to syngas, CO2 hydrogenation produces substantially more water. The adverse impact of water on zeolite-catalyzed carbonylation becomes more pronounced and must be addressed when designing tandem catalytic systems for CO2 conversion.

Hydrophobic modification of catalysts can mitigate the impact of H2O on catalytic active sites while accelerating surface water diffusion, thereby enhancing reaction performance30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Xiao et al. reported a hydrophobic strategy involving physically mixed Fischer–Tropsch synthesis (FTS) catalysts with a hydrophobic promoter to accelerate the rapid diffusion of H2O from the catalyst surface and improve CO conversion35. Xu et al. designed a bifunctional catalyst comprising hydrophobic FeNa@Si-c and HZSM-5 zeolite, demonstrating unidirectional diffusion of H2O on the hydrophobic surface, thereby suppressing CO2 production in the water-gas shift (WGS) reaction34. The diffusion and migration behavior of H2O generated in situ on the catalyst surface has been thoroughly studied. However, in complex tandem systems, developing catalyst design strategies to mitigate the adverse effects of H2O remains worthy of further investigation.

Here, we propose a dual-bed tandem catalytic system combining GaZrOx and hydrophobically modified MOR-8-C1@PC for converting CO₂ into AA and MA. This system achieves a selectivity of 78% for AA and MA in the organic product distribution at a CO2 conversion rate of 27%, with no catalyst deactivation observed over 50 h. Mechanistic insights from catalytic tests and simulations reveal that the hydrophobic modification of the MOR-8-C1@PC prevents water diffusion in zeolite channels and promotes the quick escape of water into the bulk gas phase, thereby preserving active sites and maintaining catalytic stability.

Results

Rational design and hydrophobic engineering of a dual-bed tandem catalytic system

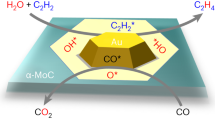

The tandem catalytic system comprises a bimetallic oxide, GaZrOx, and a hydrophobically modified MOR zeolite. The two catalysts are held in cascade reactors to control the reaction temperatures independently. During the reaction, a mixture of CO2 and H2 atmosphere is introduced into the upstream reactor, where GaZrOx catalyzes both CO2 hydrogenation to CH3OH reaction and the RWGS reaction, generating an intermediate atmosphere of CH3OH/DME and CO37. This intermediate atmosphere further passes through the downstream reactor, where CH3OH/DME carbonylation reaction occurs over MOR zeolite to yield AA and MA (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1). From an oxygen balance perspective, an inherent challenge in CO2 hydrogenation reaction is the coproduction of substantial volumes of H2O, due to the high oxygen content of CO2. The excess water poses a significant issue for the proposed tandem catalytic route, as water is known to negatively impact CH3OH/DME carbonylation.

a Schematic diagram of the tandem system. b Schematic diagram of the tandem catalysts in different modes. M1, MOR-8; M2, MOR-8-C1; M3, powered mixtures of MOR-8 and PC; M4, powered mixtures of MOR-8-C1 and PC. c Water contact angle of different catalysts. d XRD patterns of GaZrOx and MOR-8-C1/PC. e SEM image of the MOR-8-C1/PC. f TEM image and EDS elemental mapping of GaZrOx. g O(1s) XPS of GaZrOx Ga2O3 and ZrO2. h FT-IR spectra of MOR, MOR-8 and MOR-8-C1.

Hydrophobic treatment is thus designed and carried out on MOR zeolite to mitigate the potential adverse effects of water, i.e., Mode 1 to Mode 4 (Fig. 1b). The parent MOR zeolite catalyst is homemade, characterized by high crystallinity and a high percentage of 8-MR acidity. In Mode 1 (M1), the MOR zeolite was ion-exchanged with tetramethylammonium chloride to selectively cover the Brønsted acid sites (BASs) in 12-MR channels (named MOR-8) and directly assembled in the downstream reactor without any hydrophobic treatment. In Mode 2 (M2), surface silanization treatment was further carried out over this reference sample MOR-8 to cover its outer surface with non-polar -CH3, resulting in a MOR zeolite catalyst (named MOR-8-C1) with a hydrophobically modified surface (Supplementary Fig. 2). In Mode 3 (M3), an external hydrophobic promoter composed of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) particles modified with carbon nanotubes (named PC) was introduced and powder-mixed with the reference MOR-8 zeolite obtained in M138,39. Mode 4 (M4) coupled the surface silanization strategy in M2 and the external hydrophobic promoter PC in M3, where the silanized MOR-8-C1 catalyst is powder-mixed with PC in a mass ratio of 1:1, leading to the preparation of a composite catalyst (MOR-8-C1@PC). Under the four modes, the water contact angles of the catalysts were measured as 13°, 101°, 119°, and 129°, respectively (Fig. 1c), certifying the distinct hydrophobic properties of the samples treated in the four different modes.

Structural characterization of GaZrOx and modified MOR zeolite catalysts

The powder X-ray diffraction pattern of GaZrOx is displayed in Fig. 1d, which exhibits four reflection peaks (30.3°, 35.3°, 50.6°, 60.2°) that can be well indexed to the tetragonal zirconia phase (t-ZrO2, PDF#50–1089). The interplanar distance of the (011) lattice plane is measured to be 0.295 nm in the high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) image (Fig. 1f). With the incorporation of Ga, the corresponding t-ZrO2 characteristic diffractions moved to higher angles, which is caused by the smaller radius of Ga3+ ions (0.40 Å) than that of Zr4+ ions (0.82 Å) (Supplementary Fig. 3). The absence of the characteristic peaks of Ga2O3 in the XRD pattern and the uniform distribution of Ga, Zr, and O elements as revealed by TEM-EDS mapping prove that Ga element is uniformly dispersed in the ZrO2 matrix. The X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) of GaZrOx, ZrO2, and Ga2O3 are displayed in Fig. 1g and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5. The binding energy of Ga-2p in GaZrOx is 1117.9 eV, which is lower than the binding energy of individual Ga2O3 (1118.2)40. Meanwhile, the incorporation of Ga causes the Zr 3d signals (181.9, 184.3 eV) of ZrO2 to shift slightly towards the high binding energies. The interaction between Ga and Zr leads to changes in electronic properties, certifying that Ga is successfully added to the ZrO2 lattice to form a GaZrOx solid solution. In the XPS spectrum of O1s, the characteristic peaks at 530.0, 531.5, and 532.8 eV are attributed to lattice oxygen, oxygen vacancies, and surface-adsorbed oxygen, respectively37,41. With the addition of Ga, the content of oxygen vacancies (Ovacancy/Ovacancy+Olattice) in GaZrOx increases to 28.5%17. The formation of abundant oxygen vacancies can facilitate the chemisorption of CO2 on the catalyst surface and improve the conversion of CO2.

The physicochemical properties of the parent MOR zeolite are given in Supplementary Fig. 6, showing that it has a Si/Al ratio of 15.8 with high crystallinity. N2 sorption revealed a substantial reduction in pore volume and BET surface area of the zeolite following TMA+ ion exchange, attributed to the occupation of acidic sites within the 12-MR channels by TMA+ ions (Supplementary Fig. 7). In contrast, further silanization had a minimal impact on the micropore volume and surface area. Importantly, due to the small molecular size of DME (4.1 × 1.9 × 1.5 Å) and MA (5.3 × 1.9 × 3.1 Å), the modified zeolite exhibited no pore-blocking effects during the reaction. IGA tests using MA (the largest product molecule in this work) as the probe molecule were conducted to determine the diffusion coefficient before and after hydrophobic modification. The diffusion coefficient only decreased slightly from 2.18 × 10−2 to 1.12 × 10−2 cm2 s−1 after trimethoxymethylsilane modification, confirming a negligible impact on mass transport, excluding the possible influences of different diffusion properties of reactant/product molecules over catalytic performances (Supplementary Fig. 8). The FT-IR spectra of the samples are displayed in Fig. 1h. The band corresponding to the Brønsted hydroxyls shifted from 3606 cm−1 (parent MOR) to 3588 cm−1 (MOR-8) after TMA+ exchange. Deconvolution analysis reveals that the percentage of 8-MR BASs rises from 52% to 99% for MOR-8 (Supplementary Fig. 9), certifying that the acid sites in the 12-MR channels could be effectively covered by TMA+ exchange42. Meanwhile, new bands ranging from 2800 cm−1 to 3000 cm−1 appear with the anchoring of TMA cations, corresponding to the C-H vibrations in the methyl group (Fig. 1h)32. Besides TMA+ ion exchange, various alternative strategies, including selective dealumination, pyridine modification, and NH4+ modification, were also tried43,44,45. Among them, TMA-modified MOR-8 exhibited the lowest undesirable hydrocarbon selectivity and hence was opted as the selective acidity modification strategy for this study (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Regarding surface silanization treatment of MOR-8, a variety of alkylalkoxysilanes with varying alkyl groups were explored as the surface silanization agents. FTIR spectra (Supplementary Fig. 11) show the successful grafting of these alkylalkoxysilanes onto the MOR surface. The MOR-8 sample silanized with propyltrimethoxysilane (MOR-8-C3) exhibited the highest water contact angle (133o), suggesting superior hydrophobicity (Supplementary Fig. 12). The hydrophobicity of sample MOR-8-C16 is reduced, possibly due to the higher steric hindrance and consequent lower grafting degree46. The MOR-8 silanized with methyltrimethoxysilane (MOR-8-C1) also exhibits good hydrophobicity, with the water contact angle measured to be 121°. The thermal stability of the silanized MOR samples was investigated by thermogravimetric and temperature-dependent FTIR analysis (Supplementary Fig. 13). Although MOR-8-C3 demonstrates superior hydrophobicity, the C3 alkyl groups are prone to thermal decomposition (Supplementary Fig. 14). In contrast, MOR-8-C1 exhibits better thermal stability, with the grafted methyl groups being stably preserved at 300 °C. Considering its good hydrophobicity and thermal stability, MOR-8-C1 is thus selected for further study. As shown in Fig. 1h, the 3740 cm−1 band ascribed to the surface silica hydroxyls disappears, accompanied by a synchronous intensity increase of the C-H vibrational band in the range of 2800–3000 cm−1, suggesting that methyl groups were successfully grafted and passivated the surface hydroxyls. The successful grafting of the methyl groups is also corroborated by 13C MAS NMR spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 15), with a resonance peak near 0 ppm ascribed to methyl species. The 1H-29Si cross-polarization (CP) NMR spectrum reveals a significant decrease in the signal attributed to Q3 species (Si(OH)(OSi)3) after silanization, indicating the successful coverage of surface silanol groups. Additionally, new signals corresponding to silane-derived Si species emerge at −56 ppm and −66 ppm, further confirming the modification (Supplementary Fig. 16). The signal of Si(OH)Al at 4.2 ppm in the 1H MAS NMR spectrum of MOR-8-C1, as well as the hydroxyl vibration peak at 3588 cm−1 in the FTIR spectrum, remained unchanged, indicating that the silanization modification of the external surface does not affect the 8-MR BASs (Fig. 1h, Supplementary Fig. 17)47.

The introduction of external hydrophobic agents facilitates rapid diffusion of H2O from catalyst surface and enhances the catalytic performance35. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 18, PTFE exhibits good hydrophobicity with a contact angle of 108°. To further enhance its hydrophobic performance, CNTs were incorporated into PTFE, which increased the surface roughness and raised the contact angle from 108° to 132°(Supplementary Figs. 18, 19)38. In addition, the composite material PC displayed good thermal stability below 723 K(Supplementary Fig. 20). The composite MOR-8-C1/PC (1:1 mass ratio) exhibits the typical diffraction peaks of MOR structure in the XRD pattern (Fig. 1d), suggesting the crystal structure is not altered after surface silanization and powder-mixing with PC (Supplementary Fig. 6). SEM images show that MOR-8-C1 and PC were disorderly mixed in proximity, ensuring the smooth escape of H2O via the gaps between them (Fig. 1e). Sample MOR-8-C1 comprises platelike crystals with a size of ca. 300 nm (Supplementary Fig. 21). However, although MOR-8-C1/PC exhibited excellent hydrophobic properties (CA = 129°), it has an affinity for CH3OH (CA = 13.5°), indicating that the hydrophobic modification only alters its affinity towards water, without affecting the reactants (Supplementary Fig. 22).

Hydrophobicity-driven catalytic performance

The catalytic results of four different tandem catalysis modes comprising the sequential assembly of GaZrOx and MOR zeolite catalysts (M1–M4) are illustrated in Fig. 2. Without the assembly of MOR zeolite in the downstream reactor, GaZrOx was ready to catalyze the CO2 hydrogenation reaction with a CO2 conversion of 28%. The resultant outlet atmosphere comprised the unreacted CO2, CO, and a portion of CH3OH and DME, suggesting the co-occurrence of CO2 hydrogenation to CH3OH and RWGS reaction over GaZrOx. The ratio of CO versus CH3OH plus DME was calculated to be ca. 4 in the gas effluents (Supplementary Fig. 23). Although other bimetallic oxides such as InZrOx and ZnZrOx also demonstrate good CO2 conversion capabilities and suitable CO/(CH3OH + DME) ratios, notably superior stability is observed for GaZrOx (Supplementary Fig. 24, 25). This difference is particularly evident at the reaction temperature of 350 °C: ZnZrOx suffers from instability due to zinc volatilization and phase segregation, while InZrOx promotes excessive hydrocarbon formation, leading to carbon deposition and rapid deactivation. In contrast, GaZrOx achieves a more favorable balance between efficient CO2 activation and long-term stability, accounting for its superior overall catalytic performance22,48. GaZrOx is thus selected as the upstream catalyst of the tandem catalysis system. In situ DRIFTS analysis reveals that CO2 is activated at oxygen vacancies in GaZrOx, generating HCOO* and CH3O* intermediates that are hydrogenated to CH3OH/DME, with the concurrent formation of CO and water via RWGS reaction (Supplementary Figs. 26, 28). The upstream effluent subsequently undergoes carbonylation on the modified MOR zeolite in the downstream reactor, where CH3OH/DME undergoes activation at Brønsted acid sites to form methoxy species, which subsequently react with CO to generate acetyl intermediates and ultimately to form acetic acid (AA) and methyl acetate (MA) (Supplementary Figs. 27, 28).

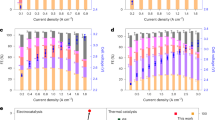

a Catalytic performance of different catalyst modes. Reaction conditions: H2/CO2/Ar = 71.25/23.75/5, T (upper bed) = 623 K, T (lower bed) = 558 K, P = 5.0 MPa, GHSV = 1200 mL gcat−1 h−1. Catalyst loading for upper bed: 0.5 g of GaZrOx. Catalyst loading for lower bed: M1, 0.5 g of MOR-8; M2, 0.5 g of MOR-8-C1; M3, 0.5 g of MOR-8 and 0.5 g of PC; M4, 0.5 g of MOR-8-C1 and 0.5 g of PC. b Photographs of the catalyst beds with different modes. HCs hydrocarbons, DME dimethyl ether, MA methyl acetate, AA acetic acid. The selectivity of organics was calculated on a molar carbon basis (CO free). The error bars represent the relative deviation within three independent experiments, which is within 3%.

The water generation rate over GaZrOx was stoichiometrically calculated and listed in Supplementary Table 1. Notable amounts of water were quickly generated under all the investigated conditions, which was expected to severely hinder the subsequent carbonylation of CH3OH/DME over MOR catalysts in the downstream reactor. Over the GaZrOx + MOR-8 tandem catalysis system, an AA + MA selectivity of ~40% was achieved, suggesting the feasibility of CO2 conversion to AA + MA via the designed tandem catalysis system (M1). However, it is also noted that the selectivity towards methanol and DME is over 50% in the organic products, suggesting that a high proportion of methanol/DME produced over GaZrOx in the upstream reactor remains unreacted in the downstream reactor. This result is not unexpected, as the presence of water is known to exert harmful effects on the carbonylation activity of MOR zeolite. When using silanized MOR-8-C1 instead of MOR-8 as the DME carbonylation catalyst, the selectivity toward AA + MA was significantly enhanced to 56% (M2), with the selectivity towards methanol and DME decreased to 36%, implying the improved carbonylation capability of the downstream catalysts. The introduction of external hydrophobic promoters was also beneficial for the DME carbonylation activity, with a selectivity towards AA + MA of 49% achieved (M3). When coupling surface silanization and external hydrophobic promoter modification in Mode 4 (M4), the AA + MA selectivity further rises to 78%, while the selectivity towards methanol and DME drops to 12% (M4). It is noted that the hydrocarbon selectivity is merely 7% over this tandem catalysis system. The above results reveal that different modes of hydrophobic treatment can unequivocally enhance DME carbonylation activity. The resultant hydrophobic surface is speculated to have shielded water from entering the MOR channels and hence preserves its carbonylation activity. The AA/MA ratio can be regarded as an indicator of water inhibition degree, as water is known to react with the acetyl intermediate and consequently generate AA during DME carbonylation49. The AA/MA ratio decreased from 2.3 for M1 to merely 1.4 (Supplementary Table 2), aligned with the increasing hydrophobicity of the four modes shown in Fig. 1c. Noted that, when replacing the GaZrOx by ZnZrOx, the AA/MA ratio rose to 9.0, showing that AA became the dominant oxygenate product (Supplementary Table 3). This difference is attributed to the distinct CH3OH/DME ratios in the upstream effluents of the two catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 24), as CH3OH are mainly carbonylated into AA, while DME favors MA production.

MD modeling of water diffusion in hydrophobic MOR

To further explore and elucidate the variations in water molecule diffusion behaviors under different hydrophobic modification conditions, a classical molecular dynamics (MD) modeling study was conducted. The effects of surface silanization are demonstrated through a comparative study of two models, i.e. the hydrophilic and hydrophobic MOR models as illustrated in Fig. 3a, b. Both models are constructed based on the periodic structure of the MOR framework, with a 40 Å thick vacuum nano slit created within, resulting in two distinct surfaces: the upper and bottom surfaces. In hydrophilic MOR, both the upper and bottom surfaces are fully covered with hydroxyl groups (-OH). Conversely, in hydrophobic MOR, these surfaces are entirely modified with -Si(CH3)m(OCH3)n groups, effectively mimicking a silanized environment.

a, b Diffusion models of water molecules within spaces enclosed by hydrophilic and hydrophobic MOR. c, d 2D-density contour of water at equilibrium within the hydrophilic and hydrophobic MOR models. e Scheme illustrates the escape process of water from MOR-8-C1@PC prepared via physical mixing. f, g Comparison of the escape process of water from Regions I to IV with and without the addition of PC. Region I: hydrophilic MOR; Region III: hydrophilic MOR or hydrophobic PC. h Variations in the number of water molecules in the four regions with MD simulation times.

Initially, 480 water molecules were placed within the nano slit and subjected to MD relaxation steps, during which diffusion along the z-direction was restricted to establish a stable initial water distribution configuration along the x- and y-directions. Subsequently, the final MD simulations were conducted using this relaxed configuration to investigate the axial movement of water molecules along the z-axis and the chance of water molecules entering the micropore channels of the MOR zeolite. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 29, water molecules diffuse more quickly into the micropore channels of MOR zeolite when it is not silanized. Specifically, during the first 100 ps of the simulation, ~200 water molecules are observed entering the micropore channels via the hydrophilic surfaces, after which they reach equilibrium. In contrast, for the model with silanized surfaces, this number decreases to only 30–40 molecules. The equilibrium water density contour, illustrated in Fig. 3c, d, highlights the distinct difference between the two models. In the hydrophilic model, water molecules are distributed within the micropores of the MOR zeolite as well as on the hydrophilic surface. whereas in the hydrophobic model, they are primarily confined in the nano slit between the upper and bottom surfaces. To quantitatively describe the anisotropic diffusion behaviors of water molecules, the mean square displacement (MSD) and diffusion coefficient (Ds) along different directions were calculated and shown in Supplementary Fig. 30.

After silanization, Ds in the x- and y-directions increased approximately twofold, whereas in the z-direction, Ds decreased dramatically from 4.8 × 10−8 m2/s to 1.6 × 10−9 m2/s. The above results confirmed that surface silanization treatment effectively mitigates water diffusion into the micropore channels of MOR zeolite while facilitating fast diffusion in the stacked voids between zeolite crystals.

To clarify the influence of external hydrophobic promoter (PC) on water diffusion behaviors, two additional models (Fig. 3f, g) are constructed and investigated in MD simulation. The models featured the co-existence of four regions (Region I, II, III, and IV) to simulate the physical mixture of MOR zeolite and the hydrophobic promoter. Region I represents the zeolite region, and Regions II and IV simulate the intercrystalline voids between zeolite crystals. Region III incorporates silanized quartz to represent the nonporous external hydrophobic promoter (Fig. 3g), whereas the control model shown in Fig. 3f utilizes only MOR zeolite without any additional promoters. A statistical analysis of the water distribution in the four regions at different time intervals was carried out and illustrated in Fig. 3h. The variation trend in Region I indicates that the number of water molecules decreases faster in the model containing the hydrophobic promoter compared to the control model. This suggests that the hydrophobic promoter facilitates quicker water escape from the zeolite region. This conclusion is further supported by the variation trend in Region IV. In the model containing the hydrophobic promoter, water begins to appear in Region IV as early as 150 ps (Fig. 3h and Supplementary Fig. 31d). In contrast, the number of water molecules remains negligible within the 0–900 ps timeframe for the control model (Supplementary Fig. 31a–c). To further highlight the superiority of the hydrophobic additives, we complemented a further modeling study by replacing the hydrophobic additives with hydrophobic MOR zeolite (Supplementary Fig. 32). Compared with hydrophobic MOR model, the mean square displacement (MSD) of hydrophobic additive model nearly doubled along the x- and y- direction (Supplementary Fig. 33a, b), accompanied by an early appearance of water molecules in Region IV (Supplementary Fig. 33c). These results justify our addition of hydrophobic additives, despite the fact that surface silanization already enhances hydrophobicity. The above analysis concludes that both surface silanization and the addition of an external hydrophobic promoter can alter water diffusion behaviors within the catalysts. Surface silanization effectively mitigates the axial diffusion of water into the zeolite channels, while the external hydrophobic promoter facilitates rapid water escape into the bulk gas phase (Fig. 3e). The close synergy of the two approaches leads to the most enhanced hydrophobic effects in M4 approach.

The reduced amount of water inside the zeolite catalyst, combined with the quick water escape, can significantly attenuate the negative impact of water on the DME carbonylation reaction in the downstream reactor. Consequently, this leads to improved overall catalytic performance for catalyst systems comprising hydrophobically treated zeolite catalysts, including M2 and M3, with even more pronounced effects observed in M4, which combines both surface silanization and the external hydrophobic promoter strategies.

Reaction condition optimization

In addition to the intrinsic properties of the catalysts, the reaction conditions are also crucial factors for catalytic performance of tandem catalytic system. Figure 4 illustrates the catalytic performance of the GaZrOx + MOR-8-C1@PC system (M4) with the temperature variation of the upstream and downstream reactors. As the reaction temperature of the upstream reactor increases from 573 K to 673 K, a volcano-like variation trend is observed for the AA + MA selectivity and more pronounced for the space-time yield (STY) of AA + MA. It is acknowledged that DME carbonylation activity is positively related to the partial pressure of CO in the reactant atmosphere. The influence of reaction temperature on CO2 hydrogenation over the single upstream GaZrOx catalyst was also carefully studied (Supplementary Fig. S23). With the rise of reaction temperature, the CO2 conversion shows a monotonous increase from 14% to 37%, with the CO selectivity dramatically rising from 48% to 90%, suggesting that RWGS reaction is favored at elevated temperatures. This trend is further corroborated by thermodynamical simulation, showing that higher temperatures favor the conversion of CO2 to CO, thereby increasing the CO/CH3OH ratio in the products (Supplementary Fig. 34)50. At 573 K, the CO/CH3OH ratio is calculated to be around 1 for the outlet product of and STY for this tandem system. The CO/CH3OH ratio rises with the temperature elevation, enhancing the overall MA + AA selectivity and STY of the tandem catalytic system. However, when the temperature increases to 673 K for the upstream reactor, a significant amount of hydrocarbons dominate the outlet product of the upstream reactor, leading to a reduced AA + MA selectivity. The excessively high CO content, together with the reduced AA + MA selectivity, collaboratively lead to a low AA + MA space-time yield for the tandem system at 673 K (Supplementary Fig. 35). This can well explain the volcano-like variation trend of AA + MA selectivity and STY with the temperature change in the upstream reactor.

a Product distribution and b Space-time yield of C2+ oxygenates under temperature changes in upper and lower beds. c Effect of total pressure and d space velocity on the reaction. e Long-term stability test of tandem system. Reaction conditions for a and b: H2/CO2/Ar = 71.25/23.75/5, P = 5.0 MPa, 1200 mL gcat−1 h−1; for (c), H2/CO2/Ar = 71.25/23.75/5, T (upper bed) = 623 K, T (lower bed) = 558 K, 1200 mL gcat−1 h−1; for (d), H2/CO2/Ar = 71.25/23.75/5, T (upper bed) = 623 K, T (lower bed) = 558 K, P = 5.0 MPa. e H2/CO2/Ar = 71.25/23.75/5, T (upper bed) = 623 K, T (lower bed) = 558 K, P = 5.0 MPa, 1200 mL gcat−1 h−1. Catalyst loading: upper bed, 0.5 g GaZrOx; lower bed, mixture containing 0.5 g of MOR-8-C1 and 0.5 g of PC. The selectivity of organics was calculated on a molar carbon basis (CO free). Error bars indicate the standard deviation (<5%) of MA + AA selectivity measured over a 3 h period.

The temperature-dependent variation trend for the downstream MOR-8-C1@PC catalyst (M4) is also followed. With the rise in downstream catalyst temperature, a monotonous increasing trend is observed for AA + MA selectivity and STY, corresponding to the superior carbonylation activities of the MOR-based catalysts at elevated temperatures (Fig. 4a). However, with the temperature increases to higher than 563 K, the selectivity towards hydrocarbons starts to be non-negligible, suggesting the occurrence of methanol to hydrocarbons (MTH) side reactions over MOR-8-C1@PC (Supplementary Fig. 36). The optimal reaction temperature for GaZrOx is determined to be 593-623 K to achieve an optimal intermediate atmosphere for the downstream carbonylation reaction. In contrast, a relatively lower reaction temperature of ca. 543–573 K is preferred for carbonylation catalysts to achieve a high DME carbonylation activity and to avoid undesirable hydrocarbon byproducts. The above results highlight the importance of temperature matching over this designed tandem catalytic system and justify the choice of this dual-reactor configuration as our tandem catalytic system.

The reaction pressure also affects the catalytic behavior of the tandem system (Fig. 4c). As the pressure increases, the CO2 conversion rises, whereas the selectivity of CO decreases, indicating an improved conversion of CO2 into organic products. The selectivity of AA + MA in organic products is maintained higher than 80%, even though a slight increase of hydrocarbon selectivity is observed. Notably, higher reaction pressure favors MA production over AA, resulting in elevated MA/AA ratios (Fig. 4c), primarily due to the compositional variations of the upstream effluent. To achieve an optimal space-time yield of AA + MA, a high reaction pressure of 5 MPa is preferred and selected for the tandem catalysis system. The space velocity is revealed to be a key factor influencing product distribution (Fig. 4d). At an excessively high space velocity, AA + MA selectivity decreases, due to the presence of a large amount of unreacted CH3OH + DME. Concurrently, the product distribution shifts towards acetic acid, resulting in a higher AA/MA ratio. Based on the above results, the optimal reaction condition is determined as follows: T (upstream reactor) = 623 K, T (downstream reactor) = 558 K, P = 5.0 MPa, GHSV = 1200 mL gcat−1 h−1. Under the optimized reaction conditions, a steady catalytic run of over 50 hours is realized, and the selectivity of AA + MA (excluding CO) is kept higher than 75% during the entire run (Fig. 4e).

CO₂ hydrogenation to ethanol via triple tandem catalysis

The above results demonstrate the successful assembly and feasibility of converting CO2 into C2+ oxygenates via the tandem catalysis concept. The primary C2+ oxygenates produced were MA and AA. To extend the product spectrum, CuZnAlOx, a common hydrogenation catalyst, was incorporated to explore the potential for ethanol production in a resulting triple tandem catalysis system. As presented in Supplementary Fig. 37, after the assembly of CuZnAlOx catalyst, the MA + AA selectivity in the organic products dropped sharply from ca. 80% to merely 5%. Meanwhile, ethanol emerged as an important product, achieving a selectivity of 50.5% at a CO2 conversion rate of 26%. These results highlight that by further adjusting the tandem catalysis system, the product spectrum can be flexibly shifted from AA + MA towards ethanol, an important and highly demanded oxygenate.

As the first demonstration of tandem catalytic strategy for converting CO2 into C2 oxygenates, this work lacks directly comparable systems in the literature. Results are therefore compared with studies targeting similar products (e.g., ethanol) that proceed via distinct reaction mechanisms. As shown in Supplementary Table 4, the tandem catalysis system integrating metal oxides with zeolites enables effective control of product distribution and enhances selectivity. These comparisons emphasize the potential of the tandem catalytic strategy for CO2 valorization.

Discussion

Selective CO2 hydrogenation to MA and AA was realized utilizing a tandem catalytic system combining GaZrOx and hydrophobically modified MOR-8-C1@PC. Under optimized conditions, the system achieved a CO2 conversion of 27%, with a combined selectivity of 78% toward MA and AA in the organic phase. The key innovations in this study involve the precise control of upstream effluent composition and the hydrophobic modification of the MOR-8-C1@PC catalyst. The former generates an effluent gas with a controlled CO/(DME + CH3OH) ratio of ~4, facilitating the MOR-catalyzed carbonylation reaction. The latter effectively prevents water generated during reaction from entering the zeolite channels and promotes its rapid escape into the bulk gas phase, thereby mitigating water-induced activity degradation and improving catalyst stability. Moreover, the system demonstrates remarkable flexibility, enabling the shift of product distribution toward ethanol via tailored catalyst combinations. These findings highlight the potential of the tandem catalysis approach to address critical challenges in CO2 valorization, including water management via hydrophobic modification and product selectivity control via the precise adjustment of the cascade reactions.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

Ga(NO3)3·9H2O (AR, 99.9%), Zr(NO3)4·5H2O (AR, 99.5%), Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (AR, 99%), In(NO3)2·xH2O (AR, 99%), tetramethylammonium chloride ((CH3)4NCl, AR), tetraethylammonium chloride ((C2H5)4NCl, AR), methyltrimethoxysilane (C4H12O3Si, 98%), chlorotrimethylsilane (C3H9ClSi, 98%), propyltrimethoxysilane (C6H16O3Si, 98%), trimethoxyphenylsilane ((CH3O)3SiC6H5, 98%), hexadecyltrimethoxysilane ((CH3O)3SiC16H33, 85%), (3-Aminopropyl) trimethoxysilane (C6H17NO3Si, 97%), PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene) aqueous dispersion (60 wt% in water), CNTs (carbon nanotube), SiO2 (AR) and PEEK (Polyetheretherketone) were purchased from Aladdin Chemical Reagent Company. NH3·H2O (25 wt%), pyridine (AR), and NH4NO3 (AR, 99%) were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd.

Oxide catalyst preparation for the upper bed

ZrO2, Ga2O3, ZnZrOx (Zn/Zr = 0.5) and GaZrOx (Ga/Zn = 0.5, 2) were prepared by sol-gel method22. Taking GaZrOx (Ga/Zn = 0.5) as an example, 4.18 g of Ga(NO3)3·9H₂O and 8.58 g of Zr(NO3)4·5H2O were dissolved in 100 mL deionized water at 353 K under stirring for 30 minutes. Subsequently, 18.0 g of glucose was added to the solution, followed by stirring for 6 h. The obtained product was dried at 393 K overnight and then calcined in air at 773 K for 4 h. In2O3 and InZrOx were prepared by coprecipitation method. 4.82 g In(NO3)2·xH2O (In2O3) or 4.82 g In(NO3)2·xH2O and 8.58 g Zr(NO3)4·5H2O (InZrOx) were dissolved in 100 mL deionized water at 353 K, then NH3·xH2O (5 wt% in H2O) was added dropwise until complete precipitation (pH = 9–10). After aging for 0.5 h, the suspension was washed three times with deionized water. The filtered sample was dried at 393 K overnight and calcined in air at 773 K for 4 h. CuZnAlOx (Cu/Zn = 2/1 in mole, Al2O3: 11 wt%) was purchased from Yanchang Zhongke (Dalian) Energy Technology Co., Ltd.

Catalyst preparation for the lower bed

A hydrothermal synthesis method was carried out for the preparation of Na-MOR zeolites. Sodium hydroxide, sodium aluminate, tetraethylammonium hydroxide solution (TEAOH, 35 wt%), and H2O were first mixed at room temperature and stirred until completely dissolved. Silica sol was then added dropwise under vigorous agitation. Subsequently, commercial MOR zeolite was added to the above mixture as seeds (4 wt% relative to SiO2). The molar compositions of the synthetic gel is 30SiO2: 0.8Al2O3: 2.4Na2O: 1.5(TEA)2O: 384H2O. After aging for 1 h under stirring, the final gel was transferred into an autoclave (100 mL) and heated under static conditions at 170 °C for 30 h. Afterward, the crystallized product was washed with distilled water, collected by centrifugation, and dried at 120 °C to get the as-synthesized Na-MOR sample.

HMOR was obtained by ion exchange method. Na-MOR was subjected to ion exchange using 1.0 M NH₄NO₃ aqueous solution at 353 K for 3 h, with the exchange process repeated twice. The resulting sample was washed 3 times with deionized water, dried at 393 K, and calcined in air at 823 K for 4 h to obtain HMOR.

The synthesis of MOR-8 was obtained by targeted removal of the BASs in 12-MR of HMOR and was prepared by three different methods, denoted as MOR-8 (Py+), MOR-8 (DAl), and MOR-8 (TMA+/TEA+). MOR-8 (Py+) was prepared by pre-adsorption of pyridine. HMOR (40–60 mesh) was heated at 673 K for 2 h in a fixed-bed reactor. After cooling to 573 K, pyridine vapor carried by N2 (100 mL/min) was passed through the HMOR. After treatment for 1 h, the sample was flushed with N2 (200 mL/min) for 1 h. MOR-8 (DAl) was obtained by selective dealumination and steam treatment using MOR-8 (Py+) as precursor. MOR-8 (Py+) was treated in a 0.1 mol/L NaNO3 aqueous solution to exchange the protons in 8-MR. The sample was calcined at 823 K to remove pyridine and then hydrothermally treated at 723 K for 4 h to remove the framework aluminum in 12-MR. After that, the sample repeated the same ion exchange step as HMOR to obtain MOR-8 (DAl). MOR-8 (TMA+/TEA+) was obtained by ion exchange method. HMOR was dissolved in 1.0 mol/L tetramethylammonium chloride/tetraethylammonium chloride solution, stirred at 353 K for 3 h and repeated 3 times. The sample was then washed 3 times with deionized water and dried overnight at 393 K. MOR-8-R samples were obtained by surface modification of MOR-836, where R refers to different types of silanization reagents. As a typical process for the synthesis of MOR-8-C1, 1 g of MOR-8 was dried in vacuum at 383 K overnight and then dispersed in 40 mL of toluene at room temperature. Subsequently, 1.36 g methyltrimethoxysilane was added. The mixture was stirred at room temperature at 500 rpm for 24 h, then washed 3 times with ethanol. After centrifuging, and drying at 393 K overnight, hydrophobic catalyst MOR-8-C1 was obtained. The synthesis methods for different samples were similar except for using different reagents as precursors. C1: methyltrimethoxysilane. C1Cl: chlorotrimethylsilane. C3: propyltrimethoxysilane. C6: trimethoxyphenylsilane. C16: hexadecyltrimethoxysilane. NC3: (3-Aminopropyl) trimethoxysilane. H-MOR-R samples were obtained by surface silanization treatment of HMOR, and the synthesis procedure was consistent with that of MOR-8-R.

PTFE-CNTs was obtained by evaporating CNTs and PTFE in ethanol solution. 0.6 g CNTs and 8.0 g PTFE aqueous dispersion were mixed in 50 mL of ethanol, and the mixture was stirred at 353 K until the ethanol was evaporated to dryness. After drying at 393 K overnight and calcined in air at 573 K for 4 h, powered PTFE-CNTs was obtained (denoted as PC). PTFE was obtained by the same method without adding CNTs in the process. SiO2-C1 was obtained by surface silanization treatment of fumed silica. The obtained sample was washed with ethanol for 3 times, dried at 393 K, and calcined in air at 573 K for 4 h. MOR-8-C1@PC was prepared by powered mixing 1 g of MOR-8-C1 and 1 g of PTFE-CNTs in an agate mortar grinding for 10 minutes, pressing the tablet under the pressure of 20 MPa and granulating to 40–60 mesh.

Catalyst performance evaluation

The reaction unit consists of two fixed-bed reactors, the temperature of each reactor can be controlled independently (Supplementary Fig. 1). The reactor was equipped with a quartz liner with an inner diameter of 10 mm. In a typical reaction setup, 0.5 g of GaZrOx was loaded into the upstream reactor, while 1 g of MOR-8-C1@PC was placed in the downstream reactor. When two beds were used, they were separated by a 3 mm layer of quartz wool. Prior to the reaction, the catalysts were pretreated under a 30 mL/min flow of 10%H2/90%N2 at 673 K (upstream) and 553 K (downstream) for 2 h, followed by cooling to the desired reaction temperature. The feed gas (23.75% CO2, 71.25% H2, 5.0% Ar) of 21 mL/min were then introduced into the reactor, and the system was pressurized to 5 MPa. Data were collected after a stabilization period of at least 2 h. Online product analysis was conducted using an Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph equipped with HP-PLOT/Q capillary column and TDX-1 packed column, connected to FID detector and TCD detector, respectively. The TCD detector was used to analyze CO2, CO, and Ar, while the FID detector quantified oxygenates and hydrocarbons. CO2 conversion and product selectivity were calculated on a molar carbon basis. Organic product selectivity was determined by excluding CO. The specific calculation formulas are as follows:

CO2 conversion was calculated on a carbon atom basis, that is,

The CO selectivity was calculated according to

The selectivity for each organic product X as determined on the basis of the number of C atoms,

The explanations of the symbols used in Eqs. (1)–(3) are as follows:

CO2 inlet: the mole of CO2 in the reactor inlet.

CO2 outlet: the mole of CO2 in the reactor outlet.

CO outlet: the mole of CO in the reactor outlet

Product X outlet: the mole of C atoms in organic product X.

\(\mathop{\sum }_{1}^{\mbox{n}}{n\cdot }{\mbox{C}}_{n}{\mbox{H}}_{m}{\mbox{O}}_{\mbox{x}}\): the total C moles in all organic species. n is the number of C atoms in the organic products (including hydrocarbons).

Catalyst characterization

The crystallinity of the catalyst samples was characterized by a PANalytical X’Pert PRO X‐ray powder diffraction (XRD) meter using a Cu Kα (λ = 0.154 nm) radiation source with a scanning angle (2θ) range of 5°–80°. The composition of samples was determined by Philips Magix-601 X-ray fluorescence (XRF). The topological images of samples were obtained by a Hitachi SU8020 scanning electron microscope (SEM). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images and corresponding EDS elemental mapping images were obtained on a JEM-2100F electron microscope with an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. Textural properties of the samples were estimated from nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms measured by Micromeritics ASAP 2020 instrument. All samples were outgassed at 553 K for 3 h before the measurement. A Bruker Tensor 27 spectrometer equipped with a mercury-cadmium-telluride (MCT) detector was used for the measurement of Fourier transform infrared spectra (FTIR). The samples were pressed self-supported wafers and placed into the in situ quartz cell. Subsequently, the wafers were dehydrated at 553 K in a vacuum for 30 min to remove the physiosorbed water. After cooling to room temperature, the spectra were collected by a MCT detector in the range of 4000–400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1. The coke deposition amount on the spent catalyst was analyzed by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, TA Q-600 analyzer) with a heating rate of 10 K/min from room temperature to 1200 K under air flow. The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analyses were conducted utilizing an ESCALAB 250Xi spectrometer with monochromatized Al Kα excitation radiation. Energy calibration was performed by referencing the C 1s photoelectron peak at 284.8 eV to compensate for surface charging effects. The uptakes of MA on the zeolites were carried out by an intelligent gravimetric analyzer (IGA) equipped with a mesh-type sample cell. The sample (20 mg) was added to the chamber and evacuated at 553 K for 4 h. Adsorption mass changes were recorded at 298 K under controlled pressures (0–10 mbar). 1H, 13C and 29Si MAS NMR were performed on a Bruker Avance NEO 500 spectrometer equipped with 11.7 T and 89 mm wide-bore magnet using a 3.2 mm H/F-X-Y triple resonances MAS probe with the corresponding Larmor frequency. Water-droplet contact angles were performed with Belsorp MaX II system. In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) was performed on a Bruker Tensor Ⅱ spectrometer equipped with a high-pressure reaction cell and an MCT detector. The reaction cell pressure was controlled by a back-pressure valve. Spectra were collected with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹.

Computational models and methods

To investigate the diffusion of water molecules into channel of MOR zeolite, two MD boxes with dimensions of around 73 × 82 × 150 Å3 are created, in which crystalline MOR structures are occupied. A nano slit with thickness of around 40 Å is generated in the center of MOR, and 480 water molecules are randomly inserted into as-generated nano slit. To study the effect of surface properties of MOR on the diffusion behavior of water molecules, the surface of MOR is chemically-bonded by hydrophilic -OH and hydrophobic -CH3 groups for comparison. Moreover, to further investigate the escape of water molecules from MOR, two another MD models are constructed. The two MD models are created with dimensions of around 41 × 40 × 292 Å3, in which four regions are divided; The bottom region is occupied by MOR with nano slit that contains water molecules source. The z-directional thickness of MOR is set to be around 30 Å. The nano slit surfaces of MOR are saturated by the hydrophilic -OH groups. The second region is generated as the vacuum space with z-directional thickness of around 27 Å. The third region is composed of MOR with length of 192 Å, in which a nano slit is created as the bottom region. The surface of nano slit-contained MOR is chemically modified by either hydrophilic -OH or hydrophobic -CH3 group to compare the water escape. The top region is set as vacuum region which is generated for the escape region of water molecules.

MD simulations are performed to relax confined water molecules with 1,000,000 timesteps at temperature of 523.15 K under NVT (constant number of particles, constant volume, and constant temperature) ensemble, in which the temperature is controlled by Nose-hoover thermostat. MOR-based systems are optimized to a local configuration with energy and force tolerances of 1.0 × 10−4 kcal/mol and 1.0 × 10−4 kcal/mol·Å, respectively. To describe the atomic interactions in the MOR-based systems, the consistent-valence forcefield (CVFF) potential is utilized51. During the MD relaxations, water molecules are not allowed to diffuse in the z-direction. Finally, MD simulations are performed at temperature of 523.15 K under NVT ensemble to investigate the diffusion of water molecules into the channels of MOR,and the escape of water molecules from the inner nano slit to long-length nano slit of MOR. All the MD calculations are implemented using the Large-scale Atomic-Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS) software package (software version: 19Nov2024-MSMPI)52.

MSD describes the average square displacement of the positions of all particles in the system over time from their initial positions. The MSD of water was defined as Eq. (4) in the following:

where N was the number of molecules, \({r}_{i}\left({t}_{0}\right)\) and \({r}_{i}\left({t}_{0}+\tau \right)\) denote the position vectors of particle I at the initial time \({t}_{0}\) and \({t}_{0}+\tau\), respectively. The diffusion coefficient Ds can be calculated by fitting the slope of the MSD curve according to Eq. (5).

where d was the dimension of materials. For a three-dimensional system, d = 3, while for a two-dimensional system, d = 2.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are provided in the main text, figures and Supplementary Information, or from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Feldman, D. R. et al. Observational determination of surface radiative forcing by CO2 from 2000 to 2010. Nature 519, 339 (2015).

Bushuyev, O. S. et al. What should we make with CO2 and how can we make it? Joule 2, 825–832 (2018).

Wang, W., Wang, S., Ma, X. & Gong, J. Recent advances in catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 3703–3727 (2011).

Liu, Y., Deng, D. & Bao, X. Catalysis for selected C1 chemistry. Chem 6, 2497–2514 (2020).

Zhou, W. et al. New horizon in C1 chemistry: breaking the selectivity limitation in transformation of syngas and hydrogenation of CO2 into hydrocarbon chemicals and fuels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 3193–3228 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Rationally designed water enriched nano reactor for stable CO2 hydrogenation with near 100% ethanol selectivity over diatomic palladium active sites. ACS Catal. 13, 7110–7121 (2023).

Lou, Y. et al. CeO2 supported Pd dimers boosting CO2 hydrogenation to ethanol. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 291, 120122 (2021).

Zhang, F. et al. Selective hydrogenation of CO2 to ethanol over sodium-modified rhodium nanoparticles embedded in zeolite silicalite-1. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 24429–24439 (2021).

Ding, L. et al. CO2 hydrogenation to ethanol over Cu@Na-Beta. Chem 6, 2673–2689 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Selective hydrogenation of CO2 to ethanol over cobalt catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 6104–6108 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Carbon-based electron buffer layer on ZnOx-Fe5C2-Fe3O4 boosts ethanol synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202311786 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Size-dependent and sensitivity of copper particle in ternary CuZnAl catalyst for syngas to ethanol. Appl. Catal. B:Environ. 336, 122949 (2023).

Cheng, K., Li, Y., Kang, J., Zhang, Q. & Wang, Y. Selectivity control by relay catalysis in CO and CO2 hydrogenation to multicarbon compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 57, 714–725 (2024).

Portillo, A., Ateka, A., Erena, J., Aguayo, A. T. & Bilbao, J. Conditions for the joint conversion of CO2 and syngas in the direct synthesis of light olefins using In2O3-ZrO2/SAPO-34 catalyst. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 61, 10365–10376 (2021).

Dang, S. et al. Role of zirconium in direct CO2 hydrogenation to lower olefins on oxide/zeolite bifunctional catalysts. J. Catal. 364, 382–393 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Tandem catalysis for hydrogenation of CO and CO2 to lower olefins with bifunctional catalysts composed of spinel oxide and SAPO-34. ACS Catal. 10, 8303–8314 (2020).

Zhang, P. et al. Boosting CO2 hydrogenation performance for light olefin synthesis over GaZrOx combined with SAPO-34. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 305, 121042 (2022).

Gao, P. et al. Direct conversion of CO2 into liquid fuels with high selectivity over a bifunctional catalyst. Nat. Chem. 9, 1019–1024 (2017).

Wang, T. et al. ZnZrOx integrated with chain-like nanocrystal HZSM-5 as efficient catalysts for aromatics synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation. Appl. Catal. B:Environ. 286, 119929 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. Highly selective conversion of carbon dioxide to aromatics over tandem catalysts. Joule 3, 570–583 (2019).

Ni, Y. et al. Selective conversion of CO2 and H2 into aromatics. Nat. Commun. 9, 3457 (2018).

Wang, S. et al. Highly selective hydrogenation of CO2 to propane over GaZrOx/H-SSZ-13 composite. Nat. Catal. 5, 1038–1050 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Selective conversion of CO2 to isobutane-enriched C4 alkanes over InZrOx-Beta composite catalyst. Nat. Commun. 14, 2627 (2023).

Xu, Y. et al. A hydrophobic FeMn@Si catalyst increases olefins from syngas by suppressing C1 by-products. Science 371, 610 (2021).

Zhai, P. et al. Development of direct conversion of syngas to unsaturated hydrocarbons based on Fischer-Tropsch route. Chem 7, 3027–3051 (2021).

Su, X., Yang, X., Zhao, B. & Huang, Y. Designing of highly selective and high-temperature endurable RWGS heterogeneous catalysts: recent advances and the future directions. J. Energy Chem. 26, 854–867 (2017).

Jiang, X., Nie, X., Guo, X., Song, C. & Chen, J. G. Recent advances in carbon dioxide hydrogenation to methanol via heterogeneous catalysis. Chem. Rev. 120, 7984–8034 (2020).

Boronat, M., Martinez-Sanchez, C., Law, D. & Corma, A. Enzyme-like specificity in zeolites: a unique site position in mordenite for selective carbonylation of methanol and dimethyl ether with CO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 16316–16323 (2008).

Han, S. et al. Efficient conversion of syngas into ethanol by tandem catalysis. ACS Catal. 13, 10651–10660 (2023).

Lu, Z. et al. Wettability engineering of solar methanol synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 26052–26060 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Surface hydrophobization of zeolite enables mass transfer matching in gas-liquid-solid three-phase hydrogenation under ambient pressure. Nat. Commun. 15, 2076–2076 (2024).

Zapata, P. A., Faria, J., Ruiz, M. P., Jentoft, R. E. & Resasco, D. E. Hydrophobic zeolites for biofuel upgrading reactions at the liquid-liquid interface in water/oil emulsions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8570–8578 (2012).

Wang, B., Zhu, Y., Qin, Q., Liu, H. & Zhu, J. Development on hydrophobic modification of aluminosilicate and titanosilicate zeolite molecular sieves. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 611, 117952 (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. Insights into the diffusion behaviors of water over hydrophilic/hydrophobic catalysts during syngas to high-quality gasoline. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202306786 (2023).

Fang, W. et al. Physical mixing of a catalyst and a hydrophobic polymer promotes CO hydrogenation through dehydration. Science 377, 406–410 (2022).

Jin, Z. et al. Hydrophobic zeolite modification for in situ peroxide formation in methane oxidation to methanol. Science 367, 193 (2020).

Feng, W.-H. et al. Insights into bimetallic oxide synergy during carbon dioxide hydrogenation to methanol and dimethyl ether over GaZrOx oxide catalysts. ACS Catal. 11, 4704–4711 (2021).

Wu, B. et al. Porous bulk superhydrophobic nanocomposites for extreme environments. Matter 6, 1992–2004 (2023).

Zhu, X. et al. A novel superhydrophobic bulk material. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 20146–20148 (2012).

Wang, J. et al. High-performance MaZrOx(Ma = Cd, Ga) solid-solution catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. ACS Catal. 9, 10253–10259 (2019).

Wang, M. et al. Spinel nanostructures for the hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol and hydrocarbon chemicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 14528–14538 (2024).

Chen, N. et al. Designed synthesis of MOR zeolites using gemini-type bis(methylpyrrolidinium) dications as structure directing agents and their DME carbonylation performance. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 8334–8343 (2022).

Cao, K. P. et al. Insights into the pyridine-modified MOR zeolite catalysts for DME carbonylation. ACS Catal. 10, 3372–3380 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. Identifying and controlling the acid site distributions in mordenite zeolite for dimethyl ether carbonylation reaction by means of selective ion-exchange. Catal. Sci. Technol. 10, 4663–4672 (2020).

Xue, H., Huang, X., Zhan, E., Ma, M. & Shen, W. Selective dealumination of mordenite for enhancing its stability in dimethyl ether carbonylation. Catal. Commun. 37, 75–79 (2013).

Han, X. et al. Tuning the hydrophobicity of ZSM-5 zeolites by surface silanization using alkyltrichlorosilane. Appl. Surf. Sci. 257, 9525–9531 (2011).

Hayashi, S. & Kojima, N. Acid properties of H-type mordenite studied by solid-state NMR. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 141, 49–55 (2011).

Wang, Y. et al. Visualizing element migration over bifunctional metal-zeolite catalysts and its impact on catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 17735–17743 (2021).

Boronat, M., Martinez, C. & Corma, A. Mechanistic differences between methanol and dimethyl ether carbonylation in side pockets and large channels of mordenite. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 2603–2612 (2011).

Santos, M. F., Bresciani, A. E., Ferreira, N. L., Bassani, G. S. & Alves, R. M. B. Carbon dioxide conversion via reverse water-gas shift reaction: reactor design. J. Environ. Manage. 345, 118822 (2023).

Maple, J. R., Dinur, U. & Hagler, A. T. Derivation of force fields for molecular mechanics and dynamics from ab initio energy surfaces. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 85, 5350–5354 (1988).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFE0207000), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22288101, 22272173), and DICP funding (DICP 1202420). The authors thanks to the funding from the Sino-French IRN (International Research Network).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H. performed experiments for catalysts preparation and catalytic reactions, and analyzed the experimental results. L.H. performed the 1H, 13C and 29Si MAS NMR characterization. D.F. performed molecular dynamics simulations. N.C. synthesized zeolite catalyst. S.H. wrote the paper. Z.L., D.F. and P.T. designed and guided the study, and revised the paper. All authors discussed and revised the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Zhong Li, and Chengli Rong for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, S., He, L., Chen, N. et al. CO2 hydrogenation to acetic acid and methyl acetate via tandem catalysis. Nat Commun 16, 11250 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66117-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66117-9